18 minute read

Behavior Management in the Early Childhood Classroom: Preschool Teachers’ Self-Reported Usage Prevention and Intervention Strategies Marla J. Lohmann

Behavior Management in the Early Childhood Classroom: Preschool Teachers’ Self-Reported Usage Prevention and Intervention Strategies

Marla J. Lohmann, PhD Colorado Christian University

Advertisement

Abstract

Behavior challenges, including aggression, are prevalent in today’s classrooms and have a direct impact on children’s learning and development. Many behavior challenges begin in early childhood years, but the use of evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies can reduce the long-term implications of early childhood aggression. While the research tells us that prevention and intervention strategies successfully reduce challenging behaviors, there is little indication of the frequency with which preschool teachers are utilizing these strategies. In order to better understand the implementation of these practices, a survey of teachers’ self-reported usage was conducted. The results of that exploration, as well as further directions in teacher training and research, are described in this article.

Behavior Management in the Early Childhood Classroom: Preschool Teachers’ Self-Reported Usage Prevention and Intervention Strategies

In today’s classroom, behavior problems, including aggression, are prevalent and serve as a barrier to learning for many students. According to the Centers for Disease Control (2018), six percent of children skip at least one day of school each year as a result of feeling unsafe due to violence in the school setting. Being absent from school leads to lower academic achievement (Gottfried & Kirksey, 2017) and a reduced likelihood of high school graduation (Smerillo et al., 2018). It is clear that aggression in schools must be addressed and research indicates that challenging behaviors beginning in preschool often continue throughout the school years (Carbonneau et al., 2016; Huesmann et al., 2009). Over fifty percent of young children exhibiting aggression will later be diagnosed with a behavior disorder (Kendziora, 2004). However, the use of evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies in the early childhood years can reduce the likelihood of later aggression (Brotman et al., 2008; Fung, 2018).

The literature presents a variety of strategies for the prevention and intervention of challenging behaviors in the preschool classroom, including (a) collaborating with families (Booster et al., 2016; Dunlap et al. 2006; Fox et al., 2003; Powell et al., 2006), (b) explicitly teaching classroom routines and expectations (Carter & Ellis, 2016; Hester et al., 2009; Stormont et al., 2008), (c) rewarding positive behaviors and using praise statements (Bellone et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2003; Fox & Little, 2001; Fullerton et al., 2009; Tiano et al., 2005), (d) making adaptations to the classroom environment (Heo et al., 2014; Isbell & Exelby, 2001; Sharma et al., 2008), (e) using pre-correction statements (Blair et al., 2000; Haydon & Kroeger, 2016; Stormont et al., 2007), (f) redirecting (Evertson et al., 2000; Fox & Little, 2001), (g) teaching replacement behaviors and new skills (Dunlap et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2003; LeGray et al., 2013), (h) teaching social and emotional strategies (Fox et al., 2003; Heo et al., 2014; Malinauskaite, 2010; Pahl & Barrett, 2007), and (i) using functional behavioral assessments (Dunlap et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2003; Heo et al., 2014; Scott et al., 2007). Although the literature documents the effectiveness of prevention 143

and intervention strategies, it is unclear the extent to which teachers are utilizing these practices. To gain a better understanding of preschool teachers’ implementation of evidence-based behavior management strategies, an online survey was sent to public preschool teachers in selected school districts in Texas. Specifically, the researchers looked to answer two questions through the present study: (a) to what extent do preschool teachers self-report using evidencebased prevention and intervention strategies to manage aggressive behaviors in their classrooms and (b) what teacher variables (age, gender, type of teaching position, type of teaching certificate, school type, type of school district, number of students in class and school, level of education, and years of teaching experience) are most salient in predicting the self-reported usage of evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies for the management of aggressive behaviors in the preschool classroom?

Methods Study Participants

Subjects were drawn from a pool of public preschool teachers in the Head Start, Preschool Program for Children with Disabilities (PPCD), and prekindergarten programs (Pre-K) in Texas. Selected Texas Education Service Centers (ESCs) aided in the facilitation of participant recruitment by emailing the invitation to participate to all preschool teachers in their respective regions. One hundred and three teachers participated in the study. Table 1 outlines the demographic characteristics of study participants. For some questions, not all study participants responded, thus the total number of responses for a given question did not always equal 103.

