In this month... up close with crocodiles, the lowdown on livefood, adorable sugar gliders and much more.

In this month... up close with crocodiles, the lowdown on livefood, adorable sugar gliders and much more.

Moving swiftly on from the challenges of 2020, there are at least a few promising signs which indicate that 2021 could be a vastly more enjoyable year — at least for the millions of new pet owners out there.

Statistics from across the board have shown a sharp uptake in the number of people acquiring new pets, whether they be the conventional furry friends, such as cats and dogs, or those of the exotic variety which frequent the pages of this magazine. If you’re one of them, here’s wishing you many joyous and fun-filled years of companionship with your new pet.

On a similar note, I was staggered to read The Federation of British Herpetologists report, estimating that there are likely at least as many reptiles being kept as pets in the UK as there are dogs! However, despite their popularity, it’s pleasing to know that comparatively few reptiles and amphibians end up in need of rescue or rehoming. Our tailend feature with Chris Newman from the National Centre for Reptile Welfare explores the work they do in this field.

EK expert Jim Collins talks us through why sugar gliders are so popular, despite being a bit stinky sometimes, and Colin Stevenson from Crocodiles of the World introduces us to a few of the rather less cuddly animals he works with.

Plus, there’s an informative look at feeder insects, with enough top-level information to make you a livefood master. Dig in and enjoy!

02 06 18 19

02 EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

06 UP CLOSE WITH CROCODILES

Croc expert Colin Stevenson gives us an insight into working with these incredible animals.

18 ANIMAL FACTS

Did you know...?

19

32 34

LIVEFOOD LOWDOWN

Crickets, locusts, cockroaches or bean weevils? We give you everything you need to know to make the right choices.

32

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets.

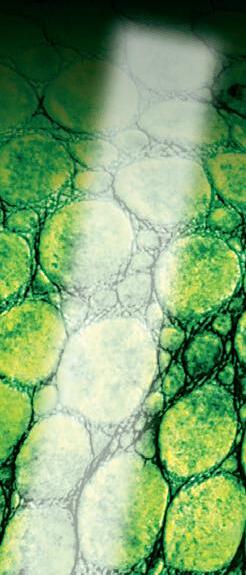

This month it’s the rough green snake (Opheodrys aestivus).

34

THE ADORABLE SUGAR GLIDER

What’s not to love about these fascinating marsupials? Exotics expert Jim Collins reveals some surprises about sugar gliders’ not-so-cute habits.

45

ASK AN EXPERT

Got a query? Ask our resident panel of nerds for advice.

46 THE TAIL END

Chris Newman from the National Centre for Reptile Welfare discusses the truth about reptile rescue and rehoming.

A group of 16 MPs and Peers have written to the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, urging him to release financial support earmarked to help zoos which were closed due to the Covid-19 lockdowns. The 100 million pound fund has been largely unclaimed due to design flaws in the fund’s eligibility requirements.

One of the letter’s signatories, Dr Luke Evans, the Member of Parliament for Bosworth, said: “To claim financial support from the Government zoos have to be at imminent risk of going under. The Government’s £100 million Zoo Animals Fund is well-meaning but has stood largely untouched because thankfully many have not got to the point of planning for closure yet, only 5 out of 300 zoos, aquariums and safari parks have been able to claim.

Part of the letter reads:

Sadly, the Zoo Animals Fund has failed to adequately meet the challenges of the pandemic and we are subsequently witnessing a dire impact on the zoo sector and their important conservation work. This failure puts the very survival of the wildlife dependent on the sector at risk. Government support for zoos cannot disappear midway through this pandemic.

The Zoo Animals Fund must be urgently replaced. At the time of writing, only five zoos had successfully been approved for grants, despite the huge need for help across hundreds of organisations. This means the vast majority of the £100 million provided by Government for the Fund is unspent!

We urge your Government to take the simple step of ringfencing all the remaining funds and to work with the sector to implement new schemes that will meaningfully support all zoos, aquariums and safari parks until we win our fight against the coronavirus.

An albino Indian rock python (Python molurus ‘pimbura’) was captured in Sri Lanka, only to be released back into the wild by authorities. This is the first known instance of an albino specimen of this species being recorded.

Dr Tharaka Prasad, Director of Health, Department of Wildlife said, “Initially, we had plans of handing it over to the National Zoo, but we changed our mind when the National Zoo refused to take the reptile, and there was no point in keeping it with the DWC. So, it was decided that it should be released into the best possible environment where it would not be at further risk.”

Unfortunately, albino mutations rarely survive in the wild. Many believe a more sensible response would have been to sell the animal to be bred, thereby protecting the individual from harm in the wild and also providing funds for conservation in its country of origin.

English veterinarian Dr James Chatterton has been working to bring the world’s fattest parrot back from the brink of extinction, testing new treatments for a disease afflicting New Zealand’s kakapo.

The respiratory disease aspergillosis began to spread through the endangered kakapo population last April, wiping out large parts of the population of this flightless, nocturnal and somewhat portly parrot species. While aspergillosis can be treated with oral antifungal drugs, it only works if it is caught very early in its progress, and treated with a nebuliser to deliver the anti-fungal treatment directly to the birds’ lungs.

While some of the affected birds needed months of care, the outbreak was eventually contained. The number of kakapo now stands at 211, up from just 123 when Chatterton arrived in New Zealand seven years ago.

The owner of Norwich based exotic invertebrate breeding and import business BugzUK is reported to be planning on opening an invertebrate-specialist zoo. Owner Martin French has applied for a zoo licence for the venture which will feature exhibits where visitors can handle and learn about up to 40 different exotic invertebrate species.

Another new collection is also planned for Redditch. The Heart of England Wildlife Park is the brainchild of animal enthusiast Martin Blyth, and is planned to open by Easter 2021, featuring approximately 300 animals of 50 different species.

We’ll keep you posted as these projects progress.

Congratulations to Crocodiles of the World for their successful breeding of black tree monitors (Varanus beccarii).

This relatively small monitor species grows to about 90 – 120cm including tail, and hails from the tiny Aru Island off New Guinea. Hatchlings and juveniles are dark grey with bright yellow-green dots, turning completely black as they reach adulthood.

Websites | Social media | Published research

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page.

THIS MONTH IT’S REPTILE LIGHTING

Reptile Lighting is a Facebook group dedicated to the understanding, discussion and awareness of lighting for reptiles and amphibians in captivity – UV, general ambient lighting and heating. The group has almost 10K members and boasts a growing library of peer-reviewed videos.

www.facebook.com/groups/ReptileLighting

Very little is known about this animal’s reproduction in the wild and captive-breeding attempts have been only sporadically successful as embryos often die in the egg shortly before they are due to hatch.

The breeding success for this species at Crocodiles of the World is a significant boost for this enigmatic species.

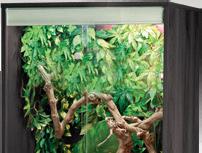

Vivexotic is renowned for its quality, great value and useful features and now the ever popular Repti Home range is available in a cool grey finish! Bored with oak? Does walnut clash with your decor? Match your viv to your living space with the new Repti Home grey range, available from good reptile stockists nationwide.

