SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025

Meet 300,000 of your ungulate neighbors

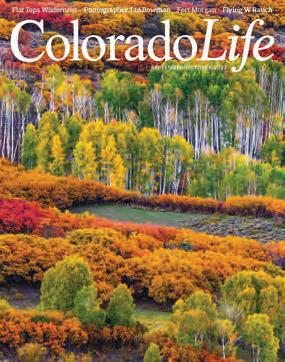

KEBLER

PASS

Autumn drive offers fall colors, photo tips

Peanut power in three hearty dishes +

Recipes

16 Gentle Giants

Luvin Arms Animal Sanctuary in rural Erie provides a forever home for former farmed animals, offering the public a unique chance to cuddle with cows, pigs, goats and more. by

Ariella Nardizzi

18 Elk-topia

Every fall, visitors flock to Rocky Mountain National Park to watch bull elk bugle, clash and corral harems – an awe-filled, unpredictable mating season in Colorado’s high country. story by Peter Moore photographs by Dawn Wilson

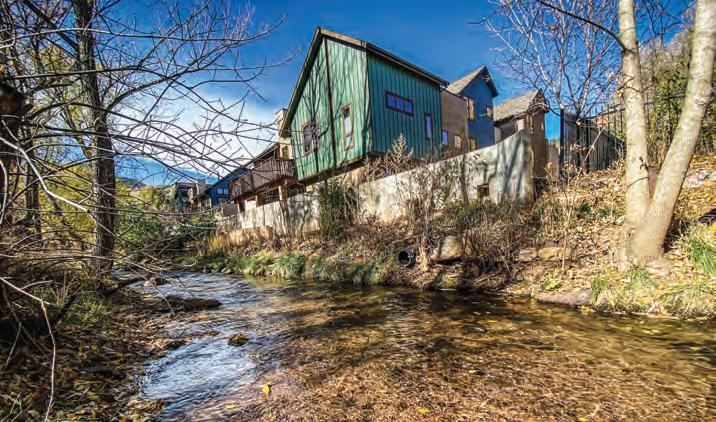

26 A River That Remembers

Fountain Creek, south of Colorado Springs, winds through Colorado’s heart, where floods reshaped towns, wildlife thrived and faded, and history resurfaced. story and photographs by Jim O’Donnell

44 Letterpress Lives Again

Mancos Common Press thrives as a creative hub in southwestern Colorado, uniting artists, history and community through the timeless craft of letterpress. by Eric Peterson

9 Editor’s Letter Chris Amundson shares stories from life in Colorado.

10 Sluice Box

A dinosaur bone newly discovered 763 feet underneath Denver; artist R. E. Reynolds paints plein air to capture nature’s wonders; Elvis Presley and Denver’s Fool’s Gold Sandwich.

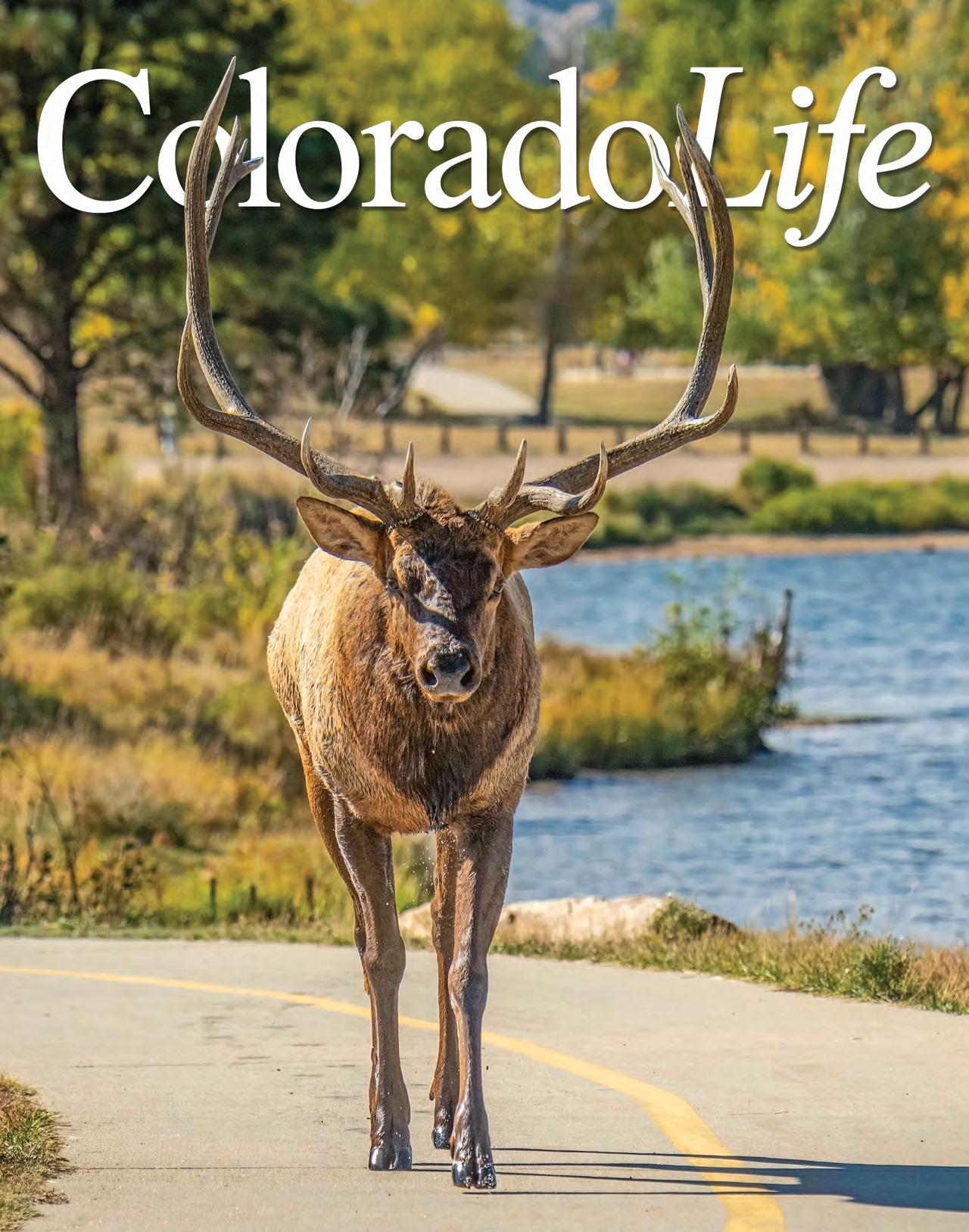

A bull elk (Cervus elaphus) struts through downtown Estes Park after emerging from Lake Estes, and they mate, or rut, in this North American hotspot. Story begins on page 18.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DAWN WILSON

Trivia

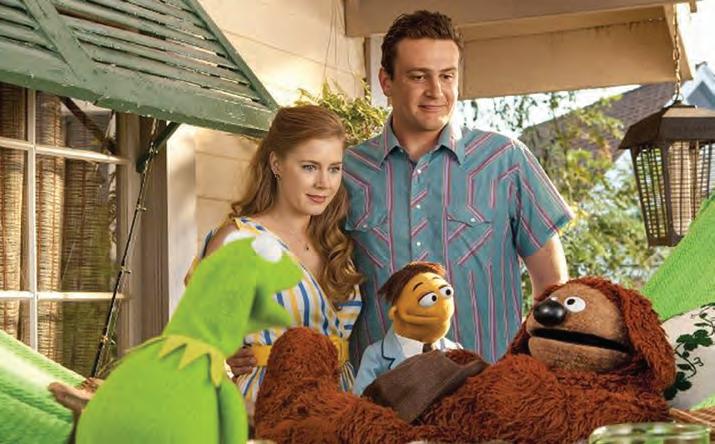

Colorado’s got star power – can you name its Hollywood headliners? Answers on page 43. 34 Kitchens

Peanuts pack a punch with three legume-inspired courses full of protein.

38 Poetry

Autumn awakens our poets’ written verses, inspired by the change of seasons, wildlife migrations and hibernations.

