ISLAND HOPPING

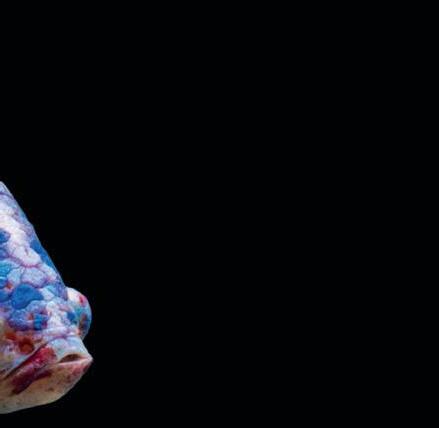

The strawberry poison frog localities of Bocas del Toro

GUATEMALA’S DRAGONS

The captive breeding and re-introduction of Abronia (arboreal alligator lizards) to Guatemala’s cloud forests.

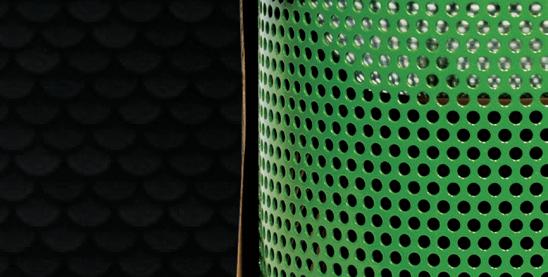

SNAKE DERMATOLOGY

Skin complaints are one of the most common reasons captive reptiles present to veterinary practice and snakes are no exception to this.

ON THE SH(ELL)DERS OF GIANTS

Keepers at Crocodiles of the World tell us how they successfully captive-bred Galapagos giant tortoises for the first time in a UK zoo.

www.exoticskeeper.com • october 2023 • £3.99 EXOTICS NEWS • SAND BOA • KEEPER BASICS • ISLAND GIGANTISM • CAMEROON DWARF GECKO

CONTACT US

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS

thomas@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING

advertising@exoticskeeper.com

About us

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY

Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex

CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4706

Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

Dr Michaela Betts

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather

Subscriptions

Follow us

In this issue, we have a whole bunch of interesting articles designed to improve keeping and broaden knowledge. From veterinary advice for snake keepers to a holistic look at the conservation and illegal trade of Abronia, this issue covers a wide range of topics. We also continue our conversation from last month with Jamie Gilks at Crocodiles of the World to discuss another oddly sized reptile, the Galapagos giant tortoise (be sure to check out last month’s dwarf crocodile article, if you haven’t read it already!)

In other news, I’d like to introduce readers to our latest sponsor, Blue River Diets. These crested gecko foods are set to take the reptilekeeping industry by storm. The brand was very well received at the IHS Breeders Show last month and should be available in stores now. I’ve had the chance to get hands-on with the formulas and they smell fantastic. So, if you’re a crestie, leachie, gargoyle or day gecko keeper, check them out!

There are a lot of components needed to ensure a magazine’s

is the industry behind us that makes this possible. If you are a passionate hobbyist, a budding photographer, a proud student, or a small business looking to feature in EK, please do get in touch.

Thank you.

Thomas Marriott Editor

Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

Front cover: Strawberry poison frog (Oophaga pumilio)

Right: Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis niger)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

02 06 24

02 EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

06 ON THE SH(ELL)DERS OF GIANTS

Breeding Galapagos giant tortoises.

32 42 51

16

FLASHBACK FEATURE: MORE THAN A BOX OF SAND Busting the many myths of sand boa husbandry.

24 THE LAST OF GUATEMALA’S DRAGONS

42ISLAND HOPPING

The strawberry poison frog localities of Bocas del Toro.

51 KEEPER BASICS: Humidity.

14 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s the Cameroon dwarf gecko (Lygodactylus conraui).

The captive breeding and re-introduction of Abronia to Guatemala’s cloud forests.

32SOME ISSUES ARE MORE THAN SKIN DEEP

By Dr Michaela Betts

58 FASCINATING FACT Did you know...?

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic animals

The environments favoured by the bleached sandhill skippers have been devastated by animal grazing, water diversions and climate change, with the blue monitor lizard similarly threatened by climate change and disease.

New venomous snake found in Australia

A new venomous snake, previously thought to be another species, has been found in Australia.

The desert whip snake (Demansia cyanochasma) is found across Australia, dwelling in dry habitats. The snake was set apart from another kind of whip snake after researchers at the University of Adelaide analysed tissue and DNA samples which revealed the existence of an entirely new species.

Dr James Nankivell, a DNA researcher at the university, was the lead author of the study on the desert whip snake.

“Unlike other species of whip snake, the desert whip snake has a blueish body with a copper head and tail. It also doesn’t have as much black on its scales as its closest relative,” he said.

“These subtle but consistent differences in external appearance and genetic evidence have led to us identifying this new species of whip snake.”

The name Demansia cyanochasma, meaning blue gap, reflects the snake’s marking, with a blue body and copper head and tail. It reaches around 90cm in length and preys on lizards.

While venomous, researchers say a desert whip snake bite is unlikely to be seriously harmful to humans.

ESA listing debate

Four species are under consideration for protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), with debate arising around the possible impact of the move on conservation.

The Bornean earless monitor lizard (Lanthanotus borneensis), blue tree monitor lizard (Varanus macraei), bleached sandhill skipper (Polites sabuleti sinemaculata) and pinyon jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocepalus) are the species that have been put forward for listing.

As non-native species, a listing under the ESA would mean that even captive born members of the species could no longer be sold by private breeders. The decision is controversial as the move would prevent global populations of the embattled species being allowed to grow via captive breeding in the US. Each of the species’ habitats are at risk from various factors, making them all likely candidates for listing under the ESA. The Bornean earless monitor lizard’s habitat is under severe threat from deforestation while the pinyon jay’s pinon-juniper woodland is at risk from increased wildfire frequency and invasive species, as well as climate change.

While the listing may provide some protection for wild members of the species, it could also prompt an initial drop in global numbers. The overall effect on conservation of these imperilled species remains to be seen.

Carpet python parasite removed from woman’s brain in world first

The bizarre story of an Australian woman infected with a parasite has been documented in the first known case of a worm being found alive in the brain of a human.

An 8cm long worm, typically found in carpet pythons, was pulled from the woman’s brain during surgery in Canberra, to the shock of the theatre team.

The woman, 64, had been suffering from ill health prior to the operation, with symptoms including stomach pain, night sweats, forgetfulness and depression. The medical team believe the parasite could have been in her brain for as long as two months.

It is thought the woman contracted the roundworm after collecting and cooking with Warrigal greens, a

What do birds say on Halloween?

2 OCTOBER 2023 Exotics News

©Mark Hutchinson

©Canberra Health

native grass in the area where she lived. The plant was contaminated with python faeces containing parasite eggs which allowed the worm to pass to the woman.

Researchers say the incident, although the first of its kind, highlights a growing danger of infections being passed from animals to humans.

"It just shows as a human population burgeons, we move closer and encroach on animal habitats. This is an issue we see again and again whether it's Nipah virus that's gone from wild bats to domestic pigs and then into people, whether it's a coronavirus like Sars or Mers that has jumped from bats into possibly a secondary animal and then into humans," Dr Senanayake, an associate professor of medicine at the Australian National University (ANU), told the BBC.

"Even though Covid is now slowly petering away, it is really important for epidemiologists… and governments to make sure they've got good infectious diseases surveillance around."

nose to burrow through earth in search of toads, its primary prey.

The Devon-based specimen has captured the interest of many, with Ms Johns releasing an update on Instagram reporting that, while the snake seemed to be doing well, only the right-hand side head was currently eating, while the left was not accepting food, but would simulate a chewing motion while the right-side fed.

Evidence of nuclear events found in the shells of tortoises and turtles

A study has shown that evidence of nuclear events is stored in the shells of tortoises and turtles who live in the vicinity of historic nuclear activity.

