Jan.-Mar. 2020 Publication of Casa Juan Diego House of Hospitality

Dorothy Day, Virgil Michel, and Louis Marie Chavet

The Mystical Body: Theology of Unity

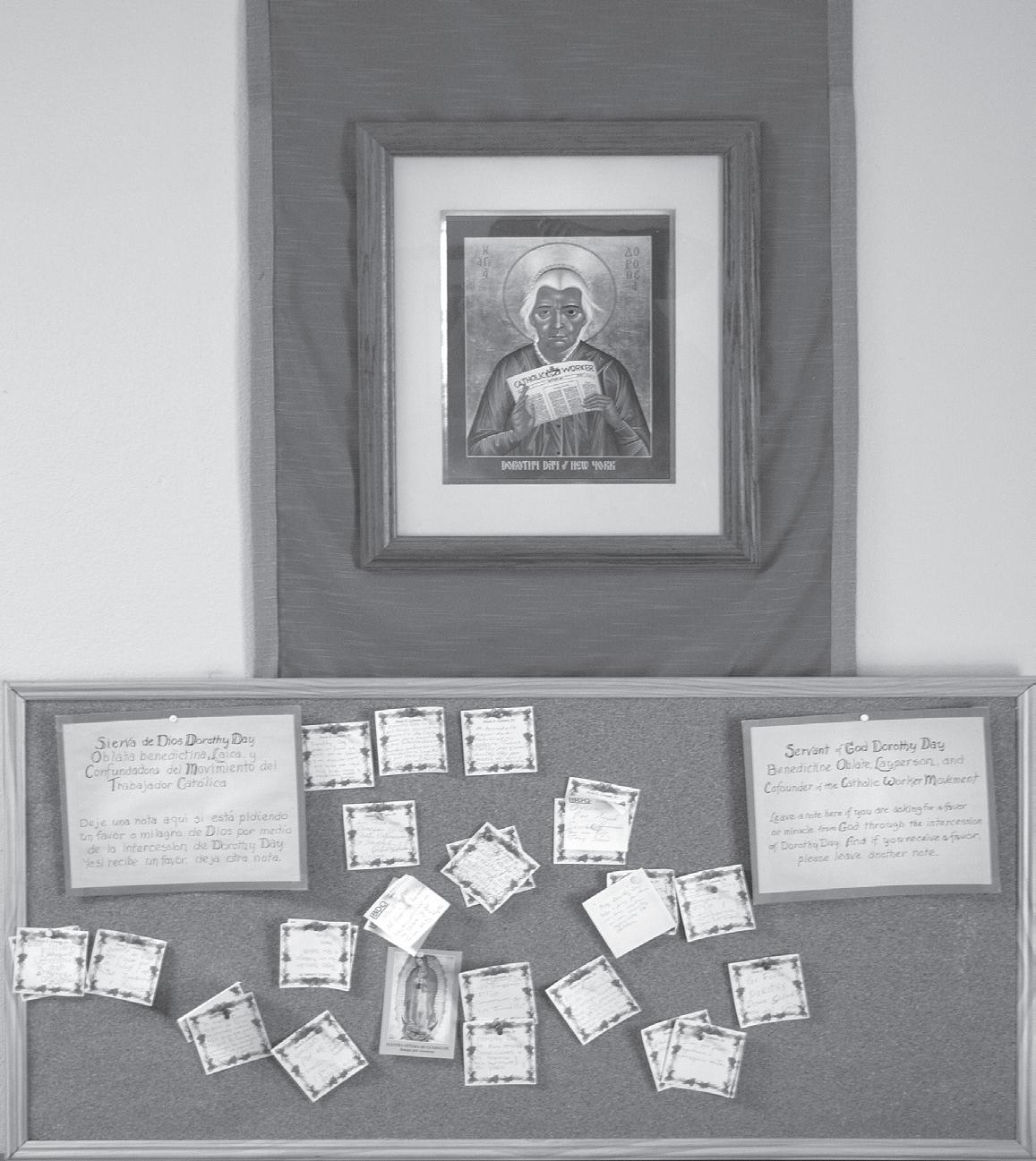

by Louise ZwickIt may come as a surprise to some that Dorothy Day’s canonization cause lists her as a Benedictine Oblate as well as co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement.

Dorothy was indeed a Benedictine Oblate, at St. Procopius Abbey in Lisle, Illinois.

Not so many realize how deeply Benedictine spirituality and practices

and rich.

were to the foundation of the movement. St. Benedict’s Rule included the central maxim that “The guest is Christ.” This tradition and understanding has been a part of the Catholic Worker movement from the beginning. The Catholic Workers quoted Benedict’s teaching that as the monks received travelers and others in hospitality, no distinction was to be made between poor by Evan Bednarz

Please see page 8

Thanksgiving Letter

Life at Casa Juan Diego is like being in front of an eternal conveyor belt with countless people, with never ending needs passing by. People come for food, for hospitality, for advice, for help to survive, for ways to engage the legal system, for ways to help children succeed in school, for a wheel chair or adult diapers when they are wounded, for a blanket to keep warm, for transportation to a relative, or to see a volunteer doctor in our clinic. We receive calls from groups at the Border, from lawyers in nonprofit groups, from ICE, to receive new refugees, from the hospitals of Houston to assist with those who are injured or very ill.

Everyone does their part in supporting Casa Juan Diego. People from all over the Houston area and the United States responded again this year to our Christmas letter with funds to sustain our Works of Mercy, with adult diapers and underpads for the sick and injured, with back packs, sweatshirts, new clothing and toys, underwear and toiletries for immigrants and refugees, not to mention the food that was donated for the hungry.

“Sometimes,” Dorothy Day wrote, “I think the purpose of the Catholic Worker is to show the providence of God, how God loves us. We talk about what we are doing because we constantly wonder at the miracle of our continuance. This work came about because we started writing about the love we should have for each other in order to show our love of God. It is the only way we can know we love God.”

Peter Maurin, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement believed that the practice of the Works of Mercy involved more than simply receiving the Lord in the poor, binding up wounds and washing feet, although these were an incredible work and witness of the Gospel. Peter understood from the lives of the saints that this practice could be revolutionary, that the witness and methods of living the Gospel could change the whole social situation.

We are most grateful to the many generous people who support Casa Juan Diego and the Houston Catholic Worker newspaper, but even more importantly we are grateful to the many people who claim “our” work as their own—those who speak very beautifully about “their” efforts at “their” Casa Juan Diego. They have realized that the revolution of the heart, that living out the Gospel is the way to change the social order.

Thank you all for sharing in the Epiphany of the Lord through the Works of Mercy.

Louise and all at Casa Juan Diego

Solidarity and the Unity of Suffering

Evan is a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego. He came to us from a Trappist monastery.

Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day were friends of Virgil Casa Juan

Return Service Requested

Growing up, it was a tradition for my family to travel into downtown Chicago to see a stage rendition of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Though I knew the story well, it never failed to excite my imagination, perhaps understanding even as a kid the good and evil that battled inside of me, just like

Scrooge. One year, as my family and I stepped out of the warm theater lobby into the chill of a November night, we saw a group of bystanders circled around something. Making our way over, people were standing concernedly over a man sprawled out on the sidewalk. At first, I was horrified, thinking he was dead, but I saw him still breathing, and my mom quietly explained that he just had too much to drink. Someone had already called an ambulance, and

with nothing else to be done, my parents ushered my brother, sister and I to the car. Two decades later I still remember the politeness with which we sidestepped the homeless man and the sense of dread disrupting the festive warmth of Scrooge’s change of heart. When I idle outside Houston’s Greyhound station and stare at the poverty camped out on the sidewalks there, the feeling revisits. Whose problem is this – the city, the Please see page 7

by Margaret (Meg) Spesia Meg is a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego. She graduated last year from the University of Notre Dame.

“The only answer in this life, to the loneliness we are all bound to feel, is community.”

- Dorothy Day, The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day, p. 184

Passing through the front door to Casa Juan Diego’s bustling entrada this past August, I was eager to begin life as a Catholic Worker and yet filled with uncertainty, wondering what exactly I had to offer. With only my suitcase, a love for Dorothy Day, and a tentative trust in the intercession of St. Juan Diego as a teacher in the art of “unqualified” selfgift, I felt unsure of what my role might be here. However, days here are full (and full and full), with a coexistence of more blessing and heartbreak than I’ve ever before witnessed and it wouldn’t take long for the house to absorb me into its rhythm. Soon I was welcoming guests, volunteers, and donors through that same front door with a frequency that was, at times, breathtaking. When a newcomer first arrives, whether they’ve come to live, work, or donate, I recognize the question I had on my face on that first day: Is this a

The Joy Is Fuller With You In It

place for me? Am I welcomed? Am I needed?

Within my first few weeks as a Catholic Worker, I channeled my childhood passion for organizing family talent shows and began to “advertise” an upcoming Noche de Talentos, asking everyone in the women’s house to participate. The night of the show, the sign-up sheet was full, the air was buzzing with excitement, and the women and children of the house settled into their seats to enjoy the performances. However, it quickly became apparent that as eager as we all were to watch, everyone was afraid to perform. After the first few

Encounter with Silence Retreat

“Encounter with Silence” is a six-day retreat, developed by Onesimus Lacouture, S.J., and formerly given by Father John Hugo. Perhaps the most famous lover of the retreat is the Servant of God, Dorothy Day. She made the retreat more than 20 times and wrote of it often. Day said it was “like hearing the Gospel for the first time.” It draws its power from uncompromising reflection upon Scripture, in four one-hour conferences daily.

The Lacouture/Hugo retreat will be given at the following times and places this year:

Sunday, June 14 through Sunday, June 21, 2020

Retreat Master: Father JohnMary Tompkins, O.S.B. Martina Spirtual Renewal Retreat Center 5244 Clarwin Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15229

412-931-9766

Contact: Sister Donna, S.H.S.

Friday, July 17 through Friday, July 24, 2020

Retreat Master: Father JohnMary Tompkins, O.S.B. Saint Emma Monastery 1001 Harvey Avenue Greensburg, PA 15601

724-834-3060

Contact: Mother Mary Anne O.S.B.

had what can objectively be called “talent”. Others, myself included, just wanted to join in the fun. All received a thundering round of applause. With each burst of cheering, one of the great lessons of Casa Juan Diego resounded: the joy is fuller with you in it.

people on the sign-up sheet backed out, two young girls bravely came to the makeshift stage to dance. Yet, when the music began they stood stock-still, too paralyzed in front of us to move. No matter, we gave them a hearty round of applause and turned to the next participant.

Martha (name changed) was a first-grade girl who had signed up to jump rope. One of the volunteers had learned of Martha’s plan and purchased a new jump rope in preparation for the show. As she silently came before the gathered chairs, she smiled nervously and tried out her first jump. She tripped over the rope, but was nonetheless met with a burst of applause. Surprised at the overwhelmingly enthusiastic response, her shy smile grew and she picked up steam, jumping faster and faster as her small audience cheered and shouted in support. Now beaming, she stopped to catch her breath and we gave her a final round of applause. To our surprise, Martha wasn’t finished. She repeated the entire act with the same gusto. The audience went wild, with the cheers echoing off our dining room walls.

From this point on the show took on a new life. Children and adults alike jumped up to share a wide range of talents, from singing and dancing to reading from Scripture. Some people truly

This central message of the Catholic Worker has revealed itself to me time and again in my few months in the house. When someone arrives at the door with nowhere else to go and in need of shelter, the joy grows fuller. When a regular volunteer arrives on their regular day and engages in the same ordinary tasks as the week before, the joy grows fuller. When a donation is brought to the door and a new person takes a copy of the newspaper, the joy grows fuller. I can say this with certainty, not because I’m naive to the heavy burdens that a new guest might bring or the volume of work that the house requires, but because I’ve witnessed it to be true. Each person that joins into the chorus that Casa Juan Diego has been singing for the last four decades adds to the rousing melody.

As Christians and as members of the Catholic

Worker movement, we aren’t called to simply sit and hope that someone else (perhaps those more qualified) will jump up and exhibit their talents. We are called to participate. Perhaps not because we have a tangible gift or service that no one else can provide, but simply because we are needed exactly as we are. It’s an invitation that’s extended in countless ways: through the Eucharist, through our neighbor, through this newspaper. We have all been invited to not just watch, but to get on our feet and join in. The answer to my uncertainty when all I had was my suitcase, a love for Dorothy Day, and a friendship with Juan Diego was yes, this is a place for you. The answer to those questioning faces of the newcomers is a resounding yes: you are welcome. The answer to a timid jump-roper and those that followed her is yes, you are needed. May we all have the courage to get on our feet and join in the song.

Ways That Our Readers

Might Join In the Joy of Casa Juan Diego

1. Come one morning or afternoon each week and do whatever needs to be done, Please see page 4

Transcendence Underpins the Work of Casa Juan Diego

by Brother Francis, O. Cist.Brother Francis (Christopher Gruber) is currently working on his doctorate in philosophy in Rome.

It is with a sense of wonder that I recall my time at Casa Juan Diego in the summer of 2012. I believe that this feeling of awe can be attributed to one of its most unique and defining aspects: the undeniable fact that more takes place there in one day than anyone will ever be able to fully comprehend. This elusive character of the work is not attributable alone to the sheer volume of people helped and/or services performed. Even on a purely sociological level, one would be hard-pressed to determine how far the reach of the effects born from efforts at CJD actually go. Still, the incomprehensibility I invoke is not reducible to the level of quantification.

The inexhaustible quality of the work places it on a level beyond our ken. CJD is, more properly speaking, an event that is ever-unfolding. The scope of the influence that issues forth from CJD can in no way be wholly traceable back to the amount of labor that is carried out within. Being able to unleash an effect greater than what it is able to produce of its own accord bestows upon it a peculiarly transcendent quality.

