CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

008 What Policy Can Make Possible

Jerry Milner & David Kelly

Directors of the Family Justice Group Foreword

010 Shrounda Selivanoff

Social Service Manager at the Washington State Office of Public Defense Parent Representation Program Introduction

032 In Brief

The Role of Congress in Improving the Child Welfare System

Representative Judy Chu

U.S. Representative for California’s 28th Congressional District

034

Supporting Tribal Families Act

Representative Don Bacon

U.S. Representative for Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District

My Perspective

060 Alexandria Ware Founder of Culture Creations Inc.

012

Features Reimagining How Cases End and Families Evolve

Shrounda Selivanoff

Social Service Manager at the Washington State Office of Public Defense Parent Representation Program

Tara Urs

Special Counsel for Civil Policy And Practice at The King County Department of Public Defense

016 Universal, Unconditional Cash Prescriptions Address Perinatal Poverty to Reduce Child Maltreatment

Alison Dickson, MD, MPH

Resident in Preventive Medicine Residency Program at the University of Michigan School of Public Health

Teagen Medlin

Mother of three young children, a resident of Flint Michigan, and a participant in the Rx Kids Program

Luke Shaefer, PhD

Co-Director of Rx Kids & Professor of Social Justice and Social Policy at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan

Mona Hanna-Attisha, MD, MPH

Co-Director of Rx Kids & Director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

024 Fund Kinship Caregivers to Help Keep Families Together, Not Separate Them

Josh Gupta-Kagan

Clinical Professor of Law at Columbia Law School

064 Kathleen Creamer, J.D.

Managing Attorney, Family Advocacy Unit

Community Legal Services of Philadelphia A Better Way

036 Yven Destin

038 Reducing Family Surveillance to Improve Child Well-Being

Anna Arons

Assistant Professor of Law, St. John’s University

School of Law & Impact Project Director, Family Defense Clinic, NYU School of Law

Features, continued

044 Policies of Compassion: Supporting the Health and Safety of LGBTQ+ youth and their families

Kristen Weber

Senior Director of Child Welfare at the National Center for Youth Law

Vida Khavar

Clinical Director at Family Builders

Bill Bettencourt

Senior Fellow with the Center for the Study of Social Policy

050 Ushering in Mandated Support for U.S. Educators

Chelsea Prax, MPH CPH

Director of AFT Children’s Health and Well-Being

054 Advancing Early Relational Health Policy in Support of Next Generation Flourishing

David W. Willis, MD

Founder, Nurture Connection

Cailin O’Connor

Senior Associate of Center for the Study of Social Policy

Artwork

030 System vs. Growth

Tia Humphrey

Kevin Burdick

Born 1985 in Flint Mi., then raised in Fenton Mi. I First attended Mott Community College, were I studied basic art. At this point I realized that Art would be my profession. I was later accepted to the Art Institute of Pittsburgh where I studied Animation and Illustration.

After school I started experimenting with different mediums, including Airbrushing and Aerosol. I was first given the opportunity to airbrush professionally at T-Rods in Flint Mi and later partnered with Psycho Customs in Bay City Mi. In the last few years, my focus has been on aerosol murals. Although airbrushing made up the foundation of my art career, aerosol art is becoming the creative outlet and freedom every artist seeks. After years of trial and error I now feel that I can provide high quality artwork to a wide range of clients and programs.

www.scrapsdesigns.com

Christopher Baker-Scott

Executive Director & Founder SUN Scholars, Inc.

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

University of Washington Seattle

Associate Professor

Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute

Director of federal policy for Partners for Our Children

April Lee

Director of Client Voice

Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Dr. Melissa T. Merrick

President and CEO

Prevent Child Abuse America

Jey Rajaraman

Associate Director, Center on Children and the Law, American Bar Association

Former Chief Counsel, Legal Services of New Jersey

Vivek Sankaran

Clinical Professor of Law, University of Michigan, Michigan Law

Shrounda Selivanoff

Social Services Manager

Washington State Office of Public Defense Parents Representation Program

Victor E. Sims, MBA, CDP

Senior Associate Family Well-Being Strategy Group

The Annie E. Casey Foundation

Paul Vincent, MSW

Former Alabama Child Welfare Director Consultant and Court Monitor

Justin Abbasi

Co-Founder, Harbor Scholars: A Dwight Hall Program at Yale

Laura W. Boyd, Ph.D.

Owner and CEO, Policy & Performance Consultants, Inc.

Angela Olivia Burton, Esq.

Co-Convenor, Repeal CAPTA Workgroup

Melissa D. Carter, J.D.

Clinical Professor of Law, Emory Law

Kimberly A. Cluff, J.D.

MPA Candidate 2022, Goldman School of Public Policy

Kathleen Creamer, J.D.

Managing Attorney, Family Advocacy Unit Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

Associate Professor, Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Center

Director of Federal Policy for Partners for Our Children School of Social Work, University of Washington Seattle

Adjunct Faculty, Evans School of Public Policy and Governance

Yven Destin, Ph.D.

Educator and Independent Researcher of Race and Ethnic Relations

Paul Dilorenzo, ACSW, MLSP

National Child Welfare Consultant

J. Bart Klika, MSW, Ph.D.

Chief Research Officer, Prevent Child Abuse America

Heidi Mcintosh

Chief Operating Officer, National Association of Social Workers

Kimberly M. Offutt, Th.D.

National Director of Family Support and Engagement Bethany Christian Services

Jessica Pryce, Ph.D., MSW

Research Professor College of Social Work Florida State University

Mark Testa, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Wendel, MSW, LSW

Co-Founder, Pale Blue International Consultant, Family Well-Being and Mental Health Systems

Shereen White, J.D. Director of Advocacy & Policy, Children’s Rights

Cheri Williams, MS Founder and Chief Co-Creator at CO-3

The Family Justice Group is grateful for the financial sponsorship of this issue of the Family Justice Journal by the Institute for Relational Health (IRH) at CareSource. We are happy to advance the work of the IRH in promoting relational health for families, children, youth and communities, particularly those impacted by our child welfare, juvenile justice and mental health systems and individuals with disabilities. We believe that discussing and bringing to light the harms of disconnection are necessary acknowledgements of the critical importance of relational health in all our lives.

Jerry Milner

Chief

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Editor

- in

David Kelly

Chief

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Design Director

Ann T. Dinh Design Consultant

Jerry Milner & David Kelly

Policy matters. Those who write and implement it have profound impacts on the daily lives of families, especially families struggling with poverty and other difficult societal conditions. People facing adversity most typically know what would help them. The problem is we seldom ask. If we take the time to ask, their insights would be instructive. Yet, meaningful inclusion of impacted individuals---real people whose lives have and will be most affected---in policymaking remains woefully inadequate. Too often, it’s a superficial exercise, tantamount to review and comment or a request to lend voices to premade solutions.

It should be no surprise then that there is a stark contrast between current child welfare policy and what families say would help. Where we could have a proactive, streamlined approach that addresses stated familial needs, we instead have a tangled web of laws and funding schemes that limit how and when we can help and fail to address root causes. This results in families not getting what they need, communities being undervalued and deep, enduring health, social, economic, and racial disparities. It also tills fertile ground to pit child safety against family support and other dangerous false dichotomies.

But despite all of this, there are clear pathways that can lead us in a much more humane, effective and efficient manner to keep families, communities and tribes strong and together.

In this issue of the Family Justice Journal, contributors offer compelling, common-sense solutions that are based on what impacted people say would be most helpful and grounded in additional sources of evidence. While perspectives vary, they are united in doing right by fellow human beings. Taken together, these policy recommendations propel a critical shift toward strengthening and supporting families, promoting and preserving vital relationships and thinking more broadly about permanency. The ideas shared should spark further thinking and lend support to additional legislative changes that recognize the centrality of our relationships to our health, prosperity and self-determination.

A young native woman passionately detailing the impact of child welfare practice on her community . . .

A grandmother raising her grandson to honor, know and love his father despite circumstances that keep them apart and ultimately preserving his memory after death…

Objective academics who have methodically studied policy, the outcomes it produces and the negative impact on parents, caregivers and children . . .

A pediatrician who sees daily the direct health impacts of poverty on children and their parents and how modest, short-term financial support can change their trajectories…

An educator who wants to get help to families instead of having them investigated for poverty . . .

Members of Congress who put aside partisanship to promote and sustain tribal family unity . . .

A young woman who experienced foster care speaking to the healing power of restorative justice …

Respected researchers demonstrating the impact of early relational health on child development and long-term well-being…

When perspectives such as these shape policy, it can lead to much better outcomes and experiences. They can inspire lawmakers from different sides of the aisle to jointly support policies that meet familial needs, prevent the trauma of unnecessary separation, and position children for success in life. It can lead to innovative, sensible use of public funding to prevent economic hardship, future dependence and more expensive interventions down the road. It can reduce the likelihood that harmful intergenerational cycles will continue, and it can provide prescriptions of hope.