Researchers have found traces of uranium, a key element in nuclear weapons, in the scutes, or shell plates, of turtles and tortoises exposed to nuclear bombs decades ago. This discovery makes them a chemical record of nuclear history and provides valuable insight into the long-term effects of nuclear activity on the environment.

Five species of the reptiles tested were all from areas historically affected by nuclear contamination, including the Nevada National Security Site and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The species tested were a green turtle scute, collected in 1978 from the stomach of a tiger shark caught near the Marshall Islands. The second was from a Mohave desert tortoise, collected in 1959 near the Nevada National Security Site and the third was from a river cooter collected in 1985 at the Savanna River Site, a location for uranium fuel fabrication. The fourth scute tested was from an Eastern box turtle collected in 1962 from the Oak Ridge Reservation in Tennessee which saw uranium production in the 1940s. A scute from a Sonoran desert tortoise, collected in 1999 at the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, was used as the control specimen, as the site had seen no known nuclear activity.

Rare two-headed snake hatches

A Western Hognose snake has surprised owners at Exeter Exotics pet shop by hatching with two heads, a rarely seen phenomenon that occurs when an embryo that should have been twins fails to split properly.

The bicephalic reptile will not be sold by the shop and will likely have a reduced life span due to its condition.

Shop owner Alicia Johns has mixed emotions about the surprise arrival, telling the BBC: “It’s fascinating but it is still sad. If we ever felt it got to the stage where he was deteriorating or wasn’t doing well or was uncomfortable or in pain, then that’s when we’d re-evaluate the situation."

The Western Hognose species is found in North American grasslands, prairies and arid terrain, and uses its upturned

In all the specimens except the control, uranium levels surpassed those of naturally occurring uranium, showing the extent of the shells’ ability to store environmental elements. Scutes are made from keratin, the same material as human fingernails, and grow in layers. If a turtle or tortoise takes in uranium, it become trapped in the layers of the shell, providing an environmental record over decades.

The long life-span of turtles and tortoises mean they can offer insight into changes in the environment over time and how human activity lingers in the natural world. It is unclear whether the highly-enriched uranium found in the scutes had any adverse impact on the health of the animals as all of the specimens died many years ago and were sourced from museum archives, but the study has shown the potential that further research in this area can offer.

3 OCTOBER 2023 Exotics News

Prefer to get a quote than a joke? Visit exoticdirect.co.uk Trick or Tweet!

©Exeter Exotics

Trained sniffer dog used to detect endangered newts in new study

According to a study published by researchers at the University of Salford, a detection dog was highly successful in finding great crested newts, both underground and at a distance.

The trained sniffer dogs offer the highly-endangered species a greater chance at survival by accurately locating the evasive reptile. Difficulty in locating the newts hampers the effectiveness of conservation efforts, with construction projects going ahead despite newts existing at sites undetected.

The great crested newt has two life phases; an aquatic phase and terrestrial phase, with little known about the latter, making protecting the newt during this phase a challenge. During the terrestrial phase, the newts live below ground, making the new study a much-needed aid

ON THE WEB

in the protection of the species.

Freya, a six-year-old English springer spaniel, was used in the study, which determined whether she could detect the newts at a variety of distances and through different substances, including sandy soil, clay soil and substrates with vents that simulate burrows made by mammals, a key habitat of the newts.

Recording only two false positives out of sixteen trial runs, and 87% success rate, Freya was able to detect the newts across the entire distance range, which started at two metres. She was able to successfully indicate the presence of the newts with high rates of accuracy across different terrains and soils.

The authors of the study said: “This pioneering research shows how detection dogs can be a valuable addition to the current toolbox used to locate threatened amphibian species, particularly those using subterranean shelters. This study also highlights how soil type can have an influence on the accuracy and speed of detection.”

Sandfire Ranch owner passes away

Bob Mailloux, a prominent figure in the herpetology community, has passed away after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease.

Mr Mailloux and Phillipe de Vosjoli founded Sandfire Dragon Ranch, a breeding farm for rare lizards and frogs, primarily bearded dragons. Bob was widely viewed as a pioneer in the industry, selectively breeding red and orange bearded dragons, creating the popular sandfire colour morph. This work is credited with popularising the bearded dragon as the commonly kept and much beloved pet it is today.

The ranch is still in operation in San Diego and many from the herpetology community have paid their respects and acknowledged Bob’s legacy.

Websites | Social media | Published research

The

www.explorewithindigo.com

4 OCTOBER 2023

Exotics News

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

THIS MONTH IT’S: INDIGO EXPEDITIONS

Indigo Mission is to be of Planetary Service, effecting Positive Change for humanity, by addressing wildlife conservation needs, and demonstrating an Appreciation for All Life.

6

Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis niger)

ON THE SH(ELL)DERS OF GIANTS

Breeding Galapagos giant tortoises.

Recently, keepers at Crocodiles of the World in Brize Norton, UK have managed to successfully captive-breed Galapagos giant tortoises for the first time in a UK zoo. These Endangered reptiles are iconic species that are only found in the remote Galapagos archipelago, making them particularly valuable for education in European collections. We caught up with Jamie Gilks, Head of Reptiles, to find out more.

The Galapagos Islands

The Galapagos Islands are an archipelago of Pacific Islands around 1,000km off the coast of Ecuador. There are 19 “large” islands in this group with a total of 127 islets, rocks and islands. Famously, the Galapagos Islands are a hub for biodiversity. Their unique volcanic geography amidst the ocean means that the flora and fauna found here have been isolated for hundreds of thousands of years. Eventually, this led to speciation that helped Darwin formally recognise the theory of evolution. There are countless unique species found across the islands, but perhaps the most majestic are the giant tortoises of the genus Chelonoidis. Exploited by pirates and early settlers for hundreds of years, each unique species of Chelonoidis

has faced immense conservational adversities which are only recently being addressed. In the last few decades conservation and in-situ captive breeding of giant tortoises has been broadly successful, but now zookeepers across the world are starting to learn more about the genus.

Sourcing an icon

Crocodiles of the World is a reptile-focused zoo that had planned to house Galapagos giant tortoises for a long time. “Our opportunity to house ‘Galaps’ first came in early 2018 after the arrival of three females from Chester Zoo” explained Jamie. “The females all hatched at Zoo

8 OCTOBER 2023 On the Sh(ell)ders of Giants

Zurich in 2001 and are hybrids between Chelonoidis becki, a species found on the north of Isabela Island, and C. porteri a species from the west of Santa Cruz.”

“Dirk, our male’s history is not as clear-cut as the females. We know he first came to Europe in 1965 and has moved between a few collections before coming to us from London Zoo in the July of 2018.”

Dirk was hatched in the wild and as such, has a huge amount of potential to support breeding stock in UK and international collections. As a member of the European Studbook, he is being closely monitored to ensure that his genetic potential is well-regulated. Keepers at Crocodiles of the World have sent off blood samples that aim to identify his exact species.

Although the females and subsequent generations of Giant tortoises that were bred at Crocodiles of the World are hybrids, maintaining these flagship species within zoological collections. Although these animals are hybrids, their ability to educate and inspire zoo visitors has a huge benefit to conservation.

Jamie continued: “Hybridisation between different species of Galaps is an interesting topic within itself. They can play an important role when it comes to species recovery, especially if they carry the genes of extinct, or functionally extinct species. Even sterilised hybrids were released on Pinta Island to act as stand-in eco-engineers, and these make for great platforms when speaking with our visitors about Galaps, and some of the struggles they face.”

9 OCTOBER 2023 On the Sh(ell)ders of Giants

Husbandry methods

The Giant tortoise exhibit at Crocodiles of the World is a total of 183sq meters and houses a group of four adults. 97sq meters of it is comprised of usable indoor space, and the rest is an outdoor paddock. When temperatures exceed 14°C, the tortoises have access to both the indoor heated exhibit and the outdoor paddock. This allows the tortoises to thermoregulate as they require. The design of the enclosure has been carefully planned to meet the reptiles’ complex needs.

