8 minute read

Chapter Twenty Mauritius

Mauritius is a tropical island in the Indian Ocean and people from various races live there, including Creoles, Indians, Chinese, French, British and other Europeans. We lived there for almost two years in a big house with a garden, which was part of a huge estate with endless plantations of sugarcane. My brother was at last old enough for us to play together. We did do some exploring together on foot, but mostly I preferred to go off alone on my bike.

I went to a small private French school and my teacher was a pleasant but strict Frenchwoman called Madame Lettelier. I added French to the Italian that I had learned in Kariba. I read a great deal and drew maps. I was in constant search of knowledge and I wasn’t just interested in school subjects. Dad had an extensive library and I spent my free time either perusing these books, or disappearing off to explore my surroundings.

Advertisement

I often played with my brother, who was now five years old. In general we got on well together, but because he was littler than me I was very protective of him, which really annoyed him. I went to school in the morning (my brother had not started yet) and he would be waiting for me when I got home in the afternoon, ready to play. He did not have a bike because our parents believed he was not strong enough for cycling. They did buy him a toy car to drive so that he wouldn’t complain, but that was useless for the kind of trips I wanted to do on my bike.

At home we had two maids; one was an elderly Indian lady, who was stone deaf and horrid. I detested her. She would always shout at us to ‘go and play in the yard!’ because she wanted us out of the way. The other servant was a plump young Creole lady called Lillie; she spoke French and was always good humoured.

I really wanted to get revenge for the unacceptable behaviour of ‘Cloth Ears’, as I called our Indian maid, and one day my chance came. There was a tap in the garden. I filled a bucket with water and mixed in soil from the flowerbeds, creating a large quantity of mud. ‘Cloth Ears’ had just hung the sheets on the line to dry in the sun. The coast was clear so, as quick as I could, I threw all the mud from the bucket onto the sheets. It looked satisfyingly wonderful. I then cleaned up the crime scene by washing my hands and getting rid of the mud from the bucket, and then, relishing the sweetness of revenge but also scared I’d get caught, I made a quick getaway on my bike.

After lying low for a while I had to go back for lunch. As I approached the house I heard a dreadful scream; there was ‘Cloth Ears’ standing in front of the filthy sheets, holding her head in horror. Mama and Lillie came rushing out of the house to see what had happened. I seized this chance to make a run for the house and get straight to my room unobserved.

At midday Dad came home for lunch and we all sat down together to eat. Mama reported the incident and immediately my father turned to look at me and obviously found the air of innocence I affected, as I looked him straight in the eye, deeply suspicious. ‘I want to talk to you after lunch,’ he said in a stern tone of voice. I eventually confessed my guilt and my punishment was to be grounded. I had to stay in my room throughout the next day, which happened to be Sunday. My little brother objected to this punishment because he lost me as a playmate for a whole day.

A few days later, ‘Cloth Ears’ gave in her notice, citing fatigue as the reason. I rejoiced; so did my parents, secretly.

One day I plucked up courage and ventured outside the estate with my bike. I went out to the main road that ran past the entrance to the estate. I cycled along with the rest of the traffic. There were oxcarts, trucks, cars and many bikes ridden by Indians and Creoles. The traffic was slow-moving because the road was so narrow that it was impossible to overtake. There was an endless convoy going one way, which traffic from the other direction had to swerve to avoid.

On frequent outings onto the road I gained the confidence to ride my bike in heavy traffic along with other cyclists. I would never go far; I would just cycle up and down the main road observing how everyone behaved on the road.

I was no longer afraid. With my two-wheeled friend I now experienced true bike freedom, not only in the wilderness, but also in adverse traffic conditions!

