22 minute read

Chapter Eleven

A Sad Farewell to my Grandfather

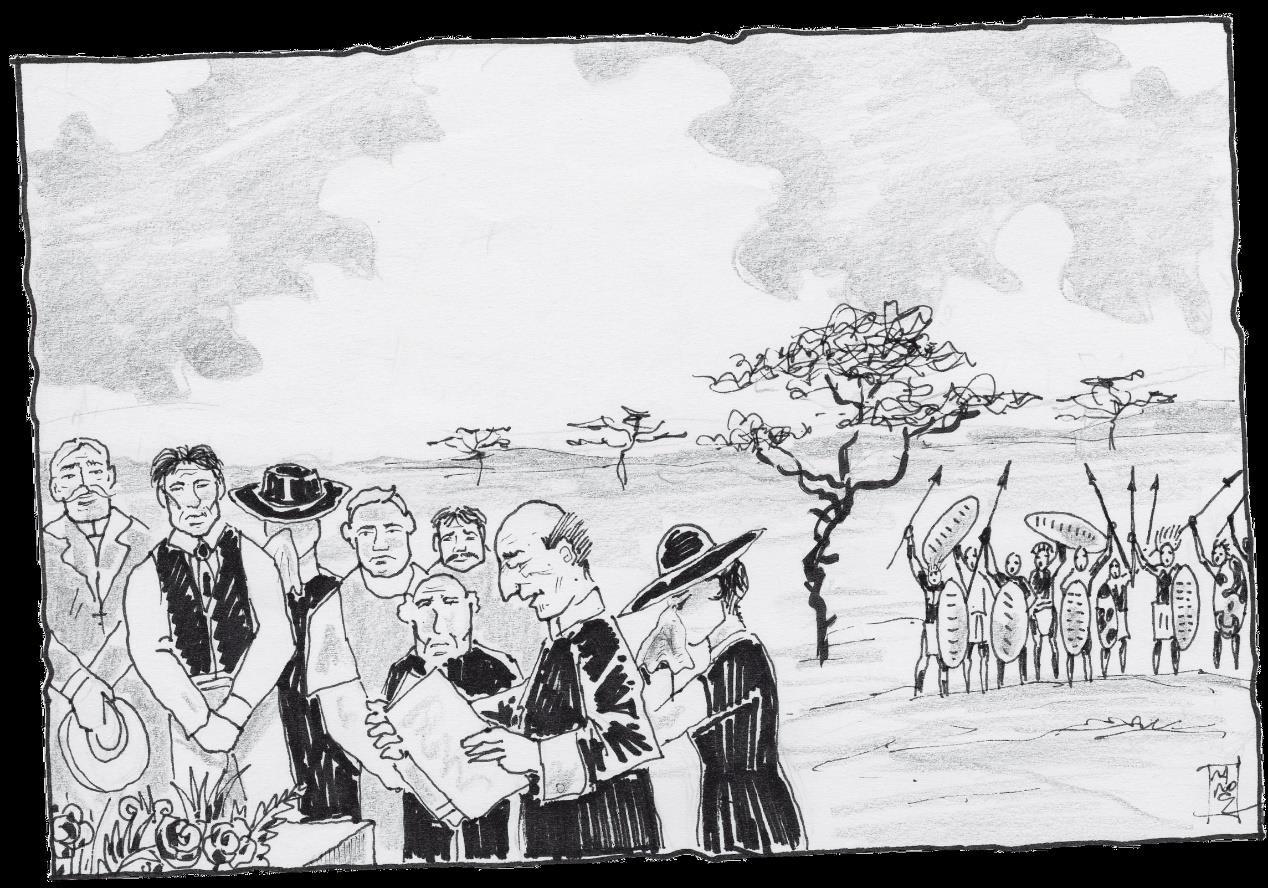

Grandpa sometimes told me about the stars in the sky and showed me the constellations. At night-time the hum, buzz and hiss of insects was everywhere around us. I got the idea that the stars made this sound. My grandfather explained that the stars are silent and it was insects that made those noises. I didn’t want to believe him, but I knew he was right because my grandfather knew everything. He spoke many languages: Arabic, English, French, Italian, German, Swahili, Masai and several tribal languages of East Africa. Tribal leaders would come to meet my grandfather, to negotiate terms of employment for members of their tribes to work on the estate. They would stand in front of the house in the garden, and not come up the steps to the verandah. They just waited until someone from the house noticed them.

