TOADS ON THE BRINK

INFERNAL REALM DRAGONS

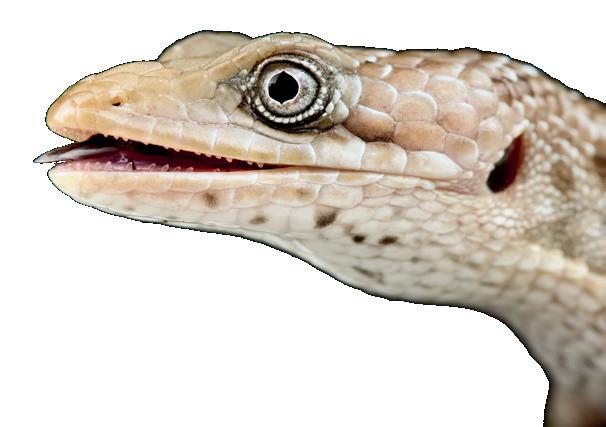

“In the vivarium, Texas alligator lizards make for one of the best pet lizards”. Roy Arthur Blodgett tells us more about these rarely kept lizards.

www.exoticskeeper.com • august 2023 • £3.99 NEWS • BREDL'S PYTHON • FER-DE-LANCE • FOLKLORE HUSBANDRY • BIOACTIVE ENCLOSURES

Dumerils boas, unique snakes from Madagascar, are regularly bred in captivity, but are we keeping them correctly?

EK Editor, Thomas Marriott joins conservationists in Bolivia to learn more about one of the most Endangered toads on Planet Earth: Atelopus tricolor.

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS

thomas@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING

advertising@exoticskeeper.com

About us

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex

CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4704

Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

Dr Michaela Betts

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather

Subscriptions

Follow us

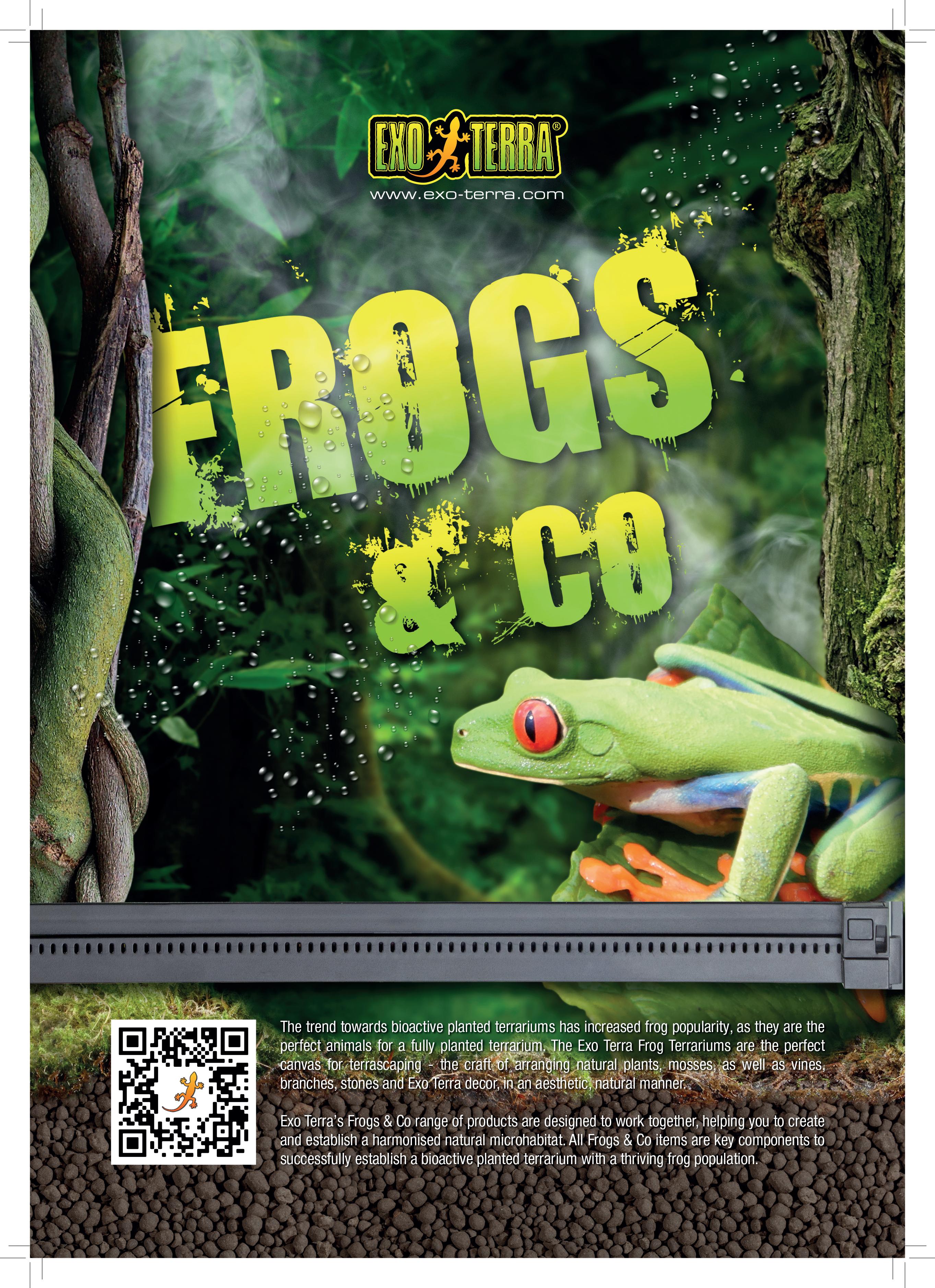

Show season is in full swing and we are prepping for a string of events throughout September. It has been a while since we have attended consumer shows and I cannot wait to catch up with our readers once again, especially given the huge increase in readership numbers off the back of our survey initiative. Part of the reason we have not done this sooner is that I have spent the last few months in South America and I am very pleased to bring you the first of several stories I have been writing whilst out here. I spent some time in a remote village in North Bolivia with the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative working on their Atelopus tricolor project, delivering community outreach and monitoring these once-thought-extinct frogs. The dedication of this organisation and the individuals at the heart of it is both impressive and admirable!

Our survey, at the time of writing, has reached 7,500 participants. We continue to create graphics, share statistics, and reach out to other organisations to support this initiative, but we still need your help to protect your hobby. Sharing through social media, email or even word of mouth can be so valuable within this tight-knit community of keepers. Already, our data is beginning to paint a realistic picture of herpetoculture in the UK, helping to inform legislation changes. It has

identified and recognised hundreds of invertebrate species, protecting them from the implementation of potentially problematic new laws. It has outlined the breadth of animals being kept in the UK and could influence insurance companies to provide keepers and their animals with accessible policies. We’ve noticed that the hobby is made up of a variety of ages and genders and that female keepers are more populous than males, which could enforce a better representation of social dynamics. We’re learning so much about our hobby because keepers want to be recognised and we thank you for your support.

Please follow our social media and tell friends, family and colleagues to participate in: www.survey. exoticskeeper.com.

Thank you.

Thomas Marriott Editor

Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

Front cover: Mexican redknee tarantula (Brachypelma smithi)

Right:

Chilean rose tarantula (Grammostola rosea)

Chilean rose tarantula (Grammostola rosea)

CONTACT US

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23 30 39

39 KEEPER BASICS: Bioactive

By

and Dr

50 FASCINATING FACT Did you know...?

EXOTICS NEWS

latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

ON THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

Atelopus

with the Bolivian

Initiative.

SPOTLIGHT

on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month

the Bredl’s python

Morelia bredli).

OF BOA

the

and

02 06 16 02

The

06 TOADS

Monitoring

tricolor

Amphibian

14 SPECIES

Focus

it’s

(

16 A DIFFERENT KIND

Dumerils boas in

wild

implications for captive care. 23TERRIFIC TARANTULAS

Dr Michaela Betts

Benjamin Kennedy 30DRAGONS OF THE INFERNAL REALM: An introduction to the Texas alligator lizard by Roy Arthur Blodgett.

Enclosures.

48 REPTILES AND RESEARCH Folklore Husbandry and Welfare Concerns.

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic animals

snakes use to live and hibernate.

Steve Reichling, Memphis Zoo’s Director of Conservation and Research, said: “We provide the snakes in our snake factories, which are funded by the U.S. Forest Service, into habitat that the Fish and Wildlife Service and Forest Service have developed. It’s just a perfect marriage, really.”

Louisiana pine snakes released in Memphis breeding programme

Five Louisiana pine snakes (Pituophis ruthveni) bred at Memphis Zoo in Tennessee have been successfully released into the wild as part of an ongoing conservation programme.

Memphis zoos and the Texas cities of Fort Worth and Lufkin have collaborated to support the conservation of the species which has been classified as ‘threatened’ by the federal government.

Every year, pine snakes are released into Kisatchie National Forest in central Louisiana, a precious resource for the conservation programme as the species cannot survive easily in other habitats.

This year alone, more than 100 captivebred pine snakes will be released. The forest is the ideal habitat for the snakes, with a high tree canopy, plenty of grass, and sandy soil. The area is also popular with gophers, the prey of the pine snake, whose burrow system the

New Stefania frog species described in in Brazil

A new species of Stefania frog, found in the Wei-Assipu-tepui tabletop mountains in Brazil, has been described.

The Stefania maccullochi sp. nov. is a larger species of the Stefania genus, with the female holotype measuring 72.9mm in length and the male measuring 54.6mm in length.

