24 minute read

Special Education Providers: Survey of Caseload Numbers, HQT, and Instructional Settings Patricia Prunty 1

Special Education Providers: Survey of Caseload Numbers, HQT, and Instructional Settings

Patricia Prunty Ed.D. Bowling Green State University

Advertisement

Abstract

There is a dynamic shift in providing educational services for students with disabilities. The need to understand the services provided by special education personnel drove this research. This work the duties and roles of both special education teachers and paraprofessionals in five Ohio counties. In this geographical region, 669 special education professionals were invited to participate in the survey, and 28% participated in the study. In the paraprofessionals subgroup only 12% had associate degrees in education, and the other 88% had little or no formal training in education. Intervention specialists reported that half of their day is spent in a special education classroom setting, while paraprofessionals report only 12% of their day in a special education classroom. Surprisingly, paraprofessionals are providing the most support for students with disabilities in inclusive settings.

Keywords: Special education personnel, paraprofessionals, caseloads, HQT, instructional setting

Special Education Providers: Survey of Caseload Numbers, HQT, and Instructional Settings

In the search for optimal learning settings, schools have placed more students with disabilities in general education classrooms. The crux of meeting the needs of the student with disabilities then requires educational supports, accommodations, and modifications in the general education classroom setting. The need for more educational assistance is apparent in inclusionary classrooms. More adults to assist students with disabilities is required in the classroom, and paraprofessionals are placed in inclusionary settings to address these needs. The United States Department of Education determined that the national average is close to one paraprofessional for every special educator (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2017). The employment rate of special education teachers has remained steady in the last twenty years; however, the employment rate of paraprofessionals has risen steadily both in Ohio and nationally.

Assistants for students with disabilities have many titles such as paraprofessionals, classroom assistants, one-on-one-aides, or paraeducators. This paper will refer to these providers as paraprofessionals. Dependence on paraprofessionals to deliver educational supports for students with disabilities has become more apparent in Ohio and in the United States as a whole. The primary support for students with disabilities are paraprofessionals in school settings (Fisher & Pleasant, 2012). Seventy-four percent of instruction is provided by paraprofessionals for students with moderate or severe intellectual disabilities (Suter & Giangreco, 2009).

Paraprofessionals do not have the same educational training and background as interventionists. Other studies have documented that paraprofessionals lack the training needed to support students with disabilities, and on the job-training is the norm in most school districts nationally (Fisher & Pleasants, 2012; Carroll, 2001). On the job workshops, trainings, and meetings suggest that professional development for paraprofessionals is sporadic, unstructured, and does not 95

address best practices. What is more surprising, many paraprofessionals are not given any professional training on the job (Carter et al, 2009).

Students with disabilities are not accessing the general education curriculum in consistent or equitable ways (Olsen, Leko, & Roberts, 2016). Due to the lack of available special education teachers to co-teach in the general education classroom, the paraprofessional’s role often develops into more of a caretaker in the general education classroom. Paraprofessionals are the primary support for students with disabilities in general education classrooms (Fisher & Pleasants, 2012). The general education teacher becomes responsible for all parts of the educational lesson, including the scaffolding and differentiation pieces to meet the needs of special education and at-risk learners. This educational arrangement allowed the students with disabilities to remain in the general education classroom, but without intensive instructional supports they need.

It is plausible that special education teachers spend less time assisting students with disabilities due to other professional responsibilities. The role of the special education teacher continues to become more focused on managerial tasks and less on high-quality instruction. Suter and Giangreco’s study on Service Delivery in Inclusionary Schools concluded changes need to be made in practices that are compatible with inclusion. Too many special educators report caseloads that make it difficult for them to apply their knowledge and skills for the benefit of students with disabilities (Suter, & Giangreco, 2009). The focus to place students in general education classes is the priority, and remediation and interventions to meet the individual needs of the child may become less of the main concern.

Morningstar, Kurth, and Johnson (2017) researched access of students with cognitive disabilities to general education settings and determined time spent in learning settings during the school day. Their research also states learners with multiple disabilities access to the general education classroom has made little progress in the last decade (Morningstar, Kurth, & Johnson, 2017). IDEA does not require all students with an IEP be placed in an inclusionary setting. IDEA builds upon older legislation that does require students with disabilities to be placed in Least Restrictive Environments (LRE). School districts must educate students with disabilities in the regular classroom with appropriate aids and supports with their nondisabled peers (IDEA, 20 USC Chapter 33, Subchapter II, 2004). The Reauthorization of IDEA in 2004 encouraged inclusionary practices based on LRE.