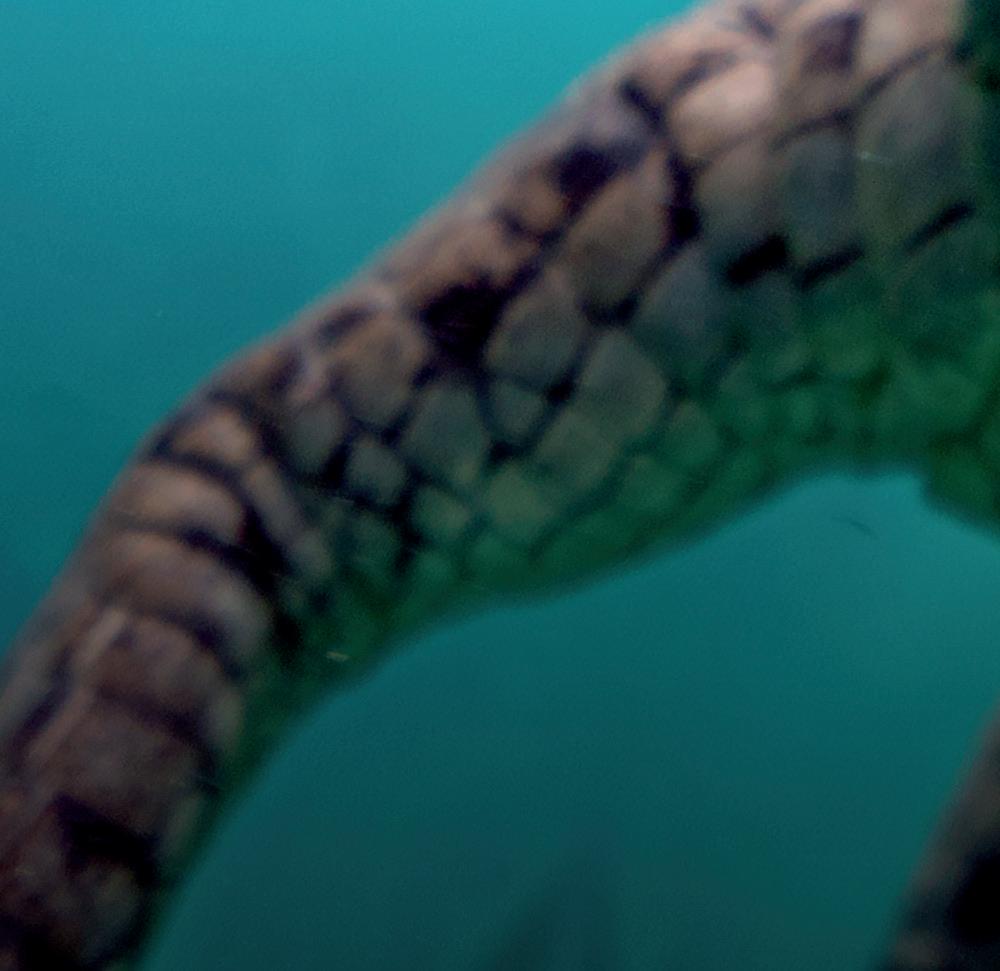

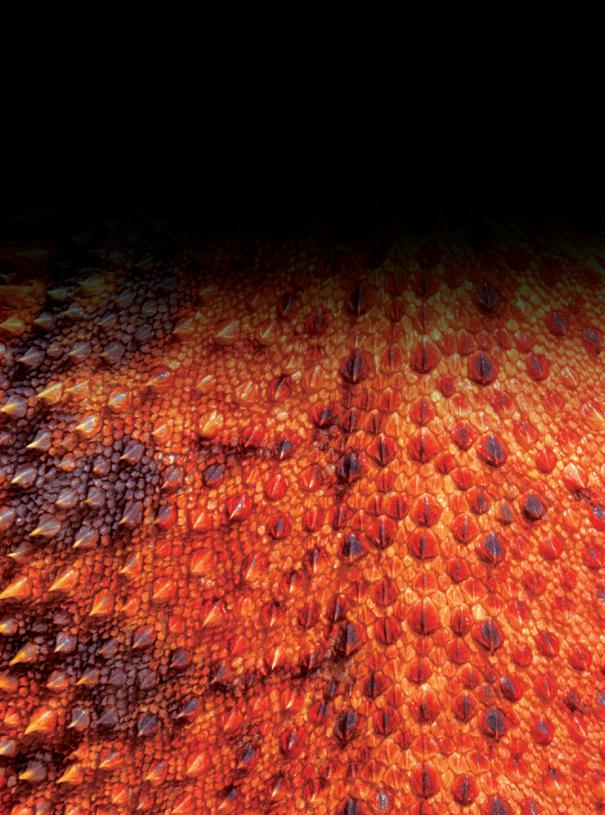

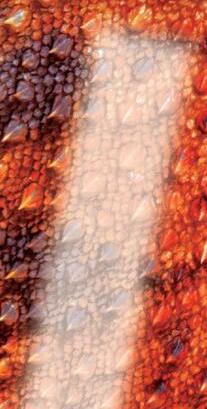

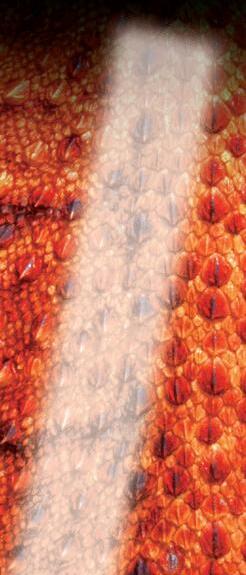

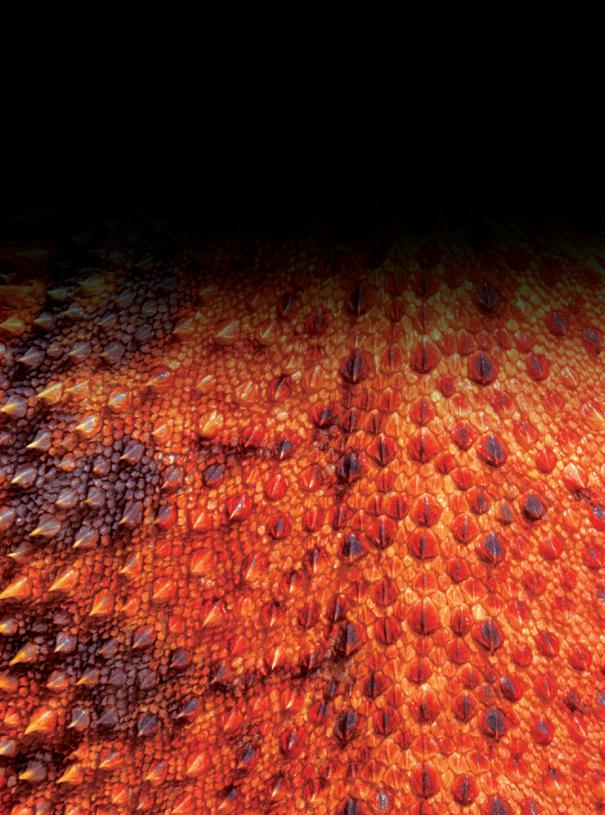

Despite being dangerous apex predators, many crocodiles exist perilously on the brink of extinction. Thankfully, a few dedicated zoos are working to safeguard these awesome creatures.

I grew up in Australia and have always had a fascination with crocs – I have no idea why. Really, I’d say my fascination was more of an obsession and, back then, it was considered a little odd. This was well before Steve Irwin, and even before there were any good TV shows about reptiles. Nowadays working with crocs is almost a mainstream career option, but back then, I was a bit unusual, to say the least.

Somehow I ended up working in IT until the late 1990s, but my fascination with crocs didn’t go away. I’d been involved with crocodile conservation and the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group and I soon realised this was far more fulfilling than working with computers.

By the early 2000s I had quit the day job and started my own company called ‘Crocodile Encounters’. I’d go into schools, armed with a few freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnsoni) and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus), delivering educational encounters to raise awareness of these animals. I also did a couple of zoo qualifications and set up a website dedicated to the dwarf caiman which, despite not being updated for almost 20 years, is still quite popular and relevant.

By this time I was building a reputation and becoming known in the zoo world. I did some consultation and advisory work with the Danish Krokodille Zoo and eventually opened my own zoo – the Hunter Valley Zoo in New South Wales. I had the Zoo for around three years and it was just about gaining enough traction to be successful before family commitments brought a move to Britain with my British wife. The zoo is still open and doing well today.

Once in Britain I soon accumulated a decent collection of crocs – nine species to be precise. I started ‘Crocodile Encounters UK’ doing similar work as I had been doing in Oz. It was an interesting enterprise, because the British Dangerous Wild Animals licence does not cater for the routine transportation of crocodilians, so I had to have a bespoke licence created specifically for my needs.

Around this time I was involved in the croc specialist group where I met Crocs of the World’s founder, Shaun Foggett. He was in the process of setting up his own croc zoo and I got involved to help out.

But, in 2011, I got the opportunity to work in my dream job as the Director of Madras Crocodile Bank with renowned reptile expert Romulus Whitaker. I was at Croc Bank for three years before coming back to the UK and picking up where I left off with Shaun at Crocs of the World. Since 2015 I have been Head of Education here at the zoo.

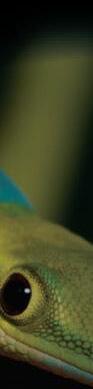

Anyone who loves animals will have dreamed of working in a zoo. But what if your passion is for crocodiles? Can you make a career out of it? Our visit to Crocodiles of the World to meet croc expert Colin Stevenson gave us all the information we need.Tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii) Credit: Crocodiles of the World

People think working with crocs is going to be exciting and dangerous. I have a great job and it’s lots of fun but, to be honest, I try to stay away from the drama and the hype. While it can sometimes be exciting, it’s not usually too dramatic, thankfully. A typical day in my job is fun because I get to do something I enjoy, not because it is full of dangerous adventures. Every day is pretty interesting and fulfilling, on the whole. Working with the public is a pleasure. People are really fascinated in crocs and it’s great to know that you’ve changed how they think about these animals.

There are a handful of interesting stories though. One of my most memorable experiences was during a visit to the St Augustine Alligator Farm in Florida. It’s essentially a zoo these days, rather than a farm, and I was there with several other croc specialists from different zoos, watching the keepers feed a tomistoma (Tomistoma schlegelii).

The keeper threw in a pig’s head, which was caught by a huge tomistoma who held onto it with its jaws for a few seconds. Then, it quickly closed its mouth and burst the pig’s head like a watermelon. It was an awesome sight, and all of the folk in the room went “OOOOOOOOHHHHH!”

That’s quite something, considering everyone in the room worked with crocs. Despite our extensive experience we were still very impressed.

Another time I was stopped by customs officers in France as I was about to board the ferry. They wanted to know what was in the boxes I had in the back of my van. I told them I was transporting 26 crocodiles of different species and sizes and asked them if they wanted to take a look. One replied “Nah, we’ll leave that for the English to do at their end. Off you go.”

The tomistoma used to be known as a false gharial, but this is something of a misnomer. Anyone who works with live tomistomas knows that it behaves more like a crocodile. The molecular DNA indicates that the tomistoma is related to the gharial and, if you squint, the narrow jaw is reminiscent of a gharial. But that’s where the similarities end. These animals behave like a crocodile, and if you treat them like a gharial, you’ll soon be dead.

They don’t just eat fish, which is what a lot of people expect from those jaws. In the wild they eat a whole range of things, including macaque monkeys. They’re an awesome creature.

