In a world where bigger is often thought better, it's easy to overlook the micro marvels of nature like the Tropiocolotes genus. ACKIES

• may 2024 • £3.99 NEWS • EGYPTIAN TORTOISE • KEEPER BASICS • SNAKE DERMATOLOGY • REPTILE MIGRATION

www.exoticskeeper.com

KEEPING SAND GECKOS

IN THE OUTBACK

THE

CRESTED GECKOS

We discuss the natural history, habitat and care requirements of Varanus acanthurus using wild observations and expert guidance. ARE YOU TORTOISE RED-Y? Red-footed tortoises may be beautiful, but are they the right tortoise for you? Learn how to keep them successfully. IN

WILD:

Expedition New Caledonia with Blue River Diets

ADVERTISING advertising@exoticskeeper.com

May is here and we are now back from the New Caledonia Expedition with Blue River Diets and have some really exciting content to share! We found several specimens of Correlophus ciliatus and a bunch of other interesting reptiles! You can read all about it in this month’s magazine.

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns Hastingwood Road

Essex

CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4713

Digital ISSN: 2634-4689

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott DESIGN: Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather Subscriptions

Without giving away too much, we found crested geckos active during the day, discovered that their habitats are mostly coastal forests, found the trees they live on and the berries they eat and recorded humidity readings exceeding 90% most of the time. None of these observations line up with contemporary keeping practices, which reinforces the need for ongoing research.

Alongside this article, I’ve also took the opportunity to feature some in-situ observations of ackie monitors and build an extensive piece on the species in a natural setting. Yes, this issue may be a little lizard-heavy, but we want to make sure that readers of EK are given as much in-situ, cutting-edge education as possible.

As mentioned, we’ve got a lot of exciting content coming up. This month, our content is mostly centered around pet care and written by myself. I have, however, gathered excellent content and interviews from Australia, Singapore, Malaysia and Japan ready to release over the coming months. There has never been such a perfect time to subscribe to EK Magazine! Thank you, Thomas Marriott Editor

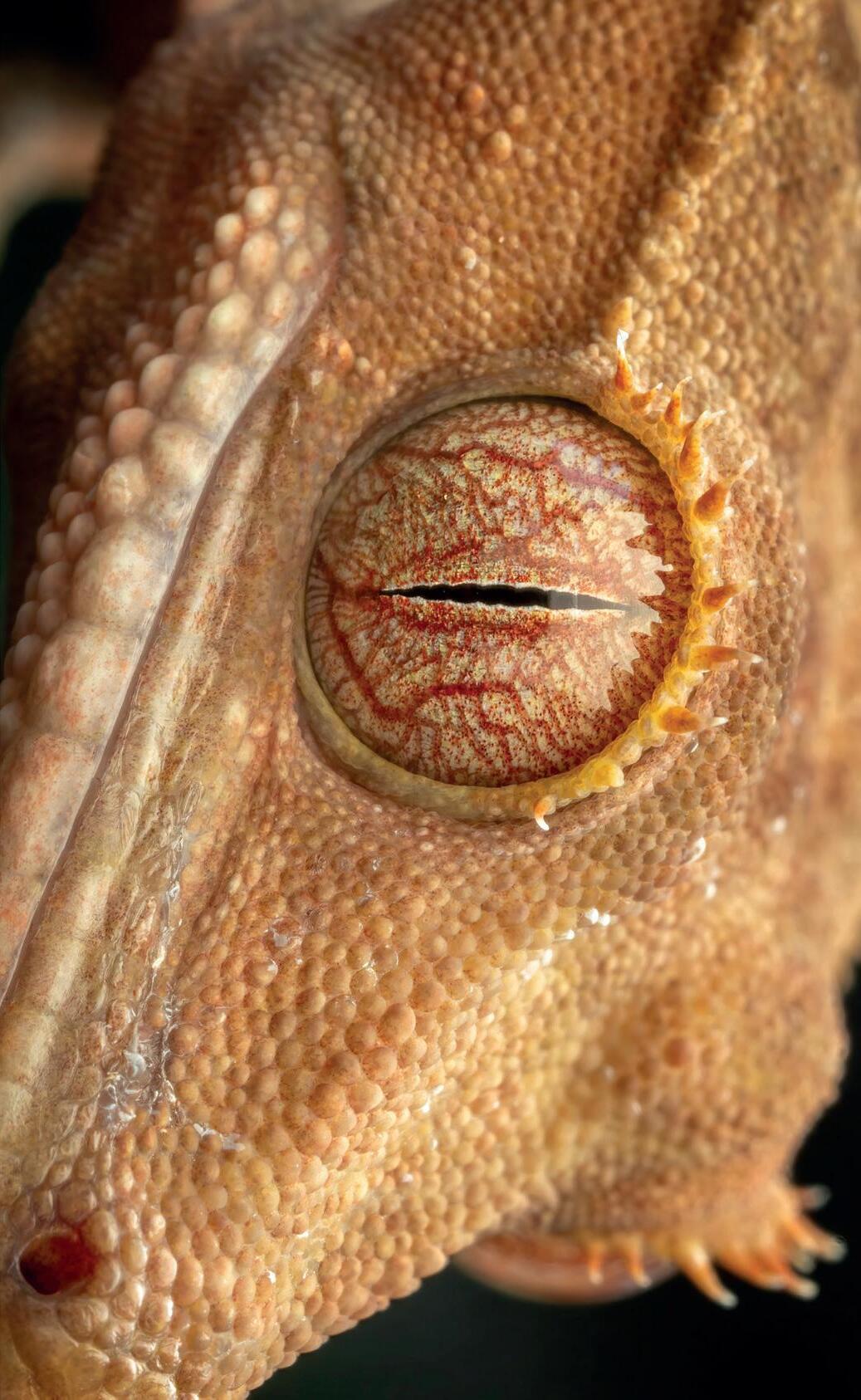

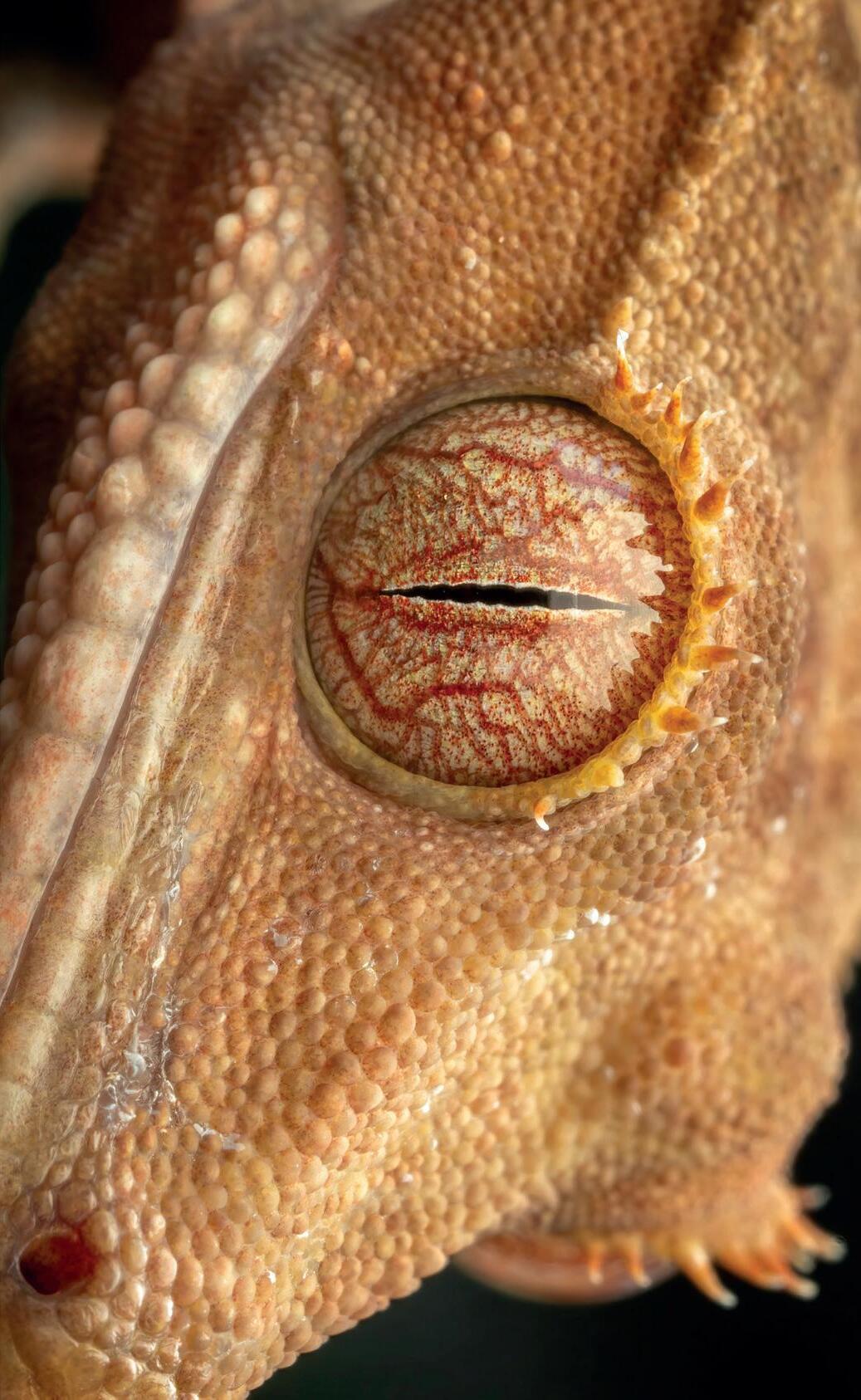

Front cover: Crested gecko (Correlophus ciliatus) Lauren Suryanata/Shutterstock.com Right: Red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius) seasoning_17/Shutterstock.com CONTACT US EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES hello@exoticskeeper.com SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS thomas@exoticskeeper.com