Stefania carries their eggs and froglets on their back and the new species is a medium brown with dark markings. The nocturnal frog is classed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The species was described by Philippe Kok from the Department of Ecology and Vertebrate Zoology at the University of Łódź in Poland.

Australian researchers discover extinct giant shingleback skink

An extinct species of shingleback skink has been discovered by researchers at Flinders University in Australia.

The Tiliqua frangens species, thought to have been covered with thick spiny armour, was directly related to modern shingleback skinks from Australia and were around the size of a human arm.

They existed in Australia around two million years ago during the Pleistocene period and went extinct around 47,000 years ago.

Dr Kailah Thorn, WA Museum Technical Officer for Terrestrial Vertebrates, described the extinct species: “Frangens was 1,000 times bigger than the Australian common garden skink and reveals that even small creatures were supersized during the Pleistocene.”

The discovery could offer useful insight into the plight of the modern species.

“Deciphering how Pleistocene animals adapted, migrated, or what eventually caused their extinctions might help us conserve today’s fauna, which faces pressures such as changing climate and habitat destruction,” said Dr Thorn.

Why are turtles always shopping?

2 AUGUST 2023 Exotics News

©Philippe J. R. Kok

©Memphis Zoo

A shingleback skink (T. rugosa rugosa) from Victoria, Today’s relative of Tiliqua frangens

Researchers hatch first gene-edited corn snake

Researchers at the University of Geneva and the University of Zurich have collaborated to create the first gene-edited corn snake, using the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Their efforts show that gene disruptions are responsible for differences in scale placement in the snakes which aid their movement.

American crocodile lays viable eggs via ‘virgin birth’

The first known case of parthenogenesis in an American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) has been recorded at Parque Reptilandia in Costa Rica. The crocodile has been kept alone for 16 years and produced viable eggs in 2018, aged 18.

Researchers at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, the Chiricahua Desert Museum, Illinois Natural History Survey, Reptilandia Reptile Lagoon and Parque Reptilandia have recently published their findings that the

They like to shell out!

The experiment involved injecting five scaled female corn snakes and breeding them with both scaleless corn snakes and heterozygous males, meaning they have two forms of the same gene. The results show that the snakes have no dorso-lateral scales due to a disrupted EDARADD gene.

The females laid 69 eggs, 54 of which hatched. Four were scaleless, laid by a female that had mated with a scaleless male. The others were all scaled, apparently due to a recessive gene.

eggs were produced via parthenogenesis.

Parthenogenesis is the process of an animal producing viable young without any other genetic contribution. The phenomenon has been recorded in invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles and birds.

While none of the 14 eggs laid by the crocodile hatched, despite seven being transferred to an incubator, researchers reported that they had been viable. One had progressed to the form of a recognisable crocodile hatchling that was almost identical to the mother.

Prefer to get a quote than a joke?

Visit

3 AUGUST 2023 Exotics News

britishpetinsurance.co.uk

Victoria, Australia.

International Herpetological Society update

The International Herpetological Society (IHS) enjoyed another successful Reptile Show on 24th June.

The show was well received by visitors, with a generally positive reaction to the new Milton Keynes venue. June’s show was the first time the event has been held outside its usual venue in Doncaster in over a decade and was another successful day for the IHS.

Unfortunately, unknown circumstances have caused the

ON THE WEB

IHS to cancel the upcoming 3rd September show. The society has been keen to re-ensure members that this was not due to the fault of the venue, the society or anti-reptile keeping organisations. The HIS is actively looking for an alternative venue with the hopes that the event can go ahead later.

Alongside the success of the show was the sad news that at the end of April, Doreen Brooks, the first female president elect of the IHS, and membership secretary since 2008, passed away. She was a much-loved member of the society who was an integral part of the shows and a familiar face to all who attended.

Websites | Social media | Published research

THIS

MONTH

IT’S: BOLIVIAN AMPHIBIAN INITIATIVE

The Bolivian Amphibian Initiative (BAI) was founded in 2007 with the mission of preventing extinction of endangered species in Bolivia. They believe that every species deserves to survive.

www.bolivianamphibian.org

4 AUGUST 2023

Exotics News

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

6

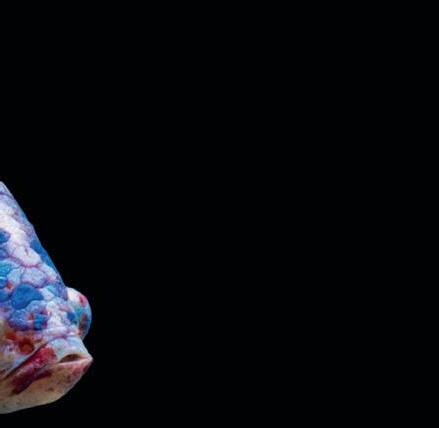

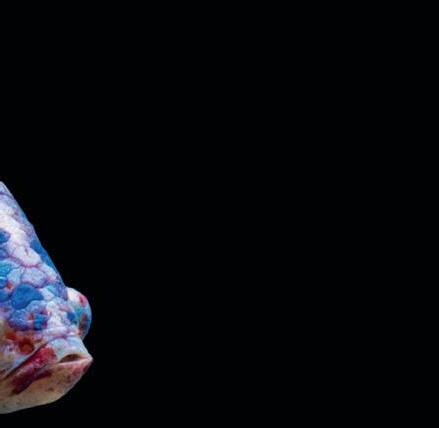

Atelopus tricolor ©Thomas Marriott

Monitoring Atelopus tricolor with the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative.

TOADS ON THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

Few groups of amphibians are quite as imperilled as the Atelopus toads of Central and South America. With 99 recognised species of Atelopus (commonly referred to as stubfoot toads, harlequin frogs and toads, and other colloquial names) all except five species are either Endangered, Critically Endangered, Extinct in the Wild or Data Deficient. Several species have been considered extinct for decades, only to reappear in extremely delicate ecosystems in small, localised populations. One species for which this mysterious Lazarus tale rings true is the three-coloured harlequin toad (Atelopus tricolor).

Thomas Marriott, Editor of Exotics Keeper Magazine joined the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative in May 2023 to understand the complexities of protecting a species on the brink of existence.

Three colours

The “three-coloured harlequin toad” is a species of Atelopus that was previously found in tropical and subtropical Andean forests of southern Perú and Bolivia. It is the most Southernly occurring species of Atelopus and the only species found in Bolivia. Atelopus tricolor was once considered a common species across its reasonably extensive range but seemed to almost vanish in the early 00s, with no sightings of the toad from 2003 until January 2020. After a re-classification of A. tricolor’s conservation status in 2019, herpetologists began searching for the rare toads once again. In 2020, by some miracle, a Bolivian photographer named Mauricio Pacheco, managed to locate a toad in the Caranavi Province of La Paz, Bolivia. He

contacted the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative immediately and work began to protect the toad. A three-phase project was outlined to first understand the toad, then understand the habitat and then create strong relationships with the local communities that live alongside this rare species.

In 2020, four specimens were found. Since then, the BAI has found more individuals within the area and is carefully monitoring the population which sees seasonal fluctuations each year. A spokesperson for the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative said: “More attempts to try to find other new populations were unfortunately unsuccessful. During this period, we found that the habitat where

8 AUGUST 2023

Toads

on the Brink of Existence

this species is present is under high risk because it is surrounded by different agricultural and even touristic activities that could wash off the only known population of this critically endangered toad. At the same time, we are evaluating the presence of Bd in the species and exploring if other species in the area are affected. We also found that local communities and local authorities were not aware of the presence of this toad, they want to do something to improve the situation of this species, but most of the time they come up with some ideas that could be not the most beneficial for the species.”

Now, the organisation has unfortunately discovered the

worst, confirming that the toads do carry Bd but are seemingly unaffected by the fungal disease. Patricia Mendoza-Miranda is the President of the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative. She told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “Of course, Chytrid is a big threat. We now know that the population here does have Chytrid so we need to monitor their health but also be very careful about the spread of pathogens. We have a strict biosecurity protocol when working with this population. We must disinfect our boots when entering the site and again once we leave the river. So far, it looks like the toads are surviving with Chytrid and the population is healthy, but we have only been monitoring them for two years, so we still have a lot

9 AUGUST 2023

Toads on the Brink of Existence

Author, Thomas Marriott with an Atelopus tricolor ©Thomas Marriott

to learn. It is also difficult to explain to local people that ecotourism does not work here. This year, we have the opportunity to establish ecotourism in the area to help the local community, but not with the toads. Perhaps birds would be better, and we can work with local people to educate them on other species in the area.”

It is not just Chytrid that threatens these toads. Environmental factors are thought to present an even greater threat than the deadly fungal disease. Patricia explained: “Atelopus are found in from tropical wet forests along the Pacific coast and the Amazon basin to the montane and paramos regions of the Andes. A. tricolor need a very unique habitat and have very specific temperature and humidity requirements. Unfortunately, the climate in Bolivia is changing. This year, for example, we have not had as much rain as in other years, it has been extremely dry! The people say this is because we are not taking care of the forest. This could have a serious impact on the toads.”

“Contamination of water sources is also a very dangerous threat. The education about the ecosystems and environment is not good here and the local people use pesticides in their soil when they farm. These chemicals can run directly down the river and this poses a big problem. We still need to learn more about the impact of this but I think that pesticides are certainly affecting the Atelopus here.”

Three phases

BAI is currently working on a three-phase plan that will inevitably span 2 years with the Atelopus tricolor Having already spent two years in the field, monitoring the population almost every month since the project began, attention is now turning towards a long-term model of protection. The primary method here is through community outreach, although the project has also recently put forward proposals for the funding of a captive-breeding project.