The Natural History Museum in London has a tomistoma skull which is the largest crocodilian skull on record. It’s about 84cm from base to nose tip – that’s almost three feet long. Unfortunately you can only see it if you have contacts there as it’s not kept on display.

To be honest, croc-only zoos are not a new concept. There are crocspecific zoos all over the world, particularly in Australia, the USA and Africa, but there are several in Europe too. France has four croc zoos, there’s a good one in the Czech Republic and there’s also a great one in Denmark that is quite renowned. It’s a mystery why there wasn’t one in Britain sooner.

Shaun Foggett is the founder of Crocs of the World. The idea came about after Shaun was featured in a series of documentary films about him and the crocs he kept at home, by which point Shaun was becoming inclined to move his croc habit up to the next level.

The first Crocs of the World zoo opened in 2011. It was a small facility based in an industrial unit. But, by 2014, we’d moved to our current, bigger site which is far more suitable for a visitor attraction. We’re now a fully accredited BIAZA zoo and we’re growing and developing all the time.

When you boil it all down, the reason Crocs of the World exists is that everyone involved here loves crocs. But if you ask me for a more sophisticated reason I’ll say that specialist zoos like ours have an important role to play, because that’s where particular expertise can be found and developed. We can be very focussed, diving deep into the husbandry and conservation challenges of the specific taxa.

Our staff are a special breed of people! We don’t expect to recruit staff who already have croc-specialist experience. We tend to hire good, zoo-qualified people who have the right attitude and a particular interest in crocs, and then we train them to have the right skills.

You’ll not be surprised that we get a lot of Steve Irwin wannabes apply and we have to filter these applicants out. The work we do is nothing like what these people expect it will be, so it’s not worth hiring them. Most of the staff who work with our crocs have been with us for years as volunteers and trainees, and they’re a fantastic asset for a specialist zoo such as ours.

Big generic zoos are important too, of course, but if there’s something croc-specific happening it will usually end up at our door. There are seven critically endangered croc species in the world and we aim to be the go-to source for anything to do with these animals. It’s small baby steps at the moment, mainly due to resources, but that’s where we’re heading and we are making good progress.

A blended substrate to help create the ideal enviroment for Bearded Dragons and other desert species.

Crocodiles of the World reptile inventory

American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis

Chinese Alligator Alligator sinensis

Spectacled Caiman Caiman crocodilus

Yacare Caiman Caiman yacare

Broad-snouted

Caiman latirostris

Black Caiman Melanosuchus niger

Dwarf Caiman Paleosuchus palpebrosus

Smooth-fronted Caiman Paleosuchus trigonatus

Crocodiles

Nile Crocodile Crocodylus niloticus

Saltwater Crocodile Crocodylus porosus

Siamese Crocodile

Crocodylus siamensis

West-African Dwarf Crocodile Osteolaemus tetraspis

West-African Slender-snouted Crocodile

Mecistops cataphractus

Cuban Crocodile Crocodylus rhombifer

Morelet’s Crocodile Crocodylus moreletii

Philippine Crocodile Crocodylus mindorensis

West African Crocodile Crocodylus suchus

Tomistoma Tomistoma schlegelii

Australian Freshwater Crocodile Crocodylus johnstoni

Lizards

Komodo Dragon Varanus komodoensis

Lace Monitor Varanus varius

Crocodile Monitor Varanus salvadorii

Emerald or Green Tree Monitor Varanus prasinus

Black Tree Monitor Varanus beccarii

Ridge or Spiny-tailed Monitor Varanus acanthurus

Asian Water Monitor

Varanus salvator

Merten’s Water Monitor Varanus mertensi

Argentine Tegu Salvator merianae

Giant Day Gecko

Yellow-headed Day Gecko

Phelsuma grandis

Phelsuma klemmeri

Caiman Lizard Dracaena guianensis

Crocodile Skink

Snakes

Tribolonotus gracilis

Royal Python Python regius

Green Anaconda Eunectes murinus

Boa Constrictor

Boa constrictor

Reticulated Python (Malayo) Python reticulatus

Green Tree Python Morelia viridis

Chelonia

African Spurred Tortoise

Galapagos Tortoise

Red-foot tortoise

Centrochelys sulcata

Chelonoidis nigra

Chelonoidis carbonaria

Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys pardalis

Fly River Turtles

Amazon Giant River Turtle

Carettochelys insculpta

Podocnemis expansa

Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii

If we’re in an enclosure with a big specimen then there’s a very low tolerance for risk. At the slightest sniff of something looking a bit hairy we have a robust ‘run away quickly’ policy. We don’t take risks with anything which could be truly dangerous.

Yes, of course, I have been bitten by a crocodile, but thankfully only small ones. Everyone who works with animals has been bitten! The worst bite was, predictably, a Cuban Crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) – a particularly snappy species, which I was handling as part of a display. It wasn’t large, four feet long or so, but it was one of those days where I just wasn’t on my top game. My handling was a bit lame so the croc seized its chance and spun to get away. The croc’s tooth skimmed my thumb during the process and sliced it open.

Under different circumstances I would have just dropped the animal and the drama would have been over and done with, but with a dozen school kids around me, that wasn’t an option. So I just held onto it! This was one of those situations where I knew I wasn’t really in the mood – and the croc wasn’t in the mood either – so we should have just called it off. But I was in the mindset that the show must go on, and that’s how accidents happen. I ended up with a few stitches and a decent scar.

My worst bite ever was from a 35kg wombat I was measuring when I was in Australia. That little bugger bit me and left a chunk of flesh flapping on my forearm. It wasn’t very nice at all.

Before we breed anything we have to be sure that there’s a need for those babies and a purpose for the breeding. We have to work out what we want to breed, how many, and where they’re going to go if they do breed. For example, the only outlet for dwarf crocs (Osteolaemus tetraspis) is the pet trade, so that’s not really an option.

Similarly, we rarely breed Siamese crocs (Crocodylus siamensis) even though they’re critically endangered, simply because there’s nowhere for them to go if we do breed them. You can’t just send them back to the wild in Cambodia because there’s no habitat for them there. Breeding this species will make no difference to their endangered status.

There have been situations where zoos have bred critically endangered species and then, a few years later, the whole zoo community worldwide has to stop breeding them. There’s nowhere for the animals to go because zoos are overrun with them. It sounds crazy, and it is. That’s how endangered croc species, such as Philippine crocodiles (Crocodylus mindorensis), end up in the pet trade. Our entire breeding efforts are dictated by what we need and the needs of other zoos.

Thankfully the Natural History Museum is running a project that can make use of unhatched croc eggs. So if we get eggs from a species where there’s no outlet for the babies then the Museum is happy to take them off our hands.

Rebecca and Hugo are some of the stars of the show at Crocs of the World.

Siamese crocodiles are critically endangered in the wild, with their population decreasing. Thankfully, Rebecca and Hugo mate each year at Crocs of the World, with any hatchlings from their clutch going to other zoo collections around the world.

Getting the eggs to put them in the incubator can be fun! Siamese crocodiles are very protective.

There’s lots of debate about whether crocodiles, and particularly endangered species, should be sold to private keepers. There’s no black or white answer to that question as some people keep them well and some people keep them badly. Of course, I support those who do it well and I despise those who keep them badly.

People who get a croc for bravado and ego are often the ones who cause problems. On the other hand, I know plenty of private keepers who could, and would, happily work in a zoo if it paid well. Instead, they keep these animals privately and dedicate significant time, money and resources to their husbandry – often far more than can be done by any zoo.

These dedicated specialists can often know more than the generalist zookeeper. And, of course, there are crap zoos and crap zookeepers out there too. I’m certainly not against private croc-keeping in general. I’m against bad croc-keeping.

At the end of the day, crocs aren’t a sensible choice if you want a pet, but sensible and responsible private keeping is a different matter. It’s the same for people who keep venomous species or large snakes and lizard species, or any animal for that matter. If you’re sensible, we’re on your side.

Banning animals from private ownership has been a disaster everywhere it has been introduced. In Australia, a place with some of the strictest wildlife laws in the world, you can still get corn snakes and anacondas if you want them.

While buying from breeders isn’t a bad idea, few breeders are regulated, licensed or inspected – unlike pet shops. In reality, many shops will sell you a reptile five minutes after the store closes in the car park. It’s crazy to make selling reptiles so difficult as it sends the trade underground. You can’t get expert help or vet treatment for an animal you’re not supposed to have. At least if the trade is legal and regulated the authorities can monitor and understand what’s going on, and the keepers and animals can have access to the resources, advice and treatments they need.

Banning people from keeping crocs, or indeed any animal would be a bad idea. People should be allowed to keep any animal as long as the regulations enforce good husbandry and welfare.

Well. The first task is to decide whether you do actually need to move or handle the animal and, if you don’t, then don’t do it. If you do need to move it, then there are several ways to go about it.

Anything under 4ft is a quick job for someone with the necessary experience – you just jump on and pick it up. That said, you do still have to be careful. Any croc approaching 2ft is going to give you an unpleasant bite. And you really don’t want to be bitten by anything approaching 3ft. A fourfooter isn’t going to tear bits off, but it’ll be a messy affair and it will cause you some real problems if something that size bites you. Anything bigger than 4ft doesn’t bear thinking about.

