49 minute read

Right-Wing Populism in the United States: The Intersection of Conspiracy Theories and Mainstream Political Thought

KEYWORDS: populism, conspiracy theories, 2020 election, COVID-19 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4079/2578-9201.1(2022).02

SARAH CORSO

Advertisement

INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS & FRENCH, ESIA ‘21, sarahcorso129@gwu.edu

ABSTRACT

On January 6, 2021, conspiracy theories surrounding the 2020 election and the COVID-19 pandemic culminated in the storming of the U.S. Capitol Building by right-wing insurrectionists. This paper examined the aftermath of those attacks by exploring the correlation between right-wing, national politicians’ rhetoric and the beliefs of individuals from Altoona, Pennsylvania, a small town in the Rust Belt of the United States. To study these phenomena, this paper used a two-pronged methodology of first qualitative social media research of tweets posted by Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Mitch McConnell, and Lindsey Graham, and second a quantitative survey of beliefs of residents of Altoona. The sampled tweets from the weeks before, during, and after the 2020 election, as well as the week of January 6, 2021, revealed trends in the propagation of conspiracy theories around the election and the pandemic, especially in tweets written by populists Trump and Greene. These tweets correlated the propagation of conspiracy theories in tweets and whether these four right-wing politicians were identified as populists. Furthermore, the survey yielded polarizing results that contribute to the current literature about a subset of populist followers who are highly educated and present low levels of trust in the government. Overall, this paper attempts to identify trends in beliefs among one ardent Republican base, and in right-wing populist politicians’ rhetoric, that correlate to a continued intersection of conspiracy theories and mainstream political thought in the United States.

INTRODUCTION

When right-wing militants and election deniers stormed the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, the American public and the world were shocked into a new awareness of a strange underbelly of political thought in our current age of misinformation. Encouraged by various government officials’ and politicians’ lackluster denials—or outright encouragements—of the existence of fraud in the United States’ 2020 presidential election, right-wing extremists in the U.S. attempted to take the seat of American democracy by force. Many of these people attended the “Save America” rally earlier that day, where former president Donald Trump remarked that protestors should go to the Capitol and “make [their] voices heard” (Naylor, 2021). So deeply do many of these individuals believe that they are not at fault for the events of January 6, that some claim they were not part of the assault on the Capitol building at all. Instead, right-wing pundits have proposed that “Antifa,” the ever-nebulous far leftwing faction, allegedly had undercover members acting as fascists in the rally’s crowds (Grynbaum, Alba, & Epstein, 2021).

The conspiracy theories whirling around the results of the 2020 election were not the only ones being propagated by individuals in power. Amidst the coronavirus pandemic, the reliability of vaccines has been called into question by former president Donald Trump (Stolberg, 2021), as well as by popular conservative news media personalities such as Tucker Carlson (McCarthy, 2021). As vaccines have become more widely available in the United States, vaccine skepticism continues to cast doubt upon the ability of the American public to effectively combat the virus and its variants (Russonello, 2021). The suggestion that vaccines are ineffective has transformed a public health emergency into a political debate. By using these conspiracy theories and doubts about vaccination to rally the more fervently anti-government members of their voting base, both the Republican Party and former President Trump have successfully established a foundation within the conservative wing of American politics for mistrust of the government. With conspiracy theories about the 2020 election and the pandemic in mind, this paper analyzes the question: How is the

rise of conspiracy theories in right-wing populism in the U.S. correlated to their implementation in mainstream politics? This research examines the correlation between populist rhetoric at the highest levels of American politics and conspiratorial thinking within a given population through a mixed methodology of qualitative analysis of tweets by four politicians and quantitative analysis of beliefs of a small city in Pennsylvania. LITERATURE REVIEW

Populism, particularly when employed by conservatives, can be conducive to inspiring conspiratorial thinking in its voting base (Sawyer, 2021; Casarões & Magalhães, 2021, p. 207; Stecula & Pickup, 2021, p. 2). Most recently, American conservative voters’ belief in conspiracy theories has been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic and the Republican loss of the presidential election in 2020. Contemporary ideas about the correlation between populism and conspiracy theories stem from Richard Hofstadter’s (1979) foundational essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Due to the similarities in the fundamentals of populism and belief in conspiracy theories, conspiratorial thinking often follows and intersects with populism. This literature review will also examine the scholarship about conspiracy theories in general, with particular focus on theories regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 election.

Populism in the American Right Wing

Right-wing populism in the United States is a variation on what historian Richard Hofstadter (1979, p. 3) calls “the paranoid style” of American politics, “because no other word adequately evokes the qualities of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.” Hofstadter’s description of the paranoid style serves well as a list of characteristics common to the populist right. The government, as an institution, is overlarge and sprawling and must therefore be contained, usually by centralization of authority in a populist politician who speaks for “the people.” Those individuals who control the government at the top constantly betray American national interests (p. 25). Lastly, American civil society, operating especially in the educational, religious, and media spheres, attempts to undermine “real” Americans (p. 26). As Grant (2019) notes, populism has frequently emerged in the United States during periods of uncertainty (p. 478). After the election of Donald Trump to the presidency, populism continued to grow during his time in office, especially in response to the uncertainty caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Populism often offers simple solutions to complex problems, and the pandemic’s extreme complexity did not stop Trump from trying his hand at a populist’s answer early in the pandemic (Casarões & Magalhães, 2021, p. 207). Populist Rhetoric

Common themes in populist rhetoric reflect the major characteristics of its general ideology. One of the most frequently emphasized elements of populist rhetoric in the literature is anti-elite sentiment, wherein elites are distrusted as “corrupt” and contemptuous (Sawyer, 2021). In populist rhetoric, it is not uncommon to hear accusations that members of the elite have betrayed the people, although it is never specified who “the people” are (Grant, 2019, p. 477). While both right- and left-wing populism villainize the elite, conservative populists also distrust experts (Stecula & Pickup, 2021, p. 2). This supplementary, anti-intellectual dimension of American populism deems experts as “elites” in terms of knowledge; therefore, any “elite” status in a field of study paradoxically discredits experts in the eyes of populist voters (Casarões & Magalhães, 2021, p. 197). Individuals are instead encouraged to either do their own research, or the populist right creates its own version of science as an alternative to experts’ opinions (Walther & McCoy, 2021, p. 113), which reinforces both Stecula and Pickup (2021) and Casarões and Magalhães (2021)’s claims that experts are highly distrusted by conservative populists. This facet of populist rhetoric played an essential, detrimental role in the scattered U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic under former President Trump, who frequently contradicted the experts that comprised his own coronavirus task force (Stecula & Pickup, 2021, p. 2). Taking a cue from the recent works of Stecula and Pickup (2021), Walther and McCoy (2021), and Casarões and Magalhães (2021), my research contributes to this conversation by examining how populist distrust of the elite can be interpreted in the context of increased levels of doubt about stances taken by the U.S. government, whether they are about the validity of the 2020 election, the safety of COVID-19 vaccines, or the identity of individuals who stormed the Capitol on January 6.

Hofstadter (1979)’s paranoid-style politician and the contemporary American populist view the United States’ current political situation as utterly catastrophic (p. 29). As Hofstadter (1979) describes, “what is at stake [in American politics] is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil,” (p. 31), known in philosophical terms as the Manichaean dichotomy. With the corrupt elite and their supporters on the side of absolute evil and “the people” on the side of absolute good, this divide serves to further polarize populists by framing compromise as a battle lost in favor of the evil elite (Sawyer, 2021). The divisive nature of Manichaeism is a common aspect of populist rhetoric, especially because it refutes all forms of disagreement and discourages deviation from the official party line (Basit, 2021, p. 6).

Another frequent target of populist scorn in rhetoric is mass, mainstream media. Viewed as biased and “fake,” mainstream media is often disdained because it acts as

a traditional intermediary between a populist leader and “the people.” The preference in modern populist politics to use social media to speak directly to the people constantly engages the leader’s base and reinforces the idea of the populist politician’s direct connection to their supporters. Furthermore, without mainstream media’s interceding role and with the populist base’s deepening distrust of any media that disagrees with their leader, the general public in populism’s thrall is more vulnerable to believing or considering conspiracies (Sawyer, 2021). Basit (2021) adds to this assessment that conspiratorial thinking, in turn, serves as a “multiplier” of the radicalization of individuals (p. 4).

Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories (CT) are often intertwined with and correlated to populist politics due to the tendency of CT to implicate an insidious elite and to distrust experts (Stecula & Pickup, 2021, p. 1). One common definition of a conspiracy theory in the literature is “an effort to explain some event or practice by reference to the machinations of powerful people, who attempt to conceal their role” (Miller, Saunders, & Farhart, 2016, p. 825). These authors state that, from the psychological perspective, belief in CT “satisfies the epistemic needs for order, certainty, and control,” and “is correlated with authoritarianism [and] feelings of alienation” (p. 825). In the current age of fake news and alternative facts, Basit (2021) posits that CT are common in the rhetoric and propaganda of violent extremists who hope to lure populists, particularly Trump supporters, to their cause through the use of politicized CT, emphasizing government mistrust as well as a Manichaean perspective (pp. 1-3). While this point of view had very visible implications on January 6, whether conspiratorial thinking and government mistrust are linked to violent extremism is beyond the scope of my research.

In the literature, one area of discussion is the profile of the most likely individual to believe political CT. In a policy brief for the Institute for European Studies, Rios (2020) claims that people “who are the most susceptible to conspiracy theories include those with a basic level of education […] who are socially marginalized or isolated, who feel unsure about their job security…[and] those with low income levels” (p. 3). However, Miller, Saunders, and Farhart (2016) contest this view by finding that “a particular type of person—one who is both highly knowledgeable about politics and lacking in trust— […] is most susceptible to ideologically motivated conspiracy endorsement” (p. 824). According to them, conservative people who know more about politics, rather than those with a basic or low level of education, are more likely to believe in CT that align with their political biases (p. 834). The political slant of the CT is important for the rightwing populists who believe them because it aligns with their Manichaean “us vs. them” perspective. I believe that the two profiles of populist followers can and should exist simultaneously, but studies like the one by Miller, Saunders, and Farhart (2016) are much less frequent in the literature and thus should be explored to a greater degree. The conspiracy theories that this paper studies relate to the coronavirus and the 2020 election. The population that I surveyed aligns more closely with the highly educated populist follower than Rios’ (2016) profile.

