FAMILY JUSTICE JOURNAL

THE HARM OF DISCONNECTION

THE HARM OF DISCONNECTION

Summer 2023

Introduction

006 The Need to Prioritize Relational Health

Jerry Milner & David Kelly

Directors of the Family Justice Group

Foreword

008 Bruce Perry

Principal of The Neurosequential Network

Perpective

012 The Call

Nicole Kati Wong, J.D., M.S.T.

057 A Better Way Nurturing Freedom Dreams Through a Principled Struggle

Corey Best

Founder of Mining for Gold

Tiffany Csonka

Parent Knowledge Curator

Christina Romero

Parent Knowledge Curator

Pasqueal Nguyen

Parent Knowledge Curator

014

Features Acknowledging & Addressing the Impact of Loss, Grief, & Relational Connection for Youth in Foster Care

Monique Mitchell, PhD, FT

Executive Director of Life Transitions International Director of Training & Translational Research

National Director of L.Y.G.H.T. at Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families

020 The Ineffable Significance of Kinship

Mark Testa, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

026 The Enduring Pain of Permanent Family Separation

Erin Carrington Smith

J.D. Candidate, University of Baltimore School of Law

Shanta Trivedi

Assistant Professor of Law and Faculty Director, Sayra & Neil Meyerhoff Center for Families, Children & The Courts, University of Baltimore School of Law

034 A Consciousness of Connection is Our Only Hope

Elizabeth Wendell & Kevin Campbell

Founders of Pale Blue

042 Family Separation as Terror

011 Beyond the Silence

Nicole Kati Wong, J.D., M.S.T.

041 Ever Since I was a Little Kid

056 Waves

060

Kaylah McMillan

Holly Lazo

Poetry Silent Tears

Sawara Robinson

061 Can I Be Myself

Sawara Robinson

Alan Detlaff Professor, University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work

048 Promoting Child & Collective Wellbeing Through Indigenous Connectedness

Jessica Saniguq Ullrich Assistant Professor, Washington State University

Reflection

062 A Discussion with Victor Sims on the Power of Connection

Victor Sims

Harini Pootheri is the artist for the cover art. She is an incoming junior at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, studying Computer Information Systems and Data Science. As part of her Ethnic and Women’s Studies course in the summer of 2021, Harini created the artwork pictured here titled “Lotus Flower: The Human Desire for Freedom” as part of her final project on foster youth and incarceration. So many children are stuck in the foster care-to-prison pipeline. Harini has witnessed many youth succumb to the foster care-to-prison pipeline during her time in the foster care system. Yet despite the unfortunate perpetuation of the pipeline, Harini would like to highlight that growth is possible and the human desire for freedom triumphs all.

The Family Justice Journal is committed to featuring the art and poetry of individuals directly impacted by the child welfare system in each issue.

Christopher Baker-Scott

Executive Director & Founder SUN Scholars, Inc.

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

University of Washington Seattle Associate Professor

Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute

Director of federal policy for Partners for Our Children

April Lee

Director of Client Voice Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Dr. Melissa T. Merrick

President and CEO

Prevent Child Abuse America

Lexie Gruber Peréz Service Design Masters Candidate

Royal College of Art in London

Former Senior Advisor on Child Welfare in the Biden Administration

Jey Rajaraman

Associate Director, Center on Children and the Law, American Bar Association

Former Chief Counsel, Legal Services of New Jersey

Vivek Sankaran

Clinical Professor of Law, University of Michigan, Michigan Law

Shrounda Selivanoff Social Services Manager

Washington State Office of Public Defense Parents Representation Program

Victor E. Sims, MBA, CDP

Senior Associate Family Well-Being Strategy Group

The Annie E. Casey Foundation

Paul Vincent, MSW

Former Alabama Child Welfare Director Consultant and Court Monitor

Justin Abbasi

Medical Student, University of California, Los Angeles

Co-Founder, Harbor Scholars: A Dwight Hall Program at Yale

Laura W. Boyd, Ph.D. Owner and CEO, Policy & Performance Consultants, Inc.

Angela Olivia Burton, J.D. Special Counsel for Interdisciplinary Matters Office for Justice Initiatives New York State Unified Court Systems

Melissa D. Carter, J.D. Clinical Professor of Law, Emory Law

Kimberly A. Cluff, J.D. MPA Candidate 2022, Goldman School of Public Policy

Kathleen Creamer, J.D. Managing Attorney, Family Advocacy Unit Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

Associate Professor, Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Center

Director of Federal Policy for Partners for Our Children School of Social Work, University of Washington Seattle Adjunct Faculty, Evans School of Public Policy and Governance

Yven Destin, Ph.D.

Educator and Independent Researcher of Race and Ethnic Relations

Paul Dilorenzo, ACSW, MLSP National Child Welfare Consultant

J. Bart Klika, MSW, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer, Prevent Child Abuse America

Heidi Mcintosh

Principal, LGC CORE Consulting, LLC

Kimberly M. Offutt, Th.D.

National Director of Family Support and Engagement Bethany Christian Services

Jessica Pryce, Ph.D.

Director, Florida Institute for Child Welfare Florida State University

Delia Sharpe, Esq. Executive Director, California Tribal Families Coalition

Mark Testa, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Wendel, MSW, LSW Co-Founder, Pale Blue International Consultant, Family Well-Being and Mental Health Systems

Shereen White, J.D. Director of Advocacy & Policy, Children’s Rights

Cheri Williams, MS

Senior Vice President of Domestic Programs

Bethany Christian Services

The Family Justice Group is grateful for the financial sponsorship of this issue of the Family Justice Journal by the Institute for Relational Health (IRH) at CareSource. We are happy to advance the work of the IRH in promoting relational health for families, children, youth and communities, particularly those impacted by our child welfare, juvenile justice and mental health systems and individuals with disabilities. We believe that discussing and bringing to light the harms of disconnection are necessary acknowledgements of the critical importance of relational health in all our lives.

Child welfare in the United States is both a symptom and a cause of relational poverty. As a symptom, it reflects what can happen when families are socially isolated and without the necessary social capital or resources to help them through adversity. As a cause, it erodes family integrity. With intention, laws have been crafted to punish vulnerability, expedite the severance of family relationships, and incentivize the redistribution of other people’s children.

Less than half of children separated from their parents to foster care ever return home. Discriminatory rules and policies disqualify families from doing what family does best---care for their loved ones. The “better safe than sorry” mentality to child safety continues to preempt a child’s sense of connection and belonging to their family, community, and culture. This is a direct threat to their well-being and jeopardizes the relational, physical, mental, and spiritual health of children and youth.

Relational health (connection and belonging) is essential to our individual and collective well-being as human beings in the world. Somehow, however, this most essential and defining aspect of being human has been overshadowed or cast aside in the industry known as child welfare.

Services reign supreme in the industry, and the industry has great impact on policy making nationally. Its main interest is to remain in business. This has resulted in a fixation on clinical services and proprietary models, rather than proactive family support. It sustains a narrative that pathologizes the conditions families are forced to live in or with, especially poverty and the trauma of racism.

Most often we do not see children and parents within the context of their family, culture, or community. The Indian Child Welfare Act is perhaps the lone exception of a law that does, and of course it is subject to constant attack because its purpose and efficacy are threats to the status quo. Instead, we focus on adversity and individual deficits, maladies, and extreme examples— again, most often caused by societal conditions. We then punish children and their parents for those conditions.

This is an inhumane approach that reflects a fragmented and myopic view of children and their parents. It fails to see complete human beings or acknowledge the context of their lives. It fuels the creation of one size fits all menus of research-based interventions and manuals designed to fix isolated parts of people. It ignores what we know about the importance of connection and belonging and prioritizes processes and transactions over well-being. This benefits systems and purveyors far more than families.

For example, the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) and the clearinghouse it established are designed to focus primarily on rating and approving clinical interventions to fix problems after they have occurred. It does not fund critical support for well-known needs before problems become crises. Nor does it fund community derived and provided solutions. The industry needs the problems to persist. It profits from negative views and perceptions of low-income families and families of color. It is built upon prejudice.