If you’re handling a croc under 4ft you can throw a towel over their head to stop them from seeing you approaching. Then you grab it behind the head and hang on for dear life. It’s not too bad grabbing small crocs, compared to a similar-sized monitor that can scratch or tail-whip you.

Anything over 5ft is a similar process, but you will need two people. One must somehow attach a rope to pull the croc out of the water. It will thrash and spin, but that’s fine as long as there’s nothing nearby they can hurt themselves on. Once they’ve tired themselves out the other person jumps on. It’s the same process, throwing a towel over the croc’s eyes and then quickly jumping on to hold it. It can look quite crazy and disorganised, but it’s the best way. Crocs get tired out quickly from the buildup of lactic acid. Any croc measuring 6ft or so it will need two people to jump on. Crocs that big are strong enough to throw off the weight of just one person.

Bigger animals can’t be held by people. The risks are too great in most circumstances, so we use a couple of different methods for the sake of safety. The first involves training. By using small pieces of food as a reward (often a mouse is sufficient) crocs can be persuaded to enter a transportation crate. Training needs to occur regularly to get consistent results and be ready as an option when the process is necessary. We train 5 – 10 minute sessions at least four times per week, and if we don’t get the desired behaviour, the animal does not get the food. Of course, you need to have the training in place well before the need to move them arises.

Another way, if your croc is not crate trained, is to use a large, porous agricultural pipe, and you’ll need a few people on hand to do it. First, you’ll need to empty most of the water from the animal’s enclosure. Then, slide the big pipe until it is almost touching the tip of the croc’s jaws. Then someone must, very gently, lift the jaw using a long wooden pole, so that the pipe can slide underneath. Once the entire head is in the mouth of the pipe, another person can gently poke the croc’s tail, which will cause them to lurch forward into the tube. A few more nudges and you’ll have a tube full of croc and it’s time to seal up the end. Because the tubes have holes in, any water will run out when you lift it up. We recently used this method with our 160kg tomistoma when we were moving it from one side of the Zoo to the other, and it worked like a charm.

Most people think crocs are ancient animals that were around at the time of the dinosaurs, but that’s obviously not true. Far from being primitive, they have the most complex heart structure in the animal kingdom. They can actively control some of the valves in each of the four chambers of their heart – a talent no other vertebrate species can achieve. They do this to regulate the flow of blood and oxygen around their bodies, giving them the ability to remain submerged for extended periods. By using their heart and lungs in the same way we might use a scuba tank, crocs can open and close valves to let only small amounts of blood and oxygen flow – just enough to maintain adequate circulation. Using this method, a saltwater croc in Australia once stayed submerged for almost seven hours. Scientists still don’t fully understand how the crocodilian heart works.

Crocodiles around the world are having a tough time, and it’s not easy to convince the general public that they deserve protecting. Not only are crocodiles less cute than may other endangered animals, they’re also considered deadly and dangerous – not qualities which endear people to cherish or protect them.

The biggest issues facing endangered crocodiles are environmental, as their habitats are being reduced and degraded by the sheer number of humans on the planet. Until a solution to the problem is found, zoos such as Crocs of the World are the last hope for these animals. Maintaining a captive collection of endangered species can act as a safety net, a kind of ark to keep the species alive should all of those in the wild become extinct. To find out more, and to help save these animals from extinction, visit Crocs of the World. I’m sure you’ll agree, even crocodiles deserve protecting.

www.crocodilesoftheworld.co.uk

Colin Stevenson

Colin Stevenson

Colin’s book, Crocodiles of the World, is a fascinating read. It covers the ecology and biology of crocs, detailing every species and the messy taxonomy in use today. It covers reproduction, habitat and conservation and, it has lots of pictures.

“I wrote the book because there’s not much information available about crocs which isn’t aimed at either children or scientists. I’ve tried to make the book interesting and accessible for everyone, but with enough detail and data to appeal to those with a specific interest.”

Colin Stevenson

By Colin Stevenson

By Colin Stevenson

Publisher: Reed New Holland

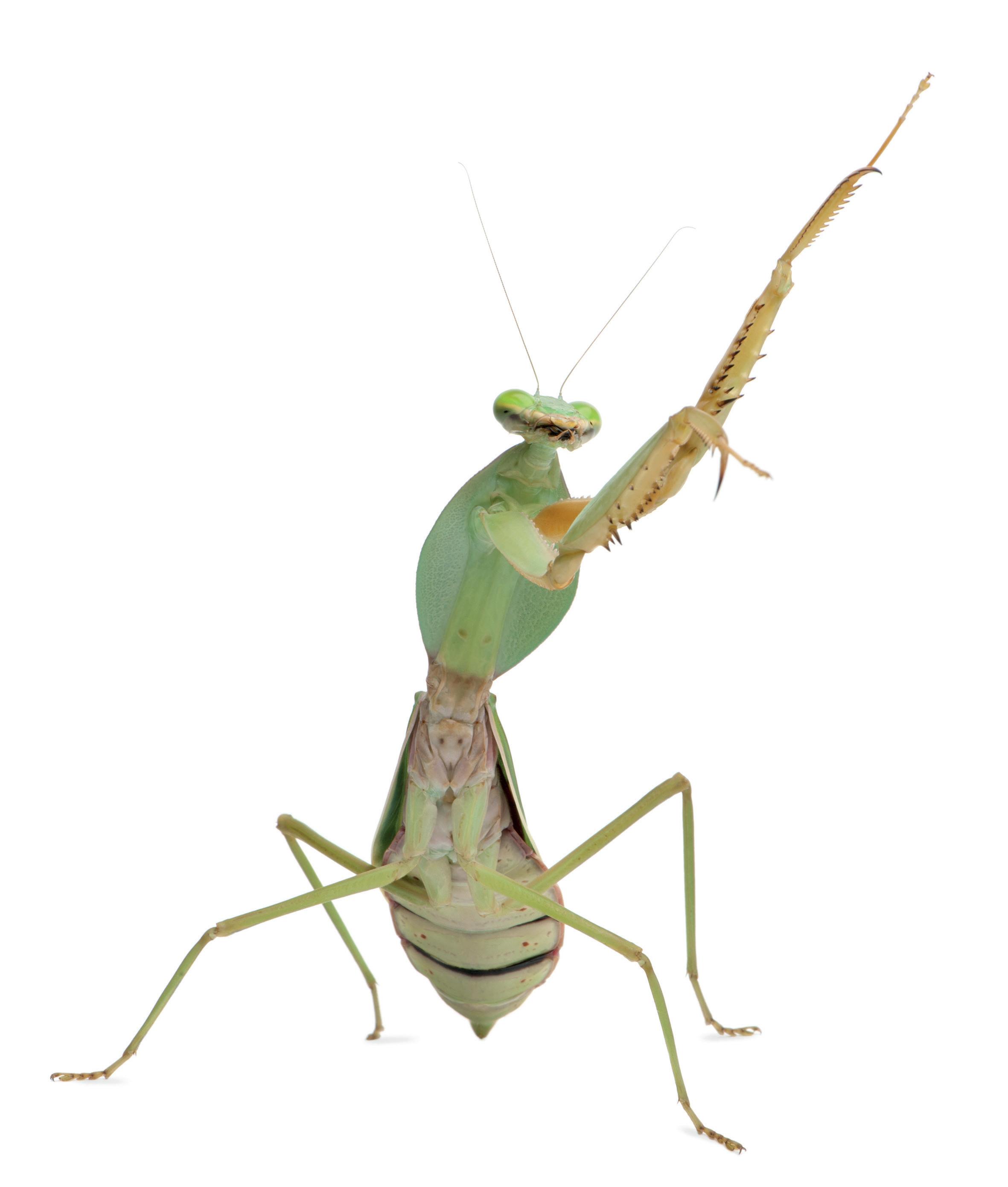

We all know the praying mantis has a fearsome reputation, notorious for the females’ habit of eating the male after mating – and sometimes even during!

But did you know that various species of mantis also prey on hummingbirds? An international study recorded 140 cases of mantis using their super-fast reflexes and spiked legs to pluck the inquisitive birds out of the air.

There are records of predation on birds by 12 mantid species in the genera Coptopteryx, Hierodula, Mantis, Miomantis, Polyspilota, Sphodromantis, Stagmatoptera, Stagmomantis, and Tenodera.

Gruesomely, in several cases, the mantis only ate the birds’ brains.

“Bird Predation By Praying Mantises: A Global Perspective,” The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 129(2), 331-344, (1 June 2017)

Whether it’s crickets and locusts or cockroaches and bean weevils, there’s a lot to learn about livefood. EK Magazine editor Tony Jones digs deep into the bug-life to explain everything keepers need to know.

SO MANY BUGS

Most pet stores which cater for reptiles and exotic pets will supply a decent range of the most popular livefood options. Crickets, locusts and mealworms will almost definitely be available, and perhaps a few morio worms and wax worms too. Specialist stores will usually have a wider selection, extending to cockroaches, snails, worms, flies and more. We’ll go into more detail about the features and benefits of each species later in this article, but for now, let’s look at how to shop for the best bugs possible.

Storage and shelf life are important considerations for stores selling livefood. While it might seem like the obvious thing to do, storing tubs of bugs near to warm reptile enclosures or in a shop window isn’t a great idea. Instead, they should be kept cool in a kind of suspended animation to keep the insect’s metabolism low. That’s because warm bugs will want to feed, and an insect that feeds will need to defecate. Warm bugs will eat their fellow tub mates or the moist faeces they produce. For the record, storing livefood at temperatures around 15° – 18° C is best, although during the summer this might be difficult.

