Hofstra University

Model United Nations Conference 2025

Specialized Committee

Jacob Bass, Co-Chair

Rob Cesareo, Co-Chair

Dear Participants of the Hofstra University Model United Nations Conference,

My name is Jacob Bass and I am a junior History and Social Studies Education major, as well as one of the Co-Chairs of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) committee for this year’s HUMUNC conference. It will be great to meet all of you soon!

I have been involved with Model UN ever since ninth grade. Model United Nations is a concept that has always fascinated me, combining my love for global studies and affairs with a great way to practice speech and debate in a unique way. Now in college, I had my first experience with the Hofstra Model United Nations Conference last year as a backroom member of a crisis committee, and throughout my experience over those few days, I was able to see just how this conference can be eventful, fun, productive, and educational. I have come back to lead a committee at HUMUNC 2025 for you all.

For a long time, I have loved history; it is my favorite subject in school, with math close behind. I have found my love for it growing in various ways over the years, and it has become obvious to me that becoming a teacher is something I truly desire to do. I want to make learning history more interesting and not the stereotypical “boring” subject in school. We are living history every day — even if we are not thinking about it and the study of global affairs can be our way of studying history as it is happening. In this committee, you will be doing just that, involving yourself and making history in the present!

But be aware that this will not be an easy task to complete, we are looking at the case of the Sudanese Civil War, a conflict with many sides in a highly contested region of the world. You will need to stay on your toes, choosing your allies carefully and making the decision: will you be a follower, or will you step up and be the leader who can answer the crucial question: how, as NATO, are we going to approach this?

Stay excited,

Jacob Bass Co-chair NATO committee

Greetings,

It is my honor to welcome you all to the 2025 Hofstra Model United Nations Conference! I am very excited to be hosting our conference here at Hofstra and creating the most immersive experience possible.

My name is Robert Cesareo, and I am currently a senior here at Hofstra and I am studying TV production at the Lawrence Herbert School of Communication. In addition to my major, I completed a minor in political science, which stems from a passion for MUN. My Model UN career has spanned nearly nine years at this point, going back to my freshman year of high school. In that time, I have taken part in multiple local conferences, as well as national conferences spanning from New York to Vancouver, Canada. My time in college has allowed me to chair multiple committees and grow my experience at the front of a conference room. I even served as president of the Model United Nations club on campus, so you can say that I have taken part in almost every aspect of what is involved with MUN.

On a more personal level, I am a diehard baseball fan. I have no issues watching the best team in baseball, the New York Mets, play all 162 games each year. Regardless of how much the outcome of a single game can determine my mood, I live and breathe the orange and blue. When I am not watching baseball, you can usually find me in the engineering department of the communications school, where I work primarily with our school's TV network, H.E.A.T., to produce student-led shows and events. Hands down the best of these is Thursday Night Live, our very own student-run spoof of Saturday Night Live Though the hours are long, I enjoy working behind the scenes of TV production and see this as the best path for my future.

In the end, my focus is to ensure that all of you have an exciting time at HUMUNC 2025. The work put into this conference by my fellow chairs, staff, and secretariat is truly something special. As your chair, I am looking forward to meeting all of you and getting to work during this one weekend in March.

Sincerely,

Robert Cesareo Co-Chair NATO

Introduction to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is an intergovernmental organization that functions as a military alliance among nations in the Northern Hemisphere. It was founded on April 4, 19491 by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Portugal.2 As of 2024, there are thirty-two members, with the United States and Canada being the only non-European members. It was founded as a collective security organization following the Second World War as a way to combat the rising influence of the Soviet Union and its bloc of allies in Eastern Europe, known as the Warsaw Pact. With collective security, an attack on one is an attack on all, indicating that the motives behind the alliance lie in efforts to protect its members in the case of military action.

While there is no longer a threat of the Soviet Union today, there still exist many countries that challenge the democratic ideals promoted by NATO member states. Major countries like Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran threaten global security, and around the world, there is a continuum of minor conflicts that continue to rage on. With the influence of these countries rising more and more in recent years, NATO has stuck together beyond the fall of the Warsaw Pact and into the modern day, pledging to defend democratic ideals and cooperate on security issues.3

This committee will simulate NATO’s North Atlantic Council, the principal decisionmaking body of NATO member states. Together, as representatives from countries in NATO, you will discuss how the brutal civil war plaguing the African country of Sudan intersects with the interests of NATO members and how the alliance might play a constructive role in line with its ideals. You will be representing a NATO member state in the North Atlantic Council, where

member states are represented by their heads of government, ministers of state, ministers of defense, or various other positions.4

Topic 1: 2023 Sudanese Civil War

Overview of the Sudanese Civil War

Piles of bodies in “makeshift cemeteries” visible from space. An estimated 150,000 Sudanese people killed. A destroyed capital city. A civil war has been leveling Sudan since April 2023, and some feel it may be one of the worst humanitarian crises of the modern day, a “geopolitical timebomb”. While the Middle East and Russia continue to fund the warring factions, the West stands idle in the face of such a horrible tragedy. Under the strict command of Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) face off against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)5 with their head officer Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, generally referred to as “Hemedti”.6 The fighting is concentrated in the southwestern region of Darfur and the capital city of Khartoum, but eventually reaches cities across the country.

1: Locations of conflict in Sudanese Civil war and displaced people (April 2023)7

As a result of the conflict, many people have been displaced outside of the country and into bordering regions, forcing them to find ways to survive while being forced to flee their homes8 and stretching the suffering beyond the places where the fighting initially started. Additionally, there have been operations undertaken by countries such as India, France, the United States, Saudi Arabia9 and Germany10 to evacuate their nationals living and working in

Sudan. While both the RAF and SAF have made gains at different parts of the war, negotiations have been nothing more than futile in ending the conflict, which rages on to this day.