Coronavirus Pandemic Conspiracy Theories

Scholarship about the coronavirus pandemic and the various conspiracies that surround it is somewhat scarce because, at the time this paper is written, the pandemic continues to evolve. Additionally, there is a considerable lack of literature regarding conspiracy theories that make claims about vaccine inefficacy; instead, the CT that have been studied thus far concern either the coronavirus’ origins or the vaccines as a ploy to microchip the population. However, former President Trump’s pandemic response is a subject of study that epitomizes the relationship between populist rhetoric and a global health crisis. Furthermore, the pandemic itself has become an element of radicalization for populists as individuals have substantially increased their online presence out of necessity.

Contemporary populist rhetoric has played a major role in the framing of the pandemic in the U.S. With the advent of “bio-geopolitics” in the wake of COVID-19, disease is now a security threat to every nation (Cole & Dodds, 2021, p. 170). This has led to increased levels of “pandemic nationalism,” wherein people from virus hotspots—such as Wuhan, China, in early 2020—are met with hostile sentiments from host populations (p. 172). Although this is not singular to the United States, the Trumpist, Manichaean sentiment against foreign outsiders feeds into conspiracies about the uncertain origin of the virus, especially given geopolitical tensions between the United States and China as well as the racially tinged perspective of Trumpist populism (Stecula & Pickup, 2021, p. 4). Another CT that has circulated widely during the pandemic is the ID2020 theory, which claims that Bill Gates is capitalizing on the pandemic to implant microchips, considered by some theorists to be the biblical Mark of the Beast, in the population (Thomas & Zhang, 2020, p. 1). QAnon anti-vaccine theories also claim that public health measures are a means of population control, and vaccines and mask mandates are attempts by “liberal politicians…[who are supposedly] members of a deep state cabal of pedophiles” to violate human rights (Walther & McCoy, 2021, p. 113).

Current literature more extensively analyzes the US presidential response to the pandemic. Casarões and Magalhães (2021, p. 199) contribute the idea of medical populism, wherein legitimate science is viewed

skeptically by populists to the point where they pioneer “alternative” science that relies heavily on conspiracy theories and data. Using public health crises to boost their political standing, medical populists like Trump undermine experts as populist rhetoric demands while offering simpler solutions to extremely intricate issues, such as hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 miracle cure. Moreover, the circumstances of the pandemic are a radicalizing element because increased online presence has been imperative during periods of quarantine and lockdown, which draws individuals further into conspiratorial echo chambers on the Internet (Walther & McCoy, 2021, p. 113).

2020 Presidential Election—the Big Lie Conspiracy Theory

The belief that Donald Trump was the real winner of the 2020 election is a conspiracy theory that the former president himself touted by claiming on Twitter months before the November 2020 election that it was going to be “stolen” and “rigged” if Joe Biden won (Canon & Sherman, 2021, p. 548). One key to this CT was the role of the pandemic and its restrictions on movement during an election year. The pandemic warranted voting by mail in massive numbers; despite the absolute absence of evidence, the former president claimed the election was overrun with voter fraud, even though he himself had voted by mail in the past (p. 550). All other CT and claims about the various types of fraud in the 2020 election were systematically disproven by basic data analysis (p. 548). In addition to the utter lack of voter fraud in the 2020 election, challenges to the election by the Trump legal team and his supporters in courts were tossed out by judges for being “untimely,” “moot,” or lacking sufficient evidence (pp. 572-573). Despite clear evidence to the contrary, the Big Lie CT holds favor with many conservatives who distrust mainstream reporting and the government itself. Indeed, in the months following the events of January 6, 2021, Canon and Sherman (2021) found that 58% of polled Republicans still described the attack as “antifa-inspired” (p. 549). My research contributes to their post-January 6 assessment by asking survey respondents to rate whether they agree that the insurrection was led by Antifa or Trump supporters.

Finally, compared to the number of “bottom-up” studies of conspiracy theories, the literature does not extensively explore the effect of “top-down” communication of CT from populist leaders and paranoidstyle spokespeople to their followers. While populists and conspiracy theorists often abhor the elite, the populist leader frequently becomes or already belongs to this upper echelon while continuing to hold influence with “the people.” The espousal of CT from the “top”—in the cases of the pandemic and the 2020 election, from the President of the United States and from several members of Congress—can in turn make CT part of political elites’ rhetorical arsenal and forge connections between legitimate politicians and the conspiracy theories they either endorse or refuse to deny (Enders & Uscinski, 2020, p. 599). This paper will examine the extent to which mainstream, populist politicians in the U.S. advanced the two conspiracy theories articulated in this literature review, as well as the extent to which one population’s beliefs have been affected in the post-January 6 world. METHODOLOGY

In order to assess the correlation between the rise of right-wing, populist conspiracy theories and the proclivity of voters to believe conspiracy theories, the research was conducted using a mixed methodology. The primary research method was a survey of citizens of Altoona, a small city of less than 44,000 people in central Pennsylvania, USA, through a quantitative method of analysis. As the major city in Blair County and as part of a community in the Rust Belt, Altoona natives represent a vital core of voters for Trump’s election in 2016 (Tackett, 2019) and are the main voters in a county that voted 71% in favor of Donald Trump in the 2020 election (Summary results report: General election, 2020). This anonymous online survey was intended to reveal numerically the correlation in this community between conspiracy theories promoted by politicians and voters’ political beliefs. Data was collected through the snowball method, wherein respondents shared the survey with others in their social network. I chose this method because it allowed me to reach and survey individuals despite the limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the anonymity of the survey allowed respondents to answer questions about their political beliefs and beliefs in conspiracy theories without fear of being judged or targeted, which several authors note is a concern among conservatives (Daniller, 2021; Inbar & Lammers, 2012, p. 1; Westneat, 2021). However, some potential biases in any study using this method of data collection include sampling bias and an unrepresentative sampling; nonresponse bias; and lack of researcher control. In addition to questions about COVID-19 vaccination status, voting choices in both the 2016 and 2020 national elections, and demographical data, respondents were asked to rate how much they agreed with statements that concerned the 2020 election, COVID-19, and the U.S. government. Answers to these statements contributed significantly to my research in conspiracy theories in right-wing populism because these topics are, as the survey revealed, contemporary concerns within the population.

The secondary method of research involved qualitative analysis of tweets from traditional and populist rightwing politicians that showed which, if any, conspiracy theories regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 U.S. election were being propagated by right-wing

American politicians at the national level. Tweets by politicians Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Mitch McConnell, and Lindsey Graham were analyzed. The former two are populists, whereas the latter two are more traditional right-wing politicians. While the first three politicians are highly visible due to either their positions— at the time, President and Senate Majority Leader—or their reactionary tendencies (Nobles, 2021), Lindsey Graham stands out as a politician who, while maintaining center-right positions, has also been able to foster favor with Trump. As Thrush, Becker, and Hakim (2021) detail in their article, Graham has a singular capacity to alter his personal platform based on the direction of public opinion that is most likely to get him reelected.

Comparing these politicians’ public stances on both the pandemic and the 2020 election revealed the extent to which these politicians promoted conspiracy theories to the general public through Twitter. This stage of research was limited to four weeks’ worth of tweets: the weeks of October 25-31, 2020; November 1-7, 2020; November 8-14, 2020; and January 3-9, 2021. During the first week, another wave of coronavirus cases was just beginning to spike; the following two weeks included Election Day on November 3 and its aftermath; and the last was the week of the attack on the U.S. Capitol Building. All of the events in these four weeks were correlated to subjects that have invited conspiracy theories about the pandemic and the election. How these politicians approached the pandemic and the election contributed to my research in right-wing populism and conspiracy theories because the way that politicians address these subjects often has implications for public trust in the government, which Klein and Robison (2020) state is a clear indicator of healthy democracies (p. 47). These authors also explain that social media, which is used by the majority of U.S. adults according to Smith and Anderson (2018), is frequently linked to political polarization in the United States, with individuals being more likely to distrust the government if their peers and “friends” on social media feel similarly and share similar posts (Klein & Robison, 2020, p. 49). Overall, the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods first evaluated the correlation between populist rhetoric and the beliefs of a population of right-wing voters through the primary method of a survey. Additionally, these methods assessed the extent of the integration of conspiracy theories into right-wing, mainstream political rhetoric through the secondary method of social media E-research.

RESULTS

In order to evaluate the correlation between rightwing populist conspiracy theories and the United States’ mainstream politics, I first conducted a survey of residents of Altoona, Pennsylvania, followed by an examination of tweets by four American politicians over four weeks. From these two methods, I identified three broad themes: doubts about the 2020 election and COVID-19 vaccines; beliefs of left-wing radicalization; and mistrust in the government. I drew upon the subject matter of the survey statements in order to code the tweets. For initial coding, I identified two broad categories that are linked to the conspiracy theories of interest in this research: the 2020 election and COVID-19. Tweets regarding the 2020 election or voting (and in particular voting by mail) were coded differently from tweets regarding COVID-19 or vaccines. Not every one of the 1,808 tweets that I read was relevant to either of these subject areas; despite this, as the tables in Appendix A show, each of these four politicians tweeted about either the pandemic, the election, or both. The sample tweets in Appendix A were ones that I noted as most relevant to the study and thought best encapsulated the general tone of each politician on these issues.

In these four weeks, the four politicians tweeted from their verified Twitter accounts a total of 1,808 times. Donald Trump tweeted 998 times (Trump Twitter Archive, 2021). Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lindsey Graham, and Mitch McConnell each tweeted 548 times; 149 times, and 113, respectively (Littman, Wrubel, Kerchner, Smith, & Bonnett, 2020). All four politicians tweeted about the election, but only Trump and McConnell tweeted about COVID-19 vaccines. Greene expressed her opinions on masking protocols, whereas Graham did not tweet about COVID-19 at all in the selected four weeks.

In those four weeks, Trump tweeted explicitly about the election over 150 times, the pandemic 30 times, and leftwing radicalization over 25 times. Marjorie Taylor Greene tweeted about the election over 120 times, the pandemic 20 times, and left-wing radicalization over 50 times. The traditional politicians, McConnell and Graham, tweeted about the election a combined 30 times, and McConnell tweeted about the pandemic 16 times. The tweets from the populists contributed explicitly to the first two themes— doubts about the 2020 election and the pandemic, and beliefs of left-wing radicalization—and implicitly to the third theme of mistrust of the government.