40 Go.See.Do.

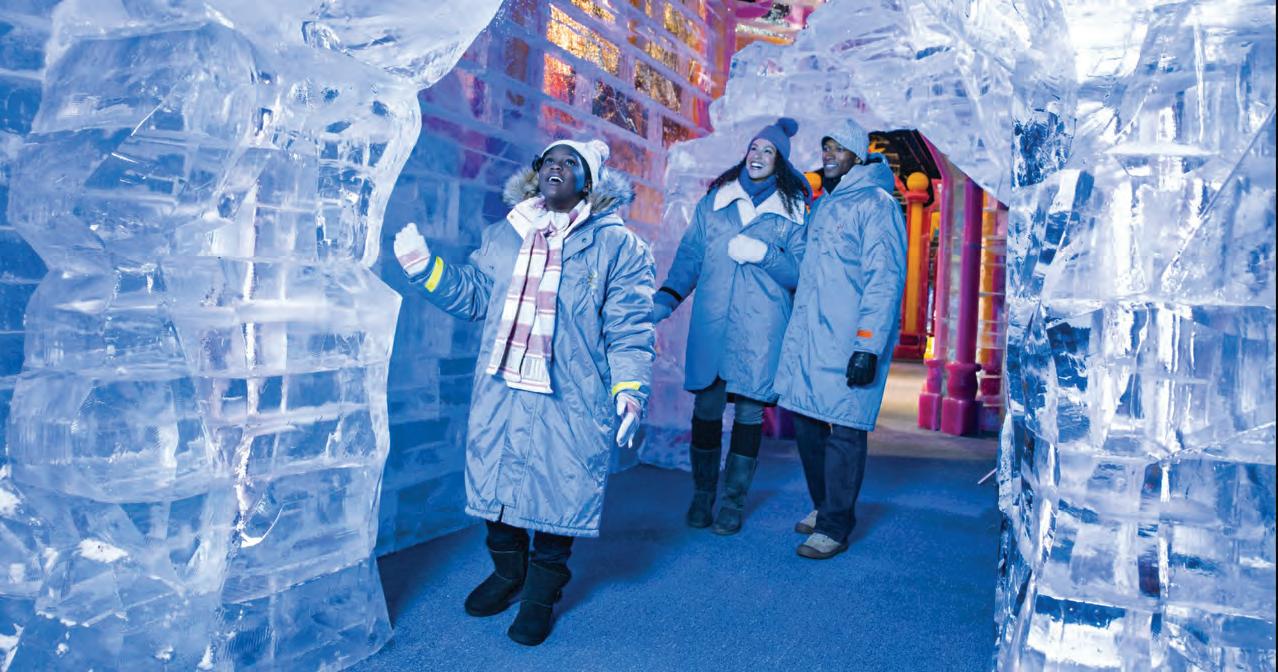

Two million pounds of ice transform “How The Grinch Stole Christmas!” into a crystalline display; Ride the rails on an authentic steam-powered train, straight to the North Pole.

46 Peak Pixels

Joshua Hardin shows Kebler Pass ablaze. Aspens glow, elk roam and Crested Butte delivered autumn’s ultimate photo op.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025

Volume 14, Number 5

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Photo Coordinator

Erik Maki

Staff Writer

Ariella Nardizzi

Design

Mark Del Rosario

Editorial Assistant Savannah Dagupion

Advertising Sales

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Sheila Camay

Social Media Manager

Lucy Walz

Colorado Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130

Fort Collins, CO 80527

970-480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com or visiting ColoradoLifeMagazine.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

VERY YEAR, THERE’S a turning point when the mountain air shifts from sun-kissed and summery to crisp with autumn tang. After the festival tents come down, the hillsides stage their own grand finale.

Aspens flicker from lime to gold, willowy brush and ferns turn copper and chestnut, and a chill rides the morning air. In Estes Park this time of year, you can’t miss the primal bugle echoing through the valleys at dusk.

For our family, the rut was more than roadside spectacle. It was daily life. We raised our three children in Estes Park, where elk often took over the yard. Suppers on the deck sometimes came with a herd grazing beneath the pines. Walks to town carried one rule: yield to elk. Some nights we drifted to sleep with their calls outside the window. Other times we sat in traffic during “elk jams,” waiting for cows and calves to cross at their own pace.

The rut is a drama as old as the mountains. Bulls strut and spar, cows mingle and tourists gather too. Each fall about 600,000 visitors come to the ungulate capital of North America, home to 300,000 elk across Colorado.

“Elk-Topia” in this issue shows both the ferocity and tenderness of the season: the clash of antlers and the quiet grazing after. Sometimes elk wander into human spaces, even holding up the McDonald’s drive-through in downtown Estes Park. In Colorado, wildlife is always the main character.

That connection runs through the rest of this issue. In Erie at Luvin Arms Animal Sanctuary, rescued cows, pigs, goats and turkeys find safety on the Front Range. Their stories in “Gentle Giants” ask us to consider compassion not as a lofty idea but as a daily practice.

In “A River to Remember,” the ghosts of the past mingle with Fountain Creek near Colorado Springs, where water carries memory, conflict and hope in equal measure. The same is true of all Colorado landscapes: they hold what came before and what will be.

Several poets echo this theme in the selections we present this season. Their lines call out the wild things we might otherwise miss: a flick of a fox’s tail or the way autumn light slants across the plains.

Few places demand a second look quite like Kebler Pass near Crested Butte, where hillsides of aspen catch golden fire. Photographer Joshua Hardin captures them in amber, ochre and aureate before the first snow folds the land into hibernation.

And so the season turns, a reminder that change is the only constant in the wild, whether you’re walking a sanctuary pasture or pausing at a mountainside of fleeting gold.

We’ll see you out there, perhaps on the trails or maybe in line at McDonald’s in downtown Estes Park, idling behind a very large, antlered local.

Chris Amundson Publisher & Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

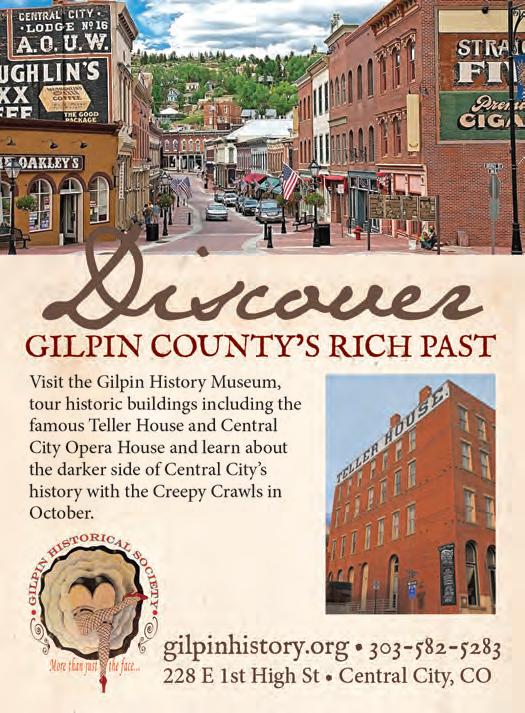

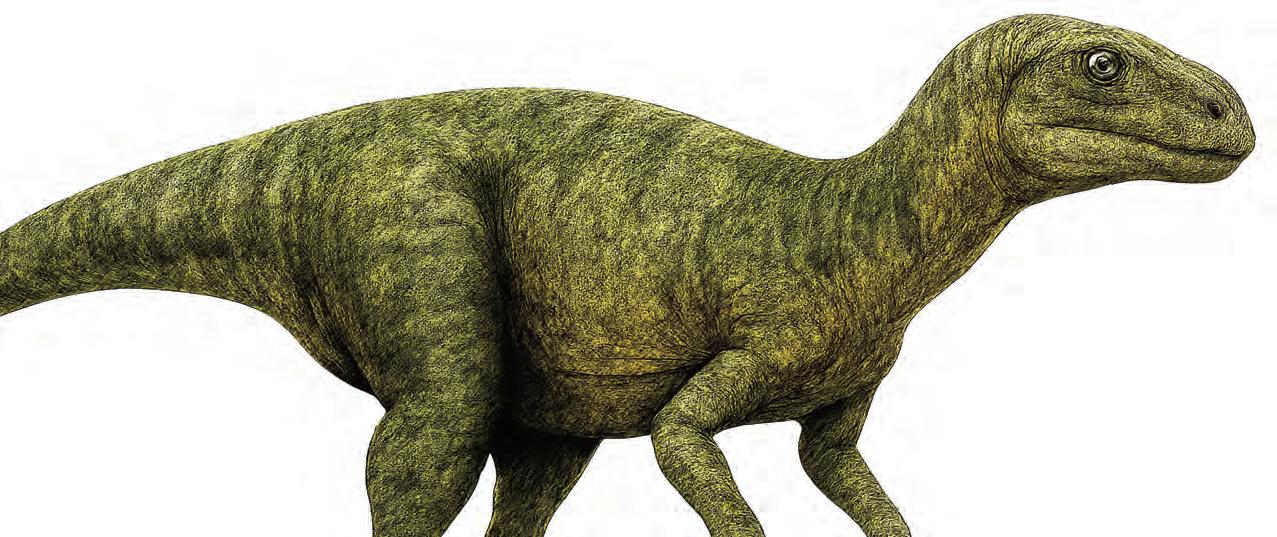

A fossilized bone found 763 feet under a City Park parking lot ties Denver’s present-day bustle to its prehistoric past.

by COLORADO LIFE STAFF

On any given Saturday, City Park hums with joggers circling Ferril Lake, families spreading blankets under cottonwoods and kids tugging parents toward the zoo. Few pause to wonder what lies far below the grass and pavement. In January, while drilling under the north parking lot of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science to test geothermal potential, a crew pulled up an extraordinary surprise: a dinosaur bone.