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . About us

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Follow us Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

02 06 24 02 EXOTICS NEWS The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping. 06 KEEPING SAND GECKOS In a world where bigger is often thought better, it's easy to overlook micro marvels like the Tropiocolotes genus. 12 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s the Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni). 14 FLASHBACK FEATURE: SOME ISSUES ARE MORE THAN SKIN DEEP Exploring snake dermatology with Dr Michaela Betts. 24 ACKIES IN THE OUTBACK Natural history, habitat and care requirements of Varanus acanthurus 32IN THE WILD: CRESTED GECKOS Expedition New Caledonia with Blue River Diets. 44ARE YOU TORTOISE RED-Y? The complete guide to red-footed tortoise care. 53 KEEPER BASICS: Impaction & Substrate Choice. 58 FASCINATING FACT Did you know...? 32 44 53

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic animals

New mud snake species described in Vietnam

In a forest wetland in southern Vietnam, two snakes were caught in a net set by residents; a chance encounter that led to the description of a new species.

The fishermen handed their finds over to a team of scientists conducting research in the area, with another of the snakes being found at a nearby rubber plantation. The reptiles’ unusual scale composition made it clear that the species was a member of the Myrrophis genus previously unknown to science.

Named

Myrrophis dakkrongensis, after the Dak Krong river system where it was found, the snake has been distinguished as separate from the other species in the Myrrophis genus- Myrrophis chinensis and Myrrophis bennettii- by observation and genetic analysis.

The adult male snake measured 37.2cm from snout to vent, with a tail length of 7cm. It has dark brown and black dorsal scales and white or yellow and orange lateroventral stripes. One of the females was carrying 12 embryos when the individuals were discovered.

Ringed caecilians found to feed offspring with milk

Despite being observed in some spider species, feeding offspring with milk is a behaviour typically associated with mammals. However the practice has now been observed in ringed caecilians.

The young of the species native to South America are known to feed off the mother’s skin weekly, but scientists have observed another unusual feeding behaviour in the amphibian.

In an effort to understand more about the activity of ringed caecilians, researchers placed a camera in a nest. The team observed the unusual feeding behaviour when, after the offspring gathered around the mother’s tail, it secreted a milky substance which was immediately fed upon by her young.

Upon analysis, the milk was found to contain similar components to mammalian milk, including lipids and carbohydrates, providing a similar nutritional function to offspring.

The researchers observed the behaviour for a two month period, and it appeared to be prompted by tactile and acoustic activity by the offspring, signalling a need to feed to the mother.

The findings have offered a new insight into the parental behaviour and communication in ringed caecilians, making them the first species of egglaying amphibian known to lactate in this way.

The Leishan Mountains Xiong Chaoyang/shutterstock.com

New species of Odorous frog found in China

A new frog species has been described by scientists after it was found in Leigongshan National Nature Reserve in southwestern China.

The new species, with the proposed name Leishan Odorous frog (Odorrana leishanensis sp. nov), differs from existing frogs of the Odorrana genus. In the paper describing the new species, the research team’s analysis indicates that the species is “the sister to the clade corresponding to the O. schmackeri complex, and is morphologically distinct from the latter (vocal sacs absent, and smaller body size in female.”

The Leishan Odorous frog is distributed across mountainous forest regions, at elevations between 1600 and 1900 metres. It has a green back, covered with brown spots, and yellow flanks. The females of the species measure slightly larger than the males.

The new discovery’s name hails from Leishan County, where the holotype was found, located in Guizhou Province.

The new findings show that the evolutionary history of the newly described species is entirely independent of that of the other 65 members the genus. Which

2 MAY 2024 Exotics News

type of snake eats desserts?

©Sang N. Nguyen

©Carlos Jared

Cinnamon frog bred at UK zoo

Cotswold Wildlife Park has successfully bred cinnamon frogs for a second time, in a significant triumph for the species.

The park is one of only six zoos in Europe to keep cinnamon frogs, a species native to the tropical forests of South East Asia.

Typically found across Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, Sumatra and Borneo, the tiny frogs, measuring around 4cm in length, are a distinctive orange colour, earning them their name.

The new arrivals have been named accordingly, and are now known as Paprika, Cayenne, Saffron, Chipotle and Chilli.

Jamie Craig, Curator and General Manager of Cotswold Wildlife Park, said: “Our dedicated Reptile team have been working hard to perfect breeding techniques in our Amphibian Room. Many frog species have incredibly specific requirements, and it is a testament to their hard work that they have now managed to replicate our previous success with the Cinnamon Frogs. With the perilous state of many amphibian species in the world due to the Chytrid fungus, any expertise garnered from the captive populations may well be important tools for the future of these fascinating creatures”.

European Turtle Alliance Conference 2024

The European Turtle Alliance (ETA) has announced its 2024 conference, taking place from 18th to 19th May.

The ETA is a non-profit charity based in the Netherlands that aims to promote chelonian conservation and welfare across Europe.

Following the success of the last ETA conference in November 2023, this year’s conference will take place at Writtle University College in Chelmsford, UK.

A number of speakers have already been announced, with more to follow on the ETA website.

Critically Endangered Mountain chicken frogs bred at London Zoo

Six froglets of one of the world’s most threatened amphibian species have been born at London Zoo.

The new arrivals are the offspring of a pair of mountain chicken frogs (Leptodactylus fallax) who have joined the zoo’s new Secret Life of Reptiles and Amphibians experience.

Mountain chicken frogs are among the world’s largest frogs, weighing up to one kilogram and measuring up to 20 centimetres in length.

Ben Tapley, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians at London Zoo, said: “We are delighted at how quickly the mountain chicken frog colony have settled into their new home. Soon after they arrived, we spotted the female frog guarding her foam nest.”

Male mountain chicken frogs entice their female counterparts to mate by digging a bowl-like structure, where a foam nest is later created for the female to lay her eggs in.

“Mountain chicken frogs are incredible parents. The mother regularly visits the nest to lay unfertile eggs, which the growing brood will feed on, she also guards her nests, puffing up and using her body to defend her young from anything that gets a little too close,” Ben continued.

The species was native to 11 islands across the Carribean, including Montserrat and Dominica. The introduction of the chytrid fungus to the islands in the early 2000s had a devastating effect on populations, coupled with extensive hunting of the species for food, with up to 90% of the frogs being wiped out. It is estimated that only 21 individuals remain in the wild on Dominica.

The intense risk to the species makes the breeding success at London Zoo a significant step in the preservation of the dwindling species.

Prefer to get a quote than a joke? Visit exoticdirect.co.uk A

3 MAY 2024 Exotics News

pie-thon!

fendercapture/Shutterstock.com

Derek D. Galon/Shutterstock.com

New dwarf gecko species discovered in mountains of Venezuela

On the eastern slope of Cordillera de Mérida, a mountain range which forms part of the Venezuelan Andes in western Venezuela, a new species of dwarf gecko has been discovered by scientists.

The new species, Pseudogonatodes quihuai, is similar to its counterparts in the Pseudogonatodes genus in that it is diurnal and dwells among leaf litter on the ground. However, it is distinguishable as a new species by its single postnasal scale.

The paper that describes the gecko, authored by Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, Claudia Koch, Santiago Castroviejo-Fisher and Ana L.C. Prudente, states that

ON THE WEB

the discovery “highlights the still underestimated diversity of this group of Neotropical dwarf geckos and underscores the need for further studies on its systematics and taxonomy.”

Pseudogonatodes quihuai is found in semideciduous montane forests in two locations in the state of Barinas at 1120 to 1319 metres above sea level. It is named after José Daniel Quihua Ramírez, a self-taught wildlife photographer and naturalist who specialises in Venezuelan reptiles and amphibians.

The geckos are dark brown with white spots, with females measuring slightly longer in length than the males from snout to vent at 31.3cm to 33.6cm.