Modern History of Sudan and the Lead-Up to the 2023 Civil War

Since independence, Sudan has experienced civil wars in 1955 and 1983, the latter ending in the separation of South Sudan as an independent nation in 2011. Approximately two million people had died by the end of the second civil war and the country was in a very precarious situation, socially, politically, and economically.11 In 2003, Darfur experienced a cruel war as a result of lasting racial and ethnic tensions. The president of Sudan, Omar alBashir, promised to fight against the anti-government sentiments, however, the end of the 2003 war would end with over 300,000 people dead and al-Bashir charged with war crimes.12

In 2013, al-Bashir created the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) from the Janjaweed, a militia that had once terrorized Darfur, as an “independent security force” to terrorize illegal migrants to Sudan.13 In December 2018, however, the RSF joined the SAF in a military junta against alBashir’s government after widespread protests over joblessness and corruption. Protests continued under military rule, culminating in the June 2019 “Khartoum Massacre” where the RSF was accused of killing 128 protesters. The African Union (AU) and Ethiopia helped negotiate a military-civilian transitional government in August 2019 to create stability and reduce tensions with the Sudanese people.14

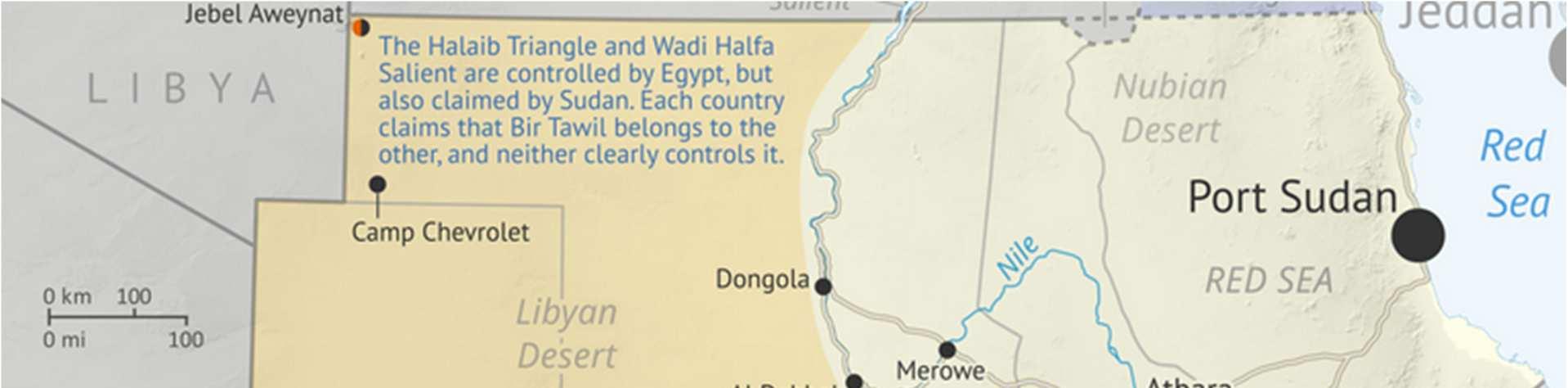

However, the continued economic weakness led to protests against the transitional government until “[al-Burhan] and Hemedti deposed the civilian government in an October 2021 coup.”15 By April 2023, tensions rose between the RSF and SAF when Hemdti tried to ally

himself with the Sudanese populace and broke with al-Burhan. Clashes between the RSF and SAF in Khartoum would create grounds for a full-on civil war.16

Sudanese Civil War in 2023

Fighting between the RSF and SAF immediately damaged Sudan’s infrastructure, as networks of travel, broadcasting, and communications broke down due to the fighting17. Hemedti ordered forces to try and find al-Burhan to kill him, and when they failed, he and his forces were weakened and isolated in Khartoum.18 Following “weeks of talks” led by the United States and Saudi Arabia, a treaty signed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in May emphasized efforts to protect civilians, but did not create a ceasefire.19 Heavy fighting, especially in Khartoum, continued and al-Burhan would eventually be evacuated by the SAF to Port Sudan in the east.20 As the fighting continued, he even went to UN headquarters in New York to urge the international community to “designate the [RSF] as a terrorist group.”21

In June 2023, the fighting spread to the capitals of Northern Darfur and Southern Darfur. The SPLM-N a “rebel group led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, which controls parts of South Kordofan state, of breaking a long-standing ceasefire agreement and attacking” the SAF in Kadugli, the state capital.22 The discovery of a mass grave, likely with many people of the Masalit in West Darfur, was attributed to the RSF, which denied involvement.23 By October 2023, the RSF captured control over Nyala, the capital of South Darfur.24 To bolster the SAF’s ability to combat the RSF, the army began arming civilians to aid in the war effort, as many young men are “motivated to pick up weapons due to the risk that the RSF could attack their cities, loot their belongings, and subject women to sexual violence.”25

