ESPACE 251 NORD “SCHLAGSTÖCKE UND TROMMEL”

27.08—16.10.2021

E2N RÉSIDENCE ATELIER HAECHT

“EST-PERDU, CE QU’IL EN RESTE” 01.10.2020—01.11.2021

LA COMÈTE

“DA-SEIN” 01.08—27.09.2020

RÉALISÉ PAR / DIRECTED BY LAURENT JACOB

“SCHLAGSTÖCKE UND TROMMEL” (2020-2021)

6 — 19 / 25 / 30 — 45 / 49 / 53

Peintures

Maikäfer, Nah-Ost, Mich hat’s vom Kaukasus, Am Gericht, In Ehren an … , 2x Scholl und 2x Ertrunken, Struwelpeter, Interessen Gemeinschaft, Freude schöner, Sophie Scholl –Sainte-Catherine, Volga, Adler, Schlagstöcke und Trommel, Midi Minuit, Sans Titre, Vom Sollen und vom Sein, Chaise, Sans titre, Sans Titre

20 — 21 / 46 — 47 Vues d’exposition

22 Être et paraître

23 Being and appearing

24

Sein und Schein

KURT POTHEN

26 — 28 Notices

29 Vue d’atelier

55 E2N RÉSIDENCE

ATELIER HAECHT

“EST-PERDU, CE QU’IL EN RESTE” (2020-2021)

56 — 74

Dessins

Doublecroix (Archive), Sans titre, Schimmelreiter, Sans titre, Sans titre (Archive),Reichstag 1933, Palais de la Monèda (1973), Sans Titre, Sans Titre, Mòria, Marche vers Rome, Sans titre, Sans titre (Archive), Sans titre (Archive), Aigle 1, Aigle 2

75 — 76

Les dessins de Yann Freichels

77 — 78

Yann Freichels’ drawings

COLETTE DUBOIS

79 Notices

79 Vues d’atelier

81 LA COMÈTE “DA-SEIN” (2019 – 2020)

82 — 103

Peintures

Drei Tote und ein Zug, Pantin, Alaaf, Sans titre (Rivoli), Sans titre, Luik, Maibaum, Sans titre (Klabber), Sans titre, Pourquoi pas ?!, Sans titre, Sans titre

104 — 105 / 111

Vues d’exposition

106 — 110

Notices

2020-2021

Lorsque je suis entré dans l’atelier de Yann Freichels situé Rue de la Brasserie à Liège, j’ai ressenti quelque chose d’inhabituel : rien. Cela m’arrive très rarement en dehors d’une salle de théâtre. C’est de la vision d’un plateau vide que je connais cette impression. Une scène vide offre la possibilité d’un espace que l’on peut remplir avec une chose : le monde. Un monde utopique, dystopique, hétérotopique, voire même un monde réel. Ce qu’ils ont en commun, c’est que ces mondes n’existent avec moi que le temps d’un moment et dans ce lieu.

Un « espace de l’apparaître » (Raum des Erscheinens), comme l’appelle de manière inégalée Hannah Arendt. Un espace dans lequel les propositions, visions, dangers et autre d’un avenir du vivre ensemble peuvent être rendus visibles pour … être débattus. Un espace où chaque chose qui nous différencie est vue et entendue. Perçue. Aísthēsis. Un espace d’art. Un espace où les questions surgissent. Pas de questions rhétoriques. Pas de questions qui ont déjà des réponses. Des questions qui se posent à ceux·celles qui sont prêts à entrer dans un tel espace. Un théâtre, une exposition, un concert ou un bateau de sauvetage en Méditerranée, ou bien d’autres encore. Parfois même un parlement.

Pour moi à ce moment-là : l’atelier de Yann Freichels. Cet espace n’est pas resté vide longtemps – dans le sens d’être dénué d’objets – puisqu’il s’est rempli de tableaux regorgeant d’« histoires » et de « mémoires ». En observateur aguerri, je me méfie de prime abord de ces mécanismes : Yann pivote, place et commente, apparemment à contrecœur, ses œuvres rassemblées de manière apparemment arbitraire. Je décris des impressions. Des interprétations, des opinions d’un événement vécu. D’une manière de faire. Arbitraire sous-entendu constamment démenti à mesure de ses observations concernant ses œuvres. Même si cela se produit de temps à autre, je ne ressens que rarement ce que j’ai ressenti dans l’atelier de Yann Freichels : du désarroi.

Les espaces vides remplis de désarroi sont ceux qui permettent la confrontation. Quand, en tant qu’observateur, je m’autorise à ressentir ce désarroi, des strates s’ouvrent qui naissent de la seule présence simultanée de l’observateur et de l’événement qui provoque cette incertitude. Dans ce cas, la contemplation des œuvres de Yann.

Encore un fois, je pourrais expliquer brièvement ce désarroi : nous venons de la même région, d’une région dont l’histoire semble jouer un rôle central dans ses œuvres. Et ces thèmes, parfois envahissants, sont indéniables. Mais ce ne serait que cela : une explication rapide.

Ces tableaux établissent un lien beaucoup plus subtil entre son histoire personnelle, le rayonnement historique de la région marginale où il a grandi, et son envie irrépressible de s’impliquer dans ce monde par ses tableaux et sa créativité, à propos de laquelle il semble si peu savoir.

Je suis un homme de théâtre. Pas un critique d’art. Pourtant, les tableaux de Yann Freichels ont sur moi un effet que je ne retrouve que rarement au théâtre : une invitation profonde et discrète à se confronter aux histoires et mémoires de ce monde dans lequel nous vivons aujourd’hui ; et quand nous serons prêts, à percevoir les parties savamment mal repeintes de ses tableaux, à façonner notre avenir commun sur la base des différences existantes, petit à petit, dans une discussion ouverte. Que l’issue soit l’échec ou la réussite. L’essentiel est que ce soit encore et toujours nouveau.

Kurt POTHEN

When I walked into Yann Freichels’ studio on Rue de la Brasserie in Liège, I felt something unusual : nothing. This is something that I very rarely experience outside a theatre, where I have already had this feeling on a seemingly empty stage. An empty stage represents the possibility of a place that can be filled with one thing : the world. A utopian, dystopian, heterotopian world or even a real world, if you will. The similarity is that these worlds only exist with me at that moment and in that place.

A “space of appearing” (Raum des Erscheinens), to use Hannah Arendt’s unsurpassable term. A space where propositions, visions, dangers … concerning tomorrow’s living together can emerge in order to be … deliberated. A space where everything that makes us different is seen and heard. Is perceived. Aesthesia. A space for art. A space where questions surface. Not rhetorical questions. Not questions that are already answered. Questions that confront anyone willing to enter such a place. A theatre, an exhibition, a concert or a lifeboat in the Mediterranean, or many other places. Sometimes, even a parliament.

And for me, at that moment : Yann Freichels’ studio. This space has not remained empty – in the sense of being barren of objects – for very long, but has filled up with paintings brimming with paintings full of «stories» and «memories». As an expert observer, I was initially wary of these mechanisms : Yann rotates, arranges, and comments – seemingly reluctantly – the arbitrarily assembled works. I am merely describing impressions. Interpretations, opinions of an experience. Of an attitude. An implied arbitrariness that is constantly debunked through his observations about his works. Even though this occasionally happens, I rarely feel what I felt in Yann Freichels’ studio : disarray.

Empty spaces filled with disarray are those where confrontation is possible. When, as an observer, I allow myself to feel this disarray, layers appear, resulting from the sole simultaneous presence of the observer and the event provoking this uncertainty. In this case, contemplating Yann’s artworks.

Once again, I could succinctly explain this dismay : we come from the same region, a place whose history plays a pivotal role in his work. This reason – sometimes overwhelming – is difficult to ignore. But I’ve only outlined it briefly.

These paintings tie together a far subtler connection between his personal history, the historical influence of the marginal region where he grew up, and his overwhelming desire to engage with that world through his paintings and his creativity, about which he seems to know so very little.

I’m a man of theatre. Not an art critic. And yet, Yann Freichel’s paintings exert an overpowering impact on me that I rarely find in the theatre : a deep and discreet invitation to confront the histories and memories of the world we live in today and when we are receptive to perceiving the skilfully overpainted areas of his paintings, to craft our common future on the basis of existing differences, inch by inch, in an open discussion. Regardless of whether the outcome is failure or success. The point is that it is always new.

Als ich das Atelier von Yann Freichels in Lüttich in der Rue de la Brasserie betrat, geschah mit mir etwas Ungewöhnliches : Nichts. Das passiert mir sehr selten außerhalb eines Theaterraumes. Dort kenne ich das von der augenscheinlich leeren Bühne. Eine leere Bühne bietet die Möglichkeit eines Raumes, der gefüllt werden kann mit : Welt. Utopischer, dystopischer, heterotopischer, meinetwegen sogar realer Welt. Gemeinsam haben sie, dass sie lediglich in diesem Moment, an diesem Ort, mit mir existieren.

Ein „Raum des Erscheinens“, wie Hannah Arendt ihn unübertrefflich nennt. Ein Raum, in dem Vorschläge, Visionen, Gefahren, etc. einer Zukunft des gemeinsamen Zusammenlebens Platz haben zu erscheinen, um … verhandelt zu werden. Der Raum, in dem jenes, das uns unterscheidet gesehen und gehört wird. Wahrgenommen wird. Aísthēsis. Ein Kunst-Raum. Ein Raum, in dem Fragen entstehen. Keine rhetorischen Fragen. Keine Fragen, auf die es bereits Antworten gibt. Fragen, die sich jenen Stellen, die bereit sind, sich in einen solchen Raum zu begeben. Ein Theater oder eine Ausstellung oder ein Konzert oder ein Rettungsschiff auf dem Mittelmeer oder vielen anderen mehr. Manchmal sogar einem Parlament.

Für mich in diesem Moment : das Atelier von Yann Freichels. Schnell wurde dieser alles andere als leere – im Sinne von objektlose Raum – gefüllt mit Bildern voller „histoires“ und „mémoires“. Als erfahrener Beobachter misstraue ich solchen Vorgängen vorerst : Scheinbar willkürlich zusammengestellte Werke werden von Yann gedreht, platziert und scheinbar widerwillig kommentiert. Ich beschreibe Eindrücke. Interpretationen, Urteile eines erlebten Vorgangs. Eines Handelns. Suggerierte Willkür, die sich mit fortschreitenden Betrachtungen seiner Werke immer wieder auch strafen lügen. Selten – aber dennoch mitunter – passiert jenes, was ich dort in Yann Freichels Atelier erlebt habe : Verunsicherung.

