SURELY, YOU CAN DO BETTA?

The complete line of Exo Terra®

The complete line of Exo Terra®

The new range of Exo Terra Thermostats makes regulating the temperature of your reptile’s home accurate, reliable and simple. With thermostats suitable for any heat source and utilising the latest technology with day/night timers and humidity control*, you can rely on Exo Terra to keep your reptile’s habitat perfectly balanced, 24 hours a day.

Available from all good reptile stockists nationwide. *Day/night timer and humidity control on selected models only

CONTACT US EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES editor@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS craig@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING advertising@exoticskeeper.com

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex

CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4675

Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

Aimee Jones

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Stonesmith

Welcome to the March edition of Exotics Keeper Magazine - issue five, would you believe it? While you can’t beat a printed magazine, you can enjoy this magazine via our App on the Apple and Google app stores now.

In this issue we speak to Ben Tapley, Curator of Herpetology at ZSL, about the grave Chytrid fungus affecting amphibians around the world. We dive into the world of Betta, discussing everything from diversity to husbandry with guest writer Max Pedley. Royal pythons and the pygmy flying mouse face the species spotlight, uncovering some lesser-known facts of these pet shop favourites.

Aimee Jones shares her experience working with leaftailed geckos in Madagascar and we discuss eight of the most interesting Arachnids in the trade, from beginner Brachypelmas to professional Pokies.

As we continue to expand our team, you can expect to continue to see each issue packed with a diverse selection of content. If you haven’t setup a subscription already, speak with your local stockist or head over to our website to make sure you get the latest copy each month.

Craig Thornton

Vivexotic is renowned for its quality, great value and useful features and now the ever popular Repti Home range is available in a cool grey finish! Bored with oak? Does walnut clash with your decor? Match your viv to your living space with the new Repti Home grey range, available from good reptile stockists nationwide.

02 EXOTICS NEWS

16

06 THE CHYTRID CRISIS

14

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s the Pygmy Flying Mouse (Acrobates Pygmaeus).

24 26 36

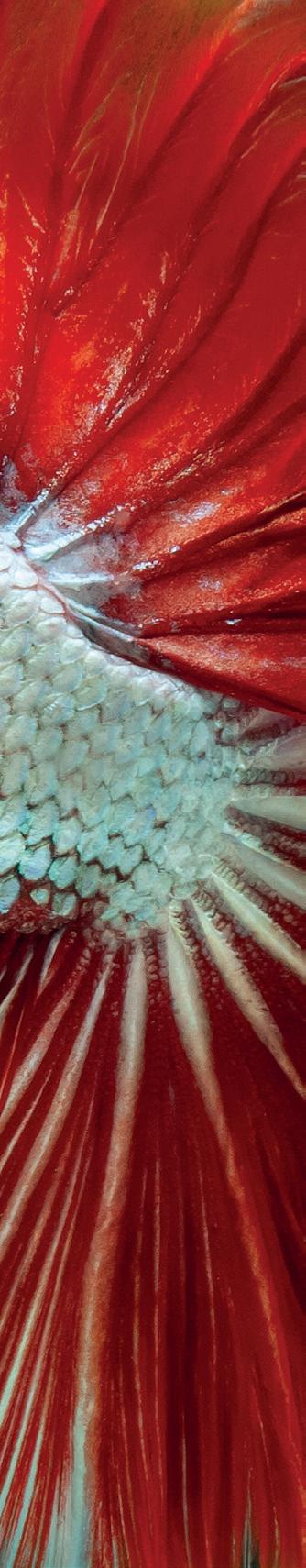

SURELY, YOU CAN DO BETTA?

How Betta splendens is fighting for its future.

24

26

ANIMAL FACTS

Did you know...?

ARACHNIDA FEVER

From beginner Brachypelmas to professional Pokies, we discuss eight of the most interesting arachnids in the hobby.

36

LEAF-TAILED GECKOS

Aimee Jones tells us how these beautiful Geckos are struggling in the wild and looks at conservation efforts.

42

EXPERT OPINION

Rethinking Husbandry with Rebecca Taylor of Becks Bird Barn.

A male greater kudu has arrived from Dvur Kralove in the Czech Republic. Meanwhile at sister collection Port Lympne Hotel & Reserve a male European bison, bred at the collection, departed on a journey of over 1,400 miles to the Fagaras Mountains in Romania, as part of the Aspinall Foundation`s “Back to the Wild” programme to reintroduce the bison back into the region.

Male Amur tiger “Miron” (born at Moscow Zoo 2014) has arrived from Copenhagen Zoo to pair with their female “Sinda” as an EEP breeding recommendation. However, the move is with some trepidation, as he did kill his mate at Copenhagen Zoo in 2018.

Following the collection of the last remaining 14 Loa water frogs (Telmatobius dankoi) from a drying pool in Chile, the Zoologico Nacional de Chile successfully bred the Critically Endangered frogs in October 2020 for the first time, with 180 tadpoles hatching. Then in December 2020 a further 250 eggs were produced and these have since hatched at the National Zoo

Native Amphibian Reproduction Center in Chile. The species was only discovered in 1999 and is Chile`s most endangered frog.

So it is hoped that the species will be reintroduced back into the wild at a future date when a suitable habitat is found for them.

Scientists from the BioRescue Project have been working with the last two remaining female Northern white rhinos, which are located at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Africa, in a last ditch attempt to save the species. The aim is to transfer harvested and fertilised eggs, from the females “Najin” and her 20 year old daughter “Fatu”, and place them in surrogate Southern white rhinos by artificial insemination. Fourteen eggs were recently collected from “Fatu” using an ultrasound-guided probe, and of these eggs two were successfully fertilised using the frozen sperm (from one of the last males before they died), with the chance of developing into viable embryos. Unfortunately no healthy eggs were harvested from “Najin” probably due to her advancing age (31 years) and her poor health – she has an abdominal tumour, which may have hampered the functionality of her reproductive organs.

It is thought that the team have succeeded in creating five potentially viable embryos.

A group of Lowland gorillas are thought to be the first zoo-primates to have been infected with the Covid-19 virus. It is believed that they contracted the virus from an asymptomatic keeper working with them at San Diego Safari Park. The park’s executive director, Lisa Peterson, told the Associated Press that eight gorillas who live together at the park are believed to have the virus and several have been coughing. Gavin Newsom, California’s governor, confirmed that, in the group of eight gorillas, at least two gorillas had tested positive while three were symptomatic. The safari park confirmed the presence

of Covid-19 through faecal samples from the gorillas. Veterinarians are closely monitoring the gorillas, they are being given vitamins, fluid and food, but no specific treatment for the virus. Aside from some congestion and coughing, the gorillas are apparently doing well. The group remain quarantined together and are eating and drinking normally.

Until now the only zoo animals infected by the virus had been big cats - a four-year-old Malayan tiger named “Nadia” at the Bronx zoo in New York in April, and shortly afterwards, three other tigers and three lions at the same zoo as well. “Bashir”, an 11-year-old Malayan tiger at the Knoxville zoo in Tennessee, tested positive for

coronavirus in October and went into quarantine with the Malayan tigers “Arya”, 6, and “Tanvir”, 11, who were also displaying mild coughing, lethargy and a decrease in appetite. Then “NeeCee”, a five-year-old snow leopard at the Louisville zoo in Kentucky, tested positive.

All have now recovered.

Another case of covid-19 was recorded recently in four lions at Barcelona Zoo in Spain. Two staff also had the virus. It is known that all felids can carry, or be affected, by covid-19 (the same can be said for various other species, for example large numbers of farmed mink in the Netherlands have had to be culled in recent months for the same reasons).

