Regulations in Context

Sustainable strategies for the development and requalification of Nunavik’s village

s

Near Kuujjuaq, Nunavik. Photograph by Maxime Vaillancourt-CosseAe (2024).

Funding Home as Territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc;on in Nunavik has received support and funding from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corpora;on as part of the Northern Access Round 3: Supply Chain Solu;ons for Northern and Remote Housing that supports innova;ve solu;ons that remove barriers to increase Canada's housing supply.

Project Home as Territory: A Blueprint for Community-driven Housing Produc<on in Nunavik aims to foster Inuit autonomy and to invent new forms of engagement between North and South when it comes to meaningful dwelling places.

The Blueprint promotes rich and open intercultural understanding and exchanges by tackling three interdependent “chan;ers” [Building Autonomy • Building Capacity • Building Houses]. Flexible and open to complex ideas, the Blueprint provides paths or i;neraries for inven;ng Stories (or Shared visions), as opportuni;es for greater empowerment.

Stories take shape from a chan;er, and are built around a selec;on of promising Mo;va;ons, Assets, and Tools, such as this booklet: Tool 4 • Regula<ons in Context

Chan2er [Building Capacity] Learning and fostering, especially among Inuit youth, the skills needed to meet contemporary challenges and support innova;on.

[Building Houses] Offering choices within a variety of housing types and tenure paUerns, as well as sustainable construc;on techniques and materials that are adapted to the Nunavik territory.

Research

Text

Edi2on

Habiter le Nord québécois École d’architecture, Université Laval, Québec

Samuel Boudreault, Maxime Vaillancourt-CosseUe, CharloUe Audifax Gauthier

Samuel Boudreault

Introduc1on

How can we indigenize the policies that we are facing in our communi6es? How can we indigenize the requirements that are made, for example the building codes? How can we have an input, our own Inuit ways? Because Inuit have knowledge as well.

Hilda Snowball, Visions for the future: towards truly Northern living environments Panel discussion, 21st Inuit Studies Conference, Montreal (October 3, 2019)

Culturally appropriate regula*ons could be designed to reflect Inuit communi*es’ vision and goals, enhancing the quality of the built environment and, therefore their residents’ quality of life. The following pages iden*fy regula*ons opportuni*es at the intersec*on of two ‘chan*ers’ of the Home as Territory research project:

• The first sec*on Municipal by-laws to plan desirable villages (which relates to the chan*er Building Homes) explores how quality principles of urban design can support a context-sensi*ve planning focused on revitalizing Northern Villages’ cores. This also includes form-based coding, an innova*ve mean of regula*on that may embody a comprehensive understanding of the Land and its value.

• The second sec*on Legal framework to develop northern construc=on exper=se (which relates to the chan*er Building Capacity) examines how legal and ins*tu*onal frameworks can support the development of northern construc*on exper*se in Nunavik. Par*cularly, through alterna*ve agreements and learning paths, as well as ways of adap*ng construc*on schedules and prac*ces to regional reali*es

1. Municipal by-laws to plan desirable villages

The villages of Nunavik are currently laid out in a uniform manner, reflec*ng the suburban planning models of the southern regions of province of Québec. However, each village has dis*nct physical and cultural features that deserve careful a\en*on – features that can be preserved and celebrated through context-specific regula*ons. Such planning could be considered for the quali*es it can foster, such as innova*ve housing types, human-scaled mee*ng places and pathways, overall safety

Zoning by-laws usually focus on the separa*on of land uses and prescrip*ve parameters such as setbacks, parking requirements, gross floor area and building height to regulate and impose requirements.

Municipal by-laws could be developed otherwise by:

• Defining objec*ves for culturally appropriate design suppor*ng the Nunavik Inuit way-of-life and enforce measures to preserve community iden*ty.

• Implemen*ng measures to address challenges related to regional specifici*es, including how construc*on projects contribute to the community’s climate resilience.

• Iden*fying other community priori*es, for example:

- Elder-friendly communi*es and increased accessibility: Crea*ng a more inclusive community for people of all ages and abili*es, as well as suppor*ng aging in place.

- Increased walkability: Providing safe, comfortable and pleasant pedestrian paths to access services and goods, as not all Nunavimmiut (Nunavik’s inhabitants) have a vehicle.

- ATVs and snowmobiles: Integrate other types of transporta*on when designing the road network and access paths within communi*es.

- Other priori*es impac*ng community and urban planning.

The way in which regula*ons are designed has its part to play to relieve pressure upon precious Land (village footprint), municipal services (roads and deliveries) and community facili*es (workplaces, stores and services). In support, principles of urban design can guide the defini*on of objec*ves, the iden*fica*on of priori*es and the implementa*on of well-suited measures.

