FAMILY JUSTICE JOURNAL

OPPORTUNITIES TO DO GOOD

CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

008 The Opportunity to Do Good

OPPORTUNITIES TO DO GOOD

CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

008 The Opportunity to Do Good

Jerry Milner & David Kelly Directors of the Family Justice Group Introduction

040 Power

April Lee

Co-Founder of Philly Voice for Change

My Perspective

060 It’s Time to Rethink Mandatory Reporting as the Key to Preventing Child Abuse

Valerie Frost

Strategic Initiatives Associate at Kentucky Youth Advocates

062 Hero

Shaumbay Fuller

Peer Recovery Specialist Intern at George Mason University & a Valued Member of the Connections Family Resource Center team A Better Way

064 Reflections

Where Does Compassion Fit In?

Judge S. Trent Favre

Hancock County Court Judge

012 Features A Longitudinal Analysis of a Rural Family Resource Center and the Cost Benefits to the County-Based Welfare System

Sara Bayless, PhD

Vice President at OMNI Institute & Managing Director for the Center for Social Investment

Melissa Richmond, PhD

Senior Manager for Research at the Healthcare Anchor Network

Peter J. Pecora, MSW, PhD

Managing Director of Research Services for Casey Family Programs in Seattle & Professor, School of Social Work, University of Washington

Alana Anderson, PhD

Senior Research Manager at OMNI Institute

022 Hope in the Heartland

Merideth Rose

President & CEO of Cornerstones of Care

Latosha Fowlkes, LCSW

President & CEO at St. Vincent Home for Children

028 Building Supportive Third Places

E. Susana Mariscal, PhD, MSW

Full Professor at Indiana University School of Social Work

Bryan Victor, PhD, MSW

Associate Professor in the School of Social Work at Wayne State University & Associate Editor for the Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research

034 Reclaiming Futures

Alexandria Cinney, JD

Staff Attorney at American Bar Association Center on Children & the Law

Toia Potts

Activist & Organizer for Emancipate NC

Features, continued

042 Realizing the Promise of CBCAP

Patricia A. Cole

Senior Policy Officer within the ZERO TO THREE Policy Center

Rebecca M. Robuck

Partner at ChildFocus & Executive Director of the National Coalition on Child and Family Well-Being

048 Protecting Community-Driven Family Justice

Rashida Abuwala, MSc

Founder & Principal of New Tomorrow

054 These Mothers Are Our Neighbors

Melody Webb

Founder & Executive Director of Mothers Outreach Network

Cathy Krebs

Committee Director of the American Bar Association Litigation Section’s Children’s Rights Litigation Committee & Secretary of the Board of Directors for Mother’s Outreach Network

Linda Brown

Founding member of the Mother Up Community Advisory Board & a Moms Empower Advocacy Fellow

Ditesha McEachin

Advocacy Fellow for the Mother’s Outreach Network

Akua Danqua

Founding member of Mother’s Outreach Network Mother Up Pilot Program Community Advisory Board

Yesmine Holmes

Advocacy Fellow for the Mother’s Outreach Network

Maria Jackson

Advocacy Fellow for the Mothers Outreach Network

Morgan Hicks

Member of the Mother’s Outreach Network Moms Empower Speaker’s Bureau

Advisory Board Members

Christopher Baker-Scott Executive Director & Founder SUN Scholars, Inc.

Angelique Day, PhD, MSW University of Washington Seattle Associate Professor Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute Director of Federal Policy for Partners for Our Children

April Lee Co-Founder of Philly Voice for Change

Dr. Melissa T. Merrick President and CEO Prevent Child Abuse America

Vivek Sankaran Clinical Professor of Law, University of Michigan, Michigan Law

Shrounda Selivanoff Social Services Manager Washington State Office of Public Defense Parents Representation Program

Victor E. Sims, MBA, CDP Senior Associate Family Well-Being Strategy Group The Annie E. Casey Foundation

Paul Vincent, MSW Former Alabama Child Welfare Director Consultant and Court Monitor

Justin Abbasi

Co-Founder, Harbor Scholars: A Dwight Hall Program at Yale

Laura W. Boyd, PhD Owner and CEO, Policy & Performance Consultants, Inc.

Angela Olivia Burton, Esq. Co-Convenor, Repeal CAPTA Workgroup

Melissa D. Carter, JD Clinical Professor of Law, Emory Law

Kimberly A. Cluff, JD MPA Candidate 2022, Goldman School of Public Policy

Kathleen Creamer, JD

Managing Attorney, Family Advocacy Unit Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Angelique Day, PhD, MSW

Associate Professor, Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Center Director of Federal Policy for Partners for Our Children School of Social Work, University of Washington Seattle Adjunct Faculty, Evans School of Public Policy and Governance

Yven Destin, PhD

Educator and Independent Researcher of Race and Ethnic Relations

Paul Dilorenzo, ACSW, MLSP National Child Welfare Consultant

J. Bart Klika, MSW, PhD Chief Research Officer, Prevent Child Abuse America

Heidi Mcintosh

Chief Operating Officer, National Association of Social Workers

Kimberly M. Offutt, ThD

National Director of Family Support and Engagement Bethany Christian Services

Jessica Pryce, PhD, MSW Research Professor College of Social Work Florida State University

Mark Testa, PhD Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Wendel, MSW, LSW Co-Founder, Pale Blue International Consultant, Family Well-Being and Mental Health Systems

Shereen White, JD Director of Advocacy & Policy, Children’s Rights

Cheri Williams, MS Founder and Chief Co-Creator at CO-3

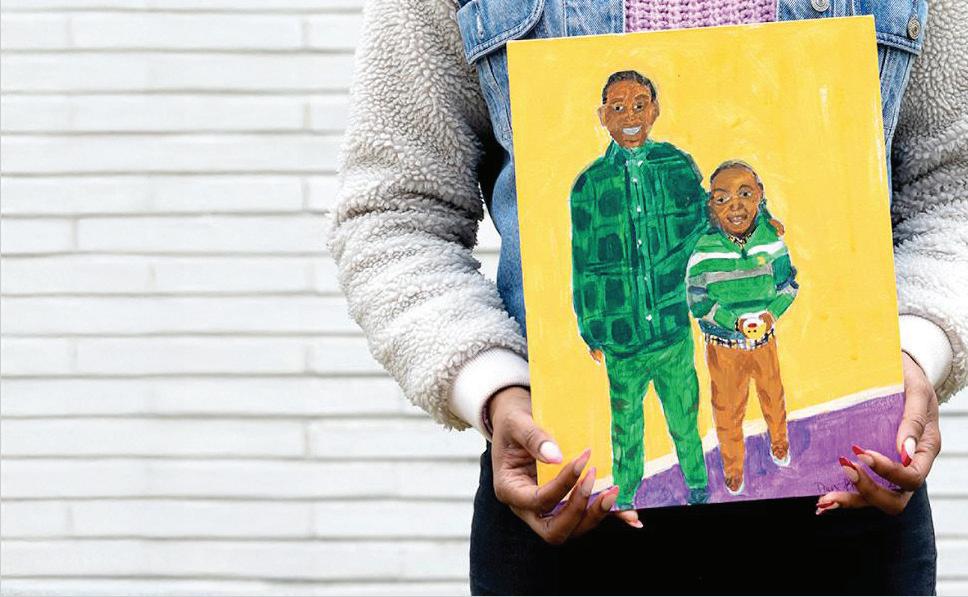

“Mansa Adarian Grace & Kimoni Isaiah Devonte Grace”