Special education services are dependent on a foundation that the identified student will receive specially designed instruction in areas of need. The IEP is written to identify needed areas of instruction for an individual student. The push for inclusionary settings has had unintended effect of less specially designed instruction. Most students with disabilities will not learn to read, write or calculate if they are not explicitly taught these skills (Zigmond, 2003). Specially designed explicit instruction may be better suited to a resource room or tutoring setting than a general education classroom. The desire for an inclusive setting may not be the best educational environment for all instruction for students with special needs. IDEA states that schools must offer students with disabilities a continuum or range of services from more to less typical and inclusive: that is, from least to most restrictive or separated from the regular education classroom. IDEA does not require that a student with a disability be placed in a general 96

education classroom, but the general education classroom should be the first consideration with appropriate supports and services.

Research Questions

1. According to special education personnel in Ohio, who is serving our special education students, and what instructional settings are special education personnel serving students?

2. According to special education personnel in Ohio, how many students are being served, which students are being served?

Method

Quantitative methods were used to examine the work roles paraprofessionals and special education teachers hold when serving students with disabilities. Data was collected between January and March 2018 from service providers for students with disabilities, after approval from the IRB at Bowling Green State University.

Data Collection & Analysis

Bowling Green State University uses the secure research platform called the secure Qualtrics Survey System for collecting and analyzing survey data. Qualtrics invited participants (special education teachers and paraprofessionals) through email. The email invitation contained a description of the purpose of the study, contact information of the researcher, and the participants’ responses would be confidential. Possible participants were also informed that participation was voluntary, and that the survey could be stopped at any time. If needed, participants could skip questions completely or return to them at the end of the survey.

