26 minute read

Evaluation and Practices of Mobile Applications as an Assistive Technology for Students with Dyslexia: A Systematic Review Nicole Bell and Julia VanderMolen

Evaluation and Practices of Mobile Applications as an Assistive Technology for Students with Dyslexia: A Systematic Review

Nicole Bell, BS, OTS Julia VanderMolen, Ph.D, CHES

Advertisement

Grand Valley State University

Abstract

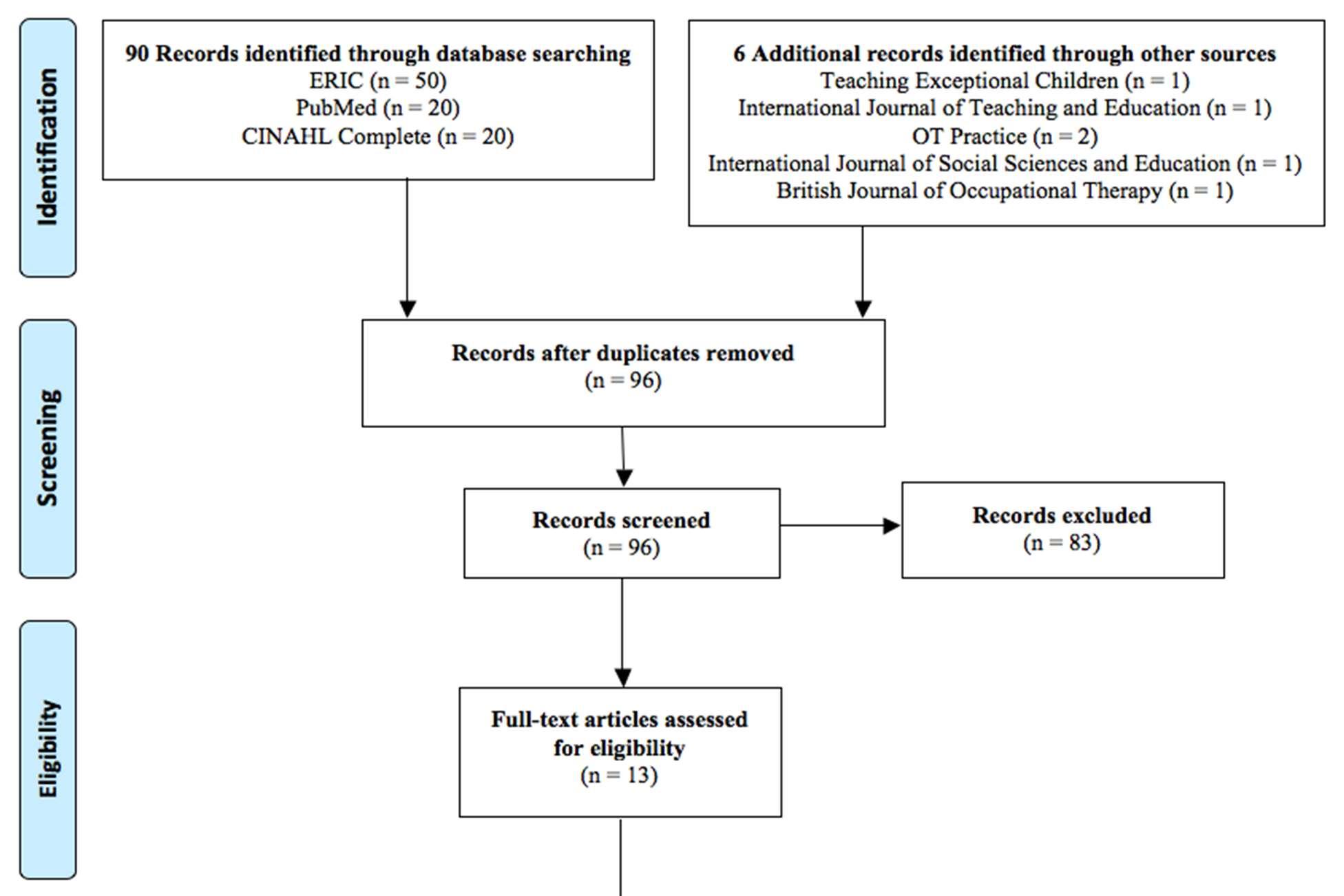

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the benefits of mobile applications as an assistive technology (AT) for individuals with dyslexia. The researchers in the present review aimed to identify specific practices that have been shown to improve the reading engagement and comprehension of individuals with dyslexia. To develop an understanding of the existing literature pertaining to the benefits of mobile applications as an AT for students with dyslexia, a systematic review was conducted. The following databases were searched for the review (a) ERIC, (b) PubMed, (c) CINAHL Complete, and (d) Web of Science. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and removing duplicates, 83 articles were excluded on the basis that they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies were deemed relevant to the topic based on the titles and abstracts. More research is needed for mobile applications as an AT and its implications in education.

Keywords: dyslexia, assistive technology, mobile applications, occupational therapy

Evaluation and Practices of Mobile Applications as an Assistive Technology for Students with Dyslexia: A Systematic Review

In the United States’, the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) (2004), Assistive Technologies (ATs) are broadly defined as “any technology, which enhances the performance of individuals with disabilities” (Haq & Elwaris, 2013, p. 880). ATs can be devices, items, equipment, or product systems that increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of students with disabilities (IDEA, 2004; Goodrich & Garza, 2015; Parette, Crowley, and Wojcik, 2007). AT can reduce the effects of specific disabilities and allow students to focus their ability on the particular demands of academic tasks of importance, such as reading and literacy. Reading is not merely an activity for gaining knowledge. It is a transactional activity in which people engage, in the role of either student, employee, or employer, and as a leisure participant (Rosenblatt, 2013). The reader engages with a task object, the reading medium—for example, a book, iPad, or food nutrition label.

The use of mobile technology has become increasingly popular for reading activities in the past decade, resulting in a higher potential and demand for the implementation of mobile applications. Mobile applications allow for convenient transportation and access to activities in daily life at school, home, and in the community (Reid, 2013). Applications can be personalized to account for an individual’s needs (Dawson, 2018). Additionally, mobile apps as AT can provide children with dyslexia with assistance in reading literacy and comprehension (Reid, 128

