Living in Northern Quebec

The ABCs of an Authentic Collaboration

Principles and Actions of Architecture and Planning Projects on Indigenous Land

By : Geneviève Vachon, Élisa Gouin, Samuel

Boudreault, Florence Gagnon avec Myriam Blais, Lyna Chambaz and Anthony Présumé

Our thanks to Hugo Lavallée, Annie Beaudoin, Vickie Lefebvre, Norman Matchewan, and our student designers.

Translation: Claire Kingston

English edition: Justine Morin

©2024 Habiter le Nord québécois École d’architecture de l’Université Laval

Québec (QC) Canada G1R 3V6

This guide is part of Contract No. R855.2 with the ministère des Transports et de la mobilité durable du Québec, in collaboration with the Algonquin community of Barriere Lake (ABL –Rapid Lake First Nation reserve).

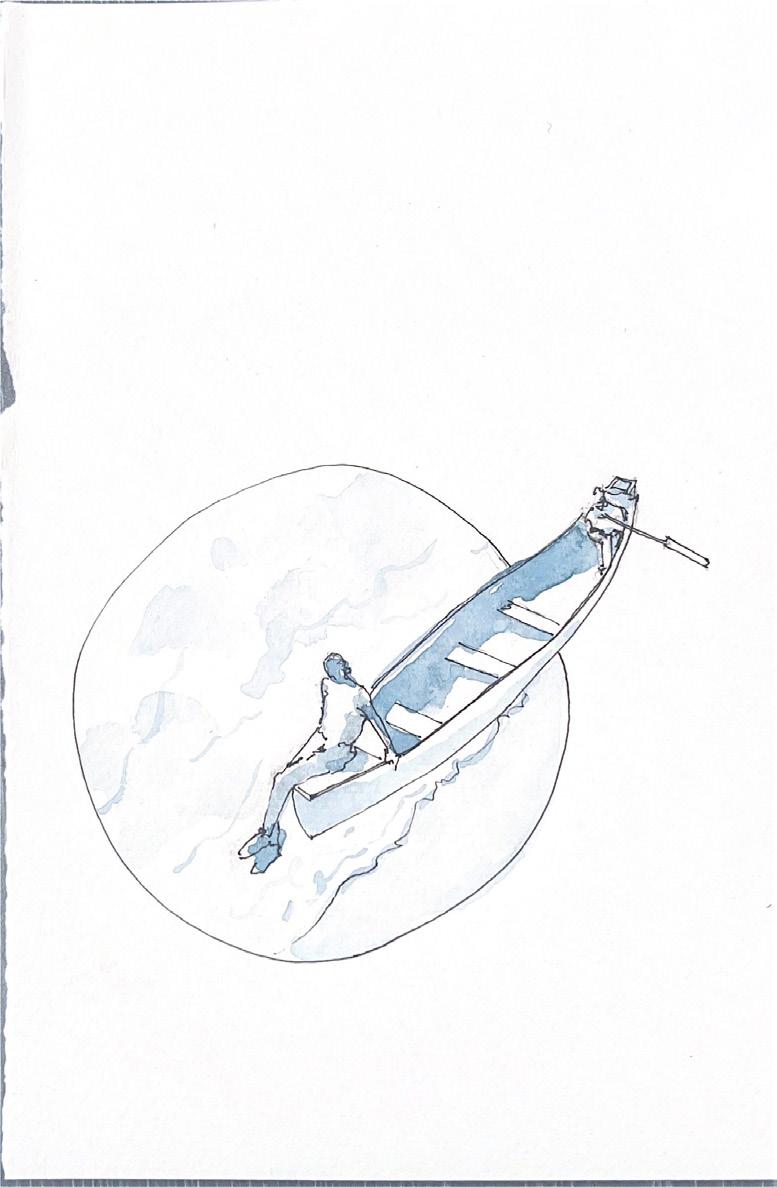

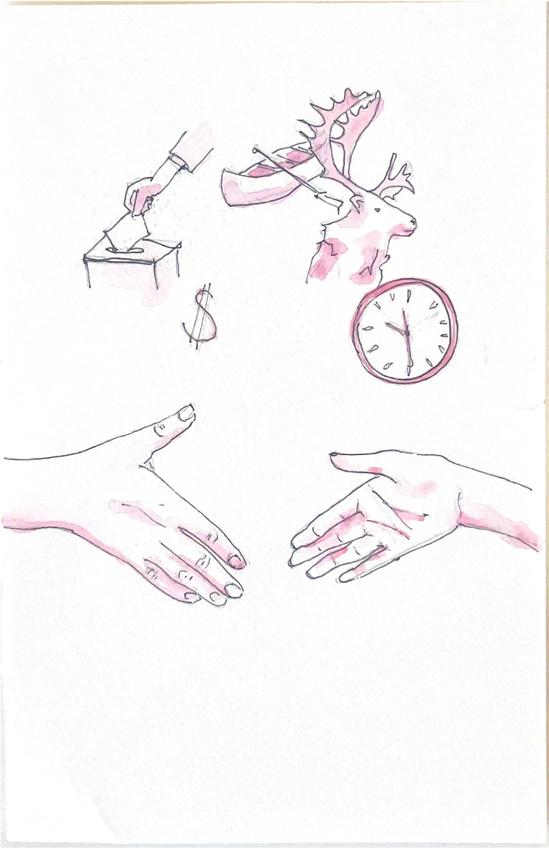

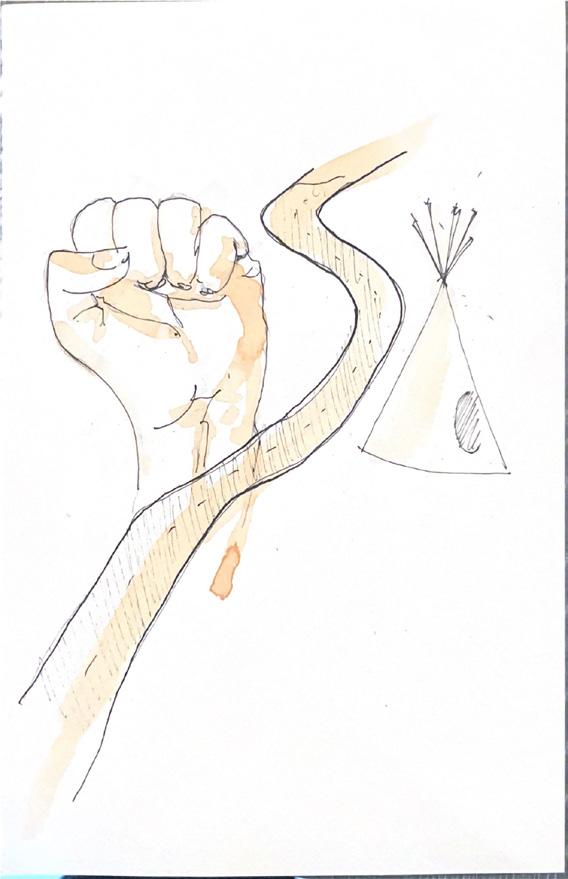

Watercolours (2023) Anthony Présumé

Aerial photos (2023) Pierre Lahoud

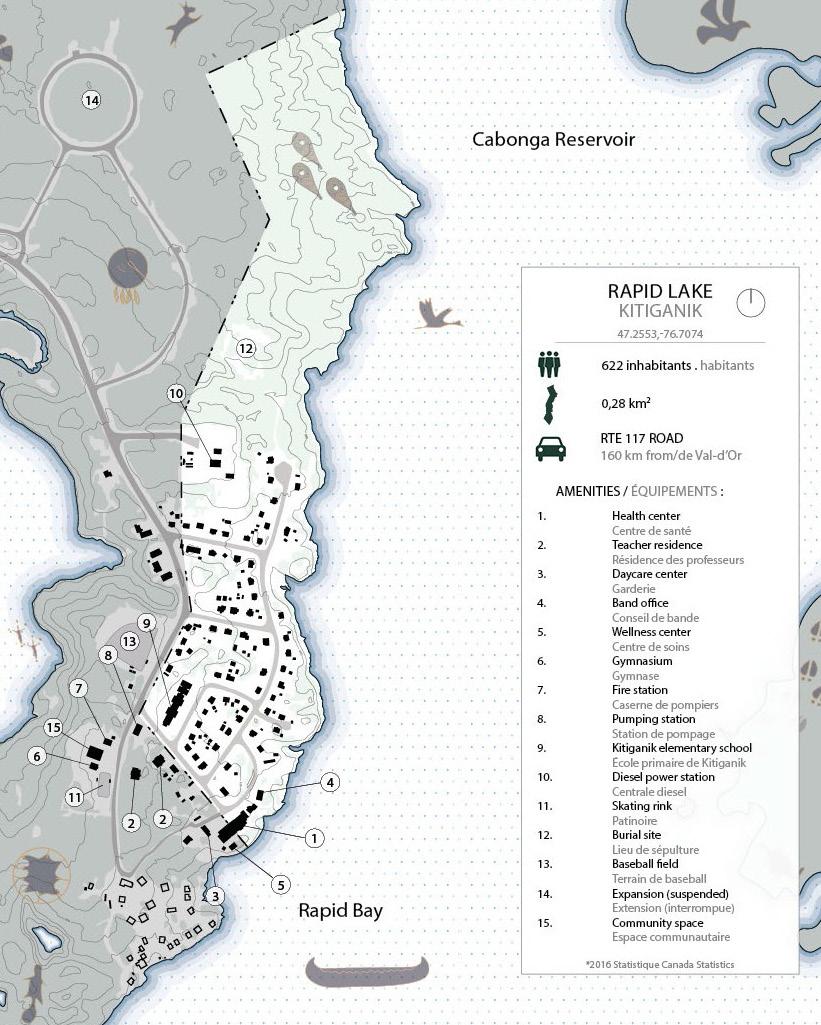

* Mitchikanibikok Inik: Algonquins of Barriere Lake in the Algonquin language, ‘which means “people of the stone dam”, because of the small rock barrier erected to catch fish on the edge of the Cabonga reservoir’. (Pasternak 2017, 85).

Kitiganik: Rapid Lake reserve, where most of the Barriere Lake Algonquin live.

Introduction

Intentions and challenges

This illustrated guide summarizes the results of a collaborative research project funded by the Ministère des Transports et de la Mobilité durable du Québec (MTMD) involving researchers from Université Laval’s School of Architecture and representatives of the Algonquin Anishinaabe community of Barriere Lake (ABL)*

The goals were:

• To lay the groundwork or “ABCs” for an authentic collaboration with First Nations representatives through activities in a context of active partnership; and

• To propose culturally appropriate principles and actions to guide the discussion on possible architecture and planning projects on Indigenous land using Anishinaabe experience.

We first proposed a new collaboration with the ABL community to discuss visions for sustainable architectural development that would potentially include the construction and co-management of a service area located close to the reserve on Route 117. We then sought to better understand the realities and aspirations of the ABL community through collaborative brainstorming exercises to help generate design and development ideas.

From these co-creation activities emerged architecture and planning principles that were adapted to the Indigenous worldview to enlighten discussion between the MTMD and the ABL as well as with other Indigenous communities.

The purpose of this guide is to inform public sector representatives ahead of a collaborative endeavour involving Indigenous communities. Resulting from the representative experience of partnerships between consultants (in this case, from universities) and representatives of an Indigenous community, the guide also seeks to inform decisions regarding the design and development of public-funded projects that are of the highest architectural quality, cultural relevance, and social utility for both the Indigenous communities involved and Québec. Most importantly, it represents an approach that follows the path of reconciliation with First Nations, whose desire is to actively participate in the sustainable and self-determining development of their living environment and land.

Approach

The collaborative research approach is based on the concept of active partnership that brings together the interests and knowledge of its participants (universities, communities, and professional groups) involved in the process. It also engages research-creation in architecture to develop concrete proposals (or pro-

jects) based on an iterative process of design, synthesis, and validation to guide discussions. Research-creation is a research approach that combines creative practices and university research, generates knowledge, and promotes innovation through artistic expression, scientific analysis, and experimentation (Williams-Jones, Lapointe, & Gauthier, 2018). It contributes to the production of new esthetic, theoretical, methodological, epistemological, or technical knowledge (Paquin & Noury 2018) by imagining and proposing appropriate architectural solutions to address the needs and concerns of the communities. Design workshops at Université Laval’s School of Architecture use this approach in collaboration-creation laboratories to put this knowledge to work through actions directed toward solving actual issues related to housing, infrastructures, or other needs expressed by the participating community (Belleau et al., 2011).

The guide has two sections.

The first one presents winning conditions (ABCs) for successful collaboration with First Nation communities;

The second one identifies culturally appropriate principles for architecture and planning projects that best serve Indigenous communities, their interests and their values, with actions illustrated by precedents and design initiatives of the School of Architecture at Université Laval, in collaboration with the ABL community of Kitiganik (Rapid Lake reserve).

Toward authentic collaboration

Many studies propose “toolkits” to guide collaborations with and for Indigenous communities (IPCA, n.d.; Gentelet et al., 2018). The present guide goes further with a research-creation approach in architecture and planning initiatives. All these experiences are examined through active reflexivity, in which designers analyze their own practices and make adjustments in a continuous collaborative process (Schön, 1984). Reflexivity also requires intersubjectivity, with the understanding that the knowledge and visions of Indigenous peoples are just as important as scientific or professional knowledge (Després et al., 2004). Emerging from this active learning process are the following recommendations to inform and enlighten the establishment of authentic collaborations with Indigenous communities.

‘Do your homework !‘

Laying a strong foundation by establishing trusting relationships with the people, organizations, and communities with whom you wish to collaborate is essential to the success of your project. When relationships are built from the ground up in a spirit of reconciliation, they can flourish and grow into fruitful partnerships and projects!

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas –IPCA (s.d.)

Understanding the realities and cultural context of First Nations requires continuous effort—which is not their responsibility! Even if Indigenous communities are diverse, each one defining themselves according to their own history and truths, non-Indigenous parties have a duty to learn more about these particularities to better understand the origin of biases that may influence the dialogue. Indeed, systemic issues that have determined the current living conditions of Indigenous peoples call for greater consideration when developing an authentic collaboration and sincere reconciliation. The communities state loud and clear: Do your homework! (IPCA, n.d.).

tained efforts to give political power back to First Peoples and to support, among others, a regeneration (or resurgence) of the use of Indigenous languages, oral cultures, traditions, and traditional systems of governance (Simpson, 2014). Each action undertaken with First Nations strives to achieve this goal in an inclusive and just space, where recognition of ancestral rights is an integral part of any partnerships in which they are involved.

Reconciliation is building a greater awareness of the histories of First Nations and their relationship with Canada. It is also rooted in sus-

Indigenous peoples are not only collaborators but also knowledge keepers and decision makers. The development of collaborations between non-Indigenous professionals and Indigenous communities enables both parties to exchange—and even co-produce—knowledge in a mutual learning processus (Sanderson & Kindon, 2004) that helps widen their respective worldviews. Two-eyed seeing refers to the idea of learning to simultaneously appreciate Indigenous knowledge through one lens and Western knowledge through another (Bartlett, Marshall, & Marshall, 2012). This way of entering into a collaborative environment opens the door to dialogue between ways of thinking, being, and doing, while respecting the identity of each partner in this collaboration (Bussières, 2018; Caillouette & Soussi, 2017; Dumais, 2011; Gillet & Tremblay, 2017). This method leads to a place of mutual understanding—a partnership space—where diverse actions are deployed to improve existing conditions and avoid compromising future generations.

