A CYCLE SAFARI

author Gareth Trewartha artwork Nikolaos Kourmatzis coordinator Valantis Nangoloudis communications Giorgos Ioannidis layout Antonis Karanaftis illustrations Dimitris Lagos and Gareth Trewartha proof-reading Angelos Grollios

1st edition in Greek March 2014 ISBN 978-618-5067-25-0

Myrsini Samaroudi for her love and support, Yolanda Kogianni and Sokratis Pavlidis for the word processing, Asterios Koukoudis for his suggestions, Angelos Grollios for proof-reading and corrections Dimitris Lagos for the illustrations, as well as dear friends for their interest and encouragement

In this book we read about a little boy’s adventures and what his experiences teach him about the human condition. The child attempts to reconcile the contradictions of his life in East Africa: the magical beauty of nature is at odds with the human ugliness of racism and injustice that is apparent everywhere he looks. Through his eyes we get a strong impression of the false sense of superiority that allowed colonial rulers to behave without any concern for the natural wealth and human cultures that their rule was destroying. However, this boy learns that respect and compassion are qualities that allow us to transcend the limitations our surroundings sometimes impose on us.

In the beginning of this story, it is the little cyclist’s family that set an example of generosity of spirit for him to absorb as he grows up. He watches as his grandmother treats everyone with kindness, and her loving influence does not fail to sweeten his nature; his grandfather, as paterfamilias, is also influential, setting standards of understanding and respect that are far superior to the usual colonial attitude to the native people. His mother, as she adjusts to a way of life that is continually in flux, shows him that we need to be flexible in our dealings with the world; his father, who, of necessity, seems to support the ethos of the colonial society, is, at the same time, a humane and tolerant man.

In contrast, the boy’s uncles exemplify a different way of thinking: they assert their manhood through hunting and killing the beautiful wild creatures that the little boy tries to protect. Their attitude repugnant to us now, and to our hero, then makes them reverse role models to the little boy in our story.

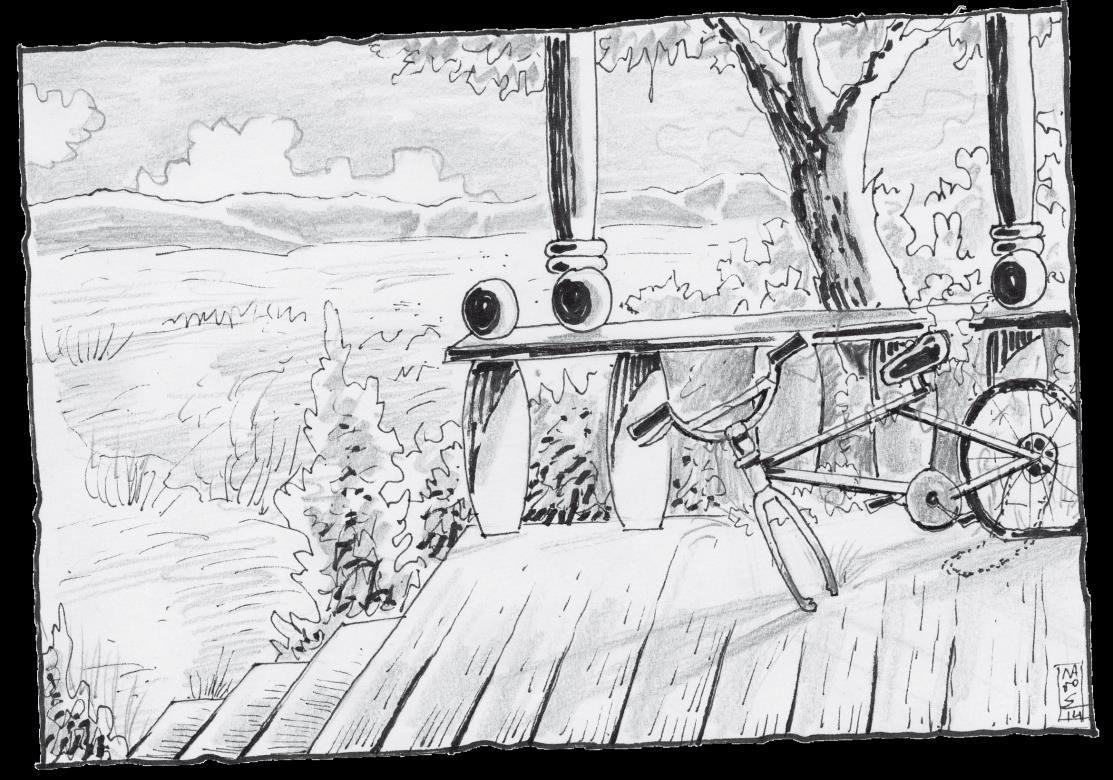

From an early age the boy asserts his independence, and his bicycle is his escape vehicle. He explores the wilderness and meets the local people on his own terms. These small excursions transform him and set him on a lifelong journey based on a belief in justice and kindness between people. These first forays into the wild awake in him a love for nature and an intuitive knowledge of her power that will stay with him always.

Melina SamaroudiAdding my brush strokes to the Tanzanian backdrop, I paint scenes from the first twelve years of my life. Everything I experienced there as a child the landscape, the wildlife, my adventures and the living conditions on my grandfather’s estate where I grew up, not to mention our travels, the safaris we went on, and the different African countries my father’s work sent us to they all left their mark on me. And there was also my grandmother, who played a pivotal role in my upbringing, her teachings influencing and shaping my personality.

The bicycles I had in those early years feature in some of the stories I’m about to relate to you. They gave me the chance to venture secretly into the wild, they took me to places I could never have visited otherwise, and carried me, protected only by my childish innocence, close to the potentially dangerous creatures that lived there. A bicycle was what brought me into contact with the indigenous people, though this was against all the codes of colonial rule. I lived in true freedom then, without any physical fetters, and with a mind unrestricted by prejudice.

From a young age I was aware of the injustice, inequality and greed that colonialism brought to Tanzania and I rejected the attitudes and conduct that supported them. I felt that threatening clouds were gathering over Africa and I didn’t want to betray her; I wanted somehow to protect and keep the land, the creatures and the people safe.

I hope that through the stories that follow I will manage to paint a vivid picture of the experiences of a child in an Africa that is lost forever.

It was love at first sight: he saw her running errands in Arusha on her bicycle. She was reputed to be the prettiest girl in town and enjoyed the admiration of the region’s entire European male population. The efforts of many young men to approach her and to flirt with her, however, proved fruitless. He began a campaign to win her heart. He would often see her looking adorable in those daring shorts she wore for cycling. He tried to follow her on foot several times but she always managed to slip away on her bicycle. Eventually, he was able to meet her at a party held at the Greek Community Club. Their first dance resulted in a wonderful romance that led to their marriage in 1951. I was born nine months later!

My father had arrived in East Africa in 1947, after the Second World War, to train as a civil engineer in a construction company. For a short time he served in a special corps of the Tanganyika Constabulary, which protected European settlers during the Mau Mau uprising. There were atrocities on both sides. My father never spoke about this experience. I suppose he was deeply scarred by seeing and doing things that no young man should have to see or do.

My mother was born in Tanganyika, the only daughter of four children. Consequently she was spoilt and enjoyed a lot of freedom for a young European girl growing up in Africa. She was a devoted fan of Hollywood movies and stars like Cary Grant, Tyrone Power and Gary Cooper, but her favourite was Alan Ladd, whom she dreamed of marrying one day! Alan Ladd did actually visit East Africa, and when she heard the news she made every effort to get in contact with him. She even managed to meet him. She kept a souvenir of this short ‘romance’, a photo of the star emblazoned with his autograph, but fate had other plans for her. Waiting in the wings there was another young man, who, as it happened, looked a lot like Alan Ladd. It was my father!

The estate lay between Arusha and Moshi. It was vast, the land reaching to the horizon, as far as the eye could see. It was bordered on one side by savannah and on the other by low-lying hills with coffee plantations. Nature filled in the gaps left by any uncultivated land with acacias and baobab trees. In the distance, the majestic Mt Kilimanjaro dominated the landscape like a huge shadow, its summit hidden, laced by clouds.