Scientists, led by the American Museum of Natural History, were conducting field surveys of the caves and mining tunnels in the Nimba Mountains of Guinea in West Africa, when they discovered an unusual bat for the first time in 2018. They were looking for the rare Lamotte`s roundleaf bat (Hipposideros lamottei) which is only found in this area, when they noticed another bat in the same location, which was a large orange and black species.

This previously unknown species has now been officially named as Myotis nimbaensis (also known as the Orange-furred bat), and due to its restricted location, it is likely that this species will be regarded as Critically Endangered.

A research team from the University of Helsinki recently spent three months studying the night-time calls of nocturnal species in the Montane Forests of Kenya and they believe they have discovered a new species of tree hyrax in the Taita Hills region that was previously unknown to science. The discovery was published in the mid-December edition of the scientific journal Discovery

Very little is known about the diversity and ecology of tree hyraxes because these animals are mainly active at night in the tree canopies of Africa’s tropical forests. These animals are known to be able to scream with the strength of more than one hundred decibels, but the ‘strangled thwack’ calls that have been recorded in Taita’s forests have not been described anywhere else. The tree hyrax song may continue for more than twelve minutes, and it

consists of different syllables that are combined and repeated in various ways.

In addition the team also discovered the following;

The calls also suggest that the two populations of dwarf galago in the Taita Hills may belong to different species. The calls of the animals of the smaller population are very similar to those of the Kenya coast dwarf galago, a species that has previously been thought to live only in coastal, low elevation forests. The peculiar calls of the second population cannot yet be linked with certainty to any known species.

Sources; The Ol Pejeta Conservancy, San Diego Zoo/www.theGuardian.com, Bat Conservation International/www.theIndependent.co.uk. The Discovery Journal.

Collated and written by Paul Irven.

Spearheaded by midlands teenagers, Harvey Tweats and Tom Whitehurst, Celtic Reptile & Amphibian is European herpetofauna conservation with the largest European captive breeding facility in the UK

www.celticreptileamphibian.co.uk

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page.

Amphibians are currently facing what is possibly the most catastrophic crisis in their evolutionary history. Presenting many parallels with the COVID-19 pandemic, a devastating fungal disease has spread worldwide.

Panamanian Golden Frog (Atelopus zeteki)

Chytrid Fungus Amphibian Crisis

Panamanian Golden Frog (Atelopus zeteki)

Chytrid Fungus Amphibian Crisis

Chytridiomycosis is a disease that attacks amphibians’ moist skin and is responsible for the decline of over 500 species. Although it has been known to scientists for decades, the impact of a new pathogen which is lethal to some salamanders could spell disaster for some of Europe’s most iconic amphibians. While deforestation and climate change are major drivers of extinction at present, amphibians are also threatened by the suite of virulent pathogens that cause Chytrid. To understand the scope of the amphibian crisis, we spoke with Benjamin Tapley, the curator of herpetology at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

As curator, Ben ensures that the collection of reptiles and amphibians at London Zoo is comprised of the most significant priority species relevant to the conservation aims of ZSL. In addition, Ben works on conservation projects in the field, and much of his work is focused on Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species.

Ben has mentored and trained others in the field to work with amphibians, monitor their pathogens, and maintain healthy captive collections for conservation purposes. This is extremely important particularly for species that will be translocated at a future date back into their natural habitat to establish new breeding populations. These translocated animals need to be physiologically and genetically healthy for the program to be successful.

Since its discovery in 1998 there have been significant developments in the Chytrid saga. Although some success stories have surfaced, the picture remains very bleak. Ben explained: “In a snapshot, these pathogens pose a major conservation challenge, there are no pathogens comparable to them in terms of the number of species they infect and their global range; their impact as drivers of biodiversity loss is unparalleled.”

A review from the academic journal Science in 2019 stated that the disease chytridiomycosis was a factor in the decline of at least 500 species of amphibian in the last 50 years, and declines >90% in more than 100 species. Alarmingly, the study also presumed ‘extinction in the wild’ of 90 amphibian species as a result of the disease.

Chytridiomycosis is caused by amphibian chytrid fungi. Scientists have known about one of these chytrid fungi, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (often abbreviated to Bd) for decades. In 2013 another chytrid was identified as causing population declines in European salamanders. This chytrid, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal for short) is likely to have originated from East Asia. Chytrid mediated declines have not been reported in Asia and it is now thought that chytrids originated from this region and that global trade facilitated their spread around the world. These pathogens are likely to have spread via the trade of laboratory animals, or via stowaway amphibians from other regions hitching a ride in cargo, like food, and finding their way into the environment. There is also concern around wastewater being introduced into the environment from captive, non-native amphibians.

Chytrid fungi can infect a wide variety of host species; some

FACT FILE: BATRACHOCHYTRIUM DENDROBATIDIS

DESCRIBED: IN PANAMA AND AUSTRALIA, 1999, BY LEE BERGER

CONTINENTS AFFECTED: NORTH, SOUTH AND CENTRAL AMERICA, ASIA, AUSTRALIA, AFRICA, EUROPE

EXTINCTIONS: 90+

SPECIES AT RISK: VIRTUALLY ALL FROGS, TOADS AND EVEN CAECILIANS; HUNDREDS OF SPECIES IN DECLINE WITH BD AS A LIKELY CONTRIBUTOR

MODE OF TRANSMISSION: CONTAMINATED WATER/MOIST SURFACES; DIRECT CONTACT

INCUBATION TIME: 14-70 DAYS

SYMPTOMS: RED/DISCOLOURED SKIN, LESIONS, ABNORMAL BEHAVIOUR/LETHARGY/POSTURE, SUDDEN DEATH

TREATMENT: ANTIFUNGAL BATHS, HEAT TREATMENTS, SODIUM CHLORIDE

PREVENTION: ISOLATION

asymptomatically. These species may act as reservoirs of infection that facilitate the spread of the pathogen in their environment.

“Susceptibility does vary between species, and it may even vary between life stage as well,” Ben commented. The zoospores of the fungus are motile in water and require cool, moist conditions to survive. Amphibian skin works in complex ways to allow respiration, thermo- and osmo-regulation. Chytridiomycosis disrupts the water and mineral balance of diseased amphibians. This results in death, normally because of electrolyte imbalances that lead to heart failure.

Ben has been working with Leptodactylus fallax, otherwise known as the ‘mountain chicken’ frog (which does indeed get its name for culinary reasons) for 15 years. This species exhibited one of the most rapid declines documented in a vertebrate after chytrid fungi arrived on the eastern Caribbean islands of Dominica and Montserrat. More

than 80% of the population was lost in just 18 months, with the species thought to be extinct in the wild on Montserrat. To combat this, a captive breeding project was established for future reintroduction of the species to Montserrat as a result. Sadly, there are only around 100 individuals remaining in Dominica.

Ben was also part of a team that documented the first known case of lethal chytridiomycosis in a caecilian amphibian and went on to develop a treatment with veterinary colleagues at ZSL London Zoo. Caecilians are limbless amphibians and the majority of species live underground which means that they are rarely encountered and poorly studied.

Another example of a species that has been dramatically affected by Bd is the Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki). In addition to being threatened by the loss of habitat and the impact of climate change, in 2004 chytridiomycosis ripped through the local population very quickly. The IUCN currently lists this species

as Critically Endangered, but some speculate it may already be extinct in the wild as it has not been documented since the filming of David Attenborough’s Life in Cold Blood in 2006. Captive breeding and recovery plans are in place with around 500 individuals successfully produced so far.

In 2013, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans was discovered. It is highly likely this pathogen arrived in Europe via the pet trade, and it has already caused catastrophic population declines in fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) in the Netherlands. Laboratory studies have confirmed that many salamanders are highly susceptible to Bsal. The Americas are particularly rich in salamander species and the spread of Bsal to the region could be a disaster for the region.

