14 KEYWORDS: Rembrandt, classics, Lucretia, Callisto, art history DOI: https://doi.org/10.4079/2578-9201.1(2022).07

Rembrandt: Seeking Closure in Classical Narratives PARKER BLACKWELL ARCHAEOLOGY & CLASSICAL and ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN STUDIES, CCAS ‘23, pblackwell33@gwu.edu

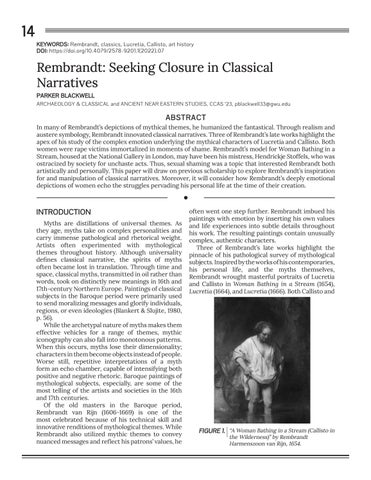

ABSTRACT In many of Rembrandt’s depictions of mythical themes, he humanized the fantastical. Through realism and austere symbology, Rembrandt innovated classical narratives. Three of Rembrandt’s late works highlight the apex of his study of the complex emotion underlying the mythical characters of Lucretia and Callisto. Both women were rape victims immortalized in moments of shame. Rembrandt’s model for Woman Bathing in a Stream, housed at the National Gallery in London, may have been his mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, who was ostracized by society for unchaste acts. Thus, sexual shaming was a topic that interested Rembrandt both artistically and personally. This paper will draw on previous scholarship to explore Rembrandt’s inspiration for and manipulation of classical narratives. Moreover, it will consider how Rembrandt’s deeply emotional depictions of women echo the struggles pervading his personal life at the time of their creation.

•

INTRODUCTION Myths are distillations of universal themes. As they age, myths take on complex personalities and carry immense pathological and rhetorical weight. Artists often experimented with mythological themes throughout history. Although universality defines classical narrative, the spirits of myths often became lost in translation. Through time and space, classical myths, transmitted in oil rather than words, took on distinctly new meanings in 16th and 17th-century Northern Europe. Paintings of classical subjects in the Baroque period were primarily used to send moralizing messages and glorify individuals, regions, or even ideologies (Blankert & Slujite, 1980, p. 56). While the archetypal nature of myths makes them effective vehicles for a range of themes, mythic iconography can also fall into monotonous patterns. When this occurs, myths lose their dimensionality; characters in them become objects instead of people. Worse still, repetitive interpretations of a myth form an echo chamber, capable of intensifying both positive and negative rhetoric. Baroque paintings of mythological subjects, especially, are some of the most telling of the artists and societies in the 16th and 17th centuries. Of the old masters in the Baroque period, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) is one of the most celebrated because of his technical skill and innovative renditions of mythological themes. While Rembrandt also utilized mythic themes to convey nuanced messages and reflect his patrons’ values, he

often went one step further. Rembrandt imbued his paintings with emotion by inserting his own values and life experiences into subtle details throughout his work. The resulting paintings contain unusually complex, authentic characters. Three of Rembrandt’s late works highlight the pinnacle of his pathological survey of mythological subjects. Inspired by the works of his contemporaries, his personal life, and the myths themselves, Rembrandt wrought masterful portraits of Lucretia and Callisto in Woman Bathing in a Stream (1654), Lucretia (1664), and Lucretia (1666). Both Callisto and

FIGURE 1. “A Woman Bathing in a Stream (Callisto in the Wilderness)” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1654.