2013). According to Grajo & Candler (2014), a reading specialist, a classroom teacher, and a speech and language pathologist is trained in addressing the skill of reading. However, occupational therapy (OT) as it applies to reading intervention goes beyond developing reading skills. An OT's approach places a focus on increasing engagement in reading as an occupation.

OT practitioners and special education teachers have the potential to enhance reading skills and comprehension skills of children through the use of AT. Furthermore, Vernock, McCormack, and Chard (2011) explored the Irish OT's view on the benefits of electronic assistive technology (EAT). While the need for further AT training includes computer applications, little research has been undertaken in the area of knowledge in the use of EAT by OTs. If an OT is to deliver occupation-focus and person-centered services, they will, at the very least, need to know what is available, how to access and use EAT with a client (Vernock, McCormack, & Chard, 2011; Orton, 2008). Additionally, training of OTs regarding the implementation of AT is necessary and can be a direct benefit for children with dyslexia.

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the practices of mobile applications as an assistive technology for individuals with dyslexia. Based on knowledge from previous studies, the researchers in the present review aimed to identify specific practices shown to improve the reading engagement and comprehension of individuals with dyslexia using AT.

Methods

To develop an understanding of the existing literature pertaining to the benefits of mobile applications as an assistive technology for students with dyslexia, a systematic review was conducted by two researchers. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses (PRISMA) Group provides crucial guidelines for the development, reporting, and replicability of systematic review methodology. The authors followed the guidelines established in the PRISMA statement, including adherence to the 27-item checklist and recommendations for transparent reporting (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & the PRISMA Group, 2009). A total of 13 articles were identified as relevant to the topic.

Criteria for Considering Studies

To be included in this search, the studies had to meet three criteria to be included in the review: (a) studies published between 2011 and 2018, (b) studies used mobile applications and assistive technology, and (c) studies utilizing assistive technology to help individuals with dyslexia. The authors restricted the review to studies conducted from 2011 to avoid redundancy. The following databases and sites were searched for this review (a) ERIC, (b) PubMed, and (c) CINAHL Complete. A summary of the article exclusions with reasoning is presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) in Figure 1.

