THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

REVIEW

#BritishArmyLogistics

Bringing together logistics professionals from Defence, Industry and Academia 2024 THE RLC

Care & protection of materials Land Sea Inbound to manufacturing Defence logistics compliance Physical movement of assets internationally Air

THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 1 CONTENTS 8

2 – Foreword. By Maj Gen Angus Fay CB 6 – Great leaders must also be good followers. An interview with Brig Patch Reehal MBE 14 - Was it easy? Was it worth it? An interview with WO1 Susan Kier RLCF SPECIAL 18 – Additive manufacturing and the MOD. By Mr Peter Shakespeare HISTORY 22 – Cutting the Centre Line. Op GARDEN case study. By Maj Colin Taylor RLC 35 – Promotional Feature. The Duke of York’s Royal Military School. 36 – The Arsenal of the Alliance. Lend and Lease. By Maj Andrew Cox RLC PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT 42 – The Army Higher Education Pathway. 44 – Understanding Effective Reflective Practice. By Maj Leon Berry AGC 47 – Leading Through Workforce Challenges. By Capt Louis Trup RE 52 – Leading a Different Generation. By Capt Aidan Welch R IRISH OPERATIONS & TRAINING 55 – The Enablement and Reinforcement of NATO. By Maj Nicole Evans RLC 61 – 17 Port & Maritime Regiment RLC. By Maj David Levens RLC GENERAL INTEREST 66 – Is the Ukraine Crisis the West’s Fault? By Lt Bethan Lambe RAMC 70 – Recognising Health as a Vital Component of Security. By Lt Gethyn Chadwick RLC 76 – How will Robotics and AI shape conflict? By Capt Simon Smith RLC 80 – Should The RLC adopt a four-day week? By Lt Barney Lowe RLC 84 – The Prince Consort’s Library 86 – The MGL’s Reading List 2024 90 – The RLC Foundation Book Club 97 – Glossary of Terms Security: This Review contains official information. It should be treated with discretion by the recipient. ©Crown Copyright: All material in this Review is Crown Copyright and may not be reproduced without the permission of the Regimental Association of The Royal Logistic Corps. ©Cartoons are copyright. Disclaimer: No responsibility for the quality of the goods or services advertised in this Journal can be accepted by the publishers or their agents. Advertisements are included in good faith. The contents of this Journal and views of individual authors or units does not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or otherwise, of the Corps or Ministry of Defence. Data Privacy: We distribute The Review using mailing data held in a secure contacts database within RHQ The RLC. Your inclusion on this database is by virtue of the fact you are serving in the military, or you are a current member of the RLC or Forming Corps Associations. The RLC Association only uses your personal data for the purpose of sending you the magazine. The mailing data is treated in the strictest confidence, is password protected, is only shared with our printer and is deleted after each use. If any serving RLC personnel have concerns with regards to the storage and use of their personal data they should contact RHQ The RLC's Data Protection Officer is Maj Carnegie-Brown. Email: Alistair.Carnegie-Brown100@ mod.gov.uk. Members of the Associations should contact RHQ The RLC's Personal Information Risk Manager. Email: RLC RHQ-RegtSec-SO2-Asst@mod.gov.uk Cover photographs are from The Sustainer magazine Editor: Mr Peter Shakespeare Assistant Editor: Anne Pullenkav Graphic Design: David Blake Printed by: Holbrooks Printers Ltd.

THOUGH LEADERSHIP

Welcome to the RLC Foundation’s 2024 Review. For industry, wider Defence, the Army and the Corps, the marked increase in polarization of international relations over the past year has resulted in a significant shift in the character of a broad range of security concerns.

The war in Ukraine continues to refocus how NATO and its allies have to address the immediate European threat posed by Russia, made more challenging by conflict in the Middle East. In CGS’ last two RUSI Land Warfare keynote speeches, he emphasised his singular focus; Operation MOBILISE, with the strategic intent to help prevent a general war in Europe. Whilst he identified that the Army, within a wider joint/coalition context, must be able to function across all five operational domains, he stipulated that any decisive effect would probably take place within the Land domain. The implications for The RLC and its corporate partners might seem obvious, but there are some nuances which may determine how some of the Corps’ functions are to be delivered in the near future.

Whilst there are similarities to the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, there are also some stark dichotomies which need to be considered if our contingency plans are to remain credible. Experiences from Ukraine could generally be considered as a contest to survive and operate in a dispersed battlespace where deep strike, stand-off surveillance and temporal mass all play a part in state-on-state actions – not so in Gaza. As witnessed in the cities of Grozny and Sadr, the urban environment presents a different character to the spectrum of conflict and requires the careful application of a diverse set of skills and technologies to operate within them. Today, over half of us live in urban areas, with more than 80% of GDP generated from within this subenvironment. To support efficient social living, by 2050, it is envisaged that 68% of the world’s population will dwell in what could be categorised as an urban area. Congestion epitomises this land sub-domain, made up of thousands of structures, millions of civilians and reduced opportunity to employ complex weapon systems or the ability to manoeuvre for advantage. It seems logical therefore that if a desired military effect is to be realised in this domain, military forces will be compelled to compete in this highly attritional, uniquely human environment, whilst concurrently prosecuting other operational lines of development across a dispersed battlespace. For liberal democracies, applying military power within urban areas poses a myriad of complex challenges.

Due to their adopted doctrines, Western armies generally want to operate across broad vistas, where

their manoeuvrist approach and complementary technologies can best be applied, and where advantage is maximised by deep strike, teed-up by stand-off intelligence assets, all designed to mitigate risk to friendly forces. Based on the actions of the belligerents participating in the 55 global conflicts currently recognised by the UN, it seems unlikely that technology alone will help formulate credible strategies. Challenging economic factors, partially driven by growing environmental considerations, are likely to accelerate this belief in efficient urban living, posing further challenges for our armed forces. These challenges are exacerbated by the adherence to accepted democratic liberal values, monitored by a rules-based international system, fueled by a 24-hour media cycle. In this fetid environment, potential breaches of legality and proportionality not only threaten to compromise coalition consent but may also jeopardise the support from national home fronts. Technological solutions that offer an advantage across a dispersed battlespace can be significantly nullified in these choked and scrutinized urban areas. Even stand-off weapon systems, slaved to the latest sensor technologies, can be compromised in cities. The lethal effects of precision weapon systems are likely to be degraded due to risk aversion or may even be deemed unsuitable. In this context, the complex operating environment just got more complex, with the result that the British Army, and by default The RLC, must possess the capabilities to survive and operate against a peer enemy, using a broad spectrum of skills and technologies. In order to compete in such a febrile environment, the current CGS identified that Defence must harness every advantage where, “we must take industry with us and have the right relationships with our enabling agents to deliver…the ambitious targets we have set ourselves.”

The RLC Foundation was designed to operate within this broad coalition of military and commercial enabling partners. If the Army is to mobilise and meet the nation’s immediate threats, CGS recognises that industry is a vital component in achieving the desired future strategic and operational endstates. Every generation believes it lives in extraordinary times, but we must be careful that our lived experiences are not allowed to skew our vision for future contingency planning or fall into the trap that specific novel technologies offer a panacea to combatting every emerging threat. What is clear is that we have to continually adapt and adopt approaches that support what has been labelled a high tempo prototype war, whilst cognisant of the relevance of hard-won historic experiences.

Anyone who participated in, or witnessed, the

8 FOREWORD

2 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

British Army’s largest formation exercise in two decades (Exercise IRON TITAN 2023), will be left in no doubt what Commanders 3rd UK Division and 101 Operational Sustainment Brigade were aiming to expose. We are now clearly evolving from a mechanized force to a digitized one. If we are to harness the benefits of the fourth industrial revolution, we have to quickly identify emerging technologies, reinvest in stockpiles, become comfortable with rapid training regimes and normalize the fielding of partial solutions, whilst continually upskilling our workforce - all in line with commercially competitive timelines. This is why, with industry’s support, we have to accept the necessity of deploying with a large proportion of prototype solutions. Whilst our workforce has proven to be agile at rapidly adopting cutting-edge technologies, we have to recognise the capabilities and limitations of our industry partners. Perversely, in an effort to maintain a competitive edge, successful commercial enterprises have operated for decades with a lean approach to managing expensive resources. Unlike the shadow factories administered and funded by central government in the last war, industry, by design, has little built-in latent capacity for increasing productivity at short notice. Mobilisation is therefore not restricted to the military domain, and a greater understanding of commercial practices, capabilities and limitations is needed if expectations are to be managed and Defence is to avoid being caught short.

In essence, this is where the RLC Foundation offers an insight for all its members into the capacities and capabilities of the military and corporate worlds. Over the last year, over 400 members have physically participated in a dozen Foundation events across the country, with many more benefiting virtually. We have successfully attracted three new corporate organisations and welcomed individual honorary membership from senior appointments in the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. In line with CGS’ intent, the critical requirement to develop deep seated understanding across Defence and industry is being directly supported by the RLC Foundation and its corporate members. In many ways, the articles in this Review are testament to this augmented partnership approach. The four submission categories have once again attracted some high-quality articles ranging from specific NATO structural transition, to upskilling opportunities, analysis of historic campaigns which help to expand our lived experiences and reflection on some emerging technologies. I’m also delighted that

RLC Foundation Review

The 2024 RLCF Review Best Article: Major Colin Taylor RLC - £200

for the first time we have submissions from students on the Army Higher Education Pathway (AHEP) together with their reflection pieces. Whilst readers may not agree with all of the author’s conclusions and recommendations, each article has been selected for its thought-provoking analysis and insights. Once again, I congratulate all authors who have been selected for publication. Some authors have the added bonus of being recognised with the award of a cash prize and I thank our corporate members for their continued generosity and support to the RLC Foundation Review in this particular area. With this in mind, I encourage commanders and managers at all levels and from across every category of membership, to seek out and support potential authors in submitting articles – everyone has a valid opinion, lived experience and/or vision, I would ask that you enable them to share it in the 2025 RLC Foundation Review.

As well as the Review articles, I am delighted that much of the changing environment described above is captured in interviews from two of the RLC’s gifted leaders; Brigadier Patch Reehal MBE and WO1 Susan Kier. Their backgrounds, experiences, challenges and opinions are unsurprisingly different, but their attitudes and thoughts on the British Army are candid and reassuringly similar.

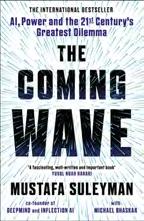

Finally, for the first time, you will find MGL’s Professional Reading List has been published in full in this Review. This list was initiated by the Foundation some years ago and publication entrees have been managed over the last three years on our member website. The quarterly updating of the list is undertaken by systematic corralling of publications and mixed-media from across a broad spectrum of disciplines – all relevant to military/commercial logistic practitioners. To date, well over a hundred books, journal articles and mixed-media products have been reviewed and published on the Foundation website by the in-house Book Club, whose aim is to keep MGL’s list current. To supplement MGL’s Reading List, this Review also includes an extended Book Club, authored by an academic who focuses on one of the acute conundrums for the human race – adaptive AI and some of its potential implications.

I hope you enjoy this year’s wide-ranging RLC Foundation Review. I look forward to receiving your submissions, ideas and publication selections for our 2025 edition.