Delayed Onset Realization

Shortly after leaving CJD and beginning a master’s program in Chicago, I experienced what may be referred to as a delayed onset realization of the magnitude of the project of which I had just recently been a part. Making an arduous trek home from the university through the urban streets of downtown Chicago, I would pass people on the streets who were without a home, with only a few blankets. And I began to be disturbed by the indifference of the world, including my own, which due to perfectly good reasons excuses itself from the responsibility of these non-entities of society, who are nevertheless inexorably human, who are condemned to endure a northern winter without shelter. I asked

myself: does not anyone out there care about the humans who are looked upon as the burdensome refuse of firstworld society? Does anyone take heed of the demanding words of Christ in regard to the neighbor, the human other, who is in want? It was at moments such as those that I began to realize the utter gravity of the project of which I had been a part, of the work that goes on day and night, without cease, in Houston at Casa Juan Diego. I began to think of the universal Church as a whole and began to realize that no matter how important the activity of other organs of the Church may be, that the close and direct service of the poor inspired by the faith is probably the most faithful adherence and compelling witness to orthodoxy there is. As I wrote in a term paper I did on the Zwicks’ immense project, in order to demonstrate that the measure of orthodoxy is most clearly manifested by conformity to the Gospel: “There is a simple test we would like to propose to evaluate how close a philosophy or way of life is to the Gospel. As a map in one’s hands, one should look at the Gospels and then up at the world again and see how well the actuality before them conforms to the teachings laid out in the writings. If people are feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger and clothing the naked (not to mention all in a spirit of vibrant faith), you can be sure you have found the right place.” Contrary to the prevailing opinion in some circles, orthodoxy is not something that primarily concerns the greatest possible risk reduction of any potential margin of error of theoretical or theological disquisition as much as it lies at the heart of the orthopraxis of ever-vigilantly taking heed not only to hear but also to act on the Word (James 1:22). In the intimacy of my own fidelity to the work of CJD, (rather than the oftinvoked climactic eschatological masterpiece of Matthew 25), I am most inclined to call to mind the astounding words of Luke 14: “When you hold a lunch or a

dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your relatives or your wealthy neighbors, in case they may invite you back and you have repayment. Rather, when you hold a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind; blessed indeed will you be because of their inability to repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous”

tribulation in their homeland—I made some relationships that I will never forget.

The first indelible image took place after the Wednesday evening Mass at the men’s house. As I was standing outside admiring the twilight sky in the wake of that spirit of transcendence and peace that descends after another weekly Mass at CJD,

Angel Valdez

(NABRE). I remind myself that I have never read or heard anything like this anywhere else in my life. One need not despair that the concrete charity spelled out by the Gospels remains a beautiful idea that is never put into action—or perhaps even more dangerous, transformed into an innocuous metaphor that cancels its original, literal, and straightforward meaning— but can find hope in its actual unfolding at places like CJD.

Two Recollections

My memories of CJD can only be retrieved through the lens of seven years of hindsight and will therefore not convey impeccable objective reporting as much as the impact of the personal impression they made on me that has withstood the test of time. Among the community primarily served at CJD— immigrants fleeing from

proclaiming the solemn words so dear to us in the faith that announce the real presence of the Lord, in his coming through the simplest of species of bread and wine, did the tradition of my faith not also tell me that this large man (by whose interruption I was slightly miffed) too was a harbinger of the real presence of the One who Was, who Is, and is to Come? Is it not the selfsame Lord who had just come to us in the bright vibrancy of the Host who was now also coming to me through the guise of this misshapen and cumbersome stranger?

a large, middle-aged, bowlegged American man – not an immigrant - lurched toward the house. He told me that he was in much need and asked if he might be able to find a place to sleep.

Knowing that he would not be able to be find shelter there that night, I told the man to wait a moment while I would go and talk to the manin-charge, Don Marcos. I felt somewhat bothered by the untimely intrusion of this large man asking for help at such an hour at a place that, out of the others that he could have gone to, was not able to take him. Yet, at least in the midst of my fallen and alltoo-human annoyance, I am grateful to recall that I was nevertheless haunted by a question that was only now becoming all too uncomfortably immanent. With respect to the host that the priest had raised during the consecration of the Mass,

I succeeded to bring the large man to Mark. As Mark was already advanced in years by this time, I wanted to stand by to do all that I could to assist and arbitrate one of the many requests that would accost Mark all throughout the day. The man explained his situation of needing a place to stay the night to Mark but his refusal to go to the shelters. Though Mark could not offer him a place to sleep, he proceeded to perform a deed that was one of the most important lessons I learned of what CJD is all about in its actual praxis on the groundlevel and not only in its mission statement in its literature. He pulled money from his pocket and freely gave it to the man, telling him kindly that this should help him find a hotel room to stay for the night. The man was very pleased and thanked Mark and, uplifted, now in a bit of a jocular mood, recounted to him how he was happy not to be going to the shelters, as people steal his stuff there.

The second story involves a job very familiar to any Catholic Worker at CJD, and that is driving the guests to doctor’s appointments, though here, with a slight twist. Louise explained to me that I would not be taking a guest per se, staying at the house, to a doctor’s appointment but rather a man from Iraq, suffering from some mental problems, who lived at another home in town for refugees, nevertheless of whom CJD takes care. The Please see page 6

Peacemaking Is Hard

New Film Pays Tribute to Conscientious Objector

By Tom, Eggleston, M.Div.Tom Eggleston is a pastoral care minister at a large Catholic parish in Holland, Michigan. He is also a volunteer staff member of the Catholic Peace Fellowship

Fr. Daniel Berrigan writes in a poem “peacemaking is hard / hard almost as war.”

In the weeks since I viewed Terrence Malick’s latest movie A Hidden Life, I can’t seem to shake the words of the prophetic poet Berrigan. The film depicts the metanoia of the Catholic conscientious objector and martyr, now beatified, Franz Jägerstätter. A Hidden Life maintains the course of Malick’s achingly beautiful visuals alongside the story of the toil of rural life and, of course, the hapless violence of the Nazi regime.

At its essence A Hidden Life is a biographical movie depicting to latter years of blessed Franz. For people who hold a devotion to blessed Franz Jägerstätter the plot of the film unfolds as his life did—a journey from farmer to conscientious objector to martyr.

Jägerstätter lived in Sankt Radegund in the mountains of Austria. As depicted in the film, he was an unassuming man of the land, a dedicated husband and father. His life drastically changed, however, when the forces of Nazism arrived in the secluded hamlet, leading to his conscription into the armed forces. In the movie, his refusal on religious grounds to take an oath of allegiance to Hitler, results in his arrest, torture, and killing. It should be noted too, that on top of his abhorrence to the oath, the historical blessed Franz Jägerstätter also did not want to cooperate in any way with the Nazi war effort and worried about its attempts to dismantle the Church as well.

