4 minute read

Chapter Four

Shoes, Boats and a Dangerous Acacia

One of my favourite bike rides took me to the muddy river where lots of wild animals were to be seen quenching their thirst. So visiting the river was always full of incident. I might see a hippo swimming, seemingly unaware of my presence, or perhaps a herd of gazelle quietly drinking from the riverbanks. Of course, such places are not without danger, so I kept my visits clandestine and never mentioned them to my family.

Advertisement

There had been clues as to my whereabouts: both my grandmother and mother noticed that I often returned home barefooted. ‘Where have you left your shoes?’ they would persistently enquire. I preferred not to lie, so I chose to remain silent on this matter. They were right to be concerned about my frequent loss of footwear.

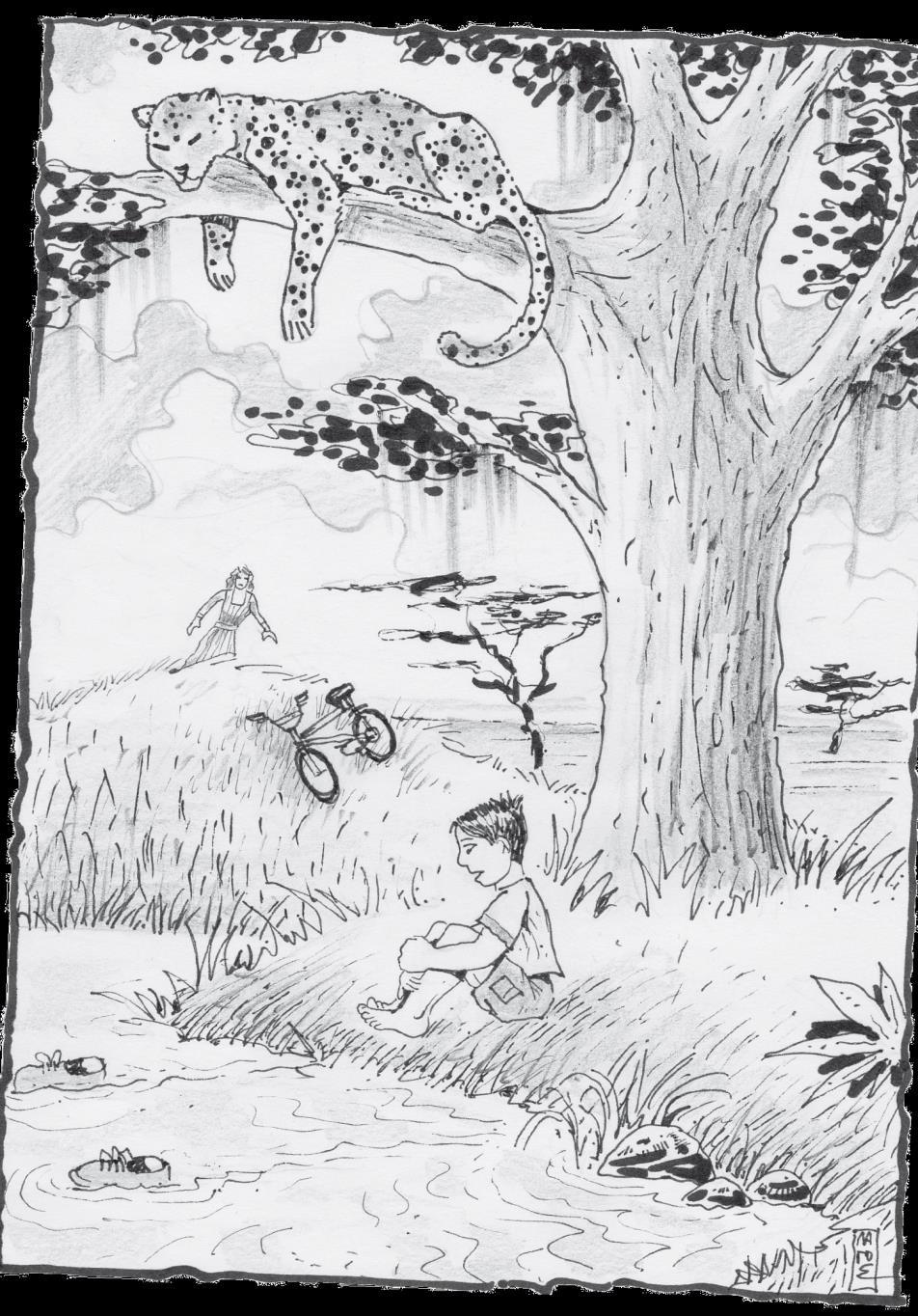

Whenever I went to the river, I would leave the bike at the top of the hill and descend on foot to the riverbank, the slope being too steep to negotiate on two wheels. Beside the river there was a large acacia tree in whose shadow I would sit, remove my shoes and splash my feet in the water. Then I would carefully place the shoes on the water’s surface and watch them drift away with the current, like little boats. I observed that at first the shoes moved slowly on the water, but once they reached the middle of the river they would speed up, floating faster and faster away until they disappeared from view. I managed to lose several pairs of shoes while entertaining myself in this way.