Leere Räume, die sich mit Verunsicherung füllen sind jene Räume, die Auseinandersetzung ermöglichen. Wenn ich als Betrachter bereit bin, diese Verunsicherung zuzulassen, tun sich Ebenen auf, die alleine aus der Gleichzeitigkeit der Präsenz des Betrachters und des Ereignisses, das diese Verunsicherung bewirkt – in diesem Fall das Betrachten von Yann’s Werken – entstehen.

Jetzt könnte ich wieder eine schnelle Erklärung dieser Verunsicherung liefern : Wir kommen aus derselben Region, deren Geschichte augenscheinlich eine zentrale Rolle in seinen Werken spielt. Und diese mitunter aufdringlichen Motive sind unübersehbar. Aber es wäre eben nur das : eine schnelle Erklärung.

Sehr viel subtiler verbinden diese Bilder seine persönliche Geschichte, die historische Strahlkraft dieser marginalen Region, in der er aufgewachsen ist, sich mit seinem unbändigen Drang, sich über seine Bilder einzubringen in diese Welt und seinem gestalterischen Können, von dem er scheinbar so wenig viel weiß.

Ich bin Theatermensch. Kein Kunstkritiker. Aber Yann Freichels Bilder bewirken bei mir das, was ich selten im Theater erlebe : Ein unaufdringlich tiefgründiges Angebot, sich mit den „histoires“ und „mémoires“ der Welt, in der wir heute leben, auseinander zu setzen und – wenn wir bereit sind, die kunstvoll schlampig übermalten Stellen seiner Bilder wahr zu nehmen – die Gestaltung unserer gemeinsamen Zukunft, auf Basis von existierender Differenz, Schritt für Schritt in einem offenen Diskurs zu gestalten. Ob scheiternd oder erfolgreich. Hauptsache : Immer wieder neu.

2021, HUILE SUR TOILE, 200 × 209 × 5,5 CM

C’est la première toile que j’ai commencée à l’atelier en sortant des études. Une rencontre sur les coteaux à Liège. Ensuite je l’ai recouverte et j’ai commencé à peindre un monument aux morts très germanique d’un village voisin de mon village d’enfance. Finalement j’ai peint cette personne en demi-équilibre, qui flotte, qui dort. Je lui ai mis un bonnet de nuit. Autour d’elle se retrouvent des hannetons mécaniques. J’en avais quand j’étais petit. Ce sont des éléments que l’on retrouve dans Max und Moritz. Dans une de leurs farces, ils mettent des hannetons dans le lit de leur oncle. Leur oncle se réveille et les écrase avec une brutalité extrême.

2021, OIL ON CANVAS, 200 × 209 × 5.5 CM

This is the first painting I ever started in the studio when I left school. A meeting on the hillside of Liege. Then I covered it up and started painting a very Germanic war memorial in a village near my childhood home. I eventually painted this person who is in half-balance, floating, sleeping. I gave the figure a sleeping cap. There are mechanical beetles around it. I had some when I was little and you often find them in the Max und Moritz books. In one of their pranks, they put beetles in their uncle’s bed. Their uncle wakes up and crushes them with tremendous brutality.

9

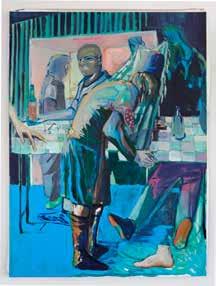

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE, 200 × 149,5 × 6 CM

La femme au premier plan représente pour moi une Turque. La personne à gauche tient une bouteille de « Becks ». Il y a deux clefs sur l’étiquette. Devant la bouteille, une troisième clef, elle ressemble à celle de l’atelier de menuiserie de mon grand-père. La personne à l’arrière porte un vêtement qui, à la base, était censé devenir un uniforme kurde. Sur la table, il y a aussi une boîte de sardines et une bouteille. Les sardines, mon père va souvent les acheter au Luxembourg, il y en a beaucoup de sortes grâce à la communauté portugaise présente là-bas. C’est un objet qui provient de la migration. On y voit une main qui sort du hors-champ. « Nah-Ost » veut dire Proche-Orient.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS, 200 × 149,5 × 6 CM

For me, the woman in the foreground represents a Turkish woman. The person on the left holds a bottle of “Becks”. There are two keys on the label. There is a third key in front of the bottle that looks like the key to my grandfather’s carpentry workshop. The person at the back wears a garment that was originally meant to be a Kurdish uniform. There is also a tin of sardines and a bottle on the table. My father often buys sardines in Luxembourg because there are many different varieties available there, owing to the Portuguese community. This object comes from migration. You can see a hand emerging from the outside. “Nah-Ost” means Middle East.

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE, 173 × 200 × 5,5 CM

La personne couchée vient d’une photo de Robert Cappa. C’est un fasciste italien blessé. Devant lui, on voit un cornet de frites et une colonne plus ou moins dorique. Dessus, il y a une canette de bière écrasée. Il est écrit « Mich hats vom Kaukasus » (« Ça m’a du Caucase »), c’est un morceau de phrase repris du film « Kaspar Hauser » de Werner Herzog. Le Caucase me renvoie à l’Est, quelque chose d’inconnu et de lointain. Sur la colonne, il y avait auparavant un aigle. Pour moi allemand, mais aussi impérial. Je mets cette toile en lien avec mon grand-oncle, décédé en Ukraine en 1943, ou avec son souvenir.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS, 173 × 200 × 5,5 CM

The person lying down is from a photograph by Robert Cappa. He is an injured Italian fascist. There is a cone of chips and a Doric column in front of him. There is a crushed beer can on top. It is written “Mich hats vom Kaukasus” (“I’m from the Caucasus”, a line from Werner Herzog’s film The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser). The Caucasus reminds me of the East, of something unknown and far away. There used to be an eagle on the column. For me it was not only German, but also imperial. I associate this painting with my great-uncle, who died in Ukraine in 1943, or with his memory.

2021, HUILE ET ACRYLIQUE SUR TOILE

170 × 200 × 5,5 CM

À côté d’un des villages d’origine de ma famille, il y a des filons d’or. Cela a engendré une population bizarre à une époque – des « Hillbillies » –, un peu. La dame porte une poêle de chercheurs d’or. Elle est dans la forêt. Au dessus d’elle, il est écrit « Société d’intérêt ». Les arbres sont marqués avec des numéros, la dame porte le numéro 3 et le troisième arbre porte le logo des « Einstürzende Neubauten ».

2021, OIL ON CANVAS

170 × 200 × 5,5 CM

There are gold veins next to my family’s home village. This generated a bizarre population at a time. “Hillbillies” somewhat. The lady is carrying a gold pan. She is in the forest. It says, “Societé d’intérêt” (Society of interest) above her. The trees are marked with numbers ; the lady is numbered 3 and the third tree bears the logo of “Einstürzende Neubauten”.

HUILE SUR TOILE

Sur la table il y a un pot de moutarde, c’est une farce et attrape. On l’avait trouvé en vidant la maison de mon grand-père maternel. À côté il y a une chope « Expo 58 ». Mes grands-parents francophones l’avaient achetée au pavillon allemand lors de l’Exposition Universelle. Il y a une assiette avec un poisson, des capsules, une étoile Mercedes. La table est entourée de trois personnes, celle du milieu montre un livret de propagande allemande de la Première Guerre mondiale. Je l’ai retrouvé dans les archives familiales. Les deux autres ne sont pas concernées par cela. Le chardon remplace une quatrième personne recouverte. Le chardon est un symbole de contradiction. Sur la banderole il est marqué « In Ehren an … » c.a.d. « En l’honneur de … ».

2021, OIL ON CANVAS 172 × 200,5 × 4,5 CM

There is a jar of mustard on the table ; it’s a gimmick. We found it while clearing out my maternal grandfather’s house. Next to it is a mug from the “Expo 58”. My French-speaking grandparents bought it from the German pavilion at the World Fair. There is a plate with a fish, bottle caps and a Mercedes star. The table is encircled by three people ; the central figure holds a German propaganda booklet from the First World War that I found in the family archives. The other two are unconcerned with this. The thistle replaces a fourth person that has been covered. The thistle symbolises contradiction. On the banner it says “In Ehren an …” i.e. “In honour of …”.

Chez un peuple qui vit près de la Volga, il y a une tradition qui ressemble à la Saint-Jean. Les jeunes filles s’habillent en blanc avec des fleurs dans les cheveux. J’aime les traditions qui se retrouvent un peu partout dans le monde. L’habit de la figure de droite est orné d’un motif présent sur les vêtements du peuple de la Volga. J’ai trouvé l’image de cet habit dans un Geo. Le paysage vient d’un souvenir. Peut-être le lac de Butgenbach. Cette toile fait un lien avec des souvenirs, la kermesse ou une procession catholique. On y voit un chardon, une bouteille de bière de l’atelier, un cor de chasse.

2021, OIL, ACRYLIC AND GOUACHE ON CANVAS 170 × 220 × 3,5 CM

There is a tradition among a group of people living near the Volga which is similar to Midsummer’s Day. Young girls dress in white and wear flowers in their hair. I love these traditions that spread all over the world. The outfit on the right is embellished with a pattern found on the clothes of the Volga people. I found the image of this garment in a Geo magazine. The landscape is a memory. Perhaps Lake Bütgenbach … This painting forms a link with memories, the annual fête or a Catholic procession. You can see a thistle, a bottle of beer from the studio, and a hunting horn.

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE, 182 × 2140 × 24,5 CM

La toile a démarré avec une personne en uniforme napoléonien. Avant d’appartenir à la Prusse, ma région avait été conquise par Napoléon. La figure présente porte un Keffieh palestinien. Le conflit en Israel et Palestine m’a toujours tracassé. J’ai mis sur l’habit des croix de croisés. Le gaufrier, que je relie à la culture wallonne, est surmonté d’un aigle que j’ai repris d’un contrat prussien. La figure se trouve sur un ponton. Les nénuphars représentent un certain renouveau. L’eau évoque l’inconnu, le sous-jacent.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS, 182 × 2140 × 24,5 CM

The painting started with a figure dressed in a Napoleonic uniform. Before belonging to Prussia, my region had been annexed by Napoleon. The figure here wears a Palestinian keffiyeh. I have always been troubled by the conflict between Israel and Palestine. I have added Crusader crosses to the garment. The waffle iron surmounted by an eagle, which I borrowed from a Prussian contract, is associated to the Walloon culture. The figure stands on a pontoon. The water lilies represent a form of renewal. Water evokes the unknown, what lies beneath.