In response to this, there are now trade restrictions to protect salamanders in the US and in the EU. In the US, the Lacey Act aims to protect native salamanders from Bsal. Particular species of salamander (201 species of 20 genera) have been listed as ‘injurious’ to native species, and so both importation and interstate transport of those species is prohibited without a permit. This even includes dead salamanders or tissue samples. Authorisation to trade salamanders within the United States can only be granted on the grounds of medical, scientific, zoological, or educational purposes.

The European Food Safety Authority is associated with the regulation of salamander trade for the EU. They state the

following protocols: Quarantining, testing, and demonstrating that salamanders are free of infection by Bsal; restricting movements of salamanders; hygienic procedures and biosecurity measures; treating of salamanders for Bsal. Appropriate establishments must be assessed wherein the testing and quarantining of salamanders can take place under competent veterinary supervision. Salamanders can only be moved within the Union if they have tested negatively for Bsal following quarantine and are accompanied by an animal health certificate.

This does make one wonder about how our own laws in the UK regarding amphibian protection may change following Brexit. According to UK government publications, similar rules are in place, requiring appropriate establishments approved by the Fish Health Inspectorate (FHI) for

Corsican fire salamander (Salamandra corsica)quarantining and testing of salamanders and newts (Caudata) that are being imported or exported from within/out the EU. Even moving salamanders between England and Wales requires health certification from the FHI, which is only granted following a quarantine or treatment period.

All of this is for good reason, as the UK should do its upmost to protect native species – such as the great crested newt (Triturus cristatus). Laboratory trials have shown that they are indeed susceptible to Bsal. Bd has already been detected in the UK in several locations but Bsal has not been recorded in native amphibians and we need to keep it this way.

You can help to protect UK amphibians by not contributing to any further spread of chytrids with some simple methods.

Ben recommends keeping amphibians indoors so that pets do not come into direct contact with native species, especially as the vast majority of amphibians in the hobby are not native to the UK and could harbour dangerous pathogens. He also recommends that keepers do not throw wastewater from amphibian enclosures out into the environment unless it has been effectively disinfected first. Finally, he suggests that people report any sick or dead amphibians to local wildlife councils, of which there are several accessible through Amphibian and Reptile Groups of the UK (ARG UK). Ben also advises using the clear guidance outlined in the Amphibian Disease Alert produced by gardenwildlifehealth.org to protect both pet amphibians and native wild species. Whenever receiving new amphibians, particularly those species that may be wild caught, it is sensible

to isolate and observe them in a quarantine setting to catch any signs of disease early.

Knowing that chytrid can infect a huge array of amphibian species and persist in the environment, it presents a massive challenge in trying to control it before before it further imperils amphibian populations. There are, however, a vast number of people, including Ben working to figure out this problem with some positive outcomes.

Many species, such as the mountain chicken and golden frog mentioned previously, have safety net populations in captivity, sparing them from outright extinction and buying time to develop conservation plans. When chytrid arrived at Montserrat, fungal baths were also used to experimentally treat wild mountain chicken frogs and all individuals were tracked over time as they were marked with a microchip. Ben continued: “The treatment with antifungal baths in the field would probably not have prevented extinction – but populations would have persisted for longer. What that means is that it buys a couple of months for facilities to be set up for a conservation breeding program or to develop other mitigation strategies.”

In some areas, scientists have observed populations of species usually affected by chytrid, surviving in atypical habitats that are likely slightly hotter and drier than their usual habitat. It has been hypothesised that these populations persist because Bd is sensitive to high temperatures (>30°C) and desiccation. Could this information aid the recovery of species currently facing extinction?

On Montserrat in the eastern Caribbean, the Mountain Chicken Frog Recovery Programme is implementing a field intervention initiative where ambient temperatures in semi-wild enclosures on the island are raised. This is achieved by removing canopy cover so that conditions are favourable for captive reared and released frogs - but less favourable for Bd. Furthermore, these enclosures contain ponds that are heated to temperatures that will kill Bd (>30°C); when amphibians become clinically ill with chytridiomycosis they spend prolonged periods of time in water as they have osmoregulatory difficulties, so heated ponds will provide an area where frogs can reduce chytrid infection burdens. The team at ZSL London Zoo tested whether frogs used the heated water baths before any interventions were made in the field. Heated water baths were placed in mountain chicken enclosures at ZSL London Zoo in addition to water baths of standard temperature. Time lapse footage was used to monitor usage and the heated water baths were widely used by the captive frogs, with some individuals showing strong preference for heated baths over background temperature, with no observed negative impact.

Another method was tested in Mallorca where isolated populations of the Mallorcan midwife toad (Alytes muletensis) were infected with Bd. Midwife toad larvae were removed from site and treated for Bd. At the same time the entire environment was exposed to a chytrid-killing, biodegradable disinfectant. Chytrid appeared to have been successfully removed from a site for the first time. Whilst offering a glimmer of hope, this work was undertaken at a site with just one amphibian species and it would be incredibly difficult to apply this method to more complex, species-rich systems.

Treatment protocols for captive amphibians have also been further developed, even for poorly

known species of caecilians. The caecilian species Geotrypetes seraphini and Potomotyphlus kaupii were treated using 0.01% solutions of the antifungal itraconazole for 30-minute immersions over the course of 11 days. The treatments were considered successful when at least 2 tests for Bd came back negative after treatment periods. This provides a promising outcome, at the very least, for captive populations that become infected with Bd. Other species can be treated by adapting methods used for frogs to other members of Amphibia.

These methods do have somewhat positive outcomes but are only applicable in certain circumstances. “You need to choose your treatment depending on the context of the species you want to treat,” Ben told us. “For Bsal, there are antifungal and heat treatments – but salamanders often live in cool areas, so heat treatment may not be a viable treatment for all salamanders. But there has been far less research undertaken to date on treatment for Bsal.”

We asked Ben about the role that private hobbyists might play in the quest to preserve species in captive environments alongside zoos and conservation organisations. He answered, “When it comes to establishing conservation breeding programmes in the private sector, it can be difficult to regulate how they operate, but there are cases where private breeders have been involved in programmes.

I think that the collaboration between zoos and private keepers is really important because often, the private keepers dedicate a huge amount of time and effort into one particular species – and often their skills and knowledge of a particular species is unparalleled.”

Reliant on income from ticket sales to care for the animals at their two zoos, ZSL London and Whipsnade - and to fund ZSL’s global conservation and science work - enforced closures as a result of the January lockdown have put the international conservation charity under huge financial pressure. Vets and zookeepers will continue to provide the highest level of care for their animals, working throughout the lockdown. ZSL is calling on the public to help ensure they remain open by donating to ZSL at www.zsl.org/donate

One of the main hurdles to amphibian conservation is a lack of resources and funding. Conservation funding is often allocated to more charismatic mammals and birds that people are more familiar with. We often see images of lions, rhinos and pandas on our television screens (and rightfully so!) – but support and interest from the public in the conservation of herpetofauna is next to non-existent in comparison.

It is worth hoping that these discussions will help the plight of amphibians reach a wider audience so a greater diversity of people may understand that the loss of hundreds of amphibian species is a very real threat. But why should they care?

Herpetofauna, amphibians included, play key roles in their natural ecosystems as both predators and prey. Removing one link from the food chain can have very disastrous effects on all the other organisms in that area. In fact, a recently published study found a relationship between chytrid driven amphibian declines in central America and increased instances of malaria outbreaks. So, it really isn’t just about animal ecosystems – it all comes back to us too.

By supporting the work at ZSL, you support the work that goes into conservation, including the challenge of tackling the global amphibian crisis and preserving these amazing little creatures for generations to come and the benefit of everyone.