Patricia continues: “The third phase is research. We need to know the species so we have the data available to us if we need to set up a captive breeding project in the future. Also, education is very important, too. We need to work with authorities over time and also work with students to teach them about the project and the biological tools we are using for the Atelopus Project. Phase three is community outreach. Our main goal for this project is that the people protect this species and it is only the project coordinator of BAI that works with the people. I collate the project but it is down to the community to take the lead on this.”

Whilst joining Patricia and Rene Carpio in the field, we visited two primary schools and delivered talks to students and teachers about the importance of conservation, particularly that of Atelopus tricolor. Throughout the week, Patricia also delivered presentations within the local

10 AUGUST 2023

Patricia and Rene in the field

community to other stakeholders who could potentially protect the toads. “We need them to think that Atelopus is his or her species, so they become the protectors of the species” adds Patricia. “We have created stickers on Whatsapp of ‘Aty’ our cartoon Atelopus mascot, that the children can use when sending messages. We know children spend more time looking at their phones than in the forest, so it is important that we create ways to remind them of the Atelopus.”

As well as developing mascots and producing novelty masks and various other creative outreach ideas, the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative also work with fundraising organisations to provide educational books on a wide range of biodiversity across the country. When presenting the books to a school’s headteacher, he told us that the snake on the cover of the book was a bad omen and that if a black and red snake crosses someone’s path, they will have bad luck until they kill the animal. Patricia explained: “There are a lot of false tales about reptiles and amphibians in Bolivia, particularly in rural communities. We call these ‘mitos’. For example, some species of amphibians including Critically Endangered Telmatobius are said to spread skin diseases and warts if a person touches them. We are working hard to create comic strips that dispel these myths, but it is very difficult to change a person's mindset when their parents and the generations before them think that something is true. Luckily, there are no mitos around the Atelopus as they are very small and in a very restricted area. The local people do not visit the streams at night because it is dangerous, so they don’t see them too often.”

The monitoring process

Patricia and Rene spent one week in the Caranavi Province as part of the project. During this time, the populations are monitored. This is usually done at night as it is easier to spot and identify the toads, although it is possible to monitor the population during the day. Patricia and Rene had set up a camp on the grounds of a local primary school close to the Atelopus population, sleeping in tents and cooking food each day before undertaking different tasks. Some of these tasks included outreach projects to build relationships with local people, book donations, habitat analysis and mapping, environmental data recording and more. Rene would measure temperature, UV and humidity levels periodically through the day. May marked the “winter” season for the region, when the amphibians are less active. As BAI visit the Atelopus location roughly each month, the exact environmental data needs to be collected as frequently as possible to paint an accurate picture of the toad’s requirements.

After visiting two local communities and cooking some dinner, we headed out to the Atelopus site. This is a fast-running and very steep stream that trails down the mountainside. Equipped with headlamps, waders, cameras and long-sleeved tops we clambered down the stream in search of the toads. Several data sets were required for each toad. Basic health checks such as size (SVL) and weight were necessary to understand the toads. Females are typically larger than males and as with a few species of Atelopus, the three-coloured harlequin toad population is dominated primarily by males. Females are generally larger than the males, so they are quite easy to identify.

11 AUGUST 2023

A newly metamorphed Atelopus tricolor froglet ©Thomas Marriott

Atelopus tricolor being assessed for Chytrid ©Thomas Marriott

Toads on the Brink of Existence

Understanding the sex ratios within the population will provide valuable data on the natural history of the toads, the feasibility of the population and help inform potential future captive breeding projects.

The individual toads are then identified to help keep track of numbers. Each animal has a unique dorsal pattern that Patricia photographs and cross-references with a database of similar images at the office. This has allowed BAI to confidently identify just over 30 unique individuals in the two years that the population has been monitored. During this trip, we also discovered a newly metamorphed Atelopus froglet. At little over 5mm in length, it was impossible to take any useful readings of this animal and extremely difficult to photograph. However, as the first Atelopus tricolor froglet photographed (perhaps even sighted) in over 20 years, its presence alone was a valuable insight into the population’s health and reproductive patterns.

The adult toads are also swabbed for Chytrid before being released back into the same spot where they are found. In most cases, this is atop a low-lying broad leaf close to the water’s edge. Patricia told us that most of the frogs return to the same rough location each time they are monitored. If, for example, a specimen escapes whilst being photographed, the researchers have a very good chance of finding the exact same animal in the same patch of river the following evening. This means that monitoring such a tiny population is comparatively successful because finding and identifying the individuals is quite straightforward once the initial challenge of accessing the river is overcome.

Captive Breeding

Last month, Patricia and the rest of the team at the Bolivian Amphibian Initiative submitted a proposal for funding to embark on a captive breeding project for Atelopus tricolor Having already successfully bred Telmatobius culeus for over a decade, the organisation sees great potential in formulating a captive population to protect and reinstate the population from potential future hazards.

Patricia continued: “I think captive breeding could definitely work for Atelopus but it is very difficult with this species. We have far more males than females and we only have a few individuals isolated in a small area. This is very different to Telmatobius for example. It is necessary, however, because there are many threats here so we don’t have time! Perhaps the next threat that arises will wipe out the Atelopus altogether. We have many years of experience with Telmatobius and have now put together a good plan for the Atelopus that we feel will work.”

“We would have to first do a breeding programme with a model species, perhaps Rhinella. We don’t know exactly which species we will use, but we are studying other species that occupy this habitat to inform our decisionmaking. Rhinella is in the same group as Atelopus, which is ideal. First, we need to learn about the model species, then we can start the project with Atelopus tricolor.”

The Bolivian Amphibian Initiative is currently in the process of reaching out to donors to support the scheme. Science, particularly herpetology, is underfunded in Bolivia. For a country with some of the greatest levels of biodiversity in the world, there is not a single laboratory available for herpetologists to complete DNA sequencing when describing new species. Instead, samples are shipped abroad at very high costs and therefore, herpetological breakthroughs are consistently thwarted by financial challenges. Luckily, the dedication of BAI is helping to protect species at a grassroots level and hopefully in the coming years, the work of Patricia, Rene and the entire BAI organisation will pay off with international support for this very rare and very unique little amphibian.

Patricia concluded: “Bolivian Amphibian Initiative, in my opinion, is like a phoenix. I worked with BAI for many years, but in 2018 BAI started again. The people that work with BAI are extremely passionate about frogs and conservation and it’s very important to be surrounded by these kinds of people. Now, BAI has members and volunteers. We are trying to give students and members their own projects within BAI, because we have many species that need

12 AUGUST 2023

The unique dorsal patterns of Atelopus tricolor ©Thomas Marriott

conservation projects within Bolivia. Now we have members from different regions in Bolivia that work with active members, passive members and volunteers. Each member works in his or her city with their own project. For example, we have Felipe Tellez in Sucre who has a project with Telmatobius simonsi BAI gives him the resources to work on this. In Cochabamba, we also accept proposals from members and students and BAI provides financial support. This allows us to work with a wide variety of species.” BAI spent many years studying Telmatobius

The species Telmatobius culeus was once Critically Endangered, now it is Endangered and that is very important to our team. The BAI now works with Atelopus and we really hope that we can do the same thing here.”

The future of Atelopus

Sadly, a mix of threats similar to those that affect the three-coloured harlequin toad also imperil almost every other member of the Atelopus genus. Whilst some are more at risk of Chytrid and others are perhaps more endangered by habitat alteration, a global concerted effort to protect the genus is needed to see this group of amphibians survive long enough for the next generation of conservationists to even attempt to

protect them. A paper published in 2005 by Venezuelan Herpetologist, Enrique La Marca et al states that “Of [at the time of writing] 113 species that have been described or are candidates for description, data indicate that in 42 species, population sizes have been reduced by at least half and only ten species have stable populations. The status of the remaining taxa is unknown. At least 30 species have been missing from all known localities for at least 8 yr and are feared extinct. Most of these species were last seen between 1984 and 1996. All species restricted to elevations of above 1000 m have declined and 75 per cent have disappeared, while 58 per cent of lowland species have declined, and 38 per cent have disappeared.” Sadly, the situation looks even more perilous and whilst new species have been described since 2005, even more have been confirmed extinct or described as localities of existing species. For such a widely distributed genus of amphibians, populations reducing to single streams and rivers across a once enormous South American range paints a deeply disturbing picture of conservation in the tropics.

In some cases, the removal of wild populations of Atelopus for captive breeding has saved entire species from extinction, as is the case with Atelopus

zeteki, the Panamanian golden “frog”. The last remaining of these toads were collected in 2006 and were filmed for the last time on the same expedition for the Sir David Attenboroughnarrated BBC documentary ‘Life in Cold Blood’. Since then, zoological institutions across the US, fronted by San Diego Zoo have captive-bred the species and produced over 500 toads. However, with the threat of Chytrid and deforestation still rife in the cloud forests of West Panama, these toads are unable to be released into the wild. Whilst initiatives such as the Panama Golden Frog Project are working with local communities and protecting reserves that may one day host truly wild “golden frogs”, even the most successful captive breeding attempts face immense challenges when reinstating such delicate species. However, the more we learn as a herpetoculturist community and the more information that is shared between keepers of all amphibians, the greater chance accredited institutions stand at successfully producing Critically Endangered species. A change in attitudes around the environment at both global and localised levels, combined with sheer dedication from conservation programmes may be the only way forward for the harlequin toads of the Atelopus genus.