2021, HUILE SUR TOILE

180 × 147 × 4,5 CM

Cette toile commence à représenter ce qu’il reste.

Ce qu’il reste du présent?

Non de l’idéal inconnu perdu.

Au dessus de sa tête, j’ai peint les notes de l’« Ode à la joie » qui représente pour moi un idéal humaniste. D’une main elle tient l’interrupteur d’une lampe non branchée. Le pied de lampe vient d’un bougeoir que mon grand-père maternel a fabriqué. Devant la dame il y a un paquet de Gauloises, des sardines, une canette de bière « Crist » et un livre ouvert sur une phrase un peu modifiée de « Baal » de Berthold Brecht : « Es gibt noch Bäume in Mengen, schattig und durchaus kommun um sich oben aufzuhängen oder unten auszuruhen »: « Il y a encore des arbres en suffisance, ombragés et communs, pour se pendre dans la cîme ou se reposer en dessous ». Les tissusrecouvrent des idéaux. J’ai entouré la personne de ses idéaux mais ils lui sont indifférents. Elle ne les connaît pas ou alors elle les a oubliés.

OIL ON CANVAS

This painting starts representing all that remains.

What remains of today?

No, of the unknown, lost ideal.

Above her head, I painted the score of the “Ode to Joy”, which represents a humanist ideal in my eyes. She holds the switch of an unplugged lamp in one hand. The base of the lamp was taken from a candlestick that my maternal grandfather made. A packet of Gauloises, some sardines, a can of Crist beer and a book with a slightly altered sentence from Berthold Brecht’s “Baal” are displayed in front of the woman : “Es gibt noch Bäume in Mengen, schattig und durchaus kommun um sich oben aufzuhängen oder unten auszuruhen”: “There are still plenty of trees, shady and common, to hang yourself from the tops or rest under.” Cloths cover ideals. I have wrapped the person in ideals, but they are indifferent to her. She doesn’t know them or has forgotten them.

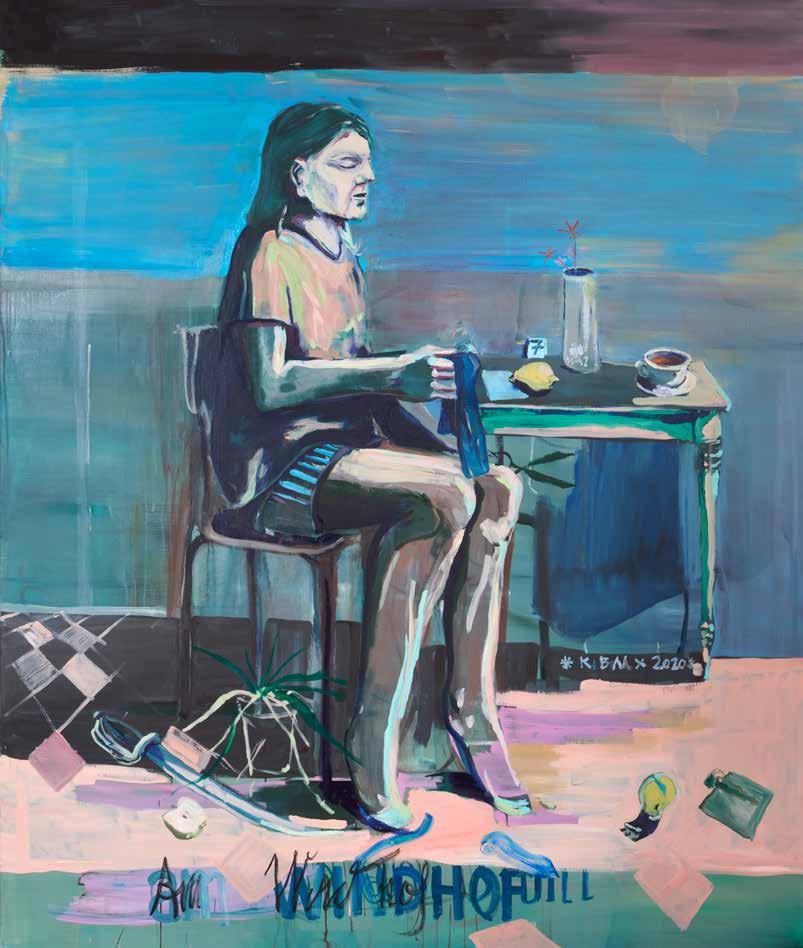

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE

200 × 170 ×6,5 CM

Pour moi cette toile représente une allégorie de la justice Dans le fond de la toile il y a un abatjour, qui se trouvait chez mon oncle, qui est effacé. La toile a commencé en pensant à « L’Opéra de quat’sous » de Berthold Brecht. Le citron et la lampe jaune représentent la « Capri-Batterie » de Beuys. Un collectif d’art allemand avait simulé le vol de ce multiple, afin de le donner en échange des oeuvres d’art volées en Afrique. C’est devenu une scène de café. Pour moi c’est au « Windhof », un café dans mon village d’enfance, à côté du lieudit « à la justice ». C’est là qu’autrefois se trouvait le gibet. Le manche du sabre est repris d’un sabre de Napoléon qui est au Curtius. La dame tient le bandeau de la justice en main mais elle garde les yeux fermés. Dans l’autre main elle tient une paire de ciseaux. Ce sont ceux avec lesquels les femmes coupent les cravates le « Jeudi des femmes ». Il y a un obus comme ceux qui étaient utilisés comme vase dans l’après-guerre. Il contient des Edelweiß. Il est aussi écrit « KBM × 2020 * » pour Caspar, Balthasar, Melchior, 2020. Dans ma région, les enfants viennent demander de l’argent déguisés en rois mages pour des missions en Afrique, en Asie …

For me, this painting constitutes an allegory of justice. There is a lampshade in the background of the painting from my uncle’s house, which has been erased. The painting started out as a reference to Berthold Brecht’s Threepenny Opera. The lemon and the yellow lamp represent Joseph Beuys’ Capri-Battery. A German art collective had faked the theft of this multiple to give it away in exchange for stolen artworks in Africa. It has become a café scene. For me it was the “Windhof”, a café in my home village, next to the hamlet called “à la justice”. This is where the gallows used to stand. The handle of the sword is copied from a Napoleon’s sword in the Curtius. The lady holds the blindfold of justice in her hand while keeping her eyes closed. She is holding a pair of scissors in her other hand. These scissors are used to cut ties on “Women’s Thursday”. There is a shell like those used as a vase in the post-war period. It holds some Edelweiss flowers. It also says, “KBM x 2020 *” for Kaspar, Balthasar, Melchior (Caspar, Balthazar, Melchior), 2020. In my region, children come to collect money disguised as the Three Wise Men to subsidise projects in Africa, Asia, … PAGE 33

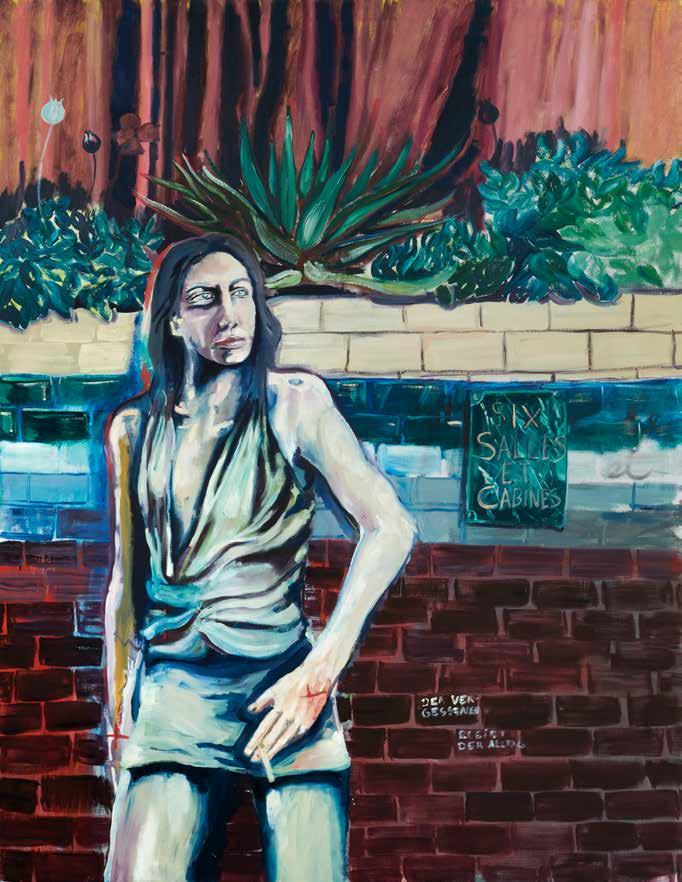

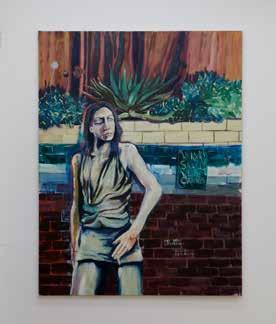

2021, HUILE SUR TOILE 180 × 134 ×3,5 CM

J’ai commencé la toile en voyant des carrés de maisons se faire détruire dans une rue fréquentée par des prostituées. La ville devient de plus en plus propre. On voit derrière la dame qui porte les stigmates, encore un rideau rouge du quartier rouge. Et devant, des plantes dont du pavot, un opiacé qui est aussi un des symboles de Vénus. Sur la plaque en marbre il est écrit : « Six salles et cabines ». C’est écrit sur la devanture du cinéma X Midi-Minuit à Liège. Sur deux briques il est écrit « Les oubliés, il leur reste le quotidien ».

2021, OIL ON CANVAS 180 × 134 ×3,5 CM

I started this painting after seeing blocks of houses being destroyed in a street populated by prostitutes. The city is becoming increasingly clean. Behind the lady sporting the stigmas, you can see another red curtain from the red light district. And in front of her, there are plants including some poppies, an opiate that also symbolises Venus. The marble plaque reads : “Six rooms and cubicles.” This is written on the front of the X-rated cinema «Midi-Minuit» in Liège. On two of the bricks, it says : “Les oubliés, il leur reste le quotidien.” (“The forgotten ones are left with daily life”).

