BEEKEEPING IN THE UK

As a fringe hobby that draws parallels with herpetoculture, we’ve spoken to enthusiasts to find out what’s creating such a buzz.

As a fringe hobby that draws parallels with herpetoculture, we’ve spoken to enthusiasts to find out what’s creating such a buzz.

Busting the many myths of sand boa husbandry

A BROAD LOOK AT BIOSECURITY

We have both an ethical duty and, in some cases, an economic interest in practising good biosecurity to protect our animals.

THE GROUND CUSCUS

Hadlow College are leading the charge in developing our understanding of how to care for these unique animals.

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS

scott@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING

advertising@exoticskeeper.com

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY

Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex

CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4692

Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

Aimee Jones

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather

Follow us

As I write this intro, parts of the UK are hitting 40°C. Not only is this a scary picture of things to come, but it is potentially dangerous for a lot of exotic animals. Many zoos have closed their doors to focus on animal welfare. Although I’m sure this heatwave will be long-gone by the time this magazine reaches readers, we at Exotics Keeper have created content and aim to produce more material to support keepers during times of crisis. We would like to hear from subscribers which blog posts and feature articles would be most useful to you. We always try to balance interesting stories with practical advice, so please do get in touch with any challenges you have faced when keeping exotic animals regardless of your experience level.

This month we’re looking at some of the most underrated pet snakes, the sand boas. Unfortunately, many myths still perpetuate around the husbandry practices of these reptiles, so we caught up with expert breeder, Chris Jones to dispel some of these. We also chose to cover a very fringe aspect of invert husbandry – beekeeping. Hobbyists in the BBKA talk us through their passions for bees. Readers can also find some broad information on biosecurity, which is another often neglected practice.

Recently, we have visited several institutions and attended multiple conferences to bring you some great stories over the coming issues. We are also working towards launching a new, more user-friendly website to give this project some added polish. We at Exotics Keeper are a very small team of dedicated individuals, so every subscriber is important to us. Each subscription allows us to produce more, exciting content to help improve animal welfare and support wildlife charities across the world.

Thomas Marriott Features Editor

Every

Front cover: Rough-scaled sand boa (Eryx conicus)

Right: Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

As voted by readers of Practical Fishkeeping magazine

Uses cultured insect meal to recreate the natural insect based diet that most fish eat in the wild.

Easily digested and processed by the fish resulting in less waste.

Environmentally friendly and sustainable.

02 06 16

02 EXOTICS NEWS The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

06 GROUND CUSCUS The care and keeping of the little-known ground cuscus.

14 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s the mimic poison frog (Ranitomeya imitator).

26 34 41

16

IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT THE HONEY Beekeeping in the UK.

26MORE THAN A BOX OF SAND Busting the many myths of sand boa husbandry.

34A BROAD LOOK AT BIOSECURITY Simple procedures with lifesaving results.

41 KEEPER BASICS: The EK guide to building a pond.

45 FASCINATING FACTS Did you know...?

46 ENRICHMENT IDEAS

Monthly tips on how to enrich the life of your pet.

Former dancer and backing singer to the singer Sinitta, Mr Warren Polydorou, 57, was fined for keeping a pair of servals without a licence on his friends land in Colby, Norfolk. The animals were spotted in an insecure enclosure by a thermal imaging camera attached to a drone. Apparently the animals, two year-olds “Nala” and “Simba”, were bought 18 months ago by Polydorou from a friend in London for £1,500 pair - as a favour, but “the paperwork did not follow” he said. He was fined £674 costs and £40 for evading a DWAA licence.

At ZSL London Zoo the Eastern black & white colobus monkeys were given access to the new “Monkey Valley” exhibit in the redeveloped former Snowdon Aviary for the first time in June via a tunnel which connects their new indoor housing with their redeveloped outside facility. With 1,347 new plants and trees, more than 800 metres of rope, multi-level sunbathing platforms and a 30ft waterfall to explore, the monkeys will be given six weeks to get used to their new domain. It is planned to add some African grey parrots to the mixed species exhibit in due course.

Three Sumatran tiger cubs were born to female “Gaysha” and male “Asim”.

She was originally bred at Pairi Daiza in Belgium in 2008 and is one of only 8 shoebills in European collections. She is being housed in the former scarlet ibis aviary at the zoo and hopefully may be paired up with a male from the EEP breeding programme in due course.

Noah`s Ark Zoo Farm at Wraxall near Bristol has opened the first homegrown, natural, “elephant browse forest” in the U.K. A vast 5,000 square metre forest of Willow, Aspen and Poplar trees has been incorporated into their existing 20 –acre enclosure –which is not only the largest elephant enclosure in the U.K. and Northern Europe, it is the only facility for African bull elephants in the U.K. and it is currently home to “Shaka” and “Janu”. The zoo have been growing plantations of browse trees at various locations around the zoo for the last few years.

A female shoebill or whale-billed stork (Balaeniceps rex) has arrived at Exmoor Zoo in north Devon from a private facility in Cornwall. The bird, named “Abou”, is the first shoebill to be put on public view in the U.K. for many years and is the only example of its kind in the U.K.

At Dudley Zoo & Castle a male Bornean orangutan has been born to 30 yearold female “Jazz” and 33 year-old male “Djimat”. Upper Primates Section Leader, Pat Stevens, said: “The birth of one of the planet’s rarest animal species is so incredibly special and here at DZC we’re all thrilled with our wonderful new arrival. “Jazz, who was born here herself, is an experienced mum, having already reared our youngest female, Sprout, who is now 11 years-old and she’s once again already proving to be a doting parent”.

Keepers were able to confirm Jazz’s pregnancy with a urine test and have been closely monitoring her during her eight-and-a-half month gestation, upping her daily food intake and supplementing the new mum with specialist postnatal vitamins since the birth.

Unlike this corn snake, we have sliding scales...© Noah`s Ark © Exmoor Zoo © DZC

The UK`s first diabetic giant anteater has been fitted with monitor used for humans. Vets and keepers at the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS) are managing the first reported case of diabetes in a giant anteater at Edinburgh Zoo with a blood glucose monitor usually used on humans.

The female, named “Nala” appeared on the BBC Scotland series, Inside the Zoo, earlier this year exhibiting the same symptoms as people do before being diagnosed with the condition. Dr Stephanie Mota, resident veterinary surgeon at RZSS said, “Keepers first discovered something was wrong when Nala was losing weight despite eating the same amount, or sometimes even more, than usual. We carried out a full health check under general anaesthetic, running lots of tests and found that Nala has type 1 diabetes.” While the condition is known to occur in domestic cats, dogs and in tamandua in the wild, no other cases have been reported in giant anteaters. Stephanie continued, “Our keepers did an amazing job quickly training Nala to take an insulin injection every day but the challenge for us was how to continuously monitor her blood glucose levels to ensure she was receiving the perfect dose. Taking bloods daily was not an option, and we did initially start monitoring the levels through urine samples, but we decided to contact some companies who produced human glucose monitors to try and streamline the process, and find a way which would be the least invasive for Nala."

“Dexcom, leading providers of this technology, kindly donated the monitor to our charity and we were able to apply it during one of her training sessions, which now allows us to check her blood glucose levels through an app remotely. Due to her lovely personality, Nala is the ideal candidate for this technology which helps us, and her amazing team of keepers, manage her condition in the best possible way.” The RZSS team recently won a bronze award in the British Association for Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) awards for their efforts in animal husbandry, care and breeding for their work in managing Nala’s condition. The wildlife conservation charity also works internationally with Dr Arnaud Desbiez from the Wild Animal Conservation Institute (ICAS) on the Anteaters and

Highways project for the protection of giant anteaters in Brazil against road traffic accidents which pose a serious threat to the species’ long-term survival in the wild.

More than 200 native white-clawed crayfish were released into safe river sites in Somerset and Hampshire as part of a coordinated effort to boost the dwindling number of this endangered crustacean.

This species is the only native freshwater crayfish in the United Kingdom but it is at risk from non-native, invasive crayfish such as the American signal crayfish. The American signal crayfish not only out-competes the white-clawed crayfish, but carries a fungal disease, called crayfish plague, which is deadly to our native species. Invasive signal crayfish species also have serious economic implications. Their burrows destabilise banks and increase the chance of flooding, causing erosion and collapse and have decimated invertebrate and fish populations within our rivers.

As a result, the native white-clawed crayfish are listed as Endangered on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List.

Bristol Zoo Gardens is home to a hatchery where hundreds of crayfish are bred and reared to adulthood each year, before being released into safe rivers and lakes, free from signal crayfish predators, to boost wild populations. Dr Jen Nightingale, UK Conservation Manager with Bristol Zoological Society, leads the South West Crayfish Partnership. She said: “We are building up populations using captive-born crayfish in the hope that we will prevent them becoming extinct. “Numbers are in decline and, without projects like this, white-clawed crayfish could disappear from south west England in the next 10 years.”

