The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society

Florida Scrub is Nuts (and Drupes) ● FNPS Advocacy Update ● A New Orchid in Town

Staff

Executive Director Melissa Fernandez-de Cespedes

Director of Communications and Programming ................Valerie Anderson

Director of North Florida Programs and TorreyaKeepers

Project Coordinator Lilly Anderson-Messec

Operations Manager ...........Cherice Smithers

Board of Directors

Past President .................................................Mark Kateli

President ............................................................Eugene Kelly

Vice President, Finance ............................Ann Redmond

Vice President, Administration .............Athena Phillips

Treasurer ............................................................Chris Moran

Secretary ...........................................................Bonnie Basham

Council of Chapters Representative.........................................Rebekah Kaufman

Directors at Large: ..................................................................................Adam Arendell ..................................................................................Susan Earley ..................................................................................Gage LaPierre ..................................................................................Natalia Manrique ..................................................................................David Martin

..................................................................................Paul Schmalzer

To contact board members

FNPS Administrative Services: Call (321) 271-6702 or email info@fnps.org

Committee Chairs

Conservation ...................................................John Benton

Council of Chapters .....................................Rebekah Kaufman

Education...........................................................Andrea Andersen

Policy and Legislation................................Eugene Kelly

Science................................................................Paul Schmalzer

Society Services

Administrative Services............................Cherice Smithers

Bookkeeping ....................................................Kim Zarillo

Editor, Palmetto ..............................................Marjorie Shropshire

Webmaster........................................................Paul Rebmann

MEMBERSHIP

Make a difference with FNPS

Your membership supports the preservation and restoration of wildlife habitats and biological diversity through the conservation of native plants. It also funds awards for leaders in native plant education, preservation, and research.

Memberships are available in these categories: Individual; Multi-member household; Sustaining; Lifetime; Full-time student; Library (Palmetto subscription only); Business or Non-profit recognition.

To provide funds that will enable us to protect Florida's native plant heritage, please join or renew at the highest level you can afford.

To become a member:

Contact your local chapter, call, write, or e-mail FNPS, or join online at https://www.fnps.org/

The purpose of the Florida Native Plant Society is to preserve, conserve, and restore the native plants and native plant communities of Florida.

Official definition of native plant:

For most purposes, the phrase Florida native plant refers to those species occurring within the state boundaries prior to European contact, according to the best available scientific and historical documentation. More specifically, it includes those species understood as indigenous, occurring in natural associations in habitats that existed prior to significant human impacts and alterations of the landscape

Follow FNPS online:

Blog: http://fnpsblog.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/floridanativeplantsociety

Instagram: https://instagram.com/floridanativeplantsociety/ LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/florida-na tive-plant-society-inc-/

TikTok: https://tiktok.com/@floridanativeplants

X : https://x.com/fl_native_plant

YouTube: https://tinyurl.com/yx7y897d

Features

4 Florida Scrub is Nuts (and Drupes) Article by Dr. Warren G. Abrahamson

9 Advocating for Native Plant Conservation Yields Noteworthy Successes Article by Valerie Anderson and Eugene Kelly

14 A New Orchid in Town Article by Roger L. Hammer

Palmetto

Editor: Marjorie Shropshire ● Visual Key Creative, Inc. ● palmetto@fnps.org ● (772) 285-4286

(ISSN 0276-4164) Copyright 2025, Florida Native Plant Society, all rights reserved. No part of the contents of this magazine may be reproduced by any means without written consent of the editor.

Palmetto is published four times a year by the Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS) as a benefit to members. The observations and opinions expressed in attributed columns and articles are those of the respective authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views of the Florida Native Plant Society or the editor, except where otherwise stated.

Editorial Content

We welcome articles on native plant species and related conservation topics, as well as high-quality botanical illustrations and photographs. Contact the editor for guidelines, deadlines and other information.

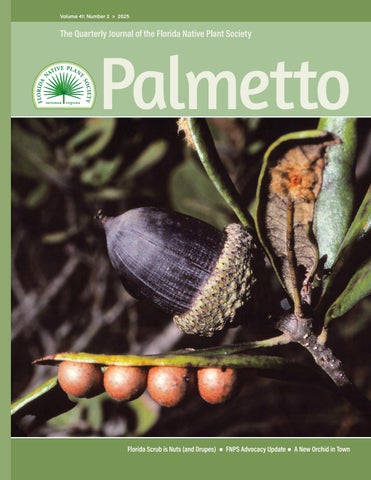

ON THE COVER:

The low tannin content acorns of sand live oak (Quercus geminata) are valued by numerous Florida scrub animals including the black bear and Florida scrub-jay. Photo by Warren Abrahamson. See story on page 4.

Article by Dr. Warren G. Abrahamson

Photos by Adam Bass, James Layne, and Warren Abrahamson

Florida Scrub is Nuts (and Drupes):

Fruit Production and Consumption in Florida’s Fire-Prone, Xeric Uplands

This is a story about how plant size, fire, and climate affect fruit and nut production (i.e., mast) in Florida’s fire-prone, xeric uplands and the importance of mast as food for wildlife. To set the stage, let’s first explore the primary mast-producing plants of Florida’s xeric uplands: oaks, hickory, and palmettos.

Primary Mast Producers

Imagine a team of scientists spending day after day counting every nut on tree after tree. Studies of fruit and nut production (mast) began at Archbold Biological Station more than fifty years ago. Starting in 1969, James Layne and associates recorded annual mast production by eight fruit-producing shrubs and trees in long-unburned southern ridge sandhill, sand pine scrub, and scrubby flatwoods. The study counted oak acorns (a nut), “drupaceous” nuts of Florida-endemic scrub hickory (Carya floridana), and drupes (a fleshy fruit with a shell that holds a seed) of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) and Floridaendemic scrub palmetto (Sabal etonia) that occurred in one or

more vegetation associations. Acorns on five oak species were tallied including on the red oaks: myrtle oak (Quercus myrtifolia), Florida-endemic scrub oak (Q. inopina), and turkey oak (Q. laevis); the white oak, Chapman’s oak (Q. chapmanii ), and the southern live oak, sand live oak (Q. geminata).

