51 minute read

Teachers as Behavior Professionals: Understanding the Experiences of Teachers as BCBAs Justin N. Coy and Jennifer L. Russell

Teachers as Behavior Professionals: Understanding the Experiences of Teachers as BCBAs

Justin N. Coy, M.Ed., BCBA Jennifer L. Russell, Ph.D.

Advertisement

University of Pittsburgh

Abstract

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is a well-defined field and discipline recognized by both scientific and professional organizations. Since the establishment of our professional discipline, ABA has seen immense growth in university training programs, empirical research, and certified practitioners. Despite knowing the basic demographic information about behavior analysts (including employment status, type and areas of work, etc.), little work has examined the actual experiences of dedicated behavior professionals. This article presents in-depth, systematic qualitative data on the experience of teachers who returned to school for their certification, including their introduction to the field, training program experiences, supervision experiences, and actualized professional gains as a result of obtaining their BCBA. This work reports the experiences of behavior analysts and provides an initial behavior professional experience model. The results of this exploratory study have implications for behavior professionals, the field as a whole, and programs responsible for training future behavior analysts.

Teachers as Behavior Professionals: Understanding the Experiences of Teachers as BCBAs

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is a field, discipline, and practice honed since its founding in the 1950s-60s (Morris, Altus, & Smith, 2013). ABA uses unique and well-developed research methods, principles, and procedures to improve socially significant behaviors in individuals (Carr & Nosik, 2017; Dixon, Vogel, & Tarbox, 2012; Jacobson & Holburn, 2004). Researchers and practitioners use natural reinforcers, individualized interventions, and systematic instruction to change behavior and build skills (Carr & Nosik, 2017). These techniques are most commonly employed in educational or private settings working with students or clients.

Consistent with the growth of any profession, the field has seen increases in university training programs, experimental and applied research studies, and certified practitioners (Carr & Nosik, 2017). The recent rapid growth of our professional discipline is empirically established (Burning Glass, 2015; Carr & Nosik, 2017; Deochand & Fuqua, 2016). Since establishing the Behavior Analysis Certification Board (BACB®) in 1998, membership in professional organizations, conference attendance, and credentialing continue to increase (Association of Professional Behavior Analysts [APBA], 2015; Carr & Nosik, 2017; Deochand & Fuqua, 2016), mirroring increasing demand for credentialed behavior analysts (BACB, 2018). Recent analyses of BACB certification trends found continual increased growth in certificants, with a noticeable rate increase since 2010 (APBA, 2015; Deochand & Fuqua, 2016). There are now over 30,000 ABA professionals worldwide (BACB, n.d.); modeling predicts that number may surpass 42,000 by 2020 (Deochand & Fuqua, 2016). Additionally, only 1.5% of certified behavior analysts fail to complete the required continuing education credits and let their professional certification lapse (Deochand & Fuqua, 2016). These data highlight: (a) the number of certificants is growing

significantly, and (b) once obtaining their certifications ABA professionals dedicate themselves to the field and rarely leave. These are positive signs; the applied work of this field must be implemented by trained and dedicated professionals.

While there is strong evidence that the ABA field is expanding, there has been little research aimed at understanding the professionals that comprise it. Our field depends on highly trained and specialized professionals who complete multiple Master’s level courses, fulfill up to 1,500 hours of supervised internship, and pass a 150-question exam (BACB, 2018). By doing so, these professionals become Board Certified Behavior Analysts (“BCBAs”). Given that these BCBAs are the primary representatives and practitioners that bring ABA into practice, it is critical for the field to understand the experiences of our committed professionals. There is a tradition of research in education investigating the experiences of teachers and other educational professionals. Direct interviews, secondary analyses, and literature reviews have focused on understanding the professional experiences of teachers resulting in important research findings regarding: (a) methods for recruiting highly-qualified teachers (e.g., Johnson, 2006); (b) the effect of teachers’ working conditions, including physical features, organizational structures, and cultural and political factors (e.g., Johnson, Kraft, & Papay, 2012); and (c) the need for induction and mentoring supports to keep skilled educators in the field (e.g., Johnson, Berg, & Donaldson, 2005). Yet this work typically focuses on general and special education classroom teachers; the experiences of other education professionals may vary dramatically. Researchers have investigated the experiences of various educational professionals, including speechlanguage pathologists (e.g., Morrison, Lincoln, & Reed, 2011), school psychologists (e.g., Proctor & Steadman, 2003), and occupational therapists (e.g., Bose & Hinojosa, 2008). However, to date limited work has investigated the experiences of behavior professionals (BCBAs).

The authors realize that a paper focused on professional experiences is unusual for the field. However, recent original articles, subsequent commentaries, and special issues have focused on important professional experiences (including training and supervision). Behavior Analysis in Practice (BAP) published a series of 15 articles (beginning with an original article by Dixon, Reed, Smith, Belisle, and Jackson, 2015) discussing quality assessment of ABA training programs. A recent special issue discussed aspects of professional supervision, including supervision ethics, structures/models, and conflict management (LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016). Original research (Becirevic, 2014) and a set of four commentaries addressed how behavior analysts should combat misconceptions and discuss behavior analysis with outsiders of the field (Becirevic, 2015).

Most of the articles discussed above present the opinion and voice of research faculty members or university professors. These experts provide important, knowledgeable perspectives and should not be underappreciated. However, it is worth noting that the collective voices of practicing professionals have not yet entered into these debates. Iwata (2015) recognizes the importance of practitioner voices to address aspects of our field, including program quality. Recent survey work has explored program information reported by approved training program directors (Blydenburg & Diller, 2016) and examined how program graduates should respond to misconceptions or misunderstandings about our field (Becirevic, 2014). This survey work provides an important starting point by gaining the general perspective of professionals in the

field. In-depth qualitative data collection and analysis can allow researchers to get a deeper understanding of behavior analysts’ experiences. This exploratory study focuses on the experience of behavior analysts who completed their training program requirements as full-time teachers – it is likely that these stakeholders offer substantial buy-in, and likely influence multiple groups including students, parents, paraprofessionals, and administrators, all of whom could end up researching or investing in ABA. The driving research questions included: (1) What brought these teachers to the field of ABA? (2) How would they describe their training program and supervision experiences? (3) What actualized gains resulted from their training? Answering these questions provides meaningful insight into the training experiences of our behavior professionals and can help support the growth and dissemination of behavior analysis.

Method

Recruitment

The BACB® Certificant Registry was used to recruit participants. Email invitations were sent to 58 BCBAs in Southwestern Pennsylvania; 12 certificants responded to the invitation. Interested certificants responded to a set of basic professional/informational questions (length of time in the field, current job title, etc.) and confirmed they met inclusion criteria (taught while pursuing BCBA certification); in all, six current behavior analysts met inclusion criteria. The first author also recruited two students through their enrollment in a BACB® verified course sequence to receive the perspective of current BCBA-seeking students.

Sample

Six current BCBAs and two BCBA-seeking students participated in this study. Table 1 presents demographic information of the eight participants. The participants had an average of five years work experience in the field and an average age of 35. All of the participants described themselves as Caucasian/White; one was male. This study included only successful BCBA training program graduates or students about to complete their program requirements. This presents a limitation of the study because we inherently miss the experiences of non-successful students, those that complete some (or all) of the coursework/experiences but never take or successfully pass the exam. However, the experiences of successful students can provide meaningful information for future and current students, faculty members, and researchers.

