JULY/AUGUST 2025

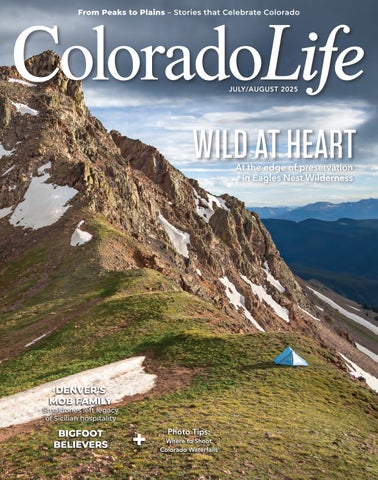

WILD AT HEART

At the edge of preservation in Eagles Nest Wilderness

DENVER’S MOB FAMILY

Smaldones left legacy of Sicilian hospitality

BIGFOOT BELIEVERS +

ISSUE NO. 79 | JULY/AUGUST 2025

FEATURES

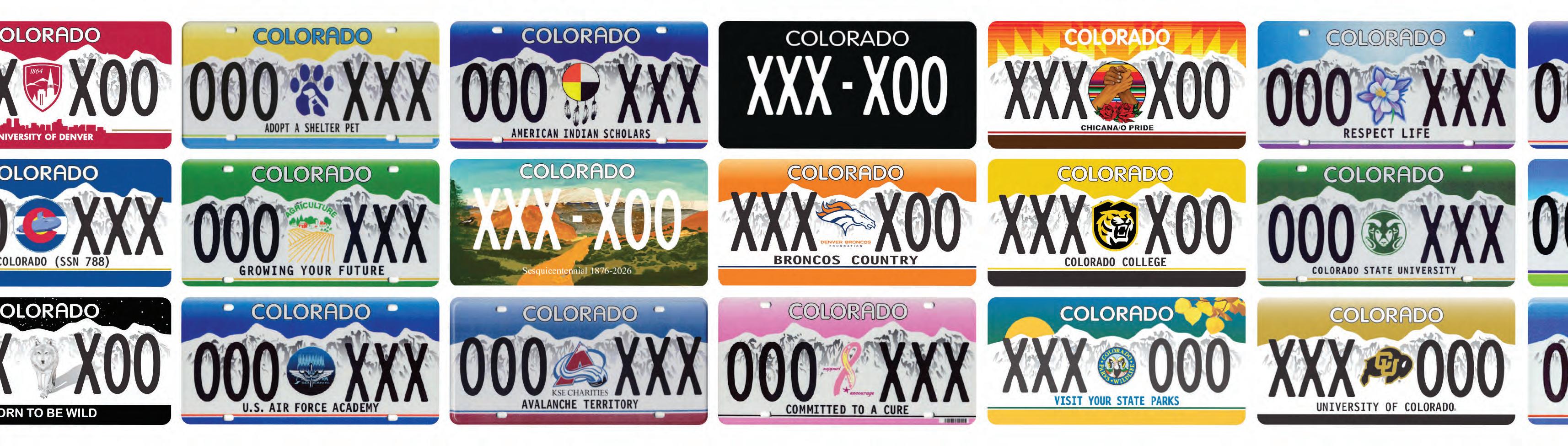

16 Vanity Plates

Colorado’s 200-plus license plate designs reflect passions, humor and identity – all crafted by inmates in the Cañon City prison plant. by

Peter Moore

22 Smaldone: Denver’s Family Mob

Gaetano’s once served as headquarters for the Smaldone family mob. Though the empire no longer runs the city, the North Denver restaurant still stands. by Matt

Masich

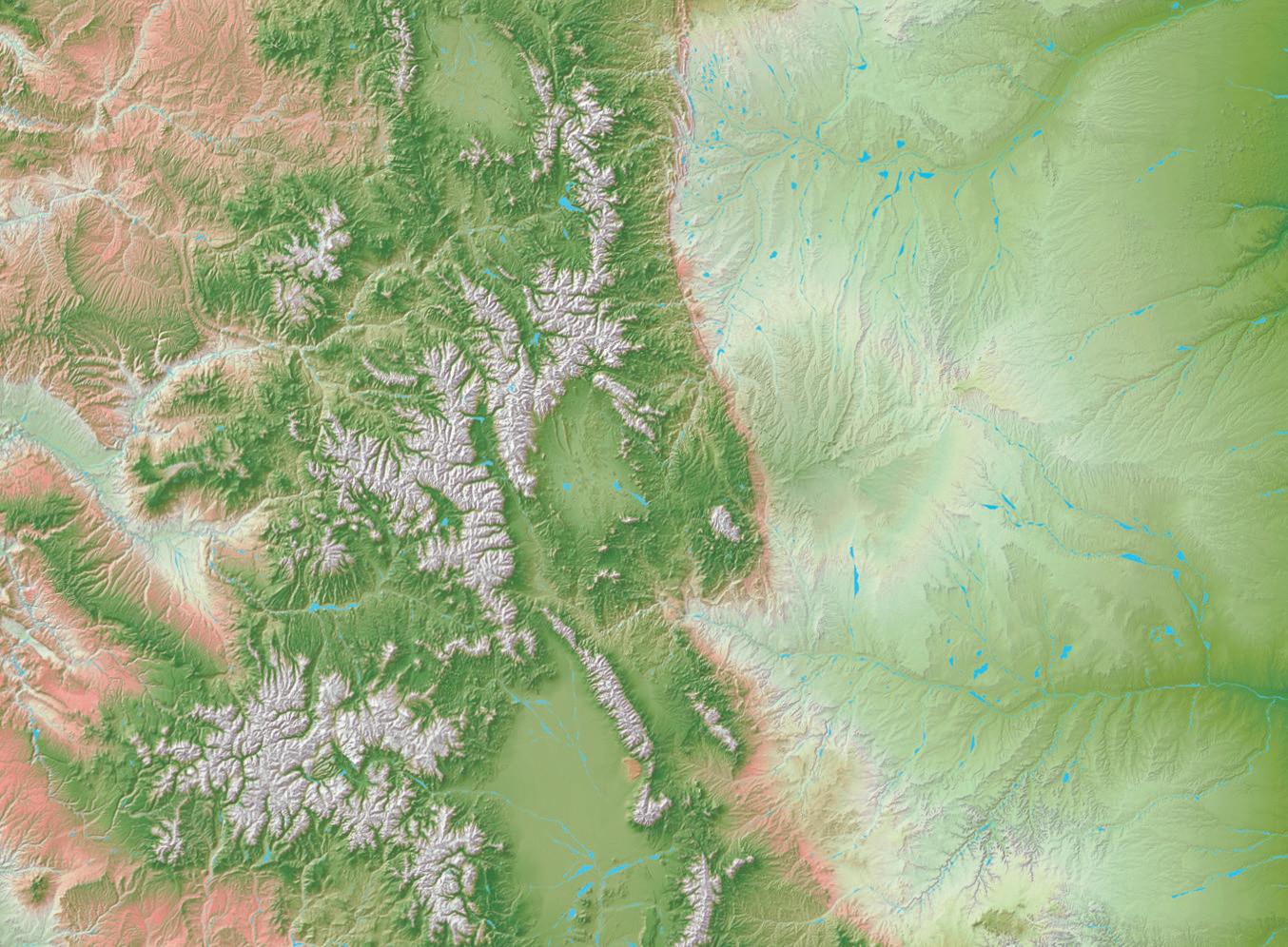

28 Eagles Nest Wilderness

Among abandoned cabins and serrated peaks in Eagle’s Nest Wilderness, fleeting moments in the wild remind us why it’s worth preserving. story and photographs by Dean Allen

40 Freedom in Full Color

Hot air balloons fill Colorado Springs skies each Labor Day weekend, as 200,000 spectators join 75 pilots and their crews for this beloved high-flying tradition. by Tom Hess

52 Bailey’s Bigfoot Believers

Under a moonless Pike National Forest sky, Bigfoot believers join Jim Myers’ guided night hike to look for signs of the legendary creature. by Eric Peterson

9 Editor’s Letter

Chris Amundson shares stories from life in Colorado.

10 Sluice Box

The first highline across Royal Gorge Bridge; artist Amy Winter paints Colorado’s landscapes inspired by treks deep in the wild; students trade desks for trails at CSU Mountain Campus.

VisitPueblo.org/meetings

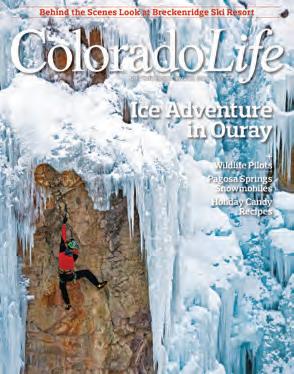

ON THE COVER

Snow Peak in Eagle’s Nest Wilderness near Vail rises to 13,024 feet. Its dramatic prominence and challenging climb are vivid reminders of why the wild is worth saving. Story begins on page 28.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DEAN ALLEN

IN EVERY ISSUE

18 Trivia

Colorado is iconic – but do you know these state symbols? Answers on page 51.

20 Top Take

Every day for two months, photographer Vic Schendel studied a neighborhood fox near Fort Collins.

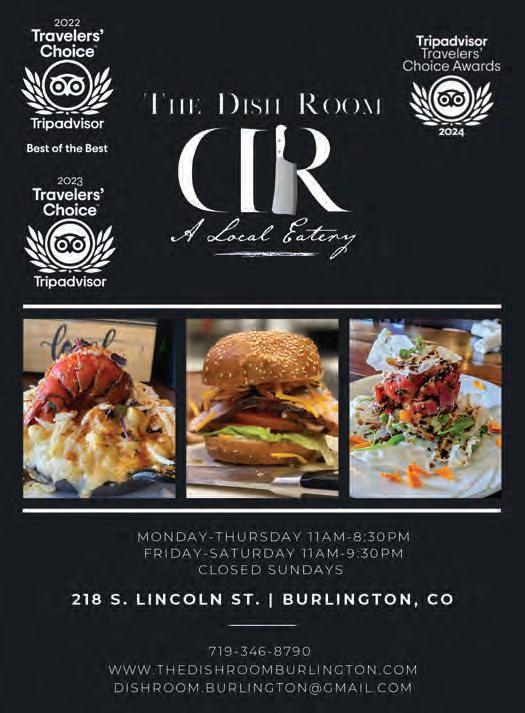

34 Kitchens

Easy, refreshing pick-me-ups – perfect for poolside afternoons.