The crayfish have been released ready for the start of the breeding season. Bristol Zoological Society’s crayfish hatcheries are the only ones in England from where thousands of white-clawed crayfish have been taken to ark sites all over the country.

Dr Nightingale said research was taking place across Europe on invasive crayfish control methods, including investigations into curbing the reproduction of signal crayfish, to help ensure the survival of the white-clawed crayfish and other native European crayfish species.

Flexible exotic insurance for every budget. Get a quote at britishpetinsurance.co.uk or call us on 01444 708840

Due to the incredible success of the red kite breeding and release programme during the 80s and 90s in the U.K. it was been decided to supply U.K.-bred birds to release into the wild in Spain. In cooperation with Forestry England, Natural England, Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, the RSPB and the Accion por el Mundo Salvaje (Amus) in Spain, the first batch of 15 juvenile birds haven been sent to Madrid, here they will settle in some holding aviaries and be fitted with monitoring technology before being released into the wild at Extremadura and Andalusia in South western Spain this summer. The birds hail from the forests of Northamptonshire.

The RSPB's Duncan Orr-Ewing said “30 birds will be released this year, with plans to release 30 more birds in each of the next two years. You need to find 90 to 100 birds to create a sustainable population in a given area. That should be sufficient to create a new breeding nucleus of the birds."

Red kites are found across Europe and numbers have increased overall in recent years, although there are still drastic declines in southern Spain, Portugal, and locally in Germany. The UK is now home to more than 10% of the world population of red kites.

Dr Ian Evans of Natural England went out to Spain in the 1990s to collect wild red kites for release in the Chiltern Hills. He said the ones returning this week may be of Spanish descent. "Those birds we took from Spain in the '90s have done really well in Britain - we're talking 4,000-plus pairs in the UK now, which is an incredible success story," he said.

In the 1990s, red kites in Spain were doing well in comparison to the UK, where years of human persecution, including egg collecting, poisoning and shooting, had pushed the bird to near extinction. While red kites in the UK have since boomed, populations in some parts of southern Spain have gone the other way due to a number of factors. The birds of prey are threatened in parts of Spain by factors including poisoning and a lack of food.

The goliath frog – the world’s largest frog has been spotted for the first time in Equatorial Guinea in almost two decades by field researchers from Bristol Zoological Society. Goliath frogs are classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. They can grow to be as big as some house cats, measuring up to 34 centimetres in length and weighing more than three kilograms!

Collated and written by Paul Irven.

Garden Wildlife Health (GWH) is a collaborative project between the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), Froglife and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) which aims to monitor the health of, and identify disease threats to, British wildlife.

