CATHOLIC WORKER

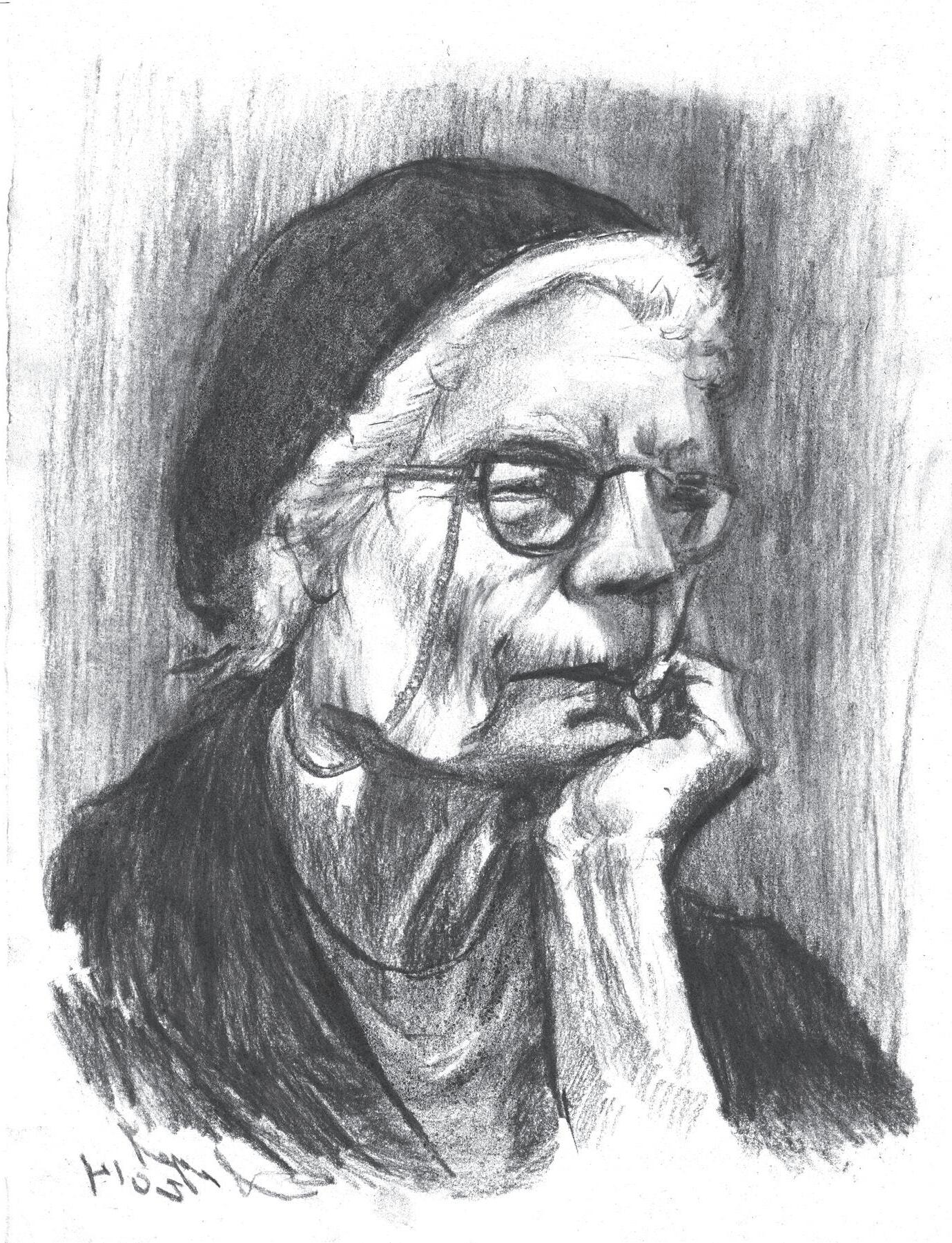

By Louise Zwick

Someone recently asked us if we were going to write about politicians, oligarchs, and technology czars, about their speeches and policies that hurt many. Hundreds of people, however, are already writing about that. We are trying to look more deeply at a spiritual response.

There is a crisis. It is not only in the United States. It is such a crisis that the Pontifical Academy for Life is meeting in Rome as we write, with the theme of this year’s annual gathering as “The End of the World? Crises, Responsibilities, Hopes.”

As we reflect on how to respond to recent events, upheavals, and tragedies, we wonder what the average person can do. We hope that through prayer and sacrifice, along with creative action, we may find a way forward in difficult times.