2021 HUILE SUR TOILE / OIL ON CANVAS

170 × 200 ×4,5 CM

2021, HUILE SUR TOILE

175 × 150 ×4 CM

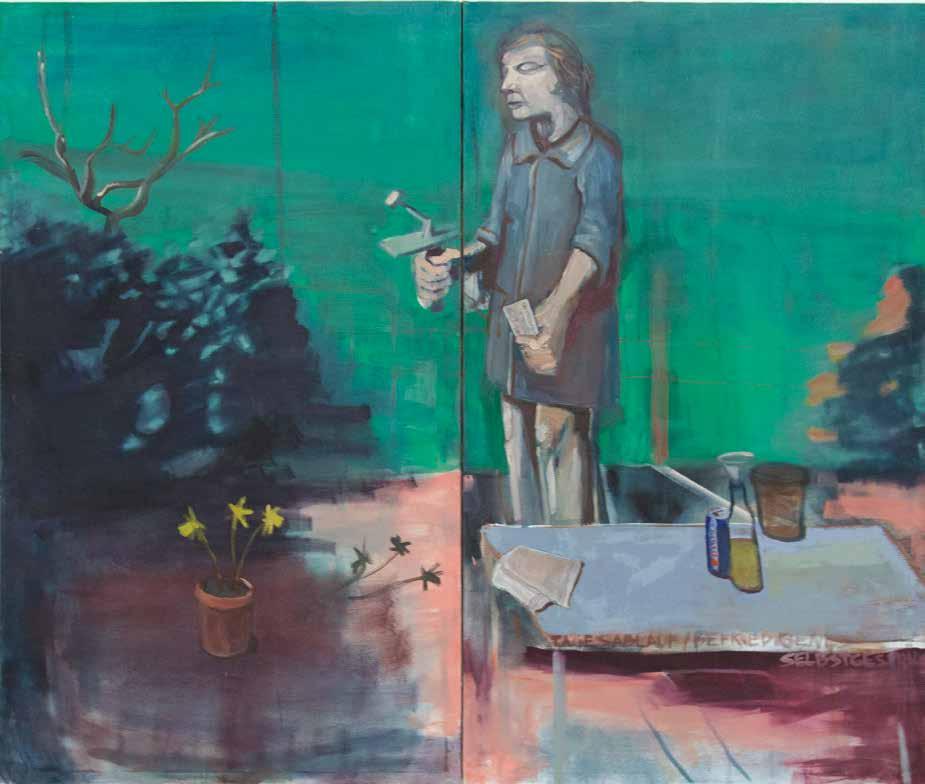

J’ai commencé cette toile après avoir écouté “Les tambours dans la nuit” de Brecht. La pièce parle, pour moi, de la révolution qui est perdue. J’essaye d’arriver à ce qu’il en reste. Au dessus, il est écrit « Matraque et tambours ». C’est suivi d’une phrase « Une jolie communiste sans communisme ». Une toile de Kippenberger s’appelle « Sympathische Kommunistin » c’est à dire « communiste sympathique ». Le casque devait devenir un casque (bleu) allemand.

2021, HUILE SUR TOILE

175 × 150 ×4 CM

I started this painting after listening to Bertolt Brecht’s Drums in the Night. For me, this piece is about the lost revolution. I’m trying to capture what’s left of it. On top, it’s written “Matraque et tambours” (“baton and drum”). The phrase “Une jolie communiste sans communisme” (“A pretty communist without communism”) follows. There is a painting by Kippenberger called Sympathische Kommunistin (sympathetic communist). The helmet was supposed to become a German (blue) helmet.

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE 187 × 200 ×6 CM

Sur cette toile je voulais une répétition comme dans une danse macabre. Pour moi, ce sont deux groupes de gens, la personne de droite représente toujours Sophie Scholl, celle de gauche une noyée. Scholl représente un lien avec l’injustice contre laquelle j’aimerais me battre. C’est une personne qui me touche depuis que je suis petit. Elle représente un de mes idéaux. Dans une danse macabre, elle aurait la place de la mort. Pour moi, elle ne représente pas la mort mais elle accueille les gens morts du « laisser-faire ».

2020, OIL ON CANVAS

187 X 200 X 6 CM

In this painting, I was aiming for a recurrence, as you would find in a Dance Macabre. For me, these are two groups of people ; the person on the right always represents Sophie Scholl and the person on the left a drowning woman. Scholl represents a link with the injustice I want to fight. She is a person who has touched me ever since I was a child. She embodies one of my ideals. In a Dance Macabre, she would take the place of death. For me, she doesn’t represent death but welcomes people who have died from “laissez-faire”.

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE

187 × 200 × 6 CM

Le livre représenté en bas à gauche de la toile est le Struwelpeter. C’est un livre avec des histoires très moralisatrices. La première est celle d’un enfant qui ne veut pas se laisser couper les cheveux ni les ongles, alors plus personne ne l’aime. La figure de gauche porte des insignes militaires allemands. Ces insignes viennent de photos militaires de ma famille. Le poisson est le Christ. Il en reste les arêtes. Il est sur une assiette en étain. La pomme a un rapport avec le péché, peut-être aussi avec le Struwelpeter. Je voulais me laver de l’histoire, la laisser de côté.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS 187 × 200 × 6 CM

The book in the lower left-hand corner of the painting is the Struwelpeter, which contains very moralistic stories. The first is about a child who doesn’t want to have his hair and nails cut, and so nobody loves him anymore. The figure on the left wears German military insignias that come from my family’s military photos. The fish is Christ. The bones are the only that are left of it. The fish is on a pewter plate. The apple is connected with sin, perhaps also with the Struwelpeter. I wanted to wash away the story, to leave it behind.

HUILE ET TEMPÉRA SUR TOILE

Pour créer l’image, j’ai repris une photo de Sophie Scholl. Elle devient un symbole. Je la mets en relation avec Sainte-Catherine. C’est la sainte patronne des étudiants, des philosophes, des théologiens, … Dans ma région à la foire de la Sainte-Catherine, on mange de la soupe aux pois. Ma mère achète des mandarines. La rose à gauche est là comme symbole de la Rose Blanche. Avec les objets personnels ( les mandarines, le bol de soupe), les objets d’histoire (la roue sur laquelle on a tué Sainte-Catherine), je crée des liens entre ce que je connais déjà et ce que j’apprends de l’histoire. J’ai l’impression de me permettre de mieux comprendre Sophie Scholl ou de faire un essai de compréhension.

2021, OIL AND TEMPERA ON CANVAS

180 × 150 × 2,5 CM

I used a photo of Sophie Scholl to create this image. She becomes a symbol. I connect her with Saint Catherine. She is the patron saint of students, philosophers, theologians, … In my region, we eat pea soup during the Saint Catherine’s festival. My mother buys tangerines. The rose on the left symbolises the White Rose. Using personal objects (the tangerines, the bowl of soup), and historical artifacts (the wheel on which St. Catherine was killed), I create links between what I already know and what I learn from history. I have the impression of allowing myself to understand Sophie Scholl better or at least to make an attempt at understanding.

(2020-2021)

MON HYPOTHÈSE, RAPPELEZ-VOUS

QUE NOUS SOMMES TOUJOURS

DANS LA LOGIQUE DE L’HYPOTHÈSE, C’EST QUE LE DESSINATEUR SE VOIT TOUJOURS EN PROIE À CECI, CHAQUE FOIS UNIVERSEL ET SINGULIER, QU’IL FAUDRAIT APPELER L’ INVU , COMME ON DIT L’INSU. IL SE LE RAPPELLE, IL EST APPELÉ, FASCINÉ OU RAPPELÉ PAR LUI. MÉMOIRE OU NON, ET L’OUBLI COMME MÉMOIRE, EN MÉMOIRE ET SANS MÉMOIRE.

* Au XVIe siècle, on employait le verbe « charbonner » pour « dessiner au fusain ».

** Georges Didi Huberman, Survivance des lucioles, Paris, Minuit, 2009.

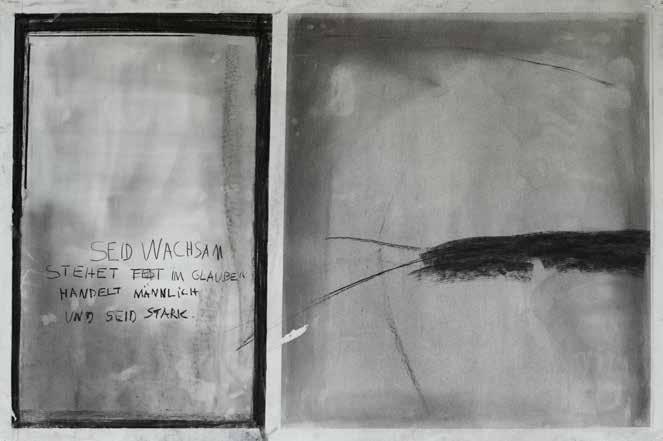

*** « Veillez, soyez fermes dans la foi, soyez virils, soyez forts ». Il faut noter que la citation était particulièrement prisée par les militaires catholiques allemands puisqu’on la trouve déjà dans la propagande épiscopale destinée aux soldats bavarois sur le terrain et dans les hôpitaux lors de la Première Guerre mondiale.

