THINK PINK

Ask people why flamingos are pink and the response will most likely be “their food”, but how does blueish grey food turn them pink?

Ask people why flamingos are pink and the response will most likely be “their food”, but how does blueish grey food turn them pink?

Can we cohabitate small vertebrates successfully and more importantly, should we?

The ability to essentially clone oneself is extremely rare amongst vertebrates, but for some reptiles, it’s just another day.

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS scott@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING advertising@exoticskeeper.com

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns Hastingwood Road Essex CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4686 Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott Aimee Jones

DESIGN: Scott Giarnese Amy Mather

It’s February and we at EK couldn’t resist getting just a little bit cheesy with this month’s Valentine’s Day themed issue. Don’t worry, you won’t find any romantic poems hidden throughout! The courtship of reptiles can be much more complex than people tend to think. From lovestruck shinglebacks to independent mourning geckosreptile romance would make an excellent reality TV show. We also look at why flamingos are pink and the role carotenoids play in the mating game as well as speaking to some leading figures on their thoughts around cohabitation.

As I write this intro, we’re planning some seriously exciting video content for our social media and YouTube channels. We’ve seen

great exclusive interviews, as a bonus to our written content. Now international travel is becoming

Follow us

Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

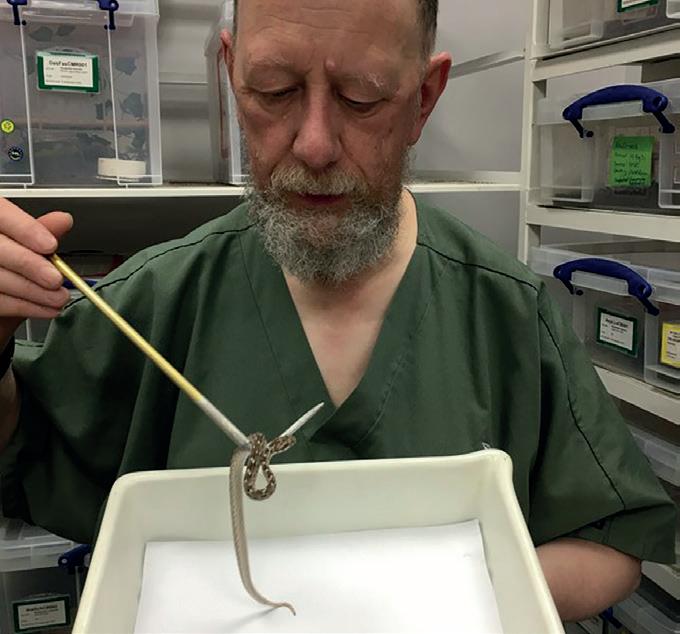

so that indicates to us that any minor, short-term, possible discomfort from the extraction process, does not stress or unduly upset them.”

Until recently, Paul was the only person in the UK extracting venom for medical research and is currently training someone else at LSTM in a similar role: “I know what I’ve done over the years has contributed to saving lives, we have produced thousands of life-saving treatments, but it really is a group effort and I’m part of many researchers and scientists.”

– where former feeding areas have been divided or access prevented by new building developments and other causes. To help “bridge” these divides the idea was conceived to provide aerial bridges for the dormice to use to access various areas that would otherwise be beyond their reach. In a similar way to other aerial bridges constructed to create safe passage above roads for squirrels and many other arboreal mammals such as primates in other countries.

In December a young Sochurek’s sawscaled viper (Echis carinatus sochureki) – one of the world`s most deadliest snakes, was found amongst a shipment of building materials from Pakistan at a clay brick importers in Manchester. With help from Chris Newman of the National Centre for Reptile Welfare, the snake was transferred into the care of specialist senior herpetologist Mr Paul Rowley at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) courtesy of the R.S.P.C.A.

The snake will join a number of others kept at the higher education institution after arriving in the UK from South Asia over the past eight years, here the team will carefully extract the venom from the snake to add to their stock of venom from hundreds of different species of snake. The venom has been used for research and collaborations worldwide to produce life-saving anti-venom. Paul said “Extractions are typically done within a few seconds, while gently massaging the venom glands situated on the side of the snake’s head. We regularly carry out extractions in batches in the morning and then offer the snakes food in the afternoon. They all readily take the food,

“These little snakes are small, the typical size is up to 30cm, but have toxic venom, enough to kill people. They are killing tens of thousands of people in areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, where it is very common for people in poor rural areas to be bitten,” explains Paul.

The People`s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) and Network Rail have joined forces to provide our native hazel dormouse with a safe method of travelling between two separated areas, either side of a railway line in Lancashire. The two areas involved are in Arnside and Silverdale in Lancashire, both are areas of outstanding natural beauty. Connecting these two areas would allow the hazel dormice populations to mix, increasing the chances of breeding (whilst also reducing in-breeding in a single location), finding nesting sites as well as increasing food availability.

Numbers of the hazel dormouse in the U.K. have dropped by 51% since the year 2000, largely due to habitat destruction and habitat separation

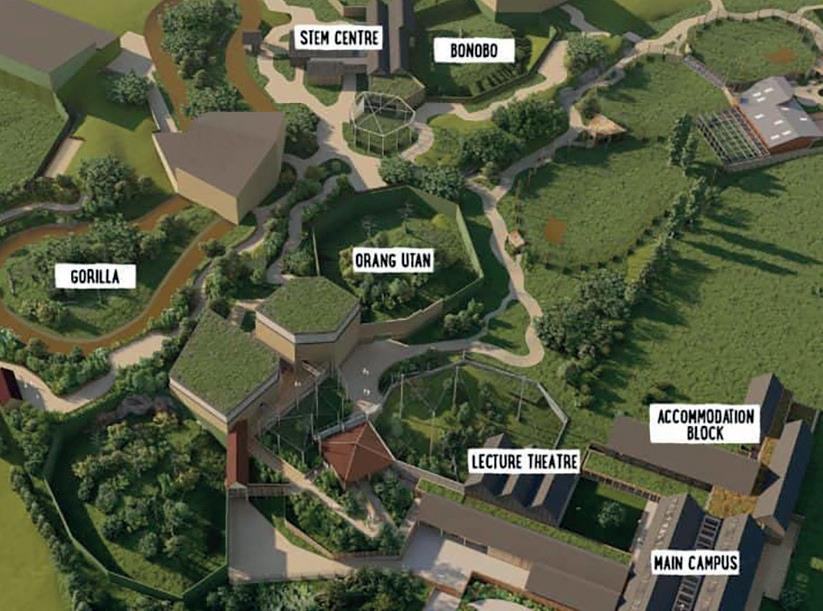

U.K.s First National Science and Conservation Centre

Following a successful bid for the Government`s Levelling Up Fund, Twycross Zoo was awarded a sizeable grant of 19.9 million pound in the last budget. The money will be used to create a large new facility for the study of four anthropoid ape species.

CEO Dr Sharon Redrobe OBE said “We are delighted to hear that our bid has been successful and without a doubt this funding will make a huge difference to the conservation of endangered species and our planet. With this new centre, we will be able to establish a national focus on protecting species from extinction, and training and inspiring the conservationists of the future.”

Bristol & Chester Zoos. Have jointly achieved a world first captive breeding of two species, out of the four species, of Desertas Island snails, which were thought to be extinct for more than 100 years ago. Conservationists from the UK and Portugal launched a dramatic rescue mission to save a group of rare snails from extinction.

Experts at the Instituto das Florestas e Conservação da Natureza IP-RAM rediscovered tiny populations of two species of the snail, each consisting of fewer than 300 surviving individuals, on an isolated island in the Madeira Archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean. These snails are part of a unique conservation recovery plan supported by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature through the Mid-Atlantic Islands Invertebrate Specialist Group and Rewild.

It began after around 60 individuals from each group were carefully collected from the island and flown 1,500 miles to the UK. The numbers were then split between Bristol and Chester Zoos where last ditch efforts took place to boost numbers and save the species.