Data Collection

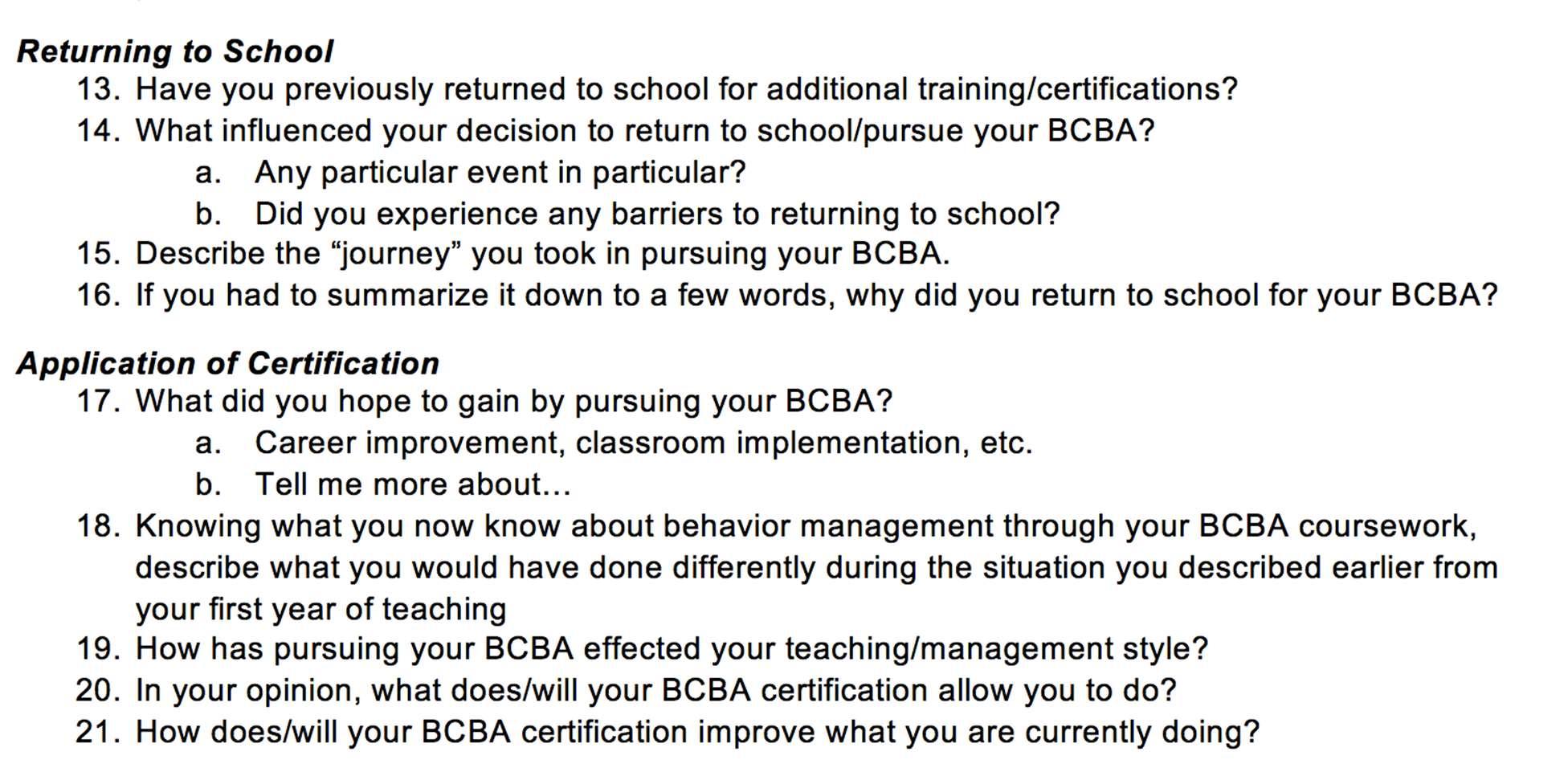

One-on-one in-person interviews were conducted with each participant, following a semistructured interview protocol (Figure 1). Each interview lasted approximately one hour and was conducted at a day, time, and location convenient for each interviewee. The interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed for analysis. All transcripts were reviewed to ensure accurate and reliable audio transcription. The participants also completed a follow-up survey addressing specific themes and questions that arose from preliminary analysis. The 16item survey collected basic demographic information and asked the participants qualitative and quantitative questions regarding their training program and supervision experiences, test-prep behaviors, and intent to remain in the field of behavior analysis.

Table 1. Participant Demographic Information

BCBA Training

Participant* Age Gender Ethnicity Current Work Years Program Type Work While Bridget 58 Female White PreK T 2016-17 In-Person BCBA only PreK T Julia 27 Female Caucasian Day care T 2015-19 In-Person MEd & BCBA Day care T Rebecca 32 Female White Teaching student fellow & doctoral 2010-12 In-Person BCBA only Lead therapist at autism or related APS for diagnoses Leah 34 Female White Founder/CEO -ABA service provider 2006-09 In-Person MEd & BCBA Preschool school for T at center-based autism Zander 32 Male Caucasian Co-founder provider – ABA service 2011-13 Online BCBA only Autism classroom T at APS Jillian 31 Female White SE for T at center-based school students with EBD 2007-10 In-Person MEd & BCBA Music T at and EBD) APS (K-8 for autism Holly 31 Female Caucasian Internal coach, (autism/MDs) APS 2013-14 Online BCBA only Classroom T at (autism/MDs) APS Melanie 35 Female White Invention Specialist & Consultant at regional educational service agency 2009-11 In-Person MEd & BCBA Full-time sub (elementary autism support then secondary emotional support) Notes: *All participant names are pseudonyms; ABA: Applied Behavior Analysis; APS: Approved Private School; EBD: Emotional Behavior Disorders; MDs: Multiple Disabilities; PreK: Pre-Kindergarten; SE: Special Education; T: Teacher

30

Figure 1. Interview Protocol

Figure 1. Interview Protocol – This figure shows the interview protocol. The participants were asked about their educational and professional history, current teaching, their experience returning to school for their BCBA, and the application of their certification. Follow-up questions were asked as necessary for clarification or more information.

Data Analysis

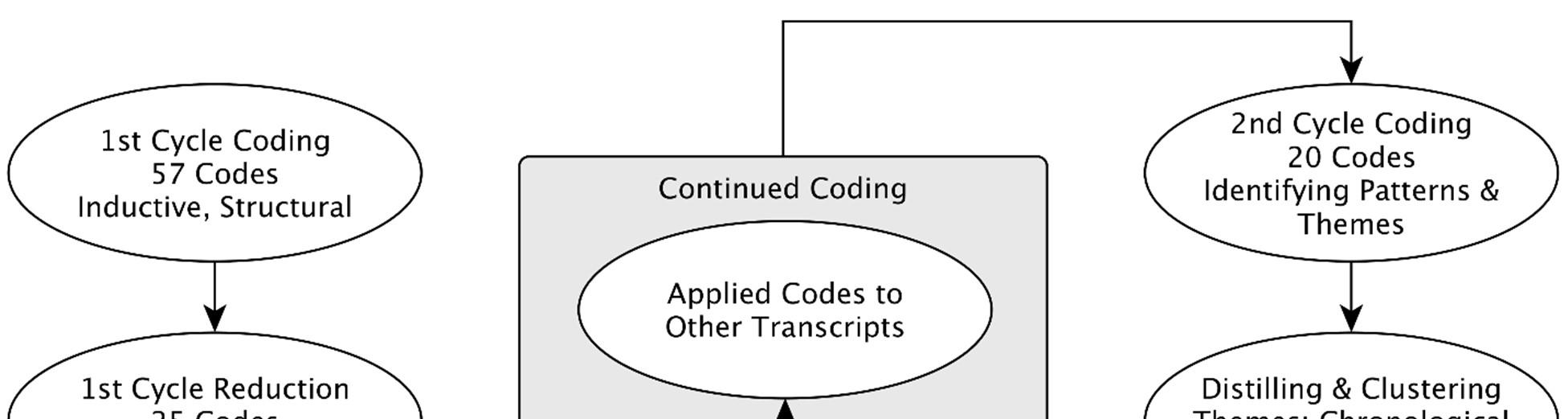

A combination of inductive and deductive coding was used to analyze the participant interviews, followed by systematic member checking to confirm the analysis. Figure 2 shows the general data analysis process.