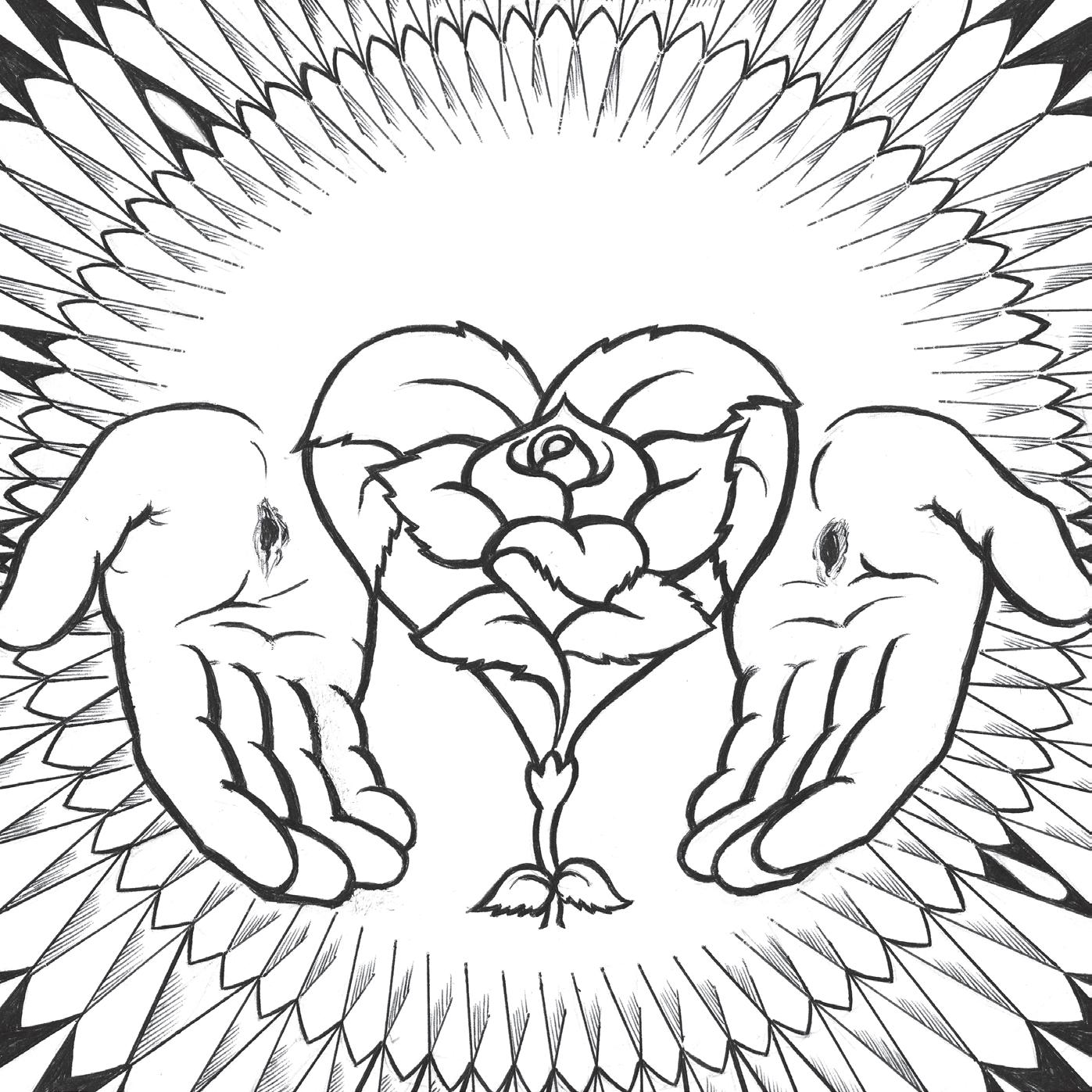

The traditional Catholic phrase, “Offer it up” is relevant. But what does this concept of sacrifice really mean? Can joining our suffering to the Cross have a transformative role in history? How can we be partners with God and put in our grain of sand for good in the cosmic struggle against evil and help with a reconstruction of the social order to save our world?

Reflecting on “offer it up,” Dorothy Day explained that what we can offer is not just our own suffering: “When we suffer, we are told we suffer with Christ. We are ‘completing the sufferings of Christ.’ We suffer his loneliness and fear in the garden when His friends slept. We are bowed down with Him under the weight of not only our own sins but the sins of each other, of the whole world. We are those who are sinned against and those who are sinning. We are identified with Him, one with Him. We are members of his Mystical Body.” (From Union Square to Rome)