1.1 Housing and infrastructures layout

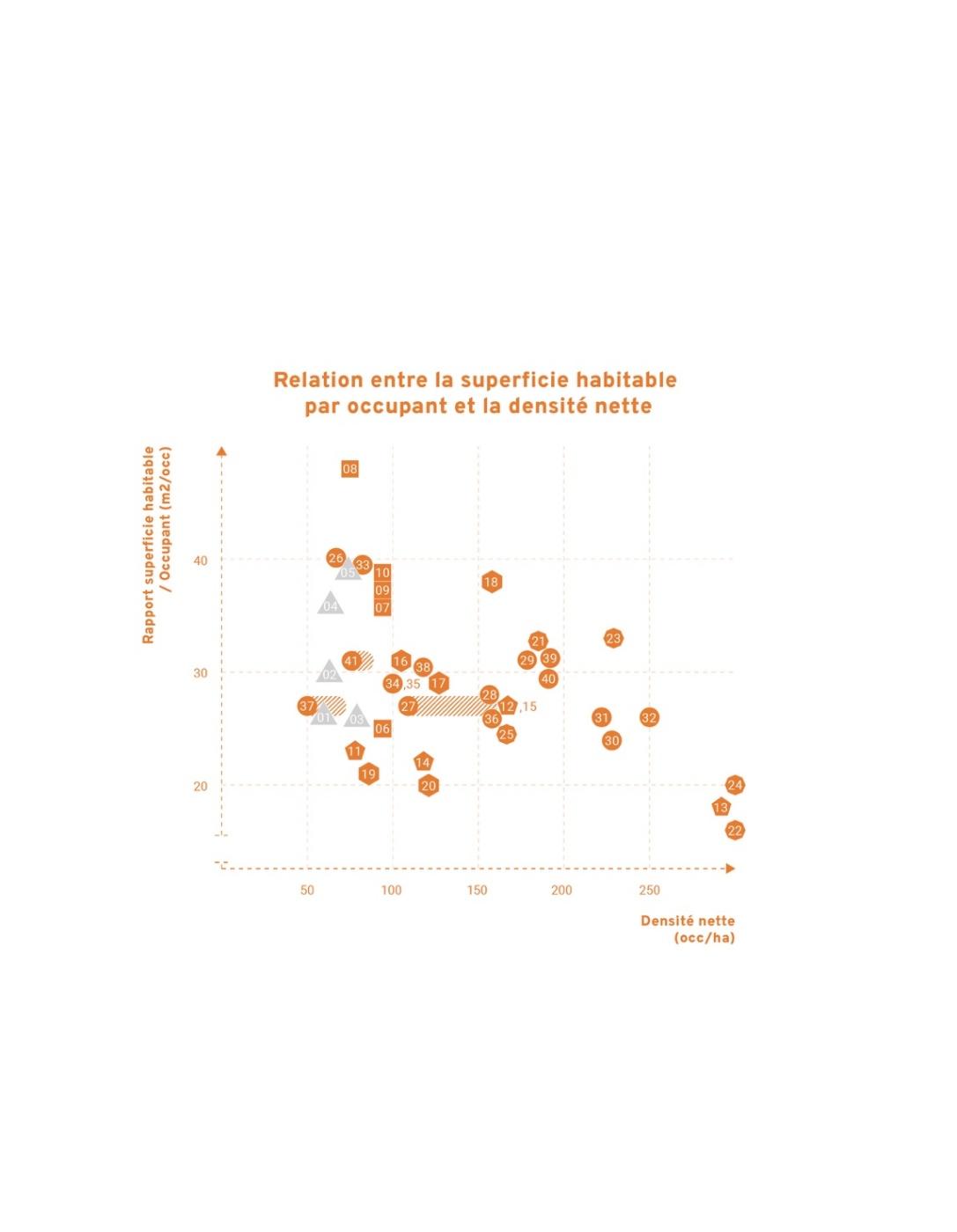

A wise layout may ensure sufficient distance between neighbours, smaller footprints, space for ac*vi*es and storage, as well as far-reaching and meaningful views Gentle densifica*on1 strategies such as auxiliary dwelling units (*ny homes, backyard co\ages, or converted garages) or incremental designs (adapta*on or addi*on over *me) offer more flexibility for members of the extended family to grow or age together (Habiter le Nord québécois 2024). In this regard, urban life needs diversity to thrive (Gehl 2012); visual diversity, diversity of uses (Bentley 2012) as much as a complete housing con*nuum or spectrum intertwined in compact and walkable neighborhoods.