Angus Fay CB MMAS FCMI FCILT Chairman, The Royal Logistic Corps Foundation

2024 Prize Winners

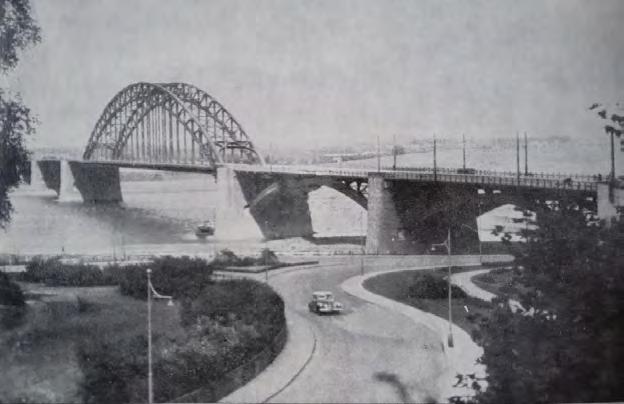

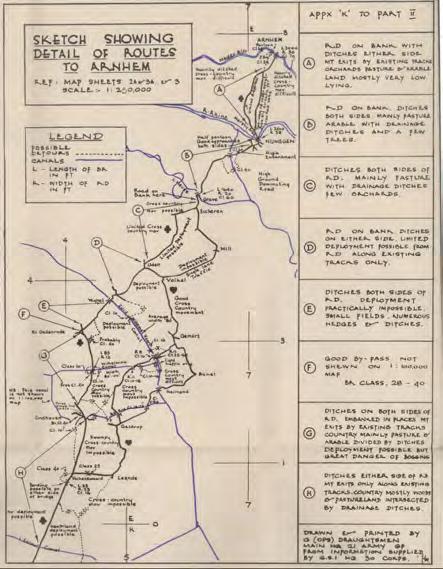

History Category: Maj Colin Taylor RLC - £150 ‘Cutting the Centre Line - Operation Garden, ‘Hell’s Highway’ and ‘Porous’ front lines’.

Professional Development CategoryMaj Leon Berry AGC - £150 - Understanding Effective Reflective Practice.

Ops & Trg Category: Maj Nicole Evans RLC£150 - Planning Enablement and Reinforcement of NATO forces at scale; the key role of the Joint

Support and Enabling Command (JSEC) in NATOs Deterrence and Defence of the Euro Atlantic Area and implications for the UK.

General Interest Category: Lt Bethan Lambe RAMC£150 - The Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault: An Evaluation of John Mearsheimer’s Structural Realist Claim.

Special Merit Award - Capt Simon Smith RLC - £100 - How will robotics, autonomous systems, and artificial intelligence shape conflict?

FOREWORD 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 3

What is it?

The RLC Foundation was established in 2015 to provide the focus for engagement with industry and academia, for the purpose of professionalising

The RLC’s officers and soldiers. As we enter our eighth year, we have established strong working relationships with a wide range of industry partners and many academic institutions. Our corporate partners, supporters and friends continue to enable the Foundation to flourish and develop it’s professional and academic standing within the community at large. One of our main objectives is to enable members of the Corps (regular, reserve and veterans) to follow a professional career development path which is recognised with credibility as logistic professionals within Defence and across industry. We are already seeing the benefits of our collaboration with industry and academia across many on-going initiatives. There are obvious benefits for those in career transition and our website www.rlcfoundation.com has links to career opportunities with our corporate partners.

Where is it?

The RLC Foundation is based at 101 Log Bde, Wellington House, St Omer Bks, Aldershot. Both Alan and Marti work from the office and occasionally from home and can be contacted at: rlcfwoods@ gmail.com or therlcfoundation@gmail.com

What does it do?

The Foundation runs a diverse range of national events with industry and academia as well as supporting

regional events in support of the RLC’s Regular and Reserve regiments. Over the past year we have run a hybrid of live and virtual events and these have both been well supported by the Corps at large and our corporate membership. Our main events for 2024 are:

15 Feb - Defence Support Training & Transformation Conference, T1, Bldg 101, Worth Down Camp

18 Apr - DHL Supply Chain Insight Day at East Midlands Gateway, Kegworth, Derby

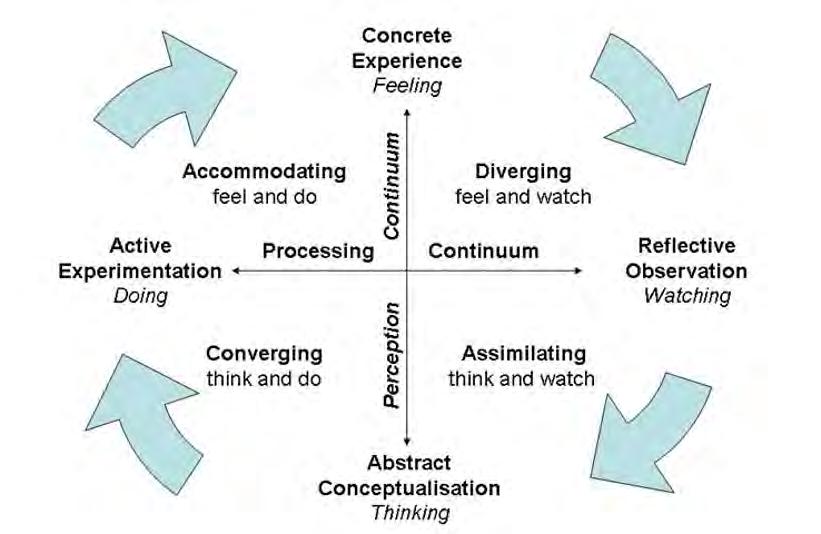

Apr (date tbc) - Unipart event

15 May - Navy Command HQ visit and brief of maritime logistics, Portsmouth

Jun (date tbc) - RAF event. Either Air Power demo or visit to a RAF operational airbase

5 Jul - Corps Cocktail Party, Worth Down Camp

16 Jul - Exercise LOG SAFARI, Barton Stacey Training Area

Sep (date tbc) - 13AASR Military Planning Event, Colchester Oct (date tbc) - PA Consulting event, Cambridge

19 Oct - Logistic Leaders Network Annual Awards Dinner, Crowne Plaza Hotel, Stratford-upon-Avon

26 Nov - RLCF Awards Dinner, Combined Mess, Worthy Down Camp

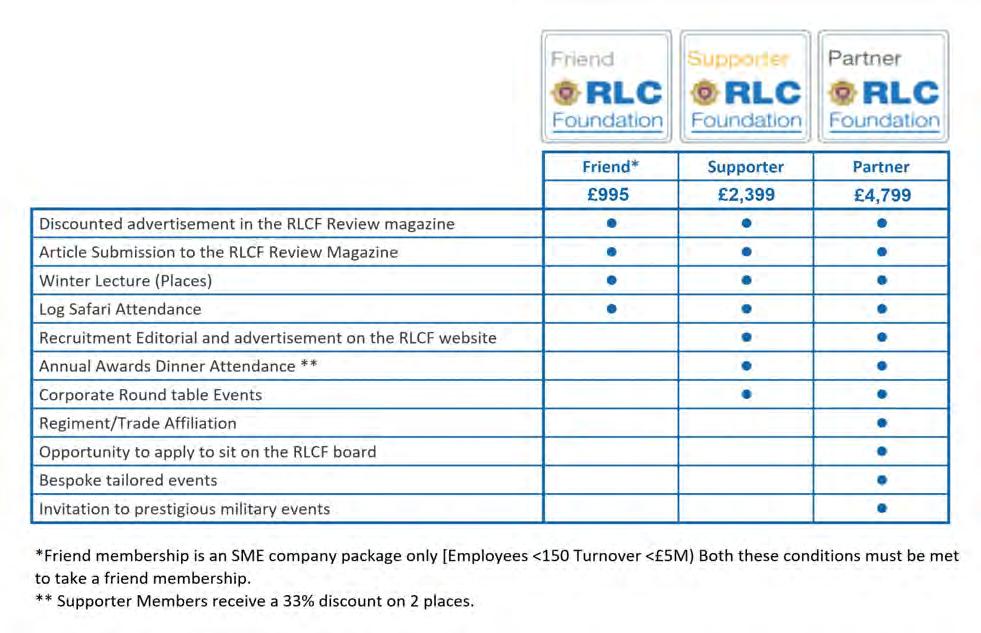

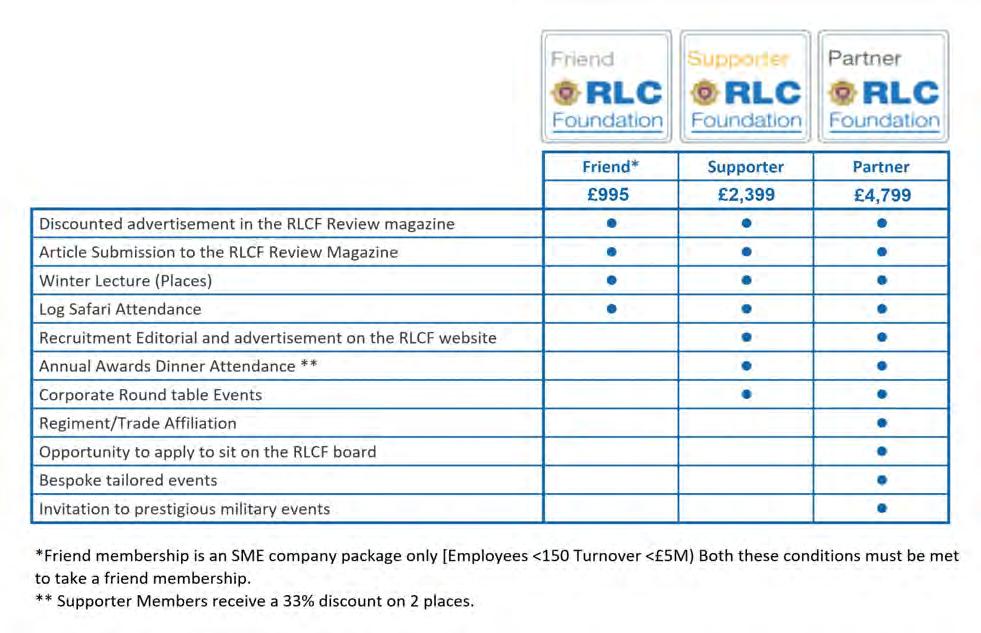

Why Should I join the RLC Foundation?

We offer a wide range of events throughout the year, giving our corporate members exposure to The RLC and its people. This is a unique opportunity to interact over evolving logistic capability and promote best practice between The RLC, industry and academia. We are actively seeking new members and the three levels of membership can be seen below.

Our website address is www.rlcfoundation.com

We are also on Facebook and LinkedIn. Please feel free to contact us if you need more information about the RLC Foundation.

8 ABOUT THE RLC FOUNDATION 4 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K

8 RLC Foundation Director, Alan Woods and Business Support Manager, Marti Jerrard

In spi r e. Empo w er. Deliv er.

Proudly committed to supporting service leavers in pursuing new careers

From Drivers to Warehouse tradespeople, Account Managers to Solution Developers, we’ve got a range of roles available across the UK. Join our team and you’ll get extensive training, professional development, CPC driver license conversion and competitive rates of pay.

As a Gold Armed Forces Covenant holder, we’re committed to supporting the Armed Forces and Defence communities. We believe in bringing people and goods closer together by innovative and sustainable business solutions across air, road, sea and contract logistics.

