SPECIAL TOPIC

SPECIAL TOPIC

EAGE NEWS Association plans 75th anniversary

CROSSTALK The fight for Venezuala’s oil

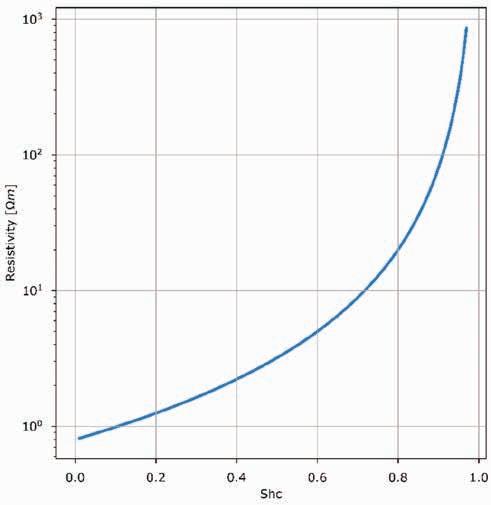

TECHNICAL ARTICLE Reservoir resistivity modelling for CSEM

Opening Ceremony, Workshops, Field Trips, Short Courses, Technical and Strategic Programmes, Exhibition, Hackathon, Community and Student Programme, and Social Programme Exhibition,

REGISTER BY 15 MARCH TO SECURE

SCAN THE QR CODE TO REGISTER

FIRST BREAK ®

An EAGE Publication www.firstbreak.org

ISSN 0263-5046 (print) / ISSN 1365-2397 (online)

CHAIR EDITORIAL BOARD

Clément Kostov (cvkostov@icloud.com)

EDITOR Damian Arnold (arnolddamian@googlemail.com)

MEMBERS, EDITORIAL BOARD

• Philippe Caprioli, SLB (caprioli0@slb.com)

• Satinder Chopra, SamiGeo (satinder.chopra@samigeo.com)

• Anthony Day, NORSAR (anthony.day@norsar.no)

• Kara English, University College Dublin (kara.english@ucd.ie)

• Hamidreza Hamdi, University of Calgary (hhamdi@ucalgary.ca)

• Fabio Marco Miotti, Baker Hughes (fabiomarco.miotti@bakerhughes.com)

• Roderick Perez Altamar, OMV (roderick.perezaltamar@omv.com)

• Susanne Rentsch-Smith, Shearwater (srentsch@shearwatergeo.com)

• Martin Riviere, Retired Geophysicist (martinriviere@btinternet.com)

• Angelika-Maria Wulff, Consultant (gp.awulff@gmail.com)

EAGE EDITOR EMERITUS Andrew McBarnet (andrew@andrewmcbarnet.com)

PUBLICATIONS MANAGER Hang Pham (publications@eage.org)

MEDIA PRODUCTION

Saskia Nota (firstbreakproduction@eage.org)

Ivana Geurts (firstbreakproduction@eage.org)

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES corporaterelations@eage.org

EAGE EUROPE OFFICE

Kosterijland 48 3981 AJ Bunnik

The Netherlands

• +31 88 995 5055

• eage@eage.org

• www.eage.org

EAGE MIDDLE EAST OFFICE

EAGE Middle East FZ-LLC Dubai Knowledge Village PO Box 501711

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

• +971 4 369 3897

• middle_east@eage.org

• www.eage.org

EAGE ASIA PACIFIC OFFICE

EAGE Asia Pacific Sdn. Bhd. UOA Centre Office Suite 19-15-3A No. 19, Jalan Pinang 50450 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

• +60 3 272 201 40

• asiapacific@eage.org

• www.eage.org

EAGE LATIN AMERICA OFFICE

EAGE Americas SAS Av Cra 19 #114-65 - Office 205 Bogotá, Colombia

• +57 310 8610709

• americas@eage.org

• www.eage.org

EAGE MEMBERS’ CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Update via your MyEAGE account, or contact the EAGE Membership Dept at membership@eage.org

COPYRIGHT & PHOTOCOPYING © 2026 EAGE

All rights reserved. First Break or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transcribed in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, including photocopying and recording, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

PAPER

The publisher’s policy is to use acid-free permanent paper (TCF), to the draft standard ISO/DIS/9706, made from sustainable forests using chlorine-free pulp (Nordic-Swan standard).

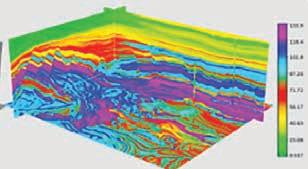

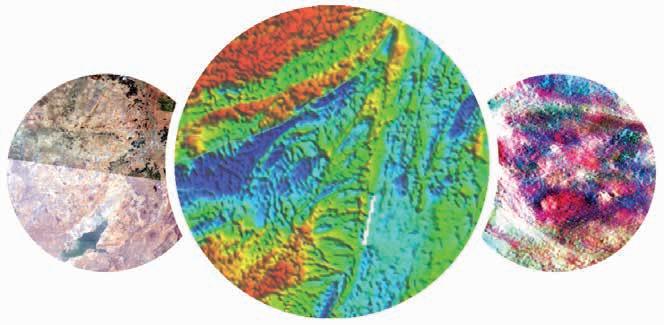

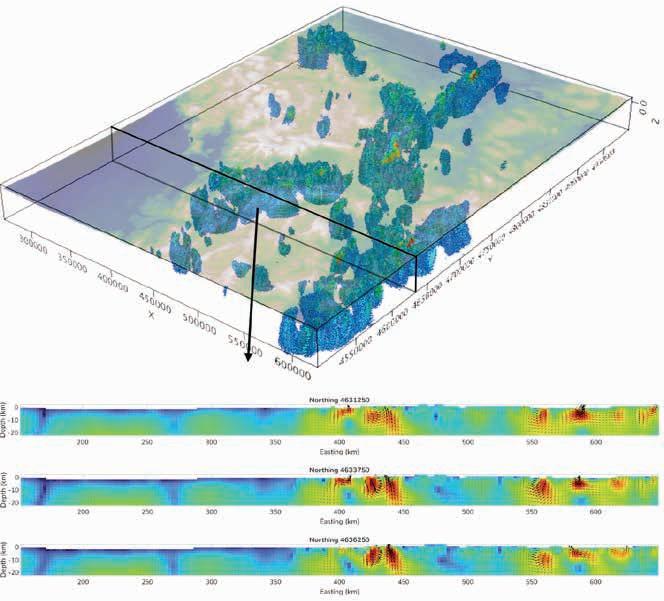

Predictive geoscience: Machine learning integrating Globe, gravity, magnetics, and remote sensing data

