www.exoticskeeper.com • april 2024 • £3.99 NEWS • DEATH ADDER • KEEPER BASICS • SOLOMON ISLAND LEAF FROG • LEAF-TAILED GECKOS A NATURAL HISSSTORY Francis Cosquieri discusses his extensive research into the husbandry of the hissing sand snake (Psammophis sibilans). RECREATING THE DESERT From soil functionality to lights and plants, Benjamin Dragantha-Fabian explores enclosures and enviromental research for horned lizards. IN THE VIVARIUM Manchester Museum is one of the largest university museums in the UK. We go behind the scenes in their herpetology facility. TER-MITE BE MORE TO THIS… The questions surrounding lace monitor breeding behaviours.

CONTACT US

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS thomas@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING advertising@exoticskeeper.com

About us

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY

Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4712

Digital ISSN: 2634-4689

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather Subscriptions

Spring is well and truly upon us. It is now that weather should start warming up and our native reptile and amphibian species are most active. One thing I cannot stress enough to keepers of reptiles is the importance of learning how wild reptiles live. Although Britain may be limited in herpetofauna diversity, our national conservation charities and developed infrastructure mean most people can access prime habitat and be in with a chance of seeing a native species. If you do anything this year, arrange a visit to your nearest heathland and observe the complex behaviours of snakes and lizards. It may inspire you to make subtle changes to your keeping practices. All the biggest leaps in husbandry practices start with an idea!

