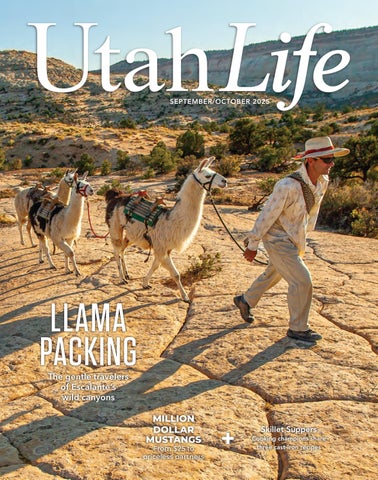

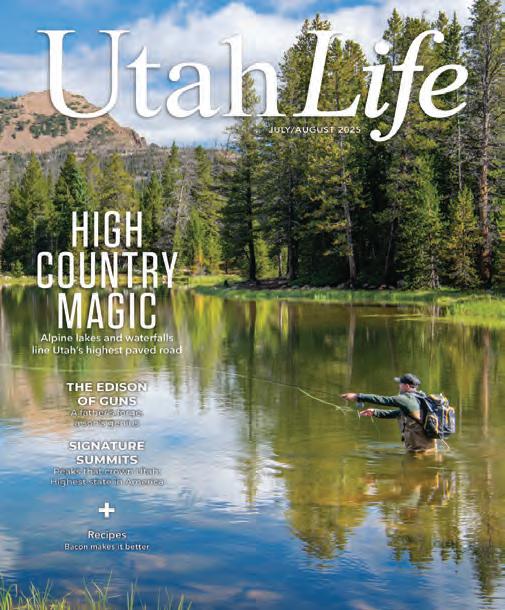

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025

The gentle travelers of Escalante’s wild canyons

MILLION DOLLAR

MUSTANGS

From $25 to priceless partners

Skillet Suppers

Cooking champions share three cast-iron recipes

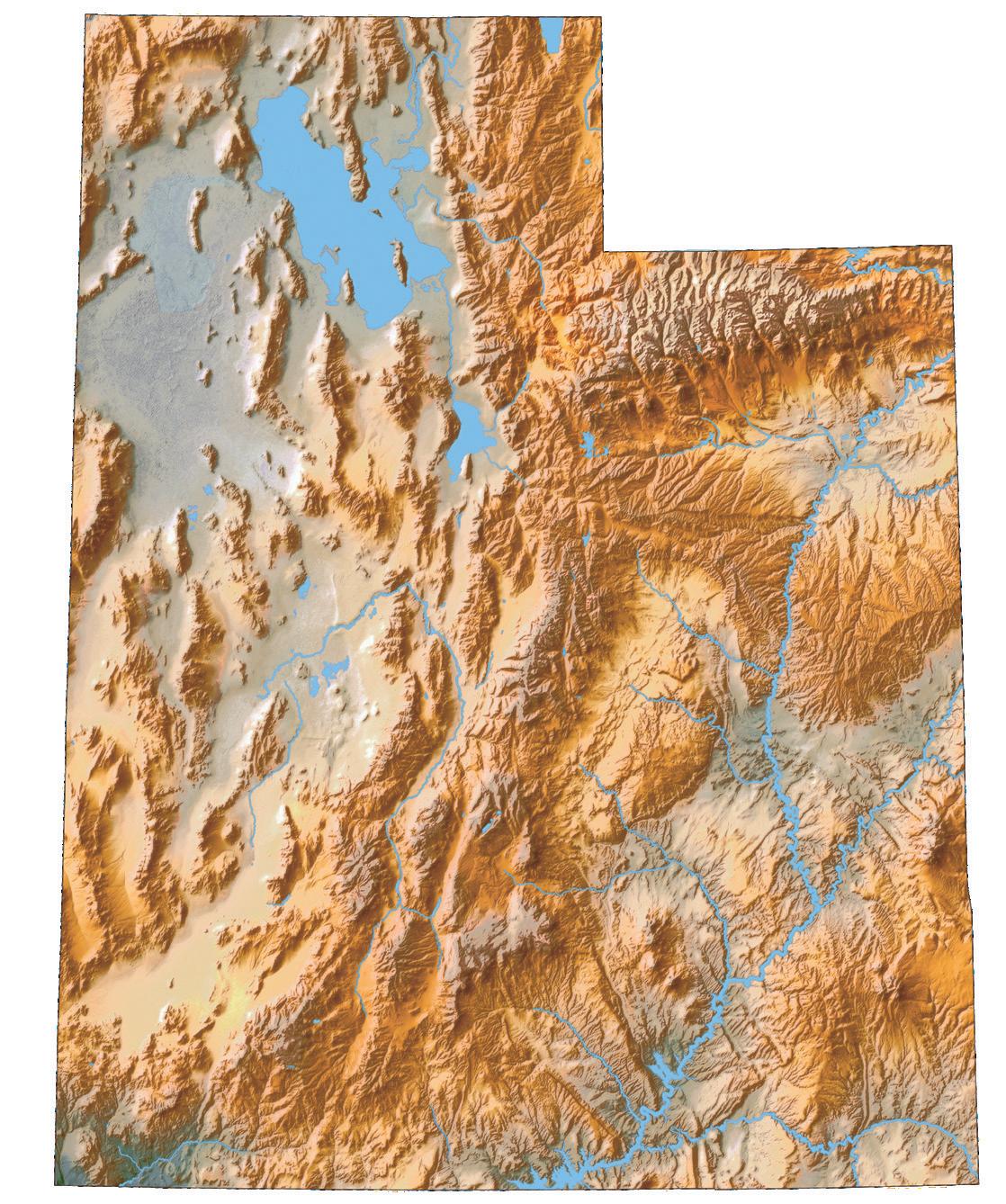

Midway, pg. 20

Riverton, pg. 12

Lehi, pg. 39

Heber City, pg. 8

Price, pg. 26

Green River, pg. 38

Moab, pg. 42

Boulder, pg. 6

Blanding, pg. 16

Montezuma Creek, pg. 34

A string of pack llamas and guests travel off-trail in the Grand Staircase-Escalante

National Monument, exploring a remote area of Utah’s backcountry. Story begins on page 6.

Photo by Ryan Salm.

5 Editor’s Letter Obser vations from Chris Amundson.

6 Honeycomb

Llama packing in Grand Staircase; Kokanee salmon spawn each fall.

10 Trivia

Test your farm smarts, without the corny questions. Answers on page 40.

26 Uncommon Champions

Dutch oven mastery and inspiration with Bill and Toni Thayn.

28 Kitchens

Supper straight from the cast iron.

32 Poetry

Verse shaped by the land.

38 Explore Utah Boots and guns for Outlaw Days; Lights dazzle at Luminaria.

46 Last Laugh

The woes of wildlife bites, fumbles and hilarious interruptions on unsuspecting humans.

12 Million Dollar Mustangs

The story of two wild mustangs and their journey from freedom to forging trust. by Bridger Park

16

Life on the Edge

Edge of Cedars Museum in Blanding brings history to life with ancestral Puebloan artifacts. story and photographs by Dan Leeth

20

Blessed Are the Cheesemakers

From family dairy to award-winning cheese. story by Jacque Garcia photographs by Kelli Freshman