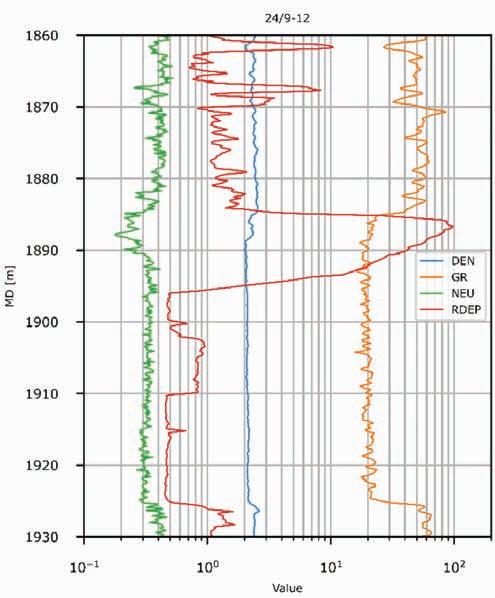

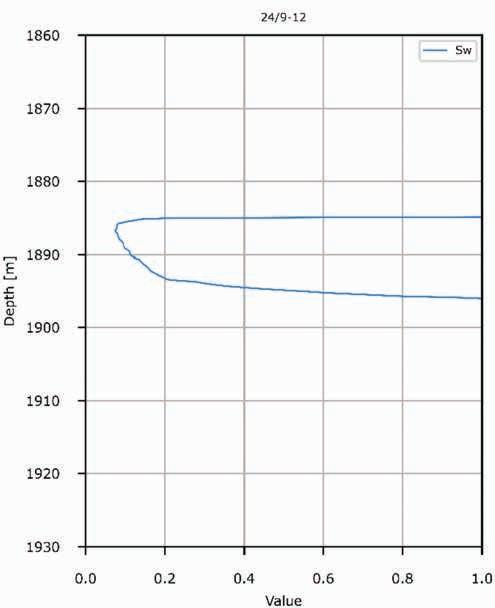

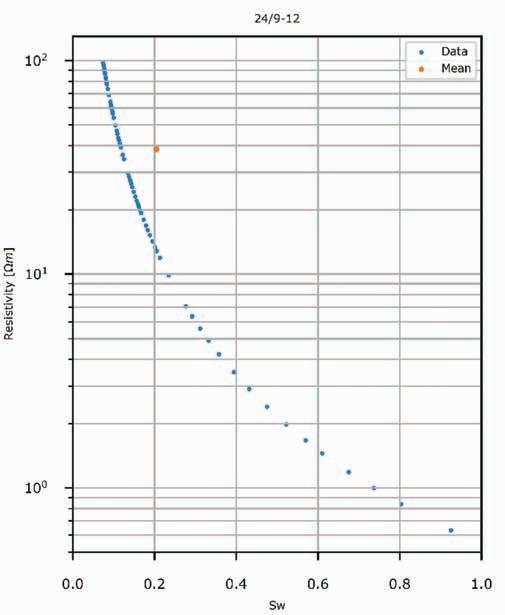

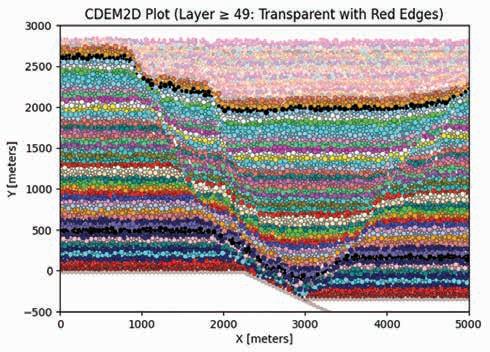

29 Reservoir resistivity modelling for CSEM interpretation and model building

Daniel Baltar Pardo

35 From Discrete Element Method (DEM) to 2D synthetic seismic modelling

Roderick Perez and Stuart Hardy

Special Topic: Digitalization / Machine Learning

43 Sinkhole detection through multi-component seismic monitoring

Tagir Galikeev, Tom Davis and Steve Roche

49 Predictive geoscience: Machine learning integrating Globe, gravity, magnetics, and remote sensing data

Samuel Cheyney, Ross Small, Catherine Hill and John Clark

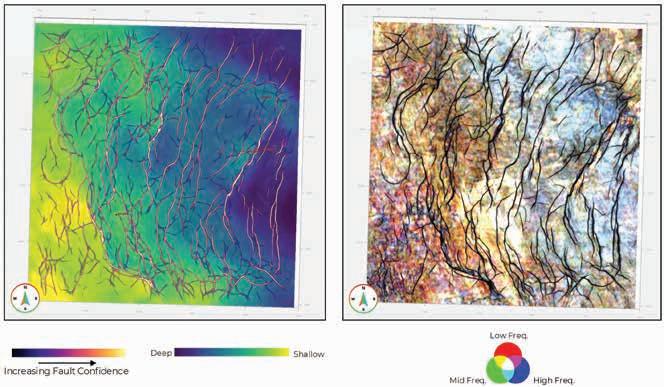

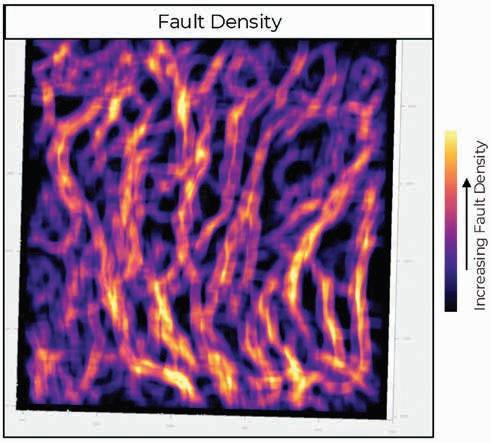

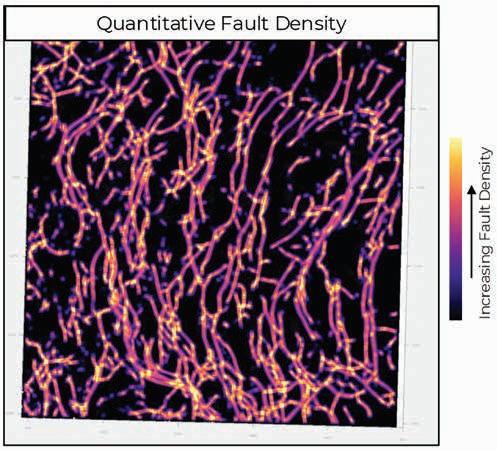

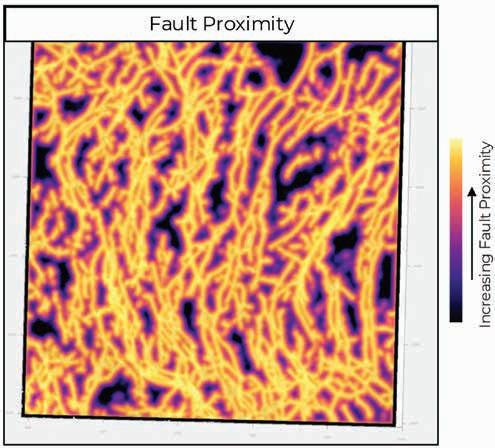

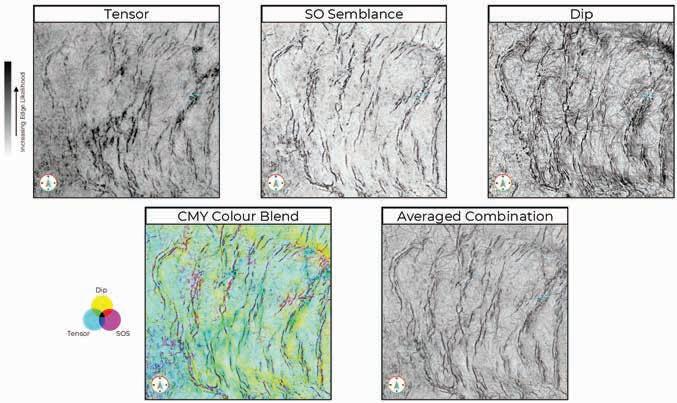

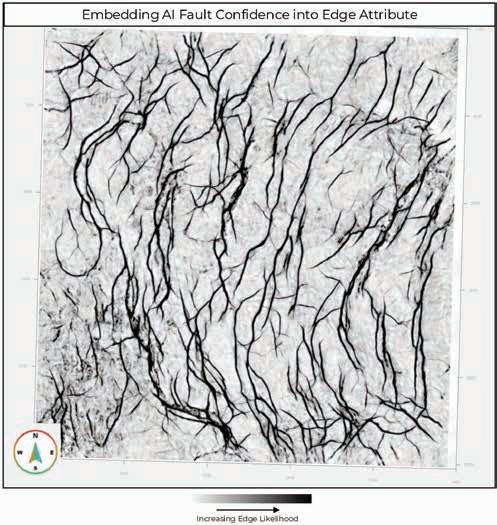

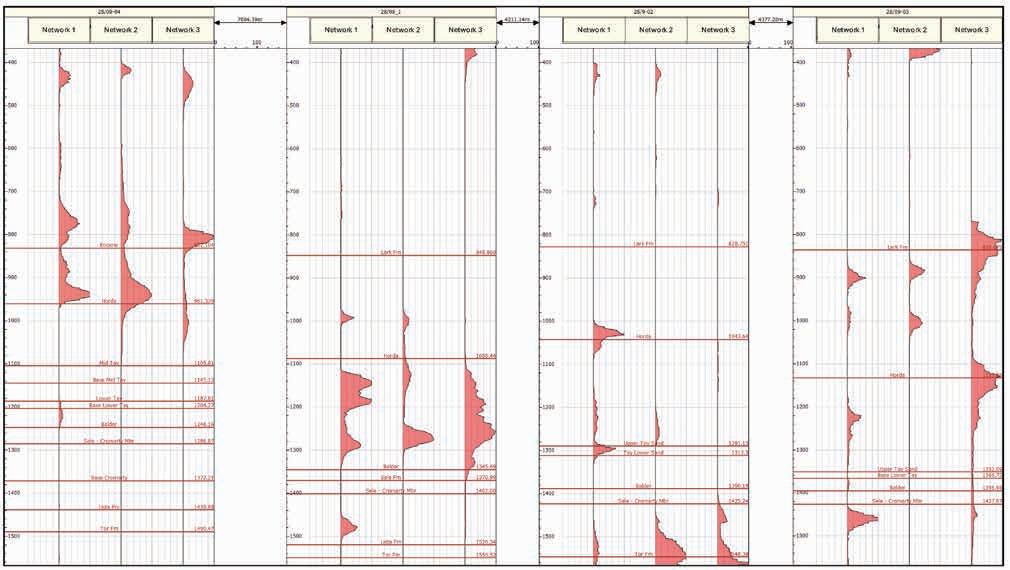

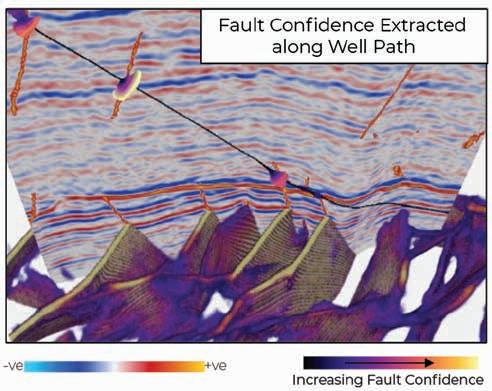

55 Derisking structural interpretation and well planning with a multi-network AI fault workflow

Ciaran Collins and Abdulqadir Cader

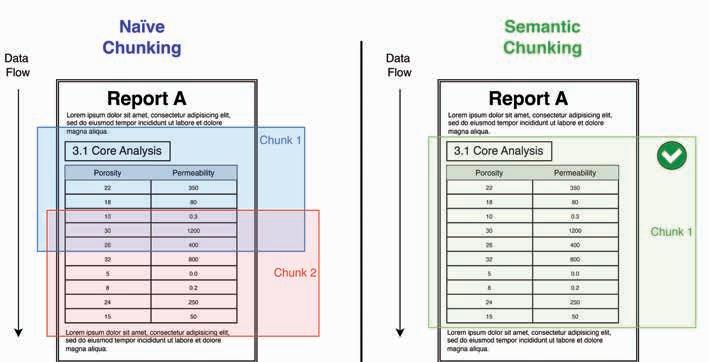

63 From ‘text soup’ to a trusted AI foundation; semanticising OSDU data for a multi-attribute future

Dr Thibaud Freyd and Dr Raphael Peltzer

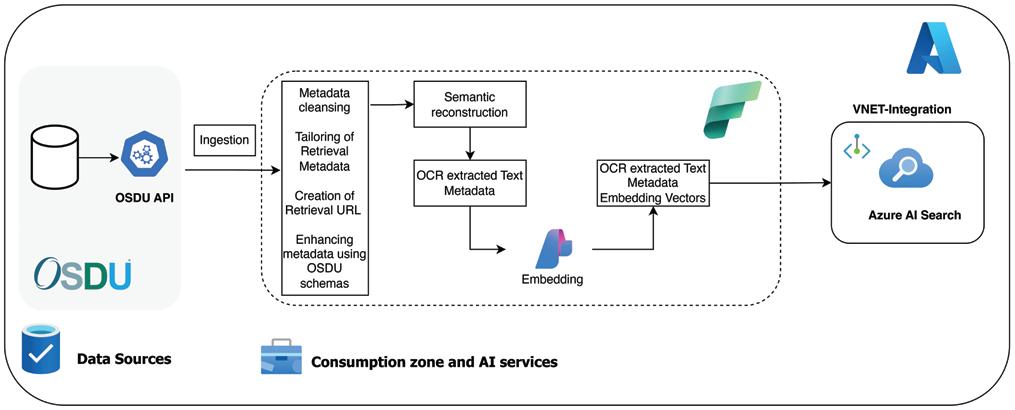

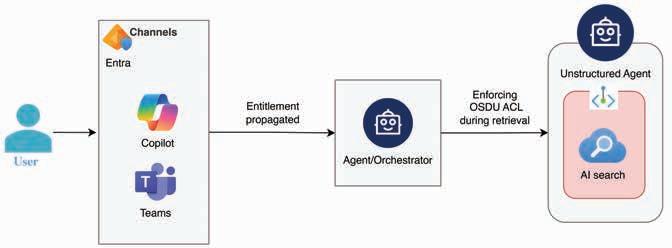

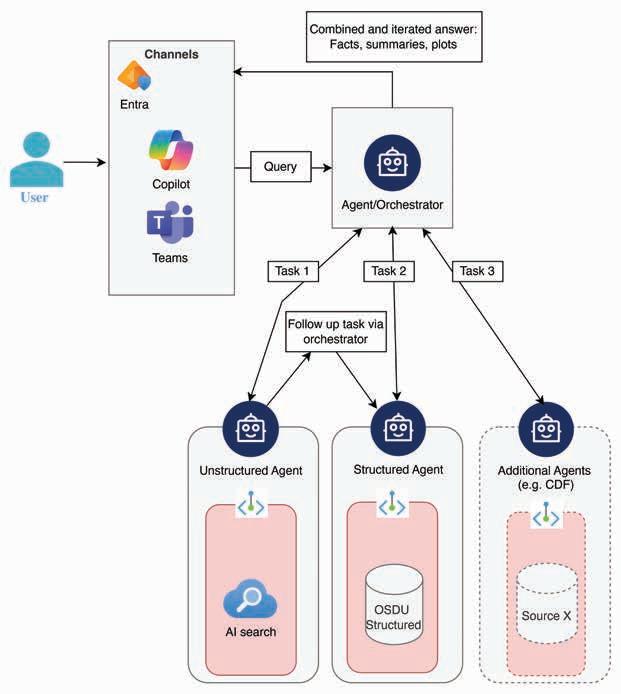

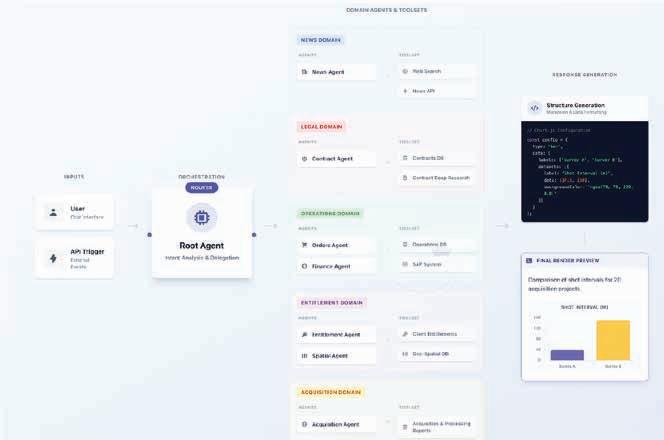

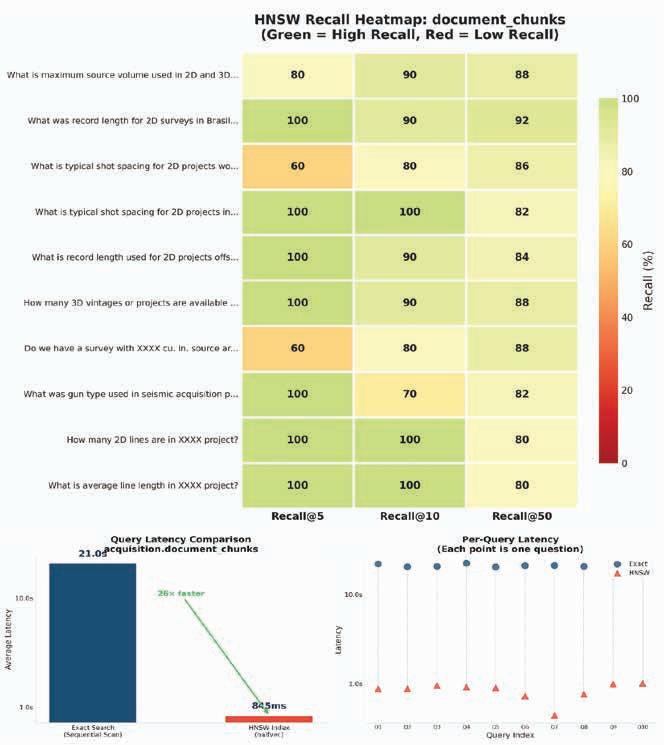

71 From metadata to embeddings: enabling agentic AI for subsurface intelligence

B. Lasscock, D. Arunabha, L. Chen, M. Gajula, K. Gonzalez, C. Liu, B. Michell, S. Namasivayam, V.S. Ravipati, A. Sansal, M. Sujitha, G. Suren and A. Valenciano