The house stood on a small hill in the midst of an extensive garden planted with tropical trees and plants. The flowers attracted the attention of numerous butterflies and exotic insects. The garden was a riot of colours and vibrant life: a testament to the loving care that was bestowed upon it. The house had large windows and a huge verandah all along the front. Nearby were a guesthouse, a large storehouse and a small hut where the askari(*1) lived. At the rear of the house were a productive vegetable garden, the laundry room and some storage spaces. There were five members of staff, all male: a cleaner, a person to see to the laundry, a cook, who was Grandma’s right hand in the kitchen, a gardener and our trusty askari.

Grandma was in charge of all the staff, and she not only oversaw all their duties but also took part in all the work because she believed that everyone worked better if she did so. The manicured grounds, the sparkling cleanliness of the house and the harmonious working relationships were evidence that she was absolutely right in her belief. Everyone loved Grandma and respected her.

When Tanzania(*2) gained independence, almost all the land owned by Europeans was nationalized.

(* 1) guard in Swahili

(* 2) After Tanganyika gained independence, it was united with the island of Zanzibar and renamed Tanzania in 1964.

As a little boy on my grandfather’s estate in Tanzania, my favourite mischief was to escape from the comparative safety of the farmhouse garden on my bike. I longed for adventure amongst the sisal(*3) and coffee tree plantations, daring to travel even further afield to where danger lay waiting in the wild, those places where the beasts rightfully sought to reclaim their ancestral lands, which had been stolen by the settlers.

My cherished bicycle became my friend and companion. Together we travelled everywhere, even coming within sniffing distance of prides of lions, which lazily raised their heads when they saw us pass by along the dirt roads, leaving behind us a cloud of dust. On these occasions, I felt both scared and thrilled and my bike and I rode speedily on without stopping. I knew that there was always a risk that one of the lions would chase us, but my bike lent me courage and strength and I was confident I could escape from any possible attack. It was really exciting!

Sadly, the time came when we had to leave Africa. It was a tragic and traumatic experience. Not only did I leave behind my homeland, but also the vastness of the estate, the breathtaking wildlife, the endless horizon and the beloved bike that had literally become my best friend, protector and supporter in my countless rides and adventures. But when I left Africa, above all, I lost my freedom.

One of my favourite bike rides took me to the muddy river where lots of wild animals were to be seen quenching their thirst. So visiting the river was always full of incident. I might see a hippo swimming, seemingly unaware of my presence, or perhaps a herd of gazelle quietly drinking from the riverbanks. Of course, such places are not without danger, so I kept my visits clandestine and never mentioned them to my family.

There had been clues as to my whereabouts: both my grandmother and mother noticed that I often returned home barefooted. ‘Where have you left your shoes?’ they would persistently enquire. I preferred not to lie, so I chose to remain silent on this matter. They were right to be concerned about my frequent loss of footwear.

Whenever I went to the river, I would leave the bike at the top of the hill and descend on foot to the riverbank, the slope being too steep to negotiate on two wheels. Beside the river there was a large acacia tree in whose shadow I would sit, remove my shoes and splash my feet in the water. Then I would carefully place the shoes on the water’s surface and watch them drift away with the current, like little boats. I observed that at first the shoes moved slowly on the water, but once they reached the middle of the river they would speed up, floating faster and faster away until they disappeared from view. I managed to lose several pairs of shoes while entertaining myself in this way.

Inevitably, however, my secret was eventually exposed and my visits to the river came to an abrupt end. One day I set off as usual, but, unbeknownst to me, my mother was on my trail. I left my bike on the hill as I normally did, went down to the riverbank and settled in my favourite position beneath the acacia. As I collected stones to throw into the water, I heard a sweet voice calling me: ‘Come here, my boy; I want to show you something. Don’t run, just come, come!’ To my astonishment I saw my mother standing next to my bike on the hill as she beckoned me to climb up and go to her. Almost in a whisper, she insisted: ‘Come, come!’

I got up and moved toward her, slowly climbing the hill. Beyond, I noticed the Land Rover with the driver sitting inside. When I got near her, she suddenly grabbed me and embraced me tightly with great relief. It was clear that something terrifying had happened. With a trembling voice she prompted me to look towards the acacia. ‘Look there in the tree. What do you see?’ I turned to look towards where I had been a minute earlier… and was shocked to see a leopard lying on a branch of my acacia! There I had been, oblivious to the danger; happily throwing stones into the water, and all the while the predator had been sleeping in the tree above me!

Leopards often search for a safe place to rest or sleep by climbing up a tree and lying along a branch. Sometimes they even drag their dead prey up to ensure that no other animal attempts to steal it.

My mother signalled to the driver to come and get my bike and to load it. We headed to the vehicle and drove back to the house. No one spoke throughout the drive home, which brought home quite clearly the grave danger I had been in.

I often escaped with my bike to play with the watoto(*4). These were the children of local farm workers, who lived at the shamba(*5), the settlement that was built for their families. It was quite a way away from home but within the boundaries of the estate. I’d follow the dirt tracks through the vast plantations, so it didn’t take too long to get there. I had a khaki canvas bag, which I used whenever we went on family safaris into the bush. I’d use it to take along my toy cars, toy soldiers and anything else I needed. It wasn’t easy to ride with this bag slung over my shoulder, but with a little perseverance I was able to reach the shamba.

I always felt slightly disappointed with the watoto because they were never terribly impressed with my toys and always seemed to lose interest in them very quickly. This never failed to upset me since I had gone to such trouble to bring them. They preferred their own toys: soil, mud, sticks, stones and even an old bicycle wheel which they would roll by pushing it with a stick as they chased it. However, they were impressed with my bike. As soon as they saw me, two or three watoto would run over and climb on. It was great fun for everyone, especially when we lost our balance and fell down.

When we had enough of games, we would take a watango, a gourd commonly used as a canteen for water, and go to the great earthen castles built by mchwa (termites). By digging holes in the towering termite nests we would capture our prey, the larvae which resembled caterpillars, and fill our watango. The panic-stricken termites angrily bit our hands, while other teams of worker termites raced out of their fortress to chase us and bite our feet. We had to make a run for it to get away from the infuriated insects. Once back at the shamba, we would singe the termite larvae over a fire and eat them. This was an important food source for the indigenous people.

We also looked for ant nests, especially those of the red ants, which were the tastiest. Later I learned that their sharp sweet taste was due to the formic acid that ants secrete. This acid had interesting side effects: your guts would fill with gas, and so you farted like a carthorse after every meal of ants. When I returned from the shamba, I enjoyed trying to get attention by farting around the house. My grandmother was unimpressed and merely remarked: ‘You’ve been eating ants again’.

(* 4) children in Swahili.

(* 5) group of African houses, farm

My uncles had caught a small male baboon; it was a baby. They had gone hunting for trophies and found the little baboon all alone and abandoned. They tied him up and brought him home. At first they put him in a cage and gave him a banana to eat. I was delighted that they had found this little animal, and I longed to hold and hug him, but my uncle said that this was not possible because baboons bite.

We called the baboon Beri. A small wooden house was made for him, which was placed at the top of a tall post to which Beri was chained. He was able to clamber up and down the pole with ease and sit inside his little house observing the world. I would sit for hours looking at him; I wanted to gain his trust because he was terribly frightened. After a few days, by which time he had appeared to gain courage, he sat on the ground by the post and I sat facing him at a safe distance. He made some grimaces and opened his jaws wide, displaying awesomely sharp teeth. He had mustard-coloured eyes and his look was sharp and devilish it literally pierced your soul but there was also an element of deep sadness in his eyes.

One day, I remember stretching out my hand to pet him, which is a very risky thing to do. Initially he shrank back, feeling threatened, but after a while a little hairy hand grabbed my finger. We sat like this, motionless, staring at each other. I examined his little hand: how beautiful it was! It was almost like a human hand, the only difference being the brownish-grey hair covering the upper part, the jet-black fingers and the smooth palm. I studied his whole body and noticed that his penis looked like a piece of string with a knot at the end, which puzzled me. It made such an impression on me that later, in the bathroom, I studied my own body for comparison. Then I went and asked my grandmother why Beri’s ‘willy’ was the way it was. She answered with commendable seriousness, ‘You might as well ask why the elephant's “willy” is long and thick. There’s a reason for everything in nature.’ I found this answer completely satisfactory.