As a field we have convinced ourselves that we are doing right by children while outcomes and evidence (especially the accountings of people impacted by the system) say otherwise. We continue to invest our time, energy, and resources in getting better at maintaining the existing framework of investigating and separating families, including incessant efforts to increase child abuse hotline reporting and non-stop foster parent recruitment that favors the number of beds over the strength of connection. These approaches guarantee more trauma and disconnection and reinforce the inequities that were woven into child welfare from the beginning.

There are examples from other cultures and nations that recognize that supporting families is the best way to keep children safe and healthy and that communities are best situated to provide that support. For example, tribes in the United States and indigenous communities in other parts of the world have sacred and historical traditions of keeping family members connected to one another, their clans or tribes, culture, land, and world in which they live. Indigenous world views recognize that strong and healthy individuals make for strong and healthy communities, and that one relies on the other---there is deep value in interconnection.

Many Tribes and Tribal Nations have resisted efforts and policies that support unnecessary separation of families, removal of children from their cultures and communities, and severing child-parent ties. They rightfully reject the notion of termination of parental rights as a legal fiction and an act of great harm. When these efforts have not been successful, we see adults who have lost their sense of self, cultural heritage, and connection to essential relationships---forced to live with grief, depression, and worse because of what has happened to them. Our child welfare system has much to learn from the wisdom of indigenous communities.

There is overwhelming evidence of the centrality of meeting basic needs, e.g., food, clothing, housing, economic security, childcare and relational health. With this knowledge, the federal government can lay the foundation for a just and humane direction that promotes true child welfare and family well-being. The Surgeon General’s recent Advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community unequivocally identities loneliness and isolation as a national epidemic. This is an important start and opportunity to change our orientation. It needs to be followed by a national investment in relational health, including a realignment of Medicaid that recognizes efforts to promote connection and belonging as essential, preventative medical care that directly impacts physical and behavioral health. We must also prosecute the infrastructure that causes and exacerbates isolation and loneliness.

There are longstanding federal structures, programs and funding streams that are deeply destructive to families and cause disconnection and egregious inequity. We should cease to defend and maintain them. For example, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) includes mandatory reporting requirements that lead to over-surveillance of poor families and families of color. The Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) includes draconian termination of parental rights provisions that are misaligned with what we know about substance misuse treatment and emerging from deep poverty. Moreover, programs and funding that could and should be helpful are commonly misused. Most notably, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is utilized by many states to investigate families rather than provide them with economic support and mobility.

In this first issue of the Family Justice Journal, authors confront the trauma of family separation through a lens of loss of connection and belonging and the often-irreparable grief it causes children and parents. The issue calls for the end of seeing poverty, trauma, and disease as parental shortcomings. It exposes how we weaponize grief to justify removal, termination of parental rights and other practices that cause harm in the name of good. Contributors challenge all of us to mobilize around relational health and advance restoration and healing to keep families and communities strong and connected. Such a direction will benefit all.

Jerry Milner

David Kelly

Jerry Milner

David Kelly

Ann T. Dinh Design Consultant

Ann T. Dinh Design Consultant

Like all species on Earth, we have evolved unique genetic capabilities that have allowed us to survive and thrive over thousands of generations. At the heart of these ‘gifts’ is our connectedness –our bonds with others make us part of a greater whole. For 250,000 years humans lived in small, developmentally heterogeneous groups. In these 20-60 member ‘clans’ the elderly, adults, youth, child, toddler and infant lived in close physical proximity. Physical, emotional and social interactions were dense and continuous. Caregiving ratios for children under three were 4:1 not the ‘enriched’ 1:4 ratio that today’s childcare settings brag about (1/16th the relational density of our ancestral child rearing environments). We are a social species; each of us is fundamentally interdependent upon many others – past and present, known and unknown. This foundational capacity to form and maintain relationships – to communicate, commune, couple and create with others – is responsible for the survival of every human being alive today – and every human being who has ever lived. It is no surprise then, that the complex and diverse capacities to manage stress in the individual body are intertwined with the complex and diverse systems involved in connecting with others. Connectedness, stress regulation, and health in all domains – physical, emotional, social and cognitive - are intertwined.

Another ‘gift’ of our species is the capacity of the human cortex to absorb and store remarkable volumes of information per second – and then make that ‘information’ available for ongoing analysis, processing, revisiting, revising and inventing. This is what has allowed us – over thousands of generations – to discover, invent and change the ways we live and live together. Innovations in cultivation, domestication of animals, communication, transportation, and complex social structures and so much more have resulted in our modern world. This process of sociocultural evolution has dominated human history for the last 20,000 years. As our social structures have become larger and more complex, we have codified practices, created programs, defined policy and law to guide

us through the inevitable set of problems resulting from this inventing process. Each generation has the task of problem-solving about the issues created by the choices of previous generations. Well-intended changes in systems, or practice, or policy often cause new problems. The un-ending process of creating a future will always involve review and reflection on the choices of previous problem solvers – and making tweaks, addendum, additions, subtractions to better meet the current needs and interests of a population. This ongoing inventing process is complicated by the rapid rate of changes in the world – and in the ‘inventing’ process that has accelerated dramatically in the last 100 years. The rate of creating innovations is faster than our problem-solving processes.

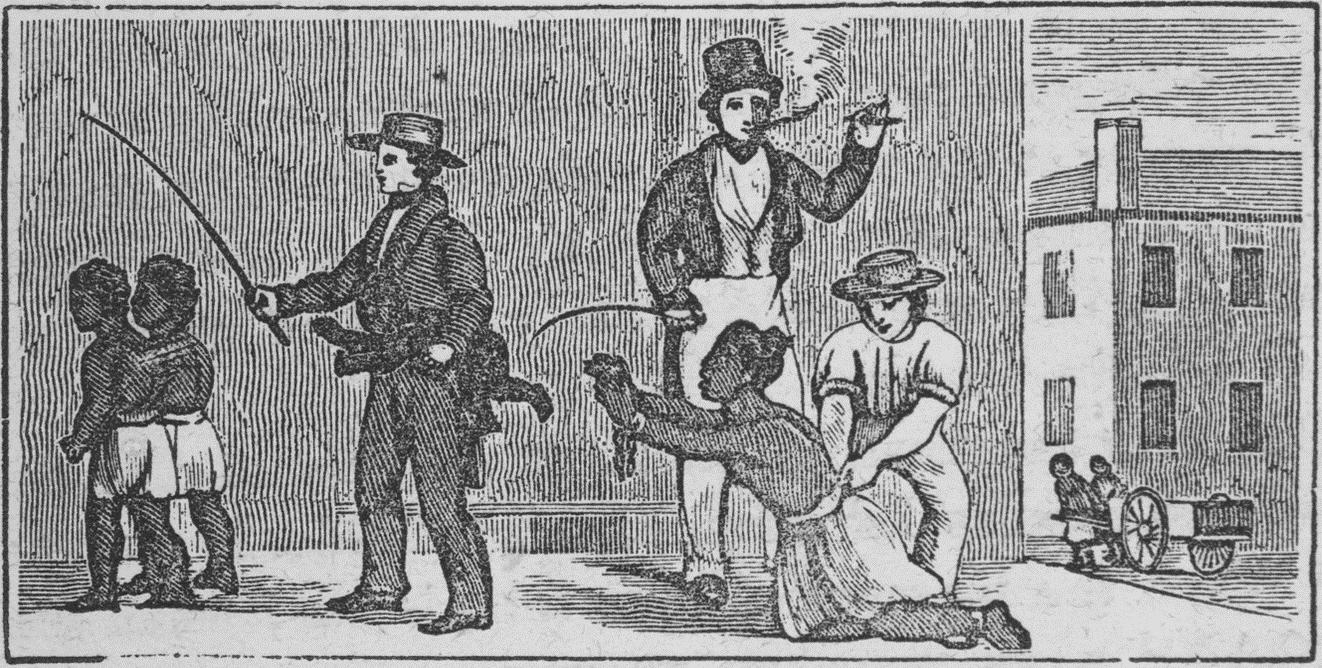

One of the most significant consequences of this rapid ‘modernization’ has been the relative ignorance and neglect of one of the fundamental needs and strengths of humans – to belong. Being connected to and actively engaged with others in your ‘clan’ confers physiological, emotional and social buffering from present stressors and an opportunity to heal from previous adversities. Belonging helps make you healthy, helps keep you healthy and helps you heal. Yet so many of our innovations and advances actually fragment our social connectedness (e.g., increasing screen time) in subtle but powerful ways. And many of our other innovations and policies INTENTIONALLY fragment family, community and culture. The objective of colonizing practices, i.e., ‘civilizing,’ ‘pacifying,’ ‘modernizing’, were to undermine family, community and cultural bonds to facilitate the introduction of ‘other’ ways of being, thinking and living (usually only giving partial access and privilege to these ‘new ways’, thereby keeping the colonized at the bottom of a transgenerational power differential intended to maintain the power and wealth of the colonizers). In many ways, our current social systems retain the fundamentally colonizing/feudal features that are endemic to large hierarchical systems. It should be no surprise that Aboriginal children and youth are over-represented in Australia’s child welfare and juvenile justice

system (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2007) or that First Nations children and families are most fragmented by current social policies and systems in Canada, or that the transgenerational impact of slavery and ongoing intentional disenfranchisement and marginalization of enslaved peoples results in the overrepresentation in our ‘modern’ child welfare system. Only with an awareness of these features can we – the current generation of problem solvers and inventors – adequately address and remedy these shortcomings.

