The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society

The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society

A Tale of Two Palmettos: the Foundation of Ecosystems l Age-old Palms on Ancient Ridges l Saw Palmetto Flowers are a Biodiversity Bonanza

Why, you may a sk, devote a n entire i ssue of Palmetto to plants a s common a s palmettos? Common t hey may be, but t hey a re a lso far more a ncient a nd integral to t he ecosystems t hey inhabit t han many would g ive t hem credit for. Furthermore, t hey have fascinating attributes t hat help explain t heir survival a nd success – attributes t hat deserve to be better k nown.

Not long ago I was poking through a box of cast-off botany books and came across The Saw-Palmetto–Serenoa repens, by John K Small, a reprint from the 1926 Journal of the New York Botanical Garden This musty booklet started me thinking about the ubiquitous palmetto, a plant that is generally underappreciated and is routinely bulldozed w ith abandon throughout the state. About saw palmetto, Small w rites, “While the first description and naming of the species is usually attributed to André Michaux in 1803, it seems clear that in reality it should date from about a decade earlier. While William Bartram was on his way to Florida, he observed the palms growing on Saint Simon Island, Georgia.” Bartram called the plant Corypha repens. In his book Florida Ethnobotany, Dan Austin states that Bartram coined the common name “saw palmetto.” A s to the source of the present Latin name, Austin w rites, “When I first saw the scientific name of the saw palmetto, Serenoa repens, I thought it unusually appropriate. The genus appeared to be based on “serene” a nd t he species repens means reclining. How poetic it seemed for plants with t heir stems lying peacefully on t he g round. Then, I learned t hat t he genus was created to honor Sereno Watson, an introverted a ssistant to Asa Gray at Harvard University. So much for poetry.” Small also mentions the reclining habit of saw palmetto and speculates on its past. “The saw-palmetto is typically a prostrate plant. Ages ago it may have been erect. In its early existence it may have been a more tender plant and then for the purpose of selfpreservation it may have come to lay its stem prostrate and anchor it w ith numerous roots so as to be more immune from fire and other destroying conditions, just as many other plants seem to have done, particularly in fire-swept regions.” An accompanying figure shows the back dune near Mosquito Inlet, looking east from “Green Mound” a midden on the Halifax R iver. The scene shows a sea of “alligator backs” or saw palmetto trunks blackened and curving over the sands of the dune after a fire.

On his blog Treasure Coast Natives, George Rogers points out some of the more interesting attributes of saw palmetto: “The roots have air channels, hollow pipes conducting air who knows how deep into the underground. Down-bound air channels are common in marsh plants in suffocating waterlogged soil...but saw palmetto is the only example of rooty air ducts I know in a scrub-dweller. The species, however, is not restricted to scrub. Maybe the air ducts allow the roots to go extra-deep in the seasonally soggy-to-waterlogged pine woods soils where saw palmetto rules. The roots need study by somebody with a shovel and a strong back.”

Palmetto longevity has been studied and the plants have been found to be surprisingly long-lived. After reading “Age-old Palms

on Florida’s Ancient R idges” beginning on page 8, hopefully you'll agree we short-lived humans have a thing or two to learn about caring for the planet we live on and the species that inhabit it.

Austin, Daniel F. 2004. Florida Ethnobotany. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Small, John K. 1926. The Saw-Palmetto – Serenoa repens. Reprinted without change of paging, from Journal of the New York Botanical Garden 27: 193-202. 1926. Online at: http://mertzdigital.nybg.org/cdm/ref/collection/p9016coll22/id/323

Treasure Coast Natives. https://treasurecoastnatives.wordpress.com/2016/09/30/ saw-palmetto-needs-its-saw-sharpened/

For more on Sereno Watson, visit http://botany.si.edu/colls/expeditions/expedition_page.cfm?ExpedName=1

The Florida Native Plant Society Annual Conference will be held in Westgate River Ranch Resort, River Ranch, Florida, May 17-21, 2017. The Research Track of the Conference will include presented papers and a poster session on Friday, May 19, and Saturday, May 20.

Researchers are invited to submit abstracts on research related to native plants and plant communities of Florida including preservation, conservation, and restoration. Presentations are planned to be 20 minutes in total length (15 min. presentation, 5 min. questions).

Abstracts of not more than 200 words should be submitted as a MS Word file by email to Paul A. Schmalzer at paul.a.schmalzer@nasa.gov by February 1, 2017. Include title, affiliation, and address. Indicate whether you will be presenting a paper or poster.

The Florida Native Plant Society maintains an Endowment Research Grant program for the purpose of funding research on native plants. These are small grants ($1500 or less), awarded for a 1-year period, and intended to support research that forwards the mission of the Florida Native Plant Society, which is "to promote the preservation, conservation, and restoration of the native plants and native plant communities of Florida."

FNPS Conservation Grants support applied native plant conservation projects in Florida. These grants ($5000 or less) are awarded for a 1-year period. These projects promote the preservation, conservation, or restoration of rare or imperiled native plant taxa and rare or imperiled native plant communities. To qualify for a Conservation Grant, the proposed project must be sponsored by an FNPS Chapter.

Application guidelines and details are on the FNPS Web site (www.fnps. org), click on ‘Participate/Grants and Awards’. Questions regarding the grant programs should be sent to info@fnps.org.

Application deadline for the 2017 Awards is March 3, 2017. Awards will be announced at the May 2017 Annual Conference at the Westgate River Ranch Resort, River Ranch, Florida. Awardees do not have to be present at the Conference to receive award.

Officers

President ..............................Catherine Bowman

Past President.......................Anne Cox

Vice President, Finance .........Devon Higginbotham

Vice President, Administration ...Lassie Lee

Treasurer ..............................Kim Zarillo

Secretar y ..............................Martha Steuart

Committee Chairs

Communications ...................Shirley Denton

Conference ...........................Marlene Rodak

Conservation ........................Juliet Rynear

Education .............................Nicole Cribbs

Finance ................................Devon Higginbotham

Land Management Partners ....Danny Young Landscape Volunteer Needed

Membership .........................Jonnie Spitler

Policy & Legislation ...............Eugene Kelly

Science ................................Paul Schmalzer

Council of Chapters

Chair.....................................David Feagles

Vice Chair .............................Donna Bollenbach

Secretar y ..............................Nicole Zampieri

Directors-at-Large

Ina Crawford

Peter Rogers

Winnie Said

To contact board members: Visit www.fnps.org or write care of: FNPS PO Box 278, Melbourne, FL 32902-0278

Society Services

Administrative Services ........Cammie Donaldson

Director of Development .......Andy Taylor

Editor, Palmetto .....................Marjorie Shropshire

Editor, Sabal minor ................Stacey Matrazzo

Executive Assistant ...............Juliet Rynear

Social Media .........................Donna Bollenbach

Webmaster ...........................Paul Rebmann

Palmetto

Editor: Marjorie Shropshire Visual Key Creative, Inc. pucpuggy@bellsouth.net l (772) 285-4286

Make a difference with FNPS

Your membership supports the preservation and restoration of wildlife habitats and biological diversity through the conservation of native plants. It also funds awards for leaders in native plant education, preservation and research.

l Full-time student ...............$ 15

l Individual ..........................$ 35

l Household .........................$ 50

l Supporting ........................$ 100

l Non-profit or Business ......$ 150

l Patron ...............................$ 250

l Gold ..................................$ 500

l Sustaining .........................$ 10/monthly

To provide funds that will enable us to protect Florida's native plant heritage, please join or renew at the highest level you can afford.

To become a member, contact your local Chapter Representative, call, write, or e-mail FNPS, or join online at www.fnps.org

The purpose of the Florida Native Plant Society is to conserve, preserve, and restore the native plants and native plant communities of Florida.

Official definition of native plant:

For most purposes, the phrase Florida native plant refers to those species occurring within the state boundaries prior to European contact, according to the best available scientific and historical documentation. More specifically, it includes those species understood as indigenous, occurring in natural associations in habitats that existed prior to significant human impacts and alterations of the landscape.

Follow FNPS online:

Blog: http://fnpsblog.blogspot.com/ Facebook: www.facebook.com/FNPSfans Twitter: twitter.com/FNPSonline

LinkedIn: Groups, Florida Native Plant Society

(ISSN 0276-4164) Copyright 2017, Florida Native Plant Society, all rights reserved. No part of the contents of this magazine may be reproduced by any means without written consent of the editor. Palmetto is published four times a year by the Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS) as a benefit to members. The observations and opinions expressed in attributed columns and articles are those of the respective authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views of the Florida Native Plant Society or the editor, except where otherwise stated. Editorial Content

We welcome articles on native plant species and related conservation topics, as well as high-quality botanical illustrations and photographs. Contact the editor for guidelines, deadlines and other information.