Feature: Minus CO2

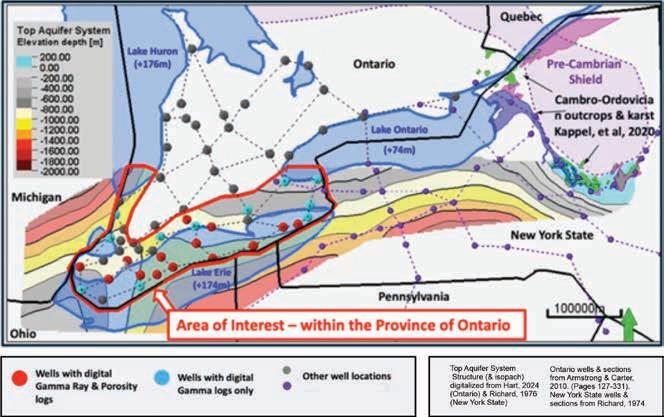

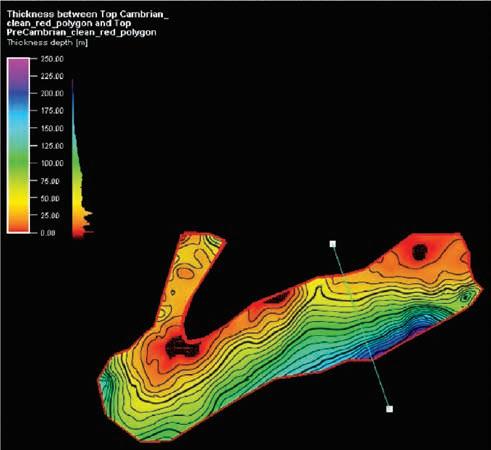

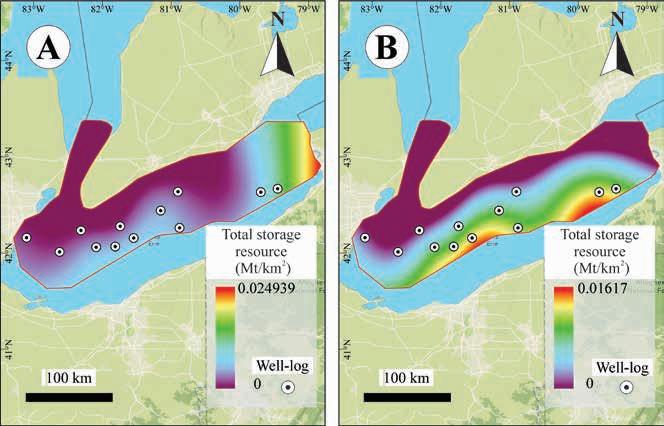

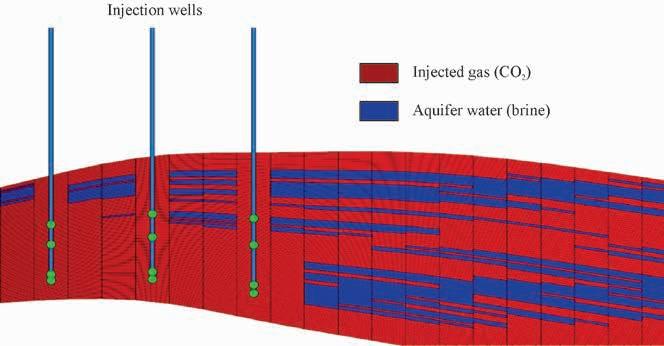

79 Minus CO2 Challenge 2025 – Student teams tackle carbon storage and energy storage in Cambro-Ordovician saline aquifer systems in North America and worldwide

Sofia Damaris Alvarez Roa, Md Arhaan Ahmad, Guillaume Bayvet, Aymeric Besnard, Nikhil S. Deshmukh, Eliott Gallone, Juan Sebastián Gómez-Neita, Angélica González Preciado, Ángela Mishelle Ramos Pulido, Lopamudra Sharma, Juan Esteban Tamayo Sandoval, Julie Vieira and Abhinav Vishal

86 Calendar

cover: Abstract circuit board design with glowing lines and digital network concept. This month we explore the latest innovations in digitalization/machine learning.

Environment, Minerals & Infrastructure Circle

Andreas Aspmo Pfaffhuber Chair

Florina Tuluca Vice-Chair

Esther Bloem Immediate Past Chair

Micki Allen Liaison EEGS

Martin Brook Liaison Asia Pacific

Ruth Chigbo Liaison Young Professionals Community

Deyan Draganov Technical Programme Representative

Madeline Lee Liaison Women in Geoscience and Engineering Community

Gaud Pouliquen Liaison Industry and Critical Minerals Community

Eduardo Rodrigues Liaison First Break

Mark Vardy Editor-in-Chief Near Surface Geophysics

Oil & Gas Geoscience Circle

Johannes Wendebourg Chair

Timothy Tylor-Jones Vice-Chair

Yohaney Gomez Galarza Immediate Past Chair

Alireza Malehmir Editor-in-Chief Geophysical Prospecting

Adeline Parent Member

Jonathan Redfern Editor-in-Chief Petroleum Geoscience

Robert Tugume Member

Anke Wendt Member

Martin Widmaier Technical Programme Officer

Sustainable Energy Circle

Giovanni Sosio Chair

Benjamin Bellwald Vice-Chair

Carla Martín-Clavé Immediate Past Chair

Emer Caslin Liaison Technical Communities

Sebastian Geiger Editor-in-Chief Geoenergy

Maximilian Haas Publications Assistant

Dan Hemingway Technical Programme Representative

Carrie Holloway Liaison Young Professionals Community

Adeline Parent Liaison Education Committee

Longying Xiao Liaison Women in Geoscience and Engineering Community

Martin Widmaier Technical Programme Officer

SUBSCRIPTIONS

First Break is published monthly online. It is free to EAGE members. The membership fee of EAGE is € 90.00 a year including First Break, EarthDoc (EAGE’s geoscience database), Learning Geoscience (EAGE’s Education platform) and online access to a scientific journal.

Companies can subscribe to First Break via an institutional subscription. Every subscription includes online access to the full First Break archive for the requested number of online users.

Orders for current subscriptions and back issues should be sent to First Break B.V., Journal Subscriptions, Kosterijland 48, 3981 AJ Bunnik, The Netherlands. Tel: +31 (0)88 9955055, E-mail: corporaterelations@eage.org, www.firstbreak.org.

First Break is published by First Break B.V., The Netherlands. However, responsibility for the opinions given and the statements made rests with the authors.

EAGE is 75 years old this year, and we want you to help us celebrate the anniversary.

To mark this historic occasion, we are launching a special publication at the EAGE Annual in June. It will tell the story of how the Association has developed since 1951 reflecting the technological advances during this period, and where we may be heading in the future.

That story cannot be told without including some record of the experiences of members. We would like to invite members to write in with any special memories they have of the Association, maybe recounting how our geoscience community and its activities have helped

to support your professional career, or even an amusing anecdote.

Whatever the case, you should keep your text to one or two paragraphs, so we can include as many contributions as possible. And we would also invite you to send in any relevant photos as we intend this to be a highly illustrated coffee table style publication.

Our hope is that the publication can have a lasting shelf life as an accessible record of our Association and its contribution to the scientific community and society in general. We see industry and academia able to use the book for pro-

motional and recruitment purposes, while members can show family and friends what their profession involves.

The EAGE team is very excited to get this project underway, so we encourage everyone with a story to share to write in as soon as possible.

Please email our publications manager Hang Pham at hpm@eage.org with your memories and questions if you have any.

For those interested in the sponsorship and advertising opportunities available for this unique publication, contact corporaterelations@eage.org.

Convenors Mohammad Nooraiepour (University of Oslo) and Isabelle Kowalewski (IFPEN) report on the contribution of geochemistry to the EAGE Annual 2025 programme.

The EAGE-EAG Geochemistry Technical Committee marked a significant milestone at the 86th EAGE Annual Conference in Toulouse, France, presenting two major sessions that underscored geochemistry’s pivotal role in addressing climate change and enabling the energy transition. Folllowing participation at the conference, we want to highlight the events that were valuable for the Geochemistry Technical Community.

Workshop on science and climate action

Our workshop on ‘Geochemistry’s role in advancing climate change and energy transition research’ brought together leading researchers to tackle critical challenges on the path to carbon neutrality by 2050. The morning session showcased groundbreaking methodological advances, including adaptations of the Rock-Eval method for studying carbon dynamics and storage mechanisms, as well as innovative applications of clumped-isotope analysis to enhance our understanding of atmospheric gases such as methane, with direct implications for emission-reduction policies.

The afternoon CO2 removal session explored diverse technological frontiers: CO2 mineralisation through carbon capture and storage, subsurface gas storage optimisation, soil carbonation utilising clay-rich waste materials, and fracture dynamics in mafic formations. Presentations highlighted cutting-edge techniques, including water-alternating-gas injections in reactive reservoirs, bioengineered solutions, and advanced subsurface fluid analysis for storage site selection. The workshop concluded with a comprehensive comparative review

of CO2 balances across global storage solutions, presented by C. Turich from the IEA.

The committee introduced its inaugural Dedicated Session on ‘Reactive flow and transport in porous media’, a landmark addition to the Technical Programme that brought geochemistry and porous media sciences to the forefront. Convened by Mohammad Nooraiepour (University of Oslo), Mohammad Masoudi (SINTEF), and Sylvain Thibeau (TotalEnergies), the session addressed the fundamental mechanisms governing subsurface systems critical to climate mitigation and energy innovation.

The session’s structure reflected the dual nature of contemporary subsurface challenges. The morning programme concentrated on CO2-induced salt precipitation during injection into saline aquifers, a phenomenon with profound implications for injectivity, storage capacity and containment integrity. NORCE researchers offered insights on non-isothermal wellbore-reservoir coupling for reliable CO2 injectivity estimation, followed by a contribution by Ali Papi (Heriot-Watt University) presenting dissolved-water CO2 injection as a salt precipitation mitigation strategy. Karol Dąbrowski (AGH University of Krakow) demonstrated microfluidic experimental approaches to understanding salt precipitation dynamics, while Nooraiepour examined the geomechanical implications of CO2-induced salt formation in sandstone reservoirs.

The second half broadened to encompass thermal-hydrological-mechanical-chemical (THMC) processes across diverse subsurface storage applications. Stéphane Polteau (Institute for Energy Technology) revealed insights into fluid connectivity in continental-margin basalt sequences using strontium isotopes. Olga Dufour (TotalEnergies) presented dynamic simulations of fault reactivation in caprock from the Mont Terri experiment, and Benjamin Emmel (SINTEF) concluded with

hydrogen exposure experiments on Zechstein 2 samples, highlighting the expanding frontier of underground hydrogen storage.

What distinguished this dedicated session was its comprehensive integration across scales and disciplines, from porescale microfluidic observations to fieldscale reservoir simulations. The presentations spanned experimental, numerical, and theoretical approaches, fostering dialogue between academia and industry on challenges including reactive transport model scalability, uncertainty quantification in coupled processes, and the development of innovative characterisation techniques.

Geochemistry emerged not as an isolated discipline, but as an indispensable tool for solving subsurface engineering problems. Whether addressing salt precipitation that threatens CO2 storage efficiency, mineral scaling in geothermal systems or fault reactivation risks in caprocks, the session demonstrated that geochemical processes are the invisible forces shaping outcomes in our transition to low-carbon energy systems.

