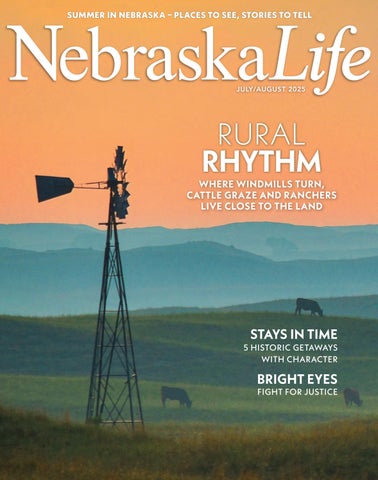

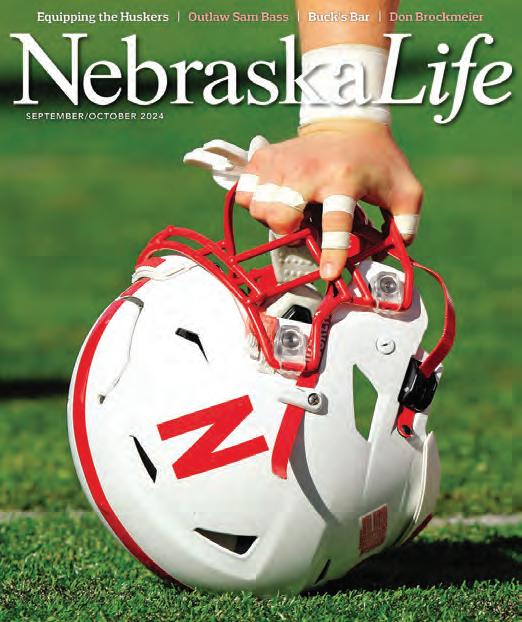

JULY/AUGUST 2025

RURAL RHYTHM

WHERE WINDMILLS TURN, CATTLE GRAZE AND RANCHERS LIVE CLOSE TO THE LAND

BRIGHT EYES FIGHT FOR JUSTICE STAYS IN TIME

5 HISTORIC GETAWAYS WITH CHARACTER

JULY/AUGUST 2025

FEATURES

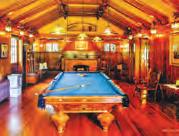

22 Spade Ranch Store

This historic Ellsworth general store has weathered outlaws, blizzards, and boom times to remain a steadfast landmark. story and photographs by Nicole Louden

28 Stays In Time

Five one-of-a-kind getaways transport guests to the past – stay in trains, wagons, boats and bins. by Ariella Nardizzi

34 Where the Grass Holds Stories

With his lens and a deep reserve of trust, Alan J. Bartels reveals the quiet grit of Nebraska’s Sandhillers. by Ariella Nardizzi photographs by Alan J. Bartels

48 Bright Eyes

A courtroom plea for freedom launches Susette La Flesche’s lifelong fight for Native American justice. by Ron Soodalter

DEPARTMENTS

11 Editor’s Letter

Chris Amundson shares thoughts and life lessons from Nebraska.

12 Flat Water News

Boxes for Troops needs donations; Seward’s rise as a filmmaking hub; Paper Moon Pastries’ kolaches and 1930s charm; York artist’s intricate paper cuttings; David Dorsey: two-time Nebraska Life art winner.

20 Trivia

Our quiz climbs to Nebraska’s highest places. Answers on page 64 (no peeking).

DEPARTMENTS

41 Poetry

Nebraska’s lakes echo through each verse, shaped by the land and those who live on it.

44 Kitchens

Pineapple and jalapeño pair up in sweet-spicy salsas –summer’s freshest dance partner.

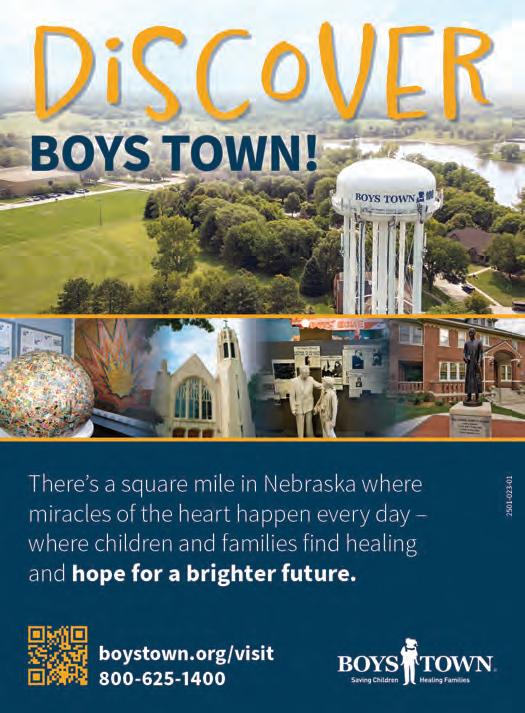

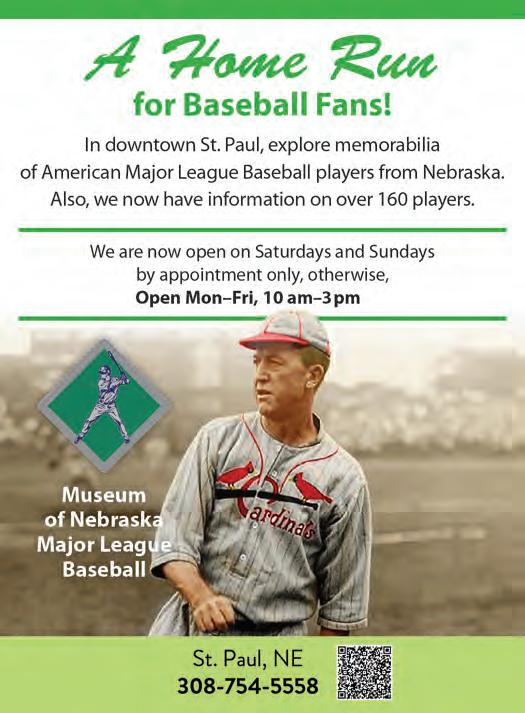

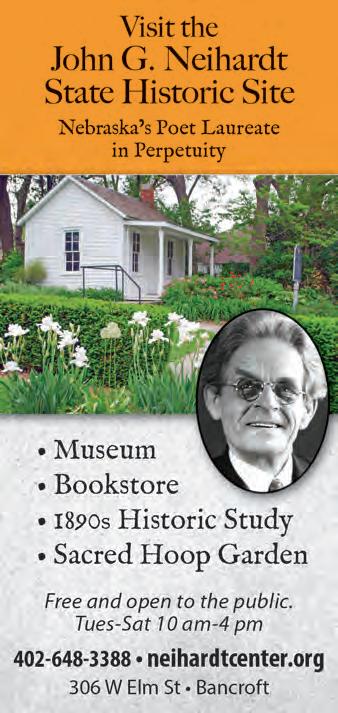

54 Museums

Big or small, Nebraska’s museums preserve history and heritage for all to explore.

60 Traveler

Ride the Cowboy Trail in Valentine for its 30th anniversary; Dusty’s Pumpkin Fest brings fall fun to Buffalo Bill State Park.

First light warms the Sandhills as cattle graze beneath a windmill in Loup County – a quiet moment from Nebraska’s ranch country. See story page 34.

BY

JULY/AUGUST 2025

Volume 29, Number 4

Publisher & Editor Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher Angela Amundson

Photo Coordinator Erik Makić

Staff Writer Ariella Nardizzi

Design Mark Del Rosario

Editorial Assistant Savannah Dagupion

Advertising Sales Sarah Smith

Subscriptions Shiela Camay

Intern Lucy Walz

Nebraska Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 1-800-777-6159 NebraskaLife.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@nebraskalife.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@nebraskalife.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@nebraskalife.com or visiting NebraskaLife.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@nebraskalife.com.

Thistles and Other Inheritances

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT Nebraska that doesn’t rush. Maybe it’s the way the horizon stretches a little farther here, or how conversations settle into quiet before trust fills the space. I learned that rhythm riding with my Grandpa Walt in his Oldsmobile Delta 88, jugs of 2,4-D and water sloshing in the trunk beside a hand pump sprayer. We’d drive from Norfolk to his farm ground in Wayne County, walking the fence lines to spray musk thistles. He didn’t say much. Just pointed, sprayed and moved on. But those mornings became their own kind of story. One he was willing to share, in his way.

It wasn’t just weed control. It was inheritance. A quiet stewardship passed down through habit more than words. You watch. You do. You return next year and do it again.

You’ll feel that same thread in the Sandhills, where the grass holds memory and ranchers rise with the sun to work land they didn’t just buy, but inherited with responsibility. In this issue’s photo essay, Alan J. Bartels takes us into that world, one he’s spent decades earning a place in. He doesn’t just photograph the land. He listens to it. “Where the Grass Holds Stories” reflects a quiet, generational strength that doesn’t need to declare itself.

That same connection echoes in Ellsworth, where “Morgan’s Cowpoke Haven,” once a Spade Ranch outpost, still creaks with history. Wade Morgan keeps the doors open through fires, blizzards and even a brush with Charlie Starkweather. But what stays with you is the quiet care and the worn floorboards that remember every customer.

This issue also remembers Susette La Flesche (Bright Eyes), who stood in an Omaha federal court in 1879 and helped shift the course of American law. Her testimony in the landmark case of Ponca Chief Standing Bear gave voice to a truth that still resonates: personhood is not a privilege, it’s a right.

In Walthill, her sister’s hospital is being reborn – not as a museum, but as a working center for healing, culture and art. The story has new stewards: Nancy Gillis, Vida Stabler and two teens, Claire Marsh and Meredith Wortmann, who’ve carried it to the Smithsonian and brought it home again.

This issue also takes you to five historic getaways, a riverbank full of poetry, and a stretch of the Cowboy Trail that’s been connecting communities for 30 years – and through it all, from courthouse steps to cattle trails, you’ll find people tending what they’ve been given.

Some inherit the family ranch. Some preserve culture or art. Others just keep the ditch clean and the thistles down.

Because not all history makes it into a museum. Some of it rides shotgun on a gravel road with a jug of 2,4-D and a man who knows what matters.

Thanks for riding along.

CHRIS AMUNDSON Publisher & Editor editor@nebraskalife.com

Noteworthy news, entertaining nonsense

Try Seward. Hollywood?

BY ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Sixty-nine films will screen at the historic Rivoli Theater in Seward this September for the 5th annual film festival, which supports new and established Nebraskan filmmakers.

The marquee of the historic Rivoli Theater, built in 1919, casts a warm flickering glow onto Seward’s Main Street. Murals painted as a Works Progress Administration project in 1930 line the auditorium walls like a silent audience. Each fall, as the lights dim and reels roll, Seward becomes a quiet capital for Nebraska film.

The Flatwater Film Festival returns Sept. 26-28 for its fifth year. There are no trophies, red carpets or cutthroat competitions – just a gathering of storytellers who share one thing in common: a love for cinema and a tie to Nebraska soil.

Since 2021, six friends – Greg and Em-

ily Gale, Josh and Elizabeth Weixelman, Heather Waite and Patrick Lambrecht –have run the festival to champion the next generation of Nebraska filmmakers. While cities like Hollywood and New York dominate the industry, co-founder Greg Gale says Nebraska’s film scene is thriving in its own right, with homegrown stories and talent ready for the spotlight.

Recent highlights include Atomic Zombies (2024), a horror-comedy by Lincoln’s Jameel Harleston Whitlock; All Grown Up (2023), a 39-minute drama by Meg Doyle about a young woman torn between home and change; and The Last Prairie (2022), John O’Keefe’s 61-minute documentary exploring one of North

America’s last intact prairies in Nebraska through the voices of ecologists, ranchers and Native people.

This year’s event will screen 69 films to audiences nearing 300, alongside roundtable discussions, educational seminars and a 48-hour filmmaking challenge. The project is supported by the Nebraska Arts Council, which receives support from the State of Nebraska and the National Endowment for the Arts.

The most popular genre screened is documentaries, often highlighting the emotional, internal and economic struggles farmers and ranchers face. In a state shaped by stories of the land, the festival provides a silver screen for the ones still being written.