4 A Tale of Two Palmettos: The Foundation of Ecosystems

What features of p almettos f acilitate t heir s uccess i n environments w ith nutrient-impoverished soils, f requent fi res, a nd s easonal d roughts? T he a nswers l ie i n t heir g rowth forms, p atterns of g rowth, a nd r eproductive r esponses. A rticle by Warren G. Abrahamson.

8 Age-old Palms on Florida’s Ancient Ridges

The s aw p almetto i s a mong t he S outheast’s most recognized plants, yet few who recognize saw palmetto appreciate its ecological importance to plant communities or r ealize t hat s aw p almettos c an s urvive to b ecome t housands of years old. Ar ticle by Warren G. Abrahamson.

12 Saw Palmetto Flowers are a Biodiversity Bonanza

At A rchbold Biological Station ( ABS) 311 s pecies of i nsects h ave b een documented v isiting t he flowers of s aw p almetto. But t he A BS study of s aw p almetto flowers a lso h ighlights a much w ider phenomenon: flowers i n n atural h abitats s upport t he s pecialized e cological r oles of hundreds of s pecies of busy i nsects. Article by Mark Deyrup.

Conservation Grants are funded through targeted donations from individuals and chapters. Please help support important projects throughout Florida that promote the preservation, conservation, and restoration of Florida’s rare or imperiled native plant taxa and rare or imperiled native plant communities. A list of Conservation Grant awards and project updates is available on our website: http://www.fnps.org/what-we-do/conservation_grants

“...The wilderness country looked very dismal, having no trees, but on sand-hills covered with shrubby palmetto, the stalks of which were prickly, so there was no walking amongst them...”

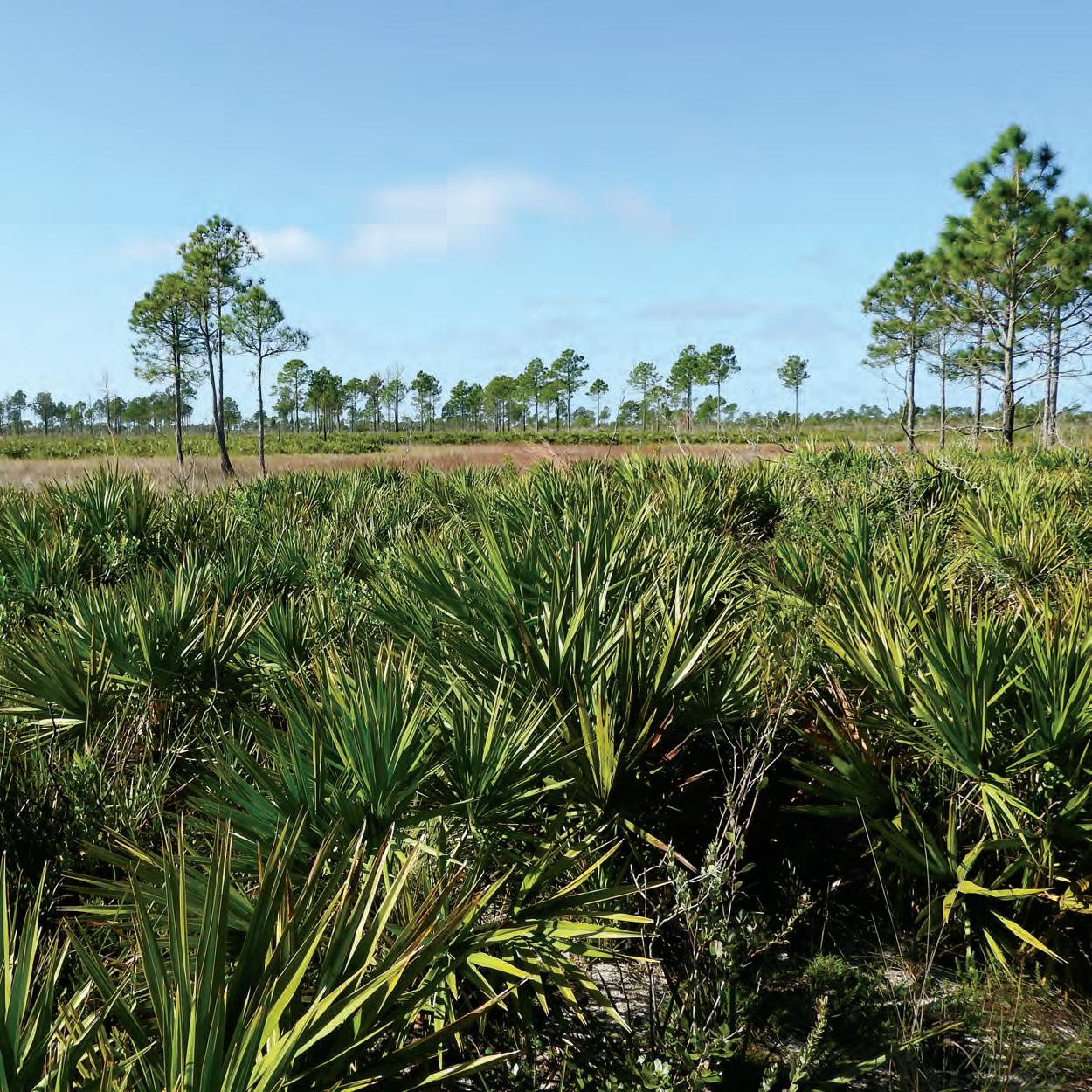

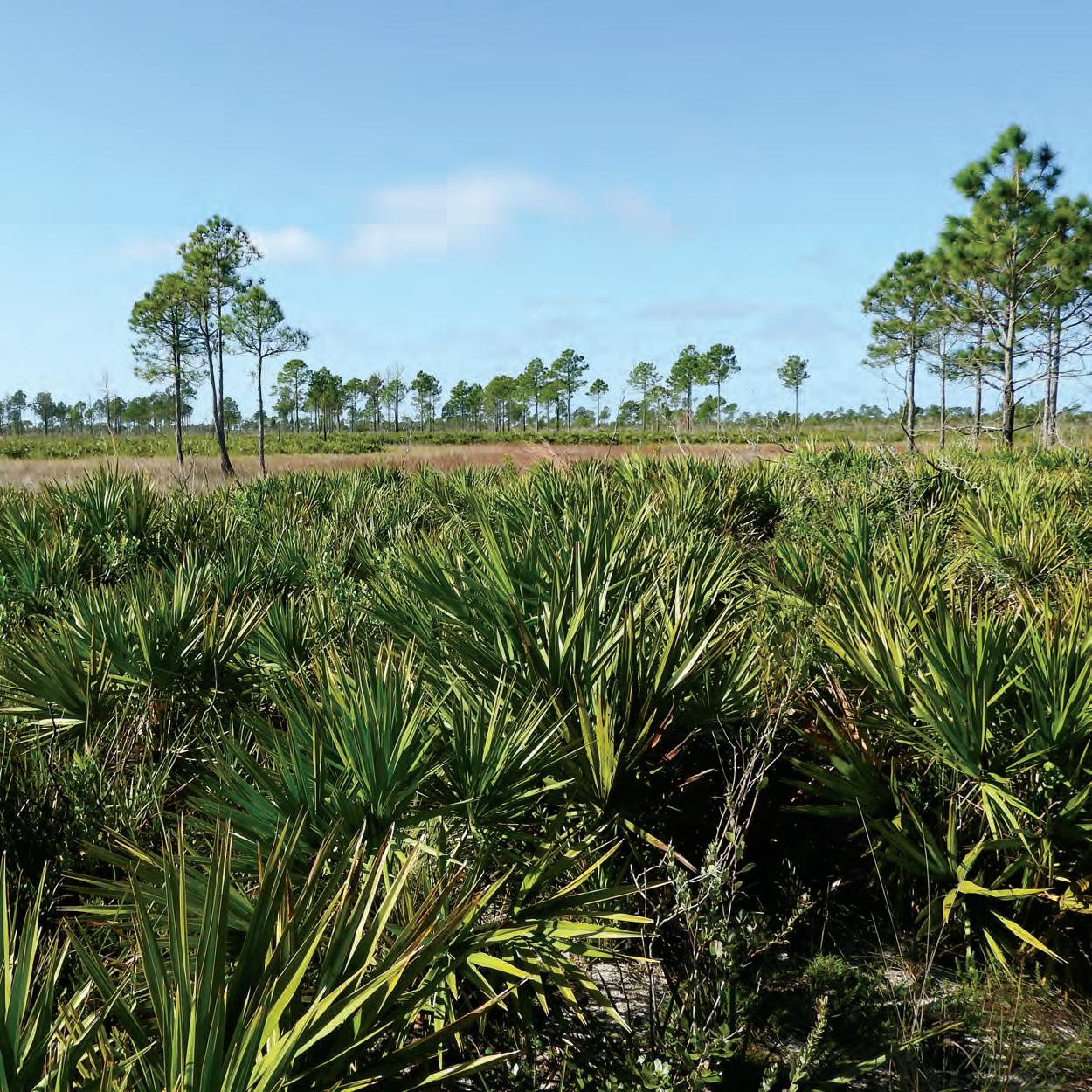

The Q uaker merchant Jonathan D ickinson w as describing t he foreboding coastal s aw p almetto (Serenoa repens) landscape following his 1696 shipwreck near his namesake state park on Florida’s Atlantic coast. Held for nearly a month by the native Jobe people, Dickinson and his companions did not enjoy some foods in their keepers’ diet –particularly the fruits of saw palmettos. “...the Cassekey [ Jobe k ing] ordered M aster Joseph K irle, S olomon C orsson, my w ife a nd me, to s it upon t heir c abbin to e at our fi sh, a nd t hey gave u s s ome of t heir berries to eat; we tasted them, but not one a mongst u s could s uffer t hem to stay in our mouths, for we could compare t he t aste of t hem to nothing else but r otten c heese steep’d in tobacco juice”(Small 1926).

