17 minute read

Rembrandt: Seeking Closure in Classical Narratives

KEYWORDS: Rembrandt, classics, Lucretia, Callisto, art history DOI: https://doi.org/10.4079/2578-9201.1(2022).07

Advertisement

PARKER BLACKWELL

ARCHAEOLOGY & CLASSICAL and ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN STUDIES, CCAS ‘23, pblackwell33@gwu.edu

ABSTRACT

In many of Rembrandt’s depictions of mythical themes, he humanized the fantastical. Through realism and austere symbology, Rembrandt innovated classical narratives. Three of Rembrandt’s late works highlight the apex of his study of the complex emotion underlying the mythical characters of Lucretia and Callisto. Both women were rape victims immortalized in moments of shame. Rembrandt’s model for Woman Bathing in a Stream, housed at the National Gallery in London, may have been his mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels, who was ostracized by society for unchaste acts. Thus, sexual shaming was a topic that interested Rembrandt both artistically and personally. This paper will draw on previous scholarship to explore Rembrandt’s inspiration for and manipulation of classical narratives. Moreover, it will consider how Rembrandt’s deeply emotional depictions of women echo the struggles pervading his personal life at the time of their creation.

INTRODUCTION

Myths are distillations of universal themes. As they age, myths take on complex personalities and carry immense pathological and rhetorical weight. Artists often experimented with mythological themes throughout history. Although universality defines classical narrative, the spirits of myths often became lost in translation. Through time and space, classical myths, transmitted in oil rather than words, took on distinctly new meanings in 16th and 17th-century Northern Europe. Paintings of classical subjects in the Baroque period were primarily used to send moralizing messages and glorify individuals, regions, or even ideologies (Blankert & Slujite, 1980, p. 56).

While the archetypal nature of myths makes them effective vehicles for a range of themes, mythic iconography can also fall into monotonous patterns. When this occurs, myths lose their dimensionality; characters in them become objects instead of people. Worse still, repetitive interpretations of a myth form an echo chamber, capable of intensifying both positive and negative rhetoric. Baroque paintings of mythological subjects, especially, are some of the most telling of the artists and societies in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Of the old masters in the Baroque period, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) is one of the most celebrated because of his technical skill and innovative renditions of mythological themes. While Rembrandt also utilized mythic themes to convey nuanced messages and reflect his patrons’ values, he often went one step further. Rembrandt imbued his paintings with emotion by inserting his own values and life experiences into subtle details throughout his work. The resulting paintings contain unusually complex, authentic characters.

Three of Rembrandt’s late works highlight the pinnacle of his pathological survey of mythological subjects. Inspired by the works of his contemporaries, his personal life, and the myths themselves, Rembrandt wrought masterful portraits of Lucretia and Callisto in Woman Bathing in a Stream (1654), Lucretia (1664), and Lucretia (1666). Both Callisto and

FIGURE 1.

“A Woman Bathing in a Stream (Callisto in the Wilderness)” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1654.

FIGURE 2.

“Lucretia” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1664.

Lucretia are historical victims of rape used as cautionary tales for the unchaste (Fig. 1-3).

Over time, these women became collateral damage to a social narrative. Artists highlighted their characteristics that fit a moralizing story and discarded the rest. Unlike his contemporaries, Rembrandt depicted Lucretia and Callisto as more than just objects of shame. One reason for Rembrandt’s inspired approach is that Lucretia and Callisto’s characters reminded the artist of his personal struggles. Rembrandt’s model for Woman Bathing in a Stream, housed at the National Gallery in London, may have been Rembrandt’s mistress, Hendrickje Stoffels. Like Callisto, Stoffels was ostracized by society for her promiscuity. Rembrandt’s personal experience and artful approach recovered myths lost in translation and breathed renewed life into beloved classical narratives.

BREAKING THE MOLD

Early in the 17th century, the source material for illustrations of myth was limited to a small set of illustrated copies of Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Baroque paintings of classical myths fell into a monotonous repetition of archetypes. While the Renaissance masters took on myths with fresh eyes, overwhelmingly, Baroque artists approached myths with a singular understanding. Although stylistically, depictions of myths varied, substantively, they remained the same. Baroque depictions of myth became sensationalized, preoccupied with the image rather than the narrative. As a result, mythological depictions in the Baroque period lacked sincere emotional nuance. With each copied illustration, mythological characters became, at best, misunderstood, and worst, hollow. Like his contemporaries, Rembrandt adopted many Baroque techniques in his depictions of myth. However, to bring the emotional implications of antique narratives into the present, he also experimented with tone and emotional drama in his art. Thus, Rembrandt’s paintings are compelling, both visually and psychologically. In his classical paintings, Rembrandt drew heavily on personal experience and challenged typical ways in which artists depicted mythological subjects.