You see, in Africa people were not ashamed of nakedness: it was considered natural. The Masai men, for example, wore a cape over their shoulders but were completely naked in front, and the women were usually topless. As a child I never thought anything of it. And we saw animals urinating, defecating and mating almost daily. It was all a part of life.

Beri grew up and became quite aggressive because of his captivity. I could no longer get close to him without him jumping around pulling on his chain and barking like a fierce dog. His behaviour scared me and I ended up just watching him from my

bedroom window. Whenever he was calm, with the window between us, we would play a game. I would focus my gaze on his eyes and nod my head up and down two or three times, just as baboons do. He responded in the same manner. We would do this several times until it sent him absolutely crazy and he started jumping about and screaming.

One day I woke to a commotion. Something metallic was being dragged along the roof tiles and there was chaos in the garden. The servants and a gardener were shouting loudly while my grandmother gave orders in Swahili. I peered outside the window and realized that Beri had escaped. He was no longer in his little house on the pole and the chain was missing. The gardener saw me and ordered me to stay indoors.

Beri was moving to and fro on the roof of the house, dragging the chain behind him. He had no intention of coming down; he knew that if he did he would lose his freedom. After some hours one of my uncles finally arrived and succeeded in capturing poor Beri. Beri went down fighting: he managed to inflict a nasty bite on the arm of one unlucky servant before he was subdued. From the open windows I could now hear his shrieks of despair and rage as they stuffed him back into the cage. He was going to be taken to the Savannah to be released, in the hope that he would find a troop of baboons to belong to. I wept inconsolably in my grandmother’s arms. I had lost a friend forever.

Many years later I learned that when Beri was freed near a troop of baboons in the savannah, some of its members attacked and killed him. He was an enemy and did not belong to the troop, which was governed by strict rules and hierarchies.

Since my early childhood I have loved animals. I spent hours watching them from close up with scant regard for my personal safety. My uncles had grown up with hunting and it was a way of life for them. In the beginning they killed animals that destroyed or caused damage to the plantations on the estate, but later on, when trophy hunting became all the rage, helping tourist hunters to kill animals brought in a significant cash income.

The best customers were usually Americans. I can remember all the preparations that we needed to make when some wealthy trophy hunter booked a hunting safari. Then things changed in the ‘60s and ‘70s: uncontrolled hunting was officially banned to protect species that were threatened with extinction. As a result, some of the former hunters began working in large national parks as safari wildlife guides for visiting tourists.

My grandmother had four children, and my favourite uncle was the Benjamin of the family, Homer and my grandmother’s darling. He was fond of me and would always find time to play with me. I remember him as tall and blond, with a deep tan. His green eyes always sparkled and he had a broad smile and bright white teeth. I loved and respected him. I felt safe in his strong arms, and with my head resting on his chest I would breathe in the characteristic scent of his skin mixed with the clothes that he wore. I identified this scent with confidence and masculinity. My favourite uncle was a role model for me.

I was five years old and he was just twenty two when he was killed in a shooting accident while hunting. I will never forget the grief that permeated the house. My grandmother was inconsolable for a time, but eventually her love and care for me somehow helped her to overcome her pain.

After my youngest uncle died, my grandmother took over my upbringing, especially during the times that my father was away from home because of his work. My mother often went with him when he left for long periods of time, and they were sometimes absent for months on end. My brother was born, and from then on my grandmother lavished care on me almost exclusively. I was her adored grandchild! She insisted I spoke to her only in Greek. When I spoke to her in English or Swahili, she pretended not to hear. She was very strict about this. To make it easier for me to learn Greek, she ordered the language book used in primary schools in Greece at the time for me. So I learned to read and write Greek long before I went to school.

When my grandmother and her sisters lived in Smyrna they had all learnt to play a musical instrument, and my grandmother loved music. She played the mandolin. She also had an old gramophone with 78rpm records and very often we listened to Greek music, songs from Smyrna, rebetika, classical music and opera. My parents and uncles preferred to listen to jazz and rock and roll on the Grundig stereophonic record player which had been ordered from Germany. I remember examining the 78rpm records and wondering how the music and human voices got there, so that you could play it with a needle. One day I removed the round label at the centre of the record and replaced it with one of my own. I thought that if I wrote a song on the label, glued it in place of the original label and then played it on the gramophone; I would hear the song I had written. I was very disappointed to discover that it was not so and I complained to my grandmother about it. She tenderly explained that the sound is recorded on the record itself and not on the label.

If I was mischievous, a glare from my grandmother was punishment enough. At worst, she would threaten me by raising her slipper menacingly over her head, but she never actually hit me with it. I remember one time I had been very naughty and my grandmother was very cross, so she chased me to punish me. There was a large grandfather clock in the hallway of the house; I was able to open the little door where the pendulum was and hide in there, something I often liked to do. This caused the pendulum to stop its rather loud tick-tock, so, of course, my grandmother knew exactly where I was. But she kept on walking up and down the hallway, calling out ‘Where are you, my boy? I’ll find you wherever you are!’ The moment I did not hear her footsteps in the hallway, the characteristic flip-flop her slippers made as she moved along, I knew that she had stopped in front of the clock and was preparing to open the little door. The agony of those seconds made me laugh nervously, and then I heard ‘Aha! There you are’, as she opened the little door. Then it was all kisses and hugs; punishment had been forgotten!

Grandma was a sensitive and affectionate person who wouldn`t kill a fly. She loved animals and had a female corgi, called Bella, who was a loyal guard dog. Bella would lie on the verandah at my grandmother’s feet and devotedly watch her every move. When a stranger approached Bella she would growl menacingly and sometimes, when really angry, would even bite. Fortunately she was a very obedient dog, and my grandmother had only to raise her voice for this wannabe lion to become a lamb.

My grandmother was very fond of our gardener because he looked after her beautiful garden with its many tropical plants. She especially loved roses, and the gardener took great care of them. One day he hurt his leg very badly with his hoe. He immediately shouted ‘Memsahib! Memsahib!’ (Ma’am! Ma’am!), and my grandmother realized that something serious had happened. I remember her running out into the garden and saying, in Greek, ‘My dear fellow, dear me, what happened to you?’ She helped him up onto the verandah and ran to fetch the first aid kit. She carefully washed and cleaned his wound and spilled copious amounts of iodine on it. As she placed some gauze and bandaged his leg, she spoke to the gardener as if he were her own child, using a calm, gentle tone to reassure him. Then she patted him on the head and ordered the driver to take him to the shamba to rest.

Often the whole house was filled with delectable aromas from the kitchen when Grandma cooked with her assistant Sabani. I would hear the two of them chatting away in a somewhat one-sided conversation, with grandmother giving directions and Sabani mostly saying ‘Ndio Memsahib’ (Yes, ma’am). Sabani became the most trusted servant and cook. I enjoyed my grandmother’s culinary creations. Usually she cooked delicious recipes from Asia Minor and Egypt, and even European haute cuisine dishes, adapting her recipes to use local ingredients and tropical fruit. The

sweets and puddings she made were out of this world, and when she baked her cinnamon cookies and syrupy desserts, the whole house smelled delicious.

My grandmother taught Sabani all the secrets of her kitchen and so he became a superb cook. She even taught him Greek. I was very fond of Sabani, and he had a soft spot for me, too. So much so, that he often treated me to some goodies from the secret pantry that housed grandma’s delicacies. Sabani would slip me a couple of cookies or a piece of baklava while stressing that this was our secret Grandma must never know.

It was a rule that sweets were not allowed until after lunch or at afternoon tea. Often I would run into the kitchen to find Sabani, but he would be hiding somewhere. Then he would jump out at me, grab me and hold me tightly in his arms. I could smell cinnamon cookies on his apron. He would lift me up, and I would screech with joy while he laughed. Poor Sabani had no family of his own because his wife had died of an illness before they could have any children, so he devoted his life to his work.

Sometimes my grandmother was too busy to pay much attention to me and this was a golden opportunity for me to escape to seek adventure on my bike. However, I remember that once I decided to stay at home to observe the preparations for a tea party, while pretending to play with my toy cars and soldiers.