Written by Isabelle Thom

Websites | Social media | Published research

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

THIS MONTH IT’S: HERPING THE GLOBE

“Herping the Globe” is the leading Facebook group for “herpers” who find and photograph wild reptiles and amphibians. Keepers can gain a lot of inspiration from the wild habitats portrayed in this group and understand locality forms in more depth.

www.facebook.com/groups/HerpingTheGlobe

4 MAY 2024

Exotics News

©F.J.M. Rojas-Runjaic

MICRO MARVELS: KEEPING SAND GECKOS

By Alistair Gamblin.

6

Dan_Koleska/Shutterstock.com

Micro Marvels: Keeping Sand Geckos

In a world where bigger is often thought better, it's easy to overlook the micro marvels of nature. The genus Tropiocolotes is no exception. Rarely exceeding a few inches in length, this group of tiny arid-dwelling geckos are among the most underrated reptiles in the hobby. There are more than 10 identified species in the Tropiocolotes genus, all confined to a range across northern Africa and into the Middle East. Due to their similar habitats and environmental needs, the article that follows will provide an overview of the care and breeding of the Tropiocolotes group.

About the Author:

Alistair Gamblin is a herpetology enthusiast keeping 30 species of reptiles and amphibians. As a progressive keeper, he aims to keep the best-suited species in modern bioactive terraria. He shares his keeping strategies on his platform “Rural Reptiles

In the trade

Many specimens in the hobby will have been imported from the wild as adults, although several hobbyists also breed these geckos, frequently selling off offspring as they become rapidly overrun!

There are 2 species commonly found in captivity, T. tripolitanus and T. steudneri, and they are often confused.

This is because they typically share a sand-yellow body with similar mottled patterning from white through to dark browns. Despite this, there are ways that the two can be distinguished, often down to subtle differences in the markings and their colours, or overall tone of the body. I have found that many keepers simply label their animals as ‘Sand,’ ‘Dune’ or ‘Micro’ geckos.

8 MAY 2024

The captive environment

With basic care requirements, a high level of activity, and an attractive appearance, I often find myself wondering why Tropiocolotes aren’t better represented in captivity.

Averaging just 6cm when fully grown, these geckos are perfectly suited to smaller accommodations. My colony, initially consisting of just 5 adults, was first housed in a converted 60 x 30 x 30cm aquarium, allowing space for when they started producing offspring. This was furnished with flat rocks stacked in naturalistic formations and twisted wood roots, creating natural refuges and a range of basking opportunities to allow for effective thermoregulation. A sandy or rocky substrate is most

representative of their natural habitat and is used to allow for natural behaviours, as well as offering the ideal egglaying medium.

With little information available on their captive needs at the time, I used reference images of the natural environment, a habit I’ve now taken to with all my setups. Naturally, Tropiocolotes will spend much of the day concealed in rock faces and hidden from the scorching sunlight, revealing themselves as the day cools, to feed and bask. From captive observations, I find the geckos are active most in the early morning and the evening unless food is offered during the day, which is unsurprising given their adaptation to such a harsh environment.

9 MAY 2024 Micro Marvels: Keeping Sand Geckos

©Alistair Gamblin

Heating and lighting

Heating and UVB lighting are vital for the health of these arid reptiles that experience consistently high daytime temperatures in the wild. I began to keep our group at the cooler end of the accepted range (providing a basking spot of around 35°C) but found that, whilst they survived and could live happily at this temperature, they never truly thrived, and never produced eggs. I decided to swap out to a more powerful incandescent bulb and set the thermostat to provide a basking temperature of 40°C, with the overall daytime temperature gradient cooling to around 25°C. Providing a night-time temperature in the mid to low 20s is ideal. This range is much easier to maintain in a larger setup and with overhead heating. For the species to thrive I do not believe that a heat mat would be at all suitable.

I believe UVB lighting, as with any reptile, is important for the overall health of these geckos. I achieve this with a 10% T5 bulb, which is controlled by a Wi-Fi timer on a 12-hour on/12-hour off cycle.

Each morning, I lightly mist the tank, ensuring that droplets form for the geckos to drink from. This simulates the naturally occurring dew in arid environments and seems to be these gecko’s preferred drinking method. The remainder of the time, the tank is kept at 30 - 40% humidity, except for a few humid pockets to aid shedding. Providing a water bowl is optional but recommended. Extreme care must be taken to ensure that the water isn’t too deep, and I often fill the bowl with marbles or pebbles to prevent drowning.

Diet and feeding

With a voracious appetite and a rapid metabolism (a side effect of being so small), these geckos will happily take a variety of small live foods at any opportunity. I primarily offer flightless fruit flies and micro crickets, although they are more than capable of taking larger feed items up to the size of their heads. I feed every other day, supplementing on a rotation of calcium and mixed vitamins. These are vital for the health of all captive reptiles and certainly for Tropiocolotes

I have observed Tropiocolotes using two hunting methods: sit-and-wait, in which they do just that, waiting motionless for prey to pass, or actively hunting down their food. It is surprising just how far these geckos will go to catch their food, with many performing elaborate stunts and pulling off daring climbs for their meals.

Behaviour

Tropiocolotes are social and do best when housed in groups. There are no specific requirements for group sizes and sex ratios and multiple males can be safely kept together without the need to worry. I have never once observed any form of physical aggression in these geckosinstead, they seem to prefer to work out their differences in a more peaceful manner. Dominance is thought to be shown through body language, where the dominating male will raise himself with straightened legs to appear taller and larger than his opponent. Males will also ‘chirp’ in the evenings, more so in the breeding season, which helps them to regulate their territories and attract a female.

10 MAY 2024

©Alistair Gamblin

Micro Marvels: Keeping Sand Geckos

Dan_Koleska/Shutterstock.com

My personal favourite behaviour in these geckos is their thoughtful, slow sways of the tail, often associated with hunting and avoiding threats.

Breeding in captivity

As a result of their basic requirements and undemanding social needs, breeding these geckos in captivity is incredibly simple. Most keepers will have more difficulty in trying to get them to stop breeding!

In their first breeding season, my 5 adults produced an unbelievable 14 offspring! As mentioned previously, supplementing the diet is vital, and becomes even more important in the breeding cycle to help avoid complications in females and to ensure the health of the egg.

Typically, females will lay a single egg (this is quite large compared to their tiny body and can be seen before laying) every few weeks during the breeding season, which will then take 60 to 80 days to hatch. As with any eggs, the exact duration of hatching will be heavily dependent on the incubation parameters. Some keepers opt to artificially incubate the eggs; however, I have always decided to leave eggs. Through this method, I have only ever lost 1 egg caused by complications when hatching. Once the eggs from the season have hatched and the winter period

draws closer, a small decrease in temperature of just a few degrees can be made to create seasonal cycles and promote a period of rest before the next season.

To rear the young, I leave them in the main enclosure alongside the parents. I believe allowing the offspring to interact with others of their species is highly beneficial, although a few alterations may be needed to maintain routine husbandry. A variety of feed types and sizes must be offered so each of the individuals, no matter their life stage, can eat, and extra care will need to be taken to protect offspring from any bodies of water, which pose a risk of drowning. Even newly hatched geckos are confident and active and are more than capable of catching their food in a large and competitive communal tank.

Conclusion

To end, I would like to reiterate just how amazing this species is: easy to care for, easy to breed, and an absolute joy to watch. Whilst many will overlook these underrated reptiles due to their basic needs, I honestly believe these geckos should be found in the collection of every exotics keeper. I would also like to thank the team at Southern Aquatics and Pets for their help in tracking down some T. steudneri and their support in species identification.

11 MAY 2024

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

The wonderful world of exotic animals

Egyptian tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni)

Testudo kleinmanni is the smallest species in the Testudo genus. Sometimes referred to as the “Kleinmann’s” or “Leith’s” tortoise, the species is most known as the “Egyptian tortoise.” This Critically Endangered species was once found across Egypt, Libya, Israel and Palestine. However, it is now restricted to a few coastal regions of Egypt and Libya. This is partly due to rampant overcollection for the pet trade in the 80s and 90s and therefore, every concerted breeding effort may be valuable for the preservation of this species.

Coming from arid coastal areas of the Middle East, the Egyptian tortoise is quite cold-tolerant in captivity, opting to aestivate if temperatures get too hot (+35℃). In fact, the Egyptian tortoise may be the only temperate tortoise species that increases its activity in winter and decreases in summer.

17 - 24℃ is reported to be an optimal winter ambient temperature with access to a basking spot of around 32℃. In summer, the basking spot can be increased above 38℃. However, this may result in animals going into aestivation which, unlike hibernacula, is difficult to maintain consistently for several months. This leads some keepers to maintain a steady climate year-round and reportedly has no ill effects.

Enclosures should be large enough to allow the animals to explore but, given their small size, is perhaps more manageable than the enclosures of other Testudo species. There are suitable indoor and outdoor options, but given that the Egyptian tortoise occupies habitats further removed from European gardens, a combination of the two is likely to be best.

Egyptian tortoises mate in the Autumn and lay their clutch in Spring. Interestingly, the clutches are extremely small and usually consist of just one egg (but up to four). Incubation can take up to four months and hatchling tortoises can live up to 100 years old!

reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

Species Spotlight

NutriRep™ is a complete calcium, vitamin & mineral balancing supplement with D3.