Building on this momentum, we invite the wider EAGE community to participate in our Dedicated Session ‘Geochemistry and low carbon minerals’, being planned for the 87th EAGE Annual Conference in Aberdeen, UK.

For researchers exploring cutting-edge science, practitioners seeking operational insights or early-career professionals entering this transformative field, the Geochemistry Technical Community offers a platform where fundamental discoveries meet urgent global challenges. Join us in advancing the science that will enable safe, efficient, and sustainable stewardship of Earth’s subsurface resources.

Connect with the EAGE-EAG Technical Community on Geochemistry

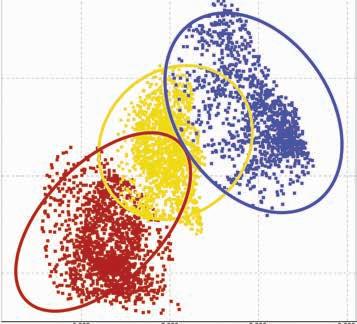

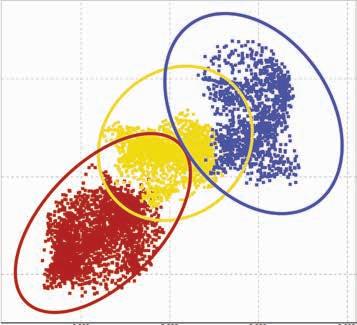

Conventional Workflow

TIME PROCESSING, DEPTH IMAGING AND AVA INVERSION

Vp/Vs

USING FIELD-DATA INPUT

SCATTER = LESS UNCERTAINTY!

Quantitative interpretation requires true amplitudes and high signal-to-noise ratio.

DUG Elastic MP-FWI Imaging eliminates the need for conventional time processing, depth imaging and AVA inversion workflows, along with their assumptions that ultimately affect AVA compliance. With DUG Elastic MP-FWI Imaging more certain predictions can be realised — all using field-data input. Brilliant!

info@dug.com | dug.com/fwi

Now in its ninth edition, the HPC Workshop has once again proven to be a window into the world of advanced supercomputing and artificial intelligence technologies and their applications in various fields of geoscience. As in all eight previous editions, the ninth workshop, held in Barcelona on 6-8 October, attracted a vibrant mix of representatives from industry and academia.

High-performance computing remains a key enabler for energy research and applications, as Keith Gray (TotalEnergies) stated in the first keynote speech.

The intersection of HPC and AI was the focus of much discussion. As Dan Stanzione, director of the Texas Advanced Supercomputing Centre in Austin, noted during his keynote speech, massive investments in AI data centres are polarising the market, both in terms of technology and market availability. For example, while double precision has always been a requirement for many applications in conventional HPC, it is well known that AI models do not require this level of computational accuracy. As a result, we are starting to glimpse a future where native double-precision computing units will no longer be a part of the landscape. At the same time, geoscientists are beginning to see an opportunity in trying to use an abundance of very fast low-precision units, together with low-precision floating point numbers that require less memory and bandwidth, to speed up conventional algorithms. Many presentations and discussions have focused on this topic; the path forward is not yet entirely clear, but the signs of progress in this direction are clear and evident. Moreover, the impact of machine learning is not limited to computing architecture, since at the software and application level generative and agentic AI are now realities that the energy world must also deal with, and were the topic of a panel discussion moderated by Matteo Ravasi (Shearwater GeoServices), with the participation of Mik Isernia (Think Onward), Gareth O’Brien (Microsoft), Tariq Alkhalifah (KAUST), and Fabrice Dupros (AMD).

As always, performance and performance analysis matter, and were the

topic of the opening speech by Jesus Labarta from Barcelona Supercomputing Centre and several other presentations. Meanwhile, Eni presented its recently deployed new supercomputer, HPC6. Cloud computing was another hot topic, with John Brittan (TGS) delivering a keynote speech outlining how his company is ready to fully transition from on-prem to the cloud. Software engineering has played a very important role in enabling

this transition, as cost efficiency in the cloud is necessarily achieved by leveraging interruptible spot instances, which introduce an element of unpredictability into execution that can only be managed by increasing the complexity of the job orchestration engine. The key role of software engineering was echoed in many other presentations, with particular attention on abstraction in domain-specific languages or Python wrappers around high-performance legacy Fortran kernels.

As per tradition, this year’s participants also had the opportunity to visit a data centre thanks to the availability

and kind collaboration of the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre, which offered the possibility to see the MareNostrum 5 supercomputer (a 250 PFlops peak performance system, currently number 14 in the top 500) and its new quantum computer deployed in 2025.

The novelty of the ninth edition of the HPC workshop was the coincidence with the second edition of the data processing workshop, which also took place in Barcelona at the same venue. The programme included a joint session between the two workshops entitled ‘Leveraging the computing revolution in the AI era’. The joint session was opened by Edmondo Orlotti (Core42), who further focused on the challenges, but also opportunities, for HPC in the era of artificial intelligence. Among the opportunities, in a landscape of accelerators increasingly evolving towards the requirements of artificial intelligence, Edmondo mentioned the affordability of custom silicon as a possible alternative to accelerate HPC applications. Still on the opportunity side, Flaurent Pautre (Viridien) discussed the application of large language models to software engineering, and Matteo Ravasi talked about the impact of AI hardware on geophysical computational methods. Finally, Bertrand Duquet (TotalEnergies) showed several applications of HPC to seismic imaging, reminding the audience that seismic imaging remains the main user of HPC in the field of geosciences and geophysical data processing.

The ninth edition of the workshop provided a further opportunity for updates, the exchange of information and experiences, and stimulating discussions on the topic of high performance computing. A big thanks goes to the organisation and the technical committee. The next event is scheduled for 2027, with the tenth edition.

Report from the 2nd EAGE Data Processing Workshop held jointly with the 9 th EAGE High Performance Computing (HPC) Workshop on 6-8 October 2025 in Barcelona, Spain.

Building on the success of the 1st Data Processing Workshop held in Cairo in February 2024, the latest edition brought a broader scope, deeper technical content and a strong collaborative structure made possible by its co-location with the well-established EAGE HPC series.

Barcelona served as an ideal host city, allowing us to leverage the opportunity of visiting the world-leading Barcelona Supercomputing Centre (BSC) as a central highlight. The joint event marked a major milestone in EAGE’s ongoing efforts to integrate geoscience innovation, HPC evolution and frontier technologies such as AI and earth observation (EO).

The organising committees for both workshops designed the 2025 edition with the clear intention to expand the thematic reach of data processing beyond seismic into EO and cross-domain applications; enhance collaboration between the seismic processing and HPC communities; leverage Barcelona’s technological infrastructure, particularly the BSC, to offer practical, real-world insight into next-generation computing capabilities; and strengthen networking through joint sessions.

Keynote talks from Prof Kees Wapenaar (TU Delft), Song Hou (Viridien), Claudio Strobbia (Realtime Seismic) and Bertrand Duquet (TotalEnergies) anchored the programme with visionary perspectives on multi-domain data processing, innovative AI workflows, and the growing potential of seismic-HPC integration.

Three sessions, dedicated to Challenges and enhancements in velocity model building and leaning heavily on the power of FWI, provided a comprehensive overview of advances in FWI, velocity model building strategies and AI-supported imaging enhancement in detail. Subjects covered practical implementations of multi-parameter FWI, managing parameter trade-offs, cross-talk, and sensitivity issues, the role of frequency content in

elastic property recovery and data-driven methods for post-imaging refinement.

The closing discussion centred on whether velocity model building should lean more toward physics-based models, data-driven techniques or hybrid approaches. As always, comments rang true with regards to starting a velocity model especially when moving to elastic applications. It was agreed that all approaches hold value depending on geology, dataset characteristics and the end goal.

One of the most anticipated components was the guided tour of the BSC, home to some of Europe’s most powerful supercomputers. The visit highlighted the architecture and operation of top-tier HPC systems; management of massive geoscience workloads; emerging technologies in AI-accelerated computation; sustainability and energy-aware computing initiatives; and next-generation quantum computing.

The programme included the firstof-its-kind panel session exploring the growing role of satellite EO in geoscience moderated by Giovanni Sylos Labini of Planetek Italia. Topics covered included emerging satellite missions and evolving sensor technologies; cross-domain applications spanning resource exploration, monitoring, and environmental assessment;

integration of EO data with traditional geophysical workflows; and opportunities for cross-fertilisation between seismic and non-seismic data domains. The panel was widely praised for bringing fresh perspectives into the data processing community and for highlighting the practical value of EO in broad geoscientific practice.

Another novel element of the joint event was the Computing revolution session. Setting the scene was Edmondo Orlotti, chief strategy officer of Core42. This session brought together specialists from both workshops to explore HPC for scaling AI models, architecture-aware algorithm design, deployment challenges and the interoperability between seismic data pipelines and advanced hardware. AI-driven computational strategies and strong community synergy were evident.

The session on Advancements and future direction of AI/ML underscored the rapidly evolving digital strategy within geoscience disciplines. Song Hou led the charge with a keynote on Transforming geoscience workflow with generative AI, advocating for harnessing unstructured data to enhance processing and QC. Across the session, the community recognised both the potential and challenges of AI, particularly the demand for high-quality training data, computational load management, tight alignment with HPC architectures, and the mismatch between generic synthetic datasets and unique geological settings. Questions about computational overhead and data usage were also raised.

Bringing the workshop to a conclusion was the session on Processing applications for the Energy Transition. This session focused on seismic data processing for carbon capture and storage (CCS), geothermal systems and shallow-hazard mitigation allowing comparison of methodological robustness and the added value of cross-fertilisation across different conditions.

EAGE Digitalization Conference and Exhibition 2026 is gearing up for a packed conference. The strategic and plenary programme will address a broad range of organisational and leadership issues related to digital innovation in energy.

The programme features some distinguished keynote speakers. Paula Doyle, chief digital officer, Aker BP, will be speaking on ‘Agentic workflows – why and how?’; Allison Gilmore, product management director, S&P Global Energy, will be speaking on ‘AI for subsurface: Early impacts and broader potential’; and Josh Etkind, CEO, ThinkOnward, will be speaking on ‘Decisions, not demos: Human + AI operationalised at any scale. More keynote speakers are due to be added to the programme.

The conference agenda also features a wide range of panel discussions, including one titled: ‘Adoption at scale: Why digital transformation still fails – and how

to finally make it stick’. Panellists for this session will be Dr Milos Milosevic (senior director of strategy, Halliburton-Landmark), Gautier Baudot (director div exploration excellence transformation, TotalEnergies), Karen Czachorowski (digital technology lead, Aker BP), Jan Eivind Danielsen (Digital strategist & business transformer, Cognite), and Einar Landre (lead digital architect, Equinor).

Another highlight will be ‘Data readiness for AI subsurface workflows: Trust, quality and efficiency’. This roundtable discussion consists of five industry experts, Ingrid Sternhoff (ops digital ecosystem manager, Aker BP), Dr Julianna Toms (director computational science & engi-

neering, Halliburton-Landmark), Mathieu Terrisse (manager, data, digital, innovation exploration, TotalEnergies), Dani Alsaab (senior product manager, AspenTech) and Petter Dischington (project coordinator for data management strategy, SODIR).

These are a few examples of what awaits attendees in Stavanger, Norway at EAGE Digital 2026. You can gain firsthand key industry insights and explore topics such as AI innovation, navigating the hybrid reality, driving value with OSDU, AI operationalisation and much more.

Registration is open. Visit www.eagedigital.org for a detailed overview on more panel discussions, keynote speakers and roundtable discussions.

Convenors Jeanne Vidal (WING) and Thomas Mooij (PanTerra) report on the key highlights from the dedicated session ‘From Mines to megawatts: Geothermal heat, storage, and sustainable energy’ hosted by the EAGE Technical Community on Geothermal Energy at EAGE GET 2025.

The dedicated session explored how mine water geothermal systems are evolving from niche research topics into operational, large-scale components of regional energy strategies. Featured were four experts: Elke Mugova (Fraunhofer IEG and WIM Germany), Virginie Harcouët-Menou (VITO), David Townsend (TownRock Energy), and Falco van Driel (Mijnwater). Projects showcased during the session revealed a growing sector driven by both technological innovation and the pressing political need for decarbonised heating.