Advertisement

My grandfather knew that inviting a black person to come into your home went against all the absurd unwritten rules of colonialism. The house owner had to come meet them outside. My grandfather was unorthodox and would come down and sit with them on the grass in the garden. The conversation always began with an exchange of greetings and wishes, and then turned to the discussion around the issue concerned, diplomatically and indirectly. The discussion concluded with some form of agreement, followed by farewells and good wishes from all sides. Tribal leaders in the area respected my grandfather because they knew that he looked after his workers and their families well. He was one of the few landowners who had running water in the shamba, providing water for each home and arranging medical care for his workers and all those living on the estate. My grandfather also showed respect by making an effort to learn the dialect of each tribe so that he could communicate better with them.

When Tanzania became independent, my parents, brother and I left the country. My grandfather and grandmother continued to live on the estate until it was finally nationalized by the new government. They then moved into my eldest uncle’s house in Nairobi, Kenya. Grandpa fell into depression, and within a few years he died. Grandma wanted to bury him in Arusha, and so the funeral was held at the Anglican Church there, since the Greek Orthodox Church had closed. The service was attended by many people, including former workers from the estate dressed in their best clothes; there were also a group of Masai tribesmen in their traditional attire. Many of them had walked many miles to honour my grandfather. Throughout the service and burial they stood silent and expressionless outside the church. When my grandmother came out into the churchyard, the Masai who were amongst the Africans present raised their tall spears and shields in respect. My ailing grandmother raised her head to them and whispered ‘Asante’ (thank you). The Africans then turned and walked the miles back to their homes and shamba in silence.

Chapter Twelve

A Beach Hut by the Indian Ocean

My grandmother and I would spend fifteen to twenty days a year on the shores of the Indian Ocean. My uncle would rent a beach hut with very basic amenities on an endless sandy beach washed by the ocean’s waves. I loved to fall asleep listening to the rhythm of the waves.

Naturally, I had my bike with me, though of course it was impossible to ride it in the sand. Luckily, behind the hut there was a well-trodden dirt road running parallel to the shore that led through a grove of palm trees to the nearest shamba. I often went to the shamba. Whenever I arrived on my bike the watoto and women clapped rhythmically to welcome me. As I cycled through, the watoto would run after me laughing. Sometimes I would watch local fishermen as they came ashore with their boats. They pulled their nets up and spilled their catch on the beach and I was dazzled by the variety and colours of the fish and other sea creatures they had caught.

The beach was stunningly beautiful and very different from the environment of the farm. The contrasts in colours were striking: the deep blue sea, white waves crashing on the distant reef, the dazzling light and the white sand, backed by dense groves of palm and all this under the magnificent blue African sky with clouds scattered in a characteristic pattern just above the horizon.

My grandmother cooked simple meals during our stay at the beach hut. She did all the cleaning, washing and tidying herself, as we had no servant with us. We ate mostly fish and fruit. My grandmother would often buy fruit, vegetables and fish from passing peddlers. Sometimes she bought crab from the fishermen, which she boiled in seawater on an outdoor wood stove that was in the yard of the beach hut. Very often we had visitors, mostly Grandma’s friends from nearby Mombasa. At the end of our stay, my uncles would visit for a few days to swim and relax before taking us back home.

Back at the estate, I missed the sea a lot, even though we were near Lake Duluti where we could take a dip. There were water-skiing facilities there and it was very popular with Europeans. The water at the lake was safe and crystal clear, but I much preferred the sea. I was entranced by the coastal environment, the bleached sands, the salinity, the palm trees with their fronds rustling as they swayed gently in the breeze this was magical to me.

Chapter Thirteen Hunting Safari and a Sad Death

When my uncles realized that there was a lot of money to be made by arranging safaris for trophy hunters, they started to do it more and more. In order to hunt you needed a special licence from the authorities. There was a tiered price system for each animal depending on the species a prospective hunter wanted to kill.