It can be dusted onto all food sources including insects, meats & vegetables. No other supplement is required.

SOME ISSUES ARE MORE THAN SKIN DEEP

Exploring snake dermatology with Dr Michaela Betts.

dangdumrong/Shutterstock.com

FEATURE

FLASHBACK

Skin complaints are one of the most common reasons captive reptiles present to veterinary practice and snakes are no exception to this. Reptilian skin differs drastically from mammalian or avian skin in both its structure and physiology, and unfortunately many of the problems that arise are related to insufficient husbandry.

Common skin problems of snakes include difficulty shedding (including retained spectacles), parasitic disease, burn injuries, and cancerous changes. However, skin changes from fungal and bacterial infections, viral infection, and other abnormal skin complaints can be seen. In countries outside of the United Kingdom where feeding of live vertebrate prey to snakes may be legal, bite wounds from prey and related subcutaneous abscessation is also commonly reported.

Reptilian Skin

The skin of reptiles consists of two layers: the underlying dermis and the outer epidermis. This epidermis is then covered with keratins. The scales represent a folding of this epidermis and they cover almost all of the reptile skin. Snakes have the greatest folding seen in reptiles where adjacent scales overlap with each other and join through a flexible hinge region at the caudal end. Reptile skin contains relatively few glands compared to other species and is generally dry to the touch. Snakes possess paired anal scent glands at the base of their cloaca.

Boas, pythons, and vipers possess specialised labial pits that can sense infrared radiation and help with the location and consequent apprehension of prey. For boas and pythons, these pits are located along the edges of the labial scales

and cover almost the entirety of the upper or lower lip. In vipers, these are instead focused in a forward-facing direction mid-way between the nostril and eye bilaterally.

Shedding

Reptiles periodically slough and renew their skin in a process known as ‘ecdysis’. In snakes this process is cyclical and one in which they should shed the entire skin at once, usually as a complete skin rather than patches. Regardless of species, this process appears to be influenced hormonally through the animal’s pituitary-thyroid axis, and the rate of shedding may be influenced by age, temperature, humidity, photoperiod, ectoparasites, frequency and volume of feeding, and on the animal’s general health condition.

16 MAY 2024

Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

About the author: Michaela graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in 2018 with a degree in Veterinary Medicine. She initially worked with small animal, exotic, and wildlife species before spending 2 years at Suffolk Exotic Vets as a first opinion and referral exotic animal clinician. She currently works as a research assistant in pathobiology and population sciences at the Royal Veterinary College and as a small animal and exotic species veterinary surgeon. Alongside this, Michaela is an educational speaker for Just Exotics, providing further education in exotic animals to other veterinary professionals, and is a member of the British Veterinary Zoological Society and Association of Exotic Mammal Veterinarians. She is currently completing her RCVS Certificate of Advanced Practitioner in Zoological Medicine.

The ecdysis cycle itself is divided into five stages of renewal and then a resting phase.

The resting phase follows a slough and is where the skin is in its normal state: a complete epidermis with no cellular proliferation nor differentiation.

The renewal phase begins by cellular activity in the epidermis. Cells begin to migrate and differentiate into new outer layers. Once the “old” skin is ready to be replaced, lymphatic fluid

then enzymaticaly digests the bonds holding the older skin to the newer underneath, and at this time the snake may appear to have a blue hue in colour or appear more dull. The skin then starts to detach, typically from around the eyes, mouth, and nostrils, and the skin can be shed in its entirety. The new layers undergo a brief period of drying and maturation as the keratin stiffens. Keepers can evaluate the shed skin to determine if a shed was complete, particularly if spectacle were successfully removed.

Impact of Husbandry on Skin Health

The way a snake is kept will have an impact on its overall health. All species should be housed in appropriately sized enclosures with adequate ventilation and insulation, and the correct heat, humidity, and lighting for the specific species. Substrate, enrichment, and nutrition also needs to be appropriate for the individual. Insufficient or inappropriate husbandry, such as lack of hides, will increase a snake’s stress

17 MAY 2024

An example of a healthy slough by a royal python (Python regius).

Lamnoi Manas/Shutterstock.com

levels, which can contribute to immunosuppression and consequent development of disease.

Enclosures should not contain any crevices or corners that prevent adequate cleaning. Regular spot- and deep-cleaning should be undertaken with soiled substrate always being replaced. Organic matter such as excrement can inactivate disinfectants. A thorough clean of surfaces and in-contact items with a mild detergent such as warm soapy water should be used to initially clean before application of a reptile-safe disinfectant for the appropriate contact time as advised by the manufacturer. Substrate should be absorbent and non-toxic, and care taken that it not become waterlogged. Soil and peat can be difficult as they may carry a high microorganism load compared to other substrates. Moist unsanitary substrate encourages bacterial growth and increases the likelihood of secondary bacterial infection.

A water bowl should be provided that is large enough for the snake to bathe in and should be changed with fresh water daily. Abrasive objects such as rocks can help to assist with shedding but there shouldn’t be any sharp edges that could cause trauma to the skin.

Snakes rely on environmental heat sources to maintain their body temperature. It is important that their enclosure is within their optimum temperature zone and provides an adequate heat gradient so that they have a hot dry, hot humid, cool dry, and cool humid microclimate within their set-up. Radiant heat sources should be covered with a cage or guard to minimise the risk of thermal injury, and items like heat rocks and underfloor heat mats within the enclosure should be avoided. Thermometers should be placed at the hot and cool ends of the enclosure as a minimum, and ideally minimum-maximum thermometers should be used to identify any fluctuations in temperature throughout the day. Inappropriately high temperatures can lead to death by dehydration and overheating and contribute to difficulty shedding. Conversely,

inappropriately low temperatures will lead to a reduced metabolism which can lead to reduced sloughing of shed skin and an increased susceptibility for opportunistic infections of the skin and other organ systems.

As well as heat, it’s important for snakes to also be provided with an adequate photoperiod as daylight length, temperatures, and relative humidity all feed signals about the “season” to the snake and can have an impact on shedding.

Humidity also has an impact on themoregulation. Less humid enclosures trap less heat and are more likely to experience temperature fluctuations, particularly overnight, whilst more humid enclosures are more likely to result in dampness to the substrate. Appropriate ventilation is key to help maintain appropriate humidity. Within a set-up, a hygrometer should be used to monitor the environmental humidity, ideally in each of the microclimates within the set-up. Inappropriately low humidity contributes to dehydration and trouble with shedding, whilst inappropriately high humidity alongside poor environmental hygiene can contribute to secondary or opportunistic bacterial infection. Humidity may be increased or decreased within an enclosure through misting or providing a greater or smaller water surface area for a water container near a heat source.

Dysecdysis

The term “dysecdysis” describes the abnormal or impaired shedding of the outer layers of the epidermis and is one of the most common conditions affecting reptile skin. For snakes, this refers specifically to the failure of the whole shed to come away in a single attempt.

Despite its common presentation, dysecdysis should be considered a nonspecific clinical sign as it is associated with a vast number of potential underlying issues, including trauma that affects the normal shedding process,

19 MAY 2024

A large Eastern Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) with blue or opaque eyes, about to shed its skin.

Matt Jeppson/Shutterstock.com

nutritional deficiencies, dehydration, infectious disease, inappropriate humidity or temperature, and a lack of appropriate materials within the set-up to facilitate a shed.

Low environmental relative humidity can lead to dehydration of the sloughed skin in the short-term, not just of the snake itself in the long-term. Temporarily increasing the environmental humidity at the time of ecdysis can sometimes help to remove the slough. In the author’s experience, 20-30 minute soaks in warm, shallow water often proves sufficient for amenable snake patients, and encouragement to gently move over wet abrasive surfaces such as a damp towel. However, the underlying reason for the condition should always be investigated.

Once the primary problem has been identified and treated, normal shedding should usually return within two or three cycles and, if caught early, most snakes have an excellent chance of making a full recovery. Optimal husbandry practices for the species and the elimination or prompt treatment of any condition that may interfere with the normal shedding process are key to its prevention.

Retained Spectacle

Retention of the ocular spectacle can occur in snakes undergoing difficult shedding, either attached to retained slough over the head of the snake or of the spectacles only. Typically it has a wrinkled and slightly opaque appearance, but it is important to not confuse this with a dehydrated spectacle, a normal spectacle with previous

ocular damage, or the slightly duller appearance of royal python (Python regius) spectacles compared to some other snakes. The more layers retained, the easier to identify but also the more challenging to remove. However, examining the shed for the spectacle is a good way to assess in the absence of slit-lamp illumination at home. The most common cause tends to be inappropriately low environmental humidity or dehydration, but systemic disease, ectoparasitism, and malnutrition may also be contributory factors.

