27 minute read

Special Education Law in the United States of America and the Sultanate of Oman Maryam Alakhzami and Morgan Chitiyo

Special Education Law in the United States of America and the Sultanate of Oman

Maryam Alakhzami, Ph.D. Candidate Morgan Chitiyo, Ph.D.

Advertisement

Duquesne University

Abstract

During the last decade, Oman has embarked on massive reforms of the country’s education system. Although the law in Oman mandates education for all children, individuals with disabilities still encounter difficulties in accessing appropriate education. Oman lacks adequate formal and structured systems of special education, which could be addressed with a comprehensive legal framework such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in the United States. IDEA reflects the United States’ concern regarding how individuals with disabilities are treated as full citizens with the same educational rights and privileges as their peers without disabilities. In its efforts to promote the educational rights of individuals with disabilities, Oman could learn from the United States experience. This paper therefore, explores the special education legislation in the United States and Oman. Doing so may provide a benchmark for Oman to establish her own legal instruments to promote sustainable development of her special education system.

Special Education Law in the United States of America and the Sultanate of Oman

Oman is a developing country located in the Middle East with a population of 4,687,839 people (National Centre for Statistics and Information, 2019). Since 1971 the country has witnessed rapid expansion of its education system. The rates of school enrollment increased from 900 students in 1970 to over 600,000 students in 2008/2009 representing around 70% of the total population (Ministry of Education & The World Bank, 2012). In 1998, a new basic education system was introduced to provide a unified program for grades 1 to 10, and in 2007, a new postbasic education system organized on a “core plus electives” model was introduced for grades 11 and 12 to improve the quality of education in Oman. Both reforms focus on changing the teaching profession, reducing class sizes, upgrading the qualifications and skills of teachers, updating the curriculum, adding new resources, and enhancing learning and assessment methodologies (Ministry of Education & The World Bank, 2012). Accordingly, the education participation levels in Oman are equivalent to or above other countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). According to data from the Ministry of National Economy (2011), there were 62,506 individuals with disabilities in 2010 representing 3.2% of the total Omani population; this number could have increased since then but there is no updated official data available after 2010. The individuals with disabilities fall into six recognized disability categories in the country including visual impairment, hearing impairment, physical disability, memory and attention deficits, cognitive impairments (i.e., intellectual disabilities), and communication disorders (speech and/or language impairments) (Ministry of National Economy, 2011). Obviously, there is need for the country to invest in special educational programs.

The last 40 years have been a period of rapid development in Oman, not only in terms of education but also economically and socially (Ministry of Education & The World Bank, 2012). In the mid 1990s, Oman witnessed greater focus on ensuring access to education for all students and reforming the educational system was made a national priority to enable the country to transform into a knowledge-based economy (Ministry of Education, 2008). The educational policies in Oman are drawn based on the fundamental principles directed by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos, the ruler of the country, and in conjunction with other social and economic policies adopted by the government (UNESCO, 2010). The Ministry of Education is accountable for executing the education policy via ministerial and administrative decisions and circulars, declaring the educational objects and setting up the strategies to realize the objectives of the national education policy (UNESCO, 2010).

Efforts to expand the provision of specialized educational services to students with disabilities in regular school settings and the introduction of professional development programs in the area of special education are ongoing and gaining momentum (Ministry of Education, 2008). Despite the continuous attempt to reform education in Oman and the government’s efforts to promote education, the illiteracy rate among individuals with disabilities is considered to be significantly high compared to that of the population without disabilities (Al-Balushi, Al-Badi, & Ali, 2011). According to the 2003 census results, 75% of people with disabilities were uneducated (Ministry of National Economy, 2010). This highlights that Oman still encounters some challenges in relation to providing special education services for individuals with disabilities, which might be attributed to absence of a national policy specific to special education.