While the plot may be laid bare as above in a matter of fact manner, the work of Malick adds drama and heft to what is an interior journey of a farmer come martyr. A great deal of credit, as in all matters to do with blessed Franz, is due Gordon Zahn who was once an advisor for the Catholic Peace Fellowship. It is because of

the dogged scholarship and faithful work of Zahn that we even know of blessed Franz Jägerstätter whose life story could easily have been lost in the sands and fog of history and war. Zahn’s book on Jägerstätter, In Solitary Witness, along with the published correspondence between the incarcerated husband and his wife in Sankt Redegund, provide the backdrop to the words given life and beauty through the moving images of Malick.

A Hidden Life nestles itself within the pantheon of Terrence Malick’s best work, and his best are indeed master works. In the movie he exhibits thematic and technical elements that can be traced through his career. A Hidden Life displays the agrarian setting in all its beauty like Days of Heaven, the biographical thrust of The New World, and the awe of nature as in Tree of Life. The film contains the revulsion of violence and discomfort with war communicated in Badlands and The Thin Red Line. This newest film is the director at his best.

Malick’s oft employed

technique of voiceover juxtaposed with natural beauty is exhibited as a

tremendous achievement. If the director experimented with that technique in Song to Song and Knight of Cups, even with limited success, he uses voiceover in A Hidden Life as to illumine the interior life of a martyr in a style difficult to imagine in the work of another director. The voiceovers of the varied characters become an implied dialogue between them, and the effect feels like prayer or memory, in which images and words coalesce in illuminating ways. Again and again we witness Jägerstätter’s interior deliberation between denying his faith to swear allegiance to Hitler so as to be able to live a hidden life with his family or execution in anonymity. Knowing how Franz’s life ends makes the drama no less gut wrenching. The visual experience displays in heaping doses the beauty of the natural world with the rigor of rural farm life. So often the Christian committed to nonviolence experiences the dull critique that peacemaking is a hapless delusion for the dreamy idealist. The reality, however, is what Fr. Berrigan writes, that peace is tremendously hard work. That insight is,

perhaps, the most illuminating aspect of the film, even if considered only tacitly. Blessed Franz does not resist war because it is the easy path; he does not refuse to participate in war because he desires a life of idyll. Rather the peaceful life he longs for is one of toil and parenting, mud and animal husbandry, plowing and potato digging. The accusations levied by others that he refuses military service out of cowardice or even laziness do not pan out in light of Sankt Radegund, nor in light of the choices offered to conscientious objectors today.

In A Hidden Life the easy life is presented as the path in which one cedes one’s conscience secretly. The hard life is composed of making brave choices which correspond to the Christian’s conscience. Fr. Berrigan, the prophetic poet, laments in No Bars to Manhood that there is no peace because there are no peacemakers. In A Hidden Life we rend our hearts along with Berrigan, for to be a peacemaker in modernity is often also to be a martyr.

The Joy Is Fuller With Your Help

Continued from page 3

such as: Cook, wash dishes, mop floors, address thank you notes, organize a storage room, drive a guest to hospital, clinic, or lawyer, help distribute food to the poor.

2. Donate maseca, cooking oil in a size appropriate for a family of the sick and injured, wheel chairs, underwear for men or women, adult diapers, underpads, wipes, towels, twin size sheets, toilet tissue, deodorant, shampoo, toothpaste.

3. Become a full-time Catholic Worker (Spanish, French or Portuguese speaking ability necessary)

4. Assist in our medical clinic (Spanish required)

4. Bring your youth group for a Saturday morning project.

5. Tutor children at 3:30 p.m. after school, Monday through Thursday.

6. Send your friends gift subscriptions to our newspaper.

7. Donate money: Casa Juan Diego, P. O. Box 70113, Houston, TX 77270.

8. Join us for Mass in Spanish on a Wednesday evening at 4811 Lillian, Houston 77007.

9. Pray for us and for our guests.

10. Come and help with our food distribution Tuesday mornings, 6:00. to 9:00 a.m.

Litany Of Deliverance

by Fr. Rafael Dávila, M.M. Litany based on the talk of Pope Francis to the International Association of Penal Law, held in Rome Nov. 13-16, under the scope of “Criminal Justice and Corporate Business.”

· From the culture of waste and hatred, Deliver us, O Lord

· From the reappearance of Nazism, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From “market idolatry” and the principle of profit maximization, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From incentive to violence or disproportional use of force, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From punitive irrationality in mass imprisonment, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From crowding and torture in prison facilities, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From abuses by security forces, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From criminalization of social protest, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From the abuse of preventive detention, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From repudiation of most

elementary penal and procedural guarantees, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From scarce attention or absence of attention to crimes of the most powerful, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From macro-delinquency of corporations for crimes against humanity, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From crimes that lead to hunger, poverty, forced migration, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From death due to preventable diseases, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From environmental disasters, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From murder of indigenous peoples, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From organized crime of global financial capital against people and the environment, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From over-indebtedness of states, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From the plundering of the planet’s natural resources, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From sins of ecocide against the environment, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From massive

contamination of the air, of the land and water resources, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From large scale destruction of flora and fauna, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From actions producing an ecological disaster or destroying an ecosystem, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From the destruction of ecosystems of specific territory as a crime against peace, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From the abuse of “preventive prison” with people jailed without criminal conviction, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From involuntary incentive to violence, justifying crimes of security forces, Deliver us, O Lord.

· From “punitive demagogy” often racist or aimed at marginalized groups, Deliver us, O Lord.

O God of all creation and of all humanity, humbly we pray that you deliver us from these evils and that you fill us with wisdom and courage to stand up against these evils, and move us to works of spiritual and corporate works of mercy.

We ask this through Jesus Christ the Lord.

Letters from Our Readers

Dear Casa Juan Diego, Thank you for all that you do to welcome our immigrant sisters and brothers and provide for their basic needs. Your commitment to living out the Gospel values continues to inspire me from afar.

Emily Norton, Washington, D.C.

To Whom It May Concern: My mother, “Jeanne” passed away this year. She was a devout Catholic who followed the teachings of loving, accepting, and helping ALL God’s children.

In 1998, as a freshman in college, I went on a Spring Break Service Trip to your organization, driving 1,200 miles from the College of St. Benedict in St. Cloud, Minnesota. It was one of the most powerful and impactful experiences I had had in my life up until that point, and I formed deep connections with some of the children I met on that trip who were receiving shelter with you. Their stories touched and shook me to my core, and when I returned home, I gushed about the experience and the great work you were doing to my mom. I know the political climate for undocumented immigrants was a little touchy even back then, so I can’t even imagine the challenges you must be facing in today’s political climate.

My mom was so impressed by the work you did and grateful to you giving me such a powerful service experience that she mentioned you specifically in her will. Please accept this donation in her honor.

Donna Wasielewski, M. S Austin, TX

Dear Louise and All the Workers at Casa Juan Diego, My nephew had a terrible accident this fall, resulting in a badly fractured skull and a very unfavorable prognosis. In my prayers I asked Mark for his prayers and advocacy Two other holy men as well. My nephew, Chad had a recovery that was nothing short of miraculous.