This issue of the Family Justice Journal is all about that process. A group of innovative scholars and leaders are writing about the catastrophic impact of fracturing these connections. The long-standing policies of child welfare to remove children from parent, family, community and culture have only exacerbated the problems they were intended to remedy. These scholars give us hope and direction by these reflections.

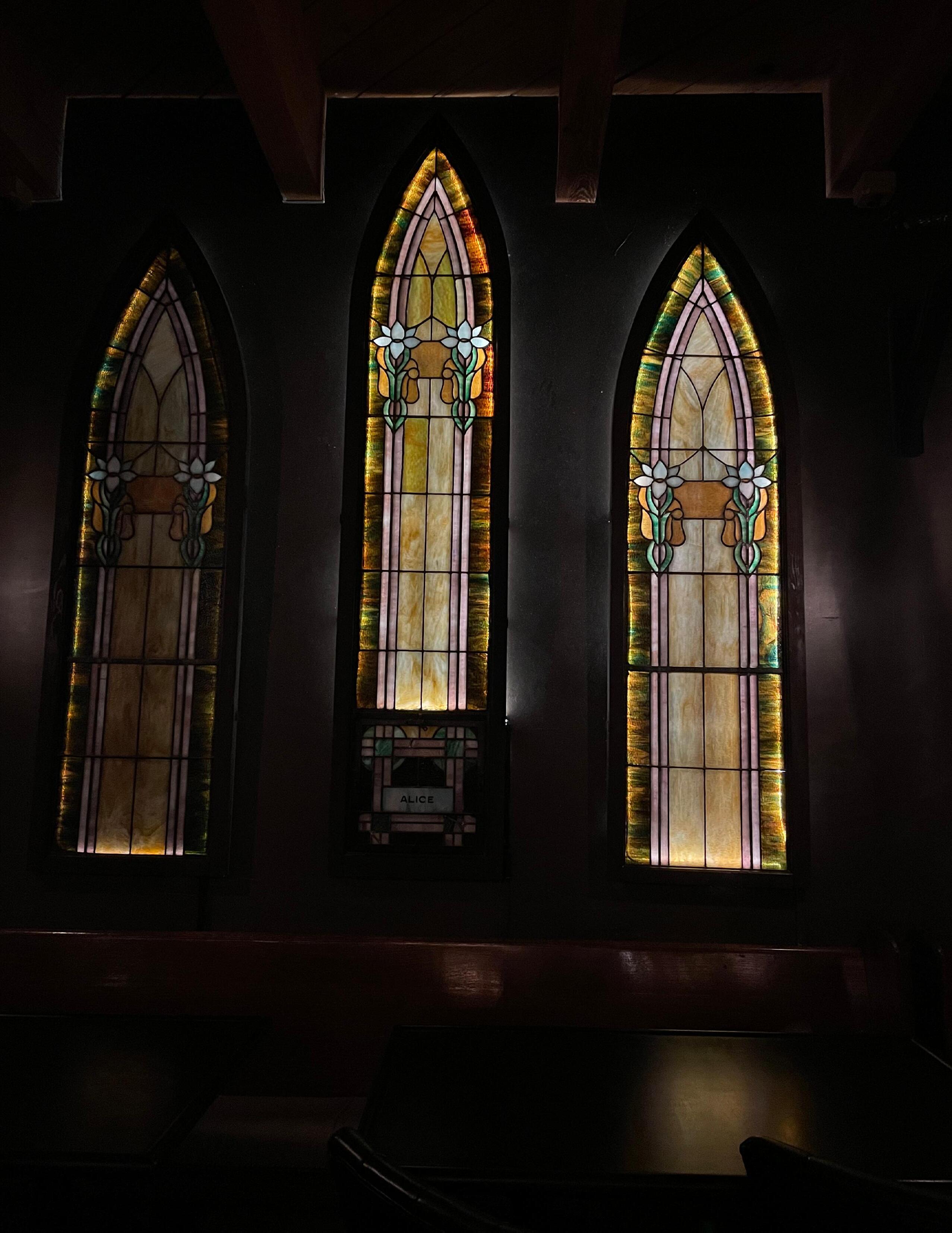

My journey in this area started over thirty years ago when I was asked to evaluate a 14-year-old

girl who was being ‘hospitalized’, i.e., imprisoned, for ‘conduct disorder.’ Briefly, at age 13 she had disclosed sexual abuse by her step-father to a teacher. The resulting CPS investigation resulted in her removal from the home (they kept her 12-year-old sister in the home). Prior to this, she had been a good student, part of a church youth group, an active and successful athlete in soccer and softball, regularly visited her grandparents who lived in her neighborhood – and had never had behavioral, emotional, social or academic problems. After removal she was put in foster care in a completely different part of the city – away from school, friends, teammates, family. She would run back to her community and stay with friends. Again, and again. She started to fail in school, ‘disrespect’ her foster family, and became very sad. The legal proceedings dragged on – each time she ran away she had more restrictions. She became angrier and sadder and more isolated. Finally, she required ‘hospitalization’ to prevent her from running away. I met her, found nothing wrong with her aside from a normal set of feelings, thoughts and behaviors given the situation. I will

“The long-standing policies of child welfare to remove children from parent, family, community and culture have only exacerbated the problems they were intended to remedy.”

never forget her statement – “Why am I the one who has to get punished when he is the one who hurt me? He keeps his bed, his house, his job, his friends and I am the one who loses everything. It’s not fair.” And I would add…it’s not moral, it’s not just, it’s not effective and “our” interventions just hurt her. For the next thirty years I saw hundreds of similar examples of iatrogenic problems –physiological, social, emotional and behavioral –caused by the very interventions in child welfare, education and mental health – that were supposed to be helping children and families. At the core of all these misguided interventions is a fundamental ignorance about basics of human development, the principles of brain organization and functioning, the importance of stress response malleability and flexibility, the power of early childhood experiences and the importance of connectedness.

The high malleability – therefore, the high vulnerability – of the infant and young child is of particular importance in child welfare. Separation from family is most devastating when children are young; In 2021, 203,770 children entered foster care in the US. Children ages one to five are 29 % of these. Over 2021 391,641 children were living in foster care. Of these, 33 % were one to five and 7% were ‘babies.’ (AECF, 2022)

While disruptions of connection for youth are bad; disruptions and separations of primary relational experiences early in childhood are catastrophic. In our work to study the impact of experiences (good and bad) on development (Perry, 2009), the valence of early life relational connection appears to be the most powerful determinant of many mental health outcomes later in life (Hambrick, et al., 2018). We also find that measures related to ‘connectedness’ during development are better predictors of “adversities” despite the current popular over-focus on ‘ACEs” as determinative in health outcomes. In addition, we find again and again that the major predictor of current functioning is the current state of connectedness (Hambrick, Brawner & Perry, 2019). Simply stated, connectedness is at the heart of all human health, creativity, productivity and humanity. And any practice, program or policy that actively disrespects this will increase risk, erode resilience and, ultimately, be a detriment to our progress as a species. The good news is that the importance of social engagement and relational health is emerging in many fields –the Surgeon General has written a book (Murthy, 2020) and recently a major policy paper (Office of the Surgeon General, 2023) about the importance of connectedness, for example.