The Rationale

The purpose of this paper is to review the status of the national laws and policies related to special education in Oman. In doing this, the authors drew specific examples from special education legislation in the United States. The authors chose to do this for a couple of reasons. First, the United States has a long-established experience of special education programs and the underlining special education law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which was enacted in 1975 as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act made provision of special education compulsory for every child diagnosed with a disability (Friend & Bursuck, 2015). IDEA was enacted to ensure states met the individual learning needs of children with disability and guaranteed that all children, regardless of their differences, had access to free public-school education (Dunn, 2013). Since the passage of the law, notable progress had been achieved toward meeting the educational needs of individuals with disabilities in the United States. Therefore, other countries including Oman could learn from the United States experience and use that experience to develop their own legal instruments. Secondly, IDEA is a comprehensive piece of legislation, which covers almost every aspect of the special education process including funding, identification/diagnosis, placement, assessment, curriculum, access, service delivery, parental involvement, among others. Understanding the principles of IDEA therefore, helps to promote a holistic framework for the development of special education. Finally, Oman lacks adequate formal and structured systems of special education, which could be addressed with a comprehensive legal framework such as IDEA. Oman could therefore, benefit from using the United States legislation as a benchmark to develop and expand its special education services provision and delivery for individuals with disabilities.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in the United States

IDEA is a civil rights law that serves as a foundation to provide assistance to more than 6.5 million children in the United States schools and ensures a free, appropriate public education for children with disabilities (American Psychological Association, 2011). Infants and toddlers with disabilities from birth to two years of age and their families receive early intervention services under IDEA Part C, and children and youth from three to 25 years of age receive special education and related services under IDEA Part B (American Psychological Association, 2011). The principles that IDEA introduced have remained fundamentally unaltered since 1975 (Heward et al., 2017). These principles, which will be described later, are (1) free appropriate public education, (2) zero reject (3) nondiscriminatory evaluation, (4) individualized education (5) least restrictive environment (LRE), and (6) parent participation and due process (Friend & Bursuck, 2015).

Special Education Legislation in Oman

On April 22nd , 2008, Oman issued the first legislation related to individuals with disability when the Disabled Persons Welfare and Rehabilitation Act (the “Law”) was issued via Royal Decree No. 63/2008. Subsequently, Oman ratified the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) through the Royal Decree No. 121/2008, which was issued on November 5th , 2008 (Mohamed Emam, 2016). The UNCRPD calls for removal of all the restrictions to the education of individuals with disabilities and the provision of early intervention services within an inclusive setting from an early age; however, Oman did not adopt the UNCRPD appeals (Mohamed Emam, 2016).

A number of ministerial decisions were issued to ensure compliance with Oman’s obligations under UNCRPD and maintenance of consistent government policies under the law. These regulations include establishment of rehabilitation centers by Ministerial Decision No. 124/2008, promulgation of the rules governing issuance of status cards for people with disability by Ministerial Decision No. 94/2008, and establishing National Committee of Disabled Persons Welfare by Ministerial Decision No. 1/2009. The Ministry of Social Development is the entity accountable under the law to advocate for the rights of persons with disability. However, despite the huge leap forward achieved by the education sector in Oman, a number of challenges still exist including improving the quality of student learning outcomes, in particular for students with disabilities (World Bank, 2012). Also, Oman does not have a formal structured system for identifying and evaluating children with disabilities, and it is likely that the true requirement for special needs education provision is higher than what is currently available (World Bank, 2012).

The Six Principles of IDEA and how They Compare to the Law and Regulations in Oman Free Appropriate Public Education

In the United States, students with disabilities regardless of the type or severity of their disability, are entitled to attend public schools and receive educational services that have been specially designed to meet their unique needs at no cost to their parents (Friend & Bursuck, 2015; Heward et al., 2017). In Oman, equality in accessing education has been recognized as one of the highest priorities by the government of His Majesty Sultan Qaboos. His Majesty the Sultan directed that all Omanis would be treated equally before the law and would receive equal rights