Mine water geothermal systems offer a unique convergence of strengths at a moment when Europe urgently needs clean alternatives for heating and cooling. The advantages are compelling.

Flooded mines provide extensive, naturally warm water bodies (temperatures typically 12 °C to 30 °C), ideal for coupling with heat pumps. Existing shafts and galleries reduce development costs, while the vast subsurface voids hold enough thermal capacity to support both heating and cooling production, and long-duration thermal energy storage on a seasonal scale.

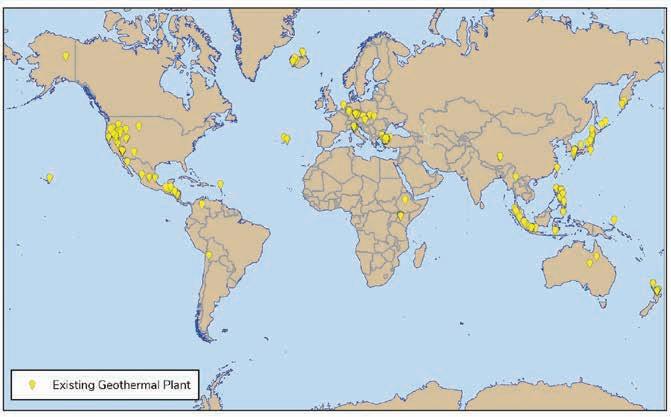

Today, Europe counts more than 50 operational mine geothermal systems, around 60 in various stages of planning or study, and only a handful ever decommissioned. Many of the existing plants have operated for decades, demonstrating resilience, reliability and long-term economic viability. For regions affected by mine closures, this technology represents not only an energy solution but also a socio-economic renewal pathway.

When mining activities stop, groundwater progressively floods the excavated voids. Over time, the water temperature equilibrates with that of the surrounding rock through the natural geothermal gradient, creating large volumes of water with stable temperatures. These easily accessible reservoirs can then be harnessed for thermal energy production and storage. Heat and cold can be extracted through several configurations, e.g., open or closed loop systems.

Heat pumps elevate the temperature for district heating networks, while the cooled water is reinjected, allowing the system to function as a continuous geothermal cycle. When cooling is needed, the process reverses. For municipalities striving to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, these systems offer predictable performance and a level of scalability rare among renewable heating technologies.

Beyond heat production, mines can also act as seasonal thermal batteries. Through mine thermal energy storage (MTES), excess heat can be stored for later use, optimising renewable energy integration.

Across Europe, a diverse portfolio of research pilots and industrial-scale systems illustrates how rapidly mine water geothermal is advancing.

On the research side, the EU-funded project PUSH-IT seeks to bridge the mismatch between heat availability and demand through large-scale seasonal thermal storage. One of the demonstrators is located in Bochum (Germany), where researchers are developing a MTES system beneath a dense energy campus that hosts a data centre, a CHP unit, and cooling towers. After the drilling of the 120 m deep first well in 2024 and extensive geophysical and hydrogeological investigations, four additional boreholes will be installed between 2025 and 2026 to test circulation, storage efficiency and long-term performance. A detailed numerical model and an active engagement programme support this effort to become one of Europe’s first large-scale MTES demonstrators.

In Wallonia (Belgium), where extensive abandoned coalfields shape the regional landscape, feasibility studies funded by the Walloon government have recently been conducted to identify the most promising sites to host a mine water geothermal pilot project. Led by VITO in collaboration with the universities of Mons and Liège, the studies covered the three main coal basins, namely, the basins of Charleroi, couchant de Mons and Liège. The assessments included subsurface mapping of the mine workings and infrastructures, demand and production scenarios modelling as well as stakeholder engagement. The MontLégia Hospital and the LégiaPark district emerged as ideal prosumers for a fifth generation heating and cooling concept coupling mine water heat extraction with seasonal storage. A government decision is expected in 2026. If successful, this will become the first operational mine water geothermal installation in Wallonia, marking the beginning of a regional strategy for mine-based sustainable heating.

Further north, the Galleries to Calories (G2C) project, funded by Geothermica, explores how mine workings can support heat

storage and transfer in Scotland, Ireland and the USA. The initiative is evaluating the feasibility of an underground ‘geobattery’ near Edinburgh, capable of storing surplus heat from industrial activities and releasing it during peak demand, offering an example of hybrid geothermal-storage systems adapted to industrial settings.

The industrial sector is also gaining momentum. In the UK, more than a decade of subsurface mapping and pilot schemes has paved the way for the first large operational mine water geothermal district systems. Lanchester Wines operates two privately funded mine water heating schemes in Gateshead, NE England since 2018, delivering 3.6 MW of heating to neighbouring commercial warehouses. Nearby, the Gateshead Energy Company scheme, operational since 2023 with 6 MW of installed capacity, shows how municipal heat networks can rely on mine water to support large-scale district heating.

The Netherlands continues to be a pioneer through the long-standing Mijnwater Heerlen project, one of Europe’s most successful transformations of abandoned coal mines into a regional low-temperature energy infrastructure. What began in 2008 as a pilot district heating and cooling system has evolved into Mijnwater 2.0, a smart fifth generation thermal grid built around principles of energy exchange, decentralised demand-driven operation and large-scale seasonal storage within mine reservoirs. In Mijnwater’s approach, heat from data centres and industry is already used. Future possibilities are to integrate heat from other sources such as solar collectors and buffer systems. A wide range of other heat sources can be implemented as well, making systems like Mijnwater’s a strong option for using waste heat. Today, the system serves over 1000 homes and 250,000 m² of commercial space, with a plan to quadruple capacity by 2030.

Together, these initiatives illustrate a rapidly expanding European mine geothermal ecosystem, spanning from research to commercial deployment. They demonstrate that mine water geothermal is now a validated, scalable pathway to clean heating, energy storage and regional resilience.

Developing a mine geothermal system requires harmonising three distinct layers of complexity.

Subsurface integration: Successful development depends on detailed characterisation of mine geometry, flow pathways,

fracture networks, and the potential presence of methane or other gases. Hydrogeological modelling helps predict both performance and long-term stability.

Drilling and access: Reaching flooded galleries may require directional or horizontal drilling with deflection risks and unpredictable geological conditions. Real-time monitoring, adaptable drilling strategies and improved downhole imaging technologies are increasingly seen as essential tools for reducing uncertainty.

Surface infrastructure: The design must accommodate district heating integration, intermittent demand and spatial constraints, particularly in dense urban areas. Many projects demonstrate the advantages of placing components underground or within existing structures to save space and enhance visual acceptance.

In regions shaped by mining history, public perception is pivotal. Transparent communication about risks, monitoring strategies, and expected benefits is essential for trust-building.

Successful projects consistently emphasise early and sustained stakeholder involvement: national and local policies, environmental agencies, former mining authorities, private investors, and local residents all play a crucial role in decision-making. This collaborative governance model is increasingly recognised as a prerequisite rather than an optional step.

The relevance of mine geothermal extends far beyond Europe. Regions such as Appalachia in the United States, the coalfields of China, copper mines in South America, and mining districts in South Africa and Australia possess similar subsurface conditions. Knowledge transfer, especially around policy frameworks, drilling methods and community engagement could accelerate adoption worldwide.

Another emerging frontier lies in co-developing geothermal systems within active mines, enabling energy recovery or storage even before closure. This approach represents a new paradigm in

which mining and renewable energy production evolve together rather than sequentially.

Building an international network of researchers, municipalities, regulators, and citizen groups would strengthen innovation, reduce duplication of efforts and promote a just transition for mining regions globally.

Several lessons emerge clearly from the projects showcased. First, a solid hydrogeological understanding remains the cornerstone of any successful mine geothermal development. Precise knowledge of mine architecture, water flows and thermal regimes allows developers to optimise system design, anticipate operational behaviour and minimise risks. Second, continuous engagement with national and local policies, regulators, environmental agencies, and local communities is fundamental. These systems succeed not only because they are technically sound, but because they are socially anchored and institutionally supported.

An innovative mindset is equally important. Operating a mine water energy system involves navigating legacy infrastructure, adapting drilling strategies to complex underground conditions and integrating new technologies from downhole heat exchangers to smart district energy networks. Best practices, transparent communication and operational flexibility consistently prove decisive in delivering reliable systems.

This dedicated session reaffirmed that abandoned mines are more than geothermal reservoirs: they are exceptional assets for underground thermal energy storage. Their scale, accessibility and hydraulic connectivity make them ideal for storing surplus heat or cold and redistributing it across seasons or neighbourhoods. In some regions, mines can also serve as conduits for thermal transport, transforming the subsurface into an active component of district-scale energy management.

Connect with the EAGE

Geothermal Energy Community

• FLOW MECHANICS FOR GEOLOGICAL CO2 STORAGE – BY FLORIAN DOSTER

• RISK ASSESSMENT OF CO2 STORAGE BY UNDERSTANDING COUPLED THERMOHYDRO-CHEMICAL-MECHANICAL PROCESSES –BY ANDREAS BUSCH AND ERIC MACKAY

• CO2 STORAGE PROJECT DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION (SALINE AQUIFERS) –BY PHILIP RINGROSE PARIS, FRANCE GEOLOGICAL CO2 STORAGE MASTERCLASS

Every month we highlight some of the key upcoming conferences, workshops, etc. in the EAGE’s calendar of events. We cover separately our four flagship events – the EAGE Annual, Digitalization, Near Surface Geoscience (NSG), and Global Energy Transition (GET).

First EAGE/ALNAFT Workshop – Unlocking hydrocarbon potential of the West Mediterranean offshore frontier basin of Algeria

11-13 May 2026 – Algiers, Algeria

This dedicated technical forum offers a unique platform to explore emerging geological models, frontier exploration challenges and innovative technologies relevant to Algeria’s offshore domain. Through in-depth technical sessions, case studies and interactive discussions, participants will gain practical insights and engage directly with peers and decision-makers. Be part of this important exchange of knowledge and experience and secure your place at a workshop shaping the future of offshore hydrocarbon exploration in the West Mediterranean.

Early Registration Deadline: 5 April 2026

Second EAGE/ALNAFT Workshop on Techniques of recovery of mature fields and tight reservoirs

11-13 May 2026 – Algiers, Algeria

The workshop will focus on recovery challenges facing mature fields and tight reservoirs, where decades of production now demand innovative tertiary-recovery solutions. Discussions will address proven and emerging techniques applicable to brownfields, tight Cambro-Ordovician sands and complex carbonate plays highlighting how technology and tailored workflows can unlock remaining reserves. Bringing together operators, service companies, researchers, and regulators, the workshop offers a collaborative platform to share experience, evaluate opportunities, and advance recovery strategies under the theme ‘Move forward by recovering differently’.

Early Registration Deadline: 5 April 2026

9th EAGE Conjugate Margins Conference & Exhibition

27-31 July 2026 – St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

The Call for Abstracts is now open for this long-standing international forum bringing together industry, academia and government to advance the understanding of Atlantic conjugate margin systems. Nearly two decades after its inaugural meeting in 2008, the conference continues to showcase high-quality scientific and technical contributions. The 2026 edition will focus on Geodynamics and structural geology; Stratigraphy and depositional systems; Petroleum systems; Carbon sequestration; and New analytical methods. Special thanks to our Gold Sponsor DUG.

Abstract submission deadline: 22 March 2026

First EAGE/SBGf Workshop on Seismic Processing

23-24 September 2026 – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

This workshop is dedicated to advancing the full spectrum of seismic data processing, from pre-processing and signal conditioning to high-end imaging, inversion, and emerging applications in carbon capture and storage. Contributions are invited on topics areas such as pre-processing, signal conditioning and demultiple; velocity model building and full-waveform inversion (FWI); imaging and model-driven inversion methods; OBN processing and hybrid (OBN + streamer) workflows; time-lapse (4D) seismic processing and monitoring; machine learning, automation and workflow efficiency; and seismic processing for CCS and emerging energy applications.

Abstract submission deadline: 18 May 2026

Nominations are open for the Marie Tharp Sustainable Energy YP Award introduced in 2024 to support and recognise students that focus on energy transition disciplines. Candidates must be MSc and PhD students under 35 years old and pursuing a curriculum related to geoscience and engineering to support energy transition.

