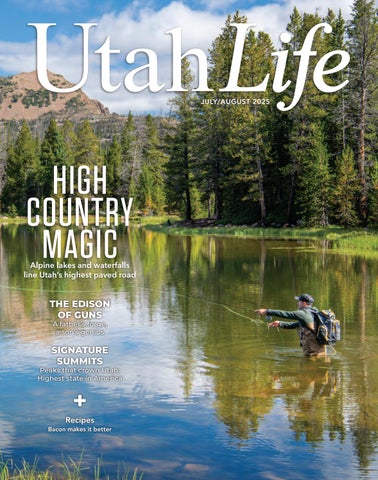

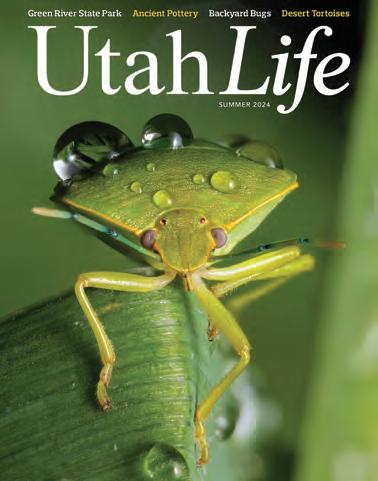

JULY/AUGUST 2025

JULY/AUGUST 2025

Alpine lakes and waterfalls

line Utah’s highest paved road

THE EDISON OF GUNS

Peaks that crown Utah: Highest state in America

A father’s forge, a son’s genius +

Recipes Bacon makes it better

4-6

Host John Florence shares true stories behind the music that defined the culture. With the Grateful Dead as a jumping off point, the show celebrates music made in the moment by the legends, plus artists of today, and influences of the past.

6-10 PM: Jazz Time

From ragtime to bop, from Havana to Paris to SLC, from Billie Holiday to Joe Lovano, host Steve Williams is your guide through the many varieties of jazz music – past and present.

10 PM-Midnight: The Edge of Jazz

Explore what jazz is with host John Northup – the high peaks and low valleys, the glossy and the gritty.

LISTEN: UPR.ORG OR UPR MOBILE APP

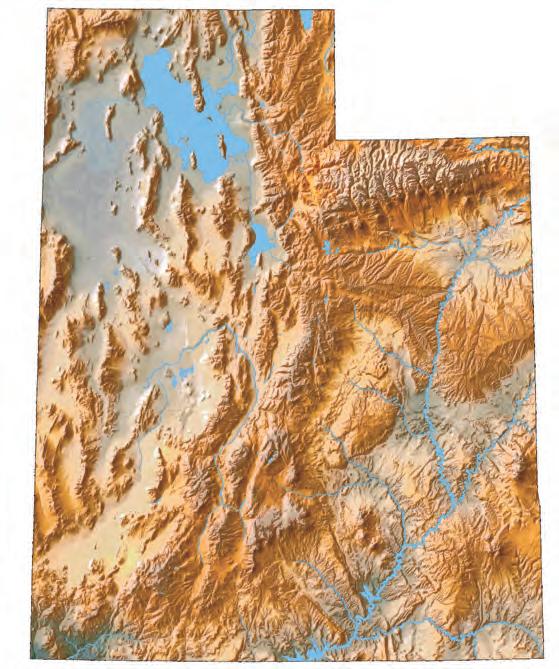

Tremonton, pg. 8

Ogden, pg. 16, 28

Salt Lake City, pg. 6, 35

South Salt Lake, pg. 12 Kamas, pg. 20

Alta, pg. 33

Provo, pg. 30

Delta, pg. 32

Kanosh, pg. 7

Beaver, pg. 34

Green River, pg. 42

Moab, pg. 31

Hanksville, pg. 32

Bluff, pg. 43

A fly fisherman casts at Teapot Lake, a highalpine oasis along the Mirror Lake Scenic Byway. Story begins on page 20

Photo by Joshua Hardin

12 South Salt Lake’s Color Revolution

Kanosh named after a Pahvant Ute chief; brine flies’ vital role at Great Salt Lake; honoring the Borgstrom brothers. 10 Trivia

Put your road smarts to the test. Answers on page 44.

36 Kitchens

Tiny bites, big flavor – everything’s better with bacon.

40 Poetry

Capturing the shimmering beauty of Utah’s desert summers.

42 Explore Utah Green River’s Melon Days; creativity in full bloom at the Bluff Arts Festival.

46 Last Laugh Dad bods, disaster and waterslide glory make for slippery misadventures.

More than 80 murals are transforming South Salt Lake into Utah’s largest open-air gallery, sparking community pride and creativity. by Tim Gurrister

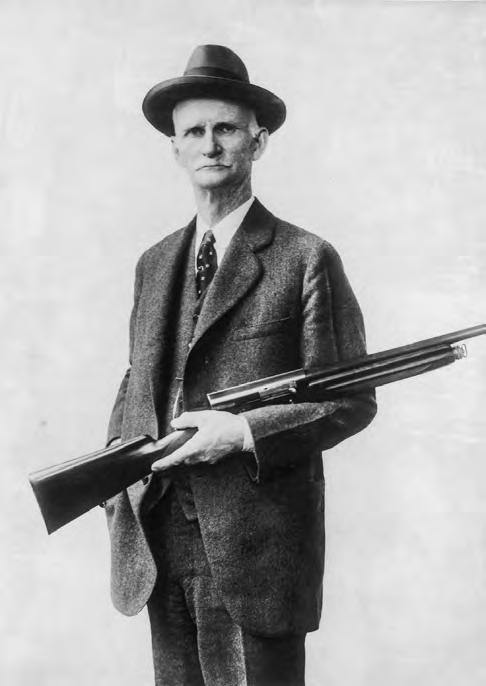

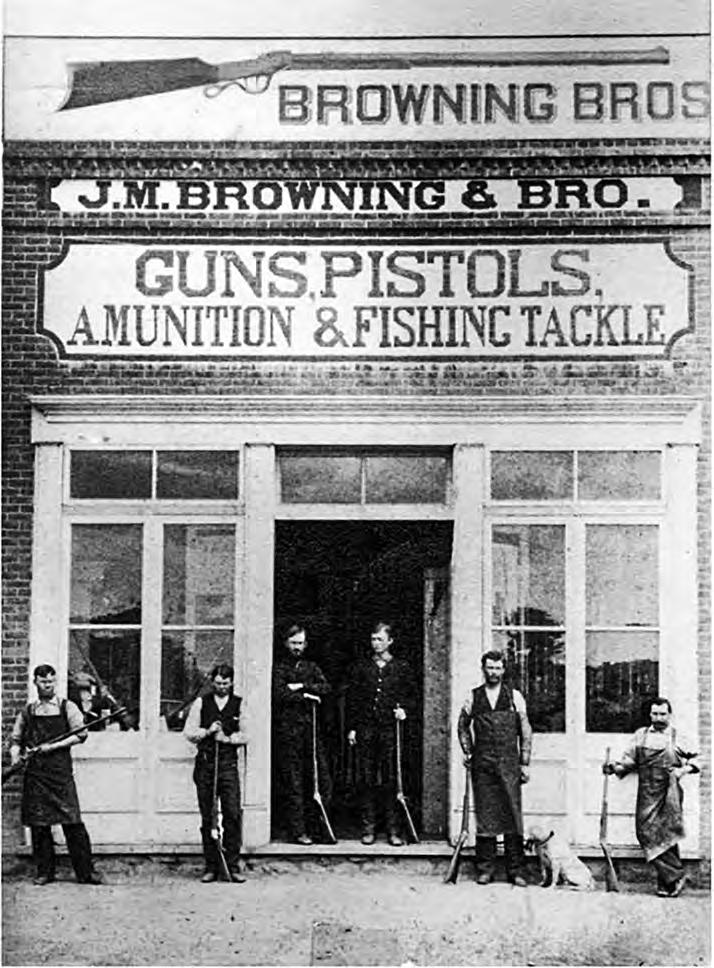

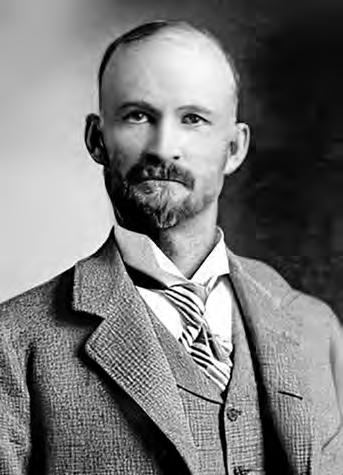

16 The Edison of Guns

How John Moses Browning of Ogden became the world’s most prolific firearms inventor – and an enduring legend. by Ron J. Jackson Jr.