Urban sprawl is costly for our society. Indeed, if more inhabitants live in a square kilometer, less land is required to house everyone. Thus, density generally shape compacity, reducing the amount of

1 "Gentle density housing" refers to a housing approach that increases residen:al density in a gradual and non-disrup:ve way. It aims to enhance urban environments by adding more homes or units without dras:cally altering the character of established neighborhoods. This approach focuses on integra:ng new housing in a way that respects exis:ng community aesthe:cs and maintains a balance between growth and livability (Gentle Density Housing Bylaw Guide. A Pathway for Local Governments, April 2024)

infrastructure or services required, lowering cost and increasing efficiency In the same way, densifying a village core could take full advantage of exis*ng gravel pads, on which most of the villages are built. At the architectural scale, an increased density almost always translates to a reduc*on of the amount of building envelope required to house a given number of dwellers, lowering construc*on costs as well as energy consump*on (Blais improve durability

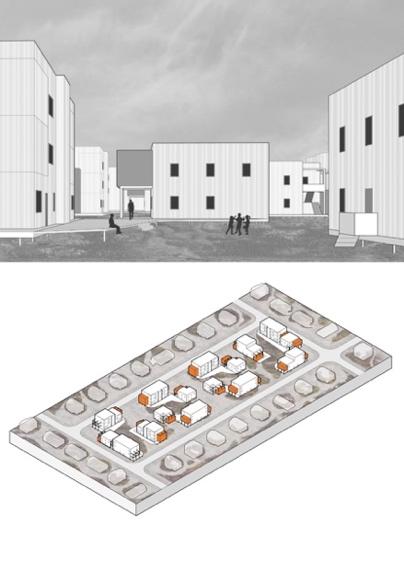

When it is has posi*ve outcomes. Contrary to popular belief, increasing the density doesn’t decrease the amount of space everyone has. previous study (Blais projects reviewed were selected for their quali*es (layout, community life, balance between quan*ty and richness of living spaces) and their poten*al to offer a genuine alterna*ve approach to living together in a meaningful way. N

1.2 Gentle d designed environments (Gehl 2012). terrain the building themselves, wrapping protec*vely in a welcoming and friendly way around one (Rosendahl 1970). Streets and open spaces are visually defined by buildings, genera*ng a sense of enclosure (Ewing and Clemente 2013). Depending on their size and spacing, a milieu can be sensed (figure 2). In other

words, the exterior urban space starts to feel like an outdoor room. In this regard, low-rise neighborhoods with large setbacks do not contribute much to defining an enclosed urban space.

The current sprawl of villages pushes the inhabitants to rely on cars and other motor vehicles to move around. The amount of space required to operate vehicles pushes the boundaries of villages even further, in return increasing the dependence on motor veh people brings people (Gehl On the other hand, density increases the number of des*na*ons within a given radius. As a posi*ve result, travel distances are more likely to be shortened, increasing the likelihood of walking instead of driving.

Well-thought density is meant to be experienced at 5km/h, leading to much more perceptual and func*onal variety along a journey (Gehl 2012). With shorter trips and welcoming urban spaces, som mobility becomes more appealing; streets and open spaces could be planned accordingly. While winter challenges som mobility in Nordic climates, designing a safe network that considers neither only pedestrians nor cars, but a wide array of transporta*on means could make som mobility much more

Figure 3. Land-Based Learning to Plan Meaningful Mee:ng Places by V. Alalam and A. C.-Gascon (www.doingthingsdifferently.ca).

appealing (Chapman 2025). Winter could be an opportunity to nurture means of transporta*on specific to this season such as cross-country ski, fat bikes or snowmobile

While new founda*on techniques using piles are enabling development on well-located bedrock sites, a significant por*on of village cores are built on gravel pads causing the kind of inconvenience that Inuit know so well. Climate change, gravel shortages and local empowerment enable new approaches focused on Inuit stewardship of the land – restoring ecosystems and landscapes within the village through revegeta*on

Vegeta*on has a posi*ve impact on permafrost preserva*on by intercep*ng warm rainfall, reducing surface water runoff, and regula*ng heat exchange with the ground. These effects contribute to more stable ground temperatures and a consistently shallower thaw depth throughout the year. (Brown 1963) Moreover, a long-term study on gravel pad reclama*on in Alaska (Peterson 2001) emphasizes the posi*ve impact of revegeta*on on ecosystem health and landscape aesthe*c – including the successful return of caribou to restored areas.

Although extreme cold and strong winds can threaten growing planta*ons, the use of snow fences helps reduce wind hazards. This allows a thin layer of snow to accumulate over the planta*ons, providing insula*on and protec*on from harsh temperatures. Addi*onally, the short growing season can be mi*gated by enriching the soil with fer*lizers. However, na*ve species have a slow-growth curve. Nonna*ve species may be introduced to fast-track the process, but its growth must be controlled to avoid the development of a monoculture. A low-tech alterna*ve to planta*on would be to harvest the na*ve tundra for transplanta*on (Hnatowich 2023) from a site already planned for development (figure 5).

as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik

Figure 4. Planning and Preserving the Land along the Innuksuak River by M. Avarello, M. Garneau-Charbonneau, G. Larouche and E. Renaud-Roy (www.doingthingsdifferently.ca).

Beyond offering employment opportuni*es and fostering region-specific skills, this prac*ce could also be established as a standard requirement for all new developments outside the villages’ cores – contribu*ng simultaneously to the revitaliza*on of their natural characters.