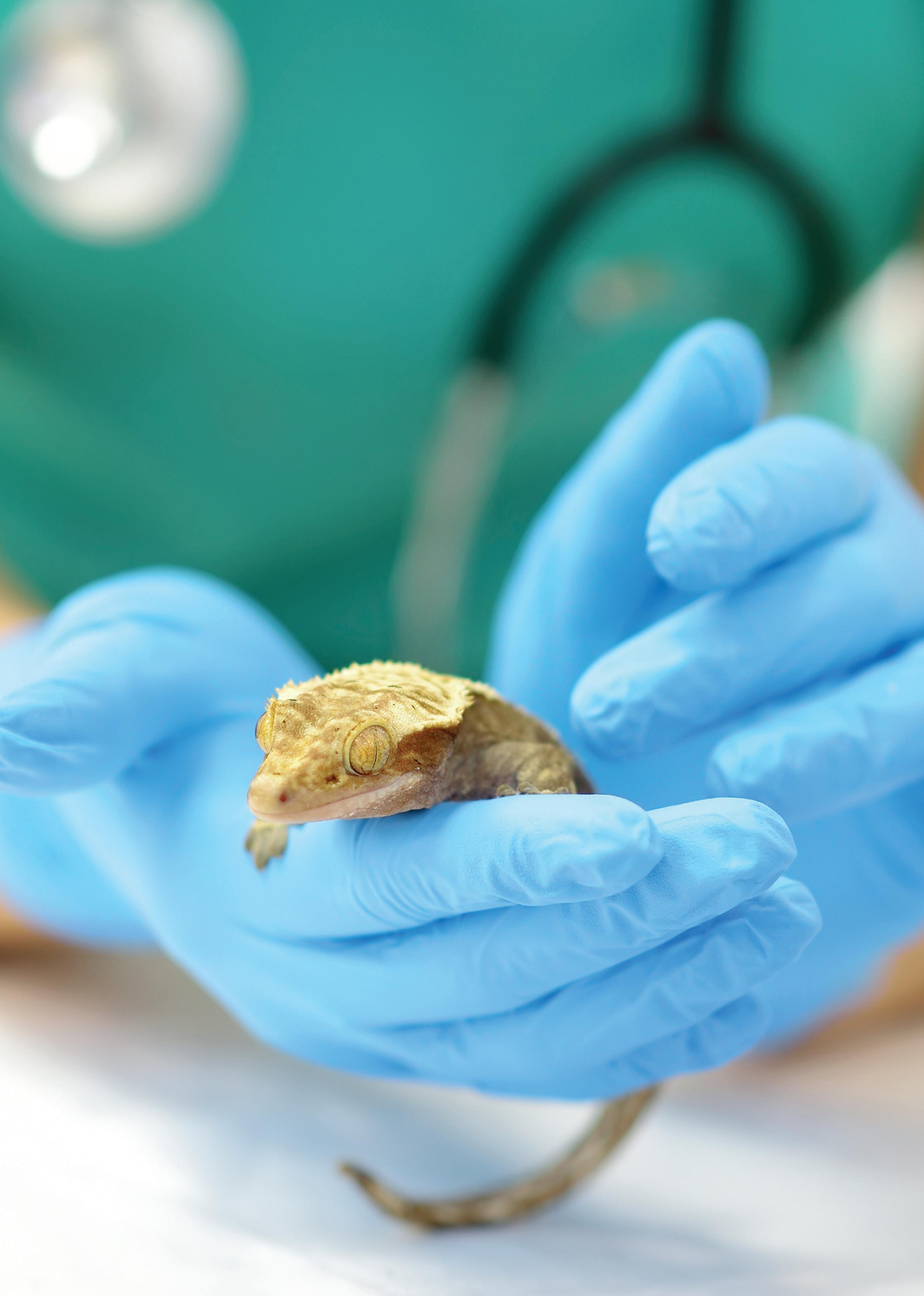

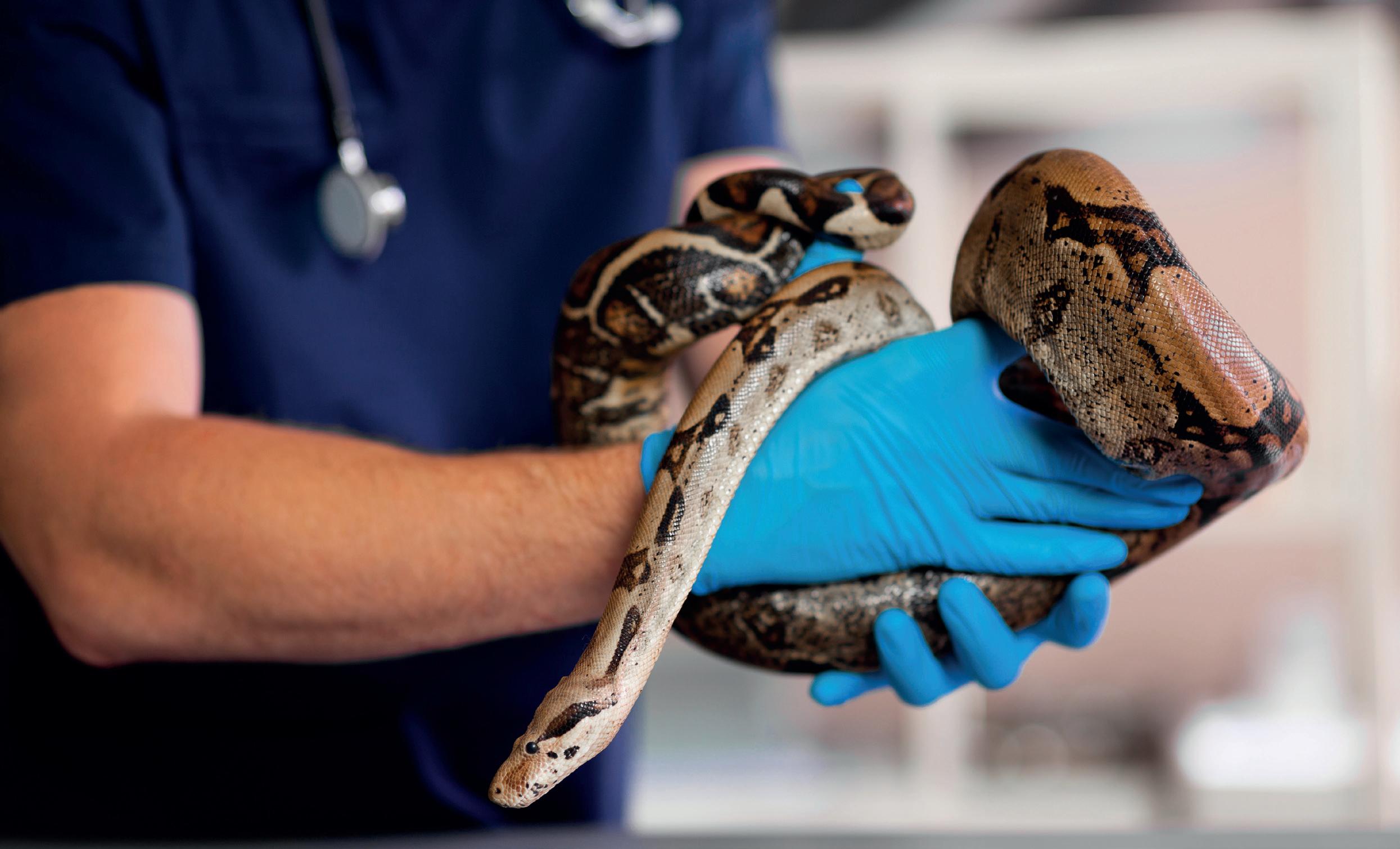

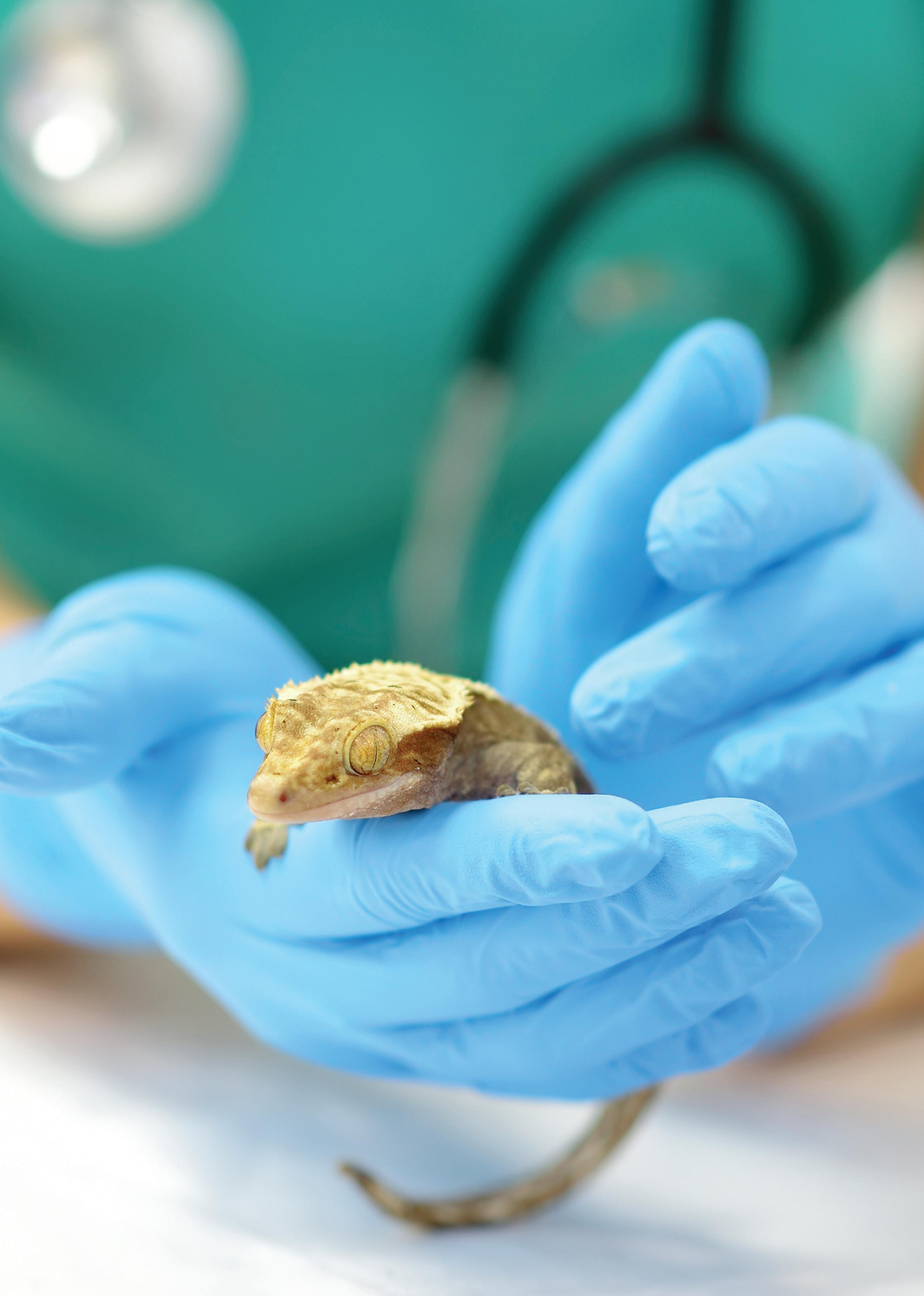

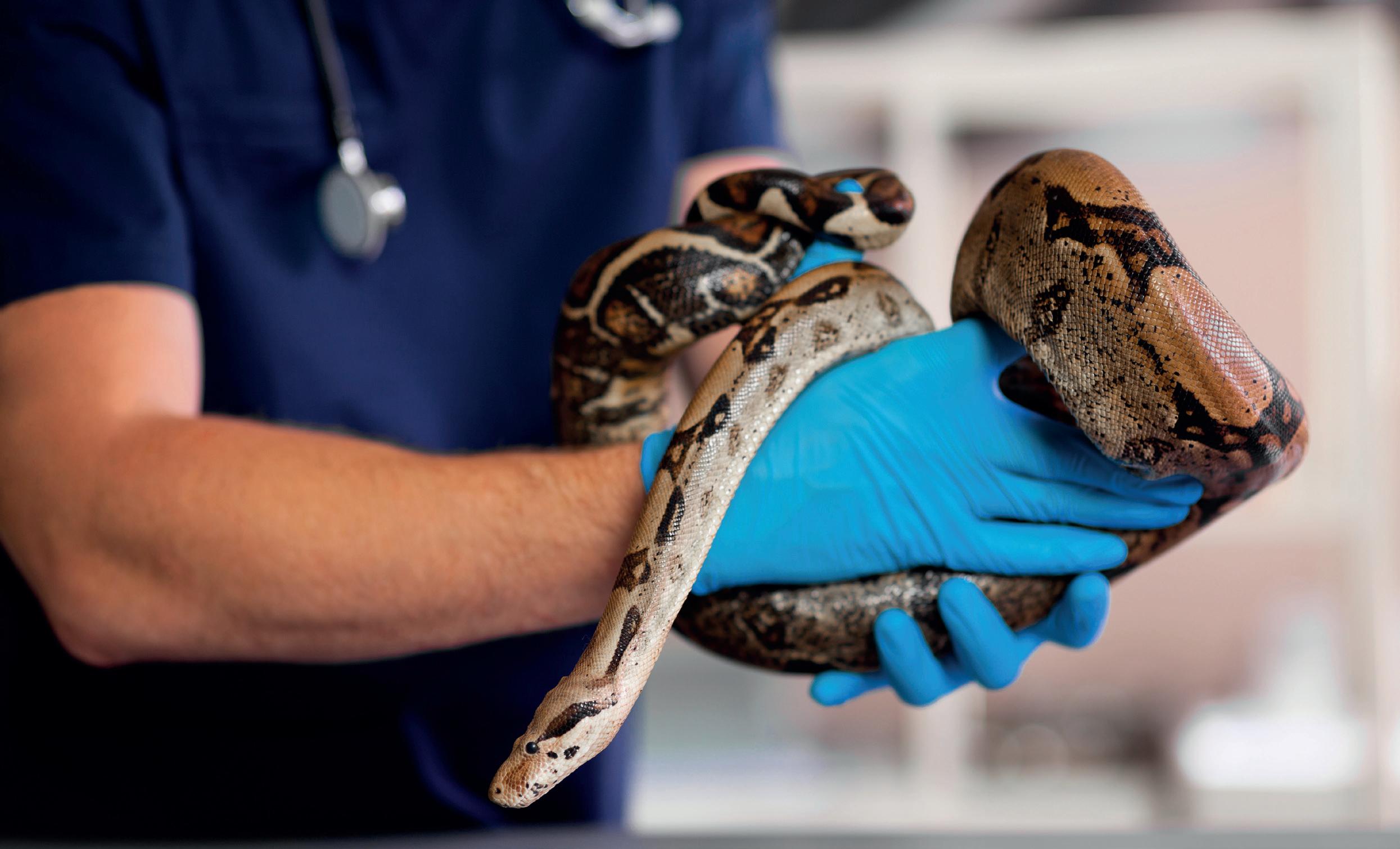

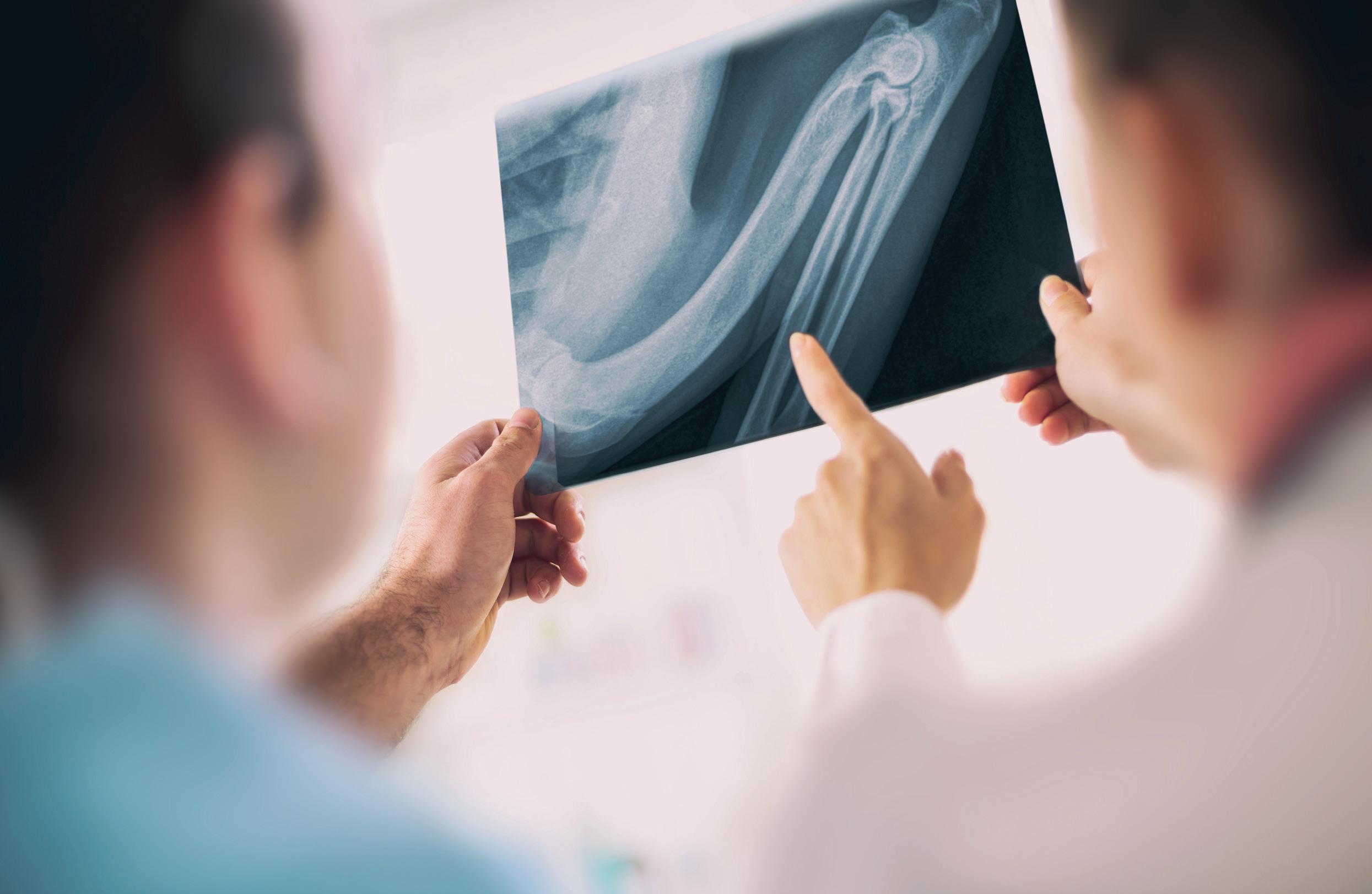

In this issue, I am delighted to present the incredible work of Dr Michaela Betts on a “Keeper Basics: Reptile First Aid” feature. It is always

a challenge to boil an entire topic down to 3,000 words, but hopefully, Michaela’s contribution this month will act as a very important tool for keepers during their most challenging times.

Our throwback feature also focuses on the work of BION Terrarium Centre, our friends in Ukraine. Their contributions to Herpetoculture are mind-blowing and you can support their cause and global herpetocultural conservation initiatives by joining The Responsible Herpetoculture Foundation.

Thank you,

Thomas Marriott Editor

Front cover: Lace monitor (Varanus varius) reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

Right: Short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos) IrinaK/Shutterstock.com

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Follow us Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

02

02

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

06

TER-MITE BE MORE TO THIS…

The questions surrounding lace monitor breeding behaviours.

12 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s the Solomon Island leaf frog (Cornufer guentheri).

53

14

FLASHBACK FEATURE: THE DEVIL IN DISGUISE Breeding satanic leaf-tailed geckos in captivity.

22 IN THE VIVARIUM

Behind the scenes at Manchester Museum’s herpetology facility.

30

RECREATING THE DESERT

A guide to enclosure design and environmental research for horned lizards.

42SAND SNAKES: A NATURAL HISSSTORY Research into the husbandry of the hissing sand snake (Psammophis sibilans).

53 KEEPER BASICS: Reptile First Aid.

58

FASCINATING FACT

Did you know...?