After dissecting hundreds of saw palmetto f ruits to determine t heir energy, mineral element, nutrient, a nd water contents, my w ife Chris a nd I can empathize w ith Dickinson a nd his companions’ inability to eat t he repugnant saw palmetto f ruits. Yet, t hese f ruits so repulsive to humans a re favorites among raccoons, opossums, foxes, whitetail deer, black bears, feral hogs, gopher tortoises a nd others (Halls 1977, Bennett a nd Hicklin 1998, Tanner et a l. 1999, Dobey et a l. 2005). There’s a good reason t hey a re favorites. Fruits of t he w idespread saw palmetto a re a high-quality w ildlife resource w ith a n energy content (per dry mass) a nd level of total digestible nutrients (i.e., digestible proteins, fats, carbohydrates a nd fiber) comparable to turkey oak acorns (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 1989, L ayne a nd Abrahamson 2010). Compared to saw palmetto, t he f ruits of t he co-occurring but narrow Florida-endemic scrub palmetto (Sabal etonia) contain less energy a nd total digestible nutrients but more fiber. Given their taste, I’ll never replace the blueberries or bananas on my breakfast cereal w ith palmetto drupes! My fascination w ith palmettos began in 1972 during my fi rst v isit to south-central Florida’s A rchbold Biological Station (ABS). The ubiquity of palmettos across t he landscape made me wonder what attributes enabled t heir t remendous success. Palmettos appeared to provide a matrix for t heir ecosystems. They a re what ecologists refer to a s “foundation species,” t hat i s, species t hat play major roles in structuring a community. So what features of palmettos facilitate their success in environments w ith nutrient-impoverished soils, f requent fi res, a nd seasonal droughts? The a nswers lie in t heir g rowth forms, patterns of g rowth, a nd reproductive responses.

The t hick, evergreen, heavily cutinized leaves of palmettos a re well designed to conserve water a nd nutrients (Tomlinson

1961), t wo resources often in short supply in sandy soils a nd during Florida’s dry seasons. Moreover, t he long-lived leaves of palmettos provide a n advantage over plants w ith short-lived leaves under nutrient-poor and low-light conditions. On a global level, plants of nutrient-impoverished and/or low-light habitats have longer living leaves t han plants of nutrient-rich or high-light environments. This i s because harsh environments force inherently slow rates of photosynthesis a nd high leaf construction costs (Kikuzawa a nd Ackerly 1999, Wright et a l. 2002, Wright et al. 2005, Poorter and Bongers 2006). Simply put, longer leaf life spans allow time to recoup leaf construction costs. Palmetto leaf life spans can be a s long a s 3½ years but life spans vary across regions, habitats, and even w ithin habitats. Saw palmettos g rowing on seasonally xeric, nutrient-impoverished sands at A BS exhibit longer leaf life spans [mean = 2.4 years (Abrahamson 2007)] than those growing in more mesic, coastalplain flatwoods [1.5-2.0 years (Hilmon 1969)]. Likewise, the leaves of A BS s crub p almettos h ave longer l ife s pans [mean = 2 .5 y ears ( Abrahamson 2007)] t han t hose o f d warf p almetto ( S abal minor) g rowing i n r ich a lluvial s oils [just o ver 1 y ear ( Hesse a nd C onner 1996)]. S crub p almetto’s l onger l eaf l ife s pan l ikely c ompensates f or c onstruction c osts o f i ts t hicker a nd p resumably m ore c ostly l eaves r elative t o d warf p almetto l eaves ( Zona 1990).

Leaf life spans of palmettos a re inversely related to light availability. Palmetto leaves survive longer in shaded environments compared to high-light environments at A BS. Average leaf life spans for palmettos of open-overstory fl atwoods, for example, a re 2.2 years, whereas life spans average 2.8 years in long-unburned, shaded sand pine scrub (Abrahamson 2007).

In addition, palmettos modify t heir leaf sizes according to light availability. We found t hat palmettos g rowing in nearly

closed-canopy sand pine scrub have the largest leaf blades, longest petioles, and greatest total leaf area, whereas the smallest leaf blades, shortest petioles, and least total leaf area a re associated with palmettos in open-canopy scrubby flatwoods. Palmettos compensate for reduced light availability w ith increased leaf a reas which intercept more light. Moreover, saw a nd scrub palmetto leaves differ in size w ithin t he same habitat. Scrub palmetto leaves a re larger; t hey survive longer; but have fewer leaves compared to saw palmettos. Depending on t he habitat a nd plant size, saw palmettos maintain 7-9 leaves while scrub palmettos retain only 3 -5 leaves (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2006, Abrahamson 2007).

The few, but l arge leaves of palmettos a re a n a nomaly a mong t heir neighbors t hat have numerous small leaves –t he t ypical a rrangement for plants of nutrient-impoverished a nd/or low-light habitats ( Ackerly et a l. 2002). Palmetto leaves a re roughly 10 t imes longer a nd have t wo to t hree orders of magnitude more a rea t han t he leaves of s ympatric plants ( Abrahamson 2007). Why a re t he leaves of palmettos so l arge?

The most l ikely e xplanation i s t he constraint imposed by t heir evolutionary past ( Ackerly 2004). Palms possess some of t he l argest leaves k nown, yet a mong palms, saw a nd scrub palmettos bear diminutive a nd few leaves (Tomlinson 1990, Z ona 1990, Henderson 2002) – a probable adaptation to t he nutrientpoor, seasonally xeric conditions. How can palmettos prosper in fi re-prone environments? When burned, palmettos g row new leaves w ith added urgency to quickly restore t heir leaf canopies (Hough 1965, Abrahamson 1984, Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2006). A s a consequence of t heir long leaf life spans a nd hence limited leaf turnover, recently burned palmettos have elevated numbers of leaves a nd g reater total leaf a reas compared to pre-burn levels. Canopies w ith additional leaves boost photoassimilate gains, which a id recovery of t he resources expended to regenerate leaves following fi re (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2006).

Furthermore, fi re stimulates palmetto r eproduction. We observed strong flowering by palmettos i n a n A BS s andhill following e ach of t hree successive fi res during a n 8 -year p eriod ( Abrahamson 1999) but s aw only l imited flowering during t he i ntervals b etween fi res. W hat i s it about fi re t hat produces t hese episodic r eproductive e vents a nd why do some, but not a ll, palmettos flower?

We non-destructively estimated t he mass of individual palmettos using a measure of crown size a nd t he number of living leaves (Abrahamson 1995, 1999) a nd we tested experimentally whether increased nutrient availability, enhanced light availability, leaf loss, or a combination of t hese factors a ffects palmetto reproduction (Abrahamson 1999). The study results were unmistakable. Mass ( hence t he amount of stored resources) determines whether a palmetto flowers a nd how much it flowers, a pattern similar to t hat of other plants (Clark a nd

Clark 1987, Thompson et a l. 1991, Chazdon 1992, K ettenring et a l. 2009). A s expected, palmettos t hat flower occur under more open canopies t han t hose t hat don’t flower. Clearly both size a nd light availability a re factors influencing flowering. But most telling wa s t he fi nding t hat leaf loss i s a powerful flowering stimulant if t he palmetto i s sufficiently large. Even t hough t he soils in palmetto habitats have increased nutrient availability following fi re (Schafer a nd Mack 2010) fertilization did not encourage palmetto flowering. The t rigger t hat turns on reproduction in both saw a nd scrub palmetto i s leaf loss (Abrahamson 1999). Clearly saw a nd scrub palmettos share many f undamental adaptations to t heir environment but t here a re differences. For example, in spite of saw palmetto’s ability to have net photosynthetic gains under low light a nd relatively high gains under high light (DeMoraes 1980), saw palmettos require more light t han do scrub palmettos to initiate flowering (Abrahamson 1999). In addition, saw palmettos produce higher quality f ruits a nd t hey produce far g reater quantities of f ruits t han do scrub palmettos in large part because scrub palmettos a re considerably smaller on average t han saw palmettos (Abrahamson 1995, 1999).