David Bradley, Houston

Dear Louise:

Years ago, we, my sister Charlene Katra and my father Anthony Iannucci, visited with you and Mark and talked with him about his days in Warren, Ohio. We were given a tour of your property and discussed the work you were doing in the community.

Many years before that, Mark taught my 8th grade religion class the “Our Father,” phrase by phrase. I think of Mark whenever I say it. He truly lived his faith! And we are so pleased that you and your many wonderful volunteers are able to carry on the mission of Casa Juan Diego.

Tom and Eileen Landry, Highland, Michigan

Dear Friends at the Houston CW,

Many thanks be to you for your witness to the Gospel and your humble loving service to the poor and the outcast. May you all be sustained in your work and united in love by the prayers and gratitude of our family and all who know of your efforts.

Bill Ford and Diana Lane, Ossining, New York

Spiritual Foundation Informs the Work of Casa Juan Diego

man was waiting outside for me as I drove up and quickly got into my vehicle. His disposition was gentle yet troubled, meek not so much as a virtue as much as being void of confidence, it seemed. As we were driving, I wanted to make conversation with him and, in my attempt to be culturally sensitive yet still desiring to engage the religious nature of our work, asked him if he was active in his own faith to which he answered affirmatively. When I followed up and asked if he enjoyed going to the mosque and reading the Koran, he corrected me promptly and told me that he did enjoy practicing his faith but that he was Christian and often read the Bible. A bit surprised, I asked him if he was raised Christian, and he explained to me that he was not but had converted after fleeing the war in Iraq and finding refuge in the States. I dropped him off at his appointment and ventured to run another errand in the hour-long window I had before picking him up. I showed up a bit late and there he was standing outside the doctors’ office, as meek yet forlorn as could be. He got in the car, and I drove him home. What could have been (and in reality was) just another routine doctors’ appointment run somehow became one of the most grace-filled moments of my time as a CW. Just before getting out of the car, the man turned to me to shake my hand and to thank me for driving him to his appointment. The look in his eyes testified to a genuine, visible, and heartfelt thanks to have received this ride from CJD. I watched the meek man, crouching forward a bit uncertainly, disappear into the buzzing hubbub of the meager lodgings in which he lived. Just one of the many unknown and forgotten casualties of a human life displaced from wars fought for the interests of powerful nations, disappearing into the sea of the anonymous underworld of refugees scattered throughout the

earth. Though on a purely objective level it could seem rather depressing, the Holy Spirit, which I believe exuded from that man’s heartfelt thanksgiving, helped me understand better that the world through the eyes of the Spirit is not the same reality of that of the world of the mass-media, with its own economic interests, scrolling stock-market tickers, interested hustle and bustle, and ultimate

nevertheless always detectable on his face the well-springs of a nascent smile. The hard lines ingrained upon his somewhat stern and undeniably dignified face were ever ready to loosen into the gentle welcome of a warm smile: a visage that bespoke a love that was compassionate yet demanding, much like that of Christ’s love. As Mark began to show me the ropes, I felt a kinship begin to

indifference and blindness to the irrevocably singular, to the human. There always exists somehow the possibility of hope, as in the life of this displaced man, who recounted to me with a certain sense of pride his faith and, though broken, still knew how to unfurl a sense of gratitude, which gave testimony to a profound heart underneath, to a complete stranger.

To me, such stories and are evidence of the truth that a force greater than human efforts is diligently at work at CJD.

Memories of Mark I cannot conclude my reflections on CJD without spending some time on the man who stood behind it all: Mark Zwick. When I first met Mark on my first day there, just minutes after arriving, what was first clear to me was the utter kindness and good-naturedness that underlay the somewhat stoic, simple appearance (a worn long-sleeved, button-down shirt, a drab pair of pants, and a baseball cap) and laconic demeanor. Even if he often had to wear a very serious expression, there was

though I sensed a great sense of peace emanating from this man in adoration, at the same time I could also somehow sense the heaviness of the burden. As Mark and Louise have often written, the work at CJD is undeniably good work, but it is a difficult work that ultimately cannot be done without faith. They do as much as they can but ultimately, like the offering up of daily bread, must put the work and the fruit it is to bear into the hands of the One who once commanded and now guides it.

Holy Communion With the Other

blossom with him, also a sense of allegiance, and even discipleship. Sometimes he would joke that the fact he could remember my name must mean a good thing, that I was doing good work.

Sometimes during the day at the men’s house, Mark would drop in unexpectedly to check on us and see how everything was going. The other men and I would enjoy a nice exchange with him, share a few laughs, and then continue on with whatever we were doing. I remember that, on more than on one occasion, long after I thought that he had left, I would open the door to the tiny chapel at the men’s house, only to find him seated there, serene as could be, head tilted slightly forward, with that facial expression of a somewhat furrowed, even wary brow, showing a seriousness and extreme vigilance, as well as the imprints of all he had been through, that nevertheless remained undergirded by the everpresent dawning of a smile. Looking back, reflecting on the moment to a fellow CW at the time, I realize that even

As my time at CJD came to a close, I remember distinctly that at my last Friday evening dinner at the Zwicks with the other volunteers, that as I was sitting on the couch taking part in the general conversation, Mark caught me unawares as he approached me on my right side to pat my arm to get my attention. I remember responding with an affirmative embracing of his hand on my arm in affirmation and eagerly, affectionately looking into his eyes, hopefully effusing the same sort of presence the man from Iraq had shown to me, as if to tell him, “I know our time left together here is short—I have come to love and admire you deeply for all that you do, for all that you stand for, for all that you are—I will help you in whatever way you need.” As I write this, it somewhat becomes clear to me: the person I felt that I wanted to be of assistance to the most was Mark. Even though one

If there is a mantra of sorts that I can think of to encapsulate my time at Casa Juan Diego, I remember that it was indeed “holy communion with the other.”

comes to CJD in order to serve the poor, I did come to realize at a certain point that I could not have been able to find the energy to do all that is demanded of the work without the presence of the community of all the other Catholic Workers: their love, encouragement, and warmth not only to the materially poor but also to the spiritually poor, like myself: to all who come to join in their work.