129

Figure 1. Study flow diagram for review of studies pertaining to assistive technology and dyslexia. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Search Strategy

A three-step search strategy was used. First, an initial search of two databases was completed to identify keywords, such as assistive technology and dyslexia. Second, four health and educationrelated databases were systematically searched using the keywords. These were (a) ERIC, (b) PubMed, and (c) CINAHL Complete. Last, the reference lists of all identified reports and articles were hand-searched for additional studies. Figure 2 provides an example search strategy detail from PubMed.

130

("dyslexia"[MeSH Terms] OR "dyslexia"[All Fields]) AND ("self-help devices"[MeSH Terms] OR ("self-help"[All Fields] AND "devices"[All Fields]) OR "self-help devices"[All Fields] OR ("assistive"[All Fields] AND "technology"[All Fields]) OR "assistive technology"[All Fields]) AND ("loattrfull text"[sb] AND ("2011/01/01"[PDAT] : "2018/12/31"[PDAT])) Figure 2. Search Detail from PubMed

Data Collection

Data were extracted from the papers in the review using the standardized data extraction tool from the PRISMA. The extracted data included specific details about the participants’ demographics and the sample size, study methods, interventions, number and reasons for withdrawals and dropouts, and any outcomes of significance with regard to the aim of the review.

Results

The search identified 96 potentially relevant articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and removing duplicates, 83 were excluded on the basis that they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 13 studies were deemed relevant to the topic based on the titles and abstracts. The full-text of each peer-reviewed article was then checked, and a decision was made to include the articles for data analysis or exclude the articles from the next stage of assessment.

General Assistive Technology and Dyslexia

Research has revealed that “AT may mediate reading challenges by providing options for accessing information and customizing the display of information” (Dawson, Antonenko, & Lane, 2018, p. 3). Authors Dawson, Antonenko, and Lane (2018) addressed assistive technologies used to aid students with dyslexia. Assistive technology for students with dyslexia mediates the challenges these individuals encounter, such as reading, writing, and spelling. Furthermore, students with skill deficiencies in reading can benefit from AT such as text-tospeech software and e-readers. Text-to-speech software is useful for students with weak decoding skills, low levels of fluency, and active listening comprehension skills. Whereas, ereaders allow for customization and interaction of information in a personalized setting. Thus, allowing for customization of features such as fonts, font size, highlighting, spacing, listening speeds, and page displays have proven to influence positively and enhance a student’s reading comprehension skills. Additionally, Dawson, Antonenko, and Lane (2018) go on to mention three specific applications to assist students with dyslexia, DyslexiaHelp, SpedApps, and Tech Finder. DyslexiaHelp provides an extensive list of applications for students, parents, and teachers. SpedApps is a website with a focus on special education and Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) education. Finally, Tech Finder, a search tool for technology apps for learning disabilities and issues, allows searches for specific challenge areas such as reading, writing, organization, and grade level.

To further substantiate the research conducted by Dawson, Antonenko, and Lane (2018), authors Reid, Strnadová, and Cumming (2013) discuss the variety of needs met by mobile technology for students with dyslexia, including reading, writing, and studying skills. Material presented in a multisensory learning fashion is optimal for students with dyslexia. This allows each program the

131

potential to be personalized to meet the needs of each student and their preferred learning environment. Successful outcomes are most often impaired from the inability to take responsibility and implement assistive technology. It is essential for parents, teachers, and [other professionals involved] to be familiar with these resources to provide up-to-date tools to assist individuals with dyslexia.

Harper, Kurtzworth-Keen, and Marable (2017) assessed the impact of the LiveScribe Pen (LSP) regarding curriculum accessibility, increasing academic independence, and promoting academic study skills. The LSP features include a microphone to enhance the audio recording, playback speaker, camera, and internal memory that stores handwritten notes, audio, and images. The words can sync to iOS and Android devices, providing convenient access to material in any environment. Interviews reveal that the LSP provided increased access to curriculum material, such as a text-to-speech feature for assigned readings. With access to more resources via LSP [wording] the student showed increased independence completing homework and expanded academic study skills including “better time management, enhanced audio skills, and deepened the connection between reading and writing” (p. 2479). AT also provides non-academic gains such as ownership of learning, increased happiness, and elevated aspirations, all of which contribute to learning. Table 1 summarizes the main findings.