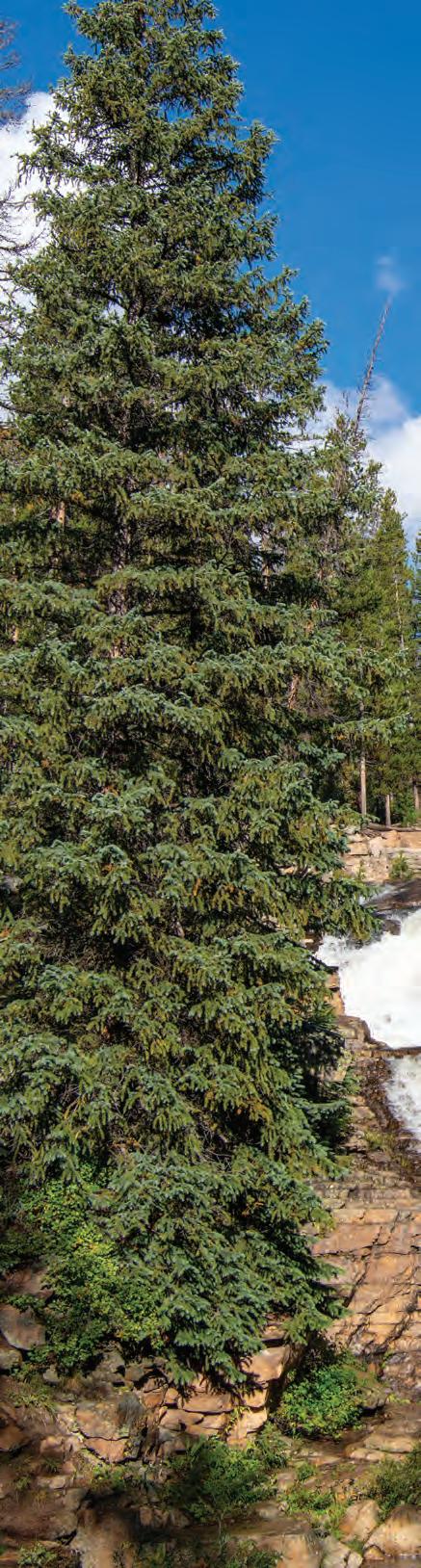

20 Mirror Lake Scenic Byway

This enchanting drive climbs Utah’s highest paved pass, where alpine lakes, tumbling waterfalls and rugged peaks create storybook scenery. story and photographs by Joshua Hardin

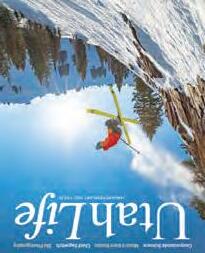

28 Signature Summits

Dub Bludworth’s quest to climb every county high point – and prove, once and for all, that Utah is America’s most mountainous state. by Matt Masich

UTAH IS A place where curiosity sparks innovation, and where the best stories prove their worth by lasting. Some ideas are so bold they change the world, while others become simple, enduring parts of daily life passed from one generation to the next.

Philo T. Farnsworth’s invention of television in 1927 and Frank Zamboni’s creation of the ice-resurfacing machine in 1949 show Utahns’ gift for turning ideas into reality. Ingenuity thrives not only in labs, but in our mountains, alleys and waterways. It runs through irrigation systems that turned deserts into farmland, through the Golden Spike that bound a nation, and through the imagination that continues to shape this state.

No story embodies this more than that of John Browning. Known as the “Edison of Guns,” he dismantled and redesigned firearms with meticulous care, blending skill, creativity and persistence. As Ron J. Jackson Jr. shows so vividly in this issue, Browning’s genius was forged not only in metal but in the relationship with his father – and in the quiet drive to earn his approval. The world’s most prolific gun designer began not with acclaim, but in a modest Ogden workshop, under a father’s watchful eye. That same inventive impulse shows up in unexpected places. What began as a handful of murals in 2018 around South Salt Lake has blossomed into Utah’s largest open-air gallery. More than 80 works now cover industrial gray walls with vivid color, transforming neighborhoods and sparking wonder in everyone who passes by. Utah’s peaks inspire, too. Dub Bludworth’s quest to climb all 26 county high points revealed not only the state’s soaring elevations, but also the drive to achieve something ambitious. His findings crown Utah as America’s most mountainous state, a title we wear with pride.

The Mirror Lake Scenic Byway offers yet another form of ingenuity: roads, overlooks and campgrounds designed to bring us into nature safely and beautifully. Roads also take center stage in this issue’s Trivia section – how much do you know about Utah’s highways and byways?

Across inventions, art and adventure, one thing is clear: Utahns don’t wait for solutions – we create them. The next great idea may be taking form in a backyard workshop, a school art project or a trail-side conversation.

From a father’s forge in Ogden to the peaks, murals and byways of today, Utah’s spirit of ingenuity endures. Thank you for joining us in these pages. If you’ve enjoyed reading, I invite you to subscribe, renew or share the gift of Utah Life – stories that endure.

CHRIS AMUNDSON Publisher & Editor editor@utahlifemag.com

July/August 2025

Volume 8, Number 4

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Photo Coordinator

Erik Makić

Staff Writer

Ariella Nardizzi

Design

Mark Del Rosario

Lydia Paniccia

Editorial Assistant

Savannah Dagupion

Advertising Sales

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Shiela Camay

Intern Lucy Walz

Utah Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130

Fort Collins, CO 80527 (801) 921-4585

UtahLifeMag.com

Subscriptions are $30 for 6 issues and $52 for 12 issues. To subscribe and renew, visit UtahLifeMag.com or call (801) 921-4585. For group subscription rates, call or email publisher@utahlifemag.com.

Send us your letters to the editor, story and photo submissions, story tips, recipes and poems to editor@utahlifemag.com, or visit UtahLifeMag.com/contribute.

For rates, deadlines and position availability, call or email advertising@utahlifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork is copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@utahlifemag.com.

by SCOTT BAXTER

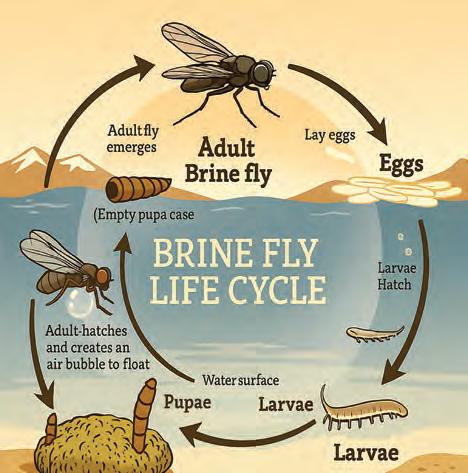

If you’ve ever had a sibling who barely lifted a finger but somehow always got the credit, then meet the brine fly – the unsung hero of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Kids everywhere have grown up fascinated by Sea Monkeys© (brine shrimp) – Utah’s official state crustacean. But have you ever heard of anyone proudly owning a pet brine fly? Probably not. Even Utah overlooked this tiny native creature, naming the industrious – but imported – Western honeybee as its state insect instead. Honeybees get the limelight but compared to the brine fly, they’re featherweights.

Tourism brochures are eager to talk about charming bees or quirky shrimp, but ask them about the 100 billion brine flies inhabiting the Great Salt Lake and watch their enthusiasm vanish. Tell them about the piles of pupae casings – up to 370 million per mile of shoreline – and they’ll likely recoil in disgust. Yet, ask a naturalist at one of the lake’s State Parks and you’ll hear a different story. To them, these mounds of casings aren’t revolting – they’re one of nature’s miracles, like strolling on a feather

bed made entirely of tiny cocoons.

During the icy grip of winter, brine fly larvae hunker down dormant at the lake’s bottom. But when spring’s warmth awakens them, these voracious creatures consume a staggering 120,000 tons of algae and organic matter each year – the equivalent weight of 2.4 billion hot dogs! By early summer, fat and content, they’re ready for metamorphosis. Anchoring themselves onto microbialites – rocky underwater formations built from calcium, magnesium and cyanobacteria – the larvae create pupal cases. These microbialites aren’t just convenient anchors – they’re vital ecosystems, housing up to 25,000 larvae per square meter. They even helped create Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere, making life possible – including brine flies themselves.

The flies’ transition from larvae to adult is nothing short of magical. Encased within their pupal cocoons, they trap air bubbles and float gracefully to the lake’s surface –reminiscent of the Jetsons commuting in bubble cars. Upon emerging, adult brine flies have only days to complete their singular mission: mate and lay eggs. There’s no time for meals or lounging – just urgent,

fleeting romance. The newly laid eggs drift down to restart the life cycle. Some flies manage to pull off two complete cycles in a single summer.

Aside from reproducing at breakneck speed, brine flies are remarkably polite: they don’t bite humans. More importantly, they’re a cornerstone of the lake’s food chain. Want to locate microbialites easily? Forget expensive sonar equipment – just follow the flies. On a calm July day, flies congregate above the microbialite mats on the bottom of the lake, with newcomers arriving in tiny bubbles like bubbles rising in a glass of champagne.