34

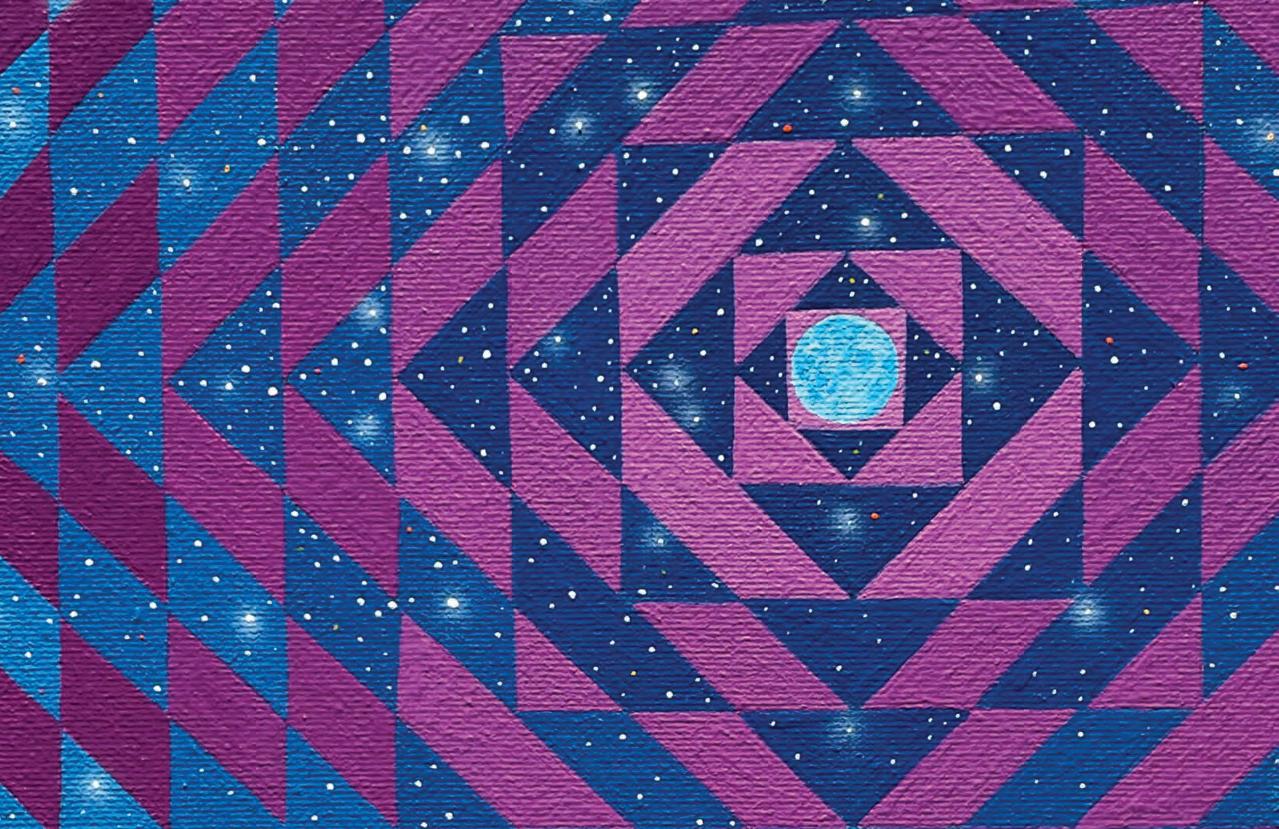

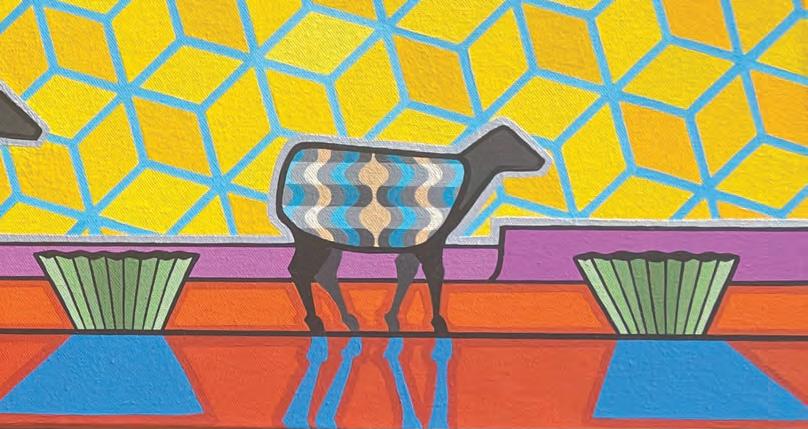

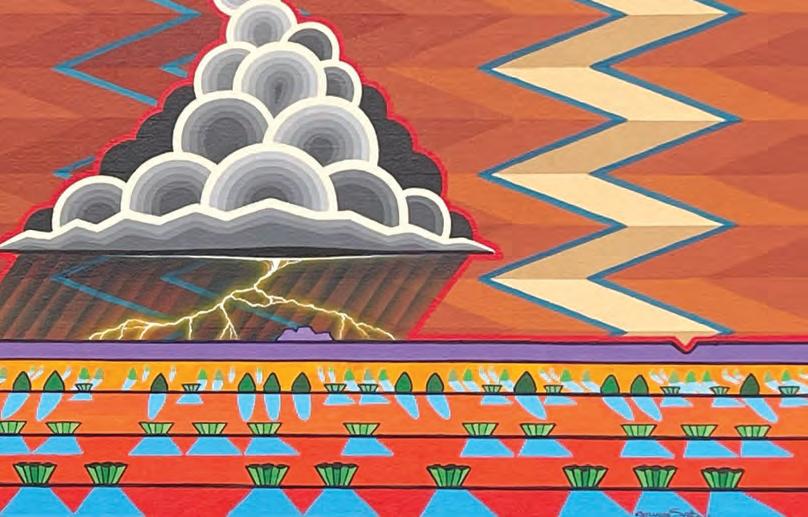

Woven in Color

Diné artist Gilmore Scott weaves culture into vibrant, geometric paintings of Bears Ears. by Ariella Nardizzi

42

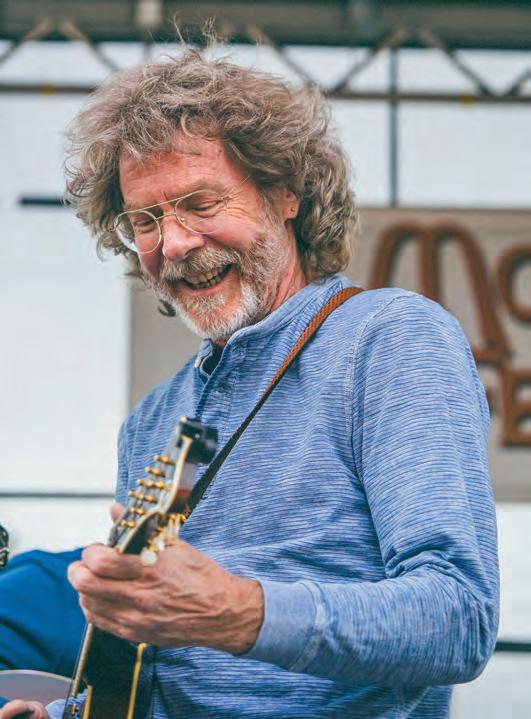

Moab Folk Festival

Moab Folk Festival turns a baseball diamond into a stage for bluegrass magic. story by Peter Moore photographs by Max Haimowitz

YOU CAN TELL a lot about Utah by its caretakers. Some lead llamas and guests through slot canyons, leaving no trace where every footprint matters. Others haul ladders into thousand-year-old kivas, brush dust from pottery that tells stories older than the state itself, or count salmon eggs to ensure the next generation of fish can find its way upstream.

As publisher, I’ve come to see editing a magazine as its own act of stewardship. We don’t mend trails or cradle pottery shards, but we try to carry Utah’s stories with care so they endure for readers today and those who come after.

That lesson comes into focus when you step onto a trail behind a string of llamas in Grand Staircase-Escalante. BJ Orozco and his company Llama2boot know these animals aren’t just quirky companions but teachers in light-footed travel, as described in “No Drama, Just Llamas.” They carry what we cannot, leaving barely an imprint behind.

A similar rhythm unfolds each autumn in “Scarlet Streams,” when kokanee salmon surge through the Wasatch and Uintas. Their blaze of red depends on careful management from scientists and anglers. Without it, the cycle falters. With it, streams pulse with life year after year. Stewardship also takes grit when wildness and human will collide. In “Million Dollar Mustangs,” horses shaped by the open range find themselves on new paths of rescue – a controversial endeavor that asks hard questions about our responsibility to creatures who symbolize both freedom and fragility.

“Life on the Edge” opens a window into the Four Corners at Edge of the Cedars Museum, where pottery, tools and a thousand-year-old kiva have been preserved with care. Deep under the earth, “Guardians of the Underground” shows volunteers at Timpanogos Cave scrubbing stalactites clean so they last another millennium.

The same balance lives in the hands of Diné artist Gilmore Scott. His canvases come alive with the colors of Bears Ears, weaving together shadows learned from firefighting, patterns passed down from his mother’s loom and the matriarchal lessons of his culture. “Woven in Color” is stewardship in another form, ensuring stories endure as vividly as the land itself.

Taken together, each story asks us to see Utah as more than a backdrop. It encourages us to treat the land as a living trust – to step lighter and look deeper.

Like the kokanee fighting upstream, stewardship is never finished. It’s a cycle we join, season after season, so the waters run red with life for generations to come.

CHRIS AMUNDSON Publisher & Editor editor@utahlifemag.com

September/October 2025

Volume 8, Number 5

Publisher & Editor Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher Angela Amundson

Photo Coordinator Erik Makić

Staff Writer Ariella Nardizzi

Design

Mark Del Rosario Michelle Halcomb

Editorial Assistant Savannah Dagupion

Advertising Sales Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Shiela Camay

Utah Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130

Fort Collins, CO 80527 (801) 921-4585

UtahLifeMag.com

Subscriptions are $30 for 6 issues and $52 for 12 issues. To subscribe and renew, visit UtahLifeMag.com or call (801) 921-4585. For group subscription rates, call or email publisher@utahlifemag.com.

Send us your letters to the editor, story and photo submissions, story tips, recipes and poems to editor@utahlifemag.com, or visit UtahLifeMag.com/contribute.

ADVERTISE

For rates, deadlines and position availability, call or email advertising@utahlifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork is copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@utahlifemag.com.

In Escalante’s canyons, sure-footed pack animals carry the load and open the way to Utah’s wildest desert.

story by ARIELLA NARDIZZI photographs by RYAN SALM

Towering canyon walls catch the last orange light of evening, glowing like embers above the Escalante River as a line of soft-footed pack animals pads quietly through the sand. Alongside them, hikers move at an easy pace, carrying little and letting the desert reveal itself one step at a time.

For 15 years, Boulder-based Llama2boot has led travelers through some of the most secluded corners of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Glen Canyon. Founder and guide BJ Orozco has spent nearly 25 years with llamas in these red rock canyons, first as a young hand training them, then building his own company.

Since then, Llama2boot has guided more than 100 full-service trips, logging over 500 days in the backcountry. From the Escalante River’s high headwaters to

its confluence with Lake Powell, Orozco rotates among 15 routes, allowing the land time to rest between use.

Each journey feels new: one day crosses slickrock benches, the next winds through cottonwood-lined corridors, the next squeezes through slot canyons where sunlight barely filters down. Often there is no trail at all – only experienced, medically trained guides and their sure-footed animals.

The llamas make this off-trail travel possible. Native to the high Andes, they are perfectly suited for Boulder’s elevated plateaus. With padded feet more akin to a dog’s than a horse’s, they tread lightly, leaving little trace.

