thecrossingattheriver

By Eric Grant

By Eric Grant

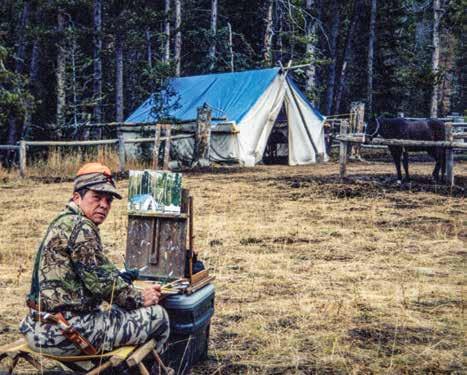

Photo by Ronnie Williford

Photo by Ronnie Williford

By Eric Grant

By Eric Grant

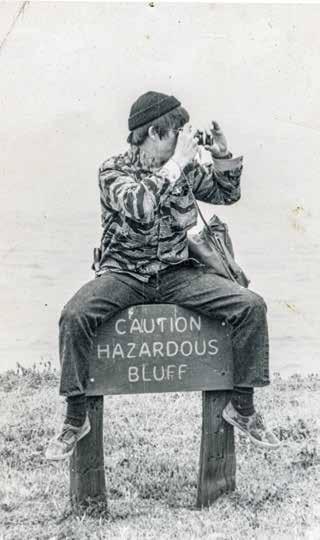

Photo by Ronnie Williford

Photo by Ronnie Williford

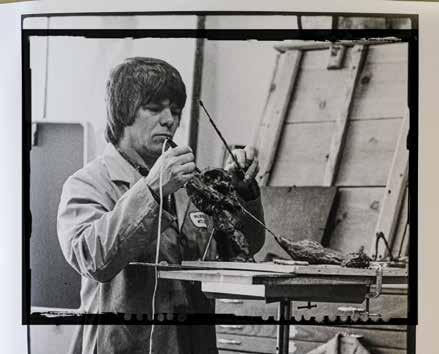

Hollis works quietly on The Need to Know in his Loveland, Colorado, studio.

Hollis works quietly on The Need to Know in his Loveland, Colorado, studio.

English is unique among the world’s 7,100 known languages because of its use of the verb “do.”

The word itself is a vestige of Celtic languages that flowed through time from Old English to Middle English and into the language we speak today.

For instance, an English speaker today would ask, “Did you notice he paints?”

A French speaker would put it more succinctly: “Notice you he paints?”

Linguist John McWhorter calls the use of “to do” in English “the meaningless do” — a distinctive attribute that vexes even the most competent student attempting to learn our language.

There was nothing meaningless about Hollis Williford and his compulsion to rise up each day and do something, anything. He had many things to do, to get off his chest.

His life was defined by doing, and in this way, he created a lasting legacy.

But time was Hollis’ greatest enemy, and he was not satisfied with just being. He had to do.

As a young man, he bore great and unexpected responsibilities that slowed him from doing what he was meant to do.

When his father abandoned the family, Hollis, in his early 20s at the time, remained with his mother, brother and sisters to support them financially. Diagnosed with diabetes as a young man and faced with a near-death experience in his early 50s, he was acutely aware of the compression of time, that his life would be

shortened and the ideas in his head would have less time to blossom and come to fruition.

Hollis said he had two fears:

The first was being bored, which he never was.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘I guess I’ll just go to the bar and have a few drinks. I just don’t have anything else to do.’ I cannot conceive of people not having anything to do,” he said. “I can’t understand that when I think about the things I would like to do and the places I would like to go and the things I would like to accomplish with whatever I have left of the life that I have. The problem I have is not having enough time to do it all.”

The second was wasting a life, which he didn’t do.

“I would like people to know that I have not wasted a life,” he said, “that all the efforts have been for the positive, and that’s a big part of my fulfillment.”

The irony of his life is that his perceived lost time drove him harder, further and faster — many times to the detriment of his health — thus shortening the minutes, hours and days he had left to create.

But Hollis would not want to be defined by his health; he would want to be remembered for his work and, as he grew older, for his ideas about art and creative processes that he imparted to friends, family and colleagues.

These things live on in countless places — in the minds of the people he knew and loved, and in the institutions and private collections where his life’s work remains for all to see.