Prior to this balanced dialogue, “doing one’s homework” must take into account three major values that are shared among Indigenous nations: the sacred nature of the land, the importance of the connection to the latter, and the relevance of stories and storytelling to bear witness and to look forward.

1.1

Sacred Land

The land is a sensitive subject; you have to be careful. When you talk about the land with an Innu, it’s like talking to a mother about their child. It’s the same level of intensity. We still feel that the land holds deep significance, even for those who never go into the woods.

Gaëlle André-Lescop, an Innu engineer, quotes a participant in her research (2019, 70)

Across nations, traditional Indigenous ways of knowing are the direct result of the lived experience on the land, over generations. Far from static, these knowledge systems operate and adapt to the changing conditions of the land, including those imposed by climate change (Nursey Bray et al., 2022; Vachon et al., 2024, in press).

The land plays a key role in the planning decisions of each community (Matunga, 2013). Therefore, to develop a collaborative approach that respects this, it is imperative to understand the inherent aspects of the land (toponomy, markers, resources, animals) and the importance to communities (practices, knowledge, legends, spirituality) in their process of identity affirmation.

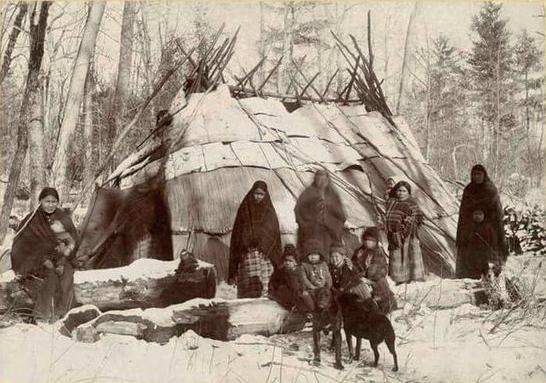

Indigenous peoples share a unique way of thinking and worldview that is profoundly connected to the land (Matunga, 2013). For ABL community member Norman Matchewan, Anishinaabe way of life is indissociable from the land (Barriere Lake Solidarity, 2011). Many families share their time between the community and the forest, where they hunt, fish, trap, pick berries, do crafts, and practice traditional medicine. In addition to ensuring subsistence, the land is where culture is learned and lived. Matchewan adds: “It’s our home. […] This is how our identity survives, as Mitchikinabikok Inik” (Pasternak, 2017).

1.2

Relationality

Rather than viewing ourselves as being in relationship with other people or things, we are the relationships that we hold and are part of.

Shawn Wilson, Cree researcher/scholar (2008, 80)

Relationality is a basic ontological concept in the Indigenous world. It pertains to the fundamental nature of the connection with and between individuals, the environment, the world, the departed, and the land. Ac-

cording to Shawn Wilson (2008), relationality translates to the meaning Indigenous peoples give to the environment and to the land in a reciprocal relationship. This reciprocity is grounded in the notion of the responsibility or the caretaking of resources according to a holistic or ecocentric worldview, in which the individual is in symbiosis with what surrounds them and is in inside of them. These connections are what ties a community to its land.

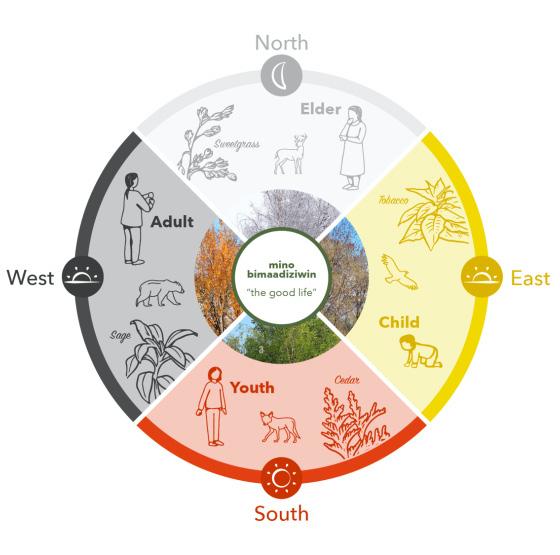

Indigenous ontology connected to the land (see Gouin, 2024)

Temporality is closely associated with relationality. The notion of time is constructed and perceived differently by Indigenous communities who understand and live their connections to the land according to the seasons (Gentelet, 2009). They are aware that the actions on today’s environment affect the future, as have the actions of the past. This is affirmed in the Seventh Generation principle: the knowledge and actions of the past show the way to those of the present and together, they build a vision of the future (Jojola, 2013). The relationships with time and the seasons, along with the astute observation of the ecosystems, are all part of a traditional knowledge system that continues to evolve. They also influence subsis-

tence practices and the transfer of knowledge (Hatfield et al., 2018). The recent imposed sedentarization of semi-nomadic peoples has changed their rapport with the seasons and their displacements. Despite this, connections to the land remain, in daily life as in the imaginary, even as contemporary practices are experienced through hybrid times that are not always easy to reconcile (André-Lescop, 2019).

Stories and storytelling

Storytelling, as a research method, helps to understand the many different voices heard during the planning process.

Catalina Ortiz (2022, 6)

In the collaborative planning process, storytelling recognizes and uses the subjective experiences of the persons involved. For example, to understand a context of intervention, this traditional approach invites professionals to think beyond the confines of objective or technical analysis and highlights Indigenous stories for a deeper comprehension of their way of life (Sandercock, 2003).

Intercultural communication is also a type of narrative, as it involves the community’s voices, stories, experiences, and ways of knowing, to which professionals contribute. Storytelling is above all a lively, open discussion that considers the two worldviews, similar to two-eyed

seeing. It echoes Indigenous oral traditions and vivid discourse to express their sense of belonging to the land. The heroes in a story can therefore take the form of inescapable forces, such as the legacy of colonization and connections to the land. In a context where cultural identity plays an important role, art, music, and poetry all contribute significantly to the story (Sandercock, 2003). Therefore, in addition to local participating citizens and decision makers, planning specialists could learn much from artists in collaborative processes that include storytelling.

The storytelling approach invites the protagonists - Natives and non-Natives, professionals and citizens - to find common threads among the stories to tell and guide the project. By enhancing the value of indigenous voices and imagination, storytelling can help to identify and even mitigate power imbalances within collaboration, and defuse preconceptions (Sioui and Marceau 2023). It can even reinforce buy-in to the resulting project, since the latter derives, as the collaborative work progresses, from the interpretation of the meaning given to places (Sandercock 2003). In short, storytelling offers an alternative way of thinking and working on a project, enabling stakeholders to imagine together a vision of the future rooted in experience.

Visit ‘Let’s have a yarn !’

An Illustrated narrative to reveal and imagine Kitiganik (2023) ) to better understand the potential of storytelling when used in urban design.

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/sto ries/b782a970cfb94ec88d7425f 82c0626b7

Winning Conditions for Authenticity

I’ve always been proud to collaborate, but above all, to get the people in my community involved. [...] I no longer look at our homes in the same way. I immerse myself in my culture thanks to these exchanges. Before [our projects with the architecture school], I didn’t feel obliged to express opinions [...]. [Now], I invite all my neighbors to do so. Participating in the thinking behind the development of our communities is essential to our well-being - to building a future that looks like us. Can you draw me a picture of what you’re talking about? I want to see it drawn. I want to understand. I came here to learn.

initially set in a history of at times stormy interrelations. Discussions also reveal opportunities for convergence through a bridge, enabling authentic and long-lasting collaboration (Gentelet, 2009; Gouin, 2021). This space is one of mutual trust, reminiscent of the Two Row Wampum Treaty between early settlers and First Nations (Viswanathan, 2019).

Carmen Rock, retired housing official, iTUM (HLNQ 2019, 13)

The partnership space also helps to better understand the role of the “gatekeepers” within the different member groups. Gatekeepers flow between the Indigenous and Western paradigms to channel mediation in this intercultural context. Clément et al. (1995) defined them as go-betweens, weaving collaborators together. Their role is key, as they not only facilitate the building of a relationship of trust but also generate opportunities to look beyond ontological, epistemological, and cultural limitations. These strategic individuals may belong to either group and generally already have strong established relationships with certain participants (professionals, long-standing friendships, etc.) prior to the project.

After “doing the homework”, creating a partnership space involving non-Indigenous professionals and Indigenous communities thus becomes a space for relationality, at the convergence between the interests and ways of knowing of each person involved in the process (Gouin, 2021). In the context of a collaboration with Indigenous people, worldviews and practice/research paradigms—often from opposing histories—come to meet. The partnership space is a space for dialogue that helps to define the members’ respective expectations and their preconceptions that are

Authentic partnership initiatives are thus an opportunity to combine different types of ways of knowing for the benefit of projects that transform living environments in an acceptable, achievable, and sustainable manner. The following section presents key actions for a successful research partnership (Gouin, 2024) and concrete recommendations.

The Keys to Authenticity

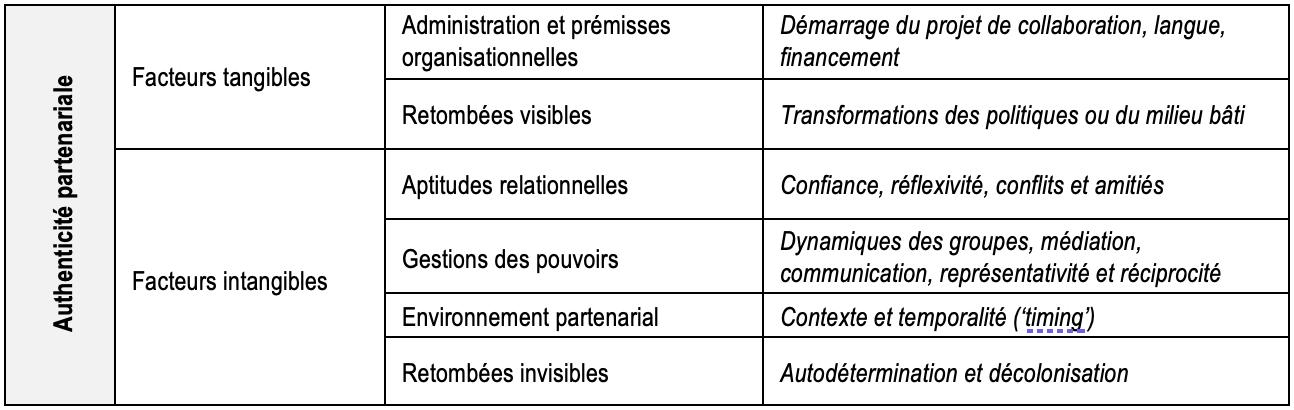

Partnership authenticity is characterized by the legitimacy and success of the collaborative research process. It uses tangible and intangible factors (summarized in Table 1) that

were validated by Innu, professional, and university representatives who participated in a research partnership (Gouin, 2024).

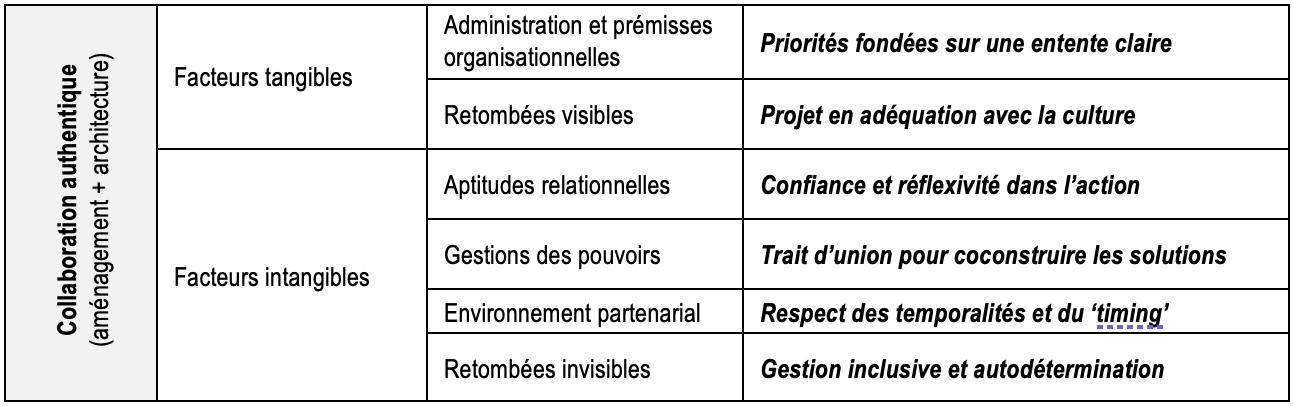

For planning and architectural practice (public or private), these factors lead to six recommendations for guiding or measuring the authenticity of a collaboration in partnership with an aboriginal community (Table 2).

Table 1: Tangible and intangible factors of a successful research partnership based on an exploratory review of literature conducted in 2020 (Gouin, 2024).

Tangible factors

Intangible factors

Administration and organisational foundations

Visible impact

Relational skills

Power management

Partnership environment

Invisible impact

Start-up of the collaboration project, language, financing

Transformation of policies or the built environment

Trust, reflexivity, conflicts and friendships

Group dynamics, mediation, communication, representation and reciprocity

Context and timing

Self-determination and decolonisation

Table 2: Based on the tangible and intangible success factors of partnership research: Six recommendations for an authentic collaboration in architecture and planning.

Tangible factors

Administration and organisational foundations

Visible impact

Relational skills

Intangible factors

Power management

Partnership environment

Invisible impact

Priorities based on a clear understanding

Project in line with culture

Trust and reflexivity in action

A link for co-constructing solutions

Respect for deadlines and timing

Inclusive management and self-determination

Recommendations for Authentic Collaboration

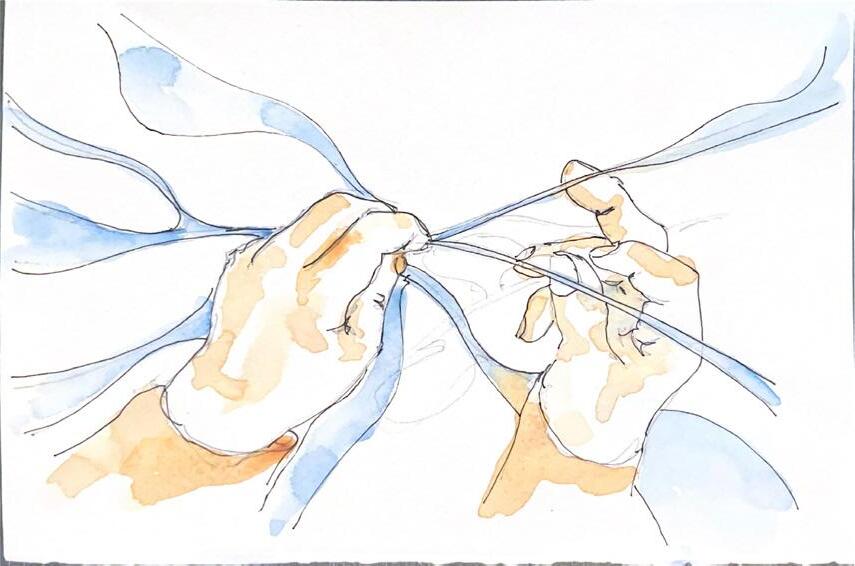

The wampum, symbolizing the agreement between two parties, notably serves to define roles and responsibilities. Drawing: A. Présumé, 2023.

• Priorities based on a clear agreement

Regardless of the type of funding used, creating and building an authentic collaboration emerges from the expectations of each partner, and above all, the priorities identified by the Indigenous community involved. Clear expectations and priorities facilitate the elaboration of an agreement/contract that clearly identifies—like a wampum—the roles, responsibilities, and implications of each participant from start to finish. This agreement is established well before project planning or design begins. It identifies and objectively considers any and all possible issues arising between the two participating groups and proposes ways to address or avoid them. The agreement is articulated in a brief, illustrated reference document that each participant, including local citizens, will find easy to read and understand. A translation of the agreement’s key elements is an added measure of cultural consideration to help prevent misunderstandings and voice expectations, with the resulting conceptual back-and-forth serving for validation and support.