and opportunities. The Basic Statute of Oman, the constitution, states that one of the social principles is that the State guarantees aid for the citizen and family in cases of emergency, sickness, disability, and old age according to the social security scheme. The Basic Statute also provides that the State shall provide public education, work to combat illiteracy, and promote establishment of private schools and institution, which shall be supervised by the State in accordance with the provisions of the Law. Article 17 of the Basic Statute provides that, “All citizens are equal before the law and they are equal in public rights and duties. There shall be no discrimination between them on the ground of gender, origin, color, language, religion, sect, domicile or social status” (Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 47). Accordingly, the Ministry of Education in Oman announced its commitment that “all children must have access to education, regardless of their gender, social status, cultural group or area of residence” (Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 47). However, this commitment statement failed short of stating disability status as a factor that should not hinder access to education. Although education in Oman is free up to the end of high school (Ministry of Education, 2008), most of the public schools in Oman remain inadequately prepared to provide educational services to students with disabilities (Mohamed Emam, 2016). This is contrary to the provision of Article 7 of the Law, which provides that the State shall provide educational services to individuals with disabilities in a manner that addresses their sensory, physical, and cognitive capabilities (Ministry of Legal Affairs, 2008). These services are now mostly provided by private centers. Provision of free and appropriate public education in Oman is hindered by absence of evidence-based practices in teaching, limited consideration for the role of parents, and the necessity of in-service training, research, provision of assistive aids, and improvement of the quality of services (Alfawair & AlTobi, 2015). Additionally, the Law states that the obligations of the Ministry and other government agencies wherever mentioned in this Law should be within the limits of the funds included in the country's general budget (Ministry of Legal Affairs, 2008). As such, this limitation could prevent provision of appropriate special education instruction to students with disabilities.

Individualized Education Programs (IEPs)

In the United States, all students who are eligible for special education and related services must receive an individualized education program (IEP; Bateman & Cline, 2016). An IEP should be written for each student identified as having a disability and should include a primary plan section and instructional guide to help teachers in planning and providing ongoing educational activities (Jaffe & Snelbecker, 1982). An IEP is developed by a multidisciplinary team and must include measurable annual goals and short-term objectives for the student (Wolfe, & Harriott, 1998). IDEA stresses the need for comprehensive IEPs that serve as useful working documents, which include behavior management plans, transition plans, related services, and any necessary accommodations and/or modifications. IDEA also emphasizes the importance of teacher training, which should take place at both preservice and in-service levels and provided by specially trained staff (Wolfe, & Harriott, 1998).

In Oman, the Ministerial Decision No. 2/2006 provides the legal framework to implement what is called “Self-management in all Public Schools”, including special education schools, in order to equip such schools to take their own decisions on administrative, financial, and technical issues. The central aim of the concept of self-management in schools is to delegate more responsibilities to the schools and their employees in planning, implementation, and follow-up of

activities as well as in introducing programs to enhance school performance (UNESCO, 2010). The Law in Article 5 states that individuals with disabilities have the right to receive preventive and curative care as well as rehabilitation and adjustment devices that help them with mobility (Ministry of Legal Affairs, 2008). Yet both private and public schools in Oman lack the resources necessary to provide related services, community-based rehabilitation services (CBR; Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015), and services related to rehabilitation and vocational employment services that are offered only to adults with disabilities by the Ministry of Social Development through Alwafaa centers (Ministry of Social Development, 2008). Also, the law does not explicitly make it mandatory to have an individualized education program for students with disabilities. As already indicated, schools at local levels are authorized to make decisions in regard to certain issues related to students' education, including mainstreaming students with disability (Ministry of Education, 2008).

It should be highlighted that education is compulsory for all children and youth in Oman (UNESCO, 2004), and the Ministry of Education is responsible for developing the national curricula that is taught in all public schools (Ministry of Education, 2008). According to the Ministry of Education, the school curriculum should be relevant in its content to the age, background, and cognitive level of the learners (UNESCO, 2004). However, this does not necessarily include individualized education programs for individuals with disabilities. Students with disabilities are mostly educated in separate institutions/schools and the practice in mainstream schools is using the general curriculum for all students in the classroom regardless of whether they have a disability or not. As such, little attention is given to the provision of differentiated instruction or individualized education plans to meet diverse learners’ needs (Ministry of Education, 2008).