Plants of fi re-prone Florida ecosystems evolved w ith summer, wet-season fi res. Yet today a nthropogenic fi res occur during a ny season, often in t he w inter, dry season. When burned during t he dry season, saw a nd scrub palmettos break dormancy to produce new leaves but t he t wo palmettos differ markedly in t heir reproductive responses to w inter fi res. Saw palmettos produce flowers t hat a re a synchronous w ith flowers of summer-burned or unburned saw palmettos, which results in reduced f ruit set. In contrast, w inter-burned scrub palmettos remain vegetative t hrough t he fi rst g rowing season following fi re a nd initiate flowers t hat a re synchronous w ith unburned scrub palms in t he second g rowing season (Abrahamson 1999).

Growth rates of palmettos a re markedly slowed by t he nutrient-impoverished, droughty, fi re-prone environments in which t hey g row. Adult saw palmettos g row very slowly (≈2 cm/ year) in t heir native habitats (Hilmon 1969, Abrahamson 1995) a nd t heir seedlings require many decades to a century just to reach modest size (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2009). But fortunately for ecological restoration saw palmettos can g row considerably faster in disturbed sites such a s former citrus g roves (Foster a nd Schmalzer 2012).

Given slow rates of g rowth, persistence i s essential if palmettos a re to reach reproductive size. But i s persistence a n option for palmettos in t he face of repeated fi re a nd drought? Palmetto adults a nd seedlings show a stonishing persistence a nd tolerance. We began following marked adults of saw a nd scrub palmettos in 1980 a nd by 1991 we were a nnually evaluating g rowth a nd survival in 940 adults a nd 178 seedlings. The severe a nd prolonged drought of 1999-2001 t hat a ffected Florida a nd t he southeastern USA provided a unique opportunity to measure t he impacts of drought on palmettos. Then, a n intense,

dry-season w ildfire at t he height of t he drought a llowed us to w itness t he combined effects of severe drought a nd a n extremely hot w ildfire on a ll marked seedlings a nd a subset of our marked adults (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2002, 2009).

All marked populations of adult palmettos lost mass during the drought but remarkably, the survivorship of adult palmettos was little affected by drought or by the combination of drought and fire (Abrahamson and Abrahamson 2002). No adult saw palmettos died and only t wo smaller-than-average adult scrub palmettos died, one of which was impacted by the w ildfire. Seedlings fared less well during the drought and fire, yet a stoundingly 70% of the 1989 flatwoods cohort and 55% of the 1989 scrubby flatwoods cohort survived through the preceding 13 years, drought, and w ildfire. A s of 2008 (after 19 years), 57% of the flatwoods cohort and 35% of the scrubby flatwoods cohort continued to survive. But after 19 years, the flatwoods seedling cohort averaged only 17 cm in height and the scrubby flatwoods cohort only 14 cm. (Abrahamson and Abrahamson 2009).

Slow plant g rowth and plant longevity (persistence) are often linked ( Johnson and Abrams 2009), which raises the question of just how long slow-growing palmettos can live. Saw palmettos, which are highly clonal, have amazing longevity, living literally thousands of years (Takahashi et al. 2011, 2012). The accompanying article in this issue “Age-old Palms on Florida’s A ncient R idges” tells the fascinating story of how we aged several clones of saw palmettos by coupling genetic fingerprinting technology and mathematical modeling w ith field studies (Abrahamson 2016). We suspect that the non-clonal scrub palmetto also has impressive longevity g iven its slow g rowth but this needs study. Saw a nd scrub palmettos share many essential attributes, so it’s no surprise t hat t hey co-occur in many Florida habitats. Yet, t heir fi ne differences should generate divergence in how t hey use t hose habitats. Indeed, sampling of t heir abundances across A BS habitats documented t hat saw palmetto reaches its highest a nd lowest abundance in fl atwoods a nd sandhills, respectively. Scrub palmetto, on t he other hand, i s infrequent in fl atwoods but abundant in sand pine scrub and sandhills (Abrahamson 1995). When we examined t he distribution of individual palmettos, we discovered in fl atwoods, for example, t hat saw palmetto i s tolerant of both poorly drained a nd betterdrained microsites while scrub palmetto i s clumped in betterdrained microsites. Furthermore, neighboring plants differed for t he t wo palmettos. Scrub palmettos had nearly t wice a s many fetterbush (Lyonia lucida) plants and other scrub palmettos a s neighbors a nd a n order of magnitude more sand live oaks (Quercus geminata) a s neighbors t han did saw palmetto. The competitive interactions of t he t wo palmettos a re at least partially ameliorated by microsite a nd neighborhood differences. Palmettos a re beautifully adapted to t he r igors of t he environment in which t hey evolved. But today’s world i s different t han t he evolutionary past due to a nthropogenic influences.

The evolutionary fi re regimes of palmettos included late-spring a nd summer fi res, but today t hey a re often burned by w inter, dry-season fi res. Fire-return intervals, including a n absence of fi re, a re unlike t hose of t heir evolutionary past. Palmettos a re experiencing a ltered hydroperiods due to drainage a nd water use. Climate change w ith a lteration of temperatures a nd precipitation i s likely to challenge species, including palmettos, unable to redistribute in a highly f ragmented landscape. Even t he uncontrolled harvesting of saw palmetto f ruits f rom natural communities for pharmaceutical products has consequences. The strong market for saw palmetto f ruits has generated poaching f rom federal, state, a nd private lands, reducing f ruit availability for w ildlife a nd plant recruitment. The long-term persistence of palmettos i s t hreatened by human influences.

Dr. Warren G. Abrahamson is an evolutionary ecologist whose research interests include Florida vegetation ecology, conservation biology, and plant-animal interactions of goldenrods, gall insects, and natural enemies as well as of oaks and gall wasps. He is a Research Associate at the Archbold Biological Station, Venus, FL, and is the David Burpee Professor of Plant Genetics Emeritus at Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA.

I sincerely thank Chris Abrahamson, Catherine Blair, Mark Deyrup, John Fitzpatrick, Ann Johnson, James Layne, Ken McCrea, Eric Menges, Paul Schmalzer, Hilary Swain, Chet Winegarner, Mike Wise, and numerous Bucknell students and Postdoctoral Fellows for their help and/or discussion. The Archbold Biological Station and Bucknell University supported the studies that produced much of the findings summarized here.

Abrahamson, W. G. 1984. Species responses to fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge. American Journal of Botany 71: 35-43.

Abrahamson, W. G. 1995. Habitat distribution and competitive neighborhoods of two Florida palmettos. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122: 1-12.

Abrahamson, W. G. 1999. Episodic reproduction in two fire-prone palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Palmae). Ecology 80: 100-115.

Abrahamson, W. G. 2007. Leaf traits and leaf life spans of two xeric-adapted palmettos. American Journal of Botany 94: 1297-1308.

Abrahamson, W.G. 2016. Age-old palms on Florida's ancient ridges. The Palmetto 33: 4-7, 15.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 1989. Nutritional quality of animaldispersed fruits in Florida sandridge habitats. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 116: 215-228.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2002. Persistent palmettos: effects of the 2000-2001 drought on Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia. Florida Scientist 65: 281-292.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2006. Post-fire canopy recovery in two fire-adapted palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Arecaceae). Florida Scientist 69: 69-79.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2009. Life in the slow lane: Palmetto seedlings exhibit remarkable survival but slow growth in Florida's nutrient-poor uplands. Castanea 74: 123-132.

Ackerly, D. D. 2004. Adaptation, niche conservatism, and convergence: comparative studies of leaf evolution in the California chaparral. The American Naturalist 163: 654-671.