• Compatibility with the culture

Section 2 of this guide identifies principles and proposes actions to design and achieve this project.

• Trust and reflexivity in action

Trust between the partners in an authentic collaboration is built by investing time and multiplying the opportunities for dialogue and sharing, notably through the practice of storytelling. In fact, the feelings of trust of Indigenous people toward professionals have a better chance of solidifying if the following conditions are present: in-person meetings in the community (rather than remote), active listening, recognition of the stories and shared ways of knowing, and a stable team of professionals who are committed to the endeavour (including discussions in a significant social context, such as during a meal or on-site traditional activities).

The ability to reflect of architecture or planning professionals enables them to continuously adjust their relational skills in the

various actions undertaken. Co-designing engages this reflexivity. Beyond consultation, this approach favours joint deliberation on the different ways of knowing, experiences, and interests (intersubjectivity). Participants look to gradually build a consensus around a common solution or shared vision that best meets the local needs, aspirations, values, and capacities. Co-design increases the chances that the community not only welcomes the proposed solution but also becomes a promoter or championalongside other governing instances (local and governmental). Although it does require investing more time and resources, the co-design method brings together members of the community in design brainstorming activities, where storytelling can contribute.

• A

“hyphen”

to co-build solutions

The hyphen in fact defines an attitude toward something that is fundamentally different. […] Regardless what happens, the perspectives will remain different because they are determined by the history of Indigenous peoples but also their identity.

Gentelet (2009)

Managing forces is an important part of the participative process. In this regard, a climate of reciprocity between parties helps reinforce trust and enables active listening. Participants must work together toward this reciprocity and acknowledge the Indigenous contributions within this collaboration. Harmonious and equitable relations result in a “win-win” situation for all concerned (Koster et al., 2012). When the process responds to the expectations and investment of the community and recognizes their voices and ways of knowing, it leads to tangible and lasting benefits.

When accentuating reciprocity, the “hyphen” posture engages the different interpretations or opinions. Rather than trying to suppress them, authentic collaboration builds a bridge to unite and rally the different perspectives from both sides, Indigenous and non-Indigenous (Gentelet, 2009).

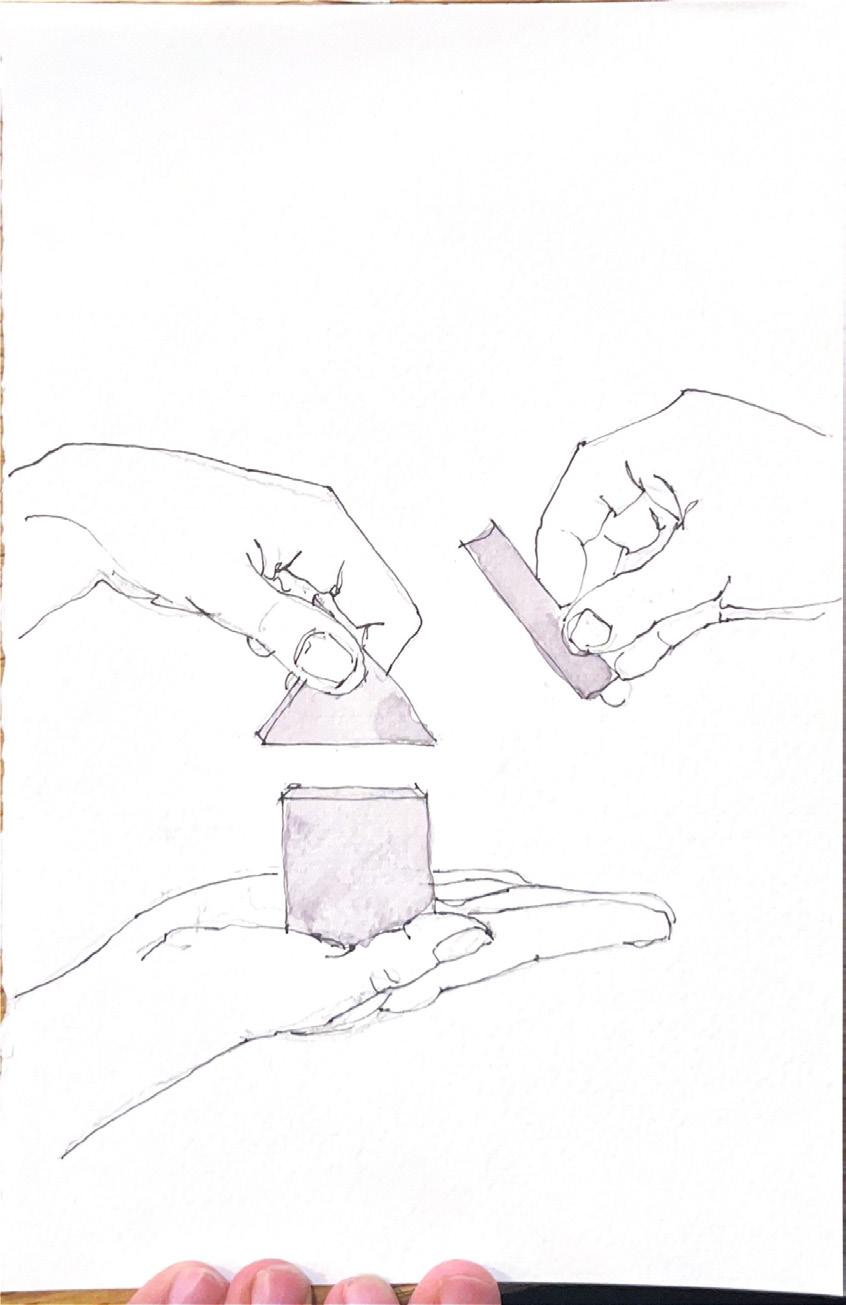

The co-design process uses deliberation to mobilize partners around a common goal.

Drawing: F. Gagnon and A. Corriveault-Gascon, 2023.

There are several ways to use the hyphen posture, such as cooperation between professionals and community members in undertaking a project, from design to construction. Co-building that involves

Indigenous representatives (thinkers, decision makers, doers) makes it possible to share and transfer knowledge and know-how to support local expertise and ways of knowing. Non-Indigenous professionals involved in the project can thus acquire vital knowledge about traditional building techniques and actions that foster respect for the land’s resources. Selfbuilding that is fully or partially facilitated by collaborations with partners (such as training programs) is yet another way to develop skills and autonomy in a community.

Co-building or self-building are opportunities for cooperation between several types of interested partners: professionals, entrepreneurs, trainers/ mentors, and members of the community.

Drawing: A. Présumé, 2023.

• Respecting the temporal aspects and timing

Collaborating with Indigenous partners often means encroaching on their calendar, which follows very different cycles, priorities, and types of governance and management.

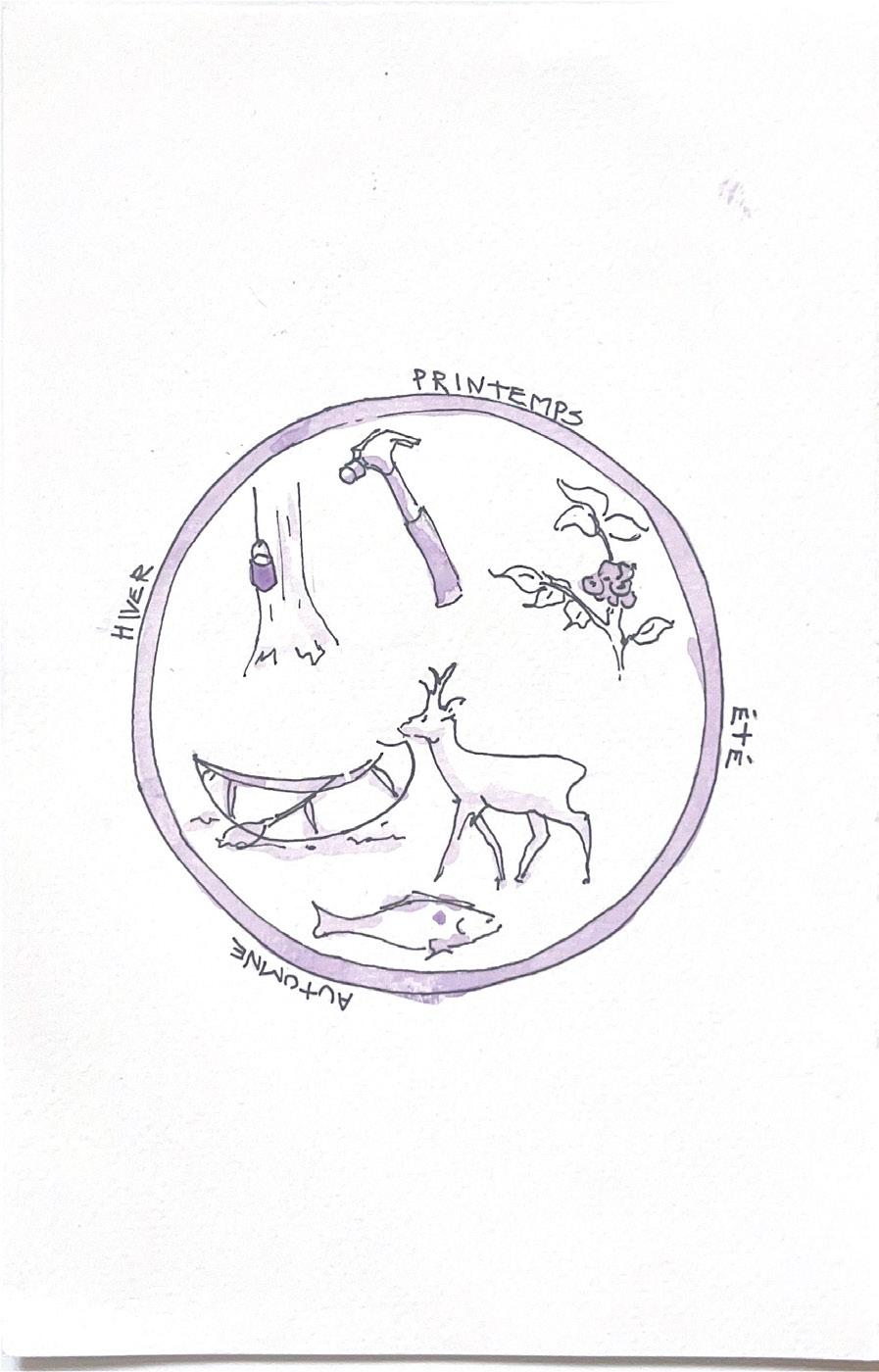

Respecting these local temporalities is crucial to maintaining a respectful working relationship. For example, the timing of collaborative activities must take into account the election cycle of the band council as well as the ways of life according to the seasons. Indigenous calendars thus include important seasonal and traditional activities on the land that can impact the scheduling of collaborative meetings.

Indigenous seasonal lifestyles and calendars influence collaborations.

Drawing: A. Présumé, 2023.

• Inclusive management and selfdetermination

Among the intangible factors determining the success of a working partnership are the achievements or the measures taken by Indigenous communities toward their selfdetermination. In the context of planning and architecture, establishing modes of cooperative or inclusive management for the community’s equipment (such as a service area) helps the community maintain control: decisions, responsibilities, risks (including

those perceived by the community). And with the right training opportunities, participating in the administration, operation, and maintenance of these infrastructures enhances autonomy and pride.

Cooperative management works above all to support local job creation, thus encouraging resilience in both individuals and their community. When used in architectural projects, this strategy acknowledges selfdetermination and helps decolonize planning and architecture practices by reestablishing a balance of power and control in favour of the community it serves.

Visit ‘Innuassia-um’ Planning in Innu Communities (2016), an illustrated guide for Innu professionals on the urgent needs regarding land expansion and housing renovations. www.innuassia-um.org

The co-management of facilities developed in partnership with communities focuses on Indigenous know-how and self-determination.

Drawing: A. Présumé, 2023.

Principles of Indigenous Architecture and Planning

This section presents architecture and planning principles that may prove useful in the design and development of culturally appropriate projects on Indigenous land. Emerging from various research projects and discussions with Anishinaabe and Innu communities over the years, these principles define shared ways of knowing and values that can serve to begin a dialogue or co-design process for community infrastructure (such as service areas) with an Indigenous community involved in a transformation project on its land. To support these principles, concrete actions are proposed by showing what has been successful elsewhere as well as design projects achieved at Université Laval’s School of Architecture (2022-2023), in collaboration with the ABL community.

The 12 principles are divided under 4 themes corresponding to complementary domains or levels of intervention:

The following precedents may be consulted in greater depth by clicking on the links listed at the end of Part 2. For more info on the projects, go to: Ideas for Kitiganik (habiterlenordquebe.wixsite.com/ideas-for-kitiganik).

Site Planning

Principle 1

Principle 2

Principle 3

Today, stuck as we are, what we need is more wild thoughts, wild spaces, and a good dose of wild freedom.

Indigenous ways of living are grounded in the notion of relationality, where human environments, the natural environment, and the spiritual world are inextricably connected. Introducing constructions or planned facilities on Indigenous land can affect the relationships communities have with the land. In addition, any planning strategy or transformation (frugality, repairs) must contribute to maintaining—even strengthening—these bonds of respect, to enable communities and future generations to practice activities that are vital to individual well-being and to the enhancement of local ways of knowing (Commune frugale, 2022). Actions that involve lasting and culturally appropriate planning must therefore consider Indigenous views of the land, dialogues with the landscapes, and how it is all anchored in ways of living.

Land and community

Connections to the land: Keys to sustainable community planning

In the Indigenous worldview, the land is a place of importance for the practice and expression of culture, as well a source of subsistence and well-being. For communities, the relational dynamics with the land are what helps them maintain strong identity, spirituality, and values.

In terms of reciprocal responsibility, how communities connect to the land plays a central role in their sustainable planning decisions and practices. These connections provide opportunities to develop projects that engage respectfully with the cultural and natural landscape.

Proposed actions

1.1 Footprint: limit the environmental impact of constructions to in turn minimise their impact on the ecosystems.

1.2 Community activities: contribute to activities in the community, on the reserve, and on the land by taking into account local realities, practices, and ways of knowing.

School on Nitassinan land

Uashat mak Mani-utenam, Québec

Architecture sans Frontières and Université Laval, 2022

The proposed school in the heart of Innu territory (Nitassinan) aims to preserve, share, and promote the culture of this community through a reappropriation of the land. A building placed directly in the woods invites youth to reconnect with their ancestral culture and the land, while supporting various daily learning activities.

This design encourages a strong connection to the land.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

For Anishinaabe of Rapid Lake, the culture of resistance and protection hails from a long history of identity crises and agreement contexts between different instances involved in the land’s management. Several of the community’s claims regard boundaries, planning, and infrastructures in an effort to preserve its way of life and enable each member of the community to thrive on their ancestral land.