Four of the five oaks, scrub hickory, and saw palmetto are clonal species. Their clones are composed of genetically identical, physiological individuals (termed “ramets”) produced by vegetative propagation that may or may not be physically connected. The entire clone or genetic individual is referred as a “genet,” which includes all the ramets that originated from a single seed. Turkey oak and scrub palmetto are non-clonal.

Figure 1. The white oak, Chapman's oak is a major producer of mast in Florida scrub. Chapman's oak and the red oak, myrtle oak, typically produce the most acorns at Archbold. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

Figure 2. The low tannin content acorns of sand live oak are valued by numerous Florida scrub animals including the black bear and Florida scrub-jay. The four ball-shaped leaf galls were stimulated by the asexual generation (i.e., all female) of the cynipid wasp Belonocnema fossoria while the fuzzy orange gall on the leaf underside was stimulated by the asexual generation of the cynipid wasp Druon quercuslanigerum. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

Mast Production by Plant Size, Species, and Vegetation Association

Size often predicts whether plants flower and bear fruit. At Archbold, not only do large ramets flower and fruit more often than small ones, but large ramets also produce more mast. Yet, mast production by the largest oaks at Archbold often declines, suggesting that large ramets become senescent. Nonetheless, mast production in Archbold’s long-unburned habitats stays at reasonable levels because new ramets replace senesced ramets. Consequently, intermediate-size oaks produce the most mast/unit area.

Mast production also varies by species and by vegetative association. Among oaks, Chapman’s and myrtle oaks produce the most mast; sand live oak is intermediate; and scrub and turkey oaks are consistently low mast producers (Figures 1-2). Light availability differs by vegetative association and is likely the reason that nut production by oaks and scrub hickory is lowest in nearly closed canopy sand pine scrub. Not only do nuts occur less often on plants in sand pine scrub when a plant fruits, it

produces fewer nuts than similar-size plants of the same species in more open-canopied sandhill or scrubby flatwoods. Similarly, palmettos that grow under canopy gaps in nearly closed canopy sand pine scrub fruit more often than those under complete canopy. Yet, across vegetation associations a given species’ mast production is synchronized despite marked year-to-year variations (Abrahamson 1999; Abrahamson and Layne 2002a, 2002b, 2003; Layne and Abrahamson 2004).

Recovery of Mast Production After Fire

For sprouting species adapted to fire-prone ecosystems, the length of time from fire to seed production is important to plant persistence, recruitment, and evolutionary success. A postfire strategy of rapid sprouting and fruiting provides opportunities for both local recovery as well as seed dispersal and potential colonization of new sites (Figure 3). Hence, we might expect Florida scrub’s mast-producing species to rapidly sprout and quickly regain mast production before another fire kills above-ground tissues.

A s expected, Archbold scientists found that mast producers rapidly sprout and quickly regain mast production following fire. For example, new sprouts of palmettos, scrub hickory, Chapman’s oak, and sand live oak produce drupes or nuts in the first full growing season following fire (Figure 4). Red oak species take a bit longer; myrtle oak typically requires three years and turkey

Figure 3. The head fire (a fire pushed by the wind) of an Archbold prescribed burn blots out the sun as it races through oaks, palmettos, south Florida slash pines, and more. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

Figure 4. Sand live oak and other Florida scrub masting species rapidly sprout following fire. Southern live oak species, white oak species, palmettos, and scrub hickory can produce fruits in the first full growing season following a fire. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

oak, four years to produce acorns (Figure 5). The differences among oaks are due to the dissimilar reproductive biology of white/southern live oaks and red oaks. The flowers of white and southern live oaks develop into mature acorns in the autumn of the same year, while red oaks produce flowers during spring of one year, but acorns mature in the following year. While rapid postfire mast recovery is beneficial to plants of fire-prone environments, it also benefits fruit-consuming animals as we will learn below (Abrahamson, 1999; Abrahamson and Layne 2002a; Layne and Abrahamson 2004).

Fire History and Climate Affect Mast Seeding

The terms “mast seeding” or “masting” describe highly variable year-to-year levels of fruit and seed production that is synchronized across individuals of a population. Although a given population of a species makes few fruits in some years and abundant crops in other years, different species within a plant community typically vary when low and high mast-seeding years occur. These differences are due in large part to the varied reproductive biology of species as well as the time necessary for individuals to accumulate sufficient resources to fruit. For example, plants of nutrient-limited or light-limited habitats typically need more time to gain sufficient resources to reproduce.

A rchbold studies also found that plant reproduction is markedly affected by fire and climate. By killing above-ground plant tissues, fire tends to synchronize the timing of reproduction among new sprouts. Oak ramets with the same fire history

are more synchronous in acorn production than are ramets of dissimilar fire history. In addition, climate can affect the amount of mast produced. For example, precipitation or drought during the spring flowering season has positive or negative impacts, respectively, on acorn production (Pesendorfer et al. 2021).

Thus, year-to-year variation in fruit production and synchrony among individuals develops from the interaction of a species’ innate reproductive biology with fire and climate. Cyclic patterns of mast seeding result that typically range from 2 to 2.4 yr among white and southern live oak species, 3.6 to 5.5 yr among red oak species, 2 to 3 yr for scrub hickory, and generally 2 yr for palmettos (Abrahamson and Layne 2003, Layne and Abrahamson 2010).