First cycle coding. The analysis process began with the first interview transcript. The first author coded passages using inductive and holistic structural coding, applying a single code

(word or phrase) to entire passages (Saldaña, 2016). Initial codes for the passages were generated to reflect the participant’s response to the question being asked (‘question-based coding’; Saldaña, 2016). After this first round of structural coding, 57 individual codes remained. Many of these codes, however, were repeat or duplicate codes; when condensed, 25 unique codes remained. Additional groups/categories were established by taking the existing structural codes and examining them for commonalities and relationships (Saldaña, 2016). These initial codes and categories were then applied deductively to the remaining seven transcripts. During this continued coding, new inductive codes were generated as necessary. As new codes were generated, all previous transcripts were reviewed for instances of the emergent codes.

Second cycle coding. After coding all eight interviews, the first author engaged in several methods of second cycle coding. Pattern coding allowed data segments to be grouped into fewer categories and themes based on patterns of responding, agreements, and similarities in experiences (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014). Additionally, axial coding helped link categories to subcategories and identify other possible relationships between categories and subcategories (Miles et al., 2014).

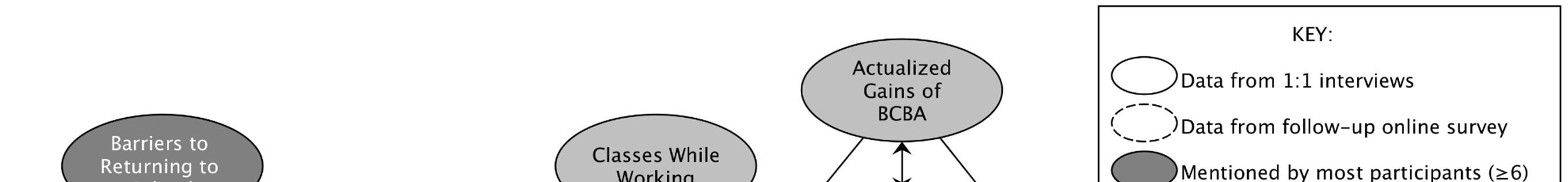

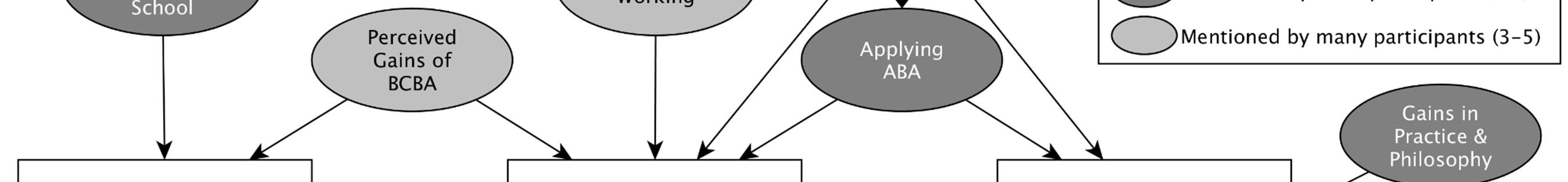

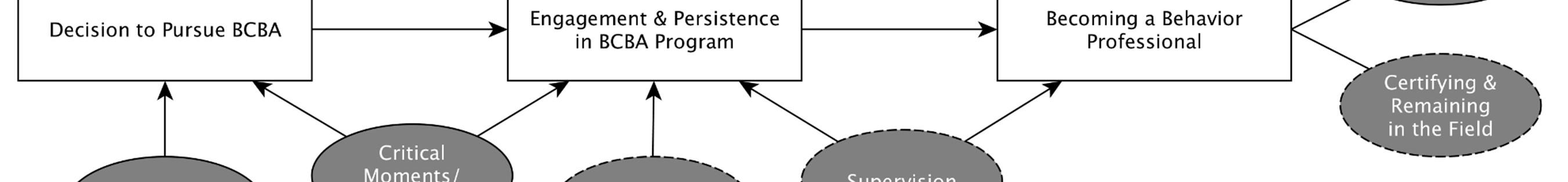

Visual display. Taken in sum, the resulting data and codes represent a chronological professional experience timeline from pre-BCBA coursework through becoming a behavior professional (Figure 3). Four distilled categories (‘History and Experiences,’ ‘Decision to Pursue BCBA,’ ‘Engagement and Persistence in BCBA Program,’ and ‘Becoming a Behavior Professional’) anchor the network display across time. Experiences surrounding each category highlight important events described by the participants. For example, when making the decision to return to school for their BCBA, the participants described pivotal ABA experiences (such as working with a behavior analyst), barriers to returning to school (such as funding and childcare), and their perceived gains of obtaining their BCBA. The key in Figure 3 identifies the number of participants that described each experience or event. There was high convergence among the participants – most participants described similar experiences before, during, and after obtaining their BCBA.

Member checking. A critical stage in our analysis was a systematic member checking process. Member checking is one method for establishing the credibility, validity, and trustworthiness of qualitative results (Creswell & Miller, 2000; Doyle, 2007). During member checking, the researcher provides study participants with raw data, preliminary themes or analysis, and/or the final narrative (Creswell & Miller, 2000). Synthesized member checking (SMC) “enables participants to add comments which are then searched for confirmation or disconfirming resonance with the analyzed study data, enhancing the credibility of results” (Birt, Scott, Cavers, Campbell, & Walter, 2016, p. 1806). During SMC, quantitative measures of engagement (response rate) and agreement (yes/no responses to accuracy and applicability of themes) are analyzed using descriptive statistics (Birt et al., 2016). Quantitatively, there were only three instances of disagreement by the participants (141/144; 97.9% agreement). These disagreements were not the result of inaccuracy of the themes, but rather divergent professional experiences. Any information or elaboration provided by the participants during SMC was incorporated into final narrative.

Figure 2. Data Analysis Process

Figure 2. Data Analysis Process – This figure shows the data analysis process for this study. The first round of coding included inductive, holistic structural coding (applying a single word or phrase to entire passages. Duplicates were removed and larger categories were created. As new codes were generated, they were applied to previously coded transcripts. The second round of coding included identifying patterns, connections, and relationships between codes and searching for confirming and divergent experiences. A chronological display was generated (Figure 3). Finally, synthesized member checking systematically ensured the credibility, validity, and trustworthiness of the analysis and results.

Member checking was completed with each participant individually, lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. During each audio-recorded session, the first author reviewed the project, presented a copy of the network display (Figure 3), and provided a concise report that included synthesized data (analysis themes) contextualized with illustrative quotes. After discussing each theme, the first author asked the participants if the theme(s) made sense (logically and empirically) and fit within their own personal and professional experiences. All quotes included in the final narrative were provided to the participants for approval, clarification, or re-wording. All member-checking documents are available upon request.

Results

The following results report the perceptions/experiences of current ABA practitioners and students. The participants described their personal and professional experiences surrounding returning to school for their BCBA certification. Taken in sum, these experiences led to the formation of a chronological experience model (Figure 3) from before returning to school, through engagement in coursework and supervision, and becoming a behavior professional.