One limitation I encountered when viewing the tweets was the fact that many of Trump’s tweets were posts without text and linked a video that had been deleted from Twitter for violating their terms of service, thus rendering it inaccessible. Additionally, the scope of my research was limited to what these politicians were directly stating in their tweets; therefore, the number of tweets that relied on links to other media discussing these topics could have been higher than what I was able to observe.

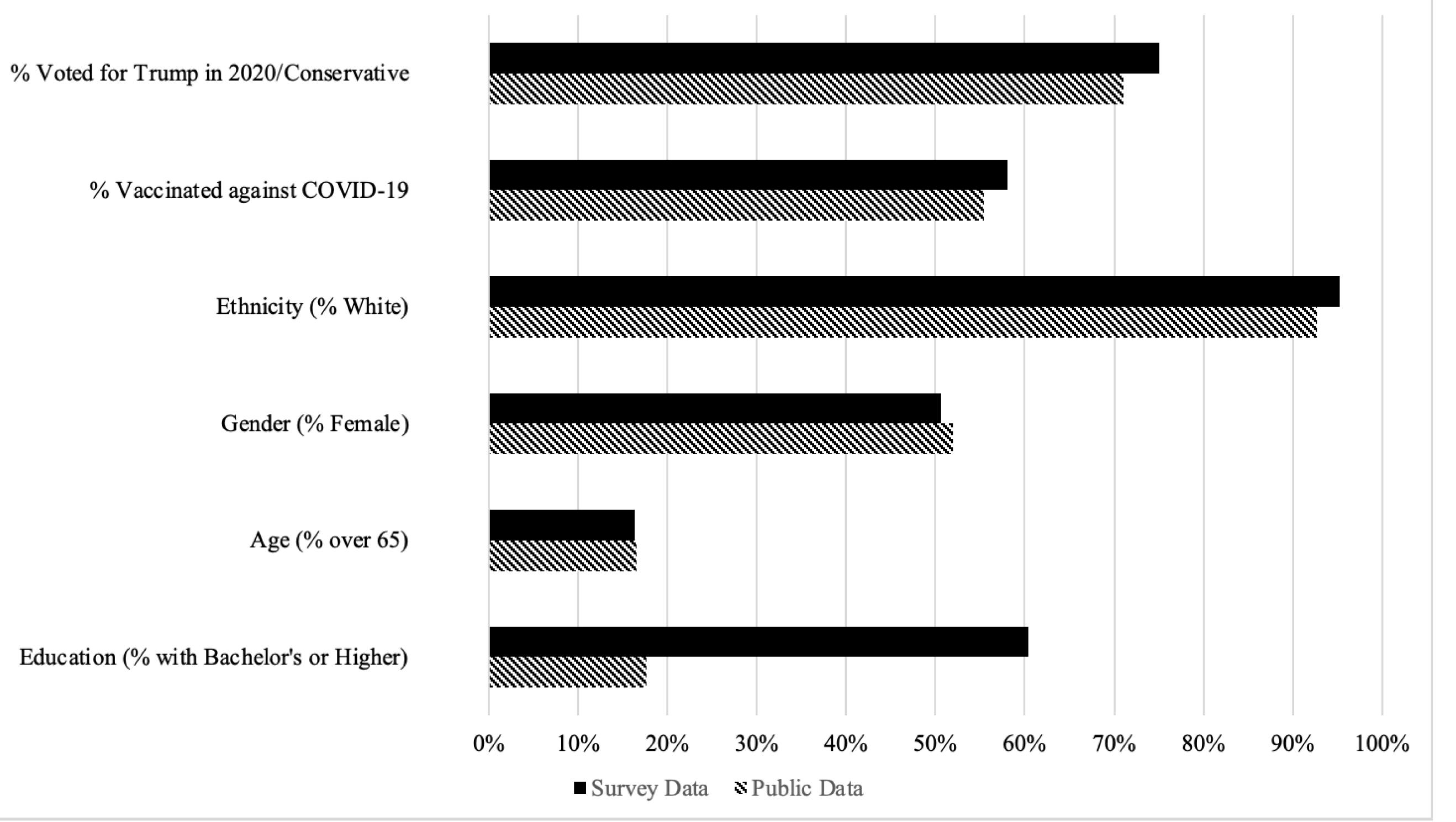

Over the three weeks that it was live, 86 residents of Altoona, Pennsylvania completed and submitted the survey anonymously. Publicly available demographic data indicates that the survey is representative of the city in

FIGURE B1.

Survey Demographics vs Public Data

every aspect except for level of education; the survey respondents were disproportionately more educated than the population of the city, as shown in Figure B1.

With the survey’s subject matter informing the categorization of the tweets, I defined three themes within the research: doubts about the 2020 election and COVID-19 vaccines, beliefs of left-wing radicalization, and an overarching sense of mistrust in the government. It is important to note differences between the tweets’ discussion of vaccines and the pandemic compared to survey responses, especially because the timings and contexts of each are different. The analyzed tweets were all posted before or amid the January 6 storming of the Capitol, whereas the survey responses were submitted several months after the events of January 6, 2021. DISCUSSION

The results from this research have implications for the intersection of right-wing populist conspiracy theories and mainstream politics in the United States. Survey data revealed clear trends toward belief in the conspiracies that this research focused on, particularly among the educated population of Altoona, PA. In addition, initial analysis of tweets by conservative politicians revealed that populist politicians—in this case, Donald Trump and Marjorie Taylor Greene—were easy to distinguish from traditional politicians due to the volume of their tweets. As the literature review stated, populists prefer to eliminate any sort of intermediary between themselves and the people. This tendency makes them much more likely to resort to social media such as Twitter to amplify their message, rather than a traditional media press conference. This was the initial marked difference between populists Trump and Greene and traditional, career politicians McConnell and Graham, who tweeted much less often. Because of their infrequency in tweeting, I operated on the assumption that if the traditional politicians tweeted about something, it was significant. In this context, contemporary CT propagated by populists about the integrity of the 2020 election and the effectiveness or safety of American COVID-19 vaccines have been correlated to beliefs about left-wing radicalization and sentiments of mistrust in the government among the surveyed population.

While the literature review showed that there are conspiracy theories about many different subject areas, this research focused on the conspiracy theories regarding the results of the 2020 U.S. election and the development of American vaccines against COVID-19. Trump and Greene tended to strongly and frequently express agreement with theories that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen” from Trump or that the results were “fraudulent.” Former president Trump tweeted about the potential for voter fraud from voting by mail before, during, and after the election, stating that mail-in ballots are the cause of “big problems and discrepancies” (see Table A1).