Each carries up to 65 pounds of gear, so guests shoulder just 10 pounds or less. That means fresh food, comfortable tents, and the freedom to look up at the cliffs instead of down at the ground.

Trips range from half-day walks to multi-

day treks, with small groups and guides handling the meals, camp and logistics.

“As guides, we offer knowledge that can’t always be replicated,” Orozco said. “There are artifacts, rock art panels, and unique formations people might otherwise miss. We slow down and notice.”

Half the guests come for the desert. The other half come for the llamas – and many leave bonded to their animal. “People get possessive of their llamas really quickly,” Orozco laughed. “When we assign guests their animal on day one, there’s no trading. They feed them, tend to them, and develop those bonds fast.”

His herd of 12 brims with personality. Guan, the old man, is gentle and steady; if a hiker lags behind, he’ll wait to guide them into camp. Roy, a strong packer, is the only llama Orozco has ever owned that spits unprovoked – his wild streak keeps him at the front of the line, handled only by Orozco. Montana, now retired, was once the company’s all-star: a big-bodied leader who trusted Orozco implicitly and inspired trust in the rest of the herd.

Though llamas are known for spitting and aloofness, Orozco says his herd minds its manners and thrives alongside guests and handlers in Utah’s desert.“In the pasture llamas can be shy. On the pack string, they’re locked into the job. They respect every guest.”

Because midsummer heat is too much for their woolly coats, trips run only in spring and fall. On the trail, the llamas browse on cottonwood leaves and pine needles while hikers learn to read the language of slickrock, water and canyon light.

Soon, Orozco will hand the business to guides he has trained, keeping the herd and tradition rooted in Boulder. For him, it’s another step in a long journey of moving across this fragile landscape with care.

Llamas are well suited to desert travel. They need only a few gallons of water a day, and their padded feet spread weight like a hiker’s, leaving fragile soil crusts and narrow trails largely undisturbed. Their prints fade with the morning wind – but for the people who walk beside them, the imprint endures.

Kokanee salmon surge through Utah waters in a dramatic fall spawning ritual

by TIM GURRISTER

Each fall, Utah’s mountain streams come alive with a flash of scarlet. Kokanee salmon, silver for most of their lives while schooling deep in reservoirs, transform into brilliant crimson as they fight their way upstream against a backdrop of golden aspens and cool alpine air. Salmon runs are often thought of as the domain of Alaska or the Pacific Northwest, but Utahns have their own version. Kokanee are landlocked sockeye, introduced to Utah in the mid-20th century to provide both a sport fishery and forage for

larger trout. In the decades since, they’ve become part of the state’s autumn rhythm – as much a marker of the season as bugling elk or mountain maples.

The name kokanee comes from the Okanagan language of British Columbia, where it means “red fish” – a fitting description for the dazzling display that now plays out across Utah each fall. Hundreds of thousands of kokanee surge into the state’s reservoirs and tributaries in a brief, spectacular and final journey – a mass migration that ends in death for the fish but ensures new life in mountain waters come spring.

From here, the drama unfolds. Males develop humped backs, hooked jaws and elongated teeth – weapons for competing with rivals. Pairs clear gravel nests called redds, where females lay eggs and males fertilize them before covering the site with stone. In their upstream push – sometimes 20 miles against the current – the fish stop eating, driven only by instinct and the memory of the chemical signature of the

stream where they hatched.

At Strawberry Reservoir, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) built viewing platforms and a hatchery facility to showcase the run. “It’s pretty much all instinct,” said Alan Ward, manager of the Strawberry Project. “There’s memory involved too – the smell, a chemical signature unique to every stream, and that’s imprinted when they hatch.”

Unlike their Pacific cousins leaping waterfalls with bears waiting above, kokanee in Utah follow quieter tributaries. Still, the spectacle is compelling. Crowds gather along Sheep Creek at Flaming Gorge or the visitor center at Strawberry to watch the streams blaze with color. “We do have people ask, ‘Where are the bears?’” said Scott Root, DWR outreach manager. “But here it’s about the fish themselves.”

The runs are fleeting and fragile. From Sept. 10-Nov. 30, it’s illegal to keep kokanee anywhere in Utah, to protect spawning fish. Visitors are urged not to wade into streams or let dogs chase them. Disturbing

the salmon can cut short the cycle that sustains future generations.

Biologists also step in to help. Each fall, DWR staff collect eggs and milt from thousands of fish, boosting survival from about 10 percent in the wild to 80 percent in hatcheries. In 2024, more than 2.4 million eggs were gathered statewide, most from Strawberry. By spring, the fry – tiny fish just a few inches long – are released into reservoirs across Utah, ensuring healthy populations for the next generation of anglers and wildlife watchers.

For the kokanee, the spawning run is both triumph and end. Females die within days of laying their eggs. Males linger briefly, then also succumb. Their bodies return nutrients to the streams, feeding insects and enriching the ecosystem their young will inherit.

By the time winter snows settle over the Wasatch and Uintas, the scarlet schools are gone, leaving only buried eggs in the gravel and the memory of Utah’s brief, brilliant salmon season.

Strawberry Reservoir (Wasatch County): View fish at the DWR trap and egg-taking facility behind the U.S. Forest Service visitor center on U.S. 40. Hundreds of crimson fish visible; new mural this fall.

Fish Lake (Sevier County): Salmon run up Twin Creeks northeast of Fish Lake Lodge. Parking at Twin Creeks picnic area along Route 25.

Jordanelle Reservoir/Provo River (Summit County): Rock Cliff recreation area on the reservoir’s east tip. Trails and a bridge provide close views. Best viewing mid-September.

Causey Reservoir (Weber County): Runs in the South Fork of the Ogden River. Reach by paddleboard, kayak or a 2.5-mile hike from Skullcrack Canyon.

Porcupine Reservoir (Cache County): Salmon stack up below the dam, where they’re visible from shore or the bridge. Peak viewing late September into early October.

Stateline Reservoir (Summit County): Just inside Utah’s border with Wyoming. Salmon crowd the east fork of Smith’s Fork – smaller fish, but abundant.

Electric Lake (Emery County): Runs up Boulger and Upper Huntington creeks, early September through October. Visible from pull-offs near the lake’s north end.

Sheep Creek/Flaming Gorge (Daggett County): Utah’s largest kokanee run. Best viewing from the Highway 44 bridge or the trail along Sheep Creek.

SPECIES: Landlocked sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka).

SIZE: 12-18 inches, 1-2 pounds – a few reach 20+ inches, 3-4 pounds in Flaming Gorge.

DIET: Primarily zooplankton, with some insects and small fish.

LIFESPAN: 3-4 years. Spawn once, then die.

SPAWNING SEASON:

with your Circle of Friends

Test your knowledge of the crops that make their way from farm (to festival) to table by

BRIAN WANGSGARD

1 What is the mascot of Jordan High School, whose students were dismissed during the school’s early days to help with the fall harvest of sugar beets?

2 Washington, in Southern Utah, was founded by early pioneers to grow what fluffy crop?

3 Idaho may be famous for potatoes, but Utah is known for what cheesy potato dish associated with somber occasions?

4 The fiber-rich fruit of what thorny plant found in desert areas of Utah can be made into jams and jellies that are high in vitamins, minerals and antioxidants?

5 It’s not a Star Trek convention but the annual Cornfest brings crowds to what southwestern Utah town?

TRUE OR FALSE

11 In 2017, Matt McConkie of Mountain Green grew a pumpkin weighing 1,974 pounds, the largest ever grown in the United States.

12 Garland, a small community in Box Elder County, holds the only annual harvest celebration honoring two crops.

13

6

7

What is Utah’s highest-yielding agricultural crop?

a. Hay

b. Wheat

c. Potatoes

In 1999, what southern Utah city revived its harvest festival to celebrate the same juicy fruit Brigham City has celebrated annually since 1904?

a. La Verkin

b. Springdale

c. Hurricane

8

Famously delicious Bear Lake raspberry shakes almost became just a memory in the early 2000s when the valley’s berry plants were attacked by what?

a. Severe frost

b. Drought

c. Virus

9

Utah has towns named Fruit Heights and Vineyard, but what is the only town with a specific fruit in its name?

a. Cherry Hills

b. Apple Valley

c. Prunedale

10

To what eastern Utah town do you go to enjoy delicious melons and the festival celebrating them?

a. Vernal

b. Green River

c. Price MULTIPLE CHOICE

Noted for decades for its many fruit stands, Fruit Way is a section of U.S. Highway 89 in Northern Utah.

14 Hogs are Utah’s dominant livestock product.

15 Hooper, which includes a Great Salt Lake island within its city limits, annually celebrates Tomato Days.

by BRIDGER PARK

DUST ROSE IN a shimmering haze over Utah’s West Desert as a herd of mustangs thundered across the valley floor. Manes flying, hooves pounding, the animals streaked toward the horizon in a rare, full stampede. For most people, the vision would have been a fleeting brush with the untamed. For Alisa Graham, it was the beginning of a bond that would alter the course of her life.

She first encountered the Onaqui South Herd near Simpson Springs in 2021, while off-roading through the sagebrush country. Watching the horses cross the dirt road in front of her truck, she felt something click. She didn’t yet know it, but their lives were about to intertwine. The scene unfolded against a vast backdrop of salt flats, sagebrush and distant mountains. Here, silence stretches for miles, broken only by the wind and the sound of hooves.

