CATHOLIC WORKER

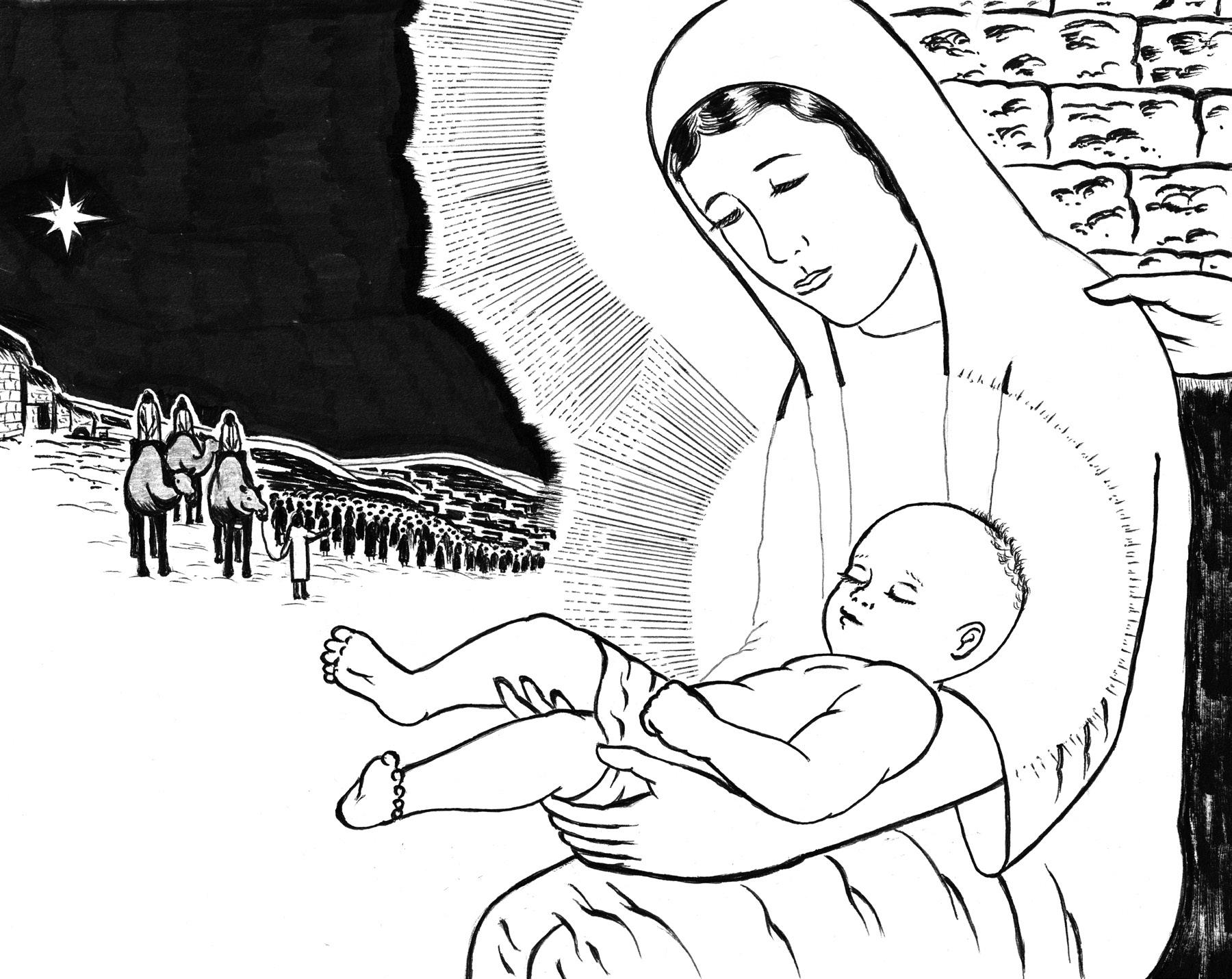

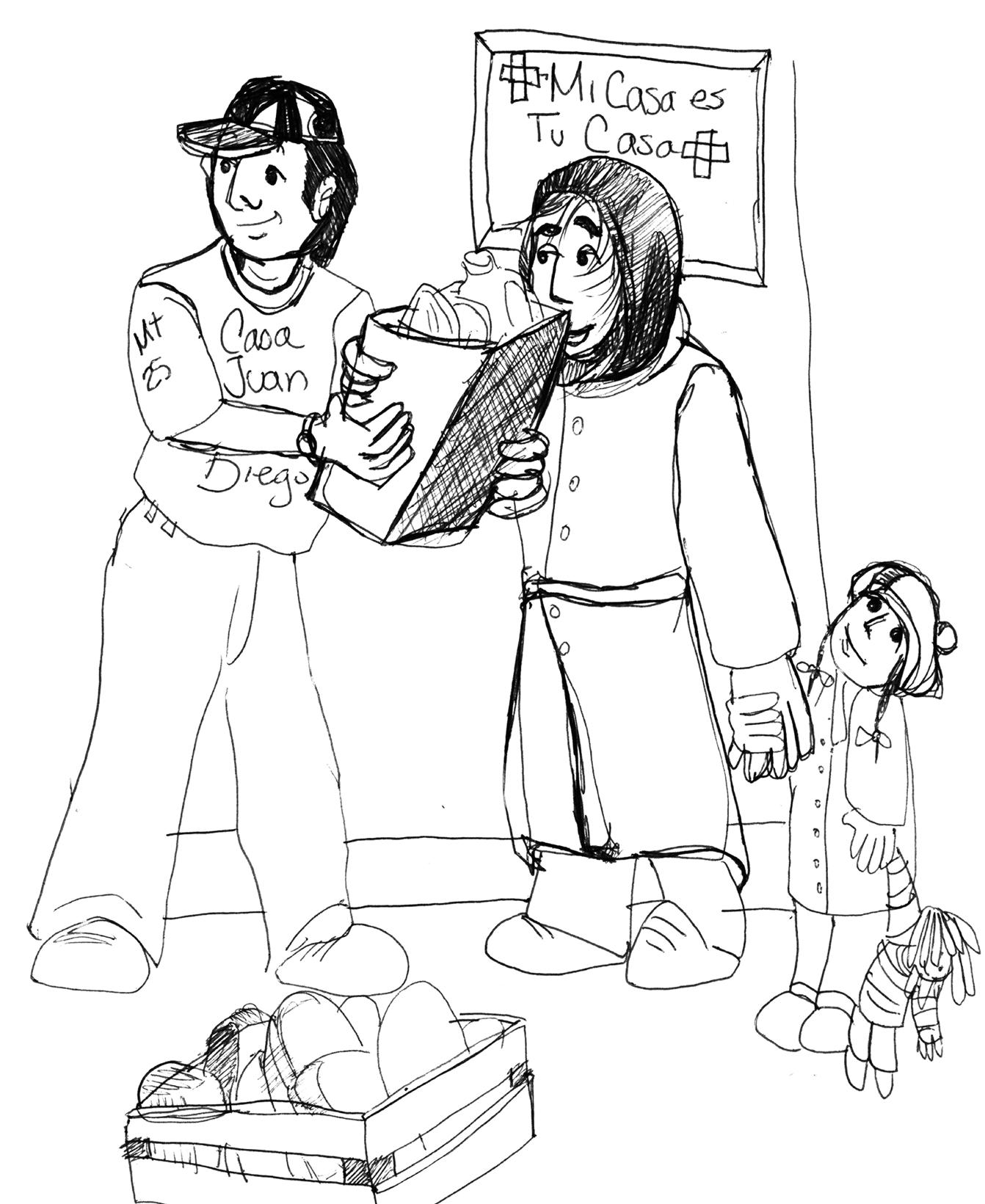

The joy of Christmas comes as a great gift, breaking into the despair, sadness, and fear of violence that surrounds us and others in many parts of the world. All the hype about Christmas shopping (since July 4) simply cannot drown out the Good News of this Silent Night: Jesus was born in a stable at Bethlehem with the poor! We are still in the stable at Casa Juan Diego, where we await Jesus in the person of the poor (Remember Matthew 25:31ff.: Jesus said: “What you do to one of these least ones, you do to me”) and daily Jesus comes.

He comes to us in men, women, and children, many who are traveling, seeking to avoid starvation for themselves and especially for their children. He comes in those who are black and blue or threatened with death or with their heads full of stitches, in those men who have been shot in the back, in those who have had their legs broken by thieves.

Many come to find a bed. Providing hospitality remains our hardest work as much can happen when people are with us day and night. Someone is always sick or has a serious illness or a baby is being born.

Each week a thousand hungry Houstonians also come for a bag of groceries and medicines at our clinics. With your help and that of the Houston Food Bank we manage to organize and distribute the food. (We buy rice and beans by the pallet.)

The worst thing about Casa Juan Diego is the constant stream of suffering, poverty, destitution, neglect, the victims of violence who come to our doors, the shadow of the Cross already present at the Incarnation. We are overwhelmed. We cannot receive all who come to stay.

But the best thing about Casa Juan Diego is the constant stream of suffering, poverty, destitution, neglect, the victims of violence against immigrants who come to our doors, which gives us the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and live out the Gospel. The hope of the Resurrection is there and is stronger than death. Yes, we are overwhelmed, but we survive, by God’s grace, through faith working in love. Amazing Grace!