Warren G. Abrahamson

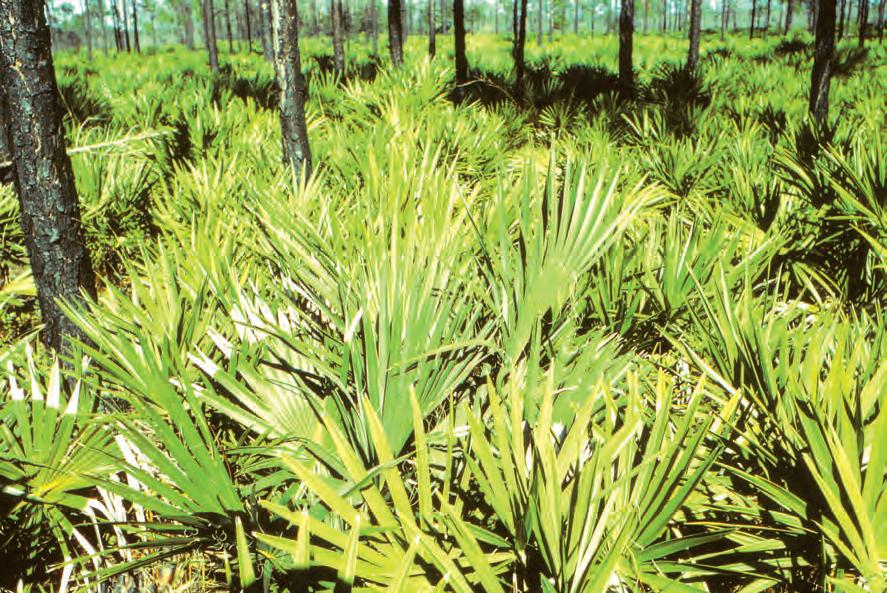

The dwarf palm k nown a s saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) occurs in most of Florida’s natural upland plant communities. With horizontal stems t hat look something like a n a lligator’s back (Figure 1) because of persistent leaf bases a nd large, palmate leaves (Henderson et a l. 1995, Henderson 2002), t he saw palmetto i s among t he Southeast’s most recognized plants. Yet few who recognize saw palmetto appreciate its ecological importance to plant communities or realize t hat saw palmettos can survive to become t housands of years old!

The individuals of saw palmetto t hat we see a re most often a small f raction of a much larger palmetto clone composed of genetically identical saw palmettos. A s saw palmettos spread a long t he g round v ia t heir horizontal stems, t heir stems often fork in response to multiple sprouts, damage f rom fi re, or mechanical i njury to form additional stems ( Figure 2). This c lonal t rait f acilitates t he r emarkable longevity of s aw p almettos t hat c an attain 5,000 a nd more years of a ge ( Takahashi et a l. 2011, Takahashi et a l. 2012).

But you should wonder: “How c an we determine t he a ge of palms g iven both t heir l ack of wood a nd absence of a nnual g rowth r ings?” W hile it’s r elatively straightforward to a ge woody t rees such a s oaks, h ickories, a nd m aples t hat l ay down a nnual g rowth r ings, e stimating longevity of plants t hat l ack a nnual g rowth r ings a nd t hose t hat l ive i n a seasonal t ropical environments presents a n appreciable challenge. My l aboratory g roup at Bucknell University took up t he challenge to e stimate a ges of s aw palmettos a nd to address additional questions about s aw palmetto a s well a s t he scrub palmetto (Sabal etonia) b ecause of t he i mportance of palmettos to t he ecology a nd conservation of vegetation a ssociations t hroughout Florida a nd t he southeastern USA coastal plain.

Our quest to understand palmetto ecology a nd survivorship began in 1980 when my w ife Chris a nd I t agged 120 saw palmettos a nd 120 scrub palmettos t hat g rew at t he A rchbold Biological Station (ABS) near t he southern end of t he L ake Wales R idge (LWR). In subsequent years, my Bucknell University students a nd I t agged a n additional 700 saw a nd scrub palmettos a nd marked 178 palmetto seedlings. Through t he years, our censuses a nd measurements of t hese palmettos generated insights into t he distribution of palmettos across vegetation a ssociations (Abrahamson 1995), t he episodic flowering of palmettos following fi re (Abrahamson 1999), t heir remarkable ability to w ithstand drought a nd fi re (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2002, Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2006), t he longevity of t heir leaves (Abrahamson 2007), t he incredible survivorship a nd slow g rowth of palmetto seedlings (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2009), a s well a s t he data necessary to estimate t he ages of saw palmetto clones (Takahashi et a l. 2011, Takahashi et a l. 2012).

Estimating t he ages of saw palmetto required data f rom three separate approaches. (1) Long-term field studies of tagged s aw p almettos a llowed u s to determine t heir stem g rowth r ates, w hich told u s how f ast t heir horizontal stems move t hrough s pace ( Abrahamson 1995). (2) L aboratory studies using A mplified Fragment L ength Polymorphisms ( AFLP), a genetic “fingerprinting” method that could accurately distinguish saw and scrub palmettos (including their seedlings) and importantly could differentiate the individuals that belonged to different clones. Finally, we used (3) M inimum Branching Trees ( MBT), a m athematical model t hat enabled u s to c alculate t he t ime necessary to produce t he a rrangement of the saw palmettos that were parts of an identified clone (Abrahamson 1995, Takahashi et al. 2011, Takahashi et a l. 2012). With a goal of e stimating longevity of plants t hat potentially live a very long t ime, we needed a location w ith sufficient long-term stability t hat plants w ith t he potential to live a long t ime could realize t heir p otential. A BS on Florida’s L ake Wales R idge w as a n ideal location g iven its elevation above sea level a nd t he r elatively stable long-term climate of t he Florida peninsula. For most of t he Earth’s geological h istory, o cean levels h ave b een considerably h igher t han current sea level (Muller et a l. 2008). For example, during the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene ocean shorelines were 50 meters higher than today’s shorelines – a level that inundated substantial portions of t he Florida peninsula ( Webb 1990). Florida’s sand r idges, including t he L ake Wales a nd Brooksville R idges, offered refugia for terrestrial plants a nd a nimals. A s a consequence, t he LWR e xhibits r emarkable endemism today ( Deyrup a nd E isner 1993, Stap 1994). W hile northern glaciated and near-glaciated regions experienced dramatic plant community changes during the

past 50,000 years ( Jacobson, Jr. et a l. 1987), Florida had more limited climatic fluctuations during t he same t ime period ( Watts a nd Hansen 1994). Times of higher precipitation produced pinedominated forests on the LWR while during more arid times, oak savannas and grasslands were common. The modern vegetation of the LWR has been in place for 5,000 years. This climatic history

set a stage t hat h as b een conductive to t he s urvival of longlived pl ants (Grimm et a l. 1993).

Our ABS-based field studies established a number of attributes shared by saw and scrub palmetto, but we also identified important differences in the two palmettos. The patterns of stem growth in saw palmettos produce considerable clonal propagation. Plant ecologists have a specific term, “genet,” to refer to clonal plant colonies. A genet is a group of genetically identical plants growing in a given location that have originated vegetatively from a single ancestor. The genet is composed of individuals that plant ecologists refer to as “ramets.” A ramet i s a physiologically distinct organism that may or may not be connected physically to other members of a genet. Thus, most often the plants of saw palmetto that we see are ramets that a re part of a clonal colony or genet. In sharp contrast to saw palmetto, scrub palmetto with its corkscrew, S-shaped subterranean stem is non-clonal and does not grow horizontally in space (Corner 1966, Abrahamson 1995, Takahashi et al. 2011). While the clonal growth of saw palmetto coupled w ith its horizontal stem growth allow us to estimate its longevity, the longevity of non-clonal scrub palmetto cannot be estimated with the methods that work so conveniently with saw palmetto. Saw palmetto ramets g row very slowly (ranging f rom 0.6 to 2.2 cm/year) in t he nutrient-poor sands of t he LWR but t heir g rowth rates differ across years a nd among vegetation a ssociations (Abrahamson 1995). For example, saw palmettos in A BS fl atwoods g rew faster t han t hose g rowing in scrubby fl atwoods (i.e., oak scrub). Because t he saw palmettos t hat we sampled for clonal spread a nd longevity lived in scrubby fl atwoods, we used t he 4 -year mean stem g rowth rate of 0.88 cm/year t hat wa s based on 60 saw palmettos t hat occurred at t hree A BS scrubby fl atwoods sites (Abrahamson 1995, Takahashi et a l. 2011).

Using mean stem g rowth rate, we could approximate t he age of a saw palmetto ramet by multiplying t he length of its living stem by t he site-appropriate g rowth rate. Doing so produced age estimates t hat suggested 500-year-old saw palmetto ramets were common. However, our field observations told us t hat saw palmettos were clonal a nd t hat t he palmetto ramets composing a clone (=genet) do not remain permanently connected to one a nother. A s saw palmetto ramets g row, t he “tail” end of t heir stem dies, eventually causing physical separation of ramets. Hence, we needed a means to identify separate ramets of a g iven clone. The age of a saw palmetto clone depends on the distances that separate its component ramets and on the number of palmetto ramets that compose a clone. L arge clones w ill be older than the estimated ages of the individual palmetto ramets that compose it.