The Onaqui are among the best-known herds in the American West, their survival caught between the protections of the Wild Horse and Burro Act and the demands of ranching and drought. When populations swell, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) rounds them up, sending some to adoption auctions and others to long-term holding pens. Many never leave confinement; others are resold to so-called kill

pens and shipped to slaughter abroad. For visitors, the mustangs embody freedom. For land managers, they represent a dilemma with no easy answers.

Alisa met her mares – Kona, the older, steady leader, and Esme, the fiery young sorrel – at a BLM holding facility in Delta. At auction they went for just $25 apiece. She hadn’t planned on adopting, but weeks of volunteering drew her back again and again to their pen. Something in their presence made her feel chosen as much as she was choosing them. On paper, it looked like a small purchase; in reality, it was a leap into an unknown future.

At first, Alisa questioned whether she was capable of caring for mustangs. She hadn’t grown up with horses, and even the thought of haltering them seemed daunting. But she had already begun volunteering with the Red Birds Trust, an advocacy group that documents roundups and promotes adoptions. Witnessing the fear and confusion in captured herds convinced her that someone had to step forward. Adopting Kona and Esme was her way of making that commitment tangible.

Her first foray into horse ownership began with little more than a promise. She built corrals and a training ring at her home in Riverton, then trailered the mares

to her property. Wide-eyed and restless, they clung to each other, trusting no one but themselves. Alisa vowed to change that. “They’ll never be separated,” she said. “As long as I have anything to say about it, they’ll always be safe.”

Building trust came slowly. She lingered by the fence while they ate, then moved closer and retreated, matching their comfort. Months of patience led to small victories: a hand on a shoulder, a halter buckled without panic. Even setbacks taught them to read each other. When Kona once crowded Alisa against a fence, Alisa held her ground until the mare sighed and stepped aside – a herd gesture of recognition. From that point, the dynamic shifted; Kona learned to yield space, and Alisa assumed the role of lead mare.

The mares’ personalities revealed themselves in contrast. Kona’s maturity made her thoughtful and steady, a natural protector who was quick to calm once she trusted. Esme, younger and high-strung, tested boundaries constantly. She tossed her

head during groundwork, challenged the rope and danced away from Alisa’s reach. Yet her fiery spirit was also what made her victories so rewarding. Winning over Esme meant earning every inch of trust.

The training stretched over two years. With the help of a private trainer, Kona eventually accepted a saddle, and Esme wasn’t far behind. Yet the most telling test of their bond came one storm-dark night when Esme colicked, a potentially fatal condition. As Alisa fought fear and struggled to steady the young mare for trailering, thunder cracked and rain whipped the corral. Then she noticed both horses standing calmly, tails to the wind. Their quiet defiance told her what words could not: be still, trust us. Esme survived surgery, returning fiery as ever, while Kona remained the watchful protector.

Only later does Alisa admit how unlikely her journey has been. She had never worked with horses before adopting Kona and Esme, and by day she works with adults with disabilities. Raised in Denver, Colora-

do, she wasn’t born into ranch life; she built it plank by plank in her own backyard. At home, her and her wife Paula’s reactions to two wild mustangs suddenly in the yard ranged from daunted and overwhelmed to gleefully excited.

Today, Alisa finds the most joy not in grand triumphs but in the daily rhythm of life with her mustangs – leading them through simple figure eights, pulling weeds with them in tow or just sharing the silence of a paddock. Sometimes neighbors stop at the fence line, marveling at the once-wild animals grazing quietly beside the woman who refused to give up on them. To Alisa, the story is less about taming the wild than learning to listen to it.

What began as a chance encounter on the desert floor has become a lifelong covenant. For Alisa, the mares she bought for $25 apiece are what she calls her “million-dollar horses” – not a financial investment, but an emotional one, measured in the bond, trust and purpose they’ve brought into her life.

Edge of the Cedars State Park in Blanding offers visitors a glimpse into the lives of the Four Corners region’s former inhabitants

Inside, pottery, tools and textiles trace 700 years of life in the Four Corners, offering perspective on how people thrived at the edge of desert and field.

MYSTERIOUS, HUMAN-HIGH sculptures loom outside the Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum. These figures re-create mythical designs carved onto rocks centuries ago by Ancestral Puebloan artists, a foreshadowing of the treasures waiting inside.

The park lies in Blanding, 75 miles south of Moab off U.S. 191. Unlike most Utah state parks, there’s no camping, hiking or fishing here. Instead, day-use visitors pay $5 ($3 for Utah seniors and children) to learn about the region’s early inhabitants, see the Four Corners’ largest on-display collection of Puebloan pottery, examine ancient tools and textiles, discover the traditions of today’s Native communities, and explore a partially excavated Puebloan village.

Edge of the Cedars sits on 6.65 acres donated in 1974 by the Navajo Development Council. The ruins were designated a State Historical Monument in 1970 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places the following year. The museum opened in 1978, and in 1994 a climate-controlled repository was added, giving it status as a federal archaeological repository for artifacts recovered from BLM, Forest Service, and state lands. The name comes from the Utah juniper, locally called cedar, which once marked the edge of cultivated fields and bare desert beyond.

The first obstacle is resisting the Museum Store, conveniently close to the entrance counter. Beyond it, a glassed-in gallery displays a 700-year history of pottery-making in southeastern Utah.

POTS, BOWLS, JUGS and mugs appear in a rainbow of colors. White and red wares, explains curator Jonathan Till, were serving dishes such as bowls, ladles and water jars. Gray-wares served for cooking and storage. In back, shelves are stacked tighter than Black Friday aisles at Walmart, with hundreds of pots on view. Edge of the Cedars calls this “visible storage,” a way to let visitors glimpse far more of the collection than a standard exhibit case allows.

Near the display’s corner stands an ancient wooden ladder salvaged from a nearby site. Its rungs look far too thin to support a modern adult. Centuries ago, long before the local A&W began serving Double BBQ Bacon Crunch Burgers, Puebloans were not so well-fed.

Temporary exhibits rotate in a wall case.

One past subject: Ancestral Puebloan mugs, made only between the late A.D. 1000s and 1200s, before locals apparently found better ways to enjoy a brew. Next up: Hopi-carved kachina dolls, representing spiritual beings that honor deities, animals or the heavens. Examples include a Little Colorado River kachina, a brown bear kachina and a Milky Way maiden. Special exhibits sometimes spotlight contemporary Native artists as well, linking the past to living traditions and giving modern creators a platform within the museum walls.

Freestanding pedestals highlight other treasures. One displays a vivid blue-andorange sash woven from macaw feathers, found north of the Abajo Mountains: proof of trade between the Four Corners and Central America. Because of light damage, Till

notes, the sash may soon be retired from display. Another pedestal holds a 14-foot rope braided from dog hair, estimated at 2,000 years old. Others feature a 13,000-yearold Clovis spear point from a time when mammoths roamed here, an 8,000-year-old yucca-fiber sandal and thousand-year-old knives chipped from chert.

The museum also showcases modern Indigenous culture. One gallery presents photographs of Southwestern archaeological sites. Murals along the stairwells depict petroglyphs and pictographs found across San Juan County, some now submerged beneath Lake Powell. Visitors also find interactive displays that connect ancient designs to their modern descendants, illustrating how traditions have survived or been adapted over centuries.

As a repository, Edge of the Cedars houses fragile perishable materials (eggshells, pollen samples, wood, textiles) that rarely make it to public display but are invaluable to researchers. These collections link scientists to a continuous record of human and environmental history in the Four Corners. Most of the repository remains off-limits, except during Archaeology Day on the first Saturday in May, when visitors enjoy talks by archaeologists, demonstrations by Native artists and special guided tours of the back rooms.

Outdoors, an ADA-accessible path encircles a small, restored pueblo inhabited roughly A.D. 750 to 1220. Visitors view the ruins from the perimeter, with one exception: a thousand-year-old kiva open for exploration. Common throughout the Southwest, these circular underground rooms likely served religious and social functions. Entry is via a sturdy ladder, hefty enough for even those of us fresh from the A&W.

Farther along the path stands the Sun Marker, an astronomical sculpture by Bluff artist Joe Pachak. Throughout the year, sunlight passes through carved openings to cast petroglyph-like images on the shaded walls, marking solstices and other celestial events.

Edge of the Cedars also serves as a cultural gateway to the region. It is part of the Trail of the Ancients Scenic Byway, a driving route linking major archaeological sites across the Four Corners. For travelers heading to Bears Ears, Hovenweep or Monument Valley, this museum provides both orientation and inspiration. By blending world-class collections with approachable interpretation, it helps firsttime visitors understand the scale of history beneath their feet while encouraging seasoned explorers to look deeper.

Departing the museum requires one final pass by the store. Those who resisted earlier may now give in, leaving with a T-shirt, book, piece of Native art or coffee mug. Back home, the souvenirs serve as reminders of the treasures discovered at Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum: a true gateway to the past of the Four Corners.

Once

on an

In Utah’s Heber Valley, one family turned milk into miracles to save their four-generation farm and build a community around cheese.

story by JACQUE GARCIA photographs by KELLI FRESHMAN

AT 16, RUSS Kohler had no plans to take over his father’s dairy farm in Midway. He was headed to Utah State University to become an engineer, and he did just that. After building a career in engineering, Russ found the long hours kept him away from his wife and six children, and the pull of the farm grew stronger. That dream grew into a mission that would demand the effort of his entire family, and eventually save the farm, through cheese.