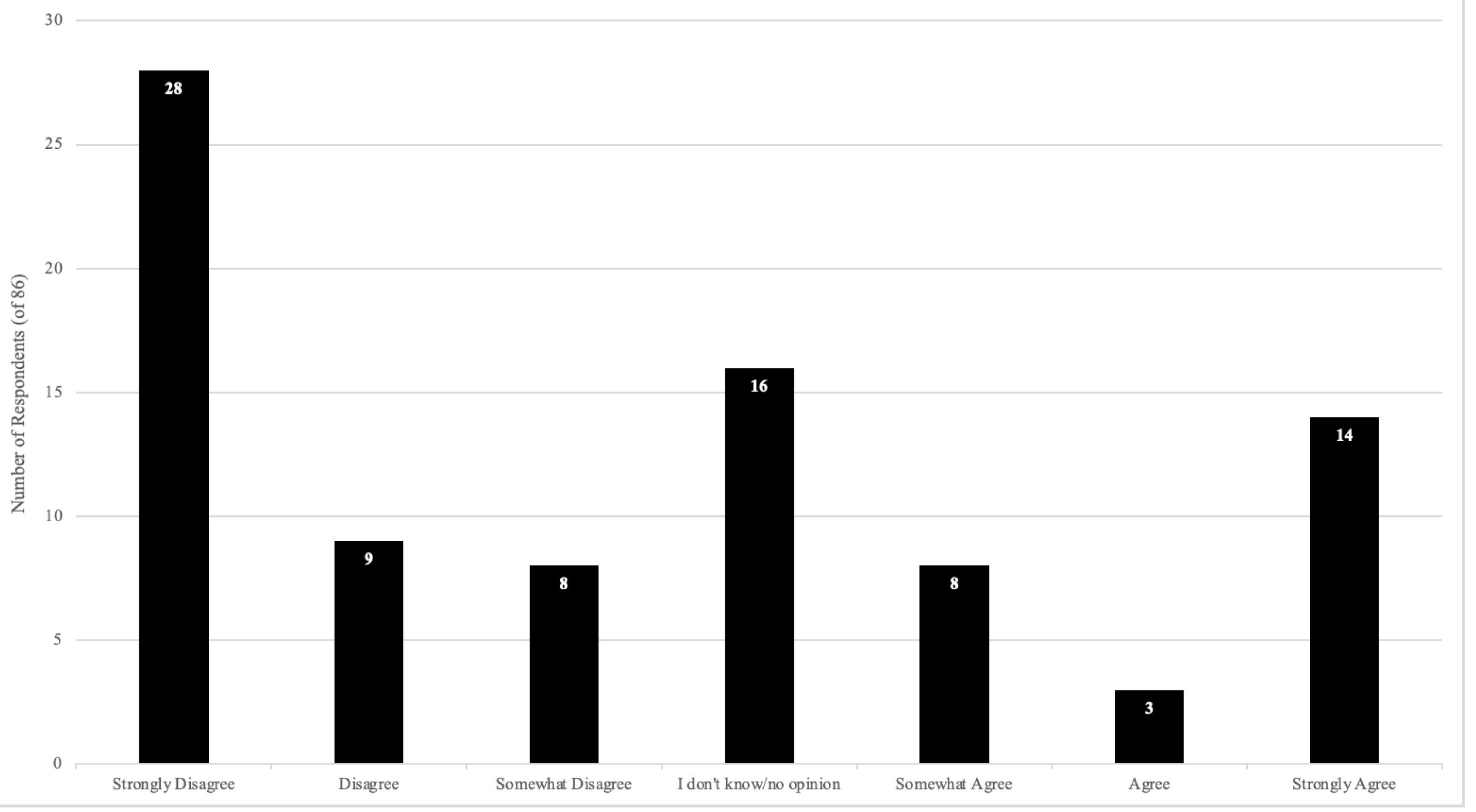

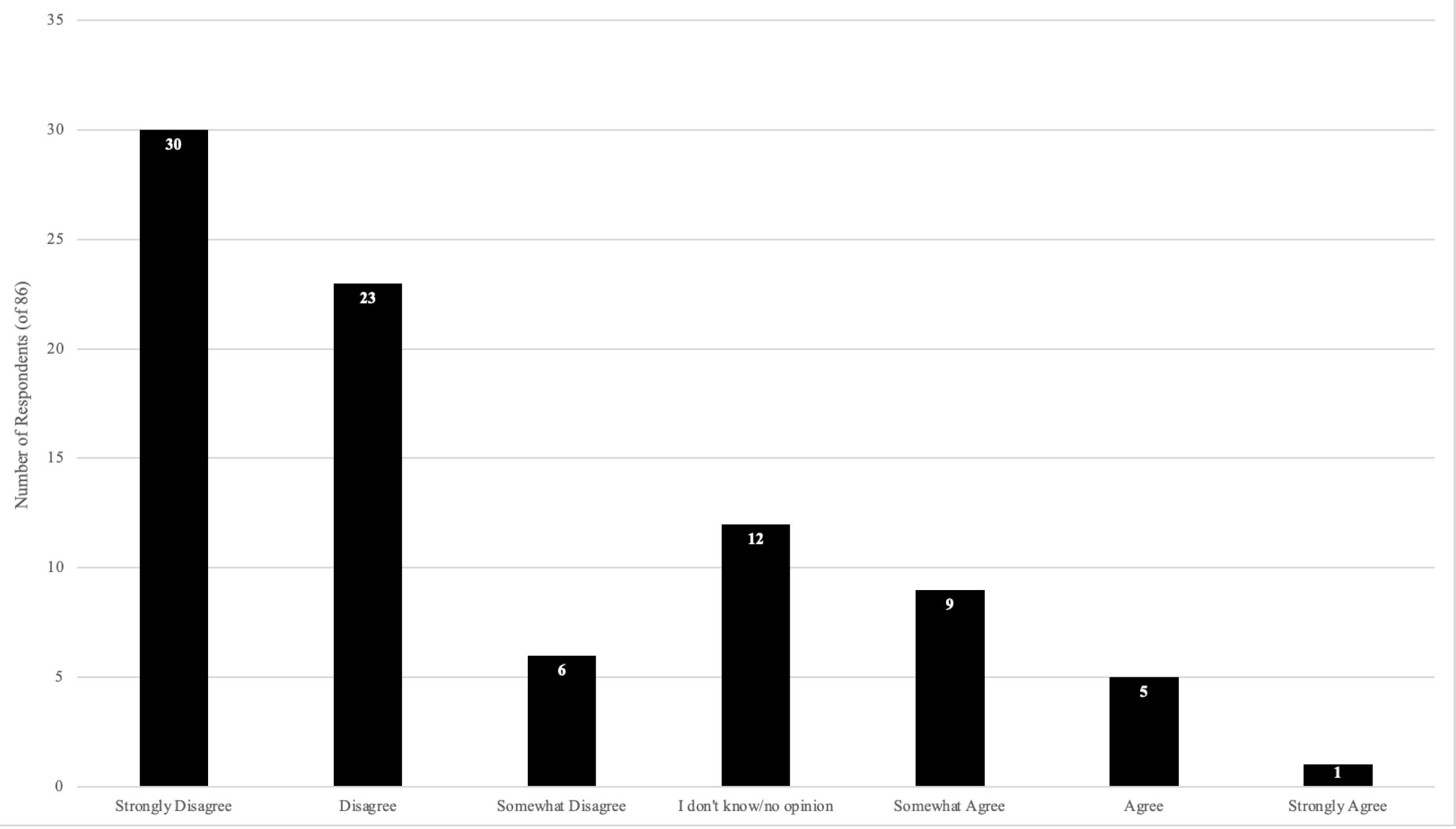

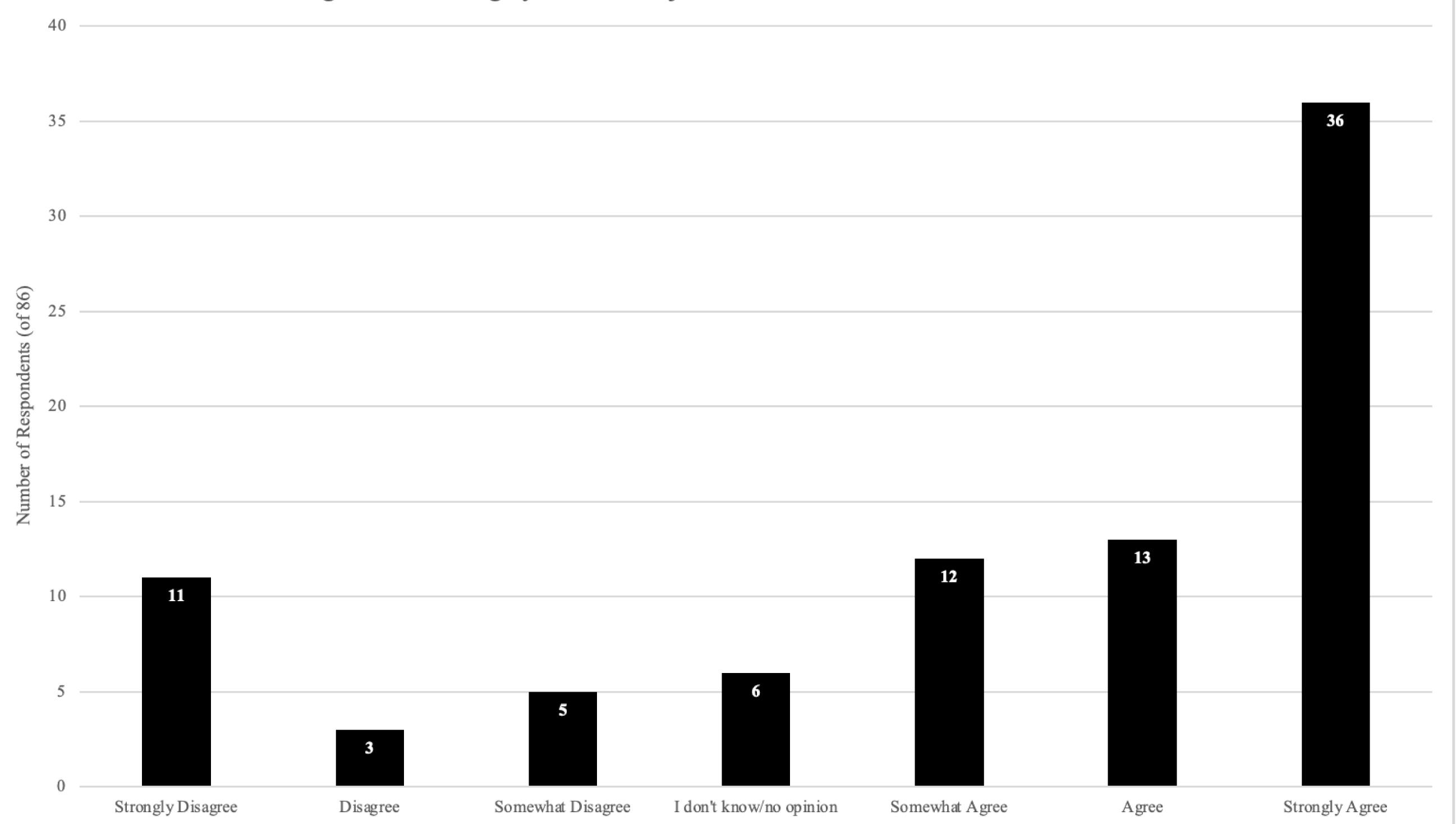

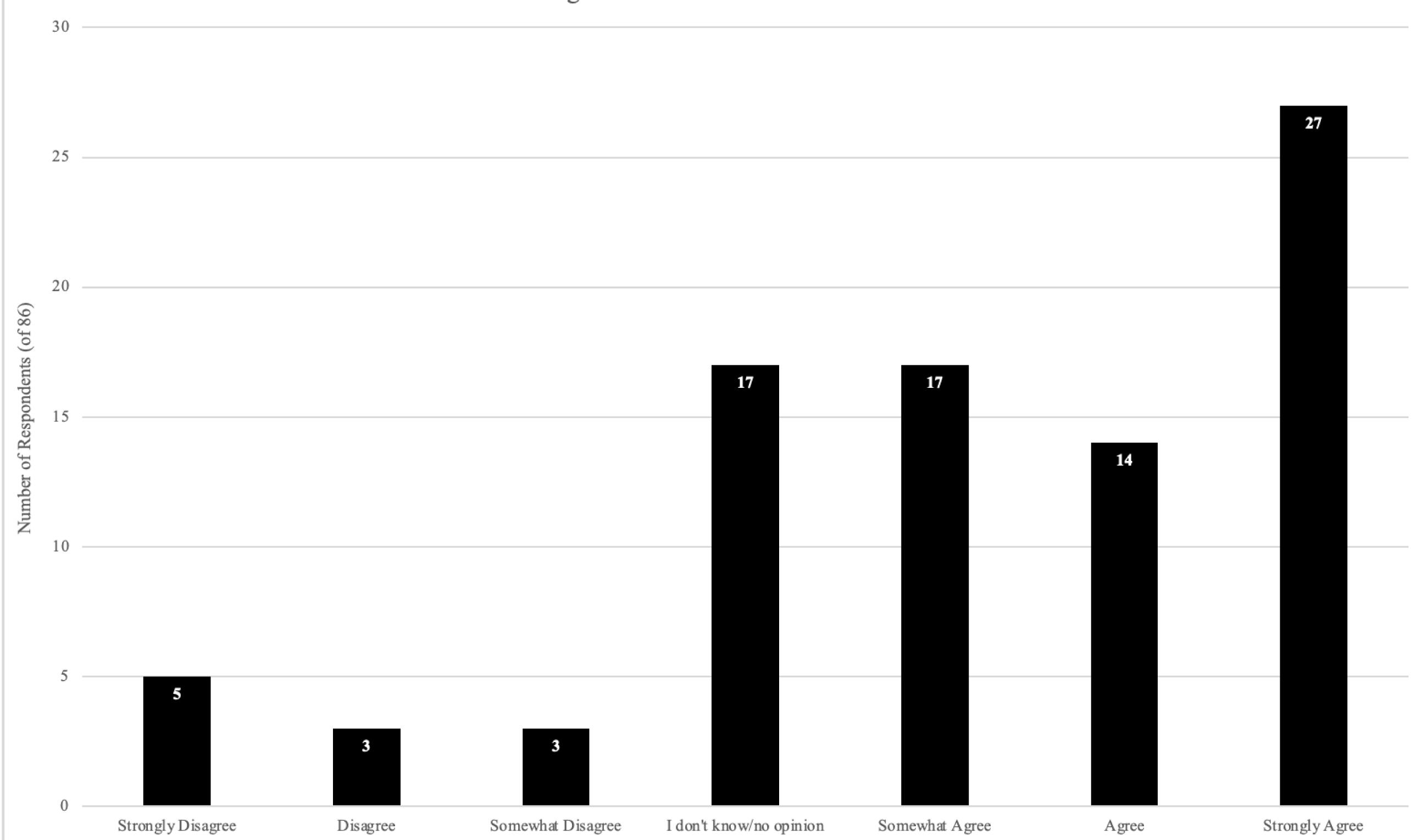

Marjorie Taylor Greene echoed these sentiments in her tweets, citing “voter fraud” and casting doubt on election integrity (see Table A3). In comparison, many survey respondents—50 of the 86 surveyed (58%)— expressed agreement that Trump won the 2020 election (see Figure B2), and 71% of them (61 respondents) agreed that voting by mail was a major cause of voter fraud (see Figure B3). There is a correlation between the percentage of respondents who identified themselves as “conservative”—75%—and that of those who believed that voting by mail caused voter fraud in the United States. These responses are correlated to frequent instances of populist rhetoric among conservative politicians advancing a conspiracy theory about the reliability of voting by mail, and it reflects previous research in the literature that conservative individuals are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

The statement regarding voting by mail produced one of the strongest reactions from respondents in the survey overall. As highlighted in the literature review, Donald Trump propagated the conspiracy theory that voting by mail was a major cause of voter fraud in the United States, despite numerous studies that presented evidence to the contrary. Additionally, other populists such as Marjorie Taylor Greene reiterated and amplified his claims on Twitter. The high level of agreement with this conspiracy theory among survey respondents is correlated with the power of populist leaders in influencing their supporters. Furthermore, the fact that Lindsey Graham and Mitch McConnell, two traditional, career politicians, opted to “listen closely to” those who were “challenging the results of [the 2020] election” has implications for right-wing populism’s impact on mainstream political rhetoric (see Table A5). Conspiracy theories supported by populists can no longer be dismissed outright by traditional politicians in order to maintain their voter base; by deigning to entertain baseless claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election, career politicians have legitimized populists and their often extreme platforms. While my research contributes mainly to scholarship about the correlation between politicians’ statements and voters’ beliefs, future studies could focus on additional directional flows of influence, including the influence of voters on politicians or the cycle wherein voters influence politicians’ stances, which influence voters’ beliefs, which in turn influence politicians’ stances, etc.

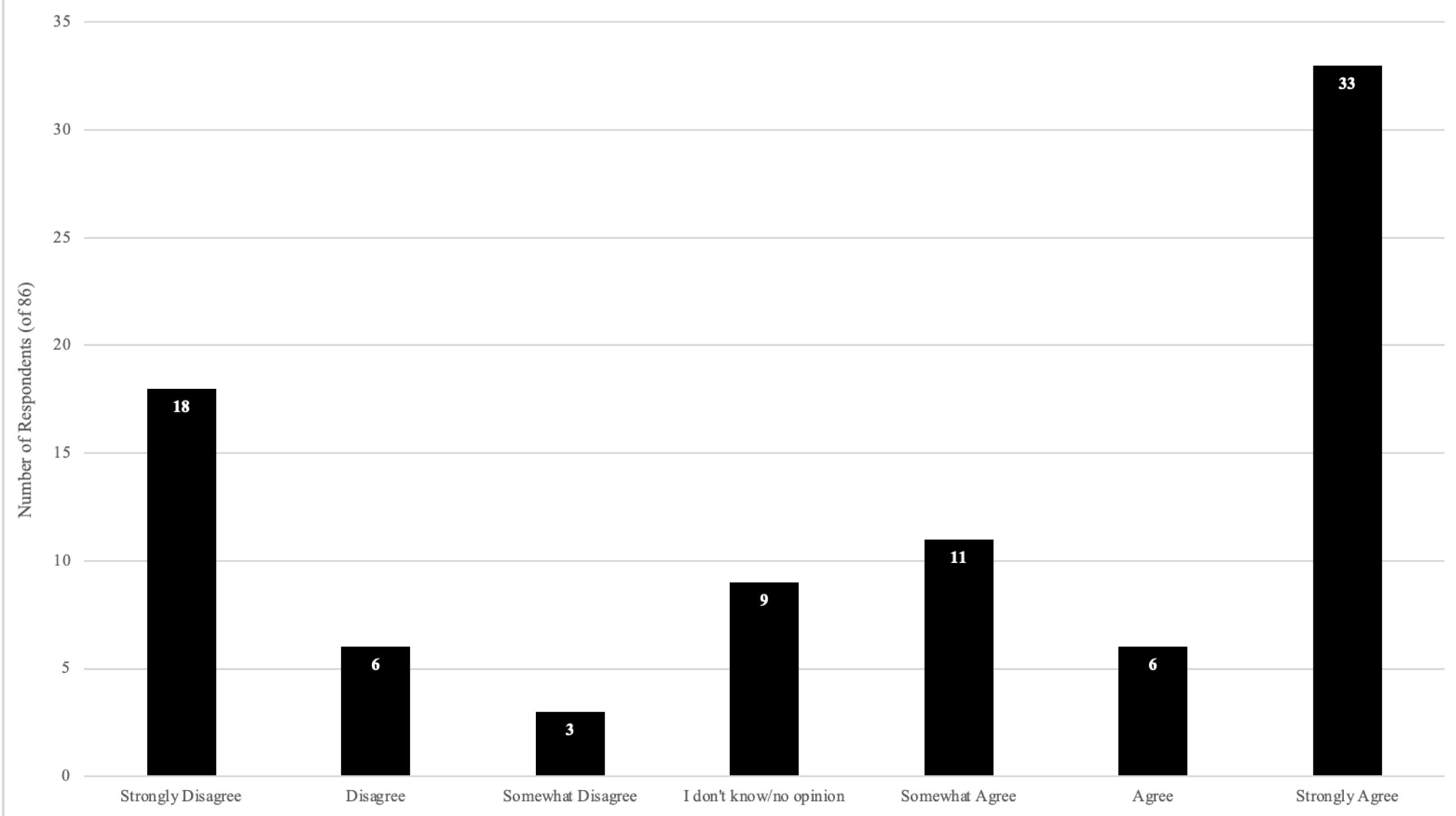