Where many Baroque artists at this time embellished mythological illustrations, Rembrandt revolutionized them. Rembrandt omitted classical iconography, applied experimental Baroque lighting, and emphasized each myth’s peripeteia, or climax. At times, these experiments yielded startling effects. Consider, for example, The Abduction of Ganymede, where Rembrandt merged the classical myth of Jupiter’s abduction of Ganymede with modern dress and unflattering realism to strange and comical effect (Fig. 4) (Russell, 1997, p. 5)

FIGURE 3.

“Lucretia” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1666.

FIGURE 4.

“The Abduction of Ganymede” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1635.

A practiced eye might appreciate how Rembrandt’s innovative interpretation of the narrative sought to draw the human from the myth. By humanizing Ganymede’s mythic beauty, Rembrandt made the character relatable. Rembrandt diminished omnipotent gods to men, accessible in their imperfection. Equally impressive, Rembrandt uplifted characters that other artists satirized and turned them into multidimensional individuals, worthy of our compassion.

Rembrandt’s applications of the Baroque style in classical narratives culminated in three poignant masterpieces full of emotional drama: Woman Bathing in a Stream (1654), Lucretia (1664), and Lucretia (1666). By the mid-17th century, when these were painted, these subjects had become emblems of shame. Renditions of Callisto’s suffering warned against lustful temptation, and those of Lucretia detailed the ideal woman as one who would die rather than dishonor her name. By this period, Callisto and Lucretia were no longer heroes or victims in their own stories but objects to be scorned, avoided, or desired. This reduction robbed these characters of their dimension and relatability. Despite the norm, Rembrandt took measures to reimagine Lucretia and Callisto as more than collateral damage in a cautionary tale. LUCRETIA

According to the Roman historian Livy, Lucretia was the wife of the Roman Consul Tarquinius Collatinus (Donaldson, 1982, p. 3-5). One night, the Roman Emperor’s son Tarquin became incensed by his desire for Lucretia and forced himself upon her. Overcome by the shame of diminishing her family name, Lucretia committed suicide to restore her family’s honor. Witnessing her death, Brutus was inspired to overthrow the tyrannous monarchy and form the Roman Republic. Although a legend, Lucretia remains the ideal of a dutiful Roman woman to this day.

In the last five years of his life, Rembrandt painted Lucretia twice. He completed his first painting of her in 1664 and followed up with a second in 1666. The pair represent the moments just prior to and following Lucretia’s suicide (Wheelock & Keyes, 1991). In the first painting, Lucretia is regally clad in gold and jewels. She braces herself for the impact of the blade, which she angles at her heart. Her entire body is tensed except for her head, which hangs slightly as she casts her eyes down mournfully at her resolute hand. In the second painting, Lucretia’s form is limp. All tension has moved to one hand, grasping the lone cord supporting her; she is literally hanging by a thread. The dagger is lowered, and blood stains the front of her tunic. Cold darkness fills the space as the gold brocade of Lucretia’s robe falls away, and the only light left to draw the eye reflects off of her wilting form. Lucretia’s tearful eyes have shifted, and in them, we see her reluctance turn slowly into regret.

Rembrandt’s depictions of Lucretia were in sharp contrast to the tone and style of contemporary depictions. Artists over the years exaggerated Lucretia as the ideal Western woman, simultaneously seductive and chaste. Unlike Rembrandt’s rendering, where Lucretia is fully-clothed, the vast majority of Baroque artists, including Caravaggio, Titian, and Lucas Cranach, painted Lucretia in the nude (Willis, 2000, p. 51). In Ovid’s telling of the myth, “[Lucretia’s] last thought was to wrap clothes about herself modestly as she fell” (Donaldson, 1982, p. 14). However, most artists likely learned about the myth of Lucretia through art, not literature, causing a change in the narrative. Influenced by famous works like Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia (Fig. 5), depicting Lucretia nude became standard. Thus, Lucretia was transformed from a heroine to a pretext for a female nude. Lucretia’s

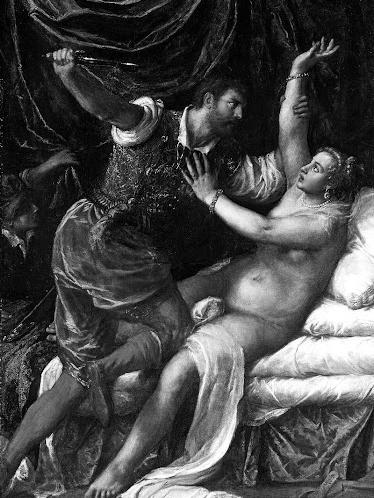

FIGURE 5.