Pack a box, bring a gift for troops

BY ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Santa may not visit military bases in person, but thanks to community support, Pinnacle Bank in Columbus makes sure deployed service members from around the country receive a touch of home during the holidays.

Now in its 15th year, the Christmas for Our Troops donation drive begins Sept. 11 and collects gifts for active-duty military members serving across the globe – from soldiers and sailors to airmen, reservists and coast guardsmen.

Requested items include travel-size shampoo, socks, dental care products, T-shirts, beef jerky, hot cocoa packets, books, puzzles, DVDs and even miniature

footballs. “If we can pack them in boxes, they go,” said Kim Tobiason, a longtime volunteer who’s helped with the program for over a decade.

Donors can also purchase directly from an Amazon wishlist, with items shipped straight to the bank. Monetary donations help cover the postage and fill in remaining needs and items.

Those who knit, sew or craft are encouraged to contribute handmade items. “Gifts with a personal connection to Nebraska are always cherished by the troops,” Tobiason said.

In mid-November, the public is invited to Pinnacle Bank to help pack and ship boxes in time for Christmas delivery – a small gesture that brings comfort, pride and holiday cheer to those far from home.

Drop-off Locations: Pinnacle Bank – Columbus 210 E. 23rd St. | 2661 33rd Ave. (402) 562-8936

Last year, Boxes for Troops mailed 514 care packages to deployed service members around the world. People can donate starting Sept. 11 at Pinnacle Bank locations in Columbus.

Reading

Swimming

Walking/Bicycling

BY KRISTIN DAHL

For many children, imagination offers an escape into fantastical worlds. For Lindsey Oelling, that refuge was a dusty diner in Depression-era Kansas, captured in the 1973 film Paper Moon

Introduced to the film by her father during her younger brother’s battle with leukemia, Oelling was captivated by its warmth and resilience. One scene especially stuck with her – a playful argument over a Nehi soda and a Coney Island hot dog.

“It’s just so charming,” Oelling said. “I thought if I ever had a bakery, I’d want it to feel like that – fun, cozy and full of those little moments that stick with you.”

Today, that inspiration lives on in Paper Moon Pastries, Oelling’s bakery in the heart of Cortland. Open only on Saturdays from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., it draws crowds eager to experience a taste of tradition, community and old-fashioned sweetness.

Cortland – founded in 1883 and shaped by the railroad – has always been a small town with a big heart. Though its popu-

Cortland Bakery Rolls in Kolaches and 1930s Charm

Inspired by her Czech roots and great-grandmother’s recipes, Lindsey Oelling brings kolaches, cinnamon rolls and tradition to the table at Paper Moon Pastries in Cortland.

lation has dipped from a high of 600, the town has never lost its sense of connection. In the middle of it all, Paper Moon Pastries has become a local treasure.

Oelling’s path to opening the bakery was shaped by her childhood. As her younger brother underwent treatment, much of their time was spent in hospitals.

To protect his fragile immune system, even small joys like birthday parties had to be avoided.

“You couldn’t go see friends when they had the sniffles because it meant a hospital stay for him if he got sick,” she said.

But even in those difficult years, there was comfort in her Czech grandmother’s kitchen.

“Her kitchen was a sanctuary,” Oelling said. “Baking kolaches and cinnamon rolls wasn’t just about making food – it was about finding calm in the chaos.”

Those family recipes form the heart of Paper Moon Pastries. Oelling’s kolaches and cinnamon rolls, passed down from her great-grandmother, are now the bakery’s signature offerings. She’s added a few

creative twists of her own but remains firmly rooted in Czech tradition.

A licensed mental health therapist by profession, Oelling opened the bakery in May 2022, transforming a former hair salon into a 1930s-inspired coffee and pastry shop.

Beyond the kitchen, the bakery has helped anchor the town’s social life. Since opening, Paper Moon has hosted Cortland’s Once in a Blue Moon Fall Festival – an annual event that began with just a handful of vendors and now draws thousands. Proceeds support park upgrades, museum improvements and other local initiatives.

As Paper Moon Pastries enters its fourth year, Oelling reflects on how far it’s come. What began as a leap of faith – inspired by family, resilience and the warmth of a movie scene – has grown into a beloved gathering place.

“I never imagined the bakery would grow like this,” she said. “But seeing how the community has come together has been the most rewarding part of all.”

A Cut Above

From York to New York, artist Kent Bedient creates intricate art from paper

BY ARIELLA NARDIZZI AND LAURYN HIGGINS

A world away from the Smithsonian –where his work has been displayed – Kent Bedient lives quietly in York, Nebraska. In a modest apartment complex, the 94-yearold artist still practices an old-world craft that once took him to the windows of Tiffany’s in New York City and galleries as far as the Louvre.

His medium? Paper. With only a utility knife and practiced fingers, Bedient transforms plain blank sheets into layered, lacelike compositions. Delicate borders frame elaborate scenes – floral bursts, architectural patterns and sunbursts that radiate with precision. Every cut is done by hand. No lasers, no templates, no shortcuts.

And it all began with a simple pair of closet doors.

In 1954, after being honorably discharged from the U.S. Army, a young Bedient moved to New York City. During a visit to a friend’s apartment, he noticed a set of tall closet doors. He thought they looked bare – and decided he could create a design to cover them.

“I guess you could say from there, I found that I love the medium of paper cutting,” he said.

That moment sparked a career spanning more than 50 years. Without formal training or a blueprint to follow, Bedient taught himself to carve beauty out of the ordinary. He was one of few American artists who worked in the traditional form of paper cutting.

His professional breakthrough came when a shoe store in New York, Delman’s, admired his work but found it much too

elegant for their display. So they sent him across the street – to Tiffany’s. “I walked over with my stuff, and my work ended up in their windows three different times,” Bedient said.

Bedient’s cuttings later found their way into the home furnishings market, adapted into hand silk-screened fabrics and wall coverings. Photographs of those works are now archived at the Polk Public Library in Nebraska, which includes Bedient’s ad for Phoenix Hosiery. Bedient created a 3-D phoenix bird with wings made from delicate hosiery stockings, which was also featured in fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar.

His art has been exhibited at the Louvre in Paris, the Parsons School of Design and the Smithsonian in New York City –but after 34 years in The Big Apple, he felt ready to come home.

“I’d worked as long as I can remember,” he said. “I was looking forward to sitting on the front porch back home in Nebraska.”

In 1988, Bedient returned to York. Nes-

tled amid the cornfields and brick storefronts of this central Nebraska town, he resumed his craft, taking on small pieces for personal joy. He also served as curator at the Anna Bemis Palmer Museum for a decade, sharing his eye for detail and deepening York County’s ties to the arts. Just across Nebraska Avenue at the Kilgore Memorial Library, there’s a gallery wall that now bears Bedient’s name.

Among his most meaningful works is one dedicated to his hometown. When York Middle School opened, Bedient was commissioned to create a 4-foot paper sunburst, which still hangs in the cafeteria today. “It was a great honor to do that for my hometown,” he said. “It’s one of the most magnificent pieces I’ve done.”

Though he may be slowing down, Bedient hasn’t stopped. His latest piece? A delicate rose.

And those closet doors that first sparked his imagination?

“They never did get done,” he said, laughing.

Artist David Dorsey Wins Back-to-Back Nebraska Life Art Awards

BY LISA TRUESDALE

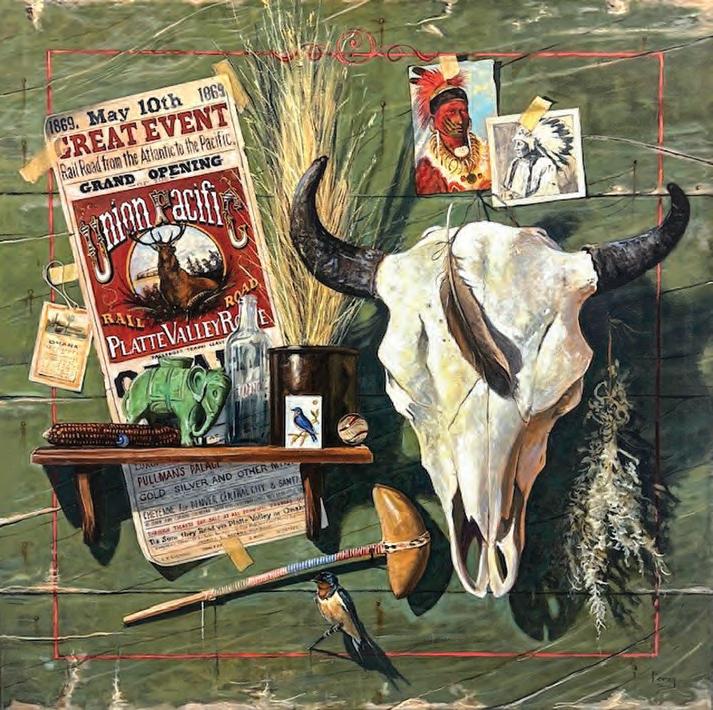

When reviewing the hundreds of entries for the 2025 Nebraska Life Art Award at the Association of Nebraska Art Clubs’ conference this June, Nebraska Life publisher Chris Amundson found himself captivated by artist David Dorsey’s “Barn Swallow,” an acrylic still-life on gallery-wrap canvas.

“Through layered imagery, the painting captures a collision of cultures and eras: the reverent presence of the bison skull and Native portraits stand in contrast to the promotional poster for Union Pacific

Railroad, symbolizing westward expansion and the transformation of the land,” said Amundson. “It’s a thoughtful, visually compelling tribute to a defining chapter in Nebraska’s story.”

The selection process is blind, so Amundson had no idea that he chose the same winning artist as last year. The style of this year’s piece didn’t tip him off, since it’s quite different from last year’s winning artwork, a portrait of a young girl reverently cradling an empty nest in her hands. Dorsey, a Valentine-based artist and former rancher, doesn’t want to be known for one particular style anyway. Instead,

Valentine artist David Dorsey won the 2025 Nebraska Life Art Award for “Barn Swallow.” The layered piece of art is a compelling tribute to Nebraska’s history of western expansion.

he simply wants to paint pieces that have a story to tell, no matter their style.

“Barn Swallow” wasn’t planned out like most of Dorsey’s pieces, and he said it was a challenge to do a painting that just kept evolving. He began with the bison skull, purchased from a taxidermist in Valentine. The rest of the images have a personal connection to him, like the castiron elephant bank that belonged to an uncle, the feather he found in front of the Valentine post office, and the marble, because he has included one in many of his previous still-life works. He’s always been drawn to the graphics on old railroad posters, and adding the painting of the Iowan chief White Cloud, by 19th-century artist George Catlin, was a no-brainer. The tiny, hard-to-spot barn swallow at the bottom gets title billing, but only because it was the last thing added, and because it’s the only element of the present surrounded by symbols of the past.

“The piece began to have a sense of history for me, and I was pleased with that,” Dorsey said, adding that he was truly honored to be selected for the award again. “Everyone will find something different in the work, and I think that is what a work of art should do. Sometimes we just need to study a painting and discover all of the little things that are there and why, and what it means to each of us.”

Dorsey’s works are currently on display at Humdinger Boots and Janine’s Flower Exchange in Valentine. They can also be viewed on his website (daviddorseyart.weebly.com) and his Facebook page (David Dorsey).

HIGH POINTS

1 Sioux County’s Kennedy Benchmark rises to 5,260 feet above sea level, standing about 245 feet above the surrounding plains. What brass feature at its summit confirms its elevation with scientific precision?

Butler County’s highest point lies on a stretch of railroad track between David City and Brainard. The rail company’s name suggests it runs through Nebraska’s center – even though Brainard is solidly on the eastern side. What’s the name of this railroad?

Less than two miles west of Cedar County’s high point sits a village with a name full of ambition. What’s the name of this tiny town that hoped its title alone would draw people in?

4

Thurston County’s high point rises just 20 feet above the surrounding land and sits at 1,550 feet above sea level. Which Native American reservation is it located on, in a county uniquely split between two tribal nations?