Table 1 Demographic Information of Study Participants Demographic Characteristics Age Age 20-35 Age 36-50 39 (37%) 32 (31.1%) Gender Female Male 102 (99%) 1 (1%) Type of Pre-K PPCD Classroom classroom 30 (30%) 49 (49%) State Fully state Provisionally Certification certified certified 77 (78%) 8 (8%) Highest degree Bachelor’s Master’s earned 69 (74%) 23 (25%)

Years of teaching 0 – 2 years 24 (23.3%) 3 – 5 years 22 (21.4%) Age 51-65 30 (29.1%)

Head Start 21 (21%)

No state certification 14 (14%) Educational Specialist 4 (4%) experience

6 – 8 years 14 (13.6%) 9 – 10 years 7 (6.8%) 11+ years 34 (33%)

In addition to demographic data regarding the teachers’ qualifications, specific information about the school and districts in which they worked was also collected. Study participants taught in either an elementary school (48%, N=49) or a separate Pre-K center (52%, N=54); all

144

participants were employed by a public school district. Additional information about the schools can be found in Table 2.

Table 2 School and Class Demographic Information Demographic Characteristic Categories Suburban Urban 50 – 100 students 101-150 students More than 150 students 5 – 8 students 9 – 12 students 13 – 16 students 17 – 20 students More than 20 students 1 – 2 students 3 – 4 students 5 – 6 students 7 – 9 students 10 or more students

Type of setting

Size of school

Class size

Number of students with IEP

Number of students with Emotional Disturbance as

Students with FBA

Students with BIP Rural Fewer than 50 students Fewer than 5 students 0 students

primary disability O students

1 student 2 students 3 students 4 students 7 students 0 students 1 student 3 students 4 students 5 students 6 students 0 students 1 student 2 students 4 students 5 students

145 Number & Percentage of Respondents N = 49 (49%) N = 29 (29%) N = 22 (22%) N =8 (8%) N = 12 (12%) N = 8 (8%) N = 73 (75%) N = 11 (10.7%) N = 10 (9.7%) N = 14 (13.6%) N = 11 (10.7%) N = 27 (26.2%) N = 30 (29%) N = 32 (34%) N = 14 (13.6%) N = 14 (13.6%) N = 16 (15.5%) N = 10 (9.7%) N = 8 (7.8%) N = 72 (70%)

N = 9 (8.7%) N = 2 (1.9%) N = 5 (2.9%) N = 4 (3.9%) N = 1 (1%) N = 66 (64%) N = 12 (11.7%) N = 2 (1.9%) N = 3 (2.9%) N = 2 (1.9%) N = 1 (1%) N = 65 (63%) N = 20 (1.9%) N = 3 (2.9%) N = 5 (4.9%) N = 1 (1%)

7 students N = 1 (1%)

As noted in Tables 1 and 2, the majority of study participants were fully certified female teachers who taught in inclusive Pre-K classrooms and had obtained a bachelor’s degree. Most of the study participants taught in rural schools. The most common responses to class demographics were that teachers had two or fewer students on an IEP and no students identified with an emotional disturbance. In addition, most classrooms did not include students with a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) or Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP).

Research Instrument

To address the research questions, an online survey was developed and pilot tested. The survey asked demographic questions, as well as teachers’ experiences with aggression in the classroom. In addition, the survey asked about teachers’ use of positive behavior support systems for prevention and intervention.

Data Collection Procedures

Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the invitation to participate in the study, informed consent, and a link to the online survey were sent to the preschool directors in four Texas ESCs. The information was then forwarded via email to the study participants by the preschool staff at the ESCs. Potential study participants had the opportunity to participate in the survey or to decline participation. After three weeks, the researcher asked the ESC preschool directors to send an email reminding potential respondents of the invitation to participate in the study.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data collected, a multiple linear regression analysis was used. A multiple linear regression analysis is a technique that utilizes several predictor variables in the prediction of one criterion variable (Hinkle et al., 2003). To determine the correlation between demographic characteristics and teacher usage of evidence-based interventions, the researchers ran an analysis of variance (ANOVA), a technique to analyze one independent variable that has multiple levels (Hinkle et al., 2003). In the present study, the independent variable was the teachers’ usage of the evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies. A significance level of .05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Respondents were asked to report the frequency with which they utilize evidence-based interventions in their classrooms (see Table 3). The respondents were given the options of “never”, “monthly”, “weekly”, and “daily.” Both the frequency function and a multiple linear regression were used to analyze these data. The majority of respondents reported collaborating with parents and families on a weekly basis and engaging in other interventions daily. The only intervention that the teachers reported using infrequently was FBAs.