Jamie continued: “As for life support systems, our setup is fairly standard for larger reptile exhibits. The exhibit has two basking areas, one larger and one smaller. The larger basking zone has two 8 x 54w Lightwave units working alongside two 1.5kw shortwave infrared heaters, and the smaller basking area has one of the 8 x 54w Lightwaves and one infrared heater. All the Lightwave units in this exhibit are fitted with four 14% T5 tubes and 4 of the 6500 kelvin grow lamps that come with the unit and run for 10 hours a day throughout the year, and we get UVI readings of 4-5 depending on the basking zone and who might be in it. Any additional lighting comes from the exhibit glass and skylights that are subject to our photoperiod here in the UK. Additional ambient heating is provided by two 5kw air source heat pumps that also have the option to run them on air conditioning modes, this can be very handy for us during the summer as the building is so well insulated, and there are short periods where we may need to keep the tortoises in to help the grass in their paddock

recover. However, we do keep the use of air conditioning to an absolute minimum due to running costs, and the air conditioning can reduce the humidity levels within the exhibit, but we can counteract this with our misting system if needed.”

The tortoises are provided with two main seasons throughout the year, with gradual increases and decreases in parameters to help ease between the two seasons. These broadly mirror the climatic changes in the UK. October to March is the cooler and drier season, and this is when our females will usually nest and lay eggs. During this time, temperatures will usually range between nighttime lows of 18°C to daytime highs of 26°C. April to September is the breeding season and this is when keepers will provide warmer and wetter conditions that range between around 22°C and 32°C.

“When feeding our Galaps we follow a rolling diet sheet that is based upon the group’s current weight each month” added Jamie. “This helps us increase food intake during the summer, which also happens naturally when the tortoises have more grazing access in their paddock, then in turn slightly reduce their intake during winter.”

“We offer a staple diet of Agrobs and hay with supplementation throughout the year, but we will make this mix a little wetter in the warmer months. On top of their staple, we also add seasonally available weeds, greens, Opuntia and other browse options daily.”

10 OCTOBER 2023

Too much of a good thing

Housing and caring for such enormous animals are likely to present a few challenges. However, Jamie claims the biggest challenge is “maintaining the group dynamic”. Even with a very large paddock for the animals to explore, keeper intervention to ensure an amicable environment is required for many species. However, the added weight of a giant reptile can make this very difficult.

Jamie explained: “For the first two years of keeping the species, our temperatures were a bit higher than the ones I’ve mentioned and the use of the rain system in the exhibit was done at a similar consistency throughout the year. This essentially caused us to have a prolonged breeding season. Although we wanted the animals to breed, we didn’t want this to happen at the expense of our females. Like most tortoises, male Galapagos tortoises aren’t the most delicate when it comes to breeding, and they can be relentless. Dirk, our male, is over 100kg heavier than our lightest female so continuous mating throughout the year was an obvious concern. It was at this point we looked to improve the seasonal parameters we were offering and added a refuge area for our females. The refuge area was made by installing a series of removable posts that divided off approximately a quarter of our indoor house, the spaces between these posts allows the females to pass through freely whilst being too narrow for our male to access.”

Breeding begins…

Pre-conditioning for breeding began two years before the keepers found the first viable eggs. They did this by revising and improving the parameters within the enclosure to better reflect those within the tortoise’s natural range. This helped offer more defined seasons in which breeding and nesting would take place.

“One thing we have learnt is that the time spent not breeding is equally as important as the breeding season itself” added Jamie. “As a result, I believe we have reduced the level of stress for our females and in turn have a generally happier group.”

“Although we’d like to take some credit for the breeding, all the hard work came from the tortoises themselves. We were already collecting eggs before any changes were made; however, these eggs weren’t viable. I don’t think the changes we made necessarily improved fertility either, at the time our females would have been around 20 years old and Galapagos tortoises usually start reproducing at around 25 years in the wild, so I think our girls were just a bit too young at that time.”

“We had always noticed that eggs were laid in the wintertime and nesting usually began as light levels reduced later in the afternoons, the nesting and laying process would usually

11 OCTOBER 2023

On the Sh(ell)ders of Giants

A Galapagos giant tortoise hatching

The hatchlings must be measured frequently

go into the evening and take about 3-4 hours from start to finish. As this process generally happened when we weren’t around a camera system was installed so we would know who has laid the eggs, and where we would need to dig the eggs up from the next morning.”

The tortoise’s nests measure around 30cm deep, with a chamber width of around 20cm. The number of eggs in each clutch varied drastically from 2-16 eggs. Once the eggs are collected, they are artificially incubated at 28°C, which usually takes 120 days.

Juvenile giants

Although not commonplace, captive breeding of Galapagos tortoises has been well documented for a long time. However, most successful attempts have occurred within the tortoise’s natural range, and in the United States. Breeding in Europe is less frequent, with only a handful of collections successfully breeding Galapagos tortoises over

the years, so the keepers at Crocodiles of the World are rightfully “thrilled” to produce the UK’s first ever captivebred Galapagos giant tortoises.

The juvenile tortoises are cared for in a similar way to the adults, although they are housed in a different building. Here, temperatures are slightly warmer and more humid and more stable. This allows the keepers to carefully monitor the animals’ progress. Like many large Chelonians, Galapagos giant tortoises are reasonably slow-growing and will take many years to reach the impressive size of their parents.

All ten of the hatchlings are still housed at Crocodiles of the World but will likely be moved on to other collections across the world, once the animals are grown on.

Jamie continued: “We’re very happy with the growth rate so far. Generally, captive individuals in Europe and the US have grown at a much faster rate than their wild

12 OCTOBER 2023

On the Sh(ell)ders of Giants

counterparts, even when compared to captive-bred individuals within their natural range. Because of this, we’ve been quite cautious when it comes to their diet and growth because we don’t want to grow them on too quickly when compared to their wild counterparts, and we want to make sure their shells grow as smooth and evenly as possible. Our first two hatchlings both hatched at close to 70g and now they weigh closer to 150-160g and are in great shape and condition.”

Public perception

Being such iconic species, a large part of the value of maintaining Galapagos giant tortoises in captivity is their outreach and educational

potential. As they only live on such a remote archipelago in the Pacific, few people will ever get to witness these animals with their own eyes. Zoological institutions can, therefore, bridge the gap and inspire new generations of herpetologists.

“Public perception has been great” added Jamie. “Everybody seems to love the tortoises whether they’re a reptile enthusiast or a member of the public. I would say our Galap exhibit has become one of our most popular and receives great dwell time because there is always something going on. We even introduced a ‘meet a keeper’ session at our Galap exhibit because we were getting so many questions about them.”

“One of the biggest misconceptions we get is from visitors thinking that all Galapagos tortoises are the same, or even extinct, mainly because visitors are often aware of the press coverage back from when Lonesome George died. These misconceptions often turn into some of the better conversations between our team and visitors.”

Crocodiles of the World have also established a “feeding experience” that allows visitors to get up close with the tortoises which directly supports The Galapagos Conservation Trust through financial donations. “It is great to have opportunity to support their great work protecting not just tortoises, but many other species on the Galapagos Islands” Jamie concluded.

13 OCTOBER 2023 On the Sh(ell)ders of Giants

The indoor area of the giant tortoise exhibit

OCTOBER 2023 15

MORE THAN A BOX OF SAND

Busting the many myths of sand boa husbandry.

Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

FLASHBACK FEATURE

Sand boas (Eryx sp.) are a fascinating, yet often overlooked group of snakes that have been kept and bred by specialist keepers for decades. As their common name suggests, they live predominantly fossorial lives and have developed unique adaptations to thrive in harsh arid environments. Whilst many hobbyists disregard them as uninteresting and reclusive snakes, perfecting the captive husbandry of these animals can be a complex and rewarding endeavour.