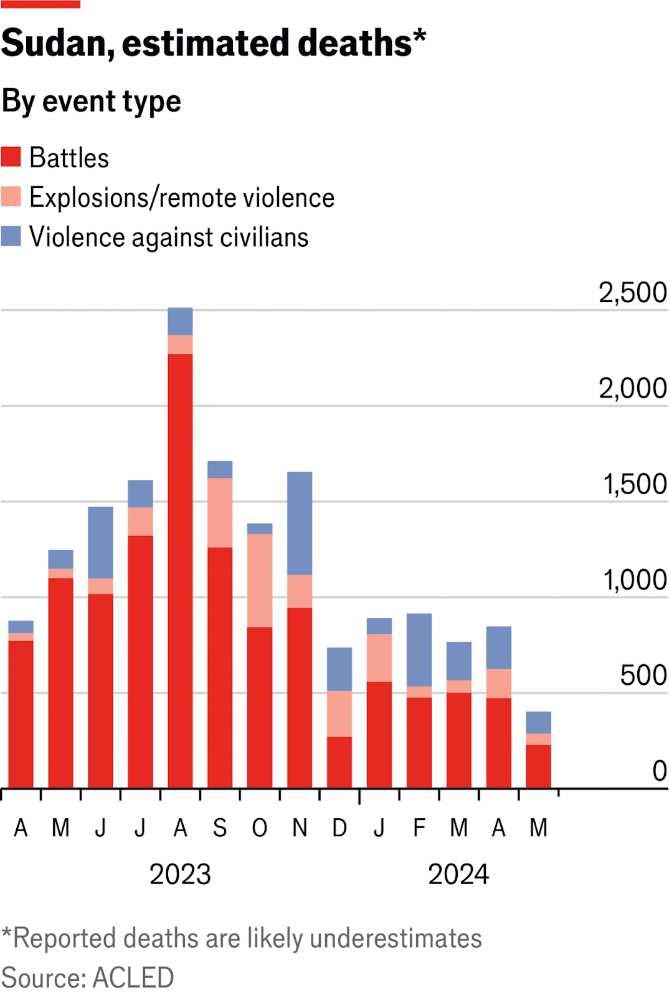

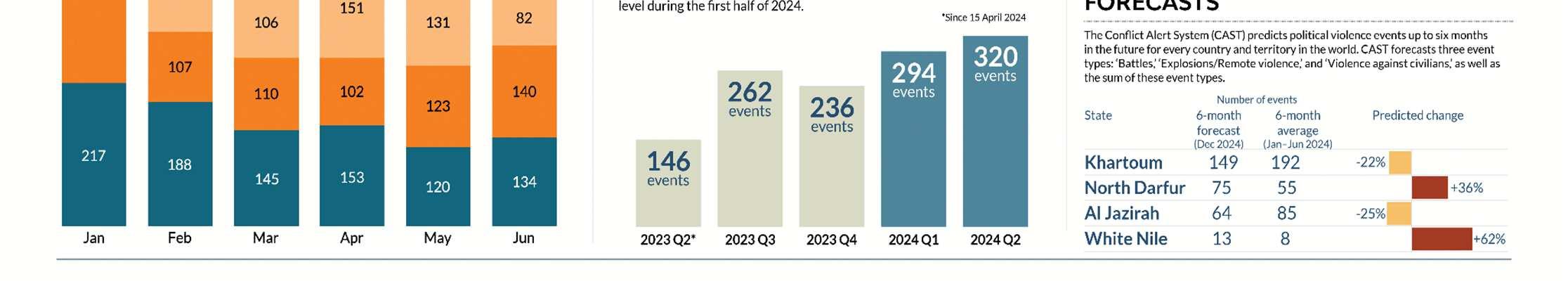

Figure 2: Deaths in the Sudanese Civil War over time26

Sudanese Civil War in 2024

Efforts by the international community to end the conflict included talks initiated by the East African Standby Force and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), organizations that include Sudan and its east African neighbors.27 Yet, just before the December 2023 ceasefire negotiations were set to begin, Hemedti canceled, instead traveling to neighboring Uganda and Ethiopia to build support and attempt to build his credibility as the “true” leader of Sudan.28

Efforts in January 2024 by IGAD to restart peace talks were rejected by al-Burhan,who reinforced the SAF’s plan to continue fighting the RSF, and rejected IGAD’s authority to make peace.29 As the one-year anniversary of the civil war arrived in April 2024 with no end in sight,

the “fighting has killed tens of thousands of people, forced millions to flee, and devastated the nation’s economy, creating the world’s largest humanitarian disaster.”30 In June 2024, fighting spread to El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, which “hosts over a million civilians, many of whom are already displaced by the conflict and teetering on the edge of survival”.31

As of November 2024, the civil war continues as both sides have ruled out negotiations which could solve the war as famine conditions grow and over ten million Sudanese have been displaced. Foreign involvement in the civil war cannot be ignored, consisting of direct aid to the warring factions, and other nations taking the stance of attempting to find ways to make peace, however, as of the present day that has not worked out in the favor of any one nation. Nathaniel Raymond, Executive director at the Yale School of Public Health’s Humanitarian Research Lab observed that “Both sides have continued to violate the laws of armed conflict in multiple ways, with the support of outside actors allegedly ranging from the UAE to Russia to Iran to Egypt and others”.32

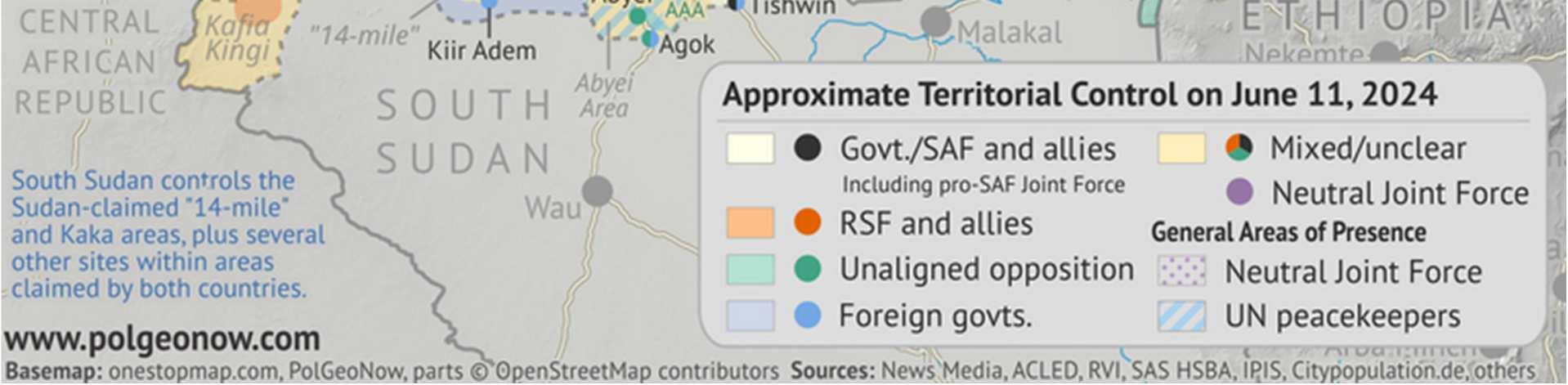

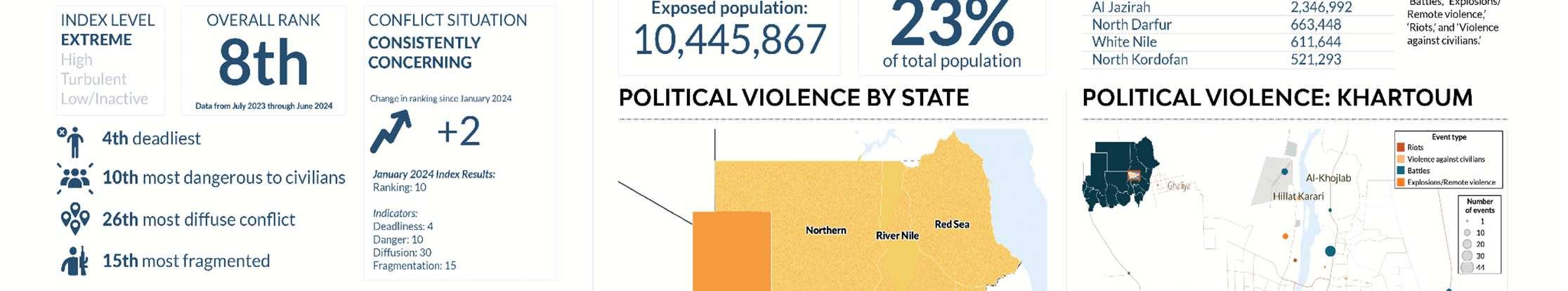

202433

Despite the complex nature of the Sudanese Civil War which would make it difficult for the international community to resolve, experts have warned that the conflict demands greater attention. Tom Perriello, the U.S. Special Envoy for Sudan, testified to the Senate Foreign

Relations Committee in February 2024 underscored the importance of increased awareness and support from the media and urged for sustained humanitarian aid to alleviate the suffering of millions of Sudanese people.”34 An estimated total of nearly 150,000 people have been killed as a result of the fighting,35 over ten million have been displaced, and over 25.6 million were at risk for “high levels of acute food insecurity…between June and September 2024”.36 Healthcare facilities have not been spared from the fighting between SAF and RSF.