06 22

30 42

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic animals

Elusive worm lizard seen for first time in 90 years

A rare worm lizard has been rediscovered in Somalia by a landmine clearance team, in the first official sighting of the subspecies since 1931.

The elusive reptile, the Somali sharpsnouted worm lizard (Ancylocranium somalicum parkeri), hadn’t been seen by scientists for over 90 years and was found on the border between the self-proclaimed state of Somaliland and Ethiopia while the area was being cleared of mines.

Mark Spicer photographed the reptile after being alerted to its whereabouts by his colleague, Hassan Duali. Spicer, a member of the HALO Trust nonprofit which helps countries to clear landmines and recover after conflicts, told New Scientist magazine how he and his colleague, wearing protective equipment, dug into the ground to uncover the lizard.

It was confirmed to be a Somali sharpsnouted worm lizard by Tomas Mazuch at Mendel University in the Czech Republic. The species reaches around 20cm in length and is a distinctive fleshpink colour. So far only found in Somalia and Ethiopia, the species is fossorial, with pointed snouts to help them

burrow through soil. The lack of sight allowed by their small eyes is countered by its heightened sense of hearing.

Their underground habitat makes them difficult to spot, hence the 90 year interlude in sightings, leaving many questions unanswered about worm lizards and this species in particular.

Scientists close to antivenom breakthrough

Scientists at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California believe they have found an antibody that counteracts the venom of some of the world’s deadliest snakes.

So far, tests carried out on mice have found that the antibody has prevented the test subjects from being affected in the typical way by venom from snake species found throughout Australia, Asia and Africa.

In Science Translational Medicine, the research team described their use of laboratory-made toxins to “screen billions of human antibodies and identify one that can block the toxins’ activity.” Identifying the existing antibodies will enable the development of an antivenom that ranges across many species from the Elapidae family, including the king

cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) and the black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis).

The researchers identified a toxin produced by every venomous Elapid snake that causes whole body paralysis and, after screening the antibodies, found one that was capable of blocking the toxin.

Mice were exposed to the venoms of species such as the black mamba, king cobra, Indian spitting cobra (Naja kaouthia) and the many banded krait (Bungarus multicinctus), and then injected with the antibody. Not only did the mice not experience paralysis, they also survived the toxins.

The methodology of causing an antibody to act like a human protein is also used in existing HIV treatment, giving the research team a blueprint to work from in the development of the new antivenom.

While the current antivenom is not effective against the venom of the Viperidae family, researchers are working to find an antibody that is. Once it has been discovered, it is hoped that it can be combined with the existing antibody to create a ‘universal’ antivenom with the potential to save countless lives around the world.

2 APRIL 2024 Exotics News

was the tortoise

on the motorway?

What

doing

©Mark Spicer

Sibons

King cobra (Ophiophagus hannah

)

photography/Shutterstock.com

New kangaroo lizard species found

A new species of kangaroo lizard has been described after being found in the Western Ghats of India.

The lizard has been named Agasthyagama edge, in honour of the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence Program, a global conservation initiative that focuses on threatened species that represent a unique portion of the world’s natural heritage.

The small lizard reaches lengths of only around 29-44cm and inhabits semi-evergreen tropical forests, particularly favouring undisturbed vegetation. Its location has caused some confusion as to why it has taken so long for it to be described. The Western Ghats region of India was heavily explored during colonial occupation by the British, making its years of remaining undiscovered to science a mystery.

The reptile is the second addition to the Agasthyagama genus, joining beddomii, currently known as the Indian kangaroo lizard. The new find is slightly less common than its sister species and they inhabit territories 50 miles apart.

Protecting turtles’ nests may have negative impact on predators

Researchers from the University of Taipei, National Chung Hsing University, San Diego State University and National Taiwan University have found that measures taken to protect turtle nests from predators is having a negative impact on reptiles who rely on turtle eggs as a key part of their diet.

The team studied two species of snake, the kukri snake (Oligodon formosanus carinata), both of which feed on turtle eggs, for a 23 year

period on Orchid Island. The ecosystem of the Taiwanese island allowed researchers to observe the welfare of the snakes before and after access to turtle eggs was removed.

Beach erosion on Orchid Island caused many sites to become unsuitable for turtles to nest on, worsened by severe storms in the area in 2001, causing authorities to install fencing to keep predators away from the eggs in 1997.

Over two decades of the measures has had a notably detrimental effect on various reptiles that inhabited the island’s ecosystem, according to the researchers. The snakes are now predating more heavily on the eggs of lizard species to compensate for the loss of turtle eggs in their diet, causing numbers of certain lizards to decrease.

The research paper states: “sea turtle eggs provided a critical subsidy to the terrestrial ecosystem of Orchid Island, supporting large populations of kukri snakes and stink rat snakes, and when this subsidy was removed, these snakes shifted into other habitats for alternative prey, perhaps driving the widespread decline of those lizard species vulnerable to egg predation.”

The findings have raised questions around the potential knock-on effects of protecting one species at the expense of others.

3 APRIL 2024 Exotics News

Prefer to get a quote than a joke? Visit exoticdirect.co.uk About 100 millimeters per hour!

©Sandeep Das

Kukri snake (Oligodon formosanus)

New species of green anaconda

A second species of green anaconda, one of the largest snakes in the world, has been described, distinguishing between two species previously thought to be the same.

Anacondas are non-venomous constrictors that can reach over 17 feet in length and are the heaviest snake in the world. Adult anacondas are semi-aquatic, spending much of their time in water.

The northern green anaconda (Eunectes akayima sp. Nov) is now classed as a separate species to the southern green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), following research by the University of Queensland.

Analysis of genetic data from both snakes has allowed

scientists to determine that the northern anaconda is distributed across much of South America, including Suriname, Venezuela, French Guiana, Ecuador and Colombia, as well as in Trinidad. The southern species’ wider range stretches from the Brazilian Amazon River delta to French Guiana.

The research to distinguish the species has been ongoing for two decades, culminating in a successful trip to the Ecuadorian Amazon in 2022, where the researchers collected tissue and blood samples, as well as data on habitats and locations. Analysis proved that the snakes were different species and showed a 5.5% divergence in their genetics, despite their remarkably similar appearances.

Written by Isabelle Thom

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

THIS MONTH IT’S: FROGLIFE

Froglife is a national wildlife charity committed to the conservation of amphibians and reptiles – frogs, toads, newts, snakes and lizards – and saving the habitats they depend on.

www.froglife.org

4 APRIL 2024

THE

Websites | Social media | Published

Exotics News

ON

WEB

research

Green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) Patrick K. Campbell/Shutterstock.com