Scan this QR code to find your next career opportunity

Great leaders, must also be good followers

In late 2023 The RLC Foundation was fortunate to speak at length with the then Commander 101 Operational Sustainment Brigade, Brigadier P.S. Reehal MBE, about leadership, the future direction of CSS and the vital part reading plays in personal and professional development

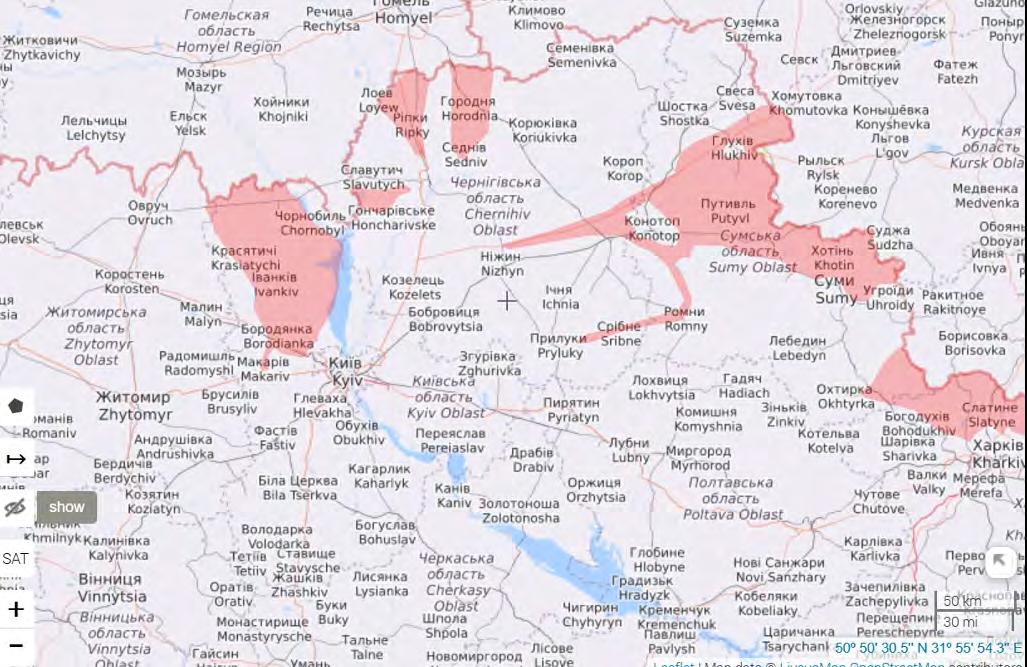

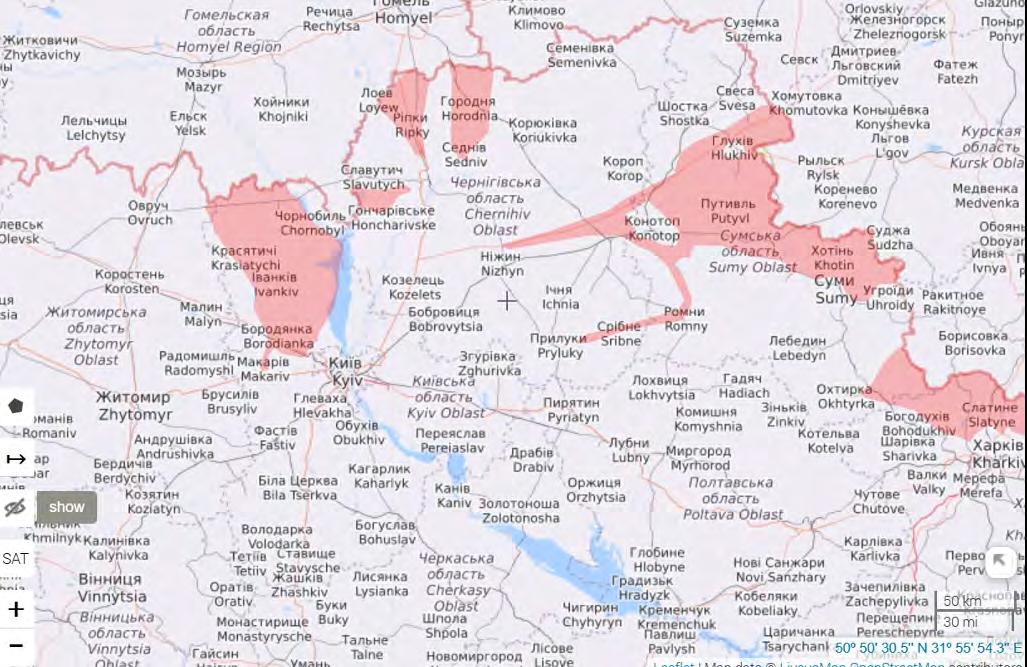

Considering your previous postings, training and experiences, how well prepared were you for your formation command appointment?

Pretty quickly, you come to realise that everyone is an incomplete leader and that we all need to adopt a philosophy of persistent learning. With effort, no matter how good you are, or think you are, we can all get better. I come from a background with a very long martial apprentiship – some outside of the Army. I’m one of three brothers, all of us have served. My middle brother, Ben, is currently one of my commanding officers (27 Regt) and my youngest brother, now a doctor, served as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm. He continues to serve as a medical officer to one of the Rifle battalions. So, there is a common thread between us, and I’m being sincere when I say that I’m a patriot. I believe in service to the nation, albeit that I recognise that it’s a slightly unfashionable way of expressing your convictions. Much of my belief is cultivated from a rich seam of military service throughout my family. Both my parents served. My mother, despite having to leave the Army in 1975 to have me, still looks back at her service with a sense of pride. My father, with three serving generations from Irish heritage before him, completed 36 years in the military. He started in the Royal Marines then

transferred to the Royal Signals, later commissioning into the Royal Corps of Transport, the first officer in the family. He finished his long career in the RLC. At one point, the three serving Reehals were joined by my uncle’s son Jamie. Now, without prompting, both of my sons are serving with the Royal Marines.

I’m in no doubt that this formative growing up period overseas, within a close Army community, helped to shape my character. This positive cultural experience still influences my contemporary decision making. I came to appreciate what the Army could offer, not only as a career, but a way of life. When I look back at my family lived experiences, and I sometimes employ this knowledge on our operational teamwork days, I use it to exemplar the significant changes that have occurred in the military during the relatively short period of my and my parent’s lifetime. This is important. There might be points in time when we think that the Army is trying to overcorrect something very quicky, instant reaction if you like. In reality however, it has just reached a natural pivot where the Army is correcting something that it has always suspected to be wrong. My pre-service, lived experiences have therefore provided me with a degree of first-hand knowledge of an Army in a state of constant transition, albeit, Q A

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 6 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

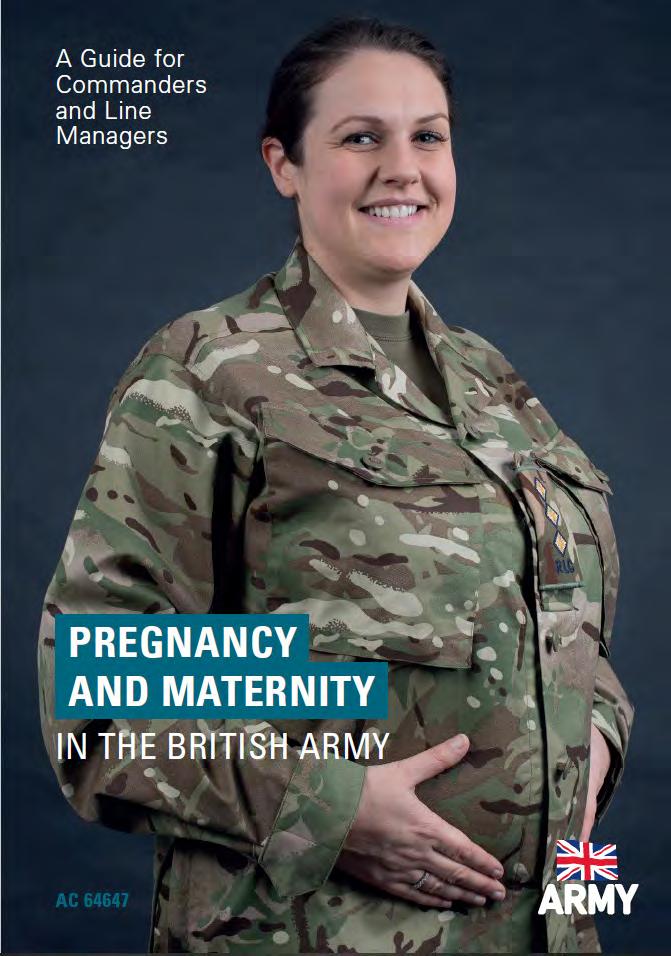

sometimes at a frustratingly pedestrian pace. From these experiences, I find that I can better judge the changing environment we find ourselves in. I suppose what I’m talking about is having the luxury of a longer perspective on the military community at large – an extended lived martial experience compared to many of my peer group. It’s something that I find myself tapping into when I’m required to consider a whole range of complex cultural and operational challenges. Taking my mother’s experience as a single frame of reference; it wasn’t until the 1990s that the regulations were changed for pregnant personnel to remain in service. When we therefore think of short, medium and long-term changes, I have witnessed, first-hand, the military institution making some significant modifications and amendments to our conditions of service. So, this was the environment that I was incubated in, a long and informal apprentiship with priceless experiences of the conceptual, physical and moral components of the Army. To offer another personal insight, my father served in the first Gulf War whilst I was at school. I remember watching the operation on television. From that immersive experience I have always thought more broadly than operational missions. I constantly reason how we prepare and stay connected with the home base to support our families as part of the wider moral component. I think this is largely down to the fact that before I joined the Army, I’d experienced over ten years of schooling in garrison life and was subsequently immersed in the broader aspects of the Army’s values, standards and challenges.

Looking back, I recognise that I was always going to join the services, it was a moral calling if you like. I care deeply about the institution, what the Army stands for - a force for good, with an enviable global reputation. I’m conscious that in the cold light of day, such a confession could well be construed as sycophantic and/or cheesy – but I really mean it, so there it is. Now we get to my time in the Army and how I think it has prepared me for formation command. If I were to summarise it with a bumper sticker, it would be, ‘very well prepared,’ but my answer comes in two qualified and distinct parts; separated into formal and informal components.

The formal demarcation runs through staff training periods, your staff colleges and programmed learning episodes. Here you are tutored in land or joint environment experiences in the conduct of warfighting/soldiering. Overall, I believe this tutoring equipped me well in applying the basic tools in terms of understanding the application of fighting power, both conceptually and physically within a joint environment. I was fortunate that these periods of formal learning were further honed in my joint postings in Permanent Joint Headquarters. These postings allowed me to experience different parts of defence and build a network which has helped me breakdown some unhelpful single service bias, judgements and apocryphal tales. I suppose the formal training, combined with my postings, have allowed me to develop into a joint officer conceptually and physically.

Perhaps however, my formal training has been less valuable within the moral component space. I’m comfortable in recognising that I’m more EQ than IQ, which is undoubtedly a product of my family wrapper.

The best moral component learning I’ve had has been informally from others. Good leaders, not so good leaders, good followers and not so good followers. I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve been immersed in situations where I’ve witnessed people arrive at logic and make good decisions using the information they have. What’s struck me is that as officers, we are obsessed with being good leaders as opposed to also being good followers. In my experience, the academies have come to this space late and left the crucial traits of leadership; decision making, listening and following - largely to the informal periods of learning. Emotional agility and intelligence, where you deliberately explore introverted/extraverted characteristics and the way people think, was a taboo area and when I was a junior officer, people would either have shunned it or wouldn’t have known what you were talking about. I often think about simple things that I’ve now done, and wish I’d done them earlier in my career. I completed a change management course as a full colonel, where I learnt about the psychoanalyst, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. I quickly realised that I aligned to Ross’ curve, more by trying to be a decent human being, listening to people and luck, rather than through training. If I’d known more about the fundamentals of change management as a second lieutenant, my goodness, as an officer working in an army that was required to anticipate and respond to constant change, I think I’d have been better equipped to make sound decisions and been an all-round better leader. If I’d known the difference between someone being very quiet and sitting in a corner and assuming that they’re a bit dull or without zest, to realising that they’re an introvert and probably taking everything in, I think I would’ve made better decisions. As a leader, the challenge is not only identifying the characterises of the individuals in your team, but how to get the best out of them for the benefit of the whole organisation by capturing their ideas. I’m not saying that you need to Myers-Briggs everyone, but there are fundamental aspects of personality, nuanced inter-personal skills, and a way of developing empathy that I should have learnt a lot earlier in my career. These personal management skills are what I regard as being key to establishing a moral component baseline. From this foundation, leaders can equip themselves to better execute their responsibilities. Using these invaluable facets in my command appointments, I’ve learnt the importance of listening, not just the popular ‘active listening,’ but genuinely listening. I’ve also learnt to identify the best time to make a decision. If time allows, I don’t see asking for more information to help contextualise issues, as a weakness – on the contrary, rushing to a judgment is. These learnt leadership and management traits have allowed me to understand how my team are constructed and equipped mentally. You need to be aware how individual members think and problem solve, if you’re to avoid ‘group think’ ideas and solutions. If you get this right, you may be able to blend a gifted group of introverts and extroverts, often working to different design systems and problem-solving techniques, to deliver credible solutions that can be communicated and understood. Ultimately, these carefully considered decisions normally far exceed the sum of the parts of the team. I learnt how to communicate at different levels as

RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 7

a commanding officer, but I believe that I’ve really improved this essential skill as a brigade commander. I’m now better at recognising the needs of different audiences and can adjust my style of communicating to ensure they get an unambiguous message. In a way, being able to judge what your audience needs, for their immediate and longer-term understanding, allows them to distil the information and pass it on in a timely fashion, with brevity and clarity – it’s an invaluable learnt skill. Everyone will be schooled to some degree by their experiences, but good leaders will recognise that they need to constantly improve the way they communicate if they want to have real impact across their commands.