13 AUGUST 2023

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

The wonderful world of exotic animals

Bredl’s python (Morelia bredli)

The Bredl’s python is a species of Morelia sometimes referred to as the “Centralian” carpet python. It is named after the crocodile conservationist, Josef Bredl. They can reach a rather impressive size of 8 feet in length and typically have better temperaments than their coastal ‘carpet’ cousins. Coming from the centre of Australia, these snakes are exposed to some of the harshest conditions on earth with summer highs above 40°C and winter nighttime temperatures dropping below freezing. This makes them reasonably hardy, although the keeper must be able to provide gradients within the enclosure to achieve the highest husbandry standards.

Choosing a large vivarium, situated in a cool room with a powerful spot bulb (and perhaps a ceramic heat emitter) to create a basking spot of 35°C should formulate an appropriate

temperature gradient. Ferguson Zone 2 lighting should be installed and there is even anecdotal evidence that suggests young snakes that are exposed to UV retain their colouration better. Many keepers will use a 4 x 2 x 2 vivarium for their Bredl’s pythons, but a 4 x 2 x 4 is far more suitable, especially for active males that like to climb. Even larger enclosures can be used, with naturalistic-looking ledges, robust plants, thick layers of Bio Life Desert and more to create a very striking display viv. This will also give the keeper opportunities to create humid zones and an even greater temperature gradient which is highly beneficial to the species.

Bredl’s pythons broadly have a good feeding response. This makes enrichment feeding methods easier and multiple prey items can be used and swapped around at random, adding important variety to the animals’ diet.

14 AUGUST 2023

Spotlight

Species

NutriRep™ is a complete calcium, vitamin & mineral balancing supplement with D3. It can be dusted onto all food sources including insects, meats & vegetables. No other supplement is required.

with pink or yellow discolouration around the abdomen?

the Tadpole Doctor

Disease in your captive tadpoles?

Have you seen any disease, noticed unusual symptoms, or had unexpected deaths in your tadpoles?

Are your tadpoles bloated – maybe with pink or yellow discolouration around the abdomen?

Have you observed any change in their behaviour, such as: sudden and erratic movements, swimming in circles, loss of equilibrium, sluggishness, floating at the surface or death?

Have you observed any change in their behaviour, such as: sudden and erratic movements, swimming in circles, loss of equilibrium, sluggishness, floating at the surface or death?

Researchers at the University of Oxford need your help. They are trying to track the spread of a newly identified disease of tadpoles. If you suspect that your tadpoles are showing signs of the disease symptoms mentioned above, please make contact at http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk.

Researchers at the University of Oxford need your help. They are trying to track the spread of a newly identified disease of tadpoles.

If you suspect that your tadpoles are showing signs of the disease symptoms mentioned above, please make contact at http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk

http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk

AUGUST 2023 15

The Royal Society and the University of Oxford bear no responsibility for this project.

tadpole-doctor.co.uk The Royal Society and the University of Oxford bear no responsibility for this project.

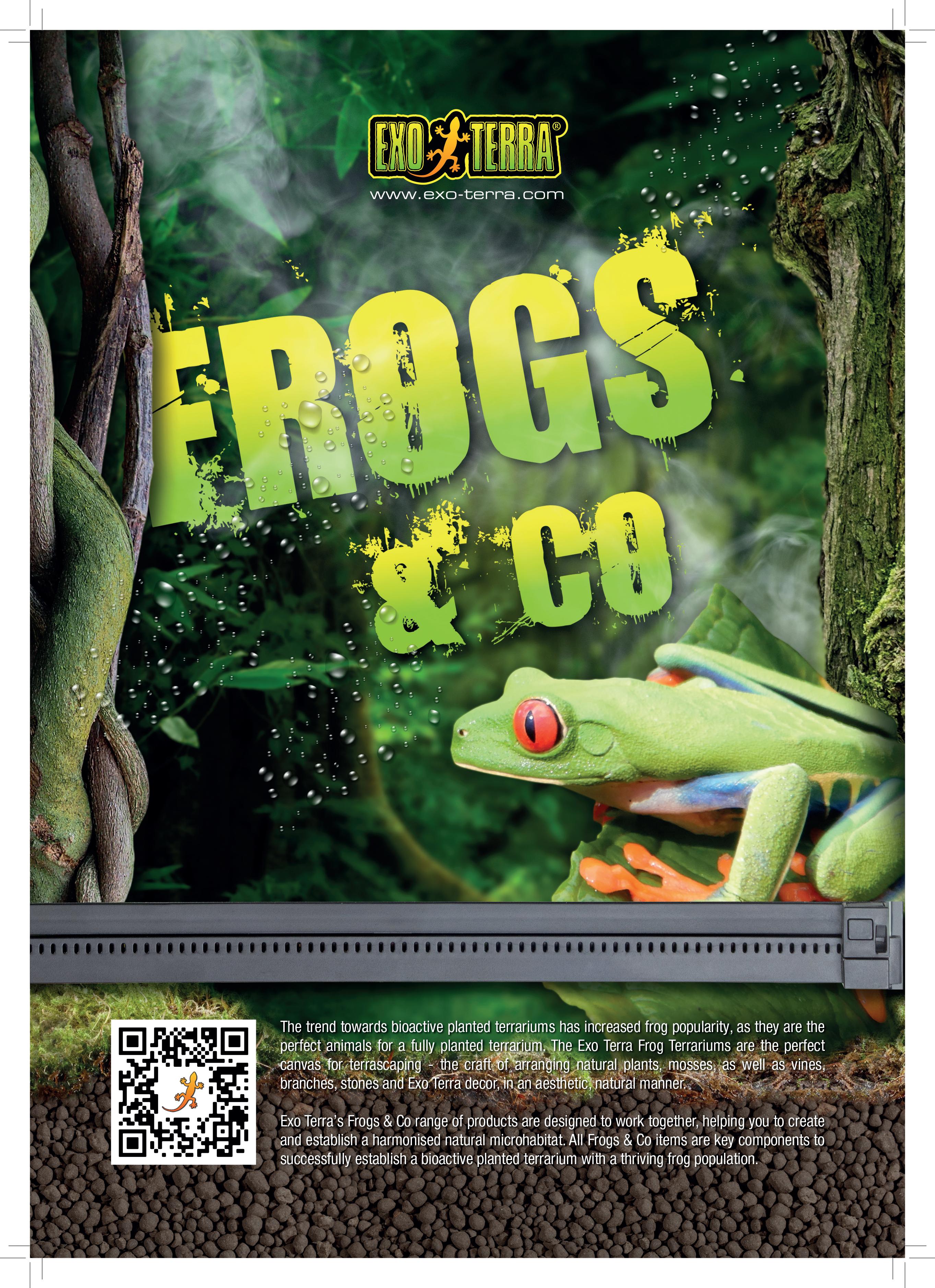

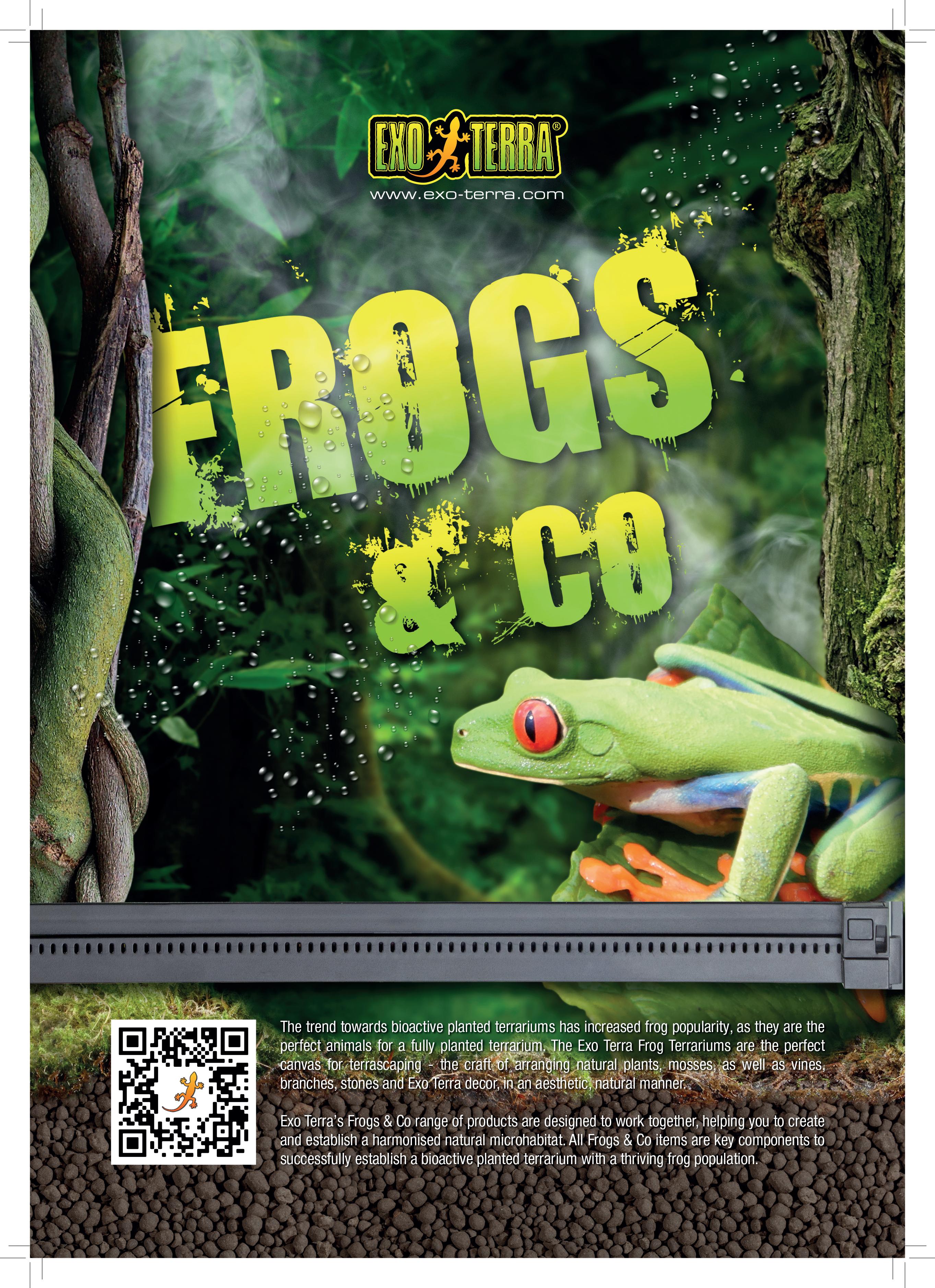

A DIFFERENT KIND OF BOA

Dumeril's boas in the wild and implications for captive care.