Table 3 Teacher’s Self-Reported Usage of Evidence-Based Interventions

Intervention N Mode

146

Median

Collaborating with families Teaching expectations Rewards and praise Adaptations to classroom Pre-correction Redirection Teaching new skills Teaching social strategies Using FBA 87

89 89 88

86 87 89 89

87 Weekly

Daily Daily Daily

Daily Daily Daily Daily

Never Weekly

Daily Daily Daily

Daily Daily Daily Daily

Monthly

A regression analysis (Table 4) was used to further analyze the teachers’ use of evidence-based interventions. The beta coefficients indicate there is no significant correlation between the teachers’ demographic variables and teachers’ likelihood of using evidence-based interventions. The coefficients are closer to 0 than to 1, indicating a weak relationship between the variables, which means we cannot predict teachers’ likelihood of using evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies based upon their demographic data.

Table 4 Regression Analysis of Teacher Usage of Evidence-Based Interventions

Intervention R R Sum of Df Mean square Squares Square

Collaborating with .624 .389 35.786 13 2.753 families Teaching ----- ----- ----- ----- ----expectations Rewards and praise .622 .387 38.065 13 2.928 Adaptations to .650 .422 44.194 13 3.400 classroom Pre-correction .611 .373 41.071 13 3.159 Redirection .665 .442 43.367 13 3.336 Teaching new ----- ----- ----- ----- ----skills Teaching social ----- ----- ----- ----- ----strategies Using FBA .508 .258 32.782 13 2.522

F

2.943

3.011 3.425

2.700 3.653 -----

1.635

Significance

.002

.002 .001

.005 .000 -----

.100

The researchers had hypothesized that there would be a correlation between teacher demographics and teachers’ self-reported usage of evidence-based intervention. However, there was no statistically significant correlation between teacher variables (teacher age, type of teaching position, type of teaching certification, level of education and number of years of teaching experience) and intervention usage. The significance levels for the relationship between teacher age and the interventions appear to be significantly correlated; however, further analysis using the beta test results indicates that it is not significant. 147

The study also examined the relationship between school variables (school type, school district location, and the number of students in the school) and the use of evidence-based intervention and prevention strategies; the results indicate no statistically significant correlations between school variables and intervention usage. Finally, the study investigated the relationship between class variables and teachers’ self-reported use of evidence-based interventions. The initial results indicate statistically significant correlations between the number of students in the class and the use of each intervention. However, further analysis of the beta coefficients of the regression analysis indicate that the correlations are not actually significant.

Discussion

The data revealed that there are no statistically significant correlations between any of the teacher or school demographic variables and the teachers’ likelihood of using evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies; however, preschool teachers report engaging in effective behavior management strategies on a regular basis. Low variance in teachers’ demographics could have resulted in the lack of a statistically significant correlation between the demographics and the use of effective strategies (Ravid, 2011).

Implications for Teacher Preparation

Having an understanding of preschool teachers’ usage of evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies may guide teacher training for both pre-service and practicing early childhood educators. The data accrued in the present study has some implications for future preschool personnel preparation. The data indicate that teachers are utilizing best practices in behavior management, which supports the current teacher training efforts in early childhood education. Based on the results of the present investigation, state certified preschool teachers indicate they are implementing evidence-based behavior interventions in their classrooms. These data signify that either pre-service or in-service teacher trainings are effectively meeting the needs of preschool teachers regarding learning evidence-based behavior management strategies. It is important to note that the results of the present study are contrary to other research, which has indicated that teachers are unprepared for behavior management (Freeman et al., 2013). This discrepancy may be due to the self-report nature of the present study.