Table 1 Summary of articles addressing general assistive technology and dyslexia.

Level of Evidence/ Study Design/ Participants/ Intervention Inclusion and Control Outcome Author/Year Criteria Groups Measures

Dawson, K., Antonenko, Level V N/A N/A P., Lane, H., & Zhu, J. N=N/A (2018) doi: 10.1177/00400599187940 27

Results

N/A

Reid, G., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. (2013) doi: 10.1111/14713802.12013 Level V N=N/A N/A N/A N/A

Harper. K. A., Kurtzworth-Keen, K., & Marable, M. A. (2017) doi: 10.1007/s10639-0169555-0

Level IV N=1 (4th grade student in NY with dyslexia) A 4th grade Document the student with impact of the dyslexia used LSP regarding the LiveScribe (a) curriculum Pen for one year. accessibility, (b) how it can be The LSP increased curriculum accessibility for the student, independence

132

implemented as an audio tool to increase academic success and independence, (c) how it could be used as a tool for promoting study skills while studying as well as academic study skills. Additionally, time management, auditory skills, and a better understanding of reading and writing were gained by the student.

Mobile Applications as Assistive Technology

Skiada, Soroniata, Gardeli, and Zissis (2014) developed and analyzed the effectiveness of a mobile application, EasyLexia, for students with learning difficulties. The authors stated that mlearning application for mobile devices have the ability to “motivate the children and engage their attention while focusing on solving problems, improving their memory, their reading, and writing skills” (p. 228). Children were able to become familiarized with the layout of the app and utilize its features independently. This leads to an overall increase in performance over a short time. Additionally, efficiency allowed children to learn the functionality and use it independently, decreasing the need for assistance.

Another study pertaining to the use of mobile applications as assistive technology by Fälth and Svensson (2015) studied whether Prizmo, a mobile application, for the iPhone/iPad app could assist students with dyslexia. Prizmo is a multifunctional program and has several primary functions, including scanning text and synthesizing speech. Additional features allow students to adjust the reading speed, listen to, and save scanned text and highlight words. Fälth and Svensson (2015) found that the ease of accessibility and use show a positive effect on students with learning disabilities (LD). AT tools, such as Prizmo, can be implemented in a child's environment to improve reading and writing skills for those with LD.

Lindeblad, Nilsson, Gustafson, and Svensson, also (2016) investigated whether AT on smartphones and tablets have a transfer effect on students with reading difficulties after one year of intervention. AT provided students with a platform to level the playing field compared to students without LD. Reading development was significantly improved in children with impaired reading abilities. Through the use of various mobile applications such as Prizmo, Easy Writer, SayHi, iTranslate, Dragon Search, and Voice Reader Web, showed an overall increase in motivation and independent learning as a result. The study concluded that the aspects of a reading-impaired person’s forthcoming development, such as self-confidence, motivation to learn, relief of feelings of stigmatization and family relations, can be affected by using AT” (p. 9).

133

Alghabban, Salama, and Altalhi (2017) conducted a study in which measured the effectiveness of a multimodal m-learning application for students with dyslexia. Through the use of multimodal interfaces, users access information through a variety of interaction styles, including visual and auditory features such as graphics and text. It was concluded that, “it is important to adopt multimodality functions (combined with m-learning, cloud-based technology) that examine not only the needs of learners with dyslexia but also their preferred learning styles” (p. 161). Furthermore, the study revealed an increase of 30% increase in reading skills after using the multimodal tool for three months, in the third graders. Additionally, the app adapts content based on individual student profile and learning preference, leading to increased motivation and reading interest.

Tariq and Latif (2016) created an app for Android-powered devices that assist students with dyslexia. Evaluation of this app measured supportability, compatibility, learnability, efficiency, errors, and user satisfaction. These factors contribute to the learning environment and progress rates. The application revealed a high potential for a cost-effective, efficient assistant technology resource.