The Dumeril’s boa is widely hailed as the best pet boa. Their striking patterns, docile temperaments and manageable size make them the ideal candidate for a pet Boid. As one of two species within the Acrantophis genus, these unique snakes from Madagascar are regularly bred in captivity and have been for some time, but are we keeping them correctly?

Dumeril’s in captivity

Dumeril’s boas were once exported from Madagascar in large numbers and remain very popular in captivity. Averaging at around 6-7 feet in length (although some individuals will exceed this) with reasonably docile temperaments, Dumeril’s boas became an interesting alternative to other large constrictors during the reptilekeeping boom of the 80s.

Dumeril’s boas are now listed under CITES Appendix 1 (Annex A) and have been since 2008. This means that they require an Article 10 certificate to be traded in the UK. Chris Newman, Founder of the National Centre of Reptile Welfare said: “We see Dumeril’s not infrequently

at the centre and they almost never have valid paperwork. Historically, enforcement on this was robust in the UK, however, for the past ten years or so it has been largely ignored as they are so commonly kept and bred that most probably don’t have valid paperwork as they were never chipped. In the EU, they are far more formal about these things but in the UK, you are not legally required to have an A10 for a species you are just keeping as a pet.”

Although the Acrantophis genus has retained its colloquial title of “boa” despite its loose taxanomic connections to New World Boids, their captive care is entirely different to almost all commonly-kept “boas”. Husbandry-wise, Dumeril’s require a setup far more akin to the pythons of

18 AUGUST 2023 A Different Kind of Boa

southern Africa. This is unsurprising given that Dumeril’s boas occupy arid and semi-arid landscapes across southern Madagascar. They are reasonably adaptable and thrive in extremely hot and dry conditions by shielding themselves underground. This behaviour is extremely distinct from even the Dumeril’s closest cousin, the Madagascar ground boa (Acrantophis madagascariensis).

Dumeril’s boas in the wild

On a recent trip to Madagascar, we visited Anja Community Reserve, near Ambalavao in the Haute Matsiatra Region of southern Madagascar to find and photograph Dumeril’s boas. Anja is a small patch of forest,

home to the most Northernly occurring population of ring-tail lemurs (Lemur catta). The local farming community that protects Anja and the tourism brought in by the lemurs, have also indirectly created a small oasis for many species of reptiles. We found several dumerili, but also Nosy Komba ground boas (Sanzinia volontany), water snakes (Thamnosophis sp.) and cat-eyed snakes (Madagascarophis sp.) In our experience, the boas were abundant and the several individuals that we found were all in very good condition. Even in a landscape heavily altered by farming, the snakes appeared to be thriving. Two of the three individuals were found by local farmers in burrows beneath the ground. The surface was typically composed of highly compacted soil. Around the perimeter

19 AUGUST 2023

A Different Kind of Boa

A dumerili basking on the side of the road before dusk ©Thomas Marriott

of the fields, softer soil allowed for some shallow burrows and tall grass provided shelter from the harsh sun. In the evening, we found a large adult (around 7 feet) basking by the side of the road at 5.30 pm, just before dusk.

The individuals we found were extremely docile, despite two of them preparing to slough. We soon gathered a large crowd of local farmers and their children who were understandably confused at a group of westerners gathering around a 7-foot-long snake. There was no animosity towards the animal from the local people who exemplified the (broadly) positive relationships between man and animal in Madagascar. Many tribes across the country believe that once a human dies, their soul is carried by the nearby animals. This is even more important for the Dumeril’s and Madagascar ground boas whose patterns are said to portray the faces of people who have perished and whose souls are now carried by the snakes. Both species of Acrantophis are highly variable, so it is easy to see how these tales have resonated through generations.

In the wild, Dumeril’s boas are at the top of the food chain. In our experience, the most abundant medium-sized lizards were Grandidier’s rock swifts (Oplurus grandidieri) and girdled lizards (Zonosaurus madagascariensis). Mynah birds (Sturnidae), little egrets (Egretta garzeta) and several species of bat are found nearby and as the reserve also has the highest density of ring-tailed lemurs in the region, one may assume that the Dumeril’s boas would predate on

the occasional juvenile lemur.

The reptiles of Madagascar have not evolved to fear large predators. Juveniles may be exposed to birds of prey and some populations may also be predated upon by carnivorous mammals, but once the Dumeril’s boa reaches adult size their only threats are traffic and livestock. The IUCN reports that Dumeril’s boa population numbers are stable, which is a rare phenomenon for Malagasy herpetofauna. This provides some evidence of their adaptability and is a good indicator of their care requirements.

Keeping Dumeril’s boas

Dumeril’s boas can vary drastically in size, so keepers should always aim to provide as large an enclosure as possible. An average-sized snake will reach around five feet and so a 4 X 2 X 2 wooden vivarium would meet all current enclosure size regulations. However, some individuals can reach up to nine feet in length and therefore quickly outgrow even the largest commercial vivarium. This is certainly something that all Dumeril’s boa keepers should consider when planning their set-up. If the keeper is hoping to house the animal into adulthood, additional electricals may be required to enlarge the basking spot, décor may need to be fixed with screws and more robust hides should be used. Therefore, even though Dumeril’s boas are often a manageable size and generally have great temperaments, the prospective keeper should

20 AUGUST 2023 A Different Kind of Boa

Author and EK Editor, Thomas Marriott with a wild adult Dumeril’s boa

An adult Dumeril's boa above her burrow ©Thomas Marriott

be prepared to keep a large constrictor.

Many people confuse Dumeril’s boas with Madagascar ground boas. Although they are closely related, their husbandry requirements are different. Madagascar ground boas occupy forest floors in semi-tropical regions and will often climb trees and occupy humid caverns in tree trunks. They move through thick layers of leaf litter and occupy microclimates of reasonably high humidity in North Madagascar. However, in southwestern Madagascar, the soil quality is poor with a high proportion of sand. Dumeril’s boas occupy the burrows of other animals amongst this compacted, nutrient-poor soil to escape harsh, dry conditions. In captivity, the substrate should reflect this. ProRep’s BioLife Desert and BeardieLife are perhaps the closest commercially available mimics of this soil. However, ideally, the enclosure should be split into two. The “hot” half should host the basking spot (of around 32°C) with a desert substrate and plenty of rocks and stones, while the “cool” half should have a malleable substrate (with a greater ratio of soil, coco chips and leaf litter) for the snake to bury into.

Dumeril’s boas are primarily nocturnal, although they will bask in the early evening. As such, they have low UVB requirements despite occupying regions with intense daytime sunlight. A Zone 2 HO-T5 positioned the length

of the enclosure should provide a broad radiance of UV for the snake to absorb. Although dumerili occupy arid regions, they are also at home on high plateaus and thus benefit from an occasional gentle spike in humidity. Morning misting can provide this spike and support the snake during shedding.

Handling and feeding

The Dumeril’s boa is typically a very docile snake. Like many animals in Madagascar, it has not evolved a particularly defensive demeanour as there are no “large” predators in Madagascar and very few medium-sized ones too. This means that although some birds of prey could potentially attack a young snake, even wild dumerili are not likely to strike at a person. However, despite being evolutionary distinct from New World boas, Dumeril’s boas have an equally enthusiastic feeding response in captivity. There are a few techniques that can be used to prevent a bite, such as tactile training methods (touching the snake before handling to establish that it is not dinner time), washing hands thoroughly and not interfering with a feeding routine. This means that although Dumeril’s boas are well suited to captivity when cared for appropriately, they should still only be kept by confident keepers who will be resilient, should the snake become temperamental or grow larger than expected.

21 AUGUST 2023 A Different Kind of Boa

The local community watching the team take photographs of the Dumeril’s boas ©Thomas Marriott

Pinkies 1g+ | Pinkies 1g+ | Pinkies 1g+ | Large Pinkies 2g+ | 10 Pack Large Pinkies 2g+ | Large Pinkies 2g+ Fuzzies 4g+ | Fuzzies 4g+ | Fuzzies 4g+ | Hoppers 6g+ | Small 10g+ | Small/Medium 15g+ | Medium 19g+ Medium/Large 23g+ | Large 26g+ | Extra Large 30g+ Ex-Breeder 35g+ | Ex-Breeder 40g+ Rat Pups 4g+ | Fuzzies 12g+ | Hoppers Small 20g+ | Weaner Small 30g+ | Weaner Medium 50g+ Weaner Large 70g+ | Small 100g+ | Small/Medium 130g+ | Medium 160g+ | Medium/Large 200g+ | Large 250g+ Extra Large 300g+ | Jumbo 350g+ 5 pack | Ex-Breeder 400g+ | Ex-Breeder 450g | Ex-Breeder 500g

TERRIFIC TARANTULAS AND HOW TO KEEP THEM

By Dr Michaela Betts and Dr Benjamin Kennedy

By Dr Michaela Betts and Dr Benjamin Kennedy

Tarantulas belong to the Theraphosidae family, and there are over 1,060 species spread over 116 genera, with over 250 being kept in the pet trade internationally. Males live for 5-7 years in most instances, whereas females can live for up to 30 years with the oldest tarantula recorded living to 43 years (and this one died due to parasitism rather than old age). Whilst frequently seen as part of zoological collections, keeping tarantulas as pets has been becoming more popular in recent years.