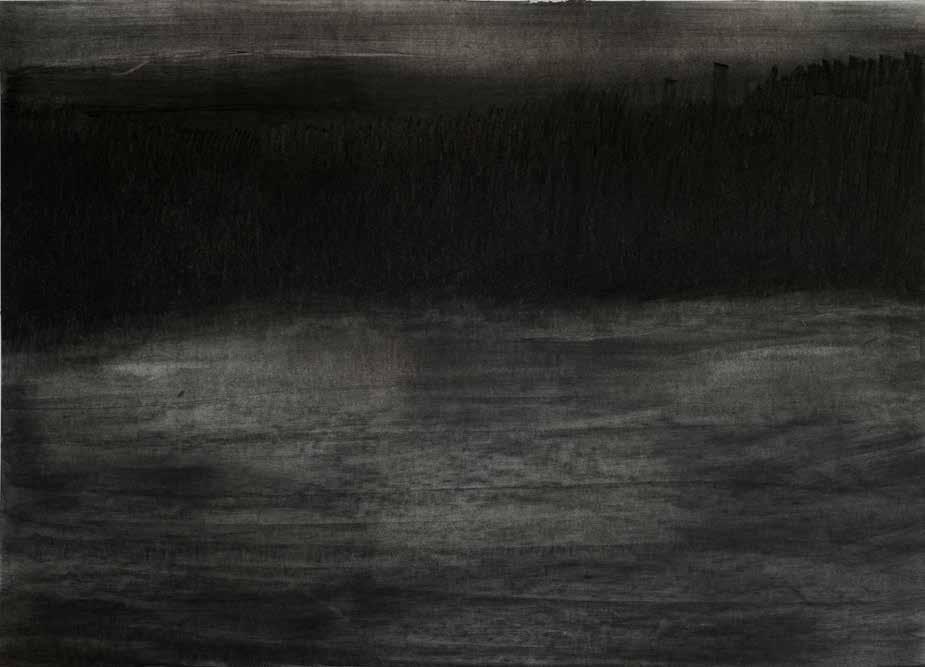

Le jeune peintre Yann Freichels occupe un atelier au sommet de l’ancienne Brasserie de Haecht qui offre un point de vue remarquable sur les coteaux de la Citadelle d’une part et sur la ville de l’autre. Cette vue lui permet de relier ses œuvres à un lieu, il dit « c’est là où je suis né » en désignant une direction au lointain ou, évoquant l’émigration italienne du milieu du XXe siècle, « ils arrivaient ici » en montrant le bas de la colline où court toujours la ligne de chemin de fer. Lors de ma première visite, dès l’entrée, mon regard a été attiré par la masse très sombre d’un grand dessin accroché dans le fond du local. Tandis que l’artiste me menait d’un tableau à un autre, dans lesquels je reconnaissais toutes les qualités d’un véritable peintre, mon regard ne cessait pas de faire des allers-retours entre la peinture qu’il me racontait et le grand dessin noir. C’est un paysage, peut-être celui qui contient toutes les peintures et tous les autres dessins. Réalisé au fusain, il ne comporte aucun espace blanc. Une zone d’un gris très clair décrit la lumière qui sépare la terre et le ciel, quelques éléments – arbres nus, pylônes ou bosquet lointain – s’y inscrivent. La grande zone centrale est d’un noir profond et velouté tandis qu’à l’avant-plan, une surface frottée figure le sol. Freichels me montre alors d’autres paysages de Fagnes, certains d’entre eux évoquent tout autant une surface aquatique qu’une étendue de tourbières et de landes. Tous répondent à cette division horizontale en trois espaces : le plus proche est gris foncé, le plus lointain est saturé de noir – charbonné pour employer un terme ancien * – et le plus clair, nuancé, figure le ciel.

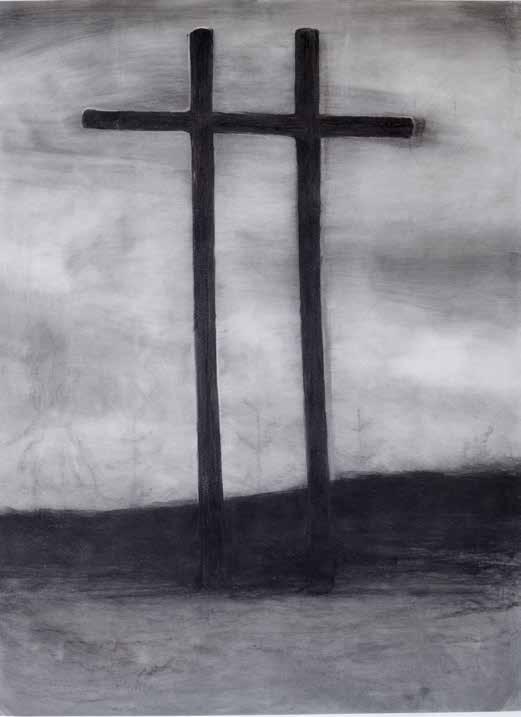

Le paysage, c’est la question du terr(it)oir(e). Avec ces paysages, Yann Freichels décrit le décor de sa jeune vie. L’un d’entre eux est différent : son format est vertical et il apparait comme un espace gris au centre duquel surgit une croix avec une double branche verticale. L’étendue est presque nue – un ciel grisâtre –, au niveau de la ligne d’horizon, on distingue quelques silhouettes de sapins. Je n’ai jamais vu de croix semblable mais, près des nombreuses croix fagnardes, on trouve parfois des pierres taillées ou des colonnes : les anciennes bornes frontières prussiennes. Originaire de la région germanophone frontalière des Pays-Bas, de l’Allemagne et du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, qui a changé souvent de nationalité au fil de l’histoire, Yann Freichels s’interroge beaucoup sur la signification et le rôle des frontières, nul doute que la présence de ces bornes au milieu de la lande l’ait interpellé.

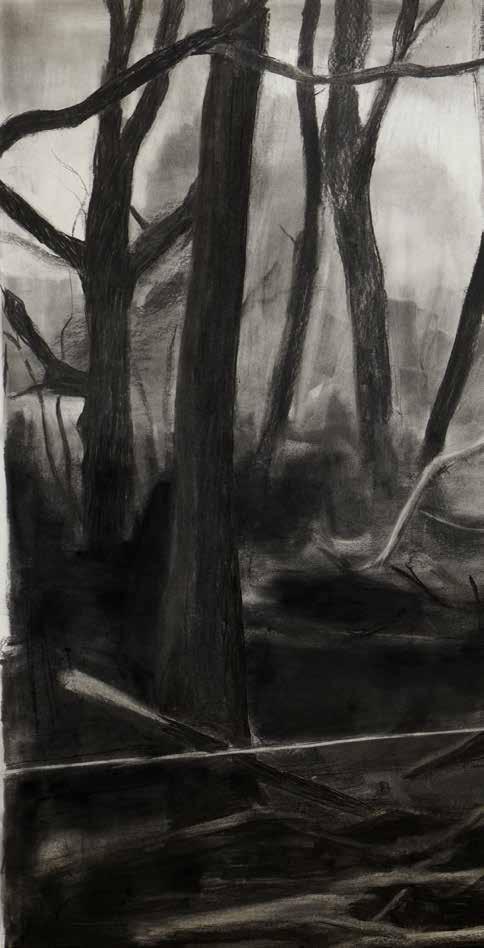

Kandinsky disait que le noir est « la couleur la plus dépourvue de résonance » qui va permettre aux images – mêmes les plus faibles – d’acquérir « une sonorité plus nette et une force accrue ». Yann Freichel m’a montré un autre dessin au noir très dense, une scène avec cinq personnages. Il n’a d’autre titre que le mot « archive » entre parenthèses. Au centre, le noir laisse apparaître une zone un peu plus claire qui forme le dessin de branches d’arbres. Les personnages qui émergent de cette forêt figurée transportent un objet. Leurs bras, leurs mains, leurs vêtements et leurs visages se déclinent dans un gris presque identique à celui qui définit les branches. Parmi eux, il y un enfant. Son bras, son dos et sa joue forment les seules petites taches blanches de la composition. J’ignore quel est cet objet et pourquoi ils le transportent, j’y vois des gestes ancestraux évocateurs de la nuit, de la forêt, quelque chose d’effrayant et d’excitant à la fois. J’ignore qui est cet enfant mais il apporte une lumière, aussi faible que celle des lucioles, mais comme elle, porteuse « d’une résistance, une lumière pour toute la pensée » **. Dans ses fusains, Freichels affirme la présence de la lumière à partir des ténèbres, il donne à voir à partir du noir. Alors le noir n’est plus une surface monochrome, mais le lieu à partir duquel la lumière va surgir.

HISTOIRE(S)

Soit Schimmelreiter, un autre fusain de Yann Freichels. Si ses peintures portent souvent des titres, ce n’est que depuis quelques mois que ses dessins en comportent. Le titre réfère au

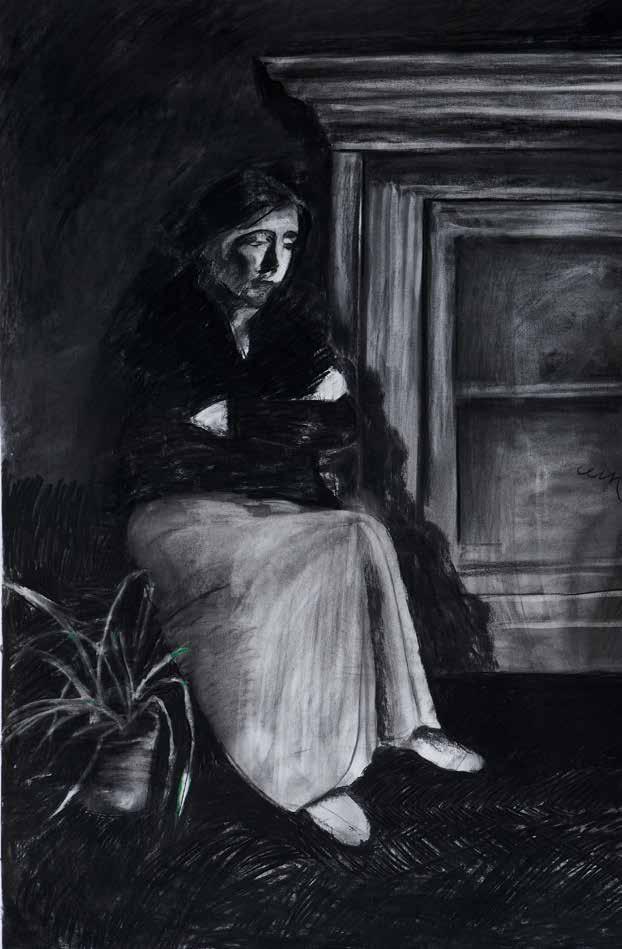

folklore germanique où il désigne un cheval blanc ou un cavalier blanc qui s’attaque aux digues pendant les tempêtes. C’est aussi un roman populaire de Theodor Storm à la fin du XIXe siècle qui, en reprenant le sujet du mythe, met en scène la lutte de l’ancien et du nouveau. Le dessin nous place face à une scène d’intérieur assez sombre. Une armoire imposante en occupe la plus grande partie, elle est encadrée par deux femmes. Sur la gauche, une femme âgée est assise les bras croisés. Seule sa jupe, ses mains et son visage émergent du noir. De l’autre côté, une jeune femme au visage blanc et sans trait est debout, elle brandit une lettre. Dans la partie gauche de la scène on trouve une table claire sur laquelle sont déposés un masque à long nez, une canette, un verre et un plat. Elle est éclairée par un rais de lumière provenant d’une ouverture vers un autre espace. Illustration ? Souvenir d’enfance ? Le mutisme de l’armoire prend la place qu’on dédierait à un feu, la lumière provient d’un espace invisible et la table où trône une canette ramène la scène dans notre siècle. On trouve souvent dans les peintures de Freichels des anachronismes qui introduisent des éléments actuels et souvent triviaux dans des scènes qui semblent surgies d’un passé plus ou moins lointain.