Mark Bushell, Curator of Invertebrates at Bristol Zoo, said: “These snails are a vital part of the natural ecosystem on the Desertas Islands and are found nowhere else on the planet, so to be able to play a part in securing the future of these species is a huge privilege”

The Desertas Islands, where the snails were found, are now protected nature reserves under Portuguese and European law and have been recognised as biodiversity hotspots for rare invertebrates, birds and reptiles. The snails were classified as globally extinct in the wild in 1994, but now, following this rediscovery, both species are listed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Dr Gerardo Garcia, Chester Zoo’s Curator of Lower Vertebrates and Invertebrates, added: “These snails had not been seen for decades and were thought to have gone extinct, so urgent action was required when only a handful

of these special snails were found clinging on to survival. “Starting with just 20 of the last known individuals on the planet from each group, there was a lot of pressure to find answers quickly, but with the technical knowledge, scientific underpinning and the skills developed here at the zoo with other highly threatened invertebrates, our team was able to develop the ideal breeding conditions”

A new species of frog was found some time ago in Madagascar`s Andasibe-Mantadia National Park by Carl Hutter - a post doctorate at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. However it has only now been confirmed as a new species to science. The amphibian also has a unique call of two to four pulses followed by a long note—so quiet it can barely be heard even a few meters away. The secretive nature of the nocturnal frog, which seems to only come out of hiding after heavy rains, meant it took several trips over the years to collect enough specimens and recordings for the taxonomic description

The tiny frog which had warty skin and red eyes was discovered at high-elevation rainforest in Madagascar and has been named Gephyromantis marokoroko due to its distinctive warty skin – the scientific name means “rugged” in Malagasy. The country has a great diversity of amphibians, but the most recent discoveries have been so-called cryptic species, because their appearance closely resembles frog species already known to science. Researchers have been identifying these new species by their genetic differences, using a tool called DNA barcoding, which compares tissue samples to known patterns of genetic markers. The work makes it especially rare for a new frog species to be found in a place that has already been well explored, such as Madagascar’s Andasibe-Mantadia National Park.

Hutter says “G. marokoroko is likely to be an endangered species, because it has only been found in four patches of forest, some of which are threatened by slash-and-burn agriculture”. (Source; www.science.org)

“Methuselah” the Australian lungfish arrived at the Steinhart Aquarium in 1938, her exact age isn’t known, but it’s believed she is at least 90 years old making her the oldest living fish in a zoological setting. Methuselah came to San Francisco on a Matson Liner steamship from Queensland, Australia in 1938. She was already grown, and was believed to be at least 7 years old in 1938.

Methuselah is now about 3.5 feet long and weighs 40 pounds, but is likely to be still growing, as even elderly lungfish continue to grow throughout their life. Lungfish are “living fossils,” which can breathe on land and in water. The lungfish’s evolutionary advantages include the ability to survive in mud until rains return and use their limb-like pectoral fins to shuffle from pond-to-pond.

“They are a very, very primitive fish,” says Senior Biologist Allan Jan, who has worked at Steinhart Aquarium for 15 years, caring for Methuselah most of that time. “They’re kind of the link between fish and amphibians, having a lung to breathe air.” He went on to say “I’ve known about Methuselah since my own childhood in the 1980s, when the fish was already being celebrated for its longevity.”

The Shedd Aquarium in Chicago previously held the title of oldest aquarium fish until their lungfish called “Granddad” died in 2017, after 84 years at the aquarium, since then “Methuselah” became the world’s oldest aquarium fish.

Collated and written by Paul Irven.

Advice issued by Public Health England to prevent the spread of salmonella when working with reptiles. It is important to the hobby that everyone keeps safe when working with frozen foods. Google: “gov.uk reptile salmonella” for details.

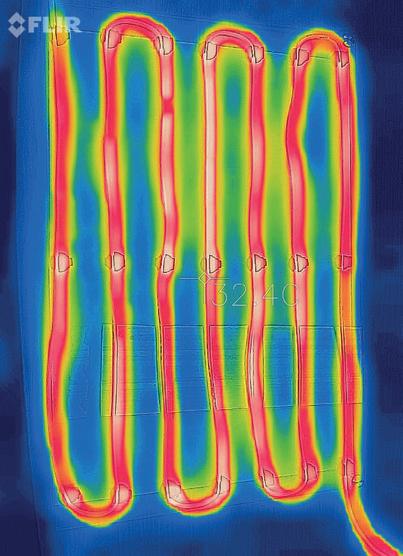

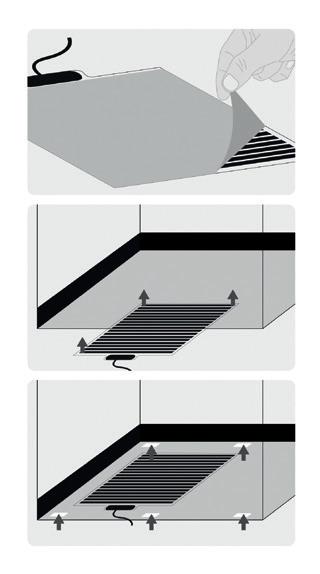

• The unique distribution of heating ink on the surface of the Heat Mat allows for a gradual decrease of temperature towards the edge.

• This greatly reduces the chance of glass bottom vivariums cracking.

• The uniformity of temperature is guaranteed because of the wide heating bands.

• The Heating Mat, unlike other heating systems, allows for a thermal gradient to be achieved.

• In order to benefit from the Heat Mat features we STRONGLY RECOMMEND using a suitable thermostat.

• Ideal for creating necessary warm areas in the terrarium.

• Supports digestion. promotes well-being and activity.

• Suitable as a constant heat source in terrariums.

• Enables night observation of the animals without disrupting the 24 hour cycle.

• Ideal in combination with a suitable thermostat in order to regulate the heat.

• Only use Heat Emitter in a suitable Ceramic Lamp Holder.

• Guarantees regular and even heating along its length.

• Ideal for heating reptiles, amphibians, small animals, and paludariums.

• In aquaria it generates a slow circulation of heat through the substrate.

• Suitable for plant propagation systems.

• In order to benefit from the Heating Cable features we STRONGLY RECOMMEND using a suitable thermostat.

Parthenogenesis in reptiles.

Mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris)

Mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris)

Reptiles are absurd in many ways. Each species has its quirks, and some are so unusual they would be better suited to a comic book saga. Parthenogenesis is certainly one of these quirks. The ability to essentially clone oneself is extremely rare amongst vertebrates, but for some reptiles, it’s just another day.

There is a huge debate in the scientific world around how we should best label the methods of reproducing without a mate. Obligate parthenogenesis is the most straightforward. This method involves an (almost) entirely female population fertilising their own eggs and reproducing by themselves. In some obligate parthenogen species, males may be produced, but usually these males possess abnormal spermatozoa, making them sterile. Naturally, this means entire populations of these animals will share identical genetics, to which the males cannot contribute.

Facultative parthenogenesis is the ability to reproduce in the extended absence of a male and is well-recorded in invertebrates. However, research suggests that there are lots of species across four distinct taxa (reptiles, sharks, birds and invertebrates) which can reproduce without a male. Essentially, they are described as ‘facultative parthenogens’ because although their primary way of reproducing involves a mate, they are still able to produce living offspring or fertile eggs by themselves. However, this is extremely rare, leading some scientists to describe this as ‘accidental parthenogenesis’ on the basis that most individuals within

the species cannot do this. For these species, most eggs are infertile and almost all offspring are sterile. It is therefore not an adaptation for the species, so much as it is an anomaly that has been observed and recorded.

Another key factor in defining parthenogenesis is the methods ability to allow a species to form new populations and inhabit new areas. Of course, obligate parthenogens rely entirely on this method of reproduction, whereas accidental parthenogenic species are unlikely to be able to expand their population much beyond a few individuals.

Unsurprisingly, the natural world has thrown a few curveballs to this formula. A Burmese python raised at Artis Zoo in the Netherlands produced annual clutches of eggs through parthenogenesis between 1997 and 2002, of which 25-30% contained embryos that appeared healthy. Although legislation prohibited the incubation of these eggs, research suggests that up to 7 of the offspring were genetically identical to the mother and to one another, meaning that individual could feasibly be described as parthenogenic. This

has also been observed in green anacondas (Eunectes murinus) at several collections between 2016 and 2019. A Chinese water dragon at the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute also produced several viable clutches. Kyle Miller, Keeper at The Reptile Discovery Centre said “she started laying eggs in 2009, we didn’t start incubating until 2015 and then we just took a chance, thought we would incubate them as it doesn’t hurt anything and we were like wow, very cool.

This species reaches sexual maturity at about 18 months and she was housed with females only after 4 months. That’s how we know there’s a very low chance of sperm storage against parthenogenesis.” After the conservation genomics team ran several tests on all hatchlings it was confirmed they were born through parthenogenesis. The institute is now anticipating further studies on the young dragons to see whether they are capable of reproducing once they reach adulthood.

Who runs the world? Girls!

There are a handful of gecko species that reproduce asexually as obligate parthenogens. The most studied and regularly kept in captivity is the mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris). Almost all mourning geckos on the planet are females and it is widely accepted that this is where they get their names, as those that discovered them (who we can only assume were men) thought they were ‘mourning’ the loss of their male counterparts. In truth, a lack of males and the ability to clone themselves has meant that mourning geckos have a huge distribution across Southeast Asia, Oceania, Central America, Hawaii and the Galapagos. Their origin is likely to be throughout Asia, but some areas have been easily colonised due to the mourning gecko’s saltwater-tolerant eggs.