Once I went on such a safari. Hasani, a servant whom my grandmother trusted, was sent to look after me. Our expedition set off, including a convoy of four Land Rovers and a truck, a cook, two servants, four guards-cum-hunters, my two uncles and their girlfriends, two American customers and Hasani and myself. It took us almost a day travelling on the dirt roads to get to the area of savannah we proposed to hunt in. This African landscape is all too familiar from countless films and photographs in tourist guidebooks, but it is one thing to see it in pictures and another to actually experience it in real life. Not only do you see the landscape, but you also hear the sounds, smell the scents and actually feel the pulse of the wilderness. It is an immense vastness, a never-ending horizon: a limitless savannah with its huge herds of wildebeest and its acacias acacias whose ferocious thorns do nothing to deter giraffes and elephants, which reach their tender leaves with apparent ease, oh so deftly plucking and eating them.

The dormant volcano Mt Kilimanjaro with its snow-capped peaks was the backdrop to an area of lakes and waterholes that lured myriads of birds, flamingos and mammals that would approach to bathe and drink and share the water with respect.

On our way there we met a rhino. He felt threatened by our convoy and tried to bash one of the vehicles with his horn. The drivers were experienced enough to manoeuvre the vehicle so as to stay out of trouble. A bit further down the track a herd of elephants stubbornly held their position in the middle of the road, their matriarch flapping her enormous ears as a warning that we were a threat to them. The only thing you can do in such a situation is be patient and wait until they leave peacefully. We never ever drove up to an elephant hoping it would give way: elephants always stand their ground and can become very aggressive, and they are large and powerful animals that can easily overturn a vehicle or trample a person to death. Beyond the elephants, three ostriches crossed the road, completely ignoring our presence.