On connait l’histoire mouvementée de la région germanophone et de ses territoires attribués à la Prusse lors du Congrès de Vienne (1815) puis à la Belgique après la Première Guerre mondiale avant de redevenir allemands pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Ses habitants ont reçu la nationalité allemande en 1941 et ont alors été soumis à l’obligation militaire. C’est ainsi que le grand-oncle de l’artiste est tombé sur le front russe dans la nuit du 26 au 27 juin 1942 à l’âge de 28 ans. Yann Freichels a retrouvé son avis de décès portant sa biographie sur une face et sur l’autre, une citation d’un extrait de l’Epître aux Corinthiens portant les mots « SEID WACHSAM STEHET FEST IM GLAUBEN HANDELT MÄNNLICH UND SEID STARK » *** surmonté du chromo d’une Crucifixion. Un étrange dessin porte la citation : les lettres sont tracées à la manière de graffitis sur un fond gris clair encadré de noir qui occupe le tiers de la feuille. A côté, la surface d’un autre rectangle plus foncé est barrée de façon très gestuelle par un épais trait noir.

Si la relation de l’artiste à l’histoire s’attache d’abord aux histoires qu’on raconte et à son histoire familiale, elle aborde aussi des faits historiques mondiaux comme l’incendie du Reichstag ou le bombardement du Palais de la Moneda à Santiago du Chili. On peut difficilement séparer ces deux fusains qui reflètent deux atteintes à des bâtiment symboles du pouvoir, non pour l’annihiler, mais pour s’en emparer. La scène nocturne du premier – les formes naissent du noir tandis que les fumées, les flammes et leurs reflets sont figurées par le blanc du support – s’oppose à la scène diurne du second – le gris de la poussière envahit l’ensemble et l’architecture du bâtiment est décrite par des gris très clairs, le noir profond du fusain figure alors les fumées qui se déploient à partir du lieu d’impact de la bombe. C’est encore le cas des deux dessins au crayon graphite réalisés sur des cartes de mine. L’artiste n’est plus ici dans l’étalement de grandes surfaces de noir, le trait est précis, même si les zones noires sont vigoureusement crayonnées. La première représente une image de la marche sur Rome, l’autre, titrée Mòria, se réfère aux camps de réfugiés aux frontières de l’Europe. On remarque que lorsque l’artiste s’approprie l’histoire du siècle passé (et le moment présent), il le fait en mettant en œuvre un processus de recherche à la fois naïve et complexe. Le choix des événements, toujours dramatiques, qu’il aborde relèvent plus d’une association libre d’objets et d’idées. Il épure sa représentation en ne gardant de ces scènes, malheureusement célèbres, que certains éléments significatifs –fumées, personnages isolés.

Les dessins de Freichels passent par des matériaux précis comme le crayon graphite et le fusain (le plomb et la cendre), ils passent aussi par le geste. Parce qu’il peut explorer de grandes surfaces et mettre en jeu tout le corps, le fusain est proche de la peinture, mais le geste de dessiner s’en éloigne par l’immédiateté de son exécution. Il n’y a alors plus de distance entre la pensée et la main. Elles forment un ensemble qui saisit et qui trace des formes qui portent en elles l’esprit du dessinateur. Idée et geste ne forment plus qu’un pour faire advenir sur le papier traits et surfaces indissociables d’une idée, d’un verdict et d’un désir. L’image pense. Le dessin est de l’ordre de la pensée, comme elle il est fulgurant, spontané et inventif. Comme elle, il mélange réminiscence et imaginaire.

MY HYPOTHESIS, AND REMEMBER THAT WE ARE STILL IN THE REALM OF THE HYPOTHESIS, IS THAT THE ARTIST IS ALWAYS PREY TO THIS UNIVERSAL AND SINGULAR THING, WHICH WE SHOULD CALL THE UNSEEN , JUST AS WE SAY THE UNKNOWN. HE REMEMBERS IT, HE IS CALLED, FASCINATED OR REMINDED BY IT. MEMORY OR NOT, AND OBLIVION AS MEMORY, IN MEMORY AND WITHOUT MEMORY.

JACQUES DERRIDA

* In the 16th century, the verb “charbonner“ was used for “drawing with charcoal“.

** Georges Didi Huberman, Survival Of The Fireflies, Paris, Minuit, 2009 (Translated by Lia Swope Mitchell Minneapolis, MN : University of Minnesota Press, [2018].

*** “Be on your guard ; stand firm in the faith ; be courageous ; be strong”. It is worth noting that the quote was particularly popular with German Catholic soldiers since it can already be found in Episcopal propaganda aimed at Bavarian soldiers on the battlefield and in hospitals during the First World War.

Young painter Yann Freichels works in a studio at the top of the former Brasserie de Haecht. He enjoys remarkable views of the slopes of the Citadel on one side and of the city on the other. This outlook enables the artist to tie his works to a place. Pointing to a direction in the distance, he declares “this is where I was born.” Later, evoking the Italian Immigration of the mid-twentieth century, he says “they arrived there” pointing out the bottom of the hill where a train line still runs.

The first time I visited, my eyes were pulled to the very dark outline of a large drawing hanging at the back of the room. As the artist guided me from one painting to the next – all of which indicated the skills of a genuine painter – my eyes kept going back and forth between the painting he was describing and the large black drawing. It is a landscape, perhaps the one that encompasses all of the paintings and other drawings. Made with charcoal, there are no white spaces. A very pale grey area depicts the light that divides the earth from the sky, and a few elements – bare trees, pylons, or a distant grove – lie within it. The large central area is velvety black, while a rubbed surface in the foreground represents the ground. Freichels then shows me other landscapes of the Fagnes region. Some evoke a watery surface as much as an expanse of bog and heath. All reflect this horizontal division into three spaces : the closest is dark grey ; the furthest is saturated with black – charcoal, to use an old term * – and the palest, nuanced, represents the sky.

The landscape is all about the land. In these scenes, Yann Freichels describes the setting of his early life. One of these landscapes stands out : its format is vertical, and it looks like a grey space at the centre of which a cross with a double vertical branch emerges. The expanse is almost bare – a greyish sky. At the level of the horizon, we can see some silhouettes of fir trees. I have never seen a cross quite like this. However, sometimes, near the many crosses in the Fagnes region, you find carved stones or columns : ancient Prussian boundary stones. Originating from the German-speaking region bordering the Netherlands, Germany and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg – a region that has repeatedly changed nationality over the course of history – Yann Freichels ponders on the meaning and role of borders, and the presence of these boundary stones in the middle of the heathland has obviously triggered his interest.

Kandinsky said that “the black color is the most noiseless paint, against which every other color, even the least sound, sounds and therefore stronger and more accurate.” Yann Freichels showed me another very dense black drawing, a scene with five characters. The only title is the word “archive” in brackets. In the centre, the black reveals a slightly lighter area that forms the outline of tree branches. The characters emerging from this figurative forest hold an object. Their arms, hands, clothes, and faces are coloured in a grey that is almost identical to that of the branches. There is a child among them. His arm, back, and cheek constitute the only small white spots in the composition. I don’t know what this object is or why they are holding it, but I see ancestral gestures evoking the night, the forest, something that is simultaneously frightening and exciting. I don’t know who this child is, but he carries a light, as faint as that of the fireflies, but like them, a light that conveys “resistance, a light for all thought” **. In his charcoals, Freichels confirms the presence of light out of the darkness ; he shows out of the dark. Black is no longer a monochrome surface, but the place from where light will surge.

Schimmelreiter, another charcoal drawing by Yann Freichels. Although his paintings often have a title, it is only in recent months that the artist started titling his drawings. This name refers to Germanic folklore, where it designates an evil white horse or a white rider who attacks the dikes during storms. It also comes from a popular novel written by Theodor Storm at the end

of the 19th century. It uses the subject of the myth to depict the struggle between the old and the new. This drawing depicts a rather dark interior scene dominated by an imposing wardrobe framed by two women. On the left, an older woman sits with her arms crossed. The only elements emerging from the darkness are her skirt, her hands, and her face. On the other side, a young woman with a white, featureless face stands holding a letter. There is a light-coloured table on the left side of the stage upon which are placed a long-nosed mask, a drinking can, a glass, and a dish. The table is illuminated by a ray of light emanating from an opening to another space. An illustration? A childhood memory? The muteness of the cupboard occupies the space intended for a fire, the light comes from an invisible space and the table with the can brings the scene into our century. Freichels’ paintings often feature anachronisms that incorporate present-day and often trivial elements into scenes that seem to have originated in the more or less distant past.

The history of the German-speaking region and its territories is well known. The area was given to Prussia during the Congress of Vienna (1815) and then to Belgium after the First World War, before being returned to Germany during the Second World War. The inhabitants were granted German nationality in 1941 and were forced to serve in the army. The artist’s greatuncle was killed on the Russian front on the night of 26-27 June 1942 at the age of 28. Yann Freichels discovered his death notice with his biography on one side and on the other a quotation from the Epistle to the Corinthians with the words “SEID WACHSAM STEHET FEST IM GLAUBEN HANDELT MÄNNLICH UND SEID STARK ” *** crowned with a chromo of a Crucifixion. A strange picture bears the passage : the letters are drawn in graffiti style on a light grey background framed in black which fills a third of the sheet. Next to it, the surface of another darker rectangle is crossed out very gesturally by a thick black line.