During the fighting in Khartoum in April 2023, people were too afraid to even step out of their home in fear of getting caught in the crossfire, and for those who were injured and did seek medical help, hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, understaffed, and medical staff reported feeling overworked.37 The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that twenty-six healthcare facilities were damaged during this period.38

While the Treaty of Jeddah began to make strides in protecting civilian sectors, the United Nations reported that there was still a shortage of basic goods like food, water, gas, and medicine,39 and that even remittances from overseas migrants toward families back in Sudan were cut due to Western Union closing operations in Sudan until “further notice”.40

In one case, the World Food Programme (WFP) reported in May 2023 that over $13 million in food aid was “looted”.41 As of February 2024, with more than five million Sudanese facing “emergency levels of hunger”, delivery of food aid was reported to be hampered by “[security] threats and roadblocks [that] have made the work of humanitarian agencies nearly impossible.42

4: Crisis diagram of Sudan in July 202443

Bloc Positions (NATO)

While NATO has not taken any official action against any of the factions present within the Sudanese Civil War, member countries on their own have made statements and taken action in their own ways. This committee will take a novel approach by applying NATO’s crisis response structure to explore potential actions that can be taken to represent NATO’s values of security and democratic ideals in the case of ending Sudan’s civil war.

The Wagner Group

Militant organizations like the Wagner Group have openly supported the RSF, and various African and Middle Eastern countries have engaged in levels of support as well. The Wagner Group is a Russian militant group operating alongside the Kremlin in places such as Ukraine, Syria, and more recently, African conflicts in Central African Republic, Mali, and Libya. It is a complex organization involving militias and businesses that are backed by Russian resources and intelligence, and in the context of Africa, “[the] Wagner Group got involved in Africa for its own reasons, [such as] private money making. But more recently, the Kremlin has found this as a useful adjunct to what it’s trying to do diplomatically.” In Sudan, Wagner had been operating alongside Sudanese troops and doing the dirty work of al-Bashir in exchange for money, and their boost of the RAF has given them leverage in the recent conflicts.44

The threat of Wagner has become clear as it serves as a proxy for Russia and its actions threaten global peace and security. While NATO members have sought, unilaterally and through regional diplomacy, to end the conflict, Wagner’s activities allow Russia to maintain allies by lending fighters, training, and supplies to those interested in continuing the conflict. If NATO or its allies encounter Wagner forces in Sudan, it may escalate tensions closest to any direct conflict between NATO and Russia.

The African Union

Another important group to take note of in the context of Sudan is the African Union (AU). While Sudan was an AU member at one point, its membership was suspended in June

2019 due to the ongoing political instability troubling the nation.45 It is important to note that an earlier conflict in Sudan created an opportunity for NATO and the African Union to cooperate, based on the shared principles of international security. This took place in 2005 during the AU’s Darfur peacekeeping operation. Following a direct request from the AU, NATO supported the AU by providing training for AU forces conducting peacekeeping operations in Darfur, airlifting forces to Sudan, reviewing operations for future training, and planning operations.46 NATO troops were not directly deployed on the ground in Darfur, however, but the operation was an opportunity for the AU and NATO to explore future cooperation on security issues.

After the Darfur operation, coordination from NATO was centralized at the headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Countries like Germany and Italy allowed AU officials to train in their military schools in order to be more aware of the way in which NATO operates.47

Following NATO’s support to the AU mission in Sudan in 2005, the AU made a general request in January 2007 to all partners, including NATO, for financial and logistical support to its mission in Somalia (AMISOM). It later made a specific request to NATO in May 2007, requesting strategic airlift support for AU member states willing to deploy in Somalia under AMISOM. In June 2007, the North Atlantic Council (NAC) agreed, in principle, to support this request and NATO’s support was initially authorised until August 2007. Strategic sealift support was requested at a later stage and agreed in principle by the NAC in September 2009.48

Interests of Individual NATO members

While there haven’t been substantial interactions between NATO and the AU for any major movements in the recent civil war in Sudan, both organizations and their member states have still been active during the conflict. The United States has been involved in the crisis ever since it began, working alongside Saudi Arabia on the Treaty of Jeddah. Critics of the U.S. role

blame the Trump administration for not intervening in order to achieve Sudan’s participation the Abraham Accords. Critics also reserve blame for the Biden administration for negligence by not objecting to military leaders like al-Burhan and Hemedti remaining on the transitional governing committee following the overthrow of al-Bashir in 2019. As the military leaders clashed, the U.S. had limited options and few in Sudan to work with to support in a stable government.49

Although the U.S. has not been an active leader on preventing the civil war, “Washington also sees that Sudan holds great geopolitical, economic, and strategic importance that makes it the subject of regional and international ambitions and greed.”50 Specifically, the U.S. sees Sudan as a place to check Russia and China’s ambitions in Africa, where those countries look to exploit its mineral wealth and strategic position. The U.S. also fears that if the civil war continues, regional alliances will shift, causing its important regional allies like Saudi Arabia and Egypt (more likely to support Burhan) to choose sides in opposition to other U.S. allies like United Arab Emirates and Ethiopia (more likely to support Hemedti). Finally, the U.S. is concerned about the ongoing humanitarian crisis and protecting its ability to gather intelligence on terrorist groups operating in the area.51

Other NATO countries, like Canada, have implemented emergency measures for Sudanese people to ensure their safety while providing humanitarian aid to the war torn country and joining its fellow allies in calling for peace talks.52 Along with the U.S., the United Kingdom and Norway, gathered in the “Troika” group, seeking to steer Western policy on Sudan by using diplomacy to isolate leaders of the conflict and by coordinating humanitarian aid for Sudanese.53

The greater European Union sanctioned companies that manufactured weapons for the SAF and RSF.54 Southern European countries such as Spain, Italy, Greece, and others have felt

the brunt of the migrants fleeing the conflict as they are the closest states to Northern Africa, leading to a potential increase in demand for a more active NATO position on the conflict.55

Turkiye, a NATO member that has previously injected itself into civil wars in Libya and Ethiopia, may have its own interests in the outcome of Sudan’s civil war. General al-Burhan met with Turkish president Recep Tayyir Erdogan and other top officials, and the ideological similarity between the two leaders has created clear indications that Turkiye leans more toward supporting the SAF.56

Seen with this, general trends exist among the members of NATO: that the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is something that cannot be ignored. The general consensus among many of the member states is that a greater involvement in the civil war would be dangerous, and that indirect aid is the way to go, however, as conditions get worse, this could quite possibly change. Prompted by the horrors of the war, as well as the effects it has on global security, NATO members may reconsider their stance.