Policy can be a tool for recognizing it is our relationships that make us human and our connections to community and culture that bind us together, lift us up and sustain us through life’s adversities. Policy can and should help ensure that this knowledge guides our work.

With something so important we cannot allow catchwords and phrases to divide us and take center stage over concrete, family-informed actions that will yield better results. It’s the impact on families that should matter most, not the name of the effort or the words used to describe it. Moreover, reliance on popular language also risks leading us to think we’ve done more than we’ve really done.

Likewise, we should not confine ourselves to relying on a singular model of evidence to justify meeting the most fundamental needs of all human beings, positioning people for success and helping them avoid child welfare entanglement.

So how, then, can policy create changes that go beyond tweaking a harmful system and truly strengthen families and communities? By directly addressing the issues that parents and caregivers most commonly raise.

• By implementing policy definitions that de-link poverty and neglect. We should not treat neglect the same as abuse. There must be a different approach. If money can fix the problem, provide money to meet the need, rather than 12 months of therapy that still won’t pay the rent or buy the food.

• By funding support for families who otherwise become vulnerable to separation. Ensure that existing programs, such as TANF, actually support families and are no longer misdirected to things that do not. Also, invest in the financial ability of new parents to meet their children’s needs when they are most likely to be unemployed and in need of assistance.

• By implementing policy that reserves the most intensive child welfare interventions for the most egregious circumstances. Restrict hotline reporting to situations where children are being harmed and fund alternate ways to get help to families who simply need help.

• By implementing policies that require active efforts to keep families safely together before family separation becomes an option. Fund community-based family supports, raise the bar for removing children, eliminate arbitrary negotiated timelines for permanently terminating children’s rights to their parents, and provide more funding for family support than for foster care and adoption.

• By swiftly passing H.R. 3461, the Strengthening Tribal Families Act, and expanding flexibilities for traditional tribal healing, wellness and caregiving practices across all title iv-e and iv-b programs and funding. Indigenous wisdom and cultural practices should be recognized as equally as valuable as western approaches and treated with the same respect.

• By requiring new child welfare policies to be sanctioned by families impacted by child welfare. Change the policymaking process itself to ensure that the voices of youth and parents carry the heaviest weight in determining the direction of change.

• By funding communities more and State removal agencies less. The community must be the face of family support. If we direct all the CAPTA funding, most of the title IV-B funding, and flex title IV-E funding to permit community funding, policy can make an unprecedented impact.

In these times of ever deepening divisions, othering, and wars of words, it’s parents, caregivers and children that suffer when resources are weaponized or harmful status quo orientations maintained. We can rise above the tendency to craft policy that doles out punishment and places limitations on worthiness. We can choose to see and be guided by our common humanity. And, when we do, we will all feel and be more human.

SHROUNDA SELIVANOFF

Social Services Manager

Washington State Office of Public Defense

Parents Representation Program

In January, as I finished giving testimony in our state legislature, the chair of the committee spoke up. She knew the dependency case involving my grandson had just ended. “Congratulations,” she said, “on finalizing the adoption of your grandson.”

“No,” I replied, “it wasn’t adoption, it was a guardianship.” And I thanked her for her work on HB 1747, a 2022 law that requires a court to rule out a guardianship before they can terminate parental rights.

Because of that legislation, which I had strongly advocated for, I was able to convince our state agency to allow me to resolve my grandson’s case with a guardianship rather than terminating the parental rights of my son Alexei. I was able to avoid adopting my grandson, which would have erased Alexei from the official record of his own son’s life.

In the hearing room in Olympia, I reflected on that legislator’s comments. I understood her confusion.

For so long in this system, success has meant finality, and finality has meant adoption

But what I couldn’t possibly have understood in that moment, however, was how much more the idea of “finality” would soon mean to me. The next day I learned that Alexei was shot and killed by the Tacoma Sheriff ’s Department while he was running away from a traffic stop. My world ended then. There are no words for it. I cannot make sense of the loss of my son, and I will not try to do that now.

But in this pain, I see this work of “child welfare” differently. It is clearer to me now that the current setup is for “finality,” this idea that things need to be concluded. That we can wash our hands of someone and believe we have done something good.

The United States does a lot of erasing: it erases people from their communities, from their connections, from their families. A central part of the American story is the legacy of erasing the

bodies and identities of Black people. Adoption, too, is an erasure; it erases parents from their child’s birth certificate and replaces them with new parents.

I could have never known that an event would happen that would remove my son’s presence from my life and from his son’s life. But if we had not passed HB 1747, if I had instead adopted my grandson, there would be a sickening feeling every time I looked at his birth certificate. I would have been reminded that I colluded to erase my family’s history—my own son. It is a disgusting proposition. Future generations need to know that my son’s life mattered—that he was here.

Thinking about HB 1747, I feel a small amount of peace and some serious unrest. I’m grateful that my son lived his last days knowing that he had rights. And he was grateful to know that I cared enough to fight for him. I think about the frustration, the misunderstandings, and the volatility that I experienced along the way. It was all necessary to keep us intact.

Through this process, I have come to believe that, more than the legal truth, there is a spiritual truth at work in what we do in this system. A child is born with far more than legal rights; a child has a birthright: to their ancestors, to their history, to the legacy of their people. The law can’t change Creation.

As my son returns back to his spirit, part of his legacy lives on in his child. It is for me to teach my grandson and to help him understand that his life is an offering to the ancestors, to respect all that was sacrificed for him to have what he has today.

When I think about the legacy my grandson has inherited, I think about my ancestors who endured the unthinkable. They fought, and they built, and they planned, and they believed that—one day— this would be different. Part of the legacy, for me, is teaching our children how much was sacrificed for them to have a life that wasn’t built on enslavement, a place where they can prosper. I want to share with my grandson the strength of his ancestors.

But I must also help him understand how, even today, none of this is designed for his advancement. So much of the world he will walk through has been designed for his demise. That is also part of our story.

In this system of “child welfare,” we can—we must—move closer to the beauty of Creation, to appreciate and love the people who have been

brought into our lives. And we must move away from the false belief that the law can design, deconstruct, or dismantle what has already been put in place by God. Our ancestors ask us to be in light, to truly love and be there for one another. From the start of my grandson’s case, I wanted him to be with his parents. I’ll never forget the day that I sat on that phone and listened to the state terminate his mother’s rights, with no attorney present, with no cross examination, no accountability. As I protested in that hearing the judge said, “be quiet,” and “our business is terminating her parental rights; your care and concern has no place here.” My care and concern had no place there.

Because of HB 1747, however, my grandson’s mother’s name remains on his birth certificate today. Since the case ended with a guardianship, there was no adoption, and there was no change to the birth certificate. My grandson has a mom and a dad, aunts and uncles, grandparents. He has a birthright to those people—that’s his lineage, that’s his legacy. I don’t want to be a part of changing that, I want to be a part of supporting that. Care and concern should always have a place.

Often in adoption finality is not just about severing ties in the legal sense, it severs connections in the physical and emotional and familial sense, and by doing that it removes spaces and options for healing. But life has many unknowns. Actually, it’s all unknowns. Closing doors, trying to securely lock them, leaves folks locked in just as much as it locks others out. As people age, we gather wisdom and experiences, and we change. Finality leaves no place for reconciliation, reconsideration, or healing.

The adoption story, which values finality, relies on an assumption: that everyone lived happily ever after. Yet, I believe that assumption hurts everyone involved. It fails parents who live with the wounds of termination for the rest of their lives. But it also fails the caregiver, who must live up to an impossible ideal. And it fails the child, who must perform a part in a fairy tale, without the freedom to acknowledge the challenges of real life.

On the other hand, HB 1747 recognizes something fundamentally true: even if the system wants “closure,” families are evolving; they don’t reach an end. Families and people are always in a state of change: messy, complicated, joyful change. If we leave the door open to change, we can welcome healing. But if we lock the doors, we deny ourselves the beauty of one another.

SHROUNDA SELIVANOFF

Social Services Manager

Washington State Office of Public Defense

Parents Representation Program

TARA URS

Special Counsel for Civil Policy & Practice at The King County Department of Public Defense

Shrounda Selivanoff is the Social Service Manager at the Washington State Office of Public Defense Parent Representation Program. She brings a fierce and passionate voice advocating for systemic change for parents and their children involved with the child welfare system. She was previously involved with the child welfare system. Through life challenges, she has persevered. She continues to learn more about the child welfare system from the perspective of a kinship caregiver to her grandson.