5 Keith County’s highest point rises just south of a state recreation area that features a lake so large locals call it “Big Mac.” If one big-name actor from Texas dropped by, he might say it’s “alright, alright, alright with me.” What’s the name of this recreation area?

6

Less than half a mile from the highest point in Adams County sits the grave of Susan O. Hail, whose dramatic epitaph claims she “died after drinking water poisoned by Indians.” According to the Adams County Historical Society, though, what illness caused her death?

a. Cholera

b. Dysentery

c. Typhoid fever

7 Sheridan County’s high point –Argo Hill at 4,213 feet above sea level – sits in the Sandhills between Ellsworth and Gordon, near the birthplace of which Nebraska author whose books captured the spirit and struggle of life on the Plains?

a. Bess Streeter Aldrich

b. Mari Sandoz

c. W illa Cather

8

Fillmore County’s highest point rises a few miles outside of Sutton and lies just over a mile from two WPAs – the Rolland WPA and the Lange WPA. The “A” stands for area –what does “WP” mean?

a. Works Progress

b. Waterfowl Production

c. W ildfire Protection

9

Nebraska’s skyline champ since 2002, the First National Bank Tower will soon be overtaken by the 677-foot Mutual of Omaha Tower. What feature will sit halfway up, offering workers a break with a view?

a. Suspended running track

b. Five-story sky lobby with terraces

c. Prairie-themed art gallery

10 Panorama Point – Nebraska’s highest spot in Kimball County – isn’t a dramatic summit, just a subtle rise marked by a stone monument, guestbook and $3 donation box. Where can visitors find this out-of-theway landmark?

a. The visitor center in Kimball

b. On private ranchland

c. At the Tri-State marker

TRUE OR FALSE

11

Speaking of Panorama Point, it sits at just over 5,000 feet above sea level, meaning no part of Nebraska is over a mile above sea level (5,280 feet).

12

At 1,300 feet above sea level, Sarpy County has the lowest high point of any Nebraska county. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the lowest point in Nebraska, a spot 840 feet above sea level on the Missouri River, is also located in Sarpy County.

13

Visitors can reach the high point of Scotts Bluff County by hiking or driving to the summit of Scotts Bluff National Monument 800 feet above the valley at 4,659 feet above sea level.

14

Nebraska’s Capitol, the first U.S. statehouse to break from classical domes, holds the record as the tallest capitol building in the nation.

15

Nebraska’s tallest structure isn’t in Omaha or Lincoln – it’s a 1,854foot broadcast tower near Monroe that beams out the signal for country music station KZ-100, based in Central City.

No peeking, answers on page 64.

COWPOKE HAVEN MORGAN ’S

Once a hub for cowboys of the Spade Ranch, Ellsworth’s general store is rich in frontier lore – from railroad-era beginnings to a brush with a serial killer

THE SUN WAS just beginning to rise on Jan. 29, 1958, over the windswept hills of Ellsworth, Nebraska. In this tiny unincorporated town where Highways 2 and 27 meet in the western Sandhills, Graham’s General Store opened its doors at 7 a.m., as it did every weekday. Two gasoline pumps stood out front. A black 1956 Packard sedan pulled off the highway to fuel up.

A young man stepped out – his hair crudely dyed black, with dark streaks running down his neck like shoe polish – and entered the store. Inside, glass display cases held candy, gum, tobacco and pocketknives. Groceries lined the shelves. A few firearms stood in racks above boxes of ammunition. A butcher block awaited use for slicing meat and cheese for sandwiches. Wooden bins held bolts, nails, rake teeth and machinery parts. A chest-style soda cooler offered bottles of pop.

Two customers were inside: Jack Ballinger, the local mail carrier, and Pete Jardine, a Burlington Railroad signal maintainer who lived at the depot and had stopped by before starting work.

Store owner Roy Graham greeted the young man and stepped outside to service the car. His large black German shepherd, Wolf, followed close behind, making the visitor visibly uneasy. As Roy pumped gas and washed the windows, he noticed a girl lying under a blanket in the front seat. Two guns – a shotgun and a handgun – lay near her. The young man paid in cash and drove off, heading west toward Alliance.

Something about it didn’t sit right. Roy jotted a note on a scrap of cardboard: Black Packard Sedan Nebr: 2-17415.

Inside the adjoining post office, Roy’s wife, Ramona, had just sat down at the roll-top desk with a copy of the Omaha World-Herald. That morning’s front page

carried a chilling headline: a teenage killer named Charlie Starkweather was on the run after a string of murders in eastern Nebraska.

Later that morning, the radio confirmed it – Starkweather had murdered the C. Lauer Ward family in Lincoln and was traveling in their 1956 black Packard. The license plate matched the number Roy had written down. He immediately called the police and state patrol, though conflicting reports placed the killer elsewhere. Starkweather went on to kill again near Douglas, Wyoming, before his arrest. For the Grahams and the people of Ellsworth, the memory of the morning a serial killer stopped in town never faded.

Though the Starkweather sighting may be the most infamous moment in the store’s history, it’s just one chapter in the long and layered story of this Sandhills landmark.

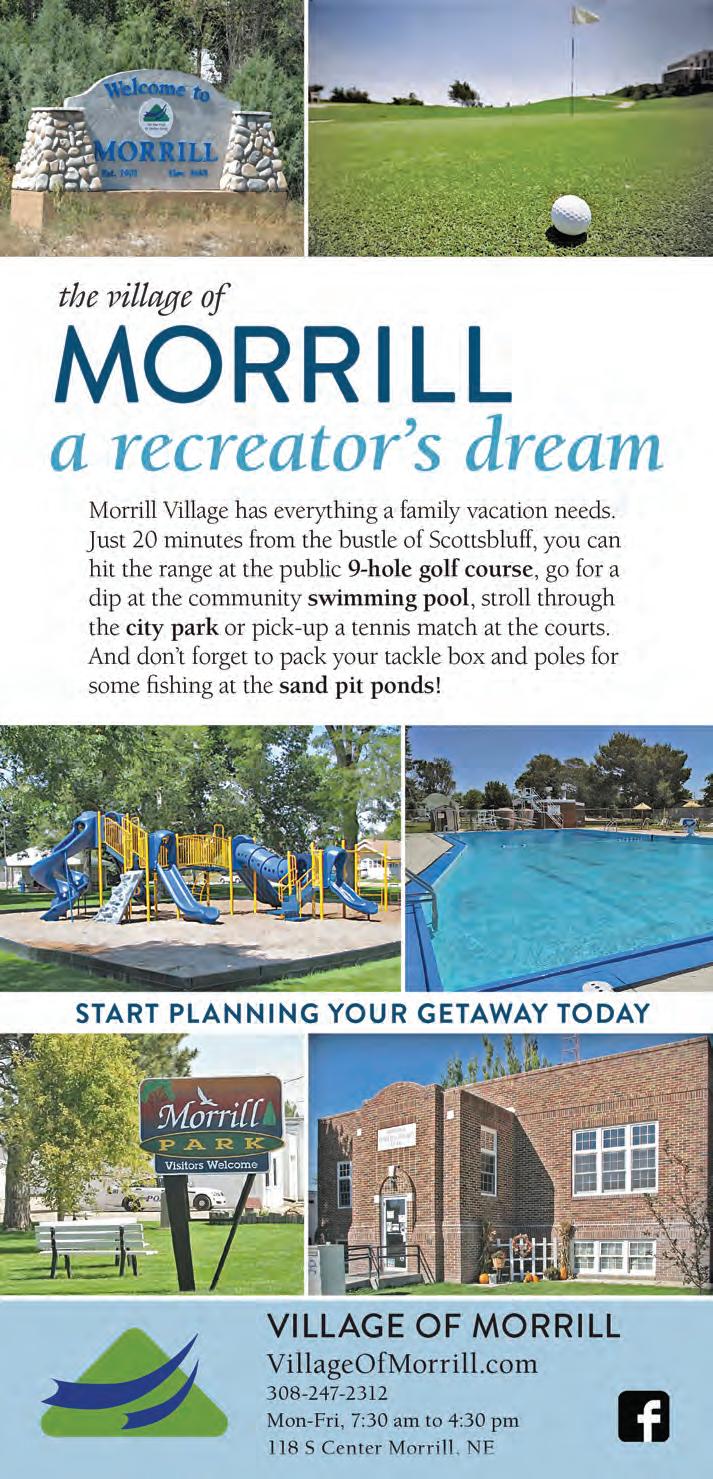

BUILT IN 1898, as part of the sprawling Spade Ranch operation, the store has served as post office, freight depot, general store, tack shop and local gathering place. More than a century later, it’s still open for business – and still connecting past and present in one of Nebraska’s most storied cattle towns.

On a windy, cool spring afternoon, the bell above the door jingles as a couple steps into the Ellsworth store, brushing back wind-swept hair and adjusting their jackets. “Hey guys, how’s it going?” Wade Morgan calls from behind the counter, his hands resting on the wooden candy case.

The couple nods and smiles, then meanders through the store. They linger over racks of denim and rows of boots, run fingers over tack, and pause at the shelf lined with Mari Sandoz books. They chat with Wade as they browse – swapping stories about highways and towns, the weather, and where they’re headed next. Wade offers suggestions, pulls down a pair of gloves to try, and they laugh over a story about a neighbor’s dog. Eventually, they settle on a sturdy pair of gloves and two bottles of water for the road.

“Thanks for stopping by,” Wade says as they step back into the wind, the bell chiming once more behind them.

Beyond being a stop for weary travelers, the store itself is a historical landmark. Constructed by Ferdinand Merritt and his sons, the store was part of the Spade Ranch complex. Founded in 1888 by Bartlett Richards and William Comstock, the Spade was one of the largest and most famous ranches in the nation, spanning more than 500,000 acres at its height in 1905.

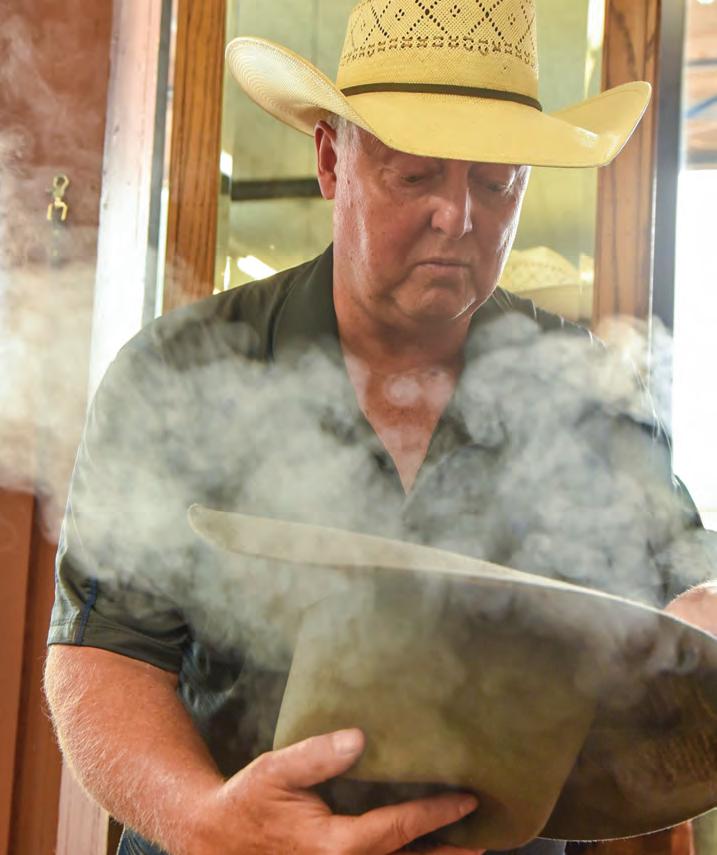

Owner Wade Morgan carries on the shop’s storied past. He sells everything from Winchester rifles, gear and supplies to books by Sandhills authors. He still does leather work too, handcrafting holsters and phone cases.

The wood-frame store, with its pressedtin ceiling, served as a vital hub for ranch hands and homesteaders. Before the post office addition on the north side, mail was sorted directly inside the store. Upstairs, store manager Bill Seebohm lived in a modest apartment. He helped load freight wagons that followed sandy trails 20 miles to the Spade Ranch headquarters.