United States of America

Canada

United Kingdom

French Republic

Italian Republic

Sanctions imposed against both sides and heavy focus on humanitarian aid while aiming for peace talks (alongside Saudi Arabia).

Focus on safety for Sudanese citizens and offering money and intelligence

Similar to U.S. actions through sanctions and supplies sent to the Sudanese people.

Mainly has focused on advocating for peace and ceasefire talks

Concerned about migrant flows increasing due to the ongoing conflicts in the region.

Federal Republic of Germany

Kingdom of Norway

Like France, has heavily focused on condemning the violence and also has helped in evacuation efforts.

Has worked with the United States and United Kingdom to issue statements and focused on sending aid (‘Troika’).

Greece Has worked independently and with the EU on evacuation efforts, and has joined the international community in condemning the violence.

Republic of Turkiye

Turkiye’s president favors relations with alBurhan.

Question to Consider

1. As an organization, what level of involvement does NATO’s goal of keeping peace and seeking security warrant in the Sudanese Civil War?

2. What exact measures should NATO take to provide humanitarian assistance to Sudan?

3. What are the risks of directly intervening in the Sudanese Civil War?

a. Could NATO partner with an organization like the AU diplomatically or militarily?

b. What kind of risk is posed through interaction with other foreign forces such as Russia’s Wagner Group?

4. What is the role of the individual nations involved in NATO in discussion toward Sudan?

5. How can individual NATO members use their influence to create a consensus approach to stopping interference by China, Russia, as well as other African and Middle Eastern countries?

Topic 2: The Ongoing Resettlement of Afghan Refugees

During the withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan in August 2021, NATO forces evacuated over 120,000 Afghan civilians and employees from the country in a two-week span, primarily through Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul.57 Many NATO members agreed to admit thousands of Afghans and their families — many of whom had assisted NATO during the War in Afghanistan — as refugees, protecting them from Taliban retaliation. While NATO’s presence in the country has officially ended, the effort to resettle Afghan civilians many of whom had their lives uprooted with few personal savings or belongings intact is an ongoing process.

Many countries are still processing tremendous backlogs of Afghans that arrived during the summer of 2021; for example, roughly 35,000 of the approximately 72,000 refugees accepted by the United States remain housed on six of the country’s military bases,58 awaiting either final visa approval, sponsors, or affordable housing to become available.

The United States has largely relied on NGOs to provide essential resources to Afghans, but delays in communication about the number of Afghans arriving, as well as budget cuts for refugee services put in place by the first Trump administration stalled this critical assistance.59 Additionally, some European governments placed limits on the number of Afghans they were willing to accept, citing the strain of past migrant crises on their immigration and resettlement systems. 60

Slow and under-resourced resettlement systems weigh down governments and disadvantage Afghans by delaying their new lives and opportunities in their new home countries. A collective effort to build infrastructure that alleviates these troubles could improve resettlement operations in many NATO member countries, but currently do not exist. Twenty

NATO members contributed to the evacuation effort in August 2021 by aiding with construction of housing facilities, as well as by contributing vehicles, construction equipment, and personnel.61 While this provided temporary shelter during the otherwise chaotic evacuation, NATO left individual members to handle refugee resettlement within their borders. However, the alliance could potentially lend its resources and over 3,500,000 combined personnel62 to assist governments with processing remaining refugee queues. It might even be possible for NATO to help construct affordable housing, quality health facilities, and other public services to move Afghans out of the facilities where NATO members are temporarily housing evacuated Afghans, while providing a more stable structure to ensure their economic mobility and well-being.

Case Study 1: Strain Delays Resettlement Assistance from NGOs in the United States63,64

The United States is just one example of a NATO member that faces a strain from resettling a long backlog of Afghan evacuated during the withdrawal. The evacuees have been classified by their visa status, and their immediate future, as well as their long-term settlement, will depend on the mix of government and private services for which they may be eligible due to their status.

In late August 2021, at the height of the Afghanistan evacuation, nine NGOs were contracted with the U.S. Department of State to provide humanitarian assistance to Afghans with valid visas through 2022. This assistance includes aid in searching for housing and jobs as well as directing them to social services. It was imperative for these NGOs to know how many Afghans they would be delegated and how quickly Afghans would arrive, in order to provide sufficient support by the first refugees’ arrival. However, some leaders of these NGOs claimed

that these figures were not provided before the Afghans began arriving, despite multiple requests to the federal government. NGOs usually have weeks to prepare for arrivals of refugees from other countries, but in the case of the newly arriving Afghans, they were sometimes given only one day’s notice before a group arrived. This lack of communication initially hindered the organizations’ ability to hire the right number of staff, train volunteers, and supplement their budgets to facilitate the resettlement. Mark Hetfield, president of the resettlement non-profit HIAS, observed, “We’re going to make it work, no matter how difficult, but I’d be lying to you if I said we aren’t concerned.”

Access to essential assistance is even less accessible to the nearly 50,000 of the United States’ total refugee allotment who arrived without valid visas. These civilians are granted “humanitarian parole” and allowed to live in the United States while awaiting their approval, but with this status, they lack the access to the same benefits that visa holders are entitled to receive from the federal government. This initially limited many Afghans’ ability to secure essential goods and services if they could not personally afford them and makes the role of the NGOs even more essential.