Some male mourning geckos have been produced but all recorded cases have been infertile. Normally, the female would possess the components to create and fertilise her eggs internally which removes the need to mate. Although, female-female copulation has been observed in mourning geckos.

Naturally, with one individual cloning themselves many times, the genetic diversity of this species is extremely slim. Although they have been able to populate a huge range and thrive in many circumstances, this limited gene pool means that every individual is vulnerable to fluctuations in temperatures, diseases or a mutation that could spread through the entire population very quickly.

Mourning geckos have been popular in the hobby for some time now. With the rise of bioactive setups creating the ideal environment for this species to thrive, mourning geckos present a unique challenge in the world of herpetoculture. A population can quickly outgrow an enclosure and a single escapee can soon colonise neighbouring enclosures before establishing a new population in habitable locations around the home.

Owen Chennery has been keeping and by default, breeding mourning geckos for 8 years. He warns new hobbyists: “The most important thing with mourning geckos and the best way to be responsible with them is to only keep them if you have somewhere to sell them on. They are parthenogenic with two eggs at a time and even though they can take around three to four months to hatch, they just keep churning them out.”

“If someone starts out with a 45 x 45 cube, the reality is they will VERY quickly need to upgrade that. Mine’s 3 foot tall, 2 foot wide and the reality is you probably need the biggest glass tank you can buy. If we’re talking numbers, you probably won’t ever be able to get a tank big enough. I’ve sold over 500 of them over the years and they just keep coming! They won’t stop because of the enclosure size.”

Although breeders will often work tirelessly and for many years to develop a successful breeding colony of animals, mourning geckos flip this completely upside down. Luckily, the demand for mourning geckos is consistent as they do make extremely interesting observation animals.

Owen continued: “Even though they’re a pain, they’re one of my favourite species. They talk to each other by clicking and they have a hierarchy. When I put food out, the big ones will feed first, and they will click at each other and chase one another off etc. Then once they’ve had their fill, the little ones will nip in there and it’s really interesting to watch. That’s why I love them so much. When you put the food in there the whole tank erupts and everyone’s clicking to one another, it’s great in that respect.”

Although mourning geckos have quite achievable captive requirements, their abundance in the hobby, as well as difficulty controlling the population means they should be considered a specialist pet. Owen has kept reptiles for 22 years and been a Sales Manager for Peregrine Livefoods

for 7 years, meaning he has always managed to find an appropriate home for surplus animals. Without this network, novice breeders should seriously consider whether a mourning gecko is right for them.

Owen Chennery added: “The first 12 were given to me by someone who had a little tank and I naively said, ‘yeah sure!’ I thought they were cute. But you do need to be cautious, you can’t make them stop. If the tank’s there and set up, they’re going to breed. I would say make sure the setup is right, everything is ready for them, heating, lighting, humidity etc. I give them UVB and everything they need, but they’re excellent escape artists. When they do get into another tank it’s extremely difficult to remove them. Even though I’m sure I could catch and contain most the geckos, the eggs are still there.”

“There’s a population of mourning geckos that have managed to get into my tricolour dart frog tank. I didn’t put them there, but they have got in. Now, I’m noticing a lot less spawn in there, so I am wondering whether they could be eating them. Tricolours are supposed to be quite prolific breeders, I’ve got the correct ratios and they’re calling loads but I’m not getting tads out of it. I suspect that the geckos are feeding on the spawn. A friend of mine had a tank of mossy frogs and he kept a peacock gecko in there and actually caught it fishing tadpoles out of the water, so it’s a definite possibility.”

Although mourning geckos are the only widely kept parthenogenic species, numerous lizards can reproduce in this way. In fact, it is thought that some 40 species of lizard are obligate parthenogens, including several terrestrial geckos. Whilst it’s unlikely new keepers will stumble across these species, some of these lizards such as whiptails (Aspidoscelis .spp) have been imported in the past.

Interestingly, not all mourning geckos look identical to their mother, despite being a genetical clone. “When they come out, they have patterns and lines, but as an adult they become more uniform” explained Owen “Some are very brown, others retain their markings - they’re very strange animals. I love watching them but I couldn’t tell you which one is which. You often see people online trying to sell morphs of mourning geckos. The truth is if it’s hot you get a lighter gecko, if it’s cold you get a darker gecko, I really think it’s a fallacy that people have these morphs. I mean, how do you get a morph of an animal that’s cloned itself?”

New Mexico whiptail (Aspidoscelis neomexicanus)

New Mexico whiptail (Aspidoscelis neomexicanus)

New examples of parthenogenesis are being discovered every day. There have been several official recordings in the last year, particularly from big snakes.

Scientists are still trying to figure out why some individuals from some species reproduce via facultative parthenogenesis and what that means for conservation.

Every animal, including us, contains potentially detrimental mutations, but these are usually recessive. By passing all mutations on, it can increase mortality rates, meaning reproduction by facultative parthenogenesis may not be such a good thing.

Recently an Asian water dragon (Intellagama lesueurii) produced nine healthy offspring via facultative parthenogenesis. Over the next few years scientists at St Louis Zoo will research the offspring’s reproduction viability. If they can produce healthy offspring, it would be a major breakthrough in understanding parthenogenesis.

Despite facultative parthenogenesis being widely documented in the worlds largest snakes, the only obligate parthenogenic snake we currently know of is actually the world’s smallest snake; the Brahminy blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus). Despite being one of over 420 species belonging to the Typhlopidae family, the Brahminy blind snake is the only parthenogenic species. Exhibiting many parallels with the mourning gecko, the Brahminy blind snake has managed to colonise a huge distribution. Originally from Africa and Asia, this snake can now be found in Australia and many Pacific Islands, Southern Europe, the Caribbean, Mexico and parts of the USA but is thought to only occur in areas where no other blind snakes are found.

Like the mourning gecko, all Brahminy blind snakes are female. Despite looking just like a worm, these animals are reasonably social and will take refuge in small groups. The mother will produce around eight eggs each breeding season, which once hatched, will be fully independent and continue their fossorial habits beneath the soil and leaf litter.

In October 2021 researchers at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance discovered not one, but two extremely rare cases of parthenogenesis in birds, after hatching two condors from unfertilised eggs. Interestingly, this came from a critically endangered species in an established breeding project which had been exposed to males but still chose to produce clone offspring.

The population of California condors (Gymnogyps californianus) reached an all-time low in 1982 when there were just 22 birds left in the wild, these were harvested for captive breeding leading the species to be described as ‘extinct in the wild’. Dedicated breeding programmes have now pushed the number up to around 500 birds, saving the species from extinction. Researchers were required to complete regular DNA analyses of the birds before reintroducing them to the wild to monitor their genetic viability in repopulating their native range of Mexico and the Southwest USA.

In 2021 the researchers discovered that two male chicks hatched in 2001 and 2009 possessed no genetic DNA of a male parent. It was only through routine

If you want a job done properly…Brahminy blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus)

testing that the scientists stumbled across the findings. “This is truly an amazing discovery” said Oliver Ryder, PhD., Kleberg Endowed Director of Conservation Genetics at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, in a statement. “We were not exactly looking for evidence of parthenogenesis, it just hit us in the face. We only confirmed it because of the normal genetic studies we do to prove parentage. Our results showed that both eggs possessed the expected male ZZ sex chromosomes, but all markers were only inherited from their dams, verifying our findings.”

Unfortunately, both chicks, which were only recently discovered to be such miraculous babies, have passed away. Both mothers were housed with fertile males and had previously reproduced sexually with their partners. The first mother had 11 chicks, while the other one had 23. The latter of the two continued to reproduce two more times after the parthenogenesis with her long-term partner of 20 years.

Facultative parthenogenesis in birds was confirmed in the 1960s in turkeys and chickens. Further studies into finches did find that some birds could produce fertile eggs, although these never progressed to the hatchling stage. The fact that an endangered condor can reproduce

Parthenogenesis is an extremely interesting field of research for herpetologists and one which even the most amateur enthusiasts can and should contribute to. It is widely believed that parthenogenesis is much more common than we have officially recorded. Anecdotes from breeders who have produced viable clutches/young from Rhacodactylus spp., Varanus spp. and Python spp. are becoming more widespread. It is also reasonably common for leopard geckos to produce eggs without the presence of a male, which in some cases are viable and fertile (however this is usually the result of sperm retention over a long period of time). Either way, recording the observation and sharing it with others is extremely beneficial to better understanding this subject. Animals that have never been in a mixed-sex enclosure, that still produce viable clutches or live young should be documented at any opportunity. For novice keepers witnessing this phenomenon, speak to your local shop, write to us, or contact a dedicated researcher as it may be extremely beneficial to share this information.