The Nebraska Land and Feeding Company – later known as the Nebraska Stock Growers Association – made the store its headquarters in 1898. A large walk-in safe held ranch records. In a back room called “The High Private,” homesteaders filed for land claims. Across the street, weary travelers from the railroad could stay at a hotel also built by the Merritts. Spade cowboys and hay crews bunked there at no charge, gathering in the large basement room known as “The Bull Pen.” Stockyards to the east handled thousands of head of cattle shipped by rail.

The Spade Ranch’s fortunes began to wane in 1905, when Richards and Comstock were convicted of illegally fencing government land. President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration made an example of them, sentencing both to one year in prison. Richards died behind bars at age 49. Comstock returned to sell off assets, but by 1923 the ranch had collapsed. Banks foreclosed on its properties, including the store.

After sitting vacant, the store was purchased in 1927 by Abbott interests. Lawrence Graham took over management, moving in with his wife Hazel and their baby boy.

“My first impression of Ellsworth was not good,” Hazel later wrote. “I was a young woman with a 7-month-old baby, moving with my husband into a strange neighborhood, to manage a business we knew very little about.” The store was in poor shape – plaster falling from ceilings, rats and mice underfoot.

Then came winter – and a near catastrophe. Fearing the pipes to the railroad’s water tank would freeze, a coal chute attendant lit a fire beneath the tank. Flames spread to the store roof. In desperation, local men fired rifles at the water tank, riddling it with holes to release a torrent of water and extinguish the blaze.

BY SPRING 1929, Lawrence had cleaned and repaired the building. He added a south-side addition for machinery repairs, a lumber shed, truck scales and gas pumps.

The Grahams brought new life to the business and the community. On Christmas Eve 1931, they hosted a celebration in the street out front. A tall Christmas tree stood in the center, decorated with lights. Children received sacks of candy, fruit and nuts. Just after dark, sleigh bells jingled overhead, and Santa Claus appeared on the store’s roof, climbing down onto a parked truck. “The street was packed with cars and saddle horses and people,” Hazel wrote. “We all sang Christmas carols until a late hour.”

In January 1949, a fierce three-day

blizzard buried the town. Snow piled high enough to reach rooftops. Trains and roads were blocked for more than a week. Ranchers found supplies – and camaraderie – at the little store. Hazel wrote that the Grahams, and the community, endured together.

Lawrence bought the building in 1950 and operated the store until 1967. It sat vacant for three years before rodeo champion and former Spade cowboy Veldon Morgan purchased it in 1970. He renamed it Morgan’s Cowpoke Haven and launched a new chapter.

Veldon converted the old general store into a custom tack shop. “Dad was always inventing,” said his son, Wade Morgan, now the proprietor. “He made heavy-duty pack gear from nylon and Cordura.”

Among Veldon’s friends and customers were Slim Pickens, the rodeo cowboy turned Hollywood actor, and Walt Searle, editor of Hoof and Horn magazine. Slim, an avid elk hunter, helped test Morgan’s pack system in the mountains. The design used a saddle system secured with two cinches, a breast collar and a britchen to keep it from shifting downhill. Panniers carried the gear; a rain cover protected the top pack. “We sold all that as a unit,” Wade said.

The business took off. National publications featured Morgan’s gear. Cabela’s carried his products. At its peak in the 1980s, the company had 17 sales reps on the road and employed 80 people through the Ellsworth store. A second location opened in Hot Springs, South Dakota. By the 1990s,

It’s a step back in time

the Morgans were also manufacturing saddles – over 200 in a single year.

Eventually, Weaver Leather purchased the business and both buildings. Veldon signed a non-compete agreement, and in 1997 Wade bought the Ellsworth store back.

Today, Wade continues the family legacy. He added a secure room for firearm sales and still handcrafts leather holsters and phone holders. While saddle repair has mostly faded out, he rents space for boat and equipment storage and sells boots, hats, books by Sandhills authors, and supplies for hunters, ranchers and travelers passing through.

Not only do visitors appreciate the store’s inventory – everything from durable gloves and classic western wear to knives and sunglasses – they also value its deeper roots. The store itself carries a sense of history, with old photographs and movie posters on the walls and stories tucked into every corner.

One customer from eastern Nebraska said he often stops when he hunts northeast of Ellsworth. Warmly recalling the worn floorboards and familiar jingle of the bell over the door, he noted, “It’s a step back in time.”

And yes – there’s still pop and candy bars for sale just beyond the same wooden door that Charlie Starkweather once entered.

Look up, and you’ll still see the pressedtin ceiling from 1898. Underfoot, the wooden floors creak with age. A groove in a wooden post marks where Roy Graham used to keep his deli knife. The walls are filled with artifacts from the old Spade Ranch and early days of Ellsworth.

Morgan’s Cowpoke Haven remains well-stocked – not just with gear, but with history.

TIME STAYS IN

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Trains, wagons, boats and bins –these 5 quirky guesthouses are a blast from the past.

ACROSS NEBRASKA,

FIVE overnight stays offer more than a bed – they’re portals into the past. A banana-yellow Union Pacific train car lets guests sleep in a lofted cupola at Two Rivers State Recreation Area in Waterloo, while a floating riverboat rocks visitors to sleep on the Missouri River in Brownville.

Fairfield is home to prairie schooner wagons, Ainsworth welcomes car lovers to a vintage Conoco gas station and Seward boasts a guesthouse inside a former grain bin. Each offers a character-rich stay rooted in history – some even with wheels attached.

Some roll, some float and others stand still in farm fields, but all invite guests to slow down, look around and feel the history humming beneath their feet. These five overnight experiences offer some of Nebraska’s most memorable stays in time.

Union Pacific Caboose Park at Two Rivers State Recreation Area Waterloo $80

OutdoorNebraska.gov (402) 359-5165

TUCKED ALONG A bend in the Elkhorn River, Two Rivers State Recreation Area invites guests not just to visit railroad history – but to sleep inside it.

Ten banana-yellow Union Pacific cabooses with red trim rest on a final stretch of track. Once rolling bunkhouses for conductors and brakemen, these cabins now trade the clickety-clack of wheels for the calm of a good night’s sleep.

The caboose park honors a bygone era when Omaha served as headquarters for the first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. The term “caboose” comes from the Dutch word kabuis, meaning a ship’s galley – a nod to their early days as rolling kitchens and crew quarters.

Union Pacific began retiring cabooses in the 1980s and donated 10 to Nebraska State Parks in 1983.

Each sleeps up to six guests with twin, bunk and queen beds. The real draw? The lofted cupola – a raised lookout once used by train crews.

Michael Townsend, regional park director for Nebraska Game and Parks, recalls climbing into the loft as a kid. “Looking out at the park through what would have been the crew’s view is still a core childhood memory for me.”

The wood-paneled cabins feature modern amenities such as air conditioning, bathrooms, kitchenettes and running water. But they still retain their historic charm, even down to their exact Union Pacific paint codes.

Available for overnight bookings from April through September, these cabooses may no longer roll, but the memories still do – right up through the cupola.

PHIL FUCHS HAS been tinkering with cars since before he could drive. So when he and wife Marsha found a crumbling 1920s Conoco station in downtown Ainsworth, he didn’t see rust – he saw potential.

In 2016, the Fuchs transformed the relic into the Philing Station, a retro guest rental where visitors can now refuel in spirit, if not in gasoline.

The name is a wink at both the building’s past and Phil’s own. Step inside and it’s like flipping a switch to the 1950s: red diner chairs, green porcelain tile and Conoco signs line the walls.

Phil crafted a chandelier from antique automobile wheels, and the building’s old service bay – once a haven for grease and

socket wrenches – is now a vaulted bedroom with preserved brickwork. A uniform from a former station attendant, donated by a local, hangs inside.

“Everyone has a memory here,” Marsha said. “We’re working on getting a pop machine back in here – just like the one kids used after school.”

Residents have donated photos, rusting signs, playbills and memories of the station’s heyday. Guests who come to stay in the renovated gas station include road trippers, car lovers and anyone who appreciates a little nostalgia in the Sandhills.

The Philing Station no longer boasts horsepower under the hood – but its charm is running full throttle.

Spring Ranch Campground

Fairfield

$250

SpringRanchCampground.com (402) 726-2282

BEFORE IT BECAME a campground, Spring Ranch was a small but busy village on the Oregon Trail. Travelers followed the Little Blue River westward, stopping near high bluffs to water horses and rest. Today, visitors come for similar reasons – to find peace and perspective on wide, open land.

Here, guests stay in handcrafted wagons modeled after the sturdy Conestogas of the 1800s. Made from Amish-milled hardwood and topped with billowing canvas, these prairie schooners blend old-fashioned charm with modern hotel comforts.

Owen and Kim Nelson have lived on this land for 32 years and opened the camp-

ground three years ago. Their 240-acre property hugs Pawnee Creek and the historic Oregon Trail.

“The creek was a very sacred gathering place for Indigenous people,” Owen said. “We’ve found tomahawks, arrowheads –even part of a peace pipe.”

The original Spring Ranche (spelled with an “e”) lies two miles south. Burned in an 1864 attack and later rebuilt, it became a bustling town with a post office, sawmill and stores by 1870. Today, all that remains are cemetery stones – including one for Elizabeth Taylor, the only woman ever hanged in Nebraska.

The Nelsons keep the campground small: a cabin and teepee, wagons, yurts, trails and a whimsical water fountain flowing through an old truck grill. They live nearby and sometimes join guests around the campfire to trade stories.

River Inn Resort

Brownville

$150-$170

River-Inn-Resort.com (402) 825-6441

ALL ABOARD FOR a stay that floats. The River Inn Resort is a bed-and-breakfast moored on the Missouri River, just off the banks where Lewis and Clark once passed through.

Randel and Jane Smith launched their first riverboat in the 1970s, determined to preserve Brownville’s frontier-era spirit. Once a major steamboat stop, the town of nearly 150 is now a National Historic District.

In 2009, the couple opened the River Inn, just two minutes from antique shops and historic homes. Their son James and his wife Lisa now manage the floating inn and the Spirit of Brownville passenger boat, but the original dream still holds water.

Onboard, art deco touches, Italian leather furniture and the first deck lined with Adirondack chairs await. Guests sip wine and stargaze under the breeze.

Each stateroom curves with the boat’s frame and includes a public deck – perfect for scanning the river or watching bald eagles drift overhead. The inn, open year-round, hosts events like their popular Murder Mystery dinner party.

Memorial Day through early fall, guests can board the Spirit of Brownville, a 150-passenger paddle-wheeler, for dinner cruises, sightseeing or private charters.

The River Inn offers a rare luxury: unhurried time, gently carried by the current. Stay awhile, and let the river set your pace.

The Bin House at the Good Life Farm

Seward

$160-$450 Airbnb.com

ON THE OUTSKIRTS of Seward, a silver grain bin rests quietly on the Seevers’ family farm. Once packed with 10,000 bushels of corn, it now holds a spacious bedroom, fully functional kitchen and cozy living room perfect for a relaxing retreat.

John Seevers’ grandfather bought the land in 1930, and the family has worked it since. An 1898 farmhouse still stands nearby, hayfields and alfalfa stretch around it, and horses graze under the Nebraska sun.

After four decades teaching in Japan, John and Karen Seevers returned in 2017 to transform the idle bin into a guest retreat. “People don’t expect the interior,” Karen said. “Outside, it’s a grain bin. Inside, it’s a little surprise.”

The interior blends Midwest sensibility with Japanese influence: warm lighting, sleek stairs and Karen’s pottery and artwork from

their time abroad. The exterior auger remains as a nod to the bin’s farming roots.

Next door, guests can also stay in Grandma’s Guest House – a cozy farm home with original 1930s floors, rooster decor and front-porch charm.

Some guests ask what there is to do. Karen simply smiles: “Relax.”

Whether stopping off I-80 or gathering for a reunion, visitors find simple joys –walking trails, pondside sunsets, friendly barn cats and a warm welcome.

The grain may be gone, but the hospitality is beginning to sprout.