Eryx

There are twelve distinct species of sand boa and several subspecies. They are an extremely widespread genus, stretching across Africa and Asia. Eryx jaculus can even be found in Europe as far West as Greece. There are also several threatened species in India and Sri Lanka. Each species exhibits subtle differences indicating which environments they inhabit. All are short, stocky snakes which help them quickly submerge beneath the sand. They have also developed (to varying extents) a hardened shovel-like nose to allow them to dig through soil and manoeuvre through root systems. Most also have intricate dorsal patterns, to break up the shape of any exposed parts of their body and protect them from aerial predators. Species from sandy environments, such as the Arabian sand boa (Eryx jayakari), have eyes on the top of their heads to allow them to stalk prey within loose sand. Their comical appearance has given the sand boa a reputation far removed from their fierce predatory behaviours. The colouration of all species

varies drastically depending on locality and sex. Males tend to be smaller but much more vibrant. Because they are so widespread and live reasonably cryptic lives, taxonomists are still regularly making distinctions. Most famously, almost the entire Eryx genus was recategorized as Gongylophis between 1999 and 2010.

As ambush predators with straightforward care requirements, sand boas can and have been kept successfully since the 00s. Previously, they were imported from various countries including Tanzania and Pakistan which have since ceased exportation of live animals. Now, all species are CITES listed, which means trade is regulated. Whilst the number of sand boa species available today is a fraction of what it was in the 90s and 00s, good numbers of captive-bred individuals are still being produced. Unfortunately, their simplistic environmental conditions and a misleading common name has created a mirage of myths around the care and keeping of sand boas across the world.

18 OCTOBER 2023

More Than a Box of Sand

Sand boas in captivity

Chris Jones has kept sand boas for 20+ years and has maintained a collection of over 100 snakes across eight distinct species during that time. He has produced several articles and essays on the husbandry of the Eryx genus throughout that time and supported multiple publications on the topic. “Sand boa husbandry really hasn’t advanced much in recent years and that’s something I want to change” explained Chris. “The reality is sand boas are not and are never going to be the most popular pet species because frankly, they hide a lot. That doesn’t mean we can’t provide better husbandry methods.”

There are several species which are readily available in the UK. Although the

Kenyan sand boa is the most popular, the Saharan sand boa (Eryx muelleri), rough-scaled sand boa (Eryx conicus) and Russian sand boas (Eryx miliaris) are also frequently available. “Saharan sand boas are second most popular in the UK because they have been imported as wild-caught for quite some years” added Chris. “Years ago, this used to be why the Kenyan sand boa was so popular, but you can’t do that anymore. Various countries have stopped imports and Tanzania has now been closed for some years. There are now people breeding Saharan sand boas in captivity, which is nice to see. They’re also a very interesting species to breed as they’re an egg-laying species which is extremely unusual for Boids. Eryx muelleri and Eryx jayaraki are

both egg-layers and provide a unique breeding opportunity for hobbyists who were working with them many years ago. The embryos develop inside the eggs within the female’s body for most of their development time. When the snakes are near the end of their development cycle, the female will lay her eggs. So, once they’re laid, they’re supposed to hatch after just two weeks.” As species which inhabit the harshest of environments, this natural adaptation has allowed the gravid females to protect their offspring from dry, hostile conditions and ensure the eggs receive enough hydration to successfully develop.

The popularity of captive-breeding sand boas has naturally progressed into ‘line breeding’ to create morphs.

19 OCTOBER 2023

More Than a Box of Sand

Russian sand boa (Eryx miliaris)

These were initially produced in America starting with albinos and anerys. Today, there are dozens of line-bred morphs in the USA. Chris continued: “I was the first to bring in the Indian sunset sand boa (Eryx johnii). Although the species had been kept in the country before, Rick Staub in the USA line-bred them to produce the ‘sunset’ variety. Traditionally, as a baby, that species starts off orange and eventually grows into a more drab, brown colour. His selective breeding has now meant that there are highorange Indian sand boas in the hobby.

As well as genetic mutations, various localities such as the “Dodoma” from Tanzania, have brought new colourations and patterns into captive-bred animals. Slowly, these morphs reached Europe and are now becoming increasingly popular in the UK. Chris continued: “Eryx rufescens was once thought to be a separate species. I and many other enthusiasts disagreed with this, and it is nice to see it is now considered a locality

variation of E. colubrinus. Because of this recategorization, nowadays we are starting to see “striped” and “granite” sand boas, which have been produced by breeding two naturally occurring locality variants.”

Some populations are extremely rare and protected by international law. The rough-scaled sand boa (E. conicus) comes from India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. As a region with an alarming rate of snakebite fatalities, instances of human/animal conflict are extremely common. Researchers who are often called out to remove ‘problem’ animals, many of which are nonvenomous snakes, have identified and photographed a naturally occurring population of albino rough-scaled boas in Western Maharashtra. As India is closed for export, this population is protected and provides remarkable insight into an ecosystem that allows snakes with albinism (usually an extremely detrimental mutation) to survive well into adulthood.

Sand boa husbandry

Chris has been looking toward natural husbandry methods for a long time, which allowed him to become one of the first UK hobbyists to successfully breed Russian sand boas. This is because he adopted a slightly different approach from many of the commercial breeders at the time. “I didn’t put them into a tub with a heat mat on a thermostat and hope for the best, which is what a lot of people were doing back then” explained Chris. “Sand boas, particularly the Russian species, can be exposed to very harsh winters and very hot summers. Back then, instead of a heat mat underneath, I had a halogen heat lamp to provide overhead heat. The hot spot was more than 42°C. But, all year, I would turn this off at night, so they had no additional heat. During the summer it was warmer and during the winter it was obviously colder, so I basically just changed the photoperiod.

“In the run-up to the breeding season, I would wait until it was raining outside, so the air pressure drops, then I just flooded the tank. I would pour a jug of water into the substrate and completely drench the enclosure. Gradually, as it was warming up, I let the enclosure dry out naturally over a few weeks. Once the enclosure had fully dried out again, I introduced the animals together and they bred successfully. I also applied this technique to Eryx tartaricus (now E. miliaris) from different localities. These were separate subspecies E. t. tartaricus and E. t. speciosa and again, I managed to breed these under the same conditions as the Russian sand boas.”

Mimicking wild conditions, even if they do appear extreme, can provide a wealth of benefits to captive species. From prompting breeding behaviour, to improving health and vitality, the

20 OCTOBER 2023

Male Albino Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus loveridgei)

Tortoise life substrate

seemingly harsh seasons that reptiles and amphibians face in the wild are important to their biological functions. Whilst keepers must protect their animals from potentially life-threatening conditions, understanding and recreating the native ecosystems of a species should be a goal for all keepers. With new research and products available, hobbyists have de-bunked many of the myths surrounding sand boa husbandry.

Myth 1

Sand boas only feed on rodents.

In the wild, Kenyan sand boas (and possibly other species, though it has been less widely documented) will eat birds as well as rodents and reptiles. Even though they are primarily fossorial, Kenyan sand boas will opportunistically feed on most suitably sized prey that crosses their path. They often inhabit grassy areas and woodland edges and therefore encounter a variety of prey items including fledgling birds that have just left the nest. In captivity, chicks are readily accepted. Their high fat content is likely to be a welcome treat and one which would, in the wild, support a period of brumation or reduced feeding activity. “There are also other ways of providing an enriched diet” added Chris.“For example, don’t just feed the same sized mouse every time. Maybe one day stick a few pinkies in there. Next time, go for an adult mouse. Although chicks may be a little too large for a male, they can add some variety to an adult female’s diet.”

Another major misconception about sand boas is their fossorial behaviour. Whilst these ambush predators will indeed spend most of their time beneath the ground, as the sun sets, they will emerge to explore. They have even been recorded in elevated positions in tree trunks and amongst tree roots. In captivity, even the largest enclosures will not provide the same climbing opportunities as a wild sand boa might utilise and therefore, all climbing opportunities are likely to be utilised. Active males will leave the substrate to explore

branches and cork bark tubes and so it is a good idea for keepers to maximise the potential of their enclosures by providing branches and décor above the substrate.

Myth 2

Sand boas live in the sand.