Scientists have offered many hypotheses to explain why mast seeding occurs. The hypotheses include the predator-satiation hypothesis, which argues that the unpredictable pulses of mast availability make it difficult for seed predators to track pulses. A large mast crop can overwhelm the consumption ability of seed predators, allowing some seeds to escape predation. Similarly, the pollination-efficiency and animal-dispersal hypotheses suggest more successful pollination and fertilization (especially for wind-pollinated plants) or seed dispersal by animals occur when flowering or fruiting of individuals is synchronous. Yet, Florida scrub mast-seeding plants are strongly influenced by fire events as well as by water availability. The resource-matching hypothesis suggests that variation in mast production is related to the availability of limiting resources such as water or light. For scrub’s mast producers, we see strong interactions of their inherent reproductive cycles with fire events, as well as secondary effects by spring precipitation and light limitation.

Crucial for fruit consumers, there has been no year of complete mast failure at Archbold despite high year-to-year variation

Figure 6. Scrub hickory nuts are not only the largest nut among Archbold’s mast-seeding species, but they also have the highest nutritional quality due to elevated levels of energy, protein, and fats. Photo taken at Archbold by James Layne.

Figure 5. The deciduous leaves of a turkey oak sprout take on a beautiful reddish orange color during late autumn. Red oak species quickly sprout after fire but typically require three years (myrtle and scrub oak) to four years (turkey oak) to produce acorns. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

in mast levels by individual species. The differing reproductive biology of red oaks versus white/southern live oaks coupled with periodic, patchy fires and variable precipitation means that at least one or more species produce reasonable levels of mast each year. Biodiversity of mast-seeding species ensures that fruit consumers have at least a modest amount of mast every year.

Nutritional Quality of Mast

The nutritional value of forbs and grasses declines by autumn, which makes autumn-available mast especially important to fruit-eating animals, particularly to migratory birds and vertebrates that cache mast for winter food. Red oak acorns like those of myrtle, scrub, and turkey oaks have germination dormancy so they are an excellent choice to cache. Southern live oaks and white oaks have limited dormancy so they can germinate soon after caching. Acorns of southern live oaks typically have a 30–60-day germination dormancy while white oaks have little to no dormancy. For animals that cache mast, southern live and white acorns are better eaten fresh while acorns of red oak species are good candidates to cache for consumption when little mast or other foods are available.

The nutritional quality of Florida scrub’s primary mast producers varies widely across species. Mast’s nutritional quality can be assessed by “total digestible nutrients,” which is a measure of the digestible portions of mast that supply energy, carbohydrates, protein, and fat to animals. Scrub hickory not only has the largest nut among Archbold’s mast-seeding species, but it also has the highest nutritional quality due to elevated levels of energy, protein, and fat (Figure 6). The next highest total digestible nutrients levels are the acorns of red oaks like myrtle oak and scrub oak. Members of a group of species have similar, intermediate levels of mast nutritional quality including turkey oak (the largest acorn at Archbold), Chapman’s oak, sand live oak, dwarf live oak, and saw palmetto. Scrub palmetto’s drupes (which are smaller than saw palmetto’s drupes) have the lowest nutritional quality of those examined (Abrahamson and Abrahamson 1989).

Acorns account for a major part of mast consumed at Archbold because of oak abundance. Consequently, oaks provide three quarters of the total digestible nutrients in sandhill and about 70% in both sand pine scrub and scrubby flatwoods. Among oaks, myrtle oak is the major contributor and turkey oak the poorest. In comparison, scrub hickory mast contributions are low because of its low fruit numbers, yet surprisingly its greatest total digestible nutrients contribution occurs in nearly closed canopy sand pine scrub, the association with the least availability of mast. Palmettos contribute nearly a third of mast in open-canopy scrubby flatwoods but only 10-15% in long unburned sandhill and sand pine scrub even though these associations have the largest palmettos (Layne and Abrahamson 2010).

Given the nutrient-poor, sandy soils of Florida scrub, we might think that scrub’s mast is lower in nutritional quality than

that produced on richer soils. Surprisingly, scrub’s acorns are notably higher in total digestible nutrients, starches, and sugars than acorns from richer soils in other geographic locations. Myrtle and scrub oak acorns are remarkably high in crude fat and exceptionally low in crude fiber compared to acorns elsewhere. We might also wonder how periodic fires influence fruit quality; perhaps fruits in recently burned areas have higher quality since fires release mineral elements. However, at Archbold, there is no general pattern among species of higher fruit nutritional quality in recently burned areas compared to long unburned areas (Abrahamson and Abrahamson 1989).

Who Eats Florida Scrub’s Mast?

Several factors influence the importance of a fruit or seed in a consumer’s diet including its nutrition and energy content, availability (both seasonally and spatially), palatability, and accessibility. For example, saw palmetto drupes and oak acorns are both considered vital natural food items throughout the Florida black bear’s range (Figure 7). However, their availability influences their consumption by bears. Acorns occur in about half of the droppings of black bears in the Highland-Glades subpopulation during autumn and winter months. However, saw palmetto seeds are present in about half of the droppings only during autumn (Murphy et al. 2017).

We might wonder whether years with high mast levels affect populations of fruit consumers. Indeed, they do. Higher survival of both juvenile and breeder Florida scrub-jays is associated with greater abundance of acorns (acorns are scrub-jay’s most important source of winter food). Furthermore, acorn abundance has a positive effect on jay population growth rates (Summers et al. 2024). Scrub-jays consume acorns year-round, eating them directly off trees during late summer through December and consuming their cached acorns the rest of the year (Figure 8). Amazingly, an individual scrub-jay can cache between 6,500 and 8,000 acorns during autumn and later find about one-third (DeGange et al. 1989).