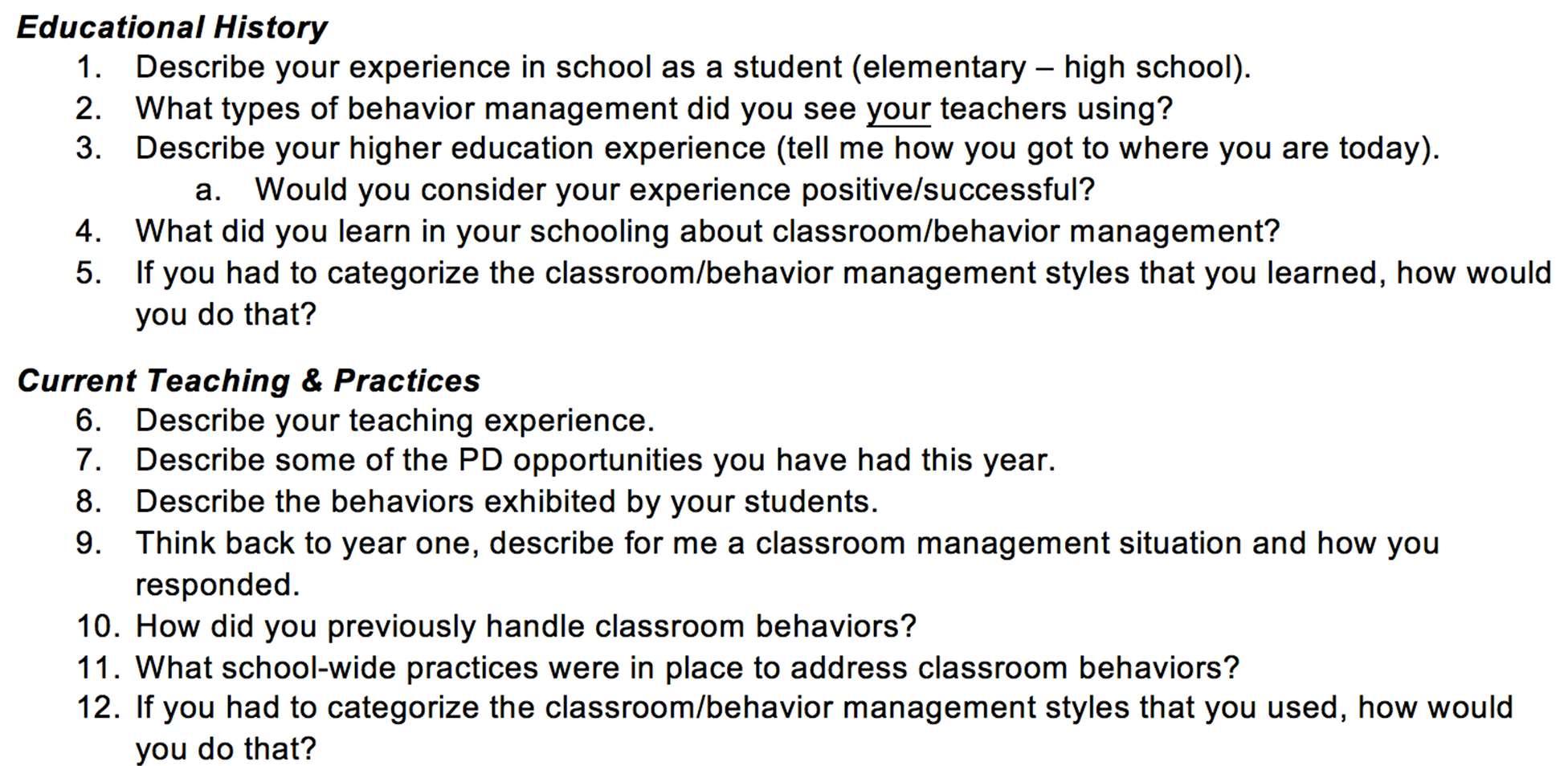

Qualitative data was compiled through the process of descriptive statistics and analytical deduction (Fink, 1995). The Qualtrics system compiled and analyzed the results using secure software systems. The survey data was analyzed using statistics, mathematical collections, and interpreting of such data (Fink, 1995). The questions came from two sources. The first article recently published by this researcher entitled, Special Education Personnel: Who is serving special education students in Ohio? The second piece or research used was by Howley, Howley, and Telfer in 2010 called Special Education Professionals in District Context.

Setting

The sample for this analysis is composed of special education personnel in five counties in northern Ohio located between Cleveland and Toledo, which included thirty-one school districts. The researcher was granted permission from the BGSU IRB to survey special education teachers and paraprofessionals in these five counties. In the ten-question survey, the researcher asked questions about the setting, the number of students served, and the professional backgrounds of special education teachers and paraprofessionals.

Participants

The school districts in the geographical area selected by the researcher invited 669 special education personnel (teachers and/or paraprofessionals) to complete the survey. Of these surveys, 185 were opened and answered, but some surveys were not complete due to questions 97

being skipped or partially answered. Twenty-eight percent of invited participants answered the survey. The participants were 62% special education teachers and 38% paraprofessionals or oneon-one assistants. Of these participants, 75% worked in a public-school setting, 21% percent worked in an educational service center, and 4% are employed in a community, charter or private school setting.

Data Analysis & Results

Research Question #1

According to special education personnel in Ohio, who is serving our special education students, and in what instructional settings are special education personnel serving students?

Then survey participants consisted of 62% special education teachers and 38% paraprofessionals or one-on-one assistants. Twenty-eight percent of invited participants answered the survey. The five school districts in the geographical area selected by the researcher invited 669 special education personnel (teachers or paraprofessionals) to complete the survey. 185 surveys were opened and answered, but some surveys were not complete due to questions being skipped or partially answered.

The researcher asked about educational backgrounds of special education personnel. Special education interventionists reported that 99% have earned bachelors or graduate degrees. Paraprofessionals reported that 54% have earned only a high school diploma, 12% have earned an associate degree in education, and the 20% have an associate degree in other fields. The remaining 14% hold degrees higher than an associate degree. These numbers are distressing, because, the majority of paraprofessionals, classroom assistants, and one-on-aides are not trained in education. Despite federal laws like NCLB, IDEA, and ESSA addressing highly qualified special education personnel, 88% of paraprofessionals lack any formal training in education according to this survey. They are providing academic and behavioral assistance to students without training in educational pedagogy, behavioral systems, special education, or child development. These paraprofessionals are getting on the job training to serve special education learners. The types of training and professional development were not assessed.