I acknowledge the importance of formal training, but I also recognise that in this long apprentiship, many skills will be learnt, re-learnt and improved in an informal way. That’s not to say that some aspects of leadership should be explored in greater depth in the formal training environment, especially at the more junior levels. That said, recognising the informal opportunities to improve, challenging yourself, forcing yourself to operate outside of your comfort zone, can pay real dividends throughout your career. As people progress through the ranks, what might be regarded as soft skills, have a habit of quickly developing into critical skills in hard environments, especially as responsibilities increase. What I’d say is that everyone should make the most of the time and opportunities available to them to hone their leadership skills - otherwise you might, as I’ve alluded to, regret not investing in the available time and space when you find yourself in command. When you get there however, don’t be afraid of recognising that you’ll likely still be an incomplete leader – what counts

is recognising what you haven’t got and formulating a plan of what you’re going to do to improve yourself.

Finally, what I’ve learnt in the last five years is that it’s perfectly OK not to change some of our inherited plans. With the two-year cyclical nature of many appointments, there is definitely a temptation to believe that we have to articulate something in a plan that needs to be delivered within the life of a single incumbent. What I’ve realised is that this is unlikely to be helpful to an organisation and the people in it, because it’s unnatural. Although you could argue that there is a degree of narcissistic behaviour in all of us, we should be aware of it. Imposing change within a self-imposed timeframe can be deeply unhelpful and, where appropriate, we should refrain from making change for change’s sake. In the last job I did, in Head Personnel Strategy, it would have been easy to have been a disrupting force and orchestrate change, but sometimes it takes a degree of experience and confidence to acknowledge when your predecessor has done a great job, and the plan remains extant. If this is the case, don’t change things unless you are convinced that the evolving context warrants it. If you’re fortunate to be in this position, then you should lead the plan and support the staff in delivering it. This aspect of leadership comes back to my point of being a good follower. Sometimes we should refrain from the obsessive temptation of consistently demonstrating the outward traits of leadership and instead adopt the stance of an engaged follower, ready to touch the tiller, if necessary, but offering space for teams to deliver their prescribed outputs.

QThe 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (IR) provided the strategic direction which led to a general logistic disaggregation as CSS units were either task organised into the division or disbanded. Notwithstanding that, as a result of the IR, 101 Bde is smaller in form but not function, how confident are you that after IRON VIPER, and predetermining the outcome of IRON TITAN, that land logistics is now better aligned to delivering the outcomes articulated in the IR? Given that much of the Army structural changes have largely been actioned, how does future CSS training get included in combined arms manoeuvre and who is championing this?

AThe way I think about these questions is that morally and conceptually, we’ve been in the gym preparing. We’ve achieved a lot through hard, focussed training, and we’ve got our core fitness into reasonable shape. From this I’m very confident that, in these two areas of warfighting, we have a proven capability we can build on. We’ve also supplemented this with activities in support of Ukraine and the NHS, which has generally been conducted at very high readiness, undertaking life-saving interventions which required instant decision making. We should gain some confidence that these activities have all been achieved at reach, by some of our most junior people. So, morally and conceptually, I have a very high degree of confidence in our fielded abilities. I think I can continue to say that; as long as we continue to train the moral component and keep it strong in the conceptual space, whilst also ensuring we understand our role, purpose and prioritisation

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 8 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

towards sustaining combined arms manoeuvre in a multi-dimensional domain, we’ll remain in a good place. Physically, there is a different challenge.

In many ways, there’s nothing new in these questions and the answers form part of the broader philosophical historical debate between the physical and conceptual components [of fighting power]. All my predecessors have, to greater or lesser degrees, had to grapple with this challenge, albeit the context has been in a continual state of change for each of them. Inevitably, when they’ve deployed, they had to start the operation with the equipment they had and the associated tactics to complement their order of battle. So, when I look back at the historic evidence, in the physical space and the part of the fight that we own; the tactical and operational level, in the short, medium or long-term, I’ve a massive degree of confidence in the British soldier. I believe they retain the will, tenacity, initiative, guile and the innovative genius to deliver. That’s demonstrably been our strength, and I feel the same way about this brigade. What we need to be conscious of however, is that we don’t get seduced into accepting our frames of reference from the type of operations where we’ve proved very successful in the recent past. In logistic, and probably every other critical line of capability development, the recent past is a foreign country. The potential frictions we face in the contemporary operating environments are likely to be significantly different to what we’ve encountered and generally mastered. Conceptually, I don’t think the battlespace is going to look linear, and so we mustn’t restrict our thinking and physical laydown to lines of support through lozenges of logistic mass, but something much more fluid. The possible contemporary, not future laydown, is one that demands a consistently high tempo from all force elements, prioritised to meet credible and sustainable plans of manoeuvre. We must therefore practice and demonstrate agility at every level but especially the tactical and operational, if we’re to compete with a peer enemy. As the Deputy Chief of Staff in 3 Division, and as Brigade Commander here, I’ve attempted to enable the development of these necessary capabilities. This is uppermost in my mind when we conduct Exercise IRON TITAN. By concentrating on sustaining some selected bulk commodities, I intend that we attempt to prove and dispel some logistic myths. You can therefore expect the exercising of three things. To achieve and maintain momentum we will develop our ability to generate high tempo relative to the enemy, we will practice our ability to survive and operate in complex terrain and I aim to comprehensively demonstrate frequent logistic resource flow - rather than operate large, semi-permanent lozenges of default stocked materiel. Mass will always be a factor, but it will - by necessity against a peer enemy - be a temporal one which needs to ebb-and-flow to meet operational demands. Where I believe mass is unnecessary, commanders at all levels should act as a repellent and develop a standard operating philosophy of dispersal rather than permanent or semi-permanent massing. It's also worth mentioning tempo; how we generate it and what to expect. When you study the relative tempo of the belligerents on an historic operation, a pattern emerges. Nobody can sustain more than three or four days of high

intensity combat before you witness a cliff-edge drop in capability. We should therefore expect periods of lesser intensity where we optimise our refurbishment and, if necessary, regeneration. There may well be what I call a cheeky week of activity which will prove testing, but I would argue is realistic. We shouldn’t expect a cheeky week every week however – if it is, our capability will undoubtedly show some decline and our resilience will be eroded, together with our end user’s confidence.

It’s probably worth mentioning that I don’t intend to conduct this level of training and investigation in isolation. Uppermost in my mind are the other operating environments and likely partners which bring greater enabling and force-multiplying capabilities - but also some potential friction. I intend to conduct some deep dives into our partner’s requirements and our ability to cross service specific commodities. So many of the things that can restrict the flow of commodities through our supply chains need to be identified and explored. Only when we’ve done this will we be able to quantify what can be sustained, under what conditions and what the inherent risks are. If we can get all this right, we can avoid what General Rupert Smith referred to as, ‘logistic constipation.’

So, the question of fit-for-purpose structures is answered only by doing, not just as a single event but repeated over time, with logistic ‘load’ placed on specific functions. Some of the answers I already have, but you’ll not be surprised that I want to go further, validate, consolidate and go again; to not only prove our concepts but to make them more agile, relevant and resilient.

The IR describes how 'Global Britain in a Competitive Age' intends to conduct itself utilising cross government departments to deliver desired strategic and operational outcomes. To help deliver this competitive edge, technology is recognised as playing a big part. How confident are you that a technological edge is being maintained across the CSS functions which optimizes the talents of our people?

This is one of our most challenging areas for development and maintenance of competency - not just for CSS or the Army, but for wider Defence

RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 9

Q A

and our potential coalition partners. I’m confident that in some areas we are making real progress, but the challenge is so great that it shouldn’t come as a surprise that there are some areas where we need to do more – and at a high tempo. I’ve full confidence in our people’s ability to adapt and progress through a learning curve where they master some of the emerging technologies and deliver favourable operational outcomes. How acute that learning curve is, however, is down to a number of supporting and conflicting areas. Identifying technologies early is one factor, but just as important is being prepared to take procurement risk i.e. weigh up the dangers of adhering to a procurement cycle which attempts to de-risk all the financial and delivery requirements - against the physical dangers of not fielding a capability in a timely manner. This has been a recent discussion point for the Defence Select Committee and Service Chiefs. With this in mind, we should develop an expectation that sometimes we may fail in seeking novel solutions rather than restricting procurement activity to narrow financial and overly exacting technical requirement boundaries. So, our people have the skills sets which allow them to adapt quickly but they have to be afforded a high tempo mechanism which supports timely innovation and fielding. What we need to ensure is that we continue to attract people who have the ability to adapt and give them the confidence that they’ll be supported when they make suggestions on how solutions can be grown. When we recruit, I’m convinced that we not only need people to start on a common baseline where they learn from a mixture of formal training and doing, but we must also look to the gains we can make through adopting a programme of lateral entry.

Again, this is all part of the contemporary leadership and management conundrum, but there is definite merit in considering selection and recruitment

in a new paradigm, something which allows us to move away from thinking in narrow echelons of age and experience. We should take confidence that there is nothing new in this. In the thick of the 1915 British artillery shell production crisis and mobilisation of a million-strong deployed army, Prime Minister Lloyd George and Field Marshall Haig’s appointment of Sir Eric Geddes, a civilian railway executive, as an honorary Major General was inspired. Geddes, and his lateral entry hiring of civilian experts, can be credited with transforming our inefficient and stovepiped force support chains with the multi-nodal network of docks, railways, canals, light railway, and roads that would ultimately culminate in the success of the Hundred Days advance in 1918. Further British administrative agility was evidenced when Geddes later became First Lord of the Admiralty. I cannot recommend enough, the Corps’ very own Clem Maginniss and his ‘An unappreciated field of endeavour: Logistics and the BEF’ as an authoritative work on sustainment on the Western Front. The evidence that Clem provides explains both how we have historically exploited a wider than regular workforce and used it to power through the learning curve which every conflict demands. You can find similar examples of lateral entry from WW2 right up to Operation TELIC. As well as some lateral thinking on widening our human resource base, there are also some fundamental operating tools that we must get right.

All of our plans, and the opportunities we seek, are built on establishing and utilising a sustained operating picture. Commercial business struggles with this vital element in its various operating models. It supports their core business and allows them to manage their cash flow – so we’re not alone. I know where I want to go with optimising our logistic picture performance, and there’s much work to be done to

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 10 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

incorporate machine learning, ensuring we maintain a stable, deployable bearer system, where we can incorporate selected coalition partners. I’m in no doubt that if we optimise the technologies available and get the training line of development right, we’ll gain and maintain a competitive edge.