Palatability and nutritional quality of mast affect fruit consumer preference. Tannins, which make acorns bitter and potentially less palatable, typically occur at higher levels in acorns of red oak species compared to white oak and southern

Figure 7. The drupes of saw palmettos are a vital natural food throughout the Florida black bear’s range. At Archbold, saw and scrub palmettos contribute nearly a third of the mast in open-canopy scrubby flatwoods. Both ripe (black) and ripening (orange) drupes are seen in this photo. Photo taken at Archbold by Warren Abrahamson.

Figure 8. A Florida scrub-jay holds an acorn in its beak. A single scrub-jay can cache thousands of acorns each year. Because scrub-jays find only about one-third of their cached acorns, they are an important disperser of oaks. Years with high acorn abundance have a positive effect on scrub-jay population growth rates. Photograph taken at Allen David Broussard Catfish Creek Preserve by Adam Bass.

live oak acorns. Yet for Archbold’s rodents, acorn nutritional content trumps tannin content. Rodents prefer acorns in the order: myrtle oak, scrub oak, sand live oak, turkey oak, and Chapman’s oak (Layne and Abrahamson 2010).

Twenty-one known or presumed vertebrate fruit consumers occur at Archbold, including 15 mammals, five birds, and one reptile. Of the mast available, acorns are the most important fruit resource due to their abundance. Fifteen of the 21 consumers eat acorns including nine mammals: gray and southern flying squirrels, the Florida mouse, cotton mouse, oldfield mouse, and golden mouse, white-tailed deer, black bear, and feral hog, five birds: Florida scrub-jay, blue jay, red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers, and wild turkey, plus the reptile, gopher tortoise (Layne and Abrahamson 2010).

Scrub hickory nuts are consumed by 12 vertebrates including eight mammals: gray and southern flying squirrels (the primary consumers), as well as the Florida mouse, cotton mouse, oldfield mouse, and golden mouse, black bears, and feral hogs, and four birds: Florida scrub-jays, blue jays, red-bellied and red-headed woodpeckers (Layne and Abrahamson 2004, 2006).

The fleshy drupes of palmettos make them accessible to vertebrates that do not consume nuts. Sixteen vertebrates are recorded or presumed consumers including 15 mammals: opossum, nine-banded armadillo, raccoon, black bear, whitetailed deer, feral hog, red and gray foxes, gray and southern flying squirrels, Florida mouse, cotton mouse, oldfield mouse, golden mouse, and cotton rat, plus the reptile, gopher tortoise. Studies found that saw palmetto drupes are preferred over those of scrub palmetto perhaps due to its higher nutritional value (Layne and Abrahamson 2010).

Climate Change Impacts on Mast

Climate models for the southeastern United States suggest that temperature increases in coming decades will produce more precipitation variability that is punctuated by droughts that will enhance fire frequency and area burned (Bedel et al. 2013). The Archbold studies outlined above emphasize the substantial influence of fire and precipitation events on the reproductive biology of Florida scrub’s mast-seeding species. Increased fire frequency coupled with decreased spring precipitation has the potential to reduce the production of mast in the Florida scrub ecosystem. A reduction of mast production will cause cascading declines as less mast availability adversely affects fruit consumers as well as the predators of fruit consumers.

References

Abrahamson, W.G. 1999. Episodic reproduction in two fire-prone palms, Serenoa repens and Sabal etonia (Palmae). Ecology 80: 100-115. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[0100:ERITFP]2.0.CO;2

Abrahamson, W.G. and C.R. Abrahamson. 1989. Nutritional quality of biotically dispersed f ruits in Florida sandridge habitats. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 116: 215-228. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2996811?origin=crossref

Abrahamson, W.G. and J.N. Layne. 2002a. Relation of ramet size to acorn production in five oak species of xeric upland habitats in south-central Florida. American Journal of Botany 89: 124-131. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.89.1.124

Abrahamson, W.G. and J.N. Layne. 2002b. Post-fire recovery of acorn production by four oak species in southern ridge sandhill association in south-central Florida. American Journal of B otany 89: 119-123. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3732/ajb.89.1.119

Abrahamson, W.G. and J.N. Layne. 2003. Long-term patterns of acorn production for five oak species in xeric Florida uplands. Ecology 84: 2476-2492. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley. com/doi/abs/10.1890/01-0707

Bedel, A.P., T.L. Mote, and S.L. Goodrick. 2013. Climate change and associated fire potential for the south-eastern United States in the 21st century. International Journal of Wildland Fire 2 2: 1034-1043. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF13018

DeGange, A.R., J.W. Fitzpatrick, J.N. Layne, and G.E. Woolfenden. 1989. Acorn harvesting by Florida scrub jays. Ecology 70: 348-356. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937539

Layne, J.N. and W.G. Abrahamson. 2004. Long-term trends in annual reproductive output of t he scrub hickory: factors influencing variation in size of nut crop. American Journal of Botany 91: 1378-1386. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.91.9.1378

Layne, J.N. and W.G. Abrahamson. 2006. Scrub hickory: a Florida endemic. The Palmetto 23: 4-13. https://www.fnps.org/assets/pdf/palmetto/Palmetto_23-2%20Layne,Abrahamson.pdf

Layne, J.N. and W.G. Abrahamson. 2010. Spatiotemporal variation of fruit digestible-nutrient production in Florida's uplands. Acta Oecologica 36: 675-683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2010.10.005

Murphy, S.M., W.A. Ulrey, J.M. Guthrie, D.S. Maehr, W.G. Abrahamson, S.C. Maehr, and J.J. C ox. 2017. Food habits of a small Florida black bear population in an endangered ecosystem. Ursus 28: 92-104. https://doi.org/10.2192/URSU-D-16-00031.1