The fragment, a vertebra from a plant-eating ornithopod, came from 763 feet underground. In a state known for fossil-rich badlands and high-country quarries, finding a specimen in such an urban setting is remarkable. To recover bone from a core sample only inches wide borders on mirac-

ulous. One geologist likened it to sinking a hole-in-one from the moon.

Colorado has a long tradition of chance fossil finds. At Dinosaur Ridge, schoolchildren trace the footprints of giants. In Snowmass, crews building a reservoir turned up an ice-age trove. This parking lot vertebra tells a different kind of story. It shows that Denver itself is layered over ancient landscapes, its neighborhoods resting on sediments left by vanished swamps and herds.

The moment also speaks to Colorado’s identity. A project meant to test renewable energy potential became a doorway into prehistory. That collision of the future with the deep past captures the state’s balance of innovation and tradition. Here, science is always part of the landscape, whether in

wind farms on the plains or bones beneath the city.

Now the fossil is on display inside the museum. Children press their noses to the glass and picture what else might still be buried under their feet. The find invites all of us to look differently at our surroundings. Beneath sidewalks, schoolyards and city blocks, layers of rock hold stories waiting for their turn to surface.

The parking lot bone is not the most complete fossil ever found in Colorado, but it may be one of the most symbolic. It bridges the everyday and the extraordinary, reminding us that history is not only written in textbooks or displayed in galleries. Sometimes it rests beneath blacktop in the places we pass every day, waiting for a lucky strike to bring it back into the light.

In January, while testing geothermal potential beneath the Denver Museum of Nature & Science’s parking lot, crews unearthed a dinosaur vertebra from 763 feet underground. One geologist called the recovery from such a narrow core nearly miraculous, likening it to a hole-inone from the moon. Now on display, the fossil invites visitors to imagine what other stories may still lie beneath city sidewalks and streets.

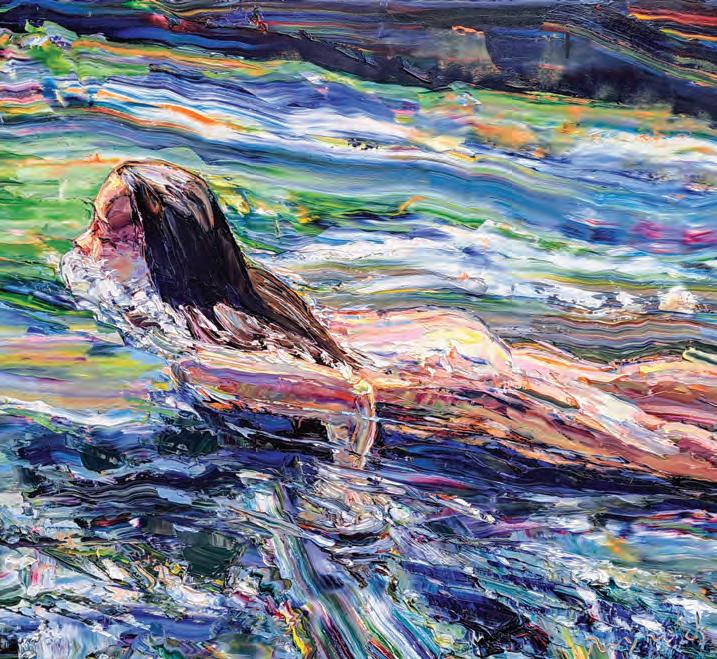

by CORINNE BROWN

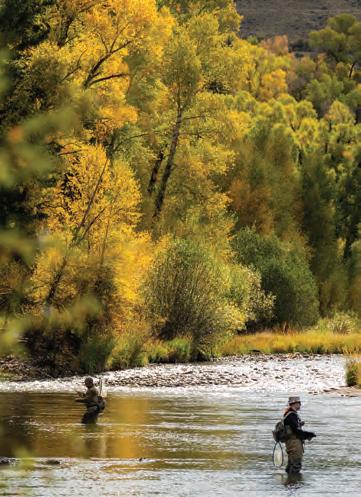

Like a Marvel-action superhero, artist R. E. (Robert Edward) Reynolds becomes a conduit for supernatural forces and high-voltage energy just by raising his palette knife. Working plein air, fast and sure, he applies oil paint to canvas and, as if by magic, lofty mountains soar, rivers flow and colors slide across his canvas depicting nature’s wonders from Colorado to New Mexico. Not just landscapes and riverscapes, his paintings are show-stopping displays of artistry tempered by a lifelong love of the outdoors.

Born in Golden, Colorado, Reynolds credits his father who was an engineer at the Coors brewery for a life-long love of art. He was a talented watercolorist who encouraged his young son to paint. As a child, Robert loved nature even then, espe-

cially a series of nearby ponds that formed in the midst of a local gravel pit where all manner of aquatic life emerged, enticing a child to its banks nearly year-round to seek frogs and turtles – whatever nature had in store. That love of the outdoors and water became a lifelong definition of personal comfort, drawing Reynolds to explore Colorado’s Front Range, her wilderness areas, and her mighty rivers, especially the Colorado, and later, in New Mexico, the Chama and the Rio Grande.

“The way I paint,” said Reynolds, “is the way nature feels to me; free flowing, everchanging. I hope to participate– even get lost – in my creation. Something deeper behind what I see, a feeling of connection, drives the inspiration.”

That feeling can be felt by the viewer at first glance with works that simply command attention. The artist confirms, “The

beauty I’m looking for is raw; unfinished and organic, like nature herself. I want the viewer to feel as if they are standing right there to feel the space, the sunlight, the wind and, at the same time, follow the dance-like process by which paint was laid down.”

At home today in New Mexico, Reynolds reminisces further about a moment in his youth when his father encouraged him to look up and appreciate the rising cumulus clouds and luminous late afternoon light. “I want you to remember this day,” he said, “and keep it forever.”

“That special vision” said the artist, “and others like it, have been humbling, evoking feelings of awe about the world around me.”

Fortunately, for the rest of us, through Robert Reynold’s art, we can share those visions too.

by ALAN J. BARTELS

Elvis Presley’s fondness for peanut butter and banana sandwiches was well known. So was his penchant for gold jewelry. When the King arrived at the back door of the Colorado Mine Company restaurant in Denver in 1976, 16-year-old cook Nick Andurlakis didn’t get all shook up.

Nobody would have blamed Andurlakis for being just a bit nervous. Presley, after all, arrived after midnight with a contingent of Denver cops, and was, himself, dressed as a police captain. He was even wearing a shiny badge. Presley befriended the officers after the Denver PD provided security for one of his concerts. He generously helped fund a police gymnasium, and showered his law enforcement friends with guns, cars and gold necklaces.

When Presley asked for a recommendation to cure his late-night munchies, Andurlakis brought him the Colorado Mine Company’s Fool’s Gold Sandwich. Topped with four pounds of peanut butter, blueberry jam and bacon, the behemoth was a big hunk o’ love with the hit maker. He ate two.

A few months later, Presley called in his order from Graceland in Tennessee before flying to Stapleton. The flight was part of an elaborate in-air birthday party for Presley’s daughter, Lisa Marie. Andurlakis arrived with the sandwiches, prime rib and a birthday cake for Presley’s princess. The King gave him a gold crucifix necklace. Andurlakis still wears it today.

Presley died in 1977. Andurlakis opened Nick’s Cafe in Lakewood after the Colorado

Honorary Denver policeman Elvis Presley was a fan of the Colorado Mine Company restaurant’s Fool’s Gold Sandwich. Nick Andurlakis first served one to the King in 1976. Today, he offers the sandwich at his Nick’s Cafe in Lakewood.

Mine Company restaurant closed in 1982. Elvis albums, posters, photographs and signs adorn the small diner from floor to ceiling. A photo of Presley in his police uniform hangs next to a guitar. The Fool’s Gold Sandwich is on the menu.

“Nick jokes that the sandwich serves six regular people or one Elvis,” said longtime Denver Elvis Presley impersonator Jonny Barber. “The first time I had one, there was so much sticky goodness that I had to postpone a show to let my vocal cords get unstuck. If you plan to order this big and messy sandwich, don’t wear your good blue suede shoes.”

e grandeur of a bygone era awaits you at Rosemount in Pueblo! Built in 1893, this 37-room, 24,000 square-foot mansion was the family home of prominent businessman John A. atcher and his family. Take a guided tour of the mansion, and step back in time.

Open February -December

Tuesday-Saturday • 10 am–2:30 pm

Challenge your brain with our Colorado quiz. by

MATT MASICH

1

What actress, who grew up in Castle Rock before starring in Enchanted and American Hustle, has inexplicably never won an Oscar despite six nominations?

2

A graduate of Denver’s East High School, Don Cheadle got an Oscar nod for Hotel Rwanda and joined George Clooney’s gang in what heist film and its sequels?

What other East High grad Coffy and in the 1970s and in Jackie

Raised in Boulder, Sheryl Lee played the ill-fated Laura Palmer in a film and TV show named for what fictional Pacific Northwest town?

Though he dropped out after his freshman year, what ghost-busting comedian got an honorary doctorate from Denver’s Regis University in 2007?