We are writing to ask your help with the “best thing” about Casa Juan Diego. We need you as much as we need the poor to live out the Gospel. If you are able to send a gift, it will be a participation in our works of mercy and will go to the poor. There are no salaries at Casa Juan Diego. We also need your prayers. Many, many thanks. May the spirit of Christmas be with you as you celebrate faith above the din of Christmas shopping.

Very gratefully,

Louise Zwick and all at Casa Juan Diego

Donations may be dropped off or shipped to:

Casa Juan Diego 4818 Rose Street Houston, TX 77007

• Hooded sweatshirts for men, women, and children

• Blankets

• Twin size sheets

• Pillows

• Men’s jeans sizes 27-36

• Tennis shoes for men, women, and children

• Underwear for children

• Baby wipes

• Baby formula

• Adult diapers

• Underpads

• Pots and pans, dishes and silverware

• Shampoo

• Toothpaste

• Deodorant for men

• Disposable razors

• Bodywash

• Cooking oil – olive or vegetable oil

• Canned vegetables, low sodium

• Tuna or canned chicken

Become a full-time Catholic Worker. Room & board and health insurance provided. Married couples welcome. If you can help, please email us at info@cjd.org.

Casa Juan Diego was founded in 1980, following the Catholic Worker model of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to serve immigrants and refugees and the poor. From one small house it has grown to ten houses. Casa Juan Diego publishes a newspaper, the Houston Catholic Worker, four times a year to share the values of the Catholic Worker movement and the stories of the immigrants and refugees uprooted by the realities of the global economy.

• Food Donation Central Office: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Women’s House of Hospitality: Hospitality and services for immigrant women and children

• Assistance to paralyzed or seriously ill immigrants living in the community.

Casa Don Marcos Men’s House: For refugee men new to the country.

Casa Don Bosco: For sick and wounded men.

• Casa Maria Social Service Center and Medical Clinic: 6101 Edgemoor, Houston, TX 77081

Casa Juan Diego Medical Clinic

• Food Distribution Center: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Liturgy: In Spanish Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. 4811 Lillian at Shepherd

Funding:

Casa Juan Diego is funded by voluntary contributions.