Haq and Elwaris (2013) discuss the importance of the implementation and application of AT in early education. Additionally, the authors provided guidelines for selecting the appropriate AT for each student with a learning disability (LD). Furthermore, Haq and Elwaris (2013) discussed the importance of reading, as it is an essential component of social survival by serving as a gateway to success in both academics and life. Reading literacy and comprehension skills contribute to increased independence in academics, as well as the quality of life. Therefore, selection of AT should be based on the needs, environment, task, and tools, specific to the student such as the Students, Environments, Tasks, and Tools ( SETT framework)–Additionally, selection of AT should be a collaborative effort of parents, teachers, rehabilitation specialists such as an OT, in order to enhance academic achievement. AT creates an increase in accessibility to learning, as well as increased motivation and productivity. Likewise, it empowers students to learn independently and successfully.

Madeira, Silva, Marcelino, and Ferreira (2015) aimed to create an application for Android and combine it with learning to help Portuguese students with challenges associated with dyslexia. The International Dyslexia Association states that, “overcoming dyslexia, and other learning difficulties, can be achieved through multisensory re-education, which involves the use of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile pathways simultaneously to enhance memory and written language learning” (p. 419). Specific features, which can be modified to help dyslexic students, include font style, formatting, writing style, and layout. The app used in this study, Dyseggxia, is a mobile game aimed at enhancing spelling skills. This app, as well as early intervention, has been shown to alleviate/overcome reading difficulties. Results show that applications provide students with dyslexia the tool to perform at a similar rate to those of regular readers. Additionally, AT minimizes feelings of exclusion, rejection, harassment, abandonment, and failure. Table 2 provides a summary of the articles addressing mobile applications as assistive technology.

Table 2 Summary of articles addressing Mobile Applications as Assistive Technology

134

Author/Year

Skiada, R., Soroniati, E., Gardeli, A., & Zissis, D. (2014) doi:10.1016/j.pr ocs.2014.02.025 Fälth, L., & Svensson, I. (2015) doi: 10.20472/TE.20 15.3.1.001

Level of

Evidence/ Study Design/

Participants/

Inclusion

Criteria

Level II N=10 school age children Intervention group, n=5 Control group, Level II N=12 (7 fifth graders, 3 fifth grade teachers, 2 ninth n=5

Intervention and Control

Groups

Students were given a mobile phone and encouraged to use the application, EasyLexia, during class. Over a 5-6 week used Prizmo in class for 30-40 minutes, 4-6 the following photograph the text, prune the text, adjust the and listen to and 135

Outcome

Measures Results

Evaluate the Identified usability of the increase in application as performance well as the over a short strengths and period of using weaknesses it application. contributes to Students showed each users preference in learning using a mobile experience in the application classroom. during class tasks and tests. Mobile application promoted concentration and focus on the task. "Preliminary results show the promising prospects mobile learning holds in

5 ninth graders; grade teachers) period, students times a week. Students used features: reading speed, such contexts." Investigate if Results show Prizmo's improved word accessibility decoding for allows students with a smartphones and dyslexic profile, tablets the contributing to potential to serve keeping up with as AT for language skills students with a to enhance dyslexic profile. students' reading skills. Prizmo increased access to text, focus on

content,

Lindeblad, E., Nilsson, S., Gustafson, S., & Svensson, I. (2016) http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/174831 07.2016.125311 6 Alghabban, W. G., Salama, R. M., & Altalhi, A. H. (2017) https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.chb.201 7.05.014 Level III N=35 (n=23 boys, n= girls; between 10 and 12 years old;