New World and Old World species

Tarantulas can be broadly separated into Old and New World species, with new world tarantula species being natively found in North, South, and Central America. These species tend to be more docile than their Old World counterparts, and their envenomation is comparable to a bee sting. These species have more ‘urticating’ hairs that they can flick into the environment or at a predator as a defence mechanism. Some people can have a severe response to these hairs and it is a big concern if they are flicking to eyes as they can be extremely fine and require specialist care (potentially surgery) to remove them. For this reason, the use of gloves and goggles during handling and rehousing to avoid these hairs is advisable.

Old World tarantula species originate from Asia, Africa, Australia, and Europe. Comparably these tarantulas are

less hairy, may stridulate if provoked, and are anecdotally more aggressive. Bites from Old World tarantulas can cause intense pain, and in some species may cause spastic contractions of the muscle where bitten as well as local tissue necrosis.

Important anatomy & physiology

Tarantulas have four pairs of legs, which are attached to the prosoma (equivalent to a fused head and chest). They have one pair of pedipalps (these play a sensory and manipulation role in prey capture as well as in reproduction in males), and one pair of chelicerae (which contain the fangs and venom glands and are used for grasping and envenomating prey). Bulbous pedipalps

24 AUGUST 2023 Terrific Tarantulas and How to Keep Them

About the author: Benjamin is currently practising in the midlands as a small animal and exotic vet. He has an interest in Invertebrate medicine and researches the application of clinical techniques and expertise in these species. Through this, he has a growing caseload of invertebrates from zoological, private, and commercial collections. In addition to his veterinary medicine degree, Benjamin has a Bachelor's in Biochemistry and Genetics and a Master's in Molecular Biology and Pathology of Viruses. Benjamin is involved in multiple societies, including the steering committee of the Veterinary Invertebrate Society and the council of the British Veterinary Zoological Society. He is the co-editor of the Veterinary Invertebrate Society Journal. He is also a member of the Royal Entomological Society and the British Tarantula Society. Benjamin regularly publishes articles and presents his research at conferences to raise awareness of invertebrate medicine.

and tibial spurs may be apparent in the males of some species.

The prosoma contains the oesophagus, sucking stomach, central nervous system and attachment muscles for controlling the limbs. The opisthosoma is separated from the prosoma by a narrow pedicle and is the equivalent of the abdomen. The book lungs (covered by two hardened abdominal plates), heart, hepatopancreas, excretory organs, and reproductive organs are located within the opisthosoma. On either side of the anus are two pairs of spinnerets that are responsible for the formation of multistrand silk filaments for web creation.

One could describe the spider circulatory system as “semi-closed”.

About the author: Michaela is an exotic animal veterinarian who graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 2018. After working in increasingly exotic animal practices and volunteering at a wildlife hospital, she joined Suffolk Exotic Vets in 2021 where she works with an array of avian, reptile, small mammal, amphibian, and aquatic species. Alongside her clinical work, Michaela is an educational speaker for Just Exotics, providing further education to veterinary professionals on exotic animal species, and is involved with the British Veterinary Zoological Society and Association of Exotic Mammal Veterinarians. She is currently completing her RCVS Certificate of Advanced Practitioner in Zoological Medicine.

The spider heart has an open venous circulatory system, meaning they do not have “true” veins for the transport of blood in the same manner as vertebrates, but they do have vessels that flow into the prosoma and then into the limbs. These are involved in maintaining hydrostatic pressure. The return of haemolymph to the heart is through a pressure gradient. Flexion of spider limbs (i.e. outward movement) is through muscular action and extension (i.e. inward movement) relies on haemolymph pressure.

Theraphosids have a rigid outer cuticle made up of the epicuticle, exocuticle, and endocuticle. The exocuticle is primarily made of rigid chitin to help form a protective outer layer. The epicuticle is important in restricting water

loss and helps to also form the tough outer layer. Cuticle is best considered as spider skin rather than as a shell and has sensory receptors on the epicuticle. The rigid exoskeleton of spiders is also moulted for them to grow. It is a process that typically lasts for several hours, and venom ducts, book lungs, oesophagus and openings to the gonads are some of the major structures that shed.

Spiders can autotomise and regenerate legs and pedipalps and spinnerets. It is a voluntary defensive adaptation of the spider where it sacrifices the appendage to escape a perceived threat such as being predated. Legs will return to normal size within the preceding moults. Generally, the larger (and older) the spider, then the more moults are needed for the leg to fully regenerate.

25 AUGUST 2023 Terrific Tarantulas and How to Keep Them

The anorexic spider

Anorexia is a common complaint of captive tarantula species, particularly by novice keepers. However, in the absence of other clinical signs, “normal” behaviour should be ruled out and the set-up reviewed, particularly with inappropriate heat and humidity. The condition of the spider should be considered as a large overweight spider will be more likely to become anorexic. Condition in spiders is best determined by considering the ratio of size between the opisthosoma and prosoma.

Anorexia for weeks or months may be associated with the period preceding or following a moult. This occurs because the oesophagus is also moulted thus it isn’t a matter of the spider not wanting to eat but being unable to take food.

Male tarantulas who have emerged from their terminal moult may become anorexic in favour of trying to escape and find females with which to breed. It’s important to remember that adult male theraphosids only live for a limited time (typically 6-18 months) after their terminal ecdysis. Male tarantulas have enlarged palpal

organs, and some species will also have hooked tibial spurs on their first pair of legs when emerging from their terminal moult. Conversely, female tarantulas may undergo a period of anorexia before producing an egg sac.

Common environmental conditions

As with all exotic species, appropriate husbandry is paramount to the health and well-being of the individual animal. Suboptimal environmental conditions can predispose tarantulas to medical and/or surgical conditions, some main offenders being: dehydration, trauma, and alopecia (loss of hair).

Signs that a tarantula is unwell may be visibly obvious or could be more subtle such as reluctance to move, abnormal posture, or anorexia. The latter is more difficult to determine given that some species will not eat for 6-12 months, and the Chilean Rose tarantula and Mexican Blonde tarantula have both been reported to sometimes go for prolonged periods without eating without a known cause.

Underlying reasons for lethargy and

similar changes can also include infectious causes, parasites, and ageing. Parasiticide and pesticide toxicities should be considered carefully, especially for anti-flea products used on other animals in the house (such as cats and dogs). Spiders should not be handled with the same hands that have earlier stroked a mammal treated with an anti-parasite treatment. Treatment of intoxication is not often successful and so prevention is important in these cases.

Alopecia

Hair loss over the dorsocaudal parts of the opisthosoma may be seen in our New World tarantula species due to the urticating hairs being kicked off in response to a perceived threat or prolonged exposure to vibration. These hairs are replaced at the next moult but will not regrow before this, leaving the pale cuticle exposed. Recurrent defensive displays are indicative of environmental and/or handling stressors, so a full review of their set-up and their handling should be undertaken to identify what is triggering this defensive mechanism. This review should also include factors outside of their enclosure that may still

26 AUGUST 2023 Terrific Tarantulas and How to Keep Them

Example of pre moult alopecia in Brachypelma hamorii tarantula ©Benjamin Kennedy

have an impact, such as vibrations from speaker systems, the presence of predatory species in the vicinity, and banging on the glass.

This alopecia should not be confused with the normal alopecia of some tarantulas about to undergo a moult. In these cases, the cuticle tends to appear dark in colour and the opisthosoma has a full-looking appearance.

Dehydration

Most water is taken orally from the food source, but water should always be available in a shallow dish. Despite this, dehydration is a common presentation of our captive tarantulas. Theraphosids may also arrive to new keepers dehydrated if there have been postal transport delays (especially in warmer weather)

In some cases, the signs of dehydration might be more evident as deficits in movement or posture. This is due to the limb movement being dependent on hydrostatic pressure. In severe cases, dehydrated individuals may also have distortion or “shrinking” of their opisthosoma, the prognosis for these is poor.

Theraphosids who are responsive and able to move can be rehydrated by placing the cranial edge of their prosoma in a shallow water dish, taking great care not to submerge the underside of their opisthosoma and by extension their book lungs. Alternatively, some spiders

may take water offered to them from a syringe with a soft cannula tip attached. These spiders will usually rehydrate within a few hours and may benefit from being kept in a warm humid set-up for 24 hours in the meantime, less if improving sooner.

Tarantulas are unable to access nor ingest oral fluids and will need to have injectable fluid therapy either into one of the joint membranes or into the heart directly. For these cases, a spider-savvy vet or nurse should be sought for these to be safely administered. The Veterinary Administration by these routes is not without risk.

Trauma

Trauma can occur for many reasons, from damage from bites from a feeder, to fall damage to limbs being damaged by decor. Death can occur rapidly from exsanguination (severe haemolymph loss) and so any ongoing drainage of haemolymph is an emergency. Some spiders will lose haemolymph gradually over several days and present as more lethargic perhaps with movement and postural deficits.