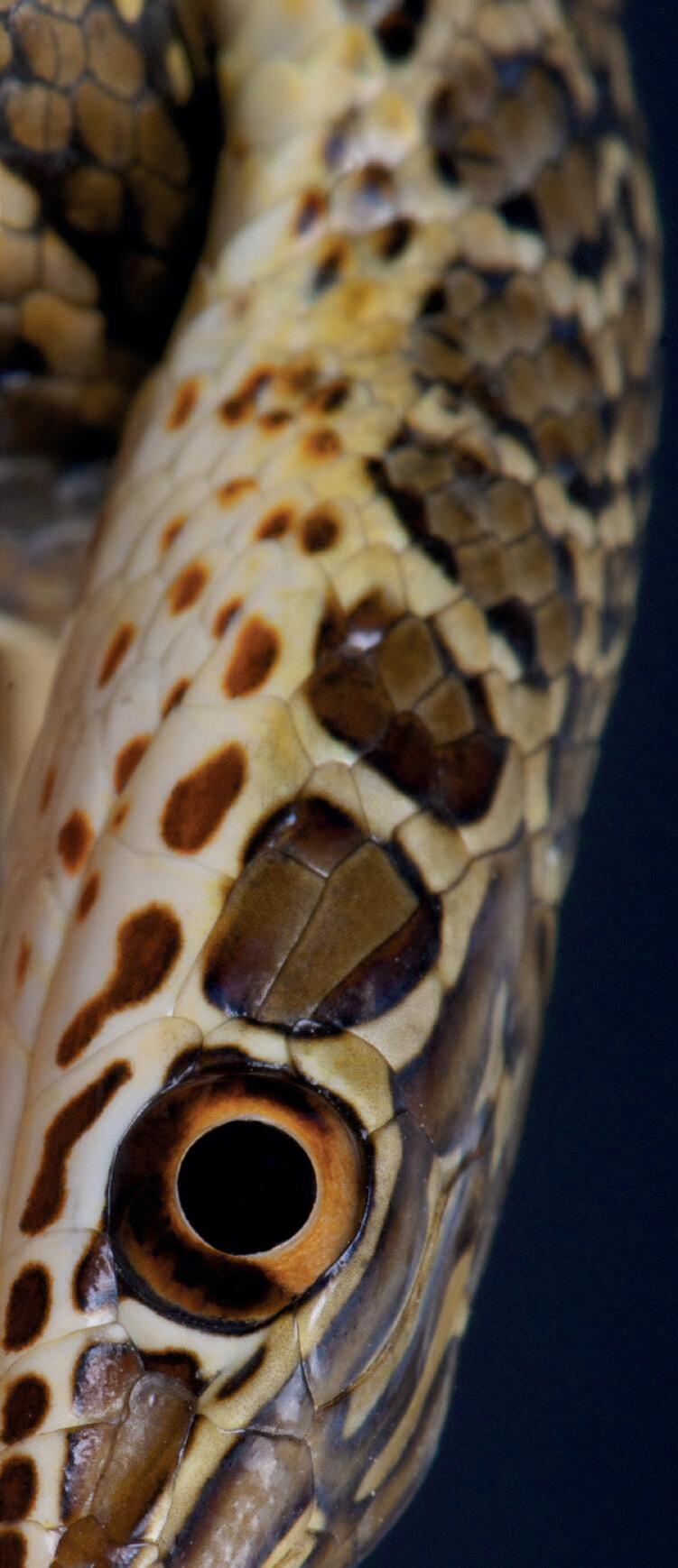

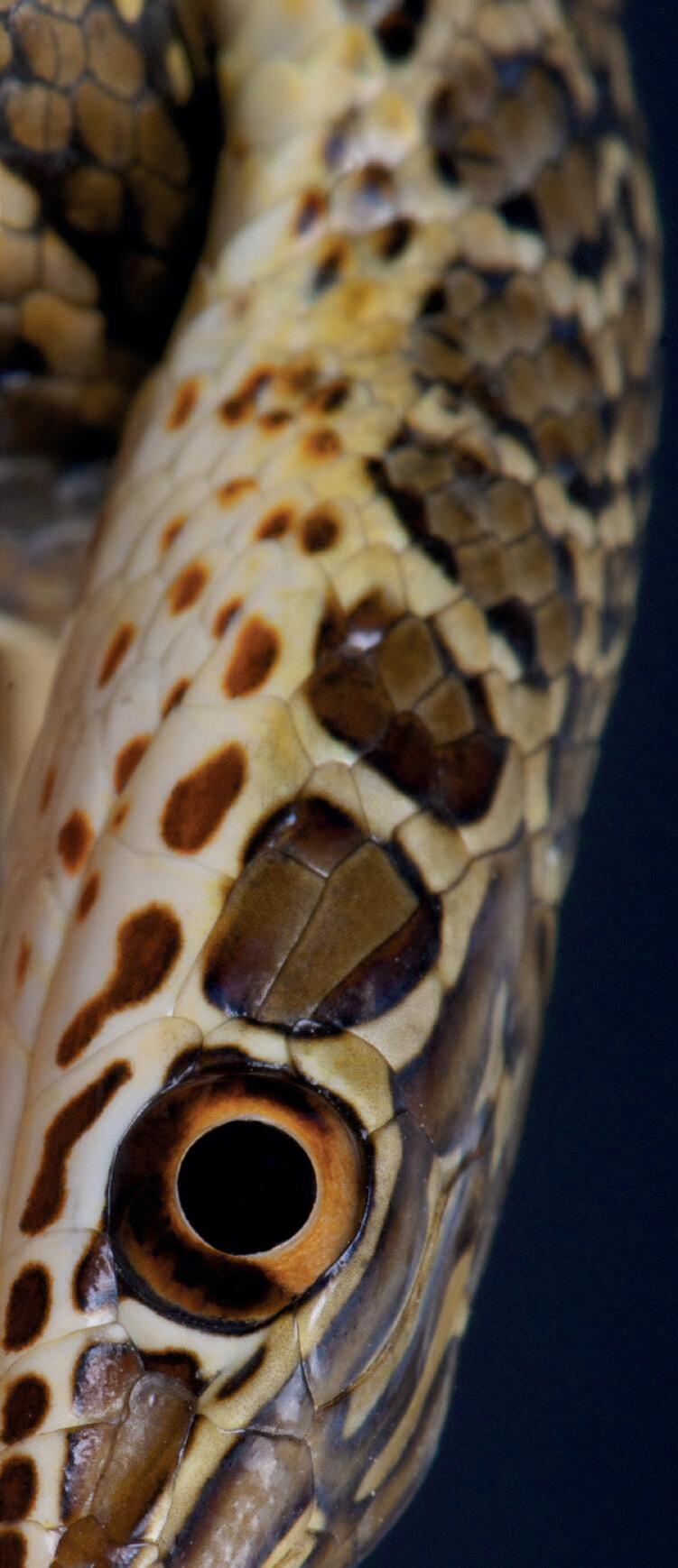

TER-MITE BE MORE TO THIS…

The questions surrounding lace monitor breeding behaviours.

6

reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

The lace monitor (Varanus varius) is the third largest lizard in Australia and occupies an enormous range encompassing most of the country’s eastern half. Despite this, researchers are still uncovering some startling discoveries about the ecology and breeding behaviours of these iconic lizards. Exotics Keeper Magazine caught up with Jules Farquhar, Research Assistant at Monash University to learn more about the species.

An introduction to lace monitors

Lace monitors are large, robust members of the Varanid family. Reaching up to two meters in length, they are the closest living relative to the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) and a 2005 study revealed that these lizards possess venom that showed potent effects on the bioactivity of prey.

Lace monitors are also sometimes called “tree goannas” due to their semi-arboreal lifestyle. They can be found basking high in trees and can quickly scale even the smoothest Eucalypt trees due to their large claws. Like other large Varanids, juvenile “lacies” tend to exhibit more

arboreality in their behaviours, however, adults do spend much of the cooler months in tree hollows and will even nest in arboreal termite mounds.

Lace monitors will feed on a wide variety of prey. They can cover many miles in search of food and will scavenge on just about anything from human food waste to roadkill kangaroos and insects to bird eggs. Lace monitors are well-suited to living alongside humans and will opportunistically raid chicken coops and park bins. This adaptability, combined with an enormous distribution range marks lace monitors as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

8 APRIL 2024 Ter-mite Be More To This…

Varanus varius was first described as Lacerta varia by John White in 1790 and was reclassified multiple times until the Varanus genus was established in 1820. The name varius is a derivative of "variegated" meaning diverse in colour or pattern. Currently, there are no subspecies within the Varanus varius species. However, there is a very striking “Bell’s Phase” colour form that is sympatric to the more commonly seen “Laced” form, making Varanus varius a polymorphic species.

The Bell’s phase

The bell’s phase of the lace monitor is a beautiful colour morph that has distinct light and dark bands running down its entire body. In some individuals, these can be a bright beige or yellow, contrasted with dark grey patterns.

Once described as a unique species named Varanus belli in 1836, herpetologists soon identified it as an unusual variation of Varanus varius. Whilst morphological differences occur in many species, the ‘bells phase’ is an interesting case of polymorphism and whilst the speculation persists that only “bells phase” animals occur West of the Great Dividing Range, this is not strictly true as Jules explains:

“We analysed if there’s bias in where the morphs occur. We found that on the East Coast, southeast and the Gippsland area, it’s almost exclusively the ‘lace’ morph. Whereas further inland the ratio of the morphs becomes more biased towards Bells. There’s not to see there’s this clean exclusion that divides them, rather a gradual transition between East and West or coastal to inland.”

9 APRIL 2024 Ter-mite Be More To This…

Wright Out There/Shutterstock.com

Jules managed to conduct research using iNaturalist, a citizen conservation initiative that encourages the general public to report their sightings. The lace monitor is the second most reported species of reptile in Australia, with over 6,500 records of animals across their range. However, understanding the climactic variables that underpin the morphological bias is a far more complex question.

“The occurrence of the Bell's Morph correlates with aridity” Jules confirms. “They also occur in areas that have higher solar radiation. On the opposite side, the ‘lace’ morph occurs in more cloudy regions. This could explain why the lighter animals are found more inland and the darker animals in cooler, coastal regions. Although, that’s not to say that they have evolved like that. In fact, it’s almost certain that the Bells mutation just randomly appeared in the outback and it did well out there. Whereas, on the coast, it was probably too conspicuous to achieve the same success.”

“What is interesting is that the ‘Bells’ gene is dominant, meaning there are more ways to make a ‘Bells Phase’ monitor than a ‘Lace’ one. Yet, the lace morph is the more prominent and common one. You need a double dose of lace genes to create a lace morph. This could mean that the bells morph is a relatively newly emerged gene and eventually, it will spread further East. We’ll never know!”

Of course, it could be a combination of a few things. Perhaps over time, the bell's morph will spread further East up until a point when the climate weeds out the conspicuous Bell's individuals and creates a divide. But then again, that’s ecology – nothing usually falls into these categories very easily!

Breeding season

One of the most interesting aspects of lace monitor ecology is their breeding behaviours. Lace monitors are thought to nest exclusively in termite mounds. Whilst there are numerous records of reptiles utilising the stable climate and physical protection of termite mounds to lay their eggs, lace monitors may be the only species that use them exclusively.

“To my knowledge, no one has evidence of them nesting in anything other than mounds of Mastotermes termites,” said Jules. “Lace monitors have an unusually long incubation period of up to 300 days. You need a long period to create a large lizard, but of course, this species occurs in unpredictable climates of southeast Australia. You could argue that the reason lace monitors can grow so big is because of termite mounds. This is true for Rosenberg’s monitors too.”

Lace monitor females begin testing nest sites in spring by digging up termite mounds. Eventually, when an appropriate site has been found, they will excavate a hole and lay the eggs. The termites will patch up the hole within a few hours or days and seal the eggs inside the mound. The eggs then require consistently high temperatures of +29°C for up to nine months, before they are excavated the following spring.

“There’s a few questions about the process” added Jules. “Firstly, does the mother come back and break the young out of the nest? We know that lace monitors are breaking into the nests when the eggs are hatching. What we don’t know is whether this is instinctual or whether termite mounds are just a scarce resource. So, by laying

10 APRIL 2024

Ingvars Birznieks/Shutterstock.com

your eggs in one you can bet your bottom dollar, so to speak, that another female will come along and break them out. However, I don’t think that’s an elegant enough explanation. I think evolution has done something a little more special than that.”

Some larger lizards go through an embryonic diapause, which is the temporary suspension of the development of the embryo. There are recorded cases in other species of Varanus Jules believes this may be the case for lace monitors.

Jules continued: “Varanus indicus develop up until a certain point, until they are just about ready to go, then just sort of stop until they are ready to hatch. I’ve heard anecdotes from lace monitor keepers that have walked past their enclosure and disturbed the nest and that’s triggered the hatchlings to emerge early. I suspect that it’s at least possible that it’s at least possible that the young are developed by winter, but wait in suspended animation to coincide with when lace monitors start doing test digs in termite mounds in early spring to hatch.”

“Rosenberg’s monitors will frequently lay their eggs in termite mounds. However, they will also create nests in the ground. Rosenberg’s monitors also tend to nest every other year, whereas lace monitors seem to nest every year.

“I find this quite telling” added Jules. “If you’re an adult lace monitor and your young are relying on adult lace monitors to break them free, you have to nest every year whereas Rosenberg’s can probably get away

without nesting every year. Even more interestingly, know that Rosenberg’s monitors are capable of busting themselves out of termite nests, because we can see baby monitor-sized holes in the mounds. Yet, we don’t have any evidence to prove that lace monitors are digging themselves out of the hole. All 40+ photos of lace monitor emergences are coming out of big bore holes made by adult lace monitors.”

Lace monitors in captivity

Being a protected species in Australia, lace monitors are not frequently found in captivity outside of their home range. Their size also restricts their keeping to only the most specialist collections as 99% of keepers will not have the room to accommodate such a large animal. In Australia and the US, keepers can build outdoor enclosures and runs, which allows some enrichment for captive individuals.

In the UK, an adult lace monitor would require a room-sized enclosure with extremely high UV radiation and warm ambient temperatures for at least 8 months of the year. Their hardy nature means these animals are tolerant of enormous temperature dips, even going almost dormant in winter, but being a large-bodied reptile they will require powerful penetrative IR-A heat through most of the year. Some keepers can provide all these husbandry requirements and keep the species successfully. However, as the second most sighted reptile in Australia (according to iNaturalist), it is much easier and cheaper to observe wild lace monitors than fulfil their very specific needs in a captive environment.

11 APRIL 2024

Danny Ye/Shutterstock.com

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

The wonderful world of exotic animals

Solomon Island leaf frog (Cornufer guentheri)

The Solomon Island leaf frog, or “SILF” as it is sometimes referred to, is an extremely unique amphibian that is poorly established in the hobby. This is more likely due to the limitations of exporting animals from their home range in Papua New Guinea than because of their particularly complex captive requirements.

Soloman Island leaf frogs are extremely variable in colouration. Even amongst siblings, colours can vary from shades of bright green to dark browns and yellows. Unlike other “leaf” and “horned” frogs, colour is typically uniform with no patterns.