Pesendorfer, M.B., R. Bowman, G. Gratzer, S. Pruett, A. Tringali, and J.W. Fitzpatrick. 2021. Fire history and weather interact to determine extent and synchrony of mast-seeding in r hizomatous scrub oaks of Florida. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 376: 20200381. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0381

Summers, J., E.J. Cosgrove, R. Bowman, J.W. Fitzpatrick, and N. Chen. 2024. Density dependence maintains long-term stability despite increased isolation and inbreeding in the Florida scrub-jay. Ecology Letters 27:e14483 https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14483

About the Author

Dr. Warren Abrahamson is a Research Associate of Archbold Biological Station and David Burpee Professor of Plant Genetics Emeritus at Bucknell University. An evolutionary ecologist, his research includes studies of Florida vegetation and fire, the ecology of saw and scrub palmettos, and the multi-trophic level interactions of hostplants (goldenrods and oaks), gall insects, and natural enemies.

Acknowledgments

I dedicate this article to the memory of James N. Layne whose knowledge of Florida’s ecosystems, mentorship, and collaborations made me a better scientist. I thank Chris Abrahamson, Adam Bass, Sahas Barve, Reed Bowman, Seth Bowman, Mark Deyrup, John Fitzpatrick, Linda Gette, Fred Lohrer, Marjorie Shropshire, Hilary Swain, and Chet Winegarner for field assistance, images, support, and/or discussions. Archbold Biological Station and/or Bucknell University supported the studies summarized here.

Article by Valerie Anderson and Eugene Kelly

Advocating for native plant conservation yields noteworthy successes

Protecting Florida's Conservation Lands is Essential to Plant Conservation

Great Outdoors Initiative

It has been almost a year since we first learned of the Great Outdoors Initiative and the golf courses, pickleball courts and resort hotels it envisioned for some of Florida’s most beautiful and environmentally sensitive state parks. The public responded immediately, and vehemently, to express outrage over the proposal to defile nine parks with incompatible development. Thousands of Floridians protested at the targeted parks and many legislators expressed similar outrage. Barely a week after the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) announced the initiative, Governor DeSantis announced that the plans were being shelved. It was soon revealed that the original development proposal encompassed many more parks before it was whittled down to just nine.

The work to protect our award-winning state park system from similar threats in the future didn’t end with the governor’s withdrawal of the Great Outdoors Initiative. The roller coaster ride culminated in the Florida Legislature’s unanimous passage of the State Parks Preservation Act in the closing days of the regular two-month session, and the governor’s decision to sign the act into law when it arrived on his desk. We are grateful to Senators Harrell and Bradley, and Representatives Snyder and GossettSeidman, for introducing the legislation, and to the other legislators who signed on as cosponsors as the session progressed.

FNPS played an instrumental role in halting the Great Outdoors Initiative and securing passage of the State Parks Preservation Act, a bill that protects Florida's state parks from development such as pickleball courts, hotels, and golf courses.

We are proud to acknowledge that FNPS played an instrumental role in halting the Great Outdoors Initiative and securing passage of the State Parks Preservation Act, a bill that provides protections to all state parks from development such as pickleball courts, hotels, and golf courses. FNPS members joined thousands of others in protests across the state when the initiative was first announced. Director of North Florida Programs Lilly Anderson-Messec worked in concert with the Sierra Club of Florida and the FNPS Magnolia Chapter to organize a press conference on the steps of FDEP’s Tallahassee headquarters, and spoke eloquently in defense of our state parks.

Travis Moore, FNPS Governmental Affairs Advisor, began coordinating with legislators and our conservation partners months before the legislative session opened on March 4th to ensure corrective legislation would be introduced. Next, our members responded eagerly to well-timed and strategically targeted action alerts as Travis fought back attempts to amend the legislation in ways that would have provided wiggle-room for the offending recreational uses and development to be allowed in the future.

FNPS Chapters Leap Into Action

The Pinellas and Suncoast Chapters, and FNPS Director of Communications and Programming Valerie Anderson, promoted and attended a protest rally on the Honeymoon Island

FNPS Director of North Florida Programs Lilly Anderson-Messec speaks at the press conference surrounded by supporters on the steps of the FDEP building in Tallahassee.

Photo by Ethan Liu.

State Park causeway. Honeymoon Island was one of the parks with known proposed development plans. Meanwhile, the Martin, Palm Beach County, and Broward Chapters worked with the Florida Wildlife Federation on rallies in and around Jonathan Dickinson State Park, and the Ixia Chapter worked with St. Johns Riverkeeper on organizing activism in and around Jacksonville. The Ixia chapter also led a field trip to Anastasia Island State Park to show off the park’s maritime hammock which was threatened by development plans in the Great Outdoors Initiative.

We are thankful for the support provided by FNPS members who responded quickly and passionately to our email and social media alerts. The end result of all that FNPS teamwork means our state parks are much safer now. It is also important to acknowledge the coordinated effort this victory represented. Our partners at the Florida Wildlife Federation, Florida Springs Council, Sierra Club Florida, 1000 Friends of Florida, and many others responded with similar passion. Unfortunately, the assault on our conservation lands did not begin, or end, with the Great Outdoors Initiative.

Withlacoochee State Forest Land Swap

A few months before the Great Outdoors Initiative was unveiled, the governor and cabinet quietly approved another

egregious misuse of conservation land. Cabot Citrus Farms, a luxury golf course development in Hernando County, proposed taking ownership of a publicly owned 324-acre parcel adjacent to their existing development. In exchange for the parcel, which is part of the Withlacoochee State Forest (WSF), Cabot proposed giving the state a 681-acre stand of pine plantation in Levy County. Final execution of the parcel swap was contingent on securing approval from both the Florida Forest Service (FFS)

Clockwise from upper left: The crowd on the Honeymoon Island Causeway cheers. Photo by Valerie Anderson. Supporters, including members of the Martin County Chapter of FNPS, gathered at Stuart’s Flagler Park in support of Jonathan Dickinson State Park. Photo by Marjorie Shropshire. The Ixia Chapter highlights what is worth saving about Anastasia Island State Park. Photo by Betsy Harris.