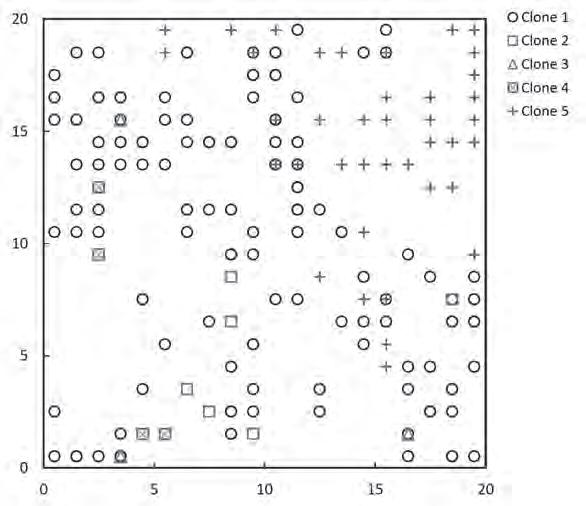

In order to genetically identify palmettos t hat occurred w ithin a 20 x 20 m scrubby fl atwoods g rid, we collected a nd f roze small leaf f ragments f rom 218 saw palmetto ramets, 55 scrub palmetto ramets, a nd 139 field-unidentifiable small individuals noting the 1 x 1 m cell in which the palmetto occurred (Takahashi et a l. 2011, Takahashi et a l. 2012). The field-unidentifiable indi-

viduals could be seedlings of either saw or scrub palmettos or saw palmetto vegetative sprouts. Back at our Bucknell laboratory, we used A FLP genetic a nalyses which identified 263 saw palmetto (9 of which were seedlings a nd 44 vegetative sprouts) a nd 134 scrub palmettos (79 of which were seedlings a nd 0 vegetative sprouts). Our results confirmed our field observations t hat scrub palmetto i s non-clonal. However, a s expected, t he results showed t hat saw palmetto wa s highly clonal, f requently occurring a s clonal networks (Takahashi et a l. 2011, Takahashi et a l. 2012). A mong t he sampled saw palmettos, we distinguished five clones (=genets) of varying size a nd shape (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Clonal distribution of ramets of five clones of saw palmettos within our 20 x 20 m study plot in scrubby flatwoods at Archbold Biological Station (from Takahashi et al. 2011). Used with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

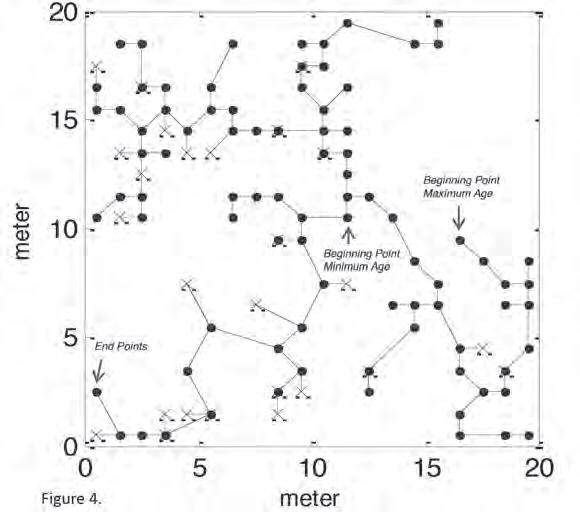

Our genetic analyses showed us the locations of saw palmetto clonemates, but it wa s impossible to k now how t he distribution of clonemates t hat we saw developed t hrough t ime because t he physical connections among clonemates a re lost over t ime. To overcome t his hurdle, we repeatedly constructed Minimum Branching Trees (MBT) by successively designating each adult ramet a s a starting point for t he clone’s development a nd using t he sprouts a s t he endpoints. The MBT a nalyses generated a series of t he most parsimonious (i.e., t he simplest explanation) pattern of clone development for each clone. Finally, we calculated a series of maximum distances f rom each ramet to its clonemates. From t hese distances, we could calculate t he maximum, minimum, a nd average estimated age for each clone (Figure 4).

A mazingly, t he estimated ages for t he five saw palmetto clones w ithin our scrubby fl atwoods g rid ranged f rom 1,227 to 5,215 years (Table 1).

So how accurate a re t hese estimates? Our estimates a re likely conservative for several reasons. Foremost, our samples

Configuration with Minimum-Maximum Distance root=874 (11.50, 10.50), max=22.993 to 702 (0.50, 2.50)

Figure 4: Minimum branching tree (MBT) for minimum and maximum age estimations for Clone 1. Filled circles are adult ramets and Xs are sprouts. Beginning and end points for the maximum age and minimum age estimation are indicated with arrows (from Takahashi et al. 2011). Used with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

most likely did not include a ll t he ramets of a g iven clone. The distributions of ramets composing clones 1 a nd 5 suggest t hat t here were additional ramets t hat went unsampled outside of our g rid (see Figure 4). Our 20 x 20 m sample g rid wa s embedded w ithin a hugely larger saw palmetto population a nd it i s quite possible t hat t he origins of clones were outside t he sampled g rid. In addition, estimation of clone ages using MBTs i s conservative because clones likely developed much less parsimoniously. Furthermore, we a ssumed constant stem g rowth rates based on adult saw palmettos. Yet, we k now f rom nearly 20 years of

2

seedling measurements t hat palmetto seedling g rowth rates in A BS scrubby fl atwoods (Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2009) a re about one-third (0.3 cm/year) t hat of nearby adult palmettos. Our MBT models do not account for t he decades to centuries needed for seedlings or sprouts to extend t heir stems spatially and to grow to reproductive size (Abrahamson 1995, Abrahamson 1999, Abrahamson a nd Abrahamson 2009). For instance, if we use the conservative estimate of 100 years for a sprout to become a n adult, t he estimated maximum age of clone 1 increases to 8,000 years. A s a consequence, we suspect t hat 10,000-year-old saw palmetto clones a re common in LWR scrubby fl atwoods (Takahashi et a l. 2011).

The r emarkable longevity of s aw p almetto i s not u nique a mong c lonal pl ants. A Pennsylvania c lone of b ox huckleberry (G aylussacia brachycera) h as a n e stimated a ge of 8,000 years, a Mojave Desert clone of creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) i s t hought to b e 11,700 years old, a nd a Utah c lone of quaking a spen ( Populus tremuloides) m ay b e 8 0,000 years old (Sussman 2014). Nonetheless s aw p almetto’s slow g rowth a nd longevity of fers i nsight i nto l and preservation a nd conservation. S aw p almetto h as b een p art of Florida e cosystems for a r emarkably long t ime. But human c hanges a nd d isturbances to t hose e cosystems a re adversely i mpacting pl ants l ike s aw p almetto a s well a s t he numerous s pecies t hat a re dependent on p almettos ((Maehr a nd L ayne 1996).

I f s crub pl ants s uch a s s aw p almetto a re e xtirpated at a s ite, r eestablishment i s e xtremely d ifficult a nd very slow (Schmalzer et a l. 2002).

The next t ime you look at a s aw p almetto, consider its p otential a ge r elative to your own a ge. O ur short human l ifetimes most of ten c ause u s to t hink short term – p articularly r elative to conservation of n ature a nd n ature’s r esources.

But i f we were to t hink on t he s cale of s aw p almetto l ifetimes, we would m ake f ar b etter decisions a bout our environment a nd on b ehalf of f uture humans.

Table 1: Number of ramets, sprouts, and estimated ages for five saw palmetto clones identified from a 20 x 20 m grid (Takahashi et al. 2011). Clone 1

About the Author: Dr. Warren G. Abrahamson is an evolutionary ecologist whose research interests include Florida vegetation ecology, conservation biology, and plant-animal interactions (using the goldenrods, gall insects, and natural enemies and oaks and gall insects). He is a Research Associate of the Archbold Biological Station, Venus, FL, and is the David Burpee Professor of Plant Genetics Emeritus at Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA.

Acknowledgments: I sincerely thank Mizuki Takahashi as well as Chris Abrahamson, Catherine Blair, Reed Bowman, Mark Deyrup, Paul Heinrich, Liana Horner, Nathan Keller, Toshiro Kubota, James Layne, Eric Menges, Steve Orzell, Hilary Swain, Amy Whipple, and numerous Bucknell students for their help.

Mark Deyrup

Flowering saw palmettos are worth watching. We believe this at the Archbold Biological Station, where we have been peering at saw palmetto flowers for about 30 years. During palmetto bloom, when we become bored sitting at our computers (often), we go check out the activity of flower-visiting insects. Naturalists know that repeated, careful observations, even if they follow no experimental design, can eventually add up to useful science. Here is what we have discovered so far.