Mitchikanibikok Inik

Algonquins of Barriere Lake

Été: rassemblements familiaux

Construction de barrages sur le lac Cabonga, inondant «des domiciles, un cimetière et un territoire important»

(Beaudet, 2017)

Hiver: retour au territoire de chasse familial

La majorité du territoire est prêté à des compagnies forestières

Signature de l’Accord Trilatéral

Création de la réserve de Rapid Lake

Protection de la culture et amélioration de la gestion du territoire et de ses ressources pour le bénéfice de tous

Le gouvernement fédéral invoque la section 74 de la Loi sur les Indiens

Landscape

Architecture and amenities in dialogue with the landscape

Despite being often imposed, the built environment of Indigenous reserves has adapted to the realities as well as the physical and natural characteristics of the host environment. Away on the land, in family camps, vernacular architecture or self-construction practices are common and develop through trial and error. Cottages and camps highlight a harmonious integration with the site and the surrounding landscape (Demeule, 2020; André-Lescop, 2018). This relation encompasses several considerations, including the passage of seasons. Open dialogue with the community is therefore vital to properly understand the importance of places, characteristics, or markers that hold the meaning given to the land, in each season.

Proposed actions

2.1 Template: design buildings with the ideal shape, volume, and integration to echo the landscape “without overpowering it”.

2.2 Topography: place the buildings in a manner that preserves unobstructed views of the natural viewpoints and surroundings and respects the topography.

2.3 Transparency: anticipate exterior stoops, openings, and extensions that maintain a strong connection to the landscape.

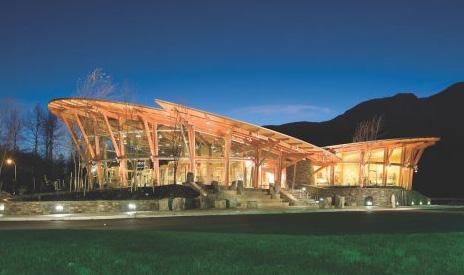

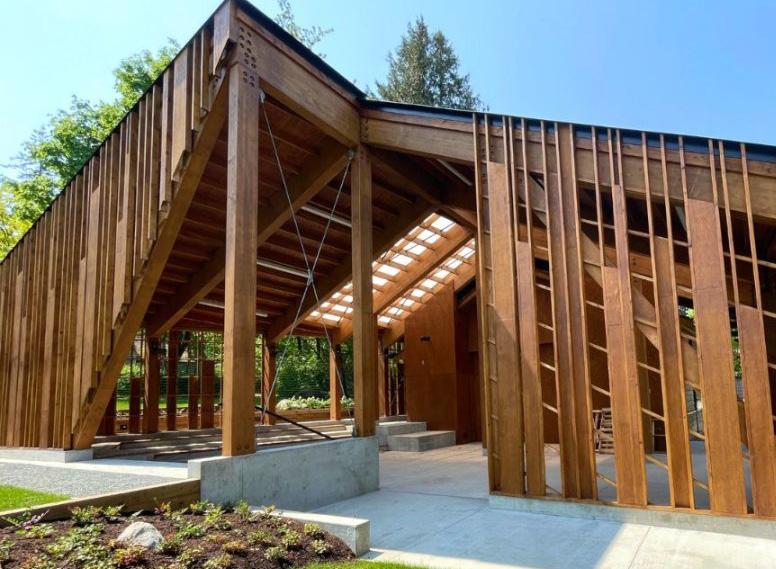

Squamish Adventure Centre

Squamish, British Columbia

Iredale Architecture + Dennis Maguire Architect, 2006

This tourist hub consists of a boutique, a coffeeshop, and an amphitheatre. Built using local Douglas fir, the volumetry evokes the mountainous landscape and soaring eagles, two key symbols of the natural and cultural landscape.

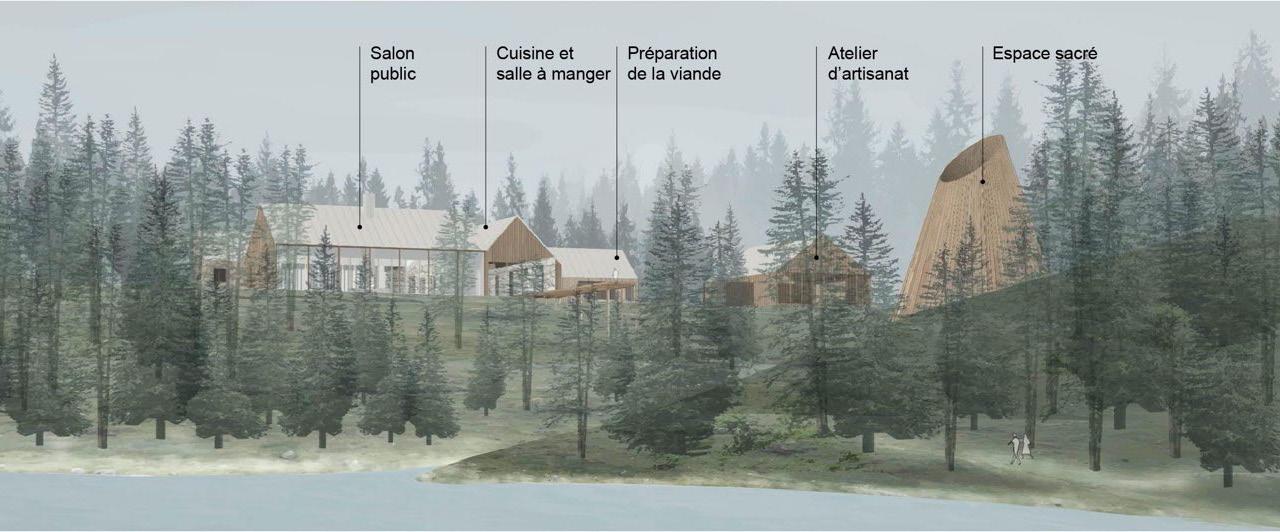

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

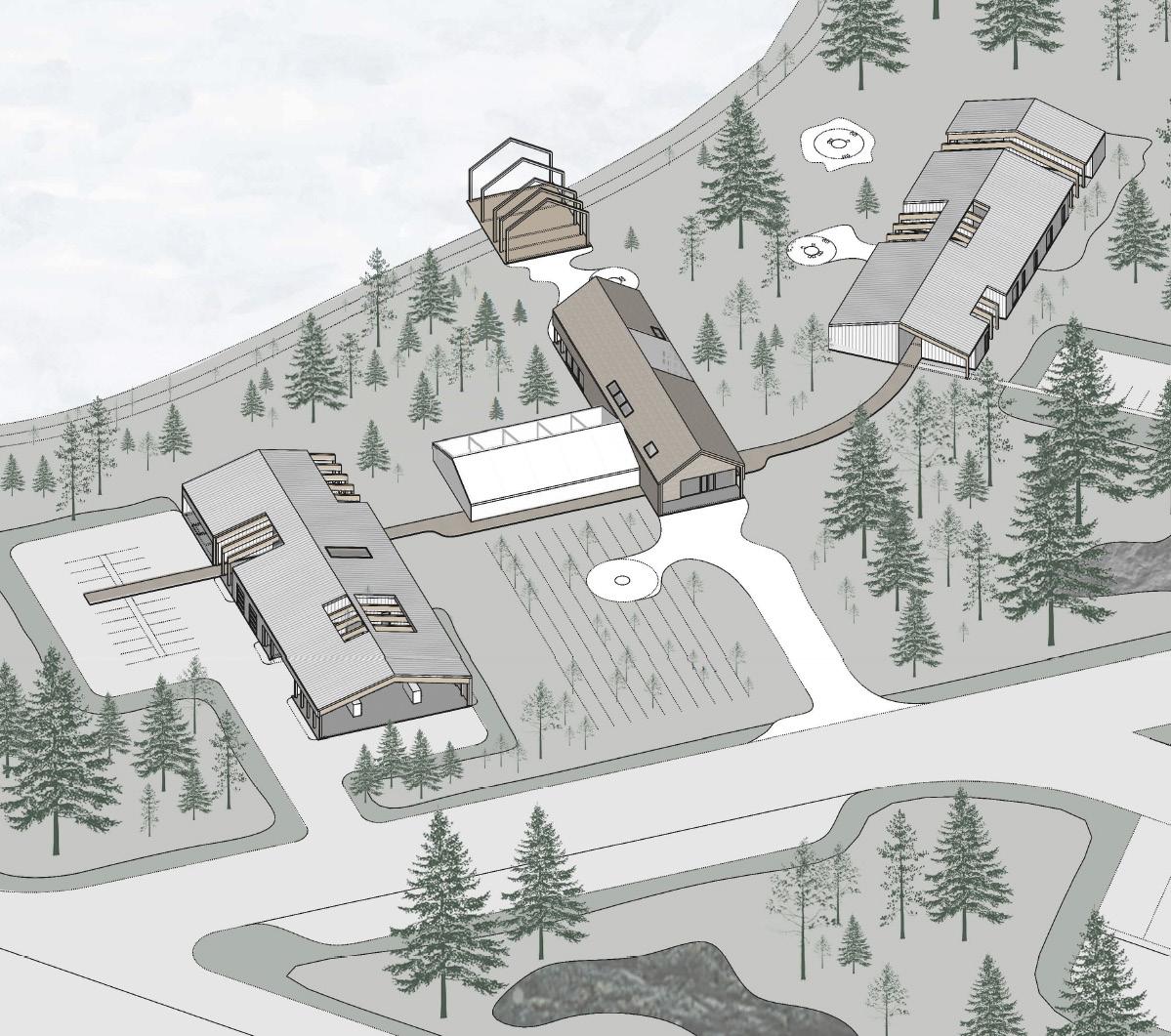

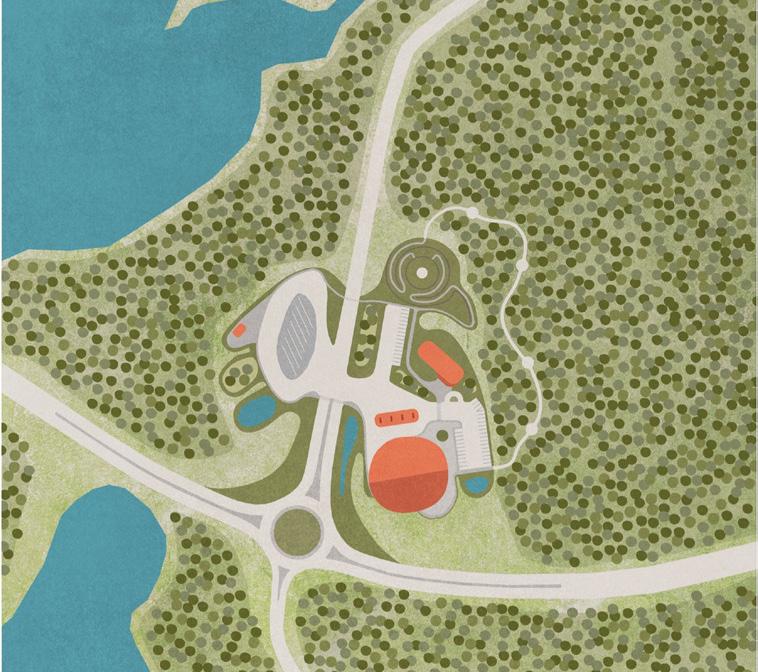

Architecture is in dialogue with the landscape, as the buildings coinhabit harmoniously with the forest, with forms, openings, and extensions that are in communion with the natural surroundings. As the forest is a major feature, the size and environmental impact of the structures are relatively confined. Here, the service area blends quietly with the landscape and roadway while marking its presence and that of the Anishinaabe community.

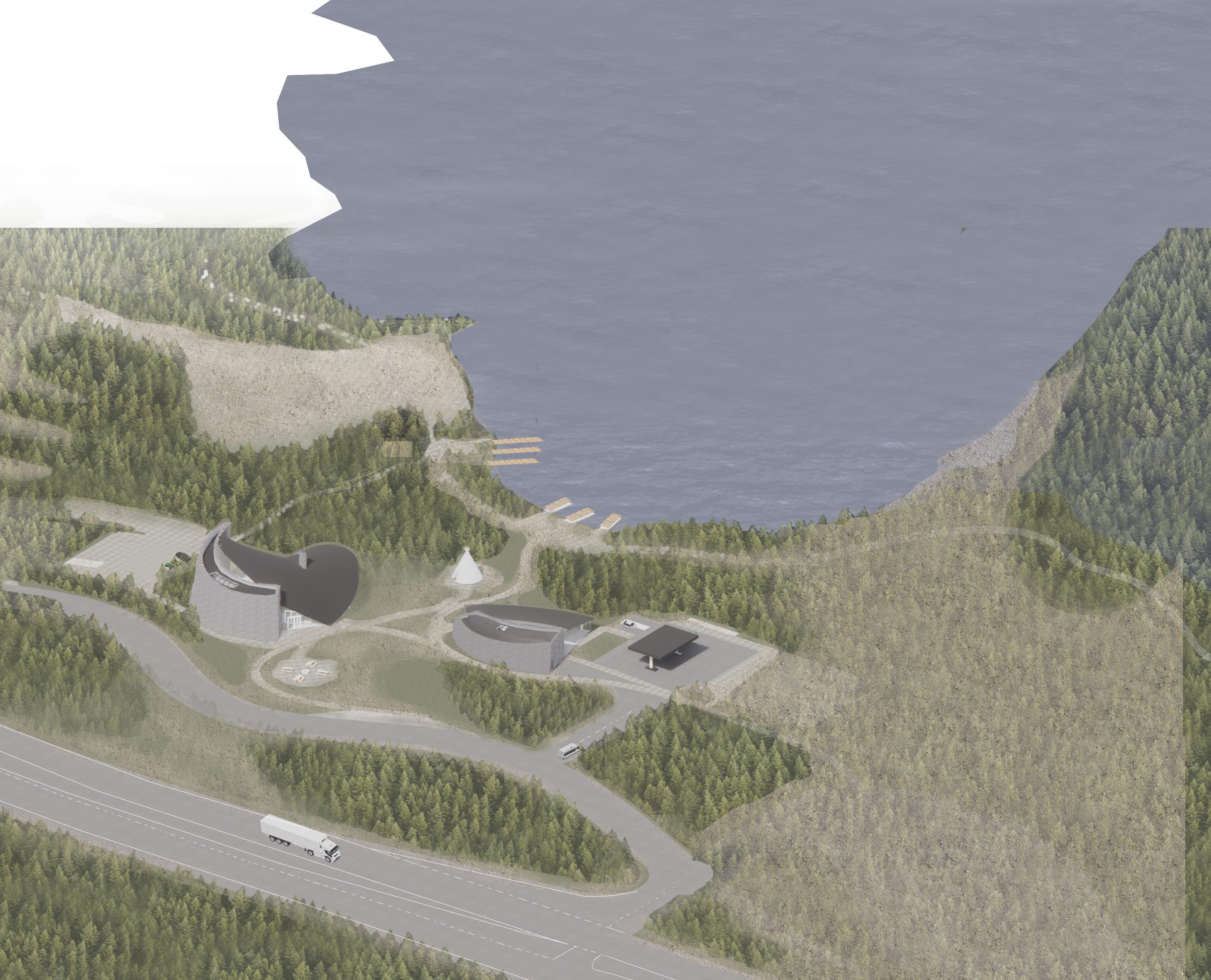

A service station close to the water

Maude Boulay, Université Laval, 2022

The proposed service area on Route 117 near Rapid Lake is close to the forest and a lake, which are important elements of the landscape and influence configurations. All the indoor and outdoor spaces interact with these natural markers that are dear to the community.

