11 minute read

Chapter Sixteen Swaziland

My life on my grandfather’s estate was interrupted a number of times, when my mother, my brother and I accompanied my father on some of his various distant civil engineering projects. Each time we left I was in tears because I was leaving my beloved grandmother. She always waved a white handkerchief until we were out of sight.

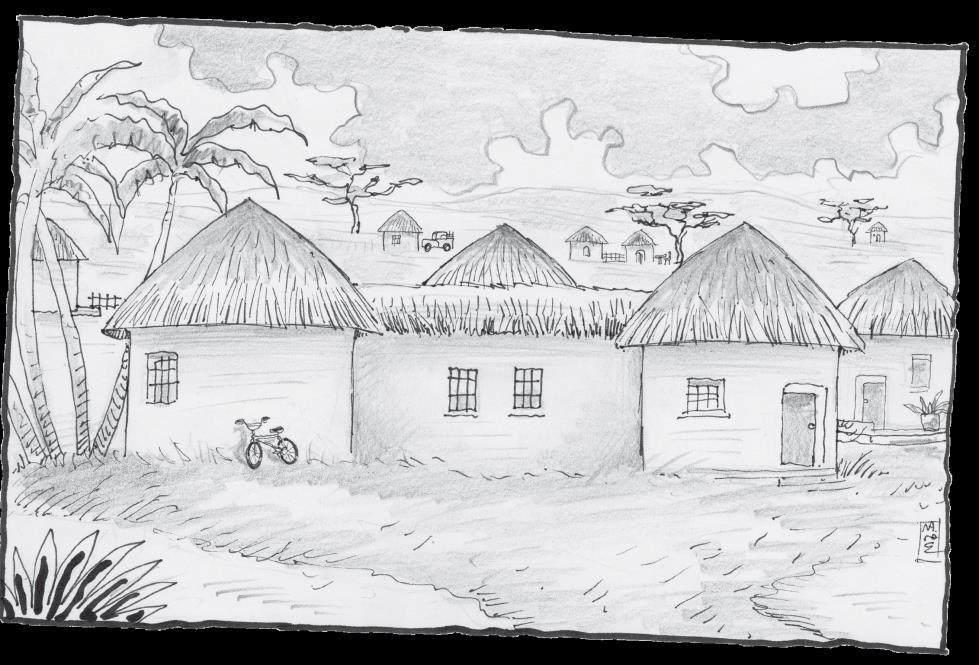

In Swaziland we lived in a compound provided by the construction companies for European employees. The houses, which were like round cottages, were known as rondavels, a word of South African origin, in the language of the Boers, Afrikaans. The rondavels were a westernized version of the traditional African round hut with a thatched roof. Often, to increase the living space available, two, three or more rondavels were connected by branch- and reed-covered walkways. The building we lived in had three bedrooms and a bathroom in one rondavel, which was connected through a corridor to a second rondavel. This second section had the lounge and dining room, while the third rondavel housed the kitchen and laundry and had storage space. There was also a garden, which was shared with the other four houses in the compound.

Advertisement

Once we had unpacked and got settled, the staff returned to the estate in Tanzania with one of the Land Rovers and the truck. I was impatient to start my explorations with my new bike. By early evening, I had got to the home of the owner of this estate, a very large sisal plantation. I spotted a fenced-off area with several hens. At home we had a chicken coop but I was never really interested in it perhaps because I took it for granted.

I returned to our new home to eat and, totally exhausted, went to bed for the night. The next morning I woke up to find my mother with a young servant in the kitchen, preparing breakfast. My father was already up and sorting through his paperwork. I loved to look at the plans and designs of his projects. Sometimes, when he was in the mood, he would give me crayons and paper and involve me in what he was doing.

While my mother fed my brother, I sat down to a hearty breakfast of pancakes, fried eggs and fruit. When my father left, I grabbed my bike and set off to have another look at those hens. I was curious to see how chickens laid their eggs.

