Land

September 30, 2013-February 2, 2014

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760-1849)

The Mitsui Shop at Suruga-cho in Edo (detail) from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji Edo period, c. 1830-1831

Woodblock print, ink and color on paper

10.25 x 14.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum Collections Gift of Helen Goldberg HU2001.16.2

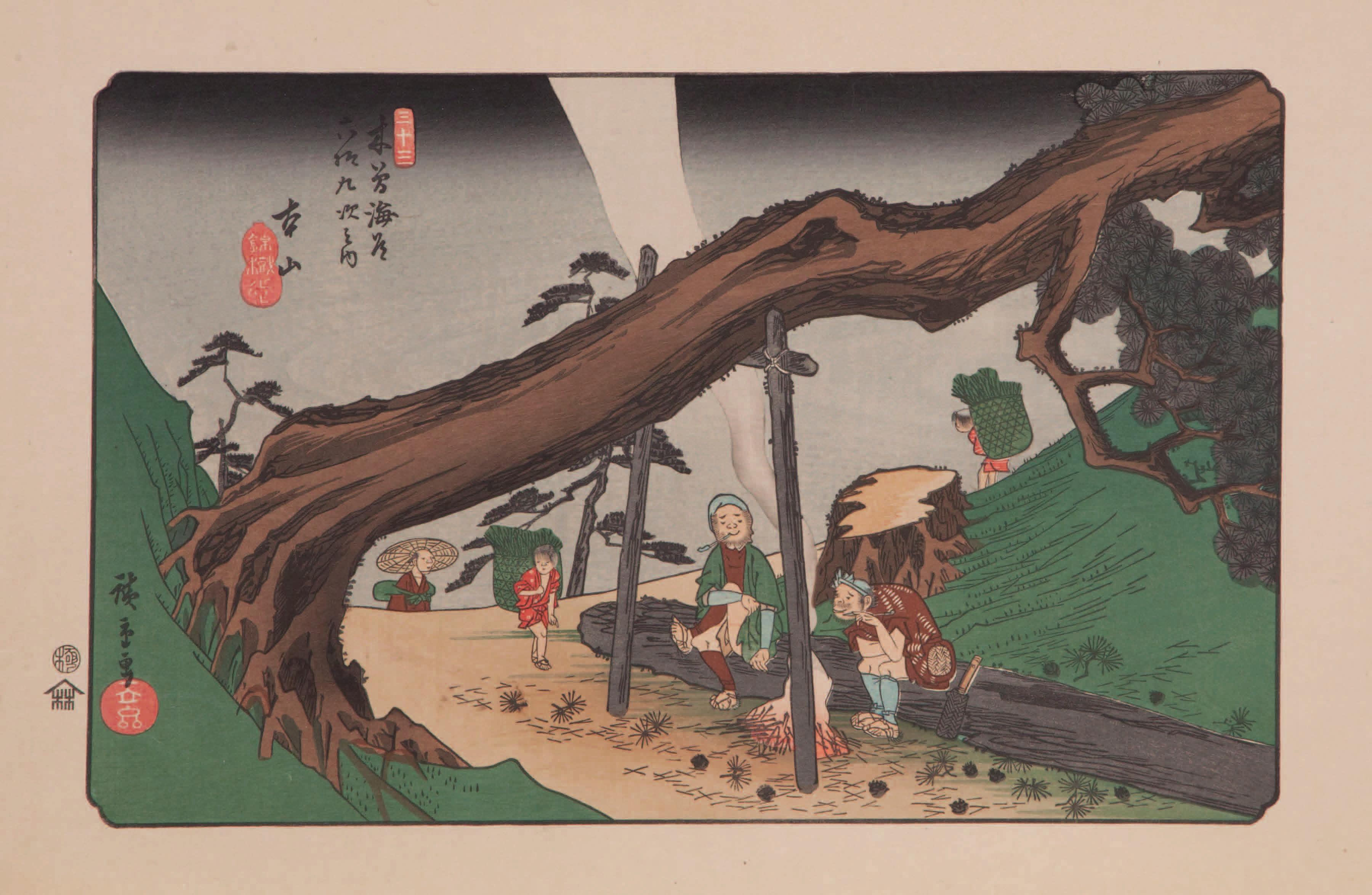

Ando Hiroshige (Japanese, 1797-1858)

Motoyama (detail) from the series

Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaido, 1834-1842

Woodblock print, ink and color on paper

8.75 x 13.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum Collections Gift of Helen Goldberg

HU2003.8.1

Curator’s Statement

This original exhibition highlights Japanese works of art in the Hofstra University Museum’s permanent collections, which contain 150 works from Japan in a wide range of styles and media. For this exhibition a focus is placed upon decorative arts and objects, hand-painted hanging scrolls, sculpture and color woodblock prints dating from the 16th to the 20th century.