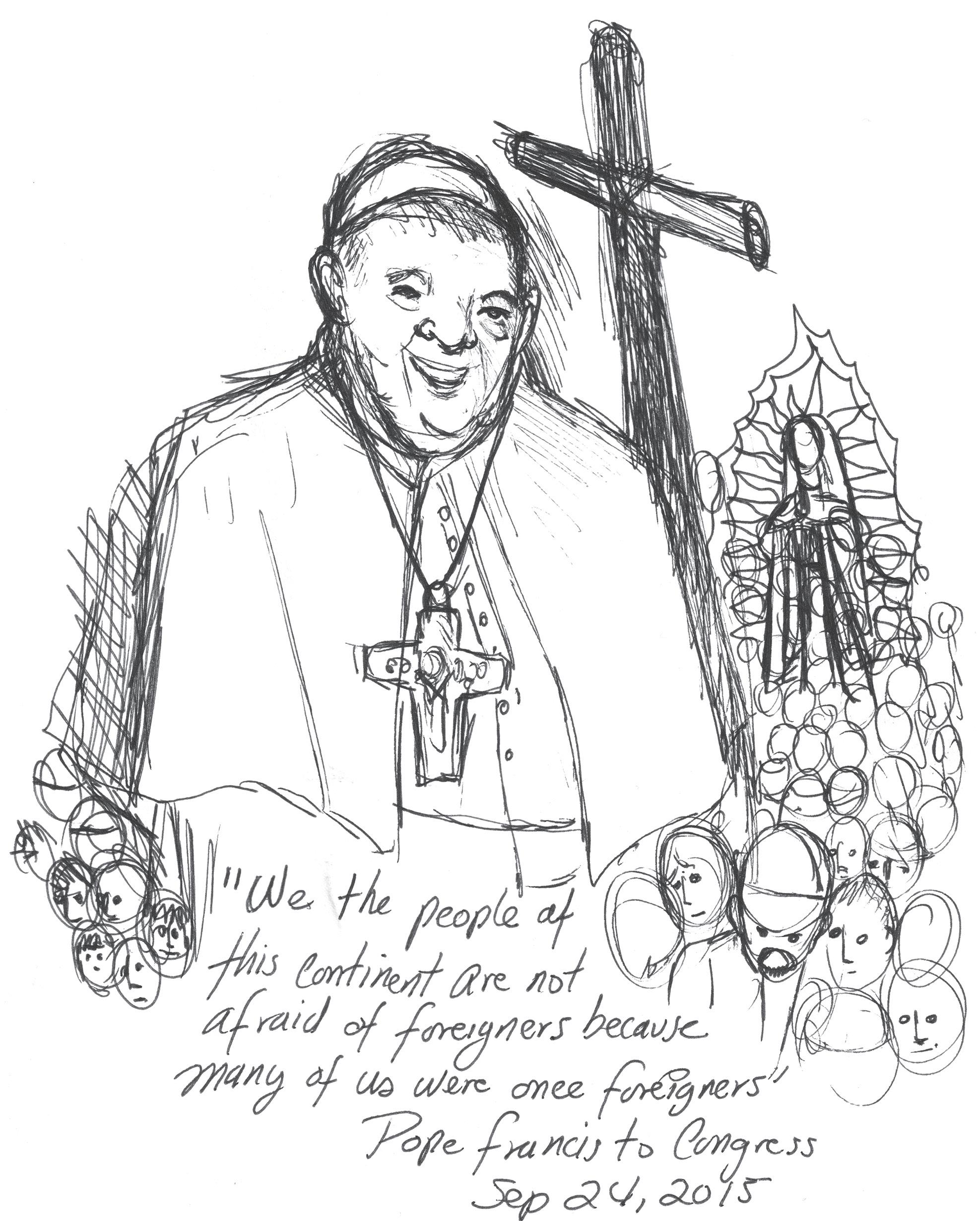

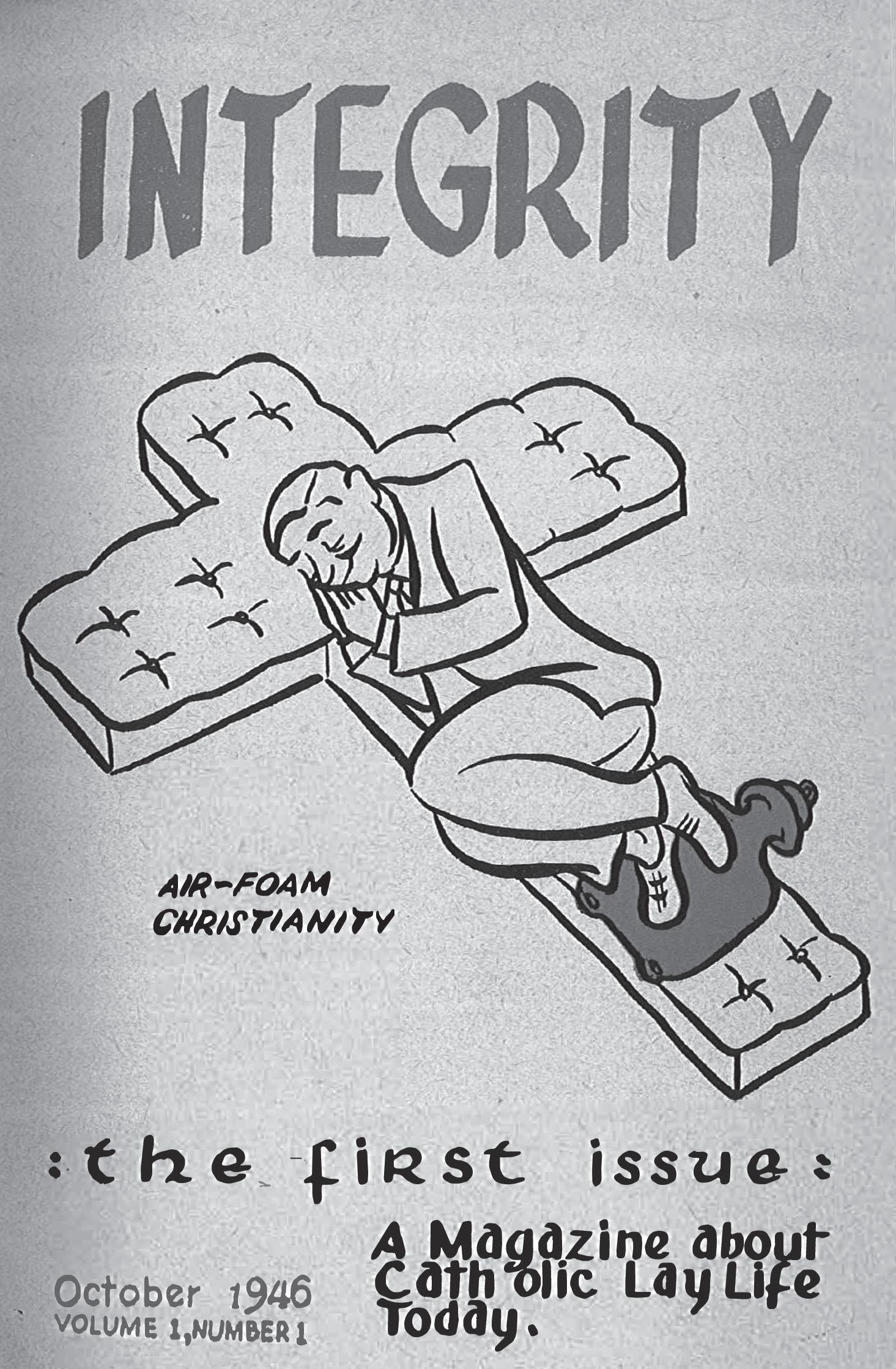

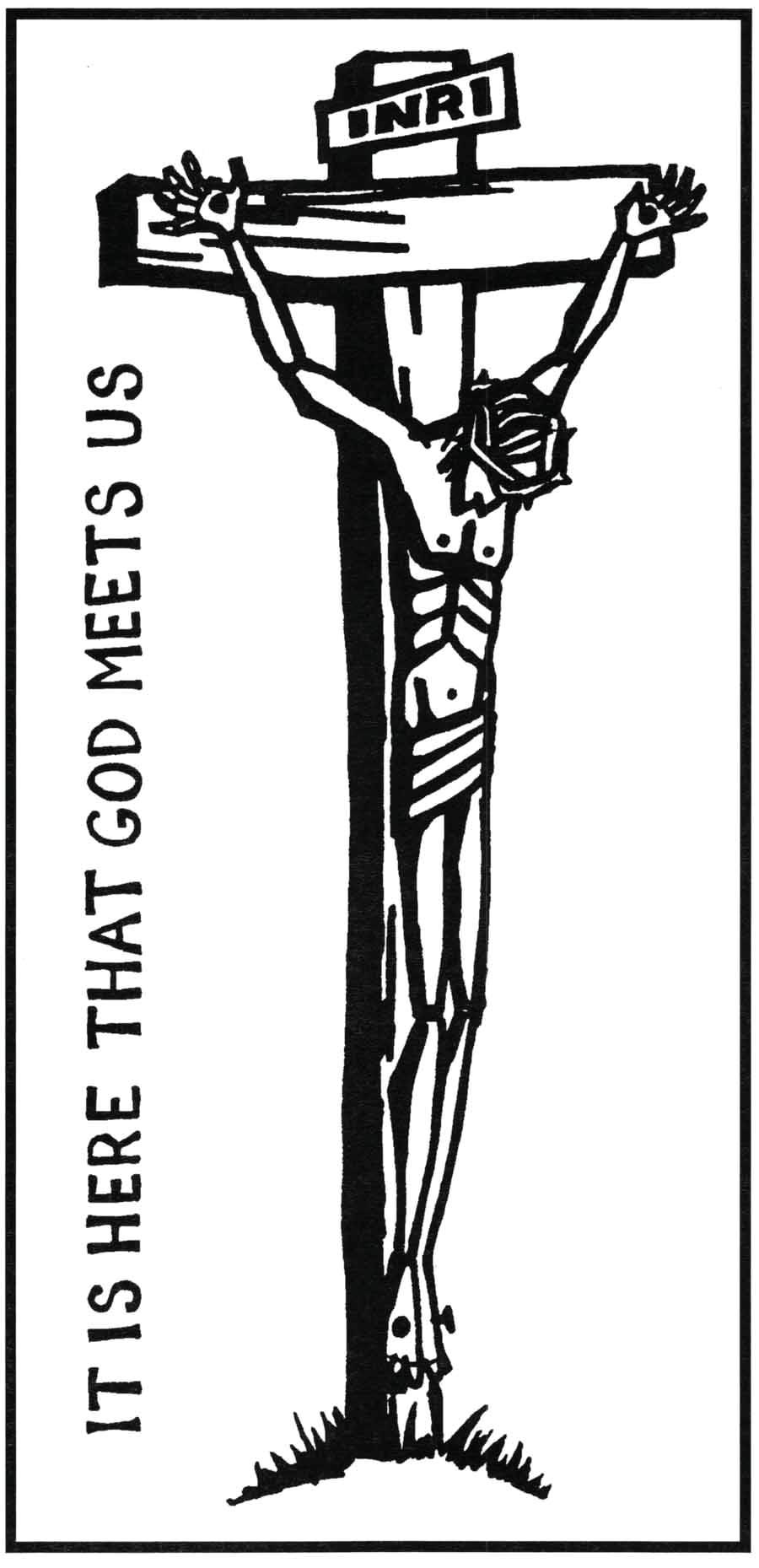

Fr. John J. Hugo, for many years Dorothy Day’s spiritual director, wrote of the Cross and its role in the life of the Christian, referencing Ed Willock’s drawing of an airfoam, comfortable cross:

“Radical Christianity [to the roots] is discovered only at the Cross, but who desires to be crucified? Like Peter and the other apostles—before the coming of the Holy Spirit!—we all tend to prefer a Christianity without the Cross, “airfoam Christianity,” as it was satirized by Ed Willock in an outrageous cartoon showing a contented Catholic— snuggled down on a cross spread with that seductive cushioning. Many attempt a life of vigorous and dedicated action, while failing to realize that such action is authentically Christian and efficacious only when grafted to the Tree of Life on Calvary.

(John J. Hugo, Your Ways Are Not My Ways, Vol. 1.) continued page 8

Good and evil are not, after all, two equal and opposing forces.

— Sergei Bulgakov

by Priscila Acuña Mena

Priscilla is a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego

From Mary’s fiat to the prophets of the Old Testament, God repeatedly calls His people to “be not afraid.” Yet, despite the blessings of a comfortable life, I am prone to fear. As a newlywed with plans to attend medical school and dreams of building a family, I have spent the last few years in ongoing, tortured deliberations about how I could possibly balance being both a mother and a doctor-in-training. These worries persisted even though I have remarkable support to pursue each of these beautiful, demanding callings. My anxieties peaked when my husband and I found out, shortly after moving to Casa Juan Diego, that I was pregnant—a joyful possibility we had been open to, but had not exactly planned for, either.

