26 minute read

How are Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP) Conducted in Public Schools? A Survey of Educators Andria Young and Terrisa Cortines

How are Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP) Conducted in Public Schools? A Survey of Educators

Andria Young, PhD Terrisa Cortines, Med

Advertisement

University of Houston-Victoria

Abstract

The functional behavior assessment (FBA) and function-based behavior intervention plan (BIP) are integral to the success of students with disabilities experiencing behavioral challenges. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act does not provide specific guidance regarding how an FBA is conducted or how a BIP is developed, nor is their guidance about the level of training one should have. To investigate how schools are conducting FBAs and developing BIPs, a survey was conducted with public school educators. Educators were queried about the types of functional behavior assessments, whether behavior plans are based on an FBA; and the level of training of those conducting FBAs and writing and implementing behavior plans. Results show a variety of methods to conduct an FBA are utilized and behavior intervention plans are based on the results of the FBA. Educators who are integral to the assessment and implementation process are not always adequately trained.

Keywords: functional behavior assessment, behavior intervention plan, IDEA

How are Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP) Conducted in Public Schools? A Survey of Educators

Research has demonstrated that behavior intervention plans are most effective when they are based on findings from functional behavior assessments (Gable, Park & Scott, 2014, O’Neill, Bundock, Kladis & Hawken, 2015). Functional behavior assessment consists of a selection of processes designed to determine the function or purpose of behavior and identify antecedents and other environmental variables affecting behavior. The foundation of FBA lies in the idea that all behavior serves a function or purpose. There are two main functions of behavior; positive reinforcement in the form of access to activities, tangibles, attention or sensory stimulation; and negative reinforcement in the form of escape or avoidance of activities and sensory stimulation (Umbreit, Ferro, Liaupsin & Lane, 2007).

Functional behavior assessments include indirect and direct methods as well as functional analysis. Indirect assessment consists of record reviews, questionnaires, and surveys given to those familiar with the student. Rating scales and checklists are also used. Direct assessment consists of systematic direct observation of the behavior in various contexts, in the form of Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence (ABC) recording to determine the antecedents and the consequences of the behavior. Analysis of the patterns in the direct observation ABC assessment leads to a hypothesis about the function of the behavior and antecedents and other context 116

variables that affect and maintain behavior. Finally, functional analysis includes the experimental manipulation of various conditions to test hypotheses about the function of behavior (O’Neill, Albin, Storey, Horner & Sprague, 2015). A function-based behavior intervention plan (BIP) is developed based on the results of the FBA. The findings from the FBA allow practitioners to identify and alter specific aspects of the environment in which the behavior occurs. A BIP based on a functional behavior assessment will include techniques and strategies to address the challenging behavior by reinforcing replacement behaviors, altering antecedents that trigger behavior and changing the consequences of challenging behavior by withdrawing reinforcement (Umbreit, Ferro, Liaupsin & Lane, 2007).

Within the public schools, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires members of individualized education plan (IEP) teams to consider the use of positive behavior intervention and supports (PBIS) when students’ behavior interferes with their learning or the learning of others (Positive Behavior Intervention & Support, 2019). The PBIS model draws on principles from applied behavior analysis, the normalization and inclusion movement and the person centered approach. Inherent to the PBIS model are concepts and techniques from the field of applied behavior analysis such as fading, shaping, chaining and reinforcement contingencies as well as a focus on the functional behavior assessment (Carr, Dunlap, Horner, Koegel, Turnbull, Sailor, Anderson, Albin, Koegel, Fox, 2002). Within IDEA, funding is made available in the form of professional development funds to provide training to staff in order to promote the use of PBIS in the schools to enhance positive student behavior in the classroom (Positive Behavior Intervention & Support, 2019).

The adoption of PBIS does not however guarantee that an FBA will be completed prior to behavior interventions. The IDEA encourages formal functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans (BIP) for students who engage in challenging behavior but they are not required in instances where behavior interferes with learning. Von Ravensberg and Blakely (2015) indicate that the use of FBA is implied when challenging behavior interferes with learning and PBIS is being considered. However, every state has their own policies and most may follow the legal guidelines in IDEA. The decision to conduct FBAs and create BIPs is left up to the IEP team. The formal FBA and BIP are only required when behavior results in a disciplinary change of placement of 10 consecutive or accumulated days. Additionally, IDEA does not define the components of an FBA, the composition of the BIP or the level of training needed by those conducting the FBA and BIP. Districts and schools are left to develop their own processes for conducting FBAs and writing and implementing BIPs (Yell, 2016).