In the weeks that I examined, no tweets by any of the four politicians mentioned the vaccines in anything less than a positive manner. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lindsey Graham—a populist and a traditional politician, respectively—did not mention the vaccines at all in those four weeks. Instead, Greene expressed her distaste for masks (see Table A4), which she considered a form of oppression, whereas Graham never tweeted about COVID-19 in those weeks. Mitch McConnell and Donald Trump both tweeted optimistically about the progress on vaccines, and McConnell stated frankly that the news of a “COVID-19 vaccine was incredibly promising. All of us have to keep up commonsense [sic] precautions in the meantime. The virus is spreading quickly…and it doesn’t care whether we’ve gotten bored with wearing masks or social distancing” (see Table A6). These positive or neutral outlooks on the vaccines align with my survey results, wherein 58 respondents (67%) agreed that “vaccines save lives” (see Figure B4).

Although he tweeted frequently about the vaccine progress in the weeks that I reviewed, Trump also claimed that real or potential delays to the vaccines were—or would be—because of many different actors besides himself, including “Fake News,” Joe Biden, and the FDA. However, in the weeks that I reviewed, he did not tweet anything that would cast doubt on the vaccines’ effectiveness under his administration. In fact, days after the election, he proudly announced, “STOCK MARKET UP BIG, VACCINE COMING SOON. REPORT 90% EFFECTIVE. SUCH GREAT NEWS!” (see Table A2). This is an area where my hypothesis was not confirmed—the majority of individuals surveyed were not skeptical that vaccines save lives. This is a limitation of my methodology: By focusing on four specific weeks at key moments in 2020 and 2021, rhetoric that disparaged the vaccines could have been missed. While Trump was claiming credit for the vaccines for political leverage during the chosen weeks, his usual encouragement of mistrust in the government did not work in his favor, particularly because, even as he touted the vaccine’s effectiveness, he was more fervently pushing the “Big Lie” about the 2020 election.

Beliefs of Left-Wing Radicalization

The conspiracy theories propagated on Twitter by populist politicians often included a designated instigator, and for right-wing populists Trump and Greene, the political enemies with whom they rested blame for either questionable election integrity or vaccine delays were all liberal entities and/or had ties to the U.S. government. Donald Trump characterized the Democratic party as an organization of “Marxists, Socialists, Rioters, FlagBurners, and Left-wing Extremists,” and he stated that Joe Biden in particular was “the candidate of rioters, looters, arsonists, gun-grabbers, flag-burners, Marxists, lobbyists, and special interests” (see Table A1). Marjorie Taylor Greene echoed these sentiments in her tweets, stating that “Antifa and BLM aren’t being funded to riot anymore since they think @JoeBiden won” (see Table A3).