Figure 3 Behavior Professional Experience Model

Figure 3. Behavior Professional Experience Model – This figure presents a chronological visualization of the experiences of teachers who returned to school for this BCBA. Three distilled categories (‘Decision to Pursue BCBA,’ ‘Engagement and Persistence in BCBA Program,’ and ‘Becoming a Behavior Professional’) anchor the network display. Experiences surround each category, contributing in some way. History and experiences seemed to play a role throughout the experience model and are shown as influencing each category.

34

History and Experiences

Behavior analysts come from a wide array of fields and academic disciplines. As such, they each bring a unique set of professional and personal experiences. These experiences, including family connections to special education, prior work with people with disabilities, and their educational background and training likely play an important role in the analysts’ decision to pursue their BCBA, engagement during their coursework, and continued work as a behavior professional.

Familial connection to special education. Nearly all of the analysts described deep family connections to education, special education, and people with special/exceptional needs. Five analysts had family members working in education, including general education, special education, speech-language pathology, administration, advocacy, and mental health associations. “I grew up with educators and I saw the stress” (Holly); “I have a big background from my family and special education” (Zander). These analysts had first-hand knowledge and experience with the unique and pervasive challenges that exist within education.

Analysts also described working with siblings and other family members with disabilities. These opportunities allowed them to learn and practice using positive strategies while working with them: “My aunt had a 1-year-old and a 3-year-old foster kids. I was working with them and I really enjoyed that. Because they had social and emotional delays, you had to use skills to not set them off” (Julia). “My uncle has, since like back in the 40s, a MR diagnosis. He definitely played a role in all this” (Holly).

When asked how she became interested in special education and working with this population of students, Melanie described her brother’s struggle in school:

My brother who’s ten years younger than me has a learning disability, dyslexia probably. I always remember him struggling. I’m like, “Well, why doesn’t this teacher just give him 10 math problems instead of 30 math problems?” Even as I was going through my coursework at [college], he was in high school, and he was struggling. A lot of the stuff, I would just be like, “I just don’t understand.” I just didn’t understand why people couldn’t make these little adaptations. If you want him to do this math fine, but 30 problems is not necessary. I think, even then, I was just kind of like, “That doesn’t seem right,” and so I just seemed drawn to [working with students with special needs].

This work with family members and siblings with disabilities may have pushed the analysts towards special education, and subsequently to ABA. When discussing the preliminary findings of the study, including the personal connection to the field, Leah agreed: “Siblings: A lot of people I see go back because they have siblings [or family members] on the [autism] spectrum.”

Prior work with people with disabilities. Each of the analysts described previous work with students and adults with disabilities. The certificants worked as paraprofessionals, Therapeutic Support Staff (TSS1), Registered Behavior Technicians (RBTs), or at inclusive summer camp programs. The certificants reported being drawn to the ABA field in part due to strong

1 TSSsworkdirectlywithstudentsandimplementthebehaviorplansdevelopedbyBehaviorSupport Consultants(BSCs).BSCsdonotoftenprovidedirectservicestothechild(PennsylvaniaHealthLawProject, 2011).

connections working with students with emotional or behavioral challenges during their early career experiences. During college, Rebecca worked with a student with autism: “I worked under a BCBA, and I loved it. The [student] was one of the best people I have ever met. I still talk with this mother. It was a wonderful experience for me. ”

Jillian worked with a student with multiple disabilities, including autism: “I raised my hand. I was paired up with her and we just had—there was something there” (Jillian). Then during college, “there was an opportunity to provide ABA tutoring to a young girl with autism over the summer ” (Jillian).

In the summers following high school, Zander often worked for a youth summer program. During these programs: “I was drawn to those kids who had emotional issues. I was coming up with things on my own to coach them or help them” (Zander). Holly worked at an inclusive summer program at the YMCA throughout her undergraduate studies. She said most “ were children with autism…. I learned a lot. It was interesting” (Holly).

Entered classrooms unprepared to address student behavior. Perhaps due to their early experiences with students with special needs, most participants pursued careers in special education. Two worked as TSSs or Behavioral Specialist Consultant (BSC); two worked in approved private schools (APS) for students with autism, emotional behavior disorders, and/or related disabilities; and one became a ‘supersub’ for public special education classrooms (within districts and regional educational service agencies). Prior to returning to school for their BCBA, most of the analysts (five of eight) worked in an APS; the other three worked in public elementary or secondary schools.

Those in public schools experienced ‘less intense’ behaviors, including non-compliance, defiance, and bullying, while APS teachers regularly dealt with ‘more intense’ and aggressive behaviors, including severe self-injurious behavior, biting, hair pulling, and property destruction. Despite the setting, the participants described entering the teaching workforce unprepared to address student behaviors. Behavior management (specific training in how to address and prevent student problem behaviors), was the “missing piece” (Holly) of their teacher preparation programs. It was “the most underdeveloped part of my undergrad education was behavior management” (Julia). Even for a participant who went through teacher preparation several decades ago, behavior management “ was not something they really went over ” (Bridget).

The analysts describe the pre-service training they did receive as rather incomplete:

We had one separate classroom management class, but that wasn’t related to special education at all and it was useless because it was with [pre-service teachers from different fields] and wasn’t really relevant to our field in particular… [We discussed] ways to structure the room, how to respond to talking out, but no serious behavior [management]. (Jillian)

Some analysts recall specific types of strategies; token economies and similar group contingencies were commonly included. Generally, “basic full-classroom [techniques], nothing

individualized” (Melanie). Rebecca could remember some of the topics discussed during her behavior management training, but broadly:

I think a lot of it was, in retrospect, a bit touchy-feely about making people feel included. I guess that would be a part of classroom management, creating a cultural climate that is welcoming and appropriate. And while I appreciate those things now later in life, I can't pick out specific strategies that I was taught in order to do those things. I can just tell you what those buzzwords are and say that we learned about them, but that doesn’t mean we were really taught, “Okay, how do you do that?”

Despite a passion for working with students with disabilities, including those with challenging behavior, most participants felt unprepared to address students’ emotional and behavioral needs as they started their educational careers.

Decision to Pursue BCBA

During a member-checking meeting, Zander highlighted a key aspect of our field: “The field isn’t new, but the professionalism [and credentialing] is relatively new… I don’t know many people who are like, ‘When I was 14 I wanted to be a BCBA.’ People are finding out about it, they’re stumbling across it.” When presented to other participants, they agreed: “Yeah, you have to come across it, know somebody, or have a sibling that has need of that sort of program. It’s not something you really think about becoming, unless you’re supposed to” (Bridget). “You have to be exposed to [the field of ABA] or you have no idea it exists” (Melanie). The analysts were introduced to the field through a range of serendipitous experiences. They then researched the field and profession, including possible in-person and online training programs.

Pivotal ABA Experiences. Most of the participants learned about ABA through work experiences working with students with emotional and behavioral needs and interactions with behavior professionals. Seven of the participants described learning about the field through their direct contact with ABA or a BCBA. The participants enjoyed these initial, hands-on introductions to ABA. “Once I started getting into the field and working with kids with autism, I just loved it” (Leah). Several provided services in the home and worked with families. They often recounted stories of positive interactions with students and families: “I actually learned a lot more about ABA from the individual’s mother than anyone else. She was a really active ingredient in his exposure to intervention” (Rebecca). Positive collaborative efforts among behavior professionals and families were critical:

Then over the summer, there was an opportunity to provide ABA tutoring to a young girl with autism… It changed everything, because I had no idea what ABA was. The parent and the BCBA trained me and I wound up working a lot of hours a week. We were implementing the programs that the BCBA wrote and the parent was very familiar with the programs and was involved with training the staff. (Jillian)

While working in these settings, colleagues and supervisors pushed the participants to pursue their BCBA. “One of my BSCs that was supervising me, she was like, “I think you’re really great at this” (Leah). Zander also recalled the support of his supervisors in pushing him to pursue his BCBA:

As soon as I got my job, and they were like, “You’re gonna be good,” I think we talked a little bit about there were some people who got it and some people that don’t. I was recognized by some people who were like, “Look. He gets it.” [Supervisor] really pushed, “Go do it online.”