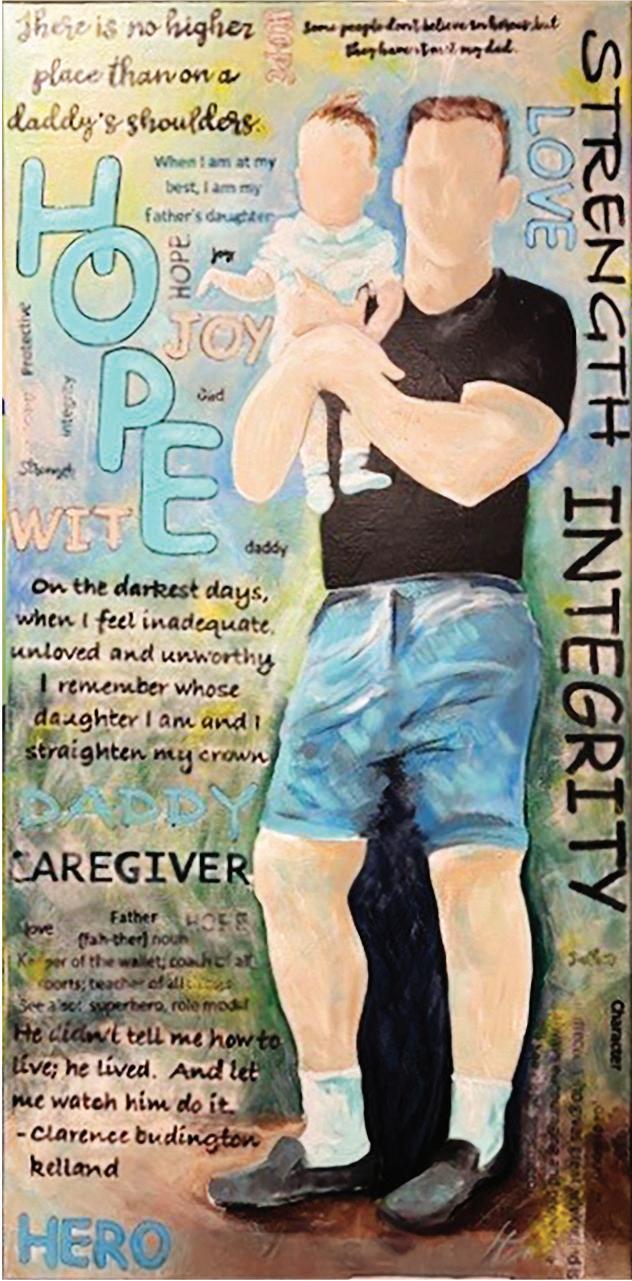

Dawn Blagrove

Dawn Blagrove is the Executive Director and an Attorney at Emancipate NC in North Carolina. She has been a vocal leader in addressing issues such as police brutality, racial discrimination, and criminal justice abolition and has a deep commitment to the intersection of law and social justice. In 2021, she found a new passion that turned out to be a healing journey for her—painting. Dawn’s art aims to reach anyone who needs a touch of hope or a reminder that there’s beauty to be found in this world.

The month of June is National Family Reunification Month in honor of families who have been separated through the child welfare system and achieved the powerful milestone of reunification.

All children deserve the safety, stability and love of being with their families, who also deserve the support needed to care for their children. The Family Justice Group is dedicated to supporting efforts to preserve families.

There are nearly 400,000 children in foster care in the United States, most of whom can be reunited with their families with needed support.

During National Reunification Month, we acknowledge the journey of healing, growth and resilience represented by parents who work hard to overcome adversity and reunify with their children.

Therefore, the Family Justice Group re-commits its purpose, mission and work to lifting up families, preventing and diminishing the trauma of separation and supporting efforts to build community supports for connection, compassion and hope.

We invite everyone who believes in families to join us in this celebration and renewal of commitment.

David Kelly & Jerry Milner Co-Founders & Co-Directors Family Justice Group

Editor - in - Chief

Jerry Milner

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Editor - in - Chief

David Kelly

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Design Director

Ann T. Dinh

Design Consultant

Jerry Milner & David Kelly

We have been in many conversations lately about how people are feeling and what they fear. Clear patterns have emerged: fear of cuts; dismay over certain actions, and a growing belief that we cannot move forward until we have all the answers.

The purpose of this issue of the journal is to deliver a simple message and share examples that give us hope.

It is always possible to do good.

We can do good with or without policy changes, with or without funding changes, with or without all the answers, and even with answers we may not like.

No matter where anyone sits politically or professionally- we are in a moment of great uncertainty and change. The size and role of the federal government is rapidly changing and programs and funding streams that have provided critical support to families may be in jeopardy.

Despite all of this, and maybe even because of it, we have cause to pull together across sectors and political parties to create a situation where this is no longer the case in the future. We can do so by committing to a common vision of supporting families in the communities where they live and holding fast to our focus.

Talk of transformation in child welfare has rung hollow. The term is often used to describe tweaks to an ineffective system rooted in child removal rather than actual change into something else. While the discomfort of the current moment can seem staggering, it can be the jolt needed to let go of old ways that do not work to create space for better ways.

We can reshape our approaches by acknowledging three simple truths.

• Nothing is more protective than family when a family has what it needs;

• Nothing supports families more than community

when the community is strong and empowered to do it, and

• The best way to keep children safe is to have strong families and strong communities.

We can do everything within our reach as individuals, organizations, and collectives to make sure poverty is not conflated with neglect, prioritize connection and belonging in all aspects of our work, and create positive child and family experiences no matter what is going on around us.

This is the stuff of change, not off-the-shelf models or tech solutions; action that lets people know they are seen as fellow travelers worthy of kindness, compassion, investment, and love.

We can look around us and marshal all available resources to trusted sources of community-based support. We can encourage and sustain public-private partnerships to support communities in developing resources and opportunities that will enhance parental protective capacities and community protective factors.

No matter what is going on in our Nation’s capital or state capitals, change will always be felt the most locally. There are incredible examples of individuals, organizations and networks that are leading the way. They did not wait for instructions or ask for permission to do good, they simply saw the needs and acted.

As a field we have long used adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as our focus of attention, reflecting the reactive nature of child welfare. When something bad happens, we react. But adversity will always be present, particularly for economically fragile families and historically disadvantaged populations. Often, our own interventions in child welfare lead to or exacerbate the ACEs in the name of child protection.

We are learning, however, that proactively creating positive childhood experiences (PCEs) can buffer the effects of ACEs and may prevent others from taking root. Some of the more hopeful community-based family support programs and approaches that we have seen are doing just that.

For example, we’ve seen the difference one judge can make in a rural county in Mississippi; by seeking to understand why so many reports were being made to the hotline and pulling the community together to address the underlying causes for reports to a hotline and to create a culture of care rather than judgment for parents experiencing hard times.

It can take the form of a nonprofit organization located in Flint and Saginaw, Michigan that is focused on being a place of connection offering community dinners,

opportunities for families to do positive things together, fun activities for children that their families could not otherwise afford, learning opportunities, and assistance with concrete supports in time of need.

We have seen the continued impact of organized networks offering community responses stewarded by a foundation dedicated to families and keeping children safe in Nebraska that can serve, and is serving, as a national example.

And it can look like a membership organization of traditional child welfare service providers that have decided that old ways lead to the same poor outcomes in Missouri. They are working together to support communities in empowering families and reducing the need for children to ever enter foster care, based on communities’ and families’ priorities.

Evidence of the power of community support can be heard in the story of a grandmother raising her granddaughter after successfully entering recovery. She is now helping other caregivers as a direct result of the trusted support of a family resource center.

Parents whose lives have been turned upside down by child welfare policies and removal approaches speak to the devastating costs of not investing in community support. Many have lost employment due to an unwarranted investigation, instead of family support, or being listed on a registry. Too many have lost their children forever, only to have them spend their growing up years in foster care.

The results of the examples cited above (and many others) include families who live in impoverished and isolated environments who now feel connected to others in the community. They have a trusted place to go to access resources and opportunities. Their children are benefiting from positive and enriching experiences. Community and parental protective capacities and factors are growing. All of this is leading to stronger, more supportive and healthier families and communities.

Each of these examples teaches the same critical lesson. We cannot come into a community with a program or service, or an agenda in mind and try to sell it or seek “buy-in” for it. We must start by asking the community what they want for their families and ask families what they want for themselves. All these examples have also occurred without the federal or state government leading the way. They have largely occurred through public-private partnerships centered on common goals and values.

Still, there remains a huge need to influence federal policies around child welfare so that we can bring this

amazing work to scale and have it be the norm, not the exception. Chief among them, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) which helps make sure children and their families do not go hungry, Medicaid which keeps parents, children and caregivers healthy, HeadStart, which positions students for educational success, and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) whose flexibility helps communities stay safe and meet familial needs.