38 Poetry

Poets wander winding trails, gathering nature’s whispers with every step.

46 Go.See.Do.

Pueblo’s chile festival draws 150,000 for a blazing-hot, three-day fiesta; witness the mating spectacle of thousands of Colorado brown tarantulas near La Junta.

50 Camping

Dan Leeth visits Mud Springs Campground for a cool Western Slope escape.

54 Peak Pixels

The late-summer sequel to Josh Hardin’s quest for waterfalls –this time on the Front Range and in the central mountains.

JULY/AUGUST 2025

Volume 14, Number 4

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Photo Coordinator

Erik Maki

Staff Writer

Ariella Nardizzi

Design

Mark Del Rosario

Editorial Assistant

Savannah Dagupion

Advertising Sales

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Sheila Camay

Intern

Lucy Walz

Colorado Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130

Fort Collins, CO 80527 970-480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com or visiting ColoradoLifeMagazine.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

NOn Familiar Trails

EXT AUGUST, COLORADO will celebrate 150 years of statehood – its sesquicentennial. It’s a milestone that invites us to reflect on what has endured, evolved and continued to shape life here in the Centennial State. Tradition, in its many forms, threads through the stories in this issue.

For our family, those threads ran through the years we spent raising our children in Estes Park. Summers meant day camp at YMCA of the Rockies, where the kids made friends from across the country and learned to love the mountains in their own way. We hiked to waterfalls like Calypso Cascades in the Wild Basin region of Rocky Mountain National Park, took visiting relatives up the Estes Park Aerial Tramway, and capped the day with caramel apples from Laura’s. Those moments – simple, repeated, shared – became part of our children’s formative years and part of our own story of home.

At 9,000 feet in the Mummy Range, the Colorado State University Mountain Campus has connected young people with the land for over half a century. “High Country Classroom” details how Eco Experience has guided fifth graders through alpine streams and forested valleys, teaching orienteering, wildlife observation and stream ecology.

Students come away from the three-day program not only with knowledge but with a sense of belonging. Generations have returned in various ways – like Phillip Chavez, who was a student, instructor and now a chaperone for his own children. Others, like Mountain Campus Assistant Director Jessica Smolenske, found inspiration there for their career paths.

High above Colorado Springs, another tradition takes flight. For nearly 50 years, the Labor Day Lift Off has painted the sky with balloons, drawing 200,000 spectators along with pilots and crews into a shared celebration of craft and camaraderie. As told in “Freedom in Full Color,” pilots like Skip Howes and Desiree Tucker rise before dawn to tend to burners and ropes, keeping alive the spirit of those first friendly balloon races in 1976.

In North Denver, Clyde and Checkers Smaldone’s legacy shows a different kind of tradition built on complexity and resilience. From bootlegging to gambling and opening Gaetano’s in 1947, the mob family left an indelible mark on the city. Yet their true inheritance may be the way they raised their children, steering them away from crime and toward law-abiding lives that continues in the booths of Gaetano’s Italian restaurant – and in our feature story “Smaldone Denver’s Family Mob.”

Even still, in Colorado’s wilder places, tradition persists in quieter ways. Dean Allen’s “A Wilderness Worth Keeping” tells of mountain goats instinctively navigating the alpine tundra and humans following paths forged over centuries. It’s a Colorado that existed long before our settlements – and will persist long after.

Whether it’s a family hike in the Rockies, an annual visit to a favorite festival or the rituals of local community you hold dear, we are walking familiar paths.

Share them with us, and let’s celebrate the traditions – big and small – that define our beloved state.

Chris Amundson Publisher & Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

NUGGETS AND OBSERVATIONS ABOUT LIFE IN COLORADO

Walking the Edge – Again

The stars of our March/April cover story take their daring act to the Royal Gorge Bridge

story by ARIELLA NARDIZZI photograph by ERIK MAKIĆ

In our March/April 2025 cover story “Walking the Edge,” we followed Colorado highliners as they pushed the limits above the state’s wildest landscapes – from the Flatirons to the Great Sand Dunes. This summer, one of those athletes brought his craft to a Colorado icon: the Royal Gorge Bridge near Cañon City.

On July 19-20, 2025, Logan Henning and fellow athletes Brandon Proffitt, Henry Adams and Sean Englund balanced on a strip of webbing less than an inch wide, stretched across 918 feet between

the bridge’s steel towers. The line hovered roughly 30 feet above the bridge deck, and about 1,010 feet above the Arkansas River below. Visitors streamed past as the crew spun, dropped and walked steadily across the airy gap.

Three times during the weekend, the team gave live demonstrations, explaining the rigging, safety systems and skill behind highlining. Crew members Bali Fitzpatrick, Nathanael Enos and Isaac Leighninger anchored the line to the bridge’s cables and set up a lower slackline nearby so visitors could try a ground-level version.

Henning – a Colorado Springs resident, founder of Community Highlines, and de-

scribed in event promotions as a “4-time world-record solo-rig highliner” – has performed around the country, but says there’s nothing quite like highlining over the Royal Gorge. “Usually we’re in remote places with no one around,” he said. “Here, we get to share the energy with a crowd.”

Next summer, Henning and his team plan to return for an even more ambitious feat – crossing the gorge itself during the July 4, 2026, weekend. Timed to coincide with Colorado’s 150th and America’s 250th birthdays, the event will combine one of Colorado’s most dramatic natural landmarks with one of the sport’s most daring displays of balance and agility.

Where Adventure Becomes Art

Amy Winter hikes, paddles and rides into Colorado’s wild places – then paints their spirit in bold strokes

by CORINNE BROWN

High-country dust hangs in the air, the Yampa River sparkles under a wide Colorado sky and artist Amy Winter rides alongside a herd of mustangs. She’s here for more than the view – she’s gathering the raw experiences that power her art. From rushing rivers to wary wildlife, Winter’s canvases carry the texture, light and pulse of the West because she has stood in the middle of it.

At home in Denver, Winter doesn’t just live in the West – she immerses herself in it. Hiking steep trails, kayaking fast water and riding through open country, she feeds her art with adventure. Her paintings, alive with Colorado landscapes and the animals that inhabit them, are a cycle of inspiration: each trek sparks new work, and each finished piece sends her back into the wild again.

That bond with the outdoors began early. As a child, Winter traveled the West with her mother, who homeschooled her on the road. For a time, they lived off the grid, giving her a front-row seat to the rhythms of nature. By high school, she had already claimed the wilderness as her own. A degree in art from Western State College in Gunnison gave her the tools to translate those experiences into paint. Later, working as a fire lookout sharpened her eye for detail and deepened her respect for the land.

Whether paddling the Yampa, riding with mustangs or trekking remote trails, Amy Winter immerses herself in Colorado’s wild places, then brings them to life in bold, textured paintings.

“My goal,” Winter said, “is to encourage others to share the world of wild animals. I try to capture their expressive emotions, be it a mama fox protecting her kits or a mustang singled out from a week-long horse drive, eyeing a human from afar. By portraying them this way, I hope to make the viewer more aware of his or her own humanity.”

She recalls the Sombrero Ranch horse drive near Craig, following wranglers through sagebrush and across the Yampa, clouded by the same dust the artist breathed as she followed along.

Even in controlled settings like the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Keenesburg, her brush finds vitality. A bear rendered in

bold, fluid strokes is a colorful statement inspired by reality, but never mirroring it. Winter prefers to work large, often with flat palette knives called spatchers, tools that let her move freely across the canvas. Her studio, tucked into her home, is where the journeys take shape. Every reference photo is her own, sometimes requiring days of camping for a single perfect shot. She says she loves rivers – the way they tumble and cascade – and sometimes becomes enamored with one in particular, whether it’s the Roaring Fork, the Arkansas or the Lake Fork of the Gunnison. For Amy Winter, exploration isn’t just part of the job – it’s the heart of it.

High Country Classroom

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

The first thing you notice is the quiet. It hums with life – wind whispering through lodgepole pines, the rush of the Cache la Poudre River over rocks, and the footsteps of fifth graders discovering what it means to connect with a place like this.

At 9,000 feet in the Mummy Range, the Colorado State University Mountain Campus is both tucked away and deeply connected to the world. Just 50 miles west of Fort Collins, it’s where, for half a century, Eco Experience has turned field trips into something far more lasting for the next generation of land stewards.

This valley holds centuries of history. The Arapaho, Mountain Ute and Cheyenne lived here first. In the 1860s, George Pingree established a logging camp along the South Fork of the river, and by the late 1890s, homesteaders had settled in the valley. Congress designated the land as the Pingree Park Campus, a forestry field school, in 1914, and CSU then purchased it in 1972, transforming it into a hub for student learning.

Every August through October, 1,800 students from the Poudre, Thompson, St. Vrain and Denver school districts arrive at the 1,600-acre campus for Eco Experience – three days of immersive learning in the Rocky Mountains.

Elementary school students learn about mountain meteorology, orienteering, forest ecology, outdoor skills, history and garbology. The campus also offers a stream ecology program, sponsored by the City of Fort Collins Utilities Department, that teaches youth about river health and the interconnectedness of water.

Nature is the classroom, but the curriculum extends to a ropes course, climbing wall and a full-day hike. Students can choose a 2-mile loop around the valley

or a 12-mile trek into the alpine tundra. Along the way, they learn Leave No Trace principles, hiking preparedness, wildlife observation and teamwork.

“For many students, it’s the first time they’ve hiked, been away from home or taken off their shoes and put their feet in the river,” said Jessica Smolenske, the Mountain Campus assistant director of events. “It’s profound to give them a connection to nature they don’t get day to day.”