Table 1 Education levels of Special Education Teachers and Paraprofessionals Interventionists Para-pros One-on-One Paras/Aides Aides together High School Diploma 0% 52% 60% Associates Degree 0% 11% 13% in Education

Associates Degree in another Field 01% 26% 07% 54% 12%

20%

Bachelor’s Degree Graduate Degree 37% 62% 06% 06%

98 13% 07% 08% 06%

Table 1 identifies education levels of special education intervention teachers and paraprofessionals and one-on-one assistants or aides. The final column is the data for any paraprofessional or classroom assistant added together regardless of assignment working with children with disabilities. The percentages were determined for special education teachers in each category by dividing by total teacher participants.

Federal laws have attempted to define the qualifications for paraprofessionals. According to IDEA (34 F R 300.136(f)) a state may allow paraprofessionals/assistants that are appropriately trained and supervised to assist in the provision of special education and related services to students with disabilities. In 2002, NCLB further defined, a paraprofessional must have an associate degree or a secondary degree diploma and/or its equivalent to serve students with disabilities. NCLB directly mandated that paraprofessionals must work under the supervision of a certified special education teacher. Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) 2015 requires that the state educational agency will ensure that all paraprofessionals working in a program supported with funds under Title I, Part A meet applicable state certification requirements (Section (1111 (g) (2) (J)). ESSA requires that each state has professional standards in place for paraprofessionals including qualifications that were in place on the day before the date of enactment of Every Student Succeeds Act (United States Department of Education, 2016).

The Ohio Department of Education issues three types of permits for assistants. The one-year student monitor permit is for non-instructional assistants to supervise playgrounds, lunchrooms, and other duties. This permit requires a high school diploma. The educational aide one-year permit requires a high school diploma. The four-year educational aide permit requires a high school diploma and successful completion of two one-year educational aide permits. Education assistants are required to meet HQT qualifications stated in The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) which requires schools receiving Title I funds to add the designation ESEA Qualified, one of two requirements must be successfully completed. The classroom assistant or paraprofessional must pass the ETS ParaPro assessment or complete an associate degree (Ohio Department of Education, 2016).

Special education teachers need to be highly qualified to serve students with disabilities. Federal legislation defines highly qualified in both No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and IDEA 2004. IDEA (2004) requires special education teachers instructing academic subjects must be highly qualified to teach that subject area or areas. Each state sets caseload limits for special education service providers. The state’s caseload requirements also require all the state and federal paperwork for students with disabilities be completed by the special educator.

Table 2 Location of Services Provided by Special Education Personnel _ Special Educators Classroom Paras General Education Classroom 18% 22% Special Education Classroom 48% 24% Small Group Settings 0% 8% 99 One-on-One 53% 12% 0%

Combination of Settings 34% 46% 35% ____________________________________________________________________________ Table 2 determined the location of services provided by education special education personnel. Each category of provider was to identify the educational setting that the provider spent majority of time during their work day. The percentages were calculated by dividing the responses per category of educational providers.

When special education personnel were asked where they provided the majority of their services, the responses varied among special education teachers, paraprofessionals and one-on-one aides. Forty-eight percent of special education teachers spend most of their day in special education classrooms, while 24% of classroom assistants and one-on-one aides spend only 12% of their day in special education classrooms. Only 18% of special education teachers reported spending the majority of the day in inclusionary general education classrooms, and 34% reported spending their time in a combination of both special education and general education classrooms. Paraprofessionals spend 22% of their time in the general education classroom and 46% in a combination of the two settings. Fifty-three percent of one-on-one aides report spending the majority of their day in the general education classroom setting, while 35% report most of their day in a combination of settings.

The apparent conclusion is that paraprofessionals and one-on-one aides are providing most of the support to students with special needs in general education classes. While nearly half of all special education teachers report only spending half or less of their day in general education classes. Paraprofessionals are providing academic and behavioral supports but have the least amount of education and training in education. Nearly eight out of ten learners with disabilities are in the general education classroom setting for more than 80% of the school day in 2015-2016 (ODE, 2017). This data determines that students with disabilities are receiving more educational support services from paraprofessionals or classroom assistants than special education teachers.

Research Question #2

According to special education personnel in Ohio, how many students are being served, which students are being served?

Table 3 Number of Students Assigned to Work with Educational Setting_ Interventionists Para-pros One-on-One Aides Paras/Aides All

1 student 0% 0% 23% 07%

2-8 students 24% 45% 65% 51%

8-16 students 38% 29% 06% 22%

More than 16 students 38% 26% 06% 20% ______________________________________________________________________________ 100

The researcher determined the percentages for each category of special education providers and in the last column both types of paraprofessionals calculated together. The percentages for paraprofessionals, one-on-one aides or assistants were calculated by the responses divided by the participants in each category.