Grandma got the servants to clean the entire house and to pay particular attention to the large verandah, which had a view of the front garden and beyond to the vast estate. From one side of the verandah you could see Mt Meru and, further off, Mt Kilimanjaro, and from the other side you could watch the sun set over the savannah.

There was chaos in the kitchen from very early in the morning. Sabani and my grandmother were busy baking cakes and cookies and washing and peeling mangos, pineapples and papayas. On that day we ate lunch earlier than usual, at noon, in the large kitchen. As soon as we had finished eating, the servants started to lay the tables on the verandah with snowy-white tablecloths and napkins. Vases of flowers freshly cut from the garden were placed on each table. Servants rushed about with trolleys loaded with dishes, cups and cutlery. There was such a hubbub! And at the heart of all this hectic activity: my grandmother giving orders.

Once everything was ready, grandma retired to her room to get dressed. I followed her. She needed to smarten up before the guests arrived. Sitting at her dressing table looking in the mirror, she put lipstick on her lips. I was amused at the peculiar expressions on her face, as she stretched and rubbed her lips together to spread the lipstick evenly. She then used her finger to spread the excess on her cheeks in order to make them ‘rosier’, in her own words. Then she would press a piece of paper between her lips. I studied the paper and was struck by the shape of the lips that were imprinted on it. Grandma told me that it was a kiss. She looked different; more beautiful. She combed her hair and put a hat on, which she pinned in position on her head. ‘Grandma, you’re very beautiful, so why not dress up every day?’ I asked. ‘My dear boy, I haven’t got time to primp myself up every day, what with all the work there is to do in the house. Today is a special day; I’ve invited all these people to tea, and I must look nice for the other ladies!’

Punctually, at three p.m., the guests started to arrive from the neighbouring farms: ladies from Italy, Britain and France, as well as Greek ladies who were from Smyrna, like my grandmother. They all wore very colourful dresses and (to me) strange hats, and were heavily perfumed, all with painted faces and wide smiles and a lot of noisy chatter. Grandma was a perfect hostess and she welcomed all the ladies with handshakes and kisses on the cheek. Each lady was brought by a driver from their estate, and they came in Land Rovers or other farm vehicles. They didn’t bring their husbands, who claimed not to be able to take time off from running their estates.

Once everyone was seated, the servants came with tea, coffee, milk, sugar, impressive tiered cake trays loaded with delicious sweets and cookies and great platters of tropical fruit. Conversation was in a variety of languages: Greek, Italian, French, English, and Swahili my grandmother even spoke to her compatriots in Turkish! My grandmother and her sisters had grown up in a cosmopolitan environment in Smyrna and knew many foreign languages. My grandmother spoke fluent French, Italian and Turkish, though her English was not very good. Colonial Africa provided a cosmopolitan environment, to which my grandmother adjusted with ease.

The verandah was always shady during the day and so it was the hub of social life on the estate. It was very pleasant in the afternoon to sit in the cool, to contemplate the scenery and enjoy the view. My grandfather liked to relax on the verandah before sunset, reading or listening to opera, which he loved, on the gramophone.

In East Africa the sunset is indeed an amazing experience. Because Tanzania is on the equator, daylight lasts for a full twelve hours throughout the year. The sun rises at six a.m. and sets at six p.m. I remember I was in bed and asleep by seven; it was already dark by then. The rest of the family went to bed between nine and ten at night and got up before dawn, at five in the morning.

My grandfather was a busy man. He worked on the estate throughout the day with just a short break for lunch. He and my grandmother got up early every day and they would sit in the kitchen chatting while they had breakfast. Grandma made Greek coffee (grown on the estate) and a full breakfast of porridge with honey, fried egg and tropical fruits. As I lay half-asleep in bed, I would hear the Land Rover starting up. It was six a.m. and grandpa was off to work.

I didn’t have much to do with my grandfather he was just too busy. He was a taciturn, intelligent man who respected everyone, no matter their origins. He was a Greek born and raised in Egypt. By 1921 he had already bought land in what was then Tanganyika, which until 1918 was a German colony and then became British territory at the end of the First World War.

On some afternoons, which were really few and far between, he would lift me onto his lap and, to the accompaniment of operatic arias on the gramophone, he would tell me about Egypt and the Nile enchanting stories peppered with Arabic words to impress me. He adored opera and his favourite was Madame Butterfly by Puccini. Sometimes he was so moved by the music that I saw his eyes brim with tears. I often fell asleep on his lap, with my head on his chest, while he quietly hummed or sang the arias. He would then carry me to bed, followed by my grandmother who would disturb my slumber to make sure I brushed my teeth and washed before going to bed.

Dusk brought magic to the verandah. We watched the fading colours of the landscape and saw the sky, which in Africa is vast, changing from light blue to yellow and then red as the sun cast its last rays of light. And the clouds looked almost black, like smoke, their edges catching fire. When the sun finally sank into the horizon and disappeared, it was as if a switch was flipped, and for the few seconds of twilight there was absolute silence as darkness took over the land. With the darkness came the chorus of sounds that declared that the wilderness was coming to life.

The night is alive: hear the hum of insects, the growl of lions, the crazed laughter of hyenas as a cool breeze caresses your face. Night does not sleep; it is vibrant and alive.

Grandpa sometimes told me about the stars in the sky and showed me the constellations. At night-time the hum, buzz and hiss of insects was everywhere around us. I got the idea that the stars made this sound. My grandfather explained that the stars are silent and it was insects that made those noises. I didn’t want to believe him, but I knew he was right because my grandfather knew everything. He spoke many languages: Arabic, English, French, Italian, German, Swahili, Masai and several tribal languages of East Africa. Tribal leaders would come to meet my grandfather, to negotiate terms of employment for members of their tribes to work on the estate. They would stand in front of the house in the garden, and not come up the steps to the verandah. They just waited until someone from the house noticed them.

My grandfather knew that inviting a black person to come into your home went against all the absurd unwritten rules of colonialism. The house owner had to come meet them outside. My grandfather was unorthodox and would come down and sit with them on the grass in the garden. The conversation always began with an exchange of greetings and wishes, and then turned to the discussion around the issue concerned, diplomatically and indirectly. The discussion concluded with some form of agreement, followed by farewells and good wishes from all sides. Tribal leaders in the area respected my grandfather because they knew that he looked after his workers and their families well. He was one of the few landowners who had running water in the shamba, providing water for each home and arranging medical care for his workers and all those living on the estate. My grandfather also showed respect by making an effort to learn the dialect of each tribe so that he could communicate better with them.

When Tanzania became independent, my parents, brother and I left the country. My grandfather and grandmother continued to live on the estate until it was finally nationalized by the new government. They then moved into my eldest uncle’s house in Nairobi, Kenya. Grandpa fell into depression, and within a few years he died. Grandma wanted to bury him in Arusha, and so the funeral was held at the Anglican Church there, since the Greek Orthodox Church had closed. The service was attended by many people, including former workers from the estate dressed in their best clothes; there were also a group of Masai tribesmen in their traditional attire. Many of them had walked many miles to honour my grandfather. Throughout the service and burial they stood silent and expressionless outside the church. When my grandmother came out into the churchyard, the Masai who were amongst the Africans present raised their tall spears and shields in respect. My ailing grandmother raised her head to them and whispered ‘Asante’ (thank you). The Africans then turned and walked the miles back to their homes and shamba in silence.

My grandmother and I would spend fifteen to twenty days a year on the shores of the Indian Ocean. My uncle would rent a beach hut with very basic amenities on an endless sandy beach washed by the ocean’s waves. I loved to fall asleep listening to the rhythm of the waves.

Naturally, I had my bike with me, though of course it was impossible to ride it in the sand. Luckily, behind the hut there was a well-trodden dirt road running parallel to the shore that led through a grove of palm trees to the nearest shamba. I often went to the shamba. Whenever I arrived on my bike the watoto and women clapped rhythmically to welcome me. As I cycled through, the watoto would run after me laughing. Sometimes I would watch local fishermen as they came ashore with their

boats. They pulled their nets up and spilled their catch on the beach and I was dazzled by the variety and colours of the fish and other sea creatures they had caught.

The beach was stunningly beautiful and very different from the environment of the farm. The contrasts in colours were striking: the deep blue sea, white waves crashing on the distant reef, the dazzling light and the white sand, backed by dense groves of palm and all this under the magnificent blue African sky with clouds scattered in a characteristic pattern just above the horizon.