I saw someone collecting eggs from an oblong nesting box with many trap doors which seemed to be attached to the coop. As soon as he left I approached and opened a trap door to peek in. Disappointingly, I saw straw and nothing else. No chicken, no egg! Frustrated, I decided to continue on my bike ride to explore the estate. I arrived at the sisal plantation with great difficulty. The dirt road had a surface of powder-like dusty soil, which made cycling impossible. The wheels sank deep into the dust, but I persisted and eventually got to the sisal plantation. The workers were already at work; they had been busy since the early hours among the endless rows of sisal, cutting off the spiny leaves from the plant with a panga (an enormous knife-like tool, more like a short sword with a wide blade). This is a tedious task and you have to be careful when chopping off the long leaves, because there are spines that cause nasty, painful scratches, which can get infected.

The workers gathered the leaves into piles by the dirt road to be loaded on to trucks. These would then be transported to a factory for processing. The strong fibres from the leaves were used to make rope. I got off the bike to hang about watching the workers’ skill in using the panga. I watched one person in particular. He was about thirty and, like everyone else, he was singing as he worked. They all worked in time to their music. This is what the workers on my grandfather’s estate did too. Rhythm and song is in the blood of the indigenous people. I did not like the term ‘black’ to denote the native people. In the colonies it was the usual way to distinguish the ‘native’ or ‘indigenous’ from the ‘white’ mzungu, the Europeans. I felt that we were all Tanzanians regardless of our origins or skin colour.

Pushing my bike, I got closer to the workers. They wore only khaki shorts and were barefoot. Their bodies were slim but muscular, their skin dark brown and smooth. I always admired the perfect lean bodies of the Africans. At my grandfather’s estate, the topless young women had slender figures and perfect breasts. They spent hours labouring in the heat, bending over to plant and dig tirelessly. In Swaziland I saw topless women carrying heavy things piled up on their heads. They walked with such ease and perfect balance. All this heavy work gave them perfect slim bodies that would be the envy of any modern young woman in the West.

One worker stopped to look at me and he smiled, showing his gleaming white teeth. He could speak English. ‘Hello, where are you from?’ I answered in Swahili as I was used to speaking to workers in this language. The young man looked puzzled and I realized he did not understand me I hadn’t realized they don’t speak Swahili in Swaziland so we continued our conversation in English. However, the supervisor, a European, yelled ‘Get back to work!’ and the young man winked and smiled, then continued with his chopping and singing. It was time to leave.

Trucks were passing by raising a suffocating dust from the dirt road. I made my way back with my wheels sinking into the soft soil every now and then. I reached the estate owner’s house, which was large, consisting of seven to eight rondavels, with an impressive verandah that followed the curves of the round buildings. I saw tables with chairs and sun loungers. There were potted tropical flowering plants everywhere. It was very beautiful. Suddenly I heard a growl coming from the verandah. My heart stuttered as I tried to work out where the sound had come from. I saw a huge black dog moving along the verandah; I was scared. I was more frightened of large domestic dogs than wild animals. At once I started to speed away on my bike. My hands were shaking as I gripped the handlebars and I pedalled desperately. I was sure that I would be pursued, but when I turned to check I heard a male voice calling sternly to the dog; I did not understand the language spoken, it may have been Afrikaans.

I was still panting when I reached the chicken coop, where, very hopeful and with great care, I opened the nest box doors. I could hear scratching in one nest box, so, very slowly, I lifted the lid and was delighted to see a brown hen scratching the straw into a comfortable nest so she could sit and lay her eggs. I held my breath and watched. She had her tail towards me and she made the ‘qua-quaaaa’ sound hens make when they are about to lay. At last the magical moment had arrived. I saw the brown egg ease out and in a few moments it dropped gently onto the straw. I was overjoyed! I hoped to eat this egg in the morning at breakfast.

Once, people lived in harmony with their environment. There were no excesses, over-consumption, industrialization or greed, and the small communities of ‘primitive’ inhabitants were self-sufficient. Then the white people came and everything changed: the wealthy nations of Europe sent colonists to Africa who carved up the continent for their own use. Explorers of sub-Saharan Africa, such as Livingstone and Schweitzer, innocently opened the door for exploitation, and so in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the scene was set for one of the most extensive looting of resources that has happened in modern times. The colonial powers became wealthy by plundering the natural resources and underpaying the local workers. In those early days, most mzungu (Europeans) lived lavishly in their privately owned estates, with plantations, large houses, servants, labourers and guards at their service.

