FAMILY JUSTICE JOURNAL

CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

The Family Justice Group is grateful for the financial sponsorship of this issue of the Family Justice Journal by the Institute for Relational Health (IRH) at CareSource. We are happy to advance the work of the IRH in promoting relational health for families, children, youth and communities, particularly those impacted by our child welfare, juvenile justice and mental health systems and individuals with disabilities. We believe that discussing and bringing to light the harms of disconnection are necessary acknowledgements of the critical importance of relational health in all our lives.

CareSource is a proud sponsor of both the Institute for Relational Health and The Family Justice Journal

004 Jerry Milner & David Kelly

Directors of the Family Justice Group Fall 2024

008 Hina Naveed

Policy & Legal Analyst for Racial Justice Initiatives

Children’s Rights

010 Kayla Powell

State Government Leader

Alumnus of Foster Care

012 Edison Red Nest III

Native Futures

014 Carlyn Hicks

Hinds County Court Judge

Subdistrict 1 at Hinds County Youth Court

016 Arnold Eby

Executive Director

National Foster Parent Association

018 Nina Shaw-Woody

Director of the Kansas Family Advisory Network (KFAN)

020 Christopher Sutton

Project Manager

Connected Communities-Thriving Families

Missouri Coalition for Children

022 Esther Sherrard & Tiqueena Bousselot

Founder & Consultant

E. Sherrard Consulting

024 Corey Steel

Nebraska State Court Administrator

Nebraska Supreme Court

Deb VanDyke Ries

Director

Nebraska Court Improvement Project Administrative Office of the Courts and Probation

026 Dr. Mona Hanna

Pediatrician & Director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

030 Janica Lockhart

Senior Vice president of Strategy & Impact for Akin

032 Kellie Hans Green

Child Welfare Expert

Director, Research & Development

Specialty Companies Y Complex Health Solutions CareSource

034 Dr. Lynda Gargan

Executive Director for the National Federation of Familes

036 Sarah Winograd

Co-Executive Director, Together with Families

038 Kristina Lucero

Director, American Indian Governance & Policy Institute, University of Montana

In this time when we’re quick to numb pain with medication rather than addressing its sources, assign labels and build walls, it’s no surprise that services to “fix” people are prioritized over resources to support them. It’s no wonder that funding is directed to pay for treating symptoms instead of going after the conditions that cause suffering. And it makes sense then that isolation and loneliness have grown in the wake of such approaches.

When we think about our

How often do our answers revolve around a service or clinical intervention? How often is the answer a government agency?

Why then for others are we so confident to assume it is?

For some, a clinical service may be necessary and lifesaving. But it’s also true that anything that is manualized and time-limited can only ever reach a part of us or a presenting condition and then it goes away. Even when it’s evidence-based there’s no guarantee it will work or be enough given life circumstances. Yet, this is where our greatest investments of the day lie and what current values permit.

This special issue of the Family Justice Journal calls for more enduring approaches and investments rooted in culture and community. Contributors offer testimony of what community-based support can make possible in people’s lives. It puts a human face on what is too often dismissed as less important than or inferior to formal services.

We invited a wide range of people from across the country to share their thoughts on and experiences with community-based support, how it keeps us connected, makes us feel like we belong and promotes relational health. We are grateful for their bravery, generosity, and wisdom in sharing sometimes highly personal experiences. As they make clear, community support can show up in our lives in many ways. It can come from families facing uncertain futures—even separation-- banding together, a faith community or groups of adults that have experienced foster care speaking truths together. It can come from being a part of a lacrosse team that teaches more than sport or a movie theater that serves as a place of connection. It can look like a baby parade and program that celebrates mothers and demonstrates the worth of ensuring infants and their mothers have their basic needs met.

Every accounting speaks to the positive benefits of feeling supported and valued. And all can rightfully be supported, but not controlled, by public and philanthropic partners. As a society, these are the human investments we need.

It’s our hope that the visual essays in this issue of the FJJ will resonate with readers, add further to the overwhelming evidence of the need to invest in families and communities and prompt legislative, policy and funding action to prioritize community-based support in its many forms and functions.

