West River Resilience Project

Reed Bryant

Kayla Hatcher

Stefan Poost

WEST RIVER RESILIENCE PROJECT

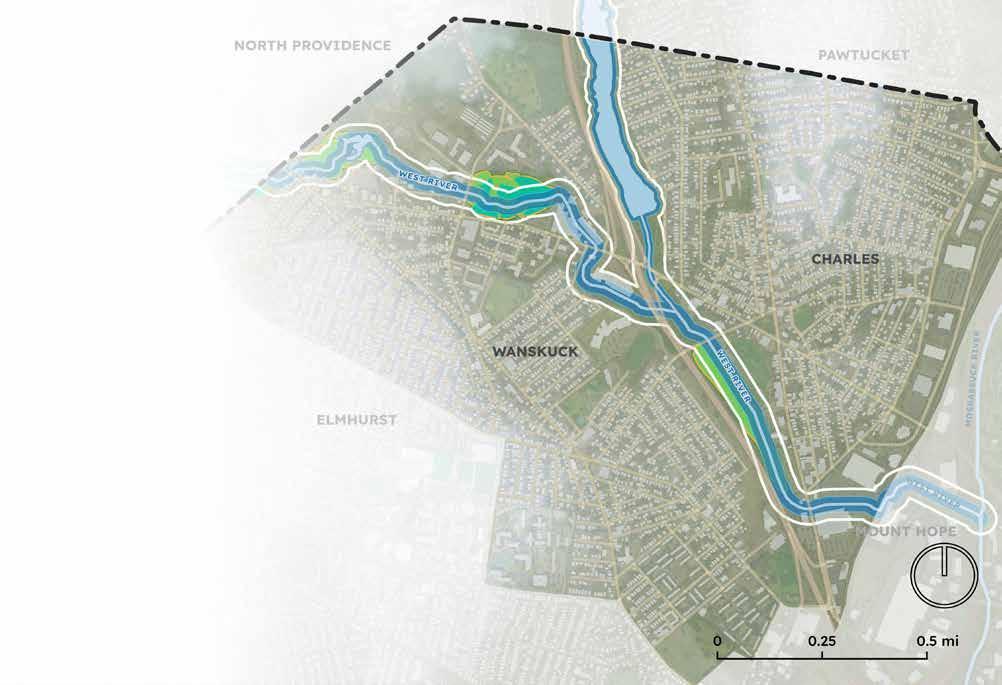

The West River Resilience Project is a project for the Providence Department of Planning and Development, in collaboration with The Conway School of Landscape Design. The project seeks to improve ecological and social conditions of the West River in the North End of Providence, RI, including the neighborhoods of Charles and Wanskuck.

PROJECT CONTEXT

A River Neglected

As legacy infrastructure strains to accommodate a changing climate, piecemeal responses to a string of recent floods along the West River precipitated a rethinking of how to make the neighborhood more climate resilient.

Flooding

In the early 2020's, the West River in the North End experienced repetitive, damaging flash flood events resulting in loss of property and businesses and disruption to road networks. Several of these events were later declared federal disasters according to FEMA guidelines. Vulnerable areas where repeated damage was sustained include low-lying commercial zones such as Branch Avenue Plaza and the big box stores located near the Charles Street bridge. In response to these floods, various city agencies have explored options to mitigate flooding, while the Planning Department seeks to coordinate a long-term proactive response.

-> Flooding

March 2010

A 100-year storm dumped 16 inches of rain across Providence, costing $200 million with millions of gallons of raw sewage overflows.

River Access / Health

The West River's role in the Industrial Revolution resulted in damming and channelization of the waterway's natural flow. Subsquent urbanization in the 20th century further constrained the river, with the development of commercial infrastructure adjacent to the river. Today, the West River remains primarily fenced off and/ or contained in concrete channels, diminishing habitat value and water quality.