What I hadn’t anticipated was for my time as a pregnant Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego to transform my heart. This home, which strives to be radically hospitable to life, has shown me the courage and faith of many young mothers who trust God through life’s trials and joys. Rather than growing embittered or cynical, the hardship of some of our guests’ lives has pushed many of them to trust God more, not less. Courage is not the only antidote to fear–trust is, too. The powerful witness of our guests has moved me to be bolder, braver, and less afraid.

I remember the day I welcomed “Ari” and her husband to Casa Juan Diego. I noticed a small but solid baby bump under her sweater, one that seemed small for a third trimester pregnancy. I soon learned it was the result of inadequate nutrition on her journey. “I’m pregnant too,” I shared, feeling an immediate connection and an urge to try anything to help ease their burdens.

Over the coming weeks, other volunteers and I spent hours with Ari, navigating long hold times on the phone to establish her medical care here in Houston. We plied her with clothes and diapers for her baby boy, stocked her with Ensure shakes and Ziploc bags of slice cheddar cheese to help her gain weight. I heard more from Ari about the hardships she and her husband endured before arriving at Casa. With bus fare out of reach, they walked hours continued page 9

Casa Juan Diego was founded in 1980, following the Catholic Worker model of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to serve immigrants and refugees and the poor. From one small house it has grown to ten houses. Casa Juan Diego publishes a newspaper, the Houston Catholic Worker, four times a year to share the values of the Catholic Worker movement and the stories of the immigrants and refugees uprooted by the realities of the global economy.

• Food Donation Central Office: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Women’s House of Hospitality: Hospitality and services for immigrant women and children

• Assistance to paralyzed or seriously ill immigrants living in the community.

Casa Don Marcos Men’s House: For refugee men new to the country.

Casa Don Bosco: For sick and wounded men.

• Casa Maria Social Service Center and Medical Clinic: 6101 Edgemoor, Houston, TX 77081

Casa Juan Diego Medical Clinic

• Food Distribution Center: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Liturgy: In Spanish Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. 4811 Lillian at Shepherd

Funding:

Casa Juan Diego is funded by voluntary contributions.

EDITORS Louise Zwick & Susan Gallagher

TRANSLATORS Blanca Flores, Sofía Rubio, Lupita Guzman

CATHOLIC WORKERS Dawn McCarty, Marie Abernethy

Meg Thompson, Hunter Graves, Priscilla Acuña-Mena, Kevin Mcleod

Nathan O’Halloran, Joachim Zwick, Louise Zwick Felicity Klingele, Taína Lara

TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Joachim Zwick

DESIGN

Bea Garcia Castillo

CIRCULATION Stephen Lucas

AYUDANTES TEAM........................... Wilmer Salazar, Ramiro Rescalvo

Julian Juárez, Daniel De la Garza, Edilson Herrera, Carlos Castillo

Jorge Coello, Juan Morales, Xelil Badepeima, Edwin Pabon, Miguel Rojas

PERMANENT SUPPORT GROUP................ Louise Zwick, Stephen Lucas

Dawn McCarty, Andy Durham, Betsy Escobar, Kent Keith

Julia Gallagher, Monica Creixell, Pam Janks Monica Hatcher, Joachim Zwick

VOLUNTEER DOCTORS................................. Drs. John Butler, Yu Wah

Wm. Lindsey, Laura Porterfield, Alfredo Viteri

Darío Zuñiga, Roseanne Popp, CCVI, Enrique Batres

Homero Anchondo, Deepa Iyengar, Mohammed Zare

Maya Mayekar, Joan Killen, Stella Fitzgibbons

VOLUNTEER DENTISTS.................Drs. Justin Seaman, Michael Morris

Peter Gambertoglio, Mercedes Berger, Jose Lopez

Maged Shokralla, Florence Zare

CASA MARIA.....................................Juliana Zapata and Manuel Soto

As we write, Pope Francis is very ill in the hospital with double pneumonia. The world is praying for him.

We recall that on March 13, 2013, when the white smoke emerged to show that the first Latin American pope had been elected, the Catholic Workers at Casa Juan Diego were gathered for our luncheon meeting for clarification of thought, watching the television for news on the papal election. We all heard him speak as he emerged from the conclave and asked everyone to pray for him.

Mark Zwick wrote at the time: “The very first thing the new Pope did was to choose the name Francis. This is brand new. No Pope has ever been named Francis before. He said it is for Francis of Assisi. If he had not done anything else, just claiming the name of Francis would have had a tremendous impact.”

With the name Francis comes all of the meaning of a saint who lived the spirit of poverty and the reality of voluntary poverty. He was a man for the poor, but also a man of peace, against war, a man who loved creation and all its creatures.”

In his press conference a few days after his election, to the thousands of reporters gathered in Rome, Pope Francis explained how he chose the name:

“During the election, I was seated next to the Archbishop Emeritus of São Paolo and Prefect Emeritus of the Congregation for the Clergy, Cardinal Claudio Hummes [OFM]: a good friend, a good friend! When things were looking dangerous, he encouraged me. And when the votes reached two thirds, there was the usual applause, because the Pope had been elected. And he gave me a hug and a kiss, and said: “Don’t forget the poor!” And those words came to me: the poor, the poor. Then, right away, thinking of the poor, I thought of Francis of Assisi. Then I thought of all the wars, as the votes were still being counted, till the end. Francis is also the man of peace. That is how the name came into my heart: Francis of Assisi. For me, he is the man of poverty, the man of peace, the man who loves and protects creation; these days we do not have a very good relationship with creation, do we? He is the man who gives us this spirit of peace, the poor man … How I would like a Church which is poor and for the poor!”

Pope Francis did so much more than choose his name. In his years as pope he has lived simply, he has been close to the poor, to migrants and refugees. He has insisted that the Gospel is not only for middle-class and wealthier Catholics but includes a preferential option for the poor. He put forth his best efforts toward peacemaking and followed St. Francis of Assisi in his concern for protecting creation. We recommend reading again his great Catholic writings listed here. All are available at vatican.va.