Anchoring

Symbiosis between the interventions and the environment

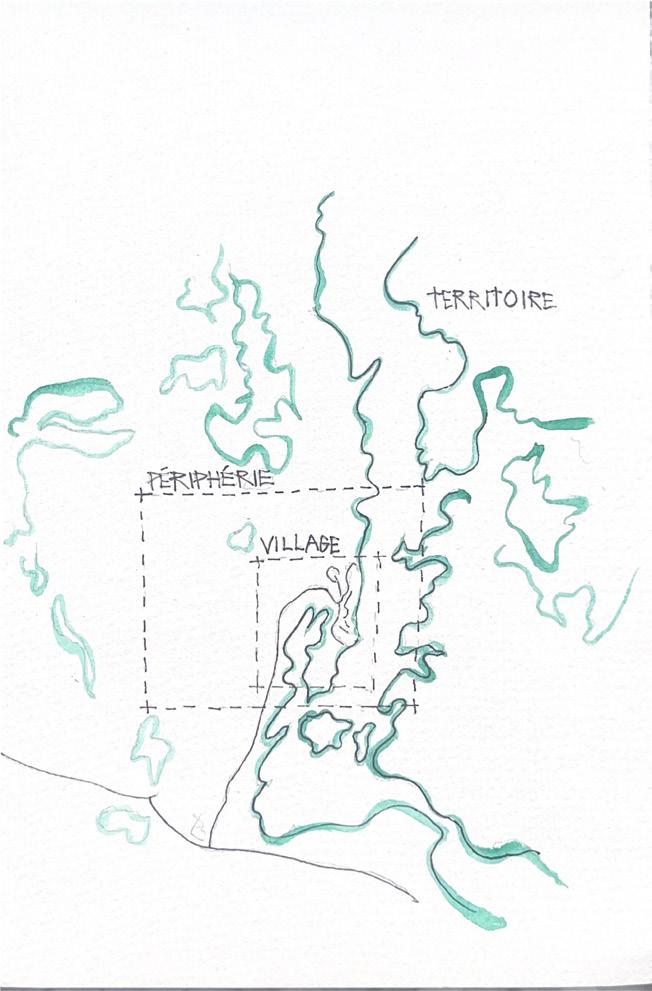

To intervene respectfully with the host environment, the site of a project must take into account the different relational dynamics and elements involved, such as its inhabitants, their ways of living, and their values.

Developing an architectural project calls for careful analysis of all elements that compose and influence the site on several levels (from the land to the village and to the homes). Understanding these formal, organizational, environmental, social, and cultural attributes makes it possible to plan strategies that are best suited to the context.

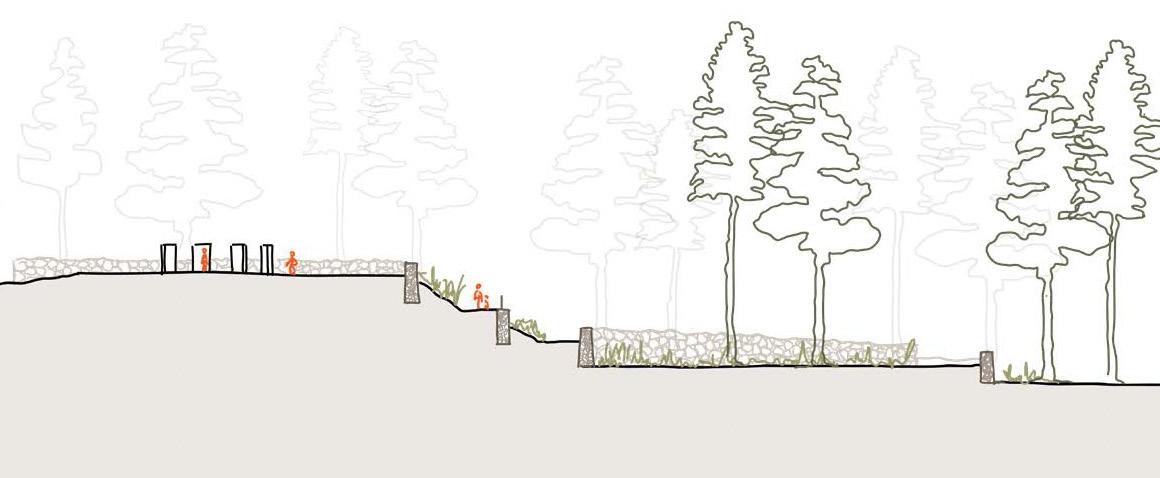

Proposed actions

3.1 Scales: develop a planning strategy for the site that takes into account all the levels of influence, both near and on the land.

3.2 Orientation: implement and steer actions to best suit the surrounding area, the environment, and the seasons, in respect of local practices.

3.3 Outdoor spaces: include significant and usable outdoor spaces, particularly around the community buildings.

Gloucester Services

Gloucester, Royaume-Uni Glenn Howells Architects, 2014

The main building of this service area stands out by its linear configuration next to a wetland. The nearby pond, the green roof system, and the large openings attenuate the limits between indoors and outdoors, giving visitors better access to the site. It also houses stores and a food court offering exclusive local products.

Service area terrace overlooking the wetland.

Indoor and outdoor spaces blend in with the surroundings.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

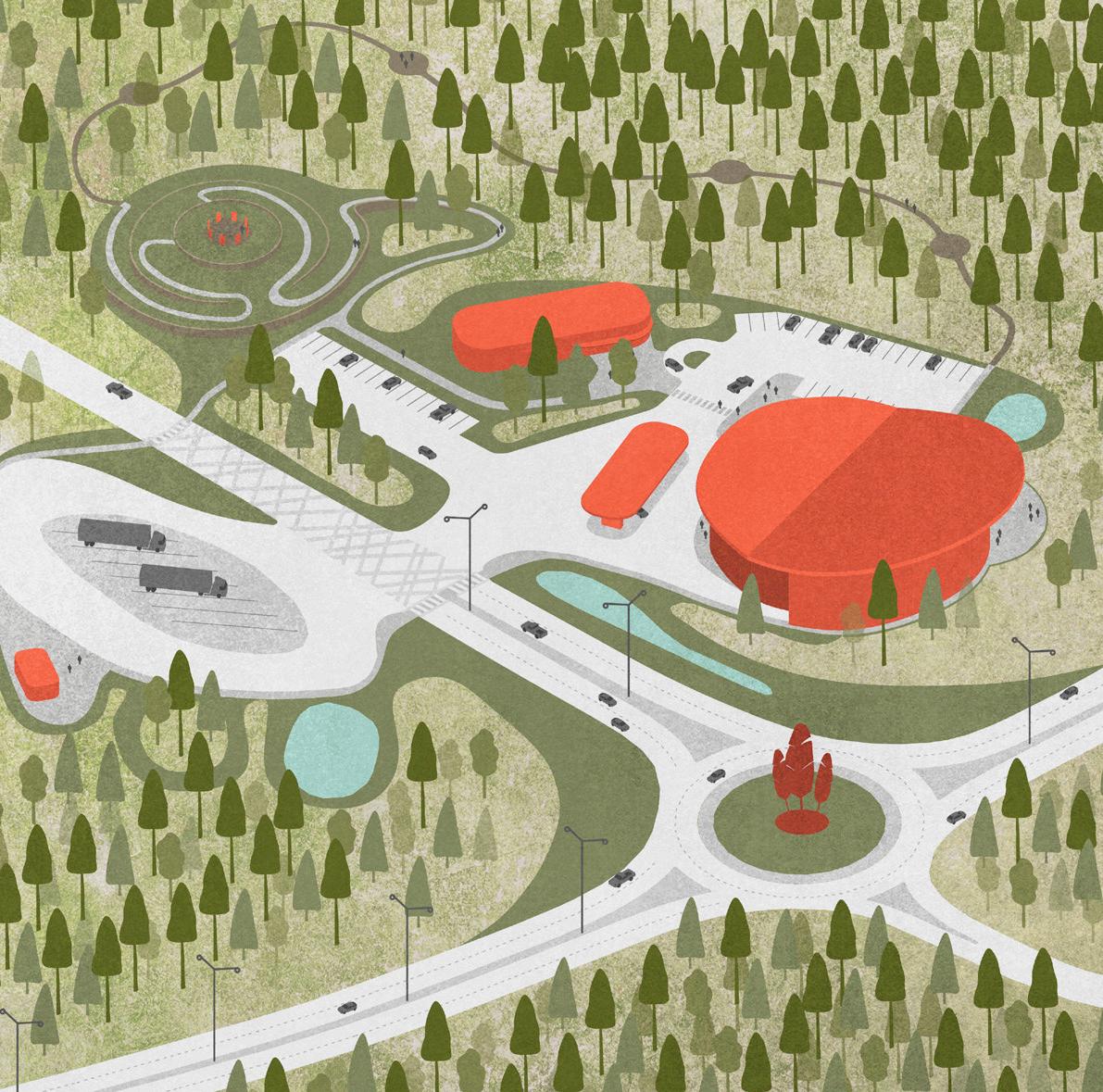

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

The heart of this expansion project on the Anishinaabe reserve is represented by a large circle, which holds significance for Indigenous peoples. The community buildings are designed to face each other to form an ensemble that depicts a strong identity in a large gathering space designed to preserve and highlight the forest. Openings between the buildings make it possible to appreciate the connection—and access—to the land.

Youth Center

Charlie Wenger, Université Laval, 2022

This housing facility for Anishinaabe youth provides resources to those who need support and healing in a context separate from the reserve. Interconnected spaces form a large nurturing circle. The site is optimized to enable daily access and connection to the bush. Together, the building and its site contribute to the well-being of its residents.

Resilient Ecosystems

Principle 4 Forest

Principle 5 Water

Principle 6 Soil

We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded, but also for our relationship to the world. We need to restore honor to the way we live, so that when we walk through the world we don’t have to avert our eyes with shame, so that we can hold our heads up high (...).

Robin Wall Kimmerer Braiding Sweetgrass, 2021

Indigenous way of life is inseparable from the land. Subsistence activities such as hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, or traditional medicine all depend on the preservation of the environment and its ecosystems. Indeed, the forest and the animals, the water sources, and the soils and ground covers are vital resources that support the practices, subsistence, and well-being of the communities and their future generations. Many Indigenous reserves and communities have settled in or are close to sensitive natural environments that also house family camp sites. Their responsible transformation thus relies on principles and actions that respect the land’s three vital ecosystems: the forest, the water, and the soil.

Principle 4 Forest

Architecture in harmony with the forest ecosystems

The forest is an integral part of the daily lives of many Indigenous communities, both on reserves and on the surrounding land. Deep in the Indigenous imaginary and ways of living, the forest is not only a sacred place but also a nurturing ecosystem and a haven for healing. For First Nations, the forest evokes stories, myths, and spirits connected to significant natural places. This holistic appreciation of the forest resembles “ecocentric” ethics that are mindful of ecosystem integrity, in contrast to Western “extractivist” views (Bellefleur, 2019). First Nations consider themselves stewards of the land by encouraging eco-responsible gathering practices to preserve both ecological richness and balance.

reuse and/or ensure the renewal of resources involved in planning or construction.

4.2 Cohabitation: encourage respectful cohabitation with the forest through ancestral practices: partial cutting, between-species connection, etc.

4.3 Conservation: protect fragile forest elements, such as old-growth trees and wetland areas, to preserve and sustain important cultural activities.

Totest Aleng Indigenous Learning Centre Surrey, British Columbia O4 architecture, 2022

This centre for cultural exchange and expression houses a workshop as well as a semi-outdoor gathering space to promote culture and the arts. Many artists take part in performances inside the building, where a series of vividly decorated wooden panels depict the diversity of local fauna and flora.

The Centre is part of a protected forest area, which adds to the overall atmosphere.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

The rapport between an architectural project and the forest can be strengthened not only through its use but also its location. Here, a carpentry workshop established in the heart of the reserve becomes part of a training hub that promotes the ecoresponsible use of forest products. This proposed community equipment echoes the subsistence practices of the Anishinaabe and their desire for the sustainable protection of forest lands.

A

healing center on the land

Maude Senay, Université Laval, 2022

This centre for healing is located deep in the forest, which plays an important role in the daily lives of its users. As with other elements, the forest is vital to the centre’s operations as an integral part of the healing process of its users and as a resource for respite and renewal.

Principle 5

Water as a vector for identity and well-being

Waterways are crucial in supporting the cultural activities of Indigenous communities. Lakes and rivers enable the members to reach land to hunt, fish, and gather berries or medicinal plants. These activities demonstrate this close connection with the land. Dam building, contamination pollution, and climate change have profoundly affected the relationship several communities have with their surrounding waterways—which are also sources of drinking water. Furthermore, erosion of the shores of reservoirs, lakes, and rivers can influence the safety of planning and design (and sense of security) in communities.

Proposed actions

5.1 Permeability: propose layouts that optimize natural porous surfaces to preserve healthy underground water sources.

5.2 Ponds: integrate retention and filtration ponds for runoff waters.

5.3 Vegetation: protect the Indigenous vegetation and revitalize to combat shoreline erosion and maintain soil integrity.

Aire de la baie de Somme

Sailly-Flibeaucourt, France

Bruno Mader architecte, 1999

Introduced close to a retention pond, this rest area is integrated within the ecosystem of nearby Baie de la Somme. The pond is an integral part of the outdoor areas that include a terrace extending from the restaurant area, which has an abundance of windows. This architectural ensemble showcases the attractions and natural highlights of the land while respecting the integrity of the surrounding ecosystem.

The pond is part of a protected wetland and valued cultural landscape.

