CATHOLIC WORKER

As we await the coming of the Messiah, who comes to us as a child at Christmas, we are conscious of how vulnerable the Lord was as a child and throughout his life.

The child’s father and mother were amazed at what was said about him; and Simeon blessed them and said to Mary his mother, “Behold, this child is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign of contradiction (and you yourself a sword will pierce) so that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed.”

This reminds us of how precarious life is also at Casa Juan Diego, a small microcosm of the Body of Christ. After the time of Jesus’ birth, people were on edge because of what was happening in the world around them. The people we have served for forty years are also frightened, not knowing what will happen tomorrow.

We continue our work, feeding the hungry, caring for the sick, and giving hospitality. We ask the prayers of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the saints, and all our readers. We do not receive government funds. We depend on you, our readers, to sustain us in this work

Sometimes people think that Casa Juan Diego is run by one person with the help of a few others. That has never been true. In addition to full-time people who live and work in the houses, countless friends and volunteers help every day.

The collaboration of many has been especially noticeable this summer because I (Louise) have been ill and often not able to be physically present.

In spite of my illness, the work of Casa Juan Diego continues, providing over 900 bags of groceries each week to families; our program of assistance to the disabled, the paralyzed people who were the victims of car accidents, those who cannot receive government funds; and our medical clinics for the poor undocumented each day.

We cannot name all the people who help, but here are a few: Allison, Anne, Annette, Bea, Daniel, Dawn, Jeannette, John, Jose, Juanita, Julia, Kevin, Lenore, Lupita, Mary, Manuel, Meg, Monica, Noemí, Stephen, Susan, Taína, Wilmer, the summer Notre Dame students, and the many other volunteers who help with the works of mercy at Casa Juan Diego each day.

Each gift given by those who help to keep Casa Juan Diego going, whether in time or a monetary donation, is a participation in God’s healing love for the poor.

We ask your prayers and support for the coming year.

Sincerely in Christ, Louise Zwick and all at Casa Juan Diego

Casa Juan Diego was founded in 1980, following the Catholic Worker model of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to serve immigrants and refugees and the poor. From one small house it has grown to ten houses. Casa Juan Diego publishes a newspaper, the Houston Catholic Worker, four times a year to share the values of the Catholic Worker movement and the stories of the immigrants and refugees uprooted by the realities of the global economy.

• Food Donation Central Office: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Women’s House of Hospitality: Hospitality and services for immigrant women and children Assistance to paralyzed or seriously ill immigrants living in the community.

Bottled water

Canned chicken

Fresh fruits and vegetables

Baby formula

Men’s jeans, waist sizes 27-32

For the plumbing and foundation:

Casa Juan Diego will be repairing the plumbing in and under the foundation of our main building. Contributions are welcome. We will be looking at repairing the foundation after fixing the plumbing. Pray

Casa Don Marcos Men’s House: For refugee men new to the country.

• Casa Don Bosco: For sick and wounded men.

Casa Maria Social Service Center and Medical Clinic: 6101 Edgemoor, Houston, TX 77081

Casa Juan Diego Medical Clinic

• Food Distribution Center: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Liturgy: In Spanish Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. 4811 Lillian at Shepherd

Funding: Casa Juan Diego is funded by voluntary contributions.

Houston Catholic Worker Vol. XLV, No. 4

EDITORS Louise Zwick & Susan Gallagher

TRANSLATORS Blanca Flores, Sofía Rubio

CATHOLIC WORKERS Dawn McCarty, Kevin McLeod Jeannette DeCorpo, Anne Ritter, Noemí Flores Joachim Zwick, Louise Zwick

TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Joachim Zwick

DESIGN Bea Garcia Castillo

CIRCULATION Stephen Lucas

AYUDANTES TEAM................................. Wilmer Salazar, Julián Juárez

Daniel De la Garza, Diego Contreras

PERMANENT SUPPORT GROUP................ Louise Zwick, Stephen Lucas

Dawn McCarty, Andy Durham, Betsy Escobar, Kent Keith

Julia Jackson, Monica Creixell, Monica Hatcher, Joachim Zwick

VOLUNTEER DOCTORS................................. Drs. John Butler, Yu Wah Wm. Lindsey, Laura Porterfield, Alfredo Viteri Darío Zuñiga, Roseanne Popp, CCVI, Enrique Batres Homero Anchondo, Deepa Iyengar, Mohammed Zare