These frogs can be housed comfortably in small groups from young. However, group dynamics may change as they age, so housing proven pairs together is a more suitable option. “SILF’s” mature quickly, and young males will begin calling (very loudly) as young as 4 months of age. Until this point, sexing the frogs is difficult at best.

Solomon Island leaf frogs inhabit lowland rainforests and secondary habitats on the Solomon Islands and Bougainville and Buka Island, off the coast of Papua New Guinea. Therefore, careful consideration and research should be put into sourcing captive-bred frogs. It is thought the initial Ceratobatrachus guentheri bred by private keepers came from zoo stock. However, supplementary imports may have occurred over the years. Luckily, there are numerous breeders across Europe and the US who are producing good numbers of captive-bred animals for the trade.

These frogs prefer warm temperatures (23 - 25℃) but will tolerate a slightly broader range, especially if they are given access to cooler areas. Unsurprisingly, these animals feel most comfortable amongst dense leaf litter. This should be sprayed frequently to maintain a consistent humidity of over 65%. Low-level UVB (Ferguson Zone 1) should also be provided to create a day/night cycle. Although these frogs are nocturnal, they will bury into leaf litter and expose their fleshy horns during the day, so appropriate UV fluctuations are necessary for their ecological and physiological cues.

Some “lines” are reported to have particular sensitivity to high bacterial loads, so a well-established bioactive setup may help ease the burden of excessive cleaning. Otherwise, a well-maintained glass terrarium (60x45x30 for a pair) with plenty of substrate that is changed every other week, will create an ideal environment. Logs, hides and a shallow water bowl are all welcomed additions.

Species Spotlight reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

NutriRep™ is a complete calcium, vitamin & mineral balancing supplement with D3.

It can be dusted onto all food sources including insects, meats & vegetables. No other supplement is required.

THE DEVIL IN DISGUISE

Breeding satanic leaf-tailed geckos in captivity.

Satanic leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus phantasticus)

Satanic leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus phantasticus)

FLASHBACK FEATURE

The

Devil in

The leaf-tailed geckos of Madagascar are amongst the most cryptic of all animals on earth. Each species of the Uroplatus genus has developed unique adaptations to blend almost seamlessly with their environment. Some resemble moss (U. sikorae & U. semieti) and some resemble bark (U. pietschmanni & U. lineata), some are huge (U. giganteus & U. fimbiratus) while others are tiny (U. ebenaui & U. fiera). However, there is one species that has gained a demonic title for its other-worldly appearance: the satanic leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus phantasticus).

Forged in fantasy

The satanic leaf-tailed gecko is a tiny species of arboreal lizard belonging to the ebenaui complex (U. ebenaui, U. phantasticus, U. malama, U. fiera). Sometimes referred to as the eyelash leaf-tailed gecko because of its unique head shape or the phantastic leaf-tailed gecko from the Greek ‘phantasticus’ meaning ‘imaginary’. These obscure-looking lizards have evolved to mimic dead leaves. They are currently considered ‘least concern’ by the IUCN (though other members of the complex are at greater risk) and inhabit humid rainforests throughout Northeast and East Madagascar. In the wild, these geckos can be observed nesting in bundles of dead leaves that have gathered within spider webs throughout the day before venturing out at night to hunt small insects and molluscs.

Satanic leaf-tailed geckos are sexually dimorphic and behavioural observations can be used to distinguish the sexes. Firstly, males often (but not always) possess indentations on their tail to mimic a decaying leaf. They are also far more patterned and easily blend into mossy forks on tree trunks and branches. Females are more defined, with a uniform colour (usually a light shade of brown) and will adopt a resting position hanging stationary from a branch to replicate a falling leaf. Females are also more likely to possess a vertebral stripe that looks like the central vessels within a leaf.

16 APRIL 2024

Of all the leaf-tailed geckos, the satanic leaf-tailed gecko is perhaps the most well-established in herpetoculture. As there have been numerous quotas exporting these Disguise

animals from Madagascar, there are now many breeders as well as several zoological institutions working with the species in a captive environment. This has developed our knowledge of the entire genus and helped herpetologists describe new species that share similar traits with Uroplatus phantasticus. Perhaps the largest breeding facility for these obscure lizards is BION Terrarium Center in Ukraine.

BION Terrarium Center

BION Terrarium Center was established in 1993 as a reptile import and export facility. It was restructured in 2010 to focus entirely on the captive breeding of reptiles and amphibians. The facility breeds a total of 50 species, many of which are threatened in the wild or are sought after by smugglers. BION works with several species of Madagascan reptiles and has bred nine species of Uroplatus over the last decade. Oleksii Marushchak, Head of Research and Development at BION Terrarium Center

told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “All our breeding stock was legally imported from Madagascar, except for a small quantity of captive bred specimens from Czech Republic. We are now on our fifth generation of captive bred Uroplatus phantasticus. Last year we produced around 140 phantasticus and the year before that we produced around 120. In previous, peaceful years with normal controlled conditions we generally produce 100+ and this year we were hoping to produce almost 300 animals but due to the war in Ukraine, we were unable to reach that goal. Despite everything, we have still had eggs and managed to breed the species once again this year.”

Although there are a lot of people who work with satanic leaf-tailed geckos, few people breed them in substantial quantities. Many hobbyists breed them annually, but there are not enough to produce large enough numbers for them to become established in the pet trade. This makes the work that BION is doing and its associated research extra valuable.

17 APRIL 2024

Newly hatched satanic leaf-tailed geckos

The Devil in Disguise

A dance with the devil

Satanic leaf-tailed geckos, despite their delicate appearance and fragile bodies are straightforward to keep. However, breeding them is a completely different story. Perfecting the formula can take many years and a lot of hours observing animals.

Oleksii explains: “They are very fragile and there are a lot of difficult moments when working with Uroplatus phantasticus. The first problem is that it is difficult to define the age of a wild-caught animal. Even a visually good-looking specimen can be incredibly old, so animals can die simply of old age. Therefore, it is always better to buy captive-bred individuals to at least get an estimate of their age.” Although Madagascar is now closed to exports, there will likely be many wild-caught leaf tailed geckos in circulation.

As well as problems in sourcing animals, hobbyists can quickly make assumptions about the species without truly looking at their needs. Even online data based on the regional temperature and climate of their distribution can be extremely misleading. “Even though many people think ‘okay they’re from Madagascar, that’s close to Africa, it must be +30C’ they don’t understand that these animals inhabit special microclimates” adds Oleksii. “They inhabit locations deep in the bush where the air temperature is no more than +25C and 27C could be dangerous to them. There is also the assumption that because they are nocturnal animals, they don’t require ultraviolet. This is absolutely not true. We use tubes where UV is about 5.0 or old tubes where UV was 10.0 but is now much less.”

Satanic leaf-tailed geckos are not difficult to keep because they thrive at a typical “room temperature.” If they are given the right diet, enough UVB and appropriate décor to allow them to choose their own elevation, they are simple to keep. The major problem is maintaining the conditions within the home. Unexpected temperature spikes can cause serious problems. For example, when the UK has sudden temperature spikes throughout summer, this can seriously tip the environmental conditions in the terrarium into potentially lethal territory. “The only thing that needs to be strictly controlled is the environment” adds Oleksii. “If someone is going out for the day for a BBQ or something, they really need to consider the climate control technology in their home or lab. If they can maintain steady temperatures, phantasticus is quite easy to keep.”

18 APRIL 2024

U. phantasticus pair in copulation

Female satanic leaf-tailed gecko laying eggs in substrate

Doing the devil’s tango

There are some husbandry practices that must also be applied to the general maintenance of satanic leaf-tailed geckos if the hobbyist wishes to breed them. Some of these are quite common and follow a similar pattern to other reptiles, while others are far more specialist.

“Many people also fail by not providing a winter dormancy period” adds Oleksii. “Almost all reptiles need a period of winter dormancy, torpor, or winter rest. It is needed for proper development of spermatozoids and oesticides. If one does not provide the correct winter dormancy the breeding will fail. We drop temperatures to around 20-21°C in the day and 16-18°C at night. It is important to track the state of the animals to ensure the winter dormancy is not too long or too short.”

“For us, the hardest thing to understand was the interaction between males and females during breeding. We would add a male to a group of females and expect them to breed. We see a male copulate with one female, then the next female, then they lay eggs, the male copulates again and eventually the male would die without any reason. We developed our understanding only when COVID-19 made us quarantine in the BION facility. I and several other members of staff had to live on site, so we had a chance to track what the animals were doing when the lighting was off. We discovered that, when placed with other females, the male always wants to breed. When he is ready to copulate, he completely forgets about food and water and only has one thing on his mind – breeding. Because we keep our

animals in laboratory conditions, the males always had a female in their vision. So, we made corrections to our methodology, and we no longer keep our males with our females more than three days after the female has laid the clutch, no matter whether the clutch is fertile or not.”

Finally, and perhaps the most specialist trick to ensure success when breeding Uroplatus, but especially phantasticus is to feed them lots of snails. Oleksii explains: “There are a lot of sources of calcium that can be added to a terrarium. We use supplements, powders, some with D3, some without D3, some with added nutritional elements and even cuttlefish bones. They work well but not perfectly. Whereas, if we add snails to a female’s diet, they are far more successful at breeding. We add these as soon as they awaken from winter dormancy. Here, their diet is made up of 60-80% small, soft-shelled snails. All their eggs are calcified, healthy, incubate well and hatch successfully. Plus, the babies are far healthier.”

A female can make two to five clutches per season. Some can make up to seven clutches per season. A typical clutch is made up of two eggs. BION’s hatch rate is also exceptionally good, with about 90% of eggs hatching and about 90% of these are healthy babies. “There are a lot of different incubation methods” Oleksii added. “We use “Seramis” medium as an incubation substrate. This is finely chopped egg stones that are usually used in plants. We provide them with +70% humidity. They also have a slight temperature drop. So, +24-25°C in the day and +20-21°C at night.”

19 APRIL 2024

Young male satanic leaf-tailed gecko

Angels and demons

The expertise of Oleksii and the rest of the team at BION is pivotal in helping herpetoculturists understand how to breed other leaf-tailed geckos. As a genus that is constantly growing, with many more species being described each year, it is important that herpetoculturists stay ahead of the curve and document their methods.

“The problems I have mentioned are more-or-less common for most Uroplatus. I would not say phantasticus are the most-difficult species to breed. In fact, for me and my research, I would say Uroplatus pietschmanni are most difficult. We understand that different species occupy different ecological niches. Some species occupy bushes, some occupy tree trunks, others occupy tree canopies. Pietschamnni are one of these species. They have better airflow so they need more air change, they are exposed to more UV, the air pressure might also be a key factor. We did breed pietschmanni but not in such large quantities. The most difficult are the newly described species because we have absolutely no resources to know how to do it.”

There is a lot of controversy around the introduction of the newly described leaf-tailed geckos in herpetoculture. This is partly because they do not have a scientifically backed conservation status and therefore cannot be accurately added to CITES. This means there are no export quotas for the species. Many of the new species also look very similar to other species. For example, Uroplatus fiera looks like a large Uroplatus ebenaui. There may be cases of hobbyists believing they have a large ebenaui but in fact, are keeping fiera. That lack of information can create complicated mistranslations of existing information. Uroplatus kelirambo also looks similar to phantasticus and therefore, distinguishing between a previously “widespread” species may be difficult.