Smolenske knows the impact firsthand. Since attending field courses as a CSU Warner College of Natural Resources student, she’s worked her way from Eco Experience instructor to assistant director in 2019. During her first year as an instructor, she watched fifth graders identify macroinvertebrates – signs of a healthy river ecosystem – near Cirque Meadows. “Being able to facilitate those ‘a-ha’ moments is rewarding,” she said. “These childhood experiences lead to a love of the environment for the rest of their life.”

Phillip Chavez agrees. Attending as a student in 1996 drove him to study natural resources at CSU and return as an instructor in 2009 to teach about the land’s Indigenous history. Today, he is the Tribal Outreach Coordinator at Trees Water People in Fort Collins – a career path inspired by his time at the Mountain Campus.

“These mountains foster a human connection and it allows our imaginations to grow. Seeing my kids go through the same experience is very special,” Chavez said.

Chavez’s three children have attended the program, continuing a generational tradition. For thousands of Northern Colorado students, the Mountain Campus stitches generations together through shared moments in the high country.

“My favorite thing about this place is that it’s not just special to me. It’s special to everyone,” Smolenske said. “That sense of place and belonging is everything here.” While some lessons fade, those learned at Mountain Campus last a lifetime.

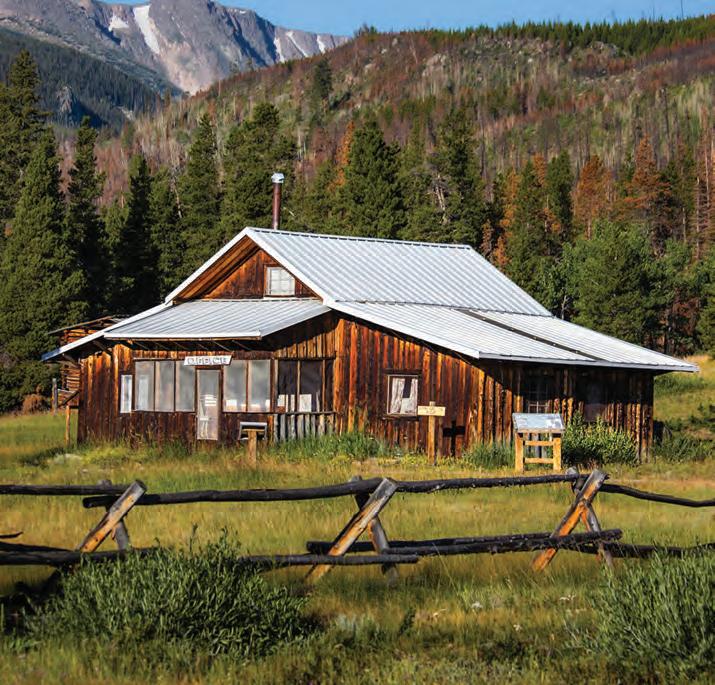

In the early 1900s, Hazel and Frank Koenig homesteaded in the valley where the Mountain Campus now stands. Their land became CSU property in 1972, connecting past and present through education.

With more than 200 plate designs, there’s one for nearly every passion, pastime and punchline.

by PETER MOORE

MY WIFE AND I drove from Pennsylvania to Colorado in 2017 to begin our new lives out west. As we crossed the Great Plains, I saw plenty of Colorado plates also rushing toward the Rockies. I looked forward to the moment when I could swap out “You’ve got a friend” for the green-and-white mountainscape of Colorado.

In Colorado, vanity isn’t just a mirror thing – it’s stamped in metal and bolted to your bumper. With more than 200 designs – from somber memorials to sly inside jokes – our bumpers double as billboards for who we are, where we came from and what we love. Whether you’re touting your alma mater, cheering for the Nuggets or joining the mysterious “Support the Horse” brigade, there’s a tag for nearly every passion, pastime and punchline.

We visited the DMV in Fort Collins soon after arriving – not typically a celebratory moment. A clerk shuffled our paperwork, and after many questions about insurance, finally handed over our new plate. “Congratulations,” he said. “You’re one of us now.”

For $60 plus a $25 annual renewal, your plate can trumpet that you graduated from the University of Colorado, joining 12,047 plate-owning alums. Or you can join 1,648

VANITY Thy Name is Colorado

Nuggets fans hyping our hoopers. The most popular specialty plate, driven by 68,369 Coloradans, reads “Celebrate Life,” memorializing the twelve students and teacher who died in the Columbine shootings. Proceeds benefit causes from hospice care to juvenile diabetes – and, cryptically, “Support the Horse.” (Who doesn’t love that red-eyed “Maverick” at DIA?)

The single most popular plate isn’t a cause at all – it’s black. Reintroduced in 2022 after being phased out in the 1950s, it’s a throwback to the days before plates became marketing slogans (“Virginia is for Lovers,” “Idaho Potatoes,” “Maine Vacationland” or Kansas’s current “To the Stars”). Some 393,711 Coloradans chose black. The reintroduced blue and red plates each have about 14,000 fans, far more than “Honorary Consul” with zero takers or “Olympic Committee,” a retired plate perhaps useful only for bribing your way to a Winter Games bid.

The all-time champ, though, is the classic white-mountain-green-sky plate, with 3,656,024 on the road. Conceived by Governor Stephen McNichol, designed by Bill Condit and released in 1960, its ridgeline is said to resemble the view from Cañon City – fitting, as you’ll see.

I learned all this from Colorado License

Plates: The First 100 Years – 1913-2013, the definitive book on the subject. At the Berthoud Library, co-author Tom Boyd slid the lavishly illustrated volume across the table to me.

Born in Colorado Springs in 1946, Boyd has collected that year’s plates from every county. He’s also led the Colorado branch of the Auto License Plate Collectors of America (ALPCA). If 3,000 members of his group petitioned the DMV, they could get their own ALPCA plate.

That’s good news for anyone. Rally 3,000 supporters for your idea – Rockies Baseball Optimist Society, Rocky Mountain Oyster Appreciation Club, Colorado Natives Against People Who Move Here from Texas – and you can apply. If approved, you can launch your own plate.

“I’ve always watched license plates,” Boyd said, citing a fascination with numbers. “And I noticed my father watching them too.” He told of a 1963 Wheaties promotion: send a box top and $1 and you’d get a full set of miniature state plates. Boyd got the dollar from his mom, with one condition from his dad – the cereal box had to be empty first. He didn’t, in fact, eat all his Wheaties, but it became the breakfast of champions for his collecting habit.

Colorado’s many license plate designs reflect the state’s diverse drivers. Inmates at a Cañon City prison’s manufacturing plant prize the chance to craft these colorful canvases.

He began with Colorado’s 1976 Bicentennial plate, marking both the nation’s 200th birthday and the state’s centennial. Soon he was pawing through garage-sale boxes, joining ALPCA and even arranging a tour of the Colorado Correctional Facilities plant in Cañon City – where, yes, all our plates are made by prison inmates.

“It’s considered a plum job if you’re a prisoner,” Boyd said.

Some wits take their creativity to personalized plates, as long as they stay within seven letters, spaces or numbers. Boyd once drove behind a Colorado plate reading INVUQT. It looks like an Inuit word until you sound it out: “I envy you, cutie.”

The DMV wouldn’t share its favorites, but said there are 78,000 personalized plates in Colorado and that “Coloradans are very clever and creative.”

Sometimes too creative. The state’s “prohibited/offensive” list rejects hopeful entries from 1BADSOB to 1HOTD8. Many others are so obscure you can’t tell whether to be offended.

When I applied for plates in 2017, my beloved Chicago Cubs were only months removed from their first World Series win in 108 years. I should have claimed CUBSWIN. But maybe that’s offensive to Rockies fans.

STATE SYMBOLS

Test your knowledge of Colorado’s important icons. by CHRISTOPHER

SHORT

GENERAL

1

A ribbon on the state seal contains two words: “Union,” and what related 12-letter word that contains all the letters of “union”?

2 In the official summer heritage sport, the human competitor guides the animal rather than riding it. Name that racing animal?

3 The bighorn sheep has been part of Chrysler branding since about the same time the Black Canyon of the Gunnison became a national monument, in what decade?

4

Colorado is the Centennial State because it was admitted 100 years after 1776. Had it been 150 years instead, it might have what even longer nickname?

5

Colorado’s state rock is a kind of marble named for the creek near which it’s found. That creek shares its name with what pagan holiday that turned into Christmas?

6

Speaking of Christmas, the state tree is what kind of conifer that’s often used for Christmas trees?

a. Fir

b. Pine

c. Spruce

7

Colorado’s beautiful “redblooming” state cactus is named for what style of wine?

a. Burgundy

b. Claret

c. Merlot

8 The columbine flower ultimately gets its name from the Latin word for what bird?

a. Dove

b. Hawk

c. Starling

9 The state gemstone – totally different from a state rock! –is what blue birthstone?

a. Alexandrite

b. Aquamarine

c. Tanzanite

10 The subject of Rocky Mountain High is trying to understand the serenity of… what exactly?

a. A lake

b. The sky

c. Nuggets Hall of Fame center MULTIPLE CHOICE

e grandeur of a bygone era awaits you at Rosemount in Pueblo! Built in 1893, this 37-room, 24,000 square-foot mansion was the family home of prominent businessman John A. atcher and his family. Take a guided tour of the mansion, and step back in time.

Tuesday-Saturday • 10 am–2:30 pm

11

Clarissa had a pet Western painted turtle on Clarissa Explains It All.

12

Like so many Coloradans, the Stegosaurus – Colorado’s official state fossil – was vegetarian.

13

By granting official status to square dancing, Colorado is part of a chain of 19 such states from California to Massachusetts.

14 In 2013, Colorado adopted rescue animals, so to speak, as its official state pet.

15 The state mineral – different from a state rock and a state gemstone! – is zinc. TRUE OR

No peeking, answers on page 51.

Experience historic charm at Frisco Lodge. Our exceptional hospitality, a ernoon wine and cheese, award winning courtyard, outdoor hot tub and romantic replace are just a few reasons our guests rated us the #1 bed & breakfast in Frisco and all of Summit County!