FBA and BIP in the Schools

Weber, Killu, Derby and Barretto (2005) set out to determine if state education agencies (SEA) in the United States had developed guidelines and resources for completing FBAs. They developed criteria for standard practice for FBA completion based on the guidance provided by the US Department of Education PBIS model. They surveyed the SEAs in all fifty states and received a response from 48. They found 41 states had guidelines for completing an FBA and seven did not. Direct observation as a means to conduct an FBA was found in the majority of state resources. Steps involved in many of the resources resembled a standardized approach to FBA and intervention that did not take into account the context of behavior. The authors also suggested that even though states had written guidelines and resources there was no guarantee 117

that individual schools and personnel were aware of the guidelines and were using them. The authors also suggested that schools may be conducting FBAs to higher or lower standards than suggested in the resources available.

Blood and Neel (2007) conducted a file review in a school district in the mid-west. They were interested in discovering whether students with Emotional/Behavior Disorders (EBD) had functional behavior assessments as well as behavior intervention plans. For those students with FBAs and BIPs they also evaluated how the documents were developed and used by teachers. They found that of 46 students in self-contained classrooms 43 had at least one behavioral goal in their IEP. Of those 43 students, 15 had a formal FBA and 14 had a behavior plan. For the 28 students who did not have an FBA, 23 had a behavior plan. They also found that the most prevalent among the BIPs was a stock list of consequences that could be chosen to follow behavior. The BIPs that were present, were not individualized and they did not include antecedent interventions. The authors also found that even those with FBAs did not have behavior plans that were individualized to their unique needs. For the FBAs themselves, assessment data came primarily from teacher interviews, with observation and rating scales used less frequently. Furthermore, teachers were not able to identify the goals in the BIP and often had their own interventions apart from the BIP and FBA on record. Blood and Neel suggested that the FBAs and BIPS were primarily compliance documents lacking individualization and implementation by personnel trained on running the specific plan.

Zirkel (2011b) analyzed state statutes and regulations to determine if regulations surrounding FBA and BIP exceeded what was in IDEA rather than just mirror it. He found 31 states with statutory or regulatory provisions for FBA and BIP that exceeded IDEA regulations; however most were very limited. For example, some states defined the FBA but not the BIP. Zirkel also found that none of the state special education laws required an FBA or BIP when behavior interferes with learning. Similarly, Collins and Zirkel (2017) evaluated what the law says must be done and what empirical evidence says should be done. They found that professional recommendations for conducting an FBA and implementing a BIP are proactive in that an FBA is conducted and behavior intervention implemented when challenging behavior first appears. In contrast, IDEA regulations are reactive, the FBA and BIP are only required when the behavior becomes so severe that it results in a change in placement for the student. Collins and Zirkel also found that professional recommendations based on the empirical research are specific regarding how an FBA and BIP should be completed. The FBA and BIP should be developed by an individualized team of professionals who are knowledgeable about the student in order to give a comprehensive picture of the student’s behavior. Members of the team should also be trained in the processes related to the various methods of FBA and writing and implementing BIPs. The FBA may include indirect and direct methods of behavior assessment and the BIP should be based on the findings of the FBA (Collins & Zirkel, 2017). In contrast, IDEA provides no guidelines for how to conduct FBA and develop BIPs nor does it designate required training for those involved in the process.

In Texas, the state in which the current research is based, there is some guidance regarding how to conduct an FBA and write a BIP using the ABC direct observation method. The Texas Education Agency provides a link to Texas Behavior Support (2019) that among other information, includes links and training related to the PBIS processes. The focus on PBIS is in 118

keeping with what Weber et al (2005) found in their study but as they suggested, does not guarantee that school districts are utilizing the processes or guaranteeing that all educators working with students with disabilities are specifically trained on the procedures. Consequently, the current authors set out to obtain information from those working in the schools regarding the FBA processes and BIP as well as the level of training of those involved. Specifically, the authors sought to discover what forms of FBA are conducted; who conducts FBA; how the behavior intervention plan is developed and whether it is based on the FBA; whether those conducting FBAs are formally trained, whether those running BIPs have training; and who monitors the BIP.