“Tarquin and Lucretia” by Titian, 1571. FIGURE 6.

“Lucretia” by Crispin de Passe the Elder, 1599.

nakedness ultimately detracts from her traditional exemplification of pudicitia, or sexual chastity. Consider Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia, wherein the assaulter, Tarquin, is fully clothed and the unsuspecting victim, Lucretia, is nude. Exposed and powerless, Lucretia becomes a victim instead of an agent in her own story.

Contrary to the myth’s original message, Lucretia is needlessly demeaned and sexualized in art. Today, discourse around Lucretia disgracefully highlights the cleverly “penetrating” nature of the knife with which Lucretia kills herself (Donaldson, 1982, p. 17). Unfortunately, given depictions such as Crispin the Elder’s near-pornographic engraving of Lucretia, such dialogue seems appropriate to the subject (Fig. 6) (Veldman, 1986, p. 124). Like many others, Crispin’s engraving is a copy of a copy, exaggerated and satirized with each iteration. In these copies, the original myth is lost, and so is Lucretia’s dignity. Thus, countless artists cheapened the honor Lucretia earned with her sacrifice. Instead, Lucretia came to represent the shame forced upon her.

Shame robs people of their humanity, and over time, that is precisely what happened to Lucretia. History forgot the depth and complexity of her strife, and with it, her heroism. Martha Hollander remarks that Lucretia was a famous subject in art “because of her shame rather than for her noble gesture” (2003, p. 1333). Hollander continues to say that in art and life, “the basic experience connected with shame is that of being seen” (2001, p. 1328). Common depictions of Lucretia were devoid of introspection because, in them, Lucretia was an object to be viewed instead of a person with whom to empathize. In the 17th century, Lucretia was often a subject in pittura infamanta, a literal “shaming pictures” (Hollander, 2003, p. 1329). Even in Rembrandt’s renditions, the Lucretia is situated in stage-like compositions. Bed drapes echo stage curtains, and chiaroscuro, juxtaposed highlights and shadows, doubles as a spotlight, exposing the accused. Lucretia is the entertainment, and her shame is the only act. Rendered this way, her sacrifice becomes a warning instead of an inspiration. Nevertheless, for centuries, women have been left considering Lucretia shown as the perfect woman: sexual yet chaste, weak yet unflinching. Given this model, some viewers may be frightened into passivity. Others may look at Lucretia and see their own shame cruelly cast back at them. Therefore, Baroque depictions of Lucretia rob women of all periods of authentic female empowerment.

Even in light of the shameful staging of Rembrandt’s Lucretia paintings, he portrayed her with unparalleled dimensionality. Unlike his predecessors, who often minimized Lucretia’s agency, Rembrandt emphasized Lucretia’s introspection by centering the source material. In his paintings, Rembrandt diverged from the narrative that honor is Lucretia’s sole motivator. Instead, he transformed Lucretia’s shame into humanizing guilt. In this case, Lucretia’s guilt encompasses the “psychological factors of shock, depression, and humiliation that might lead a woman to suicide.” As such, Rembrandt made Lucretia a multifaceted individual (Donaldson, 1982, p. 23). Her inner conflict writhes just below the surface as self-preservation wars with duty. Her sacrifice is made more impressive by her struggle, and her humanity inspires rather than intimidates. Rembrandt’s attention to Lucretia’s deep psychological tension resulted in two paintings that empower women instead of shame them. CALLISTO

Callisto features both in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Fasti. In the myth, Callisto begins as Diana’s favorite huntress. The story opens with Callisto taking an oath of sisterly chastity, but not long after, Jupiter comes upon Callisto and, disguised as Diana, rapes her (Ovid, 1931, p. 155). Subsequently, when Callisto hesitates to bathe with Diana and the other nymphs, the Virgin Goddess orders the nymphs to strip her. When Callisto’s pregnancy and betrayal are revealed in turn, Diana exiles her. After Callisto carries her baby to term, Jupiter’s vengeful wife Hera transforms Callisto into a bear. From Callisto’s perspective, Ovid details years spent in fear as she is hunted across her homeland (Ovid, 1916, p. 475). Callisto remains this way until, in a moment of misfortune, her son Arcas comes upon Callisto while hunting. In a moment of pity, Jupiter spares Callisto, immortalizing her as the constellation Ursa Major.