See why our guests think we are the best

www.friscolodge.com 1-970-668-0195

Main St | Frisco, CO

EDITORS’ CHOICE

photograph by VIC SCHENDEL

AFTER 30 YEARS in financial services, Vic Schendel of Fort Collins quit – work had contributed to stress that threatened his health – and he took up photography at the recommendation of a friend. Several years into his new career, another friend let him know about a fox he had spotted outside an abandoned home.

Schendel spent every day in the yard, arriving at 7:30 a.m. or 8, for two months, March to May, sitting in a discarded, rusted folding chair he found on the site. The property was overrun with untended trees and vegetation, plenty of places for a fox to hide.

He’d bring a lunch and stay till well after noon. When it wasn’t too cold, the fox would emerge from under the home’s foundation. He took note of the paths the fox would hunt, bringing back a snake and other food, or chasing a cat.

“She was skeptical of me, but not overly bothered,” Schendel said. She became a “friend,” sitting within a yard of Schendel. Then, one day, the fox was gone. He never saw her again.

This photo was shot with a Canon 7D, at ISO 1250, f7.1 for 1/400 of a second.

SUBMIT YOUR BEST photographs for the opportunity to be published in Colorado Life. Send digital images with descriptions and your contact information to photos@coloradolifemag.com or visit coloradolifemag.com/contribute.

SMALDONE

DENVER’S MOB FAMILY

Brothers Clyde and Checkers Smaldone built their mob empire from Gaetano’s, the family’s North Denver restaurant – a neighborhood landmark that still stands long after the criminal enterprise faded.

by MATT MASICH

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the September/October 2012 issue of Colorado Life. A reader favorite, we’re pleased to share it again.

Clyde Smaldone moved easily between mob bosses like Al Capone and Carlos Marcello and Colorado governors. Arresting officers and friends alike called him a gentleman. Here, Mamie Smaldone stands with her six sons outside the

THE LITTLE ITALIAN restaurant on northwest Denver’s Tejon Street has a big reputation, and not just for authentic food. From the time Gaetano’s opened in Denver’s Little Italy neighborhood in 1947, everyone knew it as the mob’s hang-out. The restaurant’s owners, the Smaldone family, simply called it “the place.”

In the 1950s and ’60s, the Smaldone name was notorious in Denver, instantly recognized as the strong arm of the mob. Banner headlines across The Denver Post read “Smaldone Brothers Get 60year Terms” and “Verdict Spells End for Smaldone Gang.”

Gaetano’s was the crime family’s headquarters, and the people hanging around the wood-paneled restaurant were a who’s who of the Colorado underworld.

You could find family patriarch Clyde Smaldone – “Gaetano” is the Italian equivalent of “Clyde” – seated at the bar, always at

his spot furthest from the door. Clyde looked every bit the part of an Italian-American mob boss, of average height and above-average weight, dressed immaculately in expensive suits and the look punctuated by an ever-present cigar.

Besides his intellect, Clyde was known for his talent for making friends, whether it was with Mafia kings like Al Capone and Carlos Marcello, or Colorado Gov. Ralph Carr. Colleagues and arresting officers alike described Clyde as a gentleman.

Clyde and his younger brother Eugene, who went by Checkers, often would visit with the patrons at Gaetano’s, inquiring about the food that was in the early days prepared by their mother in the restaurant’s kitchen.

Like a good-cop, bad-cop routine, Checkers was the Smaldone with the tough-guy reputation. He had the closest ties to the feared Mafia bosses to the south in Pueblo.

But Checkers wasn’t all intimidation; with a few drinks under his belt, those at the bar would hear him launch into an impromptu one-man opera performance.

In later years, Clyde and Checkers were less involved in the family’s rackets, and youngest brother Clarence, known as Chauncey, took over. Chauncey, the handsomest of the brothers, had a favorite spot at Gaetano’s at a table in the far back (Table 404 to the servers who work there today), where you’d see him eating his now-famous “Chauncey Burger” – a half-pound of ground chuck, melted mozzarella and roasted Italian peppers, served with a side of the house red sauce. The Chauncey Burger is still on the menu.

From Gaetano’s, the Smaldones ruled North Denver from the 1930s through the 1970s. But you won’t find them there anymore; the three brothers have passed away, and the family sold Gaetano’s in 2004.

Though the Smaldones sold Gaetano’s in 2004, the restaurant still exudes its mob-era atmosphere, with booths that recall the way patrons once gathered decades ago.

Still, the place is saturated with their memory. The dining room looks the same as the last time the Smaldones remodeled in 1973, and you can sit at Clyde’s favorite barstool.

Most of the patrons are local, and many of them knew the Smaldones, says Gaetano’s general manager, Don Knowles.

“Ten out of 11 of them have nothing but great things to say about the family,” he said. People tell him that no one in the neighborhood ever went hungry, no matter how bad the times were – the Smaldones would always help out.

THAT’S THE TRICKY thing about the Smaldones. Depending on who you talk to, they were either modern-day Robin Hoods or shoot-’em-up Mafiosi straight out of a gangster flick. In reality, they were neither.

There’s no doubt that the stories about their generosity are true. Even in their heyday, when The Denver Post waged a media campaign against organized crime, the newspaper’s Roundup Magazine gave Clyde and Checkers credit for helping destitute North Denver families with milk and groceries, secretly paying college tuition for local boys and funding Catholic orphanages.

“Each Christmas they donate quantities of athletic equipment to the homeless waifs and ‘feed ’em good’ at Gaetano’s,” the magazine wrote.

There also was a darker side to the Smaldones. No matter how you spin it, they made their money by breaking the law – first bootlegging, then running gambling rackets and loansharking. Some of the people associated with them died violently.

CLYDE AND CHECKERS, born in 1906 and 1910, respectively, were the oldest sons of the nine children of Raffaele and Mamie Smaldone, immigrants from Potenza, Italy. It was in Denver’s north-side Italian enclave during Prohibition that they started building their empire. As teenagers, they would find where the bootleggers stashed their illicit booze. Then they stole it and sold it to speakeasies.

They graduated into making their own liquor, then started trucking in premium whiskey from Canada, and finally, buying it from Al Capone’s Chicago outfit.

Colorado’s rival gangs fought for control of bootlegging, and during Prohibition there were some 30 gangland murders. In the south, the Dannas out of Trinidad and the Carlinos from Pueblo fought for supremacy.

In Denver, the Smaldones’ employer was Joe Roma, the 5-foot-1 mob boss kingpin known as “Little Caesar.” And like his namesake, Roma met a bloody end when in 1933 he was shot seven times – six in the head – in his North Denver

home. The killers were never prosecuted, and the Smaldones always denied involvement, but Roma’s death meant that the Smaldones were undisputed kings of the Italian mob in Denver.

Clyde and Checkers spent the last days of Prohibition in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, returning to Denver in 1934 after 18-month stints to find their bootlegging business obsolete. They moved seamlessly to gambling, where they worked with Ova Elijah “Smiling Charlie” Stephens, who ran a high-end restaurant that doubled as a casino. Stephens, Clyde and Checkers were convicted in the car-bombing of Stephens’ erstwhile casino partner and were sent to state prison at Cañon City.

After the Smaldones were freed in the early 1940s, they found their greatest success through their mother’s cooking. In 1947, the brothers founded Gaetano’s, which thrived.

That same year they opened a casino, dubbed Monte Carlo, in the old mining town of Central City. Respectable people from Denver and across the state flocked to play craps, roulette and slot machines. Clyde’s charm persuaded city officials to look the other way, and as a token of thanks, the Smaldones paid for new waterlines for Central City, restored dilapidated houses and funded a school lunch program.

“If you know how to talk to people you can make money anywhere and you don’t have to say, ‘It’s a bribe,’” Clyde said years later.

The Smaldones’ casino in Central City was illegal at the time, but Clyde predicted such gambling would be legalized if the government knew how much money there was to be made. But it took more than 40 years before the state approved gambling in Central City and other mountain towns, where many casinos now do booming –and legal – multimillion dollar business.

The Smaldone gambling racket spread across Colorado in the late 1940s and included at one time more than 500 slot machines. They also did a lot of business taking bets on sporting events.

During Prohibition, government agents smashed moonshine stills. The Smaldones soon shifted to running gambling rackets after liquor became legal.

The Smaldones’ success rankled prosecutors, who made an all-out push to get them. Checkers was charged with tax evasion and was to stand trial. When the Smaldones sought out potential jurors to coax a “not guilty” verdict, they were accused of jury tampering. They were tried and convicted, but the judge’s ruling was thrown out. Instead of going through a second trial with a new judge, Clyde and Checkers worked out a plea bargain in which they would each serve three concurrent four-year terms. But the judge changed the agreement to three consecutive terms, and the brothers were sentenced in 1953 to 12 years in Leavenworth.

The family business continued with the youngest Smaldone brother Chauncey, taking control, along with nephew Paul “Fat Paulie” Villano. Clyde retired from his role when he got out in 1963, but Checkers stayed involved. In the 1970s, the family struggled with independent bookmakers who no longer recognized the Smaldone control of gambling in Denver. One such upstart, former University of Colorado football player Skip LaGuardia, was killed by a shotgun blast to the face outside his Denver home. The Smaldones were widely thought to be behind it, but no charges were made.

The Smaldones’ power continued to fade as the main players grew old and no one was recruited to take their place. By the time Checkers was sentenced to another prison term in the 1980s for loansharking, the Smaldones had effectively ceased to exist as a criminal enterprise in Denver.

THE MOST NOTICEABLE change at Gaetano’s since the days when the Smaldones held court is the tongue-in-cheek slogan adopted by the new ownership: “Gaetano’s – Italian to die for.”

Gene Smaldone notices it when he slides into a booth for lunch and for a magazine story interview. The booth seat is black, and there’s a white cloth on the table. Gene orders the rigatoni with red sauce.