www.gardenwildlifehealth.org

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

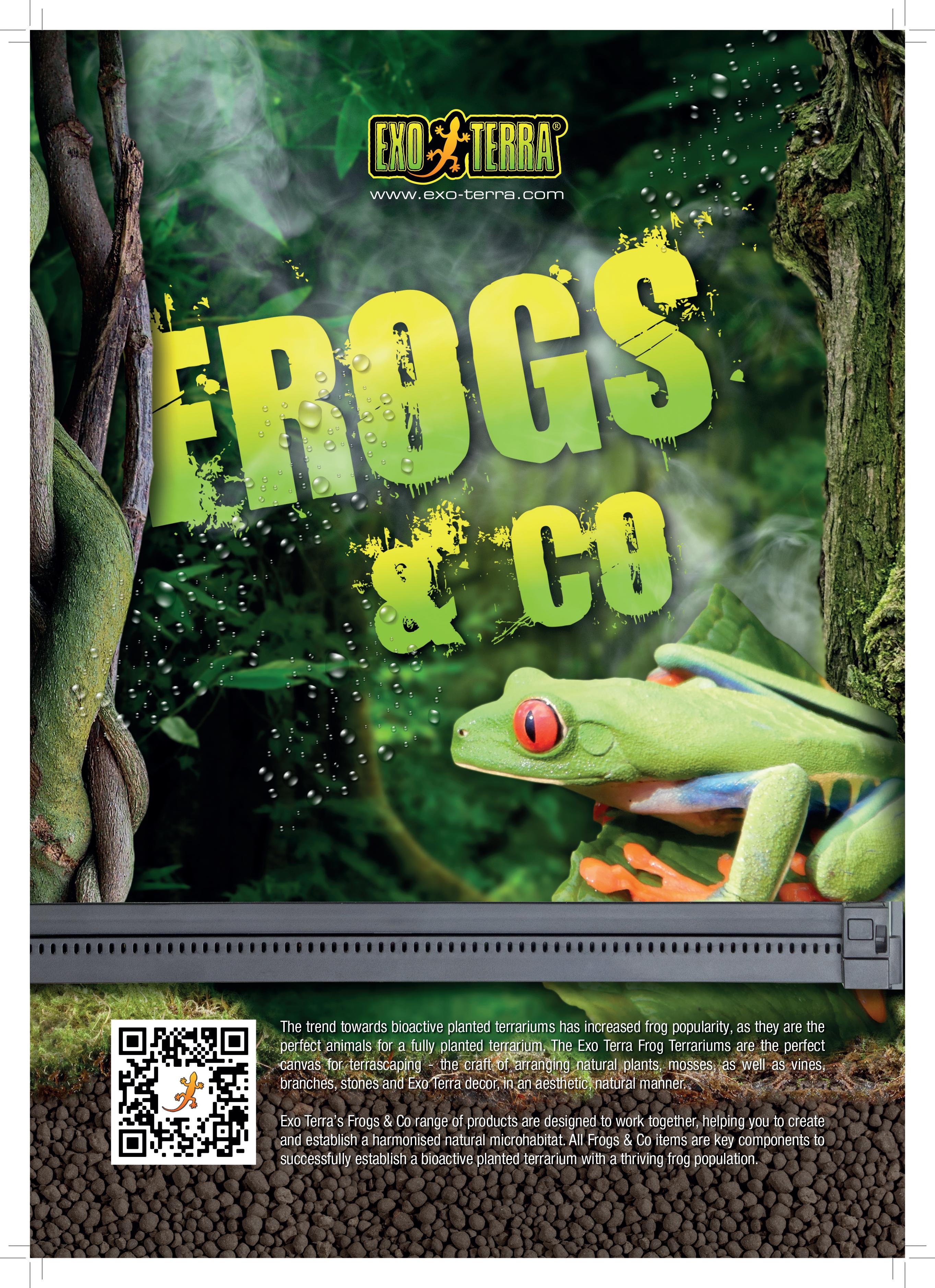

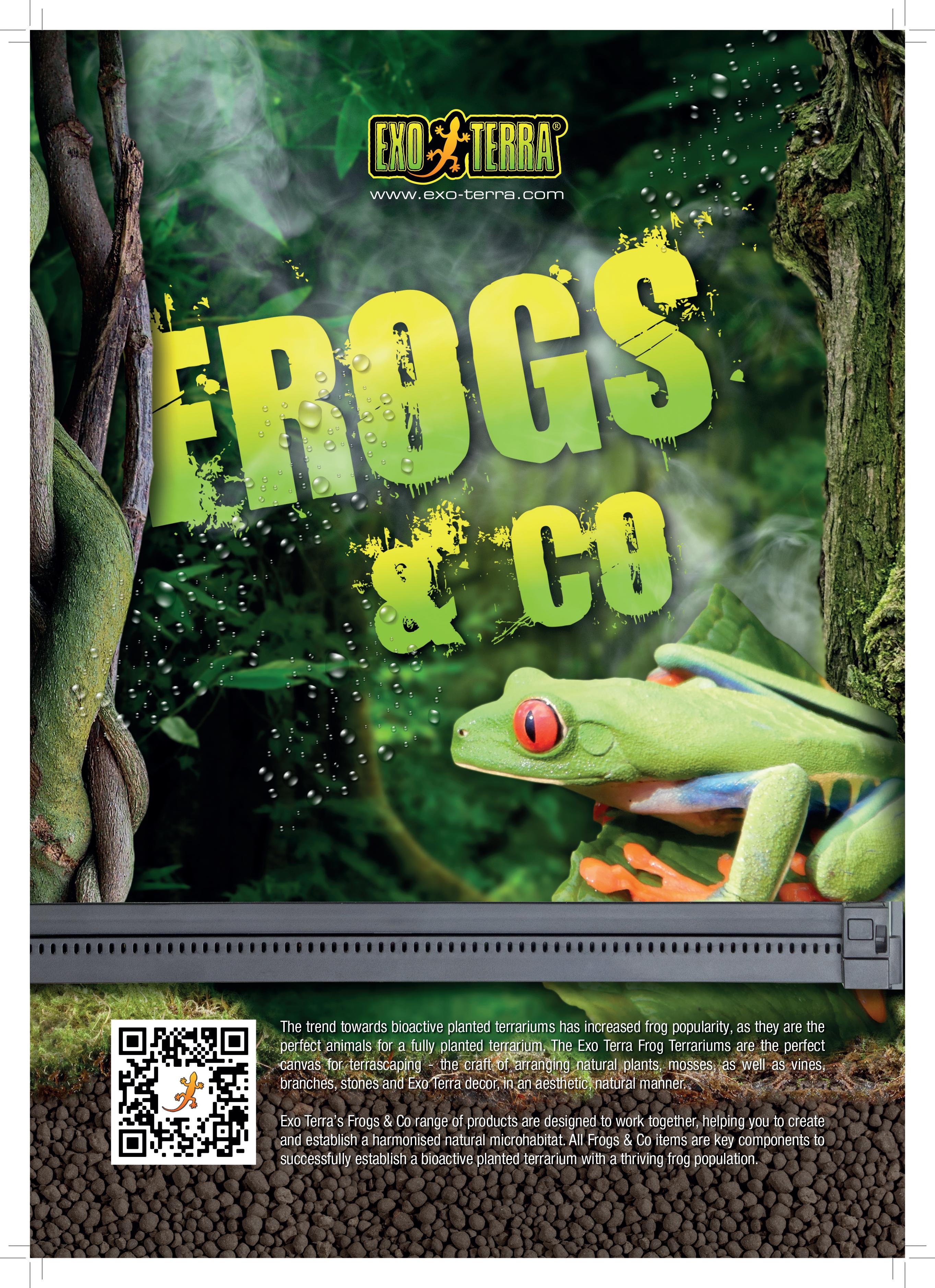

The care and keeping of the little-known ground cuscus.

Ground Cuscus (Phalanger gymnotis)

Ground Cuscus (Phalanger gymnotis)

The ground cuscus (Phalanger gymnotis) is a species of marsupial endemic to New Guinea and the Aru Islands. Although thought to be common across its range, little is known about this cryptic animal. Recent studies suggest population numbers are decreasing and already, it has been extirpated from parts of its former distribution because of excessive hunting. As a species which is rarely exhibited in zoos and is only maintained in a handful of collections, there is a significant gap in our knowledge of ‘best practice’ husbandry guidelines for the ground cuscus. This has prompted staff and students at Hadlow College to lead the charge in developing our understanding of these unique animals.

There are 13 species belonging to the Phalanger genus, which are colloquially named: cuscuses. These nocturnal marsupials can be found from the Cape York Peninsula in North Queensland to Papua New Guinea and the neighbouring islands. They are closely related to possums and live primarily arboreal lives in a diverse range of habitats from tropical forests to urban areas. The ground cuscus is found in the northern half of Papua New Guinea and the neighbouring islands and despite being first kept in the early 20th Century, has been studied by reasonably few institutions. Although the species is currently categorised as "least concern" by the IUCN, there is reason to believe that population numbers are declining at an alarming rate.

Paige Conneely, BSc Student and Animal Management Assistant at Hadlow College told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “The ground cuscus has a history of being collected for the illegal pet trade and hunted for traditional medicines. Their body parts are thought to preserve the health of local

people, making them more of a commodity in their home ranges. Because of this, unfortunately, it is more socially acceptable for them to be hunted and collected illegally from the wild.”

“The first record of these guys in captivity dates to 1933, so they have been kept for a while. In the UK there are around 13 collections housing them, but they are typically off-show and mostly in colleges. The UK has the most collections housing them on record, with just a few more dotted around Europe and the US. Currently, there is no studbook for this species, so it’s really important that we network with other collections on husbandry practices. EAZA has shown interest in their decline back in 2019 and again in 2020, so we’re waiting on this year’s report to see what further comments have been made for this species.”

The college began keeping ground cuscuses in 2016 and since then has invested a lot of time into understanding

their husbandry needs and cognitive abilities. Now, the college keeps a pair; ‘Bulolo’ and ‘Morobe’. These animals are helping to inform other institutions on dietary requirements and enrichment strategies that could be applied to a range of taxa.

Creating an appropriate enclosure for a rarely studied mammal can be a challenge. The college has created both an indoor climate-controlled area, as well as an outdoor exhibit for the cuscuses to utilise. The animals always have access to both parts of the enclosure (unless the hatch needs to be closed to maintain indoor temperatures).

“Although they are called the ‘ground’ cuscus, we’ve noticed that they will spend most of their time in elevated positions” explains students, Mia and Paige. “They are from a wide variety of habitats and in the wild, they will use hollowed-out trees and cave systems as shelter, so it isn’t

surprising that they prefer their higher nest boxes.”

“Although they look slow, they can move extremely quick. They can lunge and jump quite easily. In our experience, they have a mixture of arboreal and terrestrial behaviours. They each have a favourite spot and very distinct personalities. We do find that in summer when the sun sets a bit later, they will come out a bit later. They have that slight change based on the natural cycle. When it’s a bit colder, they will also come out a little earlier. We’re lucky to be able to give them this natural fluctuation that they wouldn’t have in a red light, nocturnal zoo exhibit.”

To cater for the species’ mixed behaviours, BSc students Mia and Paige have utilised a range of climbing and burrowing opportunities by experimenting with different substrates, burrows, climbing apparatus and nest boxes. The students have also chosen to build most of the climbing apparatus out of modular items that can be

easily changed and replaced. Daniel Sutherland, Animal Management Unit Manager added: “Originally, they were on soil with a bit of bark. Over the years this has washed away. So, we experimented with different textures. At the minute we have some beech chips and some soil. We also have a stony area in the flower bed and there is a huge flowerpot in the exhibit that we maintain with loose soil so that they can dig into it if they want to. We sometimes hide some of their food in there too. In the wild, they are frequently found by rivers and streams and they will tend to burrow closer to bodies of water. We are in the process of upgrading the enclosure and will aim to give them a much larger water area, even though it’s not something you would typically associate with an arboreal mammal”.

Mia Birchall, BSc Animal Management Student at Hadlow College added: “I don’t think that working with a nocturnal species is a challenge. Obviously, we can’t be so hands-on with them, but we can record their behaviour using camera traps and they do still come out during the day. We still maintain the species and work on their husbandry even though we don’t have them set up in a ‘nocturnal’ exhibit. We have learnt a lot about the breeding side of things. For example, they will pull fur out, and exhibit ‘scent marking’ behaviours by secreting scents from their glands and urinating. There are also obvious faecal changes when they start to exhibit breeding behaviours. A lot of this has come from observations on the camera traps.”

Enrichment is extremely important for all animals, but creative methods of cognitive enrichment are essential for most exotic mammals. Perhaps this is because we understand more about the mammalian brain, or because animals such as the ground cuscus have digits which they can use to solve puzzles. Either way, testing the boundaries of a species’ cognitive ability is crucial in understanding more about its natural history and behaviours. “We’re currently looking into unpredictive feeding as enrichment” Paige explained. “Sort of how you might have a cat feeder on a timer, we are going to fix one of these to the wall as a feeding method. That is the main challenge we face with nocturnal species - because we don’t see them during the night, we have to put all their food out in the morning and wait for them to come and get it.”

“We’re also testing their cognitive abilities with other enrichment techniques” added Mia. “We place their food onto wooden skewers and fix them into the ground or some mesh. We’ve also smeared honey onto pinecones which Bulolo really loves! We’ve smeared pellets into holes and logs. We’ve used paper bags and hay-filled boxes to hide foods. Sometimes we’ll cut up egg boxes, so they have to put their hands in to get the food. We have also created ball pits for them to forage through. Other places have used scent trails too.”

The staff and students have made several interesting observations through their enrichment strategies already. Mia continued: “Anecdotally, we’ve found that when they have to work for their food, they will eat much more of it. We’ve been stretching their cognitive abilities and I think that’s even more important for a nocturnal species. They come out at night and actually have to work for their food. They are very handsy. When they pick up a food item, they do manipulate it. They will peel bananas and take the skin off of any fruit that we give them.”