If you want a job done properly…asexually, even in the presence of a fertile male does open the doors for further studies into parthenogenesis. Crested gecko (Correlophus ciliatus)

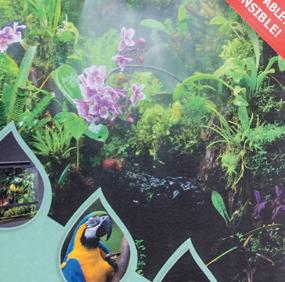

The green cheeked conure is becoming increasingly popular due to its manageable size, affectionate nature and widespread availability. Native to the tropics of South America, the green cheek is one of the smallest of the conures and measures just 25cm in length.

In the wild, this species will generally travel in small flocks of between 10-20 birds. Coming from the dense rainforests and marshy wetlands of Brazil and Bolivia, they will nest very high in the trees and feed primarily on fruits, seeds, buds, blossoms and the occasional insect. These birds generally live between 10 and 15 years in the wild, although some captive green-cheeks have been known to live into their 30s.

As a well-socialised and affectionate bird in the wild, green cheeks can be extremely charismatic pets that will actively develop a bond with their owner. Of course, this also means they are only appropriate for keepers who have a lot of time to dedicate to them and will choose to have

them outside of their cage most the time. This obviously creates mess and requires consistent attention to the animal, but for the right person, the mischievous nature of this parrot is the epitome of what many bird enthusiasts look for in a pet. It also means that green-cheeked conures will generally do very well in pairs. This is absolutely no substitute for training and devoting lots of time to the animal, but it does mitigate some of the risks of keeping other species together.

Conures are notorious for being loud. However, the green cheeked conure is possibly the quietest of all the species. This does not mean they are silent and as with any pet parrot, can be extremely vocal at inappropriate times. Conures are not prized for their ‘talking’ ability, but it has been recorded that this species can learn a handful of words with some training.

There are six subspecies of green cheeked conure, with the most popular species being P. molinae australis Having been well-established in the aviculture hobby for some years now, various colour morphs are available too including ‘pineapple’, ‘cinnamon’ and ‘turquoise’.

The importance of carotenes in flamingo diets.

Greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus)

Greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus)

Flamingos are some of the most iconic birds on our planet. Cemented in pop culture for their peculiar shape and vibrant colouration, the story of how flamingos turn pink is widely understood but in little depth. Ask most people and their response will most likely be “their food” but how does their blue/grey food turn the flamingo pink?

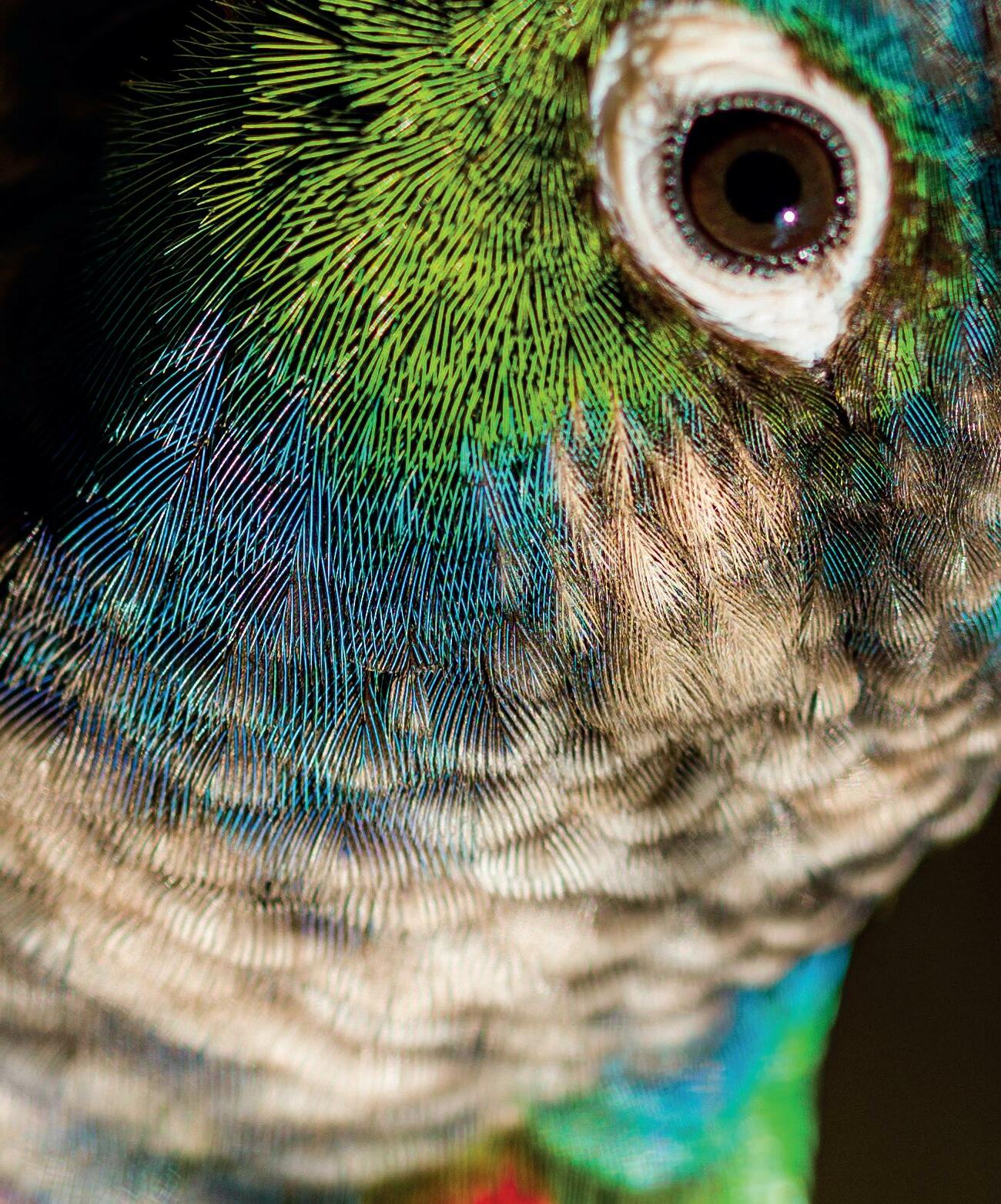

The colour of a bird is generally made up from three separate types of pigment. Firstly, carotenoids are produced by plants which provide orange pigments. This may translate to reds and yellows (in the case of flamingos, scarlet ibis, warblers and goldfinch). Secondly, melanin which occurs as tiny granules of colour and produces darker, stronger feathers (which is why many birds will have their darkest plumage at the extremities of their wings). Finally, porphyrins which are produced by amino acids and can fluoresce when exposed to UV. Porphyrins are found in a good number of species and appear as a whole spectrum of colours, most notably in the brilliant greens and reds of turacos (Tauraco sp.). Of course, these categories can combine and overlap in marvellous ways. ‘Structural colours’ such as iridescent and non-iridescent feathers also create interesting visual patterns, giving birds some of the most diverse colours on the planet. Furthermore, their UV reflecting feathers and wider visual spectrum means that they will appear even more diverse to one another than to the human eye.

Carotenoids also play a much bigger part in the lives

and natural history of birds, far beyond their colouration. Elisabetta Mancinelli (DVM CertZooMed ECZM Dipl), European Veterinary Specialist in Zoological Medicine told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “Carotenoids are naturally occurring pigments synthesised by many plants, amongst other things. These richly coloured molecules are the sources of the yellow, orange, and red colours of many of these plants. These carotenoids are the Vitamin A precursors and are converted in the bird’s body into Vitamin A. Carotenoids are beneficial antioxidants that can protect from disease and enhance a bird’s immune system. It is important for Provitamin A carotenoids to be converted into vitamin A, as this is essential for a number of functions within the body including growth, immune system function, eye and respiratory tract health. Deficiency can result in significant systemic disease.”

For species which develop their colouration through carotenoids, it is widely agreed that this helps the continuation of the strongest animals. Vibrant colour displays, supported by a carotenoid-rich diet means that some of the healthiest animals are generally first

in line when it comes to mating. There is much debate over how this materialises in individual species but provides good insight into the importance of diet for wild birds and guides captive breeding projects towards much greater success rates. In fact, it has been observed that some species will exhibit hostility towards a cage mate if their plumage looks dishevelled because of poor nutrition such as a lack of carotenoids. It is assumed this hostility would prevent disease transfer in wild populations.