Every time I grew out of a bike I was given a new one. By the time we went to Mauritius I was on my fourth bike. All but the new, largest bike were left behind in the storehouse at the farm. My grandmother said she would give them to the watoto, which seemed to me a good plan, as they would make my friends happy, and the bikes themselves would feel useful. Though for some reason, she kept my first bike on the verandah of the house at the farm. I have never forgotten my first little bike that gave me such liberty and joy. It had taken me into nature and shown me how to be free, brave and independent and opened my mind to all kinds of experience. The latest bike carried on the work of the first bike, as well as helping me to understand how to live with other people in a multicultural society, and was my companion as I became more mature.

I lost this two-wheeled friend to a cyclone. Cyclone Carol was a raging tropical cyclone which struck Mauritius in 1960. It is considered as one of the most devastating tropical cyclones of modern times in the Indian Ocean. I still remember the measures we took to prepare ourselves for the onslaught, boarding up windows and doors, getting in food supplies and drinking water for during the storm and for the aftermath. Tools, equipment and my bike were locked up in a storeroom adjoining the house. I begged my parents to let me keep my bike in the house during the storm, but they insisted that it would be better off in the storehouse. I was not convinced that it would be safe there, and I was right. The violent wind completely smashed the storehouse and, when it was safe to do so, to my horror I discovered that my bike had completely disappeared. We searched everywhere for it amongst the devastation, but it was nowhere to be found. I openly blamed my parents for this. I was heartbroken, and insisted that I did not want a new bike, resentfully declaring that no bike on earth could replace the beloved one that had been lost.

Cyclone Carol hit Mauritius Island on 28 February 1960. Destructive gusts and squalls ripped up everything on its way for more than 14 hours. It is assumed to be the most powerful cyclone ever recorded in the South-West Indian Ocean with wind gusts of 256 km/h, making at least 300,000 people homeless and destroying 40% of Mauritian main economy at that time, which was the sugar cane crop. There were over 1700 casualties; 42 people were killed and 95 seriously injured. Carol left the island in complete chaos.

Chapter Twenty One

Twenty-Five Years Later — My Friend Sabani

When the countries of East Africa became independent in the early ’60s, my father thought it would be wise for the four of us to emigrate to England. The rest of the family stayed behind, even though my grandfather had lost all his property when it was nationalized. All the labourers, domestic servants, gardener and askari were laid off; even our cook Sabani was let go.

My uncles and my grandmother and grandfather moved to Nairobi in Kenya, and one servant, but not Sabani, went with them. Many years later, on a trip to Kenya, I stayed with one of my uncles and his wife. My grandmother lived with them for the last years of her life. When she died no one told me for several months. This upset me deeply and I was angry with my uncle and never forgave him. I travelled to Kenya that year.