Japanese art and culture have developed over many centuries but, prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the mid-6th century, the islands were fairly isolated. Similar to other countries and cultures around the world, a combination of internal and external factors has infuenced the evolution of Japanese culture. Particularly, the two religions of Shintoism and Buddhism have had a strong impact on the culture and visual arts of Japan. Shintoism, the traditional religion of Japan, is based upon the power of nature in combination with a respect for ancestry. Shinto deities, called kami, are spirits that animate human, animal and natural forms such as rocks, mountains, and waterfalls. Kami are not separate but exist within the same world as man. In the 8th century, Shintoism became more formalized in response to the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. Buddhism, which originated in India about 1,000 years before coming to Japan, is based on the teaching that life is sorrowful because all beings are bound to the physical world in an endless cycle of reincarnation. In order to break this cycle, one must attain spiritual enlightenment through meditation and high moral conduct. The arrival of Buddhism into Japanese culture and society came about through interactions with China. The Chinese culture had a major impact upon Japanese society and, through trade routes to India and Persia, exposed Japan to other cultures. The two religions of Shintoism and Buddhism were united in Japan during the 11th century, with the Shinto kami regarded as manifestations of

specifc Buddhist deities. This integration lasted until the mid-19th century when Shintoism was formally separated from Buddhism during the Meiji Restoration. Many Japanese continue to practice both religions, which are not contradictory in theory or practice.

During the Heian and Kamakura periods from the 10th to 14th centuries, Japan began to turn away from the infuence of China, focusing once more upon its own traditions, as well as assimilating and borrowing from prior Japanese artistic periods to create new artistic directions. During this period, most carved wood sculpture, sometimes with pigments added, depicted religious fgures and often had protective qualities. As an example, in this exhibition the Pair of Shishi (HU70.13.1-2) would have traditionally stood guard outside a shrine or temple, as they are believed to have magical properties and the power to repel evil spirits. As the interest in traditional religious practices waned, art became more secular. In the late 12th century, Japanese imperial power ended along with the rise of the military class: shoguns and samurai. During this period Chinese Zen Buddhist monks were welcomed into Japan, bringing with them their culture and art. The strong infuence of Zen Buddhism in ink painting can be seen in its more secular imagery, which emphasizes man’s desire for nature’s solace and inspiration, frequently depicting a scholar’s hermitage in a landscape. Compared to Chinese ink painting, the Japanese style portrays more intimate views and demonstrates more expressive brushwork.

From the end of 16th century until the mid-19th century, Japan was unifed by a strongly controlled feudal system. A self-imposed policy of isolation compelled the Japanese to again look inward. The elements from foreign cultures that complemented the Japanese aesthetic were absorbed and assimilated into the visual arts. For example, the contemplative landscapes initially infuenced by Chinese culture were incorporated into the tradition of Japanese ink painting as seen in two 19th century hanging scrolls, called

kakemono, in this exhibition: Scholar Playing a Biwa (HU70.40) and Landscape (HU70.39). With the emphasis on past traditions, ceramics and applied arts fourished during this period. The 17th-18th century Jar (HU70.10) and the 19th century Bottle (HU70.26) represent different styles of ceramics. The 19th century Fan (HU70.3) demonstrates the renewed interest in surface design and the tradition of lacquer ware. Traditional visual arts, rooted in the national character, were revived, reinvented and refned. The popularity of woodblock prints, known as ukiyo-e, grew during the Edo period (1615-1868). Typically depicting courtesans and actors, the imagery of the prints expanded to include landscape vistas and sites throughout the country. This exhibition includes 14 prints by seven artists illustrating the different motifs. The relatively inexpensive prints were admired both in Japan and abroad.