6

What star of The Sting and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid worked at Boulder bar The Sink while attending the University of Colorado?

a. Paul Newman

b. Robert Redford

c. Sam Elliott

7 She was called Cassandra Peterson growing up in Colorado Springs, but horror fans know her better as what “mistress of the dark”?

a. Elvira

b. Morticia

c. Vampira

8

What Denver native got his acting break as a TV tool enthusiast before playing a lead role in Toy Story and The Santa Clause?

a. John Ratzenberger

b. Tim Allen

c. Tom Hanks

9

The voice of Trixie in the latest Toy Story sequel, Longmontborn Kristen Schaal also voices bunny-hatted Louise Belcher in what animated TV series?

a. Bob’s Burgers

b. Family Guy

c. The Simpsons

10

Known as “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” what Colorado Springs native played the grotesque leads in The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame?

a. Bela Lugosi

b. Boris Karloff

c. Lon Chaney

11 Fort Collins’ Jake Lloyd never appeared in another film after playing young Anakin Skywalker in the first Star Wars prequel.

12

As students at CU-Boulder, South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone teamed up to create Cannibal! The Musical, a movie based on the life of Alfred Packer.

13

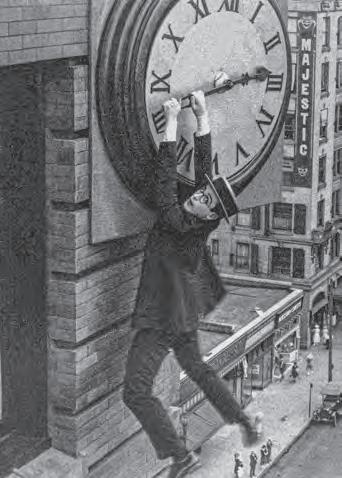

Clock-hanging silent film star Harold Lloyd was born and raised in Denver.

14 In 1951, Grace Kelly was acting in a play at Denver’s Elitch Gardens when she got a telegram saying she’d been cast in High Noon, her first major film role.

15

Gone with the Wind’s Hattie McDaniel, who grew up in Fort Collins and Denver, was the first African-American performer to win an Oscar.

No peeking, answers on page 43.

Colorado Life Magazine celebrates the people, places, history, food and culture that make Colorado unique. Gifting to your circle of friends and family spreads the love of this great place. It’s

At Luvin Arms Animal Sanctuary, every resident has a name – and a story to tell.

BY ARIELLA NARDIZZI

ON A WARM autumn morning in Erie, a potbelly pig named Mississippi shuffles through straw with cantankerous confidence. She’s the undisputed matriarch of the pig pen – though if you scratch her belly, her ornery facade melts away. Within seconds, she flops onto her side, powerless against her favorite indulgence.

A few barns over, Maui – the smallest of the big pigs – pricks his ears at the sound of approaching footsteps. He knows the rhythm of his favorite caretaker’s shoes, leaping from a dead sleep into a sprint across the barnyard for a kiss or a snack.

At Luvin Arms Animal Sanctuary, every resident has a story like this. Founded in 2015 by Shaleen and Shilpi Shah, the nonprofit has grown from a single rescue horse, Jale (short for Jalapeño and pronounced

Holly), to a family of 153 residents. Over the last decade, the sanctuary has rescued more than 800 farmed animals from neglect, abuse and difficult beginnings, and given them a permanent home.

The Shahs, originally from India, built the sanctuary on the principles of ahimsa (nonviolence), karuna (compassion) and jivdaya (respect for all beings). Their goal isn’t to shame or divide, but to create understanding. “We balance advocating for farm animals without judging people for their everyday decisions,” said Executive Director Kelly Nix. “Our responsibility is to show the sentience, personality and individuality of each resident.”

Nix first came to the sanctuary as a guest in 2020. After 14 years in public education, she joined Luvin Arms as Education and

Outreach Coordinator in 2022 and later became its director. She knows nearly every resident by name, greeting each like family –much as she does with the sanctuary’s staff. Nix is especially bonded with Gilmour, a gentle giant of a pig whose likeness she carries as a tattoo. Each day, she makes time to simply walk among the animals, reinforcing the relationships that fuel her work. “My goal is to get every person who visits the sanctuary to walk away connected with at least one animal,” she said. That mission comes alive in experiences designed to connect people with animals in unexpected ways. Take the Cow Cuddle Experience, where visitors lean into the gentle warmth of a resting cow. With slower heartbeats and a body temperature slightly higher than humans, cows can ease stress,

calm the nervous system and even trigger oxytocin – the “cuddle hormone.”

Last year, more than 33,000 people visited the sanctuary for tours, school field trips and specialty programs such as Cocoa and Cuddles, where plant-based hot chocolate accompanies introductions to barn residents. Each experience is family-friendly and educational, and Erie provides a rural backdrop within easy reach of Colorado’s Front Range.

Education extends through partnerships with Colorado universities. Students from the University of Denver’s animal law program and Colorado State University’s veterinary program gain hands-on experience caring for older farm animals – something rarely encountered in traditional livestock settings. The relationship is mutually beneficial: students learn advanced care techniques while animals receive top-notch attention. Several CSU interns have stayed on as full-time staff.

But some lessons can’t be taught in a classroom. Tito, the sanctuary’s ambassador, arrived as a 10-day-old calf and now greets visitors with calm presence. Barnaby, an Angus cow, was once discovered standing beside a family Christmas tree after teaching himself to open a sliding glass door. Today, he lumbers around the pasture like a playful, oversized puppy.

In Big Barn, former dairy goat Dezi learned to ride a skateboard. Garbanzo, a Nigerian Dwarf goat, shows off his skills as an up-and-coming soccer star.

Sometimes it’s the animals themselves who show the greatest compassion. Caretakers once watched Lizzie the pig tuck straw and drape a blanket over her sick sister Lily – a small act of kindness that they never forgot.

Those moments, said Nix, define the sanctuary. “It shifts people’s perspectives from animal to individual,” she said. “That’s how change happens. Not through judgment, but through connection.”

After 10 years, Luvin Arms has become more than a refuge. It’s a place where animals are seen, not as a herd, but as individuals with names, quirks and stories worth sharing.

MEET YOUR UNGULATE NEIGHBORS – ALL 300,000 OF THEM. BUT DON’T GET TOO CLOSE, YOU HEAR?

IAbout 300,000 elk roam the wilds of Colorado, migrating from the high country to lowlands every October. During mating season, they can often be found coexisting in human-populated spaces, like crossing a deserted Colorado Highway 7.

T WAS A SCENE out of “Real Housewives of Estes Park.” Coquettish females frisked around dominant males while rivals lurked in the bushes. Literally in the bushes – because these reality stars were elk, and the soap opera was playing out in real time in Rocky Mountain National Park, ground zero for the late-September elk rut.

Colorado is home to about 300,000 elk, making it the ungulate hotspot of the American West. They range from Roosevelt National Forest in the north to the plains above Craig to the habitat surrounding Montrose. In short, if you’re in the mountains, elk are your neighbors –browsing shrubbery, nibbling high prairies and, most ominously, crossing the roads in front of your car.

Nathaniel Rayl, a wildlife researcher for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, extols the state’s elk welcome mat: “We have good habitat, a great history of wildlife management, a lot of aspen stands, a productive understory fed by monsoonal rains, and

nutritious forage in subalpine meadows.”

Our elk numbers are a reintroduction success story. In the early 1900s, North America’s elk population had fallen to just 40,000. Colorado wildlife officials imported 50 animals from Wyoming and began managing them. It worked. Now, when surging hormones summon elk into Moraine Park – a broad meadow near Estes Park, the gateway town to Rocky Mountain National Park – the resupply is on. I too have been lured there by the bull’s eerie bugling – like somebody strangling the world’s largest kazoo.

That honking wail, combined with spreading antlers and hard body, is irresistible to cow elk. According to Jack Ballard’s Large Mammals of the Rocky Mountains, a bull can top 1,100 pounds, with antlers stretching five feet and weighing 40 pounds. Keep that in mind when you spot one grazing nearby: an elk can run 45 mph and cover 14 feet in a stride, going from mild to murderous in the blink of a camera shutter.

Each autumn, 600,000 visitors flock to Rocky Mountain National Park to witness the elk rut. Above, a lone bull elk (Cervus elaphus) stands in front of the drive-through line at McDonalds in downtown Estes Park as onlookers snap a photo.

I GAVE THE BEASTS plenty of room one radiant afternoon last fall in Rocky Mountain National Park. Not so for other visitors, who seemed to think they were watching a live-action Bambi instead of Darwin in action. About 600,000 people flock to the park in September, drawn by elk romance and yellowing aspen. Park officials advised staying at least 75 feet from elk – about two bus lengths – to avoid being charged.

I set up a folding chair beside a field dotted with bulls and cows and watched males corral harems – anywhere from a half-dozen to 40 females. Given the sexy shenanigans in Moraine Park, I was glad to have only one wife.