4th-6th grade) Level V

Students with dyslexia in elementary schools, parents and teachers 136 save the scanned usability, and text. accessibility. Students used To investigate The reading the apps, the effects of impaired group Prizmo, East these showed transfer Writer, SayHi, applications as effects on iTranslate, AT on reading reading ability. Dragon Search, development in "The children and Voice children with with reading Reader Web to reading difficulties train and difficulties after showed a similar compensate for one year of reading reading intervention. progression rate deficiencies for as the norm 5 weeks. These group" (p. 8). applications "The smartphone were used 4 and tablet times a week for applications 40-60 minutes showed each time. An "accessible average number qualities and of sessions was easy features," 33. as well as increasing motivation and independence (p. 9) Interviewed and To determine the gave a survey to gaps remaining The proposed students, parents in the learning multimodal and teachers. field of dyslexia interface Students used specify the needs improves learning tool that of the user and reading skills helps with to identify (before reading skills. reading skills mean=57.57; students with after dyslexia find mean=82.86). most difficult. The app allows a student to modify features to their specific learning preferences, contributing to

increased scores.

Tariq, R., & Latif, S. (2016)

https://www.jsto r.org/stable/jedu ctechsoci.19.4.1 51

Madeira, J., Silva, C., Marcelino, L., & Ferreira, P. (2015)

https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.procs.2 015.08.535 Level III N=20 dyslexic children 5 years old and under Level II Control Group, Children used an application on the Galaxy SIII weeks.

N=8 students Students tested ages 10-12 in application for 1 fifth grade week, on Intervention separate days, Group, n=4 with four 15dyslexic students minute rounds. tablet for two 137 n=4 nondyslexic students Explored whether the app could foster learning and improve handwriting in children with dyslexia and "to better understand strengths/weakn esses of performance during learning process while acknowledging learning efforts to improve incorrect answers selected by the player, total time spent with that question, average time spent between score. learning" 89% showed improvements in score and achieved learning objectives after five lessons. The app proved to show usability, accessibility, and presentation of learning content. "Preliminary results showed promising effectiveness for advancing handwriting

- usability, The use of AT functionality and showed the relevance of students with application dyslexia were - performance of able to achieve each group results similar to (gathered - readers without device id, date, reading time, question, difficulty in 5th correct answers grade. randomized, randomized, words (answers) each tap, time for each tap and

skills."

Mobile Application as AT in OT Practice

Roll, Lavey, Nye, and Johnson (2018) reviewed two case studies to highlight the need for the integration of assistive technology intervention in OT curriculum. The Assistive Technology Resources Center (ATCR) at Colorado State University (CSU) implemented the Human Activity Assistive Technology (HAAT) model into the OT curriculum to enhance student awareness of AT. The HAAT model is a holistic approach, taking into account numerous components of a student’s case. A student's case includes personal factors, meaningful occupations, and the environment in which the individual participates in the occupation. This holistic perspective allows students to “identify appropriate AT that can optimize student performance and participation in higher education” (p. 28). Through the use of the HAAT model at the ATRC, OT’s can provide education, research, and services for implementing AT. As the number of students with disabilities continues to rise, the demand for AT does as well.

Verdonck, McCormack, and Chard (2011) analyzed/surveyed Irish occupational therapists’ knowledge and use of Electronic Assistive Technology (EAT). Results showed a significant deficiency in the understanding of benefits, competence, and roles AT plays in OT practice. When asked if OTs should be able to assess and prescribe for EAT, 84% responded with yes. However, only 34% of participants signified that they were able to evaluate for EAT. Training OTs in up-to-date knowledge of assistive technology will contribute to the OT's ability to meet the occupational needs of each client. Implementation of AT can have a significant effect on the quality of life, self-esteem, leisure, careers, and relationships. Results from this study support the need for more general AT training for OTs to familiarize and keep up to date with technological advances. Table 3 provides a summary of the peer-reviewed articles addressing the mobile application as AT in OT practice.

Table 3 Summary of articles addressing Mobile Application as AT in OT Practice

Level of Evidence/ Study Design/ Participants/ Intervention Inclusion and Control Outcome Author/Year Criteria Groups Measures Results

Roll, M. C., Level IV Occupational Evaluated Both students Lavey, S., Nye, N= 2 adults therapy students performance on showed positive E., & Johnson, gave two mCOPM and outcomes and W. (2018) students with satisfaction with were successful disabilities AT. in their assistive education. technology to Occupational help with their therapy education. These practitioners tools assisted have the with reading, potential to writing, and note contribute to taking. disability 138

Verdonck, M., McCormack, C., & Chard, G. (2011) doi: 10.4276/030802 211X130210487 23291 Level V N= 56 Irish Community Occupational Therapists services on campus.