While the artist’s relationship to history is mostly based on the stories he tells and his family’s past, he also tackles world historical events such as the burning of the Reichstag or the bombing of the Palacio de La Moneda in Santiago de Chile. It is difficult to separate these two charcoals reflecting two attacks on buildings symbolising power, not to annihilate it, but to seize it. The nocturnal scene of the first drawing – the shapes rise from the black, while the smoke, flames and their reflections are represented by the white of the canvas – contrasts with the diurnal scene of the second – the grey of the dust pervades the whole and the architecture of the building is described by very light greys, while the deep black of the charcoal represents the smoke billowing out from the site of the bomb’s impact. This is again apparent in the two graphite pencil drawings made on lead cards. Here, the artist no longer sweeps large areas of black ; the line is accurate, and the black areas are vigorously pencilled. The first represents an image of the march on Rome, and the other – entitled Mòria – refers to the refugee camps on the borders of Europe. When the artist appropriates the history of the past century (and the present moment), he does so by means of a simultaneously naive and complex research process. His choice of events is always dramatic and is based on a loose association of objects and ideas. He streamlines his representation by only retaining certain significant elements – smoke, isolated characters – from these regrettably infamous scenes.

Freichels’ drawings are made using precise materials such as graphite pencil and charcoal (lead and ash) but also through his gestures. Since it can explore large surfaces and bring the whole body into play, charcoal is akin to painting, but the gesture of drawing distances itself from painting by the immediacy of its execution. There is no more distance between thought and hand. They form a whole that grasps and traces forms that embody the spirit of the draughtsman. Idea and gesture become one, bringing into existence on the paper the lines and surfaces that are inextricably interrelated with an idea, a verdict and a desire. The image thinks. The drawing is of the order of thought, just like it is dazzling, spontaneous, and inventive. Like it, it combines reminiscence and imagination.

Colette DUBOIS, July 2021.

PAGE 57

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/ CHARCOAL ON PAPER 200 × 150 CM

PAGE 58

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/CHARCOAL ON PAPER 240 × 300 CM

PAGE 60

2021, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/CHARCOAL ON PAPER 200 × 300 CM

PAGE 62

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/ CHARCOAL ON PAPER 72,5 × 109,5

PAGE 63

SANS TITRE (ARCHIVE)

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/ CHARCOAL ON PAPER 72 × 109,5 CM

PAGE 64

2021, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/ CHARCOAL ON PAPER 150 × 215 CM

PAGE 66

2021, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/ CHARCOAL ON PAPER 150 × 220 CM

PAGE 68

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER/CHARCOAL ON PAPER 220 × 270 CM

PAGE 70

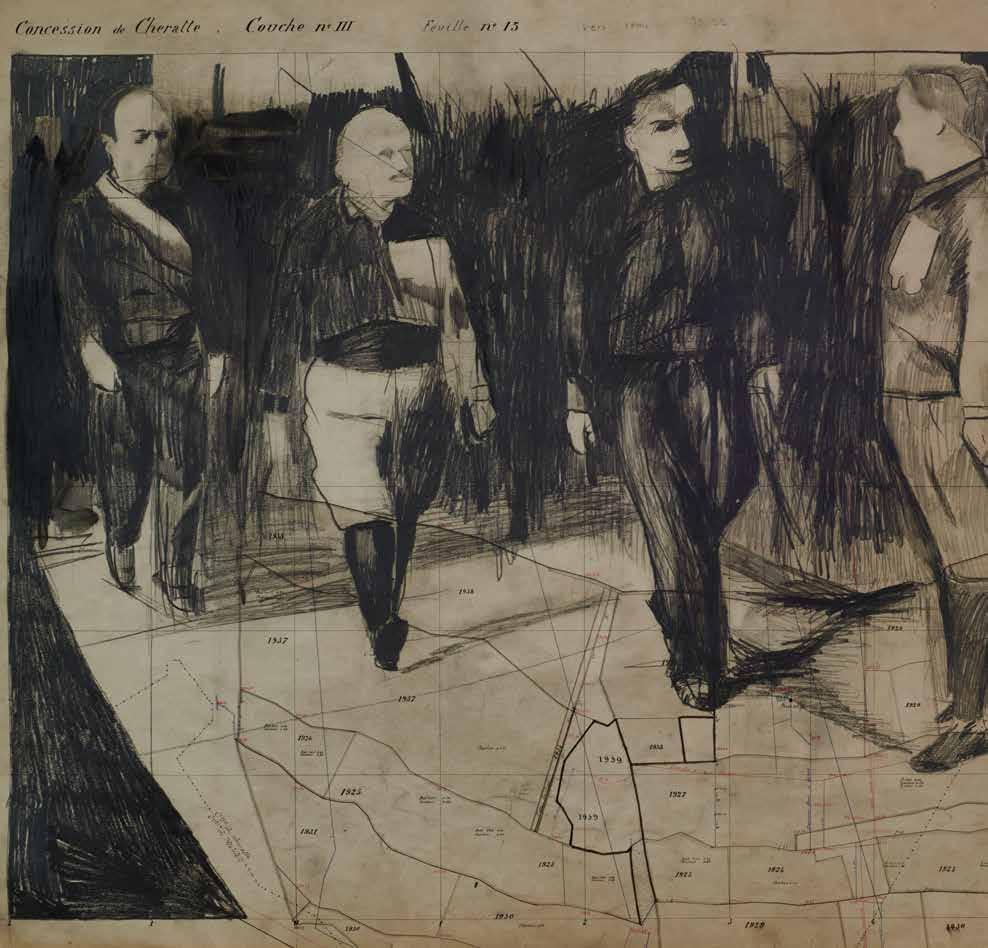

2021, CRAYON GRAPHITE SUR CARTE DE MINE / GRAPHITE PENCIL ON LEAD CARD 67.5 × 97 CM

PAGE 71

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER / CHARCOAL ON PAPER, 109.5 × 72 CM

PAGE 72

2021, CRAYON GRAPHITE SUR CARTE DE MINE / GRAPHITE PENCIL ON LEAD CARD, 69 × 96 CM

PAGE 73

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER / CHARCOAL ON PAPER 72 × 109.5 CM

SANS TITRE (ARCHIVE)

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER / CHARCOAL ON PAPER 72 × 109.5 CM

PAGE 74

SANS TITRE

2020, FUSAIN SUR PAPIER / CHARCOAL ON PAPER 72 × 109.5 CM

PAGE 76

2020, GOUACHE, ENCRE ET CRAYON GRAPHITE SUR PAPIER / GOUACHE, INK AND GRAPHITE PENCIL ON PAPER

27 × 21 CM

PAGE 78

2020, ENCRE ET HUILE SUR PAPIER / INK AND OIL ON PAPER, 27 X 21 CM

(2019

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE

170 × 130 × 4 CM

Quand le confinement a commencé, j’ai travaillé dans la maison de mes grands-parents. Cette maison tombe en ruine. Il y avait des vieilles chaussures qui traînaient dans le grenier. Comme base pour cette peinture, j’ai construit un pantin avec des vieux vêtements à moi, des branches et les chaussures de mon grand-père.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS

× 130 × 4 CM

When the lockdown began, I worked in my grandparents’ house, which is derelict and falling apart. There were old shoes lying around in the attic. As the basis for this painting, I built a puppet with old clothes of mine, some branches and my grandfather’s shoes.

2019, HUILE SUR TOILE

170 × 200 × 4,5 CM

La personne de gauche : La figure porte une « Bomberjacke » verte et orange à l’intérieur. Sur la manche, il y a un drapeau sudiste et il est écrit « PAB ». Il y a un aigle devant. Elle porte une carabine, peut-être de la « FN ». À ses pieds, des mocassins avec des éperons. La « Bomber » est une veste qui était aussi un vêtement de reconnaissance des néonazis. La figure porte des symboles que j’aime (mocassins, la fleur sur la manche), certains que je déteste (le drapeau sudiste, la Bomber). PAB, c’est-à-dire « La loi et l’ordre », qui me pose question, des élements « cowboys » qui me font froid dans le dos. Cette figure m’évoque quelque chose de dual. La figure du milieu porte une couronne d’épines, un t-shirt avec l’inscription « La pêche à la truite en Amérique » (roman de Richard Brautigan)], elle tient une pomme dans sa main. Elle est assise sur une chaise qui, pour moi, est comme celle de mon oncle. Elle a quelque chose de christique (le poisson, la couronne). La pomme, même si elle n’est pas mordue, lui confère, pour moi, un côté ambigu. Ces deux figures sont pour moi les plus oniriques. La figure de droite vient s’ajouter. Elle est plus floue. Sur son t-shirt on voit 3 flèches et il y est écrit RASH (Red Anarchist Skinheads). Plus réelle, à mon avis, mais elle tient aussi une pomme. Autour de la scène, on aperçoit deux seringues effacées, le pied d’une petite figure effacée qui avant était un Jésus. Une canette de bière, un poster Crass (Groupe de musique « Oi »). Par la fenêtre, on voit des maisons, des traits de la tour des finances. On y lit « Der Himmel über » [Berlin (Les ailes du désir de Wim Wenders)] traduit littéralement : « Le ciel au dessus ». Il est écrit « Luik ». Sur la toile on lit aussi : « On la perdera ». C’est un fragment de texte d’un de mes carnets. Sur la table sont posés un sucrier et une bouteille.

2019, OIL ON CANVAS 170 × 200 × 4.5 CM

The figure on the left : The figure wears a green bomber jacket with an orange lining. There is a southern flag on the sleeve. The words “PAB” are written. There is an eagle in the front. The figure carries a rifle – perhaps from the FN – and wears moccasins with spurs on their feet. The Bomber jacket is a garment traditionnaly worn by neo-Nazis. The figure is simultaneously wearing symbols that I like (moccasins, the flower on the sleeve), and others that I hate (the southern flag, the Bomber jacket). PAB, i. e. “ Law and Order ”, raises questions for me, and the cowboy elements send shivers down my spine. This figure reminds me of something dual. The figure in the middle wears a crown of thorns, a T-shirt with the text “La pêche à la truite en Amérique” (a novel by Richard Brautigan) and holds an apple in its hand. The figure sits on a chair that reminds me of my uncle’s chair. There is something Christ-like about it (the fish, the crown of thorns). Although the apple has not been bitten into, I feel that it conveys an ambiguity. For me, these two figures are the most dreamlike. The figure on the right has been added on later and is blurrier. There are three arrows on the shirt that say RASH (Red Anarchist Skinheads). In my opinion, it is more real, but it is also holding an apple. All around the scene there are a couple of faded syringes and the foot of a small smudged figure that was once a Jesus. A beer can, a Crass poster (“Oi” music band). Houses can be seen through the window, as well as the outline of the Finance Tower. It reads “Der Himmel über” [Berlin (Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire)] translated literally : “the sky above”. It says “Luik” (Liège). On the painting, we can also read : “On la perdera”. This is a text fragment from one of my notebooks. There is a sugar bowl and a bottle on the table.