Doing good at the policy level can look like educating those with power and influence over federal programs and funding and ensuring they know the stories of those families most directly impacted by policies and programs and the differences they make in their lives and futures. This includes education on threats and harms that policy and funding decisions may cause families.

There is also an opportunity to realign harmful and ineffective policies, such as the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) of 1974. CAPTA has led to hotlines being a catch-all for non-emergency situations, at times leaving children who are actually in danger at risk.

Other policies in need of realignment include:

• Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, which funnels billions of dollars to pay for foster care instead of preventing the need for foster care by meeting familial needs,

• The Adoption Assistance and Safe Families Act (ASFA) of 1997, which forever fractures families with arbitrary termination of parental rights requirements and shallow reasonable efforts provisions, and

• The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) of 2018, which offers “prevention services” only after a child is on the doorstep of foster care and ignores true primary prevention and family support.

Doing good in addressing these policies can look like advocating for shifting funding to primary prevention so that foster care and adoption are needed less, and elevating the harm of family separation, termination of parental rights, and too-little-too-late prevention policies. Doing good can demonstrate that often, families simply need the resources to raise their children and that these supports are cheaper and make more sense than more intrusive federally-funded interventions.

Doing good can include sharing the successes of efforts across the country to mobilize communities in support

of families, creating new examples of what we can do to support families and children, and breaking free of our traditional ways of work that are not working for families.

We do not need to wait for any of these policy changes to do good now, and our actions can continue to build support for the changes we need.

We can choose not to be distracted.

We can choose to focus together on our common goals and align our actions and resources to move them forward.

And, when we do, we will create something fundamentally good for all.

SARA BAYLESS, PhD

Vice President at OMNI Institute

Managing Director for the Center for Social Investment

Sara Bayless, Ph.D., is a Vice President at OMNI Institute and Managing Director of the Center for Social Investment. In these roles, she leads rigorous research and evaluations of programs that support children and families and promote economic security for all and advances the evidence for innovative social investment strategies.

MELISSA RICHMOND, PhD

Senior Manager for Research at the Healthcare Anchor Network

Melissa Richmond, Ph.D., is a senior manager of research at the Healthcare Anchor Network, where she supports health systems to leverage their hiring, purchasing, investing, and other key assets to build inclusive local economies.

PETER J. PECORA, MSW, PhD

Managing Director of Research Services for Casey Family Programs in Seattle Professor, School of Social Work, University of Washington

Peter J. Pecora, M.S.W., Ph.D. has a joint appointment as the Managing Director of Research Services for Casey Family Programs, and Professor, School of Social Work, University of Washington – where he teaches courses in public policy, child welfare program design, and human services management.

ALANA ANDERSON, PhD

Senior Research Manager at OMNI Institute

Alana Anderson, Ph.D., is a Senior Research Manager at OMNI Institute where she leads and oversees research and evaluation of public health and child and family-focused programs.

Family Resource Centers (FRCs) are welcoming hubs of support, services, and social connection that provide opportunities for families. FRCs use a strengths-based, family-centered, multigenerational approach that reflects local contexts and needs.i Resources available through FRCs range from basic needs (e.g., food pantries and utility assistance) to parenting classes, peer support, family development, and leadership development, among others. FRCs meet families at their current level of need, help them build on their strengths, and connect them to resources so that they can sustainably meet their needs. In this article, we examine the positive economic impacts that one FRC has achieved through supporting families and strategic partnerships as a model for how others may use this responsive, family-centered model to do good in their community.

FRCs have opportunities to make a difference in their community, county, and state—in both urban and rural areas. In this study we demonstrate the economic good FRCs can have on reducing the incidence of child maltreatment in a small rural community, and the opportunities other communities might have to replicate these results by supporting FRCs. Rural counties generally demonstrate higher rates of substantiated child maltreatment, particularly neglect, compared to urban counterparts.ii This disparity is often linked to limited access to healthcare, mental health services, and high-quality child care, as well as higher turnover rates among child protective services staff in rural areas.iii Additionally, the stigma associated with seeking help in small, close-knit communities may further deter families from accessing essential services.iv As trusted, community-based organizations offering comprehensive family support services, FRCs are uniquely positioned to address these challenges and help prevent child maltreatment and neglect in rural areas. This study contributes to the relatively limited body of research on the effectiveness of FRCs in rural settings.v

FRCs play a key role in preventing child abuse and neglect. Child maltreatment in the United States has far-reaching effects on both individuals and systems.vi For individuals, child maltreatment affects at least one in seven children in the United States annually,vii and in 2015, the estimated cost of child abuse and neglect across the country was $428 billion.viii Child maltreatment can have devastating effects on an individual’s mental and physical health, and can also have far-ranging social and systemic impacts. For example, the cost

to society stemming from child maltreatment is estimated at $268,544 throughout an individual’s life through increased costs to criminal justice, healthcare and education systems, as well as diminished lifetime productivity.ix Therefore, reducing child maltreatment not only benefits children, families, and communities but also has the potential to save the country billions of dollars and allow for investment in other areas of need.x

FRCs often partner with local child welfare jurisdictions to prevent child maltreatment across the child welfare continuum. Partnerships can involve the provision of primary prevention services, targeted services for families who have been screened out of child welfarexi, and services for families during open child welfare cases or postreunification.xii The majority of child maltreatment cases involve neglectxiii that often results from challenges accessing key resources such as food, clothing, shelter, medical care, education, or supervision.xiv FRCs connect families to vital resources in their communities, thereby reducing the unmet need for basic resources. Additionally, studies have found that FRCs increase protective factors for children’s safetyxv and that programs delivered by FRCs can reduce subsequent family involvement in the child welfare system.xvi

Studies estimating the return on investment of FRCs to local child welfare systems advance our understanding of the role that these communitybased services play within the child welfare system. This current study quantifies savings from an investment in one FRC located in a rural county in the Western United States. This FRC is a member of a state-wide FRC network that follows the National Family Support Network (NFSN) Standards of Quality for Family Strengthening and Support. xvii The NFSN advances the family support field by convening member networks and facilitating knowledge-sharing, promoting family support best practices and evaluation, and raising the visibility of how FRC networks support families across the U.S. In 2021, NFSN commissioned this study to leverage existing data to quantify the economic return on investment that FRCs provide to local child welfare systems.

The FRC examined in this study was selected due to the availability of data within the FRC and the child welfare system. The FRC was established in 1992 in a rural county with a population of approximately 25,000 in a western state in the United States. There are no other FRCs in this county. Reflecting

the county population at large, families who receive services from the FRC mostly identify as White (87%).xviii Compared to other families in the county, families served by the FRC experience economic challenges, with 62% of families having no cash savings and 42% of families having incomes below 100% of the federal poverty line, relative to the national average of 8%.xix

We identified 2015 and 2018 as the two comparison years for child welfare outcomes that would best isolate the effects of programmatic shifts and limit the effects of county and state initiatives. The FRC had a partnership with the county child welfare office that began in 2014 as a pilot program and was implemented at scale in 2016. As part of the partnership, when appropriate, the county child welfare system referred families to the FRC for voluntary services. Referrals would typically occur when families were screened out for investigation assignments by child protective services due to the nature of the report (e.g., report does not indicate an imminent safety threat) or that were screened in but had their cases closed without the provision of child welfare services.

To calculate the return on investment of an FRC for the child welfare system, we used a social return on investment (SROI) model. SROI describes the impact of a program or organization in dollar terms relative to the investment required to create that impact.xx

Using the framework provided by the New Economics Foundation,xxi we specified our SROI model as follows:

The following section identifies the data sources and outlines the calculations used to develop the estimates for each aspect of the model.

The outcome in this study is child maltreatment as indicated by substantiated assessments of referrals to child protective services in the FRC’s county in 2018, the selected outcome year. Deadweight is represented by the number of substantiated assessments in 2015, the selected baseline year. Data on the number of substantiated assessments were gathered from a public database that reports on child maltreatment occurrences across the state. xxii To control for changes in county population over time, the number of substantiated cases in each year was divided by the total number of children under the age of 18 in the county in that year as reported by the U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS).xxiii This resulted in rates of substantiated cases of child maltreatment for 2018 (Outcome) and 2015 (Deadweight).