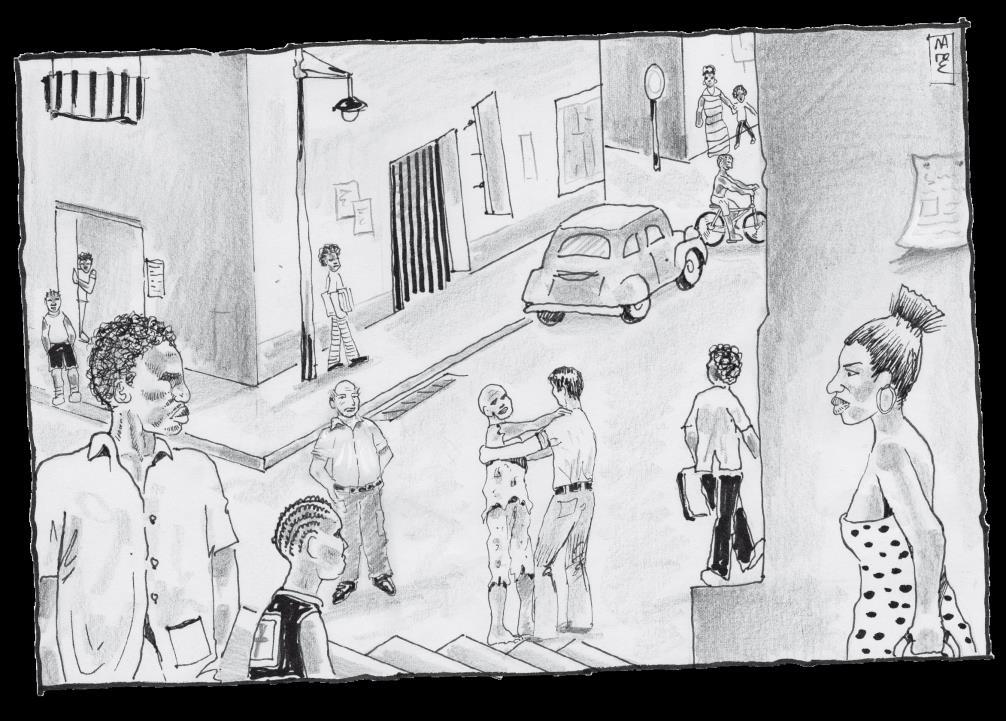

One day, walking through the centre of Nairobi with my uncle, I couldn’t help but be aware of the contrast between some wealthy locals and the misery of some unfortunates who were begging in the street. While walking along, chatting as we went, I saw a poor, elderly African, who was obviously begging, stand up to greet my uncle. As the man came close, my uncle threw some coins into the open palm of this very sad looking man who, when he saw me, started to talk urgently in Greek. He said: ‘My dear boy, you have Memsahib’s eyes’. I was totally surprised. How on earth did he know my grandmother? Where did he learn to speak Greek? I tried to figure out who this man could be, in such misery, wearing torn clothes and walking barefoot. I turned to my uncle to ask, but it suddenly came to me. I knew this man. How could it be possible that he had become a beggar? I grabbed his hand and almost in a whisper, my voice hoarse, I uttered his name. It was my friend Sabani.

We both shed emotional tears. ‘I have no baklava to give you,’ he said. I responded, smiling, my lips quivering, ‘Sabani, that doesn’t matter at all; I am so happy to see you.’ I slipped my other hand into my pocket, and drew out what cash I had, bank notes and coins, and tried to squeeze it all into Sabani’s hand. He backed away shouting ‘Hapana! Hapana!’, meaning ‘No! No!’ I forced the money into the palm of his hand. My uncle wandered off; he called out to me saying it was time to go. Then Sabani knelt and pulled my hand to touch the crown of his head. This was a sign of subjugation and respect. Of course, I pulled him to his feet at once and embraced him. We created quite a stir on the street, people gathered round to watch the scene. They were struck by the fact that a European was embracing a ‘black’ and what’s worse, a beggar!

I must say I found the smell of Sabani’s body quite unbearable. He smelt of sweat. I remembered the times we had embraced in my grandmother’s kitchen. He always wore a white apron and smelt of Grandma’s cookies, not sweat and exhaustion. Sabani was very happy and we chatted for a few minutes. I helped him sit down on the pavement. He was exhausted now with all this excitement; he began to caress my face: ‘Asante, asante, bwana mkuba!’ (Thank you, thank you, great sir!). It is an honour for a white European to be addressed in this way. We separated, saying our goodbyes. ‘You have your grandmother’s eyes,’ Sabani repeated.

I was so very upset by Sabani’s predicament. On our way home I asked my uncle if something could be done to help Sabani. We owed it to my grandmother’s memory. He said he would try. But Sabani’s fate was already decided.

A couple of days later I went to Nairobi on my own to see Sabani. I had some money to give him. To my disappointment Sabani was not in his usual place. I went into the nearest store to ask after him. An Indian shop assistant approached me, and he told me that Sabani had died the previous day exactly where I had seen him. He said he had seen Sabani trying to stand up and as he did so he had collapsed on the street. The shop assistant told me he had run to try to help Sabani get up, and when he reached him Sabani had said something in a very feeble voice. It sounded as if he was saying ‘Agori mou’ (this means ‘my boy’ in Greek). I thanked the man and left.