In addition, the data suggest that preschool teachers may not fully understand the terms “functional behavior assessment” and “behavior intervention plan” as evidenced by respondents who responded that no students in their classrooms had a FBA, but also reported having students with a BIP. Through examining individual survey responses, the researchers noted that some survey respondents reported students with a FBA, but no BIP, and other respondents noted students with a BIP, but no FBA. Teacher educators must ensure that all future teachers, both general and special educators, are familiar with special education terms and their proper usage.

Future Research

There is much potential for future research in the area of teacher preparedness for managing aggression and teacher usage of evidence-based interventions. The first recommendation is to conduct a similar study on a larger scale, using teachers from different parts of the country. This information may help determine if the results are representative of teachers outside of the state of

148

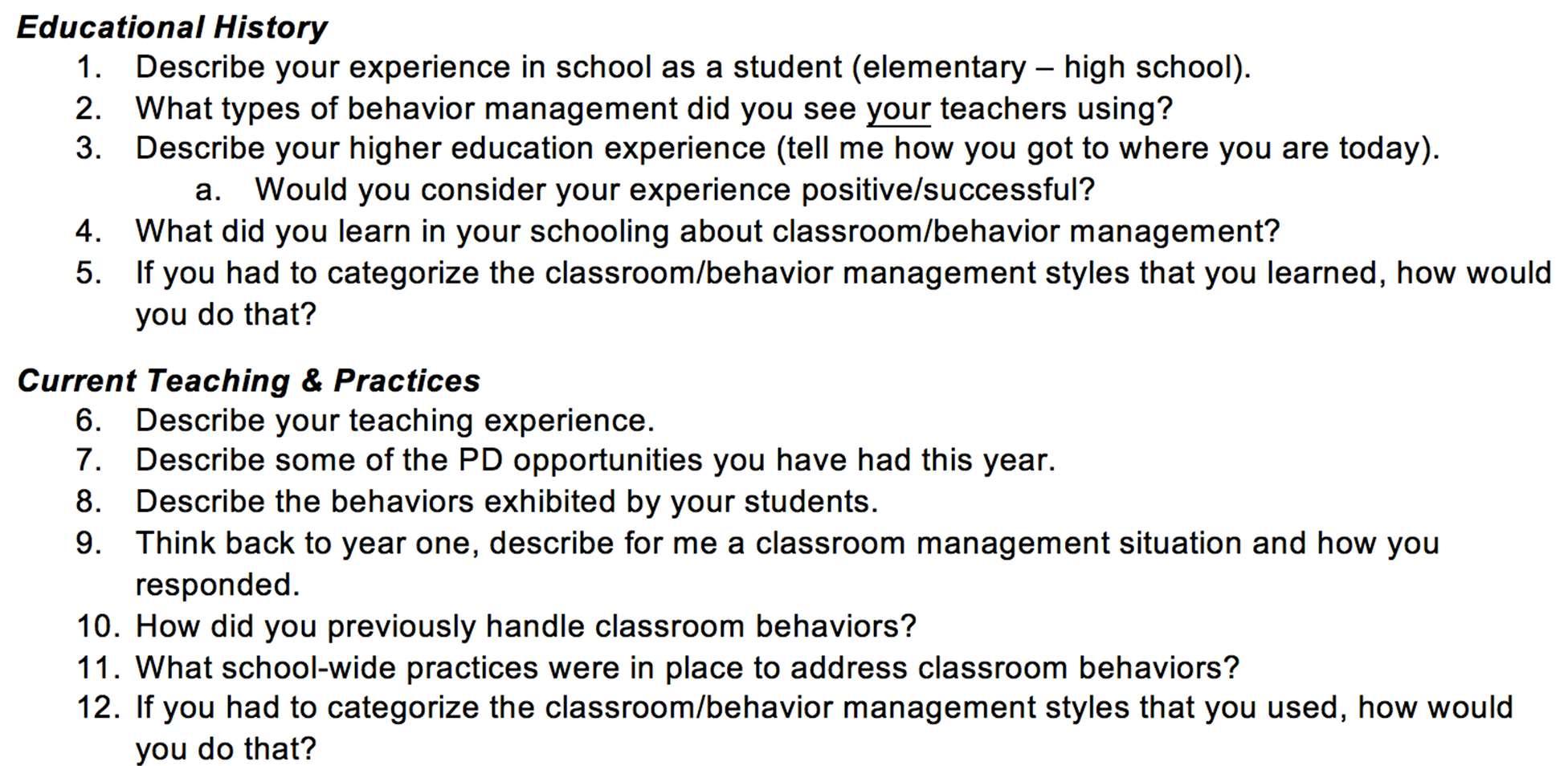

Texas. Additionally, a replication study with uncertified teachers in private childcare settings is also recommended. The results of that study will identify if there is a difference between preschool teachers with and without certification, as well as whether teaching in a public school versus a private center impacts teachers’ usage of evidence-based interventions. A third recommendation is to conduct a qualitative study, using either interviews or focus groups. More specific data about how and when preschool teachers are using interventions can likely be gleaned from teachers through direct interaction with them. A final recommendation is to conduct a qualitative analysis of observations in preschool classrooms to track data on teachers’ actual implementation of behavior management strategies. Direct observation in teachers’ classrooms may more accurately determine the frequency of intervention usage.

Limitations