Such that:

• Outcome of Interest is a reduction in substantiated assessments of child maltreatment referrals to child protective services;

• Deadweight is the counterfactual number of substantiated assessments that would have occurred in the absence of the FRC;

• Attribution is the share of those substantiated assessments that is attributable to, or results from, the FRC;

• Monetized Value of the Outcome is the child welfare expenditure per substantiated assessment; and

• FRC Intervention Cost is the cost of operating the FRC.

To calculate the reduction of substantiated assessments in the county from 2015 to 2018, we subtracted the Deadweight rate from the Outcome rate. This difference in rate was then multiplied by the number of children in the FRC’s county in 2018, as reported by the ACS, to estimate the reduction in substantiated assessments between 2015 and 2018, controlling for population changes. There was a 62.84% reduction in substantiated assessments from 2015 to 2018. Adjusting for population changes, this translates to 51 fewer cases in 2018 compared to 2015.

We estimated attribution as the proportion of children at risk for maltreatment in the FRC’s county in 2018 that were reached by the FRC (i.e., FRC penetration rate). We used the assumption that the

higher the proportion of at-risk children reached by the FRC, the greater the share of reductions in child maltreatment that can be attributed to the FRC. Direct data were not available for either the number of children served by FRC, nor the number of children at risk for maltreatment in their County, so we used available data to estimate these values as described below.

The FRC served 722 unique families in 2018 and estimated that there was an average of two children per family. These data were used to estimate the total number of children served by the FRC in 2018. According to the US Census, there were an estimated 2,297 families with children living in the county at that time, with 8% of those families with household incomes below the poverty level (approximately 184 families) and 1439 families with household incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.xxiv This suggests that the FRC reached nearly one-third of families living in the county at that time, potentially reaching all families with household incomes under the poverty threshold.

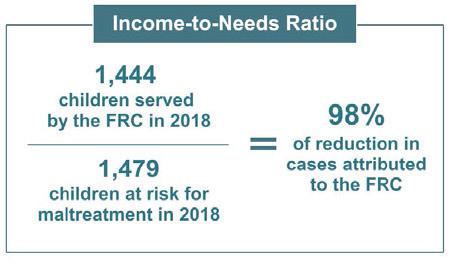

We used two different approaches to estimate the number of children in the county at risk for child maltreatment using known risk factors for experiencing child maltreatment: (1) income-toneeds ratio and (2) child age.xxv The supporting calculations for each approach are detailed below. Income-to-needs (ITN) ratio is the ratio of overall annual income to household or family size and serves as an indicator of socioeconomic status. Although child maltreatment occurs across all levels of socioeconomic status, poverty is one of the strongest predictors of whether a child will experience maltreatment and is associated particularly strongly with rates of neglect.xxvi Although most low-income children will never be involved with the child welfare system, an incomebased measure allows for a compelling single-factor estimate of children at risk for child maltreatment.

xxvii

Income-to-needs ratio. To estimate the proportion of children in the county that may be at risk for maltreatment, we used the FRC’s evaluation and ACS data to extrapolate the ITN ratio of families served by the FRC relative to the overall county child (under 18 years) population. For example, as shown in Table 1, 42% of families served by the FRC have incomes below 100% of the Federal

Poverty Level (FPL), and the ACS estimates there were 758 children with household incomes below 100% of the FPL in the county in 2018. xxviii Therefore, we estimate that 318 children with household incomes below 100% of the FPL are at risk for child maltreatment in the FRC’s county (42% of the 758 children in households with incomes below 100% of FPL equals 318 estimated at-risk children). We combined these calculations across ITN ratio brackets to estimate that the total number of children at risk for maltreatment in the FRC’s county in 2018 is 1,479 (see Table 1).

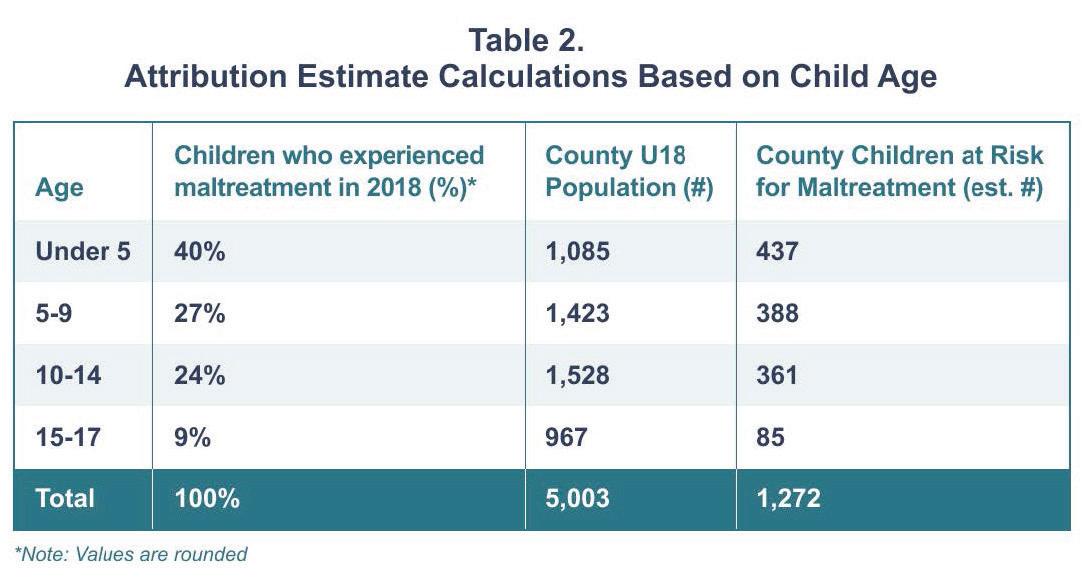

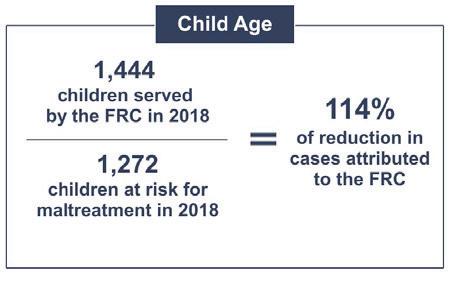

Child Age. Younger children are more likely to experience maltreatment than older children.xxix We used data on the age of children who experienced maltreatment in the state in 2018 provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).xxx We calculated the percent of children who experienced maltreatment at each age, then multiplied that by the number of children at that age grouping in the FRC’s county in 2018 as provided by the ACS. We combined these calculations across all age groups (from 0-17) to estimate the total number of children at risk for child maltreatment within the FRC’s county in 2018 (see Table 2).

Attribution Rate. We used the estimated number of children served by the FRC (1,444) relative to the estimated number of children at risk for maltreatment based on ITN ratio (1,479) and child age (1,272) to generate attribution estimates. Using the ITN ratio approach, the attribution estimate was 98%; using the age approach, the attribution estimate was 114%.

These estimates suggest that the FRC reaches the population of children at risk for maltreatment in the county. Because of the convergence of these approaches on the estimated number of children at risk being reached by the FRC, we used an attribution rate of 100% in the SROI calculations, attributing all 51 fewer substantiated cases in the county in 2018 to the FRC.