My grandmother cooked simple meals during our stay at the beach hut. She did all the cleaning, washing and tidying herself, as we had no servant with us. We ate mostly fish and fruit. My grandmother would often buy fruit, vegetables and fish from passing peddlers. Sometimes she bought crab from the fishermen, which she boiled in seawater on an outdoor wood stove that was in the yard of the beach hut. Very often we had visitors, mostly Grandma’s friends from nearby Mombasa. At the end of our stay, my uncles would visit for a few days to swim and relax before taking us back home.

Back at the estate, I missed the sea a lot, even though we were near Lake Duluti where we could take a dip. There were water-skiing facilities there and it was very popular with Europeans. The water at the lake was safe and crystal clear, but I much preferred the sea. I was entranced by the coastal environment, the bleached sands, the salinity, the palm trees with their fronds rustling as they swayed gently in the breeze this was magical to me.

When my uncles realized that there was a lot of money to be made by arranging safaris for trophy hunters, they started to do it more and more. In order to hunt you needed a special licence from the authorities. There was a tiered price system for each animal depending on the species a prospective hunter wanted to kill.

Once I went on such a safari. Hasani, a servant whom my grandmother trusted, was sent to look after me. Our expedition set off, including a convoy of four Land Rovers and a truck, a cook, two servants, four guards-cum-hunters, my two uncles and their girlfriends, two American customers and Hasani and myself. It took us almost a day travelling on the dirt roads to get to the area of savannah we proposed to hunt in. This African landscape is all too familiar from countless films and photographs in tourist guidebooks, but it is one thing to see it in pictures and another to actually experience it in real life. Not only do you see the landscape, but you also hear the sounds, smell the scents and actually feel the pulse of the wilderness. It is an immense vastness, a never-ending horizon: a limitless savannah with its huge herds of wildebeest and its acacias acacias whose ferocious thorns do nothing to deter giraffes and elephants, which reach their tender leaves with apparent ease, oh so deftly plucking and eating them.

The dormant volcano Mt Kilimanjaro with its snow-capped peaks was the backdrop to an area of lakes and waterholes that lured myriads of birds, flamingos and mammals that would approach to bathe and drink and share the water with respect.

On our way there we met a rhino. He felt threatened by our convoy and tried to bash one of the vehicles with his horn. The drivers were experienced enough to manoeuvre the vehicle so as to stay out of trouble. A bit further down the track a herd of elephants stubbornly held their position in the middle of the road, their matriarch flapping her enormous ears as a warning that we were a threat to them. The only thing you can do in such a situation is be patient and wait until they leave peacefully. We never ever drove up to an elephant hoping it would give way: elephants always stand their ground and can become very aggressive, and they are large and powerful animals that can easily overturn a vehicle or trample a person to death. Beyond the elephants, three ostriches crossed the road, completely ignoring our presence.

We finally arrived at our destination and immediately began unloading and setting up the tents at a suitable site; the servants lit a fire, paraffin lamps were hung on branches of trees, inside the tents and on the tables. Water tanks were positioned

near the kitchen and the shower tent. Immediately the cook began preparing our meal, while the servants laid the table for dinner. Meanwhile, my uncles were planning the next day’s hunt with the American customers. It would start at the break of dawn the next morning, even earlier if they could. Two scout hunters had already set off to search for signs and traces of animals that were destined to be their prey the next day. That was how you knew what animals were around and in which direction they were heading. Once the scouts returned, it was time to eat. The servants would eat on the ground in the kitchen area after they finished serving us. Our temporary dining room was a long table with folding chairs set up in a huge tent with open sides.

My grandmother had prepared burgers for us to take with us, and they were cooked on the fire. Also on the menu were baked potatoes, salads, fruit and a dessert. At seven in the evening Hasani and I went to our tent, which had a partition; I slept on a camp bed in one section of the tent and Hasani slept on the ground in the other. Outside the tent there was a guard sitting on the ground. The four guards took shifts during the night to keep us safe from wild animals, thieves and poachers. I slept peacefully, but now and then I heard a cry or a roar, the chorus of insects and Hasani’s deep breathing as he slept. Outside the tent two guards spoke to each other in undertones.

At dawn, when I woke up, Hasani was already up and about, and he took me to wash at the canvas sink outside the tent. I noticed that my uncles were missing, along with the Americans and two guards. I was afraid that the hunt had already started.

I sat at the table at the big tent, where my uncles’ girlfriends were already seated, chatting and drinking coffee. We smiled at each other coldly but did not exchange a word. I grabbed some freshly cut mango and ate it noisily, juices dripping from my mouth. Then Hasani helped me spread butter and jam on a slice of bread, which I bolted down too my grandmother, was not around to notice my table manners.

Hasani watched me like a hawk, so I couldn’t move around the camp freely until my uncles returned from the hunt. After some time I heard the distant sound of the Land Rovers returning, as I imagined, loaded with trophies. What a relief when the convoy arrived at the camp and I learned that they had had no success in killing an animal! They had found a herd of Thomson’s gazelles, but these, sensing danger, had run away. The Americans wanted a female Thomson’s to add to the huge collection of trophies they had back at home in the USA; they were proud of them and had boasted about them at dinner the previous night

Now, to cheer themselves up after this disappointing hunt, they all drank coffee and started to plan another outing for the late afternoon. This conversation was cut short when a hunter approached one of my uncles and whispered something to him.

In a split second, the four hunters and both my uncles had grabbed their rifles and were moving stealthily towards some bushes not far from the camp. My uncle gestured for quiet. This was the signal. I knew that any moment an unprotected animal would appear in harm’s way. I wanted to shout ‘Uncle, please don't…’ but was silenced by the blast of a rifle towards a clearing in the bush. I stood frozen; I did not want to see the animal wounded or dead. It was a female Thomson’s!’

Experienced hunters stay still for some minutes after a shooting before slowly approaching the animal, just to make sure that it is quite dead. After the necessary wait, my uncles with two of the hunters, followed by the very excited Americans, moved forward towards the clearing. The other two hunters kept their rifles raised and aimed, ready to shoot if necessary. I saw my uncle standing where the animal was to examine it. I couldn’t see it because of the tall grass. He signalled to the two hunters to carry the corpse off to be skinned. In despair I ran and hid in my tent. Even at the relatively young and tender age of seven, I was both angry about this murderous activity and disturbed by it.

I lay on the camp bed while Hasani held my hand; he knew that I was deeply upset. To distract me from my sorrow, he lifted me up and carried me as far away as possible from the now lifeless Thomson’s. The hunters skinned the animal immediately, away from the camp. A corpse and the smell of death would attract all sorts of animals, especially hyenas and African wild dogs, which would catch the scent of blood and be drawn to the scene.

While the beast was being skinned, the Americans, my uncles and their girlfriends chatted over sandwiches and cookies and drank tea from a seemingly bottomless teapot. Everyone, it seemed, was satisfied with the outcome, except me.

A faint bleating sound caught my attention. It sounded like a lamb, but it wasn’t. I pulled urgently at Hasani’s hand, and headed towards the clearing where the murder had taken place. We weren’t the only ones to hear the sound: everyone had stopped their conversation and tea drinking to listen and were startled when a tiny baby gazelle appeared. It was the fawn of the shot Thomson’s gazelle desperately looking for its mother. I burst into tears and begged my uncles to catch it and save it from predators, which would surely be attracted by the smell of blood. My uncle ordered his guards to chase it; I followed, pulling Hasani with me. My uncles yelled at Hasani to keep me back, but I escaped and disappeared into the tall grass. I could hear the hunters ahead of me and I started to run after them. Then I found myself in the clearing; I saw the blood-stained earth where the female Thomson’s had been shot.

The hunters were lost to view, but behind me I could hear poor Hasani calling me, panting, to go back. I turned into the bushes and hid; my heart was pounding. I crouched down low and hugged my knees. Around me I could hear voices, but I froze when I heard some rustling in the bushes. I turned my head and saw the most wonderful creature staring me in the eyes. I held my breath. It was the baby Thomson’s, its eyes glistening and nostrils dilated in terror. We stared at each other for some moments, but when I plucked up the courage to move closer, quick as a shot, he sprang out of the bushes and vanished. I got up and walked out into the clearing in search of the fawn. Far away in the savannah I saw the two hunters chasing the little Thomson’s before it disappeared in the distance.