Brine flies draw an impressive crowd –more than 10 million birds from 330 species visit annually, turning the lake into a grand avian buffet. California gulls hilariously

A vital link in the lake’s food chain, brine flies swarm in clouds, feeding on algae and organic matter while also serving as a prominent food source for visiting birds.

sprint open-mouthed through swarms of flies like nature’s snowblowers. Even more fascinating are the phalaropes, quirky shorebirds known for their extravagant appetites and unique mating rituals. Phalaropes gorge until they’re too plump to fly, converting fat to fuel for their extraordinary journeys to distant wintering grounds.

With half the world’s Wilson’s phalaropes and large numbers of Red-necked phalaropes stopping here each year, watching them spin like aquatic ballerinas as they stir up brine flies makes for nature’s perfect spectacle. Imagine pecking at 180 flies per minute – it’s a performance worthy of an arcade game.

Brine flies have long fed more than just birds. Explorer John C. Frémont noted in 1843 that the Northwestern Shoshone gath-

ered brine fly larvae as food. Farther west near Yosemite National Park, the Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe – whose name translates literally to “fly eaters” – also relied heavily on brine fly larvae and pupae. Even today, spiders feast abundantly at Antelope Island State Park, where orb-weavers become so numerous that visitors celebrate them at an annual Spider Fest.

Without brine flies – and their shrimp cousins – Utah’s beloved lake would lose its greatness, becoming instead just a Great Big Pool of Slimy, Smelly Goo. More seriously, without these tiny, tireless insects, millions of birds would face starvation. So perhaps it’s time to show a little love for the fly nobody loves. After all, the brine fly might just be Utah’s most overlooked – and essential – creature.

by VANESSA ZIMMER

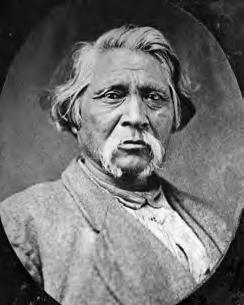

The Millard County town of Kanosh got its name from Chief Kanosh, the well-spoken, mustachioed leader of the Pahvant Utes in the mid-1800s, who is perhaps best known in Utah history for accepting white settlers in his central Utah territory, rather than fighting them.

Kanosh is said to have admired and gently pursued a young Bannock woman raised in the household of Brigham Young, president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and they were wed by Young himself. But it was a rocky road to marital bliss.

Three previous wives met violent deaths, according to a history in the Utah Humanities collection at the University of Utah. E.L. Black wrote in a brief biography that the chief’s first wife had the “misfortune” of losing her mind and was killed by the tribe, fearing that she was possessed by an evil spirit. His third wife, a beautiful Cherokee and expert horseback rider, had her throat cut by the jealous second wife, who in turn was sentenced to die by starvation.

Kanosh means “willow bowl,” according to Utah place names guru John Van Cott, and was the name given to the man as a baby because he enjoyed playing with his mother’s willow bowl.

Pahvant Ute Chief Kanosh was known for his well-spoken manner and acceptance of white settlers. The Millard County community was named for him.

A quiet stretch of road through Box Elder County now bears the name of four brothers who gave everything in World War II –and the hometown that never forgot them

by TIM GURRISTER

The signs along Highway 102 in northwest Box Elder County have been replaced with new ones reading “Borgstrom Brothers Memorial Highway.” It’s a long-overdue tribute to four brothers from Tremonton who all died in a six-month span during World War II.

The last time Clyde, LeRoy, Rolon and Rulon Borgstrom made headlines was Memorial Day 2024, when a $30,000 monument replaced their modest headstones and white crosses at the Tremonton cemetery. On that day, Mayor Lyle Holmgren shared his research on the brothers’ service and sacrifice.

Holmgren quoted a series of wartime newspaper clippings:

“Clyde Borgstrom reported killed in South Pacific”

“Second Borgstrom son killed in action”

“Box Elder parents lose third son in battle”

“Mourn 4 sons – want 5th home”

“Last son denied furlough”

“1 of 5 Borgstrom boys is coming home – alive”

Gunda and Alben Borgstrom raised 10 children, including five sons who served during the war. Clyde Eugene Borgstrom died on March 17, 1944, while operating a bulldozer to build an airstrip on Guadalcanal. LeRoy Elmer Borgstrom was killed on June 22, 1944, in Italy while carrying a wounded soldier under fire. Rolon Day Borgstrom died Aug. 8 in England from injuries sustained as an aerial gunner in a bomber crash. Rulon Jay Borgstrom was killed on Aug. 25 in France near Brest after being reported missing in action.

Following Rulon’s death, military officials determined the family had endured enough. In October 1944, they recalled the fifth son, Boyd, from active duty and sent him home. Their youngest brother, Eldon, was exempted from any future military service due to the family’s devastating loss.

The brothers were posthumously awarded three Bronze Stars, one Air Medal and one Good Conduct Medal. Their experience became one of the most prominent real-life examples that influenced the

formal adoption of the U.S. military’s Sole Survivor Policy in 1948.

The family’s tragedy has drawn comparisons to Saving Private Ryan – Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film about a similar true story involving the Niland brothers from New York. Like the Borgstroms, the Nilands lost multiple sons in the war, prompting the return of the surviving sibling.

Annette Hawkes Duccini of Farr West, whose mother Wilma was the Borgstroms’ sister, recalled the emotional toll the losses took on her family. “Every time they came to the door, she passed out,” Annette said of her grandmother, Gunda. Though the family was never consulted for the film, DreamWorks flew Wilma and Annette to the premiere as a gesture of recognition and respect. Annette still had the envelope from the studio, though the letter it once contained was missing.

Family archives include a condolence letter from the White House dated 1944,

In 2025, the brothers were honored through State Route 102, now known as the Borgstrom Brothers Memorial Highway, which runs through the heart of Tremonton.

which acknowledged the loss of three sons, with Rulon then still listed as missing in action. Annette remembered Boyd’s return from the war and the struggles he faced. “He came to our house asking Wilma for money,” she recalled. “I was just a kid – it was kind of scary.” Boyd later reconciled with his family just before he died in 1975.

Wilma also spoke of Gunda’s spiritual connection to her sons – including a dream the night Rolon died. “She sat up in bed and told my mother, ‘I saw it,’ ” Annette said. The next day, military officers arrived at their door.

As the war ended, national recognition followed – including a Life magazine feature and a 1948 state funeral in Tremonton. All four brothers’ bodies were returned together, and a joint service was held at the Garland Tabernacle on June 26, attended by generals, Utah Governor Herbert B. Maw, and President George Albert Smith

of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The community honored the family as Utah’s only four-star Gold Star family of the war.

Their memory lived on through later tributes. In 1959, an Army Reserve training center in Ogden was named the Borgstrom Center. A memorial stone bearing their names was also placed in Tremonton in 2001.

In 2025, more than 75 years later, that recognition became permanent. Utah Governor Spencer Cox signed legislation officially designating State Route 102 as the Borgstrom Brothers Memorial Highway. The road runs past the former Borgstrom family home and through the heart of Tremonton.

In naming the highway, the community has reclaimed a piece of its past – honoring not only the Borgstrom brothers, but the resilience of a hometown that still holds them close.

Experience the beauty, legacy, and historical value of Tooele

Open Every Tuesday Year Round 10 am-1 pm

Open Memorial Day through Labor Day Friday and Saturday • 10 am-4 pm

47 E Vine St • Tooele, UT 435-882-3168

TooelePioneerMuseum.org

Test your knowledge of highways, byways and thoroughfares.

by BRIAN WANGSGARD

1

The Lincoln Highway became the first transcontinental automobile road upon its completion in the early 1920s, crossing Utah by generally following the route used by what 1860s mail delivery service?

2

Along what 122-mile Utah scenic byway will you encounter four state parks, two national parks and a national monument?

3

For seven days this year, beginning Aug. 6, highways from St. George to Park City will host Tour of Utah participants using what mode of transportation?

4

What Utah town do fourwheelers visit to test their skills (and courage) on such off-road trails as Hell’s Revenge, Metal Masher and Poison Spider Mesa?