Dietary elements and ‘treats’ play a major role in cognitive enrichment techniques across most taxa. Generally, most insectivores or carnivores must hunt what they can to survive. Prey is scarce and therefore most feeds will have consistently suitable nutritional profiles. Omnivorous, herbivorous and frugivorous animals can afford to be slightly fussier. In the wild, this is mitigated by seasonality. For example, many high-sugar fruits and nuts will only be available during certain times of the year. In captivity,

many exotic mammals with broad diets are susceptible to obesity because of the high sugar content in commercially farmed food. This is even more true for frugivorous mammals, which can present a real challenge to keepers. “To ensure we can still provide a healthy diet; we also tweak the food presentation too” added Dan. “So, one day they might get a whole sweet potato, other days it’ll be boiled and mashed and placed in different areas, and sometimes it’ll be cut into different-sized chunks. This provides enrichment, without the need to feed high-sugar items. They will also manipulate vegetables in the same way they will manipulate fruit, which provides some added enrichment. They will use their teeth to peel the skins from carrots and cucumbers, even though these are items they wouldn’t have access to in the wild.”

The dietary requirements of frugivorous/herbivorous mammals are an interesting topic. On the surface, most will eat a very broad range of plants and will generally exhibit signs of ill health much sooner than stoic reptiles, giving the impression that they are ‘easy’ to feed. On the other hand, their true wild diets are much less wellknown and perhaps more difficult to facilitate in UK-based collections (particularly the range of tropical fruits with specific nutrient profiles). Therefore, keepers must find a middle ground that provides all the essential nutrients to their animals, whilst also simulating wild forage as closely as possible.

“Over 98% of the flora found across their range is endemic to the area, so it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what types of vegetation they would be eating in the wild” explained Paige. “Papua New Guinea is one of the most biodiverse places in the world. Also, very few collections have kept historical records of what they’ve successfully fed them on. Their main diet here is rooty vegetables, things like sweet potato and leaves such as chard, kale, spinach, that sort of thing. We only use the fruit for training, to make sure we don’t overdo it with the sugar. We have tried various browse, so things like willow, lime, hawthorn. They have a bit of bamboo growing in their enclosure, but they rarely eat it. Again, that’s why it’s so important to reach out to new collections. If it’s a universally accepted plant we’ll feed it, but then try new things as well.”

“We have to be very careful with sugar content. For example, our bananas are a lot more sugary than the ones they would eat in the wild. They do really like grapes, strawberries, pears and apples. Obviously, they are frugivores but we can simulate that sweet taste of fruit with lower sugar alternatives, which would be more akin to the nutrients they would receive from wild fruits. These are things like roses and coconuts which are naturally sweet. So far, we haven’t seen a big difference in weight, so we’re confident in what we’re doing but still perfecting the formula. Unfortunately, there’s just not that information out there.”

Mia also added that both animals have distinct tastes. Bulolo is particularly fond of peanut’s whereas Morobe is

Hadlow College runs multiple agricultural and animal management courses. As well as a vast range of domesticated livestock, students at level three and above can work with exotic animals ranging from marine fish to marmosets. As well as gaining insight into the dayto-day management of these animals, students are also contributing to ‘best practice’ guides for a range of taxa which are less prevalent in zoo collections. Nocturnal mammals are an excellent example of animals which are undesirable to many zoos that rely on public funding because of their cryptic behaviours. Although ‘nocturnal’ exhibits can be created by using red lights, visitor interaction has limitations when a species is naturally shy and nocturnal. Therefore, private collections and educational facilities offer extra opportunities to study cryptic species, which may benefit conservation efforts in the future.

Please see Hadlow College website for more information on all of our rural and land-based courses – www.hadlow.ac.uk and to check out our events.

less keen. Neither seemed interested in live food. This is valuable information for collections working with other members of the Phalangeridae family. Typically, most arboreal mammals will opportunistically feed on invertebrates as a good source of protein and calcium. Understanding what a species or a captive individual feeds on can help reinforce husbandry practices elsewhere.

Although there are currently 13 Phalanger species, the wider Phalangeridae family consists of six genera with a total of 28 species. Hailing from remote regions of Wallacea, a zoogeographical area famed for its biodiversity, it is highly likely that there are still more species to be uncovered. This amplifies the necessity for a good understanding of captive husbandry with a model species such as Phalanger gymnotis. Unfortunately, the students at Hadlow College are limited to ex-situ research strategies.

“There are rumours that there are two

separate subspecies of the ground cuscus, but our research suggests they’re both the same” added Paige. “We can’t distinctly say that we can see a morphological difference but perhaps in the future, more studies will identify some subspecies. This is a limitation we’ve faced in captivity as we haven’t had the chance to see wild cuscuses to really define any differences. There was a paper that investigated DNA sequence evidence for placement of the ground cuscus in the tribe Phalangerini, so genetic analysis of the captive populations of ground cuscus would be a really interesting study and update, but unfortunately, it just hasn’t been done.”

The students are keen to network with other collections to perform comparative studies of the captive populations of ground cuscus. By formulating a pool of knowledge, they can begin to formulate the basis of a wider research project with in-situ initiatives. For now, the students are working as closely with their captive cuscuses as possible to help inform a

‘best practice’ guide. A major part of this process is stress reduction. Whilst a hands-off approach generally allows the keeper to study more natural behaviours, desensitisation and training techniques can be beneficial for routine checkups or visits to the vets.

Mia explained: “We started scale training Bulolo in March, where he follows a target so he can be effectively weighed. We have also just started crate training. Now, he can get into a crate on voice command which is incredible. I don’t think people realise how cognitively able they are, but we’ve found they can definitely perform tasks.”

Paige added: “With Morobe, we also ‘pouch train’. We need to be able to check her and her pouch without causing too much stress. Although not many people train cuscuses, we’ve found they actually train very well. We have them as a non-handleable species, so our crate training makes things much less stressful for them if they need to go to the vet. We’ve also heard from other collections that if an individual keeper takes a cuscus to the vets, they can end up holding a grudge against that specific keeper, which is something we needed to avoid. Since we started training them, their personality really has come out.”

The students and staff at Hadlow College are now searching for more collections to share their findings

with. Paige concluded: “It’s hard to build up this knowledge when some zoos don’t want to cooperate based on contracts, but we’re working on networking and building those contacts and we are so proud to work with the cuscuses and develop our own best practice guides. It’s a privilege to work with them”. Unfortunately, the boundaries between zoos, private keepers and educational institutions can prevent the spread of information and knowledge and may be slowing progress in exotics keeping. Private keepers rarely have the platform or time to reach large audiences, whilst zoos are under pressures of ‘reputational risk’ for working with individuals outside of their sector. Educational institutions represent a unique middle ground, unrestricted by visitor footfall and international governing bodies and may perhaps hold the key to understanding unique flora and fauna in a different setting. It is important that hobbyists working with rarely-kept species document their husbandry practices to share with the wider community. The students and staff at Hadlow College are excellent examples of what can be achieved when information is transparent and education is shared. Hopefully, in the years to come, more people will know of the ground cuscus and its fascinating behaviours.

Anyone who has any experience with ground cuscus in either a zoo or private setting are encouraged to contact Hadlow College via: groundcuscus@gmail.com

Ranitomeya imitator is a lowland species of thumbnail poison frog from the Peruvian Amazon. The term ‘thumbnail’ is used to describe their miniature size and adults can comfortably sit on a human thumbnail. Like many dendrobates, they’re beautifully patterned, extremely territorial and in the wild, highly toxic. Although there are many locality morphs of R. imitator, the ‘chauzita’ locality are consistent in dark mottled patterns, with vibrant orange and yellow details. They also have very soft calls, which is unlike most thumbnail poison frogs and makes them more appealing to the general keeper.

They inhabit bromeliads and broadleaved plants close to forest streams. However, they are very poor swimmers and keepers should be cautious not to provide pools of water that are deeper than the frog’s body. Once a suitable 45x45x60cm glass bioactive enclosure has been established, care and breeding are relatively straightforward. However, this species, like many amphibians, is extremely sensitive to environmental conditions. Anything higher than 28°C or drier than 50% RH can be very detrimental to the frogs’ health and prolonged periods can be fatal.

Sourcing appropriately sized foods can sometimes prove challenging too. Although adults will feed on the frequently available D. hydei fruit flies and pinhead crickets, young frogs will need the smaller D. melanogaster flies. Dusting these invertebrates with a good quality supplement such as Repashy Calci+ (9/10 feeds) and Vit A (1/10 feeds) is paramount to ensuring the animals get the best diet and retain their vibrant colouration.

Ranitomeya imitator can be housed in small groups as juveniles but must be separated into pairs as adults.

The art of beekeeping, referred to as ‘apiculture’, dates back some 9000 years and is thought to have originated in Ancient Egypt. The discipline, which is now a popular hobby, combines exotics keeping with horticulture and general outdoor pursuits. As well as delicious honey, beekeepers play an important role in supporting the UK’s pollinators as they combine a love of invertebrates with sincere conservation interests. In recent years, beekeeping has seen a boom in the UK. No longer confined to rural landscapes, beekeeping is happening across the UK from urban areas to vast woodlands. As a fringe hobby that draws many parallels with herpetoculture, Exotics Keeper Magazine has spoken to members of the British Beekeepers Association to find out what’s creating such a buzz.