Most stores get fresh deliveries of livefood on the same days each week. Find out from the store which days their fresh stocks are due. That way you can buy your bugs when they’re in tiptop condition.

All invertebrates have an exoskeleton which they will shed each time they grow. Each growth stage is called an ‘instar’, with the first shed called the 1st instar, the second shed is, obviously, 2nd instar, and so on right up to adulthood. Fully grown crickets and locusts are easily identifiable because they have wings. For most livefood species, stores will have a selection of sizes available –small, medium and large etc. Choosing the correct size to feed to your animal is important.

While it can be fascinating to watch mammals and birds devouring giant bugs, it’s not a good idea to feed large prey items to reptiles or amphibians. As a guide, choose bugs which are approximately the same size as the distance between your animal’s eyes. This will ensure the bug can be easily swallowed and efficiently digested, thereby reducing the risk of blockages and digestive issues.

Medium and large-sized bugs are invariably the most popular size, so stores will stock more of these than any other. Other sizes are usually in less demand so, if you regularly need small bugs, it might be worth asking your store to order them especially and keep them to one side for you. Some stores even provide a weekly delivery service, a loyalty scheme or some kind of preferential service for regular customers. Getting to know the staff at your store is always a good idea!

There’s a lot more to livefood than first meets the eye. It might seem as simple as buying a tub of crickets or locusts, lifting the corner of the lid and shaking a few bugs into your animal’s enclosure, but nothing could be further from the truth. Conscientious keepers put as much effort into their livefood as they do into the animal they’re keeping, which makes a lot of sense. After all, you are what you eat.

Of all the different livefoods available in the UK, locusts are by far the biggest seller, clearing three times the number of tubs as their nearest rival –the brown silent cricket. Mealworms come in a close third, followed by wax worms and black field crickets respectively, both a long way behind the top three best sellers.

If you want to use some of the more unusual species of livefood on the market it’s usually a good idea to let your store know what you want well in advance, as most stores will need to order these in especially.

The worst thing you can do with your crickets and locusts is to leave them in the tub. While stores need to keep livefood cool to keep the bugs’ metabolism low, this is only good practice for short periods while they are kept in the tubs for sale. Once home, the aim should be to ensure the bug you feed to your animal is as nutritious as possible.

The best way to go about this is to set up the bugs in an enclosure where they can be properly fed and watered – a process known as ‘gut loading’. Crickets and locusts especially lose a great amount of their nutritional value if their digestive systems are empty because of their fast metabolism. A hungry bug will use their body tissue as energy, leaving only an empty, fibrous exoskeleton shell for your animal to eat.

You’ll need a ventilated, escape-proof container to house your bugs, plus some form of heating so they can efficiently digest their food. A heat mat works well for this. They’ll also need something to use as a perch. Egg boxes and trays are ideal because they’re cheap, easily available, biodegradable and disposable.

There are plenty of good gut-loading bug foods available, so provide a shallow dish of this in your bug enclosure at all times, and be sure to change it regularly. Finally, it’s important to understand how vital moisture is to crickets and locusts, given that it makes up the vast majority of their diet. Slices of potato and carrot are great for crickets, and locusts will relish leafy greens, but you can also use bug-gel products used to provide water for spiders and other invertebrate pets. The choice is yours.

You’ll need to think about supplementation well in advance of feeding time to ensure you have the right products at your disposal. Most animals will benefit from a vitamin and mineral supplement, invariably containing calcium, and likely a vitamin D3 component too. Some species even benefit from nectar supplementation. You’ll find that there’s a staggering array of supplement products on the market, each servicing husbandry or species-specific needs. To do the topic justice would need an article of its own, so be sure to research your animal’s specific needs.

Most supplements come in the form of a powder and can be applied to the livefood by putting both bugs and supplement in a plastic bag and shaking them together until they are coated. There’s also a range of bug-dusting and feeding tools available, so it’s worth asking about these when you’re next in store.

Be sure to only provide as much food as your animal can eat in a sitting. It’s worth counting how many bugs you feed at each session and varying the number offered accordingly. If your animal eats them all within a couple of hours, offer a few more next time. If they leave some running around the enclosure, offer fewer. It’s also important to remove any uneaten bugs. Some people say this should be done after 30 minutes, some say you can wait a few hours before doing so, but removing them is a must regardless.

It’s important for two reasons. Firstly, hungry bugs can and often will attack your animal. Quite severe injuries and even deaths have been recorded where uneaten livefood prey has attacked pet animals which were supposed to eat them, and lesser injuries are relatively common.

Secondly, you’ll remember that the vast majority of an invertebrate’s diet is moisture. A hungry bug will chow down on whatever moist substance is available to them, and in a reptile enclosure that’s often going to be reptile poo. Leaving livefood uneaten in your animal’s enclosure for extended periods means you’ll likely be gut-loading it with poo, rather than good, nutritious food. Not good!

Feeding time is one of the most fascinating aspects of animal keeping, and livefood being stalked, captured and devoured is particularly enthralling to watch – if a little gruesome at times. However, there’s a health issue which many reptiles, amphibians and exotic pets suffer from which is rarely discussed, and it’s a problem that’s becoming increasingly common. I’m talking about obesity. Fat lizards might look cute, but the health risks associated with this condition are just as serious for pets as they are for humans. It’s worth remembering that we, as keepers, are entirely responsible for the health and wellbeing of our pets and have the power to moderate the volume and type of food we provide. Obesity simply does not occur with these animals in the wild.

Finally, no conversation about livefood and feeding would be complete without mentioning the importance of variety. In the wild animals would eat an enormous variety of different foods, and it is our responsibility to try to emulate this as closely as possible. Feeding just crickets or just locusts isn’t ideal, especially as there are so many alternative choices available. There’s simply no excuse for not mixing it up a little.

The selection of livefood options available today is amazing. Knowing what they’re good for, how to use them and what benefits they provide for your animal will make all the difference, from improved nutrition and health to better welfare and increased enrichment opportunities. Know your bugs and mix up the menu at feeding time.

Check out the guide on the following pages to find out all you need to know.

House crickets have been a favourite for decades, and for good reason. They’re easy to produce and resistant to cold, making them suitable for shipping during the cold winter months. They’re ideal for all of the most popular insectivorous animals and, if it weren’t for the cricket virus, these would likely be the only brown cricket available in the trade.

The story of house crickets is an interesting one. The species was once the backbone of the livefood trade and the most popular prey insect, until the late 1990s when they were essentially wiped out by a paralysis virus which affected captive colonies all over the world. It’s not entirely clear where the virus came from but its effect was devastating, killing the insects before they could reach maturity.

As a result the trade switched to producing other cricket species, such as silent crickets and banded crickets, which we’ll discuss later. A few people attempted to breed A. domesticus in the following years, but most failed as the virus took hold. Only a handful of small colonies were able to exist virus free. Only in recent years have virus-free colonies been able to establish themselves, but the virus worry remains a constant threat.

Although this species is quieter than other crickets, it is something of a misnomer to call it silent. Male silent crickets do chirp when they reach adulthood, and indeed, this species is more commonly called the Jamaican field cricket in entomological circles.

These became the most popular and best-selling cricket species following the cricket paralysis virus which killed off house cricket colonies. They are similarly slowmoving, but can be aggressive. They also grow quickly and get to be somewhat bigger than house crickets, which makes them a good option for larger pet reptiles such as beardies, but some care is needed if customers are buying food for smaller species of reptiles or amphibians. Should a small silent cricket get lost in an enclosure, they could quickly grow to become predatory monsters for small herp species such as Dendrobates.

From a business perspective, some cricket producers are less enamoured with this species because they are not as prolific and must be kept in lower densities, which means fewer can be produced in the same square footprint of space. As a keeper, this won’t bother you too much though. Silent crickets are a fantastic livefood and, so long as common sense is used to select the right size, these are a great prey item. It’s no surprise that these are the most popular brown cricket in the pet trade.

This species was another which came to the market because of the paralysis virus which killed off house cricket colonies. They’re fast and jumpy, which means they’re difficult for some animals to catch, and they’re more likely to escape and get lost in the keeper’s home.

As a tropical species it’s not keen on cold weather and susceptible to dying during transit if shipped in the colder months – a real pain when your store’s cricket delivery arrives DOA. They’re also more aggressive and likely to turn from prey to predator if they get left uneaten. They are a relatively smaller species which, depending on the animal you want to feed, can be a pro or a con.

They’re bred in the trade because they’re easy to produce in high numbers, making them a more profitable option – if you ignore the husbandry issues. They also do well in tubs, providing a better shelf life, but this shouldn’t be a major consideration for those who keep and gut-load their livefoods properly.

It’s a mystery why these crickets are at all popular in the pet trade, given they are almost identical to the Silent cricket in behaviour and appearance, colouration aside. They’re from the same family of crickets as the silents, but have a major disadvantage. They can be a bit stinky. The pheromone odour this species emits when stressed is off-putting to many animals, and those which have never seen a black cricket before will often refuse to eat them. They’re also the noisiest of all the cricket species produced for the pet trade.

On the plus side, this is a relatively cold-tolerant species which ships well during the winter. And some keepers like them, usually oldschool keepers for some reason. While there’s a market for them then producers will continue to sell them.

Desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria)

Locusts are by far the most popular and best-selling livefood on the market today. There are several reasons for this, most notably the benefit of convenience for the keeper. Crickets can easily escape and evade recapture, progressing to hide away somewhere in the home to chirp annoyingly for days or weeks on end. Add to that the fact that few normal people (as opposed to exotic-animal enthusiasts like us) are happy with the idea of having free-range insects in their home, and you can see why locusts are the go-to livefood choice for many.

However, the real market driver for locust domination has been the popularity of the bearded dragon as a pet. Locusts are, of course, an ideal choice for these popular lizards, and as beardies become ever more popular, so will locust tubs. Leopard geckos and Yemen chameleons also favour locusts, thereby compounding their dominance at the top of the livefood sales league. Chameleon keepers particularly favour locusts as they will more likely climb up branches inside the enclosure to be eaten, rather than hiding in the substrate like a cricket often will.

The vast majority of the locusts available in the trade are the desert locust – Schistocerca gregaria. These took over from the historically popular migratory locust Locusta migratoria, sometime in the 1990s, but the differences between the two species are slight, the main difference being appearance. Desert locusts are vastly more colourful, thereby making them more appealing to the eye than Locusta. Desert locusts also grow to be slightly larger.

mealworms. And finally, they’re slow moving and won’t jump around out of reach as a cricket or locust will. When mealworms are placed in a bowl with a good quality dusting powder, animals are more likely to get a good dose of vitamins and minerals – unlike crickets and locusts which can shake off much of the powder they are dusted with before they are eaten.

These have been treated with the juvenile hormone methoprene to inhibit metamorphosis to a beetle, so the worms remain in the larval stage for longer. They continue to grow and get to be around the same size as morio worms.

Mealworms have traditionally received a bad press, but this is massively unfair. The old wives’ tale about mealworms eating their way out of the stomach of lizards, thereby killing them, is indeed that – an old wives’ tale. The myth likely came about when keepers would find a dead lizard in an enclosure and see mealworms crawling out of the corpse. The more likely explanation is that mealworms had made a meal of a lizard which had already died, eating their way inside their body, rather than eating their way out after being consumed.

In reality, mealworms make an ideal livefood for several good reasons. They’re high in fat and perfectly nutritious for a start, especially when gut-loaded and dusted as they should be. Secondly, they’re relatively cheap, as is witnessed by the fact that several largescale lizard producers feed their livestock primarily with

Best of all, mealworms can be stored in the fridge which means they require virtually no maintenance until just prior to feeding.

Mealworms come in a few sizes, but there are some interesting points to remember when choosing your livefood. Mini mealworms are simply younger mealworms and are more or less the same with regard to nutrition. Bigger mealworms come in two different varieties. The most popular is morio worms (Zophobas morio), a different species from the regular mealworm and mini mealworm. These are naturally much larger than a regular mealworm and, therefore, a more suitable prey for larger herp species. Morio worms should not be confused with the visually similar ‘giant mealworm’.

There is some anecdotal evidence regarding the effects of methoprene on both insects and reptiles. Livefood breeders report problems when methoprene somehow contaminates other invertebrate species, thereby impeding reproduction. There have even been reports from gecko breeders who are convinced of reproductive issues in their breeding colonies.

After all, most pet keepers won’t breed their animals and the small amounts of hormone left in the system are likely negligible.

Mealworms and giant mealworms can be refrigerated for storage. Morio worms cannot be refrigerated because they will die.

Buffalo worms are about the same size as, or slightly smaller than, the mini mealworm. There’s not much to discern between the two species apart from a slightly shinier exoskeleton and some small, nutritional differences. That said, nutritional variety is an important component of animal husbandry so any opportunity to add variety should be a consideration. More importantly, there is often an annual shortage of mealworms, usually around the spring or summer when they become a popular product for bird tables. Buffalo worms are a perfect alternative to fill this gap, so don’t worry if your store switches to these during the annual shortage.

However, there is currently a supply and demand issue. Sales of buffalo worms are such that breeders and suppliers don’t always produce or stock enough of this species to fill the gap that is created when mealworms aren’t available. If more stores stocked buffalo worms throughout the year then demand would increase to the point where breeders would produce more, and likely have a greater capacity to supply buffalo worms when required. It’s worth thinking about!

We really need to talk about wax worms. When we think about nutritional variety or offering a different insect prey item as a treat, the most common response is wax worms. While wax worm sales are dwarfed by those of crickets, locusts and mealworms, they are by far the largest livefood line thereafter. No other livefood comes close in terms of sales.

This is a little baffling as wax worms aren’t a great food item in terms of nutrition. The wax worm’s diet means that their gut is filled with sugary food, making them a bit like a dessert for your animal. This should mean wax worms are used as no more than a very rare treat, so their current elevated position on the livefood league table seems rather unjustified.

It’s not that wax worms should have no place in the market. They’re great for a very occasional treat. But figures show that wax worms are more popular than they deserve and, a bit more variety in the types of livefood species being used would be a move in the right direction.

Sugary treats such as wax worms can cause problems when animals take a liking to them. It’s very much like trying to feed broccoli to children while they’re eating an ice-cream, and there have been countless reports of animals going off their (less tasty) foods in favour of wax worms. Amphibians seem to be particularly picky when spoiled with wax worm treats.

Calci worms are the soft bodied larvae of the black soldier fly and are so named because they contain up to 60% more calcium than other feeder insects. They are low fat and have a well-balanced calcium to phosphorus ratio, which means they can be used as a more regularly offered food item. As grubs go, they’re a far healthier option than the highly-calorific wax worms, which are, for some reason, significantly more popular.

The calci worm’s high calcium content occurs because the larva stores calcium to use as a protective shell when they pupate, essentially armour plating them from predators during the vulnerable metamorphosis stage of life. All told, calci worms are an awesome livefood choice.

These are another great worm to use as a treat for larger species such as bearded dragons, tegus and larger chameleon species, as well as many mammals and birds. The proliferation of bearded dragons as pets is probably the main reason why pachnoda grubs are fast gaining in popularity.

Cockroaches have become an enormously popular livefood option over the last few years, and rightly so. Nutritionally speaking, they’re considered a ‘superfood’ by many keepers, and are particularly favoured by bearded-dragon owners.

Unfortunately not everybody is fond of the idea of having cockroaches in their home and therefore shy away from using them. This is such a shame because, in reality, cockroaches are custom-built for the needs of moderate and large-sized reptile species, such as beardies, tegus and monitor species, as well as many mammals and birds. Big tarantulas seem to particularly like them too.

Nutritionally they’re at least as good as most other livefood species, so if you can get over the fact that they’re a cockroach then everyone’s a winner. B. dubia is the most popular species available in the trade at the moment but other species are available and likely to become more popular in the future.

The variety of available livefood species has mushroomed over the last few years and several producers now specialise in a number of invertebrates for specialist markets and keepers who want variety in their animal’s diet – a pleasing advancement in husbandry which is quickly gaining traction. It’s another great example of how the reptile-keeping hobby continues to grow and improve.

Although woodlice are more often used as a clean-up crew in bioactive enclosures, they can also be considered a prey item, and they are readily eaten by some species of reptiles and amphibians. Their highly calcified exoskeleton will provide invaluable nutrition, but they are, unfortunately, not produced on a large enough scale to become a mainstream food item.

As a general rule, beetles aren’t a good livefood due to their hard shell and toxic secretions. This is why stores don’t sell mealworm beetles as a food item, despite having plenty of these from our mealworm suppliers’ breeding colonies. Few reptiles or amphibians favour them, apart from Bufo sp. toads, which will eat almost anything.

Bean weevils are an exception to this rule. They have a far softer shell which means many herps find them palatable, particularly small arboreal species such as anoles and small day geckos. Bean weevils are just the right size and seem to climb up to be greeted and eaten by these small arboreal predators.

These are another invertebrate species used predominantly in bioactive enclosures, but again, they’re fine for use as a livefood item for very small animals. Springtails are particularly popular with amphibian breeders who need the smallest possible prey for newly metamorphosed froglets and toadlets.

Beware though, because their ability to climb means these bugs are also expert escape artists. They’ll easily scale glass and escape through ventilation or door seals, and sliding glass doors are no obstacle. Bean weevils are easy to breed and many keepers set themselves up with a colony before eventually realising it’s easier to spend a few quid on a tub from their local pet shop than it is to maintain a colony at home.

Curly wings are simply a house fly afflicted with a genetic mutation which deforms their wings to render them flightless. Large poison dart frogs will love them, as will praying mantis, anoles, small geckos and tree frogs. As well as adding that all-important dietary variety, curly wing flies are a great way to add enrichment for fast-moving species which will go crazy chasing these bugs around their enclosure.

These are another reasonably popular prey insect and, although few animals are small enough to eat them, they’re a great livefood option for animals such as dart frogs and smaller species of lizards during the early stages of life.

Lobworms are great for larger amphibians such as axolotls, whereas the surface worm is good for smaller salamanders, newts and lizards. The market for these isn’t huge and they are usually only available to order, but they’re a great way to add variety to your animal’s diet.

Here’s another hugely underrated livefood that deserves to be more popular. Their slow moving nature, along with the nutritious lump of calcium on their back, are probably their main points of appeal. That said, the shell of captive-produced snails are thinner due to them being grown on quickly, making them much easier to eat.