As with Lucretia, Rembrandt painted Callisto twice. He first depicted her in Diana Bathing with her Nymphs with Actaeon and Callisto (1634) in a dual scene conveying the danger of succumbing to temptations (Fig. 7) (Blankert & Slujiter, 1980, p. 58). Several years later, Rembrandt revisited the topic of Callisto in Woman Bathing in a Stream, alternatively titled Callisto in the Wilderness.

FIGURE 7.

“Diana Bathing with her Nymphs, with the Stories of Actaeon and Callisto” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1634.

Rembrandt imagines a world where Callisto finds peace after her exile in honor of Stoffel’s suffering.

Alternatively, perhaps it was Stoffel’s strength through her adversity that provoked Rembrandt to rectify Callisto’s story. Tragically, Rembrandt only referred to Stoffels as his wife after her death in 1663 (Willis, 2000, 13). Following Stoffel’s death, Rembrandt completed two of his most sensitive and intellectual works to date, depicting Lucretia (Tuominen, 2015). Through Rembrandt’s subject matter immediately following Stoffel’s death, we see how Rembrandt himself was struggling to find emotional closure in the face of mortality. It may be that Lucretia’s turmoil and guilt reflect some of Rembrandt’s own regret for publicly denouncing Stoffels in her time of need. Alternatively, rendering Stoffels as the heroine of Rome may be a tribute to the struggles Stoffels faced in living up to the 17th-century ideal woman. Like Lucretia, Stoffels met death full of unresolved shame. This is clearly visible in Rembrandt’s 1664 painting of Lucretia. However, as mentioned, Rembrandt ultimately chose to absolve Lucretia of shame in 1666. Therefore, through art, we bear witness to Rembrandt’s pursuit of emotional closure in the last years of his life. CONCLUSION

It is clear that Rembrandt’s depictions of the myths of Callisto and Lucretia reflect sincere efforts to evaluate myths for their universal truths. Amidst a sea of superficial copies morphed to fit capricious morals, Rembrandt was original. To extract the person from the myth, Rembrandt had to consider myths in the context of his own life. The products of this reflection are unique interpretations of classical narratives populated by multidimensional, flawed characters. In them, we see every part of ourselves reflected, and in that way, they become real.

FIGURE 10.

“A young woman sleeping (Hendrickje Stoffels)” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1654. FIGURE 11.

“Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels” by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 16541656.

REFERENCES

1. Blankert, A., and Slujiter, E.J. (1980). Depiction of

Mythological Themes. In Gods, Saints, & Heroes :

Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt (exhibition).

National Gallery of Art. 2. Boogert, B. (1999). Rembrandt and his picturesque universe: The artist’s collection as a source of inspiration. In Rembrandt’s Treasures. Rembrandt

House Museum. 3. Bowron, E.P., Butterfield, A., & Clarke, M. (2010).

Titian and the Golden Age of Venetian Painting:

Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland.

Museum of Fine Arts. 4. Cornelis, B. (2019). Rembrandt’s ‘A Woman bathing in a Stream’ at The National Gallery in London. ArtUk. 5. Donaldson, I. (1982). The shaping of the myth: victims and victors. In The Rapes of Lucretia: Myth and Its Transformations. Clarendon Press. 6. Hollander, M. (2003). Losses of Face: Rembrandt,

Masaccio, and the Drama Of Shame. Social Research, 70(4), 1327–1350. 7. Johnson, WR. (1996). The Rapes of Callisto and

Readings of Ovid’s Versions in the ‘Metamorphoses’ and the ‘Fasti.’ The Classical Journal (Classical

Association of the Middle West and South), 92(1), 9–24. 8. Leja, J. (1996) Rembrandt’s ‘Woman Bathing in a

Stream. Simiolus, 24(4), 320–327. 9. Ovid. (1931) Fasti. Translated by James G. Frazer.

Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library (253).

Harvard University Press.

10. Ovid. (1916). Metamorphoses, Volume I: Books 1-8.

Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G.P.