The Kohlers’ pivot to artisan cheese helped secure their four-generation dairy

and turn it into one of Utah’s signature food destinations. Today, Heber Valley Artisan Cheese is more than a farm – it’s a gathering place for locals, a draw for visitors and a testament to how one family’s creativity and persistence preserved both their livelihood and a piece of the valley’s agricultural heritage.

It’s easy to see why Russ returned. The family’s red barn-style shop sits among green pastures with mountains in the distance, the kind of setting that invites visitors to slow down and breathe deep. Wanting to share that feeling, Russ opened the

farm to the public with daily tours. Guests gather at the shop, climb aboard a tractor-pulled trailer, and ride on hay bales to the barns.

The first stop? Petting the calves. Curious little animals, one day to 10 weeks old, wander up to visitors, suckling on fingers, tugging on shirts and angling for ear scratches. Tours continue with stops at the feeding barns, the modern milking parlor and the original hand-milking barn used from 1929 until 2017. Along the way, the family shares the story of stewarding this land for four generations.

The Kohler family dairy is more than a farm. It’s a gathering place for locals, a draw for visitors and a testament to how one family’s bold shift to artisan cheese preserved both their livelihood and a piece of the valley’s agricultural heritage.

BEYOND DAILY FARM tours, guests return for cheese classes, fondue nights and seasonal tastings that turn the creamery into a gathering spot as much as a shop.

The Albert Kohler Legacy Farm lies between the Wasatch and Uinta ranges, flanked to the east by the Provo River and just over a mile from Midway’s historic downtown. The Swiss architecture and décor of the town’s main street reflect the Kohlers’ heritage. The Heber Valley was settled in the 1800s by livestock farmers, including the Swiss-immigrant Kohlers. Russ’s father, Grant, once chaired Swiss Days, the town’s harvest festival.

Sharing the farm with visitors is important to Russ, but sharing it with his family is his greatest joy. He works alongside his sisters Whitney and Amber, his mother Caralee and, until his passing in 2023, his father Grant. Grant instilled a focus on hard work, but also insisted his children make time to help others. His death left a hole in the family, and Russ feels he has big shoes to fill. Describing his father as a hero and role model, he said he tries to practice what he learned from him every day.

“I can’t tell you how many times we pulled off the work we were doing on the farm to help someone who had a flat tire,

broken machine or flooded basement,” Russ recalls. Grant served for 22 years as a volunteer EMT and member of Search and Rescue with the Wasatch County Sheriff’s Office.

Farming has always been hard. The days are long, and there is no off-season. Today, challenges extend beyond the barn. As Midway and Heber have grown, farmland has given way to housing. The Kohler dairy, once surrounded by pastures, is now bordered on every side by homes. Add competition from industrial-scale dairies, and the need to adapt became urgent. For nearly 100 years, the Kohlers’ lives have

centered on the 102-acre farm and its 150plus cows. As the fourth generation to run the place, Russ never thought about giving up. As he put it, not making it was simply not an option. So, about a decade ago, the family committed to a new path – cheese.

Their pivot reflects a wider movement across Utah, where family farms increasingly rely on direct-to-consumer products to survive in the face of rising land values and industrial competition.

As the Kohlers watched small dairies across the state and country close up shop, they knew the value of Midway land would soon eclipse what a farmer could

Sharing the farm with visitors is important to Russ, but sharing it with his family is his greatest joy. He works alongside his sisters, his wife and his mother – together carrying forward the legacy of his late father Grant, who insisted they make time to help others.

make selling milk wholesale. They began to wonder how they would even afford to feed their cows.

It was Grant who first suggested making cheese. Though the family had raised dairy cows for four generations, they hadn’t turned milk into other products. At first the idea seemed far-fetched, but Russ returned to Utah State University for training, and the family enrolled in the school’s cheese-making program. Whitney and Amber spearheaded the cheese-making team. Russ’s wife Heather created a packaging and order-filling system. Caralee became the master taster and peacemaker – making sure her children kept working together.

On April 1, 2011, the shop opened. “I like to tell people, no joke!” Russ said. They sold out on day one. In the beginning, a few hundred dollars in sales made for a good day. Now, that would count as very slow.

Trial and error followed, but good milk makes good cheese. Even mistakes became discoveries. Once, while making a cheddar, the Kohlers ended up with a softer, milder curd with a hint of cheddar bite. They stretched it like mozzarella and sold the hybrid as “cheddarella.” Customers loved it, and people still ask for it, though the family admits they don’t know how to make it again. These days, there are still plenty of cheeses to choose from. In their first year they sold a few hundred pounds per week – now sales reach about 3,000 pounds weekly.

They now make more than 30 styles, from classic cheddars to inventive seasonal wheels, a range that keeps regulars returning to see what’s new.

Shelves hold classics like sharp cheddar, Caralee’s favorite, and inventive wheels rubbed with Tahitian vanilla bean, developed by Heather, which Russ says tastes

like ice cream that never melts. Flavored varieties such as mustard herb, lemon sage and Wasatch Back Jack, their first gold-medal winner, rotate through the case. Some wheels age for up to 10 years in the family’s “cheese cave,” with a 15-year release in the works. Rows of shelving hold hundreds of wheels in the chilly room, where the pungent bite of aging cheddar lingers in the damp air.

And with that time has come recognition. Following their first award in 2013, the Kohlers have kept on winning, moving from the Utah Cheese Awards to the American Cheese Awards and on to the World Cheese Awards. In 2022, their Lemon Sage Cheddar won gold at the world level and has placed every year since.

Cheese has secured the farm’s future, giving younger Kohlers the option to carry the tradition forward, something that became even more important after Grant’s passing.

Their cheeses continue to win national honors, and regular classes and tasting events extend their outreach. For Russ, the work carries his father’s legacy into the community. “When you lose touch with that,” he said, “you lose part of who you are.”

Heber Valley Artisan Cheese continues to nourish its community with new flavors and long-aged releases. One new offering is Juustoleipa (oo-stay-lee-pa), a Finnish “cheese bread” meant to be fired, grilled or baked. Their products are sold at the flagship store, at farm stands across Utah, and now at Harmon’s and Whole Foods statewide.

As visitors step from the cheese cave back into the sunlight, the green fields and mountain backdrop remind them why the Kohlers fought so hard to stay. For Russ, it’s proof that the farm and the family’s legacy will endure, one wheel of cheese at a time.

Bill and Toni Thayn of Price own nearly 100 Dutch ovens – about a half-ton of cast iron. What do they do with all that cookware? They cook.

The Thayns are the reigning World Dutch Oven Champions of the International Dutch Oven Society, having won the last competition held in 2019. Although COVID-19 brought the society to a close, their title has opened doors. They judged the World Food Championships in 2017 and competed there in 2021, and for years they had a regular cooking segment on Good Things Utah and Fox’s The Place. Closer to home, they share their love for Dutch oven cooking with middle school students. At Mont Harmon, Bill teaches a class that leads into the school’s annual Dutch Oven Cook-Off, where law enforcement personnel judge the results.

At the world championships, each two-person team had to produce a main dish, bread and dessert in a set time limit. Every bit of cooking – even melting butter – had to be done in Dutch ovens heated only by charcoal. For batters, frostings and whipped cream, Toni relied on a regulation non-electric Kitchen Aid hand-crank mixer modified by an Amish company in Pennsylvania.

Their winning menu featured Asian beef tenderloin, rosemary sea salt rolls and a gingersnap spice cake with cinnamon ganache and chocolate roses. They also became the first team to make sushi at the competition, figuring out how to cook rice over coals. Not the kind of foods most people expect to pull from Dutch ovens on a camping trip.

For Bill, though, it is. He grew up with a Scoutmaster who was an avid Dutch oven cook. While other scouts ate hobo dinners, his troop dined like kings. “That carried over to me,” he said. Later, while working

at Intermountain Farmers, Bill often got first dibs on the Springville-made MACA Dutch ovens they sold. For the last 34 years, he has cooked the family’s Thanksgiving turkey in one.

The Thayns first discovered competitive cooking at the Sportsman’s Expo. “I’m very, very competitive,” Toni said. Confident in their years of experience cooking at home and on camping trips, she knew they could succeed.

They entered a county fair contest that summer, won, and qualified for the world championships – where they promptly finished in last place. “But it fired me,” Toni said.

The next summer they entered about 15 Dutch oven competitions. When they returned to the World Championships, they began placing in the top three, remaining among the best for 15 years.

“We studied YouTube, every cooking channel, everything we could get our hands on,” Bill said. The couple also combed

through recipes from their collection of 500 cookbooks.

Toni said her favorites come from community cookbooks once sold as fundraisers. One of her winning desserts, a three-layer Banana Split cake, grew from a buttermilk cake recipe she found in such a book. “I like the idea that someone’s grandma is winning alongside me,” she said.

Though the international competition is gone, the Thayns keep cooking. Today, Toni sells custom cookies, cakes and chocolates, while together they roll a specially made dessert pancake cart into county fairs, farmers markets and town events.

Husband-and-wife teams are rare in competition, but the Thayns credit their success to dividing duties and letting things go. Bill handles the main dish; Toni makes breads and desserts. When asked about the secret to cooking together, Bill said, “She’d bark and bite.” Toni finished the thought: “And he’d ignore me just like he does at home.”

recipes by BILL & TONI THAYN photographs by KYLIE ELIZABETH

Utah’s reigning Dutch oven champions Bill and Toni Thayn know their way around cast iron. From hearty one-pan meals to crisp sides and holiday sweets, their recipes prove that this time-tested cookware can do it all.

Bright lemon, aromatic oregano and golden-seared chicken come together in a skillet that bakes to perfection. Every bite of rice is infused with Mediterranean flavor.