Sadly, connectedness, community and culture have not been ‘centered’ in our current child welfare programs and practices. This issue of the journal has a focus on the enduring, multi-dimensional negative impact that the intentional, systemic efforts of child welfare policy and practice have on the very children, families and communities these systems intend to help. An essential element of learning from the authors in this issue of the journal is to acknowledge the limits and biases of our own educational, professional and cultural experiences. It is likely that a ‘defensive’ stance will be elicited when confronted with the harsh reality of the failures of our systems; when using our the ‘best intention’ lens we often minimize or avoid the reality of the overwhelming and sobering negative impacts of our child welfare interventions. I would ask that the reader remember that the best intentions developed and delivered within a patriarchal, colonizing framework are never good for the colonized.

AECF (2022) 2022 Kids Count Data Book. Annie E. Casey Foundation (https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf2022kidscountdatabook-2022.pdf Office of the

Atkinson, J., & Atkinson, R. (2007). Trauma, transgenerational transfer and healing indigenous people. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 5(3), 274-282.

Hambrick, E.P., Brawner, T. & Perry, B.D. (2019) Timing of early life stress and the development of brain-related capacities. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13:183. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00183

Hambrick, E.P., Brawner, T., Perry, B.D., Brandt, K., Hofeister, C. & Collins, J. (2018) Beyond the ACE Score: Examining relationships between timing of developmental adversity, relational health and developmental outcomes in children Archives of Psychiatric Nursing DOI:10.1016/j. apnu.2018.11.001

Murthy, V. H. (2020) Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World. Harper Wave

Perry, B.D. (2009) Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: clinical application of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma 14: 240-255,

Surgeon General. (2023). Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General.

Nicole Kati Wong, J.D., M.S.T.

Nicole Kati Wong, J.D., M.S.T.

I watched the flickering of sirens, Red and blue hues, never lessening. The city that never sleeps grew silent, And the quiet was truly deafening. Ripped from our roots (but still expected to grow), Never to see the stars the same way. Lived in many houses, never a home. They said it was care; that’s just a word they say.

A system of pain, waves of rejection, No actual meals—just leftovers and scraps. Blood in our veins and blinding affection, Still not as binding as our shared need of maps.

I was the whisper, but you knew how to shout. In a crowded room, your cheer still rings out. But, I hated when you weren’t around. The music still played, but I heard no sound.

You were born for days of adversity. Could that I would wrap a thousand thanks. Through all my outstanding absurdity, You let me shine, yet, in the sun, you never bathed.

They think I had it bad, but you took the brunt. You always took the lead, and I followed as the runt.

My lashing was a drop and yours was an ocean. You protected my youth; I’m sorry yours was stolen.

You crawled so I can stand. You cried so I did not fret. They think I overcame alone, But I shall never forget.

I can never say it enough (and it’s too hard to say it face to face): You are a brother of worth. Beyond the silence, always hear this praise.

stories of children being separated from parents or siblings, not due to death or necessity, but rather due to such reasons as cultural insensitivity or systemic glitches that have children entering care whenever a (well-meaning but not always well-founded) mandatory reporter call is made.

The disproportionate number of children of color in foster care is so defining a characteristic of the system that it speaks volumes of its ineptitude for cultural humility. How many children of immigrant families have entered care because their parents affectionately used ancestral, medicinal practices that were (ironically) mistaken for physical abuse? How many foster children are placed in remedial courses because of language barriers or gaps in education due to frequently transferring foster homes and schools? How many guardians are viewed as unfit caretakers because they could not afford to miss work (again) to show up to court, school conferences, etc., without the risk of job loss? How many siblings are kept apart due to assumptions that their bond is indicative of incest, rather than being viewed as a yearning for familiarity (i.e., when one sibling leaves their foster home bed each night only to be found in their sibling’s bed the next morning)? How many children are so isolated from the ethnic, cultural, and spiritual values of their birth families because they are only permitted a one-hour weekly visit—if that—with their parents? How many families have been torn apart? How many more have to be? At what point will we reshape what care really means?

Can you recall a time when you were in the middle of a phone call and—suddenly—the line went silent? It may have been a pleasant conversation or perhaps you were extremely grateful for the interruption, but whatever your feelings were, it is likely that you had every ability and freedom to reconnect with the person on the other line. The same cannot be said for children who enter the foster care system and are abruptly disconnected from their families, friends, communities, and environments.

As an educator, advocate, and attorney, the one constant I have observed about the adolescent journey is that connection is crucial. When my students made text-to-self connections, there was a more potent underscoring of information than when they felt disassociated from the material. When those of us with lived experience in the foster care system champion change, we embrace the echo of our experiences and seek to bridge resources, institutions, and innovation. When it comes to the wellbeing of a child, it takes the fused understanding of various professionals to determine what “best interest” means. Yet, in spite of the universal, conventional understanding that there is a correlation between interdependence and advancement, the system that oversees child welfare is the very one subduing the healthy development of our youth. We know this because there are countless

The vulnerable population of youth in foster care undergo traumas that are invisible and incomprehensible to their peers. Due to the many ways foster children are separated from meaningful support systems, they experience higher levels of mental health issues, emotional dependencies, physical self-harm, academic failures, etc., than the general population while still being expected to perform at the same rate as their peers As they become young adults, they experience higher levels of poverty (i.e., homelessness not too long after exiting foster care), criminal activity, substance abuse, etc. than the general population while still being judged for not “excelling” at the same rate as their peers. I have met countless former youth in foster care whose contribution to society is invisible and incomprehensible to their peers. Each system-driven severed connection created another obstruction to their ability to succeed and yet, their hearts still beat. In these silent heroes, there is a testament to the import of hope (the only thing sustaining the victim of disconnection).

This column has been filled with rhetorical questions and calls for action. Hopefully, unlike those moments where a phone call abruptly ends, there will be readers on the other side of these words who (value the importance of connection and) respond.

Over the past 20 years, through youth-centered research, practice, and mentorship, I’ve listened to and learned from thousands of youth in foster care as they’ve shared what it is like to experience foster care transitions. My heart has weighed heavy as youth discuss what it is like to be removed and disconnected from their families, placed into foster care, how they cope with loss and grief while navigating the foster care system, what it has been like to return or not return to their family, and all the ambiguities that further complicate their reality.

1 US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2022). The AFCARS report No. 29: Preliminary FY 2021 estimates as of June 28, 2022. Retrieved from https:// www.acf.hhs.gov/ cb/report/afcarsreport-29.

2 Mitchell, M. B. (2016). The neglected transition: Building a relational home for children entering foster care. Oxford University Press.

3 The quotes utilized in this article are drawn from personal communications with youth in research studies that I have conducted. All research studies received IRB approval and all participants granted their permission for their quotes and feedback to be used anonymously in publications and/or presentations.

4 Personal communication with youth in foster care, research participant

5 For more information on the impact of ambiguity, see Mitchell, M. B. (2016). The neglected transition: Building a relational home for children entering foster care. Oxford University Press.

Monique B. Mitchell, PhD, FT is the Executive Director of Life Transitions International and the Director of Training & Translational Research and National Director of L.Y.G.H.T. at Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. For more information, visit www. moniquebmitchell.com & www.dougy.org/lyght

Every year, more than 200,000 youth are removed from their families and placed into the U.S. foster care system.1 Each of these children are challenged by ambiguity and loss through foster care transition transactions and the introduction and dissolution of relationships.2 In this article, I draw upon the stories and quotes from children, teens, and young adults that I have been privileged to as a listener3, the research that I and others have conducted, and the lived experience of removal and disconnection for youth in the foster care system. Current challenges within the child welfare system related to becoming and being grief-informed are addressed and resources and efforts to move the child welfare field toward a more holistic and humanistic approach to supporting youth who are grieving are discussed.

6 Meyer-Lee, C., Jackson, J. B., & Sabatini Gutierrez, N. (2020). Longterm experiencing of parental death during childhood: A qualitative analysis. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 28(3), 247-256.

7 Almquist, Y. B., Rojas, Y., Vinnerljung, B., & Brännström. L. (2020). Association of child placement in out-of-home care

Acknowledging and Addressing the Impact of Loss, Grief, and Relational Connection for Youth in Foster Care

with trajectories of hospitalization because of suicide attempts from early to late adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), 1-12. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.

2020.6639

8 Mitchell, M. B. (2016). The neglected transition: Building a relational home for children entering foster care. Oxford University Press.