In previous research, this author studied special education personnel ratios in these five counties in Ohio and compared the data with state data (Prunty, 2018). These results led the researcher to further study of the numbers of students that special education professionals served daily in schools in these same counties. When asked how many special education personnel served only one student, it was reported that 23% of one-on-one aides only serve one student. This type of paraprofessional is hired to work with one student with a significant disability, but only 23% only work with that student exclusively. No other subgroup reported working with only one learner with special needs.

Many special education units can serve no more than eight learners. The survey asked special education personnel served two to eight students, 24% percent of special educators, 45% of paraprofessionals, and 65% of one-on-one aides reported working this number of students. Thirty-eight percent of special educators, 29% of paraprofessionals, and 6% of one-on-one aides reported working with eight to sixteen students daily. When asked who served more than sixteen students daily, 38% of special education teachers, and 26% of paraprofessionals work with more than sixteen learners with special needs every day.

Specially designed instruction occurs in three settings: the general education classroom, the special education classroom, and small groups in a variety of settings. The service delivery and program structures dictate the responsibilities of the special educator and paraprofessionals. Historically, special education classrooms grouped students with similar disabilities for educational units. Appropriate placement and services for students with disabilities have been discussed in schools and courts. When special education services began in Ohio, the state philosophy was to separate handicapped children from regular classes and peers (US Department of Education, 1987). LRE was part of PL-94-142, required students to be placed in settings with non-disabled peers. Funding for special education services from the federal and state governments was distributed by special education units. Currently in Ohio funding is based on per-pupil formula, but Ohio’s laws set caseload limits for special education teachers based upon age and disability category of the learners.

The Ohio Operating Standards for the Education of Children with Disabilities, which are found in Ohio Administrative Code Rules 3301-51-01 to 09, 11 and 21, became effective on July 1, 2014. These operating standards outline the laws regarding caseloads for special education providers in Ohio. The standards call for a caseload dependent on category of disability, ages of students, the number of students receiving direct instruction and caseload number of students. For example, Ohio Administrative Code 3301-51-09:2 lists caseload specifications, “a special education teacher serving students with multiple disabilities shall have no more than eight students with ages less than 60 months apart and the assistance of a paraprofessional”. (Ohio Administrative Code 3301-51-09-2e, 2014). The highest acceptable caseload is 24 at the high school level with no more than 16 students during an instructional period. The smallest caseload 101

is six students with Autism, TBI, or deaf-blindness. Ohio law sets caseloads for other providers such as speech-language therapists, school psychologists, adapted physical education teachers, and other related service personnel.

These numbers are staggering because they imply that special education personnel workloads are significantly higher than the caseloads mandated by law. The workload for special education teachers and related service providers is outlined by Ohio Administrative Code (3301-51-09(1). In 2017, the Ohio Department of Education released a memo entitled Service Provider Ratio and Workload Clarification. This memo defined workload and caseload for special education personnel. The memo strongly urged school administrators to review specially designed instruction for students with disabilities in Ohio’s schools. No Child Left Behind, limits the duties and responsibilities of paraprofessionals. “A paraprofessional may not provide instruction to any student unless the paraprofessional is working under the direct supervision of a teacher according to NCLB” (US Department of Education, 2016). Nearly 80% of all special education teachers serve more than eight students daily, and 25% of them report working with other at-risk students in addition to their special education caseload.

Discussion

Implications

After reviewing the conclusions from the research questions, two major points stand out in this research. First students with disabilities are not receiving most of their specially designed instruction from highly qualified teachers. Interventionist specialists spend a great deal of time on other types of work, such as paperwork, training of paraprofessionals, and progress monitoring. Caseloads for all special education personnel are stretched to capacity.

Second, paraprofessionals appear to be providing the majority of academic and behavior instruction in both the general education and special education classroom settings. More paraprofessionals have been hired while the hiring of intervention specialists has remained stagnant in the last decade in Ohio and the nation. Special education teachers reported that they spend less than 20% of their workday in inclusionary settings, yet paraprofessionals spend nearly 90% in inclusionary settings. Paraprofessionals are providing more instructional and behavior services and supports in inclusionary settings. The impact of paraprofessionals delivering instruction needs to be studied.