Flamingos are sift-feeders meaning they will sift through the mud with their huge upside-down beaks to pick off a wide range of algae, molluscs, and crustaceans. The algae and shrimp are extremely high in carotenoids but are strangely not pink themselves. This is because the pigments start out as parts of other compounds such as astaxanthin, which is attached to other proteins. These proteins do not reflect the red part of the light spectrum and instead will reflect blue.

When the flamingo digests these proteins, they are broken down and detached from the pigments. After a few years of consuming these detached pigments, the build-up of carotenoid-filled fats in the growing feathers of the flamingo start to exhibit the bird’s classic pink colouration. The same process happens when we boil lobsters or shrimps, and they turn from blue to red.

There are six species of flamingo and all exhibit striking colouration, though the Caribbean flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) is the brightest. Other species vary drastically from almost entirely white to a vibrant orange, which will also change depending on the time of year. Interestingly, it isn’t just flamingos that get their colouration this way. Many vibrant pink birds such as the scarlet ibis (Eudocemus ruber) get their brilliant colouration from a similar process, feeding on small crustaceans but also insects and small vertebrates.

Jamie Graham, Bird Expert at ZSL Whipsnade Zoo said: “We use a high-grade pelleted feed that has the right amount of carotenoids in it to supplement their diet. However, there are other considerations to feeding flamingos in zoos and similar environments. Namely, they require a large body of water that is not changed regularly. This is because the flamingos will constantly filter feed from the water, any algae they feel like. They especially like the strong blue green algae that occurs

of years, despite coming from extremely different environments. By giving the chicks the best opportunity to grow as quickly as possible, they mitigate some of the danger posed by their harsh habitats.

There are numerous crop milk formulas available for handrearing pigeons and some specialist flamingo formulas too. Jamie continued: “We have never used a commercial crop milk, we let the parents feed the chicks as a rule. However, if we had to hand-rear in the past then we have made our own feed up. It’s always better to let the parents rear any chick, if possible, for dietary reasons but also behaviourally.”

The crop milk produced by flamingos has prompted some truly horrifying photographs to circulate the internet. This is because the milk can sometimes appear red and to the unknowing social media scroller, look just like blood. A viral video in 2015 showing one flamingo covered in red

and another leaning ominously above it led to widespread rumours that these birds were cannibalistic, which could not be further from the truth.

Whilst most of us are unlikely to ever keep a flamingo, the same necessity of ensuring birds receive all their vitamins and minerals applies to parrots too. Across most species of commonly kept birds, it is generally possible to spot a deficiency in vitamin A which can occur when not enough carotenoids are provided in a diet. Elisabetta continued: “Poor feather quality, including damaged feathers and poor colouration, are often evident signs that a bird is vitamin A deficient. Other common signs of vitamin A deficiency in parrots are nonspecific and may include blunted choanal papillae, salivary gland abscesses, poor feather quality, decreased reproduction rates, and increased risk of illness.”

In the world of aviculture, keepers are quickly turning towards a pelleted diet to ensure that their birds get all the nutrients they require. This usually eliminates the need for a supplement. However, transitioning onto a complete diet can be difficult and bird keepers who still provide their animals with seed should seriously consider supplementing food in much the same way reptile keepers do.

Elisabetta concluded: “Nutritional analysis has shown that seeds and nuts, often fed to captive parrots are deficient in many of the essential nutrients, including Vitamin A, and are in general too rich in fat. Therefore, Vitamin A deficiency has been commonly associated with a predominantly seed-based diet in parrots. The need for specific vitamin A levels likely varies between species as different species of parrots have evolved different nutritional strategies. For example, Amazon and Eclectus parrots’ diet should contain more fruit and vegetables than that of the more omnivorous Grey parrots.”

“Many parrot owners supply mineral and vitamin supplements. The use of supplements, including ACE-High (Vetark@), specifically formulated to provide high levels of vitamins A, C & E, may help correct some of the known shortfalls of a seed-based diet. However, clinical nutritional disease may still occur. Therefore, conversion from a seed to a formulated diet should be implemented to achieve a more balanced diet. Nevertheless, this process is often difficult and whilst some birds convert readily, some do take longer to change their usual eating habits. Adequate supplementation should be provided in the meantime, to support the bird’s health.”

Providing a complete nutritional profile is a universal requirement for keeping any animal. Whilst our domestic pets may be less fussy in their dietary requirements, exotic pets, regardless of taxa, require a bit more research. As we move towards more complete and nutrient-rich diets it is important to highlight any short falls and always provide the appropriate supplements.

Can we cohabitate small vertebrates successfully and more importantly, should we?

Cohabiting species in the same enclosures has been happening in zoos since the 19th Century. It is, however, a practice more widely debated in exotics keeping. Although it is much more accepted and arguably holds more benefits in a zoo setting, the rise of bioactive enclosures is allowing private keepers to create geographically sound exhibits that can effectively house a variety of taxa. However, establishing a dynamic that is comfortable, even beneficial to all residents can prove to be extremely challenging.

The cohabitation of species in a zoo environment is certainly the most widely accepted way we see dynamics between separate species in captivity. Offering fresh insight into the geographical ranges of flagship species, the cohabitation of taxa not only allows young people to become inspired and envisage exotic locations but gives leading experts insight into the natural behaviours of certain species. Amy Armitage, Deputy Zoo Manager at Ponderosa Zoo: “We have multiple enclosures with animals housed together including Cuvier’s Dwarf Caiman and Arrau River Turtle, Black Spiny-tailed Iguanas and Red-footed Tortoises, Pancake Tortoises and Uromastyx, Madagascan Hissing Cockroaches and Madagascan Tree Boas. Each animal’s individual needs were considered when structuring their enclosures including substrates, diet, shelter, and natural behaviours.”

“From an educational point of view, it is a good thing to cohabit different species as we can educate the public that some species rely on each other for food, shelter, and protection. It also gives the public a more

interactive experience. From a zoo perspective, it mimics the animal’s natural environment and influences natural behaviours and allows for a higher level of activity. There are limitations on cohabitation but ensuring that there is enough space in the exhibit is very important to prevent stress to animals.”

A paper from the BIAZA Research Committee published in the Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research 9(3) 2021 looks at the impact of ‘immersive exhibits’ at Chester Zoo and states: “Modern zoos place great importance on their role in improving the ‘biodiversity literacy’ of the general public, and references to education are near-ubiquitous in zoo mission statements, particularly in the Englishspeaking western world… Worldwide, zoos receive approximately 700 million visits annually, representing diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, baseline knowledge and visit agendas. Therefore, zoos have considerable potential as centres of conservation education.”

The study was conducted to identify the potential of a multi-taxa exhibit called ‘Grasslands’. It concluded that

immersive exhibits had a much greater impact on visitor education, despite them on average spending less time there. Previous research conducted by Andrew Balmford at London Zoo also found no discernible difference between the time visitors spent at large-bodied animal exhibits when compared with small-bodied animal exhibits. Creating an immersive exhibit generally involves the provision of resources outside of the enclosure, such as resin hardscape, interactive screens, and geographical pointers (such as safari huts, or artificial plants). However, creating this on a smaller scale can sometimes prove challenging, which is where mixed taxa exhibit help educate visitors on geographical locations and habitats.

Amy continued: “While zoos are a more

ideal place to cohabit due to the ability for more constant monitoring and management, it should not be restricted to just zoos. Private keepers can be just as capable at extensive research as some zoos. As previously stated, there can be behavioural benefits that private keepers can take advantage of. With a variety of species in an exhibit, activity levels are increased.”

“Often utilising at least one terrestrial species and one arboreal species works well, tortoises being excellent for mixing with other reptiles, namely lizards. Primates from the same geographical range works well such as different species of lemur or different callitrichids. Docile herbivorous animals are also well suited, such as hoofstock or the commonly seen mara/ agouti/capybara mix.”

This process always needs to be conducted with an impeccable level of knowledge and selecting the correct species is crucial to success. Eleanor Tritsana-Chubb from Tortoise Welfare UK and European Lead at Turtle Survival Alliance told us: “You’ll often hear that it’s okay to house species from the same geographical area together, but even this isn’t a fool proof method. Arboreal snakes from Madagascar can require much more humidity than tortoises from that region, and so, housing these together will eventually create issues. Similarly, keeping birds with tortoises from the same region will inevitably result in disease transmission as bird faeces gets into the tortoises’ habitat. In all but the most enormous enclosures you’ll certainly experience this problem.”

Zoos tend to have more resources than private keepers, but this does not prevent the private keeper from accessing and creating the same custom-built zoological enclosures we see in many highly regarded establishments. From a practical perspective, nothing is off-limits to a private keeper however the general strains of work commitments, life changes and even holidays can mean that vital observation required to house animals correctly can be compromised as the entire collection is managed by one individual (and potentially a handful of friends and family).