9 Unrau, Y. A., Seita, J. R., & Putney, K. S. (2008). Former foster youth remember multiple placement moves: A journey of loss and hope. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1256–1266.

10 Curry, A. (2019). “If you can’t be with this client for some years, don’t do it”: Exploring the emotional and relational effects of turnover on youth in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 374-385.

11Mitchell, M. B. (2017). “No one acknowledged my loss and hurt”: Non-death loss, grief, and trauma in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35, 1-9. doi: 10.1007/s10560017-0502-8

12 Herrick, M., & Piccus, W. (2005). Sibling connections: The importance of nurturing sibling bonds in the foster care system. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 845–861.

13 Wokciak, A. S., Tomfohrde, O., Simpson, J. E., & Waid, J. (2022). Sibling separation: Learning from those with former foster care experiences, The British Journal of Social Work. https://doi. org/10.1093/bjsw/ bcac204

When a youth experiences removal, they are inundated with loss from this first transaction. Most youth with whom I have worked or spoken with equate this experience to “being kidnapped,” “being tooken’,” or “ripped away.” One youth asserts, “It was a horrible, traumatizing experience for all of us – to be ripped away from your family.”4 The impact of family separation and the subsequent ambiguity, i.e., structural ambiguity, placement reason ambiguity, placement context ambiguity, relationship ambiguity, role ambiguity, temporal ambiguity, and ambiguous loss, should not be understated.5 In addition to the ambiguities that youth experience, they experience an abundance of losses. While some adults may argue that a youth does not “lose” their family when they are placed into foster care, most youth in foster care would disagree. Indeed, for them, they experience the ambiguous loss of family, e.g., parents, siblings, grandparents, etc., immediately, at the time of removal. And this loss does not go away while in foster care…it just intensifies. While not the case for all youth, terms such as “traumatic,” “heartbreaking,” and “worst experiences of my life” are the dominant themes that have emerged in youth’s stories when talking about what it feels like to be disconnected from their family and/or loved ones.

Unfortunately, the primary loss of removal can also lead to secondary losses. These losses include, but are not limited to, losses of identity, losses of community, losses of routines, and losses of self-worth. As one youth advised, “My loss was more lack of self-preservation and self-worth. I feel as if this could happen to someone no one cares about.” As illustrated by this youth’s experience, placement into foster care can also lead to a loss of hope, self-worth, and belonging. While it can sometimes be a challenge to admit this, the system, which is designed to help youth, has also harmed them and the elephant in the room needs to be addressed.

Grief is an inevitable result of loss and is commonly reduced to being “an emotion.” While grief can be expressed as emotion, it is so much more than that. Grief can be felt and manifested in our bodies, in our minds, in our spirits, and in our interpersonal relationships.

Youth in foster care have clearly expressed how they are impacted when their experiences of loss and grief are not addressed.9, 10, 11 While each relationship is unique, for youth who have been separated from siblings, this relational disconnection can be exceptionally challenging.12,13 Youth reports include, “A major loss that I had was not being able to see my sisters and being around my sisters and my family as much as I wanted to. And, having somebody that, you know, understands you that doesn’t necessarily just judge

“No one acknowledged my separation from my family. Not having acknowledgment made me feel lost.”: Unaddressed Grief in Foster Care

“You’re took away from everything that you know and love.”: The Harm of Disconnection

Sadly, grief is often overlooked and misunderstood in the child welfare system and is not adequately addressed. The challenge with this is that unaddressed and/ or unsupported grief can lead to long-term negative outcomes, including but not limited to, depression, isolation, hopelessness, suicidality, and low selfworth, just to name a few..6, 7, 8

you and just stare at you like a foster child,” and “I got taken away from my sisters, who I promised I would never let them get hurt. I was pissed and I was what most people called a troubled child or hellion.”14 As a result of relational disconnection and unaddressed grief, youth reported how they rebelled or “acted out”, felt misunderstood, did not feel a sense of belonging, and struggled with understanding their place in the world. As I have listened to how youth are impacted when their grief is left unattended, my heart falls heavy, especially when considering how proper grief-informed interventions could have minimized or mitigated these grief experiences.

The youth are telling us to listen, to really listen, to what their stories, at their heart, are telling us. Removal and separation from their families is painful, the subsequent grief resulting from separation from family, friends, homes, and communities needs to be attended to, opportunities to discuss and explore their grief is not at the forefront of service delivery, and, in the absence of these supports, youth feel “betrayed,” “hurt,” “alone,” and “unloved.” And the youth I have spoken with aren’t the only ones with this lived experience; research and conversations with youth in foster care elsewhere have also come to similar conclusions.15 With all the losses that children and youth in foster care experience, it is disconcerting that the child welfare system is not placing more emphasis on ensuring that our practices are not only trauma-informed but also grief-informed.

Being disconnected from people and places someone cares about can be a traumatic experience, as many youth have attested. The child welfare system recognizes and acknowledges the critical importance for professionals to understand the impact of trauma and to be trained on traumainformed best practices. By being traumainformed, professionals understand how youth can be impacted by traumatic experiences and ways to provide support and minimize additional trauma. In addition to understanding the impact of trauma, it is critical for child welfare professionals to also understand the impact of grief. All youth will inevitably experience loss and disconnection when entering or while in foster care, and with this disconnection comes grief. As such, it is equally

important for our child welfare system to be trained on grief-informed best practices, understanding that being trauma-informed and being griefinformed are not one and the same.

Being grief-informed involves understanding the ten core principles of grief-informed practice and how understanding and applying these principles can better assist professionals in providing personcentered support to people who are grieving.16 These best practices include understanding that grief is natural, complex and nonpathological, contextual, disruptive, person-centered, dynamic, non-finite and that people who are grieving require relational connection, perceived support, safety, and personal empowerment and agency. Ultimately, it is essential for child welfare professionals to understand the dynamic nature of grief and how to tailor their support in a way that respects the dignity and worth of each youth they are serving. Being grief-informed also involves understanding the disparities that exist in removal rates, healthcare, education, governmental policies, etc. because of discrimination against people’s races/ethnicities, beliefs, genders, socioeconomic statuses, and other attributes which make people diverse, unique, and worth of inclusion.17

While unpacking the core principles of griefinformed practice and their application to child welfare is beyond the scope of this article, there are resources available for child welfare professionals interested in providing grief-informed support to youth who are grieving. For example, The Bill of Rights for Youth in Foster Care Who are Grieving, developed by youth, outlines the ways that adult caregivers, teachers, friends, and other people in a youth’s life can support them as they navigate their grief while in, and after, foster care.18 Additionally, Tips for Supporting Youth in Foster Care Who are Grieving, provides grief-informed tips to support youth in foster care who are grieving due to separation and disconnection,19 and Now What? Tips for Teens Who are Grieving in Foster Care provides tips for teens who are grieving in the foster care system.20

Some states have started to consider how to integrate grief-informed best practices into their core principles of child welfare practice. In Utah, for example, a cross-system statewide child welfare collaborative consisting of child welfare professionals (e.g., judges, guardians ad litem, human services staff, etc.) developed core principles and guiding practices for a fully integrated childwelfare system.21 In their guidance to child welfare professionals throughout the state, they identify the need for the child welfare system to be grief-

14 Personal communication with youth in foster care, research participant

15 Lee, R. E, & Whiting, J. B. (2007). Foster children’s expressions of ambiguous loss. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35, 417–428.