With regards to recognising, verifying and incorporating emerging technologies to allow us to optimise our deployed form and functions, it’s vital that we overcome some divergent challenges. I’ve already mentioned our procurement cycle, but at least for the various software applications and agile capabilities that we require, we need to adopt a flexible approach. If we get this right; from 3D printing, to avoiding bias in AI, (which could lead to poor provisioning), to using drones for distribution, to ensuring machine-human interfaces are constructed and assured within deployed systems – we can ensure each component part of our sustainment system is available for service when we need it. The challenge is that we have to be able to offer sustainment in an agile way; with a high degree of end-user confidence, using an optimised footprint which monopolises technologies that offer advantage but in an affordable way. Our procurement, training and fielding mindset will undoubtedly need to evolve. We’re not talking about capital items of bespoke military equipment that generations will work on, but relatively niche, high tech, transient capabilities, that may offer only temporal advantage. Pedestrian procurement models are an anathema to industry and our workforce when we seek competitive edge within our deployed supply chains. The current generation have no problem with adopting a prototype mindset, in fact, they expect technology to be superseded at a superfast speed. We need to recognise that if you don’t continually plan for upgrade then you risk user, and end-user, confidence in our sustainment system. Now we’ve mentioned risk, it’s probably also worth mentioning that to realise the potential advantages of adopting niche technology you need to encourage a new threshold for taking risk with our procurements in specific areas. 3D printed component parts may not be ISO 9001 compliant, but as long as we know the range of the operating spec within the mainframe they are being issued against, then it’s probably less risky to get the asset back in a potentially less capable state than wait. Whatever the technologies we adopt, they must offer us the ability to make timely decisions at a known level of risk, at a consistently higher tempo than a peer enemy. Technology must also make our support chains more resilient, definitely in the deployed space, but also in-barracks. If we can achieve this, then we would have gained a relatively high level of supply chain assurance for our end-users.

It’s clear that you’re an avid book reader, so can you describe how you find the time and space to read and digest your chosen material?

Yes, I am an avid reader. I probably read two books a week and I’m forced to clear about twenty books out of the family home every two months. My main focus is non-fiction, but I do steer into fiction as well. I don’t read one book at a time but have several on the go that I dip into. I tend to write

notes in each as ideas are triggered and keep them in the book for future reference (if I’m allowed to keep the book!). Currently, I think I’ve about five books on the go.

With regards military topics, I’m a big fan of the Pulitzer Prize winner, Rick Atkinson (The Liberation Trilogy: An Army at Dawn (2003), The Day of Battle (2007), The Guns at Last Light (2013) – all reviewed on the Foundation website and included in MGL’s Professional Reading List), which I really value. I’ve taken Atkinson’s books to Sicily and Normandy and found them so informative and emotive. I also read John Keegan (The Mask of Command, (1987) – MGL’s Reading List), General Stanley McCrystal (Team of Teams – New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, (2015)). On the more academic/strategic side, I enjoy Lawrence Freedman (Strategy (2013) – MGL’s Reading List).

I’m currently reading a book titled, The Wager: A Tail of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann (2023), a book about leadership of a ship’s crew pursuing the Spanish Armada. When it comes to leadership, I read a lot of 18th and 19th century naval books. I find life and death within the wooden walls fascinating. I’m a big fan of NAM Rodger (The Wooden World (1986), The Safeguard of the Sea (1997), The Command of the Ocean (2004) and Sam Wills, the Heart of Oak Series (The Fighting Temeraire (2009), The Admiral Benbow (2010) and The Glorious First of June (2011), is fantastic. Another book on my bedside table is Where Power Stops; The Making and Unmaking of Presidents and Prime Ministers (2019) by David Runciman, an account of world leaders and why they never achieved what they set out to do, as power is always bounded. I also have a book about Vietnam that I’m working through, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the undoing of Character (1994), by Johnathan Shay, a psychiatrist who compares the exploits of Homer’s Achilles with the experiences of Vietnam veterans. The last two books I’ve on the go are Atkinson’s, The British are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton 1775-1777, (2019) and Ham & Jam: 6th Airborne Division in Normandy - Generating Combat Effectiveness: November 1942 - September 1944 by Andrew Wheale (2022).

The book I’d wish I’d written is Principles: Your Guided Journal (2017) by Ray Dalio. From his personal experiences as a very successful hedge fund manager, he writes about the establishment of a unique set of principles that allow you to get what you want. Surprisingly, at the other end of the spectrum, the book I struggled to finish is Rupert Smith’s Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World ((2005) on MGL’s Reading List). Not to be overly critical of a hero of mine and recognising that the book was not solely intended for a military readership, I got through the first half of the book whilst I was serving in Iraq, but then found that his hypothesis on warfare was so close to the mark that it became a painful read. Undoubtedly, what Smith writes is fundamentally true, but at the time when I was reading it, it exposed the flaws in the political and military lines of development that the coalition was pursuing – it made me angry and uncomfortable. To contextualise this, if you read the MOD’s The Good Operation (2017), which not only outlines what

RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 11

Q A

questions need to be asked as we plan and execute military operations, it also articulates what you shouldn’t do. Its baseline is the Iraq Inquiry (Chilcot)

and so if you read it together with Utility of Force, and then place yourself on a tour in Iraq with soldiers who were doing their utmost to make a success of the given mission, you might see why I struggled to finish Smith’s book. Both publications chime with one another and there have been several publications since, such as Rory Stewart’s The Prince of the Marshes: Occupational Hazards (2007) which provide further critical context.

What you’ve got me onto with this question on reading is one of my pet loves and hates. I wish people would read - or read more. If you want to challenge yourself, read things you know that you’re probably going to disagree with. Develop a broad reading strategy and it’ll help you in so many ways; the mechanics of writing certainly, but also an ability to filter information, identify what is important, exposing weaknesses in an argument, the strength of presented evidence, and, ultimately, it might help you avoid the pitfalls of group-think solutions. MGL’s Professional Reading List and the Foundation’s Book Club offers a good baseline for those looking for some pointers. In my experience, we don’t read enough, it’s a potent skill where you can develop understanding, identify where flaws are and rectify weaknesses in the conceptual, moral and physical components –pretty much everything I’ve been talking about here.

I am Rick Jennings, an Independent Silver Consultant based in South Yorkshire. With over 20 years’ experience, I offer a wide range of services including accurate valuations for bespoke military centrepieces, sporting trophies and other pieces of silverware that provide organisations with a unique link to their heritage.

“If you want the best, look no further than Rick Jennings. The Regimental Headquarters of The Royal Logistic Corps would have no hesitation in recommending his services to others and looks forward to working with Rick again in the future”. Stephen Yafai, The RLC Regimental Secretary

If you would like more information or to book a valuation, please use the details below and I will be happy to confirm the number of days required to carry out the valuation along with cost and availability.

07970 712852

rick@rickjenningsconsultant .co.uk

www.rickjenningsconsultant .co.uk

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 12 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

RESULTS DELIVERED, CONFIDENCE EARNED

Delivering Digital Transformation in Defence

leidos.com/uk/logistics-mission-support

Was it easy? Was it worth it?

Currently appointed as the Warrant Officer Equipment Support at Headquarters London District, WO1 Susan Kier RLC has an inspirational story to tell

She is a role model for anyone thinking of joining the Regular Army. In this candid interview, Susan describes some of the personal challenges she has faced and significant achievements she has enjoyed in a very successful career, spanning two decades as a Logistics Supply Specialist within The RLC. The recruiting process timescale and activities are interesting from the point of view that pre-selection was complete in a day and Phase 1 commenced four months later, generally significantly faster that routine recruitment. Her candid views on family and post operational considerations offer food for thought.

Firstly, could you explain your motivation for joining the British Army and your family circumstances?

I’m originally from St. Vincent and the Grenadines; a beautiful island in the Caribbean. Employment is very challenging back home and I always leaned towards serving and wearing a uniform of some kind. I decided to join my island’s police service and completed all the preselection process. As an interim, I was working as a hairdresser, and I remember the day I came home from work when my mother told me that she had heard on the radio that the British Army was sending a small recruiting team to the island to select potential recruits for the Regular Army. I think the backdrop to this was the challenging recruiting environment on the UK mainland and as a consequence, a recruitment drive was instigated and rolled out across selected Foreign and Commonwealth countries.

The truth is that I was initially hesitant to apply but after some soul searching, I thought, ‘why not?’ I was 22 when I made this decision. The St. Vincent and Grenadine High Commissioner to the UK was a Mr Dougan, a lawyer by profession, and I had to submit the relevant documents to his office prior to the recruiting team arriving on the island. A month later I received a package from the British Army with the details of the process and my reporting time and date at Ottley Hall at the Docks Station. I remember that it was a pretty intense day, from the BARB test (aptitude test) to the physical assessment and everything in between. We were shown a video which outlined all of the trades currently available to recruits and from our BARB test scores we were able to choose what we were interested in. Looking back, The RLC must have been fairly

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 14 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

Q A

convincing with their recruitment strategy as I was drawn towards the Logistic Specialist trade – a decision I’ve not regretted. At the day’s conclusion, all the successful candidates were given a letter informing us that we had passed the initial recruitment stage and detailed the administration for our travel to the UK to commence Phase 1 recruit training. I remember telling my mother of the outcome and she was in tears. She regarded the acceptance letter as an opportunity for betterment.

Leaving home to join the British Army is a significant life event for anyone. What was it like to leave your family in the Caribbean?

It was a very emotional time for everyone but, by comparison to some of my cohort, I’d already experienced some significant life challenges and so I think I had a mature attitude to what was happening. From receiving my initial letter in November 2000, I was reporting for duty in March 2001. For me, this period was a torrid time as I had two young children. My daughter was five and my son was one – so, leaving was a pretty traumatic event for all my family as I decided to leave my children in the care of my mother and siblings. Despite this heartache, I recognised that joining the British Army was a golden opportunity to make something, not only for myself, but for my family. If you’re lucky, you may only be presented with a few life chances, and I recognised this as one of them. There were about 250 of us destined for various cap badges who arrived at Gatwick on the same flight from St. Vincent. I remember being met by a group of non-commissioned officers and from the outset I thought they were very friendly. I would say now that this period of first contact was all very positive and helped build my confidence and shape my attitude for what was to come.

I commenced training at Pirbright one week earlier than our UK counterparts and we used the time to familiarise ourselves with the environment and complete UK administration, such as opening a bank account. I was in an all-female troop with nine recruits from St. Vincent. At the end of Phase 1 training, eight of us completed the training and there are two of us still serving today. I’m proud that I’m still the highest-ranking female in the British Army from St. Vincent and the Grenadines. I enjoyed Phase 1; I was the fittest female in my troop and that gives you a lot of confidence. As a mother, I was, by comparison with the other recruits, a mature woman, so it was natural that I assumed a mentoring role – something that gave me a sense of greater responsibility.

Phase 2 training at Deepcut was not so welcoming and together with the other recruits I had some negative experiences. he environment and atmosphere have been well documented. The training focused on physical fitness but not the mental resilience which should run parallel with it. I was fit, so for much of the time I focused on this, representing the Army at netball and athletics. It’s also worth mentioning that whilst I indirectly witnessed racism in Phase 1 training, Phase 2 was much worse. There was a lot of frustration at Deepcut, fueled by inactivity as recruits waited for their trade courses to commence. I waited two months for my courses, but some individuals were

waiting up to 12 months. Time was filled with what the Army termed ‘concurrent activity,’ fitness in the main but with a fair amount of menial tasks.

You finish your recruit and trade training and you’re posted to your first unit. What was the process for this and what did you experience in your first years?