It is completely understandable why people might think this. Not only is there a clue in the name, but the most famous sand boa species to those who are not herpetology enthusiasts is the Arabian sand boa. This species is extremely well adapted to harsh deserts with eyes on the top of its head and a pointed snout. Its comical appearance might make it the star of many nature documentaries but it is rarely kept in captivity and thus does not represent the requirements of most commonlykept species. In fact, most sand boas inhabit semi-arid locations and some experience seasonal monsoons. Therefore, a bone-dry tub of play sand does not provide an enriched or naturalistic environment for any of the readily available species.

Chris continued: “Should you keep sand boas on sand? Broadly speaking, no. I have tried many different substrates over the years, and I don’t like sand on its own. It’s just not that natural. Instead, a natural substrate would be more akin to the ProRep BioLife Desert substrate. Or, if you ignore the name, LeoLife is brilliant for rough-scaled sand boas that come from the same India/Pakistan region as leopard geckos. The important thing here is that it’s a loam/clay mix. In some cases, they will want to create a small burrow area which is possible with a clay mix, as opposed to sand which will just collapse in on them all the time. They also hold moisture and they’re just prettier. I’ve also tried using ProRep Tortoise Life which is great for Russian sand boas as well as TortoiseLife Bio which will hold a lot more moisture. I’m testing that one at the moment, but it’s going well. The point is these animals do not come from the Saharan desert where you picture dunes as far as the eye can see.”

21 OCTOBER 2023

Sunset Indian sand boa (Eryx johnii)

Myth 3

Sand boas never see the sun.

Sand boas are mostly nocturnal and spend most of their time beneath the surface of the ground. However, almost all species have been photographed above the surface, during the day (or early evening) at some point. Therefore, full-spectrum lighting is a necessity for Eryx, even if they don’t openly bask like Uromastyx or Testudo from the same regions.

“I’m a firm believer that overhead heat is the right approach” added Chris. “Burrowing animals that reside in deep layers of substrate - particularly underneath a hot rock - will naturally receive heat for several hours after dark. Not only is a spot bulb more natural, but you’re also providing visible light. Sand boas are not strictly nocturnal. I’ve seen them regularly out during the day, depending on the species. There’s a good cause to offer natural light and UV but unfortunately, not enough studies have been done on those species. I must say, I have never seen any sign of ill health in sand boas for not receiving UV. But, as we research more species, we’re learning more about the benefits of UV, so I believe it should be made available to them regardless. In this case, a Zone 1 T5, alongside a flood spot would be perfect.”

The photoperiod is also very important and allows the keeper to simulate seasonality. Although water can be introduced to the enclosure to mimic monsoons, daylight hours are one of just a few of ways that a keeper can provide seasonal fluctuations for their sand boa. “Don’t just leave the lights on for a flat 8 hours a day” added Chris. “In the summer I’ll have mine on for 12-14 hours a day, in the winter it might go down to about 7 hours a day. When there’s more light, there’s also going to be more heat. By leaving the spot on, it’ll naturally provide more heat, but I would still turn everything off at night assuming the keeper has normal household living conditions. The snakes need these sharp night-time temperature drops and maintaining a good photoperiod schedule will ensure the snake can thermoregulate effectively.”

Myth 4

Sand boas are easy to house.

Broadly speaking, sand boas have very manageable care requirements. However, it is important to select the right enclosure for the job. Chris explains: “Sand boas are incredibly strong for a snake. When they want to get their head into something, they are one of the strongest snakes pound-for-pound. Depending on the species, they also have

hardened shovel-like noses, so if they want to get into any nooks and crannies in a wooden vivarium, they potentially could get out. I would certainly lean towards a glass enclosure to house these animals. Although, a very young sand boa could potentially escape from some of the ventilation holes in an ExoTerra or ZooMed terrarium. While the snake is still small, the keeper should consider blocking these holes.” A glass enclosure will also provide more depth for the substrate and allow the keeper to easily mount overhead lighting that is completely out of reach of the snake.

Many keepers are exploring bioactive enclosures nowadays. Even novice keepers can create incredibly naturalistic enclosures for a whole plethora of species. Sand boas are no exception, but special considerations need to be made for their exploratory behaviours and strength. Firstly, the enclosure must be large enough for the snake to manoeuvre around its environment without constantly damaging the plants’ roots. This damage can be mitigated by choosing strong agave plants, which can be planted into the substrate whilst still in their pots. If they are dislodged, they can simply be re-planted. Whilst juvenile sand boas are much less destructive, it is a good idea to allow an enclosure some time (6 - 12 months) for plants to become well-established before introducing an adult sand boa. Once the plants are well rooted, even the bulkiest of sand boas will struggle to uproot them completely. The keeper should identify areas where the snake is most likely to burrow (generally under hides, or beneath the basking spot) and avoid over-planting in these locations.

Sand boas in herpetoculture

Sand boas can make excellent pets when cared for properly. However, they may not be appropriate for all new keepers. “In terms of ease-of-keeping, I would say that sand boas are a great beginner snake” Chris added. “Are they the best beginner snake? No. In my opinion, a corn snake will always be the best because most people want something more visible and better to handle. However, if a new keeper is looking to keep a sand boa, I would recommend males because they’re smaller, skinnier and a bit more active too. They are also generally more available and perhaps cost a little less, as most breeders are searching for females. Males are also less likely to destroy plants, so a new keeper can get more creative with their enclosure design. Having said that, they’re not always radically different. For example, a Kenyan sand boa male will be quite a lot smaller than the female – perhaps 2/3 of the size. Indian sand boas, on the other hand, show very little difference.”

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the keeper to do as much research into the species as possible, long before acquiring an animal. Having a multi-faceted approach, by speaking to keepers, breeders and herpetologists as well as researching the wild conditions of this species will ensure that the animal receives the best care and the keeper feels fulfilled in their husbandry practices. Whilst many hobbyists are quick to assume Eryx husbandry is just “keeping a box of sand”, those that are truly passionate about the species can find sand boas to be some of the most fascinating pet snakes available.

22 OCTOBER 2023

Müller’s sand boa (Eryx muelleri)

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

The wonderful world of exotic animals

Cameroon dwarf gecko (Lygodactylus conraui)

As the name suggests, the Cameroon dwarf gecko is a small, arboreal lizard from West Africa. These tiny relatives of the electric blue day gecko (Lygodactylus williamsi) make excellent alternatives to the more readily available day gecko (Phelsuma sp.) species and require similar care.

Cameroon dwarf geckos rarely exceed 7cm in length, so a pair can be housed comfortably in a 45cm3 glass terrarium. Being primarily diurnal, these lizards require Ferguson Zone 2 lighting and a basking spot that reaches 32°C. Keepers should carefully consider décor placement to allow the geckos to thermoregulate. Horizontal bamboo tubes or branches should be placed at different heights within the enclosure to let the lizards move closer to, or further from the heat and light sources.

Daily misting is required. Whilst the species can thrive in fluctuating humidity (60 – 80%), water droplets offer a valuable source of drinking water. A water bowl can be added but is not necessary if the animals are misted frequently.

With some tweaking of the environmental conditions throughout the year and a robust diet dusted with a good-quality supplement, L. conraui breeds readily in captivity. A pair of eggs are glued to plants or branches each month. Whilst this makes them difficult (almost impossible) to remove and incubate in some cases, it does give the keeper plenty of opportunities to provide optimal in-situ incubation and produce more tiny geckos.

Title

Species Spotlight

THE LAST OF GUATEMALA’S DRAGONS

The captive breeding and re-introduction of Abronia to Guatemala’s cloud forests.

Colloquially named “arboreal alligator lizards”, the Abronia genus is comprised of around 30 strikingly beautiful species of Anguimorph lizards that are distributed from Mexico to El Salvador. These reptiles typically inhabit high altitude (1400m+) pine-oak, cloud and pre-montane forests, often restricting entire species to just a single mountain range. This makes their distribution small and their habitat precious. All species are threatened with extinction, and many are categorised as “Endangered”. However, a new project set up by Consejo Nacional de Areas

Protegidas (CONAP), the government agency that is concerned with conservation and sustainable use of biological resources, in collaboration with Parque Zoológico La Aurora may provide one last lifeline for Guatemala’s Abronia.