“A RECENTLY PUBLISHED STUDY FOUND A RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CHYTRID DRIVEN AMPHIBIAN DECLINES IN CENTRAL AMERICA AND INCREASED INSTANCES OF MALARIA OUTBREAKS”

Australia’s East coast is home to some truly remarkable marsupials. However, the pygmy flying mouse (Acrobates pygmaeus) or ‘feathertail glider’ takes the title for most adorable.

This tiny gliding possum weighs less than 13 grams, with a body length of just 80mm. In fact, this mini marsupial is so small that it has significant trouble keeping warm. Because of this, the pygmy flying mouse can enter a state called torpor which slows the animals breathing, often leaving them totally unresponsive for a

short while.

Also known as the feathertail glider, this species gets its name from the feather-like structure of the stiff hairs on its tail. This is designed to

allow the tiny possum to steer direction whilst using their under-arm skin folds to glide through the air. The pygmy flying mouse can soar for up to 28m. These aerial acrobatics help the tiny creature avoid ground-dwelling predators such as domestic cats, which pose a huge threat to Australian marsupials.

As voted by readers of Practical Fishkeeping magazine

Uses cultured insect meal to recreate the natural insect based diet that most fish eat in the wild.

Easily digested and processed by the fish resulting in less waste.

Environmentally friendly and sustainable.

For many years, the Fighting Fishes of the genus Betta have been poorly misunderstood. Even within aquarist circles, the Siamese Fighter (Betta splendens) remains synonymous with the genus.

By Max Pedley

By Max Pedley

Halfmoon betta (Betta splendens)

There are 73 distinct species of Betta, of which over half are classified from near threatened through to extinct by the IUCN red list and may well disappear before many even get chance to learn about, let alone see. These other species of fighting fishes are often collectively referred to as wild-types or simply, wild Betta.

As the name suggests, the Siamese Fighter is found in Thailand. Siam being the old name for the country. Reports from the Malay peninsula, Vietnam and Cambodia all refer to naturalised populations of domestic animals. These were released through negligence or as a lucrative venture for the Ornamental Aquatic Trade or the even crueller Fighting Fish traditions, where they are known often as Plakad, meaning ‘fighting’ or ‘biting’ fish. Such traditions started over 150 years ago and swelled with popularity. In fact, the popularity of such “sport” reached a level that the King of Siam decided it should be taxed and regulated.

There is difficulty in calculating how this feralisation encroaches on the ecology of endemic species, but as we have witnessed many times before, it is best to not have to find out. Unfortunately, released Swordtails (Xiphophorus spp.) and other household tropical fish names have already established alien

populations throughout South East Asia, impacting native flora and fauna. Large Tilapia cichlids (Oreochromis spp.) originally introduced as a food fish, muscle out native competitors and become predators of smaller fish and amphibians.

The wider genus is spread throughout SouthEast Asian countries, with strongholds of interest including Indonesia and Singapore. Unfortunately, collection for the trade, habitat degradation and other, all too familiar forms of exploitation threaten the extancy of a remarkably diverse group of fish. As humans move further into natural areas, urbanisation and pollution account for a dramatic decrease in populations of not just fish, but other animals too. In Java, the Near Threatened Decorated Fighting Fish (Betta picta) shares territories with the newly discovered but severely threatened Trilaksono bush frog (Chirixalus trilaksonoi). Umbrella conservation would certainly help both species.

It is easy to believe that the flowing finned, pouty fish, which humans have created for their own pleasure are out and out aggressive. After all, we call them Fighting Fish! In reality, evolution’s careful hand has crafted a devilishly diverse genus, stretching far from the stereotypes. Pinpointed, survival orientated forms seem alien to those who have only observed the Siamese fighter.

Peaceful, amicable behaviour features heavily too, making the common name obsolete. In nature, ‘fighting’ is limited to opercular (Another name given to the gill covers/cheeks of fish) flaring and other testosterone provoked routines, often including dance like movements.

Because the wild types are peaceful, well researched tankmates can be included for many species, but beware. Larger fish such as the Tiger Betta (Betta patoti) are predators with huge mouths and will actively hunt other fish and live food such as hoppers and large crickets, even jumping clean of the water to catch their target.

Surely, you can do Betta?

The Betta coccina complex species’ are more often known as the Wine Red Betta, no doubt due to the deep red colouration many members of the group display. The coccina group could even be considered amphibious, out of necessity rather than choice. For a few short months of the year during the dry season, these fish survive in essentially wet leaves. The shallow pools they inhabit have a very low pH due to the tannin and humic acid released by rotting leaf litter. Oxygen content is also low as the water is stagnant. Luckily, all Fighting Fish have a specially developed organ known as the labyrinth organ to help them breath atmospheric air.

One Spot Fighting Fish, Betta unimaculata and closely related species are giants of the group, with males often reaching lengths of up to 5”. Members of the group inhabit faster flowing streams of Borneo, to which they are endemic. The One Spot Fighters make arguably

the best pet fish of the genus as they seem incredibly clever, even recognising owners and interacting with them during feeding times. These are the predators of the group and relish a diet heavy with live foods such as small crickets, mealworms and bloodworm.

Betta splendens

Wine red betta (Betta coccina)

Betta splendens

Wine red betta (Betta coccina)

The reproductive strategies of Fighting Fishes can be split into two; Mouthbrooders and Bubblenesters. Interestingly, parental care is virtually always carried out by the male fish.

Mouthbrooders hold eggs within the mouth for up to 3 weeks, sometimes feeding on unfertilised eggs to fuel him through such a paternal mission. Other than these eggs, the male will not feed on anything else during incubation. Mouthbrooders, much like viviparous reptiles, produce low numbers of highly developed young. Such a method of reproduction is useful in fast flowing water, where neonatal larvae may struggle to fight strong currents. In total, approximately 55 species employ this technique.

Bubblenesters, on the other hand produce floating rafts of bubbles in which the eggs are sheltered. These nests help to keep the eggs protected in on place. Because such nests are exposed to heavy rainfall and disruption from other environmental activity, the eggs must hatch quickly and fry become

independent soon after. Therefore, the fry are very small and numerous, as it is likely many will become prey as soon as they leave the protection of their father. Roughly 18 species are bubblenesters.

There is a Betta for everyone. Contrary to any information regarding the ‘wild side’, not all species are obligate acidophiles or blackwater fish. By this I mean species which require acidic water to thrive. For instance, black sheep of the genus, and B.

Simple and Mahachai Betta respectively) both thrive when kept in hard alkaline water, though to keep the Snakehead and White Seam Betta, soft or RO * water would be advantageous.

As such, no hard or fast rules can be given which dictate the successful husbandry of Betta spp. If you want to start out, opt for a member of the stereotypical splendens group. The Peaceful Betta (B. imbellis) offers a highly showy, attractive fish that will adapt to a wide range of parameters, including slightly acidic to slightly alkaline. Filter with gentle, air powered sponge filters, plant the tank heavily and provide plenty of hiding spaces and you can’t go wrong. For those keepers who prefer less-gaudy specimens, plenty of ‘Ditch’ Betta are available. These are species which are incredibly hardy, often mouthbrooding animals adapt at conquering even the worst of conditions. Such fish are seldom endangered, because even pollution does not seem to have negative effects.

For the experienced aquarist, the coveted Brunei Beauty (Betta macrosotoma) may be your quarry. A truly tricky fish to keep, low pH is necessary for long term success. Unusually for acidophilic species, a moderate conductivity seems beneficial. This can be achieved with Himalayan pink salt, of all things! A low resistance to parasites and bacteria comes with the fish, meaning you must be either brave, rich or confident to fathom spending triple figures for a pair. If you can find them, that is…

The needs of Fighting Fishes are so varied that there is no single answer to this question and the size of the tank itself depends on the species you wish to keep. For a hardcore fish breeder looking to maximise a yield of youngsters, a species only tank

will be necessary. Breeders will often use pieces of floating polystyrene, cork and even live floating plants on which bubblenesters can anchor their nest. Nylon ‘mops’ provide refuge for newly hatched or in the case of mouthbrooders, released fry.