Melanie worked with two behavior specialists, at least one of whom was a BCBA. During a long-term substitute position in an emotional support classroom, Melanie reached out for help working with a challenging student. The behavior specialist helped her with the specific student, but also helped her be “able to see the growth just in adding some reinforcement and being consistent and the right type of prompting” (Melanie). Later on, Melanie had the opportunity to work with a behavior specialist who formally introduced her to ABA: “She was ‘ABA certified,’ and I was like, ‘What does that mean?’ She explained it to me, and I looked into it.”

Returning to school: smooth transitions and perceived gains. The participants were asked about the process of returning to school. By and large, the participants described smooth transitions due in part to their active efforts to manage any potential barriers, including career, school, and partner/family commitments. Interestingly, none of the teachers working at an approved private school (APS) while returning to school for their BCBA noted significant barriers related to pursuing their BCBA, in part because ABA was already integrated into their work lives.

Participants took steps to ensure they were prepared to get through program successfully. For example, Leah described herself as “ a very task-oriented person ” who was “prepared and ready” for the program. Jillian and her husband discussed the idea of her returning to school shortly after graduating from college. While she was nervous at the time, she now is glad she decided to “ go right away because now I have two young kids and I’ll be done with everything at a pretty young age ” (Jillian).

Two participants, both paraprofessionals at an APS, completed their coursework online and reported easy transitions back to school. For these analysts, they saw real benefit in completing the coursework online; online programs tend to cost less than in person programs. Holly “knew [she] wanted to do online. It was significantly cheaper than the other schools, significantly.” For Zander, doing an online program was “ a no-brainer. It is $900.00 a class. [Comparable program] is literally three times the cost.” On top of being financially smart, Holly wanted her greatest chance for success in passing the BCBA exam. “Somebody somewhere told me, ‘Hey, look up the pass rates,’ and [program] was really high, so I decided I’m just gonna go for that” (Holly).

The participants perceived meaningful gains from completing the coursework and obtaining their BCBA. These perceived gains likely motivated the future-analysts to persevere through their training programs. As full-time teachers, the participants perceived the coursework as an opportunity to better their practice or learn skills to help students. Rebecca had made the jump from a preschool classroom to an APS for autism and related disabilities, and reported: “I wanted to be better at what I was doing. I think that initially that’s all I wanted, was just to be better at my job.” Bridget “wanted to run my classroom positively and just feel like I was more in control

of the behaviors that were happening in my [Pre-K] classroom.” She believed the BCBA training would help “bring some sort of new life into my classroom.”

For several participants, obtaining their BCBA would help them better serve students and families. When Leah was introduced to the field, she “thought that the field would be very rewarding… I just wanted to make a difference, I guess, and be in a field that’s rewarding. [I enjoyed] interacting with families and different people and cultures.” Julia’s focus was on working with children: “I’m doing it to gain these skills so that I can help all different kinds of kids… Someday there will be somebody who needs me to have that skill in order to have a breakthrough.” Bridget was excited to learn more to help her teaching and others she works with: “What I learned was something I could really bring back to other teachers and share with them. It’s not just an improvement for me, but I can help a whole bunch of people.”

Engagement & Persistence in BCBA Program

Once in training programs, participants had to balance coursework with work commitments. This process was supported by the resonance between course content and their work, and positive supervision experiences.

Classes while working. The participants described the challenges associated with being a fulltime teacher and a student; however, they appreciated the practical applications of their coursework.

It was challenging, you know working full time and then come home and go to class usually two nights a week. I was a part-time student so it took me quite a while to finish up my coursework… The nights I was not in class, I was writing or reading research articles. (Leah)

For Julia, a current student and full-time daycare teacher, “It’s a lot of time management, a lot of lists, a lot of sleepless nights, especially with two kids.”

The analysts found their program experience rewarding and benefited from supportive, knowledgeable professors. “They were supportive and engaging, and made the material accessible to all students… [They] kept us motivated by ensuring that we understood the materials” (Julia). Many analysts’ previous or current work experiences helped them connect with the content:

I’m not saying it was easy stuff, but some of the coursework, I think because I already had such an experience in low incidence and in that population, that when in some of my classes they were like, “Hey, you have to write a plan,” I was like, “Here, I already have one.” (Melanie)

I think that it was very helpful to be working in an APS as a music teacher when I was in my coursework. It was very helpful because I could immediately apply it to a situation that was going on with a student. I definitely think that working while taking coursework is the way to go… because you can apply it right away. Even if you’re not getting your

supervision officially yet, when you’re taking that coursework, if you’re working with kids you can say, “Oh, that’s just like what Johnny does.” (Jillian)

Teachers working in public school settings benefited from real-life/practical examples provided during their courses. “My teacher used a variety of teaching methods, including visuals, repetition, and real-life examples” (Julia). Jillian’s professors “had high standards and practical examples that helped me understand the concepts.” These analysts were also able to try some of the skills they learned in their own classrooms: “I loved applying what I was learning in my practicum experiences… There is carryover [between coursework and current teaching], it’s just putting labels to some of the things I was already doing” (Julia).

Teachers working in an APS (where they also completed their supervised internship experience) found immense benefit in their ability to immediately implement the skills they learned in their coursework. “Yeah, the material was hard, but I think it was a lot easier for me because I was living and breathing it every day” (Holly). Rebecca described the process of being in school while working full time: “It was hell, but my coursework and supervision hours and working full time all in the same place afforded me the ability to do that across most of the concepts I learned.” These analysts benefited from being surrounded by knowledgeable and supportive staff and they saw great value in their experiences:

The professors were people that I worked for so I had access to them every day… I think without that piece, I would not have been as successful… It’s a different level of practice that I am absolutely grateful for. It was hell, but grateful for it… I think that there was much less of a gap between this ‘concept’ and ‘practice,’ so the benefit and the strength there, in my opinion, was “Oh, you learned that yesterday, let’s do that today.” Or I could say, “I learned about this, I’ve never seen this type of programing, this schedule, whatever. Is there anybody I could work with that might give me that experience?” “Oh sure, take this hour with this student and then you will have done or seen that thing.” And that, to me, is the strongest link. (Rebecca).

Supervision. The analysts had a mix of supervision experiences: half (four) completed intensive practicum experiences, three completed supervised independent fieldworks (at their current APS), and one combined an intensive practicum experience and supervised independent fieldwork. Public school teachers (and a music teacher at an APS) were supervised by someone affiliated with the training program/university (or university-provided). Teachers working at an APS while taking courses were typically supervised by a professional in their school/program (or in-house). Each group described specific strengths and benefits of their supervisors and supervision experiences. The participants also described the importance of high-quality supervision.

University-provided supervision. Overall, the participants had positive experiences with university-provided supervision and supervisors. They appreciated their supervisors challenging them to see behavior in a different way, answering questions, and explaining how to apply ABA concepts into their day-to-day work.

Both Bridget and Julia described their supervision experience as “excellent.” Bridget’s supervisors:

Were interested and always willing to discuss things that I was thinking about and grappling with. They had valuable input and challenged me to think about things from other perspectives… It really helped me think about how I look at things and how I approach a [behavior] problem.