16 Schuurman, D. L. & Mitchell, M. B. (2022). Being grief-informed: From understanding to action. Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. https:// www.dougy.org/ assets/uploads/ Being-Grief-Informedfrom-Understanding-toAction.pdf

17 Schuurman, D. L. & Mitchell, M. B. (2020). Becoming griefinformed: A call to action. Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. https://www. dougy.org/assets/ uploads/BecomingGrief-Informed_A-Callto-Action.pdf

18 Dougy Center (2022). The Bill of Rights for Youth in Foster Care Who are Grieving. Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. https://www.dougy. org/resource-articles/ the-bill-of-rights-foryouth-in-foster-carewho-are-grieving

19 Dougy Center (2023). Tips for Supporting Youth in Foster Care Who are Grieving (Tip Sheet). Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. https://www.dougy. org/assets/uploads/ Tips-for-SupportingYouth-In-Foster-CareWho-are-Grieving.pdf

“I didn’t open up to nobody. Nobody ain’t earn my respect enough to open up to them.”:

20 Dougy Center (2023). Now What? Tips for Teens Who are Grieving in Foster Care (Tip Sheet). Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families. https://www.dougy. org/assets/uploads/ Tips-for-Teens-inFoster-Care-Who-areGrieving.pdf

21 https://legacy. utcourts.gov/utc/cip/ wp-content/uploads/ sites/51/2022/04/ Utah-Child-WelfareSystem-CorePrinciples-andGuiding-PracticesNovember-2021.pdf

22 https://www. aap.org/en/ news-room/newsreleases/aap/2021/ children-in-fostercare-much-morelikely-to-be-prescribedpsychotropicmedicationscompared-with-nonfoster-children-inmedicaid-program/

23 Keefe, R, et al. Psychotropic medication usage among foster and non-foster youth on Medicaid; Oct. 8-Oct. 11, 2021 (virtual meeting).

24 Hughes, V. (2011). Shades of grief: When does mourning become a mental illness?

Scientific American, https://www. scientificamerican. com/article/shadesof-grief

informed and their commitment to ensuring that youth in foster care receive grief-informed services. Utah has provided an excellent example for other states interested in learning how to incorporate grief-informed best practices into state policy and service delivery.

Youth who are removed from their homes, families, and communities understandably often experience grief, anxiety, anger, and other responses too quickly labeled as “mental disorders.” Multiple studies have shown the disproportionate overprescribing of psychotropic medication for youth in foster care. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “one in every three children in foster care are on psychotropic medications designed to alter their mental status or mood.”22 Furthermore, research has found that children in foster care who are on Medicaid are prescribed psychotropic medications four times more than children on Medicaid who are not in foster care.23

In March 2022, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) included a new mental health diagnosis, “Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD).” The addition of this new pathology creates serious concerns for the well-being of youth in foster care. Aside from the concern that grief is being labeled as a pathological response to a normal human experience and life condition, this new diagnosis opens the door to more drug development and treatment for this “disorder.” Warnings about the development of a pill for grief started well before the DSM-5 added a “condition for further study” in its 2013 edition, then titled “Persistent Bereavement Related Disorder”24 and, in 2020, a clinical trial for a drug to treat “Prolonged Grief Disorder” was underway.

Here is one of my primary concerns: The drug being used to “treat” grief is currently approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). The researchers who conducted the clinical trial conceptualize Prolonged Grief Disorder as a disorder of addiction, with persistent yearning and longing for a deceased loved one as primary symptoms. They hypothesize that the positive

“I was constantly being doped up on different medicines.”: The “Dominant” Intervention (Psychotropic Medication) in Child Welfare

reinforcement provided by memories of the person who has died enables a craving or addiction. As such, they purport that a drug that helps to resolve the addiction is needed. Naltrexone, their theory asserts, may reduce the craving for the person they are grieving and thereby address the severity of the person’s “Prolonged Grief Disorder.”25 In other words, the goal of naltrexone is to disrupt the social bonding between the person who is grieving and the person they are grieving. One of the many potential side effects of naltrexone is the indiscriminate nature of that social bonding disruption; that is, naltrexone does not differentiate between social bonds. In other words, the drug’s effect does not determine which social bonds are disrupted. The effect of the drug could result in not just creating a disruption in the social bond with the person the individual is grieving, it could also disrupt social bonds with living family members, support networks, and/or peers.26 It is not a huge leap to predict future prescribing of naltrexone to “treat” youth in foster care who are experiencing grief due to the separation from family and friends. Youth in foster care, who are already experiencing isolation and vulnerability, may be further disconnected from the very social bonds and protective factors that help them mediate the changes and losses they’re experiencing.

As a thanatologist, youth advocate, and child welfare researcher, I am deeply concerned about the short- and long-term consequences of “treating” grief as a mental disorder and inadequately addressing grief for youth in foster care. Grief is not something to be “treated” or “fixed.” It is a normal and natural response to loss that requires relational connection, not social disruption. As one youth reported, “A lot of the so-called treatments that I was supposed to be receiving there consisted of a lot of suppressing what comes natural. I think that it’s had more of a negative effect than it’s had a positive effect, due to the fact that you know, if you suppress something for so long, it’s not going to just go away. It’s going to wait and it’s gonna come back with a vengeance later when you finally get a chance to express yourself.”27 Medication will not get to the heart of grief; human connection does.

In addition to recognizing and acknowledging that grief is a normal, and not pathological, response to loss, it is critical that relationally based griefinformed interventions be available to youth in foster care to address death and non-death losses. Having an interpersonal relationship, also known as a relational home, for expressions of grief to be received and held is essential to well-being.28,29 As one youth in foster care reported, “Without being able to talk to anybody, I was walking around angry all the time and getting into trouble.”30

Listening and Led by Youth in Foster Care: Grief, Hope, & Transitions (L.Y.G.H.T.) is one example of a relationally based grief-informed intervention. L.Y.G.H.T., an evidence-based and traumainformed peer grief support program for youth in foster care, was created in response to youth reports indicating their need to express their grief with others who would understand and support them. From their expressed need, the L.Y.G.H.T. program was developed as a grief-informed, youth-centered relational intervention.31 Because peer support and personal empowerment are protective factors for youth who are grieving32, 33, an intervention, other than medication, is needed. Through the L.Y.G.H.T. program, hundreds of youth in foster care have benefited from the relational support they offer to one another to cope with their death and nondeath losses. L.Y.G.H.T. program participants have experienced increased social support, hopefulness, and self-worth as well as a reduction in perceived problems.34 The power of a peer grief support program for youth in foster care is that it provides a sense of belonging through a relational home which is youth-centered and youth-led.

While recognizing there are situations when the health and safety of a youth warrants removal, disconnection from family, friends, and other significant relationships is harmful. As a result of being removed from their families, youth are inundated with loss, grief, and ambiguity from these disconnections, which frequently go unacknowledged and unaddressed, leading to long-term negative outcomes. It is critical for child welfare professionals to not only be traumainformed, but also grief-informed. A lack of griefinformed education can lead to inappropriate and harmful pharmaceutical responses to “treat” grief, instead of utilizing grief-informed interventions that promote relational connection and youth wellbeing.

25 Gang, J., Kocsis, J., Avery, J., Maciejewski, P., & Prigerson, H. (2021). Naltrexone treatment for prolonged grief disorder: Study protocol for a randomized, triple-blinded, placebocontrolled trial. Trials. 2021 Feb 1;22(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13063021-05044-8. PMID: 33522931; PMCID: PMC7848251.

26 Thieleman, K., Cacciatore, J., & Thomas, S. (2022). Impairing social connectedness: The dangers of treating grief with naltrexone. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 0(0). https:// doi.org/ 10.1177/ 00221678221093822

27 Personal communication with youth in foster care, research participant

28 Mitchell, M. B. (2016). The neglected transition: Building a relational home for children entering foster care. Oxford University Press.

29 Stolorow, R. D. (2007). Trauma and human existence: Autobiographical, psychoanalytic, and philosophical reflections. Taylor & Francis Group.

30 Personal communication with youth in foster care, research participant

31 Mitchell, M. B. (2017). “No one acknowledged my loss and hurt”: Nondeath loss, grief, and trauma in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35, 1-9. doi: 10.1007/s10560017-0502-8

32 Hooyman, N. R., & Kramer, B. J. (2006). Living through loss: Interventions across the life span. Columbia University Press

33 Schuurman, D. L., & Mitchell, M. B. (2021). The Dougy Center Model: Peer grief support for children, teens, and families. Dougy Center: The National Grief Center for Children & Families.

34 Mitchell, M. B., Schuurman, D. L., Shapiro, C. J., Sattler, S., Sorensen, C., & Martinez, J. (2022). The L.Y.G.H.T. program: An evaluation of a peer grief support intervention for youth in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10560-022-00843-7

“It made me feel like I was not alone, that somebody understands”: The Power of Relational Connection and Perceived Support

“I’ve been in this foster care business 58 years & I’m tired of hearing and seeing that over half the children in foster care look like me.

We have to go to the community & ask them how to solve the problem, not tell them how to do it.”