“I have heard that there is an idea that the red-eyed

animals are another form or colour variant. I think this is just a feature of their eye. We have many individuals of phantasticus and all of them, under certain light, turn red. When we switch off the light, the next day they return to a light brown or yellow iris. I don’t think the red-eyed animals are a particular morph, I think it is just a peculiarity of their eye structure. I have never seen an individual that has red eyes all the time.”

Hell on earth

Slash-and-burn-farming is a major threat to all Madagascan animals that occupy rainforests and leaf-tailed geckos are no exception. The forest is burned to produce tree coal and later to be adapted into rice fields and vanilla, ginger, or tea farms. This indiscriminate disaster is happening across the island and unfortunately affecting a wide range of species. Of the entire Uroplatus genus, over 30% have only been described in the last decade including one in 2020 and two in 2019. Sadly, entire species could be lost to slash-and-burn farming before they are even described to science.

Global warming is also extremely dangerous for satanic leaf-tailed geckos. They are a fragile species and if the temperature increases by just a few degrees, it will spoil their winter dormancy period, their incubation period and limits their options when finding cooler microclimates within the forest. This may leave them exposed to introduced predators such as domesticated cats, dogs or rats. “Uncontrolled harvesting and smuggling can also have an impact on their populations in the wild” adds Oleksii. “This is why herpetoculture matters. It means we can produce animals from legally obtained breeding stock. We make them affordable and offer them in large quantities within the market and therefore, we are happy, the people are happy, and the smugglers don’t receive their money.”

20 APRIL 2024

Portrait of satanic leaf-tailed gecko`

THE RESPONSIBLE HERPETOCULTURE FOUNDATION (RHF)

As well as breeding thousands of animals each year in a bid to protect wild populations from illegal harvesting, BION Terrarium Center together with Philippe de Vosjoli and a team of international Editors, has also established the Responsible Herpetoculture Journal. “I probably uncovered all the secrets for breeding phantasticus there! We might have to stop the programme now!” joked Oleksii. “But seriously, all the information we give is our contribution to herpetoculture. If we die one day, it will be a big loss of experience if nobody has access to it. That is why we publish methodology, write articles, and do interviews.”

As well as sharing their own information, the team at BION have also produced the Responsible Herpetoculture Journal as part of the RHF. Subscribers and supporters of the RHF are given access to this monthly journal that centralises information and publishes the articles of herpetoculturists in a way that is easy to both produce and consume. “Many hobbyists have more valuable information than scientists have” Oleksii added. “I am a scientist myself and I know that not all scientists can afford to keep lots of valuable and expensive animals in their labs. The main goal of RHF is to share this information amongst as big audience as possible.”

Dmitri Tkachev, Director of BION Terrarium Center and Founder of the RHF added: “The main role of RHF is to become a public relations and educational platform that will protect the interests of herpetoculture both as a hobby and industry. For example, USARK does it in terms of legislation, while RHF would do through ideology, methodology and education. At the same time, RHF policy is to promote active cooperation with and mutual assistance to all partner organizations

(USARK, DGHT, TTCG, Citizen Conservation, etc.) We are not going to be the ultimate truth; we appreciate the role and importance of all of these and other stakeholders.”

The Responsible Herpetoculture Foundation encourages and supports all private breeders who contribute to forming, maintaining and increasing ex-situ populations using only responsible and legal approaches to obtaining, moving and keeping animals as well as supporting the unconditional right of responsible breeders to sell captive-bred species. RHF’s goal is to raise the authority and status of herpetoculture in global conservation community and to become an informative, educational and public platform for all involved and interested parties. “The ethics of selling captivebred animals to reduce over-harvesting worldwide seems to be clear and logical” adds Dmitri.

conservation in a way that conventional pet keeping never will be. Not only is herpetoculture a discipline in and of itself, but the breeding of unique and cryptic species is also a vessel for education and a tool to improve scientific understanding.

Philippe de Vosjoli adds: “We feel the relevance of this foundation and the opportunity to bring it to life. We have a team of like-minded people who work on the project on a regular basis and we call on all those who are not indifferent to the fate of herpetoculture as a hobby and business to join RHF! We are genuinely interested in representing active people from the private sector, the reptile industry, zoos and conservation!”

Herpetoculture is a complicated field with lots of interesting aspects. Although there will always be controversy around humanity’s relationship with animals, the hobby that promotes their responsible keeping of exotic pets is linked to

The learn more scan the link below or visit www.responsibleherpetoculture. foundation

21 APRIL 2024 The Devil in Disguise

IN THE VIVARIUM

Behind the scenes at Manchester Museum’s herpetology facility.

Manchester Museum is one of the largest university museums in the UK. Constructed over 130 years ago, the collection features millions of notable artefacts that are studied and observed by academics and visitors alike. Part of this catalogue is comprised of a living collection made up of a variety of neotropical amphibians with a primary focus on Costa Rican Anurans. As well as conducting behavioural and developmental studies, the collection dubbed “The Vivarium” also participates in a wealth of conservation projects to understand the environmental factors that are contributing to amphibian declines whilst educating visitors on the perils that face wild herpetofauna. Curator, Matthew O’Donnell has given Exotics Keeper Magazine a behind-the-scenes look at the work they are doing.

The Vivarium

The Vivarium was founded in 1964 and is currently maintained by three members of staff, as well as input from volunteers and students who are studying animals in the collection. The gallery features 11 exhibits, including two newly-built windows into off-show areas. “People are, apparently, really captivated by watching people clean frog tanks” joked Matt.

“90% of our time is spent behind the scenes so it’s great that visitors can now see what goes into maintaining these species. Part of our mission is to be open and transparent with the work we’re doing. We’re really proud of the research that we do here. It’s primarily conservation research and

usually involves developing interesting tools and techniques to protect some of the world’s rarest amphibians.”

The Vivarium works as part of a global network of conservation institutions with all species listed on ZIMS. The animals that are bred as part of developmental studies are generally of species requested from other institutions such as zoos and agricultural colleges. As part of the Manchester Museum, The Vivarium offers a valuable study opportunity with its living collection. From behavioural studies into foot-flagging behaviour with Staurios sp. to developmental studies with Cruziohyla sp., students are researching some interesting topics.

24 APRIL 2024 In The Vivarium

Species

The Vivarium houses around 30 different species of reptiles and amphibians. The most represented group are the leaf frogs of the Phyllomedusidae family. These include red-eyed leaf frogs (Agalychnis callidryas), black-eyed leaf frogs (A. moreletii), blue-sided leaf frogs (A. annae) and lemur leaf frogs (A. lemur). Within this family are also the fringed frogs of the Cruziohyla genus. “We have calcarifer, craspedopus and the more recently described sylviae which was described by the previous Curator of this collection, Andrew Gray” said Matt. “That description is science, it’s research and it evolved from learning about them in captivity. This is a fantastic example of having live collections in a museum setting. Not only do you have the taxonomic expertise you would associate with a natural history museum, but you also have a live collection so you can understand and learn things in that setting.”

The arboreal leaf frogs are maintained in a reasonably basic-looking setup. A terrarium with broad-leaved plants is kept at optimal environmental conditions and cleaned every day. This makes a perfect environment for the frog

but also offers important insight into maintaining captive amphibians for members of the public.

Matt continued: “The enclosures we use here are not sterile, but they are in a semi-sterile setup. We get a few people thinking they should be in a bioactive setup and I understand that because for some species, that can be a really positive way of maintaining them. However, tree frogs especially, live at different levels in the canopy, they don’t occupy that understory level that you would find a lot of the Dendrobatids. If you put a bioactive substrate in there, you are forcing that animal to live in the bottom few feet of the rainforest essentially. They don’t like it, they get covered in substrate that can lead to parasites and bacterial infections and they don’t live near as long.”

“These frogs breed on leaves overhanging pools, they aren’t even pond breeders, they are very specialist animals. It’s a methodology that works with these, but not with all species. We maintain the tanks for the needs of the species, not for the aesthetics of the public.”

25 APRIL 2024

In The Vivarium

Of course, there are numerous beautiful-looking exhibits within The Vivarium. From small display vivaria housing different localities of strawberry poison frogs (Oophaga pumilio) to large reptile exhibits housing emerald tree monitors (Varanus prasinus), Fiji banded iguana (Brachylophus fasciatus) and a handful of species used in educational displays such as panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis) and fat-tailed geckos (Hemitheconyx caudicinctus). The museum also showcases aquatic caecelians (Typhlonectes natans) and the Endangered golden mantella (Mantella aurantiaca).

The largest exhibit at the centre of the collection also showcases The Vivarium’s flagship species; the variable harlequin frog (Atelopus varius). As the only collection outside of the Americas to maintain and exhibit this Critically Endangered species, The Vivarium’s largest exhibit offers a window into a fragile Central American habitat. The enormous artificial rocky stream is home to a cohabiting community of neotropical anoles (Anolis biporcatus) and nine male Atelopus varius

Keeping and breeding Atelopus varius

The founding stock of harlequin frogs was given to Manchester Museum by Panamanian Government in 2019. Six newly-metamorphed frogs were shipped to the Museum and the collection has since bred to build a diverse colony of 30 adults. They are housed across five separate enclosures including one display exhibit, three smaller glass vivariums and one breeding tank.

The largest enclosure is equipped with a dedicated air conditioning system to retain a mild ambient temperature of around 21oC. An enormous lighting rig emits full-spectrum lighting and LED fixtures ensure the exhibit is well-lit. This is mirrored on a smaller scale in the other exhibits. Whilst all exhibits have dense foliage to provide security, the team at Manchester Museum have ensured that the females have access to even denser vegetation within their enclosures. Rarely do private herpetoculturists take the requirements of the sex of the animal into consideration when building an exhibit, so this thorough research on Atelopus has allowed the team to provide the best possible environment.

Matt explained “The males are far more visible than the females. They will occupy rocks around fast-flowing streams and remain exposed throughout most of the year. The females, on the other hand, live further into the forest. They will only venture to the streams when they are ready to breed.”

As well as exhibiting different behaviours, variable harlequin frogs also exhibit sexual dimorphism. Female A. varius are much larger than the males. However, as the scientific name suggests, they are extremely variable in both colour and size. In fact, for a long time, Atelopus varius was thought to be a locality form of the much larger and far more famous Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki).

Manchester Museum houses the males and the females separately in glass enclosures. “When the females are

26 APRIL 2024

In The Vivarium

ready to breed, they are visibly swollen with eggs and will head towards the front of the tank, attracted to the calling males in the opposite enclosure. They will stay at the front for a few days which indicates it is a female that is ready to reproduce. The female is then introduced to a room-temperature breeding tank (18-19°C). We have a pump creating fast-flowing oxygenating water. We let the female get accustomed to the tank for a day or two, then we introduce two males. The males don’t require any cooling, they’re ready to go! We put two males in to encourage them to go into amplexus quicker. Within a few days, the females should spawn, although in the wild they can remain in amplexus for months. We obviously don’t want to stress the females out too much so they will be separated after two weeks.”