Gene is the elder of the two sons of Clyde and his wife, Mildred. Gene is trim and looks two decades younger than his 81 years, and in his khakis and green windbreaker, he comes across nothing like his suit-wearing father. He never got into his family business, never even smoked or drank. He was a North High and University of Denver football star who followed that path into coaching before entering a long and lucrative career in real estate. Gene shrugs off the mention of his family as mobsters.

“That was just my dad,” he says. “These other guys were my uncles and friends. I thought we were just like any regular family.”

But the legacy follows him, and he’s come to embrace it, focusing on the good things his family did. He helped arrange the interviews that provided the raw material for a 2009 book, Smaldone: The Untold Story of an American Crime Family, written by friend and retired Denver Post columnist Dick Kreck, who joined us at the table.

“You won’t find anybody in North Denver who has anything bad to say about them, because they gave money to the orphanages and the church and people on the street,” Kreck said.

The Smaldone name still means something to people here, Gene said. He talks about his wife’s recent grocery shopping expedition, how when it was time to pay, the woman at the checkout stand noticed the name on the credit card.

“She says, ‘Oh, are you related to the Smaldones?” Gene recounts. “And Linda says ‘yes.’ And so the clerk says, ‘Can I carry your groceries out for you?’”

But being a Smaldone can be something of a burden, too, and name recognition hasn’t always been so kindly expressed. We talked a few days later with Gene’s younger

brother, Chuck, who recalled his first day of first grade.

“I can remember they were calling the roll and there was a dead silence” after his name was called. “The teacher asked if I was part of the gangsters, or something like that, in front of the whole class,” Chuck said. “I was mortified.”

His parents, especially his mother, were adamant that Gene and Chuck not follow in their father’s line of business. Clyde had chosen his path almost out of necessity, to support his parents and younger siblings, and he never finished high school. He made sure his sons went to the best schools and got college degrees.

“My mother told my brother and I that because of our name, we had to be twice as good as everybody else, because people expected us to be bad,” Chuck said. Like his brother, Chuck defied expectations, making a lawful living as co-owner of Duane’s Clothing menswear shop in Arvada.

When weighing the Smaldones’ crimes against the good things they did for people, the fact that they steered their children away from the family business – and in so doing guaranteed the end the criminal empire they built – is perhaps another weight on the “good” side of the scale.

But the Smaldone name still has the power to sparks imaginations. After Kreck’s book on the family came out, Gene and Chuck started fielding calls from people interested in telling the Smaldones’ story in a movie; they recently met with an established screenwriter to work on a treatment. If their family appears on the big screen, the brothers want it to break from mob clichés and show the way the Smaldones helped others.

Hollywood depictions of mobsters are sometimes ridiculous, Chuck says, singling out The Sopranos as making them look “dumb.” The level of violence is always amplified in the movies, but some films hit closer to home. The wedding scene that opens The Godfather was reminiscent of Gene’s wedding in 1951, where 500 guests were invited, and 1,500 showed up.

And so the Smaldone legacy lives on, somewhere between myth and reality, between good and bad, and possibly, on the big screen, where immortals are made.

FA Worth Keeping Wilderness

story

by DEAN ALLEN

A ghost cabin, serrated peaks, and a herd of high-country neighbors reveal why Colorado’s wild places matter.

ive o’clock. A whisper woke me. Pale light shone through the translucent blue Dyneema fabric of my tent, revealing a single hole in the clouds on the horizon. To the west, only darkness – a black veil that dawn’s first light couldn’t penetrate. A 20-minute hike brought me to the ridge crest with cold morning rain on my heels.

The oppressive weight of the sky bore down on the texture of the earth. With enough time, it would press the young, rugged peaks of Eagles Nest Wilderness into rounded humps. And me, caught in the middle of Titans, a witness to their timeless struggle. With bated breath, I hoped for light. I almost didn’t have the chance.

It started with a problem more often found in big cities: I couldn’t find a place to park in Vail. That’s life in today’s resort towns, where tourism, remote work and second-home owners have brought more people to the mountains than ever. An online search told me there was no overnight

parking at the Gore Creek Trailhead, so I left my car in town and took a bus. Two hours later, $156 lighter and mildly sunburned from waiting at the bus stop, I finally stepped off at the dusty trailhead, more than ready to swap asphalt for alpine wilderness air.

But there is still much to celebrate, because the glowing blue jewel we call Earth exists. We were blessed beyond measure to have been created here. Let me tell you what I saw once I stepped into God’s country.

There was a time when people were free to roam this land, settle where they wished and survive however they could. How different their lives must have been, connected to the rugged wilderness so profoundly. I found a remnant of that old life that first afternoon, a weathered log cabin clinging to the edge of tree line. Who built it, and why? What was it like to live here, where storms roll in without warning and winter lingers into July? How long did they stay? And, more importantly, did I have the courage to spend the night there?

Wilderness is not a luxury, but a necessity of the human spirit and is as vital to our lives as water and good bread.

– Edward Abbey

I MIGHT HAVE, if not for the wildlife. When a mouse scurried across the toe of my sleeping bag, I gave up on the idea and pitched my tent outside. Near midnight, I went back in with my camera. Rusty hinges groaned as I eased the door open. My headlamp swung from a wire in the rafters, throwing long, uneasy shadows through the doorway and windows, the kind you half expect to see move. When I returned to my tent, the sound of foraging rabbits was thunderous in the stillness, and I slept lightly the rest of the night.

By 3:45 a.m., I was on the move again. The moon had dropped below the horizon, leaving me in darkness. My headlamp guided me around the lake and up a steep slope toward a high, serrated ridge I had scouted the day before. Astronomical dawn gave way to nautical twilight as I scrambled over alternating bands of tundra and talus, rocks skittering down behind me. “Don’t give up now,” I told myself as the long night faded. Near the crest, I found tiny alpine flowers sheltering against stones, and I understood their beautiful perseverance.

After returning to my tent from my high-altitude adventure, I grabbed my water filter and bag to get some much-needed hydration. On my way across the tundra to the lake, I saw a white dot turn into a sprinting mountain goat. A billy was running straight toward me at full speed. Twenty yards away, he veered slightly, then beelined it to my tent.

I knew what he was after.

My urine.

The northeast ridge of Valhalla Peak climbs to 13,202 feet, where columbines and other wildflowers spill from rocky outcroppings, and mountain goats wander the heights, pausing to draw salt from stones brushed by passing hikers.

THERE ARE MINERAL licks where mountain goats can get the salts they need to survive, but why bother when there are people around? After a quick investigation, he found the rock where I had relieved myself and set to work licking it. The upside for me was that he made a stationary subject to photograph.

The mountain goats in this area are as thick as people in the resort towns. My last night was spent away from solitude and smack in the middle of a community of creatures. Laughing, bleating, splashing, running, chasing, munching, exploring and simply living life in the great outdoors.

Oh, and the mountain goats were doing all that, too.

How different are we from them, really? It was magical observing the nannies watch over their kids playing King of the Hill. They were unconcerned about me. I would feel a presence behind me as I sat watching, and there would be a goat peer-

ing over my shoulder. At the same time, I could hear the teenage boys across the lake whooping. As the lingering evening settled, the joy of living infused the crystal air, an abundant energy that cannot be found indoors.

Maybe it is not a bad thing to have timed entry permits and shuttles to control and monitor human use of the wilderness. $156 was a steal for what I experienced. Edward Abbey, in his 1968 opus Desert Solitaire, went so far as to recommend that no personal cars should ever be permitted in national parks. He suggested that we use shuttles, bikes, horses or our feet to explore the natural treasures that have been left in our care.

As it turned out, Vail is doing its best to juggle all of these factors. The new trailhead wasn’t far away, and I found it easily. It was hard to miss with the brand new 100-car parking lot attached. Had I called a human instead of using Google, I would

have known that there was now a free overnight parking option.

And the light?

Well, I covered my camera the best I could during the rain. Meanwhile, some sort of divine synchronicity stepped in and lined everything up for a single person, me, to see. Serrated peaks led upward from flower-encrusted tundra. A rocky chute dropped precipitously to the gorge below. And a hole in the clouds, at least fifty miles distant, had a small splash of color. My wait didn’t last long.

The rain passed by, infusing the ridges and peaks with moisture-laden atmosphere. The hole widened slightly. Guided by divine providence, the sun found the sky’s only weakness. And His glory radiated through.

A miracle.

It happens every day, on this glowing blue jewel we call home.

It’s worth keeping.

Treats

Easy go-to favorites for a day in the sun

recipes

and photographs by

DANELLE McCOLLUM

SPENDING A DAY poolside is a favorite pastime during a hot, Colorado summer. What better way to decorate the day than with a fresh, fruity and sparkling lemonade and a pair of easy-breezy treats? This trio of colorful culinary picks is sure to keep you fueled up for the fun and coming back for more. Don’t forget sunscreen.

Pineapple Coleslaw

This sweet and tangy coleslaw serves as a great side dish, or unique addition, to a number of family barbecue staples. The dish’s dressing is composed using ready-found ingredients and gives the whole bowl a fresh feel. Add a jalapeño pepper, or two, to kick it up a notch.

In a medium bowl, whisk together yogurt, vinegar, pineapple juice, brown sugar, salt and pepper. Add the cabbage, carrots, red bell pepper, green onions, cilantro, pineapple and jalapeño. Toss to coat well and serve immediately.

1/4 cup plain yogurt

1 Tbsp apple cider vinegar

3 Tbsp pineapple juice (reser ve from canned pineapple)

1-2 Tbsp brown sugar

3 cups shredded cabbage

1 cup shredded carrots

1 red bell pepper, diced

1 jalapeño, seeded and chopped (optional)

1/2 cup chopped green onions

2-3 Tbsp chopped fresh cilantro

11/2 cups canned pineapple tidbits (reserve juice for dressing)

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 8

Italian Sub Pinwheels

This grab-and-go pinwheel is the perfect finger food for little hands taking a break from the doggy paddle. Different ingredients can be subtracted to accommodate picky eaters, but no matter which way it’s sliced, this culinary creation is tasty!