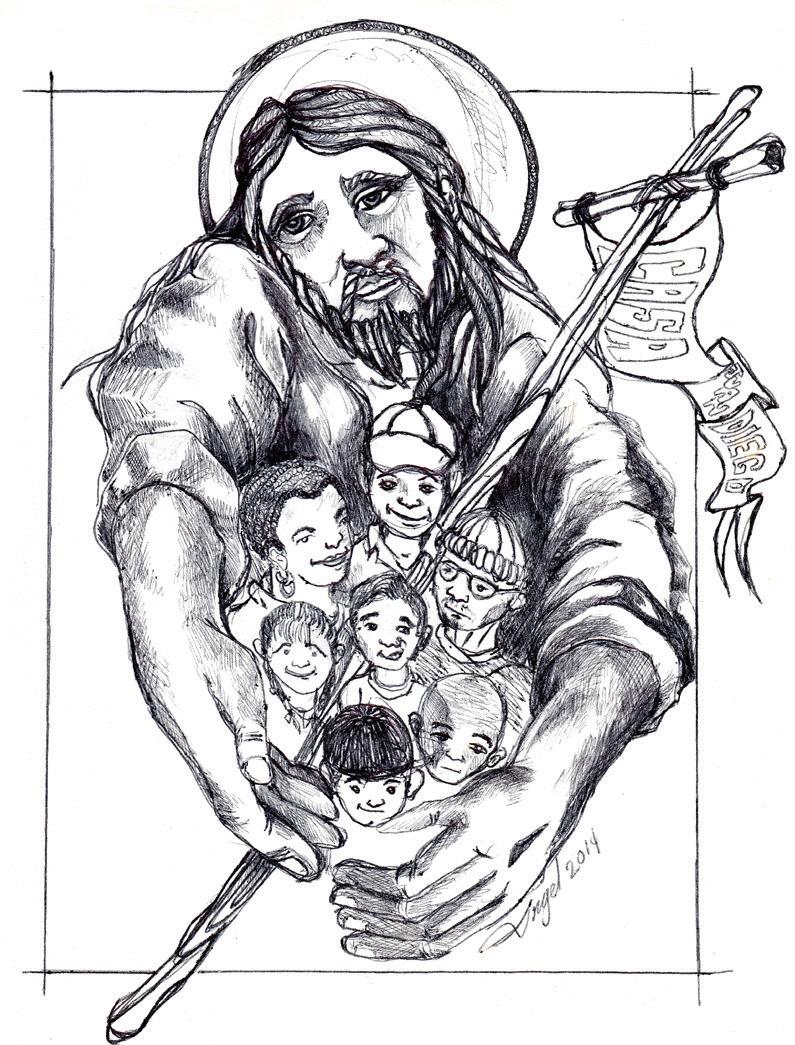

A beautiful and strange dynamic begins to open up, that seems to me to carry on the original intention of the founders of the Catholic Worker Movement, Dorothy and Peter. We come together out of our own need, even inadequacy, in order to be together, to help one another, and thereby to grow in genuine human relationship and dignity. If there is a mantra of sorts that I can think of to encapsulate my time at CJD, I remember that it was indeed “holy communion with the other.” When we Catholics receive holy communion, of course in its most straightforward sense, it is first and foremost union with our Lord. But it is just as undeniable that this same Lord wanted to engrain upon us, that the extent of our communion with Him only goes as far as our ability to open up those portals (cf. Ps. 24:7) of our inner-life to the communion, which must also be something holy and sacred, with the other. An aura, it seemed, began to follow me that summer. A rediscovery of life, of the depths of the faith, and the viscera (σπλάγχνα) of its meaning begins to emerge when day after day you place yourself in an environment where good intentions cannot remain thus but must be put into severe, and at times “harsh and dreadful”, action. Everywhere I went, with everyone I met, I tried to actualize (and more importantly, allow myself to be actualized by) that notion of holy communion with the other. I was reminded that in every person I came across that communion with our divine Lord who awaits us and beckons to us from heaven can only find its telos and the fulfillment of the secret of its meaning when it becomes incarnate and made reality with the human and imperfect neighbor we find here with us on earth.

Continued from page 1

government, the people themselves, me? In Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, the spiritual elder Father Zosima says, “Each of us is undoubtedly guilty on behalf of all and for all on earth.” Even as a tenyear old it was as if I had intuited this truth, and even as a thirty-year old I am still avoiding it. In that Chicago night was not simply a homeless man but a visible sign of the world’s hidden cruelty in which I would have to confront my own role.

Karl Rahner described Christian existence as one of radical perplexity, saying, “All our riddles, our ignorance, our disappointments are but forerunners and first installments of the perplexity that consists in losing ourselves entirely through love in the mystery that is God.” Living with eyes of faith often evokes perplexity: where is God in the swirling litter of parking lots, Black Friday or the sociopolitical forces forcing men and women and children to seek shelter at places like Casa Juan Diego? To what extent has my upbringing of comfort and convenience been gained at the expense of the men with whom I am now living?

Talking with a young Honduran recently, I was dumbfounded to learn that he earns more in one hour here than in an entire day back home – how many pieces of my clothing have been stitched in Honduran maquiladoras?

It makes sense that if life unfolds solely on the material plane, one should strategically keep one’s eyes closed so as to avoid the soul-muting melancholy that arises when one confronts the brute fact of the world’s suffering. Pleasure depends on the avoidance of pain, ours as well as others. As a sign of contradiction against such bourgeois joy, Christian hope must, in the words of the late J.B. Metz, see with an “open-eyed mysticism”: the perverse unity of suffering must become a shadow-image of the solidarity we share in Christ and his Body, our

Solidarity and the Unity of Suffering

dividedness a precursor to the communion to which all humanity is destined. It seems to me that the Catholic Worker is founded upon not flinching from the world’s misery and yet acting in accord with the light shining through the Gospel. A light that nonetheless points to a cross.

More and more I consider the political aspects of the work done at Casa Juan Diego – not in terms of vocal protest or electoral politics – but what it means to presuppose that every human being, without qualification, is made in the image of God. If we accept this, then homelessness becomes more than a social nuisance or the inevitable offal of market dynamics.

Christianly speaking, it is an indictment, a complicit reenactment of Jesus’s rejection by his own. “The poor,” Jesus said, “you will always have with you.” Did he mean this to say that havenots are inevitable, as some would interpret, or as a summons to generosity beyond an instinctive selfconcern? I did not choose or deserve the privilege that characterized my upbringing,

respective worlds toward where our humanity converges in the image of God.

heard.

just as the young Honduran neither chose nor deserved the poverty and violence that caused him to leave his home; simply put, both are the worlds we were thrown into. That we are sharing the same roof and meals is more than a practical arrangement then: it means a continual challenge to look past our

Though I misplace my keys all the time and my Spanish is lousy, there is at least one lasting insight God has given me: to be-with is revolutionary. It can be easy to associate men at Casa Juan Diego with their immigration status or countries of origin –even the men nickname each other by countries, calling out “Cuba!” or “España!” But I think what Casa Juan Diego does is well-conveyed by the opening of the Vatican II document Gaudium et spes: “The joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the people of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted, are the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of the followers of Christ as well.” To listen to stories of shakedowns by Colombian bandits, vicious Panamanian jungles, and for-profit American detention centers, to meet our guests as people who are desperate to start their lives anew or for work to send money home to their families for whom they are even more desperate to again see, seems to be the real work being done at Casa Juan Diego. It is the upbuilding of a world where everyone has a seat at the table, every story

The consumption and convenience that most of us breathe in as thoughtlessly as air, through the ubiquitous presence of Amazon, Instagram, Apple, et al, constantly tempt us toward a moral drowsiness that makes us incapable of imagining a world in which it is easier to be good. Perhaps we volunteer while driving a luxury car, incapable of discerning such contradictions. The dread I feel passing by tents pitched beneath overpasses or the intermittent claustrophobia of living in close quarters with thirty or forty other men are moments to recommit myself to the mission envisioned by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day: take less so others can have more; be responsible for the poor of your community; do small things with great love; when the people you are trying to help mock or reject you, rejoice, for your love is being purified of selfish aims! It is the mission and privilege of Casa Juan Diego to give hospitality, at least for the night, to the hidden Christ en camino, welcoming each with rice and beans, soap and underwear, a place to lay one’s head. In other words, the burden and gift of faith.