A golf ball from the adjacent course sitting next to a persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) fruit on the proposed surplus parcel of the Withlacoochee State Forest. Photo by Athena Philips, September 2024.

and FDEP’s Acquisition and Restoration Council (ARC).

F NPS conducted five site visits to the parcel, including one with journalists from the Tampa Bay Times, and completed a GIS-based assessment of the parcel’s conservation values. Based on the parcel’s significant conservation values, we submitted a letter to FFS Director Rick Dolan objecting to the proposal. After persisting in our objections for eight months, being joined by many other conservation organizations, and securing some attention from both print and broadcast media, the applicant eventually withdrew the proposal. The state had never responded formally to our objections, nor was there ever any apparent action taken to advance the proposal.

Shortly after withdrawing their proposal, Cabot Citrus Farms proposed selling a 340-acre section of their remaining undeveloped ownership to the state. The property is located within the approved Annutteliga Hammock Florida Forever Project, and the governor and cabinet gave their approval for FDEP to negotiate the purchase. So, in conclusion, FNPS helped turn a proposed loss for conservation into a potential win that would add 340 acres to Withlacoochee State Forest.

Guana River WMA Land Swap

C ontinuing the alarming trend of proposals to trade away or develop conservation lands, an off-schedule ARC meeting was announced for May 21 with only the seven-day minimum advance public notice required by law for such meetings. The agenda included consideration of a proposal to swap 600 acres of the Guana River Wildlife Management Area (GRWMA) in St. Johns County for 3,066 acres scattered among an array of non-contiguous parcels in several different counties. The GRWMA parcel, composed primarily of undisturbed upland native plant communities and featuring several miles of natural frontage on the Guana River, has benefited from decades of expert management by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. It provides habitat for a long list of imperiled plant species, including the Florida spiny-pod (Matelea floridana), hooded pitcherplant (Sarracenia minor), and shell mound prickly-pear (Opuntia stricta), in addition to housing imperiled animal species like the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), striped newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus), roseate spoonbill (Plantalea ajaja) and West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris). In contrast, the 3,066 acres proposed as compensation for the “swap” consists largely of degraded lands and a large proportion of wetland.

It is important to note that the authority to consider exchanges of state-owned conservation land, as conferred by Florida Statute 253.42, is intended to produce an increase in the conservation value of the subject property. The parcels offered in exchange for the GRWMA land are not contiguous with, or even proximate to, GRWMA and so cannot in any way enhance its conservation value. The same was true of the WSF parcel swap. Once again, the secretive announcement of a proposed land swap did not escape the public’s attention and galvanized immediate expressions of outrage and opposition.

F NPS mobilized quickly to spread the word and get people to attend the ARC meeting. Valerie Anderson generated maps

and a basic natural resources assessment, and then shared the information with our partner organizations. Lilly AndersonMessec conducted a site visit and posted an impassioned video clip encouraging viewers to contact the governor’s office and express their opposition. The video quickly accumulated thousands of views and more than a thousand Floridians signed up in advance to attend the ARC meeting and submit in-person comments. Once again, the applicant withdrew their proposal before the state took any formal action, so it was dropped from the ARC agenda.

In this case, the applicant backed away from their proposal in less than a week’s time. It is especially disturbing that the identity of the applicant remains a mystery, which only compounds the untoward appearance of this attempt to take conservation lands for profit. We can only hope that the development interests driving such proposals, and the state officials who appear to have acquiesced, now understand that the public will fight off any similar land grabs. As FNPS explained in our comments to FDEP, the willingness to even consider such proposals conveys a perception that “... our precious network of protected natural areas is nothing more than an extremely valuable real estate portfolio – and anything is negotiable.” We will refuse to allow developers to decide which lands will be retained in public ownership and which will be surrendered for development. Our “to do” list for the 2026 legislative session includes an expansion of the protections provided by the State Parks Preservation Act so they extend to other state-owned lands, including state forests and wildlife management areas, and to prevent developer-initiated land swaps.

A Rare Mint in the Crosshairs

FNPS has also taken the lead in defense of the blushing scrub balm (Dicerandra modesta). Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise, an arm of the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), is now completing an Alternative Corridors Evaluation for a proposed extension of the Central Polk Parkway. Several of the alternative corridors being considered would impact the Horseshoe Scrub Tract of the Lake Marion Creek Wildlife Management Area, which is the site of the only known natural occurrence of this federally endangered mint.

We wrote a letter to FDOT opposing all routes that would directly or indirectly impact the species, and distributed two action alerts asking members to contact FDOT. A route that would have bisected the Horseshoe Scrub site was rejected by FDOT shortly after we submitted our comments. Unfortunately, the two corridor routes still being considered would impact the site indirectly by curtailing the ability of the FWC/SFWMD team managing the site to continue using prescribed fire. Both corridors would also traverse the site of The Natives, a well-known native plant nursery owned by FNPS founding member Nancy Bissett. Much of the nursery site is scrub habitat protected by a conservation easement held by Green Horizon Land Trust. A number of rare Lake Wales Ridge endemic scrub plant species are present there.