Shrounda’s child welfare experience birthed an advocate seeking to destigmatize parents and elevate the need for our society to value families’ diversity and uniqueness. Shrounda’s work is focused on centering parents’ perspectives to support their families.

Shrounda relentlessly pursues policy and system change toward preserving and strengthening families with a North Star, empowering and valuing parents as partners, and keeping families together. She keenly understands the power and impact of preserving families and the critical need for individual and collective transformation.

Tara Urs, special counsel for civil policy and practice at the King County Department of Public Defense. Tara has led the department’s efforts to transform dependency law in the state, drawing on our attorneys’ expertise to challenge a system that harms children and families and disproportionately harms Black and Indigenous families.

She has testified countless times in the state legislature, argued before the state Supreme Court, including In re Dependency of ZJG and In re Matter of KW, and authored numerous amicus briefs on key appellate cases. Before joining DPD’s management team, she practiced family defense at The Defender Association Division and, prior to that, worked as a staff attorney at the Brooklyn Family Defense Project.

Tara received her BA from Wesleyan University and her JD from New York University School of Law, where she was an Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Fellow and winner of the John Perry Prize for Civil Liberties and Civil Rights. She clerked for Judge Deborah A. Batts, U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of New York.

1 Richard Powers, The Overstory, pg. 115 (2018).

2 Sandra White Hawk, Generation After Generation We Are Coming Home, Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption (2006), 291 (“The very things that I was to be ‘saved from’ – poverty, abuse, and alcoholism – were thrust onto me by life’s natural unfolding. My adoptive father died as a result of a farm accident when I was six.”)

3 Susan Devan Harness, Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption (2018), 333 (“Yes, parents lost us as adoptees, but we have lost our entire family, entire tribes, who could have helped us navigate the dangerous waters we crossed, in ways our adoptive families could not. We needed them in our lives.”).

4 The legislative history of the bill (substitute house bill 1747, which passed in 2022) can be found on the Washington State Legislature website: https:// app.leg.wa.gov/ illsummary?BillNumber =1747&Initiative = false&Year=2021.

5 RCW 13.34.138(2) (a).

6 The dependency case can continue past age 18 if the youth elects to participate in extended foster care. RCW 13.34.030(6).

7 Washington has two different forms of guardianship, either of which can end a dependency case. One form of guardianship is a family law order pursuant to RCW 11.130 that

is available to any non-parent seeking legal custody of a child, and the other is a “dependency guardianship” pursuant to RCW 13.36 that is only available as a resolution of a dependency case. Between the two options, a guardianship under RCW 11.130 is easier to reverse if a parent comes forward later. A guardianship pursuant to RCW 13.36 can only be reversed on a showing of a substantial change in circumstances in the life of the child or the guardian (not the parent). However, both forms can be easily reversed on the agreement of all parties.

8 RCW 13.34.145(5)(a) (vii), (7)(b).

9 RCW 13.34.180(1)(f).

10 RCW 13.36.090, Laws of 2023, ch. 221, § 1(1), (ESB 5124).

11 Id. § 1(2).

12 RCW 11.130.215; RCW 13.36.050; RCW 74.13.062. Not addressed here, but equally important, are the many recent federal and state statutory and regulatory changes intended to facilitate kinship licensing. Laws of 2021, ch. 211, § 9 (E2SHB 1227) (requiring DCYF to create an initial license procedure during the period of emergency out-of-home placement and report about licensure to the court); 88 FR 66700 (federal regulatory changes to facilitate kinship licensure). A foster care license is a requirement for a guardian to receive GAP (or EGAP); historically very few relatives in Washington have been licensed, but the state is trying to improve.

As certain as weather coming from the west, the things people know for sure will change. There is no knowing for a fact. The only dependable things are humility and looking.1

At the conclusion of a dependency case, no one can know what any parent and child will need from each other in years to come, what they have to offer each other, or how they will change. It is hubris to think otherwise. Even when a court cannot agree to return a child home, no one can predict whether the caregiver will someday fall on hard times and need the support of the parent2 or whether the child will need the comfort of someone who has overcome the challenges they are facing.3

In Washington state, we have been reimagining how to end dependency cases, recognizing that change is inevitable. We envision a legal system that embraces growth, belonging, and family connections—a system that always wants to leave the door to healing open. Therefore, we have been working on ways to shift our practice towards ending cases with reversible legal orders, like guardianships, rather than supposedly permanent orders like adoption.

Of course, our ultimate goal is to ensure that families and extended families receive the support they need so that children are never removed, and families can go through hard times relying on one another, without state oversight, control, or oppression. But while we work to create such a world, in the meantime, we believe “child welfare” systems can do less harm by reimagining how cases end.

In our state, a dependency case does not end unless a child has been returned home to a parent for six months,5 the child ages out of the system,6 an order of guardianship is entered,7 or a parent’s rights are terminated and an adoption is finalized. Here— like the rest of the country, thankfully—most cases resolve with children being returned home.

But also like the rest of the country, the second most common outcome in Washington is adoption.

Hopefully, that is about to change. Because of new legislation championed by Rep. Lillian Ortiz-Self and supported by the Keeping Families Together coalition, our state must now prioritize resolving cases with a guardianship, instead of defaulting to termination and adoption.

These statutory changes have taken three forms: 1) changing the practice of permanency planning, 2) changing the law of termination, and 3) creating financial benefits and supports for guardians.

First, HB 1747 made changes to the permanency planning process in dependency cases, creating a new basis for a court to find “good cause” not to order our state agency to file a termination petition when “the department has not yet met with the caregiver for the child to discuss guardianship as an alternative to adoption or the court has determined that guardianship is an appropriate permanent plan.” 8

Second, the law made changes to the legal standard for terminating parental rights. Now, before terminating,

“the court must consider the efforts taken by the department to support a guardianship and whether a guardianship is available as a permanent option for the child.” 9

Third, the legislature has made a series of substantive changes to the benefits available to guardians to provide financial support for guardianship under the Guardianship Assistance Program (GAP). The legislature has made changes to 1) allow guardianship subsidies for non-relative guardians10, 2) ensure that (as with adoption subsidies) guardians can receive an ongoing financial subsidy even if the parent’s dependency case is not eligible for federal reimbursement11, and 3) allow subsidies for guardians of dependent children who enter minor guardianship using either form of state guardianship order.12

Even more significantly, the legislature has made financial benefits available to guardians that are not available as adoption subsidies, thereby encouraging guardianship over adoption. Unlike those who adopt, those who enter guardianships for dependent children under the age of 16 can

receive an ongoing financial subsidy—extended guardianship assistance payments (EGAP)—until the young person is 21 years of age, provided they are complying with some requirements.13 Adoption subsidies for children adopted under the age of 16 end at age 18.14

But as we look to prioritize guardianship, there are also questions we still need to answer. For example, although any child who is part of the guardianship assistance program also qualifies for state funded health insurance, some caregivers have questions about whether children in guardianships can be added to the guardian’s private insurance. Also, because guardianship ends at age 18, we have heard questions about whether a guardian would be “next of kin” in certain medical situations after the child becomes an adult, as well as questions about how we can ensure the guardian actually provides the EGAP subsidies to the young person after age 18. Finally, courts have questioned the role the caregiver should have in deciding whether the state should pursue guardianship or termination/ adoption. Should a caregiver get to decide that the state must pursue termination?

But even beyond these questions, as we have begun implementing these statutory changes, we have seen resistance in practice. In closed-door meetings with caregivers, social workers continue to question guardianship and seed worry about the parents: what if they come back?

It is apparent, therefore, that for these statutory changes to be effective, we must do more than just change the law. We must also collectively reimagine the role of the law in the lives of families.

In 2015, Anita Fineday, the Chief Judge of the White Earth Tribal Court, wrote about her experience speaking to the Tribal elders about how they wanted their laws of adoption to be written.15 The elders “voiced two clear and seemingly conflicting messages.” First, they described their custom of taking other people’s children in: “It has always been our way to take children in,

whether they’re family members, tribal members, or children from other tribes.” On the other hand, White Earth Nation did not believe in terminating parental rights, they said: “Parents should always be able to have their children returned to their care when they are ready.”

Out of this seeming contradiction, the White Earth Nation developed a process of tribal customary adoption, a result that did not require the termination of parental rights. Further, every customary adoption includes an opportunity for contact between the parent and child. These traditions recognize the uncertainty that is an unavoidable part of life. Sometimes the community needs to help raise a child, and sometimes a parent who was not ready becomes ready again.

Yet, the mainstream American legal system has long held the opposite view, looking to prevent uncertainty by entering permanent legal orders that severed children from their parents, permanently erasing their families of origin.16 Indeed, because preventing uncertainty has been the stated goal, the law has authorized extreme measures like changing a child’s birth certificate and sealing the original to protect children in their new, “better” life.17

Yet, as it turns out, human relationships are more complicated than anything that can be captured in a legal order.