In a medium bowl, combine cream cheese, salad dressing mix, banana pepper, red onion, green onion, red pepper, olives and shredded cheese. Mix well.

Spread about 1/4 cup of the cream cheese mixture over a tortilla. Place 3-4 slices each of pepperoni and salami over the cream cheese mixture, leaving about 1/2 inch around the edge. Don’t add too much meat or the tortilla will be hard to roll.

Place a leaf of romaine lettuce in the center of the tortilla. Roll up tightly. Place wooden picks about 1 inch apart down the center of the rolled tortilla. Cut in between the picks to form pinwheels. Repeat with remaining tortillas and fillings. Refrigerate until serving.

4-6 large flour tortillas or wraps

8 oz cream cheese, softened

1 Tbsp Italian dressing mix

2-3 Tbsp finely chopped banana peppers

1/4 cup diced red onion

2-3 green onions, thinly sliced

1/3 cup diced red pepper

1 4-oz can chopped black olives, drained

1/2 cup shredded Mozzarella cheese

6 oz sliced pepperoni

6 oz sliced salami

8-10 romaine lettuce leaves, washed, dried and core removed

Ser ves 12

What’s in Your Recipe Box?

Sparkling Blueberry Lemonade

Complete with fresh, beautiful blueberries and a kick of sparkling water (or ginger ale), this flavor-packed lemonade is sure to delight even the pickiest of poolside guests. This recipe could be swapped out with other fruits and served to adults with an extra “kick” – time to sweeten up summer.

Add lemon juice and sugar to a 12 oz glass. Fill about a third full with blueberry juice. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Add ice, if desired, then top off glass with sparkling water or ginger ale. Garnish with fresh blueberries and enjoy.

2 Tbsp fresh squeezed lemon juice

1-2 Tbsp sugar

Blueberr y juice

Sparkling water or ginger ale Fresh blueberries, for garnish

Ser ves 2

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

OUR STATE THROUGH THE WORDS OF OUR POETS

On the trail, each turn is an invitation to notice the small wonders and quiet stories of nature. Step after step, our poets immerse themselves in the sounds and sights, reminding us that it’s about the journey, not the destination.

On the Trail

Robert Basinger, Rifle

On the trail, a “tender” foot

My vibram soles will not stay put I step it up, then catch my breath

I’m getting close, but I’m not there yet.

We are all together, a “family”

I smelled the roses, and hugged a tree

A granite staircase, a babbling brook

So many things say, please take a look.

And on the trail, I did not get lost I found that penny that I had tossed Songbirds are singing, but I can’t stay

A string of bread crumbs lead the way.

The Pinto, 1980

Diann Logan, Arvada

The rocking horse won every race when I was a jockey. The stick pony was sure-footed and fleet when I was astride. None of that prowess will help me now, Saddled up on this stiff-gaited little pinto, Out for a jaunt on the east side of Cherry Creek State Park.

There is nature to be seen and sensed here,

But I can only focus on staying mounted.

My daughter ahead of me on the chestnut

Sits the horse like she was born to it.

I hear her chirping clucking cooing voice, Her intimate conversation with the chestnut.

The pinto knows the route by heart, Traversed day after day with paying burdens on board. A bowl of oats waits back at the stable.

The pinto sets a pace that will get us there pronto:

Walk walk walk trot trot

Trot walk trot walk walk ... trot!

I must endure it, This tooth-clacking, tailbone-assaulting adventure. I endure it

For my daughter’s sake.

She glances back at me for a moment, Her face the definition of pure joy.

She begged for this outing for her birthday, And I agree with the pinto, Can’t wait to get back to the stable.

Some of us are better off behind the wheel Than behind the pommel.

On the drive home, my daughter is euphoric, Regales me with extensive details about the chestnut –Date of birth, food preferences, mother’s maiden name. Flushed and breathless with excitement, She gushes and relives every single moment of her birthday gift.

Decades later, she is an accomplished rider And I have the memory to cherish, My last time on horseback, Our hour on the trail together.

Zapata Falls

Lynda Mann Johnson

Brush Prairie, Washington

No maps or GPS

Just dad’s skilled guess.

Seventy-five years have passed

But my rich memories last.

No trail beyond monument sands

Perhaps on land-grant lands

A flume-lined wall

Hints at the hidden fall.

A chasm exists now exposed to sky

Once a cave with teary eye.

Zapata Falls, men, and nature

Now present a different venture.

I think I prefer those darkened walls

And the treasure of mist and falls

Rewarding a day tough spent

The unmarked way we went.

The Elk

Alyssa Tatum, Denver

Still in the shadow, a silhouette stands, Tree-like, its limbs carved from the land. Roots stretch deep beneath the earth,

As if the mountains themselves gave birth. If you’re quiet, for a moment, You can hear his symphony –The dark river, coursing through his veins, The wind, his breath among the pines, Chimes of chickadees, the beat of his heart. He rises from a bow –

I half expect him to flee at the sight of me –Instead, he stares, And turns, dissolving into the mist, an apparition. The valley holds its breath, then A call, a haunting, barely a whisper at first,

But the echo cuts like a pocketknife through the thin morning, It grows louder, until it fills the air, thick as sap, and sticks heavy to my soul.

In Emerald Valley

Sandy Morgan, Colorado Springs

I found a spotted feather on the trail among columbine, roses and wild strawberries.

Back at the trailhead I asked if anyone recognized it. Exotic hawk? Ptarmigan? Guardian angel?

Spotted towhee was the consensus. Nuts. I was hoping for a rare find, a noteworthy feather for my cap.

Ubiquitous as wild roses, the towhee. Hand-crafted by God – who also adores columbine and wild strawberries.

Send your poems on the theme “Stillness” for the January/ February 2026 issue, deadline Nov. 1 and “First Thunder” for the March/April 2026 issue, deadline Jan. 1. Email your poems to poetry@coloradolifemagazine.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

IN FULL COLOR Freedom

For nearly 50 years, Colorado Springs’ Labor Day Lift Off has filled latesummer skies with balloons and the hearts of those who chase them.

by TOM HESS

IN THE COOL twilight of an early September morning, the sun has not yet risen high enough to reflect off the windows of the Summit House on 14,115-foot Pikes Peak, America’s Mountain. Eight thousand feet below, Colorado Springs still slumbers. Not so for the 75 hot-air balloon pilots gathered in Memorial Park. They’re awake, caffeinated and facing a deadline: if they wait too long, the sun will heat the air enough to make flying in the Labor Day Lift Off impossible. For nearly half a century, the Labor Day Lift Off has filled Colorado Springs’ late-summer skies with color, drawing pilots, specialty balloons and crowds that pack Memorial Park to capacity. What began in 1976 as a friendly race among a few friends has grown into one of the largest hot-air balloon gatherings in the Rockies. For those who fly and crew, it’s more than a spectacle. It’s a reunion, a proving ground and a celebration of the freedom found only in the open sky.

Before sunrise, the park hums with fans and burners as pilots ready their balloons. In moments, the quiet will give way to a sky filled with color drifting above Colorado Springs.

OVER THE THREE-DAY weekend, attendance tops 200,000. Families on blankets, coffee in hand, fill the park, and organizers peg the event’s annual local impact near $20 million. After the morning lift-offs, evenings bring the balloon glow, when tethered balloons fire their burners in unison to light up the park. In recent years, the Lift Off has added a nighttime drone light show. Hundreds of illuminated drones rise into choreographed formations above Memorial Park, tracing shapes of balloons, mountain peaks and even the Colorado flag – a new spectacle alongside the glow that lights up the holiday sky.

Pilots wait for accurate weather readings before they commit to launch. They cannot fly in strong wind or rain, and if gusts exceed 10 mph, the morning’s

flights are scrubbed.

That is why veteran local pilot Skip Howes watches weather radar on his phone and gives a 6:15 a.m. briefing to the pilots clustered around him. A pie-ball, a small helium balloon, is released to reveal wind patterns at different altitudes. On most mornings, winds drift southeast, away from denser parts of the city – though the air does not always cooperate. Shifts can be subtle, with the second wave of balloons often following a different path than the first.

Today there is no wind above 10 mph at any level, and no rain in the forecast. Fans hum. Burners roar. Crew members grip propane burners with both hands, sending jets of flame deep into the balloon. Others pull on the fabric to widen the opening away from the heat. The bursts

sound like dragons breathing.

Most pilots decide whether to carry a guest. Kevin Cloney’s Chariot of Fire balloon has a clear front door on its basket, allowing passengers in wheelchairs or with mobility issues to step aboard. Most baskets require guests to swing their legs over the side – a climb higher than a horse’s stirrup. One passenger with a recent knee replacement finds the front door ideal.

Once aloft, Cloney points out that the air inside the balloon envelope is 230 degrees, while outside it is just 50. They travel at 7.8 mph. There is no jolt of motion, no sudden drop like in an elevator. Cloney lands on a small patch of grass at Atlas Elementary School to the southeast, where neighborhood kids run over to meet the pilot and pepper him with questions.

SOME PILOTS AIM for Memorial

Park’s Prospect Lake to attempt a “splash and dash,” skimming the basket across the water’s surface to create a wake. Photographers crouch for the perfect frame, hoping for a shot that will one day hang in an office or coffee shop. Sometimes the basket dips too deep and takes on water. A quick blast from the burner sends it skyward again. In decades of the Lift Off, no one has sunk.

This kind of excitement hooked some pilots when they were still kids. Jason Gabriel of Denver caught the bug at age nine. When he earned his hot-air balloon license in 2013, five bottles of champagne were poured over him. He spreads that happiness around, making friends in a dozen states. Labor Day is his can’t-miss event, and he flies with a team he calls “ambassadors of happiness.”

Specialty balloons have made memorable appearances – Darth Vader’s helmet at 86 feet tall, Yoda’s head at 62, and the Energizer Bunny with 60-foot ears. Gabriel and others fondly remember Dewey Reinhard, the event’s founder, who died in 2023. In 1976,

he and a few friends met in Black Forest for a race. Entry fee: a six-pack of beer. Reinhard grew up in Pueblo, near a B-24 base. His father would take him on Sundays to watch airplanes like the Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar, a World War IIera transport. He hoped the Lift Off would help build a freedom-loving aviation community in southern Colorado – a wish that has more than come true.