How I wished I had my bike with me! I was confident that with my faithful bike I could have caught up with the baby gazelle, and it would have been easy to persuade it to follow me back to the camp and safety. I would have taken it home and taken care of it. I began to weep. Hasani hugged me and then carried me back to the tent at the camp. My uncle gave me a good telling off. I was never to do that again! It was dangerous to leave the camp.

Once in the tent I lay on the camp bed and said to Hasani, my eyes brimming with tears and my voice trembling with emotion, ‘I have lost a new friend!’

In the evening we all sat at the table in the big tent. The Americans were very happy, and my uncles proud. Bottles of beer were opened and wine flowed abundantly to celebrate. The grateful Americans raised their glasses and toasted my uncles. My uncle told his guests that we would be barbequing and eating the slain Thomson’s gazelle. My blood ran cold in horror, and I shouted that I wouldn’t eat the meat. Everyone at the table burst out laughing: they thought I was being cute. But I insisted that I would not eat it. My uncle then threatened that I would not get any trifle, which he knew was my favourite dessert, if I didn’t eat the main course. ‘Then I won’t eat anything’, I replied stubbornly. My uncle said ‘If you don’t eat the main course you will never become a man!’ I replied quietly, with my head bowed, ‘Then I don’t want to be a man.’ This made everyone laugh even more, but Hasani, who was standing behind me, let his hand rest on my shoulder in sympathy. I did not eat any dinner that evening, on principle.

Later, Hasani secretly brought me a plate of trifle and a spoon to the tent, offering them to me with a kind smile. I can still taste that trifle today. Its sweetness consoled me for the bitter feelings that filled my heart, and comforted me for the loss of the little friend who ran away in terror. Best of all, it made it possible to ignore the loud voices and laughter emanating from the big tent

I was five years old when my brother was born. He was a tiny baby and had health problems at first, though he soon got over them. My mother was very busy taking care of the new baby, so I continued to be looked after by my grandmother.

When my brother was six months old, my father took on a construction project in Kisumu in Kenya, near the border with Uganda. All four of us moved there temporarily. It was the first time I had left the farm and I missed my grandmother. This was a period of adjustment, getting used to being under the care of both my parents. My mother had to look after my little brother, who proved to be a very

quiet baby. When I approached him he would smile at me; I wanted to touch him and lift him in my arms, but she would not let me because she was afraid he might get an infection.

The house where we lived belonged to the company my father worked for. It came as a ‘package’, with gardener, servant and nanny, if needed. My mother did not want a nanny at this early stage, as she was so afraid of disease. Although she was neurotic about illness, I must admit she was scrupulous in her standard of cleanliness. She was very strict with the servant, who had to clean the house on a daily basis. The house had two storeys, with a huge garden that bordered on the largest lake in Africa, Lake Victoria. To reach the lake’s shore you had to descend some twenty stone steps.

For my birthday, my father brought me a new bike. I was overjoyed, jumping around and hugging his leg he was not too pleased as he did not like demonstrative behaviour. Although he was rarely affectionate with me, over time I realized that he loved me in his own way.

I jumped on my bike at once and began riding up and down the flat lawn in front of the house. Compared to my rides on the estate this seemed rather boring. I really wanted to go further away. As I rode through the vast garden, which was a jungle of plants, shrubs and tall trees, I realized that the brakes were not working properly; they needed adjusting. This did not stop me from riding crazily around at top speed with my new, heavy steel bike. I was a daredevil and thought I could stop by dragging my feet on the ground. I found a downhill path leading to the shores of the lake. The gardener was busy in the garden, but he wisely kept a watchful eye over me while I rode around like a madman.

I started to speed downhill; I lost control of the bike and wasn’t able to stop before reaching the first step, so I went down the first few with a thud, thud, thud. I could hear the gardener yelling and calling for my mother. I then lost my balance and so down I tumbled to the bottom, holding tightly on to my new bike, not letting go of it because I was afraid it would be lost forever if it fell in the lake. I finally stopped just a few feet from the water with the bike upside down on my chest. I felt no pain, but I began to cry when I saw my mother running down the stairs, tripping and falling down next to me. I was so scared I began to shout ‘Mama, mama!’ I couldn’t get up because the heavy bike was pinning me to the ground. Eventually, when I managed to push it to the side I saw that my mother was rubbing her ankle to soothe the pain. She forbade me to get up and so I stayed lying down.

The gardener rushed to help her get up. He then carefully untangled the bike from my legs. My mother, despite the pain in her ankle, examined me and tenderly asked me if I had hurt my head or felt pain anywhere. I did not feel any pain; at this point I was shaken and really worried about her. As I was lying on my back, I looked up at

the tall trees that seemed to touch the sky. Then all of a sudden a gust of wind blew over us, shaking the trees; passing clouds swelled black and I could hear the waves lapping the shore in increasing intensity. A thunderstorm was brewing as it always did at this time! We had to move quickly. The servant also came to our aid and carried me to the house, while the gardener helped my mother to climb slowly up the stairs. I don’t remember anything after this. Apparently I fainted.

When I came to I was in bed and my father was there, with another man standing next to him, a doctor, who examined me and asked if anything hurt. It is true that some parts of me hurt a great deal. The doctor moved my hands, arms and legs and reached the conclusion that there was no serious injury or fracture, and therefore no reason for concern. He told me to drink water and sleep. I asked about Mama. My father told me that she was in her room with my brother, her ankle bandaged up. Xrays at the local hospital showed she had only suffered a severe sprain. After a few weeks, Mama, my brother and I returned to the estate, while my father remained at Kisumu for the remainder of the contract.

My father had been appointed to a road-building project, so our little family set off for Swaziland, a tiny African country. Swaziland was desperately poor then and remains poverty stricken today, even after forty-five years of independence. The situation in Swaziland provides just one example of how the harsh realities in subSaharan Africa conspire against the poor people who live there: they are oppressed by corrupt leaders who are supported by Western governments, greedy to exploit the abundant natural resources to be found there.

We set off for Swaziland with two Land Rovers and a truck loaded with supplies and equipment, just as if we were going on an ordinary safari, and with us were two armed askari, two drivers, three workers and two servants. The journey would take eight days. On the way we would stay in suitable hotels if we happened to be in a town or city, otherwise we would camp.

We were within a day of Swaziland when we were hit by torrential rain, which in Africa is a scary phenomenon. Suddenly the heavens open and it’s like trying to stand under a waterfall. A curtain of water deluges from the sky and your surroundings become invisible. The ground all around becomes completely flooded in no time at all. In the midst of this downpour, with night falling, we arrived at a raging river. Rivers in the bush are usually not spanned by bridges; in the dry season vehicles can cross comfortably. Now, however, the river was swollen with floodwater and was in spate.

My father jumped out of the Land Rover to assess the situation. He wanted to see how deep the water was and asked the workers to wade into the river with poles to measure the level. My mother, who had my brother on her lap, sat with me in the front of the Land Rover. She shouted to my father to hurry because daylight was fading. She suggested that we set up camp for the night, but my father finally decided that it would be possible to drive the convoy across. My mother shook her head worriedly; she didn’t agree.

Once back in the driver’s seat, my father adjusted the gears. I watched his capable movements with admiration. He began to tell everyone what to do and, in Swahili, ordered the workers who were sitting in the back of the Land Rover to stand up and spread their weight in order get the vehicle across the river. In the distance we could hear thunder while lightning flashed ominously on the horizon. The Land Rover began to move and my father drove carefully towards the river, twisting the steering wheel quickly from side to side and accelerating the engine. The Land Rover tilted

downwards as it entered the water, and water began to seep in as we began our slow progress towards the opposite bank.

I then remembered my bike was strapped to the roof rack, and I was concerned because it was getting wet and that it might slip into the river and drift away! There was dead silence while my father concentrated; no one uttered a word. Then at some point the Land Rover started to sink and the water began rushing in. My mother screamed and held the baby tightly in her arms. Then my father leaned out of the window and shouted to the workers in the back to get out and push: ‘Sukuma! Sukuma!’, meaning ‘Push! Push!’