Editor - in - Chief

Jerry Milner

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Editor - in - Chief

David Kelly

Co-Director of the Family Justice Group

Design Director

Ann T. Dinh Design Consultant

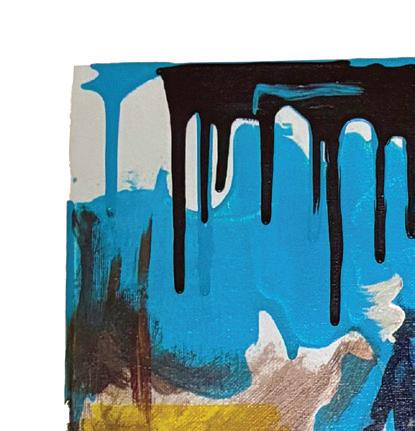

Page 14

All Hands on Deck: 185 handprints of reunited children, families, and community based providers during the Hinds County Youth Court’s 2021 Reunification Day Celebration honoring the 185 children who had been safely reunited with their families that year. This painting has since been utilized as artwork for the newly established Hinds County Children’s Coalition, a collective of community-based providers, systems stakeholders, and impacted youth and families.

Page 15

Maternal Justice: live painting rendered during the investiture of The Honorable Carlyn M. Hicks, highlighting the balance of the fair administration of justice with humanistic compassionate jurisprudence. Painting by Sabrina Howard.

Page 28-29

Mural done in partnership with Flint Public Art Project & Artist Johnny Fletcher

"When I painted the first mural for RX Kids featuring a family, I felt a personal connection because I had a daughter in my early 20s, and we weren't financially stable. A program like RX Kids would have been a great help during that first year of starting our family. It's an amazing initiative that supports many people in the city. I feel that’s the wonderful thing about art, it serves as a powerful tool to highlight and raise awareness of the challenges people face. I enjoy using creativity to draw attention to important issues and I love creating art for my community to make people smile." - Johnny Fletcher

Page 41

Johnny Fletcher @geezjohnny

Muralist and tattooer from Michigan, USA.

Christopher Baker-Scott

Executive Director & Founder

SUN Scholars, Inc.

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

University of Washington Seattle

Associate Professor

Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness

Research Institute

Director of federal policy for Partners for Our Children

April Lee

Director of Client Voice

Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Dr. Melissa T. Merrick

President and CEO

Prevent Child Abuse America

Jey Rajaraman

Associate Director, Center on Children and the Law, American Bar Association

Former Chief Counsel, Legal Services of New Jersey

Vivek Sankaran

Clinical Professor of Law, University of Michigan, Michigan Law

Shrounda Selivanoff

Social Services Manager

Washington State Office of Public Defense

Parents Representation Program

Victor E. Sims, MBA, CDP

Senior Associate

Family Well-Being Strategy Group

The Annie E. Casey Foundation

Paul Vincent, MSW

Former Alabama Child Welfare Director

Consultant and Court Monitor

Justin Abbasi

Co-Founder, Harbor Scholars: A Dwight Hall Program at Yale

Laura W. Boyd, Ph.D.

Owner and CEO, Policy & Performance Consultants, Inc.

Angela Olivia Burton, Esq. Co-Convenor, Repeal CAPTA Workgroup

Melissa D. Carter, J.D.

Clinical Professor of Law, Emory Law

Kimberly A. Cluff, J.D.

MPA Candidate 2022, Goldman School of Public Policy

Kathleen Creamer, J.D.

Managing Attorney, Family Advocacy Unit Community Legal Services of Philadelphia

Angelique Day, Ph.D., MSW

Associate Professor, Faculty Affiliate of the Indigenous Wellness Research Center Director of Federal Policy for Partners for Our Children School of Social Work, University of Washington Seattle Adjunct Faculty, Evans School of Public Policy and Governance

Yven Destin, Ph.D.

Educator and Independent Researcher of Race and Ethnic Relations

Paul Dilorenzo, ACSW, MLSP

National Child Welfare Consultant

J. Bart Klika, MSW, Ph.D.

Chief Research Officer, Prevent Child Abuse America

Heidi Mcintosh

Chief Operating Officer, National Association of Social Workers

Kimberly M. Offutt, Th.D.

National Director of Family Support and Engagement Bethany Christian Services

Jessica Pryce, Ph.D., MSW

Research Professor College of Social Work Florida State University

Mark Testa, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Wendel, MSW, LSW

Co-Founder, Pale Blue

International Consultant, Family Well-Being and Mental Health Systems

Shereen White, J.D.

Director of Advocacy & Policy, Children’s Rights

Cheri Williams, MS Founder and Chief Co-Creator at CO-3

“If mama and papa get detained, I will get custody of you,”

I explained

to my then

eight-year old sister, if I also get detained, then you will stay with my close friend while we get things figured out. It’s going to be difficult, but it will be temporary and we will see each other again.”