Maya Mayekar, Joan Killen, Stella Fitzgibbons, Mona Aramos

VOLUNTEER DENTISTS.................Drs. Justin Seaman, Michael Morris

Peter Gambertoglio, Mercedes Berger, Jose Lopez

Maged Shokralla, Florence Zare

CASA MARIA.....................................Juliana Zapata and Manuel Soto

By Louise Zwick

When we heard that Pope Leo XIV had given his approval for John Henry Newman to be made a Doctor of the Church, I looked to Dorothy Day’s writings for her perspective on Newman and how this momentous decision relates to the Catholic Worker movement.

The references I sought were found in her diaries, published by Orbis Press as The Duty of Delight. There she recommends Louis Bouyer’s book, Newman: His Life and Spirituality (newer reprint available from Ignatius Press). Dorothy said the book was tremendous, after reading it in its entirety.

So with Dorothy’s endorsement, we began reading Bouyer’s Newman. Mark Zwick had told me about Newman’s leadership in the Oxford Movement, his study of the Fathers of the Church and Christian antiquity. He studied the Via Media, hoping to find the answer to his search for a contemporary manifestation of the Church of Christian antiquity within the Anglican Church. Periodically, over the last two centuries, groups within the Anglican Church hoped that the Via Media might be a solution for their search for a living model of the early Church. Ultimately, Newman’s pastoral and theological studies brought him to disappointment in the Via Media. His journey eventually led to his entry into the Catholic Church, even though he had been surrounded by prejudices, negative campaigns and persecutions against Catholics there in England.

During his spiritual and theological journey, Newman gathered many scholars to discuss with him the quest for the authentic revitalization of the Christian Church in all its fullness. He wrote extensively theologically during this time, still an Anglican. Some of these works were published and discussed extensively in England. In fact, Bouyer contends that in some of these writings Newman laid the groundwork for the coming forth of the theology of the mystical body of Christ.

Newman, in seeking this path, received criticism from many sides. After centuries of splits and divisions, scholars and pastors found it difficult to find the living, pristine Church they sought. Newman struggled theologically and ultimately came to the conclusion that the only Church where these expectations might be filled would be the Catholic Church. Even though his impression of the Catholic Church had been informed by common prejudices of the day, he decided to take the step to become Catholic. When he announced that he had decided to join the Catholic Church, many of his colleagues were horrified and in fact there was so much criticism that he wrote a book explaining this decision, Apologia Pro Vita Sua.

I learned so much more about Newman’s spiritual and theological journey by studying Bouyer’s book.

The decision to make Cardinal Newman a Doctor of the Church is surely a sign of our Holy Father’s commitment to unity in the Church, a unity the Church needs so much at this time. Conservatives and liberals and those in between love and admire John Henry Newman.

Like many saints and cardinals, Newman suffered many criticisms during his spiritual and theological journey.

As contemporary readers, we found fascinating the description that Bouyer gives of Newman’s treatise on Tradition in the Church.

There is much discussion in the Church today about so called “trads” and “non trads” and what is tradition. Is it in stone? Newman’s view of the matter:

“In this view of the matter, there are two forms, distinct yet inseparable, in which Tradition may be manifested. One of these forms he calls ‘episcopal Tradition’; the other

‘prophetical Tradition.’ The former consists of the official formularies of the hierarchy, such as the several creeds. It is an addition to, and an interpretation of, the Scriptures, but it is itself something committed to writing and therefore fixed, bounded, and stereotyped. Its purpose is to conserve and to safeguard (page 183).”