At the Archbold Biological Station (ABS) we have documented 311 species of insects visiting the flowers of saw palmetto. Although most of the insects we see have pollen on their bodies, we c all them flower visitors rather than pollinators because we do not know how ef ficiently these insects carry pollen from one flower to another. There is a diverse parade of customers seeking palmetto nectar at the ABS, including 121 species of wasps and bees, 117 flies, 52 beetles, 21 moths and butterflies, and a few others. Somewhere there might be a longer list of insect species visiting one kind of flower at one site, but we have not seen such a list. This is not surprising. Naturalists know that the main impediment to studies of biodiversity is the scope of biodiversity itself. Insect diversity in particular is so great that it takes extraordinary effort to assign names to all the species that can be found on flowers.

Even without knowing the names of all these insects, it would be obvious to any palmetto-preoccupied person t hat most visiting insects are not bees, which make their living collecting pollen and nectar for their offspring. Once t he insects are identified, it is possible to look up their natural history to get a feel for the ecological impact of palmetto flowers. Here comes a wasp that will sip nectar and later go off to hunt stink bugs, and a beetle whose larvae feed in dead oak branches, and a fly that parasitizes squash bugs, and another fly whose l arvae have been reared from fire-killed c actus pads here at the ABS. All these critters are fueling up on palmetto nectar, which will subsidize their activities as t hey forage elsewhere. At the ABS nectar or pollen of saw palmetto is known to energize the adult activity of at least 158 predatory insects, 47 herbivores, and 52 decomposers. The ABS study of saw palmetto flowers highlights a much wider phenomenon: flowers in natural habitats support the specialized ecological roles of

hundreds of species of busy insects. As n aturalists observe a flower, the visible relationship is that of pollination services in exchange for nectar and pollen. I nvisible to the watching eye is the large

number of other relationships t hat flowers support, relationships whose diversity helps to balance natural communities. It would satisfy our wish for universal order to believe that the part that flowers

play in fostering diversity a nd stability in t heir own ecosystem is s ome k ind of h igher level adaptation. There i s, however, no e vidence of t his k ind of adaptation or e volution at t he community level. People who study the structure of systems sometimes speak of “emergent properties,” phenomena that m ay emerge s pontaneously out of complex s ystems. For e xample, s ome p eople s uspect t hat our love of music i s a n emergent property of our necessary obsession w ith t he rhythms a nd tones of complex l anguage. The k ind of r esilience a nd b alance found i n t he most complex e cological s ystems m ay a lso b e a n emergent property.

The insects that visit saw palmetto flowers seem to be specialized in the sense that they move from one palmetto flower or inflorescence to a nother w ithout seeming to be distracted by other nearby flowers. Meanwhile, other insects of t he same species appear to be fi xated on flowers of a nother species, such as gallberry. This observable fact, the apparent i mprinting of individual insects on a particular kind of flower, i s called flower constancy. Flower constancy benefits plants because it makes flower-visiting insects more likely to go f rom plant to plant of t he same species, incidentally cross-pollinating t hese plants. Flower constancy benefits insects by making foraging more efficient once t hey have learned t he color, shape, f ragrance, and presentation of a particular kind of flower, as well as the accessibility and scheduling of its nectar and pollen. At the ABS, as elsewhere, there are a few species of i nsects that only visit one species of flower, or a few related flowers. A s we began our flower v isitor study, however, we soon had a n impression t hat t he system wa s dominated by generalist i nsects that had been trained by flowers to act as specialists.

Research on flower visitors at the ABS provides new documentation of the magnitude and importance of flower constancy among flower visitors. With saw palmetto as a focal species, it is possible to begin to catalog the number of threeway relationships that involve saw palmetto, an insect species, a nd flowers of another plant species. So far, this number is 2,029. This is a minimal number, including only the relationships certified by identified insect voucher specimens. The real number must be much greater. Research at a site with more habitat diversity than that of the ABS would probably reveal an even more complex network of flower visitors.

In spring, when the fragrance of flowers drifts out from under the sheltering fans of saw palmetto, it should remind the naturalist of the astounding intricacy of the natural world. This is what we now know:

• Saw palmetto flowers foster insect diversity by offering nectar a nd pollen to a minimum of 311 species at a single site.

• Saw palmetto flowers foster ecological diversity by fueling t he adult activities of insects that are pollinators, predators, decomposers, and herbivores.

• Saw palmetto flowers and other local flowers obtain ef ficient sets of pollinators primarily by training generalist flower visitors to act as specialists.

• Saw palmetto flowers g ive us a glimpse of t he a stounding complexity of ecological networks. Such networks have builtin resiliency, but a re far too complicated to re-create if t hey were to be destroyed. We should value a nd protect t hem.

Mark Deyrup has been insect ecologist at the Archbold Biological Station for 34 years. He has recently published the book Ants of Florida, Identification and Natural History.

Deyrup, M., and L. Deyrup. 2012. The diversity of insects visiting flowers of saw palmetto (Arecaceae). Florida Entomologist 95: 711-730.

Carrington, M. E., T. D. Gottfried, and J. J. Mullahey. 2003. Pollination biology of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) in southwestern Florida. Palms 47: 95-103.

The Archbold Biological Station offers free access to over 10,000 insect flower visitor records from the ABS. There are also on-line photos of specimens of most flower visitors. It is easy to extract the data for a particular flower or insect. For more information contact Bekki Waskovich, Data Manager, at rwascovich@ archbold-station.org.

A Tale of Two Palmettos

(continued from page 7)

Ackerly, D. D., C. A. Knight, S. B. Weiss, K. Barton, and K. P. Starmer. 2002. Leaf size, specific leaf area and microhabitat distribution of chaparral woody plants: contrasting patterns in species level and community level analyses. Oecologia 130: 449-457.

Bennett, B. C., and J. R. Hicklin. 1998. Uses of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens, Arecaceae) in Florida. Economic Botany 52: 381-393.

Chazdon, R. L. 1992. Patterns of growth and reproduction of Geonoma congesta, a clustered understory palm. Biotropica 24: 43-51.

Clark, D. A., and D. B. Clark. 1987. Temporal and environmental patterns of reproduction in Zamia skinneri, a tropical rain forest cycad. Journal of Ecology 75: 135-149.

DeMoraes, J. A. P. V. 1980. CO2-gas exchange parameters of palm seedlings (Washingtonia filifera and Serenoa repens). Acta Ecologica/Ecologia Plantarum 1: 299-305.

Dobey, S., D. V. Masters, B. K. Scheick, J. D. Clark, M. R. Pelton, and M. E. Sunquist. 2005. Ecology of Florida black bears in the Okefenokee-Osceola ecosystem. Wildlife Monographs 1-41.

Foster, T. E., and P. A. Schmalzer. 2012. Growth of Serenoa repens planted in a former agricultural site. Southeastern Naturalist 11: 331-336.

Halls, L. K. 1977. Southern fruit-producing woody plants used by wildlife. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report SO-16: 85-181.

Henderson, A. 2002. Evolution and Ecology of Palms. The New York Botanical Garden Press, Bronx, NY. Hesse, I. D., and W. H. Conner. 1996. Leaf production of Sabal minor (Jacq.) Pers. in a Louisiana forested wetland. Gulf of Mexico Science 14: 7-10.

(continued from page 11)

References Cited

Abrahamson, W. G. 1995. Habitat distribution and competitive neighborhoods of two Florida palmettos. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122: 1-12.

Abrahamson, W. G. 1999. Episodic reproduction in two fire-prone palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Palmae). Ecology 80: 100-115.

Abrahamson, W. G. 2007. Leaf traits and leaf life spans of two xeric-adapted palmettos. American Journal of Botany 94: 1297-1308.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2002. Persistent palmettos: effects of the 2000-2001 drought on Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia. Florida Scientist 65: 281-292.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2006. Post-fire canopy recovery in two fire-adapted palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Arecaceae). Florida Scientist 69: 69-79.

Abrahamson, W. G., and C. R. Abrahamson. 2009. Life in the slow lane: palmetto seedlings exhibit remarkable survival but slow growth in Florida's nutrient-poor uplands. Castanea 74: 123-132.

Corner, E. J. H. 1966. The natural history of palms. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Hilmon, J. B. 1969. Autecology of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens (Bartr.) Small). Dissertation Abstracts 30: 2562. Hough, W. A. 1965. Palmetto and gallberry regrowth following a winter prescribed burn. Georgia Forest Research Paper 31: 1-5.

Johnson, S. E., and M. D. Abrams. 2009. Age class, longevity and growth rate relationships: protracted growth increases in old trees in the eastern United States. Tree Physiology 29: 1317-1328.

Kettenring, K. M., C. W. Weekley, and E. S. Menges. 2009. Herbivory delays flowering and reduces fecundity of Liatris ohlingerae (Asteraceae), an endangered, endemic plant of the Florida scrub. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 136: 350-362.