Gentle soaking of the area in warm water and application of moist cotton buds from the canthi towards the centre of the eye can help to remove retained spectacles. Extreme caution must be taken to not damage the underlying spectacle as doing so can lead to eventual loss of the eye. Sometimes this method is insufficient and veterinary attention may be indicated and medications prescribed to help soften the spectacle and then removal re-attempted.

A Note on Hyperthyroidism

An increase in the frequency of ecdysis may be an indication of a systemic disease process in snakes, including hormonal issues. In older snakes, particularly cornsnakes, hyperthyroidism is a reported endocrinopathy. This may be due to enlargement of the thyroid gland due to hyperplasia or neoplasia. An ecdysis cycle may be observed as frequently as every two weeks in affected snakes. Other associated signs with this condition include increased aggression, increased appetite, and muscle wastage.

20 MAY 2024

An example of a blue form of white-lipped pit viper (Trimeresurus insularis).

Kurit afshen/Shutterstock.com

Burns

Thermal burns are a frequent reason for snakes to present to veterinary practice and tend to be due to device malfunction or the use of inappropriate heat devices. Reptiles have been suggested to not have the same withdrawal reflex as mammals and may not recognise that a heat source is burning their skin. Regardless, their lack of moving away from or off of heat devices actively causing their skin thermal damage is well reported. As such, reptiles should never be allowed direct access to heat sources. For this reason, hot rocks/logs and heat mats underneath or inside of enclosures are not recommended, and where possible heat lamps should be placed outside of enclosures. However, if not possible then a protective cage or guard should be placed around the heat source that the snake is unable to get into.

Burns can range from very mild to life threatening in severity and are classified based on the depth of damaged tissue as first-degree, second-degree, third-degree, and fourth-degree. A cold compress can be applied for 15-20 minutes to help reduce further burning and tissue swelling but then veterinary advice should be sought.

First and second degree burns have a reasonable prognosis if treated promptly and appropriately, and tend to take 4-8 weeks to heal. For second-degree burns there is often scar development which may be a source of dysecdysis going forward. Topical therapy and analgesia will be indicated in most cases, as well as support for any shock the snake may be in. For burns more severe than superficial, daily bandage changes, surgical debridement of damaged tissue, and systemic antibiotics to prevent septicaemia may be indicated, and healing will be prolonged over months. In severe cases, euthanasia may be the only option.

It is vitally important to remember that the full extent

of a burn injury may not become apparent until days or even a week after the initial incident, and so despite treatment may start to look worse before it starts to look better. It is also important to be aware that burn injuries typically result in significant protein and fluid loss and so nutritional and fluid support may be needed to prevent hypoproteinaemia and dehydration.

Ectoparasites

Snake mites (Ophionyssus natricis) are the most commonly observed ectoparasites seen and will infest any snake species as well as some lizards. They can often be observed around the spectacle and gular folds or in the environment, particularly dark moist places such as vivarium joints. Mites pose an issue not just from irritation and swelling to the skin, but can also lead to secondary bacterial infection where the skin has been compromised as well as the transmission of viral diseases. Affected snakes may spend more time soaking in their water bowl, which is thought to provide some temporary relief.

Elimination of mites can prove troublesome as they only spend part of their life cycle on the snake, and the rest in the environment. As such, successful treatment requires both treatment of the host with an appropriate anti-parasitic and treatment of the environment in order to break the life cycle. This often requires repeated application at set intervals. Care must be taken to ensure adequate ventilation, rinsing, and drying to reduce the risk of toxicity from antiparasitic residues.

New snakes entering a collection should be quarantined separately for at least 3 months and examined for mites to help avoid introduction into a pre-existing mite-free collection. All set-ups, including furnishings, used for quarantined animals should be sanitised thoroughly between occupants and only used for quarantined snakes.

21 MAY 2024

Ticks attached to the skin of a wild snake.

mogrzewalska/Shutterstock.com Some Issues Are More Than Skin Deep

Sibons photography/Shutterstock.com

Vesicular Dermatitis

Also known as “scale rot” or “blister disease”, this is a particular form of bacterial infection that tends to be associated with poor environmental conditions, particularly inappropriately high humidity and damp, dirty substrate. Natricine snakes appear to be more frequently affected.

The skin lesions tend to start on the underside of the body but can spread elsewhere. Systemic antibiotics based on culture and sensitivity testing, as well as topical therapies and sometimes analgesia and fluid support may be required in these cases. Similar to burns, prognosis and recovery time are dependent on the depth and extent of lesions. Correction of contributing environmental factors is critically important to prevent recurrence.

Systemic Diseases and Neoplasia

Underlying health conditions or diseases affecting one or multiple internal organs may present as noticeable skin changes. This may be due to the underlying issue directly, or due to secondary opportunistic infection whilst the snake is immunocompromised.

Some of the signs to look out for include:

• Weight loss and muscle wastage may result in the loss of skin elasticity which may be noted alongside an

increase in the number of skin folds. Dehydration can also cause a lack of skin elasticity as well as a tightening of the skin.

• Skin swelling and fluid build-up may be noted in cases of heart disease or neoplasia where the circulation system has become affected. Swelling may also be noted in cases of protein loss.

• Patches or diffuse discolouration of pink or red or yellow may be noted in cases of septicaemia, particularly on the underside of the snake in the interscalar region where the keratin layers are thinnest.

• Tumours are reported in captive snakes, which may present as noticeable lumps on the skin itself or swelling in the region of an internal mass.

Conclusion

Dermatological conditions in snakes are a common reason for them to be presented to veterinary practice. Optimal husbandry for the species, appropriate quarantine measures, and prompt identification and treatment of underlying contributing factors are all key in both preventing skin issues and rapidly and successfully improving treatable conditions.

22 MAY 2024

Green bush rat snake (Gonyosoma prasina)

100% NATURAL PEST CONTROL

TAURRUS® is a living organism (predatory mite) that is a natural enemy of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis).

TAURRUS® mite predators are very small, measuring less than 1mm as adults. They are able to live for several weeks and reproduce in the areas where they find their prey. Despite its small size, the TAURRUS® predator acts aggressively and is able to attack and kill preys 3 to 4 times larger than itself.

Once released, the microscopic predators will actively seek and consume parasites. Once eliminated, the predators disappear naturally. The mode of action requires several days. After introduction of TAURRUS®, pest populations should be monitored: at first it will stabilize, and then gradually decline. In heavy infestations, several releases may be needed to eradicate all parasites.

23 MAY 2024 OCTOBER 2023

JacobLoyacano/Shutterstock.com

ACKIES IN THE OUTBACK

Natural history, habitat and care requirements of Varanus acanthurus.

Varanus acanthurus is a small species of monitor lizard belonging to the Odatria subgenus; a group colloquially known as “pygmy monitors”. Found across an enormous range throughout Australia, the “ackie” is an extremely hardy species that can thrive in temperatures exceeding 50℃ and tolerate extreme temperature drops at night and in the winter months in some parts of their range. These characteristics have made the species extremely popular in captivity. Whilst these lizards are extremely hardy, it is important to reconsider their captive requirements consistently to improve husbandry standards. The following feature aims to discuss their natural history, habitat and care requirements using wild observations.

Habitat

Ackie monitors are found across most of the arid regions of North and Central Australia. There is some phenotypic variation across their range. Animals from the north are known as “topenders” and have a dorsal stripe that runs the length of their spine, animals from the west have greater red pigmentation and are known as “reds” and animals from the east have greater yellow pigmentation and are known as “yellows”. As there have been no legal exports of this species, genetic variation is extremely limited now and therefore most captive specimens have mixed heritage. Genetic analysis has confirmed that “reds”, “yellows” and “topenders” are all the same species, despite the yellow ackie once being considered

a subspecies. It does, however, make it difficult to paint an accurate picture of the precise habitat that an “ackie” occupies, as the conditions that “topenders” are subject to, will be different to the conditions that “reds” face. However, their preferred habitat remains similar.

Ackie monitors live in rocky outcrops in desolate regions. Whilst they can be found in small rural towns and are surprisingly well adapted to living alongside people, ackie monitors generally inhabit the harshest conditions imaginable. Their spiny tails are used as a defence to protect their body as they wedge themselves between rocks. It would be unusual for an ackie to inhabit a

26 MAY 2024 In The Wild: Ackie Monitors

sandy environment (or anything that mimics most of the substrates available on the market today). Instead, hard gravel and clay soil with a large pile of rocks and a fake background will mimic their preferred habitat much better. This is far removed from the “a beardie set up but hotter” status quo that many ackie monitor keepers provide.

Amongst the rocks, spinifex and other desert grasses grow. It is also possible to find hatchling ackie monitors in cavities at the base of trees. This is likely because they have sought out the coolest place they can find, after hatching from their burrows.

Ackies climb, but only in the sense that a small lizard must climb over rocks to traverse its environment and scaling a two-, three-, or four-foot rock to reach a desired location is no problem for this species. Therefore, providing height within an enclosure is far less necessary for this species than for other arid reptiles that utilise perches to bask. However, the extra height in the vivarium will make it much easier for the keeper to provide extreme temperature gradients without reaching stress-inducing ambient heat.