The workers shouted back ‘Bwana (Sir), we are pushing!’ He was furious when he looked into his rear view mirror only to see them standing and pushing from their position inside the Land Rover. ‘How can you be pushing, since you're in the Land Rover? Get out and push immediately!’ And he added, ‘Ng’ombe!’, which is a term, literally meaning ‘cow’, used in Swahili to express anger at stupidity. They immediately jumped into waist-deep water, yelling to each other, and tried unsuccessfully to push. To add to the chaos, at this point my mother decided it was time to abandon ship: ‘Tell the workers to come and get the kids, I’m getting out!’ But she could not open the door because of the pressure from the rising water on it. Almost panicking, she opened the window and passed my brother to the outstretched arms of the workers. Poor thing, he started to cry, obviously aware of the danger. My mother shouted ‘Lift him higher! Go to the rock there high on the bank!’ It was my turn next: ‘Now you.’ I climbed over my mother to the window and into the strong arms of the workers. She gave me instructions: ‘When you get to the rock, hold your brother in your arms. Hold him tight!’

The workers, carrying us, made their way through the swirling waters around them. When we reached the rock by the shore I sat there with my brother in my arms. I was so happy to finally be allowed to hold him. By now it was dark, but in the headlights of the Land Rover I could see him smiling up at me, and I smiled at him and whispered ‘My sweet little brother, you are safe in my arms.’ When I spoke to my brother it was in English, the language we would always use with each other as we grew up. Very rarely did we exchange a word in Greek. With our mother we would speak in Greek, English and Swahili; with my father in English and Swahili. Although he understood Greek he never spoke it. It was very amusing to hear conversations between my grandmother and my father. It was an explosive mix, him speaking English and Swahili, and my grandmother Greek, French and Swahili, all jumbled up!

It was raining heavily now. The workers helped my mother to climb out of the window. She barely made it to our rock and safely through those dangerously rising waters. I was overjoyed to make out the silhouette of my bike, still on the roof of the Land Rover, tied amongst the trunks. I really did not want to lose my friend.

She sat near us and stretched out her arms to take the baby from me. I heard loud voices as everyone prepared for a last effort get the vehicle across. The engine roared and then choked to a silence: it had flooded. All of a sudden another convoy turned up on the far side of the river. There were several vehicles and their headlights threw light onto the whole scene. They shouted and my father answered. Rescuers had arrived. They immediately pulled chains from their vehicles and attached them to the Land Rover that was stranded in the river. My mother left us to go and help, so I had the chance to hold my little brother once again. She asked a guard to sit with us. We could hear the voices of wild animals all around us in the night, but we were assured that there was no danger because the commotion would keep them away.

The rain stopped and my brother started to cry; I rocked him in my arms just as I had seen my mother do when he needed calming. Before long I heard cheers as the Land Rover was finally pulled across the river and reached the shore. Already the volume of water was starting to decrease. My mother asked the guard to take us to the second Land Rover. We boarded quickly as it was already attached to one of the vehicles on the opposite shore; behind us was the truck. There was a jolt and we began to be hauled across the river while the wheels knocked noisily against rocks on the riverbed. The experienced driver held the steering wheel firmly, shouting in Swahili to the others on the opposite bank. Finally the truck was dragged across the river and we were safely on the other side. We were all drenched and exhausted. It was decided we would camp for the night and begin the final leg of the safari to Swaziland at dawn. The four of us slept together in one tent after we had had something to eat. I fell asleep to the sound of rushing water and the cries of wild animals.

My life on my grandfather’s estate was interrupted a number of times, when my mother, my brother and I accompanied my father on some of his various distant civil engineering projects. Each time we left I was in tears because I was leaving my beloved grandmother. She always waved a white handkerchief until we were out of sight.

In Swaziland we lived in a compound provided by the construction companies for European employees. The houses, which were like round cottages, were known as rondavels, a word of South African origin, in the language of the Boers, Afrikaans. The rondavels were a westernized version of the traditional African round hut with a thatched roof. Often, to increase the living space available, two, three or more rondavels were connected by branch- and reed-covered walkways. The building we lived in had three bedrooms and a bathroom in one rondavel, which was connected through a corridor to a second rondavel. This second section had the lounge and dining room, while the third rondavel housed the kitchen and laundry and had storage space. There was also a garden, which was shared with the other four houses in the compound.

Once we had unpacked and got settled, the staff returned to the estate in Tanzania with one of the Land Rovers and the truck. I was impatient to start my explorations with my new bike. By early evening, I had got to the home of the owner of this estate, a very large sisal plantation. I spotted a fenced-off area with several hens. At home we had a chicken coop but I was never really interested in it perhaps because I took it for granted.

I returned to our new home to eat and, totally exhausted, went to bed for the night. The next morning I woke up to find my mother with a young servant in the kitchen, preparing breakfast. My father was already up and sorting through his paperwork. I loved to look at the plans and designs of his projects. Sometimes, when he was in the mood, he would give me crayons and paper and involve me in what he was doing.

While my mother fed my brother, I sat down to a hearty breakfast of pancakes, fried eggs and fruit. When my father left, I grabbed my bike and set off to have another look at those hens. I was curious to see how chickens laid their eggs.

I saw someone collecting eggs from an oblong nesting box with many trap doors which seemed to be attached to the coop. As soon as he left I approached and opened a trap door to peek in. Disappointingly, I saw straw and nothing else. No chicken, no egg! Frustrated, I decided to continue on my bike ride to explore the estate. I arrived at the sisal plantation with great difficulty. The dirt road had a surface of powder-like dusty soil, which made cycling impossible. The wheels sank deep into the dust, but I persisted and eventually got to the sisal plantation. The workers were already at work; they had been busy since the early hours among the endless rows of sisal, cutting off the spiny leaves from the plant with a panga (an enormous knife-like tool, more like a short sword with a wide blade). This is a tedious task and you have to be careful when chopping off the long leaves, because there are spines that cause nasty, painful scratches, which can get infected.

The workers gathered the leaves into piles by the dirt road to be loaded on to trucks. These would then be transported to a factory for processing. The strong fibres from the leaves were used to make rope. I got off the bike to hang about watching the workers’ skill in using the panga. I watched one person in particular. He was about thirty and, like everyone else, he was singing as he worked. They all worked in time to their music. This is what the workers on my grandfather’s estate did too. Rhythm and song is in the blood of the indigenous people. I did not like the term ‘black’ to denote the native people. In the colonies it was the usual way to distinguish the ‘native’ or ‘indigenous’ from the ‘white’ mzungu, the Europeans. I felt that we were all Tanzanians regardless of our origins or skin colour.

Pushing my bike, I got closer to the workers. They wore only khaki shorts and were barefoot. Their bodies were slim but muscular, their skin dark brown and smooth. I always admired the perfect lean bodies of the Africans. At my grandfather’s estate, the topless young women had slender figures and perfect breasts. They spent hours labouring in the heat, bending over to plant and dig tirelessly. In Swaziland I saw topless women carrying heavy things piled up on their heads. They walked with such ease and perfect balance. All this heavy work gave them perfect slim bodies that would be the envy of any modern young woman in the West.

One worker stopped to look at me and he smiled, showing his gleaming white teeth. He could speak English. ‘Hello, where are you from?’ I answered in Swahili as I was used to speaking to workers in this language. The young man looked puzzled and I realized he did not understand me I hadn’t realized they don’t speak Swahili in Swaziland so we continued our conversation in English. However, the supervisor, a European, yelled ‘Get back to work!’ and the young man winked and smiled, then continued with his chopping and singing. It was time to leave.

Trucks were passing by raising a suffocating dust from the dirt road. I made my way back with my wheels sinking into the soft soil every now and then. I reached the estate owner’s house, which was large, consisting of seven to eight rondavels, with an impressive verandah that followed the curves of the round buildings. I saw tables with chairs and sun loungers. There were potted tropical flowering plants everywhere. It was very beautiful. Suddenly I heard a growl coming from the verandah. My heart stuttered as I tried to work out where the sound had come from. I saw a huge black dog moving along the verandah; I was scared. I was more frightened of large domestic dogs than wild animals. At once I started to speed away on my bike. My hands were shaking as I gripped the handlebars and I pedalled desperately. I was sure that I would be pursued, but when I turned to check I heard a male voice calling sternly to the dog; I did not understand the language spoken, it may have been Afrikaans.