Following news of the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, Americans reached out to NGOs to volunteer to assist Afghan refugees, but having to sort through the requests to help only added to the workload of these organizations. Federal aid may help these organizations provide help locally, as the government authorized the payment of $2,275 for each Afghan that organizations help to resettle. Pastor Dom Martin, who leads Chicago’s Freedom Hope Church, which “had never worked with refugees until now, said he felt moved by news images of people fleeing to the airport in Kabul.” He recalled thinking, “Wow, [the Afghan refugees] are coming to our neighborhood. We need to help.”

A volunteer at Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, a resettlement NGO in Baltimore, MD, carries supplies for Afghan refugees donated to the organization.65

Case Study 2: NATO’s Kosovo Housing Operation66

As a coalition of American, British, Turkish, and Norwegian troops secured the Kabul airport and evacuated Afghans, staff from NATO’s Response Force were delegated the crucial task of providing evacuated Afghans with “care and support, including through individual and family living quarters, dining facilities, medical and dental centers, meeting rooms, recreation areas for adults and children, and religious accommodations”. Afghans who assisted NATO during the War in Afghanistan would reside at the facilities at Camp Bondsteel, a United States Army base near Pristina, Kosovo, following their evacuation. In August, roughly 2,000 of these Afghans and their families were housed in this facility.

A group of Afghan refugees are guided by NATO staff as they arrive in Kosovo on August 29.67

These facilities were managed by a group of nearly 300 NATO troops during the 24/7 evacuation operations.68 This intermediate step in the resettlement effort required medical personnel, security details, engineers, communications experts, cooks, and even more staff to work in tandem.

For the eighty Afghans and their families headed to Norway from the Kosovo facility, identification and background checks were performed before their departure. The Norwegian government planned to fly them from Kosovo to Norway on a private flight, where they would begin an integration process conducted by the Norwegian government that could last two weeks or more.

Alan Aguillar, Senior Advisor of Norway’s National Police Immigration Service, expressed satisfaction regarding his agency’s work with NATO staff. He stated, “We have had a

good cooperation and coordination with NATO on the ground; it has been a smooth process from start to end.”

As one of the only organizations with sufficient connections to European nations, employees of diverse skillsets, and resources to operate a housing installation to this scale, NATO became instrumental in initiating the resettlement process for thousands of Afghans. It is worth considering how NATO’s collective resources could be utilized to streamline the resettlement process for its member countries. The specifics of constructing more resettlement facilities and other crucial infrastructure would likely be decided within NATO’s Civil Emergency Planning Committee,69 Resource Policy & Planning Board,70 and Logistics Committee.71 These bodies are crucial to involve in NATO’s humanitarian operations, as they facilitate the discussions between civil operations experts and government representatives necessary to organize assistance towards NATO operations and needs of member states.

Bloc Positions

Pro-Resettlement countries have either promised to admit large numbers of Afghan refugees from the evacuation or enable Afghans who have been admitted to access a great number of resources and protection, with some governments having pledged to do both. Some of this bloc’s European countries, such as Germany, have experienced sudden increases in refugee intake prior to the evacuation, particularly during the 2015 refugee crisis (in which over 900,000 refugees sought asylum in Europe, including seventy-five percent from Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq.)72 The leaders of these countries have expressed that treating incoming Afghans with respect and support is a moral obligation — especially for those who assisted NATO during the

war — thus suspending deportations and admitting more groups of Afghans throughout the second half of 2021. Public support in these countries is generally high for resettling NATO’s Afghan allies, including over seventy percent of the public support in the United States.73