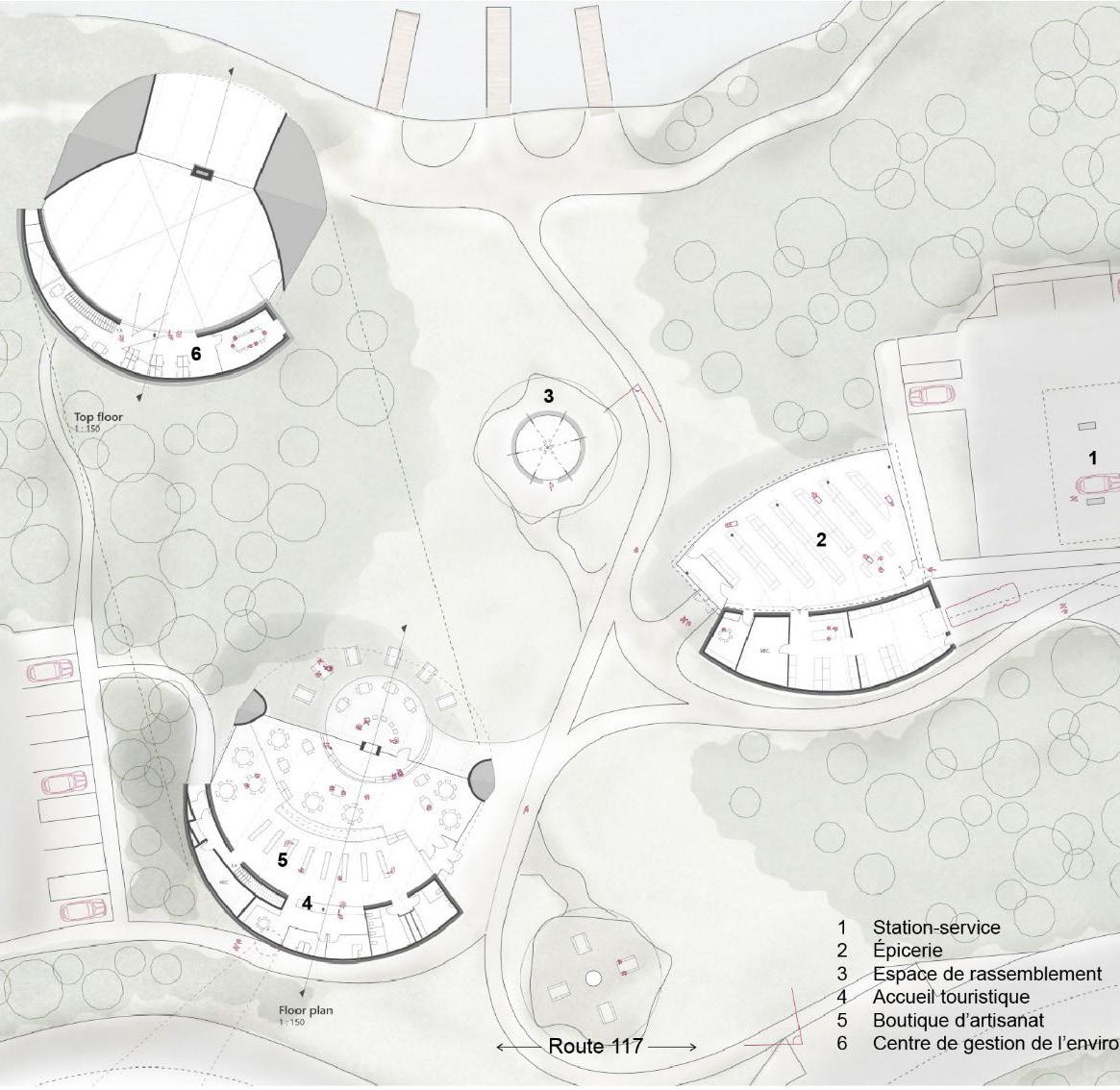

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Nin

Takim - Ecotourism rest area and anishinaabe land management

Claudel Poirier, Université Laval, 2022

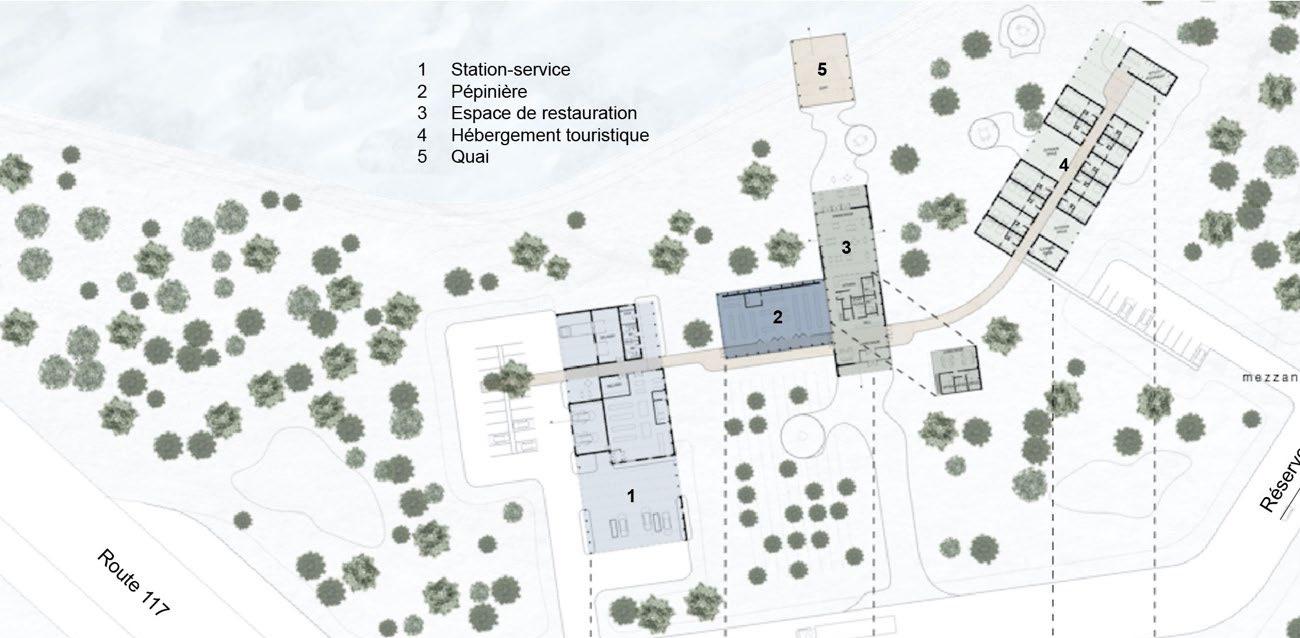

The rest area and ecotourism centre on Route 117 serve as a portal to welcome visitors who have an interest in the community and the land. Consisting of essential services (gas station, grocery store) and a craft store, these ecotourism facilities provide spaces for interpretation, social gathering, and offices, all managed by the Anishinaabe community.

The reception building provides a large gathering area inspired by the surrounding natural elements, along with generous views of the reservoir, which plays an important role in the connection Anishinaabe have with the land. Walkways and other design elements guide visitors toward the shore, another area that is an integral part of the ensemble—and the visitors’ experience.

Principle 6 Soil

Supporting activities in all seasons

Mother Earth plays a key role in maintaining connections between the different elements of the land. The land has witnessed many mutations and migrations of Indigenous communities that have travelled and lived upon it through many generations and many seasons. Its omnipresence in how land is perceived informs the integrity and growth of its natural ecosystems—a priority in any and all development projects involving Indigenous communities.

Proposed actions

6.1 Fragile soils: plan easily transformable layouts with the least amount of impervious paving to preserve fragile soils and vegetation.

6.2 Reutilisation: reuse soils and other excavated/displaced materials for new layouts and constructions.

6.3 Topography: respect the terrain and natural hillsides by avoiding excessive amounts of landscaping and support structures.

Saugeen Creator’s Garden and Amphitheater Southampton, Ontario Brook McIlroy Inc., 2021

This outdoor amphitheatre, adjoining a tourism visitor centre, is part of a garden park managed and maintained by the Saugeen Abishinaabe community. The groundwork and local stone used tell the story of this place, which was once an ancient battleground and the location where a treaty was signed with Saugeen First Nation. The garden offers several separate rest areas, all connected by a stream.

The topography highlights the pathways on this sacred site.

The amphitheatre is built into the topography.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

The service area uses the soil to showcase its symbolic value for the community. It is shaped like a bird, another symbolic element in the hearts and minds of Anishinaabe. The facilities include an inn, a restaurant, a grocery store, and an interpretation area. Walkways and different topographical levels lead to the park (the bird’s head is made from excavated soil), thus enhancing the experience for visitors.

The respectful manipulation of the soil contributes to telling a story while guiding visitors toward significant spaces, such as the nearby pine forest or the interpretation area showcasing the community’s way of life.

Innovative Programs

Principle 7 Flexibility

Principle 8 Diversity

Principle 9 Feasability

This is not yet a consultation. In order to raise awareness, support local capacity and generate economic growth, we must first be part of the process leading to change in our community.

Enhancing the cultural richness of communities takes place through the creation of community amenities and housing that best meet the needs and aspirations of the residents, in a variety of contexts. This balance can be achieved using functional programs that listen to the ways of knowing, experiences, realities and capacities of the community, as well as their traditional and daily practices. Thinking “outside the box” creates opportunities to co-produce new programs that differ from standard models that do not suit Indigenous perspectives or way of life. Indeed, innovative initiatives using the community’s infrastructures and equipment better reflect Indigenous ways of thinking and doing, such as solidarity and cooperation to encourage self-determination and autonomy.

Flexibility

Architecture and planning adapted to the needs

First Nations assert and value their knowledge systems and their cultures. Traditional activities inherited from a semi-nomadic past exist alongside those of daily life, which often take place in urbanized areas “connected” to the world. Indigenous peoples thus navigate between tradition and modernity on a continuous path of knowledge sharing.

Vernacular architecture has always stood out by its capacity to adapt to challenges or changing situations. It serves to create gentle and flexible living conditions that adjust to meet evolving needs. To successfully welcome diverse activities over the seasons, contemporary Indigenous architecture and planning must adapt to the changing dynamics and different ways of using space.

Proposed actions

7.1 Gathering spaces: design flexible indoor/outdoor meeting spaces to promote local culture and the transmission of knowledge.

7.2 Multifunctionality: encourage the harmonious cohabitation of compatible uses for different clienteles, according to season cycles and the needs, and schedules.

7.3 Versatile spaces: plan less “specialized” spaces so they can be easily adapted to changing situations or functions.

Hoop Dance Gathering Place

Hamilton, Ontario

Brook McIlroy Inc., 2016

These traditional gardens and gathering spaces honour the heritage of the different nations who have occupied this place. The log structure is conducive to gatherings, cultural interpretation activities, contemplation, and more. Form and expression recall elements of the traditional tent or long house.

The open, circular form brings people together.

This space is both simple and multifunctional.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

The central area of this large communal circle (below) extending from Kitiganik is a place of flexible sharing that can adapt to each activity and season. The cercle unites a seniors’ residence and a school on either side by providing spaces for the transmission of knowledge between generations. The absence of permanent layouts makes this a versatile and easily adaptable space to suit the community’s needs and lifestyle.

Seasonality and adaptability to many types of community life activities are important criteria to consider when designing a project on Indigenous land. Here, the central outdoor space is designed to facilitate several scenarios and opportunities to come together from season to season, while the wood structure allows for a variety of uses, such as the installation of temporary tipis or traditional craft workshops.

Principle 8 Diversity

A variety of well-planned spaces

As they do everywhere, daily activities in Indigenous communities are numerous and change constantly, depending on the life trajectories of its members: inhabiting, coming together, working, learning, having fun, taking care, creating, etc. In response to this, a mix of different types of buildings and spaces covering different uses, such as housing, provide residents of all ages with several options. On the community level, the growth and well-being of its members rely on having easy access to daily services that are close to their homes and meet their needs. Diversity is thus judiciously organized to suit the aspirations of groups and individuals who share or will share the space.

Proposed actions

8.1 Complementarity : connect buildings and spaces with complementary functions to meet a variety of needs.

8.2 Exchange: encourage social interactions by keeping the different areas of activity close to the residential areas.

8.3 Transfer of knowledge: include spaces that encourage intergenerational relationships and support knowledge transfer.

Lac-Simon Marché Bonichoix and Community Centre

Lac-Simon, Québec

ARTCAD Architectes, 2014

The grocery store and community centre are located in the same building at the entrance to the Lac-Simon reserve. For this Anishinaabe community, these two services have generated greater autonomy and a sense of pride. The grocery store is a cooperative managed by the members and the centre, which also has a community kitchen, can accommodate more than 600 people for regular intergenerational gatherings.

The community centre hosts many different intergenerational events.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

Organizing this community hub to expand Kitiganik is inspired by the traditional medicine wheel for the location of its buildings. Services for adults, Elders, youth, and children are proposed, in constant dialogue with the land, the seasons, and the legends of the community. Programming reflects Anishinaabe ways of life and worldviews.

This service area has a gas station as well as several other amenities, including a grocery store, a craft store, a restaurant, offices, and an inn, not to mention organized outdoor activities. In addition to flexibility and adaptability, this diverse programming provides diverse local job opportunities.

Principle 9

Feasability

Featuring local ingenuity

Proposed actions

The feasibility of a project in architecture or planning depends on a group of parameters, objectives, and factors judiciously adjusted to the demands and interests involved. It primarily focuses on the means to politically, financially, and socially attain realistic goals under the best possible conditions. Feasible and sustainable projects with/for communities involve an approach that respects local capacities and perspectives. For example, understanding the community’s relationships with time and the seasons helps to be on schedule and efficient. Using local building knowhow and resources also helps develop equipment and infrastructures that are easier to use, maintain, transform, inhabit, and appreciate.

9.1 Collaboration: identify the construction/planning priorities and co-establish design goals with the community.

9.2 Accessible materials: use local, resilient, natural materials, and simple construction methods.

9.3 Training: encourage the input of local designers and builders through various strategies (mentoring, construction coop, etc.).

House renovations in Kitcisakik

Kitcisakik, Québec

Guillaume Lévesque + ASF Québec, 2009-2015

This initiative actively involving the community led to the renovation of 30 houses. The project goes beyond the realm of architecture by providing members with training in carpentry. Beyond the actual renovations, the community reaps longterm benefits, including heightened self-determination and pride.

An inclusive renovation project with a “training by doing” approach.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Making our Homes

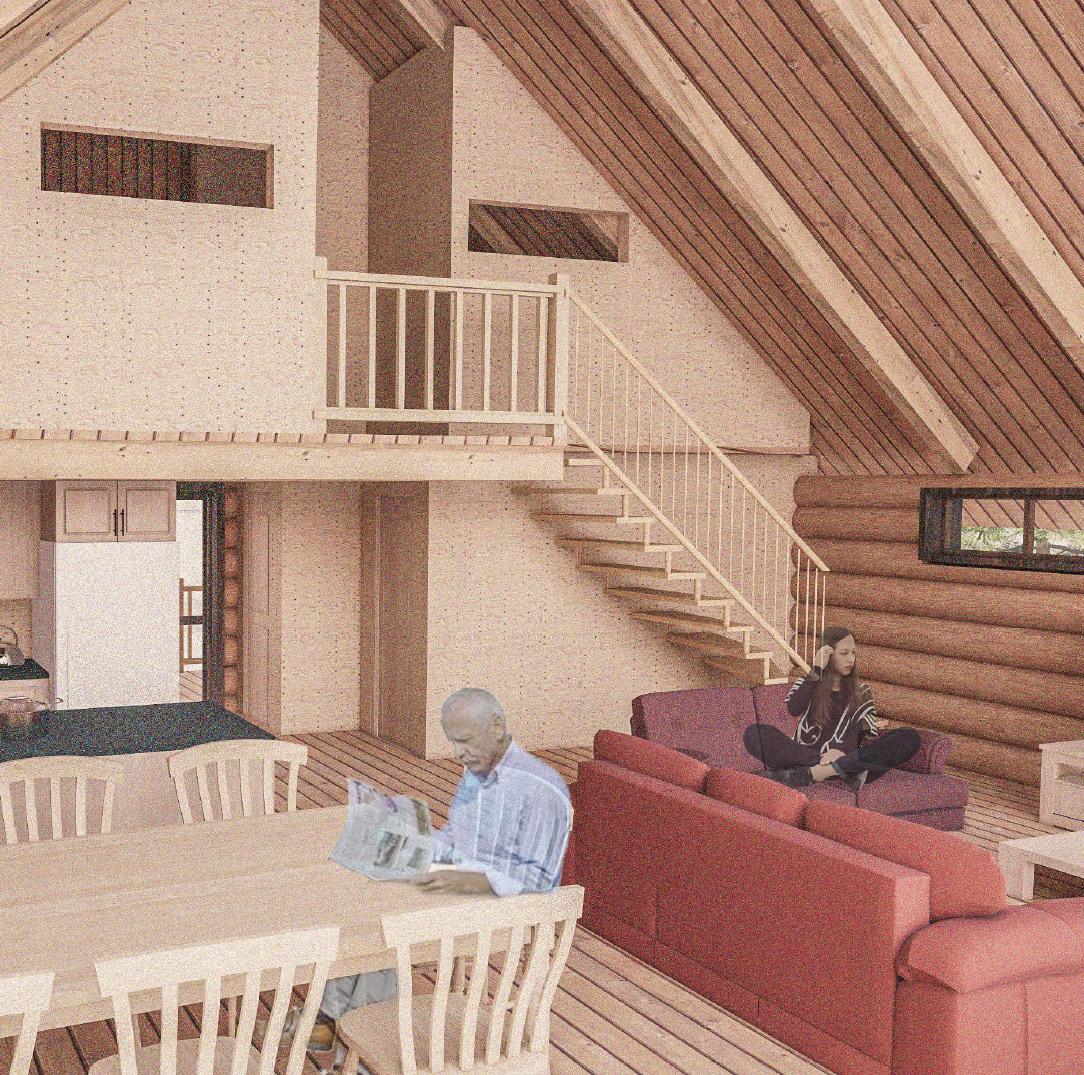

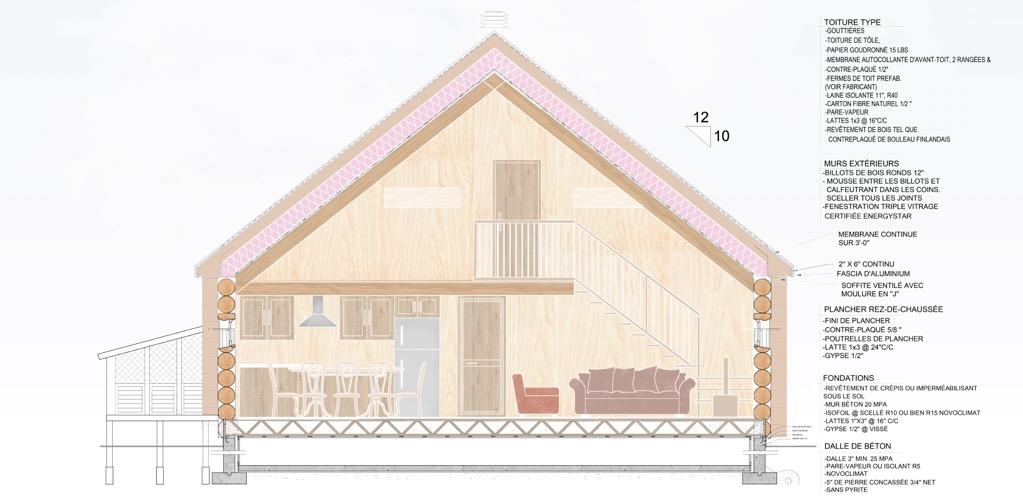

Sarah-Lou Gagnon-Villeneuve, Université Laval, 2022

This renovation project for homes in “old” Kitiganik employs simple and easily reproducible construction methods. The integration of local wood construction techniques (cabins, tents, sheds, canoes) enhances appropriation while encouraging the transmission and value of Anishinaabe know-how.