• Apostolic Exhortations

• Evangelii Gaudium: The Joy of the Gospel

• Gaudium et Exsultate: On the Call to Holiness in Today’s World

• Encyclicals

• Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home

• Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship

• Dliexit Nos ; On the Human and Divine Love of the Heart of Jesus Christ

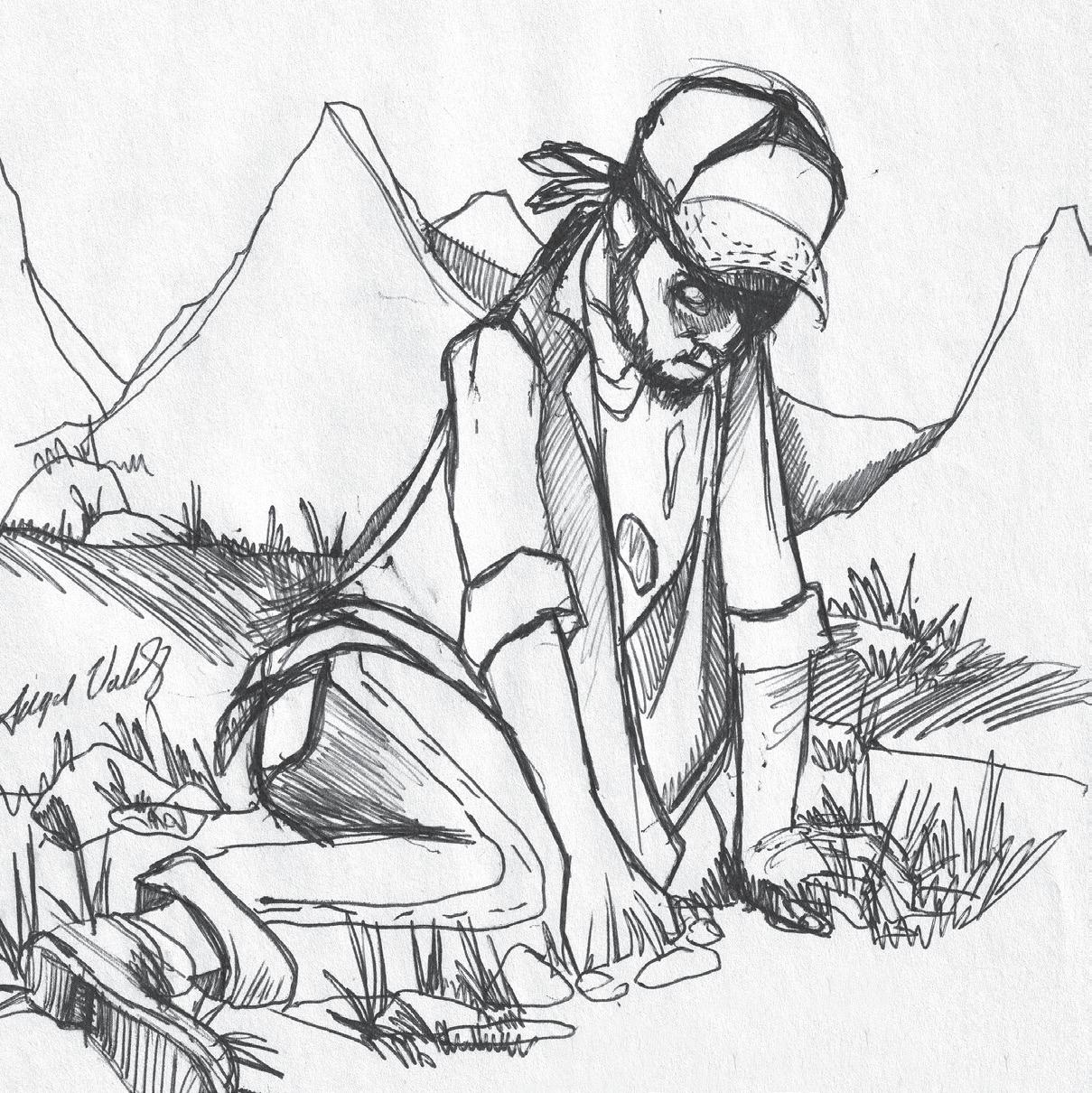

Artist: Angel Valdez

When Archbishop Vésquez was Auxiliary Bishop of Galveston-Houston, he celebrated Mass at Casa Juan Diego for the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe. He is pictured here at that Mass with Fr. Italo Dell’Oro, who is now our Auxiliary Bishop.

All of us at Casa Juan Diego add our voices to the many who welcome our new Archbishop Joe Vásquez to the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston. Archbishop Vásquez was Auxiliary Bishop here from 2001 to 2010 when he became Bishop of Austin. He served as Bishop in Austin from 2010 to 2025. We rejoice with his return to Houston.

By Margaret (Meg) Thompson

Meg is a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego.

For the past couple of years, if you had asked me seriously about my relationship with God, I would tell you God and I weren’t really getting along. I had a particularly difficult time feeling connected to the Mass. It felt like an obligation instead of an opportunity to spend time with God. I often found myself distracted, thinking of what I was going to do afterward, or even counting down the minutes until it was over. However, attending Mass at Casa Juan Diego has allowed me to reconnect with this part of my faith.

The crux of my faith is the belief that God is in the poor and we as Catholics are meant to be close to and know the poor. At Casa Juan Diego, I have the privilege of living this out every day and have especially grown to love attending weekly Mass here. Every Wednesday evening, those of us who live in the women’s house gather around 6:45 in the comedor, and then make the quick walk over to the men’s house for Mass. I am sure the train of women and children make quite the spectacle for those driving down Durham Drive–with the loud laughter, children crying, and lively conversation.

During Mass, I am almost always brought to tears during Communion. The words “They knew him in the breaking of bread,” from Luke 24, echoed in Dorothy Day’s diary The Long Loneliness, often cross my mind. Day writes, “We cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other. We know Him in the breaking of bread, and we are not alone any more. Heaven is a banquet and life is a banquet, too, even with a crust, when there is companionship.” She derives these words from the story of Emmaus in the Bible, within which two men walk with Jesus but do not recognize him until he invites them for dinner and breaks bread with them.

The story of Emmaus and Day’s words certainly feel relevant to my life at Casa Juan Diego. I am blessed to have the opportunity to break bread with so many different people every week during Communion. Many of our guests are not Catholic but still go up to receive a blessing.

I witness children clinging to their mom as they approach the priest for the blessing and get to listen to Louise joyfully leading our Communion hymn while the rest of us stumble through it. This weekly practice has made me feel grounded in my faith again. Although I attended college at a Catholic university, it was difficult to find spaces to be in such consistent proximity to the poor. I participated in programs that allowed me to serve and live in solidarity for a period of time, but nothing that led me to form long-lasting relationships.

The other day, one of the women told me, “Margarita, tengo miedo” (I’m afraid). She showed me an article discussing local ICE raids. I instinctively went to reassure her, explaining that she should be okay because she has papers. I forgot, however, that her adult son is also living in Houston who does not have documents. Perhaps, many people would just look at this woman and her son and think, “Well, he should’ve just done it the right way!” Of course, it is not that simple and they also do not have the opportunity to see what I see.

I’ve had the privilege to taste her food and the love that is cooked into it. I get to hear her daily response to how are you“Bien, gracias a dios” (Good, thanks to God). I’ve witnessed the friendship that has formed between her and another long-term guest. I’ve joked with her daughter-in-law, often in English, as she’s been working very hard to learn the language.

I am also reminded of another guest with whom I’ve had the privilege to live with over the past six months. I have spent hours working on her case and its many complications. It has shown me just a glimpse of how difficult being an immigrant is, even after arriving in the United States. This guest is one of the first individuals I had a real conversation with upon my arrival to Casa. On my first day here, I sat with another volunteer as we began to help fill out her asylum application. She sat and listened patiently as I stumbled through my Spanish.

Since this day, she has become someone I consider my friend. She has continued to be patient with my Spanish and is quick to understand me when I don’t know a word. She makes me cry laughing (my favorite trait in a person) and teaches me new things all the time, to the point I told her the other day, “Usted es como mi mamá” (You are like my Mom).

It is like Dorothy says, that we cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other. I wish everyone could have the opportunity I have had to be in such close proximity to the immigrant community. Although I have been Catholic my whole life, I have never felt quite so close to God. This is not because I believe I am doing something particularly impactful, but it is because I meet God in the person in front of me every day.

Artist: Angel Valdez

By Dawn McCarty, Ph.D., LMSW

I live in two worlds. For the past 16 years, I have been serving immigrant communities at the Houston Catholic Worker, offering the Works of Mercy, both Corporal1 and Spiritual2 to all that cross our door. My day job is directing the social work program at a local university.