“But prophetical Tradition is both living and life-giving. Not confined to any particular period of time, it is, like life itself, both one and manifold. It suffuses the writings of the doctors, the formularies and ritual of the liturgies, the continuous teaching of the Church, and the soul of Christians as it expresses itself throughout the whole of their existence. Sometimes it is almost identical with episcopal Tradition; sometimes it overflows all limits and tends to fade and disappear in fable and legend. Therefore, if episcopal Tradition were not at hand to clarify and define it, prophetical Tradition would always be in danger of being overlaid by corruption; whereas it is the living truth that dwells for ever in Christian souls and in the continued pg. 7

By: Dawn McCarty, Ph.D., LMSW

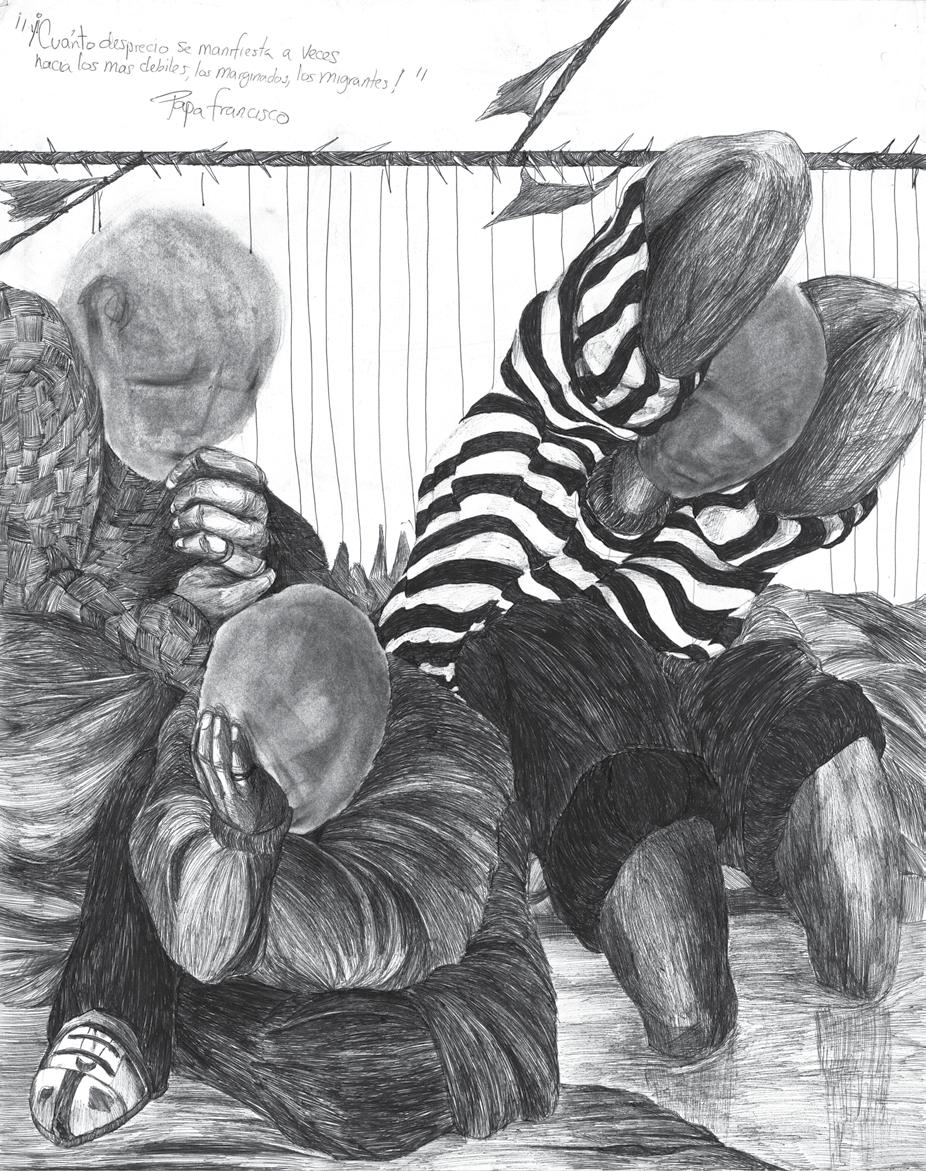

These days, I often find myself answering the same question: “How is Casa Juan Diego?” It’s a good question, one that deserves more than a simple answer. I could list the many difficult and frightening things happening right now: policies and practices that force individuals and entire communities into unnecessary suffering. The systematic closing of legal pathways, whether for asylum, work permits, or other forms of relief, makes it nearly impossible for newly arrived migrants to survive openly in our society, free from fear, or to participate in the legitimate economy.