We now know, for example, that even permanent legal orders are not always permanent. More than 66,000 adoptees ended up in the foster care system between 2008 and 2020.18 Among those children, “being Black, being older at adoption, or having been diagnosed with a mental health condition all were linked to statistically significant higher odds of returning to foster care.” In Washington, we have learned that adopted children make up a significant number of children whose parents refuse to pick them up from a psychiatric hospital or a juvenile detention center.

It is now well documented that adopted people are overrepresented in mental health settings and manifest higher levels of adjustment problems compared to their non-adopted peers.19 Children who experienced adoption are about 4 times as likely to have a reported suicide attempt.20 And while some have assumed that that these difficulties were the result of the adversities adoptees experienced prior to adoption, increasingly, adopted adolescents and adults are asking us to recognize that, for them, the experience of adoption itself is an emotional trauma.21

13 Compare RCW 74.13.031(13) with RCW 74.13.031(14).

14 Id.

15 Anita Fineday, Customary Adoption at White Earth Nation, Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare, CW 360: Culturally Responsive Child Welfare Practice, pg. 28 (Winter 2015).

16 Gabrielle Glasser, American Baby: A Mother, A Child, and the Shadow History of Adoption (2021), pp 117-143.

17 Id. at 130-131.

18 Broken Adoptions, USA Today, May 19, 2022, https:// www.usatoday.com/ in-depth/news/ investigations/2022/ 05/19/usa-todayinvestigates-whydo-adoptions-fail/ 9721902002/. Researchers acknowledge that it is an undercount of adoptions that disrupt. Some research suggests that 10–25% of adoptions end in disruption (breakdown of the adoption before legal finalization), and at least 1% to 10% end in dissolution (breakdown after legal finalization). Child Welfare Information Gateway, Discontinuity and Disruption in Adoptions and Guardianships, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2021), https://www. childwelfare.gov/ pubs/s-discon.

19 Susana Corral, et al., Psychological Adjustment in Adult Adoptees: A Meta-Analysis, 33 Psicothema 527 (2021) (“The outcomes most strongly influenced by adoptive status were angry emotions (hostility and anger), psychiatric care, drug abuse, and psychotic symptoms.”).

20 Margaret A. Keyes, et al., Risk of Suicide Attempt in Adopted and Nonadopted Offspring, 132 Pediatrics 639 (2013).

21 David Brodzinsky, et al., Adoption and Trauma: Risks, Recovery, and the Lived Experience of Adoption, 130 Child Abuse & Neglect 105309 (2022); see also Mindy Stern, Adoption Is Trauma. It’s Time To Talk About It., The Medium, Nov. 5, 2019; Angela Tucker, You Should Be Grateful: Stories of Race, Identity, and Transracial Adoption (2024). Also, we know that physical and sexual abuse can also occur in adoptive families. E.g. H.B.H. v. State, 192 Wn.2d 154, 160, 429 P.3d 484, 488 (2018).

22 E.g. Cassian Rawcliffe, et al., Maintaining Relationships with Birth Families After Adoption: What Are Adopted Adults’ Views?, Centre for Research on Children and Families Research Briefing, University of East Anglia (Oct. 2022), https://www. pac-uk.org/uea-andpac-uk-researchbriefing-maintainingrelationships-with-birthfamilies-after-adoptionwhat-are-adoptedadults-views/, (“It is traumatic enough to be separated from your mother without it being shrouded in secrecy.”); Sixto Cancel, I Will Never Forget That I Could Have Lived With People Who Loved Me, The New York Times, Sept. 16, 2021.

Legal systems have favored finality because lawmakers believed that children would be harmed by the possibility of knowing their families of origin, yet adopted people tell us that they have been harmed by not knowing their families of origin.22 Indeed, it has been clear for a long time that adopted young people will seek out their families of origin when they can, a process that has only gotten easier in recent years with social media and the advent of genetic testing. Legal orders that terminate a relationship can’t keep people apart if they want to know one another.

Recognizing this unavoidable uncertainty and these limits of the law can help us start reimagining. Faced with the sheer scope of what we cannot know, it may come as a relief to accept impermanence. Things will change. Whatever decisions a court makes now may need to be revisited later, a flexibility made possible by a guardianship order. We can’t predict the future and we need not pretend that we can.

We can, instead, imagine a system that adds loving people to a child’s life, that allows families to evolve, without attempting to erase any family members.

A parent who is unable to regain custody of their child within the timeframes of the dependency system will still have irreplaceable stories, traditions, memories, and love to give their child.

A child has a right to those stories, memories, traditions, and love. It is their birthright.

ALISON DICKSON, MD, MPH

Resident in Preventive Medicine Residency Program at the University of Michigan School of Public Health

Dr. Dickson is a General Pediatrician who has cared for many children suffering the effects of living in poverty. She is now a resident in the Preventive Medicine Residency Program at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, where she has been able to explore public health problems like infant poverty, and upstream solutions like the Rx Kids program. She believes that by melding science with love, Rx Kids can bring real healing. ”This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration

Mother of three young children, a resident of Flint Michigan, and a participant in the Rx Kids Program

Teagan Medlin is a 25 year-old mother of three young children, a resident of Flint Michigan, and a participant in the Rx Kids Program. She believes in helping and supporting others so that they can be their best selves, and in particular thinks that kids should have a chance to do that from the start. Teagan is working to become an addiction recovery counselor.)

LUKE SHAEFER, PhD

Co-Director of Rx Kids & Professor of Social Justice and Social Policy at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan

Luke Shaefer, Ph.D. is the Co-Director of Rx Kids and the Hermann and Amalie Kohn Professor of Social Justice and Social Policy at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. There he directs Poverty Solutions, a U-M presidential initiative that partners with communities to find new ways to prevent and alleviate poverty. Poverty Solutions has a proven track record of collaborating on novel evidence-based policy changes in the City of Detroit, with the State of Michigan, and nationally.

Co-Director of Rx Kids & Director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

Rx Kids is led by Mona Hanna-Attisha, MD, MPH, a pediatrician, and director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative. A nationally recognized child health researcher and advocate, Dr. Hanna-Attisha launched the community-partnered initiative in response to the Flint water crisis to improve outcomes for kids. She is also the Associate Dean for Public Health and C. S. Mott Endowed Professor of Public Health at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine.

“This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant D3349085, “Preventive Medicine Residency”, as part of an annual award totaling $400,000. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred.”

Teagan’s infant daughter Audrina reclines in a pink bouncy seat, a pink pacifier resting on her full, round belly. Teagan coos and chatters at her, coaxing brief intermittent smiles with a one-way conversation. “Hi, my baby. What’s the matter? Do you need a burp? Do you see mama? Who’s a good girl?” They are both glowing in the dawn of their parent-child relationship. And Teagan is excited to share that her 5- and 3-year-old children are also returning to her in four days, the first time that the family of four will be united.

Teagan experienced a period of active addiction during the pandemic. Financially dependent on the children’s father and cut off from other social support, she could not escape the substances he brought home. “It spiraled,” she says. “I needed him for the financials. If I could have separated, I could have kept [the baby] safe and healthy by myself.” At six months of age, Child Protective Services placed her second child with the first. “It broke me to lose them. I stopped caring if I lived or died because I thought I’d never get them back. And when I was done visiting them, my son would cry and cry. He never knew if he’d see me again.” Without a consistent address, a wardrobe, or transportation, she had trouble finding the employment she would need to become independent, and her addiction worsened. “I was at my lowest, in abandoned housing, on the streets. And everything that was supposed to help me just made me feel worse.” It took almost dying until she realized she “was put on this earth for two reasons,” Teagan says. “To be a mom, and to make it through active addiction so that I could be a recovery coach.”

Now living in recovery housing with her newborn, Teagan qualifies for monthly cash prescriptions as the mother of a Flint newborn through a new universal and unconditional program called RxKids. Sober for one year and two weeks and able to demonstrate her new income to the court, her first two children are returning to her next week. Through RxKids, she purchased a pack-and-play and a bouncy chair, clothes for each child, and ageappropriate toys. She bought diapers, wipes, pullups, “all the hygiene stuff they need, plus I picked

out bunk beds for the older two that I’m going to get.” The cash also allows Teagan the time to pursue job training as a recovery coach. When this assistance ends after Audrina’s first year, “I’m going to have some long-term stability for my family. I’m getting my license, my job… a trailer in the school district I know is best for them. This program changed my life .”