As I watched, a dominant bull sprinted around, herding cows into his cohort. Meanwhile, a rival lounged in the grass,

chewing cud. Snooze/lose, pal. But when the big bull chased a wandering female, the chill bull leapt to his feet. A nearby cow made doe eyes, and in a flash they were making elk babies. Sometimes a zen approach leads to fatherhood, too.

Elk concentrate in the high country during mating season but disperse once October arrives. By then they’ve built fat stores for winter and the eight-and-a-halfmonth gestation. While blizzards lash Trail Ridge Road, you’ll see them lounging in lowlands. I’ve seen elk browsing through suburbia like lawn ornaments. Once I spotted two bulls battling on top of a mulch pile. By spring, cow elk retreat to secluded meadows to calve, hiding their spotted newborns in tall grass until they’re strong enough to travel with the herd.

Ray Aberle, who manages elk-human

interaction for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said bulls had even been seen in barley fields near the Buc-ee’s travel center off I-25 in Johnstown, north of Denver. Clearly, beavers and elk can coexist. And Colorado’s absence of apex predators like grizzlies gives elk free rein. Wolves, reintroduced to the state in 2023, might eventually shift that balance, though their impact on herds is still emerging.

So humans are the biggest risk. There are about 14,000 car-animal collisions in Colorado each year, and elk are large targets. After a fall backpacking trip, a friend and I were driving home past a big elk field in Evergreen. One bull decided the grass was greener on the other side of I-70. It leapt over the hood of our truck, freezeframed in the headlights. Had we left camp a second earlier, the elk might have

come through my window, and someone else would be writing this story.

eryone in Estes Park. In 2023, another was spotted in The Beef Jerky Experience.

Tourists and local business owners have reported elk sightings in strange locations all over town. A cow elk sniffs a metal dinosaur sculpture on a rainy day in Estes Park. Elk have also been found roaming stores like Gifts for Everyone and The Beef Jerky Experience.

Another risk comes when elk wander onto private land, competing with cattle for forage. Aberle helped ranchers coexist with migratory herds. “It’s a habitat partnership,” he said. “We helped with fencing, develop water sources and treat noxious weeds. It’s good for elk and livestock, too.”

Ranchers can also host hunts, which manage the population. “Hunting can be a source of revenue and pride,” Aberle said.

And dinner. I once capped a day in Moraine Park with an elk burger in Estes Park – low fat, high adventure, on a bun.

Elk also show a flair for tourism – and shopping. A video surfaced of a cow browsing inside a store called Gifts for Ev-

I asked Aberle what would lead an elk into a shop, especially one selling elk jerky.

“I’m not sure exactly what was going on with these elk,” he said. “They didn’t appear sick or agitated. My best guess was some combination of curiosity, habituation to humans and maybe a search for food. Elk are exploratory by nature, and bold individuals will check out novel environments, including stores. Once inside, it might have been hard to figure out how to exit.”

A store employee solved the problem by threatening the cow with a stuffed bear. Don’t try that in Moraine Park this fall –or you may become an elk-antler hood ornament.

A bull elk wades into the waters of Lake Estes with the iconic Stanley Hotel perched in the background. A herd of cows and calves jumps a barbed wire fence as they migrate across the valley in Estes Park each fall.

Fountain Creek carries the weight of floods, ghosts and change through the heart of Colorado.

THREE GEESE SKIMMED the creek then veered toward a mass of cattails. A coyote slipped into tamarisk, reappeared upstream, then vanished. Deer prints tracked smears of snow edging the ice. I reached the bridge just after dawn. Along the creek, the forest was faded yellows and shades of gray.

The path runs for miles beside Fountain Creek, just south of Colorado Springs. The sky, a cold blue, pressed against the mountains where clouds crowded the peaks and ridges. A nuthatch called – a nasally wahwah-wah. I stopped, but couldn’t locate the bird. For several hours I moved north through the creekside forest.

The Fountain trickles from snowpack on 14,115-foot Pikes Peak. The Tabeguache Ute – Nuuchiu in their own language – know the peak as Tavá Kaa-vi, “Sun Mountain,” and its waters flow 74.5 miles to the Arkansas River in my hometown of Pueblo.

We call the Fountain a “creek” because once it was: a thirsty, ephemeral tributary prone to dramatic floods. Today, it runs full and swift year-round – a “new” river.

Over the years, the Fountain has been dammed, diverted, poisoned, rerouted, channelized, filled with debris, blamed and litigated. Humans have altered its very nature, pumping water from Colorado’s Western Slope into the watershed.

The creek will win. It always has. Water always wins.

FOUNTAIN CREEK IS among the most human-dominated waterways in the American West – and that’s saying something.

One stretch once held a beaver dam that backed up water into a deep pond winding through elms, willows and cottonwoods. Snowy egrets fished there, teals and wood ducks dabbled. I counted sora. Once, even, a white ibis.

One summer afternoon I sat at the pond’s edge, breathing its rich, wet scents. Duckweed blanketed the water, turning the forest a glowing green. The beaver surfaced, her head crowned in duckweed. Another day, midwinter, she pushed through ice, eyes

and nose just above the surface before slipping away.

That day, though, the dam was gone. The pond drained. The beaver vanished. Someone had dismantled the dam, drained the pond and likely killed or chased off its builder.

There was no reason I could see. The dam hadn’t threatened road, trail, farm or building. It had filtered sediments, replenished the aquifer and hosted a wetland.

If there’s a word for a natural place harmed by people, I haven’t found it. “Desecration” comes close but doesn’t fit. Lacking such a word suggests we’ve accepted these losses as normal.

From Pikes Peak through Manitou Springs to Pueblo, Fountain Creek reflects survival and change, where human impact meets nature’s persistence. Autumn colors frame its upper watershed near Catamount Reservoir.

Beyond its own story, Fountain Creek carries those of others around it. Pikes Peak, sacred to the Tabeguache Ute as Tavá Kaa-vi or “Sun Mountain,” watches over the river’s headwaters. A teepee stands at Catamount Institute near the upper reaches of the creek’s watershed. Animal tracks mark sands north of Pueblo, and an angler fly fishes for trout in Manitou Springs.

I DROPPED TO the ground, poured coffee with a splash of whiskey, and watched snow tumble to the water. Behind me, I-25 roared while a transport plane circled. A drone, a helicopter, then sirens followed. I try not to collapse into anger at the endless wounds to land and water.

Still, I tore off gloves, rolled up sleeves and rebuilt the dam. Water filled my boots. I jammed sticks into the brook, wove willows through, and packed mud.

I knew it was a useless gesture – an act to soothe myself, as if action might matter.

The creek will win. It always has. Water always wins.

In middle school, I biked with my friend Scott Grant to hunt arrowheads in the dry creekbed. In high school, another friend

and I fished from a bridge at the confluence, sipping cans of Coors from his father’s cooler. We hunted pheasant and quail in the bottomlands. In winter we dug icy sediments for Pleistocene fossils.

Scott is dead – a bullet at a party. Atencio died in his 40s of a heart attack. For me, the Fountain carries ghosts.

The creek’s alluvial sands glow pink, red and orange. They hold tracks of heron, geese, ducks, fox, coyote, skunk, porcupine, deer, even elk, bear and mountain lion. Nearly a million people live within the watershed.

When the creek rises, it wipes the prints away. When it drops, tracks reappear within hours. Each step adds to that fleeting tapestry.

A tributary to Fountain Creek, Bear Creek watershed feeds the main river, a quiet reminder that water always wins. Phragmites, an invasive grass, line the banks in Pueblo, helping slow erosion despite their non-native origins.

IN JUNE 1965 , heavy rains saturated the soil. At midnight on June 17, reporter James Osnowitz left the Pueblo Chieftain to watch the creek rise. He never returned. The Fountain spilled its banks. In Pueblo, 53 blocks went underwater. Twenty-four people died. Five thousand homes washed away.

More than once, the creek has taken lives – and returned them. In 1998, children playing in a dry bed found the skeleton of Ronnie White, missing 32 years. His mother had searched strangers’ faces ever since.

The Fountain holds many ghosts.

I tell myself this story is how we’ve learned everything about a creek – and so little about ourselves. It bears witness,

grieves, gives thanks and uncovers something essential about this moment, about us, about the Fountain and the future of water in the West.

I finished the whiskey, shouldered my pack and climbed the embankment. A great V of geese pushed up the Fountain into the storm.

About the Author: Jim O’Donnell is an author, conservationist and journalist based in Taos, New Mexico. His work explores the intersections of ecology, memory, place and resilience. This story is adapted exclusively from his book Fountain Creek: Big Lessons from a Little River (Torrey House Press, 2024)

Running through Colorado City, the Fountain remains a critical wildlife corridor in a very urbanized environment. It continues to uncover essential truths about its history, the rhythm of life along its banks and the future of water in the West.

recipes and photographs by AMBER PANKONIN

AS FOOTBALL FANS prepare their tailgating coolers, peanuts are an easy and delicious grab-and-go snack. But with a little extra prep, this lip-smacking legume (not a nut but it sure works as one!) packs a mighty protein punch and an incomparable crunch to vegetarian burgers, chicken tenders and power bowls. These recipes by registered dietitian and personal chef Amber Pankonin pave the path for peanut perfection.