Though I do not always say it out loud, things are bad for immigrants. As bad as I’ve seen them in my 14 years at Casa Juan Diego. There have always been struggles, but also victories, moments of progress and glimpses of stability for individuals and families. Now, more often, we find ourselves in survival mode. We do what we can to buffer the anxiety people feel under the constant threat of arrest and deportation. The air is thick with tension, heavy with unspoken grief.

This era of immigration is different. Today, it is no longer the act of migration itself that most often separates families, but the actions of immigration enforcement agencies. Increasingly, families migrate together, seeking to avoid long-term or even permanent separation. Deportation, and the constant fear of it, has become the primary threat to family survival, not only for newly arrived immigrant families, but also for those who have lived in our city and state for decades. Even those with a clean record for many years are now considered targets for arrest.

And yet, we continue. Our work has not stopped. After a brief dip in our food distribution, we are once again serving more than a thousand families each week. Our health clinics are busier than ever, with a growing team of volunteer doctors and medical specialists. Our houses remain open for hospitality. Pregnant women are receiving care. Children are nurtured and comforted. Families separated by deportation or displacement are being reunited. The isolated, sick, and dying are receiving passage home, and people are being accompanied to immigration courts and check-ins. Where harm has been done, we do all we can to make it right.

Amid all this hardship, I am reminded of a deeper truth at the heart of the Catholic Worker Movement. As immigrants are pushed further to the margins of society, into places where support and protection are scarce, as Catholic Workers, we go with them. That is our calling. To be in the harsh and dreadful places together. To refuse to let anyone face fear and vulnerability alone. This is the essence of Personalism, a core principle of the Catholic Worker Movement: to take personal initiative to feed the hungry, to clothe and shelter those in need, to walk alongside the frightened and persecuted. We practice this personalism, inspired by Dorothy Day, Servant of God and co-founder of the Movement, even when the effort seems futile. In solidarity with those on the margins, we may lack rationality. But hope? Hope is always alive. This is the heart and soul of Casa Juan Diego. Flawed as we may be, if you’re looking for us, you’ll know where to find us.

Around Casa, there have been some marked changes this past year. Although we are just as grateful for them, we see more “anonymous” donations from those too afraid to attach their names. We hear from volunteers who are legal permanent residents that they are anxious about putting their citizenship process at risk by showing up to serve. Most noticeable, outside our houses you’ll see something new: security.

At first, it was shocking to see our beautiful mosaic of the Virgin of Guadalupe enclosed in a protective cage. But I have come to see it differently. It has become a symbol of determination, of solidarity, of our commitment to protect this community. It sends a message to all who pass by that something sacred is found here. Something of great value and worth.

Now, every time I put my key in the new security gate, I say a prayer to our Virgin of Guadalupe. I pray for protection, for forgiveness for all those who have made this necessary, and for strength to endure whatever may come.

by William Droel

Our new Pope Leo XIV chose his papal name to pair his interest in our high-tech economy with Pope Leo XIII’s (1810–1903) interest in the Industrial Revolution. Today’s social questions, particularly “developments in the field of artificial intelligence pose new challenges for the defense of human dignity, justice and labor,” says the Chicago-born Leo XIV. In his 1891 encyclical, On the Condition of Labor, Leo XIII famously endorsed labor unions as one bulwark against the harshness of industrial capitalism. To do so, however, Leo XIII had to clarify his thinking and put aside an opinion about the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor.