EDITORS Louise Zwick & Susan Gallagher

TRANSLATORS Blanca Flores, Sofía Rubio, Lupita Guzman

CATHOLIC WORKERS Dawn McCarty, Marie Abernethy Meg Thompson, Priscilla Acuña-Mena, Kevin Mcleod Nathan O’Halloran, Joachim Zwick, Louise Zwick

TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Joachim Zwick

DESIGN Bea Garcia Castillo

CIRCULATION Stephen Lucas

AYUDANTES TEAM........................... Wilmer Salazar, Ramiro Rescalvo Julian Juárez, Daniel De la Garza, Juan Manuel Chavez Diego Contreras, Frowan Zambrano, Michael Tandloy, Ever Cuero Williams Huerta, Steven Manzano

PERMANENT SUPPORT GROUP................ Louise Zwick, Stephen Lucas

Dawn McCarty, Andy Durham, Betsy Escobar, Kent Keith Julia Gallagher, Monica Creixell, Pam Janks Monica Hatcher, Joachim Zwick

VOLUNTEER DOCTORS................................. Drs. John Butler, Yu Wah

Wm. Lindsey, Laura Porterfield

Darío Zuñiga, Roseanne Popp, CCVI, Enrique Batres

Homero Anchondo, Deepa Iyengar, Mohammed Zare

Maya Mayekar, Joan Killen, Stella Fitzgibbons

VOLUNTEER DENTISTS.................Drs. Justin Seaman, Michael Morris

Peter Gambertoglio, Mercedes Berger, Jose Lopez

Maged Shokralla, Florence Zare

CASA MARIA.....................................Juliana Zapata and Manuel Soto

Receiving the Lord in the poor, the stranger, the broken-hearted

By Louise Zwick

It seems that sometimes we Catholics neglect to mention that the Lord Jesus explicitly told us why he was sent by the Spirit of the Lord, as he quoted the Old Testament prophecy. Recent experiences reminded us.

We received a call from a hospital asking if we could accept an 18-year old mother of tiny twin babies who had nowhere to go. She had not been too long in the United States. We rejoiced that we had space for her. When the baby girls arrived, the women of the house rose up in solidarity to help with them.

We had just recently received a woman whose brother was killed by gangs in Ecuador. Three men who had lost a leg or had one crushed also came to ask for help. A man who is blind from an assault on the street came again for help (We have helped him travel to Harvard for experimental treatment for his eyes).

These experiences brought to mind the Lord’s own explanation of his Incarnation on our earth. The Lord’s words are recorded in chapter 4 of St. Luke’s Gospel:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring glad tidings to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, and to proclaim a year acceptable to the Lord.

He said to them, “Today this Scripture passage (from the book of Isaiah) is fulfilled in your hearing.”

Mary’s song, the Magnificat, known and loved by so many generations, affirms this mission that the Lord spelled out for us:

My soul magnifies the Lord

And my spirit rejoices in God my Savior; Because He has regarded the lowliness of His handmaid; For behold, henceforth all generations shall call me blessed; Because He who is mighty has done great things for me, and holy is His name; And His mercy is from generation to generation on those who fear Him.

He has shown might with His arm, He has scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart. He has put down the mighty from their thrones, and has exalted the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich He has sent away empty.

He has given help to Israel, his servant, mindful of His mercy Even as he spoke to our fathers, to Abraham and to his posterity forever.

The refugees and the poor who come to us are often considered the lowly. The Incarnation, Christ’s presence in our world, is the heart of the mystery of Christianity. We are grateful to be able to participate in his mission of bringing glad tidings and practical help to the poor and those who have suffered.

We do not always talk a lot about the Bible to people who come to us, but we are present here. We usually do not know whether those who come to our door for help are believers or not. We not preach at our door. Our way of sharing the Gospel has been with the priests who have rotated in to celebrate Mass on Wednesday evenings for those who are staying at our houses of hospitality.

Dorothy Day did not emphasize proselytizing to the poor. We also do not distinguish among those who come to us for help who are believers or non-believers, worthy or unworthy, although we frequently discover that the poor and those who have suffered very much do put their hope in God. We try to listen to what people ask of us, even though often we cannot solve their problems.

We sometimes identify with the comment of Georges Bernanos’: “Pious persons doubtless have a lot of things to say to unbelievers, but often they could also have a lot of things to learn from these unhappy brothers, and they risk never knowing what those things were because they never stop talking.” (Hans Urs von Balthasar, Bernanos, An Ecclesial Existence).

Hans Urs von Balthasar, like many recent Popes, emphasizes the idea of mission, following Jesus in our lives, given for the world: “Balthasar ‘s idea of ethics, while acknowledging the value of natural law, underscores that Christ is the concrete norm of Christian ethics, which dramatically transformed the meaning of Christian self-understandings of moral existence in terms of mission and discipleship” (Carolyn A. Chau, Solidarity with the World, p. 129).

We know from the Lord’s own words and example that Christian mission and discipleship emphasize the poor and those who suffer, not just the successful. The Incarnation is for all.

As Tony Magliano recently wrote: “For almighty God revealed in the clearest ways the inestimable worth of humanity by humbly becoming one of us, walking with us, teaching us, suffering for us, dying for us, and rising from the dead for us!”