Nondiscriminatory Evaluation

In the United States, students should be assessed using a battery of instruments that do not discriminate based on race, culture, or disability (Friend, & Bursuck, 2015). The IEP team has numerous responsibilities in the evaluation and reevaluation processes (Wolfe, & Harriott, 1998). In Oman, the Law, in Article 3 states that the State shall work to prepare specialists in the area of disability and to train them to ensure early detection of disability and to provide appropriate assistance and services to people with disability (Ministry of Legal Affairs, 2008).

In spite of the clear and unequivocal mandate of the Law, there are limited early detection services, if any, in Oman. Therefore, most of the children with disabilities are placed in segregated special schools/centers (Ministry of Education & World Bank, 2012). Additionally, the Law does not explicitly address the need to have a comprehensive assessment/evaluation administered by a multidisciplinary team for children who might be identified as having disability. The Ministry of Education has developed a standardized battery of diagnostic tests to identify children who might have learning disabilities. A national team has been formed to formulate these instruments and provide teachers and school psychologists on applying these assessment tools and interpret their results to plan and develop appropriate programs to improve learning outcomes for their students (Ministry of Education, 2008). However, these standardized tests are mostly translated from English and are not based on scientific research that considers the cultural relevance of such tests. Therefore, one of the major concerns in Oman is availability of culturally sensitive assessment and diagnostic services (Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015). Currently,

the Ministry of Health in Oman administers its own medical-based tests to diagnose disability; but there are many private centers that provide assessment and diagnosis for disabilities though the outcomes of such assessment are not recognized by government bodies (Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015).

Zero Reject

In the United States, IDEA requires schools to educate all children with disabilities; no child with disabilities should be excluded from free public education on account of type or severity of disability (Heward et al., 2017). Although education in Oman is free from grade 1 to 12 (Ministry of Education, 2008), several factors could limit the admission of students with disabilities in public or private schools including the inadequate facilities to provide educational services to students with disabilities (Mohamed Emam, 2016), the shortage of qualified Omani special education teachers (Ministry of Education, 2008), and the lack of awareness among parents and families in the Omani society about the right of children with disabilities to be fully included in their communities (Ministry of Education, 2008). These factors limit the full participation of children with disabilities in both school and social activities and events. Schools usually refuse to accept students with disabilities and end up referring them to segregated settings such as special needs centers/schools/institutions (Ministry of Education & World Bank, 2012). There is no law to stop schools from denying admission to students on account of their disability. As such, schools end up discriminating individuals with disability.

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

In the United States, schools are obligated to educate children with disabilities with children without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate; children with disabilities can only be placed in separate environments, from their peers without disabilities, when the nature or severity of their disabilities is such that they may not benefit from instruction in a general classroom with supplementary aids and service (Heward et al., 2017). According to IDEA students with disabilities must not be placed in self-contained special classes or schools without access to their peers without disabilities unless it is the appropriate choice for them (Friend & Bursuck, 2015). Therefore, school districts should offer a continuum of alternative placements such as the regular classroom with consultation, resource room, special class, and special schools (Heward et al., 2017).

In Oman, the system does not support a continuum of alternative placements and service alternatives in public or private schools for individuals with disability. However, the country is attempting to integrate individuals with disabilities into mainstream schools and provide them with daily living skills to reduce the impact of their disability and improve their functioning (Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015). Unfortunately, these efforts are scattered and inconsistent because of the absence of a national policy; but the Ministry of Education began implementing integration programs in 2000/2001 resulting in students with learning disabilities, hearing impairment, and intellectual disabilities being integrated into the regular schools (Alfawair & AlTobi, 2015).

Special needs education programs in Oman are split into two—special education schools and mainstream schools (Omanuna, 2018). According to the National Center of Statistics and Information (2017), the number of public schools providing integration for students with

disabilities reached 218 schools in 2017, in addition to the three government special education schools. Public schools have not yet made full transition towards full inclusive education for all students (Mohamed Emam, 2016). A framework for action has not yet been developed and thus the assumption is that inclusive education systems require a long time to be implemented on a large scale (Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015; Mohamed Emam, 2016). However, currently, there are plans for more legislation in order to promote the inclusion of students with disabilities in regular schools (Mohamed Emam, 2016).