Founded in 1869, the Knights of Labor was a large movement in the US. It was quite decentralized, with many chapters throughout the country. It also counted a few chapters in Canada and Great Britain. The Knights of Labor rarely achieved labor-relations contracts. More often its job actions resulted in an isolated pay raise or a safety improvement. It was better known for campaigns, including support for an eight-hour workday and prohibitions on child labor. The Knights of Labor attracted Catholics, who were likely the majority of its members. Its longtime president, Terence Powderly (1849–1924), was Catholic.

The Vatican was long suspicious of secret societies. The fear was over plots of violence, of anti-Catholic indoctrination, and of dark rituals. Catholic leaders in Europe favored fraternal groups and guilds over which there was a level of Catholic influence. In 1734 Catholicism formally prohibited membership to the Masons. In subsequent years, bishops penalized Catholics known to be Masons or members in other secret societies. For a time, the Knights of Labor used secrecy to help prevent employers from firing its members. Thus, Cardinal Elzéar Taschereau (1820–1898) of Quebec explicitly condemned the Knights of Labor in 1884. Five US bishops were prepared to ban the movement in this country. Leo XIII considered joining them.

Cardinal James Gibbons (1834–1921), a bishop since age 34, knew the situation of working families. “The Savior . . . never conferred a greater temporal boon on [people] than by ennobling and sanctifying manual labor, and by rescuing it from the stigma of degradation which had been branded upon it,” Gibbons said. Christ “is the reputed son of an artisan, and his early manhood is spent in a mechanic’s shop . . . Every honest labor is laudable, thanks to the example and teaching of Christ.” Gibbons was not about to allow a condemnation of the Knights of Labor to stand. He met with Powderly and negotiated changes to the organization, including dropping The

Noble Order from its name. He then fashioned an argument in favor of the union, saying, “It is the right of laboring classes to protect themselves, and the duty of the whole people to find a remedy against avarice, oppression, and corruption.”

In early 1887 Gibbons went to Rome and impressed upon Leo XIII the danger of losing working families to the faith if the pope were to condemn labor unions. Gibbons was persuasive, and the pope blessed labor unions. Leo XIII said that unions and government intervention can be countervailing forces against the “misery and wretchedness” that industrial capitalism tends to press “unjustly on the majority of the working class.” Gibbons’s effort on behalf of the Knights of Labor is considered the great achievement of his leadership in the US.

The picture is of Cardinal James Gibbons (1834–1921) Bill Droel is editor at National Center for the Laity (P. O. Box 291102, Chicago, IL 60629), which distributes a new edition of Pope Leo XIII’s On the Condition of Labor ; $7.

Church. Rather than any catalogue of dogmas and definitions, it is “what Saint Paul calls ‘the mind of the Spirit’, the thought and principle which breathed in the Church, her accustomed and unconscious mode of viewing things.”

As Catholic Workers, we were very interested to read of the prophetical tradition being one of the two essential forms of tradition. There are so many examples throughout the history of the Church of prophetical tradition. For example, there is St. Francis of Assisi who transformed the faith of the earth without firing a shot. We like to think that the Catholic Worker movement with Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin is an example of prophetic tradition. One can mention nonviolent peace movements and, on a small scale, so many projects that come from the Spirit all for the good of the human person and the common good. It appears we do not have to argue about who is traditional and who is not if we embrace the two forms that Cardinal Newman, doctor of the Church, presents.

We are printing here some actual writing of Cardinal Newman for you.

continued from pg 3

We published the following excerpt from a Newman sermon in the Houston Catholic Worker in November 2009

His condescension in coming down from heaven, in leaving His Father’s glory and taking flesh, is so far beyond power of words or thought, that one might consider at first sight that it mattered little whether He came as a prince or a beggar. And yet after all, it is much more wonderful that He came in low estate, for this reason; because it might have been thought beforehand, that, though He condescended to come on earth, yet He would not submit to be overlooked and despised: now the rich are not despised by the world, and the poor are. If He had come as a great prince or noble, the world without knowing a whit more that He was God, yet would at least have looked up to Him and honored Him, as being a prince; but when He came in a low estate, He took upon him one additional humiliation, contempt,— being condemned, scorned, rudely passed by, roughly profaned by His creatures.