I was still panting when I reached the chicken coop, where, very hopeful and with great care, I opened the nest box doors. I could hear scratching in one nest box, so, very slowly, I lifted the lid and was delighted to see a brown hen scratching the straw into a comfortable nest so she could sit and lay her eggs. I held my breath and watched. She had her tail towards me and she made the ‘qua-quaaaa’ sound hens make when they are about to lay. At last the magical moment had arrived. I saw the brown egg ease out and in a few moments it dropped gently onto the straw. I was overjoyed! I hoped to eat this egg in the morning at breakfast.

Once, people lived in harmony with their environment. There were no excesses, over-consumption, industrialization or greed, and the small communities of ‘primitive’ inhabitants were self-sufficient. Then the white people came and everything changed: the wealthy nations of Europe sent colonists to Africa who carved up the continent for their own use. Explorers of sub-Saharan Africa, such as Livingstone and Schweitzer, innocently opened the door for exploitation, and so in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the scene was set for one of the most extensive looting of resources that has happened in modern times. The colonial powers became wealthy by plundering the natural resources and underpaying the local workers. In those early days, most mzungu (Europeans) lived lavishly in their privately owned estates, with plantations, large houses, servants, labourers and guards at their service.

Today, several countries in the continent have corrupt regimes supported by the West. There is poverty, misery, disease and often famine on a large scale. This situation was inherited from colonial Africa, and I feel upset that I could do nothing to protect my beloved homeland from the ills that beset it. Now harmony with one’s environment is a distant memory and Africa, once teeming with wildlife, watches as its many species gradually disappear.

Once I had high fever and I had to stay in bed. I think it was measles. We were supposed to be leaving for Rhodesia, where my father would be working on the huge Kariba dam project, but we had to put off the journey for a few weeks. I was sleepless and lying in bed, so I created imaginary designs on the whitewashed ceiling. I noticed that the lampshade hanging from the middle of the ceiling seemed to be moving oddly. Motionless and weak from the fever, I could not focus properly and my eyes felt heavy, but it seemed to me that a thick cable had come loose and was hanging from the lampshade. It was moving strangely from side to side. I shouted as loud as I could ‘Mama, Mummy!’ Within seconds Mama was beside my bed looking at me with compassion and affection. Before she could speak, I raised my hand and pointed towards the ceiling. My mother looked up and responded like lightning. In a fraction of a second she had lifted me together with my bedclothes and literally dragged me towards the door, shouting for the servant ‘Boy! Boy! Come quickly!’ (It was customary to call servants or waiters ‘boy’ at that time).

Mama lay me down in the guestroom and I immediately fell asleep. Days later, when I had recovered, I learned that it was in fact a snake hanging from the lampshade. The brave servant made sure it was quite dead; he wanted us to be safe. Most African snakes are poisonous, although I never found out if the one hanging from my light was too. There was an unwritten rule in Africa that any snake or insect that came into the house had to be killed, to keep us safe.

We got ourselves ready for our Safari to Rhodesia, and a large truck came to get our stuff. The trip was uneventful this time. We left Swaziland before dawn and travelled through South Africa on good paved roads, arriving late the following day. My little brother kept crying on the journey, I think it was just too monotonous for him.

In Kariba we lived in a small, prefabricated house. There was a huge construction site for the Kariba dam project, and a small township grew up around it. A consortium of construction companies was building the dam; the largest company was Italian and had also built the township. There was a school, a hospital and shops for all the European staff.

We had no servant. Most of our neighbours were Italian, and I soon found new friends to play with amongst their many children. I also went to my first school in Kariba. A school bus took us to school in the morning and returned us home in the afternoon. Most lessons were in Italian and only some in English, and so I quickly learned to speak basic Italian. I was the only kid to have a bike. What was more, the roads were hilly in the township and it was tough cycling, so I gave up my solitary cycling in favour of playing ball and other games in the company of my new friends.

In Kariba I ‘grew up’ and became more mature. I learned how to be sociable and to be aware of others. Being at school brought me into contact with children of my own

age. Of course, I missed the farm and my grandmother, her cooking, her games and reading and writing lessons. I was almost nine years old and it dawned on me that I had started school a lot later than everyone else. I had had very basic tuition with my grandmother and on occasion with my father and uncles. I had learned arithmetic, and how to read and write Greek and English. In the sitting room of our farmhouse at the estate there was a library with numerous books and encyclopaedias. I was fascinated by the illustrations and maps, travelling in my imagination around the world. On the farm the only contact with other children was with the watoto at the shamba.

In Kariba I learned to play and socialize with other European children; it wasn’t easy for me because I had to learn to be more sociable, to make compromises and to share. It was brought home to me that I wasn’t the most important person in the world, and that others had needs and opinions as well. In spite of this, because I was more independent, more determined and more daring than anyone else, I always ended up as the leader in our games. I fell in love with a pretty Italian girl and never missed an opportunity to hold her hand. I even dared to kiss her on one occasion and shall never forget how I felt when she responded positively.

My brother was only two years old and I was still not allowed to play with him because he was so young. All my mother let me do was hold his hands or tickle his tummy, which made him smile. I liked people who smiled. All of my African friends (the watoto) always smiled.

When my father’s contract expired with the consortium in Kariba, he got a job on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It was decided that we would go there.

Mama, my brother and I first returned to the estate to stay for a while before saying our goodbyes, because the political situation was becoming very uncertain due to claims for independence.

We would not be returning to Tanzania after Mauritius. We took a flight from Lusaka in North Rhodesia (modern-day Zambia) to Nairobi. Our stuff went by truck back to Tanzania. The flight was with a very noisy Dakota aircraft. One of my uncles came to pick us up from the airport in Nairobi, and we stayed one night at the famous Norfolk Hotel downtown.

I was eager to see my grandmother; it had been almost two years since we had left for Swaziland. The following day we would be back home at the farm.

The Kariba Dam is a hydroelectric dam in the Kariba Gorge of the Zambezi river basin between Zambia and Zimbabwe (formerly North and South Rhodesia). It is one of the largest dams in the world, standing 128 m high and 579 m wide. Construction on the dam began in 1955 and it took 25 years to complete at a tremendous cost. During its construction, no less than 86 workers lost their lives. Thousands of large animals were threatened by the rising water and had to be rescued in what was known as Operation Noah, a wildlife rescue operation that lasted 5 years. Over 6000 animals (elephant, antelope, rhino, lion, leopard, zebra, warthog, small birds and even snakes) were rescued and relocated to dry land.

The creation of the reservoir forced the resettlement of about 57,000 Tonga people who had been living along the Zambezi in both Zambia and Zimbabwe. The government of the time made some attempt to implement sustainable farming projects for the production of cash crops. Unfortunately, they neglected to make any scheme for the irrigation of the crops. Schools, dispensaries and hospitals were to be built close by. Nothing like that happened. It is doubtful that much resettlement aid was given to the displaced tribespeople. Today most of them still live as refugees in camps. They live in unproductive problem areas, some of which have become so seriously degraded that they remind one of the areas on the edge of the Sahara Desert. Kariba remains the worst dam resettlement disaster in African history.

As a child, the farm was the centre of my world; I thought that Tanzania was the most beautiful country in Africa and I would never ever leave. However, even then the future had been uncertain for the colonists because it had been getting more and more difficult for Britain to maintain her sovereignty. The African people were beginning to become politicized and to demand independence from the Europeans.

The British Empire had started to shrink after the Second World War with the independence of India and its partitioning with Pakistan in 1947. British policy in the colonies was seen by the European settlers in East Africa as a betrayal, and they felt insecure and threatened. This was very hard on my poor grandfather, who had sacrificed forty years of his life working hard on his estate for all of us and didn’t want to believe that it had all been for nothing. My family was afraid that we would lose everything, as had happened to Europeans in other colonies that became independent. There was a heavy atmosphere and I overheard countless discussions about what we should do if independence were to be granted to Tanzania.

Gradually, as time went by, I could sense that my life on the farm was coming to an end and I had to face a new reality. What worried me most were the fates of my grandmother and grandfather: Where would they go?