Within the layouts and between the houses are spaces for sharing (community workshop areas) and for traditional community activities. With the appropriate funding, the community is able to use these amenities as they wish, at their own pace.

Architectural Identity

Principle 10 Markers

Principle 11 Figures and symbols

Principle 12 Materials

We are not the things we deem important. We are story. All of us. What comes to matter then is the creation of the best possible story we can while we’re here; you, me, us, together.

Richard Wagamese Medicine Walk, 2014

Historically speaking, many buildings and amenities have been imposed on communities, with little or no collaboration. As a result, the built environment on reserves has contributed little to the affirmed expression of Indigenous culture, values, and identity. Today, communities are taking the reins in projects that best suit them and their views for the future. Adopting collaborative co-design and planning methods are therefore opportunities to question Western processes and systems by integrating Indigenous ways of seeing, thinking, and doing living environments. As with two-eyed seeing, self-determination and Indigenous voices not only are heard but also participate in the design decisions for the community.

Principle 10 Markers

The expression of culturally significant elements

Proposed actions

In built environments, orientation in the space and the construction of a clear mental image relies on visual points of reference. These distinctive landmarks are often noticed because of their form (such as a monument), height (a steeple), and relative position (end of an axis), or their symbolic importance (a memorial) (Lynch, 1960). In Indigenous contexts, these markers display easily identifiable characteristics of identity that are familiar to the community. Markers tell stories about landscape and the land. Far from stereotypical, they are holders of strong meaning, memory, and identity.

10.1 Visibility: design architecture and infrastructures that showcase the community’s identity for greater “visibility”.

10.2 Indigenous shapes: integrate new markers on the land to highlight local places, events, and community accesses.

10.3 Contacts: encourage contacts between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in culturally significant spaces to promote dialogue and nurture reconciliation.

Cree Cultural Institute of d’Oujé-Bougoumou Eeyou-Istchee, Québec Douglas Cardinal, 1989

Architectural expression that evokes Cree identity is not only a significant marker in the residents’ daily lives but also a visual landmark for visitors. The community collaborated closely with the Indigenous architect to imagine a visual structure that would echo the form and characteristics of long houses and traditional shaputuans, with a contemporary flair.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

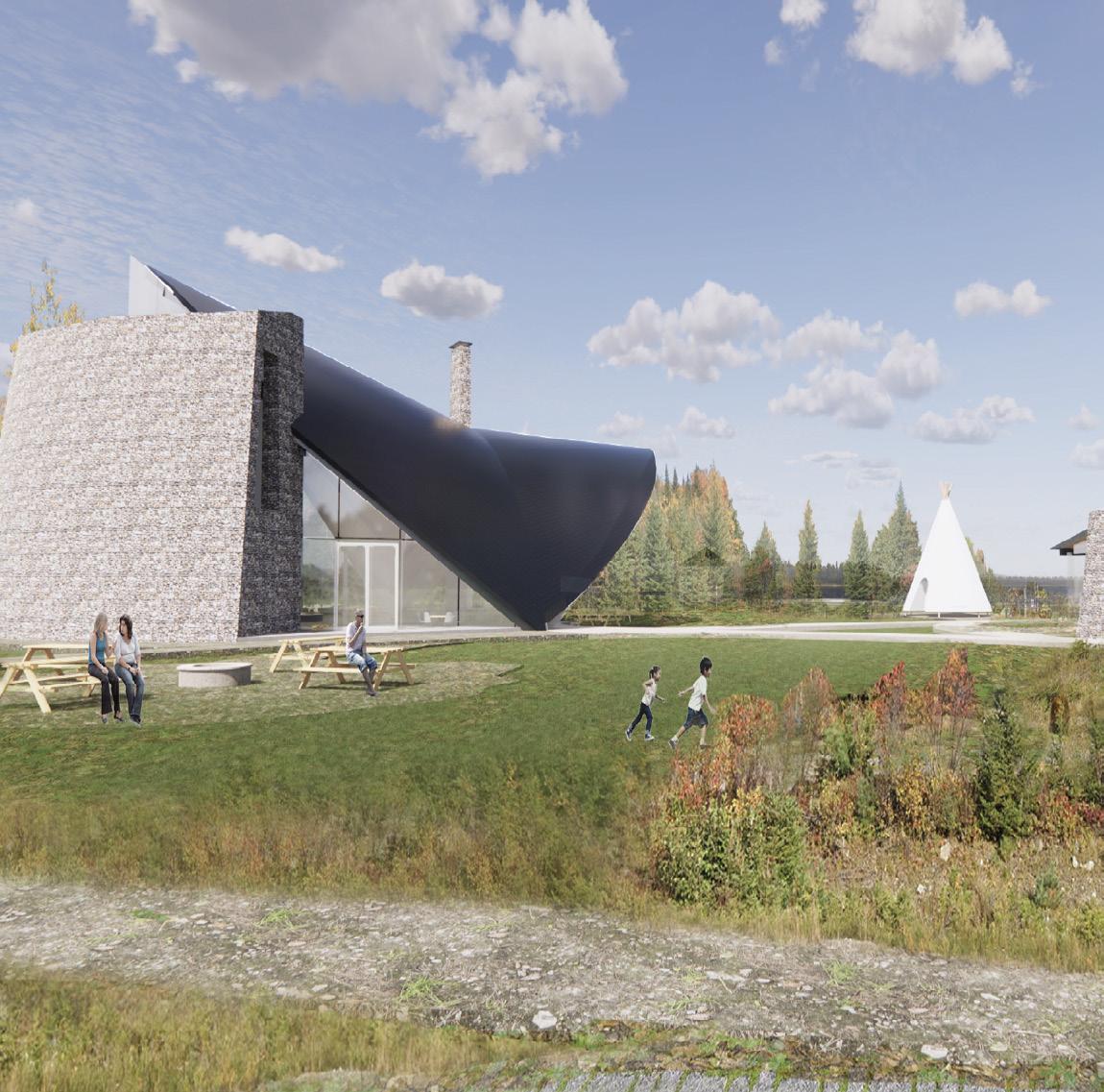

Nin Takim - Ecotourism rest area and anishinaabe land management

Claudel Poirier, Université Laval, 2022

Adjoining an ecotourism centre, this service area integrates formal and material elements of Anishinaabe culture. It becomes an identity marker along the highway to welcome visitors to a culturally specific experience that provides a space for intercultural exchange.

For example, the stone walls recall the territorial past of the Algonquin community of Lac-Barrière/Mitchikanibikok Inik, which means “people of the stone dam” (Beaudet, 2017). The shape of the buildings echoes Indigenous traditional ways of building and showcases Anishinaabe identity.

provides a welcoming space for intercultural activities

Principle 11

Figures and symbols

Bearers of imagination and identity

Proposed actions

The worldview of Indigenous peoples is grounded in the connections with the land, including the natural environment, living beings, ancestors, and the cosmos. These relationships do not mark reality: they are reality. Oralbased knowledge, traditions, and artistic works translate and express this relational reality through symbols that celebrate the connections between the living and the spiritual worlds. Integrating symbols emerging from the traditions and imagination of Indigenous communities contributes to a greater spatial expression that is both meaningful and culturally rich.

11.1 References: integrate specific markers in the architectural language that refer to tools, figures, and animals that appeal to local stories, art, and imagination.

11.2 Circles: adopt circular forms and layouts as a recurring symbolic theme to express community identity.

11.3 Traditional architecture: draw from traditional forms and ways of building to give meaning to the contemporary.

Canadian High Arctic Research Institute

Cambridge Bay, Nunavut

EVOQ architecture + NFOE architecture, 2019

This research centre celebrates how Inuit occupy space. The indoor areas respect the principles of interconnection and openness. The circle and the curved designs dominate in both the indoor and outdoor spaces, in reference to a community igloo. Drawings by local artists display several motifs and symbols of Inuit imagination and are an integral part of the ambiance.

The circular space recalls that of the igloo and the talking circle.

Many symbols, such as animals, are highlighted in the architecture.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Let’s have a yarn!

Alice Corriveault-Gascon and Florence Gagnon Université Laval, 2023

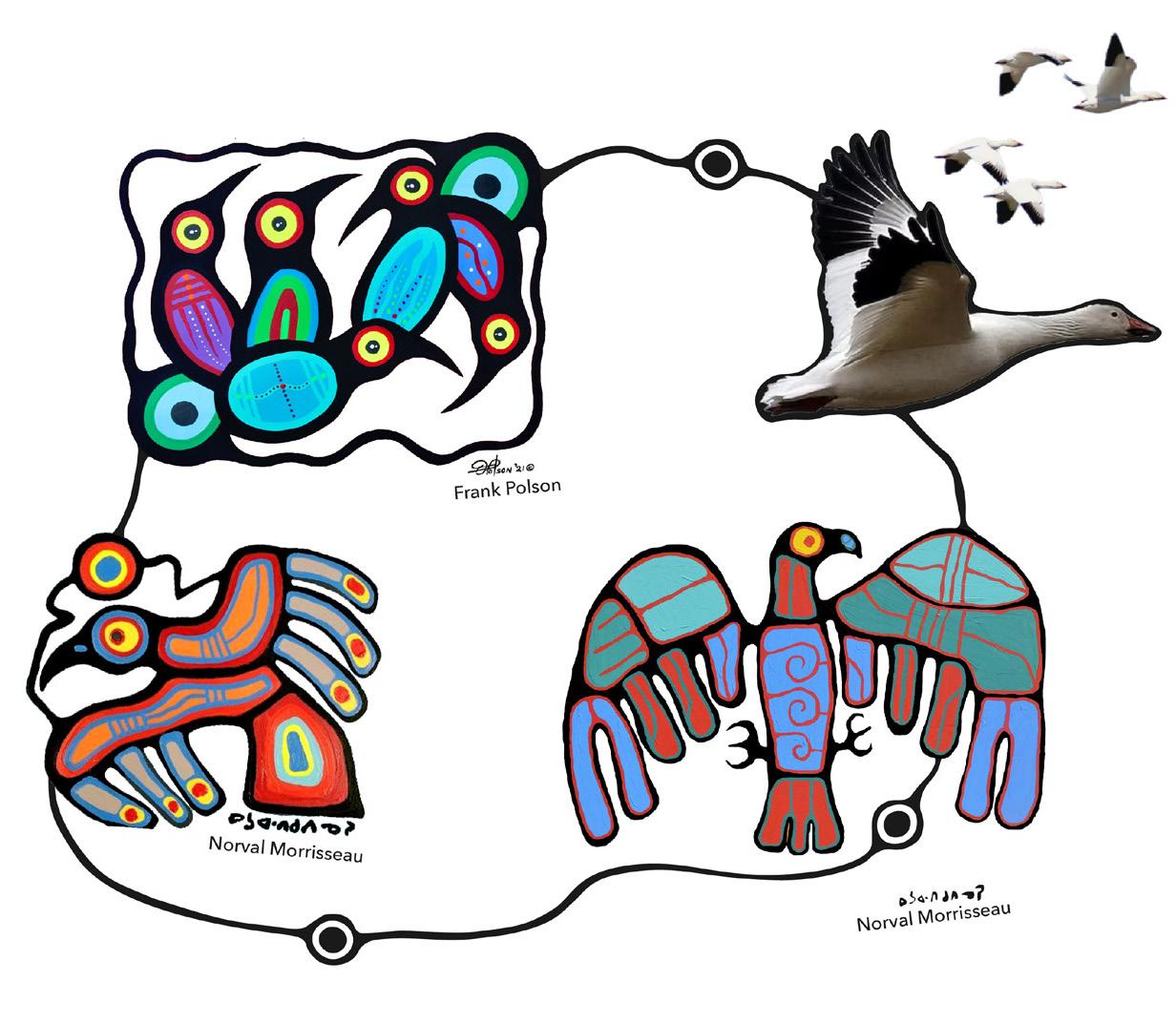

This service area is shaped like a bird, which for many Indigenous peoples is a symbol of great significance and the subject of numerous works by Anishinaabe artist Norval Morisseau. The layout therefore incorporates a proposed reinterpretation of the bird’s silhouette: service pavilion, inn, parking areas and ponds (wings), interpretation park (head), Route 117 roundabout (tail), and walkways (life cycles).

The symbolic interpretative work found throughout the site is expressed without denaturalizing the nature of the place, nor the meaning it holds for the community. Its goal is to mark the imaginary through an Indigenous way of seeing the world that guides the sustainable transformation of the land in a different light.

Principle 12 Materials

Natural materials to enhance the connection to the land

Natural materials that respect the relational dynamics with the land are not only useful but highly symbolic. For example, trees are vital to the fabrication of habitats, canoes, baskets, and numerous other daily objects. The meaning given to material resources is thus related to respecting the integrity of the ecosystems and a responsibility toward the land: we use what we need by optimizing transformation as a way to acknowledge the “gift” received from the land. Integrating local materials in the design and construction of buildings and amenities thus provides opportunities to “materialize” this attachment to the land while contributing to the ecological sustainability of these constructions, with low impact on the environment.

Proposed actions

12.1 Local materials: choose local natural materials for building constructions and amenities.

12.2 Crafts: incorporate vernacular, traditional, or contemporary ways of creating and assembling.

12.3 Natural light: consider natural light as an important component to enhance the connection to the land and the sense of well-being of users.

Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre Vancouver, British Columbia Formline Architecture, 2018

Built in the center of the University of British Columbia (UBC) campus, this interpretation centre promotes reconciliation as well as an open and constructive social dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. It provides several spaces where visitors can gather, listen, learn, and share. The centre uses such materials as pine (“woven” using local techniques) and copper (traditionally associated with important events).