Beekeeping is a unique profession. Whilst there are certain parallels with exotics keeping, horticultural knowledge and a general love for the outdoors are also required to succeed. Beekeeping demands keepers to tend to their hive/s at least once a week throughout at least half of the year. Aside from the obvious benefits of honey, people keep bees for a variety of reasons. Stephen Barnes, Chair of the BBKA Board of Trustees and has been beekeeping since 1997. He told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “My father kept bees for about 30 years and at the time, I wasn’t interested. When he died, I took over. I was only going to keep 2 hives as something to do and now I’ve got 38 and I’m not sure what went wrong!”

“All sorts of people do beekeeping. I see it as a way of

keeping in touch with nature. You notice the seasons, you notice the weather, you become more aware of what is growing around you because you’re aware of what the bees are foraging on. Some keen entomologists keep bees too. Some people keep bees because they think it’s saving the species, or they just love keeping bees. There are also people that keep bees as a bit of supplementary income in retirement.”

Many enthusiasts we spoke to had a similar story to tell. After having their interest piqued by a friend or relative, the support of the British Beekeepers Association helped transition the hobby into a passion. The organisation has created several courses and exams to aid a budding hobbyist to become a ‘master beekeeper’.

Beekeepers must devote a good amount of time to their hobby. Although it may be less restrictive than say, handspraying a poison frog enclosure every day, or preparing fresh greens for a bearded dragon each morning, a beekeeper is expected to work every week (usually at an offsite location), to maintain the hive. Stephen continued: “The ‘season’ starts around mid-March to the end of September. It does depend on which region of the country you’re in and which crops are being grown there. Some keepers will tell you the season finishes in August, but a bit further North we start later and finish later. The winter period is spent setting up equipment ready for the next season. It is possible to whittle it down to about one day of work a week, for 52 weeks of the year depending on how many colonies you’ve got. For

me, I would spend around 2-3 days a week during the season on bees and in the winter, 1-2 days but not every week.”

“Our main job is to make sure that the bees have plenty to sustain themselves. We make sure they’re healthy and not suffering from a disease. Responsible keepers also try to make sure their colonies do not swarm as this can be a nuisance to the local community. In the summer they produce new queens, and each queen has the ability to start a new colony, so the keeper needs to manage that. I find a swarm to be a mystical experience, but it can be terrifying if you don’t understand what a swarm is.”

As well as maintaining their own hives, members of the British Beekeepers Association also work hard to drive

conservation efforts and spread the good word about bees. As vital pollinators, even the introduced or mixed-species honeybees that are maintained by beekeepers must be protected to preserve our wild spaces. The British Beekeepers Association has around 28,000 members with an expected 10,000 more people keeping bees up and down the country. “What we do as an association is encouraging people to plant bee-friendly forage” added Stephen. “The biggest problem that pollinators face is the lack of diverse forage. Wildflowers, trees, hedgerows, hay meadows, all of these things have been slowly taken out of agriculture and this has had a huge impact on insects in general. I remember if you went out on a drive on a Sunday afternoon, when you got back, you’d have to clean the window screen because it was splattered with insect kill. That just doesn’t

happen these days and that’s because population numbers have declined so much because of the lack of forage.”

“There is a concern that the honeybee competes with other bee species for forage supplies. There is some overlap, but very often the other species are foraging on particular nectar and pollen sources, whereas the honeybee is a bit more ubiquitous. The honeybee is the only species that is feasible for a hobbyist to keep or manage. You can provide habitat for other bee species, but they can’t be ‘managed’ so to speak. Some bumblebees are used for commercial pollination, but they are generally imported and survive one season and must be imported again the next year.”

Responsible beekeeping also requires some of the same practices

as herpetoculture. A strict biosecurity process is needed to ensure the health of all colonies and to prevent the spread of potentially harmful diseases. For many keepers, this is managed by using separate gloves and equipment for each hive. For keepers with multiple colonies, each hive is categorised into a separate group and different equipment is used for each block of hives. There are certain areas in the UK where bee diseases are much more common. “The two main notifiable diseases are American foulbrood and European foulbrood” added Stephen. “You do get outbreaks of both from time to time. As far as I’m aware they are only a threat to the honeybee so it wouldn’t affect native insects. Where I am we don’t have any serious disease issues, but in other parts of the country you might dip your wellingtons or dip your tools in F10 between sites or even hives.”

The British Beekeepers Association opposes the importation of non-native honeybees to the UK and instead encourages members to produce their own queens. The Bee Improvement and Bee Breeders Association takes this one step further, with a greater focus on genetics, arguing that non-native honeybees could potentially compete with native species (though the scientific backing for this argument is currently limited). Broadly speaking, one of BIBBA’s primary goals is to encourage keepers to breed as many native European dark honeybees (Apis mellifera mellifera) as possible, to help support a species in decline. The organisation writes: “It is fairly certain that the dark european honeybee, Apis mellifera mellifera, has been native to mainland Britain since before the closing of the channel land bridge when sea levels rose following the last Ice Age. They became isolated and adapted to the different conditions they found themselves in.”

“A. m. mellifera is native to the whole of Northern Europe, north of the Alps from the Atlantic to the Urals, where they evolved in isolation, having been cut off by such natural barriers as mountains, water and ice. With many of the “pure” stocks of all subspecies worldwide, there has been a certain amount of intro-aggression due to bees being introduced into parts where they are not native. Even though their numbers are quite low compared to former times there is still a lot of genetic material left. It is my belief we should be selecting for characteristics in bees that will help them survive, rather than use types that are unsuited and

were very much tougher and didn’t need so much feeding, insulation or dowsing with “supplements”.

In much the same way that many specialist amphibian breeders put great value on genetics, specialist beekeepers believe that having a genetically sound population of endangered animals may support conservation efforts. Unlike amphibian keepers who are currently contending with Chytrid amongst other conservation barriers that prevent the release of captive animals, beekeepers working with the Dark European honeybee are already directly supporting the wider ecosystem.

Although commercial-scale beekeeping can be a profitable business, 90% of beekeepers use their hobby to pay off their overheads. “There are commercial beekeepers who make a good living out of it. For myself, I break even” added Stephen. “My hobby pays for itself, but if I cost my time, I would make a loss. I keep bees because I’m besotted by them. They’re almost my entire life as my wife will tell you. Any honey that I produce and sell is just paying for me to be besotted with my bees. There are three keepers that have over 1000 colonies, but they are the exception. The average number is two or three colonies. There are also a number of bee farmers that have 200300 colonies. After this, you absolutely need to employ somebody to work for you and to do that you would need 1000 colonies to afford it. Some people claim to make good money out of it, but they don’t always consider the

High

Ideal for species which, in the wild, consume a significant amount of fruits and seeds from oleaginous plants (genera Psittacus, Ara, Poicephalus).

Whilst this may sound excessive for a pot of honey, the medicinal benefits of bee products are becoming much more well-known. For decades now, ‘bee pollen’ has been the buzzword used by influencers and health gurus alike. Marketed as a ‘super food’ it is thought to have significant health benefits. While this may be true and tortoises certainly seem to love it (probably more because of its floral fragrance than its trending place on Twitter), honey is consistently being proven to do good. There’s a lot of evidence of the benefits of honey from a health point of view” explained Stephen. “It’s very interesting to look at it as an application to wounds. Honey contains a sterilising agent and growth-promoting agents, but it’s also waterabsorbing. So, when applied to a sore, it will dry that sore out, sterilise it and promote cell growth. There is scientific evidence for that. People are prepared to pay £40 a jar for manuka honey, but they get the same benefits from buying local honey from a beekeeper.”

Beekeeping, like all animal care, is an expensive pastime and one which demands constant attention. It also requires some wild space, which means it can be somewhat exclusive with most beekeepers living in rural communities and often retired. Of course, this is not the case for all keepers but developing the hobby from beginner to fully-fledged beekeeper requires commitment from day 1. Stephen explained: “If you’re starting off from scratch, you need to buy a whole colony. You can’t just buy a queen and hope she creates a colony. You need to start with a full colony and then from that, you can do splits to increase that number. If you do a split, you can buy a queen and put it in the split. However, we would encourage people to produce their own queens, it’s relatively easy. If you split the colony and have half with a queen and half with just bees and eggs, the bees will do it themselves and produce a queen from the eggs.”