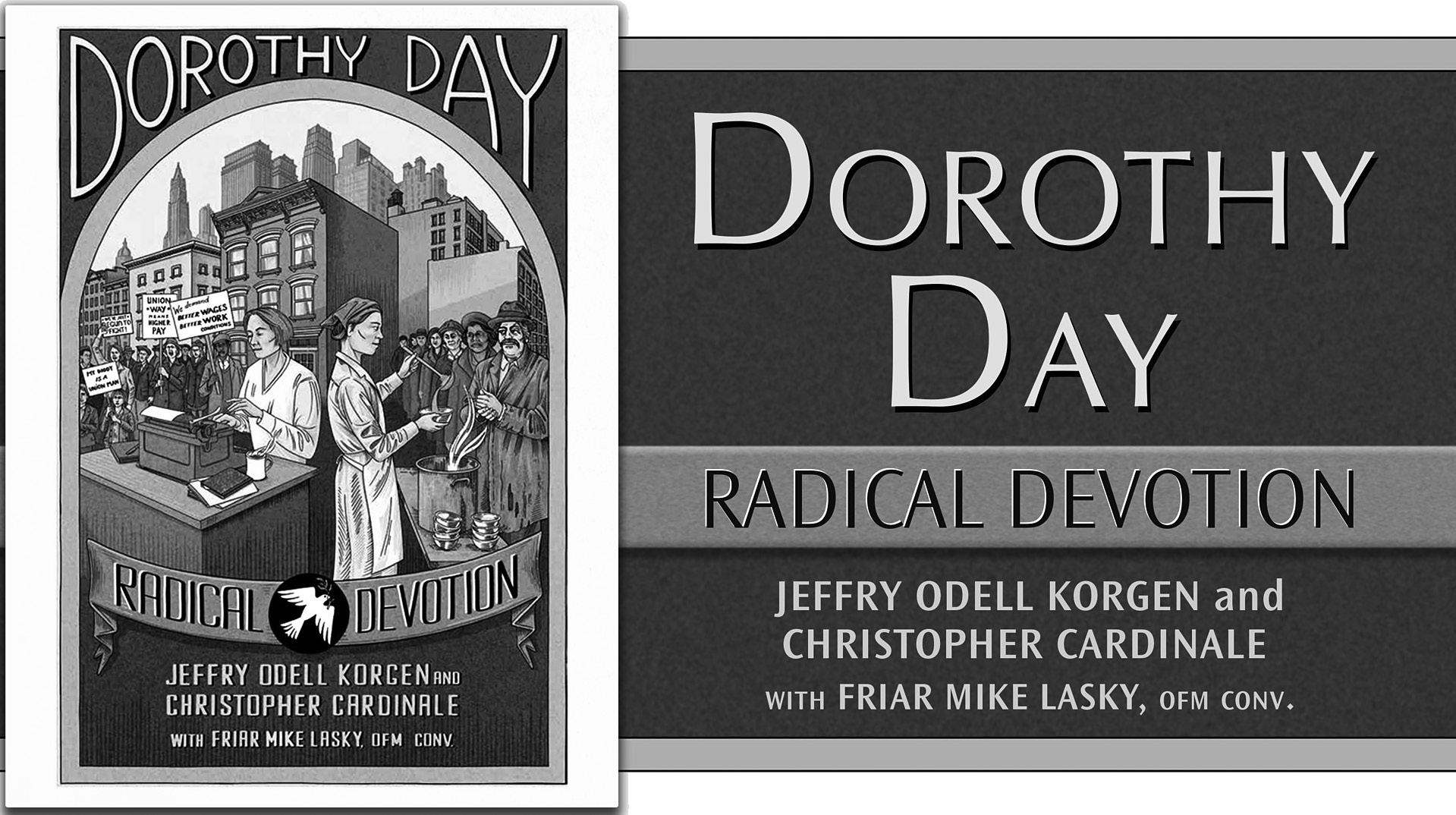

Written by Jeffry Odell Korgen and Friar Mike Lasky, OFM Conv.

Illustrated by Christopher Cardinale

Paulist Press | 106 pp.

Reviewed by Evan Bednarz

With the canonization process moving ahead for Dorothy Day, interest continues to grow for the Servant of God who famously said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” Biographer and granddaughter Kate Hennessy warned, “If we continue to narrow down who she was, that does a disservice to not only her, but to us.” To its great credit, the new graphic novel from Paulist Press, Dorothy Day: Radical Devotion, resists any hagiographical pull, allowing the person of Dorothy Day to speak through a vivid and honest rendering, recognizing that sanctity speaks for itself.

The graphic novel is a particularly suitable form for someone so on the move as Dorothy was, who entitled her long-term column, ‘On Pilgrimage.’ The story begins in 1906 Oakland, as Dorothy and the Day family are awakened by the great San Francisco earthquake across the bay. Illustrator Cardinale’s use of color tone and linework evokes a sense of movement that will set the tone for the remainder of the book. In the aftermath of the earthquake, thousands of refugees stream into Oakland, with the community responding with a hospitality that seemed to have impressed itself upon the eightyear-old Dorothy. “Mother, why can’t people treat each other like this all the time?,” foreshadowing her radical embrace of the Gospel.

In a little over 100 pages, the book packs in an impressive amount of biographical information without losing any figurative or literal color. As a cub reporter, we see Dorothy step off a streetcar and into the tumult of WWI-era New York City, where she documents the dignity and squalor of tenement living, rubbing shoulders with labor and literary icons such as John Reed and Eugene O’Neill.

After depicting Dorothy’s formative experience picketing for women’s suffrage and being thrown in jail for it, the book details a conversation between Dorothy and O’Neill over the course of a Greenwich Village night. Dorothy is taken by the playwright’s barroom recitation of poem ‘The Hound of Heaven.’ Deftly portrayed, the conversation becomes a cipher for clashing worldviews; while each feel themselves haunted and pursued by God, it is Dorothy who will let herself be found.