“If mama and papa get detained, I will get custody of you,” I explained to my then eight-year old sister, “if I also get detained, then you will stay with my close friend while we get things figured out. It’s going to be difficult, but it will be temporary and we will see each other again.”

When Trump was elected, many mixed-status families, including my own, faced the harsh reality of planning for possible detainment or deportation.

I had a heart-wrenching conversation with my little sister, explaining who would care for her if our family was separated. This fear and uncertainty echoed across our community, as many undocumented families were unsure of what the future held.

Unexpectedly, a group of older citizen community members stepped up, offering a unique and heartfelt solution. Recognizing the anxiety of undocumented parents with citizen children, they proposed building relationships by hosting dinners and getting to know the families. If parents were detained, they would care for the children and support reunification. While they couldn’t change immigration policies, they could be there for their neighbors.

Initially, skepticism ran high, but they approached with humility and patience, hosting weekly dinners and slowly earning trust. Over time, we had deep conversations, mirroring the one I had with my own sister. This support system was created without any government involvement—just neighbors helping neighbors.

Though the worst never happened, lasting bonds were formed. It was a reminder that real safety comes from the strength of community connections and that even in the face of systemic challenges, compassion and local support – without unnecessary government surveillance or intervention – can make all the difference.

Hina Naveed Policy & Legal Analyst for Racial Justice Initiatives Children’s Rights

Reflecting on my journey from growing up in foster care to navigating life as a mother of two, I’ve come to realize that the most meaningful support comes from people- not programs, services or systems. During my time in foster care, the handwritten letters from my Sunday School teacher and best friend were more than just paper—they were lifelines that provided comfort and connection when I felt the most isolated. As I prepared for college, it was my friend’s mother who made me home-cooked meals, gave me a bed to sleep in and helped me move into my college dorm. These acts of kindness weren’t just about meeting immediate needs—they were about emotional stability during critical moments.

Now, as a parent, I see the impact of community support through my children’s lives. My mentor’s batches of frozen meals and text check-ins, my coworkers’ gifts of diapers and baby essentials, and the Doordash and restaurant gift cards from friends have made the challenging early days of motherhood more manageable. My friends celebrate my children’s milestones, attend their birthdays, and include us in family gatherings, creating a network of support that extends far beyond immediate needs. These gestures and others- whether big or small- have made an immense difference. These experiences have shown me that community support is deeply personal and profoundly impactful. While systems can offer resources, it’s the people—our neighbors, friends, and local connections—who provide the true, transformative support. And it is through these networks that we find belonging and psychological safety to ask for and accept help.

Having been in foster care, I understand the hesitation to reach out for or accept help. Due to over a dozen placement moves, countless broken promises and an abundance of unreturned phone calls, my experience in foster care left me with the lingering fear of being an inconvenience and a burden—a fear that often prevents me from asking for what I need. Unfortunately, I continue to see systems be dismissive, minimizing or unreliable when people ask for what they need- often accusing them of trying to get over on the system

or demanding they figure it out on their own. It’s wounding to receive these types of reactions. For me, those wounds of being an inconvenience are still there even now as a grown adult with children

of my own. I have to recognize it and work through it so it does not stand in the way of making sure my own kids get what they need and deserve. But even knowing this I catch myself being reluctant to reach out.

To make support truly effective, we need to focus on building trust and fostering transformational relationships. While not innovative, three things strike me as important in doing this:

1. Prioritize Relationships and Social Capital: It’s often said that "it’s not what you know, but who you know" that matters. Social capital—our networks and transformational relationships — can be vital in accessing support. While systems invest in resources like 211 or online lists, these can be transactional and lack the human element. Investing in relational-based supports, such as peer navigation models, where real healing and support come from meaningful human connections, is crucial.

2. Transform Community Partners: People shouldn’t have to access programs or systems to get what they need. Everyday places should continue to evolve to better serve community needs and systems . For example, banks could offer financial literacy classes and cash-matching programs, laundromats could teach practical skills, grocery stores could provide education on healthy living and information about assistance programs, and barbershops could offer mental health navigation support. By empowering these everyday community landmarks, we normalize support and make it more accessible.

3. Foster Healing-Centered Engagement: Communities should adopt healing-centered approaches that emphasize culture, agency, and transformational relationships. This involves setting expectations for how we interact with one another and supporting community workers to understand their own biases and experiences. Investing in the well-being of our community’s helpers is essential for providing empathetic and effective support.