Combine chicken with lemon juice, oregano, garlic powder and salt in a zip-top bag. Marinate several hours or overnight. Preheat oven to 350°. Heat 2 tsp olive oil in a cast iron skillet over medium-high heat; sear chicken on both sides until golden (not fully cooked). Remove and set aside.

Add rice, broth, water, dried onion, oregano, salt and pepper to skillet and stir. Nestle chicken back into rice, cover; bake 30 minutes. Remove lid and bake 10-15 minutes more, until rice is tender and liquid absorbed.

4-5 bone-in, skin-on chicken thighs

1-2 Tbsp lemon juice

1 Tbsp dried oregano, crushed

1 Tbsp garlic powder

1/2 tsp salt

1 Tbsp dried onion

1 cup long grain rice (Jasmine works well)

1½ cups chicken broth

3/4 cup water

1 Tbsp dried oregano, crushed

1 tsp salt

Black pepper, to taste

Ser ves 4

This pie layers holiday spice and molasses into a creamy vanilla base, lightened with whipped cream. Nestled in a crisp crust, it’s a festive dessert that feels both rustic and indulgent.

Whisk pudding mix and cold milk in a large bowl until thickened. Stir in molasses and spices. Gently fold in whipped cream until smooth. Spread filling in cooled crust. Chill 1-2 hours before slicing. For garnish, top with extra whipped cream and a sprinkle of spices.

1 blind-baked pie shell, cooled

1 large box instant vanilla pudding mix

2 cups cold milk

2 Tbsp molasses

1/2 tsp cinnamon

1/4 tsp ground ginger

1/8 tsp ground cloves

1/8 tsp nutmeg

1 cup whipped cream or whipped topping

Ser ves 8

Brussels sprouts roast alongside smoky bacon and garlic, caramelizing until crisp on the edges. A drizzle of balsamic glaze adds sweet-tangy finish to this Thayn family favorite.

Preheat oven to 425°. In a cast iron skillet, toss sprouts, bacon and garlic. Season with salt and pepper, drizzle with olive oil and stir to coat. Roast 25-30 minutes, until sprouts are tender and bacon crisp. Drizzle with balsamic glaze before serving.

1 lb Brussels sprouts, trimmed and halved

6 slices bacon, cut into pieces

3 cloves garlic, minced 1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil

Salt and pepper, to taste

Balsamic glaze

Ser ves 4

What’s in Your Recipe Box? The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@utahlifemag.com.

Utah’s landscapes hold countless stories waiting to be told. In echoes of stone, sage and sky, poets reveal narratives both timeless and fleeting, each alive with place. Together, they form a mosaic as vibrant and varied as Utah itself.

Matthew Ivan Bennett, Midvale

Bring me the West Desert in a stone, one humming with Indian paintbrush –dots of pink in the moon-wet sand.

In the stone should be our onetime bodies, goosebumped from a canyon’s breath, their hands running over bluffs of desire.

Let the stone be topaz – amber-colored –screaming with men who saw fire fall, glittering with the blood of dead tongues.

If possible, dirges of lost sacred places ought to blast like an organ inside, inviting me to the world under the world.

I don’t know if this is too much to ask of a stone, or if we should ask much more of stones because stone was here before cities and adzes.

Bring me the First Word in a stone, bring me the bedrock of Grace, the courage to lie on red earth for the last time.

Melissa Crowther, Ogden

Most mornings are seemingly ordinary, But some are pure magic In the way the light crests

The nearby Wasatch Mountains.

And I want to say, “Slow down. You’re missing the arrival of a new day!”

To all those people who Rush about in metal boxes.

What if everyone stilled and turned Towards the first rays dawning, Like some sort of ancient ritual, And with bowed heads

Give thanks for another day?

What if we acknowledged The elegance of that golden silk; Streaming down, weaving its way To envelope all with life giving presence?

Oh, how a sunrise could change many hearts!

Garry Glidden, Saint George

In the realm of Utah, where nature’s hues collide, Change weaves its tapestry, a sacred tide. From mountain peaks to the desert’s barren land, Transformations dance, guided by the universe’s hand.

Within ancient canyons etched by time’s caress, Whispers of change possess a timeless finesse. Sculpted by forces fierce and wild, They shape and erode narratives compiled.

The human heart, a vessel of change, Seeks solace amidst life’s boundless range. We, too, evolve, like canyons worn and weathered, Embracing shifts as seasons are tethered.

As summer sun gives way to winter’s chill, Our souls endure a metamorphosis instilled. Within our essence, flickers of desire, To shed old skins, like quaking aspen’s fire.

Aspen Groves, a symphony of gold, Reflect on our journey, stories yet untold. Leaves ablaze, surrendering to the breeze, Reminding us that change is inherent, with ease.

Like the Great Salt Lake, ebbing and flowing, Human experiences forever growing. Through heartache and joy, triumphs and loss, We sail the tides, accepting change’s gloss.

Beneath the starlit sky, we find our way, In Utah’s vastness, embracing the sway. Nature’s tableau, an ever-shifting scene, Mirrors our souls in a constant routine.

The red rocks stand steadfast, witnessing time, Ancient echoes mingle with our rhyme. Through deserts and plateaus, the resilience we find, Adapting, evolving, like the canyon’s mind.

In Utah’s embrace, change is a constant guide, A testament to nature’s ceaseless stride. Within our souls, the echoes of her call, To embrace transformation, standing tall.

For a change, like Utah, is both fierce and grand, A kaleidoscope of colors, earth’s command. So let us journey with open hearts and minds, Embracing change as nature’s gift unwinds.

Ellen R. Liebelt, South Jordan

Off on the highway the car is full Anticipation awakens in each soul For change is suddenly in the air Something new to see is everywhere.

A colorful adventure around each bend Trees turning yellow at summer’s end Oranges and reds turning from greens Lift the spirits with their vibrant scenes.

Drive along this mountainous route

Delight as a squirrel races out Some deer look up from where they browse And cowboys with dogs are herding cows.

Pull off the side to stretch the legs

Take a photo as the beauty begs Breathe deep the air crisp and fresh

Enjoy the ride where seasons mesh.

Send your poems on the theme “Where We Began” for the January/February 2026 issue, deadline Nov. 1 and “The Thaw” for the March/April 2026 issue, deadline Jan. 1. Email your poems to poetry@utahlifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

A Diné artist threads land, legacy and light into every brushstroke

IN SOUTHEASTERN UTAH, artist Gilmore Scott sees stories written in shadow. From his home in Montezuma Creek, near Bears Ears National Monument, he translates the land’s rhythms and his Diné (Navajo) heritage into vivid, geometric paintings pulsing with motion.

His connection to art stretches back as far as he can remember. From grade school through high school, his love grew from drawing to painting, mixed media and fine art. Raised in Blanding, Scott watched his mother weave traditional rugs – hypnotic diamond patterns and zigzag designs filling the loom.

Today, he incorporates those motifs into his work, especially the “eye dazzlers,” diamond-shaped patterns that create an illusion of movement. “It’s my way of paying tribute to her,” Scott said.

Scott studied art formally at the College of Eastern Utah in Price and Utah State University in Logan until 1999. But his path took an unexpected turn when

he joined the U.S. Forest Service during college. His seasonal job as a wildland firefighter became a nine-year career, where he learned to rappel out of helicopters and scour vast landscapes for the first signs of fire after lightning storms.

That high-altitude view reshaped how he saw both the land and the canvas. From a helicopter, gauging the scale of plants can

“My

art is another extension of the way we tell stories.” –Gilmore Scott

be tricky, so Scott learned to read shadows. “A lot of my art pieces now cast big shadows across the canvas,” he said. “Scanning the horizon for nooks and crannies where smoke could come from helped me see the land a lot deeper.”

After leaving firefighting in 2010, Scott turned to painting full time. He developed

a signature style blending evocative color with traditional Diné design. Hard geometric edges meet soft atmospheric washes in his acrylic and watercolor works.

In his painting “Monsoons Dazzle Over the Bears Ears,” housed in the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, the twin buttes of Bears Ears rise under swollen storm clouds. The monument, nearly 2 million acres in Utah’s southwestern corner, is deeply sacred to the Diné and other Indigenous peoples.

Unlike most depictions of Bears Ears from the west, Scott paints it from the east – the view he grew up with. From that side, two buttes and a flattened mesa form the snout. “That’s how I knew it. That’s how I show it,” he said.

Storms hold deep symbolic weight in Scott’s work. According to Diné oral stories, male storms arrive first – bold, thundering tempests that shake the earth and drive out winter. Then come the female storms, gentle and steady, soaking the soil. On canvas, his male clouds are dark and forceful; the

females shimmer in soft blues and purples.

Scott’s dynamic use of color defies expectations. While desert art often leans on earth tones and muted pastels, his canvases explode with indigo skies, fiery orange sands, deep crimson shapes and bursts of turquoise. Low shrubs fleck the golden plains, and elongated silhouettes of women in moccasins and skirts dot the horizon. “When you’re out there early in the morning or the light hits just right – man, those colors pop. I just paint what I see,” he said.

As part of a matriarchal society, Scott strives to capture strong female presence in his work. Canvases like “Our Matriarch, Weaver of the Chiefs” show a woman’s legs leading sheep across the desert. Her skirt flutters in the colors of a monarch butterfly, symbolizing life’s transitions and the longevity of women in Diné culture.