Gareth O’Dare, Senior Keeper at Newquay Zoo explained: “Large enclosures enable us to create numerous microhabitats which allows different species to live alongside each other without coming into much contact. We also make sure we provide plenty of opportunities for animals to utilise the resources they need, including heat, light, shade, shelter, nesting and feeding opportunities. Competition and aggression are the most common issues in cohabited enclosures, but it’s not something we’ve seen in the large set-ups we have built.”

“One of my favourite cohabited enclosures is a paludarium containing Red Tailed Racers. I’d looked at the mangroveswamp habitats these animals frequent in the wild and worked to recreate this as closely as possible. Although we pulled back on the idea of using brackish water, the tropical fish we have in the bottom of the enclosure are doing very well, and we often see them picking at the scales of the snakes as they lie submerged half in and half out of the water.”

The increase in popularity of bioactive set ups have normalised the cohabitation of species to some degree. Every bioactive set up requires a clean-up crew, which is in itself, cohabitation. This could go further as various

plants are selected to fulfil an ecological niche or purpose, regardless of the species’ relationship to the animals housed. For example, there are around 2000 species of bromeliad. Sourcing the exact one that a particular locale of a subspecies of dart frog would encounter in their wild range would prove extremely difficult. Some horticulturists are now seeing the potential in collecting certain flora to match popular fauna, but to create an enclosure that is perfect not only requires a deep understanding of plants, but a strong connection to plant collecting circles, fairs, and meet-ups. Therefore, the majority of herpetoculturists tend to base their knowledge of cohabiting species on broader ranges and ecological niches rather than geographical accuracy.

Dave Perry, Director of REPTA (Reptile and Exotic Pet Trade Association) added: “In the wild, reptiles will inevitably cohabit. They will also eat each other. This means cohabiting in captivity needs some careful consideration. A lot of thought must go into the construction of a cohabited enclosure. There is a lot to consider – cannibalism and disease transmission to stress from competition, optimum heating, lighting and shelter opportunities, along with the stresses of mating, aggressive feeders and other such competition. The wild is vast and animals have at least the opportunity to escape these issues to some degree, but the potential for these to become a problem is far more likely in a captive environment.”

“The knowledge necessary to mitigate these is something only an experienced keeper would possess. Species chosen to cohabit must be from the same environment and have similar needs, but also occupy slightly different niches in the environment to avoid excessive competition. For example, Anolis, Rough Green Snakes and Green Tree Frogs can be housed together and are spatially separated by both their slightly different environmental needs (bright basking zone vs thick foliage for example), and their behaviour (nocturnal vs diurnal).”

As with all aspects of reptile husbandry, product development combined with in-situ research is giving us more and more success. Private keepers have access to a wealth of products and even some reasonably large vivaria directly through their local shop. Of course, custom-made enclosures can offer more space for their residents and allows builders to add visual barriers, integrated hides, tunnel networks, specially designed ventilation and feeding hatches which can all make co-habitation that bit easier.

Some of the most popular species to cohabit in the herpetoculture hobby is dart frogs and day geckos. Despite being geographically disparate, diurnal, terrestrial dart frogs clearly fill opposing niches to arboreal, nocturnal day geckos. However, even these can have complications as more and more people are reporting geckos opportunistically feeding on tadpoles of various frog species.

One major concern for cohabiting different species is the potential for disease spread. Zoos will have their own team of dedicated veterinarians that will typically have a good grasp on quarantine procedures as well as the ability to quickly identify and isolate animals who may be showing ill-health. For many private keepers, even the most experienced in the hobby, routine medical inspections of animals are not the norm. This means harmful pathogens can spread through a collection quicker.

Tariq Abou-Zahr is an Exotics

Veterinarian who keeps various birds and reptiles as a private hobbyist too. He explains: “From a veterinary point of view, there are potential disease complications associated with keeping different species in the same enclosure. While there are many examples, a few include the following: Entamoeba invadens is a micro-organism which causes disease in reptiles. It can affect many species, including snakes, lizards and chelonia. Some can carry this parasite without showing clinical signs, while others become severely infected and may die as a result. Carnivorous reptiles tend to be far more susceptible,

while herbivores rarely show signs of disease with Entamoeba. Tortoises may carry a heavy burden with no issues at all, but if those tortoises are kept with lizards or snakes, the tortoises can be asymptomatic carriers and act as a vehicle for severe disease in the cohabited species. Even among snake species, some North American colubrids show an inherent resilience to this micro-organism, while others may develop severe disease.”

“Arenavirus is a pathogen of snakes thought to cause the neuro-respiratory condition called ‘inclusion body disease’ (IBD). It primarily affects boas and pythons. Some boas will show a very gradual disease process, while others will never show signs of disease but act as carriers or shedders. Pythons seem to be far more sensitive to infection with this virus, often deteriorating more

suddenly and acutely. Given that most snakes are never tested for this virus, and that studies have shown that around a third of boa constrictors in the UK are carriers, if someone were to keep boas and pythons together there is a substantial risk of transmission and disease. This is a well-known example, but there are many other viruses that behave in a similar way. For example, Herpes virus is extremely common in tortoises. There are differences between species in terms of susceptibility to this virus, meaning that housing animals together could lead to the spread of this disease from one species to the other.”

“Keepers considering cohabiting reptiles should ideally have a discussion with their exotic animal veterinary surgeon about the risks of disease and parasitic transmission. Testing for these risks is also a good idea.”

One prevailing argument for cohabiting species is the environmental enrichment they receive, which may prove beneficial to some species. As we learn more about the social dynamics of reptiles and amphibians, we are starting to understand how encountering other animals in the wild promotes certain behaviours that are otherwise absent from captivity. Whilst previously thought to induce significant and unnecessary stress on almost all animals, the ability to recreate a holistic slice of rainforest opens many doors for cohabiting species.

Dave Perry added: “One aspect that is becoming more important to keepers is the need for enrichment in captive reptiles. While nobody would suggest that housing predator and prey species together would be acceptable as a source of enrichment, contact with other, compatible, individuals certainly does provide stimulation. Indeed, many reptiles are now known to live in colonies and even recognise individuals and family members, so contact is an enrichment event which many reptiles experience in the wild.”

probably does not have a negative impact, keeping them together could be considered another form of enrichment.”

“Psammophiine snakes for example take this socialisation further than people would think. They have narial valves beneath the eye which they use to mark out their territory by rubbing on landmarks, and also self-anoint by polishing their vents and flanks so that the pheromones rub off as they patrol their territories to delineate its boundaries. I have witnessed two different species of Psammophis ‘anointing’ other specimens kept together in this way. Further, at least some Psammophiine snakes take socialisation a step further. Pairs may bond for extended periods. Males capture prey which they present to females. Females seek out their male and squeeze beneathhim when threatened from above. Males will retain a territory and press-gang defeated rival males into becoming ‘vassals’ and helping him defend his territory and female from other interlopers. These behaviours are not the actions of asocial animals.”

it is done purely for financial reasons – keeping two snakes in an enclosure that is too small just to save on space, electricity or equipment – that cannot be recommended. But with a bit of thought and care cohabiting can provide an extra facet to these animals’ lives and offer many interesting insights to the observant keeper.”

Whether someone should cohabit their animals is generally answered by another question, why are you considering cohabiting your animals? Clearly there are huge benefits and potentially grave problems when it comes to cohabiting different species in captivity. For establishments such as zoos with a clear educational agenda, the benefits of cohabiting species may outweigh the negatives. For private keepers studying and documenting their animal’s behaviour as research to share with other keepers, the benefits may, again, outweigh the potential risks. Those with unlimited resources will naturally encounter less challenges than those working within the parameters of a budget or a commercial enclosure size.

Francis Cosquieri is a professional reptile keeper, who has managed hundreds of species over many years. Despite him recognising that there are lots of major challenges and considerations when cohabiting any species, he has managed to cohab various snakes successfully, adding: “Despite ‘common knowledge’ indicating that snakes are not social and do not react to one another, this is actually far from the case. Many species do socialise to varying extents to the point that, while keeping them alone

“There is also the fact that snakes do in fact have various ways of signalling one another. These are sometimes subtle, sometimes not. I have watched Thrasops and Coelognathus ‘wave’ at one another from different vivaria across the room by performing anterior undulations, with the other animal responding. We simply do not know how much sociality affects these animals – not enough to appreciate that a lack of it could affect their husbandry in any way.”