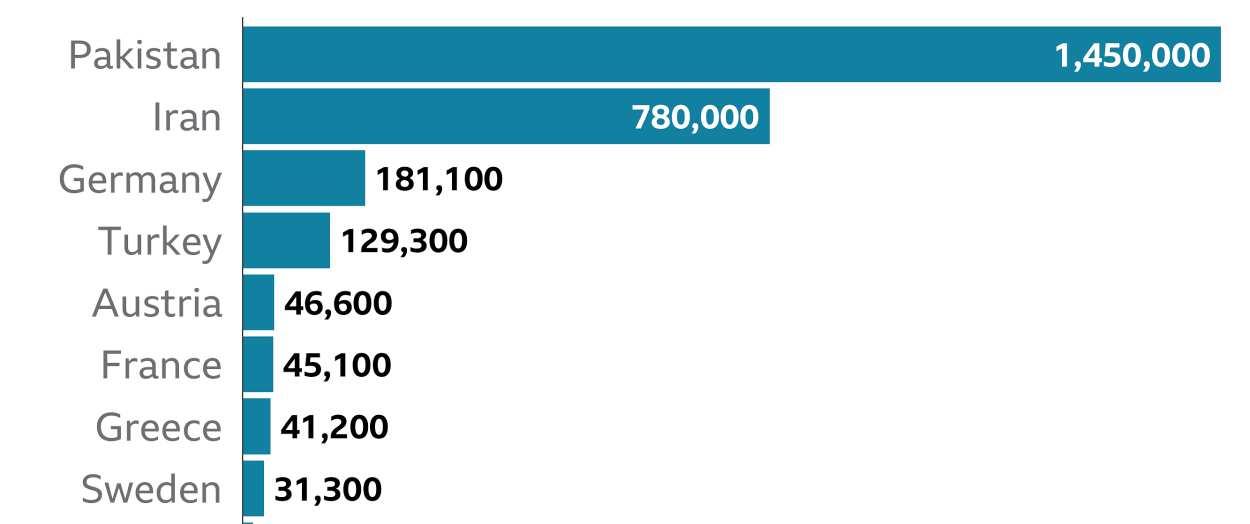

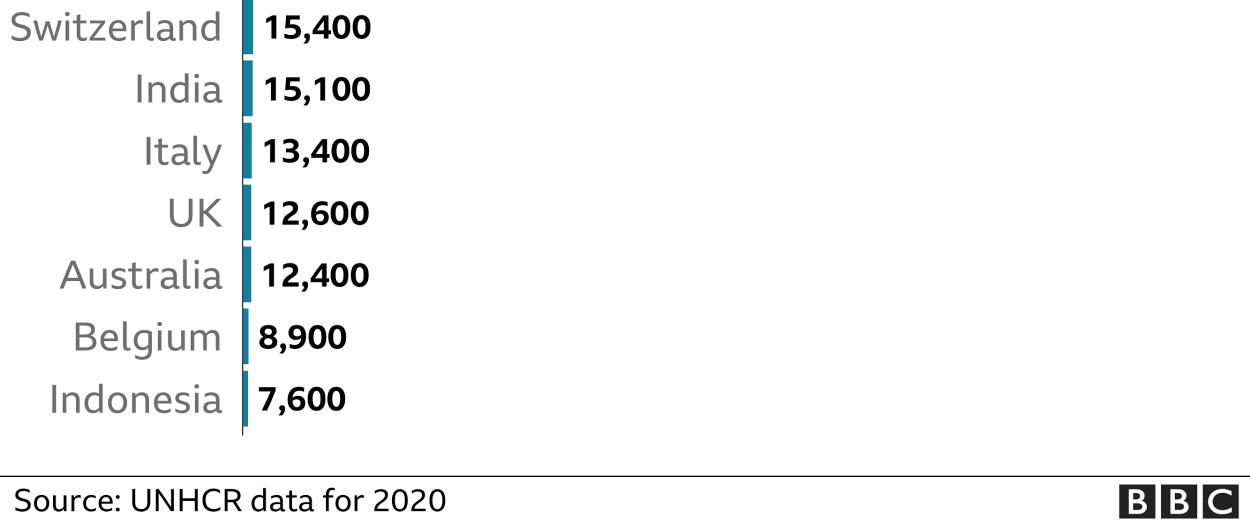

Countries with the largest intakes of Afghan refugees in 2020. Prior acceptance of Afghans has influenced some nations’ policy regarding the resettlement of those displaced by the evacuation in 2021.74

Non-Settlement countries have entitled Afghans to less protection and fewer entitlements, compared to the Pro-Resettlement bloc. Their governments would generally prefer that Afghans are settled in regions deemed “safe” for them to reside, rather than use resources to support Afghans within their borders. Their governments placed conservative limits on the number of Afghans they would accept due to the evacuation, with many leaders citing the strain of the 2015 refugee crisis on their immigration systems as justification.75 Turkey, one of the main destinations for Afghan refugees of the 2015 crisis, has remained resistant to accepting Afghans from the evacuation, directing its resources towards a new border wall on its Iranian border and

intensified security instead.76 Some of these countries have also been accused of violence, xenophobia, and further poor treatment toward the Afghan refugees they have admitted.77

While these blocs represent general patterns of policy, it is crucial for delegates to research the individual commitments their countries have made to admitting Afghans, and what specific systems their countries have put in place to support or turn away Afghans.

Pro-Resettlement Countries

● Albania

● Belgium

● Canada

● France

● Germany

● Iceland

● Italy

● Lithuania

● Luxembourg

● Montenegro

● Netherlands

● North Macedonia

● Norway

● Portugal

● Romania

● Slovakia

● Spain

● United Kingdom

● United States

Non-Settlement Countries

● Bulgaria

● Croatia

● Czech Republic

● Denmark

● Estonia

● Greece

● Hungary

● Latvia

● Poland

● Slovenia

● Turkey

Guiding Questions

1. How many Afghans has your country admitted from the evacuation?

2. Which services does your country guarantee to the Afghans it has admitted?

3. Have you read stories of Afghan refugees resettling in your country and learned about challenges they have faced by the resettlement system? Have you read the accounts of local resettlement organizations and their challenges?

4. What have been the notable successes of your nation’s resettlement process? Issues?

5. How has your country tried to alleviate complications in its resettlement system?

6. How might your nation benefit from NATO resources to improve its resettlement system?

Endnotes

1 “NATO: Key Events.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/nato-welcome/

2 “NATO: Member Countries.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/nato-welcome/

3 “NATO: Basic Points.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/nato-welcome/

4 “NATO: Working Structures.” NATO. Ibid. https://www.nato.int/nato-welcome/

5 “Why Sudan’s catastrophic war is the world’s problem.” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2024/08/29/why-sudans-catastrophic-war-is-the-worldsproblem. August 29, 2024

6 Hendawi, Hamza. “Out of the Darfur desert: the rise of Sudanese general Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo.” The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/africa/out-of-the-darfur-desertthe-rise-of-sudanese-general-mohammed-hamdan-dagalo-1.855219 April 30, 2019

7 “100 days of conflict in Sudan: A timeline.” Al Jazeera.. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/7/24/100-days-of-conflict-in-sudan-a-timeline. July 24, 2023

8 “What is happening in Sudan? A simple guide.” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/18/what-is-happening-in-sudan-a-simple-guide Last updated: May 3, 2023.

9 Bhaumik, Anirban. "India launches Operation Kaveri to evacuate its nationals from Sudan." Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/india-launches-operation-kaveri-toevacuate-its-nationals-from-sudan-1212522.html. Last Updated : 24 April 2023.

10 Geiger, Waldemar. “German citizens evacuated from Sudan.” Soldat & Technik. https://soldat-und-technik.de/2023/04/streitkraefte/34619/bundeswehr-evakuiert-deutschestaatsbuerger-aus-dem-sudan/ April 24, 2023.

11 “Conflict Tracker: Civil War in Sudan.” Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/power-struggle-sudan

12 https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/sudanese-politicians-blame-bashir-loyalists-discord2023-04-14/

13 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/sudan-unrest-militia-rapidsupport-forces-janjaweed/

14 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/sudan-turmoil-bashir-fall-fighting-khartoum-timeline

15 https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/sudan/stopping-sudans-descent-full-blowncivil-war

16 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/13/sudans-army-warns-of-rsfs-movements-inkhartoum-other-cities

17 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65284945

18 https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/sudan-army-chief-burhan-appears-public-first-timesince-war-started-statement-2023-08-24/

19 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65569513

20 https://www.africanews.com/2023/08/29/sudans-al-burhan-heads-first-cabinet-meeting-sinceconflict-erupted/

21 https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230921-sudan-army-chief-warns-un-that-warcould-spill-over-in-region

22 https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2023/06/23/South-Kordofan-residents-flee-asSudan-war-escalates

23 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jul/13/bodies-of-87-people-found-in-sudan-massgrave-says-un

24 https://sudanwarmonitor.com/p/fall-of-the-16th-division-headquarters

25 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/12/24/sudans-civilians-pick-up-arms-as-rsf-gains-andarmy-stumbles

26 https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/05/24/sudan-the-war-the-world-forgot

27 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/7/10/regional-bloc-calls-for-summit-to-consider-sudantroop-deployment

28 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/2/sudans-feared-paramilitary-leader-signals-ambitionto-rule-the-country

29 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/16/sudan-suspends-contacts-with-igad-mediatinggroup-foreign-ministry

30 https://sudanwarmonitor.com/p/khartoum-control-map-april-2024

31 https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/sudan/b198-halting-catastrophic-battle-sudansel-fasher