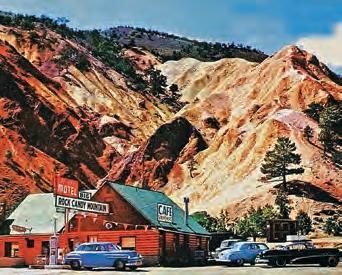

5 What huge “sweet treat” can be seen on the west side of U.S. Highway 89 between Interstate 70 and Marysvale?

6

Which of these states has the longest section of Interstate 15?

a. California

b. Utah

c. Montana

7 The half-mile Adams Avenue Parkway, opened in Ogden in 2001, is the only Utah example of which kind of highway?

a. Heated to melt snow

b. Private toll road

c. Paved with recycled plastic

8 The second-coldest temperature ever recorded in the Lower 48 states (69.3 below zero) occurred in Peter Sinks. The brave can visit it by driving through which canyon?

a. Logan Canyon

b. Ogden Canyon

c. Provo Canyon

9 Which most populous Utah town on U.S. Highway 50 set a Guinness world record for the longest bunny hop?

a. Delta

b. Salina

c. Green River

10

Ogden’s principal northsouth streets are named for every commander-in-chief from Washington to Grant, except for which unpopular, first-to-be-impeached president?

a. John Quincy Adams

b. Martin Van Buren

c. Andrew Johnson

11

12

There were no paved streets in Utah before 1906.

State Route 150 through the Uinta Mountains is popularly known as Mirror Lake Highway.

13

Zion National Park’s 1.1-mile Zion-Mount Carmel Tunnel is the longest in Utah and the entire National Park System.

14 Only Salt Lake City and Ogden have ever had electric streetcars.

15

Robert Redford’s Sundance Mountain Resort lies along the Alpine Loop Scenic Byway.

No peeking, answers on page 44.

HOW BLANK

– AND SPARKED A CREATIVE AWAKENING ACROSS THE CITY.

story by TIM GURRISTER photographs by STAN CLAWSON

SOUTH SALT LAKE WAS once a city of gray walls and empty lots – a place drivers passed through on their way somewhere else. But in recent years, a vibrant surge of street art has transformed this industrial corridor into Utah’s largest open-air gallery.

Since 2018, more than 80 murals have spread across the city’s brick warehouses, breweries and rooftops, creating a colorful patchwork that has redefined South Salt Lake’s identity. These giant artworks – some stretching several stories high – turned once-overlooked corners into destinations. Visitors found vivid murals

along Main Street, West Temple and the S Line, each one a fresh invitation to pause, look closer and explore.

Along 2100 South, a pair of landmarks showcased how much the neighborhood had changed. At Mr. Muffler, 105 W. 2100 South, a striking wolf mural prowled across the wall, its gaze fixed on passing cars. Two blocks west, the Freeway Plaza shopping center at 2180 S. 300 West was anchored by a swirling school of trout, splashing up the side of the building in a riot of color.

At Chappell Brewing, 2285 S. Main St., a cheerful script proclaimed: “Darling,

You Are a Work of Art.” Nearby, the Regency Apartments at 246 E. 2100 South brightened the neighborhood with bold reds, yellows and blues that flashed past train riders.

Murals even transformed city buildings. The once-plain rear façade of City Hall burst with organic bands of orange, gold and mint green that climbed four stories up the concrete and glass. Inside, staff said the art brought a sense of pride and optimism to their workdays.

Much of the momentum started with Mural Fest, an annual event that brings artists together to paint new works each

spring. The city selects walls, helps fund materials and hosts community gatherings where residents can meet the artists and watch the murals take shape.

Lucia Murdock, who opened a fine arts studio at 153 W. 2100 South the same year the first murals went up, remembered when the area felt drab and overlooked. Her building bloomed with five-foot flowers and painted bees – an installation she didn’t commission but felt deeply connected to.

“It just coincidentally matches my heritage and the vibe of the studio,” she said. “It makes it easier for people to find us and brings a pop of color to the street.”

Across South Salt Lake, murals became wayfinders and conversation starters.

At AMI Roofing, 141 W. Haven Ave., a powerful Ute figure in prayer rose above the parking lot, while a cowgirl lounged alongside Interstate 80 at 80 W. Robert Ave., catching the eye of drivers on the overpass.

Business owners often approached the city to request a mural, and sometimes the city reached out first if a building had good visibility. Once a wall was selected, property owners typically contributed a share of the artist’s fee. The guidelines were simple: no ads, no hate, no obscenity – and no single theme. The goal was to reflect South Salt Lake’s diversity, character and energy.

Salt Lake City artist Trevor Dahl, who painted a mural of a coyote, frog and bluebird nestled around a human skull, believed these public artworks did more than decorate walls. “They manifest a reality where the arts are valued and residents feel their neighborhood is cared for,” he said. “It gives South Salt Lake an identity apart from Salt Lake City – a sense of place.”

Davia King, who grew up in Orem, often sketched faces of onlookers into her murals using blind contour drawing – capturing their likeness without looking down at her hand. “It is a way of connecting,” she said. “All these faces overlapping become a message of humanity coming together.”

On sidewalks once ignored, people stopped to take photos or watch artists at work. Neighbors waved to painters on

lifts. Murals turned ordinary cinder block walls into landmarks – and helped create a community where creativity felt as much a part of the landscape as the Wasatch Mountains on the horizon.

“Art is one of the most profound ways to create beauty in the civilized world,” King said. “If we can’t have nature surrounding the buildings, then we paint it.”

In recent years, a vibrant surge of more than 80 murals has transformed the industrial corridor of South Salt Lake into Utah’s largest open-air gallery.

Darling, YOU ARE A WORK OF ART.”

by RON J. JACKSON JR.

IF HIS NAME APPEARED on the inventions of his manufacture the name of John M. Browning would today be more widely known than that of Henry Ford.”

– Philip B. Sharpe, author of The Rifle in America

The rhythmic ringing of a hammer striking an anvil was one of the first sounds to welcome John Moses Browning into the world. The sound echoed throughout his life, beginning with his earliest memories inside his father’s modest gun shop in Ogden.

Born Jan. 23, 1855, in Ogden, Utah Territory, John was the son of Jonathan Browning, a devout member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a respected gunsmith, and one of 22 children. Rutted wagon tracks led into the burgeoning settlement, marking a trail that dated to the great migration of 184647 and continued with pioneers pushing

west to the Pacific Coast. Inside, he found his childhood wonderland of tools and gun parts. Elizabeth Browning remembered her son, no more than 6, dragging a box into the shop as a makeshift bench beside his father’s sizeable junk pile. Jonathan never discarded metal, knowing its value on the frontier, so the pile constantly shifted and changed.

So, too, did his son.

Jonathan’s sharp memory recalled every part he had salvaged from battered firearms. When he needed a piece, he sent John to dig through “Pappy’s” pile, then clean off rust with a file and buffer. The shop was John’s gunsmithing classroom –arguably his only one. He attended school intermittently until 15 and preferred to shadow his father.

Jonathan had learned the trade in Tennessee. In 1824, at 19, he walked 30 miles to a Nashville gunsmith whose name he had seen stamped on a barrel, offering to

work free in exchange for lessons. He paid his dues.

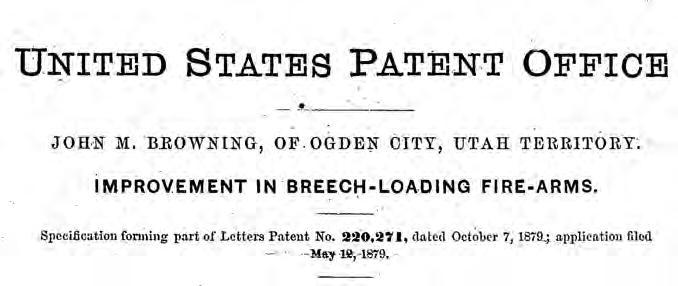

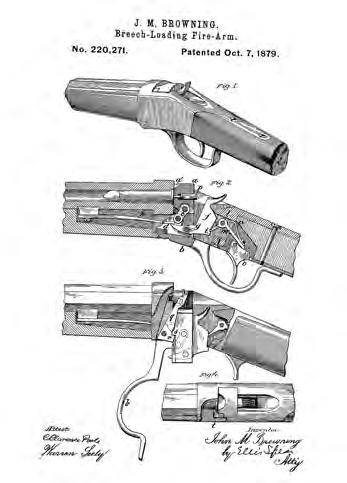

Under that tutelage, John memorized every part, learned its function and soon imagined ways to build better guns. From this beginning emerged one of history’s most prolific firearms inventors. He obtained 128 patents covering 80 distinct guns and is widely considered a pioneer of modern repeating, semiautomatic and automatic arms.

He earned his first patent Oct. 7, 1879, at 24, and later sold designs to such industry leaders as Winchester, Remington and Colt. His output was so prolific he became known as “the Edison of Guns.” Between Oct. 1884 and Sept. 1886 Winchester alone bought 11 of his guns.

Author Paul A. Curtis, a retired U.S. Army captain and firearms authority, wrote in 1931:

“It is difficult to find words to accurately describe John Browning’s achievements. To say that he was a great gun designer is inadequate; to say that he was the Edison of the modern firearms industry does not quite cover the case either, for he was even greater than that. There are and were many great men working along the same lines as Edison – Steinmetz, Westinghouse, Marconi and others too numerous to mention – but Browning was unique. He stood alone, and there never was in his time or before one whose genius along these lines could remotely compare with his.”