Today, several countries in the continent have corrupt regimes supported by the West. There is poverty, misery, disease and often famine on a large scale. This situation was inherited from colonial Africa, and I feel upset that I could do nothing to protect my beloved homeland from the ills that beset it. Now harmony with one’s environment is a distant memory and Africa, once teeming with wildlife, watches as its many species gradually disappear.

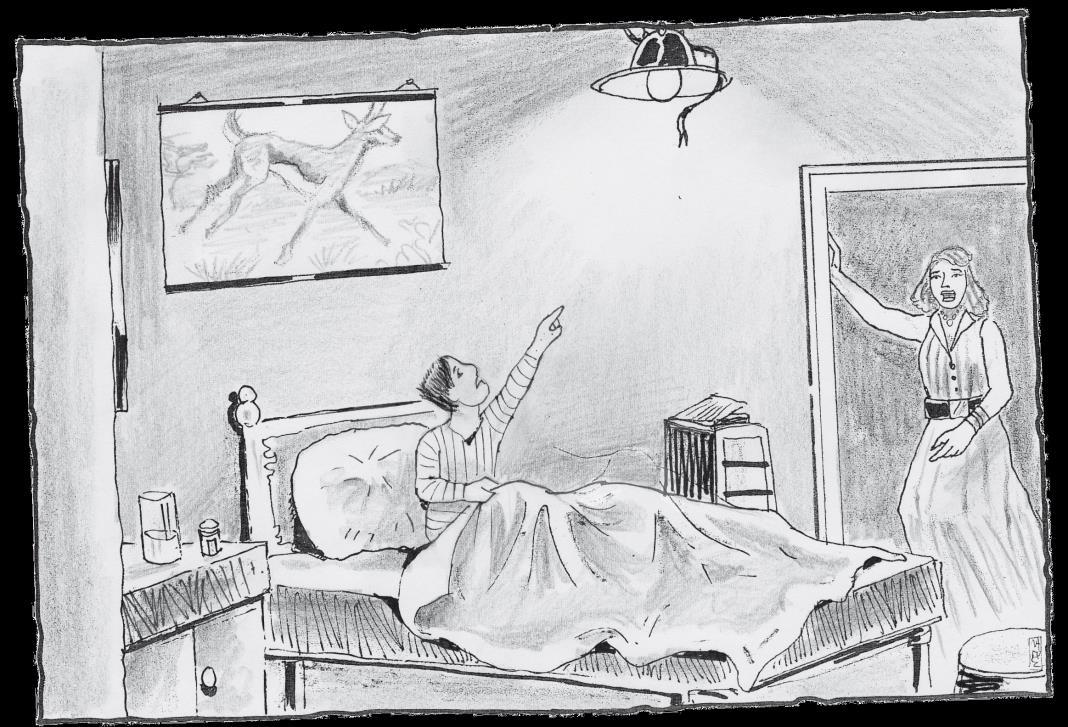

Once I had high fever and I had to stay in bed. I think it was measles. We were supposed to be leaving for Rhodesia, where my father would be working on the huge Kariba dam project, but we had to put off the journey for a few weeks. I was sleepless and lying in bed, so I created imaginary designs on the whitewashed ceiling. I noticed that the lampshade hanging from the middle of the ceiling seemed to be moving oddly. Motionless and weak from the fever, I could not focus properly and my eyes felt heavy, but it seemed to me that a thick cable had come loose and was hanging from the lampshade. It was moving strangely from side to side. I shouted as loud as I could ‘Mama, Mummy!’ Within seconds Mama was beside my bed looking at me with compassion and affection. Before she could speak, I raised my hand and pointed towards the ceiling. My mother looked up and responded like lightning. In a fraction of a second she had lifted me together with my bedclothes and literally dragged me towards the door, shouting for the servant ‘Boy! Boy! Come quickly!’ (It was customary to call servants or waiters ‘boy’ at that time).

Mama lay me down in the guestroom and I immediately fell asleep. Days later, when I had recovered, I learned that it was in fact a snake hanging from the lampshade. The brave servant made sure it was quite dead; he wanted us to be safe. Most African snakes are poisonous, although I never found out if the one hanging from my light was too. There was an unwritten rule in Africa that any snake or insect that came into the house had to be killed, to keep us safe.