Parent Participation and Due Process

In the United States, parents have the right to equal participation with teachers and to be part of the decision-making team for determining eligibility for special education services as well as the placement and LRE of their children (Friend & Bursuck, 2015). The parents’ and students' (whenever appropriate) suggestions/comments and goals need to be considered in preparing IEP goals, placement decisions, and related-service needs (Heward et al., 2017). When disagreements occur concerning a student's eligibility for special education, the student's educational placement, or the services that a student receives, IDEA provides a specific set of informal and formal procedures that need to be followed to resolve the disagreements through the due process provision (Friend & Bursuck, 2015).

In Oman, there seems to be no legislation guaranteeing participation of parents in the educational process of their children with disabilities. Parents of children with disabilities usually have limited information or lack of awareness about their rights and those of their children (Ministry of Education, 2008). Considering that special education services are not comprehensively defined in the Basic Statue of Oman and the Law, caregivers do not have a clear reference point of the standard against which special education services are to be delivered, which results in people with disabilities being unable to enjoy their educational rights on an equal basis with their peers without disabilities (United Nations, 2018). In addition, there is no law in Oman that guarantees parents' rights to contest any aspect of their children’s special education services delivery (United Nations, 2018). Please see Table 1 for a brief overview of this comparison of special education legislation in Oman and the United States.