WHERE THE GRASS HOLDS STORIES

A decades-long journey into the Sandhills –and the trust earned along the way

story by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

photographs by ALAN J. BARTELS

Bartels has spent decades forming deep relationships with and photographing Sandhillers, such as the Switzer family, where Bruce Switzer is reflected in a tank on his family’s ranch in Loup County.

THE SANDHILLS BEGIN where the pavement thins and the ground thickens with prairie grass. In this 20,000-square-mile sweep of rolling dunes, cattle outnumber people and the rhythms of life are measured not in hours, but in seasons.

This land, once feared as uninhabitable, has long been home to some of Nebraska’s toughest and most devoted stewards – ranching families whose lives are intertwined with the grass beneath their boots. Over decades of traipsing these oil roads, twotracks and trails, Alan J. Bartels has come to know them – not just the landscape, but the people who call it home. In doing so, he’s glimpsed a culture defined by grit, grace and generational reverence.

Sandhillers salute the flag during Nebraska’s Big Rodeo in Burwell, the state’s official Outdoor Rodeo Capital. A blonde bull feeds on prairie grass in Custer County.

A lifelong Nebraskan and former editor of Nebraska Life, Bartels now works for the Lower Loup Natural Resources District and lives in Howard County. He first fell in love with the Sandhills after moving to Greeley as a teenager. His newest book, Secret Nebraska Sandhills: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure, which will be released in April 2026, explores the region not as a travel guide, but as a deep dive into its culture and lifestyle.

The Sandhills cover a quarter of the state, yet its nearly untouched, grass-stabilized dune fields are often overlooked. Much of the region was settled after the Kinkaid Act of 1904, and cattle ranching remains the primary industry – often through sixthand seventh-generation ranchers.

“These families would hate to fail those ancestors who homesteaded the land they now work,” Bartels said. “That weighs heavily on these folks.”

These values are ingrained in Sandhills cowboys, who live by the mantra: “If you take care of the land, the land will take care of you.” Making a living in the howling winds and sandy dunes requires unbounding resilience passed down through generations.

“There’s a romance with the land out there, but it’s realism,” Bartels said. “People are on horseback every day – not because it’s cool, but because in a lot of places, horses get around a lot better than a four-wheeler or a pickup.”

Joe McBride, owner of Ranch-Land Western Store in Ainsworth, steams wrinkles out of a well-loved cowboy hat. Golden prairie grasses rustle in the autumn breeze east of Ellsworth.

Sandhills ranchers are private people, but they appreciate when someone shows genuine interest in their remote way of life. “You’ve got to get to know them first before the camera even comes out,” Bartels said.

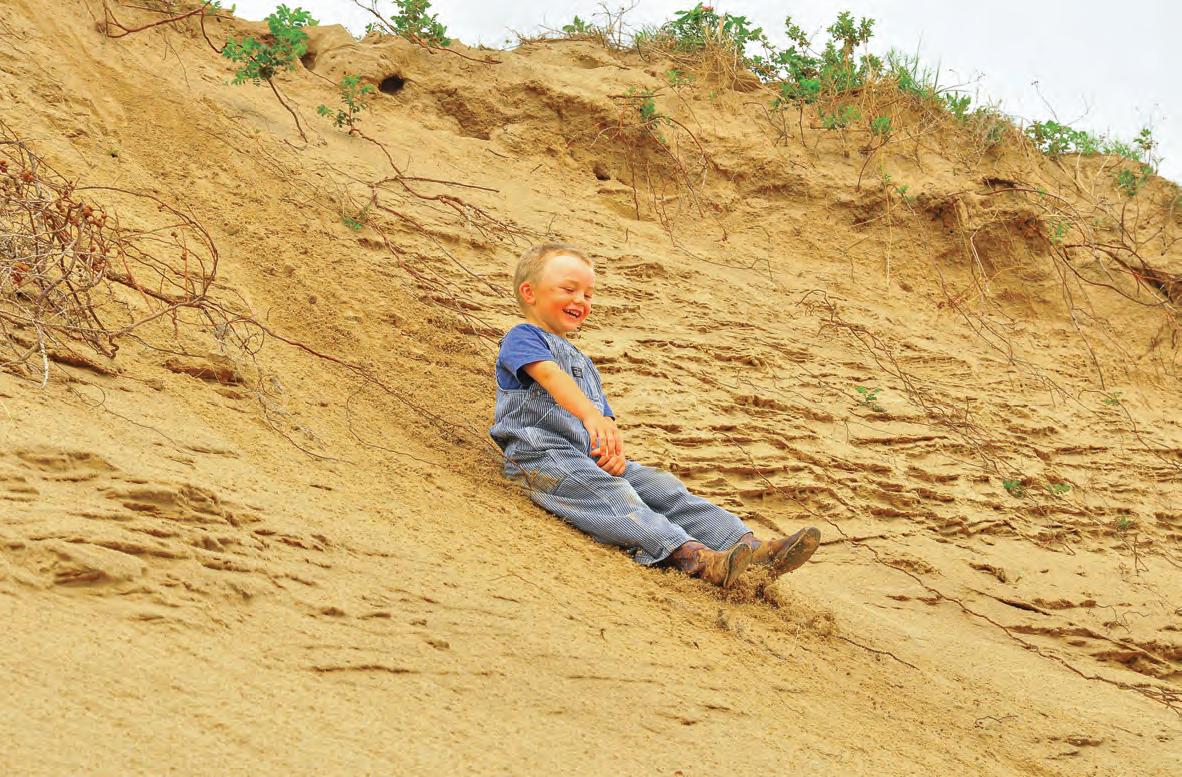

Over the last two decades, he’s become an honorary member of the Switzer family in Loup County and discovered a best friend in Bruce, a third-generation landowner. Bartels has returned year after year to photograph the family and eventually tell their story, capturing memories like “Kid Sliding in Blowout.” The whimsical image portrays Bruce’s grandson, Henry Sortum, at 5 years old; he’s now 17, and Bartels keeps in touch.

“The Switzers have allowed me into their family and onto their land, which for a Sandhills ranch family who appreciates their privacy, was probably not always easy for them to do… at least that’s my side of the story,” Bartels said. “But once you earn the trust of a Sandhiller, as long as you never break it, you’re friends for life.”

His photographs will be featured in a 50-piece gallery exhibition called “West Intentions” at the Carnegie Arts Center in Alliance from Sept. 30 to Nov. 15 – a visual portrait of life in the Sandhills. Nearly 200 images will also appear in Secret Nebraska Sandhills.

“Part of what fuels these adventures is that I don’t have that strong generational connection to a place like many Sandhillers do,” Bartels said. “But I appreciate theirs.”

He may not carry a family name tied to a pioneering deed, but Bartels’ lens has earned him something just as lasting: trust. In a place where friendships are forged through honesty, firm handshakes and promises kept, that trust is everything in sharing their stories.

Henry Sortum slides down a sandy blowout in Loup County at age 5. Left, each December, the Dry Valley Church north of Mullen fills with flickering light and faithful hearts – a moment of togetherness in the Sandhills.

At the lake, life takes on a different rhythm – unhurried, reflective, and deeply felt. From shore to shore linger stories that hold the steady current, hospitable weather, and stirring wildlife as backdrops. Our poets delicately wade in these memories and moments, making sense of the living landscape.

Eventide

Lloyd E. Friesen, Omaha

It’s eventide at this forest lake, and darkness is closing in.

A loon issues a mournful call, and an owl lets out a plaintive hoot.

Brief expressions of sorrow, perhaps, for day’s end.

Peace

Carla Ward, Grand Island

Near the edge of Kuester Lake I drink in the quiet chaos of nature.

Drab, speckled ducks, females, glide along the still waters puckering the surface like freshly sewn stitches.

The token drake, emerald neck haughtily stretched toward the sun, ushers his harem toward the shore.

A dragonfly hovers over the shallows before touching down, marring the blue reflection of sky with delicate concentric circles.

Hidden in the cottonwood’s branches cicadas buzz and pulse their frenetic chant chases all worries from my mind and the taut muscles in my neck uncoil.

Exhaling, peace enters my soul.

Lake Haiku

Vaughn Neeld, Cañon City, Colorado

saffron sun rises misty lake contemplates shore fish still lie asleep

marsh reeds stipple shore lines’ shadowy beaches fishermen choose lures

ripples gnaw pebbles sculpt river rocks into gems children grab treasure

hot sun shines splendor fresh fish fried crisply golden decorates my plate

Lake Seldom

Jean Keezer-Clayton, Holdrege

There is seldom enough water To measure, maybe enough For an ibis to wade delicate, Slow-measured steps.

Flood years, it can rise to fit The lake title, flaunting white Caps and a shoreline. Mama mallards lead duckling Parades as coyotes wait

Stealthy in the rusty marsh grass. And rabbits multiply like –Well, like rabbits.

Polished souls can hear God There in whispered duets performed By buffalo grass and big bluestem. Deer savor communion with sunWarmed mulberries.

Sunflowers do a joyful slow Dance bobbing in time to Gentle breeze rhythms.

Marshmallow clouds somersault Easy through the sky canvas. In this cathedral, close your eyes In prayer. Then open them again. And sing a loud hymn.

Memphis Lake, Nebraska

Jeff Lacey, Gretna

The catfish here are so wild when they break the surface! They flail against the glinting line and slap sunlight into a million splinters.

My life too is made of hidden waters like this; I too have been caught and danced wildly for mercy; I too have been released back into

the green world, newly aware I am breathing.

Come, Splash in the Creek with Me

Laura Hilkemann, Firth

Come, splash in the creek with me –Toss aside your socks and shoes. Pick a whole fleet of leaves From the overhanging trees And see how far our armada floats.

Scavenge for sticks, Bring branches and twigs, Then into the water we wade. Haul them over here, Because we’re beaver engineers Building a wooden blockade.

Find a faded fishing lure –It’ll be our pirate treasure. Bury it on the farther shore –We’ll be back for it later. Come, splash in the creek with me –Toss aside your socks and shoes.

SEND YOUR POEMS on the theme “In the Kitchen” for the November/December 2025 issue, deadline Sept.1, and “Tracks in the Snow” for the January/February 2026 issue, deadline Nov. 1. Email your poems to poetry@nebraskalife.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

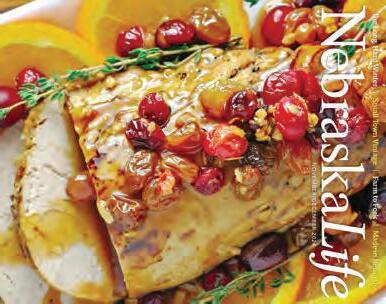

TSweet and Spicy Salsa

There’s nary a tomato in sight in these sweet takes on chips’ best friend

recipes and photographs by DANELLE

McCOLLUM

HERE’S NO RULE that says chips and salsa are required at all summer get-togethers, though one might be excused for thinking otherwise. No matter how much the menus vary at barbecues and potlucks, salsa is almost certain to make an appearance. There’s also no rule saying that all salsas must be tomato-based. These recipes prove that fruit and corn can tweak the salsa paradigm into something sweeter yet just as satisfying.

Fresh Pineapple Mint Salsa

Fresh pineapple and mint are combined with jalapeños and lime juice in this fruity salsa. Great with tortilla chips, it can also be served on grilled chicken, fish or pork chops. To save time, peeled and cored fresh pineapple from the produce section can be used. The salsa will keep 2-3 days in the refrigerator.

Combine all ingredients in medium bowl and mix well. Cover and chill at least 30 minutes, or until ready to serve.

2 cups fresh pineapple, diced

1 medium jalapeño, seeded and diced

1/2 cup chopped red onion

3 Tbsp chopped fresh mint

1 Tbsp chopped fresh cilantro

Zest and juice of one lime

Salt, to taste

Ser ves 6

Festive Fruit Salsa with Cinnamon Chips

Fresh berries and tart apples combine in this delicious fruit salsa that’s served with cinnamon-sugar-coated tortilla chips. The red, white and blue color scheme make it perfect for Fourth of July celebrations, but it is great for any summer barbecue get-together. The homemade cinnamon chips are easy to make, but store-bought cinnamon-sugar pita chips work well, too. The fruit produces a lot of liquid if it sits for long, so the salsa should be made shortly before serving.