Limitations

Several limitations are noted by the researcher in this survey. More interventionists than paraprofessionals or one-on-one aides completed the survey. Several surveys were only partially completed were from paraprofessionals, while all teachers completed the survey. The researcher wonders if educational jargon limited the completion of the survey. Some surveys had one only question skipped, while others had several skipped. Another limitation is the online access of paraprofessionals. Some paraprofessionals are hired by educational service centers or educational temporary agencies and may have several email addresses. The researcher may not have had access to the email address that these professionals use daily. Furthermore, a survey specifically designed to meet the needs of paraprofessionals, classroom assistants, and one-onone aides might be the best way to gather data from these special education providers. 102

Further Study

The role of the special education teacher and paraprofessionals has continued to be changed to fit more inclusionary settings. Special education policies have driven major changes in the structure of special education programming. This directly impacts all special education providers and the roles of special education interventionists with varying role changes to meet the needs of students with disabilities.

Special education providers have suggested a wide variety of service models and options to provide instruction to students with disabilities. One area of further research is to further explore is the professional development provided to paraprofessionals. The clear majority of these providers have no training in education. Only 12% held an associate degree in education and 54% had only graduated from high school. The training to work with students with disabilities is occurring on the job.

Does the lack of training in academic interventions, social skills, and behavior directly impacts students with disabilities? Paraprofessionals lack training in evidence-based practices to promote learning. Poor instruction can intensify behavior issues for students with disabilities. Behavior issues often interfere with learning in inclusionary settings (Harrison, Bunford, Evans, & Owens, 2013). Untrained paraprofessionals are more likely to provide poor instruction and poor-quality instructional supports, therefore, providing unaccommodating assistance and are not equipped to handle the behaviors that arise during instruction. The impact of instructional services and supports by paraprofessionals is virtually unknown. However, the Ohio Department of Education evaluates school districts in special education indicators to determine districts’ effectiveness and testing results in educating students with disabilities. From the Ohio Department of Education’s 2015-2016 Special Education Profiles for districts, gathered data from the same five counties. Areas of need were graduation rates for students with disabilities, reading, and math proficiency scores, and service placement options. More than half of these districts did not meet requirements in students with IEPs passing reading assessments. According to the ODE, to meet these requirements, 24.18% of students with IEPs in any district needed to pass the reading proficiency tests (ODE, 2017). Yet, in this area, only 48% of districts could meet this requirement. More than half of the districts do not have one-fourth of students with disabilities reading on grade level (ODE, 2017).

The correlation between employing less special education teachers and more paraprofessionals have on academic outcomes of students with disabilities. Further study in this area would include a closer examination of instructional and remediation practices for students with disabilities in academic areas by all special education providers. The biggest question remains does instruction provided from an intervention specialist yield higher results for closing the gaps in academics for students with disabilities?

References

Carlin, C., Watt, L., Fallow, W., Carlin, E., & Vakil, S. (2013). Caseload ratio study: Final report to the Ohio Department of Education (pp. 1-233, Rep.). Columbus, OH: ODE. Retrieved