Kayla Powell State Government Leader Alumnus of Foster Care

Edison Red Nest, III, saw a need in the Native American community in his hometown of Alliance in the panhandle of Nebraska, and he stepped up to fill it. He started Native Futures in 2013 to help those in poverty and many who had lost their way.i

He has first-hand knowledge of the challenges Native youth face and what can happen when you go down the wrong path. He’s committed to making sure the youth he works with make better decisions than he did as a teenager, and sees connection to culture and tradition as critical to better trajectories. That’s why he and his wife started Native Futures, started a youth lacrosse league in Alliance, developed the drive-in movie theater in Alliance, and took over ownership of the local downtown theatre. That was part of their plan to give back to their community.ii

His goal is to teach others to live a better life by helping them learn to manage finances and to grow spiritually and through traditional parenting practices and Native-based services.

Connection, belonging and community are healing, restorative and can build brighter futures. As Edison shows us in his work with Native youth, belonging can look like playing on a lacrosse team, learning about old film equipment and watching movies at the historic town theater, or taking in a movie at the local drivein---all of which he maintains as places for connection.

i Alliance Times-Herald, Native Futures, June 20, 2020. Accessed at: https://alliancetimes.com/native-futures/ ii NSpire Today. I Wanted to be a Better Person, October 12, 2020. Accessed at: https://nspiretoday.com/i-wanted-to-be-abetter-person/

Community encompasses all things connection, security, belonging, and recognition.

Wherever people feel seen, heard, accepted, and encouraged - that is community. It is a very basic human need by which our hearts and our brains are wired to thrive - not simply survive.

By raising awareness about the importance of family support and preventive services, dependency courts can help foster a culture of support within communities, encouraging proactive measures to keep families together and children safe. This invites opportunities to influence policies that support family preservation and accessible communitybased resources through funding, training, and resources for child welfare services and community organizations.

Dependency courts can create a supportive framework rooted in community that empowers families to navigate challenges and work towards reunification. The emphasis on tailored interventions and collaboration with community resources not only addresses immediate needs but also lays the foundation for long-term family stability and resilience. As dependency courts continue to champion preventive measures and facilitate policy reforms, they play a pivotal role in nurturing a culture of support that prioritizes family preservation and the well-being of children. Through these efforts, dependency courts can significantly impact the lives of families and contribute to healthier, safer communities.

Hinds County Court Judge

Subdistrict 1 at Hinds County Youth Court

All parents need the same thing---whether you’re a birth parent, foster parent or adoptive parent--core support. We need to make core support available to all families where they live, and we need to develop an infrastructure that supports all families. Among the biggest needs I see are:

• Child care

• Early childhood intervention

• Respite

• Expanded child tax credit

• Adequate mental health services

• Peer- to-peer supports

To support all families as we should, we have to change the paradigm of thinking about what families need and how we can support them. For example, some people may think that expanding the child tax credit and making benefits available as an entitlement will create a new wave of dependence.

We often focus on the immediate costs and whether we think a particular course is too expensive or not. We don’t always realize the failing to address basic needs, such as child care, because it appears too expensive, we may lead us into much more expensive interventions later, e.g., the costs of incarceration and juvenile justice.

Our perceptions of families in need of support are standing in the way. We must invest money and resources in people to get the results we and they want. That includes kinship care when children must be placed. I always applaud kinship care. Families are the catalyst for healing. Kinship, foster, or preservation, we need an emphasis on family-based care.

During my time as a foster parent, including as CEO of the National Foster Parent Association (NFPA), I’ve developed and maintained empathy for birth parents. Early on in my experiences as a foster parent I was struck by my ability to access resources that could have helped families stay together had they been able to access those resources. I understood that there are many reasons that parents with kids in foster care cannot access needed resources. Child support is an example. Taking essential resources away from parents while requiring them to invest in themselves and their children does not make sense. You can’t expect parents to grow and develop as humans while at the same time taking away their few resources.

Foster parents must engage in many activities in order to meet basic needs, e.g., providing meal trains or clothes. That is energy that could instead be placed into forming supportive relationships with birth parents. At the end of the day, we often choose not to solve the bigger problem.

For example, let’s say a foster mother just received a sibling group of five children and she does not have adequate support. So, we take dinner and some used clothes to the family and go home feeling good about ourselves. And yet, we have not a system that could possibly have kept those 5 children in their family and built in expected supports for foster families if placement was absolutely necessary. We have not changed mindsets that allow this situation to repeat over and over again. I’m going to spend the rest of my days trying to change a system that in a lot of ways does not want to change. If we think we can just tweak the system to make meaningful change, we’ll never get to where we need to go.

It all comes back to our personal perspectives and beliefs.

What am I willing to do in order to make the plight of somebody else better?