We were asked which unit we would like to be posted to. I remember the initial recruiting slogans back home, ‘join the Army and see the world.’ This was a major hook for me, and I wanted to experience Germany, but I was also a very keen sportswoman. 6 Regt seemed to be a good fit for both, and I was lucky enough to be given my first choice – a decision I never regretted. I loved 6 Regt and Germany. We were like a little family with a close knit foreign and commonwealth contingent, working and playing in a very positive and supportive environment. I made the most of the opportunities to travel in Germany – what a beautiful place. Because of this, I transitioned very quickly into unit life. I wasn’t fazed by anything, and I immediately threw myself into unit and Corps sports, athletics, boxing, netball and football. I also attended a football referee’s course. With full participation in sport and a very busy exercise programme, I was fully immersed in every aspect of unit life. In February 2003, I deployed on my first operational tour, Operation TELIC 1 to Kuwait and Iraq. I made the decision not to tell my family that I had deployed, and I kept in touch via satellite phone. I think my mother had a suspicion that something had changed but I didn’t confirm I’d deployed until I returned to Germany in June 2003. Overall, the deployment was a very positive experience for me, and I learned a lot about my trade and people in general. At the end of the tour, I was selected for promotion to Lance Corporal.

With some operational experience under your belt, where did you go from there?

After TELIC 1, I was seconded to the Corps recruiting team for six months at Abingdon and we travelled to various parts of the UK to undertake recruiting activities. I returned to Germany (Bielefeld) and completed my promotion certificate. I suppose at this stage I was ahead of the standard promotion model, at least for the first two rungs of the ladder. I did hit a promotion plateau at Corporal – something I’m still a little confused over. If anything, this shows that even if you hit a bump in the road, it’s not necessarily the end – you just must believe in yourself and keep going. I moved to 12 Logistic Support Regt and deployed back to Iraq on TELIC 11 in 2006. This was a demanding tour and completely different to 2003; I was frequently out on the ground and the situation with regards to threat level came as an unpleasant surprise to all ranks. After this tour, I experienced a British Army Training Unit Suffield winter repair exercise in Canada in 2009 – something that honed my trade knowledge to another level. In 2010 I deployed to Kenya for six months and at the end of 2010 I was posted to 9 Regt. On my return from Christmas leave in 2011 I was deployed on HERRICK 14 to Afghanistan between January and October where I was awarded a Joint Force Commander’s Commendation for my work in the

RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 15

Q A Q A Q

A

Theatre Logistic Headquarters. I found the tour different to TELIC. I was routinely working with commissioned officers, and I really enjoyed the work environment. After HERRICK I4 was posted to 1 6 Medical Regiment in Colchester as a sergeant. I have always acted as a mentor and in 16 Regt I undertook some significant mentoring activities. I was posted back to 9 Regt as a Staff Sergeant but was promoted to WO2 and assigned to a Sergeant Major post – the first time I had stepped out of trade, which, looking back, was good for me. There had been some challenges with the squadron I was assigned to; some directly relating to foreign and commonwealth soldiers who made up over 90% of the squadron. I also got married in 2018, to a Canadian who lives in Montreal.

Anyway, I enjoyed the experience in 9 Regt and was then posted again in 2019 to Colchester to 8 Field Company REME and eventually ended up as the Regimental Quartermaster Technical. I was also chosen to be the unit Army Multi-Cultural Advisor as the unit had a large ethnically diverse population. I took the role very seriously and won two awards; the 2020 civilian, ‘We are the City Rising Star Award’ and later that year, I won an RLC Foundation Award in the mentoring category. I was promoted in 2021 to WO1 and found myself in London but before coming here I deployed to Macedonia for three months. One of the unusual tasks I have been chosen to complete here is to give a reading for the National Army Museum on Black History month – something I’ll never forget. In truth, I never wanted to be posted to London but after conducting a lot of face-to-face unit visits I’ve found it a very positive experience and I think unit representatives appreciate what we are trying to do for them. As with most jobs, how we perform is based largely on personal contact and developing a trusted working relationship. These jobs can often throw you a curve ball and in my first two weeks in post, I found myself representing the MOD, giving technical evidence in Crown Court for a civil/military case. Never a dull moment!

You clearly created some opportunities for yourself and made the most of what your Corps offered. What about your immediate family? Well, I’m not going to say that living with my original decision to leave my children with my mother and siblings was easy. This was always a long-term plan for betterment, for all of us. My first leave back to St. Vincent was 2004 and I stayed for a month, and I went back again in 2007 and 2010,

leaving after the first two visits wasn’t easy. A lot of water went under the bridge but in 2008 my children joined me in the UK (Abingdon), eight years after I joined the Army. Again, this was another upheaval for my mother and my children who had grown very close. I explained to them why I did it and you know, they get it. They understand the logic. The payback has come in different ways. My daughter is now a nurse, and my son has just completed his undergraduate studies in psychology, and he has aspirations to join the British Army. It was a juggling act when my children were younger, and we were living in the UK. I have five sisters and they all would look after my children if I was away for any significant length of time. My mother came over in 2009 and 2010 and experienced the setup. When she first came in 2009, she saw me in my uniform and was tearful, when I asked her what’s wrong, she said that she was so proud of what I’d achieved. The truth however is that this whole enterprise with the British Army has been a family affair, we are close, and it has been a team effort to make it work. The unit support mechanism has also helped, and I have appreciated the assistance they have offered but my family and our Christian faith have been my fallback when I needed support.

Looking back at your varied experiences and with a wealth of general and technical knowledge, what is your view of the operations that you deployed on?

To be honest, my first deployment to Kuwait/ Iraq was at such a low level that I didn’t give it much thought to the why but more to the how… Such is a soldier’s lot I suppose. We were briefed that we were there because of the threat of Saddam’s WMD arsenal and his non-compliance with UN resolutions. I think we all generally accepted that rationale. With the second tour, I witnessed a broader set of challenges. I don’t think it’s for me to say if we were right or wrong to be there, but the subsequent enquiry (Chilcott Inquiry) seems to question the original rationale. After tumbling a dictatorship, I ask myself was it worth it and what lessons have been learnt? I have similar thoughts when I consider Afghanistan. I initially thought that intervention in Afghanistan after 9/11 was necessary, but my view is now more nuanced. When I consider what governance Afghanistan is now subjected to, and in particular the lack of opportunities for women, I wonder if we have made any lasting difference to the country. I still ask myself, ‘was it worth it’? Q A Q A

8 RLC FOUNDATION INTERVIEW 16 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

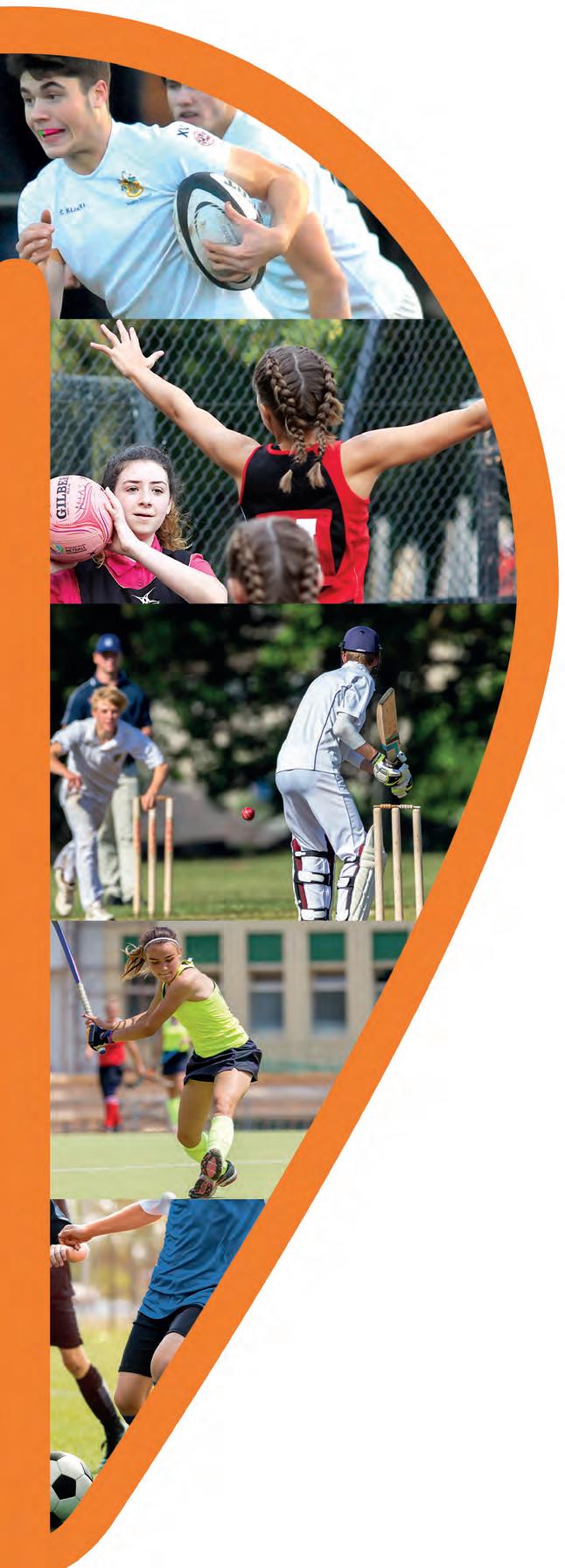

The UK’s trusted provider of Military Sports OSVs

Bolster team spirit and connections through challenging fixtures, elite training sessions, and OSV standards-aligned community engagement projects and excursions on an Edwin Doran sports tour.

As the only operator of sports tours that aligns with the British Armed Forces’ OSV tour purpose standards and proud sponsors of the Royal Logistics Corp, we have a complete understanding of the military objectives and requirements for launching an overseas sports tour.

With fifty years of experience delivering worldclass sports tours and dedicated staff who have served in the Armed Forces, your next OSV is going to be special. Get in touch with us at military@edwindoran.com to start planning it.

Cape Town stole our hearts. From arrival through to departure, the tour truly exceeded all of our expectations. Every activity and every interaction was excellent, the team went above and beyond to be flexible and accommodate us.

Army Medical Services – Hockey Tour to South Africa

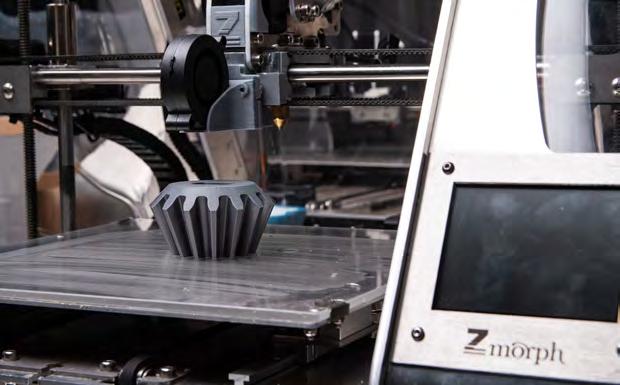

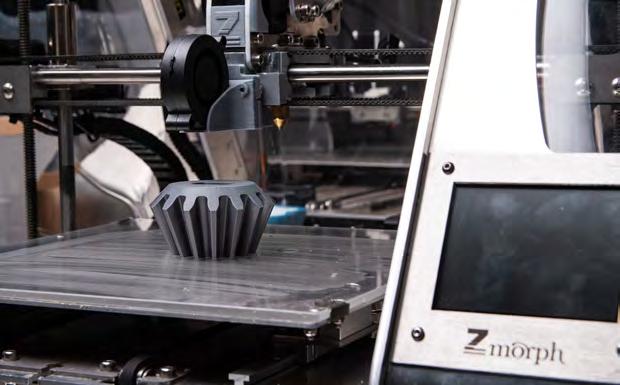

3D printing can reduce Defence’s logistic footprint and optimise its supply chains

It has been widely reported, that within weeks of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, 3D printing tech companies in Eastern Europe were supplying Ukraine with hundreds of plastics and polymer 3D printers which have been used on the battlefield ever since to make everything from FPV drone airframes to tourniquets and prosthetic limbs. Today 3D printing (additive manufacturing to give it its correct title) technology is having a profound effect on the success or failure of combat operations in Ukraine. While still in its infancy, the use of 3D printing technology by the UK’s armed forces is now rapidly gaining momentum.