Arboreal alligator lizards

The Abronia genus is a morphologically diverse group of lizards. Although all species have distinct granular scales and robust angular heads and slender bodies, there are a lot of morphological distinctions within the genus from regal-looking horns to vibrant superciliary patterns and a whole spectrum of colours (sometimes within the same species).

Herpetologists know very little about Abronia because of their secretive behaviours. They occupy remote, hardto-access regions and typically spend most of their time high in the forest canopy. When they are found, they are

generally hiding beneath mosses and lichen or within the tanks of bromeliads.

Rowland Griffin is the Director of Conservation at Zoológico La Aurora and Founder of Indigo Expeditions. He has worked with Guatemalan herpetofauna for 11 years and is currently spearheading the zoo’s Abronia Project.

Rowland told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “As we currently understand, there are 12 species of Abronia in Guatemala and eight are endemic, most with very small distributions. They are rarely seen, so as a group, they are considered one of the most endangered genera of lizards.”

26 OCTOBER 2023 The Last of Guatemala’s Dragons

The Abronia Project

The Abronia Project was founded by Zoológico La Aurora in 2021 as part of the National Conservation Strategy for the genus. The strategy includes an ex-situ breeding component with re-introduction programmes that are being planned, managed and (eventually) executed by the zoo.

“Our ultimate aim is to have three pairs of each endemic species and maintain a cycle of breeding them each year” explains Rowland. “We will then grow the youngsters on until we can fit them with microchips and release them back into the wild.”

The microchips will allow researchers to monitor the success of the reintroductions and understand more about the cryptic behaviours of Abronia once they are released back into their natural habitat. This has the potential to fill a huge gap in our knowledge of the genus once the animals disperse back into the canopy.

Rowland continued: “We have to grow them on for a year because neonate Aboronia’s are tiny. One of the species we have here is between 0.3 and 0.4 grams when they hatch, so they are really difficult to monitor if they are released straight away.”

27 OCTOBER 2023

The Last of Guatemala’s Dragons

Bocourt's arboreal alligator lizard (Abronia vasconcelosii)

NutriRep™ is a complete calcium, vitamin & mineral balancing supplement with D3. It can be dusted onto all food sources including insects, meats & vegetables. No other supplement is required.

with pink or yellow discolouration around the abdomen?

the Tadpole Doctor

Disease in your captive tadpoles?

Have you seen any disease, noticed unusual symptoms, or had unexpected deaths in your tadpoles?

Are your tadpoles bloated – maybe with pink or yellow discolouration around the abdomen?

Have you observed any change in their behaviour, such as: sudden and erratic movements, swimming in circles, loss of equilibrium, sluggishness, floating at the surface or death?

Have you observed any change in their behaviour, such as: sudden and erratic movements, swimming in circles, loss of equilibrium, sluggishness, floating at the surface or death?

Researchers at the University of Oxford need your help. They are trying to track the spread of a newly identified disease of tadpoles. If you suspect that your tadpoles are showing signs of the disease symptoms mentioned above, please make contact at http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk.

Researchers at the University of Oxford need your help. They are trying to track the spread of a newly identified disease of tadpoles.

If you suspect that your tadpoles are showing signs of the disease symptoms mentioned above, please make contact at http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk

http://tadpole-doctor.co.uk

28 OCTOBER 2023

The Royal Society and the University of Oxford bear no responsibility for this project.

tadpole-doctor.co.uk The Royal Society and the University of Oxford bear no responsibility for this project.

Species

Currently, the project has 10 captive individuals representing five species. These species have been selected and sourced carefully to fit into the project’s numerous conservation and educational outreach strategies.

Rowland explained: “The one we have had the most success with is the most Endangered one, Abronia campbelli. They are found in the Department of Jalapa and are only known from 19 km2. Within that range they are only found in oak trees with Spanish moss.”

“Most of the area where these very specific trees grow has been deforested and the only habitat remaining, around 0.05% of its original extent, is actually scattered islands of trees . So, the population within that, even though it is a very small area, is disconnected.”

“We have three pairs of that species, and we also have babies that were born in January this year. One of them is 5.4 grams the others are a little smaller.”

Whilst the project works closely with the most endangered species of Abronia, it also utilises the charisma of some of the more visually-striking species for educational outreach.

“The emblem of the project is Abronia vasconcelosii” Rowland added. “This species isn’t the most Endangered. In fact, it has one of the largest distributions of the Abronia in Guatemala, but it is found around the city. On the outskirts of the city, you can still find pockets of

habitat where they are found and in the past, they would have been found here where the city is located, in this valley. This is the species people are most likely to find in their gardens and it is also very beautiful with its green colouration and yellow auricular spikes.”

Another remarkable species that is far less likely to be encountered by people is Abronia anzuetoi. This species is found only on the southern and western slopes of Volcan Agua near Antigua. It is the largest of the Guatemalan species and can grow up to 40cm.

“Anzuetoi hadn’t been seen by biologists for 48 years until last year and that individual is here in this project” added Rowland. “People were chopping the trees down and she was found amongst the wood and brought to us, so, she’s a very special animal! We’re currently looking for a male to pair her up with and hopefully learn a lot more about this species.”

The only species of Abronia considered by the IUCN as “Least Concern” is Abronia lythrochila. This is because it has a reasonably large distribution around Chiapas, Mexico but there is also a population that borders Guatemala, suggesting it might be reasonably widespread. These animals are known as “red-lipped arboreal alligator lizards” and can be bright red in colouration too.

On the other side of the coin is Abronia frosti which is black and white and only found in a patch of forest no larger than 7km2. This Guatemalan endemic is considered Critically Endangered.

29 OCTOBER 2023 The Last of Guatemala’s Dragons

Abronia anzuetoi

Juvenile Abronia fimbriata

Abronia Building at Zoológico La Aurora

The custom-built building measuring 32m2 is divided into two rooms. One has an open roof that can be retracted to allow for natural UV levels to enter the building, whilst also maintaining natural environmental conditions experienced in Guatemala City. The other room is temperaturecontrolled and allows the project to maintain the higheraltitude species that require much lower temperatures.

None of the Abronia housed in the project are on display to the general public. “Whilst we could theoretically put some individuals into the Reptile House, we want to ensure these animals are completely isolated as the juveniles will eventually be released into the wild” added Rowland. “Introducing them to the house could run the risk of disease transfer and really, there just isn’t space in the reptile house where we can do this and precisely control the climate with such precision.”

All enclosures within the building are 45x45x60cm ExoTerra terrariums with some glass panels replaced with mesh to increase ventilation. There are two levels of enclosures within the building, the top that houses the adults and the bottom that houses the juveniles. On the

top shelf, the animals receive natural sunlight and are also given 1X 5.0 UV Incandescent Bulbs. “We only put the extra heat on, on the days that we are feeding them” Rowland added. “We feed the adult Abronia twice a week and find we get better success if we add additional heat, but if it’s on all the time, they will get too hot.”

On the lower level, the animals have two UV bulbs because they don’t receive as much natural UV from the sun. These juvenile animals have additional heat on them all day, as they seem to feed better when we do that. Rowland explained: “The first year we had the project, we had 20 babies, so it took a lot of working out how the environmental parameters change within this building. Anyone who has done a project like this in the past has released the babies straight away, so we had a lot of working out to do, to get the balance right.”

The youngsters are weighed very regularly to ensure they are healthy. Being such small animals, a weight drop of just a few tenths of a gram could be a significant issue. The babies are also fed more frequently than the adults and take appropriately sized live foods every day. Both adults and juveniles are sprayed with lukewarm water twice a day.