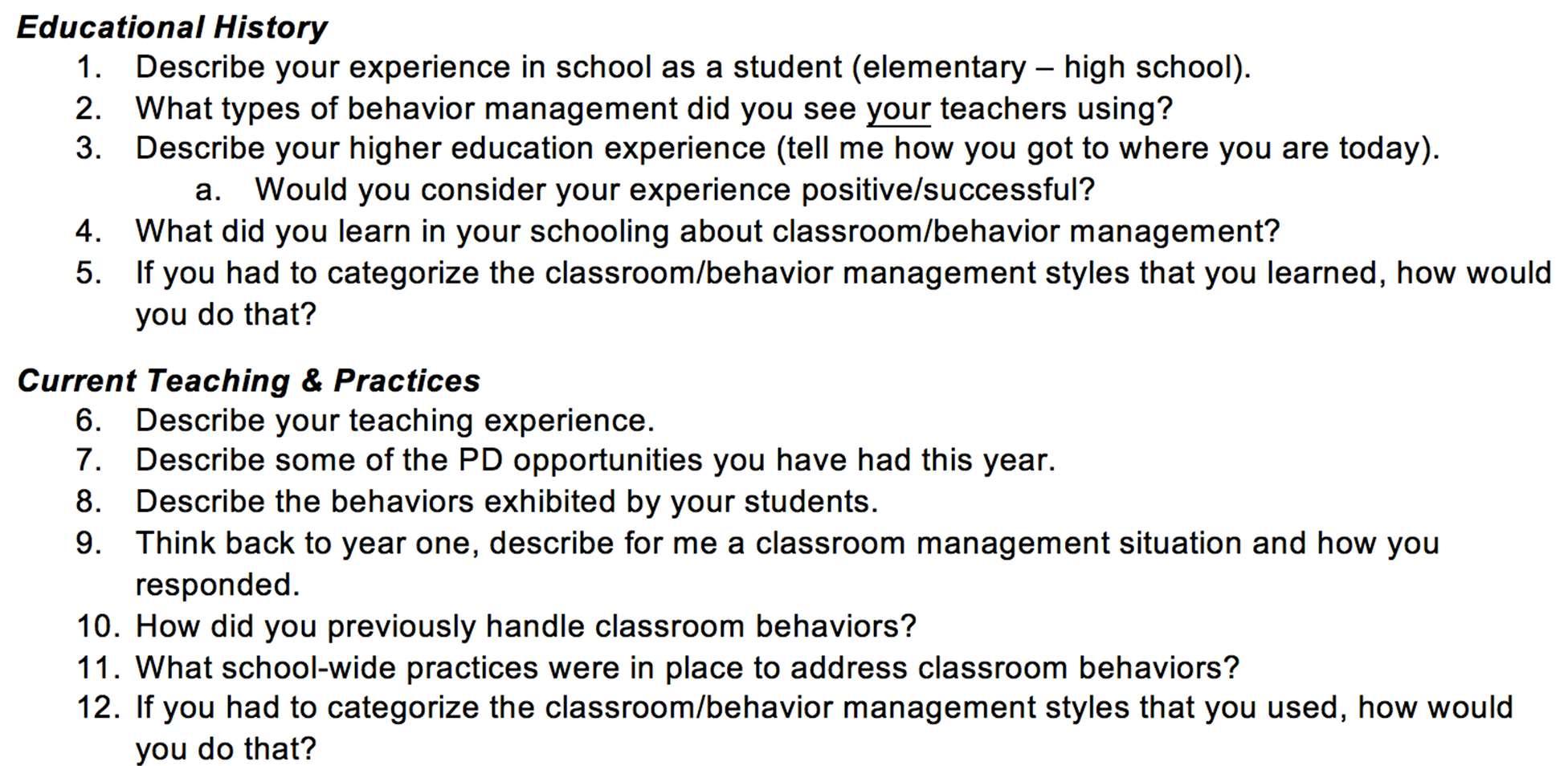

Table 1 The Six Principles of IDEA and Special Education Regulations in Oman The Six Principles of IDEA Free Appropriate Public Education USA Regulations/IDEA

Students with disabilities regardless of the type or severity of their disability, are entitled to attend public schools and receive educational services that have been specially designed to meet their unique needs at no cost to parents Oman Regulations

Equality in accessing education has been recognized by the Basic Statute of Oman. All children must have access to education, regardless of their gender, social status, cultural group or area of residence

Nondiscriminatory Evaluation Students should be assessed using a battery of instruments that do not The Disabled Persons Welfare and Rehabilitation Act 2008, in Article

Zero Reject

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

Parent Participation & Due Process discriminate or result in discrimination based on race, culture, or disability

Schools are required to educate all children with disabilities. No child with disabilities should be excluded from free public education on account of the type or severity of their disability.

Schools are obligated to educate children with disabilities with children without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate and children with disabilities need to be removed to separate environments when the nature or severity of their disabilities is such that they may not benefit from instruction in a general classroom with supplementary aids and services

Parents have the right to equal involvement and to be part of the decision-making team for determining eligibility for special education services as well as the placement of their children. Parents are protected by procedural safeguards; when disagreements occur concerning a student's eligibility for special education, the student's educational placement, or the services that a student receives, (3) of the Law provides that the State shall work to prepare specialists in the area of disability and to train them to ensure early detection of disability and to provide appropriate assistance and services to people with disability. The Ministry of Education is responsible for assessment and LRE for students.

Although education in Oman is free from grade 1 to 12, there is no national policy that ensures that schools are not denying admission to students with disability.

There is no flexible system to support continuum of alternative placements and service alternatives in public or private schools for individuals with disability. There is no national policy that promotes full inclusion in regular schools and classrooms; however, the Ministry of Education is implementing partial integration programs (selfcontained classrooms) for students with hearing impairment, learning and intellectual disabilities.