Method

Participants

The authors of the study contacted school district administrators, Education Service Center administrators, professional education organizations, and regional special education cooperative directors in South Texas asking them to send an email with a link to a survey to those educators working with students receiving special education services. The survey was hosted on Survey Monkey an online survey tool. Over two hundred educators responded to the survey with 147 completing most of the survey. Those surveys marked incomplete in Survey Monkey were deleted. For incomplete surveys the respondent typically only answered the first two questions, one providing informed consent and the other indicating their professional role. The remaining 147 surveys were included in the results analysis. Participants were asked to indicate their professional role in the schools. The participants included two regular education teachers, 42 special education teachers, 22 administrators; 12 behavior specialists (not board certified behavior analysts), 3 behavior specialists (board certified behavior analysts), 23 Licensed Specialists in School Psychology (LSSP), and 43 diagnosticians. Fifty nine percent of these worked in elementary schools; 19% worked in middle/intermediate schools and 22% worked in high schools.

Survey

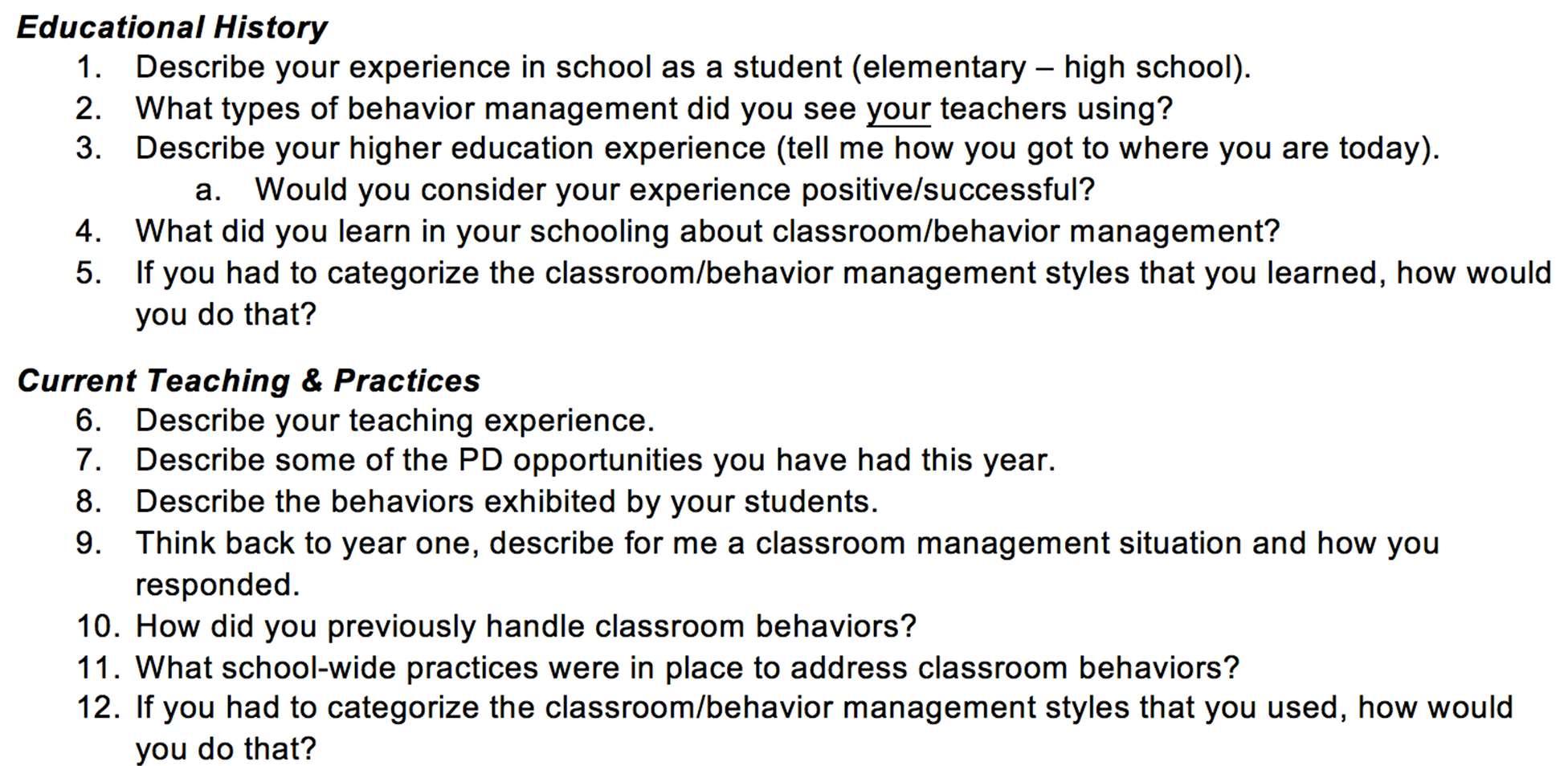

The survey was developed using Survey Monkey. Questions in the survey included demographic questions regarding the respondents’ professional position in a school and the grade level of the school in which they were employed. To determine the level of training those tasked with completing FBAs and BIPs have, respondents were asked about who conducts the FBA and develops the BIP from a choice of teacher, licensed specialists in school psychology (LSSP), Behavior Specialist, consulting Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), diagnostician and school behavior team. Respondents were also asked if behavior specialists were certified as BCBAs, LSSP or doctoral level psychologists.

The respondents were further queried about the type of FBA conducted in the school including indirect, direct (ABC) and functional analysis and how they were conducted. To determine how the behavior intervention plan (BIP) was developed and implemented a variety of questions regarding who writes the plan, the contents of the plan, training on collecting data and running the plan were asked. Finally, since many teachers are responsible for assessing behavior and writing and implementing behavior plans there was a question to determine if teachers have training in FBA and writing the BIP. The survey was developed and then piloted with educators

119

in a master’s level class offered by the first author. After feedback from the educators minor edits were made to the survey prior to sending it out to potential subjects.

Results

Professionals conducting FBA

Respondents were asked to indicate who conducts the FBA. Twenty percent indicated the behavior specialist; 53% indicated the LSSP; 3% indicated an outside consulting BCBA or psychologist; 13% indicated the school behavior team; 3% indicated the diagnostician; 6% indicated a teacher with training on FBA; and 2% indicated a teacher who has not had training on FBA.