The monetized value of the outcome was defined as the cost incurred by the county child welfare system for each substantiated assessment in 2018. We estimated this cost using the steady-state methodology in which the total annual child welfare costs in one year serve as a proxy for the lifetime child welfare costs of maltreatment cases in that year. Child welfare services and their associated costs vary widely (e.g., the cost of an in-home service is lower than out-of-home placement) and the length of time that services last can also vary widely, from single points of contact to years of support. However, there are no longitudinal studies that provide direct estimates of the average cost to the child welfare system from a substantiated case; therefore, researchers have drawn on the steady state methodology (used in other fields, such as chronic illness) to provide a best estimate. As applied here, this approach assumes that the types and length of services provided by a child welfare agency remains relatively steady year over year, and that the average cost captures the variation in types of and length of services provided to families and their varying circumstances. xxxi

Using this steady-state methodology, the total child welfare expenditures in a given year are divided by the total number of substantiated assessments in that year. To calculate the estimate specific to the FRC’s county, we used the 2018 Actual Expenditures for the Child Welfare program as reported in the county’s adopted budget in 2020 and the number of substantiated assessments in 2018 as reported by the state’s DHS (the same number used to calculate the outcome).xxxii The resulting estimated cost of $49,026 per substantiated assessment is similar to the national average of child welfare expenditures of $47,255.xxxiii

The intervention cost is estimated as the FRC’s total annual expenses in 2018, based on the FRC’s Form 990, accessed via ProPublica.xxxiv The FRC’s total annual expenses for 2018 were $856,194.xxxv

The estimates used to calculate FRC’s return on investment to the county’s child welfare system are provided below. The estimated net value of benefits is $2,500,326; that is, the reduction of 51 substantiated assessments saved the county’s child welfare system $2,500,326 in 2018. Relative to the net value of the investment in the FRC in 2018, there is a return on investment of 292%, or $2.92. In other words, for every $1 invested in the FRC, the county child welfare system saved $2.92.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by substituting the full range of attribution estimates (between 0 and 100%) into the overall SROI calculation. These sensitivity analyses allow us to identify the minimum number of reduced cases of child maltreatment attributed to the FRC that results in a positive return on investment, specifically a return of at least $1.01. Results indicated the lowest possible attribution estimate for a positive return on investment is 35%; that is, if at least 18 of the 51 cases of reduced substantiated assessments are attributed to the FRC, there is a positive return on investment to the child welfare system in the county where the FRC is located.

This study demonstrates an estimated return on investment in a local child welfare system from investment in a Family Resource Center, using quantitative economic assumptions about the benefit of community-based family support services. These findings estimated a measurable benefit to the county child welfare system provided by the FRC serving the county, with a return of $2.92 for every $1 invested.

We examined the return on investment of a long-standing, well-established FRC that began implementing two new programs designed to serve children and families who may be at heightened risk for child welfare involvement. Those two new programs included partnerships 1) utilizing the FRC as a key referral resource for families screened out of child welfare and 2) implementing enhanced family supportive services through additional state funding. The FRC’s nearly thirty-year history in the county and direct partnership with its child welfare system likely contributed to their ability to effectively serve families, and, in turn, generate economic benefits. Further, these findings suggest that even in locations where FRCs already exist, there are opportunities to expand and strengthen the benefits provided to families, communities, and the child welfare system through strategic partnerships and prevention programming designed to reach families most at risk for system involvement.

This study adds to existing research describing the estimated economic return on investment for FRCs. A similar study found cost savings to the child welfare system with an estimated return of $3.65 for every $1 invested in a California FRC.

xxxvi Additionally, in 2014 the Alabama Network of FRCs, provided an estimated return of $4.93 in

immediate and long-term social value to the State of Alabama. The Alabama return on investment estimate was derived from estimates of the overall direct and long-term social value of 224,316 individual services provided by the Alabama Network of FRC members, relative to the total funding used to provide those services.xxxvii The more narrow focus of the current study (examining only returns to the child welfare system, versus the entire state government) and the more localized pre-post analysis provide a more focused understanding of the return on investment that FRCs provide on a community level.

The findings from this study have implications for child welfare and family support services policy and practice. The observed return on investment reinforces the economic and social value of funding community-based FRCs, particularly those with strong ties to the local child welfare system. Policymakers can use this study to support justification for investment in FRCs as a cost-effective and cost-saving preventive strategy that alleviates burden on child welfare agencies. Furthermore, the success of the two new programs examined in this study—partnering with FRCs as a key referral resource for families screened out of child welfare, and providing enhanced family supportive services through additional state funding—highlights the importance of strategic, targeted programming that addresses service gaps for at-risk populations, such as economically disadvantaged families in rural communities. For providers and practitioners, the study underscores the potential of FRCs to act as hubs for early intervention and prevention, especially when supported by state-level funding and integrated into formal child welfare processes. Scaling such partnerships and support structures could lead to broader systemic changes that prioritize prevention and community-based care, ultimately contributing to healthier family systems and reduced demand for costly, intensive, and traumatic child welfare interventions.

FRCs provide responsive services designed to meet the unique needs of the families and communities they serve. They often blend and braid funding and allow families enrolled in services broad access to the many resources and referral networks at its disposal. As a result, it is challenging to disentangle the impact FRCs have on families, or on the child welfare system. Best practice in SROI includes a rigorous outcomes study to estimate the degree to which the program had positive benefits, and ideally, this is done through experimental or quasiexperimental designs. For example, estimates of

return on investments for parenting programs have been based on randomized implementations of programs at the county level,xxxviii and other SROI estimates for FRCs have been based on propensity score matching of service areas.xxxix Indeed, when originally designing this study, we sought to identify a comparison county that would facilitate a quasi-experimental design through a differences-in-differences approach. We identified 11 counties in the state that were not served by an FRC. Of those 11, two were demographically similar (e.g., with respect to race/ethnicity, unemployment, poverty, resident turnover, and the ratio of children to adults). However, two potential comparison counties had significant policy changes or situational differences during the 2015-2018 period that would have introduced a significant confound to our comparisons (e.g., presence of a differential response model; use of a reporting hotline). Therefore, we relied on an estimate of reductions in child maltreatment over time that corresponded with changes in programming delivered by the FRC. With this approach, we also were not able to track child welfare outcomes for families served directly by the FRC, instead relying on county-level data. FRCs, networks, and states should pursue efforts to directly link data systems that would allow tracking of service provision by FRCs and child welfare outcomes over time.

No definitive guidance exists in the estimation of attribution in SROI models.xl The indicators of income-to-needs ratio and child age used to inform the attribution estimate provided imprecise estimates for the proportion of children at risk for child maltreatment in the county that the FRC impacted. The attribution rate may be less than 100%; that is, although the selection of 2015 and 2018 was designed to isolate the effects of the FRC as closely as possible, other systemic changes not accounted for in this analysis (e.g., local economic conditions or school-based programs) could be responsible for some portion of the decrease in child maltreatment. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the return on investment is positive if the attribution rate is greater than 35%, while lower attribution rates return lower estimates of this return.

Our analyses were limited to two years (2015 and 2018) to best isolate the impact of programming at the FRC within larger county and state child welfare initiatives. Future research should seek to include multiple years of data in the analyses to provide a more robust understanding of how child maltreatment changed over time and make the estimates less susceptible to the influence

of unknown system-level factors. Additionally, this study estimated the impact of one FRC in one county in a western US state and may not be generalizable to other communities; thus, this analysis should be considered a case study of the possible return on investment in one community.

Nevertheless, these findings contribute to a growing body of evaluative data on the benefits of FRCs for their communities.xli Specifically, this study demonstrates the economic benefits that an FRC can provide to a local child welfare system by reducing incidences of child maltreatment. The findings here suggest that for this rural county, the FRC provides not only a community-based hub for families but also a meaningful return on investment to the child welfare system, with a return of nearly three dollars for every dollar invested.