32 https://www.voanews.com/a/analysts-presence-of-foreign-actors-complicates-sudan-warsituation/7663775.html

33 https://www.polgeonow.com/2024/06/sudan-war-map-2024-june-darfur-joint-forcerebels.html

34 https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/senate-hears-urgent-plea-from-u-s-envoyon-sudan

35 https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crln9lk51dro

36 https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/sudan-situation-unhcr-external-update-68-28-june-4-july2024

37 https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/04/17/world/sudan-fighting-news/sudan-fightingkhartoum

38 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-65448691

39 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2023/4/25/sudan-live-news-sporadic-gunfire-inkhartoum-despite-new-truce

40 AfricaNews. "Fighting in Sudan leaves banking sector in limbo." August 13, 2024. https://www.africanews.com/2023/05/28/fighting-in-sudan-leaves-banking-sector-in-limbo/

41 https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/wfp-says-13-mln-14-mln-worth-food-looted-sudan2023-05-04/

42 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-68187992

43 https://acleddata.com/2024/08/09/sudan-mid-year-metrics-2024/

44 Rampe, William. "What Is Russia’s Wagner Group Doing in Africa?" The Council on Foreign Relations. Last updated May 23, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/what-russias-wagner-groupdoing-africa

45 "Sudan suspended from the African Union." The African Union. January 23, 2025 https://au.int/en/articles/sudan-suspended-african-union

46 "NATO and the African Union boost their cooperation." NATO. May 8, 2014. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_109824.htm

47 "Cooperation with the African Union." NATO. Last updated: April 27, 2023. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_8191.htm

48 Ibid.

49 "The US and the Sudan Conflict: Motives and Ability to Influence Events." Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. Jun 27, 2023. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-us-and-thesudan-conflict-motives-and-ability-to-influence-events/

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 "Canada’s response to the crisis in Sudan." Government of Canada. https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_developmentenjeux_developpement/response_conflict-reponse_conflits/crisis-crises/sudansoudan.aspx?lang=eng

53 Fouche, Gwladys. "Norway says path to peace in Sudan is 'really difficult'" Reuters. January 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/norway-says-path-peace-sudan-is-really-difficult-202401-24/

54 https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/eu-imposes-sanctions-on-six-sudan-entities

55 Tubiana, Jérôme. "Europe Is Making Sudan’s Refugee Crisis Worse." Foreign Policy Magazine. January 8, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/08/sudan-darfur-refugee-crisiseu-migration/

56 https://www.institude.org/opinion/african-civil-wars-and-turkeys-involvement-in-sudan

57 “Allies Continue Their Joint Efforts to Resettle Afghans Who Worked With NATO.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_187205.htm?selectedLocale=en Last updated October 7, 2021.

58 Brady, Erin. “Over 35,000 Afghan Refugees Still Await U.S. Resettlement 4 Months After Evacuation Ended.” Newsweek https://www.newsweek.com/over-35000-afghan-refugees-stillawait-us-resettlement-4-months-after-evacuation-ended-1657433. Published December 8, 2021.

59 Hackman, Michelle. “U.S. Refugee Organizations Race to Prepare for Influx of Afghans.” The Wall Street Journal. https://drive.google.com/file/d/10oZ5VzXf299znoZofOvGFKUn1T6mMU_/view?usp=sharing. Published August 31, 2021.

60 “Afghanistan: How Many Refugees Are There and Where Will They Go?” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58283177. Published August 31, 2021.

61 “NATO Afghan Evacuees Begin Journey to Resettlement.” NATO. https://jfcnaples.nato.int/newsroom/our-afghan-evacuation-mission/nato-afghan-evacuees-beginjourney-to-resettlement Published September 16, 2021.

62 “The Power of NATO’s Military.” NATO. https://shape.nato.int/page11283634/knowingnato/episodes/the-power-of-natos-military.

63 Hackman, Michelle. “U.S. Refugee Organizations Race to Prepare for Influx of Afghans.” The Wall Street Journal. https://drive.google.com/file/d/10oZ5VzXf299znoZofOvGFKUn1T6mMU_/view?usp=sharing Published August 31, 2021.

64 Alvarez, Priscilla. "What is the legal status of Afghans coming to the US? It varies." CNN. Last Updated September 1, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/01/politics/afghanistanevacuation-legal-status/index.html

65 Hackman. “Afghan Refugees in the U.S.: How They’re Vetted, Where They’re Going, and How to Help.” https://www.wsj.com/articles/afghan-refugees-in-the-u-s-how-theyre-vettedwhere-theyre-going-and-how-to-help-11630677004. Last updated September 15, 2021.

66 “Allies Continue Their Joint Efforts to Resettle Afghans Who Worked With NATO.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_187205.htm?selectedLocale=en. Last updated October 7, 2021.

67 “First Group of Afghan Refugees Arrives in Kosovo for Temporary Shelter.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/first-group-afghan-refugees-arrives-kosovo-temporaryshelter-2021-08-29 Last Updated August 29, 2021.

68 Hackman, Michelle. “U.S. Refugee Organizations Race to Prepare for Influx of Afghans.” The Wall Street Journal https://drive.google.com/file/d/10oZ5VzXf299znoZofOvGFKUn1T6mMU_/view?usp=sharing Published August 31, 2021.

69 “Civil Emergency Planning Committee.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_50093.htm Last updated November 15, 2011.

70 “Resource Policy and Planning Board.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_67653.htm Last updated September 12, 2019.

71 “Logistics Committee.” NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_61715.htm. Last updated August 3, 2015.

72 Spindler, William. “2015: The Year of Europe’s Refugee Crisis.” UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/stories/2015/12/56ec1ebde/2015-year-europes-refugeecrisis.html Published December 8, 2015.

73 Rose, Joel. “Support For Resettling Afghan Refugees in the U.S. is Broad – But Has Limits.” NPR https://www.npr.org/2021/09/09/1035240731/support-for-resettling-afghan-refugees-inthe-u-s-is-broad-but-has-limits. Published September 9, 2021.

74 “Afghanistan: How Many Refugees Are There and Where Will They Go?” BBC News https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58283177 Published August 31, 2021.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid.

77 Sanderson, Sertan. "Turkey turns against migrants as fears of Afghan refugee crisis grow." InfoMigrants. September 7, 2021. https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/34891/turkey-turnsagainst-migrants-as-fears-of-afghan-refugee-crisis-grow