The authors were interested in the credential for the job title of behavior specialists. Respondents were asked if there was a behavior specialist working in their school, and if the behavior specialist had some type of certification or license. Ninety-five responded to this question with 29% indicating the behavior specialist was a Board Certified Behavior Analyst. Thirteen percent indicated the behavior specialist was engaged in preparations to become a Board Certified Behavior Analyst; and twenty-seven percent indicated the behavior specialist was an LSSP or licensed psychologist. Finally, 31% indicated the behavior specialist was not licensed or certified.

Forms of FBA

Survey participants were asked to indicate the activities included in the functional behavior assessment. Activities included indirect assessments in the form of interviews or surveys, direct observation methods using the ABC descriptive approach, functional analysis or a combination of the different methods. Table 1 shows that 46% of the respondents indicated a combination of all three forms of functional behavior assessment were typically completed, with 26% indicating that the indirect and direct ABC method were the methods used for the FBA. Respondents who commented on this question indicated that the type of FBA depended on the type of student behavior. Another respondent stated that the three forms of FBA were used in the best of circumstances, but time was not always on their side, consequently it was not possible to conduct a comprehensive FBA. One respondent indicated that all three forms were completed if they were required as part of the individual evaluation by the LSSP and all other FBAs were conducted as indirect assessments.

Table 1 Types of FBAs conducted (N=143) _______________________________________________________ The functional behavior assessment consists of (choose one)_______________________

indirect assessment in the form of surveys or interviews as the only form of behavior assessment direct observation of student with collection of Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence (ABC) data to hypothesize function as the only form of behavior assessment 3%

15%

120

functional Analysis-experimental manipulation of consequences to test hypothesized function as the only form of behavior assessment a combination of indirect assessment and direct observation (ABC) a combination of direct observation (ABC) and functional analysis 2%

26%

8%

a combination of indirect assessment and functional analysis a combination of all three forms of functional behavior assessment 0% 46%

To further clarify how the FBA is conducted participants were asked whether the indirect assessment included direct interviews or surveys for stake holders to fill out on their own. The purpose behind this question was to discover whether the person responsible for conducting the FBA was getting direct information from those involved with the student in order to ask followup questions. The results in Table 2 indicate that direct interviews as well as surveys for respondents to fill out on their own were typical practice. The exception was for students. Surveys were not typically given to students to fill out on their own. Comments indicated that students were not given surveys primarily because not all students were able or willing to complete surveys on their own.