Julia appreciated that her supervisors “allowed me to try different behavioral interventions, and come to conclusions regarding their efficacy on my own. I also had group supervision once per week, which was useful; it allowed us to hash out difficulties as a group.” Julia spoke very highly of her supervisor: “She encourages independent thought. I ask her a question, and she’s like, ‘Hm. What do you think? What procedures are in place?’ And she’s teaching me how to change [my] language to be more appropriate to non-BCBAs.” Melanie felt like her supervisor “ was a great match” for her:

He really let me guide supervision, which I liked. He was knowledgeable and fair, but I was like, “Here’s my question.” I’d come with the questions, and we’d talk about it, and then he’d apply it back to my classroom. Then he would come in the next time and do something on that, or talk about it or show it, which really worked for me, so that was really great.

Two participants mentioned specific missing components of their university-provided supervision experiences. As a music teacher in an APS while completing her coursework and supervision, Jillian saw groups of students for 45 minutes every three days:

My supervisor found it a challenge to tell me what to do because it was just different than what you typically see for a BCBA. It was tough because I didn't have [the students] all day; it's hard to get any behavioral momentum going.

While Melanie really enjoyed her supervision experience, she felt it lacked a diversity of experiences:

I think that one drawback to my supervision was that it was done in one setting. Because I was working full-time, I did not have much room for variety. I wish I could have had more opportunity to work with kids at different levels and explore [verbal behavior] more.

In-house supervision. Participants receiving in-house supervision found the experience incredibly rewarding. These supervisors were often program directors, instructors, or other behavior professionals that the participants were already interacting with frequently. In several cases, the BCBA supervisor was also the person who pushed them to pursue the certification. For these in-house supervisees, direct and on-going access to seasoned behavior professionals allowed them to quickly understand and apply the material into their daily work.

Holly’s supervisor was “readily available to observe and to answer questions. She always gave appropriate feedback and thorough answers to my questions.” For Rebecca and Holly, immediate and continual access to their BCBA supervisor helped them review and practice skills described in their coursework:

I think without that [in-house supervision], I would not have been as successful… My boss saw me doing work every day [not once or twice a week]… That meant that we could make changes to programming, and we could practice implementing different things rapidly and in the way that it’s designed to be done. We could problem solve on Tuesday after making a decision on Monday, because we saw each other every day… If your supervisor is your teacher, and there when you’re doing the thing you just learned, you have access to immediate, in-situ feedback from your supervisor. Not just once a week when they visit, but every day. If you look at the literature on when feedback is delivered and how it’s delivered, that’s the difference between immediate versus potentially days of delay. (Rebecca)

[In-house supervision] made it so much easier, and it helped me understand how to apply what I was learning in class to what I was actually doing every day. It was just nice to have her there because she was there almost every day… It’s nice to have somebody who’s super available that can help you out and she was right there. (Holly)

Although varied, the analysts’ supervision experiences highlight the importance of high-quality supervision. Put simply, “Someone who’s trained in behavior analysis and was a good supervisor not only shaped me but shaped so many other analysts. That’s, to me, what the biggest miracle is for good teaching – good supervision. Really, really good supervision” (Zander).

Becoming a Behavior Professional

Once completing the course, supervision, and examination requirements, the participants become part of a growing group of passionate behavior professionals. The analysts saw important professional and philosophical gains from their coursework and experiences. Continued gains and a dedication to the field likely motivates analysts to remain in the field.

Obtaining certification. All of the current analysts (excluding the two BCBA-seeking students) in this study successfully completed the requirements to become a BCBA. Five out of six of those analysts passed the exam on their first try. Both BCBA students were in the middle stage of their training and supervision requirements. At the time of member checking, Julia had completed all but one course and nearly all of her supervision hours. She plans to sit for the exam in several months. Bridget completed the courses and a semester of supervised independent fieldwork in her classroom. She since decided not to pursue the certification, citing her “stress about the exam ” and her own potential upcoming retirement: “the knowledge I have gained and learned has been invaluable. I decided to take the knowledge that I have and apply it to my work and hopefully to help colleagues” (Bridget).

Actualized gains. Prior to returning to school, the participants perceived important gains from gaining their BCBA. These gains were likely exchanged for actualized gains throughout their

training program experience and subsequent work in the field. Interestingly, participants described their actualized gains in two broad categories: gains in practice, and a change in professional philosophy.

“It made me a better teacher” – Gains in practice. The participants saw changes in their own behavior as they went through their training programs. Both current BCBA students experienced connections between their training programs and currently classroom teaching. Bridget also saw gains in her practice:

I’m much more aware of being consistent… I definitely feel much more confident in the choices I make. And I feel like if I am going to put in place some sort of behavior change program, I feel much more confident, ‘Oh this is going to work.’ And I try to focus on the idea that you really need to think about what’s driving the behavior. Look at that behavior, see how you can change what happens before the behavior. Let’s get in there and if we know this is what’s motivating the behavior, what can we do to change it, stop it before it even happens? I really feel that is the best thing I learned: be proactive, stop it before it even starts.

Analysts recalled the professional gains they made during their training programs:

I really saw the changes in the students. Working with them for so long, I could really see that applied behavior analysis was making a big difference in their lives. Just those little successes leading up to a bigger success was really satisfying for me as a clinician. (Jillian)

I think I just pick smarter strategies. It helped me realize to stop and think about why somebody’s doing what they’re doing and pick the function, treat the function. I didn’t really know how to do that before so that helped me. (Holly)

Analysts also described long-lasting gains in professional practice:

I mean just pairing, building rapport, relationships, making sure those are in place, and being able to manage in a classroom, group instruction and contingencies, and just the whole works. I mean, as a teacher, the systematic teaching and instruction, and analysis of goals and academics, and just the whole works. I mean managing classrooms, managing individuals on their own. (Leah)

It made the way I viewed what I did much differently… I’m very much now focused on: You lack the skills. I need to teach you the skills, and how do I teach the skills? Your behavior doesn’t need to be necessarily punished. I need to teach you the skills to then learn to behave appropriately. (Melanie)

During her interview, Leah recounted the things she has gained as a result of obtaining her BCBA:

[Gaining my BCBA] has allowed me to start a company, help more families, and do the right thing, the quality thing. I think it gives you a different perspective on the world and everything that’s going on around you… The BCBA certificate made me see that [ABA] is a super tool for teaching. (Leah)

“Behavior [analysis] isn’t a type of teaching” – Changes in professional philosophy. Many analysts described additional philosophical changes as a result of their training. For Zander, “there was a method to the madness, and I saw the method to the madness… I just see things now through the lens of behaviorism.” Melanie said that pursuing the BCBA “opened up a whole new world of what was available; a new way of thinking and doing things.” For Julia, “ABA has taught me to analyze behaviors in a new way… ABA is a mindset, one cannot simply ‘unsee’ ABA” (Julia). Jillian saw multiple changes, “I look at everything through the lens of ABA both professionally and personally.” ABA brought clarity for Bridget: “It does change the way you look at how people behave and think about what’s causing it and what you can do to change it… Things make a little more sense and you can actually do something about it.” Leah said it simply, “ABA is a part of everything that we do.”

Dedication to the Field

During a post-interview follow-up survey, the analysts were asked to rate “On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being ‘not at all’ and 10 being ‘extremely,’ how dedicated/passionate are you to the field of ABA?” The analysts had a mean ‘dedication rating’ of 9.25 out of 10 (range: 8 – 10). Importantly, the analysts were asked to operationalize what their ‘very dedicated’ to ‘extremely dedicated’ ratings meant to them. The analysts often described the effectiveness of ABA: “The strategies we're taught to use are scientifically valid, and this gives teachers the confidence to do their jobs more fully” (Julia). “I believe that ABA works and when applied properly can help kids improve behaviors, learn skills, and lead meaningful lives” (Melanie). “I believe in the power of the science to improve the lives of those I work with” (Zander).