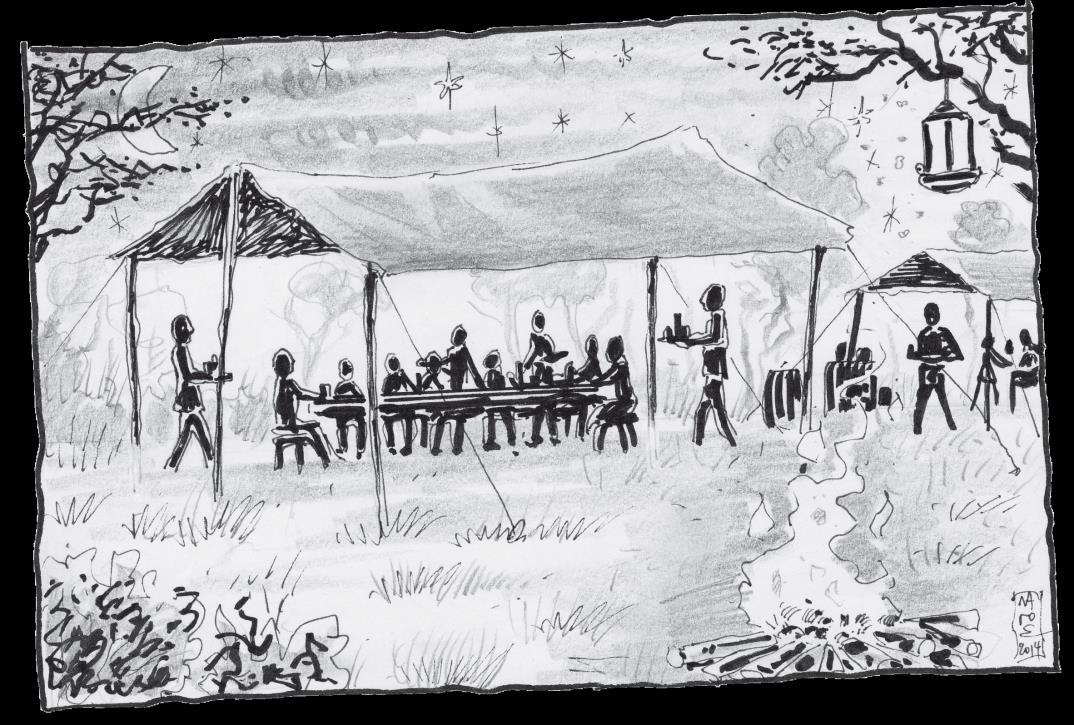

We finally arrived at our destination and immediately began unloading and setting up the tents at a suitable site; the servants lit a fire, paraffin lamps were hung on branches of trees, inside the tents and on the tables. Water tanks were positioned near the kitchen and the shower tent. Immediately the cook began preparing our meal, while the servants laid the table for dinner. Meanwhile, my uncles were planning the next day’s hunt with the American customers. It would start at the break of dawn the next morning, even earlier if they could. Two scout hunters had already set off to search for signs and traces of animals that were destined to be their prey the next day. That was how you knew what animals were around and in which direction they were heading. Once the scouts returned, it was time to eat. The servants would eat on the ground in the kitchen area after they finished serving us. Our temporary dining room was a long table with folding chairs set up in a huge tent with open sides.

My grandmother had prepared burgers for us to take with us, and they were cooked on the fire. Also on the menu were baked potatoes, salads, fruit and a dessert. At seven in the evening Hasani and I went to our tent, which had a partition; I slept on a camp bed in one section of the tent and Hasani slept on the ground in the other. Outside the tent there was a guard sitting on the ground. The four guards took shifts during the night to keep us safe from wild animals, thieves and poachers. I slept peacefully, but now and then I heard a cry or a roar, the chorus of insects and Hasani’s deep breathing as he slept. Outside the tent two guards spoke to each other in undertones.

At dawn, when I woke up, Hasani was already up and about, and he took me to wash at the canvas sink outside the tent. I noticed that my uncles were missing, along with the Americans and two guards. I was afraid that the hunt had already started.

I sat at the table at the big tent, where my uncles’ girlfriends were already seated, chatting and drinking coffee. We smiled at each other coldly but did not exchange a word. I grabbed some freshly cut mango and ate it noisily, juices dripping from my mouth. Then Hasani helped me spread butter and jam on a slice of bread, which I bolted down too my grandmother, was not around to notice my table manners.

Hasani watched me like a hawk, so I couldn’t move around the camp freely until my uncles returned from the hunt. After some time I heard the distant sound of the Land Rovers returning, as I imagined, loaded with trophies. What a relief when the convoy arrived at the camp and I learned that they had had no success in killing an animal! They had found a herd of Thomson’s gazelles, but these, sensing danger, had run away. The Americans wanted a female Thomson’s to add to the huge collection of trophies they had back at home in the USA; they were proud of them and had boasted about them at dinner the previous night

Now, to cheer themselves up after this disappointing hunt, they all drank coffee and started to plan another outing for the late afternoon. This conversation was cut short when a hunter approached one of my uncles and whispered something to him.

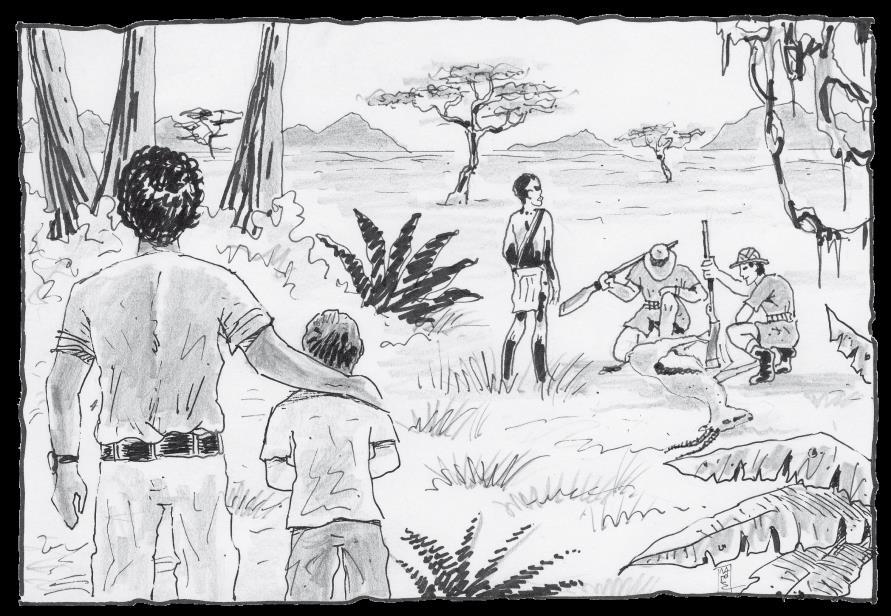

In a split second, the four hunters and both my uncles had grabbed their rifles and were moving stealthily towards some bushes not far from the camp. My uncle gestured for quiet. This was the signal. I knew that any moment an unprotected animal would appear in harm’s way. I wanted to shout ‘Uncle, please don't…’ but was silenced by the blast of a rifle towards a clearing in the bush. I stood frozen; I did not want to see the animal wounded or dead. It was a female Thomson’s!’