Monitors, tegus and even beardies will love snails, as will blue tongue and pink tongue skinks. Toads seem to be rather partial to the odd snail too. In fact, you’ll be surprised at what will eat them. Beware that some animals will love them so much they become picky. But as an occasional addition to an otherwise varied diet, snails are a fabulous addition to the menu.

It’s often said that there’s no such thing as a vegetarian snake, but that’s not strictly true. Several species of snake eat an exclusively egg-based diet which makes them vegetarian. Unfortunately, these species are not easy to keep and rarely available to buy as pets.

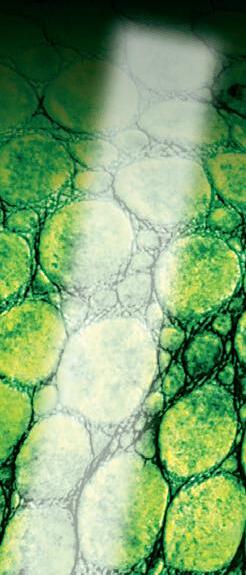

However, there is one snake that is easy to keep, often available and doesn’t eat vertebrate prey. Rough green snakes eat a wide variety of insects, such as crickets, mealworms, calci worms and earthworms, which makes them an ideal snake for people who don’t fancy feeding rodents to their pet.

While rough green snakes can be gently handled occasionally, they are often nervous, fl ighty and fast moving. Most keepers agree that rough greens are more fun to watch than handle, particularly when they’re hungrily chasing insects around their enclosure.

What’s not to love about these fascinating marsupials? Jim Collins reveals some surprises about sugar gliders and their sometimes not-so-cute habits.

“They only come out at night, they’re extremely messy, and they smell really bad,” explains Jim, when I ask him what it’s like to keep sugar gliders. I laugh, because I know he’s only teasing. Jim has been keeping and breeding these adorable creatures for decades, and there’s no mistaking his fondness for them. However, he’s also very clear that, despite their doe-eyed cuteness, friendly persona and simple husbandry requirements, sugar gliders aren’t for everyone. But let’s start at the beginning…

Sugar gliders are common in the wild with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listing them as ‘least concern’. Although split into several different subspecies the validity of these is suspect, with DNA research suggesting that the distinctions between them are but slight.

The sugar glider’s scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, translates from Latin as ‘short-headed rope-dancer’, no doubt as a reference to their canopy acrobatics.

They are prolific in northern and eastern Australia. They can also be found in New Guinea and a few Indonesian islands, and they were introduced to Tasmania in 1834 soon after a seaport was established. Gliders were brought to the island as pets and inevitably became established there. Unfortunately the species has become a threat to the native Tasmanian swift parrot. The reduced mature forest cover has left the parrots’ nests vulnerable to predation from sugar gliders and it is estimated that the parrot could be extinct in the next decade.

Records show that sugar gliders were being kept as pets as early as the 1830s, but their appearances in Europe were largely restricted to being zoo exhibits until they appeared on the lists of European pet dealers in the late 1980s. Jim was one of the first, if not the first, to bring gliders into the UK, having transported a shipment of 14 gliders from Berlin back in 1994, the founder stock of which came from a continental dealer importing from West Papua, Indonesia. These were closely followed a year later by another 25-strong captive colony from Stuttgart Zoo, which were requiring a new home after the building containing the sugar glider exhibit at the Zoo was demolished.

These two unrelated populations created the foundations of two breeding colonies which still exist today, albeit fortified with specimens from different sources over the forthcoming years. Jim still breeds sugar gliders, maintaining around 30 animals in two separate groups, housed in large aviary type accommodation.

I’d seen sugar gliders in zoo exhibits in the early 80s and was fascinated. Even then they struck me as being an ideal candidate for a pet species, given their propensity to form sociable groups. As with most sociable animals, the need to form a bond can become a companionship between the animal and their keeper.

This idea turned out to be fact, evidenced by the many sugar gliders being kept by pet keepers in the USA in the years to come. By the time I had my own colony, keeping gliders as pets was becoming popular all over the world.”

Jim Collins is renowned among exotic animal keepers, having kept and bred countless species of birds, mammals and reptiles. However, his love for one animal has endured for almost thirty years. That animal is the sugar glider. EK Magazine editor Tony Jones finds out how to properly care for these adorable creatures.

The relatively large colonies which Jim maintains mimics the close social groups seen in glider communities in the wild. To my surprise, Jim explained that his colonies each contain several unneutered males which live happily together – an arrangement that flies in the face of the common consensus which emphatically states that, under no circumstances, should unneutered males be kept together.

“It’s probably true for most people who keep two or three animals as pets in conventional enclosures. I expect smaller enclosures might create increased competition between unneutered males. However, there’s more than one way to keep sugar gliders.

“Zoos have kept big colonies of gliders with unneutered males together for decades and that’s essentially how I keep mine –large colonies in much larger enclosures. We’ve had very few occasions where males have been kicked out of a group, and inter-male aggression is almost unheard of. On the very rare occasions where we have had issues it’s usually a single male which has been excluded from the communal sleeping nest. In these circumstances we simply remove the male to a separate enclosure, pair him up with a female, and rehome the couple to another keeper.

But, as I said, this is such a rare experience that we don’t need to worry much about multiple males being kept together.”

Jim’s enclosures are indeed huge and far larger than the 4 x 2 x 2ft cages or vivariums routinely used by pet keepers. The aviary-style accommodations are more like 14 x 6 x 8ft high, and also, notably, feature multiple nest boxes.

“They’re largely for show, because all of the gliders will inevitably sleep together in the same box,” explains Jim. “If a glider sleeps in a box alone, I know something’s wrong.”

The sugar gliders we see in the pet trade originate from New Guinea, according to the previously mentioned DNA analyses, which came as a disappointment to those who had accused the trade of importing the species illegally from Australia.

Sugar gliders are relatively simple to care for compared with many other exotic pets. In years past, calcium deficiency was occasionally a problem for the species, invariably manifesting as hind-leg paralysis. However, this condition is not so often seen today as commercial foods and keeper education have resulted in far better diets for captive gliders.

“Sugar gliders are truly omnivorous in the wild,” says Jim, “and that means variety is essential. Gliders in the wild will eat anything, from bugs, grubs, lizards, birds and eggs to fruit, veg, flowers, nectar and sap.”

The sweet sap and nectar components are particularly interesting and likely account for the ‘sugar glider’ moniker. In the wild during the winter months when bugs and fruits are less available, sugar gliders will peel bark from eucalyptus trees and drink the resulting sweet sap. However, captive diets should be largely devoid of sweet foods with such treats being offered only rarely. More on that later.

“My gliders are fed a mix of sweet potato, sugar-snap peas, and smaller amounts of fruit, as well as a variety of livefoods. I also use commercial sugar glider diets, including nectar and acacia exudate food – acacia gum essentially.”

The mention of livefoods might also raise a few eyebrows if you were to mention it on sugar glider internet forums or social media pages. Again, the common consensus makes some assumptions when it recommends avoiding livefood for gliders – the assumption being that crickets and locusts bought in tubs from the pet trade are poor in nutrition. Of course, most keepers know that gut loading and dusting works wonders and these practices should be employed as a matter of routine when using livefood prey. Under this protocol we can be more confident of the nutritional value of our livefoods, but you can see how half-truths such as this gain traction on the internet.

You’ll no doubt recall the introduction for this feature which cast some rather harsh aspersions on the sugar glider’s appeal, but there’s no getting away from the fact that all of these accusations are true.

Sugar gliders’ nocturnal habits were easily negated by zoos who exhibited sugar gliders in reverse-lit twilight exhibitions, lighting the gliders’ enclosure brightly during the evening and night time, while plunging them into semi-darkness during the daytime when visitors wanted to see them. The enticing flash of a shadowy figure bounding through the foreground beyond the glass was fascinating enough to please visitors eager to catch a glimpse of these enigmatic creatures. For pet keepers, though, the normal day and night photoperiods are usually maintained intact, with the glider sleeping while the keeper is at work during the day, and coming out of the enclosure at sunset to enjoy some interaction time.

This is also one of the reasons why it is not common for sugar gliders to be kept in bedrooms, as they will undoubtedly make so much noise during their night time activities to disrupt even the soundest sleeper. But there’s also another reason why keepers prefer not to sleep in the same room as their gliders, and that’s the smell.

Sugar gliders primarily communicate through their sense of smell. While females do have cloacal glands, it is the males which scent their habitats routinely and liberally. It’s just something you have to live with, but sleeping in the same room is probably asking a bit much. There are ways to negate some of the smell, but there’s no way to eliminate it. It’s a mistake to attempt to clean the enclosure in a bid to get rid of the scent, as this will simply compel the males to scent even more. Instead, keepers will clean parts of the enclosure in rotation, thereby reducing the smell in one area, but leaving enough of a scent to keep the male happy in his domain.

COMMON NAME

SUGAR GLIDER

SCIENTIFIC NAME

PETAURUS BREVICEPS

ORIGIN

NORTH & EAST AUSTRALIA

NEW GUINEA

INDONESIAN ISLANDS

TASMANIA

HABITAT

TROPICAL & COOL TEMPERATE FORESTS

SIZE

LENGTH 16 – 21CM

WEIGHT 116 – 160G

DIET OMNIVORE LONGEVITY

3 – 9 YEARS IN THE WILD

10 – 15+ YEARS IN CAPTIVITY

IUCN REDLIST STATUS

LEAST CONCERN

Neutered males will not scent much at all, but neither will they breed, obviously.