Skip Howes began ballooning two decades after high school with his wife, Debbie. He bought his own balloon in 1995 and earned his pilot certificate in 1996 – the champagne flowed. Most hot-air balloon baskets are square; Howes’ Wildfire balloon has a triangular basket, with propane tanks in each corner for more room. This year, he’s flying a banner for Colorado Springs Utilities with some of its employees aboard.

Howes relies on experienced crew, because ballooning is only as safe as the people who heat and handle the equipment. Among his veterans is Desiree Tucker, who has spent half her life at the Lift Off. She can’t imagine giving it up – even though

the sport has cost her half her lung capacity. Each Labor Day weekend, she rises at 3 a.m. without an alarm to help launch balloons from the dew-slick grass of Memorial Park with Pikes Peak in view. She has crewed for more than 100 balloons, including Vader, Yoda and the Bunny.

That commitment has come at a cost. Tucker has had four lung operations since inhaling and swallowing liquid propane when a fuel line wasn’t secured, burning a hole in her esophagus. She has also undergone two ballooning-related knee surgeries.

“I relate to NASCAR drivers,” she says. “They get hurt, they crash, but they don’t go home and never drive again. They love what they do. You pick yourself back up.”

And so she does, up before dawn, in the dew, under the roar of burners. Around her, dozens of balloons rise from Memorial Park, their colors reflecting in Prospect Lake as Pikes Peak towers above. For Tucker, Howes, Gabriel and the rest, the Lift Off is more than an event. It’s Colorado Springs at its most vivid – freedom in full color.

Balloons rise steadily from the dew-covered grass of Memorial Park – their reflections dancing in Prospect Lake as the early light spills across Pikes Peak.

COLORADO’S CALENDAR OF EVENTS

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

FESTIVAL

PUEBLO CHILE FESTIVAL

SEPT. 19-21 • PUEBLO

Downtown Pueblo lights up with the slow smolder of chile roasters and the crackle of local pride every third weekend after Labor Day. Now in its 31st year, the Pueblo Chile and Frijoles Festival is a fiery love letter to the region’s agricultural heritage.

Some 150,000 spice lovers descend on Union Avenue for three days of mild-towild fun. The undisputed star? The Mira Sol Chile. Grown only in the fertile, sunbaked plains of Pueblo’s Arkansas River Valley, this thick-skinned, heat-kissed pepper packs a punch.

Festivities coincide with prime roasting time – a rite of the season – and include street vendors, live music, cooking demos and a Chili and Salsa Showdown. At the infamous Jalapeño Eating Contest, brave

souls munch their way to mouth-numbing glory. Even sombrero-sporting pups strut their stuff during the Chihuahua Parade.

Early risers can catch the Balloon Fest lift-offs on Saturday and Sunday mornings, then stay late for the Saturday night balloon glow along the historic Pueblo Riverwalk – a serene pairing with the day’s heat and hustle.

The festival runs from 3 p.m. to midnight Friday, 10 a.m. to midnight Saturday, and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday. Whether you come for the flavor, the flair or the sheer festival fun, the Chile and Frijoles Festival proves one thing – Pueblo doesn’t just grow chiles, they know how to throw a red-hot party. pueblochilefestival.com, (719) 542-1704.

WHERE TO EAT CACTUS FLOWER

MEXICAN RESTAURANT

Didn’t get enough green chile?

Order the green chili plate with panfried potatoes, Spanish rice and refried beans – smothered in chili and cheese. 4610 N. Elizabeth St. (719) 545-8218.

WHERE TO STAY ORMAN MANSION

A lavish Victorian-style residence with eight bedrooms and some original furnishings. The warm oak trim, turrets and inner courtyard make for a luxurious stay. 102 W. Orman Ave. (719) 877-3170.

WHERE TO GO

HISTORIC ARKANSAS RIVERWALK

Thirty-two acres of urban walkway meander along the flowing Arkansas River through downtown Pueblo. On the water, gondolas and pedal boats transport visitors. 101 S. Union Ave. (719) 595-0242.

Pueblo’s famous Mira Sol Chile steals the spotlight at the city’s three-day festival that draws 150,000. Weekend activities consist of live music, contests and street vendors.

Each fall in southeast Colorado, male tarantulas roam the prairie in search of a mate – sometimes traveling more than a mile.

OUTDOOR

LA JUNTA TARANTULA FEST

SEPT. 26-27 • LA JUNTA

Each fall, the prairies of southeast Colorado get a little hairier.

That’s when male Colorado Brown Tarantulas emerge from their burrows and creep across the Comanche National Grassland in search of love – an annual mating ritual often mistaken for a migration. In La Junta, their skittering courtship is cause for celebration at Tarantula Fest, a two-day event that’s part science, part spectacle.

Festivities kick off Friday, Sept. 26, with tarantula talks by arachnid experts from 1–3 p.m. at Otero College, followed by a 3:30 p.m. screening of Arachnophobia at the Fox Theatre. From 5–8 p.m., join a guided bus tour to see the real stars in their natural habitat (registration is required).

On Saturday, Sept. 27, downtown La Junta goes full spider mode with food trucks, vendor booths, art activities and a classic car show starting at 9 a.m. The Tarantula Parade shuffles through town at 10 a.m., and activities like the Hairy Leg Showdown and 8-Legged Races keep things crawling. From 12–11 p.m., the beer garden serves cold brews alongside late-night entertainment.

Want to see the eight-legged critters in action? Bus tours resume at 5 p.m. Dig into a Chuck Wagon Dinner at the Otero Museum before heading back downtown

for live music to close out the evening –because when the tarantulas come out to tango, the whole town dances along. visitlajunta.net, (719) 468-1439.

WHERE TO EAT COPPER KITCHEN

This locally owned joint serves hearty breakfasts of biscuits and gravy and huevos rancheros in a wood-paneled diner. 116 Colorado Ave. (719) 384-7508.

WHERE TO STAY MIDTOWN MOTEL

Serving guests since 1950, this budget-friendly spot reflects the communal spirit of La Junta. It’s also within walking distance of restaurants and popular tourist spots. 215 E. 3rd St. (719) 384-8010.

WHERE TO GO KOSHARE ART MUSEUM

A repository of Native American art and artifacts that began as a Boy Scout troop project in 1930. Displays include pottery, textiles and art from the Cheyenne, Comanche, Pueblo and Navajo. Koshare dancers perform at 2 p.m. Saturday. 115 W. 18th St. (719) 384-4411.

OTHER EVENTS YOU MAY ENJOY

SEPTEMBER

Hispanic Chamber Chili Fest

Sept. 13 • Trinidad

Spice up September with this fiesta hosted by the Trinidad Las Animas Hispanic Chamber. Enjoy live music, local food vendors, craft booths and friendly horseshoe and cornhole competitions. Dancing encouraged, appetite required. 100 N. Convent St. (719) 845-7839.

Pickin’ in the Rockies

Sept. 14 • Loma

Bring your boots – and your best holler – for an award-winning roundup of gospel, bluegrass and country. The second annual festival packs in eight bands including Emily Ann Roberts and Bar D Wranglers. 1351 Q Rd. (970) 712-8783.

Smalltown for the Cause

Sept. 19-20 • Salida

Settle in for a weekend of yoga, river surfing, bike rides and music from Elephant Revival, Moontricks, Clay Street Unit and more. Started in 2009 to support global relief, this year’s funds benefit Hutchinson Ranch and the Colorado Tick-Borne Disease Association. 6700 Old Corral Rd.

The 39 Steps

Through Sept. 20 • Creede

Murder, mayhem and Monty Pythonstyle laughs race through 150 characters played by just four actors in this wildly inventive stage romp at the Ruth Humphreys Brown Theatre. 120 S. Main St. (719) 658-2540.

Craig Fall Fest

Sept. 20 • Craig

Alice Pleasant Park and downtown Craig burst into fall spirit with live music all day, a newly added car show spanning the 400 and 500 blocks of Yampa Avenue, spirited cornhole tournaments (benefiting the Moffat County Cancer Society), Western Colorado vendors, and a lively beer garden. A lively, family-friendly highlight of the season. (970) 824-2151.

OCTOBER

Cedaredge Applefest

Oct. 3-5 • Cedaredge

Since 1977, more than 30,000 visitors have gathered to honor Surface Creek Valley’s temperate climate, fruit heritage and award-winning apples and peaches. The event celebrates with live music, a 5k run, 5 Alarm Chili Cookoff, golf tournament, antique car and motorcycle shows, a pinup contest and a library book sale. Over 200 vendors showcase local art, food and crafts at venues all around Cedaredge. (970) 856-3123.

Brush Oktoberfest

Oct. 4 • Brush

Downtown Brush transforms the eastern corner of the state into a festive German hub – raise your stein to bratwursts, pretzels, live music, a vibrant beer garden, car show, kids’ games and even a mechanical bull. A free, all-ages celebration of community and tradition. (970) 542-3508.

Lamar Chamber Oktoberfest

Oct. 5 • Lamar

East Beech Street and the Enchanted Forest come alive with a beer garden, barbecue, burgers, pretzels, carnival games, inflatables and a 5k “Beers & Brats for Boobies” run from 11 a.m.-8 p.m. (719) 336-4379.

Freefall Bluegrass Festival

Oct. 10-12 • Vail

Free bluegrass fills Vail Village for the third annual festival with music from Sam Bush Band, Phoffman, Terrapin Family Band and more. Family fun includes food, drinks, kids’ activities and the Rock and Roll Playhouse for little rockers. freefallbluegrassfest.com.

Rocky Mountain Women’s Film Festival

Oct. 17-19 • Colorado Springs

The longest-running women’s film festival in North America returns for its 38th

year at Colorado College, filling theaters with documentary, narrative, short and animated films that spark conversation. Enjoy opening-night receptions, filmmaker Q&A sessions, engaging panels and more. (719) 226-0450.