F NPS has been monitoring and restoring the Horse Creek home of blushing scrub balm since 2018 using federal endangered

species grant funding administered by the FFS. We have also been holding an annual Dicerandra Day event since 2022 to raise awareness of the threats to this beautiful and fragrant genus. The habitat of this species has been whittled away to a single protected site by the double hit of agricultural and residential development and fire suppression. Climate change has also been implicated as a threat to the survival of the species – visit this link for more information ( https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/csp2.621).

We have received excellent media coverage about this issue: FNPS President Gene Kelly was interviewed on the Florida Folk Show and WUFT, and Valerie and Gene were interviewed together for the Florida Spectacular podcast and by WFLA Channel 8 News. FDOT is planning public meetings in the fall to announce a final route, and we will be rallying to stop this destructive road. We hope you will take part. The best way to stay informed about this topic is to sign up for FNPS action alerts.

A Banner Year in Conservation Advocacy

O verall, we have had a banner year in conservation advocacy. Reporter James Call recognized this in the Tallahassee Democrat, citing the Florida Native Plant Society among the coalition of groups that “opposed oil drilling and proposed development at state parks, and feared the land swaps would signal conservation land bought by taxpayers could be bought by developers.” We’re also experiencing interest by television journalists in plant conservation, above and beyond the obvious interest in general environmental issues spurred by statewide protests over the Great Outdoors Initiative.

Quick Response Aided by FNPS Action Alerts

Thank you to the many FNPS members who responded to our email and social media alerts. Because bills can be changed rapidly in committee, quick action is essential. FNPS had to issue two separate alerts in order to keep the State Park Preservation Act bill strong and an additional alert to encourage the governor

to sign it. His signature in May concluded a nine month saga to keep incompatible development out of Florida’s state parks.

F NPS sent out 15 action alerts over the course of this legislative session outlining conservation issues to our list of more than 1,800 subscribers. But the need for action doesn’t end with the legislative session. We most recently alerted members to the threat the construction of an immigrant detention center would pose to the ecological health of the Big Cypress National Preserve

Above, left to right: Blushing scrub balm (Dicerandra modesta) in flower at the Horse Creek Tract of the Lake Marion Creek WMA near Davenport. Photo by Valerie Anderson. Nancy Bissett with a map of the proposed road corridors threatening The Natives plant nursery, as well as scrub habitat protected by a conservation easement. Photo by Melissa Fernandez-de Cespedes. FNPS President Gene Kelly (right) with Senator Ana Maria Rodriguez, Chair of the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources and Gil Smart, Policy Director for Friends of the Everglades. Photo by Luke Strominger.

FNPS Martin County Chapter members Mike Glynn and Marjorie Shropshire support keeping Big Cypress National Preserve wild at a rally held at the old jetport site off Tamiami Trail, where an immigrant detention facility has been constructed. Photo by Shelley Mansholt Thomas.

and the wider Everglades ecosystem. The Florida Native Plant Society opposes the development of this facility based on the certainty it will result in negative environmental impacts. At least 15 listed plant species are known to be present within or proximate to the site. Undisturbed upland fragments are likely to feature endangered Rockland Hammock habitat, one of the rarest habitats in Florida, and one that is extremely sensitive to even minute changes in water levels.

P ublic use of the nearby Oasis Visitor Center (the southern terminus of the Florida Trail), the surrounding Big Cypress Wildlife Management Area, and its hiking and paddling trails may be curtailed or precluded entirely by the presence of the detention facility. In addition, the Big Cypress Preserve is the only unit of the National Park system east of Colorado that has been formally designated an International Dark Sky Area,

and the designation is maintained through adherence to strict guidelines on nighttime lighting that will doubtless be violated by placement of a major detention facility. FNPS will continue to press our objections to this project.

About the Authors

To help FNPS continue to protect native plants and the conservation lands that support them, sign up for FNPS Action Alerts on the FNPS website (https://www.fnps.org/news/alert/email-sign-up).

Valerie Anderson is FNPS Director of Communications and Programming. Eugene Kelly is President of FNPS, and leads policy making initiatives for the society.

Article by Roger L. Hammer

A New Orchid in Town

It’s always exciting to photograph a Florida native wildflower that I’ve never seen before, and the excitement peaks when that wildflower happens to be a native orchid. There are now 120 orchids that have been recorded growing wild in Florida (107 native). One endemic species, Govenia floridana, is presumed extinct and six other species are believed to be extirpated from Florida.

It is interesting that Florida more than doubles the number of native orchids found in any other state, and it surprises most people to learn that there are 33 orchids native to Alaska, with only three species native to Hawaii. One reason why Florida’s flora is so rich in orchids is due to natural range expansion of epiphytic orchids from the American tropics, especially the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Epiphytic orchids, or those that grow on trees, are typically far less cold tolerant than terrestrial orchids, and the green-fly orchid (Epidendrum conopseum) is the only epiphytic orchid in the United States that ranges beyond the Florida border, northward into South Carolina.

The newest addition to Florida’s native orchid flora is Spiranthes igniorchis, a terrestrial species first described in 2017 by Matthew Pace, Steve Orzell, Edwin Bridges, and Kenneth Cameron. At the time, it was only known to occur at the Avon Park Air Force Range in Polk County, but was later discovered at the adjacent Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park in Okeechobee County, and in early September 2024, a single flowering plant that has been identified as this species was seen and photographed by Joe Montes de Oca in the Three Lakes Wildlife Management Area in Osceola County. It is a member of a group of orchids called “ladies’-tresses” for the small flowers that typically spiral up the stem, like braided hair. The genus name, Spiranthes, relates to this same trait.

The name igniorchis translates from Latin to “fire orchid,” for its reliance on fire to maintain its existence in the dry, sandy prairies of Central Florida, which it shares with gopher tortoises and burrowing owls. This orchid very closely resembles another species called Spiranthes longilabris, which shares the same habitat, but it blooms in November and December, while Spiranthes igniorchis blooms in August and September.