Substrates will often rapidly absorb haemolymph and so it can be difficult to identify. Placing the tarantula in question onto a paper towel substrate for 24-48 hours can facilitate monitoring for continued leakage of haemolymph.

Wounds at the base of limbs or over the upper part of the

27 AUGUST 2023

Severely dehydrated Poecliothera metallica ©Benjamin Kennedy

opisthosoma are likely to exsanguinate faster and so need to be identified as soon as possible. Post-mating injuries to the prosoma, though rare, have a poor prognosis and thus immediate veterinary care should be sought in these cases. Appropriate cessation of any bleeding needs to be carried out. Fluid therapy may also be required depending on the amount of haemolymph loss.

Keepers are also recommended to not interfere through direct pulling of the old cuticle during moulting as this is a common cause of fatal trauma. The underlying new cuticle is soft to enable body expansion and will not be as strong as the old cuticle being shed until up to 20 days after moulting. Consequently, any tension can result in a new cuticle tearing leading to catastrophic trauma. If a spider is trapped in a moult then manually extracting it should be the absolute last resort.

Housing

Tarantulas in the wild tend to be solitary animals and thus should be housed individually to avoid cannibalism. The exact design and size of an enclosure varies depending on the individual species, and keepers should be aware of these differences to provide a suitable environment.

Any holes for ventilation need to be smaller than the individual’s prosoma to prevent escape, and ideally smaller than the diameter of any legs to reduce the chances of any trapped legs. Wire mesh vivarium covers

should similarly be avoided as spider toes can become trapped. Regular assessment of each spider and its environment is important as dehydration and/or anorexia can lead to a reduction in opisthosoma size and allow theraphosids to escape from previously appropriate enclosures.

Substrates should be tailored to the species, considering any need for burrowing behaviours. Horticultural vermiculite, coconut coir, peat, potting soil, oven-heated topsoil, and a combination of these are viable options for different tarantula species. Substrates should be free of pesticides and potential parasites, so topsoil and horticultural substrates should be avoided. Vermiculite dries out more quickly than other substrates so should be avoided for high humidity set-ups. It also does not provide good footing for breeding, nor maintain burrows well, so should be avoided for these spiders. Similarly, coconut coir does not easily retain its shape so is not preferred for burrowing species. Peat is particularly useful for burrowing and for high-humidity species but can be difficult to obtain ethically.

Ideal temperature gradients vary between species, with Chilean Rose preferring 18C-24C and Cobalt Blue preferring 26C-32C, so the thermal gradient should be adjusted for the species being kept. A maximum-minimum thermometer is recommended for close monitoring. Most tarantulas are photophobic (have an aversion to light), and vivaria should be kept out of direct sunlight and bright

28 AUGUST 2023

lights. External heat sources should not emit light so heat mats and ceramic heat emitters are viable options, though care should be taken to heat the side of the enclosure and not the bottom. Relative humidity also varies between species, with the Chilea Rose preferring 60% and the Cobalt Blue preferring 85-90%. Tarantulas should not be sprayed directly as it causes frustration and stress. Ideally, the side of the enclosure should be sprayed so it can evaporate into the air. All species should be offered water in a shallow dish, with water-soaked sponges being avoided due to the risk of bacterial and fungal contamination.

Arboreal species require taller enclosures, ideally with doors on the front and top of the set-up. They require some shallow substrate to help maintain humidity and plenty of opportunity to maintain a vertical resting position with appropriate climbing and hiding enrichment such as cork or pieces of wood. Terrestrial species may be obligate or opportunistic burrowers so should be provided with deep enough substrate to exhibit burrowing behaviour. Brachypelma vegans, for instance, have been known to burrow as deep as 1.2 metres, so the conventional advice of "6 inches" is often a gross underestimation of the required substrate. Half of a dark-coloured plant pot or plumbing plastic tubing are good examples of appropriate and easy-to-clean hides. The substrate mix should be able to support its weight to avoid the tarantula being buried (though some species have been known to bury themselves into the substrate).

Height of enclosure is an important consideration, especially for conventional species, as trauma and even death can be a result of inappropriately tall cage height. Similarly, the inclusion of sharp rocks or plants such as cacti should be avoided as enrichment items due to the risk of opisthosoma trauma.

Insecticides should never be used in enclosures. It may be better to avoid enclosures that have previously housed animals that have been treated with anti-parasitic medications to avoid any potential exposure.

Diet

"We are what we eat” is as true to spiders as it is to any other animal. Feeder invertebrates should be kept well and thus be of high nutritional value to any feeding animal (regardless of whether this is a tarantula, reptile, bird or mammal). Gut loading is often considered as being a replacement for feeding prey invertebrates, but we should consider that tarantulas are primarily carnivores and thus will be ill-adapted to absorb vegetative material (which is why we don’t see many plant-eating tarantulas). When feeder invertebrates are brought, they should be transferred to a separate enclosure and given a high-quality diet and kept at appropriate husbandry conditions so these feeders will put on condition and provide a good source of macro and micro vitamins. Overfeeding, particularly to promote more rapid growth in spiderlings, should be avoided as it predisposes to obesity and consequent trauma of the opisthosoma.

Feeding a variety of prey species may help to optimise amino acid proportions in the diet and provide more balanced nutrition. Invertebrates such as crickets, locusts, dubia roaches, mealworms, and fruit flies are all commonly reported as feeder insects. Wax worms should be used sparingly due to their high fat content. It is important to tailor the feeders to the natural behaviour of the tarantula in the wild, for example, an arboreal species may appropriately take flying prey. This factors both into the nutritional and enrichment value of prey. Mantids should never be offered as there is a risk of them overpowering and consuming a captive spider themselves.

Invertebrate cuticle contains calcium and zinc, though in different proportions to vertebrate bone, so some level of supplementation would be recommended though this is best achieved by giving vitamin supplementation (via a multicompetent supplement, not a sole calcium supplement) to prey populations over an extended period (i.e. not gut loaded). Excessive supplementation should be avoided.

Some larger species may accept whole, killed vertebrates and mammalian meat such as ox hearts. However, these will often take extended periods to be consumed and have a high fat and protein content compared to invertebrate species but may be appropriate for carrion feeders but should be used sparingly and not represent most of the diet.

Conclusion

Despite their increasing popularity and history of being kept in collections, there is still a lack of research and published literature on health conditions and the appropriate care of invertebrate species for both keepers and veterinary professionals. The Veterinary Invertebrate Society or an exotic vet with an active interest in tarantula medicine can be helpful sources of information on what can be done for tarantulas that are unwell.

AUGUST 2023 29

to

Terrific Tarantulas and How

Keep Them

DRAGONS OF THE INFERNAL REALM:

An Introduction to the Texas alligator lizard.

by Roy Arthur Blodgett

by Roy Arthur Blodgett

Deep within the limestone cuts and canyons of the Texas hill country - slinking among the live oak, ball moss, and maidenhair fern - dwells one of North America’s most charismatic Saurians:

the Texas alligator lizard (Gerrhonotus infernalis). In the vivarium, they make for one of the best pet lizards one could ask for, but before diving into the specifics of their husbandry, let’s begin with a basic outline of their natural history.

Natural history

Largely considered the largest of the alligator lizards, infernalis is an impressive lizard in the family Anguidae, attaining lengths of up to two feet (60cm), a metric that sets them distinctly apart from their smaller relatives in the genus Elgaria. Though largely distributed through central and eastern Mexico, from Chihuahua in the north, south to Hidalgo, their range also extends into south-central Texas, primarily across the Edwards Plateau and Balcones Escarpment, where they are strongly associated with the oak woodlands and limestone canyons of the Hill Country.

Texas alligator lizards are diurnal, and though often classified as terrestrial, they are far more arboreal in habit

than their cousins in the genus Elgaria, readily climbing shrubs, trees, and rock faces with regularity, while making good use of their powerful, semi-prehensile tails. In Texas, they’re most commonly observed within limestone crevices or vegetation in riparian canyons or woodland habitats, but in some areas they are known to occupy more open, rocky slopes and adjacent areas. They are highly insectivorous, employing an active hunting strategy, foraging through leaf litter, and preying upon a variety of insects and arthropods. Their dietary preferences are largely indiscriminate, including but not limited to katydids, mantids, phasmids, grasshoppers, spiders, and caterpillars. It is also presumed they will raid the occasional rodent or songbird nest.

32 AUGUST 2023

Dragons of the Infernal Realm

Dragons of the Infernal Realm

Acknowledgements: I would be remiss not to extend special gratitude to Justin Munsterman, Connor Wardle, Chad Lane, Dustin Grahn, and Armen Keuylian, whose insights and enthusiasm for Gerrhonotus, among other alligator lizards, have contributed greatly to my experience keeping these lizards.

Author’s Bio:

Roy Arthur Blodgett is the sole proprietor of Wellspring Herpetoculture, and keeps an eclectic array of New World reptiles and amphibians with a focus on naturalistic, biotope husbandry. He is passionate about the value of herpetoculture in our rapidly changing world, and his background as a naturalist and ecological educator strongly informs his practice. He is constantly striving to progress his husbandry and encourage a broader range of natural behaviours in the animals in his care. He also co-hosts the Project: Herpetoculture Podcast, which features long-form discussions exploring the art, practice, and discipline of keeping reptiles and amphibians.