Then begins one of the most formally impressive sequences of the book. Each panel’s coloration is gradually desaturated into blue, beginning when a mutual friend overdoses on heroin. As Day rushes to tend to him, O’Neill is nowhere to be seen. She confronts him about their friend. “It’s not my mess,” he replies, and Day realizes a painful truth to which she will frequently return, courtesy of Dostoevsky — love in dreams is easy, love in action is hard.

Day falls in love and becomes pregnant by a vagabond journalist who tells her to get an abortion. She travels to Chicago for the procedure, and the experience is heartbreakingly illustrated with little dialogue, as the frames juxtapose the barrenness

Her story began with an earthquake, and it’s a fitting metaphor; the Catholic Worker movement continues to reverberate...

of the doctor’s office with Day imagining herself being embraced and possibly forgiven by a woman on a labor poster in the office. We see in a closeup of her face the physical and spiritual agony she undergoes. She tries to commit suicide, marries then divorces, and struggles to incorporate her faith without any community. It is when she moves out to Staten Island and meets Forster Batterham that light reappears, emerging over the horizon. To her surprised delight, she becomes pregnant. Creative sequences such as these weave throughout the novel. For example, see the juxtaposed versions of the infamous “Coffee Cup

Mass” or the rendering of the FBI’s dossier on Dorothy. When Peter Maurin and Day providentially meet and begin speaking about what will become the Catholic Worker, we get a clear sense for Maurin’s legendary appetite for conversation, fluttering about panels explicating his “three-point program” of cult, culture, and cultivation. The Catholic Worker movement began, and continues, in a culture of discussion, collaboration, and prayer, a dynamic framework which will lead it from Depression-era breadlines to protesting with Cesar Chavez in the 1970s and on into the 21stcentury.

Many reading will be familiar with major events of Dorothy’s life in the Catholic Worker and they need no rehashing here. The text and dialogue narrating the book are solidly crafted and impressively informative, contextualized by historical notes, so that even those well-versed in the CW movement might learn something new: for instance, I had no idea that the eminent poet W.H. Auden met Dorothy and financially supported the Worker. As a whole, Radical Devotion exceedingly accomplishes its purpose to introduce the life and holiness of Dorothy Day. What one comes away with is a better understanding of Dorothy’s distinctive pilgrimage, from someone who might have remained passive before the accidents of history, toward a vocation of Gospel witness actively shaping the times through which she moved.

Her story began with an earthquake, and it’s a fitting metaphor; the Catholic Worker movement continues to reverberate, as illustrated on the last page: food delivery in the Philippines, hospitality in Indiana, a farm in Nashville, a non-violent protest of the Keystone Pipeline in Iowa. I got my feet wet at Casa Juan Diego in 2019, enduring those first turbulent months of COVID alongside a community I continue to cherish in my heart. Against my window rests the Eichenberg print, ‘Christ of the Breadlines,’ given at the end of my CJD tenure and signed by my fellow CWers. It is impossible to imagine all the loaves and fishes given over the years through the movement Dorothy led. “It all just came about,” she wrote at the end of The Long Loneliness. “It just happened… it is still going on.”

By Mary Chen

It was the winter of 2022, and I was in my last year of undergraduate studies in biology at the University of Notre Dame. I decided to spend a gap year between graduation and starting medical school, so I planned a trip to the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati in New Mexico to discern a gap year of service. It just so happened that Title 42, the COVID-19 public health restriction affecting migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, was ending. In the middle of winter, thousands of migrant families and children lined up outside of a few shelters in downtown El Paso. With this image ingrained in my head on the flight home, I made a vow to spend my gap year to provide a ministry of accompaniment.

My introduction to Casa Juan Diego, a Catholic Worker House of Hospitality in Houston, was serendipitous. Two past volunteers from Notre Dame happened to be some of my closest friends.

During one lunch at the dining hall with summer volunteer Lorenza, she remarked that Casa, as the place is affectionately known, is a special place because God’s love is made present through action. I discerned that Casa would enable me to give back to others, and I committed to a year of service at the Houston Catholic Worker.

Immediately upon my arrival at the shelter, I was launched into action, greeting house guests in Spanish and making the acquaintance of the only Chinese guest in the house. We talked for over an hour in Mandarin Chinese about her frightening journey to the U.S. Her voice quivered describing her journey from Brazil to the U.S. Mexico border, her separation from her travel partner in the detention center, and signing papers written in English that she couldn’t read. I learned that this was her first real conversation since she arrived at Casa a few months ago. One of my fellow Workers, Marjorie, remarked that the change in her was noticeable: from quiet and scared, to now smiling and laughing.

From the simple act of hearing the stories of the migrants, I started to receive the gifts of these people and their lives. When language failed, living in community was enough to bridge the gap.

I began to recognize the limitations of one house in addressing all the needs of newly arriving migrants in Houston. From turning away families with teenage boys we lack the capacity to house, to exceeding our maximum capacity by housing a family in the clinic, I found myself questioning just how much change I was actually making. When I brought up these questions to the co-founder of Casa, Louise Zwick, she commented that this was our reality as Catholics; even in a society that sympathized with the poor and vulnerable, there will always be more work to be done.

When our human solutions fail, God always provides. Just when I gave up hope of helping a father and his teenage son, a solution arrived: an organization in Houston who connects families looking for shelter with other migrant families who volunteer to house them. When just about all the underwear or pillows have been given away, a donation arrives. Doctors, medical students, and volunteers showing up to the clinic week after week. I often have thought, “How are these people going to afford paying the monthly rent after they move out of Casa without the ability to work?” I like to think that God rovides other people to help them.

Working in a broken system can be frustrating. At our weekly “Clarification of Thought” discussions on Wednesday, I learned an important lesson. Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, believed that what was needed to change society for the better was not a violent revolution, but a “revolution of the heart.”