Dinner comes together in a snap – and everyone makes their own customized bowl to taste – in this nutrient-dense and flavor-packed meal. The lime, garlic, peanut dressing makes for a lovely creamy mouthfeel that complements the snap of the vegetables, the softness of the grain and the richness of the meat.

For each bowl, build base with 1/4 cup whole grains. Add 4 oz lean protein source, which can include lean beef, chicken, pork, eggs or beans. Add preferred veggies. Dress with spicy peanut dressing. Top with peanuts.

Bowl

1 cup quinoa or brown rice

1 lb lean protein source (beef, chicken, pork, eggs or beans)

Different types of vegetables, chopped

Crushed peanuts for topping

Dressing

1/4 cup +1 Tbsp water

1/2 cup peanut powder

2 tsp low sodium soy sauce

1 Tbsp lime juice

1 Tbsp brown sugar

1 tsp finely minced garlic cloves

Ser ves 4

Parents know that chicken tenders appease even the pickiest kids. But sometimes your average chicken tender can be a little boring for adults. This recipe takes tenders from workable to wow. A crunchy peanut crust adds a satisfying bite, especially when dipped in a honey mustard sauce. Move over, junior. Mommy wants another one.

Lightly season both sides of chicken tenders with kosher salt, pepper and small amount of cayenne pepper.

Combine 3/4 cup flour with 2 tsp kosher salt and 1/4 tsp pepper. Set aside. Combine 1 cup crushed peanuts with 1/2 cup bread crumbs. Set aside. Combine eggs and milk. Set aside.

Set up breading station using seasoned flour, eggs and peanut mixture. Dredge each chicken tender in flour, then dip in egg mixture. Coat with peanut mixture. Place on aluminum-lined baking sheet and bake for 15-20 minutes at 400° until golden brown or the internal temperature reaches 165°.

Once fully cooked, remove from baking sheet and sprinkle with chopped parsley. Serve with lemon wedges and honey mustard sauce.

Chicken

1 ¼ lbs chicken breast tenders Kosher salt Pepper Cayenne pepper

3/4 cup flour

2 tsp kosher salt

1/4 tsp pepper

2 large eggs, beaten

2 Tbsp milk

1 cup lightly salted roasted peanuts, crushed

1/2 cup bread crumbs

2 Tbsp fresh parsley, chopped

Dressing

2 Tbsp honey

2 Tbsp dijon mustard

2 Tbsp mayonnaise

Ser ves 4

For a fun dinner switcheroo, here’s a peanut burger mixed from superfood quinoa and garbanzo beans and dressed with a zingy raspberry coulis – a thin fruit puree. Beef lovers needn’t fret – this is just a burger variation, like using chicken or pork, and not a permanent replacement. It’s great on a bun or on top of a salad.

For burger: Cook quinoa as directed. Sauté onion and garlic until onions are caramelized. In food processor, add peanuts and beans. Process into smaller pieces. Add other ingredients (except coulis ingredients) and blend until ingredients hold together. Split burger mix into four sections and pat into four large burgers. Heat skillet medium low with small amount of oil in pan. Cook patties 7-10 minutes each side until golden brown. Serve with raspberry coulis, onions, tomato slices and lettuce.

For coulis: Heat raspberries, water, powdered sugar in small sauce pan. Berries should pop and reduce. For thicker sauce, mix in cornstarch slurry and boil for three minutes. Strain and set aside to top burgers.

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Peanut burger

1 cup peanuts

1 cup garbanzo beans

1/4 cup quinoa

3/4 cup water

1 Tbsp peanut butter powder

2 Tbsp basil, dried

2 Tbsp Worcestershire sauce

2 Tbsp soy sauce

1 Tbsp garlic, minced

1 medium onion, diced

1/2 tsp kosher salt

1 tsp black pepper

2 Tbsp flour

Raspberry coulis

6 oz raspberries

2 Tbsp water

1 Tbsp powdered sugar

Cornstarch slurr y, optional

Ser ves 4

As autumn settles across Colorado, wildlife stirs with its own rhythms – elk challenging rivals, bears preparing for the long winter, birds carving their passage through thinning skies. In these moments, we glimpse the enduring bond between season and creature. Our poets invite us to see this turning of the year through the eyes of the wild.

Janice Schefcik, Centennial

Dense forest cradles the newborn fawn

Curled tightly, sleeping in silent wait.

Milky spots scattered on the reddish coat

Blend perfectly with the dappled sun rays

Slanting through the pines

Protecting this perfect miracle.

Robert Basinger, Rifle

Lives in a burrow

At the base of a pine tree

Next to a picnic table In a state park.

When he gets hungry

He just strikes a pose With big innocent eyes And a furry nose.

His claws are sharp

His coat is slick

He’s grown quite plump Knows all the tricks.

And I really don’t mind

Where all the food went I just don’t want to find him In my tent.

Kira Córdova, Littleton

Blue copper rockhopper messenger of spring

Cool water air hotter summer blistering

Growing trees shadows squeeze water flows below

Blue coppers do not falter ride the undertow

Jeffery Moser, Aurora

Little lark bunting Colorado’s Troubadour “Warble! Warble! Pipe!”

Suzanne Lee, Littleton

In the grey light before autumn dawn, I awaken to a raucous, insistent medley of hoots, bellows, and trumpets below my second story window.

J. Craig Hill, Grand Junction

A robust elk with a forest of antlers repeatedly challenges his reflection mirrored in the windows of the floor below, stands belligerent, stiff-legged. He feints a charge, infuriated by the aloofness of this silent rival who mimics his every move.

His perseverance, his intractable wrath, remind me that my greatest battles are with myself. These would be famous bouts if ever we engaged. We are so well matched.

Charles Ray, Evergreen

large black bear squeezes his wiggling butt under the roadside guardrail

The house finch bobs along an oscillating sine wave

The dark-eyed junco gets a running start

The hummingbird flies a thousand miles to hover drone-like at my feeder

The startled mourning dove blasts off and glides away to safety

The quail pops up from out of nowhere to trot around the deck and drop back into nowhere

The golden eagle spirals up a winding thermal staircase

Two crows dance a classic pas de deux on the gentle morning breeze

The chipmunk comes at noon to steal a little bird seed

The raccoon comes at night to steal a whole lot more

Send Your Poems on the theme “Stillness” for the January/ February 2026 issue, deadline Nov. 1 and “First Thunder” for the March/April 2026 issue, deadline Jan. 1. Email your poems to poetry@coloradolifemagazine.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

NOV. 24-JAN. 2 • AURORA

Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas! comes to life this holiday season at Gaylord Rockies Resort in a dazzling display carved from more than 2 million pounds of ice. The magic begins long before opening day. Over 40 skilled artisans travel 6,000 miles from Harbin, China – known as the “Ice City” – to spend six weeks chiseling, sawing and grinding away at 6,700 blocks of ice, stacked higher than 17 Empire State buildings.

Following a 300-page blueprint, the artists handcraft 10 whimsical scenes across 17,000 square feet. Inside, the temperature stays at a frosty nine degrees, so guests zip into provided blue parkas before stepping into this crystalline storybook. Begin in Whoville, where the Grinch scowls from

14 feet above his mountaintop lair. Wind through to “The Grinch’s Wonderful Awful Idea,” with its three-foot-tall Grinch head, then slip down two-story ice slides as Max guides the sleigh over Mount Crumpit. The finale bursts with color – a festive Christmas feast where even the iciest hearts may grow three sizes.

Kids love “Elf Training Academy,” plus overnight guest perks like the Chill Pass for front-of-line access. New this year: snow tubing through indoor Candy Cane Mountain and Feast with the Grinch.

Weekends are busiest, so plan a midweek visit, dress in layers under your parka and bring gloves for sliding and snapping photos. christmasatgaylordrockies.com. (720) 452-6900.

WHERE TO EAT THE COMMON GOOD

Farm-sourced fare in a bright, naturally lit space. Try banana walnut crunch pancakes for breakfast or a cheeseboard at dinner. 13025 E. Montview Blvd. (720) 760-5760.

WHERE TO GO STANLEY MARKETPLACE

A warehouse turned community hub with food vendors, roller-skating, art and shops. 2501 Dallas St. (720) 990-6743.

WHERE TO STAY GAYLORD ROCKIES RESORT & CONVENTION CENTER

Luxury rooms and suites with alpine views from the Grand Lodge Lawn. 6700 N. Gaylord Rockies Blvd. (720) 452-6900.

Artisans whittle, chisel and saw 2 million pounds of ice into a grand storybook scene out of the holiday classic, “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!”

NOV. 21-JAN. 3 • DURANGO

Each winter, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad – once the lifeline of the Old West – carries pajama-clad believers on nightly runs to the “North Pole.”