The story of the ‘Asian hornets’ has been widely publicised in mainstream media for many years. Usually packaged as “life-threatening giant killer hornets are waiting to annihilate every man woman and child in the British Isles”, the headlines naturally gain attention. Although this is not quite the case, the threat of Asian hornets to the UK’s pollinators is very real. Already having a severe impact in France, Asian hornets are capable of destroying entire colonies of bees in just a few days.

Anne Rowberry is the Chair of the British Beekeepers Association and Event Organiser for the organisation’s ‘Asian Hornet Week’. She told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “I organise the Asian hornet week with DEFRA during the second week of September. The reason we put it there is that Asian hornet queens generally come out around May/ June time in England if they’ve been overwintering.”

“They are in Jersey, they’re already a big problem there. They’re also in Normandy, so they do come across by accident, in ferries, or caravans, or even rolled up in tents. They don’t have to adapt to our climate, they simply build a nest and reproduce. They initially build a small nest in a garage, a shed or a garden bush. Then, when they get to about 200 they will relocate. This is usually in a building or a shed. The time that this larger nest is building up is usually in August/September. Once they get to this point, they begin thinking about reproducing and creating their drones and virgin queens. We have a big week to encourage people to spot hornets and nests around the end of September. It’s only the queen that overwinters, but they can overwinter anywhere really. Compost heaps, piles of wood, etc and then they come out in early spring.”

The Asian hornet has already caused significant damage to pollinator numbers in France. Community outreach is important for the BBKA to help people identify and tackle the ongoing issue. “Our European hornet is very yellow and a sort of maroon-y colour” explained Anne. “The Asian hornet is just slightly smaller (a little bigger than a wasp), appears very black with a yellow face and just before its tail, towards the end of the abdomen, it has a yellow stripe. It has black wings and looks like it’s wearing rugby socks, so the bottom of its legs is yellow. Neither type of hornet is a risk to humans while they’re foraging. If you go too close to an Asian hornet nest or disrupt them, they will attack in numbers. There have been several deaths in France and Portugal because of it.”

Eradication efforts have stepped up a notch here in the UK. As well as specially designed apps and a huge media push every summer, researchers at several universities are beginning to develop new technologies to prevent non-native species from spreading. Anne continued:

“Peter Kennedy from Exeter University has worked on radio tracking, so now if we see hornets. When they come to a feeding station, we can put a little tracker on it and the hornet will fly off and he will radio track that to find the nest. It has been trialled in Jersey and France. The one in Southampton took him two hours to find, so we are getting better and better at tracking and tracing.”

“Last year we only found two nests, one in Ascot and another in Southampton. Both were fairly well developed and the one in Southampton was just at the point where the queens and drones could have left to set up nests of their own the following year. It was spotted in someone’s front garden, which goes to show how difficult they are to spot.”

As with all non-native species, a country or region needs to act quickly to avoid the species gaining a foothold. Whilst eradication attempts can work with some groups of animals, insects which are particularly seasonal and likely to breed prolifically can be more challenging. All members

of the general public must remain vigilant to allow entomologists more time to develop strategies to address the potentially detrimental effects of invasive species.

Beekeeping has seen a boom in recent years. As people seek to reconnect with nature in whichever way they can, even urban landscapes are hosting bee colonies. The Wildlife Trusts have this year launched a campaign to provide ‘bee-friendly bus stops’ across the UK’s cities. These bus stops have ‘living roofs’ to provide valuable forage for insects and are currently in use in several cities in over 40 locations. By the end of the year, over 150 beefriendly bus stops will adorn the UK’s urban landscapes, prompted by The Wildlife Trust’s report, “Insect Declines and Why They Matter”, which outlined how the UK has lost more than 50% of insects since 1970 and showed that 41% of the Earth's remaining five million insect species are now threatened with extinction.

As well as downloading the Asian Hornet Watch app, most members of the public are able to provide some level of bee-friendly forage to help pollinating insects. Even just leaving a small patch of the garden to become overgrown with wildflowers can support the UK’s inverts. Those that wish to take things one step further and keep bees themselves can receive support at training from the British Beekeepers Association website.

Readers can download the BBKA Hornet Week App for free by scanning this QR code:

Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

Kenyan sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

Sand boas (Eryx sp.) are a fascinating, yet often overlooked group of snakes that have been kept and bred by specialist keepers for decades. As their common name suggests, they live predominantly fossorial lives and have developed unique adaptations to thrive in harsh arid environments. Whilst many hobbyists disregard them as uninteresting and reclusive snakes, perfecting the captive husbandry of these animals can be a complex and rewarding endeavour.

There are twelve distinct species of sand boa and several subspecies. They are an extremely widespread genus, stretching across Africa and Asia. Eryx jaculus can even be found in Europe as far West as Greece. There are also several threatened species in India and Sri Lanka. Each species exhibits subtle differences indicating which environments they inhabit. All are short, stocky snakes which help them quickly submerge beneath the sand. They have also developed (to varying extents) a hardened shovel-like nose to allow them to dig through soil and manoeuvre through root systems. Most also have intricate dorsal patterns, to break up the shape of any exposed parts of their body and protect them from aerial predators. Species from sandy environments, such as the Arabian sand boa (Eryx jayakari), have eyes on the top of their heads to allow them to stalk prey within loose sand. Their comical appearance has given the sand boa a reputation far removed from their fierce predatory behaviours. The colouration of all species

varies drastically depending on locality and sex. Males tend to be smaller but much more vibrant. Because they are so widespread and live reasonably cryptic lives, taxonomists are still regularly making distinctions. Most famously, almost the entire Eryx genus was recategorized as Gongylophis between 1999 and 2010.

As ambush predators with straightforward care requirements, sand boas can and have been kept successfully since the 00s. Previously, they were imported from various countries including Tanzania and Pakistan which have since ceased exportation of live animals. Now, all species are CITES listed, which means trade is regulated. Whilst the number of sand boa species available today is a fraction of what it was in the 90s and 00s, good numbers of captive-bred individuals are still being produced. Unfortunately, their simplistic environmental conditions and a misleading common name has created a mirage of myths around the care and keeping of sand boas across the world.

Chris Jones has kept sand boas for 20+ years and has maintained a collection of over 100 snakes across eight distinct species during that time. He has produced several articles and essays on the husbandry of the Eryx genus throughout that time and supported multiple publications on the topic. “Sand boa husbandry really hasn’t advanced much in recent years and that’s something I want to change” explained Chris. “The reality is sand boas are not and are never going to be the most popular pet species because frankly, they hide a lot. That doesn’t mean we can’t provide better husbandry methods.”

There are several species which are readily available in the UK. Although the

Kenyan sand boa is the most popular, the Saharan sand boa (Eryx muelleri), rough-scaled sand boa (Eryx conicus) and Russian sand boas (Eryx miliaris) are also frequently available. “Saharan sand boas are second most popular in the UK because they have been imported as wild-caught for quite some years” added Chris. “Years ago, this used to be why the Kenyan sand boa was so popular, but you can’t do that anymore. Various countries have stopped imports and Tanzania has now been closed for some years. There are now people breeding Saharan sand boas in captivity, which is nice to see. They’re also a very interesting species to breed as they’re an egg-laying species which is extremely unusual for Boids. Eryx muelleri and Eryx jayaraki are

both egg-layers and provide a unique breeding opportunity for hobbyists who were working with them many years ago. The embryos develop inside the eggs within the female’s body for most of their development time. When the snakes are near the end of their development cycle, the female will lay her eggs. So, once they’re laid, they’re supposed to hatch after just two weeks.” As species which inhabit the harshest of environments, this natural adaptation has allowed the gravid females to protect their offspring from dry, hostile conditions and ensure the eggs receive enough hydration to successfully develop.

The popularity of captive-breeding sand boas has naturally progressed into ‘line breeding’ to create morphs.

These were initially produced in America starting with albinos and anerys. Today, there are dozens of line-bred morphs in the USA. Chris continued: “I was the first to bring in the Indian sunset sand boa (Eryx johnii). Although the species had been kept in the country before, Rick Staub in the USA line-bred them to produce the ‘sunset’ variety. Traditionally, as a baby, that species starts off orange and eventually grows into a more drab, brown colour. His selective breeding has now meant that there are highorange Indian sand boas in the hobby.

As well as genetic mutations, various localities such as the “Dodoma” from Tanzania, have brought new colourations and patterns into captive-bred animals. Slowly, these morphs reached Europe and are now becoming increasingly popular in the UK. Chris continued: “Eryx rufescens was once thought to be a separate species. I and many other enthusiasts disagreed with this, and it is nice to see it is now considered a locality

variation of E. colubrinus. Because of this recategorization, nowadays we are starting to see “striped” and “granite” sand boas, which have been produced by breeding two naturally occurring locality variants.”