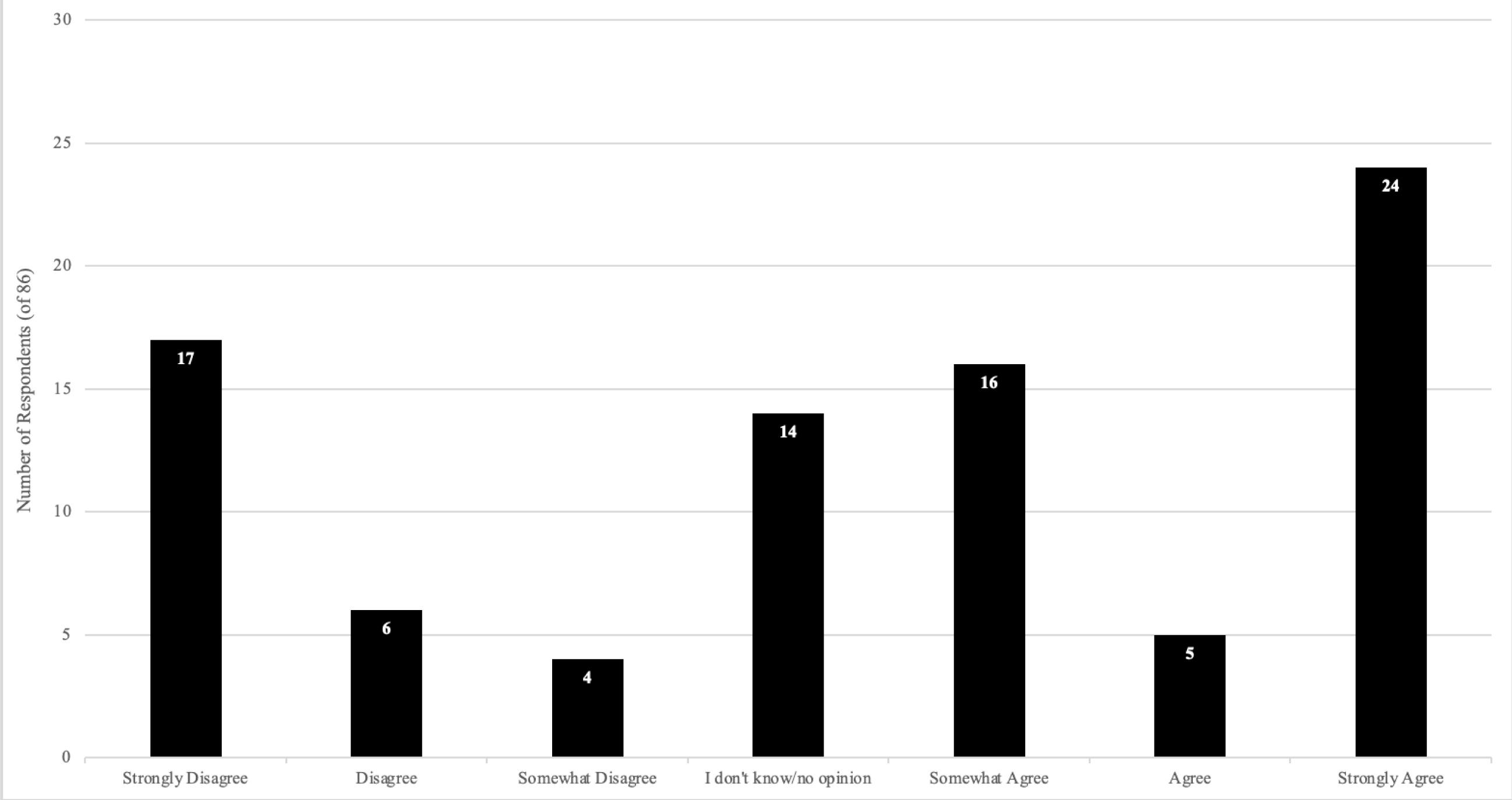

This characterization of the left-wing as increasingly radicalized had repercussions in the survey, wherein 45 respondents (52%) expressed agreement that Antifa had stormed the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, and another 14 (16.3%) were not sure or had no opinion (see Figure B5). Similarly, when asked to what extent they agreed that Trump supporters had stormed the

FIGURE B6.

“The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol Building was carried out by TRUMP SUPPORTERS and other right-wing groups.”

Capitol, 28 respondents (33%) “strongly disagreed,” with another 33 respondents (38%) either expressing some disagreement or being unsure, as shown in Figure B6.

The responses to these corresponding questions showed a correlation between the Manichaean, “us and them” populist mentality and the ease with which Trump was able to push the conspiracy theory that Antifa attacked the Capitol Building. As the literature review discussed, populist rhetoric casts the “enemy” as inherently evil. Because they know that they are not inherently evil, survey respondents were unable to see themselves or their peers in the individuals who attacked the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021. Instead, in the context of the survey, they deflected their disgust for the events that occurred at the Capitol on the nebulous group that they believe has infiltrated liberal political bodies, the government, and even, in the case of January 6, right-wing political movements: Antifa.

Mistrust in the Government

As the literature review revealed, conspiracy theories that concern the government rely upon believers’ mistrust in that institution. While Donald Trump and Marjorie Taylor Greene’s tweets casted blame upon various actors with links to the federal government, they did not directly state that the government itself was at fault for the integrity of the 2020 election or the progress of COVID-19 vaccine developments. Instead, this overarching element of belief in conspiracy theories that concern the government was witnessed in the survey. When asked to express how much they agreed with the statement, “I trust the U.S. government,” 71 respondents (83%) either disagreed with it or were unsure. Of this number, 30 respondents (35% of those surveyed) strongly disagreed with the statement, as shown in Figure B7.

These results reveal a significant plausible reason for respondents’ lack of trust in official election results and in the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines: mistrust in the government. Distrust of government is frequently correlated with populist sentiment, so this final statement of the survey also could correlate to the extent of populism’s potential reach into a local population in the Rust Belt.

The survey, while representative of Altoona, Pennsylvania’s population in most respects, had a disproportionately large number of highly educated respondents in comparison to the population of the city as a whole. The fact that the results of the survey still trended toward strong sentiments in favor of populist ideas speaks to a conflicting area of interest in the literature: the profile of the populist follower. While some contributors to the literature such as Rios (2020) claim that the average populist follower has only a basic level of education, the results of this survey lend credence to other works within the literature, such as the study by Miller, Saunders, and Farhart (2016). As they note, an individual who is likely to believe in conspiracy theories has a high level of knowledge and a low level of trust; my survey captured the views of individuals who fit

that profile. However, that is not to say that all populist followers are highly educated; both profiles of populist followers can and do coexist in the literature. Further study could be conducted into whether level of education or level of trust plays a larger role in belief in conspiracy theories and in tendency to follow populist politicians.

Another opportunity for future research could involve surveying a larger population—the survey that I conducted fell short in the measurement of education because my surveyed population was disproportionately more educated than census data shows is average of the town. Having a truly representative survey of Altoona, Pennsylvania would be worthy of further study especially because of its stance as a small city in the Rust Belt and in a swing state. Additionally, other weeks’ tweets by the same politicians could be analyzed in future research. The weeks I selected emphasized the 2020 election to a greater extent than they did the COVID-19 pandemic, so the pandemic was relegated to a correlating factor to the issues surrounding the election, rather than the subject of a series of conspiracy theories on its own. Additional studies in social media E-research could examine other weeks within the pandemic during the Trump presidency. Because the pandemic continues to evolve even as of this paper’s writing, more contemporary data in terms of public belief in pandemic-related conspiracies can be drawn from future surveys. CONCLUSION

This research paper explored the question, “How is the rise of conspiracy theories in right-wing populism in the U.S. correlated to their implementation in mainstream politics?” Through a mixed methodology of qualitative analysis of tweets by four national-level politicians and quantitative analysis of beliefs of a small city in Pennsylvania, this research has offered new perspectives on the diffusion of populist rhetoric and its correlation to conspiratorial thinking within a given population. Taking Altoona, Pennsylvania as a case study, it appears that populist beliefs and opinions espoused by party leaders impacted respondents’ beliefs in the coronavirus pandemic and Big Lie conspiracy theories. Furthermore, the tweets that were analyzed have not been explored in depth in other literature thus far, due to how recently they were posted. This paper contributes to the academic conversation by identifying social media posts from important, defining weeks in American history that future researchers can easily access for further analysis.

This paper posits that for as long as there is extensive mistrust in the government among the general public, populism will remain a strong force in American politics. When populists promote conspiracy theories about political issues, they pressure traditional politicians into legitimizing their claims by considering them in the first place. For this reason, my research will remain relevant for as long as there is a mix of traditional and populist politicians in public office. However, several important questions are unanswered that are beyond the scope of this paper: Will traditional politicians, both liberal and conservative, someday be eclipsed by their more

FIGURE B7.

“I trust in the U.S. government.”

radicalized counterparts? How well will radical politicians be received by their voting base in the future, and how far will public support stretch when their conspiracy theories inevitably break down? The events of January 6, 2021, loom large as a grim reminder of the fragility of liberal democracy in the world; more than ever, finding common ground in spite of political differences is essential to the continued health and strength of American democracy.

APPENDIX A: SAMPLING OF TWEETS

Date Tweet by @RealDonaldTrump 10/26/2020, 6:43PM

“Big problems and discrepancies with Mail In Ballots all over the USA. Must have final total on November 3rd.”

10/29/2020, 2:54PM “Your VOTE on Tuesday, November 3rd is going to SAVE OUR COUNTRY. We are going to defeat the Marxists, Socialists, Rioters, Flag-Burners, and Left-wing Extremists! Get out and VOTE! #MAGA”

11/1/2020, 5:35PM

11/2/2020, 8:02PM

11/4/2020, 5:44AM “Joe Biden is the candidate of rioters, looters, arsonists, gun-grabbers, flag-burners, Marxists, lobbyists, and special interests. I am the candidate of farmers, factory workers, police officers, and hard-working, law-abiding patriots of every race, religion and creed! #MAGA” “The Supreme Court decision on voting in Pennsylvania is a VERY dangerous one. It will allow rampant and unchecked cheating and will undermine our entire systems of laws. It will also induce violence in the streets. Something must be done!” “We are up BIG, but they are trying to STEAL the Election. We will never let them do it. Votes cannot be cast after the Poles are closed!”

11/4/2020, 10:17AM

11/5/2020, 12:21PM “How come every time they count Mail-In ballot dumps they are so devastating in their percentage and power of destruction?”

“STOP THE FRAUD!”

11/7/2020, 8:20AM

11/7/2020, 10:36AM

11/7/2020, 4:53PM

11/10/2020, 10:33PM

11/10/2020, 9:37PM “Tens of thousands of votes were illegally received after 8 P.M. on Tuesday, Election Day, totally and easily changing the results in Pennsylvania and certain other razor thin states. As a separate matter, hundreds of thousands of Votes were illegally not allowed to be OBSERVED...” “I WON THIS ELECTION, BY A LOT!”