1.3 Form-based coding

While these strategies highlight the importance of adap*ng prac*ces to the northern environment, regulatory tools such as form-based codes offer complementary means to guide development in a way that respects both local context and community needs. Form-based coding cons*tutes a mean of regula*ng village development to reach a specific village form. It focuses on building forms, their rela*onships to one another, and their connec*on to the public realm, such as streets, courtyards, parking lots or the Land. Uses are considered although they are not the main concern (Plane*zen 2020). For reference, conven*onal zoning draws the boundaries of monofunc*onal zones (Levée 2019), forcing a set of homogeneous constraints on a territory that is anything but uniform (figure 6).

Conven<onal Zoning

Zoning Design Guidelines

Form-Based Codes

Figure 6 From zoning to form-based coding (www.formbasedcodes.org/defini:on) by Form-based Codes Ins:tute (2024).

Form-based coding, on the other hand, subdivides the territory according to a grada*on of landscape areas from the more urbanized to the more natural (Plane*zen 2020). These areas are formed by observing common architectural or landscape characteris*cs (Groupe BC2 2017) that gives a place its character (figure 7). Therefore, a single landscape area can be found in more than one geographical loca*on in the city. Such a subdivision makes urban form planifica*on much more foreseeable, specific

and harmonious with the context. By focusing on form and rela*onship between Land, buildings and people, form-based coding could foster the desired quali*es (Plane*zen 2020).

For example, the city of Bromont has adopted form-based coding into its by-law (L’Atelier Urbain 2017), dividing the territory into 20 areas defined by shared landscape or architectural traits. Tradi*onal zoning tools were simplified and adapted to support flexible, context-specific criteria outlined in the Plan d'implanta=on et d'intégra=on architecturale (PIIA), which guides project evalua*on based on quali*es like design, energy efficiency, and durability. According to the Form-Based Codes Ins*tute, in addi*on to all the defini*ons of terms, a form-based code generally contains four elements:

• Regula*ng plan indica*ng the sectors and areas where the various standards apply.

• Public standards specifying elements in the public realm such as sidewalks, vegeta*on, parking.

• Building standards including configura*ons, func*ons of buildings and more.

• Administra*on process with clear project applica*on and reviewing procedures.

To plan desirable and sustainable Inuit villages, local regula*ons have to be reconsidered beyond generic zoning models and adopt approaches grounded in the cultural prac*ces of its inhabitants (figure 8). By integra*ng form-based codes, thoughoul density, and Nuna stewardship, Inuit communi*es could plan for a meaningful, resilient, and inclusive living environments (figure 9).

Figure 8. Illustra:on of landscape areas for form-based coding by M. Vaillancourt-Cosse`e (2024).

9. Feasibility study for promising projects planned at the block scale (www.illu-nunavik.org) by Blais et al. (2024).

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik Tool 4: Regula:ons in context © Habiter le Nord québécois 2025 • habiterlenordquebecois.org

Figure 8.3. Village outskirts, project by A. Dion.

Figure

2. Legal framework to develop northern construc1on exper1se

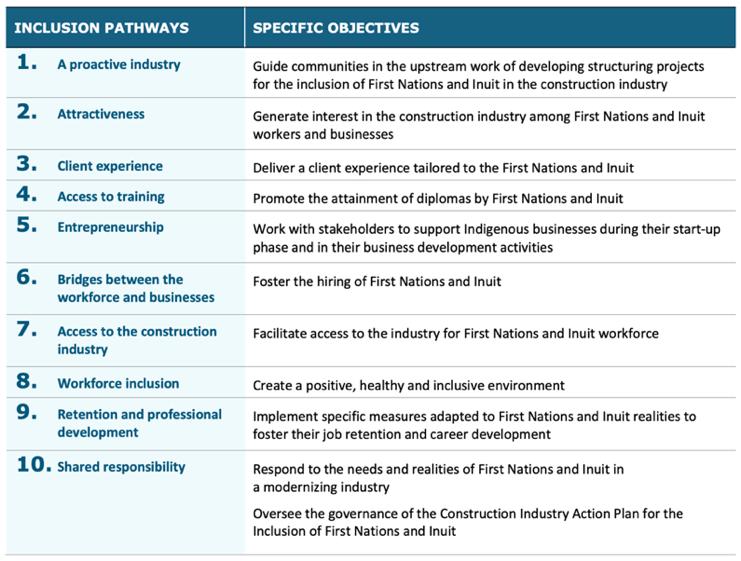

In Nunavik, adap*ng current regula*ons – such as adjus*ng learning programs prerequisites, tailoring voca*onal content to northern reali*es, offering flexible journeyman assessments in Inuk*tut, and simplifying administra*ve processes – can open meaningful pathways for Inuit youth to enter the construc*on trades. Part of this leadership lies with the Commission de la construc=on du Québec (CCQ), the organiza*on responsible for applying the Act on Labour Rela=ons, Voca=onal Training, and Workforce Management in the Construc=on Industry (Act R-20), which provides a legal framework for this industry. The CCQ offers services such as social benefits, pension and insurance, training and qualifica*on, labor management and applica*on of collec*ve agreements. For the past few years, the CCQ has been working on several projects to improve the engagement of Indigenous na*ons in construc*on.