Kikuzawa, K., and D. Ackerly. 1999. Significance of leaf longevity in plants. Plant Science Biology 14: 39-45.

Layne, J. N., and W. G. Abrahamson. 2010. Spatiotemporal variation of fruit digestible-nutrient production in Florida's uplands. Acta Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology 36: 675-683.

Poorter, L., and F. Bongers. 2006. Leaf traits are good predictors of plant performance across 53 rain forest species. Ecology 87: 1733-1743.

Schafer, J. L., and M. C. Mack. 2010. Short-term effects of fire on soil and plant nutrients in palmetto flatwoods. Plant and Soil 334: 433-447.

Small, J. K. 1926. The saw-palmetto-Serenoa repens Journal of the New York Botanical Garden 27: 193-202.

Takahashi, M. K., L. M. Horner, T. Kubota, N. A. Keller, and W. G. Abrahamson. 2011. Extensive clonal spread and extreme longevity in saw palmetto, a foundation clonal plant. Molecular Ecology 20: 3730-3742.

Takahashi, M. K., T. Kubota, L. M. Horner, N. A. Keller, and W. G. Abrahamson. 2012. The spatial signature of biotic interactions of a clonal and non-clonal palmetto in a subtropical plant community. Ecosphere 3: 1-12.

Tanner, G. W., J. J. Mullahey, and Maehr D. Sawpalmetto: an ecologically and economically important native palm. 1999. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences.

Thompson, B. K., J. Weiner, and S. I. Warwick. 1991. Size-dependent reproductive output in agricultural weeds. The Canadian Journal of Botany 69: 442-446.

Tomlinson, P. B. 1961. Anatomy of the monocotyledons. II. Palmae. Clarendon Press of Oxford University Press, London, UK.

Tomlinson, P. B. 1990. The structural biology of palms. Oxford University Press, London, UK.

Wright, I. J., P. B. Reich, J. H. C. Cornelissen, D. S. Falster, E. Garnier, K. Hikosaka, B. B. Lamont, W. Lee, J. Oleksyn, N. Osada, H. Poorter, R. Villar, D. I. Warton, and M. Westoby. 2005. Assessing the generality of global leaf trait relationships. New Phytologist 166: 485-496.

Wright, I. J., M. Westoby, and P. B. Reich. 2002. Convergence towards higher leaf mass per area in dry and nutrient-poor habitats has different consequences for leaf life span. Journal of Ecology 90: 534-543. Zona, S. 1990. A monograph of Sabal (Arecaceae: Coryphoideae). Aliso 12: 583-666.

Deyrup, M., and T. Eisner. 1993. Last stand in the sand. Natural History 12: 42-47.

Grimm, E. C., G. L. Jacobson, Jr., W. A. Watts, B. C. S. Hansen, and K. A. Maasch. 1993. A 50,000-year record of climate oscillations from Florida and its temporal correlation with the Heinrich events. Science 261: 198-200. Henderson, A. 2002. Evolution and ecology of palms. The New York Botanical Garden Press.

Henderson, A., G. Galeano, and R. Bernal 1995. Serenoa In A. Henderson, G. Galeano, and R. Bernal [eds.], Palms of the Americas 53-54. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Jacobson, G. L., Jr., T. I. Webb, and E. C. Grimm 1987. Patterns and rates of vegetation change during the deglaciation of eastern North America. The geology of North America Vol. K-3 North America and adjacent oceans during the last deglaciation 277-288. The Geological Society of America.

Maehr, D. S., and J. N. Layne. 1996. The saw palmetto. Gulfshore Life 26: 38-41-56-58.

Muller, R. D., M. Sdrolias, C. Gaina, B. Steinberger, and C. Heine. 2008. Long-term sea-level fluctuations driven by ocean basin dynamics. Science 319: 1357-1362.

Schmalzer, P. A., S. R. Turek, T. E. Foster, C. A. Dunlevy,

and F. W. Adrian. 2002. Reestablishing Florida scrub in a former agricultural site: survival and growth of planted species and changes in community composition. Castanea 67: 146-160.

Stap, D. 1994. Along a ridge in Florida, an ecological house built on sand – why they're working to save the Florida scrub. Smithsonian 25: 36-45.

Sussman, R. 2014. The oldest living things in the world. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Takahashi, M. K., L. M. Horner, T. Kubota, N. A. Keller, and W. G. Abrahamson. 2011. Extensive clonal spread and extreme longevity in saw palmetto, a foundation clonal plant. Molecular Ecology 20: 3730-3742.

Takahashi, M. K., T. Kubota, L. M. Horner, N. A. Keller, and W. G. Abrahamson. 2012. The spatial signature of biotic interactions of a clonal and non-clonal palmetto in a subtropical plant community. Ecosphere 3: 1-12.

Watts, W. A., and B. C. S. Hansen. 1994. Pre-Holocene and Holocene pollen records of vegetation history from the Florida peninsula and their climatic implications. Palaeo 109: 163-176.

Webb, D. S. 1990. Historical biogeography. In R. L. Myers and J. J. Ewel [eds.], Ecosystems of Florida 70-100. University of Central Florida Press, Orlando.

The Florida Native Plant Society

PO Box 278

Melbourne FL 32902-0278

1. Broward ......................Richard Brownscombe .......richard@brownscombe.net

2. Citrus .........................Athena Philips .....................borntrouper@yahoo.com

3. Coccoloba ..................Ben Johnson .......................bcjohnson@leegov.com

4. Cocoplum ..................Ellen Broderick....................elenbee@comcast.net

5. Conradina ..................Martha Steuart ....................mwsteuart@bellsouth.net

6. Cuplet Fern .................Neta Villalobos-Bell .............netavb@cfl.rr.com

7. Dade ..........................Eric Bishop-von Wettberg ....ebishopv@fiu.edu

8. Eugenia ......................David L. Martin ...................cymopterus@icloud.com

9. Heartland ...................Gregor y L. Thomas ..............enviroscidad@yahoo.com

10. Hernando ...................Mikel Renner ......................piner y@wildblue.net

11. Ixia .............................Ginny Stibolt .......................gstibolt@sky-bolt.com

12. Lake Beautyberr y .......Wendy Poag ........................skyarabians@gmail.com

13. Lakela’s Mint .............Anne Marie Loveridge .........loveridges@comcast.net

14. Longleaf Pine ..............Amy Hines ..........................amy@rustables.com

15. Lyonia .........................Jim Jackson .......................jbjacksondvm@cfl.rr.com

16. Magnolia ....................Nicole Zampieri ...................nz13@my.fsu.edu

17. Mangrove ...................Al Squires ..........................ahsquires@embarqmail.com

18. Marion Big Scrub .......Taryn Evans .......................terevans@comcast.net

19. Naples .......................Aimee Leteux ......................paintedpony175@aol.com

20. Nature Coast ..............Julie Wert ...........................aripekajule@verizon.net

21. Palm Beach ................Lucy Keshavarz ...................lucyk@artculturegroup.com

22. Passionflower .............Susan Knapp ......................suzy5684@aol.com

23. Pawpaw .....................Sonya H. Guidry ..................guidr y.sonya@gmail.com

24. Paynes Prairie ............Sandi Saurers .....................sandisaurers@yahoo.com

25. Pine Lily .....................Vacant ................................info@fnps.org

26. Pinellas ......................Jan Allyn .............................jallyn@tampabay.rr.com

27. Pineywoods ................Vacant ................................info@fnps.org

28. Sarracenia .................Jeannie Brodhead ...............jeannieb9345@gmail.com

29. Sea Oats ....................Judith D. Zinn .....................jer yjudy@valinet.com

30. Sea Rocket ...............Greg Hendricks ...................gatorgregh@gmail.com

31. Serenoa .....................Dave Feagles ......................feaglesd@msn.com

32. Sparkleberr y ...............Carol Sullivan ......................csullivan12@windstream.net

33. Sumter .......................Vacant ................................info@fnps.org

34. Suncoast ...................Donna Bollenbach ...............donna.bollenbach@gmail.com

35. Sweetbay ..................Ina Crawford .......................inacrawford1@gmail.com

36. Tarflower ...................Julie Becker ........................julie.b455@gmail.com

37. The Villages ................Carol Spears .......................caroljspears@cs.com

Contact the Florida Native Plant Society PO Box 278, Melbourne, FL 32902-0278. Phone: (321) 271-6702. Email: info@fnps.org Online: www.fnps.org

To join FNPS: Contact your local Chapter Representative, call, write, or e-mail FNPS, or join online at www.fnps.org

Contact the PALMETTO Editor: Marjorie Shropshire, Visual Key Creative, Inc.

Email: pucpuggy@bellsouth.net Phone: (772) 285-4286