The child welfare system’s efforts to support children’s needs and strengthen families has complex effects on relational health between parent and child. For Teagan and other parents, the effect of separations in a system that focuses sharply on violence, abuse, and mental health disorders but doesn’t adequately address the complex factors linked to them—including economic challenges— can be emotionally shaming and functionally devastating. As the system strives for a holistic approach that prioritizes relational health, one area for focus is the financial support of parents struggling to meet their children’s needs. Most child welfare involvement is neglect, and most neglect is poverty, and babies are at highest risk. But evidence does exist that bolstering family financial security can improve child health outcomes and reduce child abuse and neglect referrals to better support whole, safe families.

Maltreatment is mostly neglect. In the US, one in three US children will experience a CPS investigation for child abuse or neglect (CAN) in their lifetime1. Although abuse and neglect are often conflated, most of the maltreatment revealed by those investigations is categorized as neglect. In the most recent National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Systems (NCANDS) report, 76% of statereported CAN referrals were for neglect2

Most neglect happens to kids in families with very low income. Eighty-five percent of the children referred for child maltreatment come from among the 37% of US children living below 200% of the federal poverty line2. Not only is the association between poverty and CAN referrals clear, but the relationship is also increasingly believed to be a causal one. A large review of 90 recent studies examining poverty and child maltreatment from 13 developed countries found strong and growing evidence for a contributory causal relationship between poverty and CAN. This review noted with clarity that the impacts of poverty on CAN are large in scale, and influenced significantly by the depth and duration of poverty3

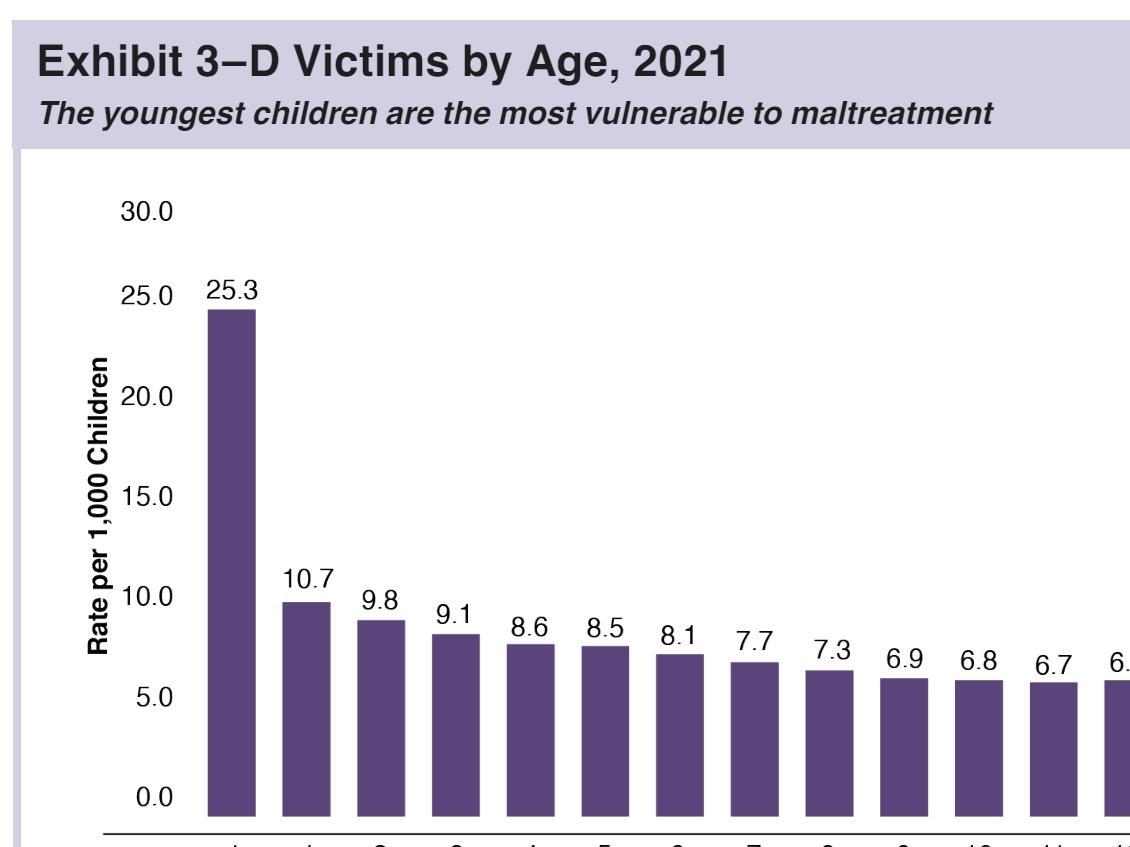

Babies are at highest risk of CAN. The riskiest period for CAN is the first year, when 25 in every 1,000 infants are victimized2. This is shown in Figure 1, drawn from the most recent NCANDS report. The rate of maltreatment in infants is more than twice that of any other year of childhood. It falls steeply after infancy, to around 11 per 1,000 children in the second year, and fewer again each subsequent year. But the effects often endure or grow. The breadth and persistence of maltreatment consequences, combined with the cost of investigation and management of cases, creates a large economic burden estimated by the CDC at $400 billion annually4

Poverty solutions are evidence-based CAN

Public Health Initiative, with RxKids co-director Luke Shaefer, Professor of Social Justice and Social Policy at the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan, where he directs UM’s Poverty Solutions Initiative. The RxKids program also partners with the Greater Flint Health Coalition and cash administrator GiveDirectly. Described as a “prescription for health, hope and opportunity,” it has three critical characteristics that are likely to support relational health by reducing child maltreatment:

1. The program begins prenatally and lasts through the infant’s first year.

2. Income support is provided throughout the period: $1500 in the third trimester, and $500 per month after birth.

solutions. Researchers have long proposed that the synergy between social protection and child protection should be strengthened5. Both the type and the quantity of economic insecurities impacted child maltreatment. Certain insecurities are reliable predictors of future CAN, including housing instability, material hardship, and income losses6. It is no surprise then to find evidence that socioeconomic interventions can reduce exposure to abuse and neglect; the strongest evidence is for housing, cash transfers, and income supplementation7. A review of evidence within the US suggests that in particular, increasing family income can reduce the rate of children in foster care8.

RxKids is an answer to infant poverty and its consequences for families in Flint, Michigan. RxKids is led by Mona Hanna-Attisha MD, MPH, a pediatrician, and director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric

3. The cash is unconditional, and eligibility is universal for pregnant moms in the city.

Perinatal Timing: RxKids is committed to supporting families prenatally (before birth) and through infancy. This timing is likely to reduce maltreatment because it addresses a period of greatest economic vulnerability, it is an evidence-based period to support other child health outcomes, it is a period of critical development for the child, and it is the best time to prevent CAN.

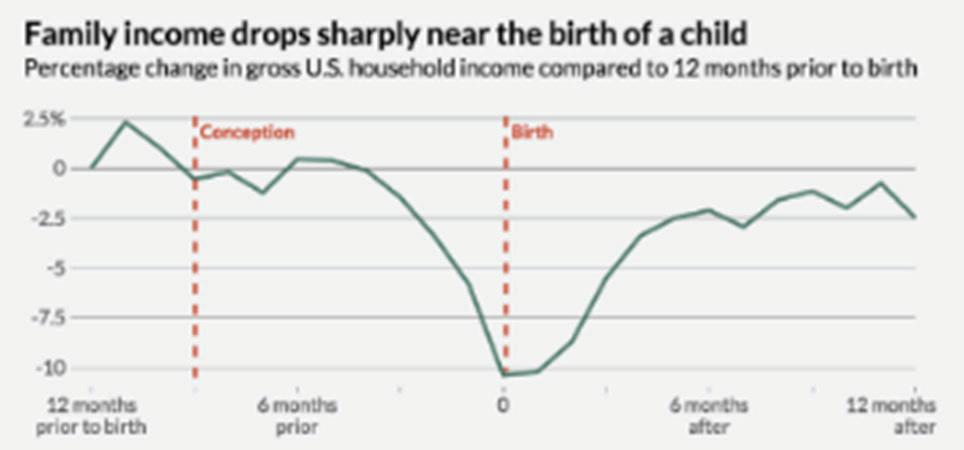

The perinatal period includes a poverty spike that can be addressed through social policy. Income loss (due to reduced labor market participation and lack of paid family leave) combined with increased costs (of childbirth and childcare) in the months surrounding childbirth make the perinatal period an economically vulnerable one for U.S. mothers and newborns9. There is an approximate 10% drop in gross US Household income perinatally, as shown in Figure 2 from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth10. This is particularly true for single mothers living without other adults, but it is significantly impacted even when accounting for income from unrelated household members, nearcash public programs, and tax credits11. Stanczyk et al found that the decline in income-to-needs ratios begins three months prior to birth, nadirs in the first and second months of the infant’s life (at 34% lower than pre-pregnancy baseline), and does not recover in the child’s first year. The impacts of income loss and childbirth costs cause the poverty