Bob Ennis Founder of Ennis Center in Flint, MI

The title of this essay draws inspiration from the scholarship of Edward Shils, who wrote about the ties that bind people together into a family, a community, and a whole society.1 When I first came across the phrase “ineffable significance” during my graduate school days in the 1970s, I immediately sensed its meaning. Still, I needed to look-up the definition. My hunch proved correct: “ineffable” adj. “too great to be expressed or described in words.” Always up for a new challenge, I ended up devoting much of my career to attempting just that—describing in words (and numbers) the ineffable significance of kinship for meeting people’s needs for connection, belongingness, and relational health.

As graduate students of my vintage were inclined to do, I began by taking the long evolutionary view. For 90 thousand of the 100 thousand years that behaviorally modern humans have inhabited this planet, feelings of intense in-group solidarity evolved within hunter-gatherer bands of close family and extended (fictive) kin of just a few dozen individuals. There was no wider society to which people pledged their civil allegiance—only three elementary ties that Shils identified as primordial affinity, personal trust, and sacred devotion united people together into shared identities of belongingness and solidarity.

A succession of societal changes, starting with the Agricultural Revolution, lifted-out social resources from their moorings in kinship and place. The process of societal transformation from band to tribe to chiefdom and later nation state accelerated with the Industrial Revolution and freed human resources for reinvestment as financial, social, and cultural capital in cooperative ventures across vast spans of space and time.2 Sociologists and social workers, who observed and responded to the changes, studied and experimented with whether the elementary forces of in-group solidarity could be unbundled and repurposed to serve the broader civic aims of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Sociologists view diversity, equity, and inclusion from a theoretical perspective that may seem tangential to the practical concerns of social workers, but the two viewpoints are compatible. Since its origins, the founders of sociology discerned in human history an evolutionary trend toward the adaptive upgrading of social and economic roles from the ascribed claims of kinship, place, and caste (diversity). The enhanced productivity that ensued opened up new vistas for achieving a fairer distribution of wealth among economic classes (equity). The incorporation of historically subordinated groups into fully enfranchised membership in the societal community appeared close at hand (inclusion). The proposition famously

1 Shils, E. (1975). Center and periphery: Essays in macrosociology. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

2 Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford, Calif. : Stanford University Press.

invoked by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. anticipated a hopeful path of progress: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Social workers were quick to join the march, and many sought to accelerate the pace. But after two World Wars and the steady erosion of the financial, social, and cultural capital of the families and communities left behind by the global spread of monopoly capital, the optimism that initially greeted the promise of modernity began to fade. The greater diversity, which resulted from the abolition of traditional hierarchies that limited the disposability of human resources by gender, race, religion, and sexual identity, delivered many more invitations to the dispossessed to join the “dance,” so to speak. But once admitted, many found much less of the dance floor available to them to maneuver and the music played not entirely to their tastes. Similarly, absolute levels of poverty plummeted worldwide, but income inequality reached unprecedented heights, which caused many to doubt whether economic justice was ever truly part of the grand scheme. Lastly, inclusion felt less like acceptance and more like assimilation on cultural terms dictated by the dominant groups in society.

Sociologists and social workers have struggled to understand the root causes of what many perceive as modern society’s detour off the main path of progress and on to side trails that curve back towards supremacy, oppression, and exclusion. There is not space in this essay to examine the different twists in the journey. Instead, I begin with my own personal story about the ineffable significance of kinship and fictive kin relations that can feel approximately as strong.

In 2008, my wife and I visited the small Italian village from which my maternal grandfather emigrated to the United States in the 1910s. He was followed several years later by my grandmother and their two young daughters (my aunts). As a child, the village was known to me as the faraway place of Buonanotte, which means “Good Night” in Italian. We approached the small town of 198 inhabitants from the mountains above, parked our car, and walked the rest of the way to the small town square. Holding a copy of the family tree that my wife had assembled from letters and calls to relatives, we entered a small grocery store. I approached a woman at the counter. In my best broken Italian, I inquired whether she recognized any of the names on my list. She looked up, and replied unexpectedly with a Brooklyn accent, “I think we may be related.” She made a quick phone call; ten minutes later three women came strolling down the hill. Their faces beamed with anticipation. The eldest grabbed my cheeks and turned to her sisters, “He looks just like our father.” I too felt the connection and thought to myself, “So this is the ineffable significance that Shils had been talking about.”

The sisters invited us for lunch. According to the genealogical tree, they were my first cousins, once removed. I was able to fill in details missing from my copy of the family tree. The sisters were the daughters of my grandfather’s younger brother. Tradition dictated that the youngest son should stay behind to look after the parents while my grandfather and his older brother set off for America to find their fortune in the restaurant business. The brothers dutifully sent home money to the family. In spite of my unfamiliarity with this branch of

“He looks just like our father.”

Primordial Kinship

the family tree, I nonetheless felt an unmistakable tug of primordial affinity when my cousin cradled my cheeks in her hands. They insisted we visit the rest of the family on the hill and then proceeded to shower us with gifts as we bid them arrivederci

Behavioral scientists have quibbled over whether the feelings we associate with primordial kinship actually originate from some altruism-causing genes. Perhaps the feelings reflect simply the congenial sentiments that accompany the reciprocal exchange of goods and favors, which any recurring transactions will engender irrespective of relatedness. My experience in Buonanotte provided a crucial single-case test of the competing hypotheses. We had no interaction prior to my visit and no expectation that we would ever meet again. Yet, all three cousins exhibited a deep sense of connection that I also felt, which triggered their display of hospitality, generosity, and gratitude for our visit to the town of our ancestors.

Accepting the possibility that primordial affinity persists as a deeply embedded part of our genetic code in no way denies the reality of “fictive” kin relationships. They arise independently of primordial ties and can instill a similar sense of intense mutual attachment that blood relations often do. I have had several such experiences. One fictive kin relationship is my long-term association with Robert Johnson, who along with his two sisters, aunt, and mother became one of the first beneficiaries of the new subsidized guardianship program that I helped design for the state of Illinois in the late 1990s.

In November 2008 following my visit to Italy, I entered a room in which a reception was being held in celebration of the President’s signing into law the Fostering Connections to Success Act. From across the room, I spotted a familiar-looking face. It turned out to be Robert’s mother, who was attending as a special guest of the sponsors along with Robert. As I approached her, I experienced a deep sense of connection similar to what I had felt in Italy. The difference was that whereas my Italian relatives and I bonded over our common decent, my bond with Robert and his mother derived from our shared commitment to a legal permanency option that enabled a family to remain a family without terminating parental rights.

The Fostering Connections Act established the Guardianship Assistance Program (GAP), which authorized payments to states to assist children who leave foster care to the permanent legal guardianship of relatives and fictive kin. It was modelled after the IV-E waiver demonstration that I had designed for Illinois and later replicated in Tennessee and Wisconsin.3 Together, we rejoiced over the creation of a federal entitlement that extended financial assistance to relative and fictive kin caregivers who assumed permanent legal guardianship of children who otherwise would have languished in long-term foster care.

I initially was drawn to the study of kinship foster care during a summer internship in 1975 at the Illinois Bureau of the Budget. A memorandum’s subject line caught my eye: Youakim. It referred to a class-action lawsuit that was making its way upward through layers of judicial appeal. It culminated in the 1979 Supreme Court ruling, Miller v. Youakim. Plaintiffs had challenged the legality of Illinois law, which barred blood relatives from becoming licensed foster parents. Licensing would have entitled relatives to receive the higher foster home boarding subsidy that strangers received after satisfying licensing requirements. Defendants argued that federal law had intended for relative caregivers to be assisted under the less generous Aid to Families with Dependent Children program available to birth parents. The Youakim decision ruled against the defendants. The Supreme Court found no intention on Congress’s part to deny federal foster care benefits to blood relatives for reasons of kinship alone. The ruling paved the way for the federal funding of a hybrid program— kinship foster care.

4 Litwak, E. & Szelenyi, I. (1969). Primary group structures and their functions: Kin, neighbors, and friends. American Sociological Review, 23(1), 465481.

5 Pew Research Center. (March 2022). Financial issues top the list of reasons U.S. adults live in multigenerational homes. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project.