Here at the Houston Catholic Worker, I started to believe that our real work as Christians is not creating a political or social program; rather, our very actions that uphold the dignity of the person are a revolutionary fight against the forces that degrade and dehumanize mankind.

What was supposed to be a year of creating change turned into a year of being changed. At Casa Juan Diego, my heart was transformed to love Christ in the disguise of the poor.

By: Dawn McCarty, Ph.D., LMSW

The guests living in our Casa Juan Diego Houses of Hospitality, along with the Workers who live and work there, eat the same food, together. Our meals are simple, nourishing, and lovely at times. Feeding and serving food happens all the time at Casa Juan Diego as an act of generosity and love. Food, however, has been important to the development and history of Casa Juan Diego, and to the entire Catholic Worker Movement.

I recently attended the inaugural Peter Maurin Conference in Chicago.

Peter was the “Theologian” and “Philosopher” while Dorothy Day was the “Worker,” starting the first Catholic Worker House of Hospitality in Manhattan in 1933, offering food first, then clothing and hospitality to those devastated by the Great Depression.

The movement has spread worldwide, and according to the Wikipedia article “Catholic Worker Movement” (a must read!), “the movement claims over 240 local Catholic Worker communities providing social services. Each house has a different mission, going about the work of social justice in its own way, suited to its local region.”

I guess I knew that intellectually, but in talking with Catholic Workers from all over the country, I understood for the first time how diverse the different communities are. Some, like Casa Juan Diego, are very Catholic, others are more secular. Some concentrate on the guests living in their Houses of Hospitality, others, like Casa Juan Diego, are also very much involved with the surrounding community. And I was surprised by the fact that many Catholic Worker communities, particularly ones started recently, do not have a house at all!

So, what is the common denominator of all these very different Catholic Worker communities? I think that what they have in common, and the only thing they have in common, is a dedication to one or more of the corporal Works of Mercy: feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, sheltering the homeless, visiting the sick, visiting the prisoners, burying the dead, and giving alms to the poor. Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day remind us that we cannot love Christ with-out loving our neighbor, and loving them not in theory, but con-cretely, loving them in their bodily needs.

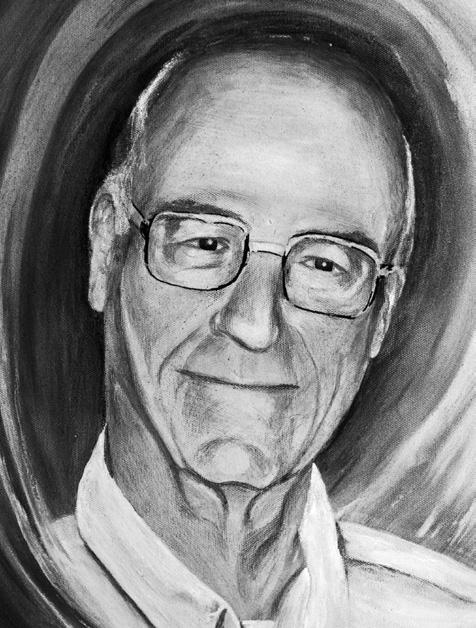

Artist: Angel Valdez

later to the Food Bank each week. Volunteers at Casa Juan Diego helped distribute the food. Mark firmly believed that the two pounds of rice and two pounds of beans we gave out to every adult was vital not only because people were hungry, but also because it supported and affirmed the culture of the many new immigrants arriving at the time.

As early as the May 1982 edition of the Houston Catholic Worker newspaper, Mark described the food given in the early years: “We feed many families by putting soup in their kitchens. With a bag of groceries costing less than $10.00 we can feed a family of 6 for a number of days. Basic foods are provided: 5 pounds of wheat flour, 2 pounds of rice, 2 pounds of pinto beans, 5 pounds of masa harina (corn flour), oatmeal, powdered

The focus of Casa Juan Diego at its founding in 1980 was at first on sheltering the homeless, specifically the homeless refugees from the genocidal civil war in El Salvador. The Houston House was modeled in many ways on Mary House, which Dorothy Day started almost fifty years previously – a House of Hospitality where guests and Workers lived together in community, with the Workers taking no salary and the House accepting no money from the government. All work relying solely on the generosity of donors and the grace of God. Getting the homeless off the streets in our part of Houston was a priority in the early days, but the importance of feeding the hungry who remained on the street was an obvious need, too. Mark Zwick, our co-founder, turned outward to the surrounding refuge community first by starting a food distribution to our hungry neighbors. He would drive a van, and later a large truck (today people know it as the Guadalupe truck) to Reyes Produce and then

milk, shortening. At times we add peanut butter, tuna, bread, and donated goods. Thus, with several hundred dollars and donated goods we can feed many families for a long period. However, people have to be really hungry to appreciate this diet. The majority of people who come for food at Casa Juan Diego come only once or twice. We do provide long-term support to several people who are blind, crippled or incapacitated in some way, who can’t receive assistance from any agency because their papers are not in order. The traditional soup kitchen clientele, young and old transients, alcoholics, former ‘institutionalized persons’ and elderly do come to Casa Juan Diego and are served.” Although the beginnings were small, today Casa Juan Diego is a major source of nutrition and food security for our community. Before Hurricane Harvey, the largest rainfall event in US history, we were serving about 300 families each week through our food distribution. I knew almost all of them! As people passed through for food we had conversations about health, family, and life events, and along with a dedicated group of volunteers, we not only fed people, we developed a Tuesday morning despensa community.