Arnold Eby Executive Director National Foster Parent Association

Min. Nina, who directs the Kansas Family Advisory Network (KFAN), grew up in the Bronx where people “on the block” took care of each other and this gave her an understanding of what community was all about. “I grew up in a neighborhood where you ‘don’t mess with anybody on our block because we will take care of each other’ mindset.”

KFAN provides a range of community supports to families without judgment – a food pantry, resource closet, parenting classes, case management services, and a Bible study. Everything is grounded in the 8 dimensions of wellness –emotional, environmental, financial, intellectual, occupational, social, physical and spiritual. Her philosophy is that if she can help a family avoid having to “chose between what they need versus everyday obligations,” they will then be able to pay their bills and care for their children. “The least I can do is be a blessing to others, because I’ve had the same needs and have already walked along that same path.”

Min. Nina has held onto to her “don’t mess with the block” approach to life in her current work with KFAN. “Everyone who comes through our doors is part of this community. Our community is family. It’s all about honoring others, building relationships, and being able to offer a helping hand to our community. So many people call my husband and me Paw-Paw and Nanna even if we are not related, because we have a relationship with them and they know they matter to us.”

KFAN has learned over the years that children want to be with their parents, no matter the difficulties the parents may be experiencing. Min. Nina can often be heard saying, “A cookie cutter approach will not work with some parents, because no one is perfect and at one time or another in their lifetime, everyone may desire assistance with their own needs. Parents of 6 adopted daughters from foster care and 2 biological sons, she and her husband are currently kinship caretakers for 6 grandchildren.

How does she know she is making a difference?

“We make a difference one person at a time. When community members come to the food pantry or resource closet, this gives us the chance to plant the seeds of positivity, encouragement and hope. A caseworker came and brought a family, and the next week she

returned with another caseworker. People in the community have learned to send people to us because they know they will receive help without judgment.”

“I know we are making a difference because to us it is personal – it is personal.”

Nina Shaw-Woody Director of the

Kansas Family

Advisory Network

(KFAN)

Community-based family support is beneficial because without it I would not be here. It was community leaders, after school programs, caring teachers, basketball coaches, and neighbors who poured into me as a foster care youth. They corrected me, supported me, taught me skills that I would use and benefit from later in my adult life. It was those “Someone’s” who helped me identify the somebody I could be and have become. It took a village to address the deficits that accompany a youth in foster care, and my village provided connections that overcame my sense of being alone. It was the relationships that conveyed to me that I was a part of something larger than my experiences.

We must develop the ability to see humanity in all and be intentional in developing a relationship with all members of our community. We must seek to understand what has happened to people and families to fully understand their experiences and provide them with the support and compassion they believe they need. We must help families and communities identify their strengths and connect them with individuals and agencies that can aid them in building on those strengths.

Christopher Sutton Project Manager

Connected Communities-Thriving Families

Missouri Coalition for Children

She was guarded when we met. Understandably so. After talking through arrangements for our church to help cover her rent, I asked if she would like to tell me about her story. Not just the story of how her children had been placed in foster care, but her story.

I gave her my time, a compassionate listening ear, and over a year of relentless advocacy in and out of court. What I offered her was simple – genuine friendship. I had no idea what God had in store when he connected our church with this mother, and when he gave me this new friend.

I had no idea that our church would be her only support system, a place of belonging, during the most difficult period of her life. But God did. He knew she would need people to love her, believe in her, endure suffering with her and advocate for her. Genuine traumainformed friendship is the most critical community-based support that families need.

Esther Sherrard is a private consultant with 25 years of experience in child welfare policy, data and practice at the state and federal level. Esther has been a licensed foster parent for older youth and volunteers as a parent advocate. She has a passion for equipping churches and faith-based organizations to support families through her trauma-informed Fostering

My name is Tiqueena Bousselot. I'm a mother of 4 amazing children. I have faced my fair share of challenges as a mother, but by the grace of God, I have overcome them all. I wouldn’t be the mother I am today without God and my community-support in VA.

In the mother’s words, “through that community connection, I no longer felt lost, I felt seen, understood, accepted and not judged/condemned. That community-based, faith-based family support gave me the courage to fight even when I doubted that I had the right to continue fighting. They encouraged and supported me in so many ways but the most important was keeping my voice heard above the noise.”

Having your children taken out of your home as a mother is essentially taking your identity away from you, but community and faith-based support allows parent(s) to understand that they are not alone. This community that I created by accepting help aided in the healing of the grief I felt from all the challenges I was forced to endure, including the momentary loss of my identity as a mother.