By the close of World War I, his reputation was secure. The U.S. Army Ordnance Corps asked if he could build a .50-caliber machine gun. On Sept. 12, 1918, he testfired the weapon in Colt’s pasture near Hartford, Conn. A month later – Nov. 15, four days after the Armistice – he fired 877 rounds in bursts of 100 to 150 before government officials. Reporters asked the Utah inventor to what he attributed the feat. Browning said, “One drop of genius in a barrel of sweat wrought this miracle.” It all traced back to Ogden.

THE FIRST GUN John created was as crude as Pappy’s workshop. Ten-year-old John enlisted 5-year-old brother Matt while their father ran errands. He dug out a busted flintlock stock, a scrap of wood

three prairie chickens dusting within 40 to 50 feet.

John knelt, shouldered the stock and whispered, “Now.” Matt’s first jab singed John’s hair. The second set off the crude gun. Recoil knocked John down – “I went down on my hunkers,” he later said. Smoke cleared to reveal one bird dead, two crippled. Matt chased them down, “a bird in each hand, whooping and trying to wring both necks at once.”

Celebration soon gave way to dread. They had to explain using Jonathan’s powder.

Elizabeth offered cover: “In the morning we’ll have prairie chickens and biscuits for breakfast,” she said. Jonathan started eating before the boys were called in. When he asked where the birds came from, John told the story, including the stolen powder.

Jonathan said nothing, finished his meal, then asked, “John Mose, let me see that gun.” He examined it, set it down and said, “John Mose, you’re going on 11; can’t you make a better gun than that?” He walked to the shop.

John was crushed. He followed, unwound the wire, broke the stock over his foot and tossed the pieces on the kindling pile – then went back to work. The sting fueled him.

Three years later, just after his 13th birthday, fate handed him a challenge. As the story goes, a freighter, whiskey on his breath, brought in a mangled single-shot percussion shotgun. Repairs would cost more than a new gun, so the freighter bought one of John’s reconditioned pieces for a $10gold piece and, as he left, tossed the wreck to John: “Hey, younker, want a gun?”

The teen stared at the ruin, cursed and drew his father’s rebuke. Then came clarity. “Boy-like, I had been trying to do the job all at once with some kind of magic,” he later said, “and magic never made a gun that would work.”

and a few feet of wire, clamped the barrel in a vise and sawed off the damaged muzzle. Matt filed a strip along the barrel to clean metal while John hatcheted a threefoot stock, then wired and soldered barrel to wood. A tin cone screwed near the flash hole kept priming from flashing back. The gun had no hammer or trigger.

They peered outside to ensure Jonathan was gone, then stole enough powder

and shot from his hidden hoard. Powder was precious, and their father a stern disciplinarian.

The plan was simple, risky. John told Matt to heat a pine sliver in smoldering coals until it glowed and thrust it into the priming pan. Barefoot and anxious, they slipped into open country minutes from the shop. Frontier hunters shot into packs of fowl to save powder, so the boys stalked

Through the night he dismantled the gun “down to the last screw” and realized he could make every part himself. He forged replacements on the foot-powered lathe Jonathan had hauled from Illinois in 1852. Weeks later he finished the barrel. Jonathan, rarely given to praise, let him saw stock wood from a prized walnut plank. “Pappy nearly came right out and said so,” John joked years later.

He would say he could have invented a gun at 20, but invention still seemed “far beyond the mountains, mysterious.” The transformation was gradual, though Jonathan noticed. One January day in 1878, shortly before John’s 23rd birthday, he studied an odd factory gun and muttered, “I could make a better gun than that.”

“I know you could, John Mose,” Jonathan said, locking eyes. “And I wish you’d

get to it. I’d like to live to see you do it.”

Jonathan sold the shop to John and Matt for $500 on Jan. 7, 1878; Browning & Bros. was born. Matt kept the books; John sketched designs. On May 12, 1879, he applied for his first patent, the John M. Browning Single Shot Rifle. The patent was granted Oct. 7, 1879, as U.S. Patent No. 220,271 – less than four months after Jonathan died June 21, 1879, at 74.

John thought his father died “of weariness,” but not before knowing his son had become a gunmaker. Before passing, Jonathan test-fired the prototype.

“He stood as straight as he had at the turkey shoots in Tennessee,” John recalled. “Loaded, closed the action, fired, snapped out the empty and asked for another cartridge.”

No words were necessary.

The fairest road trip of them all

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOSHUA HARDIN

1. Kamas

2. Provo River Falls

3. Teapot, Lily and Lost Lakes

4. Bald Mountain Overlook

5. Mirror Lake

6. Hayden Peak Overlook

7. Christmas Meadows

8. Bear River Ranger Station

MIRROR, MIRROR, ON the wall – what’s the fairest road trip of them all?

Drivers don’t need a queen’s magic mirror to discover one of Utah’s most enchanting routes. Less than two hours from Salt Lake City, the Mirror Lake Scenic Byway winds through staggering vistas of craggy peaks, verdant forests, rushing rivers and roaming wildlife – scenery sure to charm any fairytale princess.

This stretch of State Highway 150 climbs into the Uinta Mountains, a smooth ride into rugged high country. Motorists and cyclists alike savor the paved curves as the road rises from 6,690 feet in Kamas to 10,715-foot Bald Mountain Pass – the highest paved road in Utah. The 55-mile journey to the Wyoming state line takes at least half a day, though overnight stays at campgrounds along the way make for longer, more immersive experiences beneath star-studded skies.

The byway is free to drive, and it typi-

cally opens in mid-May and closes in midfall when snow makes plowing impossible. Some recreation areas along the route require a pass (see sidebar for details).

The byway offers seven sensory delights for travelers heading into the forest. The journey begins in Kamas – the “Gateway to the Uinta Mountains.” According to legend, Ute guides revealed the location of a gold mine to pioneer Thomas Rhoads, on the condition he never share it. He kept the secret, and the mine’s location remains unknown.

Before heading out, stop at Samak Smokehouse & Country Store (Samak is “Kamas” spelled backwards). No poison apples here, but smoked trout, cheeses, jerky and trail snacks make ideal provisions for the road. The nearby Chevron station is known for hot coffee and giant fritters – another local favorite before the climb. Note: there are no gas stations beyond Kamas, so fill up before you go.

Hayden Peak Overlook (top) reveals a jagged summit rising above dense forest.

A sign at a Mirror Lake trailhead (bottom left) welcomes visitors to the 53-acre, 36-foot-deep lake. Bear River Ranger Station (bottom right) provides a scenic picnic stop.

Soon after leaving town, the byway parallels the Provo River – a blue-ribbon fishery teeming with brook, rainbow and cutthroat trout. The river’s most dramatic feature is Upper Provo River Falls, about 24 miles into the drive. A terraced cascade tumbles into a rocky gorge, with footpaths leading to the lower tiers where visitors sometimes wade – though currents remain brisk and cold even in summer.

Early morning offers the best photography – even light before shadows and bright reflections complicate the shot. Weather changes fast, so dress in layers, apply sun protection and bring mosquito repellent. Binoculars come in handy for spotting birds on distant ridges.

Above the falls, a cluster of tranquil alpine lakes emerges. Teapot, Lily and Lost lakes sit directly beside the byway, while others, like Trial and Washington, require short drives on Forest Service roads. Most are ringed with trails perfect for a light stroll or to stretch your legs before longer treks. Moose frequent the marshy edges. Deer and elk are common too, while black bears and mountain lions appear only rarely. Osprey, bald eagles and mountain bluebirds also draw birders to the region. Chipmunks and marmots dart across the rocks, their quick movements delighting kids and photographers alike.

A short detour up Forest Service Road 102 leads to Bald Mountain Overlook. Here, visitors are rewarded with a panoramic view of technicolored crags formed from green-gray shale and 600-million-yearold orange quartzite. Unusually, the Uintas run east to west – one of the few such mountain ranges in North America.

The overlook also marks the trailhead for the 2.7-mile round-trip hike to Bald Mountain’s 11,943-foot summit. It’s a strenuous climb with more than 1,100 feet of elevation gain, but the sweeping alpine views and open-air serenity make it worthwhile.

Along the byway, alpine lakes (above) offer serene settings for kayaking, spotting wildlife and light strolls. About 24 miles in, Upper Provo River Falls (middle) currents remain brisk and cold year round. A scenic byway sign (right) marks about 2 miles above Mirror Lake.

At just over 10,000 feet in elevation, the byway’s namesake lake is a showstopper. Mirror Lake covers 53 acres, reaches 36 feet deep, and holds rainbow, brook and tiger trout. It lives up to its name – perfectly reflecting Bald Mountain and its neighbors on still mornings.

By mid-morning, the shoreline fills with anglers and picnickers, while inflatable boats, paddleboards and canoes dot the water. A 1.5-mile loop trail around the lake provides a gentle walk with minimal elevation change. A 4-mile out-and-back trail offers more of a workout, while nearby trails like the Lofty Lake Loop or Highline Trail give ambitious hikers multi-lake views or backcountry adventures deeper in the wilderness.