This study was developed by Omni Institute, in partnership with the National Family Support Network (NFSN) and Casey Family Programs (CFP). We thank NFSN and CFP for supporting this project with funding and technical advice. We also thank the participating Family Resource Center for their partnership in conducting this study.

i Omni Institute (2013). Key components of Family Resource Centers: A review of the literature. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ ugd/20e556_7d6b57ed42d34674a87ac78d28f01bc8.pdf

ii U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Child Maltreatment 2019. Administration for Children and Families.; Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., & Li, S. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

iii Zellman, G. L., & Bell, R. M. (2012). The role of neighborhood characteristics in child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(6), 447–452.

iv Belanger, K., Price-Mayo, S., & Espinosa, D. (2008). The role of rural and urban contexts in child maltreatment rates. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(9), 1041–1050.

v Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). Definitions of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/statutes/define/

vi Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Preventing child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/ violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html; Safe & Sound (2019). The economics of child abuse: A study of California. https://safeandsound.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/SafeSound-2019-CA- Report.pdf

vii Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Preventing child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/

violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

viii Ibid.

ix Safe & Sound (2019). The economics of child abuse: A study of California. https://safeandsound.org/wp- content/ uploads/2019/08/Safe-Sound-2019-CA-Report.pdf/

x Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S., & Mercy, J. A. (2012). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(2), 156165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006

xi Screened out cases refer to instances where a report made to child welfare does not meet the criteria for child abuse or neglect; often, families are referred to community resources.

xii Russo, A. (2019). Partnering Family Success. Policy and Practice. https://gallery.mailchimp.com/ed250daa64bb471a0a16ac92e/ files/1c3d397d-9f03-493d-86eb- adc37c86f5c9/P_P_ December2019_FamilySuccess_NFSN.pdf

xiii In 2019, 74.9% of child maltreatment victims were neglected, and 61% of all cases of child maltreatment included neglect only (i.e., did not also include physical or sexual abuse). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child Maltreatment 2019. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/ report/child-maltreatment-2019

xiv U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. (2022). Definitions of child abuse and neglect: Summary of state laws. Child Welfare Information Gateway. https:// www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-HE23_1200-PURLLPS124431/pdf/GOVPUB-HE23_1200-PURL-LPS124431.pdf

xv Casey Family Programs (2019). Supportive communities: Do place-based programs, such as Family Resource Centers, reduce risk of child maltreatment and entry into foster care? https://www. casey.org/family-resource-centers/

xvi Social Work Research Center: Colorado State University (2018). Colorado Department of Human Services Colorado Community Response final evaluation report 2014-2018. https:// earlychildhoodframework.org/wp- content/uploads/2018/10/ CCR-Evaluation-Report-FINAL-DRAFT-2014-2018.pdf

xvii National Family Support Network (2021). Standards of quality for family strengthening and support. https://www. nationalfamilysupportnetwork.org/standards-of-quality

xviii Omni Institute (2018). Community Partnership Family Resource Center CFSA 2.0 evaluation report: July 1, 2017- June 30, 2018.

xix Ibid.

xx Olsen, S. & Lingane, A. (2003). Social return on investment: Standard guidelines. UC Berkeley: Center for Responsible Business. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6xp540hs

xxi New Economics Foundation (2008). Measuring value: A guide to social return on investment. https://commdev.org/wp-content/ uploads/pdf/publications/Measuring-Value-A-Guide-to-SocialReturn-on-Investment.pdf

xxii Colorado Department of Human Services, Office of Children, Youth & Families, Division of Child Welfare (2021). Community Performance Center, Child safety. Data pulled in January 2021.

xxiii U.S. Census Bureau (2021). 2010-2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates subject tables: Age and sex. https:// data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Teller%20County,%20 Colorado&tid=ACSST5Y2018.S0101&hidePreview=false

xxiv U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). POVERTY STATUS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS OF FAMILIES. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1702. Retrieved April

23, 2025, from https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2018. S1702?q=Teller+County+Colorado&t=Families+and+Living+ Arrangements:Income+and+Poverty.

xxv Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Preventing child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/ violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

xxvi Although socioeconomic status is a strong predictor of child maltreatment, the relation is complex and not causal; for example, child welfare investigations are disproportionally targeted at families living in poverty, and most families in poverty do not maltreat their children. Berger, L. M., & Waldfogel, J. (2011). Economic determinants and consequences of child maltreatment. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers, No. 111. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5kgf09zj7h9ten.pdf?expires=1626728749&id=id&accname=guest&checksum= C4BD422492208B3462767100ACDBFCEF

xxvii Sedlak, A.J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., and Li, S. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ sites/default/files/documents/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_ pdf_jan2010.pdf

xxviii Data for the County child (under 18) population includes the American Community Survey estimate plus the full margin of error for each group to create the most conservative (i.e., largest) estimates possible.

xxix U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2018

xxx Ibid.

xxxi See for example:

• Birnbaum, H., Leong, S., & Kabra, A. (2003). Lifetime medical costs for women: Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stress urinary incontinence. Womens Health Issues, 13(6), 204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.07.001

• Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S., & Mercy, J. A. (2012). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(2), 156-165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006

xxxii The annual County Adopted Budgets report the actual spending for each department two years prior. The budget is publicly available at www.co.teller.co.us. To ensure funding included in the estimate of the monetized value of the outcome was not also included in the estimate of the intervention cost, we confirmed with the FRC that they did not receive any funding from the child welfare division of the County Department of Human Services in 2018

xxxiii $47,255 is an inflation-adjusted estimate in 2019 dollars calculated by Safe & Sound (2020) based on the original estimate in 2016 dollars calculated by Child Trends (2018). See for example: • Safe & Sound (2020). The economics of child abuse: A study of California and its counties, Technical Appendix. https://economics.safeandsound.org/static_reports/Safe. Sound.-.2020.Economics.Report.-.Technical.Appendix.pdf;

• Child Trends (2018). Child welfare financing SFY 2016: A survey of federal, state, and local expenditures. https:// www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ CWFSReportSFY2016_ChildTrends_December2018.pdf

xxxiv Given that we examined change in substantiated cases from 2015 to 2018 as the outcome, an alternative approach is to calculate the difference in the FRC’s annual expenses in 2015 and 2018 as the estimate of intervention cost. This alternative approach assumes that only new expenditures contribute to the reduction in substantiated cases. We opted not to use this approach given that FRCs take a comprehensive, family-centered approach to services

(e.g., those families referred to the FRC through the Colorado Community Response program could access any of the services available at the FRC, many of which have been available prior to 2015). The implementation of the Colorado Community Response and Family Support Services do not reflect just new services, but also a new model of partnering with the county and making services available to families. In addition, FRCs are funded through a variety of mechanisms, including programming funded by grants that change over time, and they blend and braid funding in ways that make it difficult to isolate costs associated with county-wide outcomes. Therefore, we were concerned that using the difference in expenses could underestimate the total costs of the intervention.

xxxv Per communications with County DHS, the FRC did not receive any funding from the County’s child welfare division in 2018.

xxxvi Douglass, Richmond, Pecora & Ariza. (2025). Returns on Investment of a Family Resource Center to the Child Welfare System: Estimates from a QuasiExperimental Study from the Western United States. The Family Justice Journal.

xxxvii Community Services Analysis Company LLC (2014). Alabama Network of Family Resource Centers: Social return on investment analysis. http://csaco.org/ files/103503730.pdf

xxxviii Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Populationbased prevention of child maltreatment: the U.S. Triple p system population trial. Prevention Science, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3

and Lee, S., Aos, S., Drake, E., Pennucci, A., Miller, M., & Anderson, L. (2012). Return on investment: Evidencebased options to improve statewide outcomes, April 2012 (Document No. 12-04-1201). Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

xxxix Bayless, S., Ariza, A., Richmond, M. & Pecora, P.J. (2025). Returns on investment of a family resource center to the child welfare system: Estimates from a quasi-experimental study from the western United States. Family Justice Journal, Vol. 22, 10-16. Retrieved from https://www.thefamilyjusticegroup.org/

xl Solorzano-Garcia, M., Navio-Marco, J. & RuizGomez, L, M. (2019). Ambiguity in the attribution of social impact: A study of the difficulties of calculating filter efficiencies in the SROI method. Sustainability, 11, 386. doi:10.3390/su11020386

xli Casey Family Programs (2019). Supportive communities: Do place-based programs, such as Family Resource Centers, reduce risk of child maltreatment and entry into foster care? https:// www.casey.org/family-resource- centers/; National Family Support Network (2021). Advancing the family support and strengthening field project. https://www. nationalfamilysupportnetwork.org/resources

MERIDETH ROSE

President & CEO of Cornerstones of Care

LATOSHA FOWLKES, LCSW

President & CEO at St. Vincent Home for Children

In Missouri, a coalition of private sector providers, the Missouri Coalition for Children (MCC), is working to ensure families have the connections and community support they need to thrive and reduce the likelihood that families become ensnared in the child welfare system. In 2023, MCC began implementing an approach called Connected Communities, Thriving Families (CC-TF) that supports communities in developing strategies to make resources, opportunities, and supports available to families in their communities. FJJ has been following MCC’s efforts closely.

Over the past two years we have had the opportunity to have ongoing conversations with two leaders participating in CC-TF; in particular, Merideth Rose, the President and CEO of Cornerstones of Care in Kansas City, and Latosha Fowlkes, President and CEO of the Core Collective at Saint Francis in St. Louis. They are leading historical organizations that focused primarily on residential placement and foster care in bold new directions.