The pile of rocks should ideally be created in a way that prevents collapses, especially for young lizards. If loose substrate is used, try creating a platform beneath the rocks, that holds them in position but can be filled with substrate. This will allow the lizard to burrow beneath the rocks, without dangerously dislodging them. Of course, commercially available slate offers a lightweight alternative to large boulders and can be stacked in creative ways to create an interesting three-dimensional habitat.

Diet

Emerging research suggests that captive Odatria monitors, including Varanus acanthurus, are genetically predisposed to gout. This becomes less surprising when one analyses the habitat of these lizards and the conditions in which gout is exacerbated.

Anecdotal reports of gout arising from feeding an ackie with just one pinkie mouse may sound extreme, but it does happen. In the wild, Varanus acanthurus will prey almost exclusively on invertebrates and the occasional lizard.

27 MAY 2024

In The Wild: Ackie Monitors

Even a slight fluctuation in elevation can create valuable microclimates ©Thomas Marriott

Stomach content analyses of 127 museum samples found the following breakdown of diet:

• Grasshoppers (Orthoptera): 44%

• Beetles (Coleoptera): 17%

• Unidentified insects: 9%

• Lizards (Agamidae, Scincidae, Gekkonidae): 7%

• Cockroaches (Dictyoptera-Blattaria): 6%

The analyses also found that egg cases (3%), spiders (3%) and isopods (3%) also played a role in the diet of Varanus acanthurus. Only a single trace of an unidentified carrion could be linked to an example of an ackie eating a mammal. Plant material was found in the stomachs of 15% of all specimens studied, but understanding the percentage of total items within the stomach was impossible.

Sadly, a dominant narrative focusing on what captive monitors will eat “most readily” in captivity has drawn keepers away from providing a natural diet. It is perhaps unsurprising that a captive lizard will feed on fragrant dog food and raw meat before having to search for its food. Furthermore, ackie monitors inhabit harsh environments that require them to opportunistically feed, even if their daily calorific requirements have been met. Anthropomorphising animals to “enjoy” a particular food item and feeding it excessively as a means to interact with the lizard is a potentially damaging practice.

Ackie monitors require low-protein, high-calcium foods. This means that “gut-loading” prey items is essential for the animals’ well-being, perhaps even more so than other reptiles. Providing variety in the sizing of locusts and species of crickets should help encourage enrichment. Cockroaches are slightly higher in protein and should only be fed sparingly.

Seasonality

Northern and western Ackie monitors will experience a rather extreme “wet season” from November to February. Central ackies will see some temperature change but ultimately receive perhaps just a few days of rain a year. This can lead to some confusion around the provision of water or artificial “rain”. One thing that is present in all ackie monitor habitats is a humid burrow that the lizard can retreat to if necessary (anecdotal evidence suggests these burrows reach 90% humidity). Unfortunately, it is not easy to provide this in the confines of a terrarium.

A paper published in the Responsible Herpetoculture Journal by Eric Los Camp in 2024 analysed the ways that most keepers maintain their ackie monitors. He writes “V. acanthurus were observed to obtain 70% of their water from pulmocutaneous exchange, and in the wild were noted to excavate burrows as deep as 0,8-2,7 m (2.6-8.8 ft), with individuals nesting at 0,4 m (1.3 ft) (Abou-Zahr, Calvo Carrasco, 2019; Doody et al., 2017). Substrate humidity and temperature need to be monitored with hygrometers and thermostats…”

“Of the Odatria with humidity data available (n=12), nearly all had humidities averaging around 50%, with fluctuations between 30-70% being observed. However, while the drier portions of this humidity range may reflect the ambient humidity in the native ranges of Odatria, it does not take into account the microhabitats these animals utilize. This is seen in a variety of species, as V. acanthurus use escarpments and gorges as mesic refugia and V. tristis use the spaces under concrete slabs and water tanks for the same purpose (Mendyk et al., 2012; Pavón-Vázquez et al., 2022; Thompson, Pianka, 1999)…”

“When these reptiles are housed in low-humidity environments, it causes chronic dehydration which predisposes animals to gout (O'Malley, 2017). Regardless of enclosure size and the ability for the enclosure to support

28 MAY 2024

Ackie Monitors

In The Wild:

A “yellow” ackie monitor Ken Griffiths/Shutterstock.com

mesic microclimates, overall ambient humidity in enclosures should be elevated to 50-90% to ensure adequate hydration.”

In the wild, rain will fall during January and December. However, some keepers may wish to time their seasonality with British summer, during which, temperatures and daylight hours increase. Either way, timing the misting of an enclosure to coincide with the low atmospheric pressure of natural rainfall outside of the vivarium can be a helpful trick to reinforce natural biological cues.

Environmental Conditions

Suggesting that the everyday reptile keeper mimics the extreme heat of the Australian outback within their home would be considered dangerous at best. However, it is worth noting the limitations of our capacity to mimic wild conditions and the broad aversion to exposing our animals to conditions we, as humans, would not enjoy.

For example, the brightest sunlight creates 120,000 lux. Even the brightest LED strips positioned just centimetres away from an animal will struggle to emit half the brightness of sunlight. This suggests that all keepers of all arid species (particularly those from outback Australia) should do everything they can to increase the brightness of their vivarium. Using several LED strips or New Dawn lamps within a white vivarium can help increase this brightness. Provided that adequate shade, hides and burrows are available, a vivarium that may appear excessively bright is likely more natural than those that rely on a basking spot and a T5 to provide a full spectrum.

Whilst in Australia, we noted sand temperatures over 62℃. Although most species avoided these harsh temperatures, several Varanids were active. Furthermore, we found wild ackie monitors in ambient temperatures of 39℃. Whilst most activity was concentrated in the cooler mornings and evenings, most daytime temperatures (during summer) exceeded 45℃ with surface temperatures much higher. Considering most husbandry advice suggests a basking spot of 45-50℃, our suggestions (along with several other progressive herpetoculture platforms) would be to increase this to +65℃ and provide adequate space to ensure a “cool end” that drops significantly lower. The larger the vivarium, the easier it is for the keeper to provide these all-important gradients and microclimates. In fact, despite ackie monitors being reasonably-sized and highly active, perhaps our best guide for enclosure size comes from our ability to create an extremely hot, cool, and humid habitat within four walls. Most keepers could achieve this with basic considerations within an 8ft vivarium, whereas even the most experienced keepers may struggle to do something similar in a 5ft vivarium.

In a larger vivarium, it may also be possible to install live plants into the enclosure. Arid grasses offer sensory enrichment, shade and a place for feeder insects to disperse which maximises the lizards’ active hunting time. Dwarf blue grass (Festuca glauca) makes a great spinifex substitute, while sedge grasses (Carex sp.) are more readily available and adds more coverage in the damper areas of the enclosure. Using desert substrate and soil in

Chris Watson/Shutterstock.com

Chris Watson/Shutterstock.com

29 MAY 2024

Ackie monitors sometimes use trees to escape the harsh sun and hunt for insects

In The Wild: Ackie Monitors

the cooler, moister part of the enclosure, with gradually more and more gravel/rocks towards the hot end will help form important microclimates for the lizard.

Conclusion

Continuing our series of “In the Wild”, these notes have been created from wild observations, anecdotal

evidence and peer-reviewed literature to provide an exploration of the natural conditions that Varanus acanthurus experiences in the wild. By focusing on wild observations, we are able to tailor our keeping towards a more naturalistic and fulfilling methodology. Whilst no truly complete picture can be painted from periodical observations and studies, it is important to inspire new ideas from the wild as often as possible.

30 MAY 2024

In The Wild: Ackie Monitors

Author, Thomas Marriott in Ackie Monitor Habitat ©Thomas Marriott

31 MAY 2024

IN THE WILD: CRESTED GECKOS Expedition New Caledonia with Blue River Diets.

Suryanata/Shutterstock.com

Lauren

Last month, Exotics Keeper Magazine, in partnership with Blue River Diets, was asked to visit New Caledonia to conduct research and observations on the habitat and environmental conditions inhabited by wild crested geckos. Spread across the Isle of Pines and Grand Terre, the expedition aimed to paint a good picture of how best to care for captive crested geckos.

Getting to New Caledonia

New Caledonia is not easy to get to from Europe. Even though it is a French territory and the people of New Caledonia are French citizens, flight paths are not straightforward. Most travellers will have to pass through Paris, Singapore, Brisbane or Tokyo to reach this Pacific nation. New Caledonia is comprised of Grand Terre (the main island), Isle of Pines (off the south coast) and the Loyalty Islands (off the east coast), as well as many more tiny islands and islets.

There are three known populations of Correlophus ciliatus

One on Isle of Pines, one in Blue River Provincial Park and one at the base of Mount Dzumac on Grand Terre. The population on the Isle of Pines is known to be the strongest in terms of visibility for researchers and visitors. In fact “herping” on Grand Terre is notoriously difficult, which we would later find out.