From the magical moment you step into the vintage depot on Main Avenue, you’re swept into Chris Van Allsburg’s classic The Polar Express TM Chefs in white coats serve steaming hot chocolate and cookies while a narrator brings the story alive. A chorus of jingling bells hints that something magical lies ahead.

Outside, the rugged landscape flashes by in snowdrifts and shadow on this 65-minute ride. It’s the same rugged canyon country miners and cowboys traveled in the 1880s. Today, this National Historic Landmark remains one of the few steam-pow-

ered trains still running its original, historic route from its establishment.

At the “North Pole,” a blaze of lights set to holiday music greets passengers young and old. On the return trip, Santa makes his rounds, handing out silver sleigh bells – the first gift of Christmas.

For 2025, trains depart Nov. 21-Jan. 3 with up to three evening departures. Choose from Standard Class with padded seats, Deluxe Class with souvenir mugs and totes or Premium First Class with table seating in decorated historic cars. Heated coaches keep riders cozy, but layers and boots help with outdoor waiting and light displays. Plan about two hours for the full experience. durangotrain.com. (970) 247-2733.

WHERE TO EAT MICHEL’S CORNER CREPES

Chef Michel Poumay dishes sweet and savory crepes downtown, from lemon cream to merguez with green chile. 598 Main Ave., (970) 769-0256.

A 1904 schoolhouse turned museum with a restored classroom, Wild West law-and-order exhibits and wildfire displays. 3065 W. 2nd Ave., (970) 259-2402.

More than 40 mineral-fed features, from hot springs and cold plunges to Japanese-inspired soaking tubs. 6475 County Road 203, (970) 247-0111.

Victorian Horrors + Séance Party

Nov. 1 • Denver

The Molly Brown House Museum hosts a séance with ghostly spirits of famous authors. Guests enjoy snacks and beverages as they gather in the historic home for a chilling night of Victorian lore. 8:45 p.m.-midnight. 1340 Pennsylvania St., (303) 832-4092.

Bridge of Lights

Nov. 1-Dec. 31 • Cañon City

Drive across the Royal Gorge Bridge, 956 feet above the Arkansas River, decorated with thousands of twinkling holiday lights. It’s the only time of year cars are allowed on the suspension bridge, offering a festive way to experience this Colorado landmark. 4218 County Road 3A, (719) 276-8320.

Turkey Trot

Nov. 27 • Avon

Work up an appetite before your feast with a 2K or 5K walk/run around Harry A. Nottingham Park. Festive costumes encouraged and prizes awarded. The family-friendly race starts at 9:30 a.m. 1 Lake St., (970) 748-4000.

Creede Chocolate Festival & Holiday Market

Nov. 28-29 • Creede

Sample homemade chocolate creations from tortes and tiramisu to jalapeño fudge and chocolate-dipped bacon. Festivities run 11 a.m.-4 p.m. both days, with Black Friday shopping specials, Saturday’s Holiday Market, live music and a Parade of Lights and tree lighting Saturday at 5 p.m. (719) 658-2374.

Yuletide & Winterfest

Nov. 28-29 • South Fork Friday’s tree lighting (4:30-7:30 p.m.) at the Visitor Center features Santa photos, carols, cocoa and 50 decorated trees. Saturday’s Winterfest Craft Show (9 a.m.-3 p.m.) brings 24 vendors to the Rio Grande Club & Resort. Free event; attendees asked to bring food donations. 28 Silver Thread Ln., (719) 873-5512.

of Lights

Nov. 28 • Wray

Wray’s Main Street glows with lights, floats and music during this beloved tradition. Local businesses decorate floats, families gather along the route and Santa arrives to launch weeks of holiday celebrations. (970) 332-3484.

Best of the West Prism

Dec. 5 • Grand Junction

Colorado Mesa University showcases its top ensembles in a one-night showcase at the Asteria Theatre. Performances include the CMU Wind Ensemble, Rowdy Brass Band and guest artists of the NSSS Quartet. 864 Bunting Ave., (970) 986-3000.

Summit for Life

Dec. 6 • Aspen

Hundreds of athletes take to the slopes of Aspen Mountain to ski, snowshoe, run and hike 3,267 feet of vertical uphill over 2.5 miles. The race begins at Gondola Plaza and ends at the Sundeck. This beloved nighttime race fundraises money for organ transplants. 601 E. Dean St. (970) 710-2626.

Olde Fashioned Christmas

Dec. 5-6 • Palisade

Begin the annual event with hot cocoa and a prime view of the Parade of Lights downtown at 5:30 p.m. on Friday. Saturday brings breakfast with Santa and a gingerbread house competition and showcase. Other activities include carriage rides, a winter faire and soup contest. (970) 464-7458.

Georgetown Christmas Market

Dec. 6-7, 13-14 • Georgetown Georgetown transforms into a European-style market. Browse artisan gifts, sip cider, ride wagons and watch the daily Santa Lucia procession at noon. Carolers and historic tours add old-world charm. (303) 710-2840.

Two Shot Goose Hunt

Dec. 10-12 • Lamar

This 58th annual hunt includes a welcome reception, auction and two days of goose hunting. Athletes and celebrities have joined in past years. Proceeds support charities and boost local tourism. Lodging fills quickly; non-hunters can enjoy evening receptions. (719) 940-7424.

Festival of Trees

Dec. 11 • Craig

Craig’s signature holiday event celebrates the season with a “Wilderness Wonderland” theme. Local businesses and residents compete for best-decorated tree. 775 Yampa Ave. (970) 824-2335.

Beckwith Ranch Victorian Christmas

Dec. 13-14 • Westcliffe

Beckwith Mansion opens 11 a.m.-4 p.m. with decorated rooms, Santa and Mrs. Claus photos, ornament crafts and refreshments. Guests vote for favorite décor. Celtic High Mountain Strings play Saturday; traditional Christmas music fills Sunday. 64159 Hwy. 69 North.

Fremont Frost Holiday Market

Dec. 14 • Florence

This one-day event fills Pathfinder Park Event Center with artisans, crafters and makers selling seasonal gifts and décor. Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. 6655 Hwy. 115

Snow Cat Parade & Fireworks

Dec. 31 • Steamboat Springs

Celebrate at Steamboat Resort starting 5 p.m. as snowcats decked in lights parade down the slopes, followed by torch-lit ski runs. Fireworks explode at midnight. Free to attend; check Steamboat’s app for weather updates. 2305 Mt. Werner Circle, (800) 922-2722.

movies before quitting acting in his teens.)

6

7

8 b. Tim Allen

9 a. Bob’s Burgers

10 c. Lon Chaney

11 False (He did two

Trivia Photographs

Page 14, Top Amy Adams in Disenchanted

Page 14, Bottom Tim Allen in Home Improvement

Page 15 Harold Lloyd in Safety Last!

INA RESTORED storefront at the foot of Mesa Verde, the steady clank of an antique letterpress echoes off pressed-metal ceilings. The scent of oil and ink drifts through the air as artists roll paper across a massive drum built more than a century ago. Visitors step in from Grand Avenue to watch the old machine thunder back to life.

Once silent for decades, a 19th-century press now powers creativity in southwestern Colorado.

by ERIC PETERSON

The Mancos Common Press, a nonprofit arts hub, embodies the town’s reinvention – shifting from ranching and timber roots to a creative district where the antique Cranston press now drives art, education and community life.

Mancos, a town of about 1,200 in southwestern Colorado, grew up on ranching, farming and timber. Today the press serves as a bridge between that past and a new identity as a center for creativity and community. That dual identity makes the preservation of its historic press even more meaningful.

It’s a remarkable second act for a building that once seemed destined for the scrap heap. The Mancos Times began publishing

in 1893 and, after becoming the Times-Tribune, moved in 1910 into a fireproof concrete structure on Grand Avenue. Inside, a J.H. Cranston & Co. press printed local news until the paper merged with the Cortez Journal in the 1970s. The presses went silent, the windows were boarded and the building sat untouched for decades.

That changed in 2013 when faculty and students from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design and its Center for Architectural Conservation pried open the boards and discovered a time capsule: the intact Cranston press, trays of type, typesetting benches, even ink still clinging to rollers. Stacks of bound newspapers preserved a century of local history. Ballantine Communications, the building’s owner, donated it all to a new nonprofit, and with help from the Colorado State Historical Fund, preservationists began the long process of repair.

The restoration was painstaking. Specialists cataloged every ceiling tile before removing them to install new HVAC, then replicat-

The restored storefront of Mancos Common Press anchors the town’s new creative community. The shop showcases relics like an antique J.H. Cranston & Co letterpress and offers classes and a residency program to teach a forgotten art.

ed missing pieces in Penn’s fabrication lab. Workers uncovered original paint schemes –sky-blue walls, gray woodwork and a yellow frieze – and restored them based on historic documentation. A rear wall altered over the years was rebuilt from a 1911 photograph, and the ornate metal façade was carefully preserved. By 2019, the Cranston press was once again operational.