30 OCTOBER 2023 The Last of Guatemala’s Dragons

Trade of Abronia

Abronia are becoming increasingly popular in private collections. Whilst the most frequently-kept species tend to be those of Mexican origin, it is not uncommon to see Guatemalan Abronia traded between keepers. Whilst there has been some success in captive breeding the genus, the origin of these species is certainly unscrupulous.

There has never been a legal export of Guatemalan wildlife out of Guatemala. This means every endemic species that is seen in the UK and US have either been smuggled or are the offspring of a smuggled generation. As demand for these lizards has spiked in recent years and scientists knew very little about some members of the genus until recently, one may reasonably assume that even the captive-bred stock found today are only a few generations away from smuggled animals.

Rowland continued: “One of my pet bugbears is the popularity of Abronia in captivity right now. I understand why that is; they are beautiful, they are a good size to maintain, and they do well in captivity. However, many Abronia have tiny geographical ranges that contain very low population numbers so removing any number of animals has a seriously damaging effect on populations in the wild.”

“I find myself very conflicted because we’re doing everything we can to stop these animals from going extinct. There’s enough pressure with degradation of habitat, that they do not need the extra pressure from the pet trade as well. Even though it’s great that they are being bred in captivity now, in my opinion, it encourages people to look for the less commonly-found species and that results in smuggling.”

“For me, I hear people say ‘we need to remove these animals from the wild to stop them from going extinct’. Well, reintroductions need to be carefully planned and bloodlines need to be considered. I don’t think that is going to happen from a private keeping perspective. How a UK keeper could repatriate Abronia to Guatemala is just, well, it’s not going to happen. If people really want to make a difference, stop spending thousands of pounds on Abronia, put it all together and buy land. That’s what is going to save them!”

Whilst ex-situ captive breeding can certainly help scientists learn more about husbandry and the breeding cycles of different species, it is important to also know the limitations of private herpetoculture. For example, the entire Abronia Project is done under a CONAP permit. There are many components within the strategy including education outreach, habitat preservation, habitat creation, reserve creation, etc. All aspects must be considered before a true label of “conservation” can be placed on captive husbandry.

“Today, we understand the effects of smuggling animals and its effects on a population. We should be more discerning about our choices” states Rowland. “To hear things like; ‘this new species has been discovered in Borneo, let’s get it out of its country and into the trade’ – like what happened with Lanthanotus – legally, before any conservation assessment has been done, before we understand the species’ distribution or natural history is SO frustrating. If someone wants to keep an animal for “conservation” it needs to be done with government backing and various other institutional planning for that to succeed. I feel so privileged to be working with these animals every day and to be taking these steps towards their conservation in the wild.”

31 OCTOBER 2023 The Last of Guatemala’s Dragons

Campbell’s arboreal alligator lizard (Abronia campbelli)

SOME ISSUES ARE MORE THAN SKIN DEEP

Exploring snake dermatology with Dr Michaela Betts.

Exploring snake dermatology with Dr Michaela Betts.

Skin complaints are one of the most common reasons captive reptiles present to veterinary practice and snakes are no exception to this. Reptilian skin differs drastically from mammalian or avian skin in both its structure and physiology, and unfortunately many of the problems that arise are related to insufficient husbandry.

Common skin problems of snakes include difficulty shedding (including retained spectacles), parasitic disease, burn injuries, and cancerous changes. However, skin changes from fungal and bacterial infections, viral infection, and other abnormal skin complaints can be seen. In countries outside of the United Kingdom where feeding of live vertebrate prey to snakes may be legal, bite wounds from prey and related subcutaneous abscessation is also commonly reported.

Reptilian Skin

The skin of reptiles consists of two layers: the underlying dermis and the outer epidermis. This epidermis is then covered with keratins. The scales represent a folding of this epidermis and they cover almost all of the reptile skin. Snakes have the greatest folding seen in reptiles where adjacent scales overlap with each other and join through a flexible hinge region at the caudal end. Reptile skin contains relatively few glands compared to other species and is generally dry to the touch. Snakes possess paired anal scent glands at the base of their cloaca.

Boas, pythons, and vipers possess specialised labial pits that can sense infrared radiation and help with the location and consequent apprehension of prey. For boas and pythons, these pits are located along the edges of the labial scales

and cover almost the entirety of the upper or lower lip. In vipers, these are instead focused in a forward-facing direction mid-way between the nostril and eye bilaterally.

Shedding

Reptiles periodically slough and renew their skin in a process known as ‘ecdysis’. In snakes this process is cyclical and one in which they should shed the entire skin at once, usually as a complete skin rather than patches. Regardless of species, this process appears to be influenced hormonally through the animal’s pituitary-thyroid axis, and the rate of shedding may be influenced by age, temperature, humidity, photoperiod, ectoparasites, frequency and volume of feeding, and on the animal’s general health condition.

34 OCTOBER 2023 Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

The ecdysis cycle itself is divided into five stages of renewal and then a resting phase.

The resting phase follows a slough and is where the skin is in its normal state: a complete epidermis with no cellular proliferation nor differentiation.

The renewal phase begins by cellular activity in the epidermis. Cells begin to migrate and differentiate into new outer layers. Once the “old” skin is ready to be replaced, lymphatic fluid

Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

About the author: Michaela graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 2018 with a degree in Veterinary Medicine. She initially worked with small animal, exotic, and wildlife species before spending 2 years at Suffolk Exotic Vets as a first opinion and referral exotic animal clinician. She currently works as a research assistant in pathobiology and population sciences at the Royal Veterinary College and as a small animal and exotic species veterinary surgeon. Alongside this, Michaela is an educational speaker for Just Exotics, providing further education in exotic animals to other veterinary professionals, and is a member of the British Veterinary Zoological Society and Association of Exotic Mammal Veterinarians. She is currently completing her RCVS Certificate of Advanced Practitioner in Zoological Medicine.

then enzymaticaly digests the bonds holding the older skin to the newer underneath, and at this time the snake may appear to have a blue hue in colour or appear more dull. The skin then starts to detach, typically from around the eyes, mouth, and nostrils, and the skin can be shed in its entirety. The new layers undergo a brief period of drying and maturation as the keratin stiffens. Keepers can evaluate the shed skin to determine if a shed was complete, particularly if spectacle were successfully removed.

Impact of Husbandry on Skin Health

The way a snake is kept will have an impact on its overall health. All species should be housed in appropriately sized enclosures with adequate ventilation and insulation, and the correct heat, humidity, and lighting for the specific species. Substrate, enrichment, and nutrition also needs to be appropriate for the individual. Insufficient or inappropriate husbandry, such as lack of hides, will increase a snake’s stress

35 OCTOBER 2023

An example of a healthy slough by a royal python (Python regius).

Pinkies 1g+ | Pinkies 1g+ | Pinkies 1g+ | Large Pinkies 2g+ | 10 Pack Large Pinkies 2g+ | Large Pinkies 2g+ Fuzzies 4g+ | Fuzzies 4g+ | Fuzzies 4g+ | Hoppers 6g+ | Small 10g+ | Small/Medium 15g+ | Medium 19g+ Medium/Large 23g+ | Large 26g+ | Extra Large 30g+ Ex-Breeder 35g+ | Ex-Breeder 40g+ Rat Pups 4g+ | Fuzzies 12g+ | Hoppers Small 20g+ | Weaner Small 30g+ | Weaner Medium 50g+ Weaner Large 70g+ | Small 100g+ | Small/Medium 130g+ | Medium 160g+ | Medium/Large 200g+ | Large 250g+ Extra Large 300g+ | Jumbo 350g+ 5 pack | Ex-Breeder 400g+ | Ex-Breeder 450g | Ex-Breeder 500g

levels, which can contribute to immunosuppression and consequent development of disease.

Enclosures should not contain any crevices or corners that prevent adequate cleaning. Regular spot- and deep-cleaning should be undertaken with soiled substrate always being replaced. Organic matter such as excrement can inactivate disinfectants. A thorough clean of surfaces and in-contact items with a mild detergent such as warm soapy water should be used to initially clean before application of a reptile-safe disinfectant for the appropriate contact time as advised by the manufacturer. Substrate should be absorbent and non-toxic, and care taken that it not become waterlogged. Soil and peat can be difficult as they may carry a high microorganism load compared to other substrates. Moist unsanitary substrate encourages bacterial growth and increases the likelihood of secondary bacterial infection.