Mirror Lake Campground, with 94 sites, is among the most coveted in the Uintas. Campers fall asleep to the whisper of breezes through the pines and wake to mirror-still water glowing with alpenglow at dawn.

Farther along, Hayden Peak Overlook reveals a jagged, snow-capped summit rising above dense forest. The peak is named for geologist Ferdinand Hayden, whose 19th-century surveys were famously documented by photographer William Henry Jackson. Sunset is especially photogenic, when alpenglow paints the cliffs scarlet.

Hayden Pass is also the western termi-

nus of the Uinta Highline Trail, a long-distance backcountry route that threads the spine of the Uintas.

An optional side road (Forest Road 057) veers off to Christmas Meadows – a large campground and trailhead offering access to more than a dozen miles of wilderness hiking. In early summer, the gravel road may be muddy, but later in the season, wildflowers and Stillwater Fork’s excellent fishing make the detour worthwhile.

Before reaching the Wyoming state line, the Bear River Ranger Station provides a scenic stop with picnic tables and a restored tie-hack cabin that recalls the logging history of the Uintas.

As the byway nears the Wyoming border, it flattens out. From here, travelers can loop back to Utah or continue to Evanston. The road typically opens in late May and closes when snow becomes too deep to plow. Cell service is unreliable, so check conditions before heading out.

Fall travelers will find the route especially dazzling, as aspen and maple leaves ignite in shades of gold and crimson.

The Mirror Lake Scenic Byway is no folk myth. This high-mountain route passes through wild forests, over alpine passes and along shimmering lakes – a tale of real-life magic, told through a car window.

BYWAY

Season: Road typically opens mid-May and closes mid-fall when snow makes plowing impossible. Check UDOT for current conditions.

Fees: Use of the byway is free. Recreation areas in the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest require a pass (3-day, 7-day or annual). Passes available in Kamas, online at yourpassnow.com, at self-service fee tubes and at Forest Service offices.

Gas & Supplies: Last fuel stop is in Kamas. Stock up at the Samak Smokehouse & Country Store or grab coffee and fritters at the Chevron station before heading up the highway.

Camping: Popular spots include Mirror Lake Campground (94 sites) and Christmas Meadows. Reservations recommended in peak season.

Cell Service: Unreliable throughout the byway. Plan ahead and download maps before you go.

Highlights: Bald Mountain Pass (highest paved road in Utah), Upper Provo River Falls, Mirror Lake, Hayden Peak Overlook, Christmas Meadows, Bear River Ranger Station.

UTAH STAKES ITS CLAIM AS THE NATION’S NO. 1 MOUNTAIN STATE

by MATT MASICH

UTAH HAS SO many mountains that even its flat parts have mountains. That would be the Bonneville Salt Flats, where drivers come from around the world to set land speed records on its utterly flat natural speedway. But what do the drivers see when they glance to the northwest? The peaks of the Silver Island Mountains.

Utahns are proud of their state-spanning peaks, from the 13,000-foot summits of the Uinta Range in the northeast, to the Pine Valley Mountains overlooking St. George in the southwest, to the Wasatch Front, home to three-fourths of Utah’s population.

The people here have always felt there is something superlative about Utah’s mountains – but how could they prove they were the best? Kings Peak, the state’s highest summit, is only No. 76 on the list of highest peaks in the United States. As a whole, Utah has one of the highest average elevations of any U.S. state, but it still only ranks No. 3.

Then, in 1992, mountain climber Dub Bludworth of Salt Lake City crunched some numbers to prove that Utah is, indeed, the most thoroughly mountainous state. His data showed that the average elevation of the highest peak in each of Utah’s 29 counties is 11,222 feet above sea level – about 250 feet higher than runner-up Colorado.

Bludworth took his discovery to Lynn Arave, then a reporter at the Deseret News, who published a series of articles touting Utah’s newfound claim to fame. The state’s status as elevation champion to adopt the popular “Life Elevated” slogan, Arave told Utah Life.

But Bludworth didn’t just identify and compile data on Utah’s county high points – he became the first person to climb to the top of each one. Not long after Arave wrote about Bludworth’s feat in the Desert News, a new peak-bagging fever had taken hold among the state’s hiking community. People crisscrossed the state trying to summit each county high point, which

MOUNT TIMPANOGOS, above, has a craggy summit overlooking the lush Emerald Lake Basin, where wildflowers delight hikers. “Timp,” as many of its admirers call this massive mountain outside Provo, is the most-visited peak in Utah.

THE LA SAL MOUNTAINS loom in the distance – the three closely clustered summits at center are La Sal Peak, Mount Waas and Castle Mountain, left to right – while the Colorado River flows past the sandstone formations of Fisher Towers, northeast of Moab.

NOTCH PEAK, top left, rises 4,450 feet in prominence from the floor of the Tule Valley in the West Desert. The sheer cliff on the mountain’s northwest face has an incredible 2,200 vertical rise, making it one of the tallest cliff faces in North America.

MOUNT ELLEN, bottom left, is the highest peak of the Henry Mountains, east of Capitol Reef National Park. In 1894, a U.S. Army Signal Corps station at the summit used mirrors and telescopes to exchange Morse code messages with a station 183 miles away on Mount Uncompahgre in Colorado.

DEVILS CASTLE, above, looks more heavenly than diabolical thanks to a rainbow that arcs above Cecret Lake. The peak at Alta Ski Area is popular with skiers in winter and rock scramblers in summer.

summits. By 1999, there was even a definitive guidebook, High in Utah, devoted solely to telling people the best way to climb them all.

While reporting the story, Arave couldn’t resist trying to bag a few county high points himself, though he quit after climbing only 11. He soured on the idea of climbing peaks just to rack up numbers after he was nearly zapped in a lightning storm while trying to bag the state’s three highest peaks in a single day – he was so obsessed with bagging them all that he didn’t notice the ominous clouds rolling in over the Uinta Range.

Instead, he decided to focus on climbing peaks whose individual stories spoke to him. One of the first on his personal list was Ben Lomond, which rises high above Ogden in the Northern Wasatch Range.

Millions of people know Ben Lomond by sight, if not by name: It was the model for the iconic Paramount Pictures peak, first sketched in 1914 by studio co-founder W.W. Hodkinson.

“He grew up in Ogden, and if you go there, Ben Lomond is just larger than life,” Arave said. “It looms a mile above the level valley, so as a young kid, that had to leave a big impression on him.”

son climbed Notch Peak, which has a sheer cliff on its northwest face plunging 2,200 feet straight down from the summit. He took in the spectacular view from the top, but he might have spent just as much time watching his son, then 9 years old, to make sure he didn’t fall over the edge.

No Utah mountain list would be complete without Mount Timpanogos, the most-hiked peak in the state. With waterfalls, wildflowers galore and a Matterhornlike summit looking down on Provo, “Timp” has it all. Perhaps that’s why at least one Utahn has shrugged off the idea of bagging a bunch of peaks in favor of bagging Timp over and over again.

Ben Woolsey of Orem first summited Timp when he was 24. He made his 190th ascent around his 50th birthday, but he didn’t really get going until he retired at age 62. Woolsey was 75 when he completed his 900th climb, aiming to reach the summit an even 1,000 times.

Few of Woolsey’s fellow hikers find anything odd about his devotion to Timp –he’s simply doing what they wish they could do. And that might speak more to the superlative grandeur of Utah’s mountains than any statistics ever could.

THE TUSHAR MOUNTAINS, above, with snowcapped Mount Baldy, left, and Mount Belknap, right, lie on the dividing line between the Great Basin and the Colorado Plateau. The Tushars are the highest mountain range in southwest Utah and third-highest in the state.

SUNDIAL PEAK, right, pokes jaggedly skyward in Big Cottonwood Canyon, just southeast of Salt Lake City. The hike to Lake Blanche, at the mountain’s base, is one of the most popular and picturesque routes in the Wasatch Range.

recipes

and photographs by

DANELLE McCOLLUM

There are few foods that aren’t improved by adding bacon – especially when it comes to appetizers. Whether you’re having a party or simply need something to snack on while watching the big game, you can’t go wrong with these baconized apps.

Cherry tomatoes are stuffed with a mixture of crispy bacon, mayonnaise, fresh veggies and Parmesan cheese in these adorable little appetizers. For scooping out the tomatoes, small measuring spoons work well. Don’t skip the step where you allow the tomatoes to drain on paper towels. If you’d like your tomatoes to stand up on the serving platter, slice a very tiny bit off the bottom so they sit flat.