Shop manager Jody Chapel, who moved from Denver with her husband that year, said she was surprised to find such robust printmaking facilities in a small town. Classes began with simple card-making sessions and grew into full training programs, and today about 25 artists are active members.

One of the earliest was Teri McKay, who moved to Mancos in 2016. A self-described “maker,” McKay prints cards with cheeky wordplay and creates colorful linocuts. She said the variety of old fonts was what first drew her in. The press, she added, has helped connect different parts of the community and shown that both his-

tory and creativity are valued in Mancos.

The new Mancos Commons broadened that reach. Its sustainable design includes rooftop solar and water-saving landscaping, and upstairs apartments rent below the town’s rising market rates. Margaret Hunt, former executive director of Colorado Creative Industries, noted that those apartments could house teachers or others who might not otherwise be able to afford property in town.

Residency programs now bring artists for 10-day stays that include lodging, supplies and full studio access. Fruita-based printmaker and Colorado Mesa University instructor Devan Penniman was the 2024 artist-in-residence. She spent her days inking rollers and printing postcards of endangered species – the Mexican spotted owl, black-footed ferret and Mancos milkvetch.

Penniman described the work as grounding and said the smell of a long-lived print shop added to the experience. She also tells her students that letterpress remains rele-

vant, even in an age when artificial intelligence and digital tools dominate.

For Penniman, the connection reaches back to Gutenberg’s invention nearly six centuries ago. “The letterpress changed everything,” she said. She said it was a rare chance to work with technology that had once transformed the world. She left Mancos with renewed appreciation for the community, calling it a rejuvenating experience.

Once a boarded-up relic, the Cranston press and its companion Commons now embody both preservation and reinvention – an old machine put to new use, a restored building alive with classes and residencies, and a community demonstrating how heritage and creativity can thrive together.

Visitors can see the press in action, join a workshop, or view exhibitions in the Mancos Commons. Artist memberships and the annual residency are available at mancoscommonpress.org or at the Grand Avenue storefront.

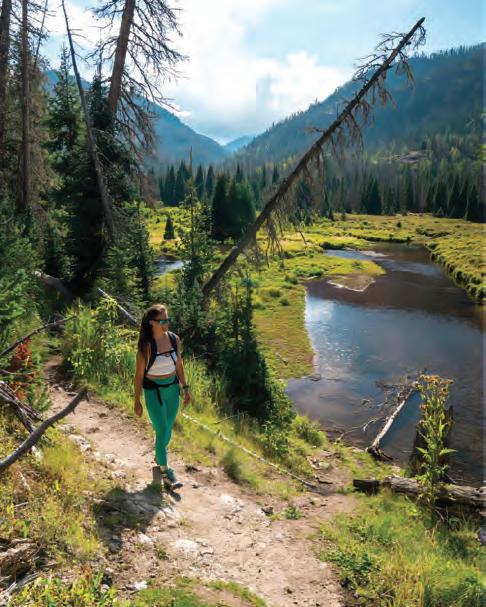

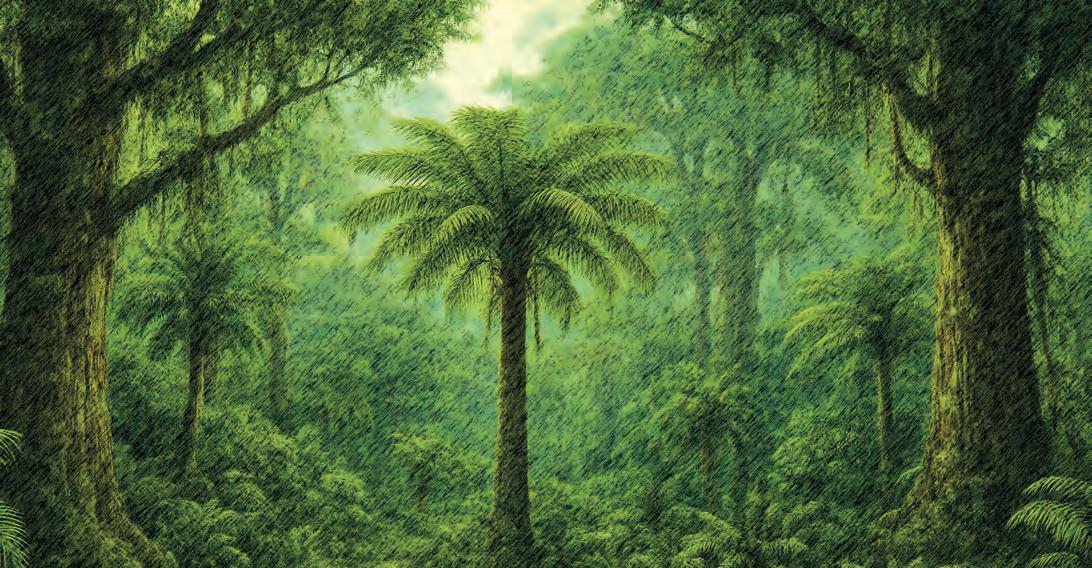

by JOSHUA HARDIN

APHOTOGRAPHER’S DREAM autumn adventure awaits in the Elk Mountains near the ski town of Crested Butte. Though it’s too early to hit the slopes, the hills are ablaze with autumn color. Carpets of chestnut ferns, orange oak brush and aspen groves turning from lush green to gold sit below jagged, russet peaks dusted with snow.

This isn’t just one of Colorado’s most colorful autumn drives. The 31-mile Kebler Pass route is also a rolling classroom for photographers. From sweeping panoramas of golden aspen to close-ups of ferns, Kebler Pass offers lessons in light, composition and timing that you can take home in your own images.

First, pronounce it right: Kebler has one e, not two like the cookie company. Sorry, no tree-dwelling elves here, just a lot of leaves and maybe a squirrel or two. Pack your own snacks.

Kebler Pass Road, Gunnison County Road 12, forms the northeast loop of the West Elk Scenic Byway. It links State Highway 133 between Redstone and Paonia with Crested Butte and Highway 135, with forest, trailheads and campgrounds in between. The route bisects one of the world’s largest aspen forests, akin to Utah’s famed “Pando.” These trees are genetically identical clones sharing a single root system, making the forest one massive organism.

Though the drive looks like a shortcut, it can take up to two hours without stopping. Expect traffic on fall weekends with leaf peepers and the occasional rancher moving cattle. Most of the road is unpaved but well-graded, passable in two-wheel-drive vehicles in summer and fall. It closes in winter after heavy snow. The slower pace means more chances to pull over for photos, and fewer windshield chips from loose gravel.

I recommend driving west to east the

first time. The most photogenic views reveal themselves more naturally in that direction. Landscape photographers, however, will find unique angles going either way. Wildlife watchers may see elk, deer, moose or birds, and I once saw a black bear near the Paonia end.

The road begins south of Paonia Reservoir, following Anthracite Creek as Ragged Mountain looms into view. Near Erickson Springs Campground and the Dark Canyon Trailhead, hikers can access the Raggeds Wilderness. Backpackers find endless rocky spires here. The jagged Ruby Range and the Beckwith Mountains that dominate this region are volcanic intrusions that pushed up through older layers of sedimentary rock, leaving behind dramatic silhouettes that are as much geology lessons as they are photo subjects.

Soon, the panorama of the Beckwith Range appears, a classic Colorado shot. Sunset bathes the peaks in amber light, often accented by billowy afternoon clouds. For photographers: a telephoto lens compresses the peaks and aspen into tight layers, while a wide-angle emphasizes the vastness of the scene. Each year brings different leaf color and retention depending on weather, so no two visits look the same.

Looking east, Marcellina Mountain rises beyond a curving canopy of aspen. Try framing the gravel road as a leading line, then zoom in for detail shots of kaleidoscopic trunks and ferns in the underbrush.

A short detour leads to Lost Lake Campground. Both the lake and the nearby slough shine at sunrise or sunset. Calm mornings often give crystal-clear reflections. Bring a tripod and polarizer, rotate gently to cut glare, but don’t overdo it or the reflection vanishes. Campers have the advantage for those first-light shots.

Another highlight is Horse Ranch Park, rivaling the Beckwith panorama as the most photographed site along Kebler. Sunset here ignites the Ruby Range, aptly named for its reddish peaks glowing in warm evening tones. The aspen stands display the full spectrum of fall: yellow, green, orange, even rare reds.

Above 10,000 feet, snow lingers on the shoulders of the pass. High-contrast scenes of snow and dark conifers are perfect for black-and-white photography. Switch your camera’s preview to monochrome to pre-visualize tones. Hikers can also explore the Ruby Range’s east slope, including the 2-mile trail circling Lake Irwin, a quieter alternative to Lost Lake for reflection hunting.

The drive ends as Mount Crested Butte dominates the horizon. The town greets travelers with galleries, restaurants and colorful historic architecture, a final photo op after one of Colorado’s most vibrant autumn drives.

Josh shot the paved end of Kebler Pass near Crested Butte with a Nikon D500 and 70-300mm lens at 70mm, f/11, 1/400 sec, ISO 200.