Shingleback skink (Tiliqua rugosa)

“Ultimately, it is for each of us to decide whether to cohabit snakes. If

Amy concluded: “Always attempt to find someone else who has successfully cohabited the same species you want to cohabit and get as much information from them about what they found worked, as all species will be different. From the start the behaviour of both species should be carefully monitored, even if the species could be considered “docile” it still has the potential to turn on its enclosure-mate. Always provide the full needs for both species, and try not to overlap their needs.”

Unpicking the monogamous relationships of the shingleback skink.

Tiliqua rugosa is a unique species of skink with many common names. Bobtails, shinglebacks, sleepy lizards, and pinecone skinks are just some of the very appropriate names used to identify this robust, slow-moving reptile. Shinglebacks are rarely kept in captivity outside of Australia and even less frequently bred. They share many traits with their bluetongue cousins, not least their defensive posture and iconic tongue. However, shinglebacks also display complex courtship routines, with one subspecies Tiliqua rugosa asper returning to the same partner each year for up to 20 years – making it one of the only truly monogamous reptiles on the planet.

With a range that stretches across most of the southern half of Australia, there are currently four recognised subspecies of T. rugosa, the Eastern, Western, Sharkbay and Rottnest Island shinglebacks. They are widely adapted to inhabit a range of environments including semi-arid shrublands, eucalypt forests, desert grasslands and even sandy dunes. Being slow-moving, and inhabiting some of the cooler regions of Australia, they are often seen crossing and basking on warm roads early in the morning. Adapted for defence, rather than evasion, these armoured lizards can stroll up to 500 meters a day, eating almost anything that crosses their path. An omnivorous diet comprised mostly of vegetation with some molluscs, insects and carrion keep these large lizards moving. They have also been reported to eat human foods such as sausages, processed chicken, and various non-native fruits.

Each year in early spring (September/October) these lizards are most active. The warmer weather prompts the shingleback to begin searching for a mate and in the case of the Eastern shingleback (Tiliqua rugosa asper) their long-term partner.

In the world of zoology, there are several facets to the concept of ‘monogamy’. While society tells us monogamy is having a single partner for the rest of our lives, it is slightly different for animals. Social monogamy assumes a close association of a pair of animals that involves cooperation in breeding activities. It does not imply sexual monogamy, as many species of birds will mate with several partners despite raising a chick in one ‘monogamous’ relationship. Most seemingly monogamous relationships in lizards are the result of the male ‘defending’ his chosen female or females and is thus not strictly ‘social monogamy’.

C. Michael Bull writes: “Territorial behaviour in lizards can sometimes lead to monogamy. In some lizard species, some males defend an area occupied by a single female. This may be because one female home range is as large an area as the male can defend. Stamps (1983) suggested monogamy was more common in large than in small lizards. Males can defend the relatively small area occupied by several females in a small species, but not the larger areas occupied by

several females of larger species. Alternatively, in lizard populations where there are polygynous males with high quality territories, some other males may become monogamous if their poorer territories attract fewer females. In two species of agamid lizards of the genus Stellio, some single males defend up to four females while others defend just one.”

Although lizard monogamy is extremely rare, researchers have good reason to believe there is still a lot left to learn. Anecdotal studies of Chameleo hoehnelii suggests that partners will return to one another in successive years, Anolis spp. present extremely complex social relations we’re yet to fully understand and Southern snow skinks (Niveoscincus microlepidotus) will form pairs for up to a month

before breeding. Figuring out animal behaviours, particularly in species that are not readily bred in captivity can prove to be extremely challenging. However, researchers in Australia have managed to work extensively with the ‘sleepy’ lizard, tracking these slowmoving and large lizards with relative ease to paint the first full picture of a monogamous lizard.

Although we have a pretty good picture of the social dynamic of Eastern shinglebacks, scientists are still not 100% sure why they are monogamous. In fact, researchers believe that this relationship could have both positive and negative impacts on the survival of the species. Bull writes “we can speculate that

there would be relatively low cost in locating and pairing with a new partner each year, because all lizards are effectively unpaired at the beginning of the season. Indeed, there may be real reproductive benefits in swapping partners because not all females reproduce every year.” This is puzzling, as Eastern shingleback males will still follow their partner female, each year, whether she does or does not reproduce. Whilst this may sound romantic, it is difficult to make sense of.

Another theory that touches on romanticism is the concept of having a reliable partner. Knowing that a partner will generally reproduce strong offspring or possess traits that may be passed onto the young will offset the years that the partner does not reproduce at all.

Bull added: “Familiarity with a partner may be an advantage of long-term pair fidelity. Familiar partners may be more efficient at feeding, or at detecting predators. They also may be reproductively more efficient. Young are born in autumn and have little time to forage for their own food before the winter, when they must rely on stored energy reserves. Early next spring, six-month-old young weigh little more than at birth. Mortality of juveniles in their first winter is very high. If females could mate earlier, young could be born earlier, or larger, giving them a greater opportunity to survive the winter.”

The shingleback’s unique protective scales, whilst visually stunning, also manage to harbour ticks and parasites quite easily. Ectoparasitic ticks are vectors of the blood parasite Hemolivia mariae. Bull continues: “Another possible function of long-term monogamy could be to prevent the spread of parasites and diseases. It may be advantageous for an individual lizard to remain with the same partner if it did not get infected in the previous year, and if other potential partners may be more infectious.” Whilst studies into the courtship rituals of the Eastern shingleback are widely documented but still inconclusive, observations of other shingleback species are fuelling yet more confusion.

Tristen Pace is an experienced breeder of T. rugosa rugosa, the Western shingleback. He told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “Whilst monogamy has been shown in some excellent and truly amazing studies performed on wild populations of Tiliqua rugosa aspera, and while it likely does occur, to my knowledge this behaviour has not yet been proven in other subspecies.”

“It is certainly not the norm in captive breeding, where one male can cover several females in a single season. I can only assume that the bonding process that occurs over several weeks both in the wild and in captivity, helps to prove that a male partner is a worthy mate. Given the substantial

Tristen started breeding shingleback skinks in captivity over 20 years ago. Living in Western Australia, he has a unique opportunity to breed these lizards outdoors, giving us a rare glimpse at how they can be bred successfully. Tristen continued: “In the wild here in WA, you start to see pairing behaviour from around early September, and this continues to early November. Some population densities are extremely high, and it is not unusual to see several males following a single female. This is usually a very ordered and polite process with the female at the front then several males following in single file as she goes about her daily business. Males seem to be attracted to movement and I have not seen any males continue to stay next to the body of his mate after she is deceased, as reported in aspera (Eastern shingleback).”

Tristen set up his breeding project Goldfields Rugosa 12 years ago with a desire to line-breed visually stunning skinks from the goldfield region of Western Australia. Tristen continued: “I had been living in Perth for a few years by that stage and whilst I loved seeing and photographing our local shinglebacks, it was only after seeing photos of animals from the goldfields region of Western Australia, that I gave consideration to keeping them.”

“Shinglebacks are maybe not the best choice for line breeding at first glance, by virtue of being more challenging than most reptiles to breed, being slow to reach maturity and having frustratingly small litter sizes. However, the extreme natural variation of colours did provide some important advantages. Whilst most shinglebacks from the goldfields are mainly black, with varying amounts of orange/red and white markings, there are animals that are a more extreme orange in colour that make up maybe 1% of the wild population. It is these animals that formed the focus of my breeding project.”

Despite not being strictly monogamous like their Eastern cousins, pairing Western shinglebacks together for a successful breeding season demands some care and attention. As a notoriously picky species, Tristen is required to search for clues for a compatible match. “The choice between them comes down, in part, to the individual personalities and characteristics of the animals being bred” explained Tristen. “I find both male and female shinglebacks to have a wide range of personalities when it comes to breeding, with some being much more aggressive and some much meeker. My best breeder males are generally the largest and most dominant without being overly aggressive. These males I will pair with up to 5 females in a group for the entire breeding season.”

“For males that are younger or a bit meeker, I generally pair them in groups of 2 males with multiple females and select females that are a bit smaller and less likely to be aggressive. I found the addition of the second male provides some competition and seems to spur on interest in breeding, however care must be taken to observe for signs of hostility as fighting can lead to serious injuries.”

“The males will follow the females for about 7-8 weeks from the start of September, however actual mating does not take place usually until mid-October. Mating usually takes place in the early morning and males will test bite females to see if they are receptive. The females will also give the males cues that they are ready to mate, through posture and movements.”

“Females will at times show interesting behaviours and can even act “male”, by following both other females and males, simulating mating, and showing increased aggression and even fighting with males. This tends to

happen around certain times (e.g. ovulation) and is more likely with females that are unmated, or when paired with a male who is a poor breeder or less dominant. Dominant or hormonal males can also at times simulate mating with other less dominant males (although more often these attempts lead to fighting). Unfortunately, I have seen this lead to confusion in more than one keeper as why their shinglebacks will not breed over many years, despite being sure they have a pair after witnessing mating activity, only for them to turn out to in fact be 2 females.”