92 SANS TITRE

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE / OIL ON CANVAS 170 × 132,5 × 5 CM

2020,HUILE SUR TOILE

150 × 157 × 4 CM

Les personnes vont l’une vers l’autre. Les objets au sol sont ceux de mon atelier. Le camping-gaz retrouvé chez mes parents, le café « Wiener Art » acheté à Liège. Quand je ne parle pas beaucoup allemand, j’aime bien m’entourer d’objets qui m’évoquent l’allemand et d’éléments qui me rappellent mon autre langue, vice-versa avec le français. Le déclenchement de la toile est L’ange blessé de Hugo Simberg, un peintre finlandais. Les deux personnes portent une branche de bouleau, pour moi, il représente un « Maibaum » c.a.d un arbre de mai, un arbre décoré que, la nuit du premier mai, les célibataires accrochent aux maisons des filles qu’ils aiment bien. Ensuite, dans chaque maison, ils font la fête en groupe avant d’aller à la maison suivante. Ils y laissent une branche de bouleau décorée. C’est une tradition du printemps. Avant, ils utilisaient plusieurs essences d’arbres, chacune avait une signification différente, certaines négatives, d’autres positives.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS, 150 × 157 × 4 CM

People go towards one another. The objects on the floor are from my studio. I found the camping-gas at my parents’ house, and I bought the “Wiener Art” coffee in Liège. When I can’t speak German, I like to surround myself with objects that remind me of the German culture and elements that remind me of my other language and vice versa with French. The starting point for this painting is The Wounded Angel by Hugo Simberg, a Finnish painter. The two people are holding a birch branch. To me, it represents a “Maibaum”, a decorated May-tree that bachelors attach to the houses of the girls they fancy on the night of May Day. Then, they celebrate together in the house before moving on to the next. They leave a decorated birch branch on each façade. It is a spring tradition. In the old days, they used different kinds of trees, each with a different meaning, some negative, some positive.

PAGE 95

PAGE 97

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE 170 × 200 × 5 CM

Je me suis inspiré du tableau La mort de Marat de Jaques-Louis David. Son violon d’Ingres devient son violon.

2020, OIL ON CANVAS 170 × 200 × 5 CM

I drew my inspiration from Jacques-Louis David’s painting The Death of Marat. His hobby (Ingres violin) becomes his violin.

PAGE 99

2020, HUILE SUR TOILE 170 × 200 × 6 CM

Le « Pourquoi-pas » est un bateau dont le capitaine s’appelait Charcot. Il a exploré l’Antarctique. Sur ce bateau ils faisaient des mises en scène pour passer le temps, ils jouaient à boire du champagne sur la banquise en lisant le journal, …

2020, OIL ON CANVAS 170 × 200 × 6 CM

The “Pourquoi-pas” (Why not) was a ship whose captain was called Charcot. He explored the Antarctic. The sailors onboard used to play games to pass the time. They drank champagne on the ice floe while reading the newspaper, …

PAGE 101

2019, HUILE SUR TOILE / OIL ON CANVAS 170 × 170 × 5 CM

2019, HUILE SUR TOILE

170 × 200 × 5,5 CM

Au début, j’avais commencé un paysage avec une vache. Ensuite, j’ai séparé le paysage et j’ai commencé à le recouvrir par une deuxième scène. Au final, j’ai représenté deux figures. La figure de gauche est assise sur un boîtier électrique, elle porte une casquette Citroën qu’un de mes oncles m’avait offerte. En main, elle tient un paquet de frites. Sans être un autoportrait, cette figure a quelque chose de moi, à mon avis. L’autre figure tient une hostie avec dessus un aigle bicéphale, de l’autre main elle tient un verre / un calice, pour moi cette figure a un rapport avec la Pologne. Cette scène a quelque chose de l’Eucharistie. Autour de la scène, il y a un camping-gaz, une casserole de moules (il y avait une expo Broodthaerts à Anvers), un lion (logo de la Flandre – la région flamande avait coupé dans le budget culturel, beaucoup de gens en ont parlé à la radio francophone). À côté de lui, il est écrit « JAJAJA » c.a.d « OUIOUIOUI ». Ensuite, on voit une canette (GLUCK) et deux moules. Au dessus de la toile, des petits pavillons avec des croix. Les croix m’évoquent souvent, d’une part les croisades et d’autre part, la religion et sa morale. Ce coté ambigu me plaît.

2019, OIL ON CANVAS

170 × 200 × 5,5 CM

Initially, I started with a landscape and a cow. Then I divided the landscape and started covering it with a second scene. In the end, I painted two figures. The figure on the left sits on an electric box, wearing a Citroën cap like the one that one of my uncles had given me. She holds a packet of chips in her hand. Without being a self-portrait, there is something of me about this figure I think. The other figure holds a communion host with a double-headed eagle on top, whilst in her other hand she holds a glass/chalice. In my eyes, this figure is related to Poland. This scene has a certain Eucharistic quality to it. All around the scene, there are a camping gas, a casserole of mussels (there was a Broodthaerts exhibition in Antwerp), and a lion (the logo of Flanders – the Flemish region had cut the cultural budget, many people talked about it on the French-speaking radio). Next to the figure, the words “JAJAJA” i.e. “YESYESYES” are written. Then you see a beer can (GLUCK) and two mussels. There are little flags with crosses above the canvas. The crosses often remind me of the crusades and religion with its morals. I like this ambiguity.

SCHLAGSTÖCKE UND TROMMEL

PEINTURES 2020-2021

Dans le cadre de « Elements » : Les Reconnaissances : d’air, de chair et de pierre 27.08—16.10.2021

Lieu / Place : Espace 251 Nord, Liège

EST-PERDU, CE QU’IL EN RESTE

DESSINS 2020-2021

Ouverture E2N Résidence Atelier Haecht dans le cadre de « Elements » 21.05—12.06.2021

Lieu / Place : E2N Atelier Résidence Haecht

DA-SEIN

PEINTURES ET DESSINS 2019-2020 28.08—27.09.2020

Lieu /Place : La Comète, Liège

Réalisé par / Directed by : Laurent Jacob

Production / Production : Espace 251 Nord

Assistant(e)s / Assistants : « Da-sein » & « Est perdu, ce qu’il en reste » – Xavier Vani, « Schlagstöcke und Trommel » — Véronique Rase

Médiation / Mediation : « Schlagstöcke und Trommel » – Véronique Rase Stagiair(e)s / Interns : « Da-sein » – Danh Bao Kyndt, Céline Streveler Coordination – Elements 2021 : Philippe Braem Photographies / Photography : Alain Janssens Régie / Technician : Ibrahim Ali-Hassan Graphisme / Graphics design : « Schlagstöcke und Trommel » & « Est-perdu, ce qu’il en reste » – signesduquotidien.org, « Da-Sein » – nnstudio.be Imprimerie / Printing : Snel Grafics, Liège

Performence : Toon Fret

Remerciements à / Acknowledgements : Pauline Bastin, Stijn Boeve, Lex Ter Braak, Gemmy Chasse, Patrick Delges, Maurice Delwaide, Eric Deprez, Antonin Doppagne, Leo Freichels, Toon Fret, Nadine Gouders, Thierry Grootaerts, Mevlut Kaya, Konso, Basile Kravagna, Nicolas Kozakis, Lasso, Ulrike Lindmayr , Stella Lohaus, Eveline Massart, Jean-Louis Micha, Selçuk Mutlu, Sébastien Plevoets, Gigi Raileanu, Ali Seif, Marie Zolamian, les occupants de la Brasserie Haecht, mes sœurs Laure, Alba et Isabelle

Publication

Editeur / Publisher : Édition Espace 251 Nord – Archives Actives, Liège

Artiste / Artist : Yann Freichels

Conception : Laurent Jacob et Yann Freichels

Production : Espace 251 Nord

Graphisme / Graphic design : nnstudio.be

Coordination : Espace 251 Nord

Stagiaire / Intern : Véronique Rase

Photographies / Photography : Alain Janssens

Auteurs / Authors : Kurt Pothen, Colette Dubois

Traduction / Translation : Ann Michiels – taaladvisie.be

Relecture / Proofreading : Pauline Bastin, Galia De Backer, Gérome Henrion

Remerciements à / Acknowledgements : Pauline Bastin, Gemmy Chasse & Monique Woillard, Colette Dubois, André Delaleau, Antonin Doppagne, Pierre Geurts, Antoine Lantair, Eveline

Massart, Barbara Perrone, Kurt Pothen

Colophon

Achevé d’imprimer à 550 exemplaires en septembre 2021. Completed printing of 550 copies in September 2021.

Première de couverture / Cover : Maikäfer, 2021. Quatrième de couverture / Back cover : Maibaum, 2020.

Production Espace 251 Nord – Archives Actives

En partenariat avec / In partnership with : les Beaux-Arts de Liège (Ecole supérieure des Arts de la ville de Liège) – www.esavl.be

Espace 251 Nord reçoit le soutien du / With the support of : Ministère de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Administration générale de la Culture, Service des Arts plastiques, de la Wallonie et de la ville de Liège

Avec la complicité du Centre Henri Pousseur pour le Festival Images Sonores

Musées et instituts d’art participants à Elements 2021 / The partner art museums and institutes for Elements 2021 : Bonnefanten, Bureau Europa, Jan van Eyck Academie & Marres – Maastricht SCHUNCK – Heerlen, De Domijnen – Sittard-Geleen, Z33 à Hasselt, FLACC et CIAP – Genk Espace 251 Nord – Liège

Avec la collaboration de / With the collaboration of : La Comète

Espace 251 Nord asbl

Rue Vivegnis, 251 4000 Liège / Belgique +32 (0)4 227 10 95 info@e2n.be www.e2n.be

Tous droits réservés / All rights reserved ©Espace 251 Nord et Yann Freichels

Cet ouvrage ne peut-être reproduit, même partiellement, par quelque moyen que ce soit – impression, photocopie, microfilm, etc. –No part of this work can be reproduced by any means – print, photocopy, microfilm, etc. – without the written autorisation of th publishers.

ISBN : 978-2-9601301-5-7

Dépôt légal : D/2021/13.106/2