During the follow-up survey, the participants were also asked about their intentions of remaining in the ABA field. Seven of the participants planned to remain in the field for the foreseeable future. Citing her own potential upcoming retirement, Bridget decided to use the knowledge she gains from her coursework to enrich her classroom and support other teachers. For Julia: “I plan to earn my BCBA by 2020 and possibly go on to teach at the university level and supervise other young aspiring BCBA's. The job security is also quite a perk.” Every certified analyst in the study planned to remain in the field for the rest of their professional careers. Rebecca said, “I will be here forever… it is what I love to do.” Zander said he would remain in the field of ABA “for life… I really love what I do.” Holly plans “ on staying forever... I love the field and the population of individuals with whom I work. The science just makes sense to me -I see how it applies to all aspects of behavior.” Melanie said simply, "I love what I do!” She plans to work in ABA “for the rest of my career... I may not stay in the school systems or work in the same setting I am in now, but I do believe that will stay in the field of ABA for the remainder of my career ” (Melanie).

Discussion

This article presents some of the first qualitative research about the experience of behavior analysts before, during, and after completing their training programs. Guiding this work were the following research questions: (1) What brought these teachers to the field of ABA? (2) How would they describe their training program and supervision experiences? (3) What actualized gains resulted from their training? A common narrative emerged describing the professional trajectory of BCBAs that came to the field after beginning their career in other educational positions. Prior to returning to school for their BCBA, the participants each described pivotal experiences with ABA or behavior professionals through their work as classroom teachers, paraprofessionals, TSSs, etc. These experiences allowed the future analysts to see its effectiveness first-hand or have their potential and skill set recognized by current behavior analysts. The participants described the process of completing their coursework requirements while working as full-time teachers. They acknowledged that it was a lot of work, but they appreciated the practical applications of the coursework within their own classrooms. The participants described their program experiences as worthwhile and benefitted from supported, knowledgeable professors. During both university-provided and in-house supervision, participants benefited from trying different behavior interventions, collecting data, and judging the effectiveness for themselves as well as incorporating ABA principles into their day-to-day work as teachers. As a result of completing their training programs, the participants described distinct gains in their knowledge of ABA skills and practice, including changes to professional identity.

Many of the participants described a history working with students with disabilities, including populations whom typically receive ABA services (autism spectrum disorders, etc.). Participants also described their desire to enhance and refine their professional knowledge/skills to better continue serving their clients, students, and families, enhance their own classroom teaching, and support other teachers. Teachers’ sense of success in working with their students, as well as school and classroom supports, influence their decision to remain in the field (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003). The participants’ prior experiences with students and teaching played an important role in how they discovered field. These historical, as well as current, experiences likely increase their dedication to the field. Increasing the visibility and accessibility of behavior analysis may provide an important tool for teachers who are actively considering leaving the field due to commonly cited concerns of student disruptive behavior (Little, 2005) as well a lack of training or support regarding classroom management (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003).

An important finding of this study was that behavior professionals are often “introduced” to the field through pivotal ABA experiences, including interactions with current behavior professionals. The participants also described receiving support and guidance from current behavior analysts, program supervisors, and others in pursuing and selecting training programs and support throughout their coursework and internships. Given the professional discipline of ABA is relatively new and not within every college or university, this provides some insight into how people come to find, or even stumble across, the field. Despite all being education professionals, each participant required an introduction to the field. Initial positive ABA experiences may influence program decision, engagement, and eventual success (obtaining a BCBA). While a poor ABA experience may lead to misunderstandings or misconceptions about the field. High-quality collegial relationships among educators and educational professionals can spur teacher development, and improve teacher knowledge, satisfaction, and classroom cultures

(Shah, 2012). Results from this exploratory study and existing literature promote the need for reflection and discussion on how to increase exposure of ABA to future clients and practitioners, supporting the current push of the field for the purposeful dissemination of our science.

The importance of these ABA experiences is also practically relevant. Current behavior professionals will likely interact with many potential future analysts over the course of their professional careers. These initial relational contacts with the field or other behavior professionals may promote future analysts to research the field and training options, ultimately becoming BCBAs themselves. Both these initial contacts and general day-to-day interactions with members outside our professional community have important implications. Behavior professionals should work as ABA ‘ambassadors’ – sharing the science thoughtfully and accurately while directly addressing misunderstanding or misconceptions. Current behavior analysts should also recognize good future practitioners, helping us grow our field with dedicated professionals. These two skills, dissemination and recognition, fit well within our ethical obligations as behavior analysts.

As our field experiences steady professional growth, important professional discussions have begun, including program quality and aspects of effective professional supervision. An important viewpoint missing is the collective voices and ideas of our practitioners. A recent special series on BCBA supervision recognized that good supervision is important for future analysts. This study is the first published data about supervision experiences directly from successful analysts. Results from this study show two divergent models of supervision: university-provided supervision (e.g., the training program provides a supervisor whom visits the supervisees’ assigned internship location) and in-house supervision (e.g., the student works within an ABA-service provider [APS, etc.] and is supervised by a behavior professional from that provider). Although varied, analysts’ supervision experiences highlight the importance of high-quality supervision. Given the results of this work and its connection to on-going conversations within our growing field, additional, focused research on the experiences of both supervisors and supervisees is warranted.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, this study included a small sub-set of behavior analysts, those that returned to school for their BCBA while teaching full-time and currently living within a small geographic region. Despite this, the convergence of responses/experiences as well as the intensive participant engagement helps the authors believe that program experiences are likely common for other BCBA-seeking students. While a survey would have likely produced a larger sample of successful analysts and BCBA-seeking students, one-on-one interviews allowed for the collection of in-depth, contextual information. Systematic qualitative research allowed for important clarification and follow-up questions regarding participant decision-making, as well as the ability to confirm and refine initial findings. This research established an initial behavior professional experience model (Figure 3), which can now be subjected to testing and refinement via large-scale follow-up work already underway. Second, the six interviewed analysts successfully completed the training program and continuing education requirements to obtain (and maintain) their BCBA certification. As such, the present study does not include the experiences of those who, for whatever reason(s), did not successfully obtain their BCBA. Understanding the experiences around which these students were unable to earn their BCBA is a critically important next step for researchers and training programs.

Several factors lead to the need to understand the experiences of behavior analysts. As an emerging professional field, we have established formalized entry requirements (coursework, supervised internship, and examination), instituted task/skill requirements (and adapted them based on job analyses), and incorporated ethical training requirements for all analysts. These developments have occurred as the demand for behavior professionals, specifically BCBAs, continues to rise. In order to continue growing, the field should ensure we have skilled, passionate analysts in the field working with clients and disseminating our science – our dedicated professionals can provide an important voice often missing from the field. Continued conversations with practicing professionals may provide unique perspectives and solutions to the current and future challenges of our field. As the field continues to grow, professional needs and policy implications may be better understood through including practitioner voice and input. While that happens, training programs may want to consider providing strategies or trainings to support future analysts’ thoughtful and purposeful dissemination, given the need for ABA ambassadors.