What were the actual circumstances of His coming? His Mother is a poor woman; she comes to Bethlehem to be taxed, travelling, when her choice would have been to remain at home. She finds there is no room in the inn; she is obliged to betake herself to a stable; she brings forth her firstborn Son, and lays Him in a manger. That little babe, so born, so placed, is none other than the Creator of heaven and earth, the Eternal Son of God.

Well; He was born of a poor woman, laid in a manger, brought up to a lowly trade, that of a carpenter; and when He began to preach the Gospel He had not a place to lay His head: lastly, He was put to death, to an infamous and odious death, the death which criminals then suffered....

And it is remarkable that those who were about Him, seem to have treated Him as one of their equals. His brethren, that is, His near relations, His cousins, did not believe in him. And it is very observable, too, that when He began to preach and a multitude collected, we are told, “When His friends heard of it they went out to lay hold on Him; for they said, He is beside himself.” [Mark iii. 21.] They treated Him as we might be disposed, and rightly, to treat any ordinary person now, who began to preach in the streets. I say “rightly,” because such persons generally preach a new Gospel, and therefore must be wrong... They had lived so long with Him, and yet did not know Him; did not understand what He was. They saw nothing to mark a difference between Him and them. He was dressed as others, He ate and drank as others, He came in and went out, and spoke, and walked, and slept, as others. He was in all respects a man, except that He did not sin; and this great difference the many would not detect, because none of us understands those who are much better than himself: so that Christ, the sinless Son of God, might be living close to us, and we not discover it...

Thus He came into this world, not in the clouds of heaven, but born into it, born of a woman; He, the Son of Mary, and she (if it may be said), the mother of God... This is the All-gracious Mystery of the Incarnation, good to look into, good to adore; according to the saying in the text, “The Word was made flesh, — and dwelt among us.” ...

He came in lowliness and want; born amid the tumults of a mixed and busy multitude, cast aside into the outhouse of a crowded inn, laid to His first rest among the brute cattle. He grew up, as if the native of a despised city, and was bred to a humble craft. He bore to live in a world that slighted Him, for He lived in it, in order in due time to die for it.

He who loved us, even to die for us, is graciously appointed to assign the final measurement and price upon His own work. He who best knows by infirmity to take the part of the infirm, He who would fain reap the full fruit of His passion, He will separate the wheat from the chaff, so that not a grain shall fall to the ground. He our brother will decide about His brethren. In that His second coming, may He in His grace and loving pity remember us, who is our only hope, our only salvation!

(from Parochial and Plain Sermons: Sermons 16 and 13)

Reference Bouyer, Louis. Newman: His life and Spirituality. PJ Kenedy and Sons. 1958.

by Lucas Briola, Saint Vincentt College (Latrobe, PA)

“Peace be with you!” These were the first words that Pope Leo XIV spoke as he emerged from the balcony of St. Peter’s on May 8, 2025. He would use the word “peace” nine more times in his short address. Peace, it was clear, would take priority in his pontificate.

As Pope Leo made that priority clear, one phrase stuck out: a “peace that is unarmed and disarming” (“una pace disarmata e una pace disarmante”). The phrase has reappeared throughout the early months of Leo’s pontificate. Several days after his election, he implored journalists to “disarm words and we will help to disarm the world.” Since then, he has invoked this “unarmed and disarming peace” in messages to Pax Christi in the United States and a conference on interreligious dialogue in Bangladesh. Recently, the Vatican announced that Pope Leo chose “Peace be with you all: Towards an ‘unarmed and disarming’ peace” as the theme for the 2026 World Day of Peace. The phrase has emerged as a distinctly Leonine refrain and so offers an interpretive key for the kind of holiness to which he is challenging the world.

So too does it insert us into the history of the saints that Peter Maurin saw as the central story of history. May 8, the day of Pope Leo’s election, also happened to be the feast day of the Martyrs of Algeria. The feast remembers the nineteen Catholic missionaries killed during the Algerian Civil War in the 1990s.