Other, more casual keepers might opt to keep their fish in a community tank. Provided tankmates are suitable, many setups will work well. It is however worth noting that many Betta spp. are accomplished jumpers, so any prospective tanks require a tightfitting lid.

More recently, many keepers are joining the biotope movement. This is essentially the aquarium equivalent of the Bio-active setup. A Biotope aims to recreate a slice of nature, using hardscape and décor which the fish would naturally be found in and around. Dried leaf litter from oak, beech and sweet chestnut works well, with the added benefit of the organic ‘tea’ released into the water as they decompose. In some instances, a biotope could even be worked into a paludarium, creating a display with both aquatic and land or backwall area for interest at all levels.

Title

Betta spp. lend themselves well to a mixed species paludarium. Due to the ability to breathe air and small overall size, certain species such as the Sword Betta (Betta falx) and Brown’s Betta (Betta brownorum), smaller bodies with little to no filtration can be utilised well. In such paludarium setups, water quality should still be monitored regularly via the use of a proprietary test

kit and water changes carried out when necessary.

Water should be at least 10l volume as a minimum for the smaller species, though depth is of little importance, opening the possibilities of including terrestrial amphibians such as dart frogs. Unfortunately, most Betta will predate on young tadpoles. Fighting Fish will also help to keep your water features clear of live food too, as they polish off small items such as Fruit Flies with gusto.

• Betta brownorumBrown’s Betta

• Betta Hendra –Hendra’s Betta

• Betta falx –Sword Betta

• Betta channoides –Snakehead Betta

• Betta mahachaiensis –Mahachai Betta

Big cats, megafauna and cute animals never struggle for support. Big round eyes, a healthy serving

of anthropomorphisation and bright colours sell them all day long. Without such assets, subtly coloured Betta go unnoticed. Less important species some might say. They simply don’t get the help they deserve, or frankly need!

Luckily, some zoos and conservation groups have recognised the dire situation of the genus and have begun to work towards increasing awareness. Captive breeding projects make up a significant proportion of such work but as with any animals, if the cause of population decrease is not solved, reintroduction schemes are completely in vain. Zoos can increase education too, through displays. As discussed, well thought out themes allow Fighters to cohabit with a plethora of more typical zoo

animals, provided conditions are met. It’s a surprise we don’t see them displayed more often, perhaps we should look to how Umbrella species can benefit them.

For more information visit: Anabantoid Association of Great Britain - Official Website (aagb.org)

Working together to conserve freshwater species - Shoal (shoalconservation.org)

*Soft water is water which contains few minerals and is typical of the water often found in rainforest and jungle areas. In the UK, much of the North is softwater, whilst the South is typically hardwater, though exceptions do occur. Reverse Osmosis water has been pushed through a filter which removes almost all minerals.

It isn’t only our captive royal pythons who are treated so dearly. In southeastern Nigeria, the Igbo people revere royal pythons as symbols of the earth and will even build small coffins to hold short funerals for any python that is accidentally killed.

small

As of 2017, over 6,500 different colour morphs of royal pythons have been recorded. Some mutations originated from the wild and have been brought into captivity, whilst the majority of morphs are a result of outcrossing these morphs together, causing a plethora of possibilities. Some morphs, especially one-of-a-kind mutations have fetched many tens of thousands of pounds among commercial breeders.

With over 50 years of service to reef aquariums, it is the pleasure of AQUARIUM S YSTEMS t o share the level of passion we have had since the beginning: L’AQUARIUM 2.0.

With L’AQUARIUM, you can start a reef system quite simply and w ithout any stress regardless of your l evel of expertise. Let us guide you, and welcome to the world of L’AQUARIUM 2.0.

HIGH QUALITY HAUTE QUALITÉ SHINYBLACK CABINE T

ADJUSTABLEFEET

Arachnids, and more specifically spiders, have always held a special place in society. The word ‘arachnophobia’ is certainly one of the more recognisable phobias. However, with the consistent rise in popularity of invertebrate keeping, attitudes are beginning to change. We explore some of the most prolific and interesting arachnida species available in the UK today.

There are no dangerous spiders in the UK, in fact there are only two that could be considered to give a ‘painful’ bite (Steotoda spp. Drysdera crocata Therefore, it is no wonder that a study in 1991 found that most cases of arachnophobia relate to no previous trauma whatsoever. Subsequent studies bounce ideas between environmental factors and a defence mechanism passed on from ancestors.

With consistent demonisation from mainstream media, the vibrant spiderkeeping hobby that exists today owes much of its success to the maverick importers of the 80s. Since tarantulas became a staple species for zoos and educational facilities, national consensus began to change. In fact, several tarantula species are very docile. Their safe-toobserve behaviours gave new generations the opportunity to experience the true nature of these remarkable animals.

Of course, the already converted experts can get a lot of joy from keeping spiders that are less safe, but truly awesome. Whether it is their huge size or obscure feeding habits, the traits which some fear, can often ignite a deep passion in those already enthralled arachnophiles.

MEXICAN RED KNEE TARANTULA (BRACHYPELMA SMITHI)

The Mexican red knee tarantulas (Brachypelma smithi and B. hamorii) are some of the most iconic species of tarantula, easily identifiable by their bright orange ‘knees’. Originally from the southern state of Guerrero and the pacific coast of Mexico

respectively, these species occupy a variety of habitats. Although most found in semi-arid scrublands, these species can occupy deserts and tropical deciduous forests too. Being ambush predators, adults will occupy burrows in rocky environments with substrate covered silk surrounding the entrance. Adults range in size from 12.7-14cm and have a famously docile temperament, contributing to their huge popularity in the pet trade.

Despite its hardy tolerance and popularity in the pet trade, B. hamorii is classed as vulnerable on the IUCN redlist. The increased demand for avocados, as well as lime, mango and melon farming has a significant role to play in

the demise of this species. New roads linking farmland to the international port of Manzanillo also cause significant mortalities during mating season.

they are typically very docile in nature making them a brilliant educational resource and first pet spider.

As the name suggests, these arachnids are from South America ranging from Chile to Argentina. A huge number of these were imported from the region in the 1980s, but since a ban was placed on exporting wildlife from Chile, this species has become much less readily available. Two colour phases of this spider exist, one exhibits a pink carapace, while the other has red hairs across its entire body, contributing to the coining of its common name.

Both the Chilean Rose and the Mexican red knee require relatively basic care. The Mexican red knee is a burrowing species, whereas Chilean rose’s are terrestrial and notorious tank re-decorators. A 30x30x30 terrarium would suit both but a larger enclosure would benefit the Chilean rose. Being desert species, they can both tolerate a broad temperature range. Between 24°C and 27°C is ideal with a low humidity of 65-75%, never dropping below 55%. A comfortable environment for the keeper is likely to be comfortable for the spider, but a heat mat with thermostat can assist in this. A shallow water dish should be provided for both species and can assist in maintaining a suitable humidity.

Mating occurs at the female’s burrow. The male will weave a web where he deposits his (but deceivingly rough) process involves the male transferring the sperm into the female’s opisthosoma. Although never observed in the wild, captive females can kill their smaller male counterparts after mating.

sperm before a delicate

Praised by educational institutions the world over, the Chilean rose is the perfect introduction responsible for changing attitudes of arachnophobes everywhere. Although this species can get quite ‘moody’ if handled excessively,

to tarantulas and

The curly hair (Tliltocatl albopilosum) has earnt its title as the perfect beginner spider due to several reasons. Firstly, it’s the most readily available species in the UK, which also gives it the title of the most inexpensive species in the market. The curly hair typically exhibits a very docile nature, making them an accessible species for all invertebrate keepers.