Sexual dimorphism is expressed in Texas alligator lizards through several obvious characteristics. Males tend to attain a larger overall size, with much larger and broader heads. Females are more slightly built, with larger and longer abdomens relative to the size of their heads. Males also have a pronounced hemipenal bulge at the vent, especially evident in comparison to females when held side by side. In terms of reproduction, most sources cite that mating occurs in the fall. Copulation usually occurs in a terrestrial setting, with the male grasping the base of the female’s neck with his mouth. An oviparous species, the Texas alligator lizard usually lays an annual clutch averaging from ten to twenty eggs. Larger clutches are not uncommon, especially in large, well-conditioned females of the species.

Gerrhonotus infernalis is currently listed as ‘Least Concern’ by the IUCN. That said, there is no mistaking that much of their range and habitat has been significantly impacted by human development. Because most of their native habitat falls within the borders of private landholdings, their longterm well-being is worthy of weighty consideration.

Housing

Given their relatively sedate behaviour and modest size, Texas alligator lizards are quite reasonable to satisfy in terms of vivarium dimensions, especially in comparison to more active species of similar size, such as dwarf monitors (which require very large vivaria, given their hyperactive behaviour). In my case, I have usually housed oppositesexed pairs in vivaria measuring approximately 3 feet long by 2 feet deep by 2 feet tall (~90cm by 60cm by 60cm), which, when well provisioned with complex decor and climbing opportunities, provides sufficient space and opportunity for movement. However, larger vivariums, whenever possible, are preferred. Gerrhonotus will make full use of the space offered to them.

As is always the case, the keeper’s climate and reptile room conditions will bear the greatest influence on choosing the most suitable material for the vivarium itself. Living in a Mediterranean climate in central California and having a reptile room that is difficult to reliably regulate year-round, I typically use PVC habitats with acrylic or sliding glass doors, which have the benefit of retaining

33 AUGUST 2023

One of the author's neonate Texas alligator lizards©Roy Arthur Blodgett

HIGH QUALITY HAUTE QUALITÉ SHINYBLACK CABINE T

250 / 370 / 570 / 720 L

With over 50 years of service to reef aquariums, it is the pleasure of AQUARIUM S YSTEMS t o share the level of passion we have had since the beginning: L’AQUARIUM 2.0.

With L’AQUARIUM, you can start a reef system quite simply and w ithout any stress regardless of your l evel of expertise. Let us guide you, and welcome to the world of L’AQUARIUM 2.0.

ADJUSTABLEFEET

AUGUST 2023 250

370 570 720

some heat and humidity to provide a more stable environment within the vivarium. For those who live in more stable climates, or who can reliably regulate temperature and humidity on the full room scale, a broad array of options might be utilized, such as glass, wood, or even screen.

To furnish the vivarium, I provide a faux rock background to maximize usable surface area and outfit the space with branches throughout to allow for climbing and basking at varying temperatures and ultraviolet levels. The substrate is a deep mix of decomposed granite, play sand, and topsoil or peat moss, topped with a generous layer of leaf litter to encourage burrowing and foraging behaviour. Live plants, such as agaves, grasses, tillandsias, or maidenhair ferns provide cover and offer valuable enrichment and stimulation. Lastly, I include a few slabs of bark or slate, beneath which the lizards can find refuge, as desired.

Climate control and replication

Subject to a northern latitude, the region where Gerrhonotus infernalis natively occurs expresses significant fluctuation in daylight, temperature, and precipitation throughout the calendar year. The daylight cycle peaks in late June with a roughly 14-hour day, descending to a trough of 10 hours of daylight in late December. Temperatures follow a similar arc, peaking with average temperatures of 34-36°C in late summer, and descending to average daytime temperatures of 16-21°C. Nighttime temperatures average around 21°C during the summer and reach annual lows of 5°C during the winter. There are also significant seasonal rhythms expressed in precipitation, with a pronounced wetter season during the summer, punctuated by a dry winter. Replicating these factors of photoperiod, average

temperature, and precipitation within the vivarium is essential to the longterm well-being and propagation of Texas alligator lizards.

To meet the appropriate provisions of visible light, ultraviolet radiation, and infrared radiation, I utilize three types of lighting in my Texas alligator lizard vivaria. Standard PAR38 or PAR30 halogen bulbs heat the vivariums to average ambient temperatures of 25-29°C while providing a localized basking area exceeding 38°C. Halogens are particularly adept in emitting near-infrared radiation, allowing the lizards to thermoregulate efficiently as they would in nature. Linear high-output T5 bulbs are provided for ultraviolet A+B radiation, creating a gradient of UVI values ranging from 0 to 3.0 throughout the vivarium. Choosing the right bulb and UV output is dually dependent on the distance of the bulb from the basking area and the specific bulb’s UV output

35 AUGUST 2023

The author's adult pair of Texas alligator lizards - note the broader head of the male on the right. ©Roy Arthur Blodgett

percentage, and as such can vary widely, and the keeper must determine the appropriate bulb based on these factors. For visible light, I utilize linear LEDs (~6000K), which flood the enclosures with rich, bright light capable of supporting live plants. In concert, these three types of lighting provide a broad spectrum and a sufficient (if admittedly shoddy) replication of natural sunlight for the needs of the lizards. Furthermore, when sequenced correctly with the use of timers, one can roughly simulate the sun’s light as it rises, peaks, and sets across the day and fluctuates throughout the seasons.

To simulate the onset of the monsoon rains of late summer, I regularly mist the vivarium during the summer monthsperhaps three to four times per week. For this task, hand misting with a pump sprayer, or utilizing an automatic misting system, is equally appropriate. In the drier seasons, I continue to provide a shallow water bowl, which I overfill regularly to provide a moisture gradient within the substrate. Occasionally I observe the lizards drinking from their bowls, but it is an admittedly rare occurrence, suggesting to me that the majority of their hydration needs are met by the moisture content of their prey, and the provision of humid refugia to avoid desiccation.

Diet and supplementation

Gerrhonotus are capable predators of a wide array of insects, arthropods, and small vertebrates, employing an active foraging strategy to find prey, which they slowly stalk until within striking range. Once close, the lizards curve their forebodies into an S-shape and lunge with startling precision to capture their quarry within their powerful jaws. Just before lunging, it is not uncommon for them to twitch their tails in a cat-like manner, perhaps as a distraction to confuse their prey.

In the vivarium, crickets, roaches, grasshoppers, phasmids, katydids, mantids, caterpillars, spiders, flies, fly larvae, and beetle larvae are all accepted prey. Given their relatively sedate hunting strategy and slow metabolisms in comparison to more active species, Texas alligator lizards also respond very well to tong feeding. They are strongly food-motivated, and I have found that encouraging the lizards to pursue their prey on the tongs is a good way to encourage exercise and familiarize the lizards with their keeper. Mine readily recognize the food cup and greedily approach the vivarium door upon my approach, showing no fear of me whatsoever and willingly climbing out onto my hand or arm in pursuit of an insect on the tongs!

36 AUGUST 2023

In terms of supplementation, I utilize high-quality multivitamin and calcium products formulated for reptiles to dust feeder insects. My rotation is usually two to three feedings of insects dusted with multivitamins, followed by one dusted with calcium, repeating the rotation and remaining attentive to any need for adjustment. Reproductively active females should be offered additional calcium to ensure they have sufficient resources for egg production. As with all of the lizards in my care, the Gerrhonotus are kept under high-quality UV-producing bulbs, and as such I avoid supplements with added D3 to avoid the possibility of hypervitaminosis.

Breeding

As far as I have observed, Texas alligator lizards have been inconsistently bred and are poorly represented in herpetoculture, at least in recent years. This is likely due in part to their relative rarity within the practice, alongside the generally lacking commercial demand for the species. That said, I feel that they show remarkable appeal and consider them worthy of more dedication in herpetocultureespecially given their resilience, beauty, and fecundity.

As of this writing, I have only attempted one pairing of infernalis, after raising my adults from neonates Though I never observed copulation, I suspect it occurred in the fall, after my late summer attempts to simulate the monsoon rains with greater misting frequency, as well as much more frequent offering of food (~3-4 feedings per week). Like many species subject to seasonal scarcity, I believe that the species is triggered to breed by a combination of heavy precipitation, change in temperature, and resource abundance. That said, only a combination of continued refinement and consistent success over time will clarify the

exact factors which reliably elicit courtship behaviour and breeding in this species.

Over the early winter, the female’s abdomen began to noticeably swell, and on January 19th she laid an impressive first clutch of 28 eggs beneath the water bowl - where the substrate was cool and moist. Having heard from the great herpetologist, Harry Greene, that female Gerrhonotus are known to guard their eggs, I gently removed the water bowl and was not surprised when met with a hissing and protective mother who began lunging at me with mouth agape. Though tempted to leave the eggs with the female, given her impressive display and clear commitment to her eggs, I ultimately decided to remove them for placing in the incubator, where I expected the more stable temperatures and humidity might result in a better hatching outcome.

All 28 eggs were placed in simple incubation containers, which featured ventilated plastic trays elevated over moist, fired clay substrate. I also added a layer of wrung sphagnum moss on top of the eggs to help maintain humidity. I set the incubator to 80 degrees F (26.6 C) with a night drop to 78.5 degrees F (25.8 C), anticipating an incubation period of anywhere between 50-70 days and left the eggs to hatch. Disappointingly, over the following weeks, the majority of the eggs failed, perhaps due to excessive moisture and higher-than-optimal temperatures. In later correspondence with another keeper who has been successful in hatching infernalis, Laurence Paul, I was informed that the eggs consistently hatch very well at lower overall temperatures than those I employed. Regardless, after 48 days the first neonates began to pip, and by the 50th day, nine hatchlings had successfully emerged from their eggs.

37 AUGUST 2023

Texas alligator lizard and her eggs.©Roy Arthur Blodgett

Rearing of neonates