Atelopus varius produce unpigmented eggs, meaning they are entirely white. These are laid in strings on the underside of rocks to protect the particularly sensitive eggs from UV light. Once they develop, the tadpoles are shockingly tiny, around the size of a comma (yes, <this big). The young are then fed a specially devised formula to support their unique feeding habits.

Matt continued: “We spoke to colleagues in Colombia who had kept and bred Atelopus and managed to develop a gel formula. We adapted this to use things we could find here. So, we used Allen Repashy’s products that he developed for fish. We used a mix of Super green, Soilent Green and Red Rum which has the same constituent parts that the researchers in Colombia were using. This gave the tadpoles the exact nutrient balance they required.”

Manchester Museum has been granted permission by the Panamanian Government to keep and breed the frogs, but they have not been permitted to move the frogs or their derivatives to any other collections. “We breed them as and when we desire them to back up our collection at the museum” added Matt.

“I understand there’s an argument for breeding some species in large numbers and releasing them to the trade and private keepers to prevent smuggling, but as soon as an animal’s origins become dubious it becomes very difficult to know if that animal was smuggled. At the moment, we are the only collection outside of the Americas with these frogs. If one turned up with a private keeper anywhere in the world, we would know it had been illegally smuggled and could act accordingly.”

Conservation of Atelopus varius

Matt’s research focuses on using eDNA to search for genetic materials suspended in aquatic systems. These materials degrade rapidly in rivers, streams, lakes etc so they can only be detected within 28 days. This means that he can effectively tell whether a species has been present in the area within the last month.

“Atelopus varius used to be fairly ubiquitous with mountain streams across Costa Rica and Panama. I’ve been to many sites where they used to occur in Costa Rica as part of my research into eDNA and we’ve been looking for varius as well as other Endangered or extinct species that used to occur in these sites and they are not there. They’ve completely vanished.”

The variable harlequin frog is now thought to only exist in around a dozen protected sites across Panama and Costa Rica. However, it does seem that these remaining populations are reasonably stable, in terms of declines linked to Chytrid. However, habitat alteration remains a major threat. Even the population from which the harlequin frogs at The Museum were collected (a population thought to be extremely stable and well-managed in a protected area) has disappeared as illegal logging has destroyed the site where they were found. With COVID preventing international teams from visiting the area, the natural resources that the frogs depend upon were destroyed.

27 APRIL 2024

©University of Manchester

Matt, along with a team of researchers helped to conduct the Costa Rican aspect of the Global Amphibian Assessment in 2019. “Since this species collapsed, and all but vanished in the 80s and 90s, many thought it would soon be extinct. Thankfully, populations have been discovered clinging on in several sites across Costa Rica and Panama. Some appear to be stable, and others might be increasing, but further research is required to know exactly what is going on.”

“There are studies looking at immune phenotypes,” said Matt. “These are unique adaptations of some amphibians that allow them to survive or are more resilient in the presence of Chytrid. There is some evidence that suggests some populations have increased immunity but it is also possible that the sites where they persisted have supported this. So, it might be that it’s too hot for Chytrid, or that there is more sunlight which can clear Chytrid as well. Many factors could be influencing the survival of these species.”

Wider conservation of amphibians Chytrid is particularly impacting high-elevation Bufonids. Genera such as Incilius and Atelopus are particularly imperilled. However, other Andean species in South America such as the water frogs of the genus Telmatobius are also at risk. Manchester Museum is also researching the impact of Chytrid on some Agalychnis species (leaf frogs of Central and South

America) to see how they are dealing with Chytrid. Species such as the black-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis moreleti) and the blue-sided tree frog (Agalychnis annae) have seen their numbers rebound after major crashes in the 1980s and 90s, prompting additional research into their resilience to Chytrid and other environmental factors.

Another species that Manchester Museum works with, that is closely related to Atelopus varius and has faced similar threats is Incilius holdridgei

“Holdridgei is a small, fossorial, inconspicuous toad that doesn’t have a call or display any particularly interesting behaviours. Because of this, it’s not the most inspiring species to get people excited about conservation, despite it being one of the rarest species on the planet. Atelopus on the other hand, has beautiful striking colours, interesting foot-waving communication, they are active during the day so our visitors can observe their behaviours, etc. That’s always going to be a more desirable species from a conservation perspective. Essentially, we are all fighting over a very small pot of conservation money so if we can capture the public’s attention and generate funds, it’s always best to go with the more visually appealing species. These are used as umbrella species, the funds that they generate support our work with species like Holdridgei. The threatened amphibians that live alongside Atelopus will benefit from the research and conservation that identifies and protects sites that Atelopus inhabit.”

28 APRIL 2024

In The Vivarium

29 APRIL 2024

RECREATING THE DESERT

Environmental research for horned lizards

By Benjamin Dragantha-Fabian

halimqd/Shutterstock.com

When contemplating the care of horned lizards, my vision consistently revolves around creating a naturalistic enclosure. I've dedicated considerable time to studying horned lizards in captivity, delving into a myriad of topics to ensure optimal care and enrichment for my animals. In a previous article for this magazine, I briefly discussed the enclosure design, lighting, and its desired appearance. Now, I aim to detail my process of recreating a segment of the natural habitat for horned lizards. From soil functionality to lights and plants, I intend to delve into every aspect and elucidate how it translates to my husbandry practices, impacting the well-being of my reptiles. Understanding the evolutionary context and environmental factors and figuring out how to adapt them to a smaller scale is crucial to mitigating numerous husbandry challenges.

Behaviour and Husbandry

Examining various facets of horned lizard anatomy, behaviour, diet, temporal activity patterns, thermoregulation, and reproductive strategies can be intricately connected and analysed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the ecology of these captivating reptiles. The possession of a substantial gut necessitates a tank-like body structure, reducing speed and limiting the lizard's ability for evasive flight from predators. Consequently, natural selection has favoured a spiky body form and secretive behaviour over a

streamlined physique and rapid movement, as observed in most other lizard species. The risks of predation are likely heightened during extended foraging periods in exposed areas. A tendency to minimize movement, even in the face of potential threats, could prove advantageous, as excessive movement might attract predators' attention and compromise the benefits of concealment through colouration and contour. This reduced movement likely contributes to the observed high variability in body temperature in Phrynosoma spp., surpassing that of all other coexisting lizard species.

32 APRIL 2024

Recreating the Desert

Recreating the Desert

halimqd/Shutterstock.com

Habitat description

As we already know, horned lizards occur in deserts and tend to occupy areas of loose soil and sand, dry riverbeds, grasslands and shrublands, as well as dunes and

volcanic areas. In the wild, these animals are exposed to extreme temperature fluctuations between day and night and across seasons. Temperatures can reach up to 50°C during the day and drop to as low as -5°C at night.

33 APRIL 2024

Recreating the Desert

Understanding the Desert

The Oregon Desert, often referred to as the “Oregon High Desert”, is part of the larger Great Basin Desert that extends into several western U.S. states. Oregon's high desert is characterized by arid conditions, low precipitation, and a variety of landforms. The soil and substrate in this region can vary, but there are some general aspects we can relate to while setting up the enclosure.

It's important to note that the Oregon Desert is not a uniform landscape, and there can be variations in soil and substrate composition across different areas within the region. Local geological features, climate patterns, and human activities all contribute to the diversity of soil types found in the Oregon Desert.

Plants & Soil

The vegetation in the Oregon High Desert is adapted to the region's arid climate, low precipitation, and harsh environmental conditions. While the vegetation can vary across different parts of the desert, several characteristic plant species are well-adapted to the challenging conditions of the high desert environment.

Many plants are xerophytic, meaning they are adapted to survive in environments with limited water availability. These plants have evolved various adaptations to survive in the arid conditions of the Oregon Desert, such as deep root systems to access water, drought-resistant foliage, and strategies to minimize water loss. The desert ecosystem is delicate, and these plants contribute to its unique biodiversity and ecological balance.

For example, Sagebrush (Artemisia sp.) is a common shrub

in arid regions like the Oregon Desert. While it can tolerate various soil types, sagebrush tends to prefer well-drained, sandy to loamy soils. Various species of bunchgrasses, such as bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) and Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), are also common. In nature these grasses play a crucial role in stabilizing soil, preventing erosion, and providing forage for wildlife.

Rabbitbrush is a shrub that is well-adapted to the dry conditions of the high desert. It produces yellow flowers and is an important component of the desert ecosystem, providing food and habitat for various insects and small animals.

In addition to many more plants, the desert soil is home to cryptobiotic soil organisms, including lichens, mosses, and cyanobacteria. These organisms play a crucial role in stabilizing the soil and preventing erosion.

The soil pH in the Oregon Desert exhibits variability, with many areas tending to be alkaline. Alkaline soil typically registers a pH level above 7.0, ranging from moderately to strongly alkaline, influenced by factors such as local geology, parent material, and the presence of alkaline minerals.

The alkaline nature of the soil can be attributed to the region's geological history, including volcanic activity. Common volcanic rocks like basalt, prevalent in the area, contribute to soil alkalinity through weathering processes.

Certain areas may contain sediment and soil deposits transported by water, especially in proximity to rivers or former watercourses. Horned lizards utilize loose soil for camouflage and thermoregulation.

35 APRIL 2024

The following enclosure design is based on a desert horned lizard (P. platyrhinos) habitat in the Oregon Desert.

Brendan B/Shutterstock.com

Light

Sunlight consists of particles known as photons, which serve as the fundamental units of electromagnetic radiation. Photons, discrete packets of energy, demonstrate both wave-like and particle-like characteristics. In the context of sunlight, these photons emanate from the Sun due to nuclear fusion reactions transpiring in its core.

Comprehending the role of distinct wavelengths in sunlight is pivotal for establishing appropriate captive environments for reptiles. In captivity, artificial lighting systems are frequently employed to furnish the requisite spectrum, encompassing UVB, UVA, visible light, and infrared. Customizing lighting configurations based on the specific needs of the reptile species, considering their natural habitat and behaviour, is imperative.

Light holds paramount significance as an environmental factor for reptiles and plants, influencing diverse aspects of their behaviour, physiology, and overall well-being. Several key properties of light are vital for reptiles. While UVB is often perceived as the primary aspect of light in the hobby, and infrared is commonly regarded merely as a means of providing heat, offering the right combination of light sources can profoundly benefit the reptile's comprehensive care.

Reptiles frequently manifest specific behaviours and physiological responses aligned with the natural day-night cycle. Establishing a consistent photoperiod that mimics their native environment is crucial for upholding normal biological rhythms, encompassing activities such as feeding, breeding, and thermoregulation.

UVB (280-315 nm): Reptiles require UVB radiation to synthesize vitamin D3 in their skin, a crucial element for calcium metabolism, necessary for proper bone development and maintenance. In captivity, artificial UVB lighting is commonly used to ensure this need is met, mimicking the natural process where reptiles bask in sunlight to absorb UVB radiation.