The original curly hair described in 1980 had white setae (a term used to describe a tarantula’s hairs). However, almost all curly hairs in the trade today have golden hairs. This species was also previously referred to as Brachypelma albopilosum, belonging to the Brachypelma genus. However, since 2019, the genus has been broken down into Brachypelma and Tliltocatl due to morphological differences.

Most tarantulas from the Americas rely on ‘urticating hairs’ as a primary defence from predators. This involves releasing hairs from the abdomen into the air, irritating the eyes, nose and mouth of any nearby predators. This primary line of defence reduces the need for a spider to bite, thus making American tarantulas much more docile than their Asian cousins who rely on their toxic bites to protect them.

Although predominantly terrestrial, this species does enjoy burrowing to avoid the harsh central American heat. This species inhabits seasonal tropical forest environments where it can often be found close to permanent waterways. Because of this, good husbandry requires a little more effort than other species. Temperatures should be maintained between 25°C and 29°C during the daytime, with a relative humidity of 65-75% between January and April and 75-85% for the rest of the year.

The curly hair can reach leg spans of up to 15.5cm and exhibits many of the traits desirable in a pet tarantula. They are famously docile, active hunters and relatively easy to care for. The biggest mistake owners make with this species is to use dry substrate which does not meet the spider’s humidity requirements.

Those that have kept spiders for numerous years and searching to develop their collection know there is no shortage of truly awesome arachnids in the hobby. Many of these species should never be handled, enticing an audience that prefers to observe the arachnids for the remarkable predators they are. Care requirements at this stage require more precision and a greater understanding of the animal’s wild needs. Arboreal species are often quicker, making them better suited to an expert. Equally, the ‘old world’ genus’ of tarantulas that exhibit bright colouration and catch the eye of the arachnid enthusiast often have more potent venom, again, making them better suited to an expert.

The goliath bird eater (Theraphosa blondi) is the largest spider in the world by mass and body length. This giant from the Amazon was first described by French explorers in 1804 and inhabits swamp areas deep within the rainforest, fuelling its mysterious infamy. Despite the ominous name, T. blondi rarely feeds on birds and instead preys on invertebrates,

reptiles and small mammals. However, it is thought that the 18th Century explorers that discovered the species, witnessed this spider eating a hummingbird and this image was immortalised in Victorian paintings.

The goliath bird eater has fangs measuring an impressive 6.5cm. Needless to say, a bite from this species is likely to cause considerable pain. The urticating hairs this spider uses as a defence mechanism can also cause serious irritations. Being a relatively skittish and aggressive spider, this species should only be kept by experts who have no desire to handle the animal.

Due to the goliath’s size, a minimum terrarium size of 60 x 45 x 45 is required with thick layers of moist substrate to ensure high humidity levels. Goliath bird eaters also appear to benefit from a well decorated enclosure. A cork hide is crucial, but plants can often stimulate explorative activity. Unlike other arachnids that can get their water from prey items, goliaths require a shallow water dish in their enclosure.

Almost all tarantulas benefit from a varied diet in captivity. Goliaths should be fed on predominantly on crickets and locust but can also be fed the occasional pinkie mouse.

Goliath Bird Eater Tarantula (Theraphosa blondi)

Arachnida fever

Goliath Bird Eater Tarantula (Theraphosa blondi)

Arachnida fever

Stunningly vibrant, critically endangered and dangerously venomous, Poecilotheria metallica is arguably the most interesting tarantula species on the planet. Otherwise known as the Peacock spider, this Indian species was discovered in 1899 by Reginald Pocock.

The Gooty sapphire ornamental tarantula originates from Andhra Pradesh forest around 250km from Gooty. The specimen which coined the common name was found in a timber train yard and likely travelled the distance through human intervention. Because P. metallica lives in just a 100km radius in South central India, this species faces threats from deforestation, logging, illegal exports and military exercises.

Although breeding projects from enthusiasts within the hobby have been successful, the Gooty sapphire ornamental does not make a good pet. Their venom, although not lethal, can cause an excruciatingly painful bite which is considered ‘medically serious’.

In captivity, the Gooty sapphire should be treated as an arboreal species. In the wild, this species would typically inhabit tree trunks off the ground. Spiderlings

often display terrestrial behaviours such as burrowing but adequate height with a tall cork bark hide should be provided as they grow. A 30x30x45cm terrarium is the minimum size required by an adult female Gooty sapphire, but extra height is often appreciated. Temperatures should be kept between 25°C – 29°C and drop by 5°C at night, while humidity remains between 70% and 80%.

Belonging to the same family as the Gooty sapphire, Poecilotheria regalis shares many of the stunning traits that make these tarantulas so appealing. This arboreal tarantula displays similar patterns to the Gooty, in shades of black and white. The Indian Ornamental also has an underside of vibrant banana-yellow on the front legs.

Thankfully, this species is much more common than its sapphire cousin. Spread across much larger pockets of central and West India, the IUCN has classified P. regalis as ‘least concern’ suggesting there is no need for dedicated conservation efforts at present. However, recent scientific research into the Yerramalais Forest of the Eastern Ghats suggests that human interference is depleting the natural resources in this region for many species (Khaleel Basha et al 2014) which creates a much bleaker picture for the Poecilotheria genus.

In captivity, caring for P. regalis is very similar to caring for P. metallica as they inhabit the same tropical forests. However, the Indian ornamental is slightly hardier and can easily tolerate humidity up to 95% for some months. Like the Gooty, the Indian Ornamental is typically unproblematic when breeding, making it a readily available species within the industry.

There is a paradox in arachnophobia that omits a huge portion of the Arachnida order. This order also contains scorpions, mites, ticks, harvestmen and solifugaes and ambilygpis. While the concept of a pet ‘tick’ might raise some serious concerns, some members of this group make wonderful pets. Solifugaes such as camel spiders, despite their terrifying appearance, are starting to appear within the hobby. While uropygids such as the tailless whip scorpion (Damon medius) have become a staple species in many pet shops, within a few years.

There are few hobbyists that would contest against the emperor scorpion (Pandinus imperator) being the ultimate pet scorpion. Impressively large, reasonably harmless and easy to care for, the emperor scorpion makes an ideal first invertebrate. Emperor scorpions are typically docile, but handling scorpions is advised against. Scorpions are more fragile than they appear, their sting is often likened to that of a bee and they can suffer from stress during handling.

These nocturnal predators hunt at night, using sensory hairs on their body to search for nearby prey. The emperor scorpion inhabits fallen trees and logs in the tropical rainforests of West Africa. This species competes with the giant forest scorpion (Heterometrus swammerdami) for the title of the world’s largest scorpion, with both averaging out around 20cm in length. The giant forest scorpion however, can reach a weight of 56g compared to the emperors 30g, solidifying the current title.

Emperor scorpions should be fed prey items 2 to 3 times a week. However, it is expected that the animal will lose their appetite some weeks before moulting. Emperor scorpions benefit from a temperature gradient in their enclosure from 25°C to 32°C with a drop at night.

Whilst still a common sight in zoos and invertebrate collections, a ban on exports and a reasonably limited number of breeding projects has made the emperor scorpion much less available in recent years. Consequently, this affects the price of these animals, which has increased exponentially over the last decade.

After their 15 minutes of fame in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, tail-less whip scorpions (Damon .spp) have exploded with popularity in the pet trade.

Tail-less whip scorpions are often referred to as whip spiders and belong to the order Amblypygi. However, whip scorpions are an entirely different order of arachnid. These are sometimes called vinegaroons and belong to the Uropygi order. The whip scorpion has a tail and visually, looks quite different to its tailless cousin. This confusing lexicon can easily create misinformation across the species.