Cut thin slice off top of each tomato. Scoop out the pulp and discard. Invert tomatoes onto paper towel and allow to drain for about 30 minutes. Meanwhile, in medium bowl, combine bacon, mayonnaise, Parmesan cheese, red pepper, green onion, parsley and salt and pepper. Generously stuff each tomato with bacon filling. Cover and refrigerate for at least one hour – and up to three hours – before serving.

2 10-oz packages cherr y tomatoes

6 slices bacon, cooked crisp and crumbled

1/2 cup mayonnaise

1/4 cup Parmesan cheese

1/4 cup finely diced red pepper

2 green onions, chopped

1-2 Tbsp chopped fresh parsley

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 12-14

Miniature crusts are filled with a mixture of bacon, tomatoes, basil and Swiss cheese in these simple and delicious appetizers. These can be made ahead, frozen, then reheated. Mozzarella and Monterrey jack cheese can be used instead of Swiss.

Fry bacon until crisp; drain on paper towels and crumble into medium bowl. Cut biscuits into quarters. Press each biscuit piece into one section of lightly greased mini muffin tin to form a cup. Add chopped tomato, green onion, cheese, mayonnaise and basil to bacon and mix well. Season with salt and pepper, to taste. Divide bacon and tomato mixture evenly among the muffin cups. Bake at 375° for 10-12 minutes, or until heated through and golden brown.

10 slices bacon

3 Roma tomatoes, chopped

2 green onions, chopped

6 oz shredded Swiss cheese

1/3 cup mayonnaise

1/2 tsp dried basil

1 16-oz can Pillsbur y Grands biscuits or similar

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 18-24

This hot, cheesy dip is loaded with green chiles, bacon and chorizo for an over-the-top appetizer or game-day snack. The queso dip can be made in a skillet and served right from the pan, but it also can be transferred to a slow cooker to keep warm.

In large skillet over medium heat, cook bacon until crisp. Remove from pan and drain on paper towels. Set aside. Add chorizo to skillet, along with onions and garlic, and cook until no longer pink, breaking up as you cook. Drain grease from chorizo and set aside with bacon. Wipe out skillet.

Add diced tomatoes, green chiles and Velveeta to skillet and cook until cheese is melted. Stir in shredded pepper jack cheese and evaporated milk and continue to cook and stir until cheese is completely melted and smooth. Return bacon and chorizo to skillet and stir to combine. Stir in cilantro and serve hot with tortilla chips.

6-8 slices bacon

8 oz chorizo

1 small onion, diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 10-oz can diced tomatoes and green chiles

1 4-oz can diced green chiles

1 lb Velveeta cheese, cubed

2 cups shredded pepper jack or Monterey Jack cheese

1 12-oz can evaporated milk

1-2 Tbsp chopped fresh cilantro Tortilla chips, for serving

Ser ves 8-10

What’s in Your Recipe Box? The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@utahlifemag.com.

When summer settles on the desert, it leaves its mark – in the way the days stretch long, the sandstone radiates warmth into the night and streams are sought for a cool reprieve.

Through the heat’s rippling waves and flickering mirages, our poets capture its intensity, illusions and the resilient spirit of the land.

Lorraine Jeffery, Orem

Hailey Edmonds, Mapleton

my summer of relentless thought perched on nostalgia hill magnolia trees mark the spot my curves shifting with the season feels like a force without rhyme or reason

my body will simply wither away as for summer she always remains here to stay

Dry leathery roots probe barren rock cracks for tomorrow.

Branches amputated by wild-blasted sand as gray-green mesquite leans south braced to do battle.

Gauntlet is thrown down, as gnarled knight jousts once again with dragon-breathed summer.

William Kofoed, Magna

In the spring of young boy dreams of summer days so soon to come

that they might build for their own for them to use in bright sunshine

wood they gather to shape and form to match the lines of springtime dreams and canvas buy and stretched tight and to paint in colors bright and paddles get and cut and form to make the one that they will need and on summer days on mountain lakes their boat to launch in sunlight bright

Summers

Jim Garman, Richfield

Hot Utah Summers can turn you a crispy red in our west desert

Summers

Garry

Glidden, Saint George

The sun rises hard over redrock, heat spilling fast across the desert floor. Sidewalks shimmer, trails dust up beneath boot and bike, while cacti bloom like fireworks –bold, brief, and defiant.

Pickleball paddles crack in the morning haze, kids cannonball into blue-lit pools, and anglers stand still at mirror lakes, lines drawn into silence.

Hikers climb through heat and shadow, past blooms clinging to stone, while alpine air waits, cooler, cleaner, where snow still hides in crests above.

Evening glows long on canyon walls. Campfires flicker. Stars arrive without apology, sharp and infinite.

Utah in summer: a place of sweat and sky, stillness and grit, where everything burns bright, then rests in the wind.

Send your poems on the theme “Where We Began” for the January/ February 2026 issue, deadline Nov. 1 and “The Thaw” for the March/April 2026 issue, deadline Jan. 1. Email your poems to poetry@utahlifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Longtime melon-growing families chop up slices of crisp watermelon with the precision of a Samurai. Behind them, truck beds overflow with ripe fruit as thousands of locals and visitors flock to taste Green River’s sweet claim to fame. For 119 years the town has celebrated Melon Days, honoring the region’s world-famous harvest.

Green River’s sandy soil and desert climate produce especially sweet melons. The festival has occurred every year since 1906, but the town wasn’t always famous for melons. Peaches once led the region’s exports, thanks to J. H. “Melon” Brown. When a deep freeze killed most of the peach trees in 1919, farmers adapted and turned to cantaloupes instead.

Today, the Dunham, Thayne and Vetere families carry on the legacy, trucking in loads of free samples that showcase Brown’s sweet success.

Festivities begin Friday evening with a

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Melon Carving Party at 7 p.m. at the Epicenter building. Kids and kids-at-heart turn watermelons into works of art, with every carving entered into Saturday’s contest for a chance to win $100.

O.K. Anderson Park on Solomon Street hosts most of the fun, from pony and unicorn rides to a softball tournament, vendor fair and free melon sampling. Live music runs noon to 7 p.m., featuring the father-son Generations Band, Lehi-based FunkRockPop cover band Monkey Friday, and the Fox Brothers.

Saturday’s parade kicks off at 10 a.m. with floats, marching bands and candy-tossing locals. If you’re lucky, you’ll spot the town’s beloved celebrity – a giant watermelon on wheels.

Each September, Green River shows that its roots run deep and its melons run sweeter, keeping a 119-year tradition deliciously alive. melon-days.com, (435) 820-0592.

This riverside spot serves American fare for breakfast, lunch and dinner. The giant cinnamon rolls, smothered in cream cheese frosting, are a favorite. 1710 E. Main St. (435) 564-8109.

Built in 1950 as Green River’s first motel, this bed and breakfast offers comfortable accommodations, a tranquil campfire pit and homemade breakfast each morning. 20 W. Main St. (435) 564-7625.

For 119 years, Green River has celebrated its worldfamous harvest with Melon Days.

The Bluff Arts Festival kicks off on Oct. 16 with a sunset storytelling event. At the Recapture Lodge, local authors share published and in-progress writings.

Every third weekend of October, the Bluff Arts Festival transforms this small Four Corners town into a vibrant hub of creativity. Against a backdrop of crimson cliffs and golden cottonwoods, artists and locals gather for three days of workshops, performances and shared inspiration.

The weekend begins on Thursday with sunset storytelling. Friday, there are handson workshops led by regional artists, including astrophotography, clay shaping, weaving and jewelry-making. The new Art Walk invites visitors into galleries, trading posts and studios downtown.

That evening, a free outdoor Film Festival lights up the Bluff Community Center parking lot with regional stories from 6:3010 p.m. Saturday brings the bustling Artist Market from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., where booths overflow with ceramics, paintings and jewelry, each echoing the spirit of the Southwest.

By Sunday, creativity spills into every corner of town with more workshops, leaving Bluff glowing with inspiration until next year’s golden October light. bluffartsfestival.org.

Mouthwatering barbecue permeates Main Street at this smokehouse. Pair brisket, pulled pork, Cajun sausage, ribs or chicken with five house-made sauces. 281 E. Main St. (435) 269-0400.

Cradled between red rock bluffs, this resort offers a variety of lodging. Stay in the cozy lodge, courtyard rooms or wood-paneled cabins. 701 W. Main St. (435) 672-2303.

Peach Days

Sept. 3-6 • Brigham City

A beloved tradition for more than a century, Peach Days celebrates Brigham City’s agricultural roots – especially its peaches. Wednesday kicks off with the Junior Peach Queen Pageant and a melodrama, followed Thursday by a downtown fruit display and more than 200 vendors. Saturday features a full day of activities, a parade, free concert and the state’s largest free car show. (435) 723-3931.

Old Capitol Arts & Living History Festival

Sept. 5-6 • Fillmore

Built as Utah’s first state capitol, the Territorial Statehouse now hosts this 20-yearold festival. Living history reenactors mingle with visitors as horse-drawn wagons pass by. Fifty artists and artisans sell their wares, while the local quilt guild showcases a colorful display. 50 W. Capitol St. (435) 743-5316.