References

Ahern, W.H., Green, G., Riordan, M.M., & Weatherly, N.L. (2015). Evaluating the quality of behavior analytic practitioner training programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(2), 149-151. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0085-9 Association of Professional Behavior Analysts (2015). 2014 U.S. professional employment survey: A preliminary report. Retrieved from http://www.csun.edu/~bcba/2014-APBAEmployment-Survey-Prelim-Rept.pdf Association for Science in Autism Treatment (n.d.). Applied behavior analysis. Retrieved from https://www.asatonline.org/ Behavior Analyst Certification Board (n.d). BACB certificant data. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2018). BCBA requirements. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/bcba/bcba-requirements/ Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010-2017. Littleton, CO: Author. Retreived from https://www.bacb.com/wpcontent/uploads/Burning_Glass_20180614.pdf Becirevic, A. (2014). Ask the experts: How can new students defend behavior analysis from misunderstandings? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 7(2), 138-140. doi:10.1007/s40617014-0019-y Becirevic, A. (2015). The experts have spoken!: A reply to four commentaries. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(1), 113. doi:10.1007/s40617-014-0038-8 Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802-1811. doi:10.1177/104973231665487 Blydenburg, D.M. & Diller, J.W. (2016). Evaluating components of behavior-analytic training programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(2), 179-183. doi:10.1007/s40617-016-0123-2 Bose, P. & Hinojosa, J. (2008). Reported experiences from occupational therapists interacting with teachers in inclusive early childhood classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(3), 289-297. doi:10.5014/ajot.62.3.289

Bucklin, B.R., Alvero, A.M., Dickinson, A.M., Austin, J., & Jackson, A.K (2000). Industrialorganizational psychology and organizational behavior management: An objective comparison. Journal of Organization Behavior Management, 20(2), 27-75. doi:10.1300/J075v20n02_03 Burning Glass. (2015). US behavior analyst workforce: Understanding the national demand for behavior analysts. Retrieved from http://bacb.com/workforce-demand-report Carr, J.E. & Nosik, M.R. (2017). Professional credentialing of practicing behavior analysts. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4, 3-8. doi:10.1177/2372732216685861 Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). (2015, February 24). Treatment | Autism spectrum disorder. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/treatment.html Creswell, J.W. & Miller, D.L (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124-130. Deochand, N. & Fuqua, R.W. (2016). BACB certification trends: State of the states (1999 to 2014). Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(3), 243-252. doi:10.1007/s40617-016-0118-z Doyle, S. (2007). Member checking with older women: A framework for negotiating meaning. Health Care for Women International, 8(10), 888-908. doi:10.1080/07399330701615325 Dixon, M.R., Reed, D.D., Smith, T., Belisle, J., & Jackson, R.E. (2015). Research rankings of behavior analytic graduate training programs and their faculty. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(1), 7-15. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0057-0 Dixon, D.R., Vogel, T. & Tarbox, J. (2012). A brief history of functional analysis and applied behavior analysis. In J.L. Matson (Ed.), Functional assessment for challenging behaviors (1st ed., pp. 3-24). Tarzana, CA: Springer Science and Business Media Franks, S.B., Mata, F.C., Wofford, E., Briggs, A.M., LeBlanc, L.A., Carr, J.E., & Lazarte, A.A. (2013). The effects of behavioral parent training on placement outcomes of biological families in a state child welfare system. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(4), 377382. doi:10.1177/1049731513492006 Geller, E.S. (2005). Behavior-based safety and occupational risk management. Behavior Modification, 29(3), 539-561. doi:10.1177/0145445504273287 Hagopian, L.P., Hardesty, S.L., & Gregory, M. (2015). Overview and summary of scientific support for applied behavior analysis. Retrieved from https://www.kennedykrieger.org/ Heinicke, M.R. & Carr, J.E. (2014). Applied behavior analysis in acquired brain injury rehabilitation: A meta-analysis of single-case design intervention research. Behavioral Interventions, 29(2), 77-105. doi:10.1002/bin.1380 Iwata, B.A. (2015). Metrics of quality in graduate training. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(2), 136-137. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0076-x Jacobson, J. W., & Holburn, S. (2004). History and current status of applied behavior analysis in developmental disabilities. In J. L. Matson, R. B. Laud, & M. L. Matson (Eds.), Behavior modification for persons with developmental disabilities: Treatments and supports (Vol. 1, pp. 1–32). Kingston: NADD Press. Johnson, S.M. (2006). The workplace matters: Teacher quality, retention, and effectiveness. Washington DC: National Education Association. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED495822 Johnson, S.M., Berg, J.H., & Donaldson, M.L. (2005). Who stays in teaching and why: A review of the literature on teacher retention. Boston: Harvard Graduate School of Education, Project on the Next Generation of Teachers

Johnson, S.M. & Birkeland, S.E. (2003). Pursuing a “sense of success”: New teachers explain their career decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 581-617. doi:10.3102/00028312040003581 Johnson, S.M., Kraft, M.A., & Papay, J.P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record (Online), 114(10), 1-39. Retrieved from http://www.tcrecord.org/content.asp?contentid=16685 LeBlanc, L.A. & Luiselli, J.K. (2016). Refining supervisory practices in the field of behavior analysis: Introduction to the special section on supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 271-273. doi:10.1007/s40617-016-0156-6 Little, E. (2005). Secondary school teachers’ perception of students’ problem behaviours. Exceptional Psychology, 25(4), 369-377. doi:10.1080/01443410500041516 Maguire R.W. & Allen, R.F. (2015). Another perspective on research as a measure of highquality practitioner training: a Response to Dixon, Reed, Smith, Belisle, and Jackson. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(2), 154-155. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0087-7 Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. Morris, E.K., Altus, D.E., & Smith, N.G. (2013). A study in the founding of applied behavior analysis through its publications. The Behavior Analyst, 36(1), 73-107. doi:10.1007/bf03392293 Morrison, S.C., Lincoln, M.A., & Reed, V.A. (2011). How experienced speech-language pathologists learn to work on teams. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(4), 369-377. doi:10.3109/17549507.2011.529941 National Autism Center (2015). Findings and conclusions: National standards project, phase 2. Randolph, MA: National Autism Center Pennsylvania Health Law Project (2011). Understanding “wraparound” services for children in HealthChoices. Retrieved from http://www.phlp.org/ Proctor, B.E. & Steadman, T. (2003). Job satisfaction, burnout, and perceived effectiveness of “in-house” versus traditional school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 40(2), 237-243. doi:10.1002/pits.10082 Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd edition). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Shah, M. (2012). The importance and benefits of teacher collegiality in schools – A literature review. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1242-1246. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.282 Silverman, K., Roll, J.M., & Higgins, S.T. (2008). Introduction to the special issue on the behavior analysis and treatment of drug addiction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(4), 471-480. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-471 Silverman, K., Wong, C. J., Needham, M., Diemer, K. N., Knealing, T., Crone-Todd, D., … Kolodner, K. (2007). A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(3), 387-410. doi:10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387 Slifer, K.J. & Amari, A. (2009). Behavior management for children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 15(2), 144-151. doi:10.1002/ddrr.60

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1999). Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health Volkmar, F., Siegel, M., Woodbury-Smith, M., King, B., McCraken, J., State, M., & the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Committee on Quality Issues (2014). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(8), 237-257. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.013 Wong, C., Odom. S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A.W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., … Schultz, T.R. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group

About the Authors

Justin N. Coy, M.Ed., BCBA is a Ph.D. Candidate and Graduate Student Researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. Justin is also a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). Justin’s mixed-methods research explores the experiences of behavior professionals, effective dissemination of behavior-analytic practices, and pre-service teacher preparation in classroom management strategies. Prior to his doctoral studies, Justin was an inclusion special education teacher in Loudoun County, Virginia, working with students with and without disabilities from kindergarten through 4th grade.

Jennifer L. Russell, Ph.D holds a joint appointment at the University of Pittsburgh as associate professor in the School of Education and Research Scientist at the Learning Research and Development Center. Her research examines policy and other educational improvement initiatives through an organizational perspective. Her work examines issues such as the way schools and systems organize to support students with special needs and how networks and other forms of research-practice partnerships are organized to accelerate systemic improvements that help educators address persistent problems of practice.