FIGURE 2

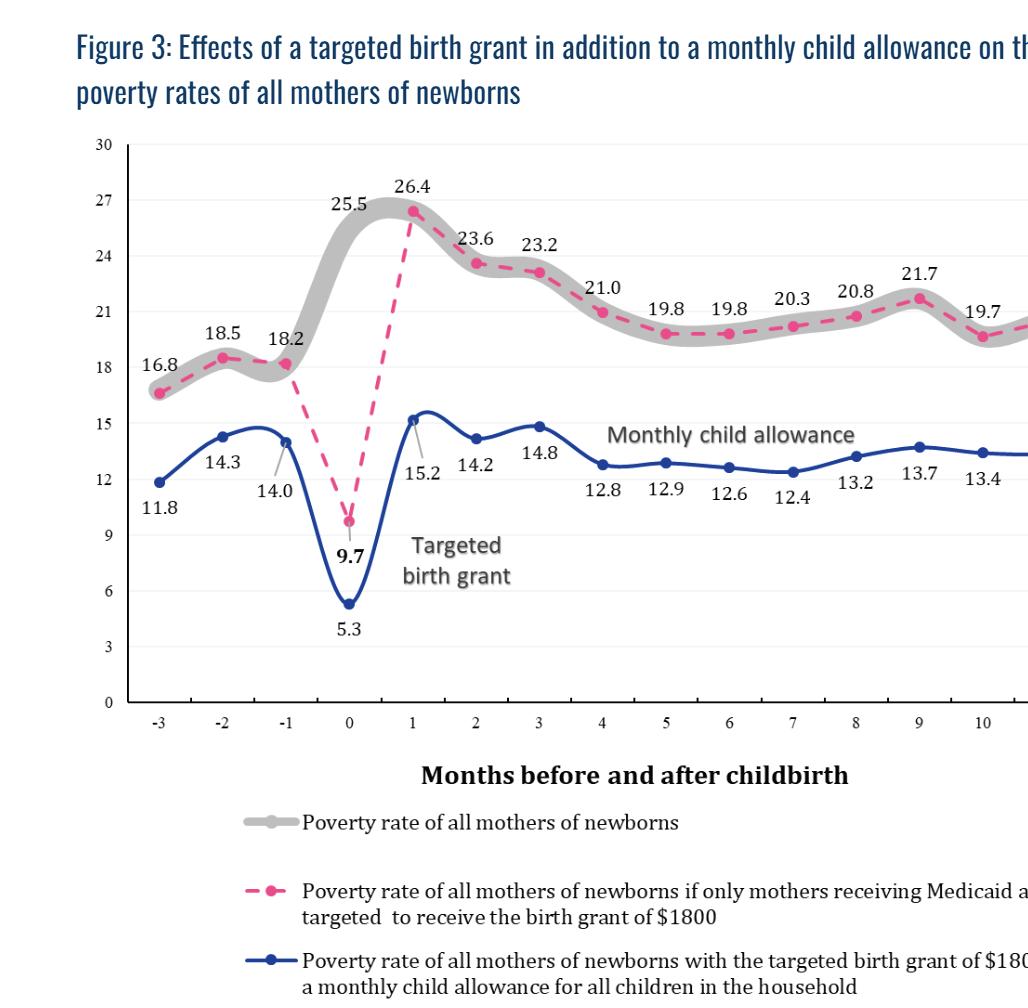

rate among all mothers to spike from 18% in the month prior to birth, to 26% in the month after birth12. The extent to which this occurs varies with birth parity and race and ethnicity: firsttime Black and Hispanic mothers are particularly affected, with 40% of Black and Hispanic mothers experiencing poverty around birth13. Modeling shown in Figure 3 by the Columbia University Center for Poverty and Social Policy shows that a perinatal cash transfer (such as that provided by RxKids) can eliminate that spike, reverse it, and, with small monthly child allowances, cut poverty rates by around 40%12

Prenatal income support works for other child health outcomes. The prenatal period is a good target for income-related interventions aiming to improve health outcomes for children through healthier pregnancies and early development. The same mechanisms that make cash transfers effective in reducing child maltreatment (namely increased family investment and decreased stress, discussed below) can be expected to function similarly in the prenatal period. Some studied prenatal interventions are inkind support (such as Food Stamps and WIC programs), or changes in policy affecting income in the prenatal period (such as the US Earned-Income Tax Credit). Literature has also examined true cash transfer programs, including conditional programs in Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, and the UK, and unconditional cash transfer programs in Spain, South Korea, Canada, Nepal, and Alaska.

Many studies examine the impact of prenatal cash or near-cash exposures on the outcome of birth weight (which is associated with infant mortality risk, developmental problems in childhood, and even adult health problems14), finding that birth weight is positively affected by cash and near-

cash transfers15-30. Prenatal support can also lead to a reduction in prematurity18,21,23,27, and improved Apgar scores (a measure of newborn transition to life outside the uterus)18,22 Cash or near-cash transfers have been noted to positively impact parental reports of wellbeing31, breastfeeding status, vaccinations at age 1year, and developmental delays at Kindergarten32. Some studies have extended the period of observation into adulthood, finding a positive effect on years of education, income, and adult chronic disease33, along with adult neighborhood quality, economic self-sufficiency, and decreased likelihood of incarceration34

Particularly relevant to researchers working on unconditional cash transfer programs in developed countries, a number of recent, large studies in Canada23,32, Spain20, South Korea28 and the UK21, find positive effects of prenatal unconditional (or in the case of the UK, essentially unconditional) cash transfers on birth and child health outcomes. In Spain, the effects were even found to extend to children pre-conception, when their mothers received the benefit for an older sibling well ahead of gestating subsequent children whose birthweight rose20

The prenatal period is a developmentally critical one. The period from conception to birth is one of rapid cell division and differentiation, setting the stage

3

for the complex structure and functioning of the human body. Maternal stress, poor nutrition, and exposure to toxins can have profound adverse effects on fetal development. These effects may impact growth, brain and behavioral development, and gene expressions that will affect the newborn through childhood and can even cause adult-onset diseases35. There is no part of gestation which is not considered critical for some organ system, and the entire length of gestation is considered critical for the development of the fetal brain and spinal cord36,37. Because this is a time of critical growth and development, maltreatment in this period may lead to lifelong health consequences in addition to suffering, illness, injury, and death1

Ties between the prenatal environment and outcomes are not limited to physical health domains. Research from Johns Hopkins University ties economic resources at birth to socioeconomic conditions in adulthood over a 25-year study period of 800 children38. The authors suggest that interventions preceding this stage have the potential to disrupt a “long shadow” cast upon adult socioeconomic outcomes by low economic resources at birth. Studies of the effects of access to additional prenatal support are confirming: access results in long-term benefits on human capital indices, economic self-sufficiency, adult neighborhood quality, and the likelihood of incarceration33,34.

The prenatal period is the right time for primary prevention. The primary prevention of child maltreatment is medically, socially, ethically, and economically superior to secondary and tertiary interventions. The high incidence of negative outcomes in the infant’s first year shown in Figure 1 makes this period too late for interventions to prevent child maltreatment. Effective primary prevention efforts should be in place before maltreatment occurs, and that means before birth.

Generous income support: Research leverages experimental and quasi-experimental methods to explore poverty solutions as a strategy for primary prevention of child maltreatment. Quasi-experimental studies in the US are often built around policy changes to examine impacts of income fluctuation in affected populations. Cash-transfer programs, on the other hand, have been studied internationally and in the US, using observational studies and randomized trials. Cash transfers may be conditional (on participation in healthcare or employment, for example) or unconditional. They may also be targeted to specific populations, or universal (such as the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend distributed among all

state residents). Transfer amount, frequency, and duration varies widely in the programs reviewed in the literature.

In the US, quasi-experimental studies link child abuse and neglect data to changes in the minimum wage, Earned-income Tax Credits (EITC), Child Tax Credits, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). These consistently demonstrate a reduction in abuse and neglect of children, with similar effects on maltreatment reduction hovering around 10% following a typical $1000 tax credit, or even from smaller amounts39-46

For instance, a $1000 EITC increase led to an 8-10% decrease in CPS involvement among singlemother low-income families in one study42 and reduced child maltreatment by 3%, and reduced days spent in foster care by 22.4%, according to a current working paper46. This same dollar amount in per-child tax refunds led to a 5% decrease in maltreatment reports in the week of and four weeks following receipt41. In another study, an EITC expansion decreased foster care entry by 7.4% per year47. In Wisconsin, a randomized controlled trial showed that even $100 of additional child support income to mothers receiving TANF benefits reduced screened-in child maltreatment reports by 10% in the following two years45. There are also studies of a generous EITC reducing Emergency Department visits for maltreatment44,48.