Once in New Caledonia, we split our expedition into two parts; the Isle of Pines to search for crested geckos and

34 MAY 2024 In the Wild: Crested Geckos

In the Wild: Crested Geckos

other herpetofauna, and Grand Terre, where we explored Blue River Provincial Park to understand the parallels in habitats and populations of crested geckos on each island.

The Isle of Pines is a two-hour ferry ride south of Grand Terre and these ferries only run a few times a week. It is

possible to fly between Grand Terre and Isle of Pines, but with additional luggage fees, this works out to be an expensive endeavour. However, determined to find wild crested geckos and faced with extreme storms and a rather predictable bout of sea sickness, we made our way to Isle of Pines.

35 MAY 2024

Author, Thomas Marriott photographing a crested gecko ©Thomas Marriott

The Isle of Pines

The Isle of Pines (Ile de Pins) has several islands and islets around its main landform. Of course, when we first arrived we asked some local people about the geckos we were searching for and most had never seen any geckos on the island (perhaps unsurprising as they were missing to science for almost 150 years!). A few hotel staff mentioned Isla Brosse, a small island famed for its snorkelling, where it is also possible to find Rhacodactylus leachianus. However, there are no recorded Correlophus ciliatus on this island. R. leachianus, Mniaragekko chahoua and Eurodactylodes viellardii can be found on the Isle of Pines, however, Rhacodactylus auriculatus and Correlophus sarasinorum cannot. These species are found only on Grand Terre.

Ile de Moro, located a short boat ride from Isle of Pines also has a population of Rhacodactylus trachycephalus, that was rediscovered by Philippe de Vosjoli and Frank Fast in the 1990s. Other rare and endemic species on the neighbouring islands include Phoboscincus garnieri, a species that was thought to be extinct for decades until 1994 and the rare Phoboscincus bocourti

Our expedition was sponsored by Blue River Diets and therefore focused primarily on crested geckos. This meant we had to choose a specific search area.

Crested geckos are found between 1 – 4m off the ground in thin trees, whereas Chahouas are much more difficult to spot and usually rest 4 – 8m off the ground. I did keep my eyes peeled for Leachianus right up into the forest canopy, but the area where we had the most success in finding crested geckos did not have a tall canopy at all. Leachianus geckos will predate upon wild crested geckos and whilst some patches of forest are sure to have both species living sympatrically, searching forests with a greater density of shorter trees proved more successful in finding our target crested geckos.

Climate and Temperature

The New Caledonia expedition ran from 7th – 27th March. This is the height of the wet season. As any herpetology enthusiast knows, increased rain typically means increased reptile activity. Wet seasons are also usually warmer than dry seasons and tend to be when trees produce most fruit. Whilst the wet season was great for geckos, it was less than ideal for us and

sadly we received less than 2 hours of sunshine for the entire time spent searching for geckos. This ruled out any time spent on Isle of Pines’ pristine beaches, but did lead us to make some interesting observations.

Firstly, humidity levels fluctuated throughout the day and night, with no obvious or stark trajectory across 24 hours. This humidity rarely dropped below 85%. In fact, from 6am to around 10am humidity never dropped below 90%. From 11am until 3pm humidity typically dropped slightly, averaging around 80 – 85%. 3pm until 9pm was very sporadic, depending on the

Large epiphytic ferns can be found at all heights. These may provide refuge to sleeping geckos ©Thomas Marriott

36 MAY 2024 In the Wild: Crested Geckos

Breaks in the canopy allow sunlight to reach various layers within the forest ©Thomas Marriott

weather. From 9pm until 11pm, humidity generally stayed above 88% (reaching 95% during light showers). We expect that throughout the night, humidity remains high, resulting in our consistent morning readings.

Interestingly, temperatures gradually increased throughout the day and in some cases, into the night. Average daytime temperatures would sit at around 24℃. Mornings were a little cooler and afternoons and evenings could reach 28℃. On several occasions that we found crested geckos active at night, the temperatures sat at 26℃, which was warmer than the average daytime temperature of those days. Strangely, Isle of Pines saw ambient temperatures remain steady as the sun went down. This coincided with the optimal activity hours of crested geckos that were most frequently found between 8PM and 9PM (the sun would set at 6.20PM).

Perhaps the reason temperatures remain so steady during the rainy season in New Caledonia is that there is not much sunlight to have any bearing on surface temperatures or microhabitats. In fact, UVI retained a steady >0.5 for every single reading, apart from two very important measurements. The clouds broke for a brief window of around two hours on one morning on the Isle of Pines. During this window, we recorded 11UVI. This was on the 10th March at 11.40AM. Three hours later, we also found a crested gecko exposed and resting against a tree trunk in a patch of forest. The UVI at the resting point was only 0.5 by this time (and under the canopy cover), but as the only diurnally active gecko we found during the trip, it is interesting to consider a potential link between the observation and the conditions that morning.

37 MAY 2024

In the Wild: Crested Geckos

Creeping plants are not as common as in true rainforest, but still provide humid microhabitats and shelter

©Thomas Marriott

In the Wild: Crested Geckos

Rain, Wind and Captive Management

One thing I had not anticipated when visiting New Caledonia was the extent to which it rains. Rainfall is not restricted to intense downpours sandwiched between sunny spells like it is in most of the tropics. Instead, rainfall can last for days on end without stopping. Light rain brought in by dark clouds and dispersed across the central highlands of Grand Terre and the isolated Isle of Pines was unyielding throughout the expedition. Cast into the Pacific Ocean, clouds move rapidly across the islands and certainly throughout March (though the rainy season can last well into June) rain is almost constant. Personally, I experienced more rain on the New Caledonia expedition than any other travel (including Central and South America, Southeast Asia and Madagascar during rainy seasons). This would make me inclined to suggest that crested geckos (and other New Caledonian species) should receive hourly misting for at least three months of the year. A daily, light misting to maintain a high humidity is simply not representative of the wild habitats that they occupy.

The first crested geckos that ever entered the hobby came from the Isle of Pines. Whilst there are populations found at mid-altitude in the centre of Grand Terre, our best method of understanding the needs of captive crested geckos is to analyse those found on the Isle of Pines. These animals occupy coastal forests. These coastal forests are sparse with strong winds blowing through them. Strong sunlight shining through dense clouds and near-constant rainfall keeps ambient humidity high even when airflow is increased. Unfortunately, this is difficult to simulate in captivity as more ventilation will usually result in difficulties

maintaining high humidity. However, with a suitable misting system, it may be possible to replicate the coastal forest environments that wild crested geckos live in.

Movement

We found crested geckos during the day and night. The individual found during the day was resting on a large tree trunk (some herpetologists have found them in tree ferns during the day) but the others were using the trees (mostly yellow tulip trees) to navigate the understory at night. They would move small distances to the edge of branches, and then position themselves perpendicular to the branch to wait for prey. They are also very adept at jumping, suggesting that their tendency to leap from the grasp of a keeper is a natural behaviour that allows them to navigate the forest understory and escape predators, such as Leachianus geckos that are possibly too large to pursue a leaping crestie.

When alarmed, the geckos will move upwards into the canopy. At any height in the tree and irrespective of where the threat is coming from, the crested geckos that we observed, would always move upwards to evade perceived threats. It could be argued that crested geckos receive a greater sense of security in a taller enclosure with a denser canopy than a dedicated “hide”.

Crested geckos typically move slowly. As relatively largebodied lizards, this methodical movement is likely to be an adaptation to the reasonably cool conditions that they inhabit. Crested geckos were found higher in the trees

38 MAY 2024

The understory is filled with vines that allow the crested geckos to traverse the forest without entering the canopy layers ©Thomas Marriott

after dry conditions. After rainfall, storms or wind, they appear to move down to the 2 – 3-meter point, whereas on dry evenings they were found around 4 – 5 meters high.

Crested geckos were only found within large patches of forest (although most search efforts were focused there). We did not find them on forest edges, in gardens or anthropogenically altered habitats, in small patches of forests on accommodation grounds, or crossing roads. The search area was concentrated on the North and East coastal forests of the island. In these areas, the substrate was comprised mostly of dead coral and carbonate rocks (likely limestone) with a layer of decomposing plant matter and leaf litter. Soil was reasonably scarce. It may be possible that the limestone (a compound rich in calcium) substrate adds a calcium boost to the berries that grow within it. I am not a geologist or botanist, but similar effects happen to plants elsewhere in the world.

Flora & Fauna

Crested geckos live in tropical coastal deciduous forests. In the regions where we were finding crested geckos, most of the trees were limited to the following species: Grey boxwood (Drypetes deplanchei), Australian red cedar (Toona ciliata) and Australian tallowwood (Eucalyptus microcorys). Fig trees are also common in New Caledonia. They are extremely impressive and eye-catching and likely to be home to Leachainus geckos given their enormous size, but were not frequented by crested geckos in our experience.