Table 2 Types of Indirect FBA (N=144) ______________________________________________________________________________ When an indirect assessment is completed as part of the FBA True False Don’t Know ______________________________________________________________________________ teachers are interviewed directly by the 73% 22% 5% person conducting the FBA

parents are interviewed directly by the person conducting the FBA

other school staff are interviewed directly by the person conducting the FBA

the student (subject of the FBA) is interviewed directly by the person conducting the FBA

a survey is given to teachers to fill out on their own

a survey is given to parents to fill out on their own

a survey is given to other school staff to fill out on their own 53%

58%

57%

79%

63%

51% 21%

23%

19%

12%

17%

25% 26%

19%

24%

9%

20%

24%

121

a survey is given to the student to fill out 17% 47% 36% on their own ______________________________________________________________________________

Participants were also asked about time spent conducting a direct observation (ABC) assessment. The idea behind this question was to discover how the ABC method was approached in terms of how much time was spent observing behavior. This question was especially important because in Texas the direct ABC method is recommended as part of the Texas Behavior Support Initiative (2019). As represented in Table 3, thirty one percent of the respondents indicated that two observation sessions were the norm with 26% indicating that four or more were typical. For those who commented on this question the basic consensus was that the number of observations depended on the student’s behavior. Although one respondent said that 10 consecutive days of data were required for their FBAs.

Table 3 Time spent on direct observation (ABC) assessment (N=124) ______________________________________________________________________________ When direct observation Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence (ABC) assessment is implemented as part of the FBA (choose one) ______________________________________________________________________________ 23% It is completed after one observation session

It is completed after two observation sessions 31%

It is completed after three observation sessions 19%

It is completed after four or more observation sessions 26%

the direct observation ABC assessment is not completed as part of the FBA 1% ______________________________________________________________________________

Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)

The respondents were asked about who was writing the plan and if the plans were based on the result of the FBA. The majority of the respondents (95%) indicated that BIPs are based on the results of the FBA and 86% indicated that those writing the plan also conducted the FBA. The majority of the respondents indicated the behavior plan includes a functionally equivalent replacement behavior for the target behavior as well as a means to address antecedents and consequences of target behaviors. Seventy six percent indicated that there is collaboration with teachers and staff who will run the plans. Approximately 70% of the respondents indicated those responsible for implementing the plan were trained to implement or collect data for the behavior plan. Only 50% indicated that the data were monitored by those who wrote the plan, however nearly eighty percent indicated that plan was modified when necessary based on the data from the plan. See Table 4.

Table 4

122

Development and Implementation of the Behavior Intervention Plan (N=146) _____________________________________________________________________________ A behavior intervention plan True False Don’t Know _____________________________________________________________________________

is written by the person or persons who conducted the FBA

is written based on the results of the FBA

is written in collaboration with teachers and staff who will implement the plan

includes a plan for a functionally equivalent replacement behavior for the target behavior

includes a plan to change the consequences for the target behavior so it is no longer reinforced 86%

95%

76%

92%

82% 11%

2%

19%

5%

6% 3%

3%

5%

3%

12%

includes a plan to alter antecedent stimuli to reduce target behavior and support replacement behavior 83% 6% 11%

is implemented by teachers and staff who have received training on how to implement the plan 68% 19% 13%

is implemented by teachers and staff who have received training on how to collect data for the plan 61% 26% 13%

data are monitored by the person or persons who wrote the plan 50% 36% 14%

is modified when necessary based on data collected on the 79% 10% 11% plan

____________________________________________________________________________

Training for special education teachers

Finally, the respondents were asked about the type of training special education teachers received since they are integral to the FBA process and the implementation of behavior plans. Over 50% indicated special education teachers were not adequately trained on conducting FBAs and writing intervention plans. However, over 50% indicated that special education teachers received training regarding data collection. See Table 5. Table 5

Special Education Teacher Training (N=145) ______________________________________________________________________________ Special Education teachers in your district True False Don’t Know 123

receive training on conducting functional behavior assessments.

receive training on writing behavior intervention plans.