Inevitably, however, my secret was eventually exposed and my visits to the river came to an abrupt end. One day I set off as usual, but, unbeknownst to me, my mother was on my trail. I left my bike on the hill as I normally did, went down to the riverbank and settled in my favourite position beneath the acacia. As I collected stones to throw into the water, I heard a sweet voice calling me: ‘Come here, my boy; I want to show you something. Don’t run, just come, come!’ To my astonishment I saw my mother standing next to my bike on the hill as she beckoned me to climb up and go to her. Almost in a whisper, she insisted: ‘Come, come!’

I got up and moved toward her, slowly climbing the hill. Beyond, I noticed the Land Rover with the driver sitting inside. When I got near her, she suddenly grabbed me and embraced me tightly with great relief. It was clear that something terrifying had happened. With a trembling voice she prompted me to look towards the acacia. ‘Look there in the tree. What do you see?’ I turned to look towards where I had been a minute earlier… and was shocked to see a leopard lying on a branch of my acacia! There I had been, oblivious to the danger; happily throwing stones into the water, and all the while the predator had been sleeping in the tree above me!

Leopards often search for a safe place to rest or sleep by climbing up a tree and lying along a branch. Sometimes they even drag their dead prey up to ensure that no other animal attempts to steal it.

My mother signalled to the driver to come and get my bike and to load it. We headed to the vehicle and drove back to the house. No one spoke throughout the drive home, which brought home quite clearly the grave danger I had been in.