Irish Community Survey questions 98% of Occupational were asked to respondents Therapists indicate Irish agreed EAT attended a OT's knowledge improved conference titled on the benefits independence 'Electronic of EAT, their and 89% agreed assistive competence/kno it enhances selftechnology for wledge of EAT, esteem. 84% persons with and their role in believe OTs physical and prescribing should be able to sensory EAT. assess for EAT, disabilities in while only 34% their home.' reported being Attendees were able to do so. asked to Lastly, 70% of complete an OT attendees EAT (Electronic indicated that Assistive they thought it Technology) was a role of survey after the specialized OT seminar and 63% agreed it was a role of community OTs.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate and summarize peer-reviewed literature about the benefits of mobile applications as an assistive technology for individuals with dyslexia and to address the need for training of OTs in this area. A priority goal was to examine the advantages of implementing mobile applications as a modality for helping an individual with dyslexia to better understand health information and to increase health literacy. Researchers in the present review concluded that the utilization of mobile applications prove to be beneficial to an individual and helps to alleviate challenges associated with dyslexia.

Though the study sought to adhere to the recommendation of the PRISMA guidelines, the study is not without limitations. While a variety of studies were reviewed, each came with limitations to consider. A majority of studies were conducted in countries outside the United States and not written in English; therefore, they are exempt from this review. It is recommended that the review is updated to reflect the most current advances in the use of mobile applications as a modality to help mediate difficulties accompanied by dyslexia. Moreover, the literature search process also revealed that far more work on the subject is needed. Particularly concerning the rich knowledge and experiences with the use of mobile applications to assist individuals with dyslexia. 139

The promising outcomes of this systematic review revealed that the use of mobile applications as an AT tool for students with dyslexia is warranted. Likewise, the evidence suggests benefits in reading literacy and comprehension through the use of these applications. The recent growth in mobile technologies has introduced a variety of new learning interventions and have shown promising outcomes for the learning needs by accommodating the individual needs of students with dyslexia. Although proven beneficial, research and production of applications are needed to expand on available resources. Tariq and Latif (2016) recommend there should be a focus on developing resources to a broader audience, as well as on a variety of compatible mobile devices. Creating applications compatible on both phones and tablets, as well as for both Android and iOS users, will allow increased access to the necessary tools to address the challenges associated with dyslexia. Additionally, Madeira et al., (2015) suggest continuing to develop mobile applications that implement multisensory features to accommodate individual needs. Including multisensory interventions will enhance the usability of the app and increase the number of learning methods available. Furthermore, Reid et al., (2013) address the importance of professional development regarding mobile applications as assistive technology. Increasing health professionals’ training on the latest assistive technology will help the best needs of their clients.

Findings from the reviewed articles provide evidence about the benefits of mobile applications as an assistive technology tool to improve overall reading performance in individuals with dyslexia. While further research is needed, the articles used in this review laid a foundation for the beneficial outcomes mobile applications can provide pertaining to improved reading engagement and comprehension. Additionally, the need for training of health care providers in the most recent assistive technology is crucial to providing individuals with the most optimal care. Lastly, more research is needed regarding mobile applications as AT and their implications in occupational therapy.

Implications for Practice

In order to understand the implications of mobile applications and occupational therapy intervention, more research is needed. Additional randomized control clinical trials and observational studies of high quality are also needed. Longitudinal studies must be conducted to understand the long-term effects of such tools on reading literacy and comprehension from a holistic approach. Furthermore, more research should build on existing explorations of integrating universal design and universal design for learning. Larger sample sizes should be explored as well. The assessment and evaluation of specific training of AT for OTs have the potential to approach reading as an occupation in order to enhance both performance and participation for individuals with dyslexia.