receive training on collecting behavioral data. 23%

28%

59% 56%

55%

28% 21%

17%

13%

Discussion

The results of the study represent some promising practices. The majority of the respondents indicated that all three methods of FBA (Indirect, Direct ABC and Functional Analysis) were completed or a combination of the indirect and ABC method was completed. Fewer than 20% indicated that only one method was used to conduct an FBA with the majority of those indicating the direct ABC assessment was used alone. The research literature regarding the validity and reliability of various FBA procedures conducted in applied settings such as indirect assessment, direct systematic (ABC) observations and functional analysis has resulted in a mix of outcomes. Results of indirect assessment alone, may not be consistent with results found when direct observation and functional analysis are completed. The use of a combination of FBA procedures is recommended to enhance confidence in assessment (Gable et al 2014). The survey responses indicate that there are efforts to include a variety of procedures in the functional behavior assessment and not rely on just one method. The combination of FBA assessments used may be attributed to the personnel who are conducting FBAs. Since the majority of the FBAs are conducted by LSSPs followed by behavior specialists and board certified behavior analysts most of which have formal training in behavior assessment, it is not surprising that a combination of methods are used in keeping with professional practice and empirical research in applied behavior analysis.

At the surface, the FBA processes appear to be quite exhaustive given the respondents’ indication that three forms of FBA are used. However, looking deeper at the responses regarding the number of observations for the direct ABC method, it seems that method may not typically be very thorough. The majority of the respondents indicated the direct observation ABC method was completed after two observation sessions. With a little less than half indicating the observations were complete after three or more observation sessions. In order to get a clear idea of patterns of behavior it is recommended that multiple observations are conducted over time and across contexts. For an initial FBA O’Neill, Albin, Storey, Horner & Sprague (2015) recommend observing 15-20 occurrences over two to five days. Of course, this may vary depending on the nature of the behavior. The finding in this study may be the result of LSSPs and behavior specialists with enormous caseloads having difficulty finding the time to do multiple ABC direct observations on one student.

124

According to over half the respondents, special education teachers were not adequately trained to conduct FBAs or write behavior intervention plans. However, when respondents were asked if teachers had training on running behavior intervention plans the majority indicated they did. These findings are of concern. Given the important role special education teachers play in the completion of an FBA and development and implementation of the behavior intervention plan, the training they receive should be extensive. Even if teachers do not conduct an FBA or write a BIP themselves they should be knowledgeable about the processes so they can effectively contribute to them. Teachers are the professionals that have the most contact with the students and the most knowledge about the behavior in the schools. Teachers who understand functions of behavior and how an FBA is conducted can better participate in the FBA whether they are responding to an interview or gathering information for a direct ABC functional assessment. Additionally, teachers should be consulted when BIPs are developed so the BIP can be written so it will integrate within the context of the teachers’ classroom routine (Young and Martinez, 2016). Furthermore, the social validity of the FBAs and the behavior plans must be considered from the perspective of the teachers. In this case, social validity refers to the teachers’ perception of the acceptability and effectiveness of the FBA and BIP procedures (Cooper, Heron & Heward, 2007). Social validity can be enhanced when the teachers are knowledgeable about the concepts associated with FBA and BIP; have a voice in how and when to conduct an FBA; and they are invited to participate in the development of the BIP. When teachers are not part of the FBA process or the development of the BIP they may not find these procedures acceptable and may resist implementing them.

Regarding the behavior intervention plan, the majority indicated that the BIP is based on the functional behavior assessment and the function of the target behavior is addressed in the form of a replacement behavior. Additionally, antecedents and consequences were also modified. These results are in keeping with professional practice related to writing behavior intervention plans based on functional behavior assessment results (Umbreit et al, 2007). One area of concern was that only half of the respondents indicated that the data from the BIP was monitored by the person who wrote the BIP, however nearly 80% indicated that the plan was modified based on the data in the plan. These results beg the question of who is modifying the plans, if not those who wrote the plans. Typically, in professional practice, a behavior analyst will be responsible for conducting the FBA and developing and monitoring the plan. All changes are made based on data and they are made by the individual responsible for the plan, namely the one who developed the plan. When plans are written by one person and then monitored and amended by others the plan can potentially lose focus and consistency across its various iterations. As a result, the plan may not be as effective and confounding factors may be introduced as others modify the plan.