Heat oven to 350°. Combine 1/8 tsp cinnamon and sugar in small bowl. Cut each tortilla into 6 wedges. Arrange wedges in single layer on 2 lightly greased baking sheets. Spray tortillas with nonstick cooking spray and sprinkle with cinnamon and sugar mixture; you might not need to use all of mixture. Bake 10-12 minutes, or until tortillas are golden brown, rotating pans once halfway through cooking time. Cool completely.

Gently toss blueberries, diced strawberries and apples in medium bowl. In small bowl, stir together orange juice and zest, brown sugar, strawberry jam and cinnamon. Pour over fruit and stir to coat well. Refrigerate until serving. Serve with cinnamon chips.

8 6-inch tortillas

1 Tbsp sugar

1/8 tsp cinnamon

1 ½ cups blueberries

2 cups diced strawberries

1 Granny Smith apple, peeled and diced

Zest and juice of one small orange

2 Tbsp brown sugar

1 Tbsp strawberr y jam

1/4 tsp cinnamon

Ser ves 12

Chipotle Corn Salsa

This easy-to-make corn salsa is fresh-tasting and delicious, much like the corn salsa at Chipotle restaurants. The recipe has the most visual appeal when using a mix of yellow and white corn, but any color may be used – just be sure to rinse and drain the corn well before adding the remaining ingredients. It can be used on tacos, burritos, enchiladas or as a side with tortilla chips. The salsa lasts up to a week in the refrigerator.

Combine all ingredients in medium bowl and mix well. Refrigerate until ready to use. Serve with tortilla chips, or in tacos and burritos.

2 cans corn, rinsed and drained

1/2 cup diced red onion

1 jalapeño, diced

1-2 Tbsp lime juice

1/3 cup chopped fresh cilantro Salt, to taste

Ser ves 8-10

WE’RE RAVENOUS TO taste (and publish) your favorite family recipes and stories that accompany them. Send recipes and stories to kitchens@nebraskalife.com or to the address at the front of this magazine.

The interpreter who Bright Eyes

won a people’s freedom

by RON SOODALTER

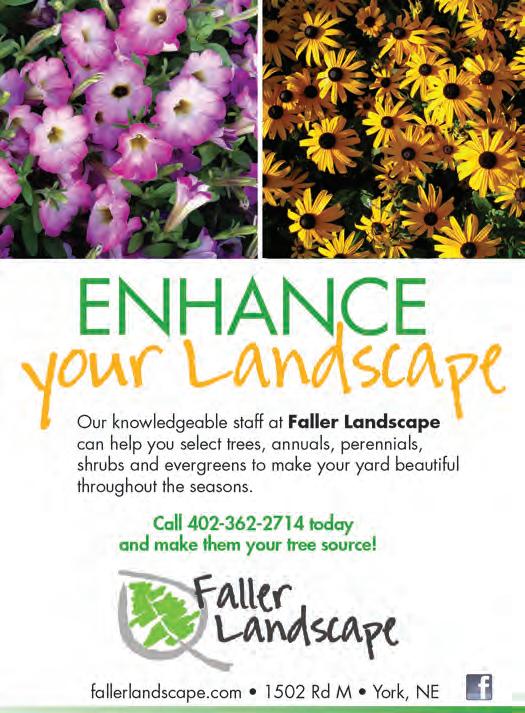

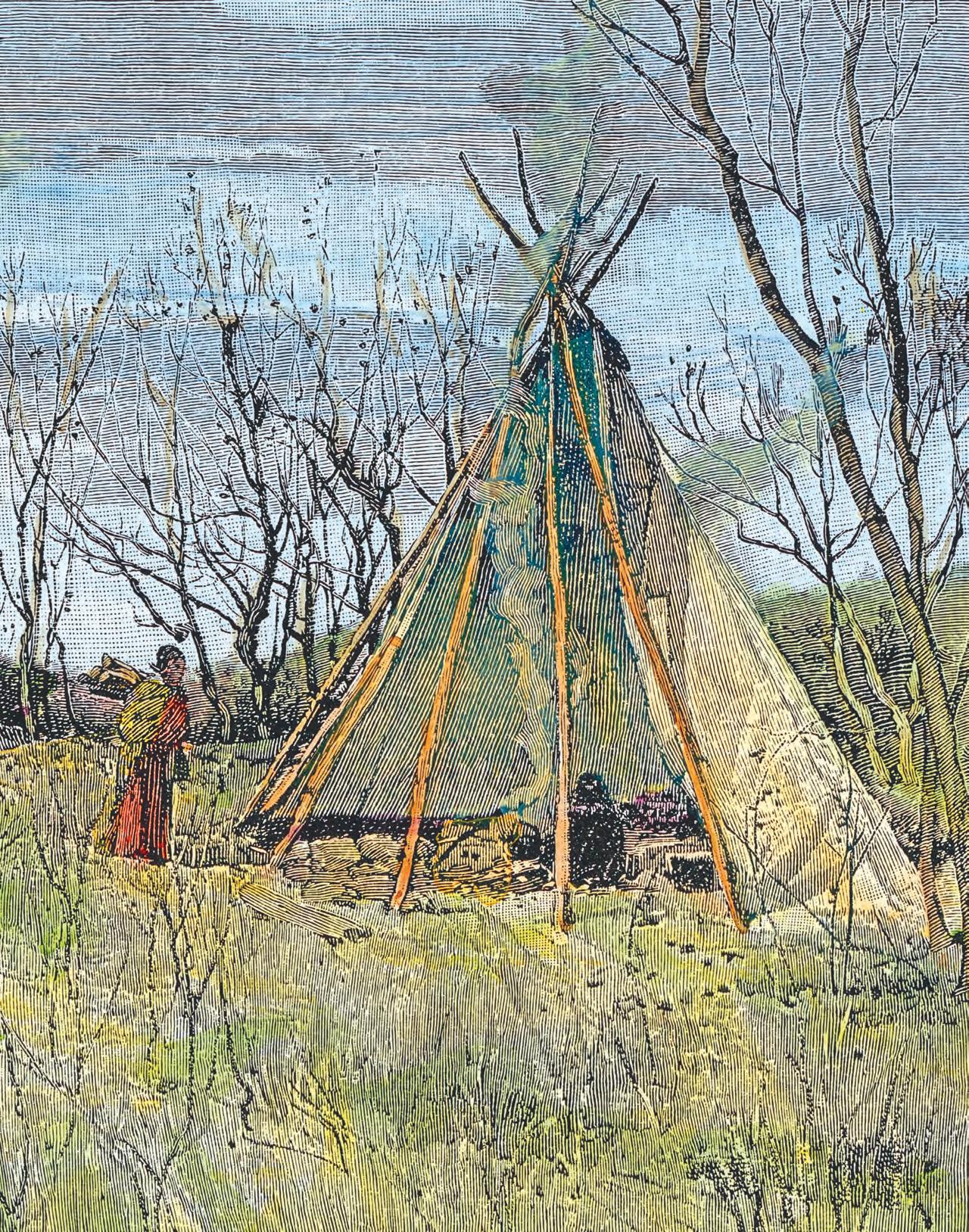

Susette La Flesche was born near Bellevue in 1854 and lived in a traditional Omaha earth lodge her first several years. Before moving onto their reservation, the tribe lived in lodges except during hunting trips, when they used tipis.

OMAHA, APRIL 30, 1879.

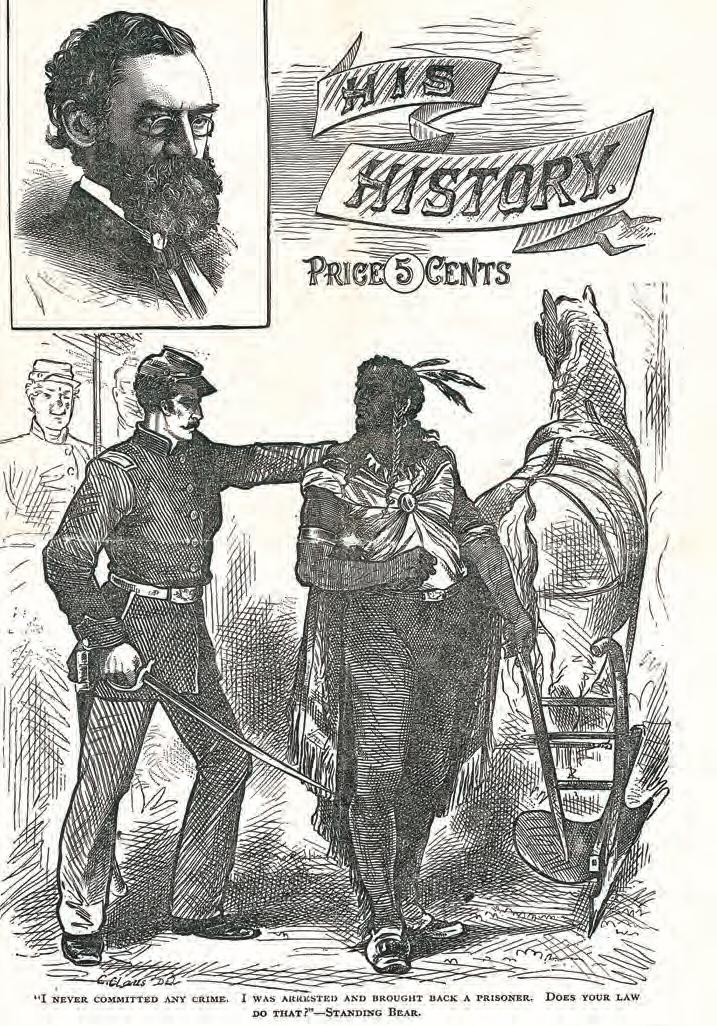

For two days, the lawyers for both sides had made their arguments, and now, last to speak, stood Ponca Chief Standing Bear. Imprisoned by the Army, he was suing to regain his personal freedom and to stop the govern-

ment from forcing him and his small band of followers to return to the reservation. The crowded courtroom grew silent as he made his dignified and impassioned plea to be treated as a free man and a human being in the eyes of the law.

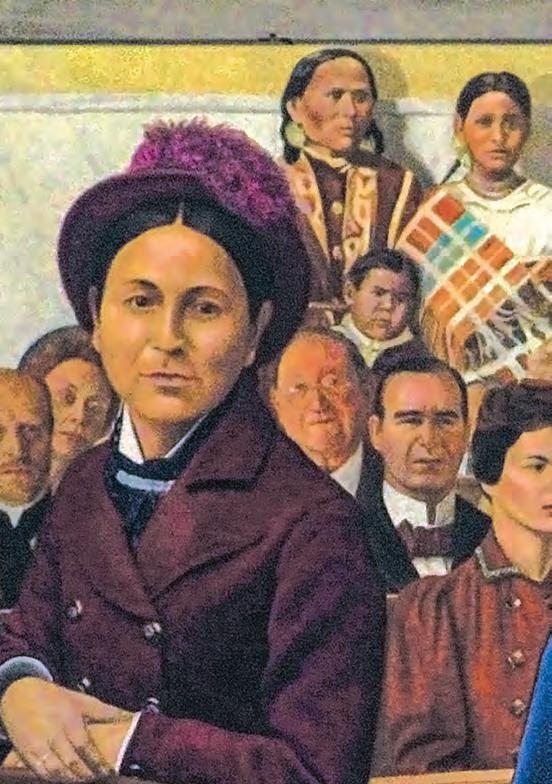

Standing near him, a self-possessed

young Indian woman from Bellevue carefully translated his words into English for the court. She had no way of knowing that her role in the courtroom that day would set her on a course fighting for better treatment of her fellow Native Americans and becoming an international celebrity before finally bringing her home.

The chief extended his hand toward the judge, and said, “That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both.” Many in the courtroom wept.