His commitment to interreligious friendship embodied an unarmed and disarming love, even to the point of death.

Claverie’s words and life remind us of Dorothy Day’s own confession: “We are sowing the seed of love, and we are not living in the harvest time so that we can expect a crop. We must love to the point of folly, and we are indeed fools, as our Lord Himself was who died for such a one as this. We lay down our lives too when we have performed so painfully thankless an act, because this correspondent of ours is poor in this world’s goods.” An unarmed and disarming love— whether offered to a child, an immigrant, or our enemy—is vulnerable to the point of folly, even death. Christian de Chergé would

‘Disarm him.’ But then I asked myself, Do I have the right to ask God to disarm him if I don’t begin by asking, ‘Disarm me, disarm my brothers.’ That was my prayer each day.” Eighteen days later, around midnight on March 26, 1996, Islamist insurgents broke into the monastery and abducted de Chergé and six monks—all disarmed. A few months later, their kidnappers announced the monks’ deaths; today, their graves stand at Our Lady of Atlas.

describe such a commitment as a “martyrdom of love” or, even more, a “martyrdom of hope.”

One of those martyrs was the French Dominican, Pierre Claverie. Firmly committed to dialogue with Islam in the overwhelmingly Muslim Algeria, he became the Bishop of Oran in 1981. As Westerners came under increasingly virulent suspicion from various Islamic extremists the next decade, Claverie sensed the vulnerability and risk of such dialogue. In July 1994, he wrote, “What could be more foolish than going to meet death with no other protection than an unarmed and disarming (désarmé et désarmant) love that dies forgiving? Yet we are such people.” Almost exactly two years later, on August 1, 1996, a set bomb killed both he and his Muslim assistant. Mourners at his funeral called him “the bishop of the Muslims too.”

Prior of the Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Atlas in Tibhirine, Algeria, de Chergé and his community’s story has been movingly told in the 2010 French film Of Gods and Men. Among the film’s most memorable scenes—true to history—is de Chergé’s harrowing encounter with Sayah Attia and his men at the monastery on December 24, 1993: the eve of Christmas, feast of the Prince of Peace. While Attia was renowned as a ruthless killer, de Chergé pacified him by displaying his community’s commitment to the surrounding Muslim community and his own intimate knowledge of the Koran. A year later, in a Lenten retreat, he recalled the incident: “After the episode of Attia, I wanted to pray for him. What should I pray to God? ‘Kill him?’ No, but I could pray,

The unarmed and disarming peace of the Tibhirine monks found footing in their monastic vow of stability: their steady friendship with the area’s Muslim villagers amid the instability of a grisly civil war. While the monks had ample opportunity to leave, they stayed. While the monks were offered military protection, they declined. Tellingly, in a review of Of Gods and Men, the famous film critic Roger Ebert faulted the idealism of the monks and labeled their decision as folly. Yet, their reasons were Christological; in that same Lenten retreat, de Chergé professed that the call “to live the mystery of the Incarnation… is the deepest of all the reasons why we stay at Tibhirine…. The only way for us to give witness is to live where we do, and be what we are in the midst of banal, everyday realities.” We can think again of Dorothy Day, the Benedictine oblate, and her commitment to the corporal works of mercy in the Christological spirit of Matthew 25: the hungry, thirsty, and naked are Christ. That incarnate mercy takes the kenotic—unarmed and disarming—shape of Christ.

As Pope Leo reminded us in his first appearance, “Peace be with you!” are “the first words spoken by the risen Christ, the Good Shepherd who laid down his life for God’s flock.” This is a Peace that the world cannot give (Jn 14:27). This is a Peace that we receive and sign at each Eucharist: “grant us the peace and unity of your kingdom where you live for ever and ever.” After all, as Pope Leo’s episcopal motto—taken from that great Algerian saint, Augustine—reminds us, “In the one Christ, we are one.” Holy, unarmed, and disarming martyrs of Algeria, pray for us that it may be so.