Conclusions

The results from this study illustrate that given the lack of specific direction in IDEA regarding how to conduct FBA and develop behavior plans, and given the lack of information about the level of training required, these practices will vary from school to school and they may potentially vary within a school. As discussed in the introduction IDEA encourages the use of PBIS when behavior interferes with learning, but applying techniques based on PBIS does not guarantee an FBA will be completed or behavior intervention will be based on an FBA. Nor does it guarantee those processes will be thorough and conducted by well trained personnel. The 125

results of this study suggest that there may be a need for more specific language in IDEA regarding the FBA and BIP processes; or at the very least, state education agencies could provide more guidance regarding a standard of practice and minimal competency when school personnel conduct an FBA and write and implement behavior intervention plans. Having consistency in practice and implementation is not only important for when the FBA and BIP are required by law, but it is also important when educators are utilizing FBA to create behavior intervention for students whose behavior interferes with learning. If schools do not have standards of practice that are consistent with professional research in the field, they may potentially conduct substandard FBAs and create less than effective behavior intervention plans, thus potentially denying students their right to a free and appropriate public education.

Limitations and Future Research

The sample is small and may not be representative of the various rural and urban areas in the state. A larger sample representing more schools and areas around Texas would provide a deeper look at what is happening in the schools. Additionally, a question regarding when an FBA is conducted was not included in the survey. This information is important to determine if there is a difference in how FBAs are conducted when the FBA is required by law or if they are conducted as a result of challenging behavior that interferes with student learning. Some comments to this survey indicated an FBA is more thorough when it is part of an initial evaluation or a manifestation determination. Future research will include questions to determine the FBA process when the FBA is legally required by IDEA and when the FBA is completed because behavior is interfering with learning.

References

Blood, E. & Neel, R.S. (2007). From FBA to implementation: A look at what is actually being delivered. Education and Treatment of Children, 30(4), 67-80. Carr, E.G. (1994). Emerging themes in the functional analysis of problem behavior, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 393-399. Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R.H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A., Sailor, W., et al. (2002). Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science, Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4(1), 4-16. Collins, L.W. & Zirkel, P.A. (2017). Functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans: Legal requirements and professional recommendations, Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(3), 180-190. Cooper, J.C., Heron, T. E. & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis. (2nd edition). New Jersey: Pearson. Gable, R. A., Park, K. L., & Scott, T. M. (2014). Functional behavior assessment and students at risk for or with emotional disabilities: Current issues and considerations. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(1), 111-135. O’Neill, R. E., Bundock, K., Kladis, K., & Hawken, L.S. (2015). Acceptability of functional behavior assessment procedures to special educators and school psychologists. Behavioral Disorders, 41(1), 51-66. O’Neill, R.E., Horner, R. H., Albin, R.W., Sprague, J. R., Storey, K., & Newton, J.S. (2015). Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior (3rd Edition). California: Brooks/Cole.

126

Positive Behavior Interventions & Support (2019). PBIS and the law, Retrieved March 11, 2019, from https://www.pbis.org/school/pbis-and-the-law Texas Behavior Support (2019). PBIS, Retrieved March 13, 2019, from https://www.txbehaviorsupport.org/pbis Texas Behavior Support Initiative (2019), Retrieved March 13, 2019, from https://www.txbehaviorsupport.org/tbsi Umbreit, J., Ferro, J., Liaupsin, C. J., & Lane, K. L. (2007). Functional behavior assessment and function-based intervention. New Jersey: Pearson. Von Ravensberg, H., & Blakely, A. (2015). When to use functional behavioral assessment? A state-by-state analysis of the law. OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. www.pbis.org. Weber, K.P., Killu, K. Derby, K.M. & Barretto, A. (2005). The status of functional behavior assessment (FBA): Adherence to standard practice in FBA methodology. Psychology in the Schools, 42(7), 737-744. Yell, M.L. (2016). The law and special education (4th edition). Pearson Young, A. & Martinez, R. (2016). Teachers’ explanations for challenging behavior in the classroom: What do teachers know about functional behavior assessment? National Teacher Education Journal, 9(1), 39-46. Zirkel, P.A. (2011). State special education laws for functional behavioral assessment and behavior intervention plans. Behavioral Disorders, 36(4), 262-278.

About the Authors

Andria Young is a professor of Special Education at the University of Houston – Victoria and a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). Dr. Young’s research focus is on teacher training regarding functional behavior assessment (FBA) and implementation of FBA in the schools.

Terrisa Cortines has a Master’s of Education in Special Education. She is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Houston Victoria and a Registered Professional Educational Diagnostician. For the past 22 years, Mrs. Cortines has worked in the public school setting; four years as a paraprofessional, three years as a special education teacher, and fifteen years as an educational diagnostician.

127