Witch Paddle

Oct. 18 • Littleton

What began in 2021 as a small gathering has grown into a bewitching bash for 400-plus paddleboarders in witch costumes. Grab your broom – or paddle – and head to Chatfield State Park’s Swim Beach. 11500 N. Roxborough Park Rd.

World Singing Day

Oct. 18 • Boulder

Celebrate the 10th annual Pearl Street sing-along/ All ages and skill levels are welcome to belt out the Beatles, Taylor Swift and more in this spontaneous, community-powered vocal party. (303) 449-3774.

LAUNCHING POINTS FOR OUTDOOR EXPLORATION

WHERE’S THE MUCK?

story and photographs by DAN LEETH

LOCATION

21 miles southwest of Grand Junction at Glade Park

TENT/RV SITES

Both

ACTIVITIES

Hiking, biking, fishing, horseback riding, stargazing, birding, wildlife viewing

Despite its grimy moniker, Mud Springs Campground offers clean, high-and-dry camping on the Western Slope

PUBLIC CAMPGROUNDS typically lure visitors with names that attractively describe their setting or proximity to some enticing topographic feature. Mud Springs Campground’s name does neither.

The ill-begotten appellation dates to when the area was grazed by sheepherders. Hooves churned the ground around a nearby spring into a quagmire of soggy muck. Today, the sheep are gone, the ground dry and the camping unsoiled. Managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Mud Springs Campground lies on the rolling, pine-dotted slopes of Piñon Mesa, about 21 scenic driving miles southwest of Grand Junction.

At 8,500 feet, its aspen-nestled sites offer summer temperatures a dozen degrees cooler than the red rock desert below.

Recently renovated, Mud Springs features 13 individual sites plus two group sites, all available on a non-reservable, first-come basis. Each offers picnic tables, fire rings, tent pads and RV-friendly driveways. Clean, pit-toilet restrooms are scattered throughout, and the campground’s communal water spigots dispense liquid tested to be as pure as the bottled stuff from the store. Best of all, mosquitoes remain scarce.

Bears, however, have been known to drop by. The onsite host tells of camping here a few years ago in his motorhome. Late one night, he heard a bear pawing at the walls of his rig. Pulling the curtain aside, he found himself staring face-toface with a bruin gazing through the window. The bear fled and, fortunately, none of its burly brethren have graced camp lately – much to the relief of those of us sleeping in tents.

The campground offers an inviting retreat for folks wanting to steep themselves in nature. Doe and their fawns browse around camp in the morning, ground squirrels scamper about all day and winged raptors frequently soar high overhead. Come nightfall, campers freed from their TV screens will discover a glittery tapestry of stars shimmering above – a sight seldom seen by city dwellers.

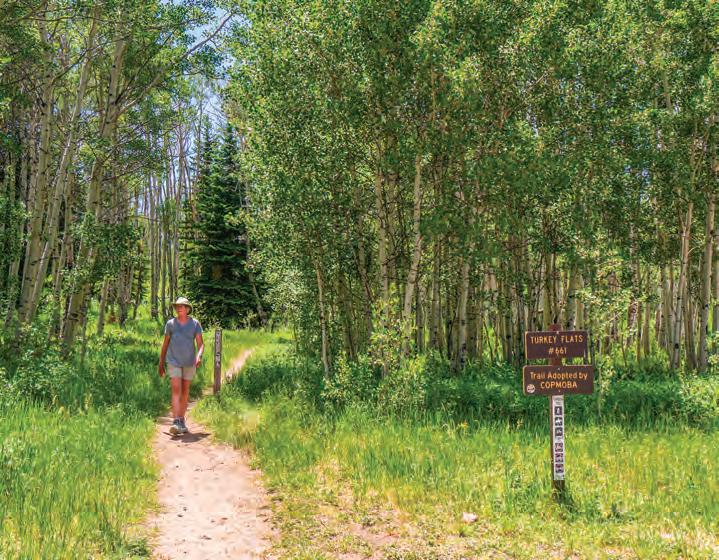

For many, just kicking back with a book provides an ideal campground pastime. Those of us craving more energetic pursuits will find several hiking and mountain-biking paths up the road. My favorite is the Turkey Flats Trail, an eight-mile loop through glades of aspen. Much shorter hikes lead to the precariously balanced Miracle Rock or down to the water-filled “potholes” at Little Dolores Falls.

Those hooked on fishing can try their luck at a series of reservoirs owned by the city of Fruita. In the early 1900s, this farming community in the Grand Valley 4,500 feet below piped its water from Piñon Mesa down the cliffs through 23 miles of wooden pipe. By the 1970s, the system could no longer keep up with demand,

and Fruita tapped new sources. Three of its former reservoirs now serve as recreational retreats stocked with fish.

Mud Springs provides a convenient base for exploring the spectacular red rock country towering nearby. Colorado National Monument offers jaw-dropping overlooks and trails, and campers with high-clearance, 4x4 vehicles can head to Rattlesnake Arches – the largest collection of natural arches this side of Moab. The final two miles of the drive require negotiating rocky, undercarriage-scraping impediments. From the trailhead, an eight-mile out-and-back hike leads past at least nine towering arches.

After any of these calorie-burning endeavors, one can stop at the Glade Park Store, seven miles north of the campground, for a bottled beverage and perhaps a pack of Oreos to enjoy on their storefront picnic tables. On Friday evenings, the Glade Park Volunteer Fire Department raises money by offering free Movies Under the Stars behind the fire station a block up the street. Fund-raising comes from viewers purchasing hot dogs, brats or burgers along with popcorn, sodas, nachos and home-baked

Cool pine forest, nearby trails, fishing and brilliant starry night skies make Mud Springs Campground a refreshing summer escape southwest of Grand Junction.

items from their grill. Movies are usually family-friendly, with seating strictly BYOC (bring your own chair).

Back in camp, conditions permitting, it’s time to build a small, marshmallow-roasting campfire and gaze at the Milky Way spilling across a black-velvet sky. It’s the same view those sheepherders saw back when the area earned its name as a quagmire of hoof-trampled muck.

Mud Springs Campground lies in the hills southwest of Grand Junction. The usual route there involves taking one of the two Glade Park turnoffs from Rim Rock Drive in Colorado National Monument (tell the entrance-station ranger you’re going to Glade Park). Flatlanders should be aware that the Monument drive involves a narrow, Coloradostyle roadway rife with twisty turns, plunging drop-offs, and seldom a guardrail to be seen. The route also includes tunnels only 16 feet tall at the centerline. From the Glade Park Store, follow 16 ½ Road south about seven miles – the final five on dusty, washboard gravel.

The campground is rustic, with no hookups, dump station or trash dumpsters. Cell coverage is marginal. Weather permitting, it’s open from mid-May through early November. Sites go for $10 per night.

TRIVIA ANSWERS

(it’s the much prettier rhodochrosite)

Trivia Photographs

Page 18, Top Bighorn sheep

Page 18, Bottom Rhodochrosite

Page 19, Colorado columbine

BAILEY’S BIGFOOT BELIEVERS

by ERIC PETERSON

A Bailey shopkeeperturned-guide leads curious hikers deep into Pike National Forest, where twisted trees, shadowed ridges and the lure of the unknown fuel the hunt for Sasquatch.

AS NIGHTFALL NEARED, a small group gathered at a trailhead in Pike National Forest about 15 miles southeast of Bailey. The new moon had blotted out the midsummer sky, and a sense of anticipation rippled through the hikers. They were hoping for a rendezvous with Sasquatch.

Bailey, at 7,700 feet in Colorado’s Front Range, is a mountain town less than an hour southwest of Denver where anglers, hikers and cabin-goers stop before venturing into the wilderness. Pike National Forest – 1.1 million acres of ridges, canyons and lodgepole pine – begins just beyond town. Leading tonight’s hike was Jim Myers, local authority on the big fella and proprietor of Bailey’s Sasquatch Outpost and Museum.

Myers said he’d seen Sasquatch in these mountains before – and wouldn’t mind another sighting that night. His research partner, Wayne Wasechka, was on hand to help guide the “Night Hike,” one of several Rabbit Hole Adventures outings including overnight and horseback trips in search of the legendary creature.

The seven hikers behind them were all self-identified Bigfoot buffs. Some had grown up watching Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of in the 1970s; others had fallen down YouTube rabbit holes.

“I need to know,” said Heidi Smith, a Denver truck driver. “A couple of things happened when I camped with my sister, but I don’t know for sure.”

Myers didn’t set out to make Bigfoot his business. In 2013, he opened the Bailey Country Store to sell groceries. A year earlier, Kate Murphy, then manager of the Bailey Lodge, had told locals about seeing a “tall,

hairy creature” bound into the woods about 200 feet ahead of her on a forest road.

At the Smiling Pig, a Bailey barbecue joint where locals swapped stories over brisket and cornbread, Myers recalled Murphy’s account. “By gum, I believed her,” he said. “I’d been interested my whole life, but I’d never actually spoken to somebody who saw one.”

That belief deepened a year later when Myers said he had his own close encounter at nearby Wellington Lake. “I was fly fishing, and it was standing above me on a big rock outcrop looking down,” he said. “A fish grabbed my fly, and like an idiot, I turned to look at the fish. Three seconds later I turned to look back at the Sasquatch, and it was gone. It had simply disappeared.”

The sighting pushed Myers to devote a small corner of his store to Sasquatch souvenirs. Sales quickly outpaced the groceries, which disappeared entirely. In their place grew a museum with exhibits on sightings, footprints and tree structures, plus an animatronic Bigfoot. The front shop sold everything from Bigfoot boxer shorts to Yeti salt-and-pepper shakers.

After amassing an impressive collection of cast footprints and plaster models, Myers started a side business, Rabbit Hole Adventures, to lead tours into the same backcountry where these stories had originated. That evening’s “Night Hike” began under a moonless sky, the ridgelines dissolving into shadow as the group headed into the forest.