International trade and travel was heavily restricted until the mid-19th century when Japan opened trade with America. The West was initially interested in ceramics and woodblock prints, but as knowledge and awareness of Japanese art increased, the interest in other traditional arts expanded. As Japanese art has been infuenced by other cultures, it too has had a major impact on Western art. An interest in the exotic during the late 19th century led to the importation of Japanese works of art into Europe and America. The Japanese woodblock prints with their fat planes of color and strong linear outlines, in particular, were studied and became a source of inspiration to artists of the time such as Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse, and Vincent van Gogh.

Karen T. Albert Associate Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Japanese Japanese

Bottle, 19th century Fan, 19th century

Pottery and glaze Ivory with gold lacquer

7.5 x 4.5 in. diameter 10 x 15.75 in.

University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

HU70.26 HU70.3

Japanese

Mask of Yakko, 19th century

Wood and lacquer

8.5 x 6.5 x 3.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

HU70.35

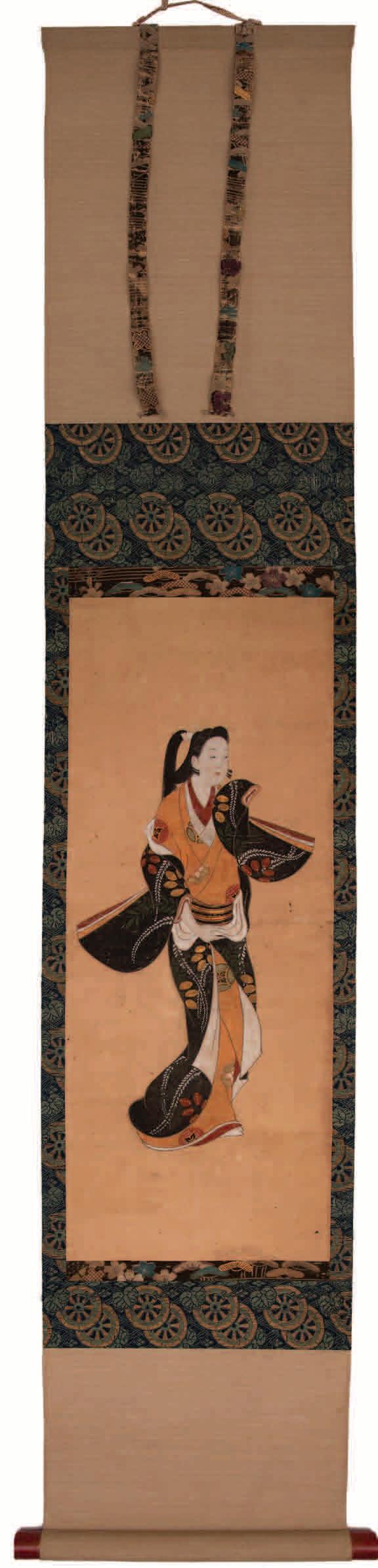

Japanese

Beautiful Girl (Bijin-e), 19th century

Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper

30.5 x 10.5 in.; 65 x 12 in. overall

Hofstra University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

HU70.33

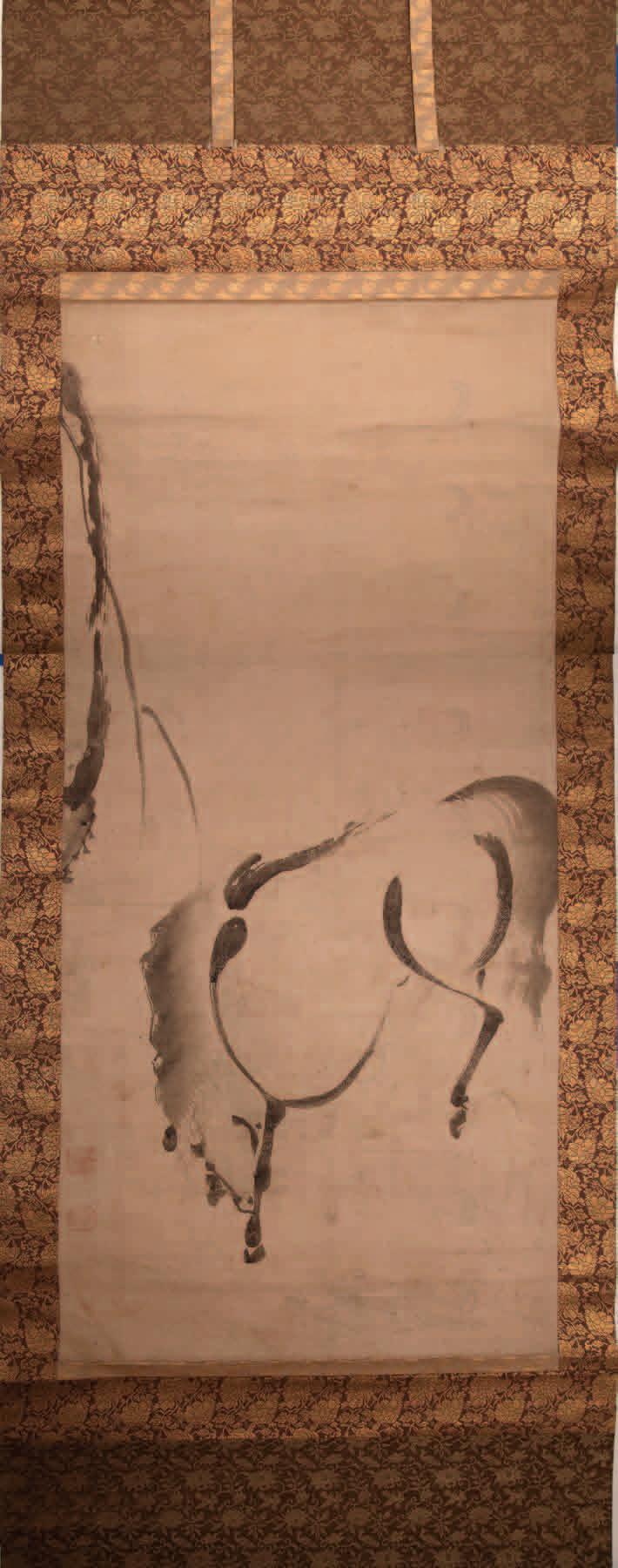

Japanese

Haboku-style Horse, 18th century

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

45 x 21.25 in.; 79.5 x 28. 5 in. overall

Hofstra University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

HU70.14

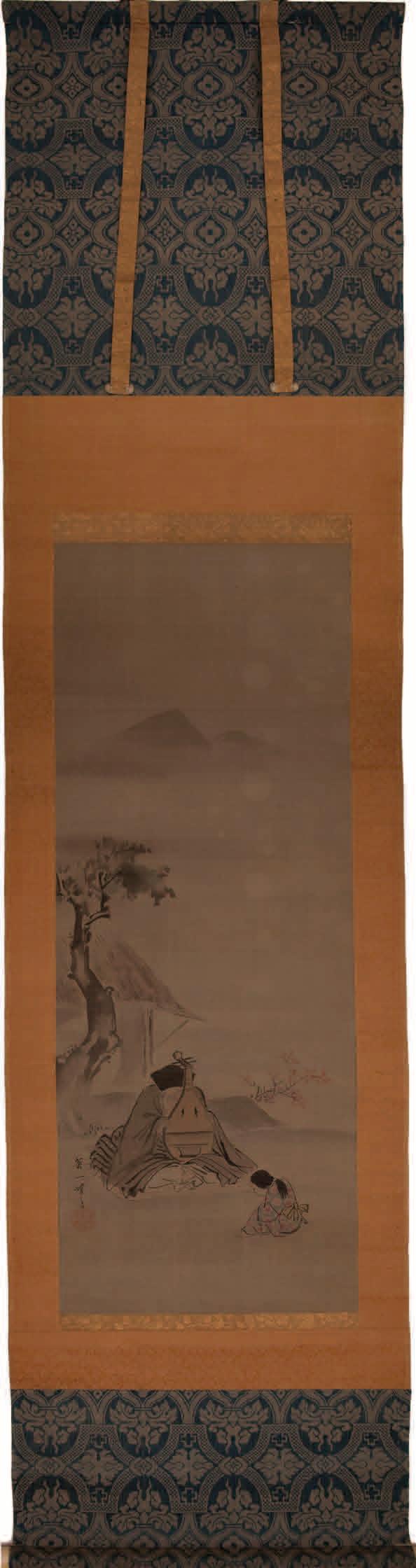

Japanese

Scholar Playing a Biwa, 19th century

Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk

33.875 x 13 in.; 68 x 17 in. overall

Hofstra University Museum Collections

Gift of Albert M. Baer

HU70.40