This is a juggling act—the changing of clothes from one setting to the next, trying to remember did I take a shower; did I eat, which language am I speaking? At my University I am important: senior in rank and status with a fancy title and beautiful office, addressed as “Doctor.” At Casa Juan Diego, I am the opposite: small, no office, not addressed by any title (or even my correct name most of the time), not special, not important, not even paid. This is by design. The Catholic Worker movement is based on a totally different worldview, one that rejects the climb-the-ladder-of-success ethos of both modern universities and social work organizations. Whether in government, nongovernmental organizations, or the private sector, most organizations operate bureaucratically – top down, with workers and bosses, workers filling slots on an organization chart and judged by how much they contribute to goals set by the bosses. The work is seen as more important than the workers. All too often, workers are just cogs in the machine and, if the worker can be replaced by robots, computers and/or computer algorithms, so much the better.3

This model as applied to organizations tasked with meeting the needs of migrants was arguably not working all that well in the past, but the institutions themselves are now losing their funding support. As programs lose resources and capacity seemingly by the hour (Catholic Charities lost a third of its workforce in Houston last month), the distinction between my two worlds, the decentralized and socially deconstructed Catholic Worker model and

the professionalized welfare world has become only too obvious. The “shock and awe” attacks on the budgets and staffing of professional agencies, attacks on their very mission, have stunned their leadership. What worked in the past for them was clearly not going to work in the future.

The Catholic Worker movement started during the Great Depression, another time when the old ways were no longer working. By 1933 the economic system had collapsed and President Hoover’s attempts to deal with the problem was making it worse. Millions of people in dire need of even the basics of aHospitality.

Nobody thought, then or now, that a Catholic Worker house, or a thousand Catholic Worker houses for that matter, were going to end the Depression. The scale of suffering was just too great. Dorothy believed, however, that we were called to do all we could, in line with what we believed; results were up to God. The beliefs, the core principles behind her actions, were what counted most.

I believe that once again we are in revolutionary times and that our Catholic Worker principles have much to teach our formalized social welfare system about how to understand and deal with the new world we are facing.

For instance, personalism, which emphasizes our individual responsibility for helping others instead of relying so much on the government and other large institutions. Catholic Workers put personalism in action by living a simple life in community, actively working against violence in all forms, performing the works of mercy in whatever context is present. Instead of operating on government funding or grants we rely on the donations of our supporters. All the money that is given to us is used in direct service to others. In our space of freedom, where we take no money from any government or institution, we can build the sort of society we want to see. We can model for others how it would look, and the good that it

can do. This model is also healing for everyone, protects the staff and volunteers from burnout, and has the best chance to promote the conditions of empowerment for those at the bottom of our stratified social systems. At Casa Juan Diego, many different people come to collaborate, and the Catholic nature of our movement is easily expressed by all in the ways that we give priority to the dignity and worth of the human person. While we do many tangible things at Casa Juan Diego to support asylum seekers, refugees, and other migrants, the most powerful thing we do, something that can only happen in this radically different social arrangement, is to take on, willingly and by intention, some of the precariousness of their lives. This solidarity with the poor is why no one here is paid a salary, why full-time staff share housing and meals with our guests, live in the same conditions and eat the same food, showing them that they are valued and loved. This solidarity is more important now than ever.

And most importantly, in this space of freedom, we can welcome the stranger. This is a power that cannot be taken away, despite the xenophobia of our time. I am reminded in every conversation, and in every act of care at Casa Juan Diego, that this is my country too, and I get to decide how I respond to others. I get to welcome those that the Gospel wants me to love. This ability does not come from the government, but from a much higher power. In our Catholic Worker community, our band of sisters and brothers are as strong and as confident as ever in our commitment to the poor and to the works of mercy. In the Catholic Worker model, we get to dream and build the society that we want to see here on earth, a society based on the good of all.

1 Feed the hungry, give drink to the thirdly, shelter the homeless, visit the sick and imprisoned, bury the homeless, give money to the poor

2 Instruct the ignorant, counsel the doubtful, admonish the sinner, comfort the afflicted, forgive offenses willingly, bear wrongs patiently, and pray for the living and the dead.

3

“Carlos” comes to us at Casa Juan Diego in his late 20’s. When he was only a few months old, his mother abandoned the family and fled to another country. Twenty years later, she would call home to apologize to her children before she died. Carlos’ father later died from alcohol poisoning. From his midteenage years forward, Carlos is forced to work in the drug trade. He is also subjected to the most horrific tortures—to sexual degradation of the most unimaginable kinds. Carlos decides to flee to the United States through the Darien Gap, where he witnesses murder and rape along the journey. Corpses litter the route. He is kidnapped multiple times as he journeys through Mexico and has to bribe both cartels and state officials. He comes to us, not a broken man, but a man haunted by a past he cannot forget.

In the last issue of this paper, Louise Zwick wrote about a Christian and Catholic eschatology that is rooted in the here and now. Louise reminded us that Catholics do not endorse a “pie in the sky” eschatology. Catholics do not believe in a “massive escape project from location Earth.” After all, we pray each day that God’s will may be done “on earth” as it already is done in Heaven, and we work each day to build the Kingdom on earth. We are encouraged to “practice paradise” now. Our vision of eschatology involves the breaking of eternity into our temporality, here and now, as a seed of transformation that will bloom into the New Creation (Rev 21:1).

And yet… how will this New Creation come about? What about the deeply wounded memories of Carlos and of millions and billions of victims throughout the history of the world who have suffered similar fates?

Obviously, it is an insult to imply that they will be satisfied with “pie in the sky.” Yet… what eschatological hopes can they have? What hopes does our scarred planet have for the New Creation? How will God make things right in the end? How will that seed of eternity that we call the Kingdom of God grow into the New Creation when no end of suffering is in sight? The answer to these questions is also part of the Church’s escha-tological teaching. We as Christians are called to be, as Brennan Manning writes in The Ragamuffin Gospel, “eschatological heralds.” We have a message: At the Last Judgment God’s kingdom will come, and all will be made right or, as Julian of Norwich puts its succinctly, “all will be well!” (cf. 1 Cor 15:28)

And so, while Louise wrote about the eschatological hopes of victims now in our work for justice on their behalf, I want to continue her theme by writing about the Church’s eschatological hopes for victims in the New Creation, the world to come.

Dorothy Day was convinced that God would find a way to make all things right in the end. She writes in her diary entry for February 26, 1961: “My heart is wrung by the suffering in the world and I do so little. There was a picture in Newsweek of a dozen starving babies in the Congo, one tiny little one with his face in his hands. Terribly, terribly moving. The only consolation is that God will wipe away all tears from their eyes (emphasis mine).”

Dorothy writes this as an avid reader of Dostoevsky, knowing already Ivan’s objection to what she says in The Brothers Karamazov: “I have a childlike conviction that the

By Nathan W. O’Halloran

sufferings will be healed and smoothed over, that the whole offensive comedy of human contradictions will disappear like a pitiful mirage, a vile concoction of man’s Euclidean mind, feeble and puny as an atom, and that ultimately, at the world’s finale, in the moment of eternal harmony, there will occur and be revealed something so precious that it will suffice for all hearts, to allay all indignation, to redeem all human villainy, all bloodshed; it will suffice not only to make forgiveness possible, but also to justify everything that has happened with men—let this, let all of this come true and be revealed, but I do not accept it and do not want to accept it!“ (emphasis mine; 235-36)

As Ivan famously concludes his challenge to his brother Alyosha, he cannot accept a world that involves the inevitable suffering of just one little child. No amount of God “making things right in the end” can excuse this world for Ivan. No eschatological hope can fix this flaw in creation.