They are courageous leaders who have inspired us, and we hope their examples will encourage and fortify others to move boldly forward for good.

What led you to this work? Have your life experiences shaped the way you see traditional child welfare approaches and the need for change?

Latosha: I’ve always been certain of two things: I would become a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) and I would build a family. The paycheck didn’t matter; what mattered was the calling—to serve my neighbors, protect children, and uplift communities. I believed that I could be part of a generation that could create lasting change.

Through my years of working with thousands of children and families in the St. Louis region and my own life experiences, I came face-to-face with the harsh realities of our national and local child welfare systems. Growing up, I was handed a formula: college, marriage, financial security, and then a family. As a young Black girl from a small town in Illinois, I believed this was the key to success: just follow the path.

But there were unforeseen challenges and pain along the way. It first came with efforts to start our own family, which we attempted to do through the Missouri foster care system.

We received the pictures and profiles of two beautiful Black girls and began preparing our minds and home for the idea that we could have children in our home in as soon as two weeks. We had to find a school, a doctor, childcare, and prepare to decorate their room to their liking. In our heads, we could already see them in our home; we felt them in our hearts. A few hours after the interview, we got the call and heard the words that broke our hearts, “You were not selected.”

What we experienced wasn’t isolated. It mirrored the very challenges within the foster care system that I had been fighting to reform and the impact it has on families. As a social worker, I had witnessed these barriers firsthand, but as a hopeful parent, I now felt them deeply in my own home.

This deepened my empathy for all families involved with the child welfare system and what happens to them---parents waiting with bated breath for the return of their children, or longing for the next time they see each other.

Drawing from my family’s personal experience and the voices of youth, biological, foster, and adoptive families, we at The Core Collective, alongside our community, have made significant strides in preventing the harmful separation of families and investing in communities to help them thrive.

Merideth: Like Latosha, my experience navigating the child welfare system was personal, and has deeply and intimately framed the way in which I champion the preservation of families in this space through the critical prevention work of Cornerstones of Care.

As a successful byproduct of a kindship adoption at just 2 months old, my origin story was plagued with the harms of complex traumas including sexual assault as a minor, abusive and domestically violent relationships, poverty, and homelessness. Raised by a loving and faith-filled single woman, my mother did all she could to ensure I had access to the love and care to enrich my education, my sense of responsibility, and my pride in doing everything with a spirit of service and excellence. As an adolescent, however, I often found my traumas manifested in poor decisions, poverty-mindset, and an inability to understand the potential harms of my traumas.

By some miraculous condition that I can only describe as God’s unmerited grace, I graduated from my small Lutheran high school with a class size of less than 50, and a school population of 200, of which I was the lone black student all four years. I blazed straight ahead as ‘good girls ought’ to Missouri’s largest public state college with no identity, direction, clue or healing. Nine months later I was back home in Kansas City, now a teenage mother of twins. I was a baby with babies, a single mother struggling to find purpose, safety, support and joy. I knew I needed to get back to college but couldn’t afford housing and barely had the basic needs to care for myself, let alone twin babies. I ultimately found myself homeless with newborn babies while in unsafe and unsavory relationships.

Neighbors made a hotline call to Missouri’s Children Division (CD) about my lack of ‘care and concern’ for the safety and well-being of my twins. They were removed from my custody and placed in the temporary guardianship of my mother, nearly an hour away with no offers of support for me. I was given one goal, to get my children back, packaged and presented in a CD caseworker with little hand holding. But there was no guide and no safety-net to catch me when my world collapsed.

As a woman raised in faith, I knew God’s greatest desire was for humans to live and thrive in community. True to the essence of Ubuntu, indeed a caring community of people who looked nothing like me, played a critical part in helping my mother raise what was obviously a very broken child. Although I was isolated from that community of care that would ultimately help me heal and get on the path to restoration and wellness, I was ultimately blessed with new champions from that community that helped to heal and inspire my resilience and restoration.

In July 2022, my journey led me to Cornerstones of Care, an organization personally meaningful as its therapeutic services had been a part of my mother’s caring more than twenty years prior. It was like coming ‘home’ to lead the organization that ultimately was one of the cornerstones of my intensive and tedious journey toward healing, made possible in and through the supportive hands of community.

What are you (Core Collective and Cornerstones of Care) doing differently, and why? What do you believe these changes can make possible with and for families and their communities?

Latosha: Our vision for transformation extends to our 110,000-square-foot building and 22 acres of land, which we are converting into a vibrant hub of healing, housing, and well-being. This comprehensive one-stop center, supported by a coalition of diverse organizations, will offer services that cater to the diverse needs identified by our community, setting a new standard for wellbeing in St. Louis.

In a groundbreaking move, The Core Collective at Saint Vincent launched a cross-systems partnership with the local juvenile courts, a local school district, the local police cooperative, local business owners, and other stakeholders united by a shared commitment, to streamline access to essential resources that significantly enhance the well-being of youth and families. Through the voices and lived experiences of our community, we are investing in prevention.

We are dedicated to easing the burden on youth aging out of foster care by extending support well beyond traditional age limits. A report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that extending foster care services to age 26 significantly improves outcomes in education, employment, and housing stability. By raising the age limit for foster care services and investing in long-term, holistic support, we are committed to addressing the evolving needs of these young adults and their communities.

We cultivate space for transformation regardless of age, race, gender, or preferences, ensuring that the community’s voice is heard in developing our programs and policies that impact them so profoundly. We’ve created an environment where healing, learning, recreation, and community connections flourish. “Trauma-informed care models emphasize community connections in healing, particularly for communities that have experienced systemic inequities” (SAMHSA, 2020). No longer just St. Vincent Home for Children, we are now The Core Collective—a thriving community invested in the transformational power of our youth. In the words of one of our alumni, “With a 170-year history, we were the strongest when we surrounded our youth within

an environment where people of all generations gathered to invest in their well-being.” We leaned into our history.

Since launching our new strategic direction in 2022, The Core Collective has experienced a remarkable 76% increase in service engagement. Even more significantly, 83% of the youth aging out of foster care in our Transitional Living Program have reported meaningful gains in the skills essential for their independence. Our approach is replicable and can be adapted to create lasting impact wherever it is implemented.

Growing up in a tight-knit community that poured into my well-being, I am now driven to create that same environment for the children we serve. My husband and I still cling to the hope that one day, our empty bedrooms will be filled with the joy and laughter of children who no longer face the fear of aging out of foster care or having their families wrongfully disrupted.

If creating trauma-responsive spaces for children to receive the immediate care they need is the must do, then upstream prevention and walking alongside families to mitigate the trauma is the right thing to do.

– Merideth

Merideth: For Cornerstones of Care, our new strategic plan moves toward prevention by providing the best possible care with the least disruption to families, a foundation of our culture for more than 155 years. While we continue our traditional work in foster care and adoption, the plan pushes us to increase our focus to expand intervention programs like Build Trybe, our outpatient clinical services, and our Intensive InHome and Intensive Family Reunification Services. Build Trybe provides marketable job skills to youth as they transition out of foster care to reduce chronic unemployment, homelessness, and food insecurity that too many youths face after aging out of foster care.

Our Kansas team reduced the number of youth in foster care by 47% since 2019 thanks to our foster care work in Wyandotte, Leavenworth, and Atchison counties. Our goal is to engage with families in ways that don’t begin with a hotline call and safety concerns.

Each year, Cornerstones of Care serves more than 15,000 children and families spanning 115 counties across Missouri and Kansas, with the goal of keeping children safe, healthy and whole within their family units. Our short-term crisis intervention program meets individuals in the places where life occurs, in homes and communities, and supports families where mental illness, emotional disturbances, substance abuse, behavior disorders, neglect, abuse, or family violence are present. Most important, our prevention posture is one of hope and healing, believing all children and adults deserve the opportunity to work towards being well.

Similarly, our Intensive Family Reunification Services (IFRS) have been provided by Cornerstones of Care since 1992 to families and youth transitioning back into the home after foster care. Across both our reunification and crisisintervention programs, we have seen a success rate of more than 85% of children and families remaining.