Community-based family support is made possible when community leaders, funders, and agencies partner together with families who are experiencing system challenges. The days of siloed services that respond to and prioritize family needs without family input are transitioning into family-led, community-based support. This approach results in less stigma, enhances engagement, and fosters relationships, translating into stronger stability for the family.

Formal court involvement will continue to be a safety net for parents and children in the most severe circumstances and when community supports are not working. But when a family can voluntarily utilize community-based family support it keeps them away from the formal court process and reduces the trauma on the parents and the children. When community-based family support is successful, families stay intact, children thrive, and communities are healthier.

In Nebraska we are moving forward by partnering with and building on the Bring Up Nebraska initiative strategies. The Administrative Office of Courts and Probation in partnership with the National Center for State Courts Upstream mapping prevention and intervention strategy work to expand community -based family supports in our rural communities. Leveraging judicial leadership and court resources, community members develop a collaborative plan which identifies community strengths, assets, resources and needs that are focused on supporting families in their community. Bringing individuals with diverse backgrounds to the mapping conversation helps to enhance awareness of community needs and traditional (government) supports and/ or services, while providing an opportunity for creative responses that will improve outcomes for the families in their communities.

Corey Steel

Nebraska State Court Administrator

Nebraska Supreme Court

Deb VanDyke Ries Director

Nebraska Court Improvement Project

Administrative Office of the Courts and Probation

In June 2024, Flint Michigan was abuzz in celebration of children and families. The reason, Flint’s inaugural “Baby Parade.” Inspired by parades in the early 1900’s to draw attention to the need to alleviate poverty and support maternal and infant health---community stakeholders in Flint renewed the tradition for RX Kids. RX Kids is drawing from the past to create a better future---and national exemplar. The renewal highlights what modest investment in a child’s first year of life can make possible for their health, their families and the community at large. The parade was commemorated with a mural through the Flint Public Art Project.

Mona Hanna, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician and director of the Michigan State University-Hurley Children’s Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative. Her work in Flint led to and is responsible for the creation of Flint Kids Cook. A nationally recognized child health researcher and advocate, Dr. Hanna-Attisha launched the community-partnered initiative in response to the Flint water crisis to improve outcomes for kids. She is also the Associate Dean for Public Health and C. S. Mott Endowed Professor of Public Health at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine.

“This is how we’re supposed to love each other!”

- Dr. Mona Hanna

Jeremy & Janica,1984

at the ages of 2.5 & 9

and her brother,

I grew up with a sibling, Jeremy, who had significant mental and physical challenges and complex medical needs due to childhood illness. After falling ill with a rare form of E. coli at the age of three, my brother spent the remainder of his childhood in an institution, foster care then part-time residential care with weekends at home with his family.

Thankfully, my brother eventually received the level of care and support he needed while also maintaining a strong connection to his family and community. For myself and my parents, there was little that was offered to us to handle the strain of being caregivers to my brother. We were also always on the brink of entering poverty. It was a constant struggle.

It wasn’t until years later when I started working at Akin that I found out my childhood home was next to one of the family resource centers operated by Akin. It saddens me that my family was so close to a welcoming space with supports, services and resources in our own community without knowing it. It could have mitigated the hardship my family endured.

My family’s own experience has driven me to advocate in my role at Akin about the importance of supports in communities, especially through family resource centers. Family resource centers are for the community, by the community, and trusted by families. Families can easily and readily access various resources, services and programs based on their needs, hopes and desires. Increasing opportunities for more community-based supports is an investment in our nation’s families, instead of continuing the practice of family separation.

My deep commitment to the advancement of family resources centers is tied to the legacy of my brother and believing that families are best supported by communities where they live.

Janica Lockhart currently serves as the senior vice president of Strategy & Impact for Akin.

For decades, we’ve seen families experience adverse outcomes due to a lack of community-based support. Providing support to families and individuals within their communities and helping them stay connected to those they know and love are the best-known and most underutilized ways to keep people healthy. It’s at the core of relational health. On the other hand, social isolation, disconnection and loneliness contribute to unhealthy chronic conditions and early mortality.

If we know that our relationships are the one rare source of support that can be both preventative and healing, why is this so often not the focus of our work in health care and child welfare? Often, it does not fit neatly within a service category, a funding stream, a code or a box on a form. We may also think it is not clinical or scientific enough or that it meets the criteria for an evidence-based practice. When we favor process and procedure over relationships, e.g., moving toward a medical fee for service approach, the further we push community support away.