Some populations are extremely rare and protected by international law. The rough-scaled sand boa (E. conicus) comes from India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. As a region with an alarming rate of snakebite fatalities, instances of human/animal conflict are extremely common. Researchers who are often called out to remove ‘problem’ animals, many of which are nonvenomous snakes, have identified and photographed a naturally occurring population of albino rough-scaled boas in Western Maharashtra. As India is closed for export, this population is protected and provides remarkable insight into an ecosystem that allows snakes with albinism (usually an extremely detrimental mutation) to survive well into adulthood.

Chris has been looking toward natural husbandry methods for a long time, which allowed him to become one of the first UK hobbyists to successfully breed Russian sand boas. This is because he adopted a slightly different approach from many of the commercial breeders at the time. “I didn’t put them into a tub with a heat mat on a thermostat and hope for the best, which is what a lot of people were doing back then” explained Chris. “Sand boas, particularly the Russian species, can be exposed to very harsh winters and very hot summers. Back then, instead of a heat mat underneath, I had a halogen heat lamp to provide overhead heat. The hot spot was more than 42°C. But, all year, I would turn this off at night, so they had no additional heat. During the summer it was warmer and during the winter it was obviously colder, so I basically just changed the photoperiod.

“In the run-up to the breeding season, I would wait until it was raining outside, so the air pressure drops, then I just flooded the tank. I would pour a jug of water into the substrate and completely drench the enclosure. Gradually, as it was warming up, I let the enclosure dry out naturally over a few weeks. Once the enclosure had fully dried out again, I introduced the animals together and they bred successfully. I also applied this technique to Eryx tartaricus (now E. miliaris) from different localities. These were separate subspecies E. t. tartaricus and E. t. speciosa and again, I managed to breed these under the same conditions as the Russian sand boas.”

Mimicking wild conditions, even if they do appear extreme, can provide a wealth of benefits to captive species. From prompting breeding behaviour, to improving health and vitality, the

seemingly harsh seasons that reptiles and amphibians face in the wild are important to their biological functions. Whilst keepers must protect their animals from potentially life-threatening conditions, understanding and recreating the native ecosystems of a species should be a goal for all keepers. With new research and products available, hobbyists have de-bunked many of the myths surrounding sand boa husbandry.

Sand boas only feed on rodents.

In the wild, Kenyan sand boas (and possibly other species, though it has been less widely documented) will eat birds as well as rodents and reptiles. Even though they are primarily fossorial, Kenyan sand boas will opportunistically feed on most suitably sized prey that crosses their path. They often inhabit grassy areas and woodland edges and therefore encounter a variety of prey items including fledgling birds that have just left the nest. In captivity, chicks are readily accepted. Their high fat content is likely to be a welcome treat and one which would, in the wild, support a period of brumation or reduced feeding activity. “There are also other ways of providing an enriched diet” added Chris.“For example, don’t just feed the same sized mouse every time. Maybe one day stick a few pinkies in there. Next time, go for an adult mouse. Although chicks may be a little too large for a male, they can add some variety to an adult female’s diet.”

Another major misconception about sand boas is their fossorial behaviour. Whilst these ambush predators will indeed spend most of their time beneath the ground, as the sun sets, they will emerge to explore. They have even been recorded in elevated positions in tree trunks and amongst tree roots. In captivity, even the largest enclosures will not provide the same climbing opportunities as a wild sand boa might utilise and therefore, all climbing opportunities are likely to be utilised. Active males will leave the substrate to explore

branches and cork bark tubes and so it is a good idea for keepers to maximise the potential of their enclosures by providing branches and décor above the substrate.

Sand boas live in the sand.

It is completely understandable why people might think this. Not only is there a clue in the name, but the most famous sand boa species to those who are not herpetology enthusiasts is the Arabian sand boa. This species is extremely well adapted to harsh deserts with eyes on the top of its head and a pointed snout. Its comical appearance might make it the star of many nature documentaries but it is rarely kept in captivity and thus does not represent the requirements of most commonlykept species. In fact, most sand boas inhabit semi-arid locations and some experience seasonal monsoons. Therefore, a bone-dry tub of play sand does not provide an enriched or naturalistic environment for any of the readily available species.

Chris continued: “Should you keep sand boas on sand? Broadly speaking, no. I have tried many different substrates over the years, and I don’t like sand on its own. It’s just not that natural. Instead, a natural substrate would be more akin to the ProRep BioLife Desert substrate. Or, if you ignore the name, LeoLife is brilliant for rough-scaled sand boas that come from the same India/Pakistan region as leopard geckos. The important thing here is that it’s a loam/clay mix. In some cases, they will want to create a small burrow area which is possible with a clay mix, as opposed to sand which will just collapse in on them all the time. They also hold moisture and they’re just prettier. I’ve also tried using ProRep Tortoise Life which is great for Russian sand boas as well as TortoiseLife Bio which will hold a lot more moisture. I’m testing that one at the moment, but it’s going well. The point is these animals do not come from the Saharan desert where you picture dunes as far as the eye can see.”

Sand boas never see the sun.

Sand boas are mostly nocturnal and spend most of their time beneath the surface of the ground. However, almost all species have been photographed above the surface, during the day (or early evening) at some point. Therefore, full-spectrum lighting is a necessity for Eryx, even if they don’t openly bask like Uromastyx or Testudo from the same regions.

“I’m a firm believer that overhead heat is the right approach” added Chris. “Burrowing animals that reside in deep layers of substrate - particularly underneath a hot rock - will naturally receive heat for several hours after dark. Not only is a spot bulb more natural, but you’re also providing visible light. Sand boas are not strictly nocturnal. I’ve seen them regularly out during the day, depending on the species. There’s a good cause to offer natural light and UV but unfortunately, not enough studies have been done on those species. I must say, I have never seen any sign of ill health in sand boas for not receiving UV. But, as we research more species, we’re learning more about the benefits of UV, so I believe it should be made available to them regardless. In this case, a Zone 1 T5, alongside a flood spot would be perfect.”

The photoperiod is also very important and allows the keeper to simulate seasonality. Although water can be introduced to the enclosure to mimic monsoons, daylight hours are one of just a few of ways that a keeper can provide seasonal fluctuations for their sand boa. “Don’t just leave the lights on for a flat 8 hours a day” added Chris. “In the summer I’ll have mine on for 12-14 hours a day, in the winter it might go down to about 7 hours a day. When there’s more light, there’s also going to be more heat. By leaving the spot on, it’ll naturally provide more heat, but I would still turn everything off at night assuming the keeper has normal household living conditions. The snakes need these sharp night-time temperature drops and maintaining a good photoperiod schedule will ensure the snake can thermoregulate effectively.”

Sand boas are easy to house.

Broadly speaking, sand boas have very manageable care requirements. However, it is important to select the right enclosure for the job. Chris explains: “Sand boas are incredibly strong for a snake. When they want to get their head into something, they are one of the strongest snakes pound-for-pound. Depending on the species, they also have

hardened shovel-like noses, so if they want to get into any nooks and crannies in a wooden vivarium, they potentially could get out. I would certainly lean towards a glass enclosure to house these animals. Although, a very young sand boa could potentially escape from some of the ventilation holes in an ExoTerra or ZooMed terrarium. While the snake is still small, the keeper should consider blocking these holes.” A glass enclosure will also provide more depth for the substrate and allow the keeper to easily mount overhead lighting that is completely out of reach of the snake.

Many keepers are exploring bioactive enclosures nowadays. Even novice keepers can create incredibly naturalistic enclosures for a whole plethora of species. Sand boas are no exception, but special considerations need to be made for their exploratory behaviours and strength. Firstly, the enclosure must be large enough for the snake to manoeuvre around its environment without constantly damaging the plants’ roots. This damage can be mitigated by choosing strong agave plants, which can be planted into the substrate whilst still in their pots. If they are dislodged, they can simply be re-planted. Whilst juvenile sand boas are much less destructive, it is a good idea to allow an enclosure some time (6 - 12 months) for plants to become well-established before introducing an adult sand boa. Once the plants are well rooted, even the bulkiest of sand boas will struggle to uproot them completely. The keeper should identify areas where the snake is most likely to burrow (generally under hides, or beneath the basking spot) and avoid over-planting in these locations.

Sand boas can make excellent pets when cared for properly. However, they may not be appropriate for all new keepers. “In terms of ease-of-keeping, I would say that sand boas are a great beginner snake” Chris added. “Are they the best beginner snake? No. In my opinion, a corn snake will always be the best because most people want something more visible and better to handle. However, if a new keeper is looking to keep a sand boa, I would recommend males because they’re smaller, skinnier and a bit more active too. They are also generally more available and perhaps cost a little less, as most breeders are searching for females. Males are also less likely to destroy plants, so a new keeper can get more creative with their enclosure design. Having said that, they’re not always radically different. For example, a Kenyan sand boa male will be quite a lot smaller than the female – perhaps 2/3 of the size. Indian sand boas, on the other hand, show very little difference.”