Eloquently framing the chief’s words, the interpreter told how the government – in flagrant violation of its most recent treaty with the Ponca – had given the tribe’s homeland to the Sioux, moving the chief and his people 500 miles south in a brutal trek that came to be called the Ponca “Trail of Tears.” Using Standing Bear’s words and her own, the diminutive but confident orator described the degrading life on the reservation, where the ground was not arable, and the promised government supplies often were substandard, late in coming or nonexistent.

Within two years of the forced relocation, rampant malaria, extreme weather and abysmal conditions had killed nearly a third of the tribe, including Standing Bear’s last remaining son, Bear Shield. With pain in her voice the interpreter related how the chief – honoring his son’s dying wish – tried to take the boy’s body home to the tribal burial grounds on the banks of the Niobrara. Placing his son’s remains in a coffin in the back of a wagon, he led a handful of his followers on a grueling march back to Nebraska, only to be detained by the U.S. Army and imprisoned at Fort Omaha.

THE INTERPRETER

The young interpreter was, in large measure, responsible for securing the chief’s day in court. Her given name was Susette La Flesche, and she was the daughter of a Ponca mother and the part-Anglo chief of the Omaha, Joseph “Iron Eye” La Flesche.

She was born in Bellevue in 1854, the year the Omaha gave up their land for reservation life. She grew up in a traditional Omaha earth lodge and acquired a solid education. She first attended the reservation’s mission school, and then the Elizabeth Institute for Young Ladies, a private school in New Jersey. At 19 she returned to the reservation and became a teacher in the government school.

Over the next few years she developed the writing skills she eventually employed to seek justice for Standing Bear and his people. Working with Thomas Tibbles, a crusading writer and editor for the Omaha Daily Herald, she garnered enough public sympathy and support for the chief’s plight to secure him a high-profile, pro bono legal team for a lawsuit against the federal government.

THE COURT’S DECISION

The government attorney’s case was simple: Indians were neither persons in the eyes of the law, nor citizens of the United States, and therefore could not bring suit against it. He argued that the Ponca were still living their traditional lifestyle and

During the trial of Standing Bear, La Flesche’s eloquent translations of the chief’s impassioned words caused observers in the courtroom to weep. After the 1879 trial, which was decided in the chief’s favor, La Flesche married former abolitionist and newspaperman Thomas Tibbles in 1882.

“Bright Eyes has accomplished more for the benefit of her race than their combined effort within my recollection.”

– Gen. George Crook,

Dec. 29, 1881

were completely dependent on the federal government, so they could not claim the privileges accorded to U.S. citizens. They were, he argued, non-persons.

In what would become a landmark civil rights case, Standing Bear’s attorneys argued that the tribe had adopted the ways of the whites, were trying to farm the poor soil of their reservation in Oklahoma and had eschewed tribal authority

in deference to U.S. law. The tribe’s legal team argued they were entitled to equal treatment under that law as guaranteed by the recently approved 14th Amendment, which gave citizenship to all people born in the United States.

After all the evidence and arguments had been presented and court adjourned, Judge Elmer Dundy – his heavy law books opened before him – deliberated for 10 days before stunning the nation by ruling that “an Indian is a person within the meaning of the law,” and as such, has a right to sue the federal government. Dundy went considerably further, ruling that the Army had no right to remove them to Indian Territory. Dundy’s most far-reaching decision held that the Indians “have the inalienable right to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ ” so long as they obeyed the law. He ordered that Standing Bear and his followers be released from custody immediately.

Ironically, although Standing Bear and his companions won in court, their new status as American citizens now precluded them from living on a reservation as wards of the government or occupying

land set aside for other tribes. Because the Sioux were still living on land formerly held by the Ponca, Standing Bear’s small band was restricted to making a home on three small islands in the Niobrara River. The chief’s victory proved bittersweet.

BECOMING “BRIGHT EYES”

After the trial, Tibbles scheduled a speaking tour for La Flesche and Standing Bear to publicize the plight of the Ponca. They traveled throughout the East, winning support from such luminaries and reformers as Edward Everett Hale, Wendell Phillips and Helen Hunt Jackson. Resplendent in traditional Omaha deerskin garb, La Flesche was billed as “Bright Eyes,” the English translation of her Indian name, Inshata-Theumba. She made a vivid impression with both her appearance and

her words. In 1880, she testified before a congressional committee looking into the Ponca removal.

In 1881, in large part due to La Flesche’s tireless efforts, the federal government returned to the Northern Ponca some 26,000 acres of their former lands – which originally stretched more than 200 miles – and awarded them $165,000 in restitution. The following year, La Flesche and Tibbles married on restored Ponca land and eventually took their speaking tour to Great Britain, lecturing before the nobility and literary giants of England and Scotland. On returning home, they continued their crusade. In 1891, the Army’s massacre of the Lakota at Wounded Knee drew them to South Dakota, where they conducted inquiries and publicized the poor conditions on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

La Flesche wrote for the Populist newspaper The American Nonconformist while living briefly in Washington, D.C., but soon moved home to Nebraska. Her health had long been failing, and in May 1903, she died at age 49 at her home near Bancroft. Eulogized by the U.S. Senate, the soft-spoken, self-assured Omaha woman had won international respect and acclaim as the first Native American lecturer and published writer, a pioneer teacher, activist and feminist, and an indomitable advocate for Indian rights. Her greatest claim to fame, however, was the dramatic role she played in helping a small band of Ponca gain recognition as human beings before the white man’s law. In 1983, Susette La Flesche Tibbles –Bright Eyes – was inducted into the Nebraska Hall of Fame.

The Doctor’s Work

ENDURES

In Walthill, the legacy of Bright Eyes and her sister lives on in a hospital with new purpose.

IN 1879, SUSETTE “Bright Eyes” La Flesche took the stand in a federal courtroom and helped secure a groundbreaking legal victory. Her voice helped establish that Native Americans were people under the law. Her sister, Susan La Flesche Picotte, carried that same sense of purpose into medicine.

Born in 1865 and raised on the Omaha Reservation in northeast Nebraska, Susan saw what happened when Native people were denied care. One moment never left her: a sick elder left to die after a white doctor refused treatment. “It was only an Indian,” he said. “It did not matter.”

Susan decided it did. In 1889, she graduated valedictorian from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, becoming the first Native American physician in the United States. She returned to Nebraska determined to care for all – Native or white. She installed clean water systems, cham-

pioned sanitation, made house calls at all hours and advocated for laws that would protect public health. In 1913, she opened her own hospital in Walthill – a space built by and for her people.

After years of restoration, the Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte Center reopened in June 2025. Today, the building she envisioned is once again a place of healing and hope. It houses a behavioral health clinic, artist co-op, museum, educational programs, a community garden and a maker space for regalia and beadwork.

“Dr. Susan’s past has built our future,” said Elizabeth Lovejoy Brown, the center’s executive director and a member of the Inkesabe Clan of the Omaha Tribe. “The community told us what they needed. So, we listened.”

That story continues far beyond Walthill. Claire Marsh and Meredith Wortmann – two cousins from Crofton’s St.

Rose of Lima School – spent nine months researching Susan’s life for a National History Day performance. They built sets, visited the hospital and stood in the very halls where she once walked.

“Being a Nebraska woman, it’s inspiring to see how she cared for her people and her community,” Claire said. “She treated everyone equally, regardless of race or gender.”

Their work earned them a spot at the national competition in Washington, D.C., where they shared Susan’s story at the University of Maryland and the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. “The more we researched, the more I felt like we knew her personally,” Meredith said. “She’s become a part of us.”

She once walked dirt roads with a lantern in hand. Today, her light burns on – in every patient helped, every story told and every young woman who follows her lead.

BANCROFT

John G. Neihardt State Historic Site, p 56

BAYARD

Chimney Rock State Historic Site, p 55

BOYS TOWN

Boys Town Visitors Center, p 54

CHADRON

Museum of the Fur Trade, p 55

FORT CALHOUN

Washington County Museum, p 55

FREMONT

Louis E. May Museum, p 55

GRAND ISLAND

Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer, p 58

HENDERSON

Henderson Mennonite Heritage Park, p 57

KEARNEY

Museum of Nebraska Art, p 56

LA VISTA

Czech and Slovak Educational Center and Cultural Museum, p 57

OMAHA

Durham Museum, p 58

RED CLOUD

National Willa Cather Center, p 56

SAINT PAUL

Museum of Nebraska Major League Baseball, p 54

SEWARD

Nebraska National Guard Museum, p 56

WEEPING WATER

Weeping Water Valley Historical Society/ Heritage House Museum Complex, p 58

YORK

Clayton Museum of Ancient History, p 57 Wessels Living History Farm, p 57

MUSEUM OF THE FUR TRADE

See the history of the first business in North America–The fur trade

UNIQUE ITEMS TO VIEW!

John Kinzie’s gun

HBC officer’s sword

Brass handle cartouche knife

William Clark fabric samples Chief’s coat

Kit Fox Society lance

Russian American Co. note

Oldest dated trap 1755

Parchment HBC officers certificate

Andrew Henry’s leggings

Open 8 a.m.-5 p.m., May 1-Oct. 31

3 miles east of Chadron, Nebraska on US Highway 20 www.furtrade.org

308-432-3843 • museum@furtrade.org

Explore ancient Rome, the Near East and more. Includes a children’s interactive play area. A new exhibit, Rise of the Greeks, highlights the ancient culture that shaped Western civilization.

ADMISSION IS FREE

Check website for hours

Call for group tours.

ClaytonMuseumOfAncientHistory.org

402-363-5748 • 1125 E 8th St • York

Paid for in part by a grant from the York County Visitors Bureau

Lower level of the Mackey Center on the York University campus

Explore our exhibits featuring the Immigration Room, Music Room, Sokol Room and Josef Lada calendars from the 1940s.

Our gift store offers many beautiful Bohemian items from the Czech land.