By Mr Peter Shakespeare

Having the ability to manufacture components or complete items, in, or close to, the battlespace, overcomes a multitude of logistical challenges, especially in alleviating the pressure on an army’s supply chain to keep its fighting units supplied with weapons and combat supplies. But within the home base, serious issues have developed over time within the military supply chains responsible for keeping military hardware maintained and operational.

Most of today’s military platforms have been in service for decades. Given the age of the equipment inventory, many of their component parts and ancillaries are obsolete and new ones take months to manufacture and are very expensive. Speaking at the Defence Security and Equipment International event, Lieutenant General Richard Wardlaw, the British Chief of Defence Logistics and Support, summarised the challenges, declaring that: “The biggest single threat to defence supply is obsolescence.”

The use of additive manufacturing (AdM) to make replacement legacy parts has been seen as the solution by the US, Australian, Dutch and French militaries for some time and now the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD) is developing and adopting the technology.

Alex Champion has a degree in motorsport engineering and spent his early career manufacturing parts for Formula 1. He is also an Army Reservist, serving as a Second Lieutenant with 165 Port & Maritime Regiment RLC. In 2018, while working

for a 3D printing company, he quickly familiarised himself with the technology. In October 2019, whilst attending an engineering exhibition at the Millbrook proving ground, he was introduced to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers’ (REME) staff officer responsible for the Army’s project to expand its manufacturing and engineering capabilities –Lieutenant Colonel Dan Anders-Brown. Colonel Anders-Brown subsequently asked Champion to give a talk on AdM to several senior army officers.

After delivering a successful briefing, he was offered 44 days a year working as a Reservist at Army HQ. He was tasked with designing four small deployable factories containing laser scanners and 3D printers, each capable of being transported on an Army Support Vehicle. These would be trialled in remote locations, helping to inform the Army’s future engineering, manufacturing and logistics policy and doctrine. Champion was also invited to present about the planned trials at the Shrivenham Defence Academy, followed by another talk at a Tri-service conference. Champion outlines the opportunities:

“The Army had been looking to adopt technologies such as 3D printing in order to manufacture urgent parts. This will help to reduce the logistic burden and save money in developing or updating equipment. We initially focused on using the technology to produce temporary and non-safety critical 'get me home' repairs. At the other end of the spectrum, the American Department of Defence has invested heavily in this

8 RLCF SPECIAL 18 | THE REVIEW 2024 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION

8 An Australian soldier-installing a SPEE3D printed road-wheel bearing on a M113 APC

technology and is now benefiting from being able to 3D print metal components, for main battle tanks and this one capability alone has saved months of repair time and millions of dollars. UK Defence is now developing the capability to manufacturer the full range of safety and non-safety critical components for its assets.”

The MOD’s programme to invest in the strategic use of AdM, goes by the name of Project TAMPA. One of the project’s aims is to incentivise the defence manufacturing industrial base to accelerate and drive up the levels of innovation that it applies to strategic supply chain management. Today, Champion is the AdM lead at the MOD’s Defence Equipment Support organisation (DE&S), responsible for the project.

In September 2022, DE&S’s Commercial Future Capabilities Group published a notice to existing defence contractors that supply NATO Stock Number (NSN) parts to the MOD inviting expressions of interest for the £5 million three-year project, which would use AdM technology to supply obsolete components for weapons systems and maritime, air and land assets.

In April 2023 DE&S announced it had set up the first framework under Project TAMPA by awarding industry contracts to - AMFG, Babcock International, NP Aerospace, RBSL and Thales. Project TAMPA is initially looking into what limitations, if any, of adopting AdM will prevent DE&S and its industry partners, from using the technology to best effect.

The first phase of the project is to produce and fit 11 non-safety critical 3D printed metallic NSN parts onto in-service platforms. This will be followed by safety critical metallic NSN parts produced in an industrial base, certified by the producer (OEM or under licence). The next phase is to manufacture non-safety critical metallic (or polymer) NSN parts, produced in a location remote from the industrial base, certified by the producer; then a safety critical metallic (or polymer) NSN part, produced in a location remote from the industrial base. The final phase will be to produce non-safety critical metallic (or polymer) NSN parts, produced in a location remote from the industrial base, certified by the producer and where access to design rights are required.

While several of the MOD industry partners involved in Project TAMPA are OEMs, Babcock International is in a unique position that while it is an OEM, it also provides third party through-life technical and engineering support to the MOD and delivers engineering support to land defence and air base operations, specialist training and asset

management, equipment supply and maintenance.

Jonathan Morley is Babcock’s Manufacturing and MRO Lead (Technology) and outlined the initiative:

“There is no doubt that the defence supply chain needs to be better than it is and before Project TAMPA started Babcock was working on programmes to look at how we could use technologies, such as AdM to augment and complement our defence supply chain management activities across land, sea and air. There are a lot of legacy assets within the defence equipment portfolio and the severe challenges of obsolescence is something we face every day. These legacy platforms are low volume which makes supply chain provision even more difficult. In some cases, platforms, especially submarines, are unique and there have been cases where there are no drawings for a part, so they have to be re-engineered. AdM provides the solution. These new technologies not only have the potential to address these issues, they also help us improve our productivity and ability to support our customer and reduce downtime.”

Separate to Project TAMPA, Alex Champion says frontline commands in the Army, Navy and Royal Air Force have now procured their own AdM machines to support their own programmes to enhance manufacturing capability to support operations. The equipment is deployable and suitable to fabricate and expedient in-situ repairs and explains why the MOD is looking to establish regional hubs with this capability.

In November 2022, Renishaw supplied a RenAM 500Q Flex metal AdM machine to RAF Wittering help improve its component manufacturing capabilities. The Station is using the system, along with other 3D printing and scanning equipment, to produce custombuilt structural aircraft components for rapid repairs. Its arrival marks the RAF’s first steps into advanced component manufacturing. In March 2023, DE&S purchased a SPEE3D Coldspray printer and signed a two-year contract to work with the Australian company. The 3D print technologies being utilised include Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) and SPEE3D Coldspray additive manufacturing.

SPEE3D’s Coldspray printer uses supersonic

RLCF SPECIAL 8 THE ROYAL LOGISTIC CORPS FOUNDATION THE REVIEW 2024 | 19

8 As part of TAMPA, Babcock 3D printed and fitted AFV periscope components to refurbished vehicles

8 Renishaw AdM technology is being used by the RAF

deposition. A rocket nozzle accelerates air up to four times the speed of sound. Injected powders are deposited onto a substrate that is attached to a six-axis robotic arm. In this process, the sheer kinetic energy of the particles causes the powders to bind together to form a high-density part with dimensions up to 1000 x 700mm. Materials currently available are Aluminium, Aluminium Bronze, Stainless Steel, and Copper, with others in development. The printer and associated equipment will fit inside a 20-foot ISO container so can be transported and deployed using a military load carrier.

PBF methods use either a laser or electron beam to melt or sinter material powder together. The process can create highly complicated geometric shapes from a range of metals and polymer powders; although polymers cannot be melted so use the sintering process.

The technology lends itself to small complex components and due to the accuracy of the manufacturing process they only require basic finishing, such as threading fixing holes.

WAAM is the oldest 3D printing technology and is basically a MIG welder mounted on a robotic arm. The workpiece is formed on a rotary table and the machine builds up the part from weld, controlled by CAD/CAM software. WAAM has a resolution of approximately 1mm and a deposition rate of between one and 10kg per hour. This is a technology that Babcock uses, and Jonathon Morley says it has the capability to make a 4-metre diameter ships propeller or other large, high strength, components.

Coldspray and WAAM effectively make castings that require machining and finishing. For decades the REME and Royal Engineers have deployed field