When critical relationships and social connection are not part of how we care for people, the negative consequences are grave-- shortening lifespans and degrading the quality of our lives. I saw this happening when I was a child welfare professional---uprooting children from everything they have ever known and loved with unnecessary parent-child separation, overmedication and isolation in group care. I see it now as a health care professional where parents and caregivers struggle to access the basic things their children need to be well.

And I saw it with my own mom as illness and treatment distanced her from the people and places she loved.

It is real for me.

If we care about each other, we need to move away from a disease and deficit mindset in healthcare and child welfare. We need community-based networks of resources, services, and programs available to assist individuals in meeting their diverse needs and enhance their well-being. Local organizations, non-profits, and government agencies often provide valuable resources, such as health clinics, job training programs, food pantries, youth and senior services and more. Using these supports and joining with families empowers people to achieve whole health goals and remain connected to those they know and love. In many ways, access to community-based support should be a fundamental human right, but it’s not a reality for many, especially those from marginalized communities and rural areas. Community-based support is the best way to start.

Kellie Green Child Welfare Expert Director, Research & Development

Specialty Companies Y Complex Health Solutions

CareSource

We frequently hear the African proverb,

“

it takes a village to raise a child,”

but we don’t often consider what that could mean for our child and family serving systems.

Villages are typically small groups of people who live and work together with strong relational ties, common values, and unique cultures. They are places where people know each other’s strengths, histories, and challenges. Businesses tend to be small and locally owned and reflect the traditions, needs and heritage of the inhabitants.

With that as a foundation, imagine an approach to supporting families that is built by the families of a community coming together to talk about what would be the most helpful to them. One mom says, “sometimes I just need a break,” a grandmother adds “I love these kids, but I don’t understand them. I sure wish I had some other grannies to talk to.” A dad chimes in “nobody thinks about us dads who are raising kids. We need help!” A neighbor adds “I love kids and would be happy to provide some babysitting. Why don’t we set up a safe place where our teenagers can get together?” The village elder slowly stands and says, “Let’s remember that we are a praying community and that every one of our families and children are precious. No one says “what we need is a big building with high fences where we can send kids far from here.”

“

Surgeon General

Vivek

H. Murthy recently stated

Raising children is sacred work. It should matter to all of us.”

Sacred work! How can we believe this and continue to separate families from their children in the name of “providing appropriate services?”

If it does, indeed, take a village to raise a child and if this is sacred work, the village becomes the keeper of the flame to ensure that families have access to what they need where they live.

Keeping children among familiar faces who have smiled upon them and are more likely to offer patience and care increases their sense of selfworth and belonging. Families in our systems often get the message that they have failed to belong, are faulty, and not good enough. A “village” approach can provide a different message and standard of care.

Growing up as a child of the Appalachian coal country, there were few professional supports available to families in my community. Rotating professionals often came through, but rarely stayed and couldn’t connect to a culture that was foreign to them. True, we were somewhat isolated, with the church at the center of our lives, and often suspicious of “outsiders.” But the culture clash led to our children being exiled to out-of-state placements in record numbers, many to never return to their families and their village.

Instead of fighting the culture of the village, imagine investing in the community to determine its needs and how to address them with respect for mountain values and beliefs. Imagine treating these poor, struggling coal mining families as the experts and deferring to their expertise.

Dr. Lynda Gargan

Executive Director for the National Federation of Familes

Rallying around each family, early and consistently prevents the trauma of crisis and separation. Humans are built for connection, for relationships and love, which lead to relational health, wellness, belonging and a sense of value and worth.

Dr. Lynda Gargan is the Executive Director for the National Federation of Families, the country’s largest national advocacy organization and voice for families whose children experience mental health and/or substance use challenges. During her prior tenure as Deputy Special Master, United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit, Dr. Gargan oversaw the settlement of a class action lawsuit, returning 1000 children placed in the foster care system to their communities. She more recently served as CEO for an agency specializing in Intensive In-Home Family Therapy services for families navigating both the mental health and substance use systems. As a native of West Virginia, Dr. Gargan has personal knowledge of the chaos that the opioid crisis created in families and the challenges that Appalachian families face when attempting to locate services.

What “treatment” could be better than that?

What if the power to transform the child welfare system wasn’t found in services, but in the strength of relationships and community that bind us together?

When a family's car breaks down, it’s not a distant program that steps in, but a neighbor who knows their name and offers a ride and a helping hand. When a parent is in the hospital, it’s someone from their community who steps in to care for their kids because they’ve been in their shoes. And when addiction pulls a mom back under, it’s not a stranger, but a friend who looks her in the eye, speaks truth, and drives her to rehab because they believe in her. This is what community makes possible—not through fleeting aid, but through bonds of love, trust, and belonging so deep they become a lifeline, a safety net no service could ever replicate.