Scott’s paintings have been featured at the Springville Museum of Art, St. George Art Museum, Chase Home Museum in Salt Lake City, Bluff Arts Festival and numerous Indigenous art markets around the state. But some works are shared only during certain seasons, in keeping with the traditions they depict. One such piece, “Ma’ii Bizo, bahané” (“Coyote’s Star Story”), tells a tale reserved for winter months.

Now a father of two daughters, Scott sees his art as a bridge between generations. “My art is just another extension of the way we tell stories,” he said. “I want them, and people who see my art, to feel Diné’s deep reverence for the land.”

From the vivid contours of Bears Ears to woven patterns passed down through his family, Scott’s paintings bind past to present in colors that will never fade.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Each November, Western buffs and would -be desperados descend on Green River to relive frontier lore. Outlaw Days honors local outlaw George “Flat Nose” Curry –a member of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch – along with fellow miscreant Gunplay Maxwell, turning the town into a weekend stage for Old West fun.

Saturday begins at the Green River Gun Range with Cowboy Action Shooting at 10 a.m. Competitors in boots and holsters wield pistols, rifles and shotguns at steel targets in scenarios inspired by classic gunfights and frontier films. A light-hearted milk jug shoot runs alongside.

Afternoon brings a horseshoe tournament from 2-4 p.m., while a vendor fair from 10 a.m.-3 p.m. showcases Indigenous

jewelry, Western crafts and other intricate handmade wares.

As the sun dips low, the outlaws call a truce and gather downtown at the event center.

Plates of smoky barbecue are served at 5 p.m., followed at 5:30 p.m. by cowboy balladeer Brenn Hill of Hooper, whose music blends rodeo grit with family storytelling. The night caps with cowboy poetry, a Western dress contest and awards – proof that in Green River, style and storytelling matter as much as sharpshooting.

Discounted lodging is offered at several motels, with camping available at the local KOA. Tickets for dinner and the concert are usually sold in advance.

outlawdays.com. (435) 820-0592.

This long-running diner is beloved by locals for its retro charm and hearty portions. Expect red vinyl booths, friendly service and comfort food classics ranging from burgers and mini pizzas to onion rings and creamy shakes. Don’t miss the fresh donuts, often still warm in the morning. 30 E. Main St. (435) 564-3563.

Set on the banks of the Green River, this family-owned inn offers quiet rooms with modern amenities and warm hospitality. Opt for a river-view room with a private balcony, or relax poolside after a day of exploring. Guests praise the hearty breakfast buffet and easy access to nearby trails and Arches National Park. 1740 E. Main. (435) 564-3401.

Green River residents relive frontier fun each November with Outlaw Days.

13-JAN.

For a decade, Thanksgiving Point has ushered in the season with Luminaria, Utah’s largest Christmas light show. The 50-acre Ashton Gardens transform into a holiday wonderland where millions of twinkling lights guide guests through more than a dozen themed areas, each blending festive whimsy with moments of quiet reflection. At the heart of the display is the Merry Mosaic – a 120-foot Christmas tree surrounded by 6,500 programmable luminaries. The lights dance across the hillside in a choreographed show set to holiday music, with reindeer, snowflakes and glowing images shimmering against the night sky. Midway through, families gather in Luminaria Village, where firepits, igloos and s’mores bring welcome warmth. Private igloos and firepits can be reserved,

while a punch pass offers a mouthwatering culinary tour of holiday treats.

The Waterfall Amphitheatre hosts the crowd-pleasing Fire & Ice Show, an eight-minute blend of pyrotechnics, jets of water and lighting effects performed every 20 minutes. For stillness, the Tree of Life Garden offers a contemplative walk among 130 bronze sculptures by Utah artist Angela Johnson, depicting the life of Christ and the “Book of Mormon’s” Tree of Life vision.

Timed tickets are offered every 15 minutes, Monday through Saturday (closed Sundays and Christmas Eve/Day). Allow at least 90 minutes, dress warmly and arrive early – the hardest part may be convincing the kids it’s time to leave. thanksgivingpoint.org. (801) 768-2300.

BAAN THAI CUISINE

A cozy stop near Cabela’s, serving roast duck curry, larb, drunken noodles and pad see ew in a casual, low-light setting. 3700 Cabela’s Blvd., Ste. 355. (385) 455-4991.

This 1895 red-brick Victorian B&B in Provo offers charm and luxury with jetted tubs, themed rooms and historic character. 383 W. 100 South, Provo. (801) 374-8400.

Moab Folk Festival

Nov. 7-9 • Moab

The twang of guitars, banjos and fiddles fills the crisp autumn air at this annual folk festival. Friday and Saturday night shows are hosted in historic Star Hall, while Saturday and Sunday daytime concerts unfold at Moab City Ballpark beneath the red rock cliffs. (435) 260-1756.

Glass in the Garden Art Show

Nov. 7-Dec. 21 • Salt Lake City

Red Butte Garden and Arboretum displays hundreds of blown glass and kiln art pieces. Exhibits include a kaleidoscope of colorful garden art, plates, trays, bowls, sculptures and jewelry, all inspired by natural forms. Meet the artists Nov. 8, 2-5 p.m. 300 Wakara Way. (801) 585-0556.

Southern Utah Blues Festival

Nov. 8 • Ivins

Blues echo off the soaring red rock cliffs of Tuacahn Amphitheatre in Padre Canyon. The country’s premier blues festival features a star-studded lineup, including Mr. Sipp, Vanessa Collier, Tony Holiday, Anthony Geraci and Shanda & the Howlers, playing to packed, dancing crowds. 1100 Tuacahn Dr. (800) 746-9882.

Monument Valley

Veterans Marathon

Nov. 15 • Monument Valley

Runners honor Diné (Navajo) military heroes with a marathon, half marathon and 4-mile race through Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. The course includes a tribute to one of the Code Talker legends, set among towering sandstone buttes. (928) 429-0345.

Crazy Daisy Holiday Show

Nov. 21-22 • Sandy

More than 200 small businesses sell handmade holiday wares at the Mountain America Expo Center. Santa appears both days, with live entertainment, food vendors and prize giveaways. Hours are Sat. 1-6 p.m.; Sun. 10 a.m.-6 p.m., perfect for family browsing. 9575 S. State St.

The Great Carp Hunt

Nov. 29-30 • Provo

Anglers help restore Utah Lake by catching and removing invasive carp. The event runs Sat. 8 a.m.-5 p.m. and Sun. 8 a.m.-2 p.m., with awards for longest, heaviest, smallest and most caught, plus bragging rights for months. 4400 W. Center St. (801) 375-0731.

Dickens Christmas Festival

Dec. 3-6 • St. George

The Dixie Convention Center transforms into an Olde English shop from the Victorian era. Fortune tellers, royalty and Father Christmas wander the rows of booths, with vendors selling time-period goods and hearty seasonal fare. Open daily 10 a.m.-9 p.m. 1835 Convention Center Dr. (435) 668-9969.

Holiday Sleigh Rides

Dec. 6-27 • Wellsville

Glide through the American West Heritage Center in an elegant horse-drawn sleigh, stopping at a 1900s farmhouse, Santa’s Workshop, cocoa bar and sledding hill. Admission is $9, with a twinkling lights show after dark. 4025 S. Hwy 89-91. (435) 245-6050.

The Life of a Miner’s Wife in Park City

Dec. 10 • Park City

Mike Nelson shares stories of his grandmother Zula Nelson’s life as a miner’s wife from 1937-1952, offering insight into daily hardships and small joys of mining families. 5-6 p.m. 2079 Sidewinder Dr. (435) 649-7457.

Luge World Cup

Dec. 12-13 • Park City

Olympic hopefuls rocket down an ice track at speeds over 80 miles per hour to compete for the sport’s highest accolades. Admission is free. Food, beverages and activities available throughout event. Utah Olympic Park, 3419 Olympic Pkwy. (435) 658-4200.

Camp Floyd Christmas

Dec. 13 • Cedar Valley

Celebrate Christmas as Camp Floyd’s soldiers once did. Tour the Commissary and Inn decked in festive décor, and visit Santa from noon-4 p.m. Admission $15. 10 a.m.-4 p.m., with carols and pioneer treats. 18035 W. 1540 North. (801) 768-8932.

Annie

Dec. 16-22 • Vernal

The beloved musical brightens Vernal Theatre with hits like “Tomorrow.” Evening shows at 7 p.m.; matinees at 2 p.m.

Local actors shine in a timeless story. 40 E. Main St. (435) 219-2987.

Holidays Around the World

Dec. 17 • Cedar City

Kids learn global holiday traditions through crafts, games and activities. Event runs 10 a.m.-noon, $10 per child or $25 per family, encouraging curiosity and celebration. 59 N. 100 West.

North Pole Express

Thru Dec. 30 • Heber City

Board the Heber Valley Railroad for a 90-minute ride to the North Pole with singalongs, cocoa, cookies, a souvenir mug, a brass sleigh bell from Santa and entertainment from elves, all wrapped in festive cheer. 450 S. 600 West. (435) 654-5601.

Since 2003, the Moab Folk Festival has turned a desert ball field into a stage, sending bluegrass, ballads and indie anthems echoing off redrock cliffs dusted with snow. Each year, locals, visitors and folkies gather to celebrate music as timeless as the landscape surrounding it.

SOn a baseball diamond in the midst of a national park paradise, the stars come out in the daytime.

AM BUSH, the headliner for the 2024 Moab Folk Festival, stood at home plate, surveying a crowd of a thousand music lovers scattered across the ball field. He carried a mandolin, not a bat, and looked at us thoughtfully before quipping, “That last pitch was a little low and outside.”