After Harvey, that all changed. When we were able to restart our distribution, the numbers of participants had more than doubled. I frequently tell people that the low-income and undocumented immigrant community of Houston never really recovered from Harvey. The people doing much of the recovery work never were able to recover themselves. Their apartments or houses were not restored, their loss of work was never made up, their savings were not replaced. Those without papers do not qualify for federal benefits, so they took the losses and kept on working to rebuild the city, even though unscrupulous contractors often paid less than the minimum wage or paid not at all. And then, there was the pandemic.

The ensuing crashing of the economy, which hit the immigrant and low-income communities the hardest, increased both hunger and the anxiety of not knowing

My name is Mirabel, and this is my story. Uncertainties and happenings sometimes make one wonder where to call home, what to eat next, where to find safety, and how to live without feeling empty. Casa Juan Diego in Houston, Texas, was that place for me at the right time, place and with the right people just ready to embrace me, fill my heart with love, shelter me, feed me, and provide me with a safe place to live. It’s because of these services provided to me that I still consider the place home, over 20 years since I last lived there.

With Casa Juan Diego’s modest means, I did not feel starved because they shared all they had. I lived there for a while and had nothing to give back since I had nothing to share. Nevertheless, I had the kindness to share with those who lived there at the time as we all were strangers to each other. Though feeling like strangers, we did not call ourselves strangers as the food was served from one kitchen to one long table as we gathered around it to eat.

if you could feed your family. Our weekly food distribution went from 600 families a week to nearly 1,200 families, where it stands today. Sometimes I am in awe at the miracle of the Catholic Worker model, that we can continue this volume of work and care for the community without paid staff. As was the case with Hurricane Harvey, after most Houstonians have recovered from the pandemic, our neighbors have not. Requests for food and rent assistance continues to rise. And while we can no longer provide groceries to a family of six for ten dollars, thanks to our generous donors we are keeping up with the increased cost of feeding the increased numbers, but just barely.

The Christmas holidays are always our busiest time of the year. More people will need food, and people in general seem drawn to our mission and our work like no other time. These Works of Mercy, especially feeding the hungry, are compelling to the human heart, and the Christmas story, a story of migration - an unsheltered and very pregnant mother far from home, hungry, afraid - is more relevant today than ever. The reasons that she and others like her fled, in desperate need of safety, shelter, and care, may have changed over the centuries, but Mary, as a universal symbol of those who must rely on the hospitality of strangers, is ever present at our door.

Although it has been many years since I moved out to start living on my own, I must say that my transition would not have been possible without the support of Mark (RIP) and Louisa Zwick. Moreover, all the volunteers working there during my sojourn were my angels. As I look back, I feel lucky that I now have a second mother because of my stay there. Consequently, my heart’s desire is always to come back to say “Thank you.”

After I obtained my legal status, I moved out of Casa Juan Diego to further my education. I can help others today because I was helped and supported. I pursued a nursing career, starting off as a caregiver then a nurse and now a Family Nurse Practitioner who goes out every day to care for vulnerable populations such as the elderly patients with chronic and multi-morbid conditions.

My journey, which started at Casa Juan Diego, has given me extra compassion and reality firsthand as to what others go through every day. Currently, as I work on my doctorate in Nursing and Psychiatry, I continue to feel thankful to my roots and that is Casa Juan Diego: a place I proudly call home. Thank you for feeding me when I had nothing to eat, clothing me when I had few or no clothes, and providing me with a safe space to stay when I felt homeless. My profile today is because you watered my roots. I am forever grateful, and I can only continue your act of kindness to others wherever I find myself with others who need assistance.

— Mirabel

By Renee Roden

The Peter Maurin Conference was, from the beginning, a labor of love. A group of 12 gathered over Zoom in early 2023 to discuss plans for a Peter Maurin conference in Chicago. Why Chicago, for a conference dedicated to a man born in France, who became famous in Union Square, and was buried in New York City?

Peter told Dorothy Day that, for many years, he did not live as a Catholic should. But after a decade of living in Chicago, Peter left for Mount Tremper, New York. There, he began practicing voluntary poverty and formulating the keen social analysis that would become his “Easy Essays.” Although the “hidden years” of Peter Maurin’s wanderings across North America are hard to unravel, it seems likely that it was during Peter’s life as a French teacher in Chicago that he experienced some kind of deeper conversion back to “living as a Catholic should.”

A century after Peter moved to Chicago, the Peter Maurin Conference began to take root. In the spring of 2017, The Catholic Worker noted both a lack of Peter Maurin in the daily life at Maryhouse in New York City and a renewed interest in Peter Maurin.

“Peter Maurin, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, seems more out of the picture in our everyday lives here,” a correspondent from Maryhouse wrote in The Catholic Worker in June 2017. “[Dorothy Day] is more, you could say, ‘in the news.’”

But the correspondent points to a small Peter Maurin renaissance bubbling: a front-page article by James Murphy, then at St. Joseph Catholic Worker in Rochester, about his trip to Peter Maurin’s homeland, and a subsequent Friday Night Meeting held about James’ experiences in France, meeting Peter Maurin’s surviving relatives. The Maryhouse writer even describes a small impromptu celebration for Peter’s death anniversary on May 15, following a donation of pies.

The Peter Maurin Conference was a scholarly conference—organized in cooperation with Loyola University Chicago’s Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage and DePaul University’s Catholic Studies Department—but it was not an academic conference.

The Peter Maurin Conference was held at a parish to represent Peter’s call to the Catholic Church to “blow the dynamite” of Catholic Social Teaching. The vision Peter laid out in his program was a program for Catholic communities, including parishes. Many of Peter Maurin’s original pleas for the Green Revolution, hospitality and the reconstruction of the social order were directed at parishes, dioceses, priests,

It was easy to imagine Peter Maurin’s Easy Essays first recited in a hall just like this one. More than 100 attendees—from California to France, some veterans and some novices in houses of hospitality, some curious about Dorothy Day and her teacher, some experts, many young, some old, and all yearning for a way to make a society where it is easier to be good—came to learn more about Peter Maurin and discuss his vision, his sources, and its practical application to the problems of the world today.