“THE OBSERVERS WERE NOT ALLOWED INTO THE COUNTING ROOMS. I WON THE ELECTION, GOT 71,000,000 LEGAL VOTES. BAD THINGS HAPPENED WHICH OUR OBSERVERS WERE NOT ALLOWED TO SEE. NEVER HAPPENED BEFORE. MILLIONS OF MAIL-IN BALLOTS WERE SENT TO PEOPLE WHO NEVER ASKED FOR THEM!”

“WATCH FOR MASSIVE BALLOT COUNTING ABUSE AND, JUST LIKE THE EARLY VACCINE, REMEMBER I TOLD YOU SO!”

“People will not accept this Rigged Election!”

Table A1: Continued

11/13/2020, 10:59AM

1/3/2021, 1:24PM

1/6/2021, 9:15AM

1/6/2021, 6:01PM

11/7/2020, 4:53PM “For years the Dems have been preaching how unsafe and rigged our elections have been. Now they are saying what a wonderful job the Trump Administration did in making 2020 the most secure election ever. Actually this is true, except for what the Democrats did. Rigged Election!” “The Swing States did not even come close to following the dictates of their State Legislatures. These States “election laws” were made up by local judges & politicians, not by their Legislatures, & are therefore, before even getting to irregularities & fraud, UNCONSTITUTIONAL!” “The States want to redo their votes. They found out they voted on a FRAUD. Legislatures never approved. Let them do it. BE STRONG!”

“These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long. Go home with love & in peace. Remember this day forever!” “THE OBSERVERS WERE NOT ALLOWED INTO THE COUNTING ROOMS. I WON THE ELECTION, GOT 71,000,000 LEGAL VOTES. BAD THINGS HAPPENED WHICH OUR OBSERVERS WERE NOT ALLOWED TO SEE. NEVER HAPPENED BEFORE. MILLIONS OF MAIL-IN BALLOTS WERE SENT TO PEOPLE WHO NEVER ASKED FOR THEM!”

Date Tweet by @RealDonaldTrump 10/26/2020, 6:36PM

“We have made tremendous progress with the China Virus, but the Fake News refuses to talk about it this close to the Election. COVID, COVID, COVID is being used by them, in total coordination, in order to change our great early election numbers.Should be an election law violation!”

10/26/2020, 7:58AM “The Fake News Media is riding COVID, COVID, COVID, all the way to the Election. Losers!”

10/27/2020, 6:31AM “ALL THE FAKE NEWS MEDIA WANTS TO TALK ABOUT IS COVID, COVID, COVID. ON NOVEMBER 4th, YOU WON’T BE HEARING SO MUCH ABOUT IT ANYMORE. WE ARE ROUNDING THE TURN!!!”

10/30/2020, 4:47PM

11/2/2020, 4:33PM

11/9/2020, 7:31AM “This election is a choice between a Trump Super Boom or a Biden Depression, and it’s between a safe vaccine or a devastating Biden lockdown!” “Joe Biden is promising to delay the vaccine and turn America into a prison state‚ locking you in your home while letting far-left rioters roam free. The Biden Lockdown will mean no school, no graduations, no weddings, no Thanksgiving, no Christmas, no Fourth of July...” “STOCK MARKET UP BIG, VACCINE COMING SOON. REPORT 90% EFFECTIVE. SUCH GREAT NEWS!”

11/9/2020, 8:48AM “RT @Reuters: Pfizer and BioNTech say their COVID-19 vaccine is more than 90% effective”

11/10/2020, 7:40PM

11/10/2020, 10:33AM “As I have long said, @Pfizer and the others would only announce a Vaccine after the Election, because they didn’t have the courage to do it before. Likewise, the @US_FDA should have announced it earlier, not for political purposes, but for saving lives!” “WATCH FOR MASSIVE BALLOT COUNTING ABUSE AND, JUST LIKE THE EARLY VACCINE, REMEMBER I TOLD YOU SO!”

11/14/2020, 10:44AM – series of 2 tweets in a thread “I LOVE NEW YORK! As everyone knows, the Trump Administration has produced a great and safe VACCINE far ahead of schedule. Another Administration would have taken five years. The problem is, @NYGovCuomo said that he will delay using it, and other states WANT IT NOW... We cannot waste time and can only give to those states that will use the Vaccine immediately. Therefore the New York delay. Many lives to be saved, but we are ready when they are. Stop playing politics!”

Date Tweet by @mtgreenee or @RepMTG 10/31/2020, 7:07PM

“THREE DAYS! SAVE AMERICA. STOP SOCIALISM. DEFEAT THE DEMOCRATS! GO VOTE TUESDAY, GEORGIA!”

11/1/2020, 2:25PM

11/4/2020, 5:46AM “I’ve made all the right enemies. The Fake News Media HATES me. Big Tech CENSORS me. The DC Swamp FEARS me. I’m running to be @realDonaldTrump’s STRONGEST ally in Congress. Too much is at stake. Vote Tuesday. SAVE AMERICA.” “STOP THE STEAL!”

11/4/2020, 1:07PM

11/4/2020, 2:20PM

11/5/2020, 4:36PM

11/5/2020, 7:44PM “Remember when Joe Biden said he had the most extensive voter fraud organization in political history? Turns out that was not a gaffe.” “The Fake News Media wants you to believe that Joe Biden (who didn’t campaign AT ALL) isn’t involved in VOTER FRAUD. He literally said he built the “BIGGEST” voter fraud organization in American history. We aren’t going to let Democrats STEAL this election. #StopTheSteal” “Every single Republican needs to be OUT FRONT and LEADING to STOP THE STEAL! Now is not the time to back down or buckle to the radical left and their allies in the Fake News Media. This is the fight of our life and we must have @realDonaldTrump’s back! We will prevail!” “We must ensure election integrity!”

11/6/2020, 12:50PM

11/8/2020, 2:21AM

11/10/2020, 11:07PM

1/3/2021, 3:27AM

1/6/2021, 12:36AM

1/6/2021, 3:26PM

1/7/2021, 3:25AM

1/7/2021, 4:13PM “All it took to “beat” @realDonaldTrump was phony witch hunts, years of coordinated lies by the fake news media, years of censorship by big tech, a CCP pandemic, endless ANTIFA / BLM riots, and a rigged election!”

“When America sees everything we are uncovering they will be disgusted and even the media won’t be able to pretend voter fraud isn’t real. Ending this crap once and for all will be fundamental to preserving our republic and faith in democracy.” “Has anyone noticed that there aren’t any violent riots, looting, and burning of cities going on? Antifa and BLM aren’t being funded to riot anymore since they think @JoeBiden won. Meanwhile, 70 million angry Americans won’t forget. Nor will we give up! #StopTheSteal” “Let’s look at some absentee voting history. 2012: Obama received 87,487 2016: Clinton received 98,417 2020: Biden received 849,182 Notice anything fishy?”

“Jan 6th, we #FightForTrump Be there! WE will object to protect the integrity of our elections and to defend the people’s votes. A fraudulent election is unconstitutional and must be rejected! #StopTheSteal” “Any Republican speaking against our Jan 6th objection tomorrow should join the Democrats who are ready to certify a stolen election. Accepting election fraud is not “constitutional.” It’s just wrong. #SurrenderCaucus” “The American people deserve elections they can trust. Thousands of sworn affidavits (at risk of JAIL TIME) were submitted confirming MASSIVE fraud. The evidence is clear. It's the duty of Congress to OBJECT to fraudulent electoral votes. Today, I will fight for our country.”

“I condemn the violence today, just like I've condemned Antifa & BLM riots that have burned our cities, attacked our police officers, & hurt so many people throughout the year. But that's not going to stop me from OBJECTING to fraudulent electoral votes with our #FightForTrump.”

Date Tweet by @mtgreenee or @RepMTG 11/13/2020, 5:18PM

“Our first session of New Member Orientation covered COVID in Congress. Masks, masks, masks.... I proudly told my freshman class that masks are oppressive. In GA, we work out, shop, go to restaurants, go to work, and school without masks. My body, my choice. #FreeYourFace”

11/13/2020, 8:54PM “I’m 100% pro life. Life starts at conception. My goal is to end abortion in America. Killing a baby in the womb is the worst lie sold to women and it doesn’t solve problems. Nor is it women’s “healthcare.” Mask wearing should be a choice bc if mask work, the wearer is safe.”

11/14/2020, 1:18PM

11/14/2020, 12:57PM

11/14/2020, 2:12PM

1/5/2021, 8:04PM “I’m here to speak the truth. Unreliable test gives unreliable data. Hospitals got paid more for Covid coded deaths. Dems shut down states, churches, businesses, schools, sports, entertainment, & life. The media spews fear & demands masks control. Time to say enough!” “Strict mask mandates & forced social distancing violate Americans guaranteed freedom of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. Draconian mandates must end. Americans should be able to choose a masks or not, and more importantly how many loved ones they invite to Thanksgiving.” “Watching woke white progressive blue check marks defend killing babies is like watching @SpeakerPelosi sing Jesus loves the little children on Sunday, then voting for tax payer funded murder on Monday. If you care about people dying, care about the millions of unborn PEOPLE.” “If I’m forced to wear a mask in @SpeakerPelosi’s House of Hypocrites, it’s going to have a message.”

1/7/2021, 4:13PM “All it took to “beat” @realDonaldTrump was phony witch hunts, years of coordinated lies by the fake news media, years of censorship by big tech, a CCP pandemic, endless ANTIFA / BLM riots, and a rigged election!”

Table A5: Sampling of Tweets by Lindsey Graham and Mitch McConnell about the 2020 Election

Date Twitter Handle Tweet 10/26/2020, 6:36PM @LindseyGrahamSC “This is a big choice election: we're voting between law and order and lawlessness, between economic shut downs or economic growth, and free markets or socialism. South Carolina needs @LindseyGrahamSC & @realDonaldTrump re-elected Tuesday. VOTE!”

10/26/2020, 7:58AM @LeaderMcConnell “Here’s how this must work in our great country: Every legal vote should be counted. Any illegally-submitted ballots must not. All sides must get to observe the process. And the courts are here to apply the laws & resolve disputes. That's how Americans’ votes decide the result.”

10/27/2020, 6:31AM

10/30/2020, 4:47PM @LindseyGrahamSC “I do look forward to hearing from and will listen closely to the objections of my colleagues in challenging the results of this election. They will need to provide proof of the charges they are making.” @LindseyGrahamSC “They will also need to show that the failure to take corrective action in addressing election fraud changed the outcome of these states’ votes and ultimately the outcome of the election.”