Is Ivan right? Is it enough for God to wipe away all tears in the end as Dorothy believed? Is it enough, as a friend once put it to me, that a victim, now held in God’s loving eschatological embrace, could say with complete honesty and joy: “I don’t regret being born because of the love and joy I now experience”?

Your answer to that question will probably depend on your intuitions about suffering and how much is too much for a good God to allow. But since I do believe in a creator God of you do let us ask what must happen for someone like Carlos to be able to experience the depths of heavenly bliss. Let us ask what must happen for the New Creation to become a true reality.

In C.S. Lewis’ eschatological novel

The Great Divorce which explores the transition from this life to the next, the character of George MacDonald explains:

“They say of some temporal suffering, “No future bliss can make up for it,” [Ivan’s objection] not knowing that Heaven, once attained, will work backwards and turn even that agony into a glory. And of some sinful pleasure they say “Let me have but this and I’ll take the consequences”: little dreaming how damnation will spread back and back into their past and contaminate the pleasure of the sin. Both processes begin even before death. The good man’s past begins to change so that his forgiven sins and remembered sorrows take on the quality of Heaven: the bad man’s past already conforms to his badness and is filled only with dreariness. And that is why...the Blessed will say “We have never lived anywhere except in Heaven; and the Lost, “We were always in Hell.” And both will speak truly.” (69)

Lewis’ insight here about how Heaven “will work backwards and turn even that agony into a glory” is profound and speaks directly to our question. But he still doesn’t quite tell us how this will happen, especially for the wounded, the victimized, the oppressed.

Artist: Angel Valdez

While the Church has a theology of Purgatory for the healing and purification of sinners, what about those who die wounded, abused, oppressed, having internalized a life spent in pain? How and when will Carlos heal if he has not found healing before death?

In his book The End of Memory, Lutheran theologian Miroslav Volf speculates that there are at least three ways that God will deal with our painful memories after we have died. First, some memories God will leave alone. They no longer cause pain (that difficult soccer practice; that lonely afternoon). Second, God will treat other memories “with the care of a healing hand and then abandon them to the darkness of nonremembrance” (that experience of sexual abuse, Volf’s own experience of interrogation and torture). Third, God will “gather and reframe the rest” (that painful experience with a family member; that memory of recovery from addiction) (192).

Now most of us probably have the most issue with the second way. The third makes a certain amount of sense to us. We have all had painful experiences that we have managed — whether on our own, with the help of friends, or with the help of grace — to reframe. We have experienced the “redemption” of pain. We have seen how God can heal and bring new meaning into our lives. When it comes to some of our painful past experiences, we can nod our heads in agreement with the Alcoholics Anonymous promise: “We will not regret the past nor wish to shut the door on it.” After all, this is certainly one of the profound implications of Jesus’ resurrected wounds. They remain even after the resurrection, although no longer causing pain. Jesus’ wounds teach us, as Jonathan Heaps argues, that “in the general Resurrection we might lovingly, tactilely honor one another’s risen, unhealed wounds. And, in turn, that we might not hide them from one another in shame, but instead offer them as Christ did, as now integral to our identity.”

And so perhaps I react negatively to Volf’s second way: how can Heaven be Heaven if some of my memories — even my wounded ones

— are banished “to the darkness of non-remembrance?” While a particular memory may be awful, it is still a part of me Or maybe my objection is even more profound: How can I say that something has truly been redeemed if the only way to deal with it is to banish it from my mind. Shouldn’t anything that has been redeemed in my life be integrated into some higher harmony of meaning? This idea, says Volf, is modern but not necessarily biblical. Yes, some of my painful memories will be reframed and reintegrated into a new and transformed heavenly life. But others may need to be banished.

Volf invites us to recall, for example, how Jesus deals with illness. In the Gospels, says Volf, “there is not even a hint that Jesus tried to give meaning to illnesses—especially not negative meaning as punishment for sin. Illness is not integrated in a whole; it is healed, removed. It presents an occasion for God’s glory to be revealed through deliverance, not for some theoretical lesson that life has meaning notwithstanding negative experiences” (187). His point is that while we may indeed find ways to find meaning in physical suffering— which is well and good—when Jesus healed, he banished. Banishment is part of the work of redemption. There are some experiences, some memories, that are so horrible that heavenly peace will only be bought at the price of their banishment and nonremembrance. Perhaps this is what Carlos will need most. Some wrongs suffered may need to be forgotten. As Isaiah 65:17 proclaims: “For I am about to create a new heavens and a new earth; the former things shall not be remembered or come to mind.”

However redemption happens — whether Heaps or Volf is right, whether by reintegration or by nonremembrance — my point is that victims must have the eschatological Gospel proclaimed to them, must hear the message that their tears will be wiped away in the eschatological embrace of the Father (Rev 7:17; 21:4).

Otherwise, what can they look forward to? Yes, Heaven begins on earth, but it must conclude in the New Creation. Victims deserve nothing less. Nor does their loving Father want anything less for them.

Finally, what about nonhuman creation? Will the wounds of nonhuman creation be eschatologically healed too?

After all, trees don’t have immortal souls, so why would they need healing in anticipation of the New Creation? Won’t God simply create new trees? Indeed, theologians have thought that way for a long time. But Pope Francis introduced a development into Catholic teaching on the New Creation in Laudato Si’ when he taught that “The very flowers of the field and the birds which his [Jesus’] human eyes contemplated and admired are now imbued with his radiant presence” (LS §100). Later he notes that “each creature” will be “resplendently transfigured” and will “take its rightful place” in the New Creation (LS §243). This development of teaching reminds us that nothing about this creation is dispensable or “throwaway.” God loves His creation so much and with such specificity that all of it will become part of the New Creation (Wis 11:24). St. Paul

already hints at this when he speaks of the reconciliation of “all things” by the Cross (Col 1:20) — not just human beings — and that “all creation” is awaiting to share in the freedom of the sons of God (Rom 8:19-22). But does nonhuman creation hang onto its wounds like human beings do? A dog doesn’t need Purgatory because it can’t sin. Similarly, then, it can’t hold onto moral injury either, right? Nonhuman creation will certainly not need healing and redemption in same way that free creatures do. Purgatory is primarily for the healing of the free human will, and nonhumans do not bear the injury of a wounded will. Creation has, however, been deeply wounded by human beings — as St. Paul attests in Romans 8. Therefore, I speculate that its transition to the New Creation too will involve its own kind of healing. God will heal the wounds of His creation, wounds that we have caused. Nothing in the New Creation will be created de novo or ex nihilo. All of it will be created ex vetere, out of the old. The book of Revelation does not imagine this process as another creatio ex nihilo but as a transformation and renewal of this creation. From the old, God will make “all things new” (Rev 21:5) All things. Both Carlos and abused creation. New.

References:

Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Jonathan Heaps. “The Monstrosity of Christ’s Resurrection.” Church Life Journal, April 18, 2022.

C.S. Lewis. The Great Divorce. HarperCollins, 2025.

Brennan Manning. The Ragamuffin Gospel. Multnomah Books, 2000.

Miroslav Volf. The End of Memory. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006.

Nathan is a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego

continued from page 1

A recent review article by Joshua Heath offers related insights of Eastern Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov from new translations of some of his writings, including several books and fragments that had not been previously published.