Applications are encouraged with the deadline of 31 March for submissions. The nomination package must include

a nomination letter by the applicant detailing their motivation for applying, highlighting their achievements, ongoing projects and plans to contribute to the advancement of energy transition and the work that the EAGE community does.

A CV and at least one letter of support from a technically qualified person that knows the nominee and their work, should be included in the package.

The award winner will receive a grant to attend the EAGE GET Conference in Hannover, Germany in November 2026 offering an opportunity to gain exposure and experience to the latest sustainable energy initiatives and network with industry experts and peers.

About the award and the nomination process

EAGE invites all active EAGE Student Chapters to take part in the Online GeoQuiz 2026, a live virtual competition designed for students to engage in geoscience knowledge and teamwork.

The Online GeoQuiz will be held live and virtually during mid March, allowing Student Chapters from around the world to participate simultaneously in an interactive and dynamic format.

As a reward, the three Student Chapters with the highest scores will each receive three free registrations to attend the EAGE

Annual Conference & Exhibition 2026, which will take place in Aberdeen, United Kingdom. Here, the teams will participate in the EAGE Global GeoQuiz and compete against other student participants.

We encourage all active Student Chapters to participate and showcase their knowledge while competing with peers from the global EAGE student community. The deadline to register is 28 February.

For information about the GeoQuiz 2026 please contact students@eage.org.

Winners have been announced for the Vlastislav Červený Student Prize, which recognises outstanding Bachelor (Bc) and Masters (MSc) theses in theoretical and applied geophysics in Central Europe. Established by Seismik, and now organised by the EAGE Local Chapter Czech Republic, the prizes commemorate the scientific legacy of Prof Vlastislav Červený and aims to support the development of early-career geoscientists.

In the MSc category, Angelin Mariam Binny of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat München (Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences) received the award for her thesis ‘Seismic response evaluation in six degrees of freedom: Insights from shake table experiment’, supervised by Dr Felix Bernauer. In

the Bc category, Jan Hohermuth of the Faculty of Science, ETH Zurich (Earth and Climate Sciences, Geology and Geophysics) received the award for the thesis ‘Measuring acceleration and rotation caused by tree sway using low-cost inertial motion sensors’, advised by Drs Cédric Schmelzbach and Alexis Shakas.

The winners (thanks to our main sponsor INSET and sponsors EAGE, Seismik, G Impuls Praha, and Charles University’s Faculty of Math and Physics and Faculty of Science) will receive €1000 and €500 (MSc and Bc, respectively), free EAGE student membership for 2026 and a voucher for an EAGE online learning course.

Honorary awards were accorded to Bohdan Rieznikov of Technical University of Ostrava (Faulty of el. Eng. and Computer Science) for the Bc thesis

‘Classification of seismic events using recurrent neural networks’ (advisor Dr Marek Pecha); Helena Simić of University of Vienna (Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy) for the MSc thesis ‘Seismic attenuation from seismic ambient noise recordings: application to short-term nodal deployment’ (supervisor Dr Götz Bokelmann); and Felix Schweikl of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat Munchen (Department of Statistics) for the MSc. thesis ‘Time series analysis for prediction of geomagnetic indices’ (supervisors Dr Fabian Scheipl, Dr Artem Smirnov and Dr Elena Kronberg) appreciating excellent statistical analysis of complex data and well written thesis.

Honorary award winners receive EAGE student membership for 2026 and an EAGE online learning course.

The French city of Montpellier hosted the 6th EAGE Borehole Geology workshop in the SLB Montpellier Technology Centre on 22-24 September 2025, attended by 80 participants from 20 countries representing different E&P companies (NOCs and IOCs), service companies, image interpretation consultants and universities.

A pre-event field trip organised around the city on 21 September focused on outcrops presenting complexities of structural geology making a majestic display. This focused the proceedings of the workshop with the theme of ‘Advancing borehole geology: Integrating multi-disciplinary approaches’.

Pascal Richard and Chris Wibberley led the field trip observing fractures and evidences of fluid circulation through them during basin evolution, while pointing to different fracture patterns from Permian wind-blown deposits to Mesozoic carbonates. This set the pace for the workshop (45 oral and 15 poster presentations) as the participants wanted to discuss these geological features on borehole scale, with image logs and core in addition to other wellbore data.

Chandramani Shrivastava and Mohammed Al Fahmi welcoming participants and outlined the overall agenda, encouraging interactive engagement over the three days of technical discussions. Sessions included classical applications in sedimentary and structural geology, reservoir architecture, quantifying reservoir attributes, well operations and technology, data analytics in borehole geology, sustainability in the energy mix bridging the gap between 1D borehole geology models and 3D digital earth models delving into cutting edge innovations, practical applications, and expanding the role of borehole geology across diverse industries including energy, mining and environmental sectors.

Keynote speakers shared their experience and talked about overcoming the existing challenges of the industry using digital innovations with domain technical excellence. Lawrence Bourke talked about 40 years of interpretation experience with lessons learned and forthcoming expectations, Pascal Richard continued with the field trip experience to discuss borehole images for fracture interpretation and modelling. Josselin Kherroubi outlined the journey of borehole image interpretation with advances and challenges on the way.

Presenters talked through the length and breadth of borehole geology, from complex manual geological interpretations to machine-learning based answers and new downhole tools. Operating companies talked about operational challenges and interpretation issues while service companies focused on technological advancements to address those challenges. Interpretation consultants provided insights with decades of experience through borehole geology problems while academia and environment sector presenters spoke about availability of data or lack of it for longterm projects. Discussions on long existing classical hydrocarbon exploration/development to emerging geothermal and radioactive waste disposal to carbon sequestration ensured there was not a single moment where a single participant felt out of place.

Three days of this super-engaging workshop ended with lots of promises around how the wide-scale adoption of borehole geology answers can help in the larger energy mix for humanity.

Convenors George Ghon (CapGemini) and Lukas Mosser (Aker BP) discuss AI developments stemming from the workshop ‘Foundation Models in the Geosciences’ at the EAGE Annual in Toulouse.

As AI applications progress from the breakthroughs in one domain such as text generation or image classification toward solutions that provide an integrated system of information processing across different modalities, new model paradigms are emerging that learn from different data types and incorporate multiple and varied representations of reality.

These advancements and the corresponding development of new model architectures shift the dialogue toward a better understanding of the complexities of the physical world and its phenomena. This has led to the coining of terms like world models or foundation models that represent or can analyse a whole domain, or the entire world.

A common understanding of foundation models is that they are trained on very large datasets that capture a representation of reality and its underlying relations. From a statistical perspective, this means learning a general distribution from data. This enables the prediction of new properties or insights beyond merely acting on a subset of representative examples. A foundation model should be able to generalise across a domain rather than just learning a specific set of examples that have been used for training purposes.

For text-based models, or LLMs, this goal has been achieved by training models on virtually all public documents that are available on the internet to generalise across language. Attempting to generalise across different modalities, architectures have been developed that can train on text, images, sound, and video, bridging those distinct layers into a more universal representation of reality. Modern foundation models can effectively combine vision and language tasks, learn from both images and text, and predict in both those domains. It is a powerful capability to shift from a singular representative mode to a model or system that can process multiple types of data that describe related phenomena in different ways. In subsurface applications, many datasets such as seismic volumes and associated property cubes can be represented and processed as images. They can be complemented by textual sources and integrated with specific information such as well logs and geospatial context.

Model architectures and training methods developed by AI labs for general purpose applications can be adapted to subsurface

workflows and open a new paradigm for integrated subsurface understanding and interpretation. Challenges do remain due to data sparsity of direct measurements and the high ambiguity that these signals represent in terms of subsurface properties and characteristics. Increasing availability of powerful compute, focus on data quality and higher efficiency in training algorithms, however, continue to push the field forward and allow for the development of more powerful models or integrated systems that can interpret the subsurface in new and better ways.

During the workshop ‘Foundation Models in the Geosciences’, hosted by the EAGE Technical Community on AI at the EAGE Annual in Toulouse, we gathered a range of speakers working in the field of developing subsurface foundation models in both academia and industry. One contributor Anders Waldeland is leading a consortium at Norsk Regnsentral (NR) to develop a seismic foundation model based on DISKOS, the Norwegian national repository for data on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS). The team at NR, with contributions from Equinor and AkerBP, train the NCS model on all available full stack volumes in both time and depth, which represent around 48TB of data. The model utilises a vision transformer architecture employing a masked autoencoder for a self-supervised training regime. Current experiments are focusing on a comparison between 2D and 2.5D approaches, the latter including additional patch directions at 450 and 1350 angles, and benchmarking both methods on tasks like salt segmentation, sedimentary package identification, flat spot and injectite mapping. Comparing performance on non-NCS datasets indicate the model´s ability to generalise and point toward further research directions that could include angle stack data to predict AVO effects and well logs to infer lithologies from seismic.

A push toward multi-modality in subsurface interpretation was presented by Xinming Wu, who introduced the ‘Geo-Everything Model’, a foundation model applicable to various interpretation tasks such as 3D property modelling, structural interpretation and geobody identification. The model combines unsupervised pre-training on seismic as well as synthetic property volumes with a supervised post-training step for structure related tasks. This incorporates a mixture of labels and prompts for diverse interpre-

tation tasks in a conditional generative process that is enabled in a generative adversarial (GAN) framework. The conditioning of sparse interpretation labels on seismic imaging data allows for a realistic or guided estimation of subsurface properties in a zero-shot regime by providing a suitable prompt to the model as well log or geobody mask to predict the desired property in 3D.

Haibin Di from Slb presented a seismic foundation model built with a vision transformer style encoder that is pre-trained in a self-supervised manner on a large corpus of real and synthetic seismic data. The model is trained with multiple pretext tasks, including denoising, energy and phase prediction, and lateral/ vertical interpolation. This encourages the network to learn a rich latent representation of seismic texture and structure without relying on human labels.

On top of this shared representation, three usage modes are demonstrated. In a direct inference mode, operations in latent space and lightweight task heads enable 2D-3D interpolation, 4D anomaly detection and rapid geo-feature screening across surveys without additional training. In an instantaneous learning mode, simple models such as random forests and multilayer perceptrons are fitted in seconds on top of the latent features to propagate well markers and logs for facies classification and property inversion, achieving higher lateral consistency and reduced training cost compared with conventional CNN-based approaches. Finally, a light fine-tuning mode attaches a small segmentation network to the frozen

backbone to perform one- or few-shot seismic image segmentation, showing improved generalisation and faster convergence relative to training from scratch. Together, these results illustrate how a pretrained seismic foundation model can act as a versatile backbone for conditioning, interpretation and inversion workflows while substantially reducing manual labelling and compute requirements.

We see these approaches breaking the ground for new ways of working where an emerging generation of models can perform a variety of routine geoscience tasks and legacy workflows are increasingly replaced or augmented by more integrated model driven systems that can increasingly autonomously interpret seismic data, identify geobodies and propagate well log properties across volumes.

Seismic foundation models are emerging that begin to learn inherent wave-based property distributions such as phase and energy, gaining a more fundamental understanding of the data. Integration of pre-stack data into models could lead to breakthroughs in AVO analysis and an extension to 4D seismic as time series, potentially introducing predictive reservoir analysis. As AI in the subsurface industry is still waiting for a genuine ChatGPT moment, these emerging models and novel approaches are increasingly pushing toward it.

Catch up with the EAGE Technical Community on AI

Prof Zvi Koren and Dr Alan Vigner from AspenTech were guests at London Chapter’s recent meeting to deliver an insightful lecture on advanced subsurface velocity modelling techniques used in geophysical and geological interpretation.

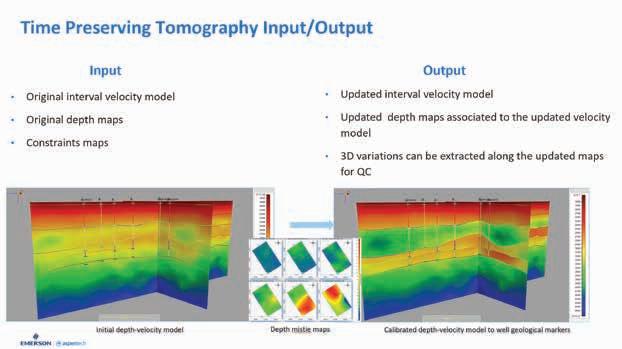

The core of their presentation centred on two complementary algorithms: time preserving tomography (TPT) and reverse time migration (RTM) demigration/remigration. TPT is regarded as an efficient, automated workflow that resolves time-depth conversion uncertainties and minimises a well’s miss-ties by adjusting velocity models while maintaining kinematic consistency with seismic data. The RTM technique, a post-stack process, allows for the quick generation of new seismic images based on TPT-derived velocity models, avoiding the need for a full pre-stack depth migration (PSDM).