Goold. Loeb Classical Library 42. Harvard University

Press. 11. Partsch, S. Rembrandt. London: Weidenfeld and

Nicolson, 1991. 12. Rijn, R.H. (1630). Andromeda Chained to the Rocks [Oil

Painting]. The Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/our-collection/ artworks/707-andromeda/ 13. Rijn, R.H. (1634). Diana Bathing with her Nymphs, with the Stories of Actaeon and Callisto [Oil Painting].

Museum Wasserburg Anholt, Isselburg, Germany. 14. Rijn, R.H. (1635). The Abduction of Ganymede [Oil

Painting]. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden,

Dresden, Germany. 15. Rijn, R.H. (1654). A Woman Bathing in a Stream (Callisto in the Wilderness) [Oil Painting]. National

Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States. 16. Rijn, R.H. (1654). A young woman sleeping (Hendrickje Stoffels) [Brown Wash on Paper].

The British Museum, London, England. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/ object/P_1895-0915-1279 17. Rijn, R.H. (1654-1656). Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels [Oil Painting]. The National Gallery, London,

England. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/ paintings/rembrandt-portrait-of-hendrickjestoffels 18. Rijn, R.H. (1664). Lucretia [Oil Painting]. National

Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States. 19. Rijn, R.H. (1666). Lucretia [Oil Painting]. Minneapolis

Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MI, United States. 20. Rijn, R.H., Bikker, J., Hinterding, E., Hoyle, M.,

Krekeler, A., Schapelhouman, M., Weber G.J.M.,

White, C., & Wieseman, M.E. (2014). Rembrandt, the

Late Works. National Gallery Company, in association with the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. 21. Rijn, R.H., Heel, S.A.C., & Loyd Williams, J. (2001).

Rembrandt: his life, his wife, the nursemaid and the servant. In Rembrandt’s Women. Prestel. 22. Rijn, R.H., Brown, C., Kelch, J., and Thiel, P. (1991).

Rembrandt: the Master and His Workshop. Edited by Sally Salvesen. National Gallery Publications,

London. 23. Rosenberg, J. (1968). Rembrandt’s Life. In Rembrandt:

Life and Work. Phaedon Press, 1968. 24. Russell, M. (1977). The Iconography of Rembrandt’s

“Rape of Ganymede.” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 9(1), 5–18. https://doi. org/10.2307/3780422 25. Schatborn, Peter. (1975). ‘Diana and Callisto’ by

Hendrick Goltzius. Master Drawings, 13(2), 142–188. 26. Slive, S., and Rijn, R.H. Mythological and Historical

Subjects. In Rembrandt Drawings, (177–94). J. Paul

Getty Museum. 27. Titian. (1556-1559). Diana and Callisto [Oil Painting].

The National Gallery in London, London, England. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/ titian-diana-and-callisto 28. Titian. (1571). Tarquin and Lucretia [Oil Painting]. The

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom, https://collection.beta.fitz.ms/id/object/656 29. Trendall, Arthur. (1977). “Callisto in Apulian Vase

Painting.” Antike Kunst, 20(2), 99–101. 30. Tuominen, M.. (2015). Late Rembrandt. Rijksmuseum 12.2.–17.5.2015. Walter Liedtke in memoriam. Tahiti, 5(1). 31. van de Passe the Elder, C. (1599). Lucretia [Engraving]. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France. 32. Veldman, I. Lessons for Ladies: A Selection of

Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Prints.

Simiolus, 16(2/3), 113–127. 33. Willis, K. (2000). Hendrickje Stoffels: Rembrandt van

Rijn’s Incarnation of Medea. Electronic Thesis or

Dissertation. University of Cincinnati. 34. Wheelock, A.K., and Keyes, G. (1991). Rembrandt’s

Lucretias, National Gallery of Art. Exhibition catalogue. 35. Zuffi, S. (2011). Rembrandt. Prestel.

About the Author

Parker Blackwell is a rising Senior studying Archaeology, and Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences. Her research interests include the reception of the classical world and cultural heritage preservation. Ms. Blackwell recently completed a Luther Rice Fellowship concerning localized approaches for protecting cultural heritage under threat in the Republic of Cameroon. Ms. Blackwell plans to pursue this study in graduate school following her time at the George Washington University.

Mentor Details

Rachel Pollacks is an Adjunct Professor of Art History and an Instructor of Writing in George Washington’s University Writing Program. She received a MA at the George Washington University and a PhD in Art History from the University of Maryland. Dr. Pollack also holds a research position at the National Gallery of Art with research interests in Baroque fine art.