Experienced hunters stay still for some minutes after a shooting before slowly approaching the animal, just to make sure that it is quite dead. After the necessary wait, my uncles with two of the hunters, followed by the very excited Americans, moved forward towards the clearing. The other two hunters kept their rifles raised and aimed, ready to shoot if necessary. I saw my uncle standing where the animal was to examine it. I couldn’t see it because of the tall grass. He signalled to the two hunters to carry the corpse off to be skinned. In despair I ran and hid in my tent. Even at the relatively young and tender age of seven, I was both angry about this murderous activity and disturbed by it.

I lay on the camp bed while Hasani held my hand; he knew that I was deeply upset. To distract me from my sorrow, he lifted me up and carried me as far away as possible from the now lifeless Thomson’s. The hunters skinned the animal immediately, away from the camp. A corpse and the smell of death would attract all sorts of animals, especially hyenas and African wild dogs, which would catch the scent of blood and be drawn to the scene.

While the beast was being skinned, the Americans, my uncles and their girlfriends chatted over sandwiches and cookies and drank tea from a seemingly bottomless teapot. Everyone, it seemed, was satisfied with the outcome, except me.

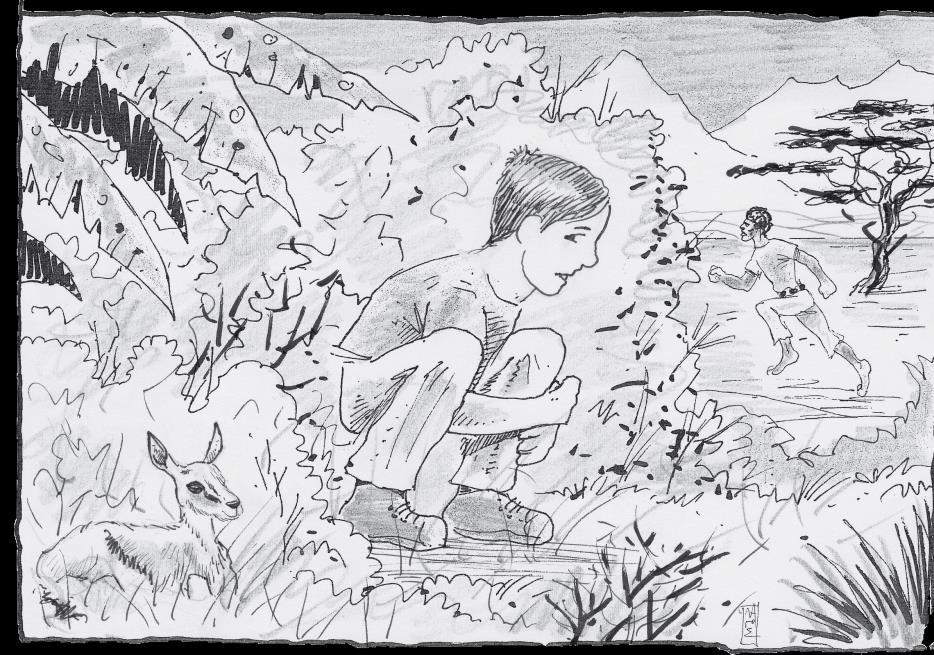

A faint bleating sound caught my attention. It sounded like a lamb, but it wasn’t. I pulled urgently at Hasani’s hand, and headed towards the clearing where the murder had taken place. We weren’t the only ones to hear the sound: everyone had stopped their conversation and tea drinking to listen and were startled when a tiny baby gazelle appeared. It was the fawn of the shot Thomson’s gazelle desperately looking for its mother. I burst into tears and begged my uncles to catch it and save it from predators, which would surely be attracted by the smell of blood. My uncle ordered his guards to chase it; I followed, pulling Hasani with me. My uncles yelled at Hasani to keep me back, but I escaped and disappeared into the tall grass. I could hear the hunters ahead of me and I started to run after them. Then I found myself in the clearing; I saw the blood-stained earth where the female Thomson’s had been shot.