Seven years later, James was one of the organizers for the Peter Maurin Conference held September 6-8 at St. Gregory’s Hall, part of Mary, Mother of God Parish on Chicago’s north side.

One of the key takeaways from that Zoom call a year before was that a scholarly investigation of Peter’s life, his thought and sources, and his program in the world today should be free of the trappings of an academic conference–“the country club vibes”–as one advisor called them. A gathering to celebrate the thought of a scholar who was once mistaken for a homeless bum ought to eschew catered canapés or tweedy happy hours.

and bishops. According to the Second Vatican Council, the laity have a vocation to “seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God” (Lumen Gentium §31). “The laity consecrate the world itself to God” (LG §34). The conference wanted to bring Catholic action back to the very parish communities who are responsible for Catholic action.

The conference took place in the basement of St. Gregory the Great’s parish gymnasium, with an antique electric Bingo sign still hanging on the wall, chairs dating from the Baby Boom, and a decor reminiscent of the mid-century.

The conference began, of course, with concocting a giant pot of soup. Emily and Spencer Hess and their compatriots from Maurin Academy were the chefs de cuisine, and they led a line of sous chefs that gave lie to the proverbial wisdom that there can ever be too many cooks in one kitchen. The volunteer kitchen staff featured rotating volunteers, included Stefan Gigacz of the Australian Cardijn Institute, Tommy Cornell of Peter Maurin Farm in Marlborough, New York, Matthieu Langlois of Fordham University, and other conference-goers—including two of the youngest attendees from St. Peter Claver Catholic Worker in South Bend, IN— who walked into the kitchen and offered to slice, stir, season and serve. After dinner, Jon Sozek of Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, Connecticut gave his keynote: a clarification of thought on “personalism in the streets.” Sozek distinguished Peter’s personalism from both the personalism of Emmanuel Mounier in France and the Polish branch that bore fruit in Pope John Paul II. The personalism of Peter Maurin, lived in community, put in action through Catholic Social Action, he said incarnates Pope Francis’ call to encounter. He called it, “lightning bolt personalism.” Personalism is so hard to define, Sozek said, because it is about encounter, about leaving room for the Spirit to move between oneself and one’s neighbor.

Lincoln Rice of Marquette University gave the second keynote Saturday morning, guiding participants at the conference through Peter’s first year of Easy Essays published in The Catholic Worker newspaper. After breakfast and Lincoln’s talk, participants split into three roundtable discussions, one on Peter’s influences: JeanBaptiste de la Salle and the Christian Brothers and Marc Sanguier and Le Sillon. Another on Maritain and Berdyaev, key influences of Peter Maurin’s ideas. A third discussed protest, resistance, and the role of the Christian in history, and was led by a veteran of the movement and one of the newest Catholic Workers. Brian Terrell, of Strangers and

Guests Catholic Worker Farm in Maloy, Iowa dialogued with Jeromiah Taylor, who just began Vulnera Christi Catholic Worker in Wichita, Kansas, last year.

In the afternoon, another three concurrent Roundtable Discussions were held, one on voluntary poverty, another on Peter Maurin’s agronomic university and his economic vision, and a third featured Harry Murray, professor emeritus of sociology at Nazareth College. Murray spoke about a prolific writing project Peter Maurin embarked upon: “arrangements” or free-verse summaries of different theological, sociological, and philosophical texts. Visitors to the Catholic Worker archives at Marquette University will see folders upon folders of these arrangements in boxes of Peter Maurin’s papers. They are a rich educational resource Maurin created, waiting to be tapped.

Participants from the various roundtable discussions remarked on the unique tone of the conference. The roundtables were scholarly, revolving around the discussion of ideas–some more technical and precise than others–but the discussions were free-flowing. Voices from every walk of life had a chance to chime in, and the discussions were markedly inter-generational in their composition. White-haired elders dialogued with recent college graduates. Previous generations of Catholic Workers chatted with youngsters. Folks who had experienced or were experiencing homelessness broke bread with bishops and judges. The dynamite was being blown.

On Saturday evening, we shared Easy Essays of Peter’s and of our own creation, original poetry, and reflections on the conference. It was an evening of laughter and joy. One poignant moment was when our friend Tracy, a core member at the parish’s post-Soup Kitchen Bible Study on Tuesday nights, read Peter Maurin’s Easy Essay, “Houses of Hospitality”:

We need Houses of Hospitality to give to the rich the opportunity to serve the poor.

We need Houses of Hospitality to bring the scholars to the workers or the workers to the scholars.

We need Houses of Hospitality to bring back to institutions the technique to institutions.

We need Houses of Hospitality to show what idealism looks like when it is practiced.

When I asked her why she chose that Easy Essay, Tracy said, “Because it’s important. We need hospitality.”

Throughout the weekend, the conference sold copies of our friend Colin Miller’s book, We are Only Saved Together (Ave Maria Press). Colin’s book describes, so clearly, what Dorothy and Peter were trying to inspire in their readers: the social connotations of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, a love for the poor, and an emphasis on a community that welcomes others. In following this creative plan for a Christian community, Colin finds that they created “a people where there once was no people.”

That, in a nutshell, was my experience of the conference. At the beginning of the weekend, we were individuals coming together for an event. By the end, united in communal prayer and the sharing of food, thought and life with one another, we were newly united in a “common unity of community”–and our mission to reconstruct the social order.

Renée Roden was one of the organizers of the Peter Maurin Conference. She is from Minnesota and met the Catholic Worker movement in New York City. She now lives at the St. Martin de Porres Catholic Worker in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.