There’s risk involved for a private sector institution/organization to move away from its traditional line of business. Why was the time right to do it?

Latosha: Change began for us during the middle of the Covid pandemic, which is quite powerful in

a historic sense because we were originally founded when a cholera epidemic had taken the lives of thousands of residents in the area. We reflected a lot on what Saint Vincents was created to do 175 years ago. We needed to be vulnerable enough to look at how we began and what we evolved into. We decided to take the conversation to the community and ask hard questions about how families see us, our impact, and what we could and should be doing. We had to learn from our history to find our future.

We determined that the biggest risk as an organization was to keep doing the same thing — staying the course was the risk and liability; the need for deep change came through clearly from the community.

– Latosha

Merideth: The pandemic was a great equalizer and revealer for us too. Coupled with all that was going on in the country regarding social justice and racial unrest, like most human and social service community-based organizations, we became keenly aware of how and where we were contributing. And we realized we had a choice; we would take an intentional and clear stance to do no harm and work to improve those systems where harm had historically been consistently pervasive.

It’s as if what was happening in society—the death of George Floyd, the inequity of which communities were being most impacted by the pandemic—were acting as a trail of breadcrumbs that we must follow backwards.

We began looking at the data in different ways. For example, we realized it was harmful not to ask questions about why children were coming into foster care. This process led to insights on where we can better impact and understand trauma much further upstream.

We follow a Sanctuary Model of trauma-informed care that, among other things, requires us to do no harm. Within this model, safety is the first and most important cornerstone. In order to help others heal from trauma and to adopt behaviors of growth and change that prevent further traumatization, we must first establish a foundation of safety. And so it was in that, holding up our own operational mirror, we realized that safety meant more than enacting programs that were trauma-informed, but in order to effectively avoid causing harm, we had to evolve and stretch to become trauma-responsive: actively

evaluating, assessing, improving and transforming our work in a way where harm was absolutely void of our hands. We pivoted our lens and our language to clearly understand and articulate both the wins and woes of the child and family welfare system. And once we started seeing and understanding the harm more clearly, it couldn’t be unseen. We started to understand where and what accelerated harm, and utilized the seven commitments of our Sanctuary Model including social learning and social responsibility to actively combat against it.

We needed to develop an ethos for how to slow down the pipeline. Foster care should not be used just to access vital mental health services. Foster care will always have a place, but it should be like the emergency room: reserved for those who absolutely need it to be safe, and time spent there should be as short as is safely possible. The entry point to foster care is far too broadly accessed.

We became clear that mission and must do’s take precedence over monetary gain, and commitment to mission and must do’s is what will lead us into a successful future. This did feel like upsetting the apple cart to a lot of people who were invested in the historic ways and it did and continues to require courage.

Latosha: When we began to ask the community questions, we were surprised and excited that there were other groups and organizations out there thinking the same things. There’s a growing realization and awareness that we can heal ourselves. We just recently facilitated a community convening that we hope is the beginning of something powerful and unifying; over 100 organizations from across St. Louis showed up.

What were the biggest challenges in changing direction for such well-established organizations and how did you deal with those challenges?

Merideth: One of the biggest challenges we faced was helping the board understand the harm that the child welfare system causes. Unless impacted directly by the system, it’s not common for people to understand the harm that comes from it. As an organization and business, there is an ethical and moral responsibility not to participate in causing harm and certainly not to benefit from it. We do not need to create revenue from causing harm.

It’s also the case that many of the traditional types of contracts—for example foster care contracts with the state—fall short of meeting the actual costs for providing the services. This raises the fiduciary issues that boards must deal with.

In essence, we faced two major challenges: addressing public perceptions about the relative harms and benefits of child welfare, and building trust among the board that if we do this right, we will build continued trust, partnership viability, and operational sustainability within and alongside the communities we desire to serve.

Latosha: It’s not only a journey to get board members there, but also to keep them there. We have to constantly stay grounded in our mission and not allow drift to occur. We’ve got to remain vigilant for not going back to old ways that may feel familiar or comfortable.

Fear is a challenge. Fear from the board that a shift in focus will hurt the business, fear from the team that they may not know how to make the shift or that the shift might somehow negatively affect their role or position. Fear of the new or unknown. Fear that the effort or cause is too big.

There may be times when the leader is the only person in the room who actually believes we can do this . Staying grounded and building trust are key challenges.

– Latosha

What guidance would you give to other leaders seeking to make similar changes?

Start with one thing. Start with that courageous “must do.”

– Merideth

Merideth: Don’t start with things that leave you less sustainable, and don’t do what we’ve always done. If there is one strategy that we can do to make a change, start there.

Also, partnerships are essential. We sit at tables where people are living their lives—use that experience to understand the risks and challenges. Learn how “disruption” and “broken” happens and come back to those tables with options for that courageous “must do.”

Latosha: The first bit of guidance I have is to honor your own journey and learn from it. Our personal experiences and our organization’s histories always brought us back to what was needed and how we could improve.

We were lucky that our board and staff were ready to make a shift, but that’s not true for everyone. Forming partnerships is essential.

Be bold and courageous in your vision and put data behind it. Ask the community the questions and then map out your way forward. Understand that we don’t have to throw it all away to start something new. We can stand firm on the new direction while honoring the journey to get us there.

With a state of urgency and a conviction that the broken must stop, we celebrate the rise of new and visionary leaders who embrace public-private partnerships, interagency collaborations and most importantly, the lived experience of Missouri youth and, families. In Missouri, we best describe the way as the spirit of “Ubuntu.”

The African philosophy of Ubuntu has its roots in the Nguni word for being human. The concept emphasizes the significance of community and teaches that ‘a person is a person through others.’ Purely translated, Ubuntu means, I am because you are, you are because we are. In other words, as human beings, there is a profound sense of connection—we rely on each other, therefore we are interdependent upon one another, particularly the most vulnerable. For the child welfare system to move away from its prolific tendency of disrupting homes and threatening the viability of family units, we cannot ignore the vast capability and catalytic power that rests in the hands and hearts of community. It’s a power to heal, to help and to restore individuals whole.

The magnitude of restorative and systemic transformation that is needed is not a journey that a single person nor entity can take on alone. Transforming our child welfare system is undeniably complex but far from impenetrable.

And we must remember what binds us in this fight is the heart of Ubuntu, a shared ownership of social responsibility, particularly for the most vulnerable in our communities. This means taking a unified voice, posture and promise that we will do all we can together.

E. Susana Mariscal, Ph.D., MSW is a full professor at Indiana University School of Social Work. She is a community-engaged scholar with an active research agenda centered on the prevention of child maltreatment and promotion of resilience among children and families. She directed Strengthening Indiana Families, a federally-funded, strengths-based, data-informed primary child maltreatment prevention project. Her current research includes an arts-based, trauma-informed, resilience-enhancing program for teens and their families; a collaborative partnership to support young families of caregivers who have cancer; and a national survey of Latina victimization and resilience.

Bryan Victor, Ph.D., MSW is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan and currently serves as an associate editor for the Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. His research focuses on maltreatment prevention and the use of artificial intelligence in social work practice.

Family Resource Centers (FRCs) have the potential to function as welcoming “third places”—similar to public libraries—that effectively support families while avoiding the stigma often associated with formal interventions. This article explores how arts-based programming can be integrated into FRCs to strengthen family protective factors and healing through non-clinical approaches. We provide an illustrative case example, detailing how federally-funded FRCs in Indiana offered a manualized sequence of A Window Between Worlds (AWBW), a 10-week trauma-informed nonclinical arts program. Facilitated by trained community members, AWBW emphasized safety, peer connection, and creative expression. Our evaluation showed significant reduction in trauma symptoms among caregivers who completed the program to fidelity, suggesting that trauma-informed arts-based programming, specifically AWBW, can enhance resilience without professional clinical training. Ongoing implementation of nonclinical programming that can enhance protective factors and promote healing and resilience is needed to ensure family resource centers function as effective third places for proactively and holistically meeting family needs and preventing maltreatment—while also expanding opportunities for healing, connection, and collective good. To achieve this, sustained investment in local FRCs and the networks that support them is essential.