11/2/2020, 4:33PM @LeaderMcConnell “I will vote to respect the American people’s decision and defend our system of government.”

11/9/2020, 7:31AM

11/9/2020, 8:48AM @LindseyGrahamSC “Those who made this attack on our government need to be identified and prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. Their actions are repugnant to democracy.” @LindseyGrahamSC “Lindsey Graham criticizes security response to Capitol siege, saying rioters could have killed lawmakers: “Black Lives Matter protests — have you seen the images on the Capitol steps where you had National Guard members in riot gear? Why weren't you as prepared this time around?””

Table A5: Continued

11/10/2020, 7:40PM @LindseyGrahamSC “I pledge to work with @SenatorTimScott and others to review voting procedures, particularly regarding mail-in ballots, so we can ensure millions of Americans who have doubt that we are not ignoring the problem.”

Date Tweet by @McConnellPress or @LeaderMcConnell 10/30/2020, 6:48PM

“This month, @SenateMajLdr McConnell visited Bell County to thank #Kentucky healthcare heroes for their courage during COVID-19. Bell County has received nearly $6 million from Sen McConnell's CARES Act to beat this virus #Bluegrass120”

11/10/2020, 1:31PM “.@SenateMajLdr McConnell Celebrates Vaccine Developments and Falling Unemployment Rate”

11/10/2020, 3:52PM

11/12/2020, 5:30PM “Yesterday, we learned one COVID-19 vaccine candidate may be more than 90% effective. This huge good news is a testament to the ingenuity of the American private sector and the historic groundwork laid by Congress and the Trump Administration.” “This week’s news on a COVID-19 vaccine was incredibly promising. All of us have to keep up commonsense precautions in the meantime. The virus is spreading quickly in Kentucky and nationwide, and it doesn’t care whether we’ve gotten bored with wearing masks or social distancing.”

APPENDIX B: FIGURES

FIGURE B2.

“Donald Trump won the 2020 U.S. presedential election.”

FIGURE B3.

“Voting by mail is a major cause of voter fraud in the U.S.”

FIGURE B4.

“Vaccines save lives.”

FIGURE B5.

“The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol Building was carried out by ANTIFA and other left-wing groups..”

REFERENCES

1. Basit, A. (2021). Conspiracy theories and violent extremism: Similarities, differences and the implications. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 13(3), 1-9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27040260 2. Canon, D. T., & Sherman, O. (2021). Debunking the ‘big lie’: Election administration in the 2020 presidential election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51(3), 546-581. DOI: 10.1111/psq.12721 3. Casarões, G., & Magalhães, D. (2021). The hydroxychloroquine alliance: How far-right leaders and alt-science preachers came together to promote a miracle drug. Brazilian Journal of

Public Administration, 55(1), 197-214. http://dx.doi. org/10.1590/0034-761220200556 4. Cole, J., & Dodds, K. (2021). Unhealthy geopolitics?

Bordering disease in the time of coronavirus.

Geographical Research, 59(2), 169-181. DOI: 10.1111/1745-5871.12457 5. Daniller, A. (2021, March 18). Majorities of

Americans see at least some discrimination against

Black, Hispanic and Asian people. Pew Research

Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2021/03/18/majorities-of-americans-see-atleast-some-discrimination-against-black-hispanicand-asian-people-in-the-u-s/ 6. Eberl, J.-M., Huber, R. A., & Greussing, E. (2021). From populism to the ‘plandemic’: Why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections,

Public Opinion and Parties, 31(S1), 272-284. DOI: 10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730 7. Enders, A. M., & Uscinski, J. E. (2020). Are misinformation, antiscientific claims, and conspiracy theories for political extremists? Group

Processes and Intergroup Relations, 24(4), 583-605.

DOI: 10.1177/1368430220960805 8. Grant, J. (2019). Taking conspiracy theory seriously. New Political Science, 41(3), 476-478. DOI: 10.1080/07393148.2019.1631579 9. Grynbaum, M. M., Alba, D., & Epstein, R. J. (2021,

March 1). How pro-Trump forces pushed a lie about antifa at the capitol riot. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/01/us/

politics/antifa-conspiracy-capitol-riot.html 10. Hofstadter, R. (1979). The paranoid style in American politics, and other essays. University of Chicago

Press. 11. Brendan. (2021). Trump twitter archive [Data set]. https://www.thetrumparchive.com 12. Inbar, Y., & Lammers, J. (2012). Political diversity in social and personal psychology. Perspectives on

Psychological Science, 7(5), 496-503. https://www. jstor.org/stable/44280797 13. Koblentz-Stenzler, L., & Pack, A. (2021). Infected by hate: Far-right attempts to leverage anti-vaccine sentiment. International Institute for Counter-

Terrorism (ICT). https://www.jstor.org/stable/ resrep30926 14. Klein, E., & Robison, J. (2020). Like, post, and distrust? How social media use affects trust in government. Political Communication, 37(1), 46-64.

DOI: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1661891 15. Kruglanski, A. W., Gunaratna, R., Ellenberg, M., & Speckhard, A. (2020). Terrorism in time of the pandemic: Exploiting mayhem. Global Security:

Health, Science and Policy, 5(1), 121-132. https://doi.or g/10.1080/23779497.2020.1832903 16. Littman, J., Wrubel, L., Kerchner, D., Smith, D., &

Bonnett, W. (2020). gwu-libraries/TweetSets: Version 1.1.1 (1.1.1) [Computer software]. Zenodo. https://doi. org/10.5281/ZENODO.3726161 17. Lynch, F. R. (2019). ‘How did this man get elected?’

Perspectives on American politics, populism and

Donald Trump. Society, 56(3), 290-294. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12115-019-00366-5 18. McCarthy, B. (2021, April 15). Tucker Carlson falsely claims COVID-19 vaccines might not work. Politifact. https://www.politifact.com/ factchecks/2021/apr/15/tucker-carlson/tuckercarlson-falsely-claims-covid-19-vaccines-mi/ 19. McNeil-Willson, R. (2020). Framing in times of crisis:

Responses to COVID-19 amongst far right movements and organisations. International Centre for

Counter-Terrorism. https://www.jstor.org/stable/ resrep25256 20. Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016).

Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning:

The moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824-844. DOI: 10.1111/ajps.12234 21. Moskalenko, S., & McCauley, C. (2021). QAnon:

Radical opinion versus radical action. Perspectives on Terrorism, 15(2), 142-146. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/27007300 22. Naylor, B. (2021, February 10). Read Trump’s Jan. 6 speech, a key part of impeachment trial. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/10/966396848/ read-trumps-jan-6-speech-a-key-part-ofimpeachment-trial 23. Nobles, R. (2021, May 22). Marjorie Taylor Greene compares House mask mandates to the Holocaust.

CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/21/politics/ marjorie-taylor-greene-mask-mandates-holocaust/ index.html 24. Rios, R. (2020). Why misery loves company: The rise of conspiracy theories and violent extremism. Institute for European Studies. https://www.ies.be/files/IES-

Policy-Brief-Raul-Rios.pdf 25. Russonello, G. (2021, April 30). The rising politicization of covid vaccines. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/06/us/ politics/covid-vaccine-skepticism. html?searchResultPosition=15 26. Sawyer, P. S. (2021). Conspiracism in populist radical right candidates: Rallying the base or mainstreaming the fringe? International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 11(1). https://doi. org/10.1007/s10767-021-09398-4 27. Smith, A., & Anderson, M. (2018). Social media use in 2018. Pew Research Center. https:// www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/9/2018/02/PI_2018.03.01_Social-Media_

FINAL.pdf 28. Stecula, D. A., & Pickup, M. (2021). How populism and conservative media fuel conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 and what it means for COVID-19 behaviors. Research and Politics, 8(1). DOI: 10.1177/2053168021993979 29. Stolberg, S. G. (2021, April 5). Trump claims credit for vaccines. Some of his backers don’t want to take them. New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/2020/12/18/us/politics/trump-vaccineskeptics.html?searchResultPosition=17 30. Blair County, Pennsylvania. (2020). Summary results report: General election. http://www.blairco.org/

Dept/Elections/Election%20Results/2020%20

General%20Election/Official%20Summary.pdf 31. Tackett, Michael. (2019, April 24). Strong support here helped Trump win Pennsylvania in 2016. 2020 could be different. New York Times. https:// www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/us/politics/ trump-pennsylvania.html?searchResultPosition=1 32. Thomas, E., & Zhang, A. (2020). ID2020, Bill Gates and the mark of the beast: How Covid-19 catalyses existing online conspiracy movements. Australian

Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.jstor.org/

stable/resrep25082 33. Thrush, G., Becker, J., & Hakim, D. (2021, August 15).

Tap dancing with Trump: Lindsey Graham’s quest for relevance. New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/2021/08/14/us/politics/lindsey-grahamdonald-trump.html 34. United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: Altoona

City, Pennsylvania. https://www.census.gov/ quickfacts/altoonacitypennsylvania 35. Walther, S., & McCoy, A. (2021). US extremism on telegram: Fueling disinformation, conspiracy theories, and accelerationism. Perspectives on

Terrorism, 15(2), 100-124. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.2307/27007298 36. Westneat, D. (2021, July 3). ‘We are all victims’: How

Republicans became the party of the persecution complex. The Seattle Times. https:// www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/ we-are-all-victims-how-republicans-became-theparty-of-the-persecution- complex/ 37. Zarefsky, D. (2004), Presidential rhetoric and the power of definition. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34(3): 607-619. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00214.x

About the Author

Sarah Corso is a Fall 2021 graduate of the George Washington University, where she double majored in International Affairs and French. She hails from Altoona, Pennsylvania, USA. A student of languages and politics, she is fascinated by populist and right-wing movements around the globe and seeks to understand what motivates individuals to support them. In the future, she hopes to continue these types of conversations in theory and in practice. Sarah currently works as Program Coordinator at the An-Bryce Foundation, an organization dedicated to serving under-resourced young people in the DC area.

Mentor Details

Claudine Kuradusenge-McLeod is a professor of International Affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs. Originally from Rwanda, she specializes in Diaspora consciousness, social mobilization, and genocide prevention. She has worked in several countries in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. As a human rights activist, she has been on the front line of racial conflicts, youth education training as well as racially and culturally sensitive initiatives.