Time-Preserving Tomography (TPT) efficiently updates the subsurface velocity model while preserving the consistency of seismic travel times.

The presentation emphasised that these tools create a crucial bridge between processing and imaging teams and interpreters, allowing for rapid iterative updates, scenario testing and uncertainty analysis. This ensures the geological and geophysical data remain consistently synchronised throughout the project lifecycle. The lecture has been recorded and is available on the EAGE YouTube channel.

We want to welcome the newly formed EAGE Student Chapter from the Universidade Federal do Ceará in Brazil. Students from various academic levels - undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral - share a strong interest in expanding geoscientific knowledge, fostering innovation, and strengthening academic collaboration, while also contributing to the global EAGE community.

Chapter members are engaged in studies and research that range from geophysical methods applied to mineral and petroleum exploration to emerging applications related to the energy transition and geological risk mitigation. They are seeking to integrate computational modelling, data processing and geological interpretation to address sustainable development challenges as well as disseminate geoscience knowledge through activities in schools and student events.

Supported by the Department of Geology, the Laboratory of Geophysics for Prospecting and Remote Sensing (LGPSR), the Innovation and Research Group in Energy and Mineral Resources (GIPEM), and collaborating faculty members, such as their chapter advisor, Professor Karen Leopoldino, they have access to well equipped laboratories, computational tools and academic mentorship that enable

solid technical training and meaningful practical experience.

This includes specialised facilities, professional software and a learning environment that encourages research, technical development and student leadership. This institutional support strengthens their initiatives and allows students to enhance their skills in geophysics research.

For 2026, the Chapter is planning a series of activities focused on technical development and student engagement, including guest lectures, academic meetings, study groups, and outreach actions. The activities aim to connect students with practical geophysical applications, expand professional networks and stimulate interest in scientific research. One of the goals will be to offer continuous training opportunities, facilitate access to EAGE resources, participate in events, academic challenges, and development programmes.

The latest issue of Preview (Volume 2025, Issue 239) published by the Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists (ASEG) is now available on EarthDoc, offering readers a window into the world of geophysics, exploration and industry innovation.

Editor Lisa Worrall reflects on the past year in geoscience and the trends shaping the industry and also features the surprising results of the annual Stock Market Game offering a playful yet insightful take on economic and market forces.

The issue also delves into the booming mineral exploration sector in Australia. Students and early-career geoscientists will find the coverage on postgraduate developments particularly compelling, with discussion of enrolment trends, scholarships

and research initiatives reflecting both the pressures and possibilities in education today.

Technical and commentary sections explore environmental geophysics applications, mineral geophysics insights and cutting-edge data trends. The fourth instalment of the Geomagnetophilia series provides an in-depth look at the magnetic signatures of the newer volcanics in southwest Victoria.

Rounding out the issue, a book review guides readers through interpreting soil test results, offering practical insights for both fieldwork and laboratory analysis.

Explore the full issue and dive into these articles at EarthDoc.

The EAGE Student Fund supports student activities that help students bridge the gap between university and professional environments. This is only possible with the support from the EAGE community. If you want to support the next generation of geoscientists and engineers, go to donate.eagestudentfund.org or simply scan the QR code. Many thanks for your donation in advance!

Sanjay Rana can look back on a remarkable career having established the first commercial company in India to introduce engineering geophysics solutions to tackle the country’s infrastructure needs. A prolific writer, he is also a sought after keynote speaker promoting his discipline and its value.

I grew up in a very typical Indian middle-class household with an itinerant, upright civil servant father. We were never left wanting for anything, yet we didn’t have a problem of plenty either. Because of my father’s frequent transfers, I moved cities often, which turned out to be a gift in disguise. It exposed me early to different cultures, languages, people, and ways of thinking. Adapting became second nature. School years were a happy mix of academics and cricket − lots of cricket!

My university years at IIT Roorkee were intense, enriching, and honestly, really fun. Academically, I was a very focused student and graduated as a gold medallist and class topper but I certainly didn’t live only in the library. I was deeply involved in cricket, badminton, shooting, debating, and theatre. I often joke that I did everything possible to distract myself from studies, yet never really got distracted. A friend actually nudged me toward geoscience, and it clicked instantly I loved the outdoors and knew I wasn’t made for a conventional 9-to-5 desk life.

My first job was with UP Electronics, where I worked as a geophysicist handling commercial well logging, while also being asked to train others. That part came as a surprise. I found myself mentoring professionals twice my age. This was both daunting and deeply rewarding. It taught me early on that age matters far less than clarity and conviction.

My five years’ experience in the nuclear sector was intense, highly disciplined and deeply enriching. I was involved in uranium exploration projects, work that even today remains largely confidential − and I’m still literally under oath!

The decision to start my own company came from a mix of curiosity and frustration. I was closely following global trends in engineering, technology and academia, and was surprised by how little near surface and engineering geophysics were being applied in India, despite huge infrastructure needs. I took the leap largely on my own, but with strong encouragement from friends abroad working in geosciences. They assured me this model was not only viable but necessary, thereby bringing about one of India’s first dedicated private engineering geophysics companies.

The company evolved organically with the country’s needs. We began with groundwater exploration, but as India’s infrastructure expanded, it became clear that subsurface utility mapping and GPR applications were far more important. Today we are an authority on dam geophysics. Early international collaborations with friends abroad helped us to bring advanced equipment into India and execute our first projects. We started very small, with a lean team and lots of hands-on work. Over time, this grew into international operations, including offices and projects in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Singapore.

Some of the projects I am most proud of are those where geophysics directly contributed to saving lives. The Silkyara tunnel collapse stands out deeply. In such moments, technology stops being academic or commercial. It becomes human.

My vision is that engineering geophysics becomes a standard and integral part of every major infrastructure project, not an optional investigation carried out only after problems arise. A clear understanding of the subsurface should inform design decisions from the very beginning. With advances in sensors, AI and data integration, engineering geophysics will move beyond one-time surveys to continuous subsurface intelligence, supporting construction, operation and long-term health monitoring of assets like dams, tunnels, and bridges.

At home, I try to keep life simple and balanced. Mornings usually begin with yoga and some exercise − it helps set the tone for the day. I enjoy light to moderate reading, mostly to stay curious rather than being overwhelmed. In the evenings, I prefer meditation to slow things down and clear my head after a busy day. I’ve never really been a television person; silence and reflection work much better for me. These routines help me stay grounded and reasonably sane.

BY ANDREW M c BARNET

The word uninvestable, recently coined by ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods in connection with the current dilapidated state of Venezuela’s oil industry, is not to be found in traditional English language dictionaries. However, its meaning is pretty clear. In a lighter moment Woods might like to consider the following lyric adapted from Unforgettable, the trademark song of the legendary Nat King Cole:

Uninvestable

That’s what you are

Uninvestable

Though near or far

Obviously, President Donald Trump would not be amused. He met with US oil company executives shortly after the capture and abduction of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife to interest them in his plan to take over the running of the Venezuelan oil industry indefinitely and control its exports. A vital part of this extraordinary intervention in another country’s government was Trump’s apparent assumption that American oil companies would willingly step in to revitalise the disastrous condition of Venezuela’s hydrocarbons extraction industry, once the envy of the world.

In a statement after the meeting with Trump, the ExxonMobil CEO issued a carefully crafted statement that ruled out immediate investment – uninvestable – but left the door ajar if certain conditions were met. That did not go down well with the president who said he was ‘inclined’ to leave ExxonMobil out of future US industry participation in Venezuela.

What Woods sidestepped was that Venezuela’s fortunes for the past century have depended on production of its oil resources, often perilously beholden to the US. Safe to say it has not gone well. The country is a disaster featuring a corrupt tyrannical government, crumbling infrastructure, widespread poverty, large-scale emigration, and of course a barely functioning oil industry, virtually the only source of income.

The country can certainly be categorised as an early victim of the ‘oil curse’. As such the oil companies who flocked to Venezuela in the 1920s and proceeded to build a stunningly successful production machine cannot be absolved from some complicity in today’s tragic mess.

‘By 1929 Venezuela was the world’s leading exporter’

Trump must have thought the deal was handing back to the US industry access to the country’s enormous potential oil wealth. Although some believe the numbers may be inflated, Venezuela’s 300 billion barrel reserves, located mainly in the Orinoco oil belt, are said to be the largest in the world. How recoverable and at what cost this almost exclusively heavy oil may be is another question. As a further enticement, the Trump Administration was pushing the contested claim that control of Venezuela’s production would enable recovery of oil that was ‘stolen’ from licensed US companies as part of the country’s nationalisation strategy formalised in the 1970s. It is true that companies (notably ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips) are owed billions from sequestration of their assets and continue to pursue their claims in international courts.

The oil experience in Venezuela began in 1914. Caribbean Petroleum, a Shell subsidiary, drilled the successful Zumaque 1 well, establishing the Mene Grande field in the Maracaibo Basin as the country’s first oilfield to go into operation, its development slowed by the onset of the First World War. It was the infamous blowout in 1922 of another Shell well, Barroso 2 in Cabimas, Zulia state, that effectively acted as an advertisement for Venezuela’s petroleum potential, although a local ecological disaster. A column of oil jetted out of the well at 100,000 b/d for a week. The incident proved a potent signal for the start of the oil boom. By 1929 Venezuela was the world’s leading exporter and a decade later was only behind the US and Russia in its production. Three companies Gulf, Shell and Exxon controlled some 98% of the Venezuelan oil market.

This was an unexpected outcome for a country that only fully achieved its independence from Spain in 1830, thanks in part to the interventions of the legendary Simón Bolívar. For the rest of the century it languished as an impoverished agricultural economy

mainly exporting coffee and cocoa, and ruled by a succession of regional military caudillos.

The key figure in Venezuela’s early oil history was Juan Vicente Gómez, who in 1908 ousted Cipriano Castro as president in a coup d’etat and retained power until his death in 1935 either as president or the power behind the scenes. His governing style was dictatorial, ruthlessly suppressing opposition, but he understood the significance of oil as transformative for both the country and his personal wealth.

‘Perilous overdependence on oil unravelled’

The tone was set by the 1922 Hydrocarbons Law based on concessions. This required foreign companies to pay state royalties and taxes but allowed them a free hand to produce and export crude oil, much of it processed along the Gulf of Mexico coast, thereby setting up an early dependence on US facilities. Gomez is credited for using the oil revenues to build some basic infrastructure and pay off the debts accrued by his predecessor, but his policies did not do much to improve the lot of the majority, for example, having little time for education and trade unions.

Gomez’s departure brought to the surface an underlying popular resentment at the perceived lack of benefit from – and to a degree, participation in – the ongoing oil bonanza (by 1940 producing 27 million tonnes per year). Possibly emboldened by the 1938 nationalisation of the petroleum industry in Mexico and the creation of Pemex and a government at home edging towards a more democratic system, the ruling regime enacted more aggressive hydrocarbon regulations. Royalties rose from no more than 11 to 16 and twothirds per cent, and concessions were limited to a further period of 40 years. A profit-sharing deal – the so called fifty-fifty rule – was enshrined in legislation by President Rómulo Betancourt, ‘the father of Venezuelan democracy,’ in his first brief period as president (1945-48) before being ousted in a military coup. The arrangement remained in place until 1976, despite initial oil industry outrage.

In fact, the post-Second World War period was astonishingly profitable for Exxon at least, through its Creole Petroleum unit. According to one account, the company’s output in Venezuela soared from about 400,000 b/d in 1945, to 660,000 b/d in 1950, to almost 1.5 million b/d in 1974 with Creole providing for as much as 40% of Exxon’s global profit.