Chapter Eighteen Full Speed Ahead for Kariba

We got ourselves ready for our Safari to Rhodesia, and a large truck came to get our stuff. The trip was uneventful this time. We left Swaziland before dawn and travelled through South Africa on good paved roads, arriving late the following day. My little brother kept crying on the journey, I think it was just too monotonous for him.

In Kariba we lived in a small, prefabricated house. There was a huge construction site for the Kariba dam project, and a small township grew up around it. A consortium of construction companies was building the dam; the largest company was Italian and had also built the township. There was a school, a hospital and shops for all the European staff.

We had no servant. Most of our neighbours were Italian, and I soon found new friends to play with amongst their many children. I also went to my first school in Kariba. A school bus took us to school in the morning and returned us home in the afternoon. Most lessons were in Italian and only some in English, and so I quickly learned to speak basic Italian. I was the only kid to have a bike. What was more, the roads were hilly in the township and it was tough cycling, so I gave up my solitary cycling in favour of playing ball and other games in the company of my new friends.

In Kariba I ‘grew up’ and became more mature. I learned how to be sociable and to be aware of others. Being at school brought me into contact with children of my own age. Of course, I missed the farm and my grandmother, her cooking, her games and reading and writing lessons. I was almost nine years old and it dawned on me that I had started school a lot later than everyone else. I had had very basic tuition with my grandmother and on occasion with my father and uncles. I had learned arithmetic, and how to read and write Greek and English. In the sitting room of our farmhouse at the estate there was a library with numerous books and encyclopaedias. I was fascinated by the illustrations and maps, travelling in my imagination around the world. On the farm the only contact with other children was with the watoto at the shamba.

In Kariba I learned to play and socialize with other European children; it wasn’t easy for me because I had to learn to be more sociable, to make compromises and to share. It was brought home to me that I wasn’t the most important person in the world, and that others had needs and opinions as well. In spite of this, because I was more independent, more determined and more daring than anyone else, I always ended up as the leader in our games. I fell in love with a pretty Italian girl and never missed an opportunity to hold her hand. I even dared to kiss her on one occasion and shall never forget how I felt when she responded positively.

My brother was only two years old and I was still not allowed to play with him because he was so young. All my mother let me do was hold his hands or tickle his tummy, which made him smile. I liked people who smiled. All of my African friends (the watoto) always smiled.

When my father’s contract expired with the consortium in Kariba, he got a job on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It was decided that we would go there.

Mama, my brother and I first returned to the estate to stay for a while before saying our goodbyes, because the political situation was becoming very uncertain due to claims for independence.

We would not be returning to Tanzania after Mauritius. We took a flight from Lusaka in North Rhodesia (modern-day Zambia) to Nairobi. Our stuff went by truck back to Tanzania. The flight was with a very noisy Dakota aircraft. One of my uncles came to pick us up from the airport in Nairobi, and we stayed one night at the famous Norfolk Hotel downtown.

I was eager to see my grandmother; it had been almost two years since we had left for Swaziland. The following day we would be back home at the farm.

The Kariba Dam is a hydroelectric dam in the Kariba Gorge of the Zambezi river basin between Zambia and Zimbabwe (formerly North and South Rhodesia). It is one of the largest dams in the world, standing 128 m high and 579 m wide. Construction on the dam began in 1955 and it took 25 years to complete at a tremendous cost. During its construction, no less than 86 workers lost their lives. Thousands of large animals were threatened by the rising water and had to be rescued in what was known as Operation Noah, a wildlife rescue operation that lasted 5 years. Over 6000 animals (elephant, antelope, rhino, lion, leopard, zebra, warthog, small birds and even snakes) were rescued and relocated to dry land.

The creation of the reservoir forced the resettlement of about 57,000 Tonga people who had been living along the Zambezi in both Zambia and Zimbabwe. The government of the time made some attempt to implement sustainable farming projects for the production of cash crops. Unfortunately, they neglected to make any scheme for the irrigation of the crops. Schools, dispensaries and hospitals were to be built close by. Nothing like that happened. It is doubtful that much resettlement aid was given to the displaced tribespeople. Today most of them still live as refugees in camps. They live in unproductive problem areas, some of which have become so seriously degraded that they remind one of the areas on the edge of the Sahara Desert. Kariba remains the worst dam resettlement disaster in African history.