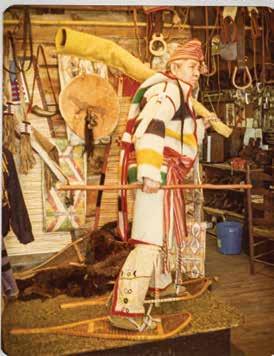

Traditional dance to the Indians of the plains and prairies was as socially enjoyable or recreational as it was ritualistic or ceremonial. Many dances told stories of brave deeds, brought together young couples, and honored important members on special occasions. During the latter years of the 1800s, the U.S. military had forbidden the Sun Dance rituals as well as war dances. The tribes were only allowed the local gatherings or pow-wows to celebrate Anglo holidays such as the 4th of July. This did, however, allow the dancers a means of carrying on the dance tradition, even if it was more for the entertainment of the Anglos than for the tribal spirit. The costume in the sculpture is indicative of that time period and is composed of naturalcolored feathers, German trade silver and harness bells. The self-assured gesture emulates the strut of a prairie chicken trying to attract a mate with tucked wings and shuffling feet. — HW

Photos by Eric Grant

Photos by Eric Grant

This concept of the seal hunter was inspired by a research trip to Manitoba, Canada. For the Arctic tribes, seal hunting is the main source of food during the most extreme and difficult time of the year. For me, the difficult part was to interpret a gesture that would show the harsh environment as well as the stress of the hunt. The next step was doing the homework necessary to ensure accuracy of costume, tools and size relationships of animal to man. With many preliminary drawings of the body language, I was able to create maximum stress in pulling, gravity and weight by counterbalance of the figure. The taut tumpline and the burden of the pack over the heavy winter parka complete the illusion of primitive man against the elements. — HW

Hunter’s Return, bronze, 28” long Edition

Hunter’s Return, bronze, 28” long Edition

Photo by Marty Asplin

Photo by Bart Ashford

Photo by Marty Asplin

Photo by Bart Ashford

Hanging in my home is the down payment for this book, what I consider to be one of Hollis’ greatest paintings. The subject is a herd of bison spread out among the sagebrush at the base of Blacktail Butte near Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

It’s a late-summer day. The grass is mature and yellow. The calves, half grown, graze near their mothers. And the bulls, in an agitated, mid-rut state with their tails twisted and raised, have gathered at the edge of the herd.

At one time, 60-80 million of these animals roamed America’s mountain valleys and Great Plains. Fossil records indicate they occupied these lands for nearly 175,000 years, yet in less than 20 of those years — from about 1865-1885 — Anglo-Americans completely decimated their population. It was among the swiftest and largest near-extinctions of warm-blooded animals in the history of the world.

There were many motivations for killing the bison, but ranking most prominently was a desire to eradicate the primary food source for the Plains Tribes. Once the bison were gone, so too would be the Native Americans.

So Hollis came west, to trace the old trails, to capture with pen and brush what it must have looked like to have arrived in such a place where the bison once roamed free.

He understood the instinctual drive to be, to exist, to live. He knew the fragility of it all, that life was placed precariously on the tip of a spear and could end or change completely in a moment. Even the mighty bison could be felled and destroyed.

To inspire his work, he went directly to the source. He traveled to see the herds himself. He wanted to see the mountains and the streams as they really were. He scoured over old artifacts, pored over original writings.

One such source was the Voyage of Discovery of 1803-1806, Lewis and Clark’s exploration of the Louisiana Purchase. In their journal, they described things that will never be seen again — the native encampments along the rivers, the cottonwood forests and undulating plains teeming with flora and fauna, and the immense herds of bison that stretched as far as they could see.

The explorers eventually found the sources they were looking for — the headwaters of the Missouri River, a place now called Three Forks in Montana — where the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin rivers converge to form the longest river and the largest watershed in the United States.

Inspired to follow in the explorers’ footsteps, Hollis camped along the banks of the Madison in the late 1970s. He came to see the Buffalo Jump, a rocky cliff that rises from the valley floor. The ancient hunters had once driven bison off its edge to kill their prey in masses.

Beneath the cliff, the hunters skinned and butchered the bison with flint knives. The meat was sliced and dried. And among the campfires and teepees that night, the tribes, no doubt, celebrated the conclusion of a successful hunt with songs and dance. They would have enough food to make it through winter.

As the stars spread across the sky, Hollis crawled into his sleeping bag and thought about this ancient place. He could hear their songs. He could smell the blood, the bile and the death. He could sense the old dreams, the aspirations of a hunting people who depended on jumps to harvest all of their needs.

The West contains many such places, most of them forgotten, paved, fenced or plowed. But all that once was is permanently preserved in the strokes of Hollis’ paintbrush – and in the painting that now hangs on my wall.