The hunters were lost to view, but behind me I could hear poor Hasani calling me, panting, to go back. I turned into the bushes and hid; my heart was pounding. I crouched down low and hugged my knees. Around me I could hear voices, but I froze when I heard some rustling in the bushes. I turned my head and saw the most wonderful creature staring me in the eyes. I held my breath. It was the baby Thomson’s, its eyes glistening and nostrils dilated in terror. We stared at each other for some moments, but when I plucked up the courage to move closer, quick as a shot, he sprang out of the bushes and vanished. I got up and walked out into the clearing in search of the fawn. Far away in the savannah I saw the two hunters chasing the little Thomson’s before it disappeared in the distance.

How I wished I had my bike with me! I was confident that with my faithful bike I could have caught up with the baby gazelle, and it would have been easy to persuade it to follow me back to the camp and safety. I would have taken it home and taken care of it. I began to weep. Hasani hugged me and then carried me back to the tent at the camp. My uncle gave me a good telling off. I was never to do that again! It was dangerous to leave the camp.

Once in the tent I lay on the camp bed and said to Hasani, my eyes brimming with tears and my voice trembling with emotion, ‘I have lost a new friend!’

In the evening we all sat at the table in the big tent. The Americans were very happy, and my uncles proud. Bottles of beer were opened and wine flowed abundantly to celebrate. The grateful Americans raised their glasses and toasted my uncles. My uncle told his guests that we would be barbequing and eating the slain Thomson’s gazelle. My blood ran cold in horror, and I shouted that I wouldn’t eat the meat. Everyone at the table burst out laughing: they thought I was being cute. But I insisted that I would not eat it. My uncle then threatened that I would not get any trifle, which he knew was my favourite dessert, if I didn’t eat the main course. ‘Then I won’t eat anything’, I replied stubbornly. My uncle said ‘If you don’t eat the main course you will never become a man!’ I replied quietly, with my head bowed, ‘Then I don’t want to be a man.’ This made everyone laugh even more, but Hasani, who was standing behind me, let his hand rest on my shoulder in sympathy. I did not eat any dinner that evening, on principle.

Later, Hasani secretly brought me a plate of trifle and a spoon to the tent, offering them to me with a kind smile. I can still taste that trifle today. Its sweetness consoled me for the bitter feelings that filled my heart, and comforted me for the loss of the little friend who ran away in terror. Best of all, it made it possible to ignore the loud voices and laughter emanating from the big tent

Chapter Fourteen Kisumu and my brother

I was five years old when my brother was born. He was a tiny baby and had health problems at first, though he soon got over them. My mother was very busy taking care of the new baby, so I continued to be looked after by my grandmother.

When my brother was six months old, my father took on a construction project in Kisumu in Kenya, near the border with Uganda. All four of us moved there temporarily. It was the first time I had left the farm and I missed my grandmother. This was a period of adjustment, getting used to being under the care of both my parents. My mother had to look after my little brother, who proved to be a very quiet baby. When I approached him he would smile at me; I wanted to touch him and lift him in my arms, but she would not let me because she was afraid he might get an infection.

The house where we lived belonged to the company my father worked for. It came as a ‘package’, with gardener, servant and nanny, if needed. My mother did not want a nanny at this early stage, as she was so afraid of disease. Although she was neurotic about illness, I must admit she was scrupulous in her standard of cleanliness. She was very strict with the servant, who had to clean the house on a daily basis. The house had two storeys, with a huge garden that bordered on the largest lake in Africa, Lake Victoria. To reach the lake’s shore you had to descend some twenty stone steps.

For my birthday, my father brought me a new bike. I was overjoyed, jumping around and hugging his leg he was not too pleased as he did not like demonstrative behaviour. Although he was rarely affectionate with me, over time I realized that he loved me in his own way.