In 2017, under the Construc=on Industry

Decree, Nunavik has been iden*fied as dis*nct region, ensuring a specific labor pool and providing resources dedicated to this territory.

And since 2024, the Construc=on Industry Ac=on Plan for the Inclusion of First Na=ons and Inuit2 presents inclusions pathways and objec*ves developed in collabora*on with Indigenous stakeholders (figure 9)3

2.1 Recogni6on of northern competencies and alterna6ve learning paths

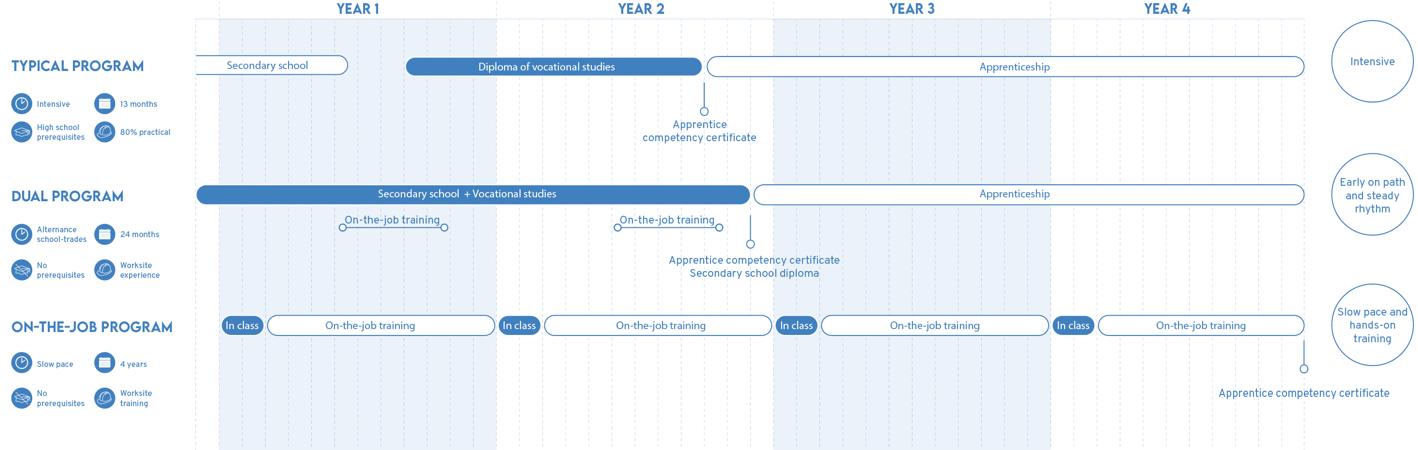

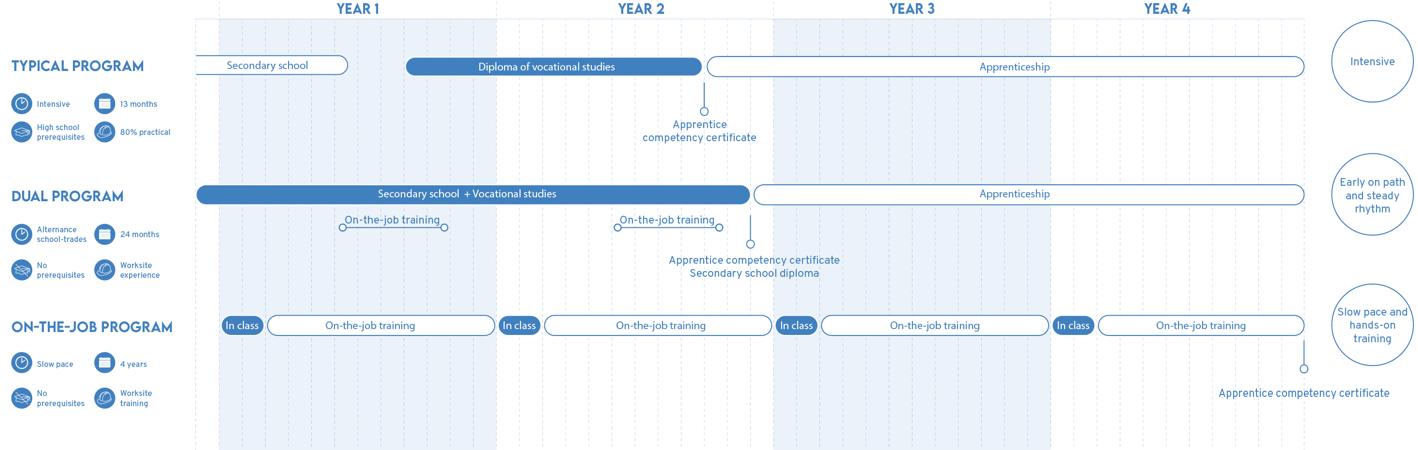

Construc*on is a most important employment opportunity in Nunavik. Qualifica*on of a local workforce is a challenge to which the industry should adapt. At the present, there are three ways to become a journeyman in construc*on trades (Commission de la construc*on du Québec 2024b) (figure 10):

2 Through this measure the CCQ sets an overall goal of having First Na:ons and Inuit represent 1% of the total workforce by 2034, as it they currently represent 0,38%, while accoun:ng for 1,4% of Quebec’s total popula:on (Commission de la construc:on du Québec 2024a).