8106 S. 84th St. • La Vista

TAKING TO THE ROAD FOR FOOD, FUN AND FESTIVITIES

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

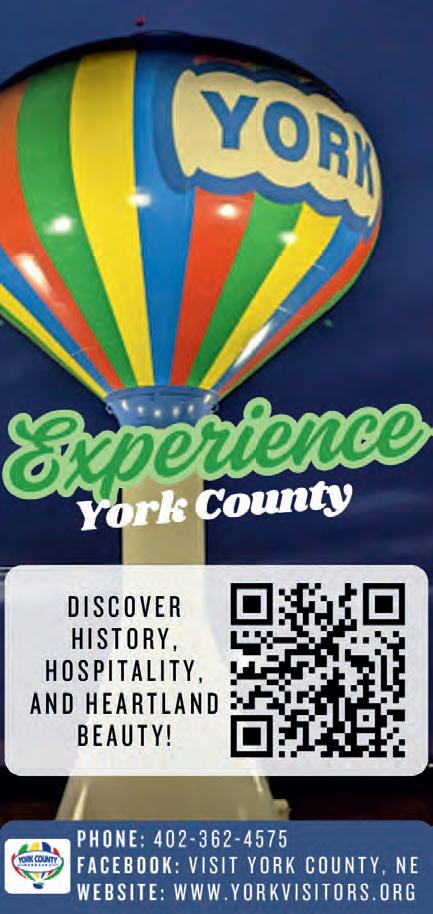

OUTDOOR COWBOY TRAIL 30TH CELEBRATION

SEPT. 5 • VALENTINE

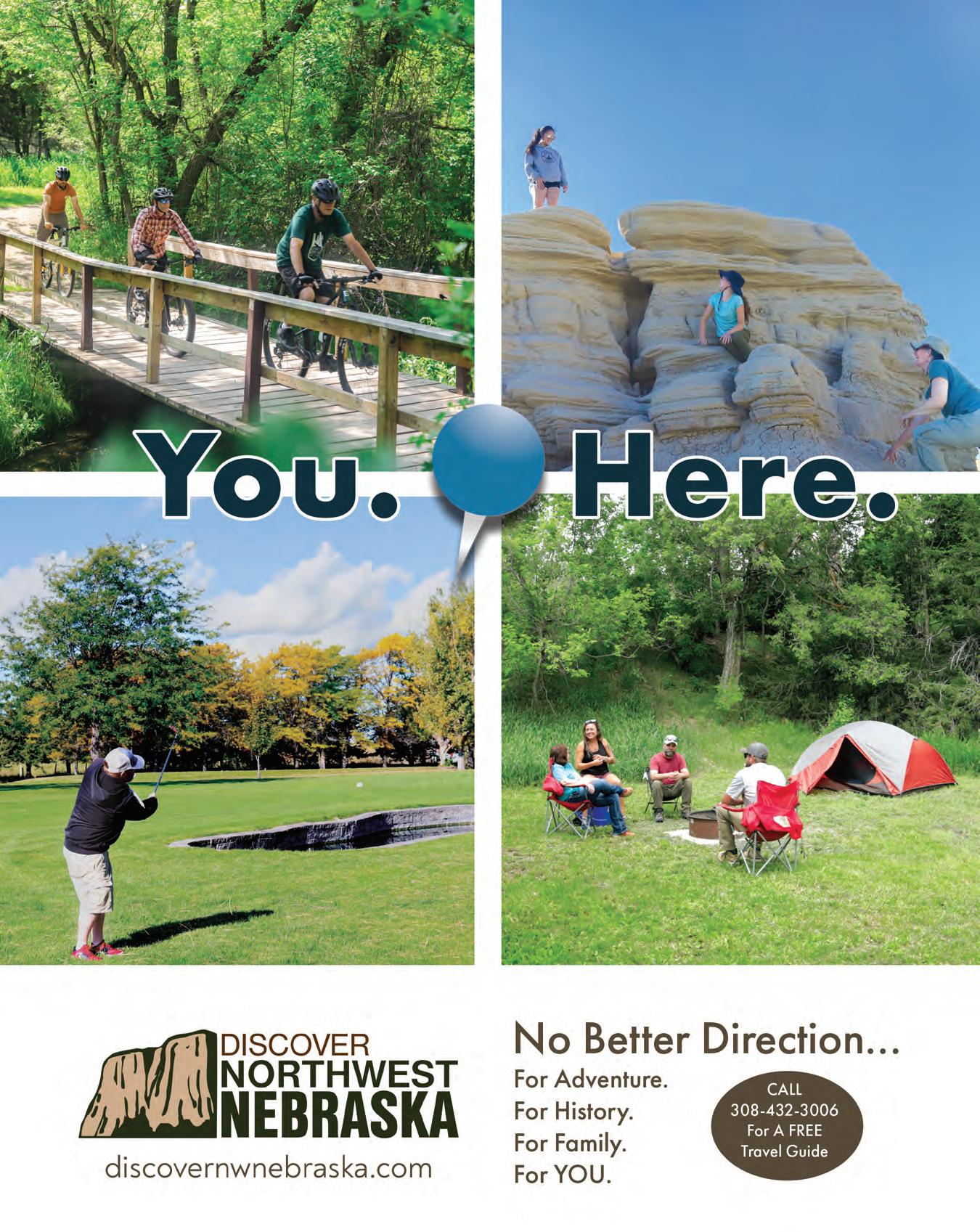

For 30 years, hikers, runners, bikers – and even a few cowboys – have traveled the limestone pathway that winds 317 miles across northern Nebraska. The scenic Cowboy Trail connects 30 rural communities from Norfolk to Chadron and has become a symbol of Great Plains grit.

Established in 1995, the trail is one of the largest Rails-to-Trails projects in the nation, transforming abandoned rail lines into a public walkway. So far, 187 miles have been developed between Norfolk and Valentine, and another 15 miles between Gordon and Rushville.

Reminders of Nebraska’s railroading days still line the corridor. Telegraph poles have been repurposed as mile markers, weathered depots stand where trains once stopped – and more than 200 bridges span creeks and rivers along the route. The trail’s highest point is just southeast of Valentine, where a bridge stretches a quarter mile

across the Niobrara River and towers 148 feet above it.

On Sept. 5, Valentine will celebrate three decades of trailblazing with a Cowboy Trailstyle party. The day begins at 9 a.m. with a trail ride. Cyclists can choose a 16-mile ride to Arabia Ranch, where a shuttle will return them to town, or make it a round-trip.

Afterward, a hearty dinner will be served from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Valentine Trailhead Park picnic shelter: prime rib, cheesy hash browns, salad, dinner roll, tea and water. Space is limited – RSVP by Aug. 15.

The day wraps with a free evening social from 7 to 8:30 p.m. on the Cowboy Trail Bridge. Bolo Brewing of Valentine will be pouring local brews. Proceeds from the event support trail improvements, including a bike fix-it station and new kiosk.

From steel rails to bike spokes, this trail carries a legacy worth toasting. Learn more at outdoornebraska.gov.

WHERE TO EAT OLD MILL

Wood-fired pizza is the star here, with sandwiches, breakfast and housemade desserts rounding out the menu. Browse the bulk goods section while you wait. 704 E. C St. (402) 376-8034.

WHERE TO STAY MERRITT TRADING POST RESORT

Lakeside cabins offer a relaxing summer retreat on the shores of Merritt Reservoir. Family-friendly and outfitted with modern comforts. 88337 Nebraska Hwy 97. (402) 376-3437.

WHERE TO GO

LITTLE OUTLAW CANOE, TUBE AND KAYAK RENTALS

Family-run for nearly four decades, Little Outlaw has everything you need for a float on the Niobrara. Paddle or tube the gentle currents for a classic summer adventure. 1005 E. US Hwy 20. (402) 376-1822.

The scenic Cowboy Trail celebrates 30 years in September with a 16- or 32-mile trail ride, outdoor dinner and social hour on the Valentine section of the pathway.

SEASONAL DUSTY’S PUMPKIN FEST AT THE

CODY’S

WEEKENDS IN OCTOBER • NORTH PLATTE

Each October, the wide lawns and golden fields of Buffalo Bill State Historical Park transform into a fall playground. Hosted at Scout’s Rest Ranch – the historic home of Buffalo Bill Cody – Dusty Trails brings a wagon-load of autumn cheer to North Platte each year.

Now in its eighth year, this family-friendly fest runs every Saturday and Sunday from 12 to 6 p.m. through Oct. 31. Admission is $14 on Saturdays, $12 on Sundays, and includes access to all activities, a short horseback ride and entry in the Duck Race – where one lucky duck wins a door prize.

Festivalgoers can try axe throwing, pan for gold, zoom down a giant hay slide or

launch a corn cannon. Zip lines, bumper balls and a bounce-through corn maze keep the action going, while a petting zoo, pony rides, cornhole and giant Jenga offer tamer fun. A snow cone truck and delicious concessions keep young “punkins” fueled for the day.

A highlight is the horse-drawn wagon ride through the 25-acre ranch, ending at a pumpkin patch where guests can pick their own gourds. Be sure to snap a photo with Rue, the dwarf horse, or Damoska, the farm’s 3,000-pound ox.

Whether you’re after fall nostalgia or family fun, Dusty’s Pumpkin Fest delivers a hearty harvest wrapped in Western charm. dustytrails.biz • (308) 530-0048.

WHERE TO EAT NORTH 40 CHOPHOUSE

Fine dining meets downhome hospitality at this polished steakhouse, known for its dry-aged Nebraska beef, live lobster tank and curated wine list. Live music plays Wednesday through Saturday. 520 N. Jeffers St. (308) 221-6688.

WHERE TO STAY HUSKER INN

This red-brick mom-and-pop motel offers a warm welcome, comfy beds and a central location within walking distance of downtown North Platte. 721 E. 4th St. (308) 534-6960.

WHERE TO GO GRAIN BIN ANTIQUE TOWN

Just south of North Platte, 20 historic grain bins form a boardwalk village in the canyons. Inside: antiques of all kinds, from tin signs and farm gear to cow skulls. 10641 Old Hwy 83 Rd. (308) 539-7401.

OTHER EVENTS YOU MAY ENJOY

SEPTEMBER

Honeybee Festival

Sept. 13 • Auburn

In 1974, a group of Auburn third graders campaigned to make the honeybee Nebraska’s state insect. Their efforts took flight – and now, Legion Memorial Park will buzz with activity for the festival’s debut. Visitors can observe a working hive, watch demos from the UNL Bee Lab, enter a honey-themed cookoff, or join a 5K or half marathon. 1015 J St. (402) 274-3521.

The Heirloom Market

Sept. 19-20 • Gering

Camp Heirloom returns for its ninth year at the Five Rocks Amphitheater. The popular market gathers artisans, shoppers and food trucks beneath the bluffs for two days of handmade goods, live music and creative connection. 2505 D St. theheirloommarket.co

Missouri River Expo

Sept. 20-21 • Ponca

Now in its 20th year, the largest outdoor expo in the Midwest packs more than 100 free activities into two days at Ponca State Park. Try kayaking, archery, wildlife viewing, fishing, camping skills, cooking demos, crafts and more. 88090 Spur 26E. (402) 755-2284.

Tractors and Treasures Flea Market

Sept. 20-21 • Steele City

A green John Deere tractor leads the Antique Tractor Parade through downtown Steele City, where history comes to life with tractor pulls, live demos, food trucks, vendors and a bounce house for the kids. 200 W. Main St. fairbury.com

Pumpkin Patch Season

Sept. 20-Oct. 28 • Avoca

Bloom Where You’re Planted Farm opens

for the season. $10 admission includes hayrides, a 40-foot tube slide, bronco barrel swings and ag exhibits. And of course, plenty of pumpkins to pick. 911 108th St. (402) 840-2207.

Fall Flea Market

Sept. 27-28 • Brownville

A tradition since 1957, Brownville’s riverfront flea market draws thousands to browse more than 250 vendors. Shop antiques, art, homemade goods, plants, furniture and more. 217 Main St. brownvillehistoricalsociety.org

History in Action Day

Sept. 28 • Chadron

Dawes County Historical Museum hosts live demos of butter-churning, leatherwork and buggy rides. Don’t leave without a slice of homemade pie. 341 Country Club Rd. (308) 432-4999.

OCTOBER

Eek at the Creek

Oct. 11 • Waverly

No tricks – just treats. Candy, hayrack rides, free hot dogs and popcorn at the Camp Creek Threshers grounds. Costumes encouraged. 3-5 p.m. 17200 Bluff Rd. (402) 786-3003.

Harvest Music Festival

Oct. 11 • Lincoln

Five Nebraska bands take the stage at The Royal Grove for the third annual music fest. Expect a mix of country and rock. 340 W. Cornhusker Hwy. (213) 332-6452.

Oktoberfest

Oct. 17 • Nebraska City

Celebrate Bavarian-style at Steinhart Lodge with traditional German fare, beer steins and live polka from the Polka Police. Festivities begin at 6 p.m. 121 Steinhart Park Rd. (402) 873-8717.

Pumpkin Carvers Event

Oct. 18 • Burwell

From 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., transform pumpkins into jack-o-lanterns. Stick around for trick-or-treating from 5-10 p.m. at Calamus State Recreation Area. 42285 York Point Rd. (308) 346-5666.

Czechfest

Oct. 19 • York

Feast on roast pork loin, Czech wieners, dumplings and sauerkraut – then dance it off with traditional music and an accordion jam with Angie Kriz and the Polka Tunes. 3130 Holen Ave. (308) 380-7225.

Downtown Trick or Treat

Oct. 24 • Madison

Main Street turns sweet as local businesses and the Chamber hand out candy to costumed kids from 5-6 p.m. (402) 454-2251.

Children’s Entrepreneur Market

Oct. 25 • Omaha

Pumpkins, costumes, movies and kid-powered businesses collide at “It’s Fall Y’all!” Held at Omaha’s RiverFront, over 6,500 patrons shop amongst young vendors ages 5-17 for handmade goods, treats and crafts. 1302 Farnam St.

The Great Gatsby Ballet

Oct. 29 • Norfolk

Experience the glitz and heartbreak of the Roaring Twenties in The Great Gatsby, a new Broadway-style ballet by World Ballet Company. Featuring 40 international dancers, an original jazz-inspired score, acrobatics and opulent visuals, this 2-hour production brings Fitzgerald’s iconic tale to life at the Johnny Carson Theatre. For ages 8 and up. 801 Riverside Blvd. (888) 469-1011.

TRIVIA ANSWERS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 b.

15