In addition to the smell caused by male scenting is the smell caused by urination and defecation. Sugar gliders cannot be trained to use a litter tray, so will urinate and defecate wherever they stand, whether inside the enclosure or out and about in the home. Similarly, their ability to flick food and other detritus as they leap from branch to branch could almost be called impressive, as they will happily walk through food or faeces, which then gets thrown from their feet as they bound.

This is less of a problem for keepers who use vivariums as enclosures, but those who use cages will need a plan if they are to avoid the mess expanding beyond the enclosure.

Cages are also a consideration when it comes to security. Gliders are notorious escape artists and will persevere at any opportunity which they can exploit to achieve an escape. Be warned that sugar gliders would have no chance of survival during a British winter. With no colony to huddle with and a dearth of food, they would perish quite quickly outside, so it’s vital keepers be doubly sure that there is no way their glider can exit their enclosure unsupervised. Bars must be no more than half an inch apart and such that they cannot be chewed through. Any hinges or fastenings must be strong enough to resist them being bent enough to create a sufficient gap, and ventilation must be robust enough to resist the chewing for which gliders are renowned. Which brings us nicely onto enrichment.

It is imperative that you provide opportunities for gliders to chew. In the wild the pursuit of sap by chewing bark would form a significant part of a sugar glider’s day. This can be facilitated simply by offering branches inside the glider’s enclosure. Use branches of different sizes, girths and types, but avoid any toxic varieties. “I often use willow and hazel,” says Jim. “They’ll keep the gliders occupied for hours and will also keep teeth and claws nicely trimmed.”

Many keepers will also provide running wheels, which the gliders seem to relish. It’s important to avoid wheels with ladder-rungs, and, instead, use solid-floor wheels as this stops the gliders’ delicate limbs and tails being trapped. Some keepers opt for wheels with abrasive sandpaperlike coating which, again, helps to keep claws from becoming too long.

Overall, health issues are relatively rare with sugar gliders. As mentioned previously, calcium deficiencies were a common problem in years gone by, but are only occasionally seen today. Calcium supplements, commercial diets and good keeper-knowledge about calcium and phosphorous balance (2:1) means that nutritional deficiencies are largely a thing of the past

A problem which does occasionally occur with pet gliders is a side effect of keeping gliders in centrally heated homes. The sugar gliders we keep in captivity hail from New Guinea and are, as such, conditioned to require an amount of humidity. While the required humidity parameters are generous, the dry environment caused by central heating can result in skin conditions, with the first sign of a problem being dry, flaky ears. In severe cases the ears can dry to the point where they flake away to dust. This issue is most often observed during the winter months when the household’s central heating is fired up, rather than in the summertime when it is switched off. Low humidity issues are easily avoided through frequent spraying, particularly by spraying within the animal’s hides to create a humidity shelter while avoiding spraying the bedding material.

“The biggest health issue facing sugar gliders is the same one which afflicts most pet species – the keepers are killing them with kindness,” sighs Jim. “Too much sweet food, too many sweet treats and not enough activity. I could be talking about dogs, cats, reptiles or birds and the story would be the same.”

It’s true. Gliders are programmed to eat whatever is available, whenever it is available and, if sweet treats are on offer, this is what they will favour. “They’ll prefer morio worms, sugary wax worms or fatty pachnoda beetle larvae over crickets or locusts, and will choose mango over peas any day,” says Jim, “so offer these rarely only as a treat or an enticement.”

As is seemingly the case with most pet animals, obesity is the biggest health issue presenting in sugar gliders today. Rounded faces and double chins are the tell-tale signs of a keeper who feeds a sweet or treat-laden diet to their pet.

Interaction and companionship is another hot topic in the sugar glider world. While you will hear some debate, Jim is of the opinion that sugar gliders live in groups and should not be kept as single animals. “It’s not common, but you will see gliders being kept as singles, particularly in America where they are sometimes sold and branded as some kind of ‘pocket pet’. I’m of the opinion that unless you are going to spend the whole of every evening with your glider then they will need a companion of their own species.”

This makes lots of sense. Most humans sleep during the night and go out to work for most of the daylight hours. Your glider will be asleep during the daytime, but it will be awake and active during the evening and night time. To deprive these sociable animals of companionship while you are asleep would undoubtedly compromise their welfare. Providing at least one companion is imperative.

“If you have a happy pair of established sugar gliders they’ll likely breed.”

Jim Collins

Handling and interacting with sugar gliders is a big part of their attraction. While sugar gliders can bite, and will if provoked, it’s almost unheard of for a glider to jump onto you in order to bite. Most bites occur if a glider is being restrained, so every effort should be made to avoid this.

“Building trust is the key here,” says Jim. “You have to convince the glider that you’re a friend, and that you often have treats. It’s the same old trick humans have used to befriend animals for thousands of years.”

The animals in Jim’s collection are rarely handled, at least not for the sake of handling. “Mine are left to their own devices, more like exhibit animals that behave how they please. That said, some are more forthright than others. Some will voluntarily come over and jump on my shoulder every time. Some do so only occasionally if there is a treat available, while others will never come over and, instead, keep their distance. It’s up to them.”

However, for pet keepers, it is a good idea to get your glider used to being handled, if only to ensure they can be enticed back into their enclosure each night. Most are happy to do so if they think there’s a tasty morsel to eat in reward.

Inside the enclosure keepers can provide enrichment through the gliders’ natural inclination to forage. “Forage balls are great and come in a range of types and sizes. However, I also like to fill bamboo with mealworms and encourage the gliders to retrieve them from inside through pre-drilled holes. It keeps them amused for ages.” Which is an undeniably good thing, as wild sugar gliders will forage for up to twelve hours each day.

In short, keeping gliders entertained and enriched is the key to avoiding the behavioural problems which had afflicted intelligent captive animals in the past. Poorly enriched sugar gliders would pace their enclosure, back-flip repeatedly, before moving to excessive grooming and, at extremes, self-mutilation, usually at the tail. We know enough about sugar gliders and enrichment for these problems to be eradicated forever, so be prepared to intervene at the first sign of behavioural issues.

Tropical habitats, such as those in New Guinea or Indonesia, will rarely experience significant temperature fluctuations, while sugar gliders in Australia will be subject to cooler temperatures during the winter months. The glider’s responses to this are manifold. They will cease looking for bugs and will, instead, settle in areas where eucalyptus trees can be chewed to release sap from under the bark. The colony will huddle together to preserve heat, often with the dominant male fulfilling a patriarchal role by ensuring his progeny are positioned favourably within the huddle.

However, the most interesting behaviour during cold spells is for Australian gliders to enter a sort of torpor. These periods of low heart rate and inactivity aren’t the same as the extended hibernations exhibited by other animals, but more like short periods during any given cold day where activity is suspended in order to preserve energy.

In captivity it is recommended that sugar gliders are not subjected to the cooler temperatures which might induce torpor, essentially due to the fact that most pet gliders do not live in colonies in numbers which would enable them to huddle.

Ambient European room temperatures are sufficient to achieve this equilibrium. “Basically, if you’re comfortable in a tee-shirt, the gliders are happy.” Assures Jim.

In hot weather sugar gliders can be seen licking patches of their fur until it is wet enough to achieve cooling by evaporation. Given the temperatures these animals experience in the wild it is unlikely pet gliders will be subject to heat which would be detrimental, but be careful of direct sunlight and poorly ventilated spaces –common sense measures really.

“It’s not difficult,” says Jim. If you have a happy pair of established sugar gliders they’ll likely breed”. Females come into season multiple times each year and, as pairs and groups are housed together, nature will take its course. Although sugar gliders in the wild will routinely breed before they are a year old, this is largely frowned upon in captivity, as this can reduce the animal’s lifespan.

Gestation is just over two weeks’ long and babies are born as tiny, almost pin-prick-sized joeys, remaining entirely in the mother’s pouch for at least the first two months. After that they’ll leave the pouch for incrementally longer periods, but won’t usually venture anywhere outside the safety of the nest box for another two months. In that time the joey will continue to suckle their mother’s milk to some extent, and will increasingly also sample other food items.

The female’s need for additional protein during pregnancy can be satisfied by providing items such as hard-boiled eggs more regularly in their diet.

Eventually the joey will leave the nest, observing its parents’ behaviour and learning to socialise and feed independently. “Adult gliders are gorgeous, but baby gliders are even more beautiful!” coos Jim. “They’re a lovely silvery colour and their fur is much softer and more velvety. It’s a shame they don’t stay like that.”

That might be true, but I think we can all agree, sugar gliders are a delightful pet at any age.

Sexing sugar gliders is easy. Adults can be sexed visually by looking for the obvious scent glands on the male’s head and chest. Youngsters can be sexed by observing the male’s split-organ penis, or the slightly less obvious pouch of the female.

I once collected a colony of sugar gliders from a European zoo and brought them home in my car via a ferry crossing from Calais. All was well until I reached the M25 motorway, upon which point the glider noises I could hear from the back seat changed, becoming louder and more excited. I looked in the rear view mirror to see a glider bounding across the back parcel shelf, before being startled by another bouncing off the steering wheel in front of me across my field of vision.