In Europe, providing everything required to ensure a healthy breeding pair of shinglebacks can be notoriously difficult. Furthermore, certain locales and subspecies are under increasing pressure from illegal harvesting and export. The provision of an outdoor enclosure, natural plants, lots of space and essentially perfect UVI readings means that maintaining reptiles in their native range is undeniably the most successful way of providing good husbandry and receiving good breeding success. Tristen continued: “My adults are kept outside for the majority of the year in pens that are essentially garden beds with glass fencing around them, except for around 6-8 weeks when I bring them inside for brumation in mid-winter. I find keeping outside provides more space and improves breeding success and improves colouring (the intensity of the reds in particular).”

“I raise the babies inside generally for the first year of life as this gives more consistent results. They are fed a diet that consists of about 60% fruit and vegetables, with the other 40% being a protein source such as wet dog food. I supplement the baby’s diet with calcium and vitamin D. Whilst a diet that is higher in protein can give increased growth and improved weight gain, I find it causes an increase in darker pigments and overall duller colouration. As they eat grains as part of their natural diet, I do not worry about feeding any grain-free foods.”

The Eastern shingleback (Tiliqua rugosa aspera) is the only truly ‘socially monogamous’ lizard. Researchers have recorded individuals returning to their mate for up to 20 consecutive years. Other researchers have even observed male Eastern shinglebacks spending days alongside their partners after they have deceased. Whilst the true intricacies of why they do this are unknown, it is possibly the closest example to lizard ‘love’ that herpetologists have discovered yet. In fact, other subspecies of the shingleback lizard are largely movement-driven and will soon lose interest in a female without some chasing, making the Eastern shingleback even more of a mystery!

More than 90% of Australia’s reptile species exist no where else on earth. Yet, between 2018 and 2019, 90% of all wild animals seized by authorities in Australia were reptiles, according to data from the Australian Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment. Unfortunately, shinglebacks fall into this category and new data published by Monitor Conservation Research Society suggests over 500 individuals were intercepted in the last decade.

The new research is aimed to impose tighter CITES regulations on otherwise common species. Because shinglebacks are easy to capture, reasonably abundant and regularly found in breeding

pairs, they are the target of many poaching efforts. T. rugosa konowi on Rottnest Island is famed for its speckled appearance and smaller size and has now been officially listed as ‘threatened’. The population of T. rugosa rugosa from the Goldfields is also becoming increasingly popular amongst smugglers. This emphasises the important work that Tristen is doing to ensure a good number of captive bred animals.

Tristen explained: “Using captive bred stock is by far and away the most important single factor you can have in breeding success. This is probably even more important for those who are overseas. Shinglebacks also require plenty of space (I would suggest a minimum of 1m2 per animal) along with plenty of privacy

if you want them to breed. Conditions also need to be consistent. Shinglebacks are creatures of habit. It can take several seasons for them to feel comfortable in a new environment.” All these factors mean that illegally harvested individuals will generally make terrible breeding animals. It also highlights the difficulties that anyone overseas might encounter when keeping or breeding shinglebacks, so serious consideration is needed when sourcing these lizards.

Despite the species being abundant across most its range, by giving birth to (usually) just two offspring, it amplifies the genetic and ecological importance of the individual. The study previously outlined by Bull states: “Another explanation for long-term fidelity may be that partners are more compatible to each other genetically than they are to other potential partners living nearby… Females in this sample were significantly less related to their male partners than they were to the other males that overlapped their home ranges. The monogamous pair should produce offspring that are more outbred than if the pairing had been at random. An implication is that lizards

in the population can recognise and discriminate against related individuals.”

By impacting the genetic diversity of a localised population just slightly, it can have drastic effects on certain species. Furthermore, common species with high price-tags prompt poachers to harvest much rarer species to fill their illegal shipment. There are of course arguments for legalising the export of all animals to ensure correct paperwork and managed quotas are met. Australia’s generally strict policing of wildlife trade has caused a lot of illicit trade to satisfy global demands. However, some of the hobby’s most-loved species come from this nation and would have almost certainly been illegally traded at some point. It is down to the consumer to do everything in their power to ensure that a species which obviously comes from a nation in which exports are illegal, has been captive bred. Blue-tongue skinks can make wonderful pets and have been popular for decades, but only a few varieties are regularly captive bred in the UK, namely T. gigas (Indonesian blue-tongue) and T. scincoides (Common blue tongue – of which, the Northern and Indonesian varieties are most widely bred).

Tiliqua rugosa aspera – The Eastern shingleback. “These are in general larger and stockier than other subspecies. They have larger and more prominently keeled scales. Colours are darker, consisting of mainly black/browns, with varying amounts of white, tan or yellow patterning.”

Tiliqua rugosa rugosa – The Western shingleback. “By far the most variable subspecies in terms of colour. Generally slimmer with longer and less bulbous scales than the eastern subspecies. Scales are smoother and often quite glossy. The heads are usually lighter and brighter, with patterns along the body that can consist of clearly defined bands, to spots and speckles. There are several recognised colour variations in the hobby, loosely based on their geographical range.”

Coastal forms – “can be found in sandy dunes and coastal heath from north of Perth, extending all the way as far as Esperance. These are generally lighter in appearance with a base colour of white or grey, with varying amounts of brown, tan, yellows and orange.”

Hills form – “Similar in appearance to some coastals, but generally deeper/richer shades of brown, tans and oranges.”

Goldfields – “Larger and stockier, with often very glossy scales. Colours consist of varying amounts of orange, red, black and white. Most wild individuals are mainly black, with orange heads and small amounts of orange spotting or stripes along the body and tail, however as mentioned above, in a small number of individuals (maybe 1% of the wild population) the orange dominates with much reduced black and white patterning.”

Wheatbelt – “Mainly dull browns with dull orange to tan heads and markings along the body.”

Northern coastal – “Less oranges than the southern coastal forms, with a base of white/cream with varying amounts of greys and brown patterning. In some forms the base colour can take on a greenish hue, and these are often mislabelled by smugglers as the Rottnest subspecies.”

Geraldton/Murchison – “Much darker, with a base of blacks and dark brown, with smaller amounts of white/cream markings. In many overseas collections (including much of Europe) these are incorrectly labelled as T. rugosa palarra.”

Tiliqua rugosa palarra - the Shark Bay shingleback. “Generally dark in appearance with varying amounts of white and cream patterning. Heads are often dark and similar in colour to the body. Scales are smaller. Heads are shorter with more pointed noses. Tails also shorter and more pointed.”

Tiliqua rugosa konowi – The Rottnest Island shingleback. “By far the smallest subspecies. Base colouring greenish grey with overlying patterning of darker greys. Range restricted to Rottnest Island off Perth. Listed as vulnerable to extinction, with poaching from the wild for the pet trade being a major threat.”

Reptiles are ectothermic. This means they cannot regulate their body temperature internally. Therefore, they must use the environment around them to warm up and cool down. This is ultimately what determines the natural distribution of reptiles (and amphibians), and why their diversity is at its height around the equatorial tropics.

All physiological processes in their bodies depend on this temperature regulation, stemming from rates of oxygen consumption. The hypothalamus in the brain acts as the internal ‘thermostat’ that prompts reptiles to seek warmer or cooler areas to regulate their temperature back to their natural “set-point”.

In the world of reptiles, the sun provides all heat and light radiation needed for their physiological activity. Estimations vary, but around 50% of the sun’s radiation is infra-red, 40% is visible light, and the remaining percent is UV rays.

The radiation that provides heat, infrared, is also grouped in three ways, depending on the penetrative quality. They are named far-infrared (IRC), mid-infrared (IRB) and nearinfrared (IRA). A good example of each is standing in direct sunlight on a summer’s day (IRA) compared to standing near a radiator on a winter’s night (IRC) and how those heat sources feel different on your skin.

We cannot see infrared, but some animals can. Snake species detect infrared as a means to hunt warm-blooded prey. IR-A is the highest energy infrared (short-wavelength = high frequency = high energy) and this decreases to IR-B and then IR-C. It is important to note that bright light (mimicking the daytime sun) prompts basking behaviour in ectothermic animals such as reptiles because they seek sources of IR-A to deeply warm their tissues (approximately 35% of sun radiance is IR-A). This is also when they get most of their UVB exposure.

Most know that for reptiles, heat is directly related to general activity levels and digestion of food, but it’s more complex than that. All physiological processes that occur within their bodies are temperature dependent, and this includes biological mechanisms that relate to disease resistance.