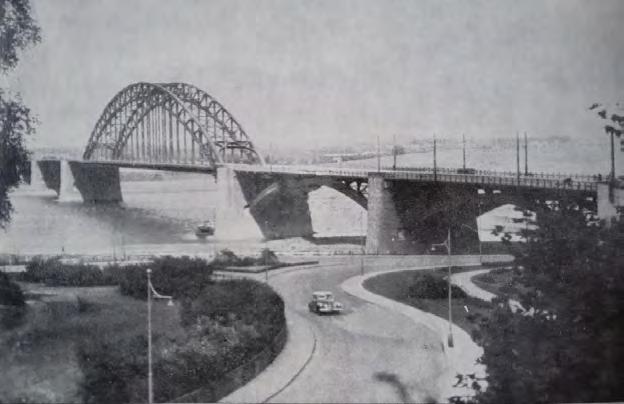

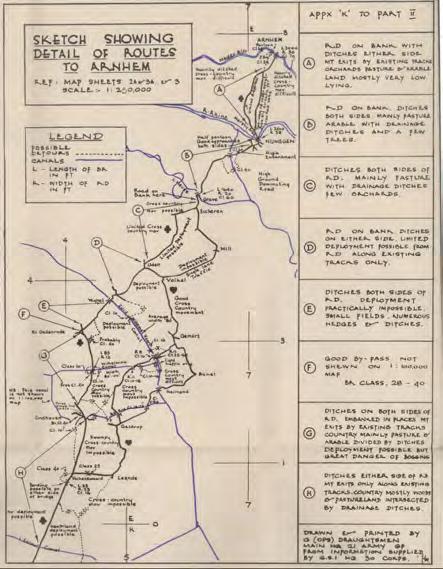

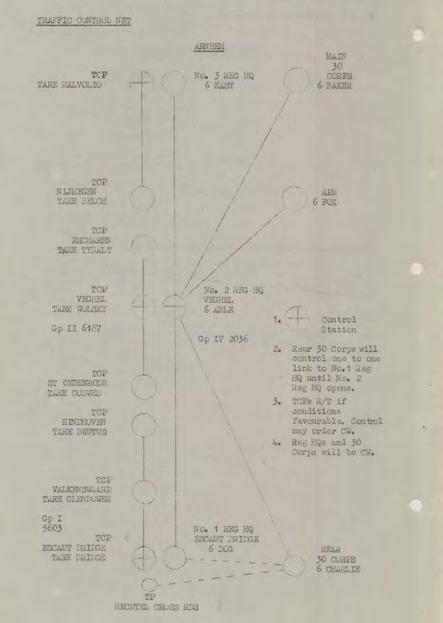

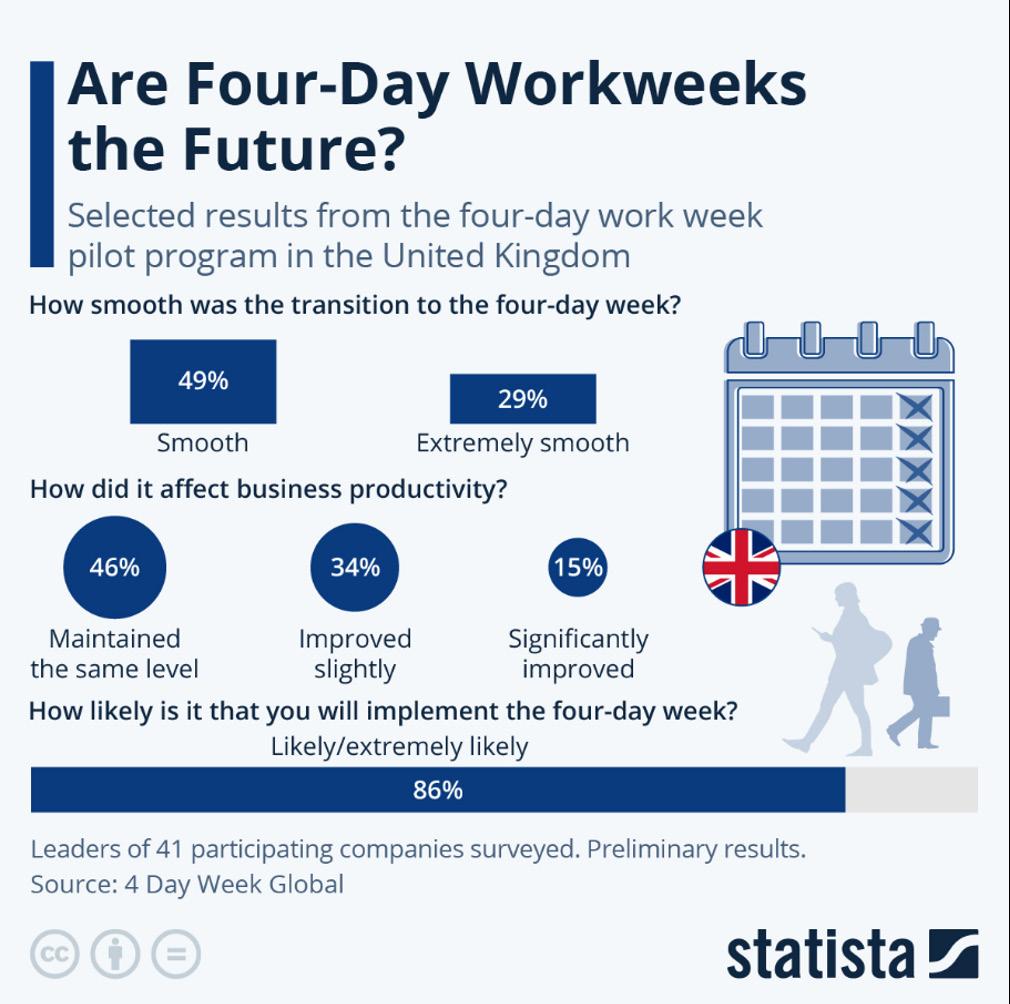

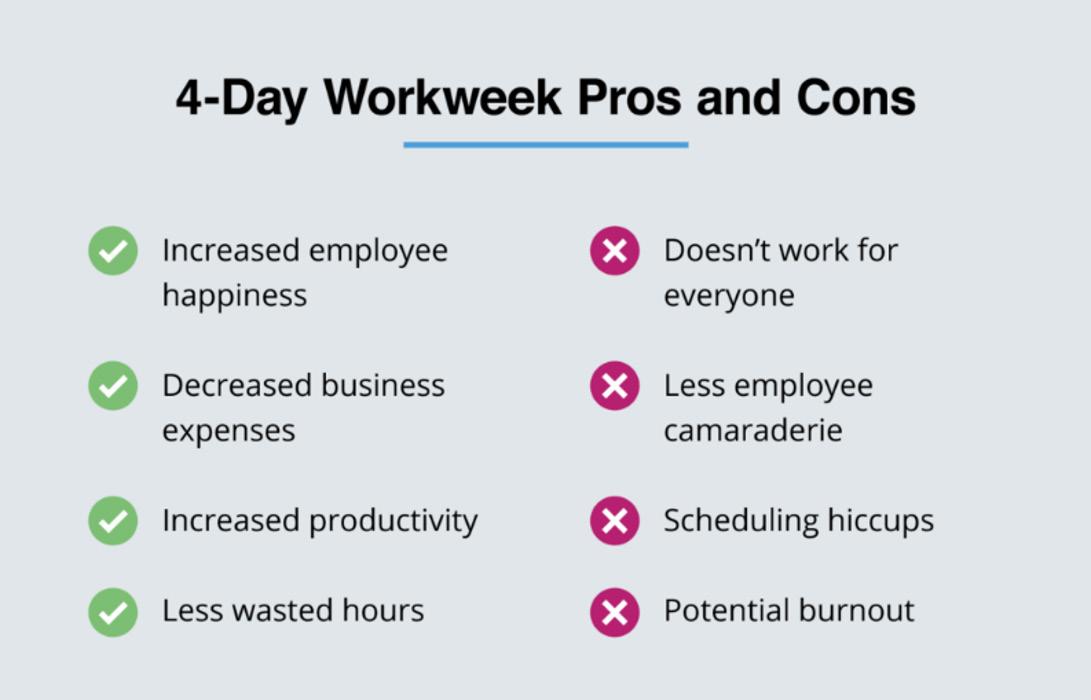

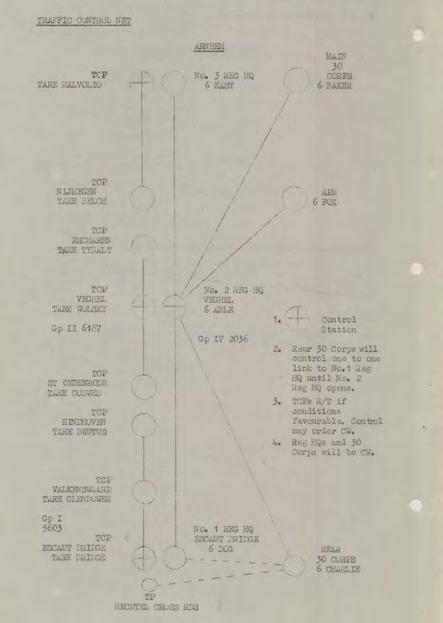

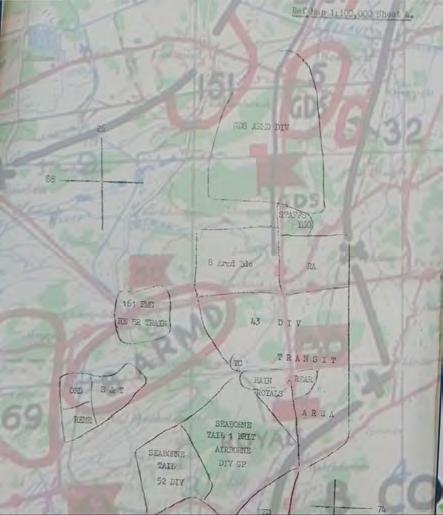

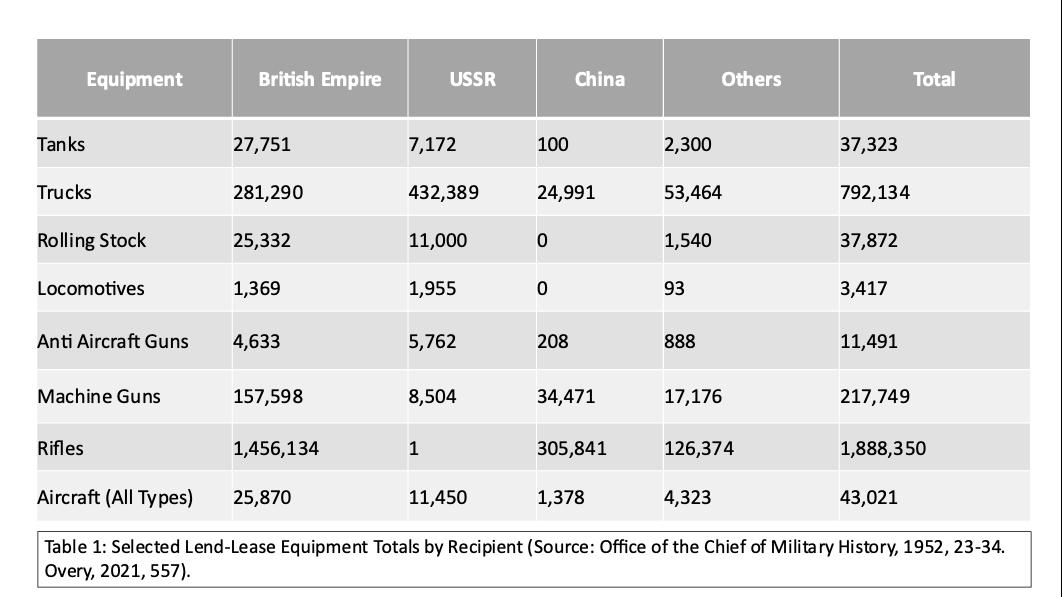

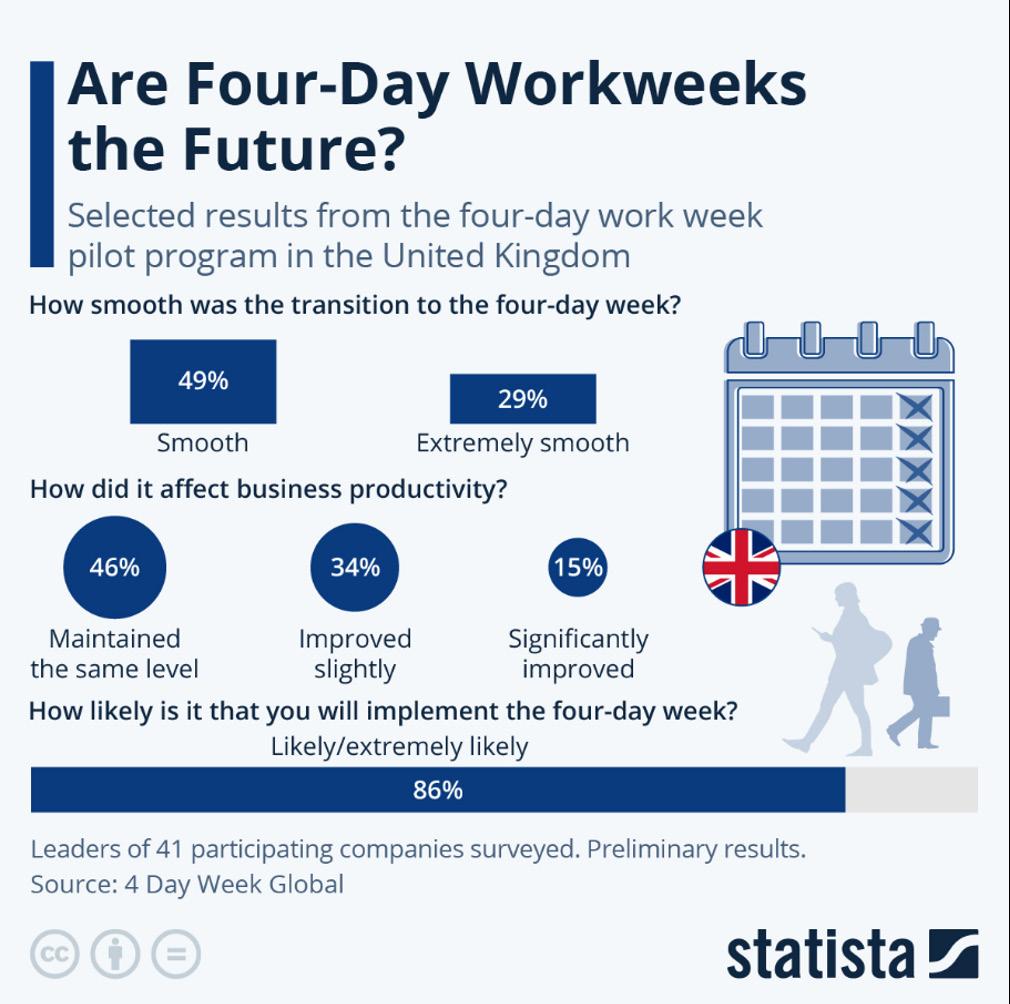

workshops equipped with machine tools, such as lathes and milling machines, which can be used in conjunction with deployable Coldspray and WAAM 3D printers to offer significant reductions in the spares inventory.