Studies of income instability show the same relationship between income and CAN. In one such study, children in Wisconsin whose families’ earnings dropped by 30% had an increased likelihood of CPS involvement around 18%49, and an additional increase in involvement of 15% for each additional drop in income. However, the same study showed that accessing supplemental income to offset the negative income shock can buffer against the risk of CPS involvement, particularly for families with children under 5 years old.

Universally, unconditionally given: Authors in the fields of poverty research and child welfare have long appealed for nuanced, non-coercive, and nondiscriminatory programming50,51. RxKids participation requires only proof of identification, pregnancy and/or childbirth, and residency in the city of Flint. The program’s universality and unconditionality convey potent values of dignity, trust, agency, love, empowerment, freedom, and autonomy. Universality normalizes receiving the aid and helps people to feel seen and supported by a broad village of supporters. With no other strings attached to RxKids cash prescriptions, the program shows that it is trusting families with

how to best care for their children. Moms like Teagan feel warmly welcomed by this low-burden, destigmatized approach: “Other programs are so complicated enough to where you want to give up, so they don’t have to help you. It makes me feel uncomfortable and judged, and like they don’t care. You want to give up, but you need the help, so you keep trying but it makes you feel really bad while you do it. Like you’re less than. RxKids, they want you to succeed.”

In Flint, this unconditionality is designed to uplift the dignity of every person who benefits, but it is also evidence-based. Means-tested programs and those conditional on employment do not reach all families in need. RxKids is expected to have nearly 100% penetrance, which can amplify the effects on child welfare outcomes. Reduced CPS involvement and increased family stability are strongly linked to universal, unconditional cash. In a working paper from the National Bureau for Economic Research, additional universal, unconditional cash transfers of $1000 from the Alaska Permanent Fund were associated with a 10% drop in the likelihood of referral to CPS, a lower likelihood of mother moving since the child’s birth, and a greater likelihood that a child is still living with their mother at age three52. On the other hand, conditional cash transfers requiring participants to work, attend appointments, or meet certain other criteria have shown mixed results. In Nepal, programs that were conditional on use of healthcare services had a positive effect on infant mortality, but programs conditional on work participation did not yield any positive effects53. In Delaware, increases in child neglect were demonstrated among those randomly assigned to a 1990s welfare reform program with strict work requirements and sanctions54

The scientific literature discusses several mechanisms by which income support may reduce child abuse and neglect. Among these, increased family investment and decreased parental stress top the list8,46,47,52. Universal, unconditional cash plays an important role in both mechanisms, making the process low stress for families and empowering them to determine how best to provide for their family’s unique circumstances. “It makes me feel confident, like I can do my job as a mom. I’m calmer,” Teagan says. For her, RxKids cash buys proper hygiene supplies and safe baby equipment. It supports her reunification with her two older children, her ability to pursue job training, and her plan for housing stability. A working paper evaluating New York’s Baby’s First Years unconditional cash transfer program shows that the transfers led to increased spending on child-specific goods and mothers’ early-learning

activities with their infants55. But every family can use the cash in the way they need. For some moms, the money covers rent, food, buys more time to bond with their baby before returning to work, or provides reliable transportation to work.

These aspects of the program may amount to more than individual and family effects. Researchers think that universal, unconditional payments can also boost civic engagement and community pride. Being trusted with the cash and respected while she accesses it helps Teagan feel “…excited. It makes me feel hopeful for the whole city of Flint. There are good people here and this program is something that can lift them up. They can get the chance they need, and the kids have a chance right from the beginning.”

Addressing poverty prioritizes the primary prevention of CAN, and it can be done with dignity, simplicity, and a sound scientific basis. It can even be rooted in love, a long-known component of quality health outcomes56. RxKids sets an example for poverty solutions that impact child welfare outcomes and create the conditions in which children and their parents can flourish together. Many pediatricians have called RxKids a dream come true, and many mothers, including Teagan, have called it life changing. Teagan has four days until her kids return: “I had a trial with them all last weekend, and it was awesome. They were all over me, just so much loving and snuggling. It was so, so good .”

1. Schneider W, Bullinger LR, Raissian KM. How does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment and parenting behaviors? An analysis of the mechanisms. Review of Economics of the Household 2022;20(4):11191154. DOI: 10.1007/s11150-021-09590-7.

2. Administration for Children and Families. Child Maltreatment 2021. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2023. (https:// www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/childmaltreatment.).

3. Bywaters P, Skinner G, Cooper A, Kennedy E, Malik A. The relationship between poverty and child abuse and neglect: New evidence. London: Nuffield Foundation 2022.

4. Peterson C, Florence C, Klevens J. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United

States, 2015. Child abuse & neglect 2018;86:178-183.

5. Abu-Hamad B, Jones N, Pereznieto P. Tackling children’s economic and psychosocial vulnerabilities synergistically: How well is the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme serving Gazan children? Children and Youth Services Review 2014;47:121-135. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.009.

6. Skinner GCM, Bywaters PWB, Kennedy E. A review of the relationship between poverty and child abuse and neglect: Insights from scoping reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review 2023;32(2):e2795. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ car.2795.

7. Courtin E, Allchin E, Ding AJ, Layte R. The Role of Socioeconomic Interventions in Reducing Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences: a Systematic Review. Current Epidemiology Reports 2019;6(4):423-441. DOI: 10.1007/s40471-019-00216-2.

8. Wood S, Scourfield J, Stabler L, et al. How might changes to family income affect the likelihood of children being in out-of-home care? Evidence from a realist and qualitative rapid evidence assessment of interventions. Children and Youth Services Review 2022;143:106685. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. childyouth.2022.106685.

9. Marti-Castaner M, Pavlenko T, Engel R, et al. Poverty after Birth: How Mothers Experience and Navigate US Safety Net Programs to Address Family Needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2022;31(8):2248-2265.

10. Stanczyk A. The Dynamics of Household Economic Circumstances Around a Birth. Washington Center for Equitable Growth working papers 2016 (https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-content/ uploads/2016/09/10042016-WP-income-volatilityaround-birth.pdf).

11. Stanczyk AB. The dynamics of US household economic circumstances around a birth. Demography 2020;57(4):1271-1296.

12. Hamilton C, David Harris, Christopher Wimer, Sara Kimberlin, Sophie Collyer, and Irwin Garfinkel. The case for a federal birth grant: a plan to reduce poverty for newborns and their families. Poverty and Social Policy Brief. Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University, 2023. (1) (povertycenter.columbia.edu/ publication/case-for-federal-birth-grant).

13. Hamilton C, Sariscsany L, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Experiences of Poverty Around the Time of a Birth: A Research Note. Demography 2023;60(4):965-976. DOI: 10.1215/00703370-10837403.

14. Wilcox AJ. On the importance—and the unimportance— of birthweight. International Journal of Epidemiology 2001;30(6):1233-1241. DOI: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1233.

15. Barber SL, Gertler PJ. The impact of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme, Oportunidades, on birthweight. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2008;13(11):1405-1414.

16. Strully KW, Rehkopf DH, Xuan Z. Effects of prenatal poverty on infant health: state earned income tax

credits and birth weight. American sociological review 2010;75(4):534-562.

17. Almond D, Hoynes HW, Schanzenbach DW. Inside the war on poverty: The impact of food stamps on birth outcomes. The review of economics and statistics 2011;93(2):387-403.

18. Hoynes H, Miller D, Simon D. Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2015;7(1):172-211.

19. Amarante V, Manacorda M, Miguel E, Vigorito A. Do cash transfers improve birth outcomes? Evidence from matched vital statistics, and program and social security data. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2016;8(2):1-43.

20. González L, Trommlerová S. Cash transfers before pregnancy and infant health. Journal of Health Economics 2022;83:102622. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022. 102622.

21. Reader M. The infant health effects of starting universal child benefits in pregnancy: Evidence from England and Wales. Journal of Health Economics 2023;89:102751. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco. 2023. 102 751.

22. Chung W, Ha H, Kim B. MONEY TRANSFER AND BIRTH WEIGHT: EVIDENCE FROM THE ALASKA PERMANENT FUND DIVIDEND. Economic Inquiry 2016;54(1):576-590. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ ecin.12235.

23. Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Nickel NC, et al. Unconditional Prenatal Income Supplement and Birth Outcomes. Pediatrics 2016;137(6). DOI: 10.1542/ peds.2015-2992.