An abundance of natural light leads to the reception area.

Zoom on Rapid Lake

Making our Homes

Sarah-Lou Gagnon-Villeneuve, Université Laval, 2022

The use of typical Anishinaabe materials and techniques serves as a cultural affirmation to enhance the feeling of being at home. Inspired by the cottages built on the land, this family housing project proposes wood logs for the exterior walls and plywood for the partitions.

In response to the needs and aspirations of its occupants, culturally appropriate housing is at the heart of many Anishinaabe concerns. With adequate funding and designs, culturally significant materials can contribute to strengthening the key role of habitat in a future bearing greater self-determination.

To conclude

The ABCs of Authentic Collaboration is but a modest contribution among the efforts toward reconciliation with First Nations. Its sincere goal is however to promote the decolonization of Western practices in architecture and planning for the benefit of these communities. The recommendations proposed here are the fruit of participative and creation-research projects in action, scientific findings, mutual learning and listening, much intuition and reflection, trial and error, and of course humility. This guide marks with a white stone the many experiences with Innu, Inuit, and more recently, with Anishinaabe of Rapid Lake, who have invited us to work together to imagine projects that speak to their needs and aspirations and are respectful of their land. These invitations and ways of sharing are anchored in relationships of trust, even friendship, that take time to take

root, to grow, and to bear fruit. The moments spent together listening, sharing, opening our hearts, understanding each other, and establishing bridges to “do differently” are all precious opportunities for healing, despite the heavy schedules, distances, and challenges (including the pandemic). Today, we appreciate and salute these important opportunities and contributions, which have profoundly changed us. This guide shares the fruits of our journey and is also a friendly postcard sent out to our Indigenous colleagues and friends. It is thus in this spirit that we throw our collaborative “pebbles” into the well toward future, mutually satisfying partnerships with Indigenous communities, as we continue to do our homework.

Geneviève,

Élisa, Samuel and Florence February 14 2024

Authentic collaboration

Indigenous Design Principles

References

André-Lescop, G (2018) Représentations du territoire et traits identitaires des campements traditionnels et contemporains innus : vers un aménagement culturellement adapté pour la communauté de Uashat mak Mani-utenam. Essai en Design urbain, Université Laval. André-Lescop, G (2019) En quoi le territoire ancestral peut-il inspirer l’aménagement contemporain des communautés innues? (Note de recherche). Recherches amérindiennes au Québec 49 (3) : 65-77. https://doi. org/10.7202/1074542ar

Barriere Lake Solidarity (2011) Algonquins of Barriere Lake vs Section 74 of the Indian Act. Disponible à : https://vimeo.com/23103527 (consulté le 16 mai 2023)

Bartlett C, M Marshall, A Marshall (2012) Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2, 331–340

Beaudet, G (2017) Les Algonquins de Lac-Barrière : une communauté de résistance. Nouveaux cahiers du socialisme 18 : 51-53.

Belleau, M, A Casault, G André-Lescop, et A Lebeuf-Paul (2011) ARUC-Tetauan : Habiter le Nitassinan mak Innu Assi : Représentations, aménagement et gouvernance des milieux bâtis des collectivités innues du Québec. Rapport de mi-parcours transmis au Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada-CRSH. Québec : Université Laval.

Bellefleur, P (2019) E nutshemiu itenitakua’ : un concept clé à l’aménagement intégré des forêts pour le Nitassinan de la communauté innue de Pessamit. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université Laval, Québec.

Bouchard, S (2021) Un café avec Marie. Montréal: Boréal.

Bussières, D (2018) La recherche partenariale : d’un espace de recherche à la coconstruction de connaissances. Thèse de doctorat en sociologie, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal. https://archipel.uqam.ca/11350/.

Caillouette, J, et S A Soussi (2017) L’espace partenarial de recherche et son rapport à l’action dans l’espace public. Dans Les recherches partenariales et collaboratives. Sous la direction de A Gillet et D-G Tremblay, 129-42. Québec : Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Clément, M, F Ouellet, L Coulombe, C Côté et L Bélanger (1995) Le partenariat de recherche. Éléments de définition et ancrage dans quelques études de cas. Service social 44 (2) : 147-64. https://doi.org/10.7202/706697ar.

Corrivault-Gascon, A, F Gagnon (2023) Let’s have a yarn! An illustrated narrative to reveal and imagine Kitiganik. Projet de fin d’études en design urbain, École d’archi-

tecture, Université Laval, Québec. Disponible à : https:// aa24f80f-8b99-4378-b0e9-b8399fdb9ea6.filesusr.com/ ugd/2475f9_7666a38a4b7d48ff960b7f47711d9e1a. pdf

Demeule, P-O (2020) Savoir-faire locaux et auto-construction dans la toundra. Une lecture des cabanes du fjord de Salluit (Note de recherche). Études Inuit Studies 44 (1-2) : 109-59.

Després, C, N Blais, S Avellan (2004) Collaborative planning for retrofitting suburbs: transdisciplinarity and intersubjectivity in action. Futures 36 : 471-486. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.004

Dumais, L (2011) La recherche partenariale au Québec : tendances et tensions au sein de l’université. SociologieS, 20.

Gentelet, K (2009) Les conditions d’une collaboration éthique entre chercheurs autochtones et non autochtones. Cahiers de recherche sociologique 48 :143. https://doi.org/10.7202/039770ar.

Gentelet, K, S Basile, N Gros-Louis McHugh, N (dir.) (2018) Boîte à outils des principes de la recherche en contexte autochtone, 2e édition, 90-96. Réseau DIALOG, UQO, UQAT et CSSSPNQL. Disponible à : https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4339592

Gillet, A, D-G Tremblay (2017) Les recherches partenariales et collaboratives. Québec : Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Gouin, E (2024) Recherche partenariale en aménagement et architecture avec une communauté innue : Conditions d’un partenariat authentique. Thèse de doctorat en architecture, Université Laval, Québec.

Gouin, E (2021) Research Partnerships in Planning and Architecture in Indigenous Contexts: Theoretical Premises for a Necessary Evaluation. Journal of Community Practice, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2021. 1938769.

Gouin, E (2023) L’agrandissement de la communauté Uashat mak Mani-utenam : regard sur une collaboration dans la durée entre une université et une communauté innue. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien 67 (3), 442-455. https://doi.org/10.1111/ cag.12823

Habiter le Nord québécois (2016) Innuassia-um : Aménager les communautés Innues. Guide en ligne. Groupe Habitats + Cultures, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, Québec. Disponible à : www.innuassia-um.org/

Habiter le Nord québécois (2019) Imaginer: Le Nord en 50 projets. Création, collaboration, action. Vol. 2. Groupe Habitats + Cultures, École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, Québec. Disponible à : https://issuu.com/hlnq. linq/docs/imaginer-imagining

Habiter le Nord québécois (2023) Habiter ici : Portrait de cinq communautés Anishnaabeg. Vol. 3. Groupe Habitats + Cultures, École d’architecture de l’Université La-

val, Québec. Disponible à : https://issuu.com/hlnq.linq/ docs/habiter-ici_living-here_anishinaabe

Hatfield, SC, E Marino, KP Whyte, KD Dello, PW Mote (2018) Indian time: time, seasonality, and culture in Traditional Ecological Knowledge of climate change. Ecological Processes 7 (25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717018-0136-6

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas – IPCA (s.d.) Beyond Conservation : A Toolkit for Respectful Collaboration with Indigenous Peoples. https://ipcaknowledgebasket.ca/beyond-conservation-a-toolkit-for-respectful-collaboration-with-indigenous-people/

Jojola, T S (2013) Indigenous Planning : Towards a Seven Generations Model, dans Natcher, D C, R C Walker, T S Jojola (dir.) Reclaiming Indigenous planning. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kimmerer, R W (2015 [2021]) Tresser les herbes sacrés: Sagesse ancestrale, science et enseignements des plantes. Montréal: Hachette.

Koster, R, et al (2012) Moving from research ON, to research WITH and FOR Indigenous communities: A critical reflection on community-based participatory research. Canadian Geographies, 56 (2): 195-210 https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00428.x

Lévesque, G (2017) Habitations autochtones à Kitcisakik : projet de rénovation, de transfert de connaissances et valorisation des compétences locales, 2008-2020. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 47 (1), 173-181. https://doi.org/10.7202/1042909ar

Lynch, K (1960) The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mouvement pour une frugalité heureuse et créative (2022) Commune frugale. Actes Sud. En ligne : www. frugalite.org

Nursey-Bray, M, R Palmer, A M Chischilly, P Rist, L Yin (2022) Indigenous Adaptation – Not Passive Victims (chapitre 3), dans Old Ways for New Days. Springer Briefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-030-97826-6_3

Ortiz, C (2022) Storytelling otherwise: Decolonizing storytelling in planning. Planning Theory, 22 (2), 177 200. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221115875

Paquin, L-C et C Noury (2018) Définir la recherche-création ou cartographier ses pratiques? Acfas Magazine, 14 février, sect. Enjeux de la recherche-création. https://www.acfas.ca/publications/magazine/2018/02/ definir-recherche-creation-cartographier-ses-pratiques#footnote10_beph519.

Pasternak, S (2017) Grounded authority : the Algonquins of Barriere Lake against the state. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sandercock, L (2003) Out of the Closet : The Importance of Stories and Storytelling in Planning Practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(1), 11 28. https://doi.

org/10.1080/1464935032000057209

Sanderson, E et S Kindon (2004) Progress in participatory development: opening up the possibility of knowledge through progressive participation. Progress in Development Studies 4 (2), 114-126. https://doi. org/10.1191/1464993404ps080oa.

Schön, D (1984) The reflexive practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Simpson, L B (2014) Land as pedagogy: Niagnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (3): 1-25. Disponible à : https://whereareyouquetzalcoatl.com/mesofigurineproject/EthnicAndIndigenousStudiesArticles/Simpson2014.pdf

Sioui, C et S Guimont Marceau (2023) Le design participatif : un outil pour visibiliser les récits autochtones dans le paysage urbain. Urbanité, Revue de l’Ordre des urbanistes. Disponible à : https://issuu.com/hlnq.linq/docs/ urbanite-anishinaabe-2023

Vachon, G, E Gouin, S Boudreault (2023) La réconciliation dans l’action : construire un cadre collaboratif d’aménagement avec une communauté anishinaabe, numéro thématique Adopter une vision renouvelée du territoire, Urbanité, Revue de l’ordre de urbanistes du Québec. Printemps/été 2023, 26-29. Disponible à : https://issuu. com/hlnq.linq/docs/urbanite-anishinaabe-2023

Vachon, G, F Gagnon, E Gouin, S Boudreault (2024, sous presse) La relationalité au cœur des enjeux climatiques et d’aménagement culturellement approprié en territoire autochtones. État des recherches au Québec : Villes, actions climatiques, inégalités Phase 2. Réseau Villes Régions Monde (VRM) et Chaire de recherche du Canada en action climatique urbaine.

Viswanathan, L (2019) Planning with empathy. Ballado 360 degree city, 10 juin. Disponible à: https://360degree.city/2019/06/10/planning-with-empathy/ Wagamese, R (2014) Medecine Walk. NY: McClelland & Stewart

Williams-Jones, B, F-J Lapointe et P Gauthier (2018) La conduite responsable en recherche-création : Outiller de façon créative pour répondre aux enjeux d’une pratique en effervescence. Rapport de recherche : Programme Actions concertées, Fonds de recherche Société et culture 2017-IE-202480. La conduite responsable en recherche : mieux comprendre pour mieux agir. Université de Montréal. https://frq.gouv.qc.ca/app/ uploads/2021/05/ie_rapport_williams-jones-bryn.pdf. Wilson, S (2008) Research is Ceremony. Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point : Fernwood Pub.

References and Links

Principle 1 | Land and community

School on Nitassinan Land, Uashat mak Mani-utenam, QC

Architecture sans frontières and Université Laval, 2022 https://www.asf-quebec.org/portfolio-items/ ecole-dans-lenitassinan

Principle 2 | Landscape

Squamish Adventure Centre, Squamish, BC

Iredale Architecture + Dennis Maguire Architect, 2006 Iredale Architecture, 2005. https://iredale.ca/project/ squamish-adventure-centre/

Principle 3 | Anchoring

Gloucester Services, Gloucester, Royaume-Uni

Glenn Howells Architects, 2014

Hohenadel, K. (2016). One of the Most Celebrated Buildings in the U.K. Is a Highway Rest Stop, Slate https:// slate.com/human-interest/2016/06/highway-rest-stopgloucester-services-was-voted-one-of-the-u-k-s-bestbuildings.html

Principle 4 | Forest

Totest Aleng Indigenous Learning Centre, Surrey, BC O4 architecture, 2022

City of Surrey (n.d.) Totest Aleng: Indigenous Learning House. https://www.surrey.ca/arts-culture/ totest-aleng-indigenous-learning-house

Principle 5 | Water Service Area, Baie de Somme, Sailly-Flibeaucourt, France

Bruno Mader architecte, 1999

Joffroy, P. (1998). Architecture en baie de la Somme : approche territoriale, Le Moniteur https://www.lemoniteur.fr/article/architecture-aire-en-baie-de-somme-approche-territoriale.274474

Principle 6 | Soil

Saugeen Creator’s Garden and Amphitheater, Southampton, ON

Brook McIlroy Inc., 2021 Brook McIlroy. (2022). Saugeen Creator’s Garden and

Amphitheatre Master Plan. Allenford, Ontario, Canada. https://brookmcilroy.com/projects/spirit-garden/

Principle 7 | Flexibility

Hoop Dance Gathering Place, Hamilton, ON Brook McIlroy Inc., 2016

Castro, F (2018) HOOP Dance Gathering Place / Brook McIlroy. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/907647/ hoop-dance-gathering-place-brook-mcilroy

Principle 8 | Diversity

Marché Bonichoix and Community Centre, Lac-Simon, QC

ARTCAD Architectes, 2014

Lac-Simon dispose maintenant d’une épicerie. Radio-Canada, 2014. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/ nouvelle/675650/inauguration-centre-multifonctionnel-lac-simon

Principle 9 | Feasability

House Renovations in Kitcisakik, QC

Guillaume Lévesque + ASF, Québec, 2009-2015

Lévesque, G. (2008 à 2020). Kitcisakik Project. Kitcisakik, Québec, Canada. https://guillaumelevesque.com/en/ projets/projet-kitcisakik/

Principle 10 | Markers

Institut culturel cri d’Oujé-Bougoumou, Eeyou-Istchee, QC

Douglas Cardinal, 1989

St-Laurent, F. (2002). Douglas J Cardinal: La nature mise en forme, Continuité (92). https://www. erudit.org/fr/revues/continuite/2002-n92-continuite1054634/16111ac.pdf

Principle 11 | Figures et symbols

Canadian High Arctic Research Institute, Cambridge Bay, Nunavut

EVOQ architecture + NFOE architecture, 2019

EVOQ Architecture. (2019). Station Canadienne de recherche dans l’Extrême Arctique. Ikaluktutiak, Nunavut, Canada. https://evoqarchitecture.com/fr/projects/ station-canadienne-de-recherche-dans-lextreme-arctique-screa

Principle 12 | Materials

Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, Vancouver, BC

Formline Architecture, 2018

Ott, C. (2021). Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre / Formline Architecture + Urbanism. ArchDaily https://www.archdaily. com/974122/indian-residential-school-history-and-dialogue-centre-formline-architecture-plus-urbanism

www.habiterlenordquebecois.org • @hlnq.linq