References

AbleData. (2015). AT for students with learning disabilities in elementary schools. AbleData Tools and Technologies to Enhance Life. Retrieved from https://abledata.acl.gov/sites/default/files/AT%20For%20Students%20with%20Learning %20Disabilities%20in%20Elementary%20School_PDF.pdf

140

Alghabban, W. G., Salama, R. M., & Altalhi, A. H. (2017). Mobile cloud computing: An effective multimodal interface tool for students with dyslexia. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 160-166. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.014 Dawson, K., Antonenko, P., Lane, H., & Zhu, J. (2019). Assistive technologies to support students with dyslexia. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 51(3), 226-239. doi:10.1177/0040059918794027 Fälth, L., & Svensson, I. (2015). An app as ‘reading glasses’ – A study of the interaction between individual and assistive technology for students with a dyslexic profile. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(1), 1-12. doi: 10.20472/TE.2015.3.1.001 Grajo, L., & Candler, C. (2014). Children with reading difficulties: How occupational therapy can help. OT Practice, 19(13), 16. Gitlow, L., & Kinney, A. (2014). Project Lenny: Service learning to expand assistive technology training. OT Practice, 19(1), 9-13. doi: 10.7138/otp.2014.1901f1 Goodrich, B., & Garza, E. (2015). The role of occupational therapy in providing assistive technology devices and services: Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/AboutOT/Professionals/WhatIsOT/RDP/F acts/AT-fact-sheet.pdf Harper, K. A., Kurtzworth-Keen, K., & Marable, M. A. (2017). Assistive technology for students with learning disabilities: A glimpse of the livescribe pen and its impact on homework completion. Education and Information Technologies, 22(5), 2471-2483. doi:10.1007/s10639-016-9555-0 Haq, F., & Elwaris, H. (2013). Using assistive technology to enhance the learning of basic literacy skills for students with learning disabilities. International Journal of Social Sciences & Education, 3(4), 880-885. Lindeblad, E., Nilsson, S., Gustafson, S., Svensson, I., Linnéuniversitetet, Institutionen för psykologi (PSY), & Fakulteten för Hälso-och livsvetenskap (FHL). (2017). Assistive technology as reading interventions for children with reading impairments with a oneyear follow-up. Disability and Rehabilitation, 12(7), 713. Madeira, J., Silva, C., Marcelino, L., & Ferreira, P. (2015). Assistive mobile applications for dyslexia. Procedia Computer Science, 64, 417-424. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.08.535 Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D., PRISMA Grp, & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-W64. Parette, H. P., Crowley, E. P., & Wojcik, B. W. (2007). Reducing overload in students with learning and behavioral disorders: The role of assistive technology. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 4(1), 1-12. Retrieved January 31, 2019 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/55642/. Reid, G., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. (2013). Expanding horizons for students with dyslexia in the 21st century: Universal design and mobile technology. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13(3), 175-181. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12013 Roll, M. C., Lavey, S., Nye, E., & Johnson, W. (2018). Occupational therapy and assistive technology: Unique contributions to accessibility in higher education. OT Practice Magazine. 26-28

141

Skiada, R., Soroniati, E., Gardeli, A., & Zissis, D. (2014). EasyLexia: A mobile application for children with learning difficulties. Procedia Computer Science, 27, 218-228. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2014.02.025 Tariq, R., & Latif, S. (2016). A mobile application to improve learning performance of dyslexic children with writing difficulties. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 19(4), 151-166. Veater, H. M., Plester, B., & Wood, C. (2011). Use of text message abbreviations and literacy skills in children with dyslexia. Dyslexia, 17(1), 65-71. doi:10.1002/dys.406 Verdonck, M., McCormack, C., & Chard, G. (2011). Irish occupational therapists’ views of electronic assistive technology. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(4), 185-190. DOI: 10.4276/030802211X13021048723291

About the Authors

Nicole Bell is a full-time graduate student in the Occupational Therapy and Science Program at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. Her research interests include assistive technology, dyslexia and sleep in older adults.

Dr. Julia VanderMolen is an Assistant Professor of Public Health with Grand Valley State University in Michigan. The contribution of her research is to examine the benefits of assistive technology, UD and UDL. Additionally, Dr. VanderMolen’s recent work has included the benefits of 3D printing for the visually impaired, the concept of universal design and learning and the use of mobile technology to assist individuals with disabilities.

142