24. Kehrer BH, Wolin CM. Impact of income maintenance on low birth weight: evidence from the Gary Experiment. Journal of Human resources 1979:434-462.

25. Bruckner TA, Rehkopf DH, Catalano RA. Income Gains and Very Low-Weight Birth among Low-Income Black Mothers in California. Biodemography and Social Biology 2013;59(2):141-156. DOI: 10.1080/ 19485565.2013.833802.

26. Hamad R, Rehkopf DH. Poverty, Pregnancy, and Birth Outcomes: A Study of the Earned Income Tax Credit. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2015;29(5):444-52. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/ppe.12211.

27. Lucas ADP, de Oliveira Ferreira M, Lucas TDP, Salari P. The intergenerational relationship between conditional cash transfers and newborn health. BMC Public Health 2022;22(1):201. (In eng). DOI: 10.1186/s12889-02212565-7.

28. Jung H. Can Universal Cash Transfer Save Newborns’ Birth Weight During the Pandemic? Population Research and Policy Review 2023;42(1):4. DOI: 10.1007/s11113023-09759-1.

29. Falcão IR, Ribeiro-Silva RdC, Fiaccone RL, et al. Participation in Conditional Cash Transfer Program During Pregnancy and Birth Weight–Related Outcomes. JAMA Network Open 2023;6(11):e2344691-e2344691. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44691.

30. Blakeney EL, Herting JR, Zierler BK, Bekemeier B. The effect of women, infant, and children (WIC) services on birth weight before and during the 2007-2009 great recession in Washington state and Florida: a pooled cross-sectional time series analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20(1):252. (In eng). DOI: 10.1186/ s12884-020-02937-5.

31. East CN. The effect of food stamps on children’s health: Evidence from immigrants’ changing eligibility. Journal of Human Resources 2020;55(2):387-427.

32. Enns JE, Nickel NC, Chartier M, et al. An unconditional prenatal income supplement is associated with improved birth and early childhood outcomes among First Nations children in Manitoba, Canada: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21(1):312. (In eng). DOI: 10.1186/s12884-021-03782-w.

33. Hoynes H, Schanzenbach DW, Almond D. Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review 2016;106(4):903-934.

34. Bailey MJ, Hoynes HW, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. Is the social safety net a long-term investment? Largescale evidence from the food stamps program. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

35. Fifer WP, Monk CE, Grose-Fifer J. Prenatal Development and Risk. Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development2004:505-542.

36. Moore KL, Persaud T. Clinically oriented embryology. The developing human 1993;10.

37. National Institutes of Health. Mother to Baby Fact Sheet: Critical Periods of Development. National Library of Medicine. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK582659/).

38. Alexander K, Entwisle D, Olson L. The Long Shadow: Family Background, Disadvantaged Urban Youth, and the Transition to Adulthood: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014.

39. Maguire-Jack K, Johnson-Motoyama M, Parmenter S. A scoping review of economic supports for working parents: The relationship of TANF, child care subsidy, SNAP, and EITC to child maltreatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2022;65:101639. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101639.

40. Spencer RA, Livingston MD, Komro KA, Sroczynski N, Rentmeester ST, Woods-Jaeger B. Association between Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and child maltreatment among a cohort of fragile families. Child Abuse Negl 2021;120:105186. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105186.

41. Kovski NL, Hill HD, Mooney SJ, Rivara FP, Morgan ER, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Association of StateLevel Earned Income Tax Credits With Rates of Reported Child Maltreatment, 2004–2017. Child Maltreatment 2022;27(3):325-333. DOI: 10.1177/1077559520987302.

42. Berger LM, Font SA, Slack KS, Waldfogel J. Income and Child Maltreatment in Unmarried Families: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Rev Econ Househ 2017;15(4):1345-1372. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/

s11150-016-9346-9.

43. Raissian KM, Bullinger LR. Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and youth services review 2017;72:60-70.

44. Klevens J, Schmidt B, Luo F, Xu L, Ports KA, Lee RD. Effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Hospital Admissions for Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma, 19952013. Public Health Reports (1974-) 2017;132(4):505511. (https://www-jstor-org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/ stable/26374155).

45. Cancian M, Yang M-Y, Slack KS. The Effect of Additional Child Support Income on the Risk of Child Maltreatment. Social Service Review 2013;87(3):417437. DOI: 10.1086/671929.

46. Rittenhouse K. Income and Child Maltreatment: Evidence from a Discontinuity in Tax Benefits 2023. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4349231.

47. Biehl AM, Hill B. Foster care and the earned income tax credit. Review of Economics of the Household 2018;16(3):661-680. DOI: 10.1007/s11150-017-93811.

48. Bullinger LR, Boy A. Association of Expanded Child Tax Credit Payments With Child Abuse and Neglect Emergency Department Visits. JAMA Network Open 2023;6(2):e2255639-e2255639. DOI: 10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2022.55639.

49. Cai JY. Economic instability and child maltreatment risk: Evidence from state administrative data. Child Abuse & Neglect 2022;130:105213. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105213.

50. Pelton LH. Separating coercion from provision in child welfare: Preventive supports should be accessible without conditions attached. Child Abuse Negl 2016;51:427-34. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.007.

51. Roelen K. Sticks or carrots? Conditional cash transfers and their effect on child abuse and neglect: researchers observe both benefits and harms of CCT programs. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38(3):372-82. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.014.

52. Bullinger LR, Packham A, Raissian KM. Effects of Universal and Unconditional Cash Transfers on Child Abuse and Neglect. NBER Working Papers 31733 2023.

53. Siddiqi A, Rajaram A, Miller SP. Do cash transfer programmes yield better health in the first year of life? A systematic review linking low-income/middle-income and high-income contexts. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2018;103(10):920-926.

54. Fein DJ, Lee WS. The impacts of welfare reform on child maltreatment in Delaware. Children and Youth Services Review 2003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S01907409(02)00267-0.

55. Gennetian LA, Duncan G, Fox NA, et al. Unconditional Cash and Family Investments in Infants: Evidence from a Large-Scale Cash Transfer Experiment in the U.S. Res Sq 2023 (In eng). DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2507540/v1.

56. Best M, Neuhauser D. Avedis Donabedian: father of quality assurance and poet. BMJ Quality & Safety 2004;13(6):472-473

JOSH GUPTA-KAGAN Clinical Professor of Law Columbia Law School

Josh Gupta-Kagan is a Clinical Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, where he founded and directs the Family Defense Clinic. He and his students represent parents in New York Family Court neglect cases and administrative proceedings regarding the abuse and neglect system. He is the author of over 30 academic articles on the legal systems affecting families and children.

Money impacts relationships. And when the money involved is a foster care subsidy to kinship caregivers, it can drive a wedge in relationships between parents and kinship caregivers that should be strengthened, not strained. Unfortunately, foster care funding incentivizes the “relational disruption”1 endemic to foster care, when it should instead support family members coming together to support each other and their children.

In contrast, Medicaid funding has increasingly supported family members taking care of each other and can provide child welfare with a model for funding family caregiving without disrupting relationships and without even requiring a family court or foster care case.

Consider a mother who lives with her aunt, and they both struggle to make ends meet. The aunt helps the mother take care of her infant child since she has a mental illness and sometimes uses illegal drugs. Her drug use increased following an assault by her ex-boyfriend. The child protective service (CPS) agency learns that the mother has left the child at home with the aunt for days and

*I suggest only that some version of this scenario happens frequently, not that the mother has neglected the child or that removing the child from his mother is appropriate or legal.

† In practice, some families find workarounds. For instance, I have worked on cases in which adoptions or guardianships are granted even though a parent visits their child at the adoptive parent or guardian’s home nearly daily, and the CPS agency and court would exercise some willful blindness of the situation. If a parent eventually moves in with the kinship caregiver, that can create the best of all worlds: the financial support without the parentchild separation. The fact that families must resort to workarounds, however, demonstrates a problem with the existing funding structure, not that the present structure is working.

has even brought the child with her while she uses drugs. Concerned for the child’s safety, the CPS agency convinces the family court to authorize it to remove the child from his mother’s legal and physical custody on an emergency basis.* The CPS agency then describes kinship foster care to the aunt: she can apply for a kinship foster care license, keep the child with her, and get a monthly stipend from the state that will go a long way towards making ends meet.

But that kinship foster payment comes with a catch: the aunt has to keep the mother out of the home. The aunt is frustrated with her niece but is also worried about the impact of CPS’s position; without a place to stay, her niece’s drug use could worsen, and accessing mental health treatment could be harder. And what kind of system pays you to keep a loved one away? Regardless, the aunt feels she has no real choice. She says yes, and soon is receiving a monthly stipend, while being drafted to enforce the CPS agency and family court’s rules that prevent her niece from living with her.