Refugee Murdered Waiting at the Border

by Dawn McCarty, PhD, LMSWRecently, we received word that the brother of a current guest of Casa Juan Diego, who had been forced to await his day in a U.S. Court in one of the refugee camps just across the border in Mexico, had been murdered. We don’t know the details yet, but a fellow migrant, also waiting in Mexico while the U.S. government delays and obstructs their asylum application, sent a photo of the brother’s body, I guess as a sort of formal proof-ofdeath to be shown to anyone that would witness.

The surviving brother was brought over to the office to give us the terrible news. His brother, after following every rule of international and U.S.

law for applying for asylum, after having successfully shown a credible fear of persecution and been granted a date for his hearing in immigration court, had been forcibly sent to what is now likely the most dangerous place on earth for migrants: the Mexican side of the U.S./Mexican border.

The administration likes to call this its “Remain in Mexico” policy, but the official name is the “Migrant Protection Protocol.” In Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, “War is Peace,” “Freedom is Slavery”, and” Ignorance is Strength.” In 2019 America, “Migrant Protection” is sending people who are fleeing for their lives to cities under the control of criminal gangs whose source

of income is kidnapping asylum applicants and extorting their families back home.

Jocelyn Aquino

Continued from page 1 Michel and the other Benedictine monks at St. John’s Abbey. The monks gave talks at the Catholic Worker in New York. (See Mark and Louise Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement: Intellectual and Spiritual Origins, Paulist Press.)

Dorothy and Peter participated in the liturgical movement of the earlier twentieth century, sharing Virgil Michel’s vision that brought together worship and social responsibility and action, emphasizing the connection between the Eucharist, the Mystical Body of Christ, and the unity of the Church. At the Catholic Worker and in the broader liturgical movement in the United States under the leadership of Virgil Michel, the liturgy was understood and celebrated as formative of the daily life of Christians in the Mystical Body.

What had been an exciting theology, in the United States especially advocated by Virgil Michel and Dorothy Day and so many others involved in the early liturgical movement, has faded to some extent in recent decades in favor of a model of the Church as the People of God.

Unfortunately, Virgil Michel died prematurely, before the Second Vatican Council, where his insights might have enriched the Council documents.

In a recent book, One in Christ: Virgil Michel, Louis-Marie Chauvet, and Mystical Body Theology (Liturgical Press), Timothy Gabrielli presents the arresting possibility of a

Have We Forgotten That We Are One?

wrote about the Mystical Body of Christ: the Roman, the German, and the French streams. Gabrielli descrobes the French stream as the best of Mystical Body thought, avoiding the pitfalls of the others. He places both Chauvet, a French theologian, and Virgil Michel in the French stream, which followed the work of Belgian Benedictine Lambert Beauduin.

“The thing to do is to enter upon another plane, to find that fourth dimension which represents the kingdom of the spirit.” – Henri de Lubac

contemporary renewal of the theology of the Mystical Body, making connections between the work of Virgil Michel and contemporary French theologian LouisMarie Chauvet.

Gabrielli identifies three streams in the historical thought of theologians who

Chauvet, like Beauduin and Michel and others in the French stream, emphasizes the connection between the liturgy, the sacraments, and the daily life of the Christian. According to Gabrielli, Chauvet makes a clear link between the liturgical and the ethical, the liturgy and its social implications.

Gabrielli’s book features not only Virgil Michel and Louis Marie Chauvet, but Henri de Lubac (a significant voice in the French stream), showing how Chauvet

in his book.

This book suggests to us that Dorothy, along with theologians in a renewed understanding of the theology of the Mystical Body of Christ, can help us to overcome divisions in the Church, polarizations which often simply mirror the divisions in secular, political society. Rather than despairing over the excesses of a number of ostensibly Catholic web sites, blogs, or TV channels which attack other Catholics and even the Pope, one can find hope and joy in Christ’s presence among in the liturgy and in the impulse that participation in the Mass gives us to follow the Nazarene in our daily lives. One can see in the unity of the Mystical Body, in the Scriptures featured in celebration of the liturgy, that secular economic or political theories and practices that hurt the masses of workers, and the poor and immigrants and refugees, are not inspired by the Holy Spirit. Nor is war.

develops the theology of the French stream following de Lubac, but also incorporates insights from the philosophy of phenomenology. Both de Lubac and Chauvet write of the threefold Body of Christ. Chauvet spells out the three bodies, united by the Spirit: “It is significant that the Spirit is the operating agent of the threefold body of Christ: his historical body, born of Mary, overshadowed by the Spirit (Luke 1), and spiritualized into a glorious body, his sacramental body…; and his ecclesial body….”

(Louis Marie Chauvet, Symbol and Sacrament, 455, quoted in Gabrielli, One in Christ)

In suggesting a contemporary revival of Mystical Body theology, Gabrielli brings in the insights of Charles Taylor and other commentators on the realities of contemporary culture, often secular, with the aspects of fragmentation and interconnectedness.

Mystical Body Theology and the Catholic Worker Gabrielli does not neglect Dorothy Day, but rather dedicates several pages to her

Church) taught that all people are members or potential members of the Mystical Body of Christ. She applied this to questions of war and peace, insisting that bombs could not be dropped on members of Christ’s Body. According to Gabrielli, Chauvet, also, has arrived at this same conclusion on membership and potential membership in the Mystical Body, but through phenomenological “ways of thinking” (161).

In the first years of the Catholic Worker, Dorothy wrote about how the theology of the Mystical Body can bring unity, rather than division and war. In an article in the Houston Catholic Worker in 1997, long-time Catholic Worker Tom Cornell showed that Dorothy was writing about the Mystical Body as early as 1934 in The Catholic Worker:

One can identify in the liturgy with the self-giving of the Lord and the Paschal Mystery, and try to imitate that in our lives.

Dorothy quoted de Lubac:

“Fr. Henri de Lubac, the great French Jesuit, wrote in his Drama of Atheist Humanism, ‘So long as we

“In October 1934 an unsigned article, ‘The Mystical Body of Christ,’’ written in Dorothy’s style and vocabulary, began with a quote from St. Clement of Rome. “Why do the members of Christ tear one another, why do we rise up against our own body in such madness; have we forgotten that we are all members of one another?” Dorothy goes on to describe

“Why do the members of Christ tear one another, why do we rise up against our own body in such madness; have we forgotten that we are all members of one another?” – St. Clement of Rome

talk and argue and busy ourselves on the plane of this world, evil seems to be stronger. More than that, whether evil distresses us or whether we exalt it, it alone seems real. The thing to do is to enter upon another plane, to find that fourth dimension which represents the kingdom of the spirit. Then freedom is queen, then God triumphs and man with him.’”