There is no law in Oman that guarantees the parents' rights to contest any aspect of their children’s special education services. Parents of children with disabilities usually have limited information and awareness about their rights and those of their children

Individualized Education Programs parents have the right to demand due process hearing

All students who are eligible for special education and related services must receive an individualized education program (IEP). An IEP is developed by a multidisciplinary team and must include measurable annual goals, short-term objectives, and provide ongoing educational activities for the student The Law in Article 5 states that individuals with disabilities have the rights to receive preventive and curative care as well as rehabilitation and adjustment devices that help them with mobility. However, the law does not explicitly make it mandatory to have an individualized education program for students with disabilities. Schools at local levels are authorized to make decisions in regard to certain issues related to students' education, including mainstreaming students with disability

Discussion and Recommendations

Education is a foundation for the progress of a society and states shall promote and endeavor to expand and make education accessible to all (UNESCO, 2010). In the United States, IDEA has significantly impacted what happens in every school building in the country and has changed the roles and responsibilities of general and special educators in terms of serving children with disabilities (Heward et al., 2017). IDEA was enacted to ensure that schools and families learn how best to serve children with disabilities (Friend & Bursuck, 2015) and this has resulted in significant improvement in the special education delivery process in the country. In Oman, increasing equality to educational access has been a highest priority for the government. Although all public and private schools in Oman are making efforts to provide comprehensive services to individuals with disabilities, there is still need to develop a legal framework that promotes sustainable development of special education in the country.

A national policy for special needs education must be developed to establish the scope of authority and accountability of various ministries and government bodies. In addition to this, enforcement of the currently existing laws and regulations is essential to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities to free appropriate special education, related services, and rehabilitation/vocational services. For example, in the United States, IDEA’s zero-reject principle allows provision of education to all students with disabilities, and protects their rights against practices that could diminish their right to have a free appropriate public education (Turnbull, 2005). Achieving such a goal in Oman requires that relevant authorities develop a comprehensive piece of legislation that guarantees and protects such rights.

Furthermore, in the United States, IDEA requires that schools educate children with disabilities with children without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate and that children with

disabilities need to be removed to separate environments when the type or severity of their disabilities prevents them from benefiting from instruction in a general classroom with supplementary aids and service (Heward et al., 2017). Though it is the policy in Oman to promote participation of individuals with disabilities in the educational system, inclusion of individuals with disabilities into the education system remains a challenge. Thus, enacting laws that provide mandatory access to education may be the most effective way to achieve accessibility to appropriate education for all individuals with disabilities in Oman. This will enable individuals with disabilities to have full access to school by providing them with appropriate accommodations and modifications to their educational programs in the LRE. Providing every child with disability with an individualized and appropriate education/intervention plan is an essential step to be taken by Oman to warrant its citizens the right to education as provided in its Basic Law.

Conclusion

IDEA completely changed the face of special education in the United States (Heward et al., 2017). Undoubtedly, IDEA is considered a core part of the education reformation in the United States (Yell et al., 1998); it reflects the country's concern in regard to how individuals with disabilities are treated as full citizens with the same rights and privileges as any other citizen (Heward et al., 2017). Oman needs to learn from this experience in its efforts to promote the educational rights of individuals with disabilities.

During the last decade, Oman has embarked on massive reforms of the country’s whole education system (UNESCO, 2004); the country is working to address the parallel matters of adult education, education of people with disabilities, pre-school education, gender and regional equity with regard to quality and access, along with the issues related to the quality and efficiency of the education system (Ministry of Education & The World Bank, 2012). Although the law in Oman mandates education for all children, individuals with disabilities still encounter difficulties in accessing appropriate education/services. The Government of Oman is making substantial efforts to meet these challenges; however, these efforts are considered insufficient and need to be reconsidered in any future plans (Alfawair & Al-Tobi, 2015).

References

Al-Balushi, T., Al-Badi, A. H., & Ali, S. (2011). Prevalence of disability in Oman: statistics and challenges. Canadian Journal of Applied Sciences, 1, 81-96. American Psychological Association. (2011). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/advocacy/education/idea/index.aspx Bateman, D. F., & Cline, J. L. (2016). A teacher's guide to special education. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development. Dunn D. (2013). Public Law 94-142. In: Volkmar F.R. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders (pp. 99-139). New York, NY: Springer. Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, Pub. L. No. 94-142. 89 Stat. 773. Retrieved from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-89/pdf/STATUTE-89Pg773.pdf