I jumped on my bike at once and began riding up and down the flat lawn in front of the house. Compared to my rides on the estate this seemed rather boring. I really wanted to go further away. As I rode through the vast garden, which was a jungle of plants, shrubs and tall trees, I realized that the brakes were not working properly; they needed adjusting. This did not stop me from riding crazily around at top speed with my new, heavy steel bike. I was a daredevil and thought I could stop by dragging my feet on the ground. I found a downhill path leading to the shores of the lake. The gardener was busy in the garden, but he wisely kept a watchful eye over me while I rode around like a madman.

I started to speed downhill; I lost control of the bike and wasn’t able to stop before reaching the first step, so I went down the first few with a thud, thud, thud. I could hear the gardener yelling and calling for my mother. I then lost my balance and so down I tumbled to the bottom, holding tightly on to my new bike, not letting go of it because I was afraid it would be lost forever if it fell in the lake. I finally stopped just a few feet from the water with the bike upside down on my chest. I felt no pain, but I began to cry when I saw my mother running down the stairs, tripping and falling down next to me. I was so scared I began to shout ‘Mama, mama!’ I couldn’t get up because the heavy bike was pinning me to the ground. Eventually, when I managed to push it to the side I saw that my mother was rubbing her ankle to soothe the pain. She forbade me to get up and so I stayed lying down.

The gardener rushed to help her get up. He then carefully untangled the bike from my legs. My mother, despite the pain in her ankle, examined me and tenderly asked me if I had hurt my head or felt pain anywhere. I did not feel any pain; at this point I was shaken and really worried about her. As I was lying on my back, I looked up at the tall trees that seemed to touch the sky. Then all of a sudden a gust of wind blew over us, shaking the trees; passing clouds swelled black and I could hear the waves lapping the shore in increasing intensity. A thunderstorm was brewing as it always did at this time! We had to move quickly. The servant also came to our aid and carried me to the house, while the gardener helped my mother to climb slowly up the stairs. I don’t remember anything after this. Apparently I fainted.

When I came to I was in bed and my father was there, with another man standing next to him, a doctor, who examined me and asked if anything hurt. It is true that some parts of me hurt a great deal. The doctor moved my hands, arms and legs and reached the conclusion that there was no serious injury or fracture, and therefore no reason for concern. He told me to drink water and sleep. I asked about Mama. My father told me that she was in her room with my brother, her ankle bandaged up. Xrays at the local hospital showed she had only suffered a severe sprain. After a few weeks, Mama, my brother and I returned to the estate, while my father remained at Kisumu for the remainder of the contract.

Adventure by the river

My father had been appointed to a road-building project, so our little family set off for Swaziland, a tiny African country. Swaziland was desperately poor then and remains poverty stricken today, even after forty-five years of independence. The situation in Swaziland provides just one example of how the harsh realities in subSaharan Africa conspire against the poor people who live there: they are oppressed by corrupt leaders who are supported by Western governments, greedy to exploit the abundant natural resources to be found there.

We set off for Swaziland with two Land Rovers and a truck loaded with supplies and equipment, just as if we were going on an ordinary safari, and with us were two armed askari, two drivers, three workers and two servants. The journey would take eight days. On the way we would stay in suitable hotels if we happened to be in a town or city, otherwise we would camp.

We were within a day of Swaziland when we were hit by torrential rain, which in Africa is a scary phenomenon. Suddenly the heavens open and it’s like trying to stand under a waterfall. A curtain of water deluges from the sky and your surroundings become invisible. The ground all around becomes completely flooded in no time at all. In the midst of this downpour, with night falling, we arrived at a raging river. Rivers in the bush are usually not spanned by bridges; in the dry season vehicles can cross comfortably. Now, however, the river was swollen with floodwater and was in spate.

My father jumped out of the Land Rover to assess the situation. He wanted to see how deep the water was and asked the workers to wade into the river with poles to measure the level. My mother, who had my brother on her lap, sat with me in the front of the Land Rover. She shouted to my father to hurry because daylight was fading. She suggested that we set up camp for the night, but my father finally decided that it would be possible to drive the convoy across. My mother shook her head worriedly; she didn’t agree.