Cedar City Half Marathon and Adventure 5K

Sept. 6 • Cedar City

It’s all downhill at the 16th annual races through Cedar Canyon. The half marathon drops 13.1 miles from 8,400 feet to 5,600 feet, following Coal Creek’s twists

1 Pony Express 2 Scenic Byway 12 3 Bicycle 4 Moab

5 Big Rock Candy Mountain

6 b. Utah, by 3 miles over Montana

7 b. Private toll road

8 a. Logan Canyon

9 a. Delta, pop. 3,500 10 c. Andrew Johnson

False. Some Salt Lake City streets were paved in 1891.

and turns before finishing at Bicentennial Soccer Complex. 105 N. 100 East. (435) 865-5108.

Festa Italiana SLC

Sept. 13-14 • Salt Lake City

Downtown Salt Lake transforms into Little Italy during this free two-day festival. Food booths serve authentic Italian cuisine, while exotic cars, a beer and wine garden, and live entertainment fill the streets. Proceeds benefit local and national nonprofits. 18 N. Rio Grande St. (801) 214-1629.

Center Street Giant Pumpkin Festival

Sept. 27 • Logan

Giant gourds and 20,000 visitors take over Historic Center Street at this 3rd annual festival. Last year’s weigh-off set a Utah record at 2,289 pounds. Other fun includes pumpkin decorating, Pin the Pumpkin, cornhole and the Mile Vine Pumpkin Run. (435) 755-1890.

Sandy City Heritage Festival

Sept. 27 • Sandy

The day begins with a 10 a.m. parade, then continues at Main Street Park with food, vendors, live music, bounce houses, face painting and a community celebration. 90 E. 8720 South. (801) 568-7100.

Park City Wine Festival

Oct. 2-4 • Park City

Uncork a weekend of fine wines from more than 100 local, national and international wineries. The Grand Tasting at Canyons Village features over 200 wines, small bites from 10 restaurants and craft cocktails. Wine hikes, seminars and paired meals round out the weekend. (303) 777-6887.

Spooky Season Kickoff

Oct. 4 • Syracuse

Come in costume for ghost tours and ghost stories at Fielding Garr Ranch on Antelope Island State Park. The evening ends with treats for ghouls and goblins alike. 4528 W. 1700 South. (801) 538-7220.

The Importance of Being Earnest

Thru Oct. 4 • Cedar City

The Utah Shakespeare Festival closes its season with Oscar Wilde’s satirical comedy on Victorian society. Catch the final performances at the Randall L. Jones Theatre. 35 S. 300 West. (800) 752-9849.

Honey Harvest Festival

Oct. 10-11 • Grantsville

Sweet as honey – and full of it – this 12th annual festival at Clark Historic Farm features beekeeping demos, pony and camel rides, bounce houses, contests, the crowning of Honorary Queen Bees and the Sweet Fiddlin’ Fest. 392 W. Clark St. (801) 971-0842.

Snowbird’s Oktoberfest

Thru Oct. 12 • Snowbird

Snowbird’s slopes turn Bavarian every fall with Oktoberfest. From noon to 6 p.m. each Saturday and Sunday, enjoy more than 50 beers, traditional fare, live music and family activities. 9385 S. Snowbird Center Dr.

Oct. 15 • Salt Lake City

Sip spooky concoctions and admire glowing lights while learning about nocturnal animals at the Hogle Zoo. Educational chats run from 6:30-9:30 p.m. 2600 Sunnyside Ave. South. (801) 584-1700.

Oct. 25 • Pleasant Grove

It’s the only day of the year where smashing pumpkins is encouraged. Pumpkins large and small are dropped from 14 stories high, aiming at targets like a swimming pool, office furniture and a car. Pumpkins drop from 12-5 p.m at Hee Haw Farms. 150 S. 2000 West, North County Blvd. (801) 368-0255.

Oct. 27 • Murray

Bring your pup for a Halloween outing at Wheeler Historic Farm. Tickets ($17) include Pumpkin Days admission, a trick-or-treat bag and wagon rides. Dogs can test their skills in the straw bale maze, with more treats along Vendor Alley. 6351 S. 900 East. (385) 468-1755.

story by KERRY SOPER illustration by JOSH TALBOT

UUtahns adore water, even if it leaves us bruised, humbled and occasionally pants-less.

TAHNS LOVE WATER. When you live with a chronic lack of moisture, you maximize the moments you get – and sometimes lose your head the second you’re near a hose, pool or reservoir. Speaking for myself, the results have been … educational.

As a kid I dreamed of belonging to one of those cool boating families that camp at the reservoir every weekend. We were not that. We were a lower-middle-class crew with a tippy canoe, complicated fishing gear and enough envy to swamp a dock. So, I waited for invitations from wealthy neighbors, imagining 15 minutes of glory behind a ski boat.

The reality was always the same: I’d stew in an oversized life jacket at the stern while nausea did slow circles. When it was my turn, a lack of athletic ability and experience always let me down, though. With everyone watching, I would struggle to get

up on the skis, and my inevitable crash was always severe enough to both entertain the crowd and end my day: a gallon of water up the nose, a vaguely dislocated shoulder, or a wrenched back.

My masterpiece wipeout came in my mid-30s at a youth outing for my local church. Another leader figured it would be hilarious to tow me at a speed just past reasonable. Stubbornness kept me upright long enough to hit another boat’s wake and pinwheel out of my skis – arms and legs everywhere for a good 20 feet. I struck the water hard enough that my swim trunks –loosely secured above a famously flat rear – shot off into the deep. When the boat circled back, the lake’s dark water did its best to protect my reputation. My teenage son later reported the crowd still caught flashes of pale derriere as I bobbed like a buoyant seal, diving repeatedly, trying to retrieve my slow-sinking trunks.

Long before that, Lagoon’s old pool taught me a different lesson. One glorious summer in 1979, my parents bought season passes. The centerpiece was a towering metal slide – a Great Depression relic with 30 open-air rungs and a sign that said no swimmers under 12. I was 12. But what to do about my chunky, 5-year-old little brother, since I had to watch him? My solution was to ignore the rule and encourage him to follow me up the slippery rungs.

The reason for the rule became painfully clear when we got two steps from the top and his arms gave out. He fell backward and took a baker’s dozen of strangers with him, a human Jenga that splashed spectacularly into the pool. I’m not proud of what I did next: I pretended I didn’t know that sad little kid who had just created carnage below. I was too dang close to the top.

In my 40s I discovered the public pool in Orem has a slide perfectly calibrated to

my dad-bod aerodynamics – some mysterious blend of tubular torso and minimal ballast. If I launched just right, I’d skim across the surface like a skipping stone and throw a glorious rooster tail. Kids I didn’t know would gather at the rail and chant for an encore. My own kids maintained the family tradition – they claimed not to know me.

A scout camp later offered the most ambitious slide of all: a sheet-plastic luge down a steep hill, fed by fire hoses. Older teens sprinted, dove headfirst and rocketed to the bottom. Leaders my age earned jeers for scooting down on our backsides. Wanting to be cool – but also to keep my trunks on – I decided to sprint, leap and land on that hydrodynamic rear, then ride the water like a champion. Instead, I hit a slick patch, launched backward, rotated upside

down and drilled the ground with the top of my head.

Witnesses said my arms and legs went full ragdoll as I shot downhill. I woke up at the bottom asking the only question that mattered: “Did I get any cheers?” My son said there were a few – mostly laughter. Years later the camp still used my concussion as a cautionary tale.

AUTHOR Kerry Soper writes and teaches satire, humor and history from Provo.

Eventually I talked my wife into an above-ground pool. Our young-adult children called it embarrassing, and the chemistry – heat, pH, endless leaf skimming –owned my weekends. In the final weeks before we sold it, the only swimmer was me, floating alone in green-tinged water like a dejected manatee.

Last year we became paddle-board people – in our 50s, not our 20s. At Tibble Fork Reservoir I tried to stand with digni-

ty, failed with enthusiasm and learned that the full-body twerk is not a recognized paddle sport. Each attempt ended the same way – a sidelong flail, a clean splash and applause I did not request.

We also bought the grandkids an inflatable bouncy house with a water slide and a kiddie pool. Occasionally – on quiet weekday afternoons when the neighbors are away – I set it up for “testing.” The safety label says the slide supports riders under 100 pounds. There’s wisdom in that rule. There’s also a hose, a slope and a man who keeps relearning the same lesson every summer.

So yes, Utahns adore water – which is how I keep finding myself on ladders, slides and boats I should treat with more respect. The next time I chase the splash at Lagoon, Orem or Tibble Fork, I have a simple goal. I plan to come home with the same number of teeth, the same number of brain cells and – most importantly – the same pair of trunks.