Left: Fire ladies'-tresses (Spiranthes igniorchis) in bloom at Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park. Photo by Roger L. Hammer.

And this is why it was called a ‘cryptic’ species in the publication where it was described, meaning it is morphologically indistinguishable from one or more other species.

On Sunday, September 1, 2024, my wife, Michelle, and I met up with a friend for the 240-mile drive from Homestead up to Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park after I had heard that Spiranthes igniorchis had been seen flowering at the Avon Park Air Force Range, just a few days earlier. That site is a bombing range with very restricted public access, so I decided to take my chances finding it at Kissimmee Prairie, where it had been

seen the previous year by my friend Chris Evans, who met us at the park. Upon arrival, we embarked on a two-mile hike in the sweltering heat and humidity. Once we entered the dry prairie, the only shade we had was when a caracara or a vulture flew overhead, but we persevered and made it to an area close to where Chris had found the orchid the previous year, and I was elated when he exclaimed that he had found a plant in flower. A more thorough search in the immediate vicinity revealed a total of 18 plants in bloom, with one forming seed pods. Very few people have ever seen this orchid, so it was quite a special treat.

So, after admiring and photographing it, we began our long trek back, but we were blessed with a bit of cloud cover, as well as a summer rainstorm that helped cool us down slightly. The reward of finding Spiranthes igniorchis in bloom was well worth the misery, and I would gladly do it again.

References

Pace, M. C., Orzell, S. L., Bridges, E. L., & Cameron, K. M. 2017. Spiranthes igniorchis (Orchidaceae), a new and rare cryptic species from the south-central Florida subtropical grasslands. Brittonia, 69(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-017-9483-3

About the Author

Roger L. Hammer is an award-winning professional naturalist, author, botanist and photographer. His most recent books are Paddling Everglades and Biscayne National Parks and Foraging Florida – Finding, Identifying, and Preparing Edible Wild Foods in Florida Find him online at https://www.rogerlhammer.com/

The author photographing Spiranthes igniorchis in Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park. Photo by Chris Evans.

The Florida Native Plant Society PO Box 5007 Gainesville, FL 32627

FNPS Chapters and Representatives CHAPTER REPRESENTATIVE E-MAIL

1 Broward................................................................Tiffany Duke tada duke@yahoo.com

2. Citrus ........................................................Ellen McNally ................................................ekmcnally@yahoo.com

3. Coccoloba .............................................Ben Johnson ..................................................bcjohnson0831@gmail.com

4. Conradina ..............................................Martha Steuart ............................................mwsteuart@bellsouth.net

5. Cuplet Fern.............................................Alan Squires ..................................................asquires600@gmail.com

6. Dade ..........................................................Riki Bonnema ...............................................rikibonnema@gmail.com

7 Eugenia ...................................................David L. Martin .............................................cymopterus@icloud.com

8. Heartland ...............................................Gregory L. Thomas ....................................enviroscidad@yahoo.com

9. Hernando ...............................................Janet M Grabowski ....................................jggrenada@aol.com

10. Ixia ..............................................................Cate Hurlbut ..................................................catehurlbutixia@yahoo.com

11. Lake Beautyberry .............................Grace Mertz ...................................................gmer98@yahoo.com

12. Longleaf Pine ........................................K imberly Bremner......................................kimeeb32@gmail.com

13 Magnolia ................................................James Cooper ...............................................james.cooper@fdacs.gov

14. Mangrove ...............................................Linda Wilson .................................................linda wilson.frontierweb@frontier.com

15. Marion Big Scrub ..............................Deborah Lynn Curry..................................marionbigscrub@fnps.org

16. Martin County .....................................Peter Grannis ...............................................pbgrannis@gmail.com

17. Nature Coast ........................................Diane Hayes Caruso .................................dhayescaruso@hotmail.com

18. Naples ......................................................Ben Johnson ..................................................bcjohnson0831@gmail.com

19. Palm Beach County .........................Vacant ...............................................................palmbeachfnps@gmail.com

20. Passionflower.......................................Melanie Simon .............................................msimon@fnps.org

21. Pawpaw ..................................................K aren Walter .................................................karenlw72@gmail.com .......................................................................Amy Legare ....................................................amy57vt@gmail.com

22 Paynes Prairie .....................................Sandi Saurers ...............................................sandisaurers@yahoo.com

23. Pine Lily ..................................................Dana Sussmann ..........................................dana.sussmann@fdacs.gov

24. Pinellas ....................................................David Perkey .................................................dnperkey@gmail.com

25. Sarracenia .............................................Lynn Artz lynn artz@hotmail.com

26. Sea Rocket ...........................................Elizabeth Bishop .........................................izbet@aol.com

27. Serenoa ...................................................Trent Berry ......................................................trentberry123@gmail.com

28. Suncoast ...............................................Merrilee Wallbrunn ...................................mwallbrunn@hotmail.com

29. Sweetbay ..............................................Mary Mittiga ..................................................mittiga@aol.com

30. Tarflower ................................................Deborah Ferencak .....................................deborahann200@gmail.com

31. The Villages ...........................................Bob Keyes .......................................................bob.keyes@qcspurchasing.com

BECOME A MEMBER OF FNPS:

It's easy! Simply contact your local Chapter Representative, or call, write, or e-mail FNPS. You can also join online by using the QR code, or visiting https:// www.fnps.org/support/member

Contact the Florida Native Plant Society: PO Box 5007 Gainesville, FL 32627. Phone: (321) 271-6702 Email: info@fnps.org Online: https://fnps.org

Submit materials to PALMETTO: Contact the Editor: Marjorie Shropshire Visual Key Creative, Inc.

Phone: (772) 285-4286

Email: palmetto@fnps.org