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the keeper to do as much research into the species as possible, long before acquiring an animal. Having a multi-faceted approach, by speaking to keepers, breeders and herpetologists as well as researching the wild conditions of this species will ensure that the animal receives the best care and the keeper feels fulfilled in their husbandry practices. Whilst many hobbyists are quick to assume Eryx husbandry is just “keeping a box of sand”, those that are truly passionate about the species can find sand boas to be some of the most fascinating pet snakes available.

Biosecurity is a term used to describe the measures used to prevent the spread of harmful biological substances. In 2020, the world became acutely aware of ‘biosecurity’ in its fight against the spread of COVID-19. At times we were instructed to wash our hands, at other times PPE became mandatory in enclosed spaces and, across the world, every country had a slightly different approach to keeping their population safe. The public looked toward their government officials to protect them from rising cases, new variants, and localised outbreaks. Whilst we may be teetering on anthropomorphism, keepers have both an ethical duty and, in some cases, an economic interest in practising good biosecurity to protect their animals.

With Avian Flu still considered a major threat to birds in the UK, biosecurity is a top priority. Dan Sutherland, Animal Management Team Leader at Hadlow College says “we manage a range of rare duck species here at the college. Since the recent outbreak of avian flu, we’ve had to be extremely careful about who gets to work with these animals. We have foot dips for every enclosure, but whenever anyone needs to do maintenance on the waterfowl, they must wear full PPE. We’re also very careful about which other animals they work with on that day.” As an educational facility, exposure to biosecurity methods can provide valuable insight into professional environments. ‘Foot dips’ are a universal tool used by most zoos and farms and are comprised of a shallow, absorbent mat filled with a powerful disinfectant to prevent the spread of pathogens that might be found on the ground or in soil. Therefore, many territory borders (including countries like Costa Rica and Australia) ban visitors from entering with muddy boots.

Breeding facilities are even more stringent in their approach. Psittacus is a breeding facility for many psittacine birds, with a focus on African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus). As well as manufacturing Psittacus Foods, their facility produces many captive-bred parrots for European hobbyists. Their biosecurity methods are arguably more stringent than most collections in both the zoo and private sector, to ensure the health of their breeding pairs and offspring. Helena Marqués, Training and Technical Manager told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “Our breeding pairs were quarantined and tested for Circovirus, Chlamydiosis and Polyomavirus at the beginning of the project. We haven’t introduced any more external breeding birds. When we’ve needed to replace some of the breeding animals, we have used individuals bred in our breeding centre. We annually check all of our chicks to guarantee our customers that they are purchasing a healthy animal. Additionally, it is a way to retest our centre.”

“We also have strict protocols for staff regarding hygiene, clothing, and staff movement. External visitors are not allowed in any of the facilities holding animals and when they are (repair works for example), they are required to follow strict measures of hygiene and wear special clothing. External objects like cell phones are not allowed either, since they are a potential vector for diseases. We have a pest control plan and all our facilities are indoors and there is no possibility of contact between the native fauna and our birds. This allows us to guarantee the safety of our birds whilst protecting wildlife from pathogens that do not affect the African greys, but that could be potentially harmful to them.”

Amphibians and wastewater disposal Amphibians are perhaps the most delicate of all commonly kept exotic animals. Unfortunately, they are also some of the most susceptible to mortality from disease transmission. Globalised diseases such as Chytridiomycosis have been linked to huge declines in wild amphibian numbers since its discovery in 1938. Although some success stories have surfaced, the picture remains very bleak. A review from the academic journal Science in 2019 stated that the disease chytridiomycosis was a factor in the decline of at least 500 species of amphibians in the last 50 years, and declines >90% in more than 100 species. Alarmingly, the study also

presumed ‘extinction in the wild’ of 90 amphibian species because of the disease.

Chytridiomycosis is caused by amphibian chytrid fungi. Scientists have known about one of these chytrid fungi, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (often abbreviated to Bd) for decades. In 2013, another chytrid was identified as causing population declines in European salamanders. This chytrid, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal for short) has already reached the UK in captive collections and as a result, it is illegal to import Caudata (salamanders and newts) without a screening and quarantine process. Bsal is thought to have originated in Asia and is likely to have spread via the trade of laboratory animals, or via stowaway amphibians from other regions hitching a ride in cargo and finding its way into the environment. There is also concern around wastewater being introduced into the environment from captive, non-native amphibians. This is another reason why biosecurity is extremely important. Not just to protect a captive population from external pathogens, but to protect native wildlife from introduced disease.

Chytrid fungi can infect a wide variety of host species; some asymptomatically. These species may act as reservoirs of infection that facilitate the spread of the pathogen in their environment. The zoospores of the fungus are motile in water and require cool, moist conditions to survive. Here in the UK, conditions are

perfect to allow the disease to spread and can even spread within collections. Amphibian skin works in complex ways to allow respiration, thermo- and osmoregulation. Chytridiomycosis disrupts the water and mineral balance of diseased amphibians which results in death, normally because of electrolyte imbalances that lead to heart failure.

Chytrid is not the only disease that amphibian keepers should be concerned about. Ranavirus, ‘red-leg’ disease and newly emerging forms of ‘Perkinsea’ are all illnesses that can have disastrous effects on amphibians, but which often lie undetected in water. A responsible keeper should: Never dispose of wastewater from an amphibian enclosure near running water. Where possible, try to disinfect any wastewater before disposing of it. Avoid using old bioactive enclosures for new animals, even if the previous inhabitant had no symptoms of ill health. Try to avoid keeping amphibians outside and if amphibians are kept outside, ensure that they are secure and safe from cats or birds which might remove them from their enclosure. Report any mysterious deaths of amphibians to your exotics vet or, in the case of native amphibians, to Garden Wildlife Health.

Treating all water/liquid that has come into contact with your frogs as a biological hazard is the first step to ensuring high standards of biosecurity.

Reptiles can also fall victim to disease without the preventative measures of a biosecurity protocol. The best way to protect our reptiles from disease is to ensure that pathogens cannot be easily spread between individuals, or from the keeper or the environment. There are several illnesses which can affect commonly kept reptiles, with protozoal illnesses such as coccidia and cryptosporidium proving to be quite prolific. Respiratory problems can be caused by fungal infections or materialise as a symptom of other viruses. We are learning more and more about Adenovirus and its natural position in wild animals, but in some species, this can also cause death. Broadly speaking, the best way to protect reptiles from transmittable diseases is to ensure that there is no possible way for the disease to transmit from one animal to another. Reptiles, although they can typically hide it well, will eventually show signs of ill-health much sooner than amphibians.

When it comes to disinfecting surfaces, it is important to consider all methods of transmission. In some cases, an institution that keeps several hundred animals can still have a more successful biosecurity protocol than a pet keeper, that maintains several pets but handles them regularly. Keepers must also consider their clothing as a means of transmission. Therefore, safe disinfectants such as F10 are useful, as they allow the keeper to spray their clothing and footwear without causing damage or potential health problems. F10 is often chosen by zoological institutions as it is universal in its application. It has three core actives that kill bacteria, viruses and fungal spores, but can be used in misting systems to kill harmful bacteria in the water, as a nebulising treatment for respiratory problems and as an ointment for wounds. It can also be used to disinfect surfaces, equipment, and enclosures, with the animals in-situ. Providing the keeper has the correct dilutions, this universal formula is great for a whole host of uses. More recently, many collections are running F10 through a fogging system to help clear water droplets in bioactive enclosures, as well as disinfecting the filters of air-conditioning units to prevent the spread of airborne pathogens.

Anyone who has more than one animal should implement some form of quarantine process when introducing a new animal into their collection. A good way of doing this is to set their enclosure up in another room and maintain the animal there, for a period of one to three months. Disinfect everything when moving between the two rooms, then clean the whole set-up before reinstalling it into an ‘animal room’.

Fish and aquatic animals require just as stringent biosecurity regimes as terrestrial animals. In fact, higher population densities of fragile fish, often sourced from the wild means that fish are amongst the leastforgiving of all animals when it comes to biosecurity. Keepers must be extra vigilant in this regard and enact due diligence from the moment they get their animals.

As with all taxa, it is important that the keeper researches the species in depth before acquiring them. Some fish are much more susceptible to disease than others and in fact, some lineages of fish are even more susceptible or tolerant of pathogens. Having a reputable breeder with a strong understanding of the history of the fish can prevent certain pathogens from being introduced to a collection and make it easier to identify and treat illnesses that have taken hold.