Canyon Shepherd, oil on panel, 12” x 16”

Canyon Shepherd, oil on panel, 12” x 16”

Canyon Ribbons, oil on panel, 14” x 18”

Canyon Ribbons, oil on panel, 14” x 18”

Photo by Marty Asplin

Photo by Marty Asplin

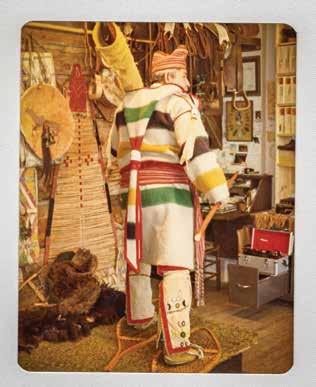

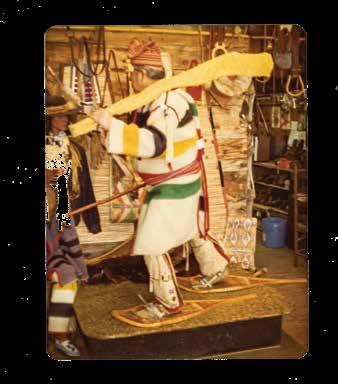

The subarctic region of North America sustained a network of Indian tribal groups in what is now known as Canada and Alaska. The finest and most abundant sources for the fur trade from 1600 to 1850 came from these regions. These groups were some of the first in America to trade with the established European companies of England and France. This figure represents a member of one of those groups — a hearty Athabascan trapper laden with his trade tools for the pursuit of winter pelts. — HW

Photos by the artist

Photos by the artist

Utah’s Bingham Canyon Mine is visible from space, a man-made gash in the Earth that’s nearly a mile deep and 2½ miles wide. Mining for gold and silver began here in the early 1900s, and miners have slowly dug deeper and wider over the years, but copper has been their primary pursuit.

Copper is combined with tin, zinc or manganese to make bronze, an ancient metallurgical recipe dating back nearly 5,000 years. It was mankind’s most significant technological achievement at the time, allowing people for the first time to make metal weapons and tools.

Oil comes from the earth too, and the energy boom of the 1970s resulted in money flooding into the Western art market. The wildcatters identified with its masculine, individualistic themes, and artists, like all entrepreneurs in wellfunctioning markets, responded in kind.

The money attracted opportunists into the Western art market in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and Hollis was troubled by what he saw. To him, they were carpetbaggers, people who’d come to capitalize on the good times, and who didn’t fully appreciate or understand what he and his community of artists were trying to do. They were simply there to make a quick buck at the expense of others before moving on to other lucrative opportunities elsewhere.

Thus, a battle began to brew in the late 1980s and early 1990s over the future of the National Academy of Western Art. It pitted newcomers against the core group of artists who had formed the organization in 1973, and whose purpose was to maintain the highest standards. In other words, NAWA had been very selective about who they let in, and more importantly, who they kept out.

The efforts of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, led by then-Director Dean Krakel, wanted NAWA opened up to allow more artists into the organization. There was money to be made, the markets were booming and there was no reason to place artificial restrictions on tapping into its growth.

Hollis and a group of his colleagues disagreed, and thus began a bitter controversy that nearly tore NAWA apart.

“If bent on the idea of displaying more ‘saleable’ work along with the NAWA exhibit, let it be hung in the gift shop where it belongs so as not to taint the creations of those to whom art is a religion, not a circus!”

Hollis wrote to NAWA. “These past, present and future works must be more than products. The purpose of a circus is to entertain and serve popcorn. The purpose of an institutional art show should be to enlighten and serve dignity.

“We must not let this group of select NAWA artists become an endangered species; it may be the only hope left for a legacy that could rise above all others,” he continued. “If we were in this chosen profession for profit only, we would sell art supplies instead of using them.”

Krakel did not relent. Plans to change NAWA –in spite of the artist’s demands – moved forward. Hollis, who’d grown up poor and lived, and nearly died, pursuing his art, commented later: “I’ve always had a way of committing economic suicide,” he conceded.

The artist never again won the Prix de West, although Welcome Sundown, created from copper, tin and money, still stands guard at the institution’s front entryway.

An artistic achievement matched by few others, Hollis remains one of just seven repeat winners of the NAWA Prix de West Purchase Award. He is also one of just a handful of NAWA artists to have received more than 10 awards since the organization’s 1973 inception. A testament to his versatility, he did so in both drawing and sculpting.

“If we were in this chosen profession for profit only, we would sell art supplies instead of using them.”

Experience the artistic legacy of Hollis Williford, from his boyhood home in Texas to his adventures in the wilds. From an obscure childhood, he rose to become one of the 20th century’s preeminent American artists. He stood for freedom and the power of individuality. His life exemplifies how anyone — no matter their economic condition — can pursue any dream and overcome any obstacle.