3 As an example, the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke via their Labor Office have signed a complementary agreement defining with the CCQ a collabora:ve framework in their territory (Gouvernement du Québec 2020). This agreement allows the applica:on of a dis:nct regime, authorizing a local ins:tu:on to act for implementa:on and administra:on of labor standards, workers compensa:ons, safety and much more. This context could be translated into prac:cal strategies for workforce development in Nunavik, based on northern exper:se and aspira:ons for meaningful careers in construc:on. To support Inuit youth, flexible and culturally adapted models are needed to ensure long-term engagement and success.

Figure 9. Construc:on Industry Ac:on Plan for the Inclusion of First Na:ons and Inuit by Commission de la construc:on du Québec (2024a)

• Labor pools (star*ng with minimal qualifica*ons).

• Professional training program (available in Inukjuak and South)

• Appren*ce cer*fica*on (process for recogni*on of competency through experience).

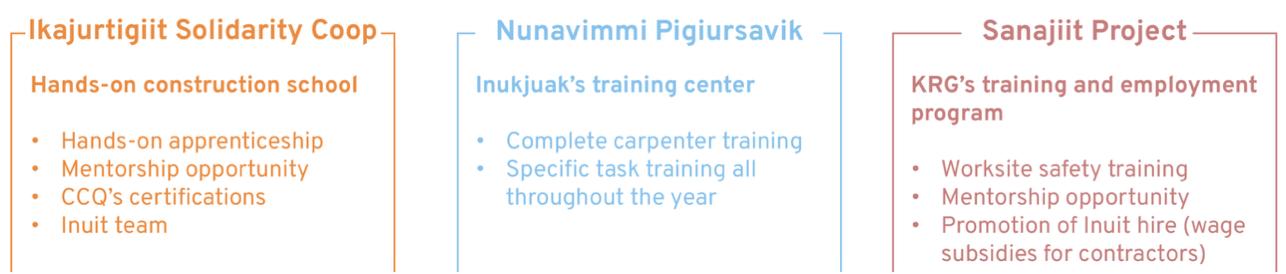

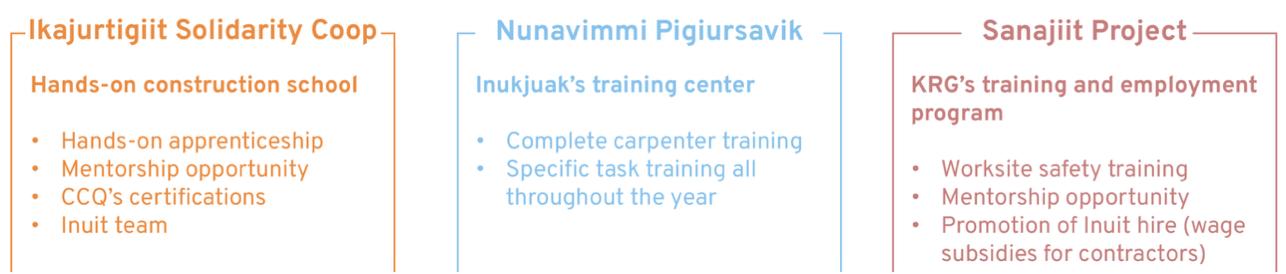

While these paths present many challenges, various local ini*a*ves open new opportuni*es by sepng bold, measurable goals and encouraging lomy aspira*ons (figure 11). They focus primarily on the youth popula*on by adap*ng pedagogy (schedules, meaningful work rooted in young people's reali*es), inves*ng in more mentor-student *me, tailoring the scale of (specialized) schools, and integra*ng social services into gradua*on efforts to support students, teachers and administrators.

The Ikajur*giit Solidarity Coop exemplifies how open labor pools can empower youth in a meaningful way by providing on-site training and personalized mentorship, while also facilita*ng the recogni*on of work hours. This learning journey aligns with Inuit ways of being, knowing, and doing, offering opportuni*es to build careers and contribute to the coopera*ve movement – whose roots are well anchored in Nunavik. It paves the way for individuals to con*nue as journeymen and, in turn, support the training of the next genera*on of Inuit appren*ces in their own language and cultural context.

An alterna*ve to the typical carpentry program currently offered by Nunavimmi Pigiursavik – and by most voca*onal training centers across Quebec – can be found elsewhere in Canada. Two notable adapta*ons stood out for their innova*ve approaches to scheduling and learning formats (figure 12):

• A dual program (formule duplex) offered by the Centre de services scolaire de la Beauce-Etchemin (2025) provides an alterna*ve pathway without prior academic prerequisites. In this model, carpentry training begins early and is integrated with the high school curriculum. Over the course of two years, students may simultaneously complete their high school diploma and earn a carpentry cer*fica*on.