(The Catholic Worker April 1954) Dorothy drew out the implications of the theology of the Mystical Body when she wrote, for example, about how St. Thomas Aquinas (not to mention the Fathers of the

war as an illness that weakens the whole body. “All men are our neighbors and Christ told us that we should love our neighbors, whether they be friend or enemy…. If a man hates his neighbor, he is hating Christ.”

What Do We Worship?

Both Dorothy Day and Virgil Michel pointed out the evils of individualism and how it contrasted with the solidarity of the Mystical Body of Christ.

In our book on the Catholic Worker Movement, Mark and I wrote of and quoted Virgil Michel, OSB,: “As if he were writing today, Michel blasted Please see page 9

A Renewal of the Theology of the Mystical Body?

Continued from page 8 the glorification of amassing of wealth and the ever greater accumulation of goods, which had captured the imagination of the American people, a set of values basically hostile to the human spirit: ‘It is no wonder then that the culture of our day is characterized as being the very opposite pole of any genuine Catholic culture. Its general aim is material prosperity through the

amassing of national wealth. Only that is good which furthers this aim, all is bad that hinders it, and ethics has no say in the matter.’” (Virgil Michel, OSB, “Christian Culture,” Orate Fratres 13 (1939) 299.) He believed that active participation in the liturgy, in worship, in the sacraments, might change this attitude.

In a recent article in Commonweal, William Cavanaugh, referencing Max Weber, pointed out that if the human person stops worshipping God, that worship will inevitably be replaced by worship of something else, in other words, idolatry. And in today’s world, that something is, all too often, money and the economic system of extreme capitalism.

Cavanaugh entitled his article “Strange Gods.” It is indeed strange that the God of consuming fire who sent his Son to give His life as a sacrificial gift for all us, could be replaced by the worship of money and gadgets. Perhaps active participation in the liturgy, where we hear from the pulpit and are asked to live the words of Jesus: “You cannot serve both God and Mammon” (Matthew 6:24), may save us from this monstrosity.

Dorothy Day wrote strongly against the sins involved in advertising and consumerism. She famously said, “There have been many sins against the poor which cry out to

high heaven for vengeance. The one listed as one of the seven deadly sins is depriving the laborer of his share. There is another one, that is, instilling in him the paltry desires to satisfy that for which he must sell his liberty and his honor … newspapers, radios, television, and battalions of advertising people (woe to that generation) deliberately stimulate his desires….”

In writing this article we were interested to come across an article in Worship magazine (82, No. 4, July 2008) by Timothy Brunk entitled, “Consumer Culture and the Body: Chauvet’s Perspective.” Brunk outlines in all its detail, the negative, relentless advertising messages which bring the individualistic, consumer culture to our people, quoting many other articles on the topic before coming to Louis Marie Chauvet’s theology as a response to the barrage. His article reminds us that in speaking of the Body, Chauvet is not speaking only of the physical body, but rather the three bodies he outlines in his work on the Sacraments: a body of tradition/history, a body of culture, and a body of the cosmos. A key feature of Chauvet’s thought is that of “gift,” the gift from God and how the gift requires an appropriate response. Brunk undermines the extremes of consumer culture by bringing to bear Chauvet’s theology of gift.

before the Second Vatican Council and shared conversations with leaders of the movement formed by Virgil Michel’s leadership. He brought the theology of the Mystical Body to Casa Juan Diego, where knowing that we are a part of Body of Christ sustains us as we go about our daily practice of the Works of Mercy.

Catholics of the Archdiocese of GalvestonHouston, members of the Mystical Body, come to Casa Juan Diego to help and serve in many ways. Our gratitude goes especially to the priests who come to celebrate the Eucharist with us on Wednesday evenings with all of our guests so that we can keep the vision and understanding of the Mystical Body before us, and the guests of our houses can also be formed by it.

The theology of the Mystical Body keeps us focused as we try to respond to one more request from a guest, in trying to respond to the needs of so many who come to our doors, as we try to get help for a suicidal young woman with the help of the HPD, as we pray with our guests when one of our men died a couple of weeks after being hit by a car as he crossed a street in his wheel chair, as the whole community of our men’s house, Casa Don Marcos, responds when one of the men has fallen from a ladder and is now in a wheel chair, joining our other brave young

Timothy Gabrielli presents the arresting possibility of a contemporary renewal of the theology of the Mystical Body, making connections between the work of Virgil Michel and contemporary French theologian Louis Marie Chauvet. When we think of the liturgy and the Mystical Body of Christ and Chauvet’s thought, we realize that gift is intertwined with kenosis, the love and sacrifice of Jesus for us, remarkably different from consumer culture.

The Mystical Body of Christ and Casa Juan Diego Mark Zwick participated in the liturgical movement

us to be alive here and now, to assume flesh in the world.

The Eucharist impels the Christian toward concrete ethical action—being Christ, loving as Christ loved, for the sake of the world.” (p. 162.)

In the light of the interwoven Benedictine tradition of the Mystical Body, and hospitality for the stranger, it is very understandable that Dorothy Day’s cause also lists her as a Benedictine.

men in wheel chairs who keep up their spirits in community, all members or potential members of the Mystical Body of Christ. May we embrace a renewal of the theology of the Mystical Body of Christ, liturgy, and Christian life so that we can live as Gabrielli asks, from the perspective of the great theologians of the Mystical Body: “God wants

L. V. Díaz

Liturgy and the Mystical Body of Christ

by Dorothy DayReprinted from The Catholic Worker, January 1936

What is the connection between liturgy and sociology?

Why do we stress the importance of the liturgical movement?

Here is our simple explanation: Individualism has been discredited. Catholics cannot go to the other extreme of collectivism We must uphold personalism as a philosophy.

The basis of the liturgical movement is prayer, the liturgical prayer of the church. It is a revolt against private, individual prayer.

St. Paul said, “We know not what we should pray for as we ought, but the Spirit Himself asketh for us with unspeakable groanings.”

When we pray thus we pray with Christ,not to Christ. When we recite prime and compline [the Liturgy of the Hours] we are using the inspired prayer of the church. When we pray with Christ (not to Him) we realize Christ as our Brother. We think of all men as our brothers then, as members of the Mystical Body of Christ. “We are all

members, one of another,” and, remembering this, we can never be indifferent to the social miseries and evils of the day.

The dogma of the Mystical Body has tremendous social implications.

Once we heard a woman at a Catholic Action convention say, “Are you going to the liturgical lecture?” and her friend replied, “I am not interested in music.” Many people confuse liturgy with rubric—with externals.

Again we urge…our readers, to join with us in liturgical prayer. When we pray in this way we recognize the universality of the Church; we are praying with white and black and men of all nationalities all over the world. The Communist International becomes a pale thing in contrast.

Living the liturgical day as much as we are able, beginning with prime, using the missal, ending the day with compline and so going through the liturgical year we find that it is now not us, but Christ in us, who is working to combat injustice and oppression.”(https://www. catholicworker.org/dorothyday/ articles/296.html)