On that November afternoon, it was the only pitch that missed.

I’d joined the folkies in the mountain-biking capital of the universe, but not to cruise slickrock. Since 2003, the Moab Folk Festival has sent the people’s music echoing off the red-rock escarpments, with a dusting of snow often visible high on the La Sal Mountains. The gathering features everything from bluegrass to cowboy ballads, indie to Americana. Folk music is hard to pin down. That’s what makes it great.

This became clear when a giant sousa-

phone trundled onto the stage, carried by Anna Moss and Joel Ludford. They oompahed their way through the funny, gruesome story of how drag racers once smashed into their hippie van, driving Ludford’s femur through his pelvis. “It’s not as sexy as it sounds,” he told us, and we all laughed and winced together.

In Moab, the music can shift from solo guitar to a bevy of bluegrass pickers to the odd tuba, but it all turns on storytelling, singing and plucking. Over the years, Judy Collins, Richard Thompson and Suzy Bogguss have all stood at home plate and knocked it out of the park.

This Nov. 7-9, more eclectic folkies will fill downtown venues. A one-day pass on the ball field costs $76.64; two days, $145.90. More intimate performances at Star Hall are $60.40 – further proof Moab folkies never round up to the nearest dollar.

What began as Melissa Schmaedick’s vision to bring singer-songwriters to Moab has grown into a community effort, with director Cassie Paup and 150 volunteers filling the outfield with fans and setting musicians up at home plate every November.

CASSIE PAUP HAS run the festival for the past five years. She got her start in 2014 when founder Melissa Schmaedick spotted her crossing a parking lot and asked what she was up to. “Looking for a job,” Paup replied –and soon she was learning the ropes.

Schmaedick, a remote-working USDA economist had launched the festival as a way to unite Moab’s music scene and bring visitors to town as winter set in.

Eric Jones was also there at the beginning and remembered the seat-of-the-pants feeling. “Melissa’s vision was for a singer-songwriter folk fest,” he said. “That kind of music was available in an urban environment, but not here.”

Here is Moab – a small town squeezed between national parks and geological marvels, where mud-splattered mountain bikers with scraped-up knees fill the cafés and campgrounds. Add music, and you make magic.

Schmaedick handed over the reins after

running a virtual festival in 2020. She returned to Washington, and Paup stepped up, along with her assistant, Emily Sudduth. Together, they marshal 150 volunteers to fill the outfield with fans and set musicians up at home plate.

Organizers have also expanded the experience with the Moab Folk Camp, a weeklong gathering before the festival where musicians and enthusiasts hone their craft. Singer-songwriter Cosy Sheridan runs the camp, offering classes such as “Cooking with Fresh Ingredients” (the chords beyond C, D, G and E minor) and “Singing with Heart, Soul and Body.”

“There’s a large subculture of music camps,” Sheridan said. “We treat it as an avocation and a way to tap into creativity. It’s about getting past self-censorship and finding something in yourself that needs to get out.”

In other words, she sees the camp as a place where musicians can treat playing as

a joyful hobby, loosen up and create without worrying about being judged. The idea is to stop overthinking and simply let the music come out.

Just imagine the campfire songs – leagues beyond the usual old singalongs.

This year’s festival lineup features Elephant Revival, who will bring a washboard and assorted strings on Saturday, and Yonder Mountain String Band, doing their propulsive bluegrass on Sunday. Another half-dozen acts will round out the weekend.

“We generally try to have more singer-songwriters on Saturday,” Paup said, “and bigger band sounds on Sunday.” She noted the lineup has evolved. “Billy Strings has changed things with the jamgrass movement, and young people like it. People want to dance and hear upbeat music. So we’re broadening the mandate with more energetic bands – without alienating geezers like me.”

Just in time, before folk music fades to gray.

Sheridan praised the festival as “unusually friendly and well run, and of a size where you can interact with the artists.”

One of my favorite under-the-radar discoveries is Humbird, a folk-rock group from the Twin Cities. I was thrilled to see them lead off last year. There they were, 25 yards away at home plate as I sat in right field.

After their set, I wandered to the merch tents and found Siri Undlin, the band’s lead singer and songwriter. I launched into a story about how, the last time I’d seen them in Denver, parking issues caused me to miss my favorite Humbird song, “Pharmakon.” In Moab, I’d finally heard it live, straight from the folkie’s mouth.

Undlin smiled and said, “Well, I guess you’ll just have to show up early next time.”

And that’s part of the charm here: whether you’re early, late or somewhere in between, there’s always another tune waiting on deck.

By including banjos and sousaphones, tender stories and danceable jams, the festival helps redefine “folk music.”

Through Moab Folk Camp, musicians are reminded to loosen up, create without worrying about being judged and see music as a joyful hobby.

AFEW YEARS AGO, I witnessed a surreal scene at Silver Lake up Big Cottonwood Canyon: a large group of tourists taking pictures in front of a giant moose – as if it were a tame attraction at a petting zoo.

Worried I was about to witness some extreme herbivore-on-human violence, I frantically tried to wave them away. Thinking I was just being extra friendly, they waved back. I stuck around in case police needed a witness, but the moose eventually just dropped a pile of doo-doo at their feet and wandered away.

I remember shaking my head at the naivete of these tourists – but then catching myself. It occurred to me that most Utahns who live along the Wasatch Front (including myself) have a shaky understanding of how to interact with our state’s deer, elk and moose. Torn between seeing them as cute, anthropomorphized Disney characters, or as genuinely wild creatures, we engage in some awkward encounters.

A while back, I read a news story about a young boy who was mildly gored by a buck in a Bountiful alleyway. The lesson was to become more “wild aware,” but the details suggested both humans and deer have a long way to go. Why a deer was hanging out in an alley was never explained. The kid said blandly, “a deer walked up behind me… and hit me.” His mom wondered if he’d been smeared with “deer snot,” while a buddy guessed the puncture wound came from a “deer bite.”

If the article hadn’t repeated the word “deer,” you might have assumed the attacker was a bully or rowdy neighborhood dog.

story by KERRY SOPER illustration by JOSH TALBOT

Then there was the orphaned deer in Herriman who imprinted on humans. Locals treated him like a mascot, even giving him a Pixar-worthy name – the geographically appropriate “Copper.” I wish I could say he lived happily, frolicking each spring with local dogs, eating cotton candy at Summerfest and wearing a cow disguise each fall to fool hunters. But the ending was swift and predictable: a grouchy neighbor complained about disease risk, and the DWR reluctantly smelted some Copper.

The further you get from the Wasatch Front, the less confusion reigns among rural Utahns. Sometimes that pragmatism turns into unnecessary warfare – like when a guy in central Utah was so irritated by deer invading his apple orchard that he at-

tached a trip wire to a loaded shotgun. He forgot to tell his wife, who had invited her ministering sisters to pick fruit. Thankfully no one died, but one sweet lady can no longer walk her butt through airport metal detectors without setting off alarms.

Because I split my growing-up years between the Wasatch Front and a small farming town, I developed an especially muddled mindset about these animals. For example, there was the time as an 18-yearold that I tried to mercy-kill a deer with my bare hands. My parents had recently fled Utah Valley for the peaceful roads of Sanpete, and I was eager to fit in with the local teenagers from farming families.

That anxiety was probably in my head one afternoon when I saw an injured deer

on the side of Highway 89, a few miles north of Ephraim. I foolishly pulled over for a closer look, not realizing that the DWR deals with these situations.

Eager to be self-reliant, I decided it was my job to put this poor animal out of its misery. My methods were pathetic. Let’s just say if you’d driven past, you would have been alarmed to see a guy sneaking up behind an injured deer with a large rock, or later (when that didn’t work), acting out some kind of primal (but ineffectual) attack with a flimsy plastic knife.

AUTHOR

It was during that last attempt that a guy pulled up in a truck. Flooded with guilt, I jumped back and nonchalantly wandered away, as if to say, “What? Nothing weird is going on here.” Then I noticed he was carrying a rifle. My first thought was: Is he going to

shoot me? But he explained that he was there to “take care” of the deer. I tried to nod casually and gestured for him to go for it, but was deflated when he turned to me and asked, “Do you know how to work a gun?” Turns out he was just as clueless as me. All I can say is that I later asked my mom at the dinner table whether our insurance included access to long-term therapy.

Kerry Soper writes and teaches satire, humor and history from Provo.

Then there was the time I was camping with friends at Christmas Meadows in the Uintas. This was years before I got LASIK surgery to fix extreme near-sightedness, so I was confronted with the choice of an evening trail run with clunky glasses or no corrective lenses at all. Vanity pushed me toward the second option.

About a mile in, I stopped in alarm when I came upon a massive moose, 20 yards

away, casually blocking the trail. It looked like a calf was nearby too.

At first, I hid behind a pine tree, hoping they would move on. The moose stubbornly stayed put, so I got creative, calling out things like, “Yah, moosey!” With no reaction, I tried a guttural mating call. Just then, a family of hikers appeared behind me, stopping in their tracks. Unsure if they were alarmed by me or the moose, I whispered “MOOSE MOTHER! MOTHER MOOSE!” The parents foolishly urged their kids to keep walking.

As they approached the moose, I braced for mayhem – but they simply ducked under its belly and kept going. Disoriented, I moved forward and was appalled to discover I had been yelling at a collapsed pine tree.

Oh well, when in doubt about how to deal with an unfamiliar entity in the outdoors – whether herbivorous or coniferous – it’s best to remain “wild aware,” and perhaps wear corrective lenses.