A water bowl should be provided that is large enough for the snake to bathe in and should be changed with fresh water daily. Abrasive objects such as rocks can help to assist with shedding but there shouldn’t be any sharp edges that could cause trauma to the skin.

Snakes rely on environmental heat sources to maintain their body temperature. It is important that their enclosure is within their optimum temperature zone and provides an adequate heat gradient so that they have a hot dry, hot humid, cool dry, and cool humid microclimate within their set-up. Radiant heat sources should be covered with a cage or guard to minimise the risk of thermal injury, and items like heat rocks and underfloor heat mats within the enclosure should be avoided. Thermometers should be placed at the hot and cool ends of the enclosure as a minimum, and ideally minimum-maximum thermometers should be used to identify any fluctuations in temperature throughout the day. Inappropriately high temperatures can lead to death by dehydration and overheating and contribute to difficulty shedding. Conversely,

inappropriately low temperatures will lead to a reduced metabolism which can lead to reduced sloughing of shed skin and an increased susceptibility for opportunistic infections of the skin and other organ systems.

As well as heat, it’s important for snakes to also be provided with an adequate photoperiod as daylight length, temperatures, and relative humidity all feed signals about the “season” to the snake and can have an impact on shedding.

Humidity also has an impact on themoregulation. Less humid enclosures trap less heat and are more likely to experience temperature fluctuations, particularly overnight, whilst more humid enclosures are more likely to result in dampness to the substrate. Appropriate ventilation is key to help maintain appropriate humidity. Within a set-up, a hygrometer should be used to monitor the environmental humidity, ideally in each of the microclimates within the set-up. Inappropriately low humidity contributes to dehydration and trouble with shedding, whilst inappropriately high humidity alongside poor environmental hygiene can contribute to secondary or opportunistic bacterial infection. Humidity may be increased or decreased within an enclosure through misting or providing a greater or smaller water surface area for a water container near a heat source.

Dysecdysis

The term “dysecdysis” describes the abnormal or impaired shedding of the outer layers of the epidermis and is one of the most common conditions affecting reptile skin. For snakes, this refers specifically to the failure of the whole shed to come away in a single attempt.

Despite its common presentation, dysecdysis should be considered a nonspecific clinical sign as it is associated with a vast number of potential underlying issues, including trauma that affects the normal shedding process,

37 OCTOBER 2023

A large Eastern Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) with blue or opaque eyes, about to shed its skin.

nutritional deficiencies, dehydration, infectious disease, inappropriate humidity or temperature, and a lack of appropriate materials within the set-up to facilitate a shed.

Low environmental relative humidity can lead to dehydration of the sloughed skin in the short-term, not just of the snake itself in the long-term. Temporarily increasing the environmental humidity at the time of ecdysis can sometimes help to remove the slough. In the author’s experience, 20-30 minute soaks in warm, shallow water often proves sufficient for amenable snake patients, and encouragement to gently move over wet abrasive surfaces such as a damp towel. However, the underlying reason for the condition should always be investigated.

Once the primary problem has been identified and treated, normal shedding should usually return within two or three cycles and, if caught early, most snakes have an excellent chance of making a full recovery. Optimal husbandry practices for the species and the elimination or prompt treatment of any condition that may interfere with the normal shedding process are key to its prevention.

Retained Spectacle

Retention of the ocular spectacle can occur in snakes undergoing difficult shedding, either attached to retained slough over the head of the snake or of the spectacles only. Typically it has a wrinkled and slightly opaque appearance, but it is important to not confuse this with a dehydrated spectacle, a normal spectacle with previous

ocular damage, or the slightly duller appearance of royal python (Python regius) spectacles compared to some other snakes. The more layers retained, the easier to identify but also the more challenging to remove. However, examining the shed for the spectacle is a good way to assess in the absence of slit-lamp illumination at home. The most common cause tends to be inappropriately low environmental humidity or dehydration, but systemic disease, ectoparasitism, and malnutrition may also be contributory factors.

Gentle soaking of the area in warm water and application of moist cotton buds from the canthi towards the centre of the eye can help to remove retained spectacles. Extreme caution must be taken to not damage the underlying spectacle as doing so can lead to eventual loss of the eye. Sometimes this method is insufficient and veterinary attention may be indicated and medications prescribed to help soften the spectacle and then removal re-attempted.

A Note on Hyperthyroidism

An increase in the frequency of ecdysis may be an indication of a systemic disease process in snakes, including hormonal issues. In older snakes, particularly cornsnakes, hyperthyroidism is a reported endocrinopathy. This may be due to enlargement of the thyroid gland due to hyperplasia or neoplasia. An ecdysis cycle may be observed as frequently as every two weeks in affected snakes. Other associated signs with this condition include increased aggression, increased appetite, and muscle wastage.

38 OCTOBER 2023

An example of a blue form of white-lipped pit viper (Trimeresurus insularis).

Burns

Thermal burns are a frequent reason for snakes to present to veterinary practice and tend to be due to device malfunction or the use of inappropriate heat devices. Reptiles have been suggested to not have the same withdrawal reflex as mammals and may not recognise that a heat source is burning their skin. Regardless, their lack of moving away from or off of heat devices actively causing their skin thermal damage is well reported. As such, reptiles should never be allowed direct access to heat sources. For this reason, hot rocks/logs and heat mats underneath or inside of enclosures are not recommended, and where possible heat lamps should be placed outside of enclosures. However, if not possible then a protective cage or guard should be placed around the heat source that the snake is unable to get into.

Burns can range from very mild to life threatening in severity and are classified based on the depth of damaged tissue as first-degree, second-degree, third-degree, and fourth-degree. A cold compress can be applied for 15-20 minutes to help reduce further burning and tissue swelling but then veterinary advice should be sought.

First and second degree burns have a reasonable prognosis if treated promptly and appropriately, and tend to take 4-8 weeks to heal. For second-degree burns there is often scar development which may be a source of dysecdysis going forward. Topical therapy and analgesia will be indicated in most cases, as well as support for any shock the snake may be in. For burns more severe than superficial, daily bandage changes, surgical debridement of damaged tissue, and systemic antibiotics to prevent septicaemia may be indicated, and healing will be prolonged over months. In severe cases, euthanasia may be the only option.

It is vitally important to remember that the full extent

of a burn injury may not become apparent until days or even a week after the initial incident, and so despite treatment may start to look worse before it starts to look better. It is also important to be aware that burn injuries typically result in significant protein and fluid loss and so nutritional and fluid support may be needed to prevent hypoproteinaemia and dehydration.

Ectoparasites

Snake mites (Ophionyssus natricis) are the most commonly observed ectoparasites seen and will infest any snake species as well as some lizards. They can often be observed around the spectacle and gular folds or in the environment, particularly dark moist places such as vivarium joints. Mites pose an issue not just from irritation and swelling to the skin, but can also lead to secondary bacterial infection where the skin has been compromised as well as the transmission of viral diseases. Affected snakes may spend more time soaking in their water bowl, which is thought to provide some temporary relief.

Elimination of mites can prove troublesome as they only spend part of their life cycle on the snake, and the rest in the environment. As such, successful treatment requires both treatment of the host with an appropriate anti-parasitic and treatment of the environment in order to break the life cycle. This often requires repeated application at set intervals. Care must be taken to ensure adequate ventilation, rinsing, and drying to reduce the risk of toxicity from antiparasitic residues.

New snakes entering a collection should be quarantined separately for at least 3 months and examined for mites to help avoid introduction into a pre-existing mite-free collection. All set-ups, including furnishings, used for quarantined animals should be sanitised thoroughly between occupants and only used for quarantined snakes.

39 OCTOBER 2023 Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

Ticks attached to the skin of a wild snake.

Vesicular Dermatitis