2 minute read

tobe

Hanging in my home is the down payment for this book, what I consider to be one of Hollis’ greatest paintings. The subject is a herd of bison spread out among the sagebrush at the base of Blacktail Butte near Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

It’s a late-summer day. The grass is mature and yellow. The calves, half grown, graze near their mothers. And the bulls, in an agitated, mid-rut state with their tails twisted and raised, have gathered at the edge of the herd.

At one time, 60-80 million of these animals roamed America’s mountain valleys and Great Plains. Fossil records indicate they occupied these lands for nearly 175,000 years, yet in less than 20 of those years — from about 1865-1885 — Anglo-Americans completely decimated their population. It was among the swiftest and largest near-extinctions of warm-blooded animals in the history of the world.

There were many motivations for killing the bison, but ranking most prominently was a desire to eradicate the primary food source for the Plains Tribes. Once the bison were gone, so too would be the Native Americans.

So Hollis came west, to trace the old trails, to capture with pen and brush what it must have looked like to have arrived in such a place where the bison once roamed free.

He understood the instinctual drive to be, to exist, to live. He knew the fragility of it all, that life was placed precariously on the tip of a spear and could end or change completely in a moment. Even the mighty bison could be felled and destroyed.

To inspire his work, he went directly to the source. He traveled to see the herds himself. He wanted to see the mountains and the streams as they really were. He scoured over old artifacts, pored over original writings.

One such source was the Voyage of Discovery of 1803-1806, Lewis and Clark’s exploration of the Louisiana Purchase. In their journal, they described things that will never be seen again — the native encampments along the rivers, the cottonwood forests and undulating plains teeming with flora and fauna, and the immense herds of bison that stretched as far as they could see.

The explorers eventually found the sources they were looking for — the headwaters of the Missouri River, a place now called Three Forks in Montana — where the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin rivers converge to form the longest river and the largest watershed in the United States.

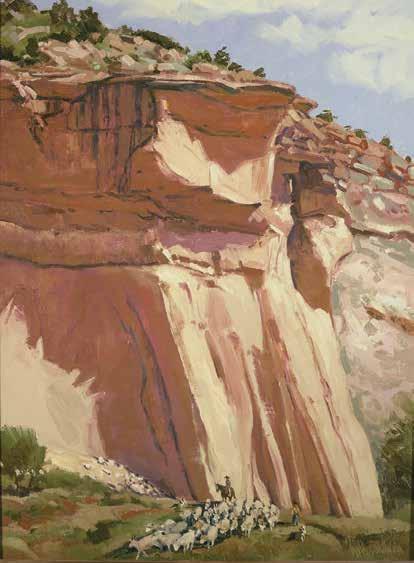

Inspired to follow in the explorers’ footsteps, Hollis camped along the banks of the Madison in the late 1970s. He came to see the Buffalo Jump, a rocky cliff that rises from the valley floor. The ancient hunters had once driven bison off its edge to kill their prey in masses.

Beneath the cliff, the hunters skinned and butchered the bison with flint knives. The meat was sliced and dried. And among the campfires and teepees that night, the tribes, no doubt, celebrated the conclusion of a successful hunt with songs and dance. They would have enough food to make it through winter.

As the stars spread across the sky, Hollis crawled into his sleeping bag and thought about this ancient place. He could hear their songs. He could smell the blood, the bile and the death. He could sense the old dreams, the aspirations of a hunting people who depended on jumps to harvest all of their needs.

The West contains many such places, most of them forgotten, paved, fenced or plowed. But all that once was is permanently preserved in the strokes of Hollis’ paintbrush – and in the painting that now hangs on my wall.