Once back in the driver’s seat, my father adjusted the gears. I watched his capable movements with admiration. He began to tell everyone what to do and, in Swahili, ordered the workers who were sitting in the back of the Land Rover to stand up and spread their weight in order get the vehicle across the river. In the distance we could hear thunder while lightning flashed ominously on the horizon. The Land Rover began to move and my father drove carefully towards the river, twisting the steering wheel quickly from side to side and accelerating the engine. The Land Rover tilted downwards as it entered the water, and water began to seep in as we began our slow progress towards the opposite bank.

I then remembered my bike was strapped to the roof rack, and I was concerned because it was getting wet and that it might slip into the river and drift away! There was dead silence while my father concentrated; no one uttered a word. Then at some point the Land Rover started to sink and the water began rushing in. My mother screamed and held the baby tightly in her arms. Then my father leaned out of the window and shouted to the workers in the back to get out and push: ‘Sukuma! Sukuma!’, meaning ‘Push! Push!’

The workers shouted back ‘Bwana (Sir), we are pushing!’ He was furious when he looked into his rear view mirror only to see them standing and pushing from their position inside the Land Rover. ‘How can you be pushing, since you're in the Land Rover? Get out and push immediately!’ And he added, ‘Ng’ombe!’, which is a term, literally meaning ‘cow’, used in Swahili to express anger at stupidity. They immediately jumped into waist-deep water, yelling to each other, and tried unsuccessfully to push. To add to the chaos, at this point my mother decided it was time to abandon ship: ‘Tell the workers to come and get the kids, I’m getting out!’ But she could not open the door because of the pressure from the rising water on it. Almost panicking, she opened the window and passed my brother to the outstretched arms of the workers. Poor thing, he started to cry, obviously aware of the danger. My mother shouted ‘Lift him higher! Go to the rock there high on the bank!’ It was my turn next: ‘Now you.’ I climbed over my mother to the window and into the strong arms of the workers. She gave me instructions: ‘When you get to the rock, hold your brother in your arms. Hold him tight!’

The workers, carrying us, made their way through the swirling waters around them. When we reached the rock by the shore I sat there with my brother in my arms. I was so happy to finally be allowed to hold him. By now it was dark, but in the headlights of the Land Rover I could see him smiling up at me, and I smiled at him and whispered ‘My sweet little brother, you are safe in my arms.’ When I spoke to my brother it was in English, the language we would always use with each other as we grew up. Very rarely did we exchange a word in Greek. With our mother we would speak in Greek, English and Swahili; with my father in English and Swahili. Although he understood Greek he never spoke it. It was very amusing to hear conversations between my grandmother and my father. It was an explosive mix, him speaking English and Swahili, and my grandmother Greek, French and Swahili, all jumbled up!

It was raining heavily now. The workers helped my mother to climb out of the window. She barely made it to our rock and safely through those dangerously rising waters. I was overjoyed to make out the silhouette of my bike, still on the roof of the Land Rover, tied amongst the trunks. I really did not want to lose my friend.

She sat near us and stretched out her arms to take the baby from me. I heard loud voices as everyone prepared for a last effort get the vehicle across. The engine roared and then choked to a silence: it had flooded. All of a sudden another convoy turned up on the far side of the river. There were several vehicles and their headlights threw light onto the whole scene. They shouted and my father answered. Rescuers had arrived. They immediately pulled chains from their vehicles and attached them to the Land Rover that was stranded in the river. My mother left us to go and help, so I had the chance to hold my little brother once again. She asked a guard to sit with us. We could hear the voices of wild animals all around us in the night, but we were assured that there was no danger because the commotion would keep them away.

The rain stopped and my brother started to cry; I rocked him in my arms just as I had seen my mother do when he needed calming. Before long I heard cheers as the Land Rover was finally pulled across the river and reached the shore. Already the volume of water was starting to decrease. My mother asked the guard to take us to the second Land Rover. We boarded quickly as it was already attached to one of the vehicles on the opposite shore; behind us was the truck. There was a jolt and we began to be hauled across the river while the wheels knocked noisily against rocks on the riverbed. The experienced driver held the steering wheel firmly, shouting in Swahili to the others on the opposite bank. Finally the truck was dragged across the river and we were safely on the other side. We were all drenched and exhausted. It was decided we would camp for the night and begin the final leg of the safari to Swaziland at dawn. The four of us slept together in one tent after we had had something to eat. I fell asleep to the sound of rushing water and the cries of wild animals.