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik

Figure 10. Typical paths for carpentry training in Nunavik, Québec by V. Morrier (202 ).

Figure 11. Training opportuni:es by/for Inuit of Nunavik by C. A. Gauthier (2023).

• An on-the-job program, developed by Alberta’s Appren*ceship and Industry Training (2025), offers a four-year cycle combining classroom instruc*on with paid and supervised work experience. Each year includes eight weeks of in-class learning followed by hands-on training at a worksite. Admission requirements are rela*vely flexible, allowing mul*ple entry points such as the recogni*on of specific high school courses or the comple*on of an entrance exam. A sponsorship agreement is required for the on-the-job component. Notably, students who have not yet met all academic prerequisites may s*ll register and begin accumula*ng work hours, provided they fulfill the requirements once the program begun.

Using the typical carpentry program as an example, adap*ng qualifica*ons to the northern context involves revising both curriculum and assessment to replace standard competencies with those that highlight local reali*es. These could include building founda*ons on permafrost, adop*ng frugal construc*on methods, and reviving tradi*onal assembly prac*ces – all while fostering greater awareness of climate change impacts on buildings. Such adapta*ons would recognize a worker’s ability to perform skilled tasks but also to pass on those skills in Inuk*tut. Training programs would reflect both prac*cal and pedagogical competencies. Building on such models and regional adapta*ons, strategies for flexible scheduling can further support Inuit par*cipa*on and success in the construc*on trades.

2.2 Adapta6on of construc6on schedule and prac6ces by Inuit workforce

Given that Inuit livelihoods are deeply connected to hunting and fishing, legal framework for a sustainable construction industry should be structured around these regional realities. For 8 out of 10 Nunavimmiut, food security and sovereignty remain closely tied to land-based activities that can vary significantly from one community to another (NRBHSS 2017) Year-round or seasonal employment models can be envisioned to accommodate the needs of communities – particularly in smaller villages

Establishing a flexible schedule is a key factor for a successful implementa*on of construc*on projects. By aligning schedules with both the seasonal requirements of sound construc*on prac*ces and rhythms of subsistence ac*vi*es, the industry can empower Inuit workers and their families. The same considera*on applies to training schedules. A coordinated calendar could be tailored to the specific exper*se and harvest seasons of each community (figure 13). These considera*ons may evolve as construc*on prac*ces offer greater flexibility. For example, a scenario based on the standard construc*on calendar that incorporates pile founda*ons reveals a few opportuni*es.

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik Tool 4: Regula:ons in context

Figure 12. Local ini;a;ves by/for Inuit of Nunavik by C. A. Gauthier (2024)

Figure 13. Timeline scenario illustra:ng the rela:onship between subsistence seasons, construc:on planning and training ac:vi:es4 by Habiter le Nord québécois (2024).

4 Schedules for medium-sized residen:al projects ($6M) according to Maxime Heroux (architect). Dates vary according to village and weather condi:ons. All dates are approximate.

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik Tool 4: Regula:ons in context © Habiter le Nord québécois 2025

infrastructure development (roads, culverts or drainage) as well as to builders by managing leeway to tackle unforeseen events, advance construc*on phases or align with seasonal ac*vi*es.

Construc*on choices, such as pile founda*on, could support local capacity building for a broader spectrum of exper*se like re-naturaliza*on or soil decontamina*on, as noted earlier. This specialized exper*se can be shared across the Circumpolar regions, offering economic opportuni*es driven by policies, codes, or regula*ons shaped by local needs.

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik Tool 4: Regula:ons in context

Habiter le Nord québécois

Adap*ng the regulatory framework to reflect the cultural visions and aspira*ons of Nunavik presents a significant opportunity in sustainable northern development (figure 14). Regulatory bodies may open new pathways to support the knowledge transmission and long-term engagement in the construc*on sector. These adapta*ons not only strengthen community resilience but also posi*on Nunavik as a leader in Inuit self-determina*on

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik

Regula:ons in context

Figure 14. Four pillars of the Nunavik Climate Change Adapta<on Strategy by Makivvik (2024).

References

Abdon Peterson, D. (2001) Long Term Gravel Pad Reclama*on on Alaska’s North Slope. Restora=on and Reclama=on Review, 7(2). conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/728d6694-22724d87-8b77-505787f1c051/content

Bentley, I. et al. (2012) Responsive Environments. Taylor and Francis.