Various creeping plants also covered the lower halves of the trees. Many of these are invasive or difficult to identify. However, we did record Cissus (Cissus repens) and Chilean bellflower (Lapageria rosea). Lots of vines and trailing branches, as well as fig trees, create a vertical environment. This allows crested geckos to easily navigate the understory layers as they move up and down robust vines.

Ground cover was extremely diverse, although the most populous and eye-catching were Cook’s pine (Araucaria columnaris), Monarch fern (Phymatosorus scolopendria), Ipil-ipil (Leucaena leucocephala), birdnest fern (Asplenium serratum), branched comb fern (Schizaea dichotoma) and various schefflera-like plants (which are used as resting places for smaller geckos). How often crested geckos will physically encounter this low-lying vegetation is hard to tell. However, it could be incorporated into an extremely tall vivarium to simulate the forest floor.

At night, insects were abundant. Crickets would sit and the end of leaves, cicadas were extremely common and became a nuisance under torchlight and various flies and small moths

39 MAY 2024 In the Wild: Crested Geckos

The crested gecko has evolved to leap between branches

©Thomas Marriott

were also highly visible. Perhaps these are the most obvious insects for us to observe as they are attracted by lights, but the crickets and katydids were seemingly more populous than spiders, beetles or soft-bodied worms and caterpillars. Giant snails are also extremely common on the Isle of Pines, and while they are primarily terrestrial, juvenile snails could be found on tree trunks feeding on creeping plants. It is well documented that arboreal geckos that are fed on young snails typically produce healthier clutches of eggs thanks to the natural calcium in the shell and the fat and moisture in the body. It would be interesting to investigate further whether snails make up part of a crested gecko’s diet and if so, whether captive breeding collections are likely to benefit from snails being incorporated into their diets.

Invasive rats and domestic cats were a common sight on Isle of Pines. Two female geckos found on the island had suffered trauma to their eyes. Whilst it is difficult to say exactly why this was, predatory rats, hungry electric ants and curious cats could all have a role to play. Sadly these threats do pose a significant risk to the continuation of remote island populations such as the Correlophus ciliatus on Isle of Pines. Currently, the species is listed as Threatened by the IUCN. This is largely due to the fragility of island populations and the small number of individual populations left on Earth. Whilst one population does occur within protected areas within the Blue River Provincial Park boundaries, the geckos on Isle of Pines and Mount Dzumac may be susceptible to exploitation.

The most common species found living sympatrically with crested geckos are the very common forest bavaiya (Bavaiya cyclura), the green-bellied tree skink (Epibator nigrofasciolatus) and the common litter skink (Caledoniscincus austrocaledonicus). Records show that Viellard’s chameleon geckos (Eurydactylodes viellardii) can also be found in the ground cover of crested gecko habitat but unfortunately, we did not observe this species on this expedition. All these species are endemic to New Caledonia. The most reptile diversity within a particular group is the sea snakes. There are over a dozen species of sea snakes and kraits that frequent New Caledonia’s coral reefs.

Diets

It is extremely difficult to paint a holistic image of the natural diets of a species without conducting invasive research techniques such as stomach content analyses. However, our observations suggest that ripened berries may make up a significant part of the crested gecko’s diet. Furthermore, extremely fragrant fruits such as cheese fruit and figs are common in the forest, whereas other fruits are reasonably rare. We did not find concentrations of geckos on fruiting trees, nor did we find crested geckos crossing anthropogenically altered habitats to feed on cultivated fruits. This may suggest that they are moving through the forest understory, feeding on a variety of sweet-smelling foodstuffs, such as ripe fruit, overripe berries, nectar-rich flowers and more. This matches with stomach content analyses from other researchers’ studies. Blue River Diets is currently assessing all the flora that we documented to help create even more naturalistic formulas for their product range.

Special thanks

Exotics Keeper Magazine would like to thank Blue River Diets for the opportunity to investigate the natural habitat of one of the world’s most famous yet mysterious lizards. The New Caledonia Expedition was sponsored by Blue River Diets.

40 MAY 2024

In the Wild: Crested Geckos

©Thomas Marriott

Leaflitter gathers in the fern axels

©Thomas Marriott

Crested Gecko Myths Busted

Myth: Crested geckos are strictly nocturnal.

Truth: Anecdotal evidence suggests that crested geckos will often cryptically bask within low vegetation and can often be seen during the day.

Myth: Crested geckos need an enclosure filled with artificial broad-leaved plants.

Truth: Crested geckos are often found in the complex trunk systems of fig trees, within shrubs and bushes and occupy landscapes characterized by coniferous trees.

Myth: Crested geckos need a steady “room” temperature and a consistent humidity of 60-70%.

Truth: New Caledonia experiences vastly different seasons that are not always easy to replicate. The wet season is the warmest with the lowest levels of UVI and the highest rainfall. The dry season is far cooler, UVI is higher and there is less rainfall. Humidity in the wet season is almost constantly above 90%, whilst in the dry season it may drop to 70%.

Myth: Crested geckos live in the rainforest.

Truth: The first crested geckos to enter captivity came from a small coastal population. The forest here is sparse. Except for some fig trees, most vegetation is slender. The substrate is comprised largely of coral remnants and limestone that are not mineral-rich enough to support the flora diversity of other tropical biotopes.

Myth: Crested geckos come in all colours and patterns.

Truth: Crested geckos are not that variable in the wild. Some animals will have more green hues, others will have faint white markings, and many also have red dots on their flanks. However, these are not known to be locality forms, meaning selective breeding is the only way to produce “morphs”.

41 MAY 2024 In the Wild: Crested Geckos

A wild crested gecko smiles for the camera ©Thomas Marriott

Myth: Crested geckos only eat fresh fruit.

Truth: Crested geckos eat pollen, insects and other geckos in the wild. They also eat a considerable amount of berries and seeds. We found a far greater abundance of berries in New Caledonia, than fruit. Crested geckos will also feed mostly on wild, tropical fruits, rather than crossing into anthropogenically altered habitats.

Myth: If cresties/leachies eat lizards, I can feed mine with a pinky.

Truth: Reptiles and mammals have extremely different nutritional profiles. Some lizards that eat a diet comprised of other lizards can fall victim to gout from a single feed from a pinkie mouse. Never assume that because a species eats vertebrate prey in the wild, frozen thawed rodents must be a good alternative.

Myth: Crested geckos can be housed comfortably in a 45x45x45

Truth: We don’t know the true range of a crested gecko in the wild, but a typical “territory” will likely be much larger. Our observations suggest that crested geckos move methodically through the understory layers of the forest. We did not find a single animal twice, suggesting they do not stay restricted to a single area. If this is true, changing the enclosure layout and adding enrichment opportunities is extremely important in captivity.

Myth: Crested geckos don’t require temperature gradients

Truth: Interestingly, cloudy weather in New Caledonia showed reasonably steady environmental readings throughout the expedition. Perhaps this is why crested geckos are so well suited to captivity. However, wild crested geckos will have access to many more microhabitats that they can choose to inhabit, than in captivity. This means gradients and choice within captivity are still important, even if the wild is surprisingly stable.

Myth: Crested geckos only eat their favourite bugs in the wild.

Truth: Wild animals can’t be picky. We will be uncovering which insects, arachnids and other arthropod species are most abundant in the area and suggest which widely available feeder insects could make a good substitute.

Myth: Bee pollen is just the next “fad”

Truth: Pollen makes up a percentage of many insectivorous reptile diets, even if it is just by accidentally consuming it. Arboreal species will eat a wide range of pollinating insects. Frugivorous reptiles may eat pollen when consuming sweet flowers (many tropical flowers have sweet nectar or leaves). Pollen contains a wide range of antioxidants and minerals and essentially “dust” the wild prey with beneficial trace elements and antioxidants.

42 MAY 2024 In the Wild: Crested Geckos

Lauren Suryanata/Shutterstock.com

43 MAY 2024

You Little Ripper!

ARE YOU TORTOISE RED-Y?

The complete guide to red-footed tortoise care.

seasoning_17/Shutterstock.com

The red-footed tortoise is, according to our data, the third most popular pet tortoise in the UK. It, along with its relative the yellow-footed tortoise, has some of the most unique husbandry requirements of all the readily available tortoise species. Not only does it inhabit the Amazon rainforest, but it also eats tropical fruits and a surprising amount of meat and bone. If a keeper inherits, misidentifies or simply falls behind on husbandry standards of their “red foot” it could cause serious problems.

Natural History

The red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonarius) is a widespread species found in southern Central America and right through the northern half of South America. They are also present on several Caribbean islands, although it is widely suggested that these animals were introduced by humans. Whilst their populations are patchy across this enormous range and they require very specific microhabitats to thrive, they can be found in dense

rainforests, tropical forests and sparser, savannah habitats. Because of this, the red-footed tortoise is a surprisingly hardy species with some specimens living in locations with consistently hot and wet conditions and other specimens seeing cooler and drier months.

Researchers have managed to split the species into five clades, each with slightly different genotypes (but still

46 MAY 2024

Are You Tortoise Red-y?

Are You Tortoise Red-y?