A few limitations of this study should be noted. First, survey respondents were primarily state certified teachers and were working in the public school system; this is not representative of all preschool teachers. Second, the survey relies on self-reporting, which may not provide an accurate assessment of the level of implementation. Finally, the sample size was small and may not provide a good representation of all teachers. Despite the limitations, the present study provides valuable information that may support preparation for both pre-service and in-service preschool teachers.

References

Bellone, K. Dufrene, B., Tingstrom, D., Olmi, D., & Barry, C. (2014). Relative efficacy of behavioral interventions in preschool children attending Head Start. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(3), 378-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-014-9196-6 Blair, K.C., Umbreit, J., & Eck, S. (2000). Analysis of multiple variables related to a young child’s aggressive behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(1), 33-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070000200105 Booster, G.D., Mautone, J.A., Nissley-Tsiopinis, J., VanDyke, D., & Power, T.J. (2016). Reductions in negative parenting practices mediate the effect of a family-school intervention for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review, 45(2), 192-208. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR45-2.192-208 Brotman, L.M., Gouley, K.K., Huang, K., Rosenfelt, A., O’Neal, C., Klein, R.G., & Shrout, P. (2008). Preventive intervention for preschoolers at high risk for antisocial behavior: Long-term effects on child physical aggression and parenting practices. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(2), 386-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410801955813 Carbonneau, R., Boivin, M., Brendgen, M., Nagin, D., Tremblay, R., & Tremblay, R.E. (2016). Comorbid development of disruptive behaviors from age 1 ½ to 5 years in a population birth-cohort and association with school adjustment in first grade. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(4), 677-690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0072-1 Carter, M.A., & Ellis, C. (2016). Work ‘with’ me: Learning prosocial behaviors. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 41(4), 106-114. Centers for Disease Control. (2018). School violence: Data & statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/youthviolence/schoolviolence/data_stats.html. Dunlap, G., Strain, P.S., Fox, L., Carta, J.J., Conroy, M., Smith, BJ., Kern, L., Hemmeter, M. L.,