Blais, M., Vachon, G., Boudreault, S. (2024) Variété, acceptabilité, faisabilité : opportunités de concep=on et de réalisa=on de milieux de vie qui correspondent aux ressources et aux aspira=ons des communautés du Nord québécois. Rapport de recherche final pour le Gouvernement du Québec (SHQ-MAMH-SPN), École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, Québec, (211p). illu-nunavik.org

Brown, R. J. E. (1963) Influence of vegeta=on on permafrost. Proceedings; Conseil Na*onal de Recherches. publica*ons-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/td/?id=4c989143-5d15-4404-9363db1742108798

Centre de services scolaire de la Beauce-Etchemin (2025) Charpenterie-menuiserie DEP 5319 cssbe.gouv.qc.ca/forma*on-des-adultes-forma*on-professionnelle/forma*on-professionnelle/lesprogrammes/charpen*ere-menuisiere-charpen*er-menuisier

Chapman, D. et al. (2025) Planning and urban design for aWrac=ve Arc=c ci=es. Routledge. Commission de la construc*on du Québec (2024a) Construc=on Industry Ac=on Plan for the Inclusion of First Na=ons and Inuit 2024-2034. ccq.org//media/Project/Ccq/Ccq%20Website/PDF/AffairesAutochtones/plan-ac*on-PACPNI-2024_EN Commission de la construc*on du Québec (2024b) Qualifica=on and Access to the Industry: Recogni=on of Training and Work. ccq.org/en/qualifica*on-acces-industrie/reconnaissance-forma*onexperience

École des mé*ers et occupa*ons de l’industrie de la construc*on de Québec (2025) Forma=on de charpenterie-menuiserie. emoicq.cssc.gouv.qc.ca/programme/forma*on-charpenterie-menuiserie Ewing, R., Clemente, O. (2013) Introduc*on1. Dans R. Ewing, O. Clemente, K. M. Neckerman, M. PurcielHill, J. W. Quinn, & A. Rundle, Measuring Urban Design (p. 1-23). Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-209-9_1

Form-Based Codes Defined (n. d.) Form-Based Codes Ins=tute at Smart Growth America. formbasedcodes.org/defini*on

Gehl, J. (2012) Pour des villes à échelle humaine (N. Calvé, Trad.). Les Éd. Écosociété DG diff.

Gouvernement du Québec, Kahnawà:ke Labor Office and Commission de la Construc*on du Québec (2020) Complementary agreement defining the collabora=on between la Commission de la Construc=on du Québec and the Kahnawà:ke Labor Office regarding the construc=on industry in the territory between the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke travail.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/fichiers/Documents/lois_et_reglements/Ententes/EntenteCollabora*o n_Kahnawake-Construc*on-en.pdf

Groupe BC2 & Ville de Bromont (2017) Plan d’urbanisme 2015-2030 bromont.net/wpcontent/uploads/2018/05/PU_basse-r%C3%A9solu*on.pdf

Habiter le Nord québécois (2024) Desirable Density [Keys for Change] in Doing Things Differently: Atlas of Ideas to Plan, Dwell, Build a Sustainable Nunavik, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, Québec doingthingsdifferently.ca/keys-plan/desirable-density Hnatowich, I. G., Lamb, E. G., & Stewart, K. J. (2023) Reintroducing Vascular and Non-Vascular Plants to Disturbed Arc*c Sites: Inves*ga*ng Turfs and Turf Fragments. Ecological Restora=on, 41(1), 3-15. doi.org/10.3368/er.41.1.3

L’Atelier Urbain. (2017) Le form-based code : Vers une évolu=on des règlements d’urbanisme au Québec. ocpm.qc.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/P%20101/7.10.6_guide_~c.pdf

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik

Levée, V. (2019) Planifier la forme urbaine, non les usages. Ordre des architectes du Québec, 30(3). oaq.com/ar*cle-magazine/planifier-la-forme-urbaine-non-les-usages

Makivvik (2024) Nunavik Climate Change: Adapta=on Strategy. makivvik.ca/nunavik-climate-changeadap=on-strategy/#1

McDonald, M.P., Snowball, H. (2019) The Fragile Resilience of the North. Landscapes + Paysages, Spring 21 (1): 50-52. csla-aapc.ca/sites/csla-aapc.ca/files/LP%2B%20Spring%202019.pdf

NRBHSS – Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services (2017) Qanuilirpitaa? Health Survey: Food Security. nrbhss.ca/sites/default/files/health_surveys/Food_Security_infographics_en.pdf Plane*zen (2020) What is a Form-Based Code? [Video recording]. youtube.com/watch?v=644gz7maHdM

Potvin, S. (2018) Plan et règlements d’urbanisme de la Ville de Bromont [Répertoire des bonnes pra*ques en urbanisme]. repertoireouq.com/projet/plan-et-reglements-durbanisme-de-la-ville-de-bromont

Rosendahl, G. P. (1970) The technical Development. Dans K. Hertling & E. Hesselbjerg (Éds.), Greenland: Past and Present. Trade Secrets Alberta (2025) Appren=ceship and Industry Training in Alberta. tradesecrets.alberta.ca/trades-in-alberta/profiles/002/

Home as territory: A blueprint for community-driven housing produc:on in Nunavik