At Together with Families (TwF), we witness the power of community every day. When families have hope, belong, and feel supported, they rise. Parents who once needed help become the ones offering it, "When I started dreaming again," says Jevon, a TwF Parent Executive Advisor, "I developed a curriculum to help parents learn about credit, job skills, and budgeting—things I needed help with."

When we give families the tools and opportunities to lift each other up, they become the force that strengthens entire neighborhoods, one connection at a time.

We must throw out the playbook that imposes programs from above and instead get on the ground with families and their communities, working alongside them—not over them. The solution requires time, patience, and—above all else—relationships. When we invest in community, we ignite a force that heals, prevents harm, and creates ripples of change that stretch across generations. This is the promise of community— it’s where families find their strength and where we all rediscover our shared humanity. The future of child welfare and family support doesn’t rest in services—it rests in the hands of families themselves, working with their communities to keep kids safe, prevent foster care, and improve family well-being. True change begins when we invest in communities and empower them to lead the way.

Sarah Winograd Co-Executive Director, Together with Families

Kristina Lucero Director, American Indian Governance & Policy Institute, University of Montana

As a single-mother of two (now) adult-aged young men, community-based support is and has been deeply important to me. It’s an issue that deserves intentional guidance about creating genuine connections for the individual and family with other families, employment supervisors, educational professionals, program facilitators, and medical and behavioral health providers.

Because Indigenous histories were rarely included in American school curriculums, many Indigenous families were left to learn about their traumas by being part of the western data that creates negative stories about Native Americans. This includes being disproportionately represented in the criminal legal system, child welfare cases, unsolved and unresolved missing and murdered relatives, to lower life expectancy rates. Most of us, unfamiliar with these systems that were not made to support us in overcoming historical and intergenerational traumas, are left to resolve these on our own.

As a young girl, my grandma would take me to powwows. Despite the urban nature, they became a source of connection to my culture and community---providing a sense of purpose, belonging and healing in even the hardest times. It wasn’t until college that I realized the beauty of urban Indian coming together to create their own communities after escaping what was once home in a pre-boarding school era.

Later, community-based support, for me, came in the form of a college professor, who stopped me after class I seldom attended to question my commitment to my education. After letting him know that I had an infant whose dad was not supportive of watching our child while in class, advised me that if I was in fact a teenage mom, that I needed my degree that much more, and to do whatever it took to earn my degree – including bringing him to class if need be.

I carried these experiences with me into my career as a criminal attorney: first as a Tribal prosecutor – constantly requesting more holistic and culturaltreatment program options to an overburdened defense attorney. This ultimately led to the creation of a reservation reentry program that offers wraparound support services to those involved in the legal system. In the next chapter of my career as a state public defender, I offered a genuine ear to those who were almost always at their lowest point in life – so that even though there were often convictions, my courtroom advocacy helped the Judge understand the underlying issues affecting my client, and my client ultimately felt heard.

To overcome the systemic mindset so many of our decision-makers are used to following, an opportunity for ongoing conversations to educate and continually revisit the policies that affect those who are disproportionately represented is a good start to achieving a community-based support system. Decision-makers need to know just how valuable community-based support systems are, how they meet needs that otherwise go unmet, help hold things together and how that is beneficial to everyone. Holding those in positions of power accountable to these measures of education, engagement and conversations will ensure that implementation of the new ways and systems are genuine and effective.

Ultimately, we are better together – and that requires understanding each other’s histories, needs and challenges, so that we can celebrate successes together.

Sometimes connection to others is the medicine we need.

Being with people who’ve seen some stuff.

People who’ve been through what you’re going through, know where you come from and are present without judgement.

It can make all the difference in a life.

To feel connection is a powerful thing.

To experience belonging is a loving thing.

They make us human.

They exist in and grow community.

They make us more likely to become our best selves, grow and heal.

We all know and feel this innately.

Jerry Milner & David Kelly Directors of the Family Justice Group

The Family Justice Journal is honored to feature original artwork, poems, and other visual expressions that speak to the experiences of systems impacted individuals, community/public art projects, and artwork promoting social justice in every issue of the journal, including the front cover.

Compensation is offered for every piece accepted with artists retaining all rights to their work and attributions made.

To learn more or submit a piece for potential inclusion, please write to info@thefamilyjusticegroup.org