Chapter Five

My friends the watoto

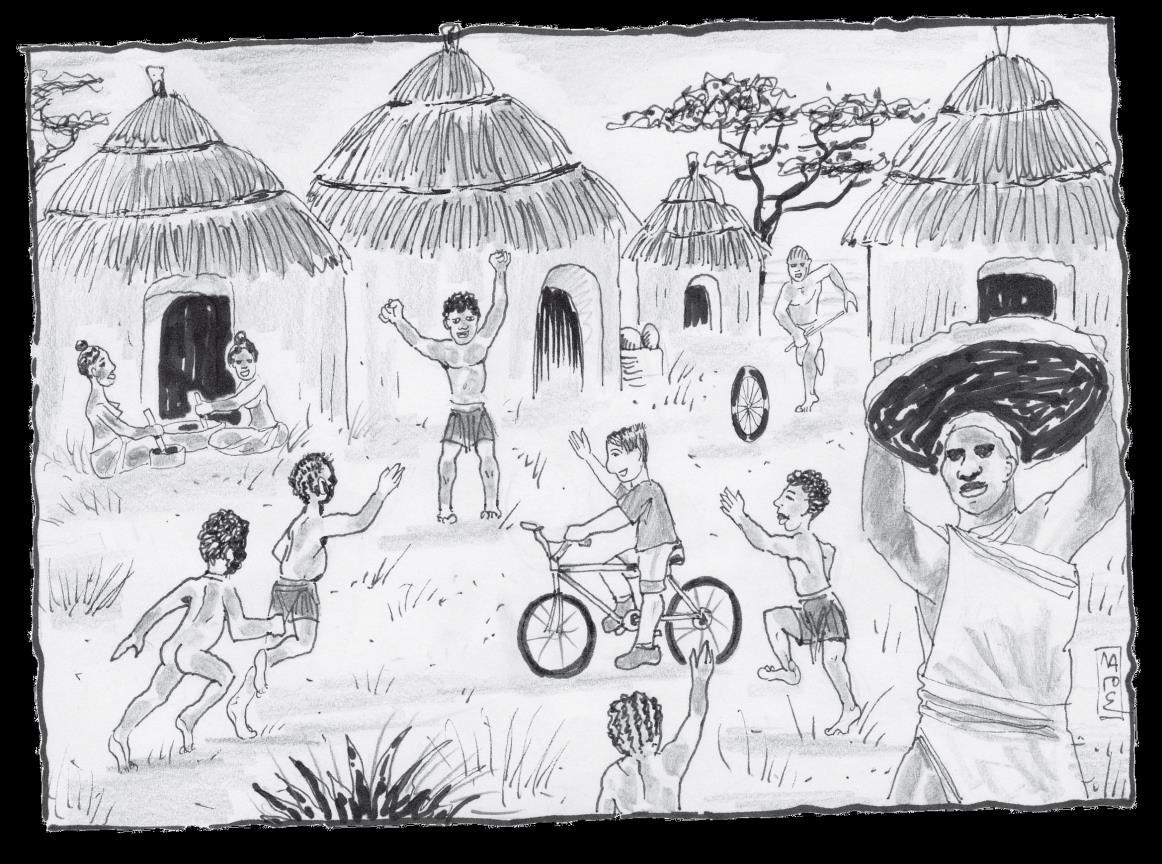

I often escaped with my bike to play with the watoto(*4). These were the children of local farm workers, who lived at the shamba(*5), the settlement that was built for their families. It was quite a way away from home but within the boundaries of the estate. I’d follow the dirt tracks through the vast plantations, so it didn’t take too long to get there. I had a khaki canvas bag, which I used whenever we went on family safaris into the bush. I’d use it to take along my toy cars, toy soldiers and anything else I needed. It wasn’t easy to ride with this bag slung over my shoulder, but with a little perseverance I was able to reach the shamba.

I always felt slightly disappointed with the watoto because they were never terribly impressed with my toys and always seemed to lose interest in them very quickly. This never failed to upset me since I had gone to such trouble to bring them. They preferred their own toys: soil, mud, sticks, stones and even an old bicycle wheel which they would roll by pushing it with a stick as they chased it. However, they were impressed with my bike. As soon as they saw me, two or three watoto would run over and climb on. It was great fun for everyone, especially when we lost our balance and fell down.

When we had enough of games, we would take a watango, a gourd commonly used as a canteen for water, and go to the great earthen castles built by mchwa (termites). By digging holes in the towering termite nests we would capture our prey, the larvae which resembled caterpillars, and fill our watango. The panic-stricken termites angrily bit our hands, while other teams of worker termites raced out of their fortress to chase us and bite our feet. We had to make a run for it to get away from the infuriated insects. Once back at the shamba, we would singe the termite larvae over a fire and eat them. This was an important food source for the indigenous people.

We also looked for ant nests, especially those of the red ants, which were the tastiest. Later I learned that their sharp sweet taste was due to the formic acid that ants secrete. This acid had interesting side effects: your guts would fill with gas, and so you farted like a carthorse after every meal of ants. When I returned from the shamba, I enjoyed trying to get attention by farting around the house. My grandmother was unimpressed and merely remarked: ‘You’ve been eating ants again’.

(* 4) children in Swahili.

(* 5) group of African houses, farm