Pedipalps are a second pair of appendages possessed by arachnids, as well as other chelicerates (a group of arthropods). They are located between the arachnids ‘jaw’ and first pair of walking legs. Pedipalps have a variety of purposes across all species that possess them. Emperor scorpions possess ‘claws’ for defence while tail-less whip scorpion’s use theirs for mating and feeding.

These species include D. medius, D. diadema and D. variegatus, which are all found across Africa.

Visually striking, these arachnids display an aesthetic that mirrors both spiders and scorpions, yet they can move sideways, much like a crab. Their pedipalps are used to grip onto prey items as they feed. The males have much larger pedipalps than the females. This sexual dimorphism is also more apparent in tail-less whip scorpions that live closer to the equator due to the differing lengths of the breeding season.

General care requirements follow a similar trend to most arachnids, with a 24°C-26°C day time temperature. Different species can require slightly cooler temperatures, but these are rarely available in the UK pet trade. Humidity should be kept at 80% but air flow is absolutely crucial to keeping a healthy tailless whip scorpion. Unlike many tarantulas, Damon spp. are fragile and susceptible to illness without strong ventilation.

This fragility also extends to their moulting habits. Hard stone backgrounds can wear the tailless whip scorpion’s claws down, causing them to fall to the enclosure floor during moulting. As Damon .spp rarely venture onto substrate, a 2” layer of chemical free compost, coir and spaghnum most is sufficient to hold moisture.

I consider myself lucky to say that I have visited the island of Madagascar twice. Having spent a total of 12 weeks in the North West taking part in Operation Wallacea, gaining a greater understanding of Uroplatus, the leaf-tailed geckos.

Leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus henkeli)

Leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus henkeli)

Operation Wallacea helps students conduct research for university projects around the world. Anyone can join expeditions as research assistants to help with the collection of field data. This helps support conservation efforts and contribute to responsible ecotourism. Seeing the sights of regions such as Nosy Be, Andasibe or Ankarafantsika is a life changing opportunity.

Madagascar is subject to a biodiversity crisis; with as much as 90% of the original forest cover of the island already lost. Clearance for agricultural land is the biggest driving factor, driven by population growth. The primary type of agriculture that takes place in rural Madagascar is known as tavy, a slashand-burn process which is extremally destructive for any animals and native plants that live there. These burning cycles take place to increase soil quality to produce higher yield crops.

Moreover, forests are burned to make charcoal, which is sold by locals, and space must be made for cattle. Animals – herpetofauna especially – are still collected and exported for the pet trade, despite a crackdown in 2019. What were once dense forests have since become extremely fragmented in most regions, which poses problems for remaining populations of native animals which become isolated or simply cannot thrive due to the loss of ideal habitat. ‘Edge effects’ around fragmented forest patches change the microclimate, which for ectothermic reptiles and amphibians can have a huge impact. Where environmental conditions are concerned, global warming also brings about harsher dry seasons and more frequent and destructive cyclones, impacting animals and people alike each year.

I managed to win an entrance scholarship award when I began university, and this ultimately funded a lot of the trip and made it possible. In my first trip back in 2018 I had chosen to work on the niche sharing between three species of Uroplatus, also known as the leaf tailed gecko that are endemic to

the North West of Madagascar. These cryptic geckos are truly special reptiles with a unique appearance. The three species in the area that formed part of my studies were U. ebenaui, U. guentheri, and U. henkeli. It goes without saying that I saw a plethora of other amazing animals as well, from all taxa. I slept in tents and hammocks beneath lemurs, saw Nile crocodiles while out on a boat alongside mangroves and saw a critically endangered fish eagle on my final day. An estimated one hundred breeding pairs of these birds remain in the wild.

Surveys for the leaf-tailed geckos were taken at night. Being nocturnal animals, It is rare to find these masters of camouflage during the day – although my first U. henkeli was brought into camp by the botanical team who accidentally knocked one out of a tree in the middle of the day.

I saw my first Günther’s leaf tailed gecko during the first night at the base camp survey site – on a fence just outside of camp, of all places. Upon finding an individual for the survey, I measured the temperature of the gecko’s skin and that of its perch, as well as the humidity in the area. The gecko would be caught – sometimes peacefully and sometimes with a lot of biting – and put in a cloth bag to take back to camp. The precise location it was taken from was flagged with marking tape and the GPS coordinates were recorded for mapping and environmental measurements.

Morphometric (body dimension) measurements were taken the next day in camp. I wanted to look closely at the length of the forearms in relation to the characteristics of the trees or other types of structures the geckos were

found on during surveys, to see if there was a relationship between the two factors.

Of the 33 leaf-tails i recorded, only 2 were U.henkeli. These large geckos were definitely the most elusive. At night they spend time perched in a pose similar to a horseshoe shape; ready to leap from tree to tree or onto any invertebrate prey. They have particularly long hindlegs which do a good job propelling them when they leap, and double toe pads to make the landing.

They stay hidden in the day by using their fringed skin to break up their outline and can even adjust the light and dark contrast of their skin colour using a similar mechanism to chameleons. I saw a juvenile U. henkeli during a night

survey on my second trip which has to be up there in my favourite herpetological experiences. I thought it was a U. guentheri until I picked it up. Seeing a young gecko (which to my delight looks like a baby dragon) is extra special due to the hope it brings - suggesting U. henkeli in the area are still reproducing at some rate.

Ultimately, 33 individuals is a small sample size when it comes to statistics. Sadly, the sites are only accessible in the dry season due to weather conditions and summer holiday schedules. Herpetofauna surveys are often dozens of times more bountiful in the wet season. The niche modelling suggested sensitivity of all three species to edge effects (distance from the edge of a forest), leaf area index (canopy density) and nearby anthropogenic structures (roads and villages).

Henkel’s leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus henkeli)

In the field with Aimee Jones

Henkel’s leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus henkeli)

In the field with Aimee Jones

Habitat suitability modelling used in my study showed few areas that would be able to support all three species within the same larger environment. This is an important consideration for conservation. By collaborating with Operation Wallacea, the local people can help to protect the remaining forest fragments for the benefit of both themselves and the animals that live there.

In my experience, I can say that U. ebenaui were found most often in bushes closer to the ground –these bushes had skinny twig branches and leaves of a similar shape to the body shape of small Uroplatus species. U. guentheri, being the middle size of the three, seemed to overlap by ranging from the ground, all the way to unreachable heights

in the canopy. It’s difficult to make generalisations for U. henkeli, but the ones I personally saw were found on the thicker trunks, which makes sense to accommodate their size, method of camouflage and jumping capabilities.

Uroplatus are well established in the pet trade. I always see this as a double-edged sword. Illegal trafficking and habitat destruction pose a threat, but in the right hands, captive populations preserve them while habitats are fragile.

Experienced keepers in the hobby already have the husbandry for Uroplatus well laid out, with many

In the field with Aimee Jonessuccessful breeders producing healthy leaf-tails year after year. If I were to make any suggestions for the species I worked on, it would be to provide dense foliage areas, particularly for the smaller U. ebenaui. It would be sensible to assume that plenty of opportunities to hide will help them to feel more comfortable in their environment. For the larger U. henkeli, a surface to accommodate the torsoflattening would be good. Cork bark, I imagine, is a great way to provide this. These animals are also fairly active nocturnally, so branches to climb over and hunt their food should prove to be stimulating. The forest floor in situ was most often a sandy soil with a generous layer of leaf litter on top. As is now recommended for all reptiles and amphibians, don’t skip the UVB. Uroplatus are known to rest in the

daytime in partially sunny patches or even direct sunlight for short periods. Ferguson Zone 1 lighting is the current recommendation.