103

from: https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Special-Education/WorkloadCalculator/Caseload-Ratio-Study-Report.pdf.aspx Carter, E. W., O’Rourke, L., Sisco, L. G., Pelsue, D. (2009). Knowledge, responsibilities, and training needs of paraprofessionals in elementary and secondary schools. Remedial and Special Education, 30, 344–359. doi:10.1177/0741932508324399 Deardorff, P., Glasenapp, G., Schalock, M., & Udell, T. (2007). TAPS: An innovative professional development program for paraeducators working in early childhood Special Education. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 26(3), 3-15. doi:10.1177/875687050702600302 Downing, J. E., Ryndak, D. L., & Clark, D. (2000). Paraeducators in inclusive classrooms. Remedial and Special Education, 21(3), 171-181. doi:10.1177/074193250002100308 Etscheidt, S. (2005). Paraprofessional services for students with disabilities: A legal analysis of issues. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30(2), 60-80. doi:10.2511/rpsd.30.2.60 Fink, A. (1995). The survey kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Fisher, M., & Pleasants, S. L. (2011). Roles, responsibilities, and concerns of paraeducators. Remedial and Special Education, 33(5), 287-297. doi:10.1177/0741932510397762 Giangreco, M. F., & Broer, S. M. (2005). Questionable utilization of paraprofessionals in inclusive schools. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(1), 10-26. doi:10.1177/10883576050200010201 Giangreco, M. F., Suter, J. C., & Hurley, S. M. (2011). Revisiting personnel utilization in inclusion-oriented schools. The Journal of Special Education, 47(2), 121-132. doi:10.1177/0022466911419015 Hamad, C. D., Serna, R. W., Morrison, L., & Fleming, R. (2010). Extending the reach of early intervention training for practitioners: A preliminary investigation of an online curriculum for teaching behavioral intervention knowledge in autism to family and service providers. Infants and Young Children, 23, 195–208. Harrison, J.R. Bunford, N., Evans, S., & Owens J.S. (2013). Educational Accommodations for Students with Behavioral Challenges. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 551-597. Doi:10.3102/0034654313497517. Howley, Howley, and Tefler. (2010). Special education paraprofessionals in district context. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 29(2), 136-165. IDEA, 20 USC CHAPTER 33, SUBCHAPTER II (2004), Retrieved from http:// uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title20/chapter33/subchapter2&edition Morningstar, M. E., Kurth, J. A., & Johnson, P. E. (2017). Examining national trends in educational placements for students with significant disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 38(1), 3-12. DOI: 10.1177/0741932516678327 National Association of Private Special Education Centers (2016). Continuum of alternative placements and services. Retrieved from http://www.napsec.org/booklet.html#continuum National Center for Education Statistics (2017). The Condition for education: Teacher and pupil teacher ratios Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_clr.asp Ohio Department of Education (2014). Ohio operating standards for children with disabilities. Retrieved from http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Special104

Education/Federal-and-State-Requirements/Operational-Standards-and-Guidance/2014Ohio-Operating-Standards-for-the-Education-of-Children-with-Disabilities.pdf.aspx Ohio Department of Education (2017). ODE-OEC MEMO #2016-2: Service provider ratio an workload clarification. Retrieved from https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Special-Education/Service-Provider -Ratioand-Workload-Calculation/2016-2-3-ODE-OEC-Memo-2016-2-Service-Provider-Ratioand-Workload-Clarification.pdf.aspx Ohio Department of Education (2017). Educational aides and student monitor work permits Retrieved from http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Teaching/Licensure/Apply-forCertificate/License/Educational-Aides-And-Monitors#Aide Ohio Department of Education (2017). FY2016 district profile report Retrieved from http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Finance-and-Funding/School-Payment-Reports/DistrictProfile-Reports/FY2016-District-Profile-Report Prunty, P. (2018). Special Education Personnel: Who is serving special education students in Ohio? Special Education Research, Policy & Practice 2(1) 176-190. Qualtrics Survey Platform. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.Qualtrics/com/research/core Suter, J. C., & Giangreco, M. F. (2008). Numbers that count. The Journal of Special Education, 43(2), 81-93. doi: 10.1177/002246690731335 United States. Department of Education. (1987). History of special education in Ohio 1803-1985. SuDocED 1.310/2:331206 United States Department of Education. (2010). Paraprofessionals employed (FTE) to provide special education and related services to children ages 6 through 21 under IDEA, Part B by qualifications and state: Fall 2010 [Data file]. United States Department of Education (2016). Special education paraprofessionals. Retrieved from www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/edfacts/eden/non-xml/c112-13-0.doc United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). May 2016 state occupational employment and wage estimates Ohio Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_oh.htm United States Department of Education (2017). Every student succeeds act Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/esea Vannest, K. J., Hagan-Burke, S., Parker, R. I., & Soares, D. A. (2011). Special education teacher time: Use in four types of programs. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(4), 219230. doi:10.1080/00220671003709898 Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 319-356. doi:10.3102/0034654313483905 Woodcock, S., & Hardy, I. (2017). Probing and problematizing teacher professional development for inclusion. International Journal of Educational Research, 83, (2) 43-54. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.008 Zigmond, N. (2003). Where should students with disabilities receive special education services? The Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 193-199. doi:10.1177/00224669030370030901

About the Author

105

Dr. Patricia (Trisha) Prunty Ed.D. is an assistant professor at Bowling Green State University's Firelands campus in the Inclusive Early Childhood Education program. Currently, Dr. Prunty serves on two advisory committees at the Ohio Department of Education for exceptional children and is the Vice President of her local school board. She also does volunteer work advocating for children in foster care. Dr. Prunty is married to her husband, Scott, with seven children and three grandchildren.

106