Bulgakov writes from the perspective of tragedy in world history, tragedy redeemed by the loving sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. Tragedy nonetheless, redeemed by Love.

Bulgakov contends, with the tradition of offering one’s sufferings, “Within the cosmic struggle between good and evil, the Christian, following Christ’s example, is called to unceasing sacrifice, or cross-bearing.” He is not only writing of us as individuals and of the concept of self-denial. Bulgakov speaks of the sacrifice of the Church itself through “participation in the eternal priesthood of Christ in the liturgy…”

We need not despair. Love is ultimately stronger than death. “Good does battle with evil principally through the active offering of sacrifice, or ‘co-dying’ with Christ.” (Bulgakov) “The Cross, as God’s voluntary assumption of death, shows love to be the internal—rather than strictly oppositional—overcoming of evil. Love’s operation is not an external resistance to or overcoming of evil, for good and evil are not, after all, two equal and opposing forces.

Bulgakov adds, mystically, that “… the supremacy of love is affirmed by love’s active transformation of the disintegration caused by evil and suffering into the voluntary return of what is lost as a sacrificial offering.”

“If the Christian life is a life of sacrifice, it is also a life of creativity.”

Bulgakov insists that creativity must accompany sacrifice: “[The liturgy] extends the scope of sacrifice to include the essential, creative, transforming or transmuting activity that is constitutive of life as such.” He actually states: ’Life and creativity are synonyms” and adds that if the Christian life is a life of sacrifice, then it is also a life of creativity.

This is explicit even in Bulgakov’s description of the Cross as “not only passive reception, but an active taking hold, creative self-definition and daring.” So a life of sacrifice is not boring, it is not only suffering, but can make a daring contribution to history.

Bulgakov posits that “History is not empty time just waiting to be filled. Instead, it stands before humanity and thus the Church as a task, the task of created life. Contributing to the Church’s task in history, the relation between creativity and sacrifice becomes yet more mutual, for the ‘responsible, creative intensity’ demanded of a Christian is to be exercised ‘not in their own name, but in the name of the Lord who has sent us into the world.’ “

Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day learned much from the French personalism of Emmanuel Mounier. In his discussions of the Christian vocation of each person, Mounier emphasized creativity and engagement in the world. Mounier, an intellectual, reminded his readers that availability is as important as any theory. “Availability is as essential as loyalty, the test of history as much as intellectual analysis.”

Mounier emphasized that sacrifice is not primarily a negative act. Rather it is an act of devotion and of adherence. To sacrifice is to offer oneself to another, to commit oneself to another, to be engagé (engaged). Availability is as demanding as any other sacrifice. Engagement and availability make life unpredictable.

Anyone who has ever been a Catholic Worker or worked in the service of the poor knows how demanding availability can be. As we are overwhelmed with the needs and situations of people who come to us at Casa Juan Diego, we know that availability is our sacrifice. One more person at the door (Christ in disguise), one more expressed need of our guests.

In the day-to-day life of each follower of the Nazarene, there are countless practical opportunities to embrace the Cross in being available as a part of our sacrifice. This idea of availability is closely related to Pope Francis’ concept of accompaniment with others in their pilgrimage.

One could take in a migrant family with nowhere to go, one could sit with an ill neighbor or help them with the basic needs of life, one

Within the cosmic struggle between good and evil, the Christian, following Christ’s example, is called to unceasing sacrifice, or cross-bearing.

— Sergei Bulgakov

could help a child get enrolled in school. The possibilities are endless. I think of one practical example of availability and accompaniment that anyone could imitate:

Ed Willock, whose drawing of “air-foam Christianity” was featured on the cover of the first issue of Integrity magazine (and reprinted here) had twelve children. He became very ill after several strokes. Mark Zwick and his mother (before I knew them) were visiting Dorothy Day one day in New York. After visiting for a while, Dorothy asked them if they would be willing to drive four of Ed Willock’s children up to New England to Mary Reed Newland, who would care for the children for a time. Mark and his mother were available, and they drove the children, joyfully.

In the past couple of years I have been reading some of the volumes on Church history by Henri Daniel-Rops. Those books bring out the creative, sometimes amazing role of the Church and the Saints in history during very difficult times, when all might have seemed hopeless.

Dorothy Day wrote about what we need for our times:

“Péguy said that the race of heroes and the race of saints stand in contradiction, the contradiction of the eternal and the temporal. He was writing of Joan of Arc, and he said that the two races meet in her, which meet nowhere else. We would say they meet also in Gandhi.With the bishops of the United States pointing out that the greatest danger of our age is secularism, it would seem that it is a time when we must beg God to raise up for our time men [and women] in whom saint and hero meet to solve the problems of the day. And not by war!” (The Catholic Worker, January 1953).

The Catholic Worker movement as begun and lived by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day was one of the very creative responses by lay people in the Church to bring the lived Gospel to the local community at a difficult moment in history, the Great Depression. We hope that Casa Juan Diego may be another.

We also know and with great hope believe that the lives of our readers are also a part of the ongoing creative responses to a difficult time in history, building up the Kingdom of God and caring for God’s people.

Let us be creative in our response to world crises, uniting our sacrifices with Christ on the Cross, and not be like Mr. Business, featured in one of Ed Willock’s jingles:

“Mr. Business went to Mass

He never missed a Sunday.

Mr. Business went to hell

For what he did on Monday.”

Let us continue to try to work creatively, doing the works of mercy that the Lord requires of us –in His name.

References:

Joshua Heath, “Review Essay: The Eternal Sacrifice,” Modern Theology 41:1, January 2025.

Eileen Cantin , Mounier; A Personalist View of History Paulist Press, 1973.

Pope Francis. Message of the Holy Father to Participants in the General Assembly of the Pontifical Academy for Life. “The End of the World? Crises, Responsibilities, Hopes.

Susan Gallagher contributed to this article.

continued from page 2

through city streets in search of churches serving free meals. Once, she passed out from exhaustion. Reflecting on my own pregnancy and times that I have found myself desperately, irrationally hungry, I nearly cried imagining another pregnant woman going without enough to eat. Later, I learned of the time a cartel member boarded their bus in Mexico and threatened to shoot Ari’s husband in the throat, until a fellow passenger bribed him away. As I thought about the deeper sense of dependence I’ve come to feel on my husband during my pregnancy, I could hardly fathom the trauma of facing such a close call with evil and death.

The stories of our guests regularly confront me with the age-old problem of evil, a mystery I’m certain I will never fully understand on this side of eternity. Yet, one reflection shared by a fellow Catholic Worker over dinner has stayed with me: that something essential about the problem of evil is revealed through Christ’s crucifixion. Jesus’s passion shows us that God is not One who subjects us to evil, but rather is One who entered humanity incarnationally and willingly suffered the worst agony and humiliation. God suffers our trials and heartache in solidarity with us. Not only that, He is constantly caring for us, even when we don’t understand how.

This faith shines through in many of our guests, who have lived through trials that would much sooner embitter me. Remarkably, they do not blame God. Though evil may exist, they see God in those critical moments of grace: God who provided that fellow passenger with money and the will to speak up, God who gave the strength to move forward despite exhaustion and brushes with death, God Who guided this little family to Casa Juan Diego, a safe refuge.

Learning from the courage and faith of our guests has freed me from fear, freed to focus the simple discomforts of and the joy of