6 Shils, supra note 1, at 122.

7 Pew Research Center, supra note 5, at 3.

8 Titmus, R.M. (1971). The gift relationship: From human blood to social policy. New York: Vintage Books.

After finishing my internship, I went on to complete a two-year stint as a state budget examiner. I then returned to complete my graduate studies. My research interests now focused on child welfare and kinship care, partly for personal reasons. My father had lost his mother to the 1926 pandemic when he was 11 years old. His father was already struggling after being “black-balled” from local manufacturing jobs because of his role as a spokesperson for the New England Workers Association. Because of financial hardships, my grandfather placed his son informally with relatives. At age 15, my dad

Litwak noted that until the late 1940s, many sociologists had embraced the point of view that there was little need to study the extended family because it along with other primary groups were doomed.4 Taking slight liberties and substituting terms used in this essay, Litwak identified the following two theoretical foundations of conventional thinking at the time: First, bureaucratic formality and civil attachment were more effective than informal exchange and primordial attachment in achieving the valued outcomes of a modern society. Second, the continued adaptive upgrading of economic productive capacity assumed enabling conditions that were antithetical to primordial group solidarity, which inhibited differential geographical and occupational mobility.

took matters into his own hands. He secured himself a permanent place with his uncle and aunt on his mother’s side. By today’s standards, my paternal grandfather would have been indicated for abandonment and neglect. Fortunately, my father found lasting permanence with members of his extended family. The major difference from nowadays is that there was no court involvement, no termination of parental rights, and no expectation that my great-aunt and uncle needed to adopt formally in order for this home to remain “truly permanent.”

Knowledge of my father’s travails and my own personal experience growing up only doors away from my paternal great-aunts gave me a different outlook on the modern extended family than what much of the sociological literature had been predicting. The prevailing narrative about the extended family being an antiquated institution in decline took a turn in the 1970s. New empirical evidence became available that challenged conventional wisdom. One of the pioneers in this reorientation was the sociologist, Eugene Litwak.

Empirical evidence gathered over the past decades challenges the validity of the thesis that the extended family system is in decline. In spite of dire forecasts, extended families have retained much of their symbolic coherence. Moreover, the share of multigenerational homes in the U.S. has more than doubled, from 7% in 1971 to 18% in 2021.5 Building on this evidence base, my research efforts moved in two complementary directions. First, I explored the symbolic aspects of kinship care, which Shils characterized as attachments that family members share collectively as possessors of certain “significant relational” qualities.6 Second, I sought to identify the socio-structural correlates of the increasing prevalence of multigenerational households. These are households that contain two or more adult generations or a “skipped generation,” which consists of grandparents and their grandchildren younger than age 25.7 My research focused on this latter group of multigenerational households.

My scholarly endeavors to isolate empirically the relational qualities that make kinship care distinctive began with an investigation of its similarities and dissimilarities with other forms of altruism that Richard Titmus grouped under the heading of “gift relationships.”8 Even though he focused on voluntary blood donations, he recognized that foster care was another area of social policy in which gift transactions took place. However, he did not regard kinship foster care as belonging to this same category. Quoting from

“... my bond with Robert and his mother derived from our shared commitment to a legal permanency option...”

Wilensky and Liebeaux, Titmus noted: “Modern social welfare has really to be thought of as help given to the stranger not to the person who by reason of personal bond commands it without asking.”9

I sympathize with Titmus’s inclination to separate kinship from stranger foster care. The distinction better aligned with the prevailing theory at the time that civil attachments were superior in unifying modern societies than the particularistic bonds of primary groups. By the time Kristen Slack and I published our paper, “The Gift of Kinship Foster Care,”10 the narrative that civil allegiances would entirely displace primordial attachments had lost much of its theoretical credibility. As I later wrote:

It was in between the two publications cited above that I reacquainted myself with the work of Victor Pike and his colleagues on the Freeing Children for Permanent Placement Demonstration in Oregon.12 Its conceptual framework aligned neatly with the two-way flow of influence between older primordial and newer bureaucratic structures, which I thought needed reinforcement in order to conserve the bonding social capital essential to relational health and provide the bridging social capital facilitative of social and occupational mobility. The four relational qualities that Pike and his associates identified were: intent, continuity, belongingness, and respect.13

As explained in my 2005 law review article, “The Quality of Permanence,”14 the Oregon demonstration emphasized that a permanent home is not one that is certain to last forever, but one that is intended to last indefinitely. Continuity refers to the persistence of a relationship over time and with differential geographical mobility. The sense of belonging to a permanent family is rooted in cultural norms and has definitive legal status. Finally, membership in a permanent family conveys dignity and respect for both the child and the permanent family. One conspicuous deficiency of the Oregon model was its disregard for the dignity of birth parents in cases of involuntary termination of parental rights (TPR). The demonstration promoted TPR and adoption as the most appropriate options for securing definitive legal status for the successor parents when reunification efforts stopped. Even though the permanency framework that Congress subsequently codified in the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980 recognized legal guardianship as a permanency goal, the unavailability of guardianship assistance payments similar to the assistance payments available to adoptive parents made the guardianship option, which did not require TPR, unaffordable for most kinship foster parents.15 Congress rectified the inequity in 2008 when it added GAP to the IV-E entitlement.16 It was at the reception celebrating the

9 Wileensky, H. & Lebeaux, C. (1958). Industrial society and social welfare. New York: Russell Sage, p. 141.

10 Testa, M. & Shook, K.L. (2002). The gift of kinship foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 24(1/2), 79-108.

11 Testa, M.F. & Poertner, J. (2010). Fostering accountability: Using evidence to guide and improve child welfare policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 47-48.

12 Emlen, A., Lehti, J., Downs, G., McKay, A., & Downs, S. (1978). Overcoming barriers to planning for children in foster care (DHEW No. (OHDS) 78-30138).

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Administration for Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau, National Center for Child Advocacy.

13 Id, at 10-11.

14 Testa, M. (2005). The quality of permanence—lasting or binding? Virginia Journal of Social Policy and Law, 12(3), 499534.

15 P. L. 96-272, § 475(1)(E).

16 P. L. 110-351, § 471(a)(28).

No longer can child welfare policymakers and practitioners simply take it for granted that the unidirectional displacement of social welfare functions by centralized bureaucratic institutions is structurally inevitable, financially sustainable, or even socially desirable…. The emerging pattern in public child welfare is one in which modern bureaucratic institutions must now learn to coexist with older primordial structures by creating reciprocal avenues of influence so that the macrofunctions of ensuring child safety, family permanence and adolescent well-being can become better coordinated with the microprocesses of parental authority, kin altruism, and community solidarity that make possible the accomplishment of these broader collective aims.11

17 Perry, B., Pollard, R., Toi, B., Baker, W. & Viglante, D. (1995). Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation, and “use-dependent” development of the brain. Infant Mental Health, 16(4), 271291.

18 Whether a fifth quality of a legally binding commitment needs to be added is a topic I address elsewhere. See Testa, M. (2022) Disrupting the foster care to termination of parental rights pipeline: Making a case for kinship guardianship as the next best alternative for children who can’t be reunified with their parents. Family Integrity & Justice Quarterly, 1(1), 74-82.

19 The Pew Research Center, supra note 5, at 8.

20 For a fuller discussion of the benefits of and reasons for the underutilization of subsidized guardianship, see Testa, M. (2022). Disrupting the foster care to termination of parental rights pipeline: Making a case for kinship guardianship as the next best alternative for children who can’t be reunified with their parents. Family Integrity & Justice Quarterly, 1(1), 74-82.

signing of the law that Robert, his mother, and I rejoiced over a new opportunity now available to thousands of families to receive the same type of assistance afforded Robert, his sisters, mother, and aunt to remain together as a family without requiring the legal severance of their existing family ties.

Brain science informs us that the availability of a responsive caregiver to provide support and nurturance to a traumatized child, particularly a child traumatized by separation from primary caregivers, can diminish dramatically the alarm response or the dissociative response in the young child.17 Kinship care provides a reservoir of social capital that can be drawn upon immediately to meet a child’s need for belongingness, permanence, and love. Placement with strangers may eventually serve the same function, but it typically takes months, even years, for bridging social capital to congeal into the bonding social capital that is essential for relational health. Social capital is immediately accessible in most existing relationships in which the child is already familiar with the kinship caregiver, and is readily convertible into the permanency qualities of intent, belongingness, continuity, and respect without terminating parental rights.18