The first omen that the golden era could not last was when Venezuela proved an active founder of OPEC in 1960 at first with Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. The idea was for producing nations to limit the control on production and prices exerted by the oligopoly of major oil companies.

However, the fateful year was 1976. Following the 1973 oil crisis in which oil prices rocketed in producers’ favour, Venezuela under President Carlos Andrés Pérez, transferred control of the oil industry from foreign companies to the state, in the process creating Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). It was an orderly transition for which oil companies felt poorly compensated. A telling reflection on the motive for the nationalisation move can be found in a speech by Felix

P. Rossi-Guerrero, at some point Venezuelan minister counsellor for petroleum affairs, published in Vanderbilt Law Review (1976), in which he explains the ‘disbelief then anger’ at the betrayal by the US. Venezuela had cooperated in boosting its production to help the US in times of crisis, e.g., the Second World War, Korea, Suez, etc. But when President Dwight Eisenhower introduced a quota system on oil imports to protect domestic producers in 1959, he gave preferential treatment to Canada and Mexico.

Post nationalisation of its oil production, Venezuela’s oil sector sustained production of 3 million b/d, contributing around 25% of gross domestic product, more than half the country’s revenue, and between 80 and 90% of total exports, according to data from the World Bank and the US Energy Information Administration.

This perilous over-dependence on oil unravelled when the revolutionary Hugo Chávez swept to power in 1998 on the promise of ending corruption, increased spending on social programmes, and redistributing the country’s oil wealth. His radical agenda soon invoked national protest including a general strike involving 38,000 PDVSA employees, half of whom were fired at the end of the dispute, significantly harming the efficiency of future oil production. Overseas, the close relationship with Cuba and support for regimes in countries like Iran, Iraq and Libya won the regime no friends. Oil companies, including Exxon, left in 2007 under the duress of new oppressive regulations, leaving Chevron as the only foreign company responsible for around 10% of the country’s output.

As we all know, Chávez’s ruthless successor, President Nicolás Maduro, now in US custoday, did little to salvage Venezuela’s plight and leaves a country in limbo chastened by its reliance on oil. Among other issues, the country has been subject to periodic sanctions, and a UN report estimated in March 2019 that 94% of Venezuelans live in poverty and that one quarter of the population needs some form of humanitarian assistance.

Meantime, according to OPEC data, crude exports plunged from nearly two million barrels per day in 2015 to less than 500,000 in 2021, although a partial recovery has been observed since 2023: 655,000 barrels per day in 2024 and 921,000 barrels per day in November 2025.

A bleak analysis by Rystad Energy suggests recovery of the Venezuelan oil and gas sector would require investment of some $183 billion between now and 2040 to get the country back to crude production of 3 million barrels per day by 2040,

No wonder Exxon Mobil’s Woods is wary, especially when prospects in neigbouring Guyana are proving so rewarding, and assuming he doesn’t take too seriously Venezuela’s longstanding claims to some of this territory. He will probably want to stick with: Uninvestable

In every way

And forevermore

That’s how you’ll stay.

Views expressed in Crosstalk are solely those of the author, who can be contacted at andrew@andrewmcbarnet.com.

More than 20 significant seismic surveys and reprocessing projects will be carried out after Norway awarded 57 production licences to 19 companies in the APA 2025 licensing round.

In the North Sea DNO, Petoro, Aker BP and Source Energy will reprocess 3D seismic data on Licence 1086; DNO, Aker BP and Petoro will acquire new 3D seismic data on licence 1278; Equinor and DNO will reprocess 3D seismic data on licence 1280; Equinor and Aker BP will reprocess ocean bottom seismic data on licence 1282; Aker BP and DNO will reprocess 3D seismic data on licence 1286; Equinor, Petoro, Pandion Energy and Concedo will acquire modern 3D seismic data and EM data on licence 1288; Wellesley Petroleum and DNO will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1290; Concedo, Equinor and OMV will acquire modern 3D seismic data on licence 1292; Equinor and OKEA will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1293; Petrolia and Equinor will acquire modern 3D seismic data on licence 1294; Wellesley and Equinor will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1295.

In the Norwegian Sea, Aker BP, Petoro and Equinor will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1296; Equinor, Petoro and Inpex will reprocess 3D seismic data on licence 1297; Vår Energi, Petoro, Equinor and TotalEnergies will reprocess 3D seismic data on licence 1298; Equinor and Harbour Energy will

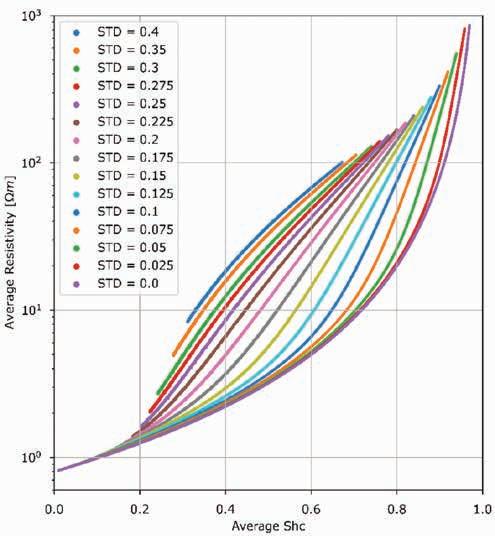

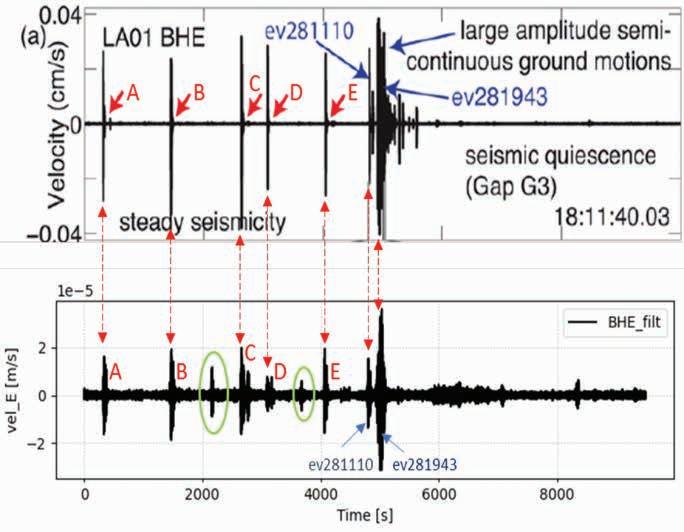

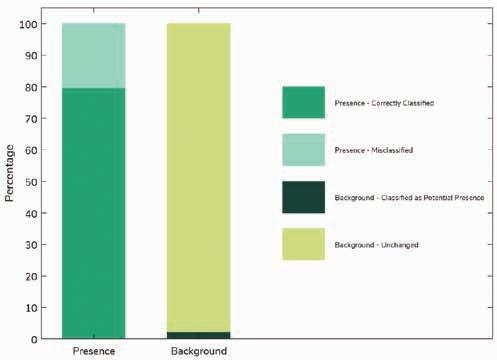

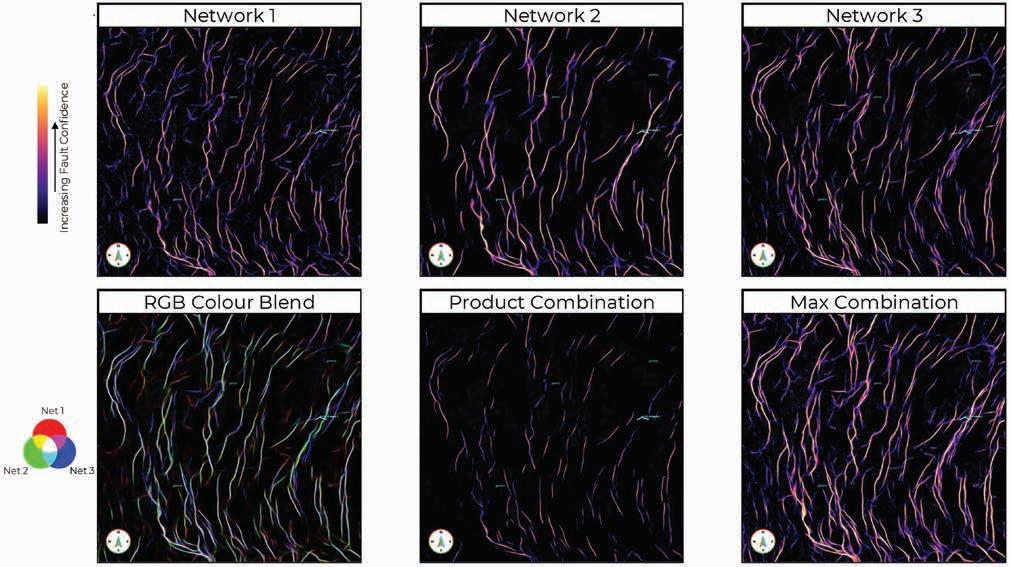

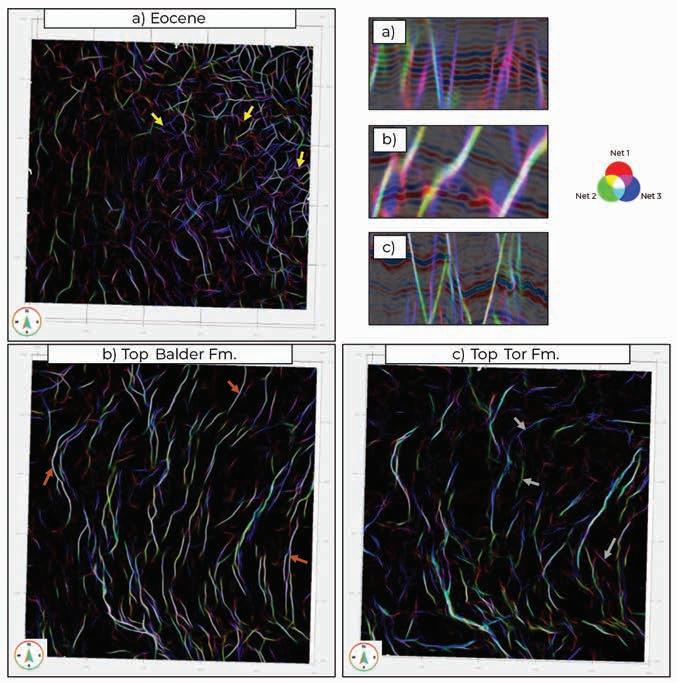

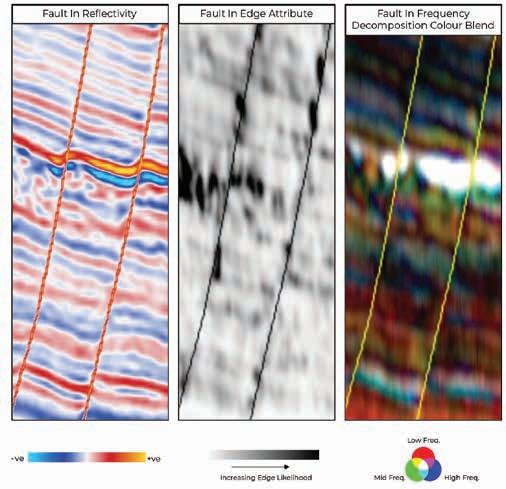

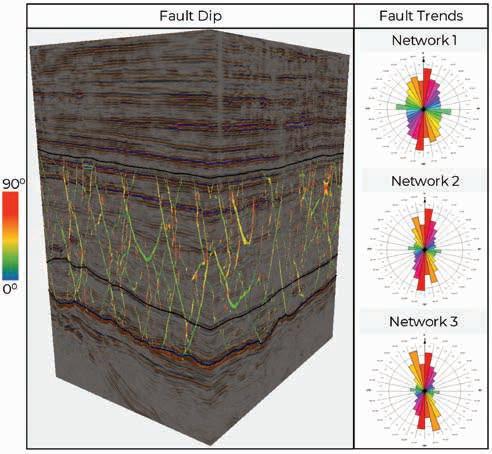

acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1299; OMW, Petoro and Equinor will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1302; OKEA, Petoro, and Equinor will acquire 3D seismic data on licence 1305; Aker BP will acquire 2D OBN data on licence 1308; and Equinor and Japex will carry out a feasibility study for seismic reprocessing on licence 1310.