UVA (315-400 nm): UVA radiation is also significant for reptiles, contributing to their overall well-being, and influencing feeding, mating, and behavioural patterns. Although not directly involved in vitamin D synthesis, exposure to UVA is considered beneficial for the psychological health of reptiles.

Visible Light (400-700 nm): Present in sunlight, visible light can impact reptile behaviour, affecting activity levels, feeding, and other physiological processes. Blue light is often incorporated into artificial lighting for reptiles to replicate natural conditions. While specific effects of visible light on reptiles are less studied compared to other wavelengths, it is generally recognized as part of their natural lighting environment.

Infrared (IR) Radiation (>700 nm): Infrared radiation provides the heat component in sunlight. Given their ectothermic nature, reptiles rely on external heat sources to regulate body temperature. Basking in sunlight or under heat lamps allows reptiles to absorb infrared radiation, aiding in maintaining optimal body temperatures for metabolic activities.

36 APRIL 2024

Recreating the Desert

Brian Lasenby/Shutterstock.com

100% NATURAL PEST CONTROL

TAURRUS® is a living organism (predatory mite) that is a natural enemy of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis).

TAURRUS® mite predators are very small, measuring less than 1mm as adults. They are able to live for several weeks and reproduce in the areas where they find their prey. Despite its small size, the TAURRUS® predator acts aggressively and is able to attack and kill preys 3 to 4 times larger than itself.

Once released, the microscopic predators will actively seek and consume parasites. Once eliminated, the predators disappear naturally. The mode of action requires several days. After introduction of TAURRUS®, pest populations should be monitored: at first it will stabilize, and then gradually decline. In heavy infestations, several releases may be needed to eradicate all parasites.

37 APRIL 2024

Recreating the Desert

Enclosure preparation

The foundations to my enclosures are wooden vivariums measuring 120cm x 60cm x 60cm (4x2x2). They are sealed with a water-based varnish and silicone to preserve moisture and provide protection against it. These enclosures are equipped with pre-drilled ventilation holes. Considering the need for a deep substrate layer for horned lizards, I added extra lower ventilation intakes at approximately 18cm from the bottom. Additionally, a 14mm hole was drilled to allow the passage of a hose, which will serve as an intake for watering the deeper levels of the substrate.

Horned lizards have high light requirements that need to be met. Some lamps may have a more balanced spectrum, closely resembling natural sunlight, while others may need to be supplemented with specific wavelengths. In general, it’s a good practice to combine lamps that are good at replicating one aspect of the sun's spectrum. While in Europe, UVB-producing Metal Halides are often used mistakenly as an “All in one” light source, they lack in some aspects and the UVB emitting parts can burn quicker than other elements.

For my enclosures, I use non-UVB-producing Metal Halides

as a source of UVA and Visible Light. As a UVB Source, T5 tubes from reputable brands are very reliable in providing a stable output of UVB over a long time. For horned lizards, 12% or 14% (depending on enclosure height) are suitable. The fixture is attached to a wooden wedge to enable a light angle and better coverage at the basking zone.

Incandescent lamps emit infrared radiation, which is important for providing warmth to reptiles. Infrared heat is essential for maintaining the proper ambient temperature in the terrarium, especially during the night when visible light may not be needed. I set up those lamps in a “sun patch” orientation, maintaining the basking area the brightest. On this side I let the beams from all lamps overlap in one area while the other side will be more “shaded”.

The LED bar spans most of the enclosure's length, illuminating the plants, while UVB, heat, and Metal Halide are concentrated on the opposite side. It's crucial to stagger the lighting to mimic the day and night cycle. In the morning, the incandescent heat lamp activates first, followed shortly by the gradual increase of the dimmable LED bar over an hour. In the middle of this process, the UVB ramps up over 15-30 minutes, and finally, the Metal Halide simulates the midday sun.

38 APRIL 2024

reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

Assessing UVB, Brightness, Temperature, and Power Density

For horned lizards, a targeted UVI range of 4.5-9.5 is recommended for the basking spot. The basking area should be the most luminous and warmest segment, reaching temperatures between 42°C and 45°C. In contrast, the shaded side should experience a significant temperature drop, ranging from 25°C to 28°C.

The collective brightness, gauged through Lux as a proxy, should be a minimum of 50,000 lux at the brightest spot where all light sources converge.

Surface temperatures can vary a lot through the colour and properties of the rocks and sand. The variation between a bright and dark rock can make up to 10°C difference. The mixing of different light sources with different spectre will also affect radiation.

Since surface temperatures on basking spots don't accurately reflect their output, we must turn to a different metric known as "power density," measured in watts per square meter. Power density, like intensity, measures the energy flow from a lamp. Much like UVB provision, the provision of IR-A (mainly emitted by a basking lamp at full power) remains consistent and is unaffected by temperature.

To achieve an optimal level of approximately 300-350 W/ m^2 of IR-A, suitable for a horned lizard resembling midmorning IR-A levels, is the goal. Surface temperatures only become relevant once the correct IR-A power density is achieved. If temperatures are excessively high despite the correct power density, adjustments to the surface are necessary. The precise surface temperature is not critical; it can fluctuate within a comfortable range as long as IR-A provision remains stable and accurate.

Constructing the Substrate Layers

Horned lizards instinctively seek shelter or bury themselves in deeper substrate layers for thermoregulation and concealment. Deep substrate proves essential during brumation, offering isolation and a consistent, suitable temperature. This is particularly beneficial when females create egg chambers. Ideally, the substrate depth should range from 10 to 20 cm.

In the drainage layer, the initial setup involves a silicone hose, capped off, anchored at the bottom, and cut at 5 cm intervals. This design facilitates external watering of the deeper layers, benefiting both plants and reptiles. The drainage components consist of hydroculture balls and lava rock, effectively collecting and retaining moisture, and distributing it across the layered structure.

Once the drainage is in place, the first layers of substrate (each approximately 2-3 cm thick) can be added. This mixture comprises play sand, organic topsoil, and clay. The first three layers incorporate minerals to elevate the pH, aiming for a more alkaline substrate.

The subsequent three layers emphasize play sand, reducing the amount of topsoil and clay. This adjustment aids water percolation to the drainage, maintaining a dry surface while allowing plant access to water.

To enhance the naturalistic environment and cater to reptile needs, crushed red and black lava rock, along with play sand and small gravel, are incorporated. This not only aids camouflage but also complements the overall habitat.

The final layer will comprise various materials, either purchased or naturally sourced, such as dried grasses, brushes, and leaves. This addition aims to introduce more diversity and create microclimates, providing additional hiding spaces for the inhabitants.

39 APRIL 2024 Recreating the Desert

IrinaK/Shutterstock.com

Recreating the Desert

Décor and Plants

When establishing the primary lava stones for the basking area, it's crucial to ensure they are at the right distance from the lights and securely positioned to prevent animals from burrowing underneath. To address this, I placed my two main basking stones on top of old bricks, effectively eliminating the issue and rendering the space beneath the rocks accessible. Additionally, the other selected pieces are both functional and aesthetically arranged, with proper securing measures in place. Precautions must be taken to avoid accidents resulting from inadequately secured decorations.

Obtaining plants from North America can pose a challenge, often involving the purchase of seeds and the cultivation of plants from scratch. During your plant research, consider exploring substitute species available in your local area. I have introduced Sagebrushes (Artemisia cana) that I cultivated into the enclosure. As a substitute for a native Achnatherum spp., I identified another subspecies with similar requirements.

All the plants are planted in pots with the same mixture available in the enclosure. While these plants are adapted to the conditions we aim to replicate, providing a means to directly address their needs is advisable. Planting them

directly into the soil might impede maintenance and reduce usable space for the lizards.

Once the setup is finished, I proceed with the cycling process. During this period, the plants can establish and grow while I monitor the temperature and UVI. Additionally, I determine the appropriate wattage for both the heat source and metal halide lighting.

Bioactive Boom

A bioactive reptile enclosure is designed as a vivarium to emulate a self-sustaining ecosystem within the reptile's habitat. In contrast to conventional reptile setups relying on artificial substrates and decorations, bioactive enclosures integrate living organisms like beneficial bacteria, fungi, plants, and invertebrates to establish a dynamic and harmonious environment. While the trend has enhanced enrichment by pursuing a more naturalistic setup, the actual creation of a bioactive enclosure is often misunderstood.

For horned lizards, I do not recommend opting for a bioactive approach. The primary reasons include the need to closely monitor their food availability in preparation for brumation, and the desert conditions we aim to replicate are not particularly conducive to bioactivity on a smaller scale.

40 APRIL 2024

Jason Mintzer/Shutterstock.com

APRIL 2024

reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

SAND SNAKES: A NATURAL HISSSTORY

By Francis Cosquieri

The hissing sand snake is a slender-bodied, venomous snake from North Africa. Poorly represented in the hobby, these unique reptiles were occasionally imported from Egypt in the early 00s, with only a handful of enthusiasts keeping and breeding the species. One such enthusiast is Francis Cosquieri, a specialist snake keeper from Gibraltar. The following feature discusses his extensive research into the husbandry of these little-known animals.

About the Author:

Francis Cosquieri is a key figurehead in British herpetoculture. An avid “herper” and longstanding keeper and breeder of reptiles, his fascination for unusual Colubrids has been eternalised in articles, lectures and forum posts. Francis combines his field observations with pioneering husbandry practices to contribute helpful information to both new and experienced keepers alike.

Appearance & Sexing

The Hissing sand snake is a medium-sized Psammophiine snake that can reach a total length of 144cm. It is slim and elegant snake with an elongated head and large eyes sporting round pupils. The tail is relatively long and attenuate and accounts for about a third of the length of the snake.

In coloration this is a variable species. Generally, the body

is brownish with a cream or yellow vent that sometimes has two thin brown or reddish lines along the edges. They also typicall have longitudinal striping. Both sexes are almost identical in appearance so the best way of sexing them is to look at the snake’s shed skin. In males, the hemipenis will also shed and these can easily be seen on the snake’s shed skin. While it is not always a conclusive method, waiting for three sheds to check should reveal a snake’s sex.

44 APRIL 2024

Sand Snakes: A Natural Hissstory

Sand Snakes: A Natural Hissstory

A note on names: Like many species, Psammophis sibilans goes by several vernacular names. This species has been referred to as the African Beauty Snake, Olive Grass Snake, African Sand Snake, African Sand Racer, African Grass Snake, African Whip Snake, Striped Whip Snake and others. Since the etymology of the name Psammophis sibilans literally translates as “Hissing sand snake” this is the common name that will be used here.

Distribution, Habitat and Ecology

The true distribution of the Hissing sand snake remains an issue, as the currently recognised range probably includes that of several species formerly assigned to this taxon. Historically, the range includes northern Africa from Algeria to Egypt (but not Morocco) and as far south as Angola, Zaire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and as far east as Somalia and Eritrea.