I really could fawn over these fantastic geckos all day – they’ve stuck to a special place in my heart. I feel lucky every time I reminisce about both of my trips. It is bittersweet to wonder about their continued survival in their natural habitats, which is where captive populations are a blessing. I can’t deny that I would love to keep some myself. Two new Uroplatus species were officially described just recently –U. fivehy and U. fangorn, bringing the new total to 21 species.

In the field with Aimee Jones

In the field with Aimee Jones

For many experts across a range of fields in the exotic pet industry, breaking away from old ideas is extremely difficult. Much like a more conventional craft, perfecting great husbandry takes years of dedication and experience. However, breakthroughs in sciences such as zoology and nutrition, as well as product development can open many more avenues to perfect that craft further. Rethinking and re-evaluating approaches to each aspect of animal care is fundamental to staying at the top of the game.

Rebecca Taylor has an impressive reputation in the aviculture industry. As well as breeding thousands of birds from dozens of species since the 1980s, Becks Bird Barn has been praised by hobbyists for decades. She judged countless bird shows, pioneered the use of Java branches and provided vital research to the West Palm Beach Vets Conference. Despite this wealth of achievements, Becks considers learning and re-evaluating approaches to exotic pet care to be fundamental to success.

Rebecca recited an interesting anecdote to Exotics Keeper Magazine. She said: “We had two pairs of green wing macaws come into us. The owner was an experienced keeper and had kept both pairs with the intention of breeding them. He had told us that neither pair had shown any sign of successful mating in the many years he had owned them, but he did not want to break them up as macaws famously mate for life.”

“He had also mentioned that their aviaries were side by side. This one particular day, we had our vet on site as I explained about these two green winged macaws. I had decided to let them into one of our large flights to observe what might happen. The second we let them into the flight, the pairs swapped partners immediately. They had been kept in separate aviaries side by side from each other with a different partner for years. Our vet stood within the flight with his jaw wide open. Pedro, one of the males, began feeding the other female

almost immediately after being released into the flight. We ended up raising so many chicks from that pair. The point here is that there is always something that can change to maximise animal welfare. A lot of breeding pairs aren’t incompatible, they just require their keeper to change something very small within their environment.”

Exotics keepers can suffer from the same ‘tunnel vision’ as artists and therefore it is important to regularly re-evaluate every aspect of animal care from top to bottom. Even adjusting the heights and diameters of perches for parrots and arboreal snakes or relocating the food or water dish can result in significant changes in animal behaviour.

Rebecca continued: “Back in the 80s we were doing lots of ground-breaking stuff, because a lot of things were new. Even just being a woman in the industry seemed to take a lot of people by surprise. Knowing that we would be in this for the long term gave us more room to experiment and make mistakes. It also gave us the opportunity to adjust things, refine how we worked, observe the birds and get things right.”

“I think this comes from the stockmanship of owning a farm. If something is wrong, it is your responsibility to notice it and fix it. Well, it’s the same with exotics, constantly adapting and revaluating your approach can lead to happier, healthier animals.”

For novices trying to create the ideal set up for their first reptile, or expert breeders perfecting the seasons of an obscure pacific island, an openminded approach is a valuable tool. Hobbyists on all levels are often just one minor adjustment from a major breakthrough.

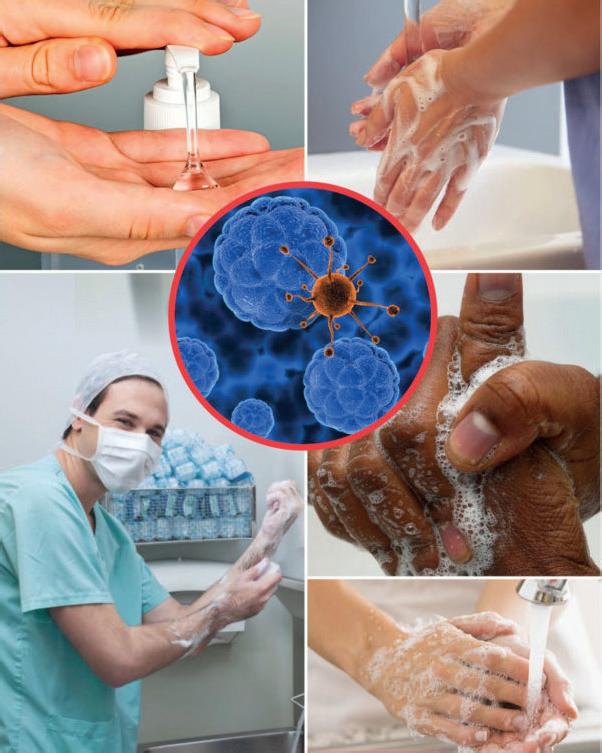

F10 hand decontaminants are proven highly effective, yet kind on skin. With broad spectrum efficiency the range will meet your needs with medical-grade soap, hand gel and alcohol-free sanitising.

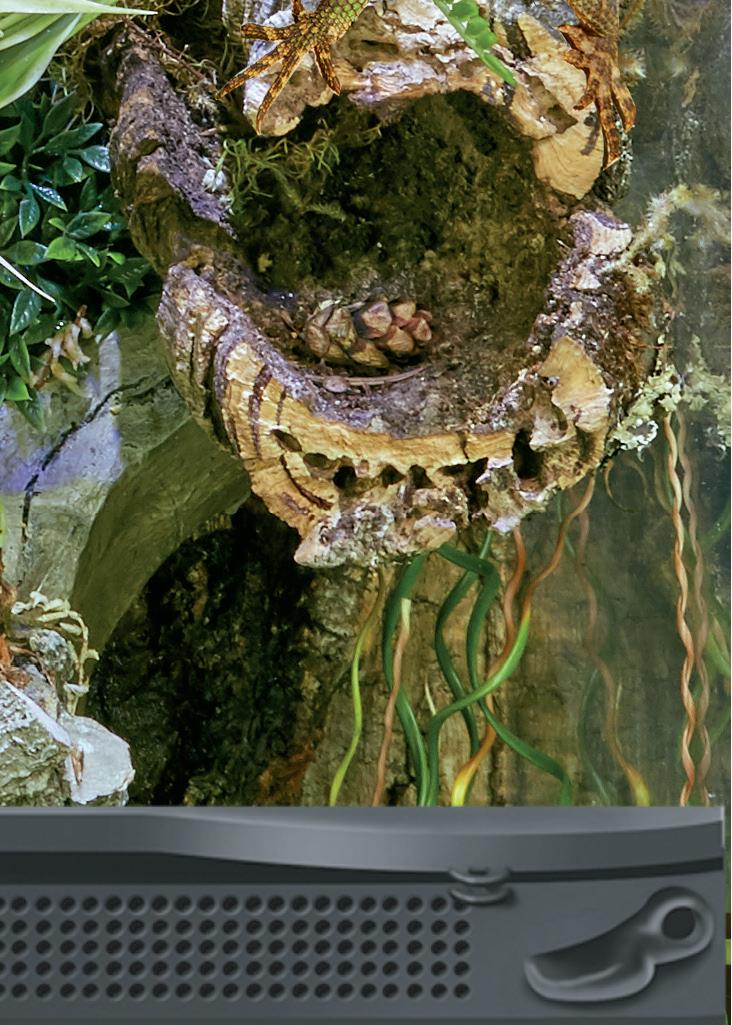

Zoo Med’s innovative Paludarium has 3 sections: a canopy, a land area and an aquarium. Each can be home to a variety of different plants and animals limited only by your imagination.

Available in 3 convenient sizes:

12”L x 12”W x 24”H (4 gallons of water)

18”L x 18”W x 36”H (10 gallons of water)

36”L x 18”W x 36”H (20 gallons of water)

Build a Terrarium, build an Aquarium, build your own piece of nature and tranquility.

To find out where to get Zoo Med’s NEW Paludarium and other fine Zoo Med products, please visit our website.