A comparison of baseline attitudes, anxiety and burnout related to the USMLE Step 1 exam in first and second year medical students. Daniel Lynch, Elisabeth Schlegel, MSc, PhD, MBA, MS-HPPL Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell

Introduction: In the past ten years, the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 exam (“Step 1”) has become a critical part of residency applications, with many residency program directors using Step 1 scores as a primary factor in deciding which candidates to interview for residency positions (NRMP Program Director Survey, 2018). Despite being originally designed to assess basic science knowledge, the importance of Step 1 in the residency application process has created a so-called “Step 1 climate”, where students focus on preparing for Step 1 at the expense of other activities (Chen et. al, 2019). As a result of this, some have argued in favor of changing the score reporting on Step 1 to a pass-fail system, where students and residency programs would no longer receive a numerical score (Carmody et. al 2019).

The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) released a statement in February of 2020 stating their intention to transition to reporting only a pass/fail outcome for Step 1. This change in scoring may result in significant changes to student preparation for the exam and overall wellness. There is a wide body of existing research regarding medical student preparation for Step 1 (Burk-Rafel et. al, 2017, Bhatnagar et. al, 2019, Deng et. al, 2015). Currently, there is no data regarding medical student behavior and attitudes related to the change to unscored Step 1 exams, representing a gap in the literature that we aim to fill. This study developed a baseline understanding of the attitudes of Zucker School of Medicine students regarding Step 1 as well as measuring anxiety and burnout associated with preparing for the exam. This will be used to compare the MS2 class (taking a scored Step 1 exam) with the MS1 class (taking a pass/fail Step 1 exam).

Methods: Quantitative data was collected via an electronic survey sent to cohorts of first and second year medical students at the Zucker School of Medicine (estimated maximum sample size of 200). Student identity was kept confidential. Students were asked questions regarding their attitudes towards examinations and Step 1. Students were also asked to complete brief validated measures of burnout and anxiety such as a short-form burnout inventory (Taylor and Deane, 2002) comparable to the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach and Jackson, 1996), as well as a short form of the Test Anxiety Inventory (Taylor and Deane, 2002) and the seven-question form of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (Spitzer et. al, 2006). These questions were supplemented with a series of brief non-validated questions generated by the research team to gather information about student attitudes towards Step 1. Specific data collected included class year, plans for taking Step 1, attitudes toward board exams, and the psychosocial impact of preparation (anxiety, burnout). Quantitative data was analyzed using statistical analysis software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v27, 2020).

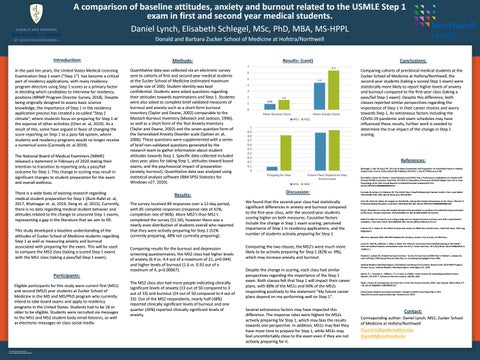

Results: The survey received 89 responses over a 12-day period, with 85 complete responses (response rate of 41%, completion rate of 96%). More MS2’s than MS1’s completed the survey (51:34), however there was a nearly even distribution of students overall who reported that they were actively preparing for Step 1 (52% currently preparing, 48% not currently preparing). Comparing results for the burnout and depression screening questionnaires, the MS2 class had higher levels of anxiety (6.4 vs. 4.4 out of a maximum of 21, p=0.044) and higher levels of burnout (1.6 vs. 0.93 out of a maximum of 4, p=0.00067).

Participants: Eligible participants for this study were current first (MS1) and second (MS2) year students at Zucker School of Medicine in the MD and MD/PhD program who currently intend to take board exams and apply to residency programs in the United States. Students had to be 18 or older to be eligible. Students were recruited via messages to the MS1 and MS2 student body email listservs, as well as electronic messages on class social media.

RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2019

www.PosterPresentations.com

The MS2 class also had more people indicating clinically significant levels of anxiety (13 out of 50 compared to 3 out of 33) and burnout (24 out of 50 compared to 4 out of 33). Out of the MS2 respondents, nearly half (48%) reported clinically significant levels of burnout and one quarter (26%) reported clinically significant levels of anxiety.

Results: (cont)

Conclusions:

7

6.4

6 5

4.4

4 3 2 1

1.6 0.93

0 Mean Burnout Score

Mean Anxiety Score MS1

MS2

1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0

Comparing cohorts of preclinical medical students at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, the second-year students (taking a scored Step 1 exam) were statistically more likely to report higher levels of anxiety and burnout compared to the first-year class (taking a pass/fail Step 1 exam). Despite this difference, both classes reported similar perspectives regarding the importance of Step 1 in their career choices and worry towards Step 1. As extraneous factors including the COVID-19 pandemic and exam schedules may have influenced these results, further work is needed to determine the true impact of the change in Step 1 scoring.

References: Bhatnagar V, Diaz SR, Bucur PA. The Cost of Board Examination and Preparation: An Overlooked Factor in Medical Student Debt. Cureus. 2019;11(3):e4168. Published 2019 Mar 1. doi:10.7759/cureus.4168

Prepping for Step

Future Plans Depend on Step Performance MS1

MS2

Discussion: We found that the second-year class had statistically significant differences in anxiety and burnout compared to the first-year class, with the second-year students scoring higher on both measures. Causative factors include the change in Step 1 exam scoring, perceived importance of Step 1 in residency applications, and the number of students actively preparing for Step 1.

Burk-Rafel J, Santen SA, Purkiss J. Study Behaviors and USMLE Step 1 Performance: Implications of a Student SelfDirected Parallel Curriculum. Acad Med. 2017;92(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S67-S74. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001916 Carmody JB, Sarkany D, Heitkamp DE. The USMLE Step 1 Pass/Fail Reporting Proposal: Another View. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(10):1403-1406. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2019.06.002

Chen DR, Priest KC, Batten JN, Fragoso LE, Reinfeld BI, Laitman BM. Student Perspectives on the "Step 1 Climate" in Preclinical Medical Education. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):302-304. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002565 Deng F, Gluckstein JA, Larsen DP. Student-directed retrieval practice is a predictor of medical licensing examination performance. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(6):308-313. doi:10.1007/s40037-015-0220-x Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582-587. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6 Frierson HT Jr, Hoban JD. The effects of acute test anxiety on NBME Part I performance. J Natl Med Assoc. 1992 Aug; 84(8):686-9 IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Comparing the two classes, the MS2’s were much more likely to be actively preparing for Step 1 (82% vs. 9%), which may increase anxiety and burnout. Despite the change in scoring, each class had similar perspectives regarding the importance of the Step 1 exam. Both classes felt that Step 1 will impact their career plans, with 88% of the MS1s and 94% of the MS2s responding positively to the statement “My future career plans depend on me performing well on Step 1”. Several extraneous factors may have impacted this difference. The response rates were highest for MS2s actively preparing for Step 1, which may bias the results towards one perspective. In addition, MS1s may feel they have more time to prepare for Step 1, while MS2s may feel uncomfortably close to the exam even if they are not actively preparing for it.

Lewis CE, Hiatt JR, Wilkerson L, Tillou A, Parker NH, Hines OJ. Numerical Versus Pass/Fail Scoring on the USMLE: What Do Medical Students and Residents Want and Why?. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(1):59-66. doi:10.4300/JGME-D10-00121.1 Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory - Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). In Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (eds.) MBI Manual (3rd ed.) Palo Alto, CA. Consulting Psychologists Press 1996. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2018 Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine, 166(10), 1092. Taylor J, Deane FP. Development of a short form of the Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI). J Gen Psychol. 2002;129(2):127136. doi:10.1080/00221300209603133 United States Medical Licencing Examination. Changes to USMLE Score Reporting in 2022. https://www.usmle.org/usmlescoring/. Accessed June 2020.

Contact: Corresponding author: Daniel Lynch, MS2, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell DLynch12@pride.hofstra.edu DLynch8@northwell.edu