Etscheidt, S., & Curran, M. C. (2010). Reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA, 2004): The peer-reviewed research requirement. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 21(1), 29 -39. Friend, M. P., & Bursuck, W. D. (2015). Including students with special needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Heward, W. L., Alber-Morgan, S. R., & Konrad, M. (2017). Exceptional children: An introduction to special education (11th ed.) Boston, MI: Pearson Education. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2015). About IDEA. Retrieved from: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/ Jaffe, M.J. & Snelbecker, G.E. (1982). Evaluating individualized educational programs: A recommendation and some programmatic implications. The Urban Review, 14(2), 73–81. Ministry of Education. (2008). Inclusive Education in the Sultanate of Oman: National report of the Sultanate of Oman. Retrieved from: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/National_Reports/ICE_2008/oman_NR08.pdf Ministry of Education, & World Bank. (2012). Education in Oman: The drive for quality. Retrieved from www.moe.gov.om Ministry of Education Portal. (2011). Special Education. Retrieved from: http://portal.moe.gov.om/portal/sitebuilder/sites/EPS/Arabic/MOE/specialedu.htm Ministry of Legal Affairs. (2008). Legislation. Retrieved from: http://www.mola.gov.om/mainlaws.aspx?page=9 Ministry of National Economy. (2010). Oman Census Results 2003. Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. Ministry of National Economy. (2011). Disability Statistics in the Sultanate of Oman: The experience of data collection during 3 censuses, (1993, 2003, 2010). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/citygroup/meeting11/wg11_session6_2_al-dagheishi.pdf Ministry of Social Development. (2008). Laws and regulations for the care and rehabilitation of disabled people. Retrieved: http://www.mosd.gov.om/rules_disable.asp Mohamed Emam, M. (2016). Management of inclusive education in Oman: A framework for Action. Support for Learning, 31, 296-312. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.12139 National Center of Statistics & Information (2017). Education. Retrieved from: https://data.gov.om/OMEDCT2016/education?regions=1000000oman&indicators=1000080-number-of-schools&lang=en National Centre for Statistics and Information. (2019). Oman Population. Retrieved from https://www.ncsi.gov.om/Pages/NCSI.aspx O’Connor, E., Yasik, A. E., & Horner, S. L. (2016). Teachers’ knowledge of special education laws: What do they know? Insights into Learning Disabilities 13(1), 7-18. Omanuna. (2018). Disabled Children. Retrieved from: http://www.oman.om/wps/portal/index/cr/childcare/disabledchildren/ Simpson, R. L. (1995). Reauthorization of the individuals with disabilities education act: Effects on children and youth with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 10(5), 16 -19. Turnbull, H. R. III. (2005). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act reauthorization: Accountability and personal responsibility. Remedial and Special Education, 26(6), 320326. UNESCO. (2004). Education as a motor for development: Recent education reforms in Oman with particular reference to the status of women and girls. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001411/141188eo.pdf

UNESCO (2010). World data on education: Oman. Retrieved from: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/sites/default/files/Oman.pdf U.S. Department of Education. (1997). IDEA'97 Speeches-Remarks by the President. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/leg/idea/speech-1.html Wolfe, P. S., & Harriott, W. A. (1998). The reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA): What educators and parents should know. Focus on Autism and Other Development Disabilities, 13(2), 88-93. World Bank. (2012). Education in Oman: the drive for quality. Washington DC: World Bank. Retrieved from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/280091468098656732/Mainreport Yell, M., Rogers, D., & Rogers, E. (1998). The legal history of special education: What a long strange trip it's been. Remedial and Special Education, 19(4), 219-228.

About the Authors

Maryam Alakhzami is a Ph.D. candidate in Special Education-Autism Spectrum Disorder at Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Her research interests include applied behavior analysis, autism, challenging behaviors, self-injurious behaviors, functional communication training, severe disabilities, and inclusive education.

Dr. Morgan Chitiyo is Professor and Department Chair of Counseling, Psychology, and Special Education at Duquesne University. His research interests include positive behavior supports, autism, inclusive education, and special education professional development in developing countries.