149

Timm, M. A., McCart, A., Sailor, W., Markey, U., Markey, D. J., Lardieri, S., & Sowell, C. (2006). Prevention and intervention with young children’s challenging behavior: Perspectives regarding current knowledge. Behavioral Disorders, 32(1), 29-45. Evertson, C., Emmer, E.T., & Worsham, M.E. (2000). Classroom management for elementary teachers (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon. Fox, L., Dunlap, G., Hemmeter, M.L., Joseph, G.E., & Strain, P.S. (2003). The Teaching Pyramid: A model for supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Children, 6(4), 48-52. Fox, L., & Little, N. (2001). Starting early: Developing school-wide behavior support in a community preschool. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(4), 251-254. Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Briere, D.E., & MacSuga-Gage, A.S. (2013). Pre-service teacher training in classroom management. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37(2), 106-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413507002 Fullerton, E., Conroy, M., Correa, V. (2009). Early childhood teachers’ use of specific praise statements with young children at risk for behavioral disorders. Behavior Disorders, 34(3), 118-135. Fung, A.L.C. (2018). Reducing reactive aggression in schoolchildren through child, parent, and conjoint parent-child group interventions: An efficacy study of longitudinal outcomes. Family Process, 57(3), 594-612. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12323 Gottfried, M.A., & Kirksey, J.J. (2017). “When” students miss school: The role of timing of absenteeism on students’ test performance. Educational Researcher, 46(3), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17703945 Haydon, T., & Kroeger, S.D. (2016). Active supervision, precorrection, and explicit timing: A high school case study on classroom behavior. Preventing School Failure, 60(1), 70-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2014.977213 Heo, K.H., Cheatham, G.A., Hemmeter, M.L., & Noh, J. (2014). Korean early childhood educators’ perceptions of importance and implementation of strategies to address young children’s social-emotional competence. Journal of Early Intervention, 36(1), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815114557280 Hester, P.P., Hendrickson, J.M., & Gable, R.A. (2009). Forty years later-The value of praise, ignoring, and rules for preschoolers at risk for behavior disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 32(4), 513-535. Hinkle, D.E., Wiersma, W., & Jurs, S.G. (2003). Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. Huesmann, L.R., Dubow, E.F., & Boxer, P. (2009). Continuity of aggression from childhood to early adulthood as a predictor of life outcomes: Implications for the adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent models. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 136-149. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20300 Isbell, R., & Exelby, B. (2001). Early learning environments that work. Gryphon House. Kendziora, K. (2004). Early intervention for emotional and behavioral disorders. In R.B. Rutherford, M.M. Quinn, & S.R. Mathur (Eds.), Handbook of research in emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 327-351). Guilford Press. LeGray, M., Dufrene, B., Mercer, S., Olmi, D., & Sterling, H. (2013). Differential reinforcement of alternative behavior in center-based classrooms: Evaluation of pre-teaching the alternative behavior. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22(2), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9170-8 150

Malinauskaite, A. (2010). Prevention of behaviour disorders by stimulating social and emotional competences in pre-school age children: The German experience. Special Education, 22(1), 160-169. Pahl, K.M., & Barrett, P.M. (2007). The development of social-emotional competence in preschool-aged children: An introduction to the Fun FRIENDS program. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counseling, 17(1), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.17.1.81 Powell, D., Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2006). Prevention and intervention for the challenging behaviors of toddlers and preschoolers. Infants and Young Children: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Special Care Practices, 19, 25-35. Ravid, R. (2011). Practical statistics for educators (4th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. Scott, T.M., Park, K.L., Swain-Bradway, J., & Landers, E. (2007). Positive behavior support in the classroom: Facilitating behaviorally inclusive learning environments. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 3(2), 223-235. Sharma, R.N., Singh, S., & Geromette, J. (2008). Positive behavior support strategies for young children with severe disruptive behavior. The Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 9(1), 117-123. Smerillo, N.E., Reynolds, A.J., Temple, J.A., & Ou, S. (2018). Chronic absence, eight-grade achievement, and high school attainment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Journal of School Psychology, 67, 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.11.001 Stormont, M., Lewis, T.J., Beckner, R., & Johnson, N.W. (2008). Implementing positive behavior support systems in early childhood and elementary settings. Corwin Press. Stormont, M.A., Smith, S.C., & Lewis, T.J. (2007). Teacher implementation of precorrection and praise statements in Head Start classrooms as a component of a program-wide system of positive behavior support. Journal of Behavioral Education, 16, 280-290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-007-9040-3 Tiano, J. D., Fortson, B. L., McNeil, C. B., & Humphreys, L. A. (2005). Managing classroom behavior of head start children using response cost and token economy procedures. Journal of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention, 2, 28-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0100298

About the Author

Marla J. Lohmann, PhD is an Associate Professor of Special Education at Colorado Christian University and teaches in the fully online master’s of Education in Special Education program. Dr. Lohmann’s research interests include classroom management in preschool and kindergarten classrooms, best practices in the inclusive preschool classroom, Universal Design for Learning in the higher education classroom, and best practices in online teacher preparation.

151