Neighborhood Connectivity

While the West River runs through the center of the North End, infrastructural barriers prevent easy connections through this corridor and across neighborhoods.

September 5, 2022

A Labor Day storm dumped nearly 5 inches of rain on Providence, closing roads near the West River and stranding vehicles.

-> Neighborhood Connectivity

The Branch Avenue underpass provides one of two crossings of Route 146. The pedestrian experience is complicated by multiple intersections, traffic, and narrow, unlit sidewalks.

-> Neighborhood Connectivity

The Hawkins Street Bridge provides one of two crossings of Route 146. Rebuilt in 2020, the bridge provides ample space for pedestrains and cars as well as views of the river.

WEST RIVER

-> River Access

Chain-link fences and concrete channels along the river next to the Walmart parking lot hinder public access to the river. Frequent dumping of refuse near the river creates an unwelcoming environment.

September 11, 2023

Inches of rain inundated Branch Avenue Plaza, closing businesses for months. More than two dozen people rescued from floodwaters.

December 17-19, 2023

A powerful regional storm closed Branch Ave. and Charles St. The city of Providence sustained $3 million in damages.

January 10-13, 2024

Heavy rain and snowmelt closed Branch Ave. and Charles St, leaving cars stranded and water cresting into Branch Ave. buildings.

March 23, 2024

Spring storms closed roads along the West River and left cars stranded along Branch Ave. and Charles St.

CHARLES

WANSKUCK

GOALS & CLIENTS

A River Restored: A Multifunctional Plan

Can a proactive flood response be combined with river restoration to create new relationships between the community and its natural assets? The West River Resilience Project envisions interventions around the West River in the North End that seek to improve:

1. Climate and Flood Resiliency

The industrial history of the area has resulted in a channelized and polluted river. The increased frequency of heavy rain events has resulted in regular flooding of the river, impacting infrastructure along its banks. The client seeks to improve the resiliency of the neighborhoods through decreasing infrastructural and community health impacts of the river flooding.

2. Water Quality / Ecological Health

The client seeks to improve the health of the river's waters and riparian (land adjacent to water body) zones, and improve its function as a wildlife corridor through an urban envrionment.

3. Public Recreation & River Access

Neighborhoods adjacent to the West River have limited access to the river as well as outdoor recreation spaces for the area's diverse demographic groups. The client seeks to establish public recreation along the river and improve the relationship of residents to the river through access and education.

4. Charles & Wanskuck Connectivity

Due to topography and infrastructural barriers, a limited number of connections exist between Charles and Wanskuck and from these neighborhoods to the city at large. The client seeks to improve connectivity between the neighborhoods and to the rest of the city.

Clients

The client for this project is the City of Providence Department of Planning and Development. Other stakeholders include:

The River and its Community

The residents of Charles and Wanskuck Neighborhoods, as well as the West River and the ecological communities it supports, are recognized as the critical project stakeholders whom the project ultimately serves.

Can landscape-based solutions proactively improve flood resilience as well as restore a river ecosystem for the benefit of the community?

City Departments / Wards

• Public Works

• Parks

• Sustainability

• Emergency Management Agency

• Ward 4 - Councilor Roias

State Departments

• Environmental Management

• Transportation

• Energy

Businesses and Organizations

Community organizations and business associations who have provided important support for the project, including:

• Davinci Center

• North End Business Association

• North End Neighborhood Association

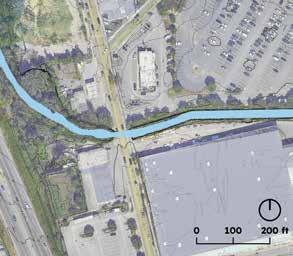

West River is contained in armored banks between the Home Depot and Walmart parking lots, with concrete walls, industrial and residential waste, and aggressive species.

West River is channelized between Prete-Metcalf Park and western wetlands, with a berm separating the river from the wetlands, and informal trails on either side.

EXISTING CONDITIONS

Neighborhood Overview

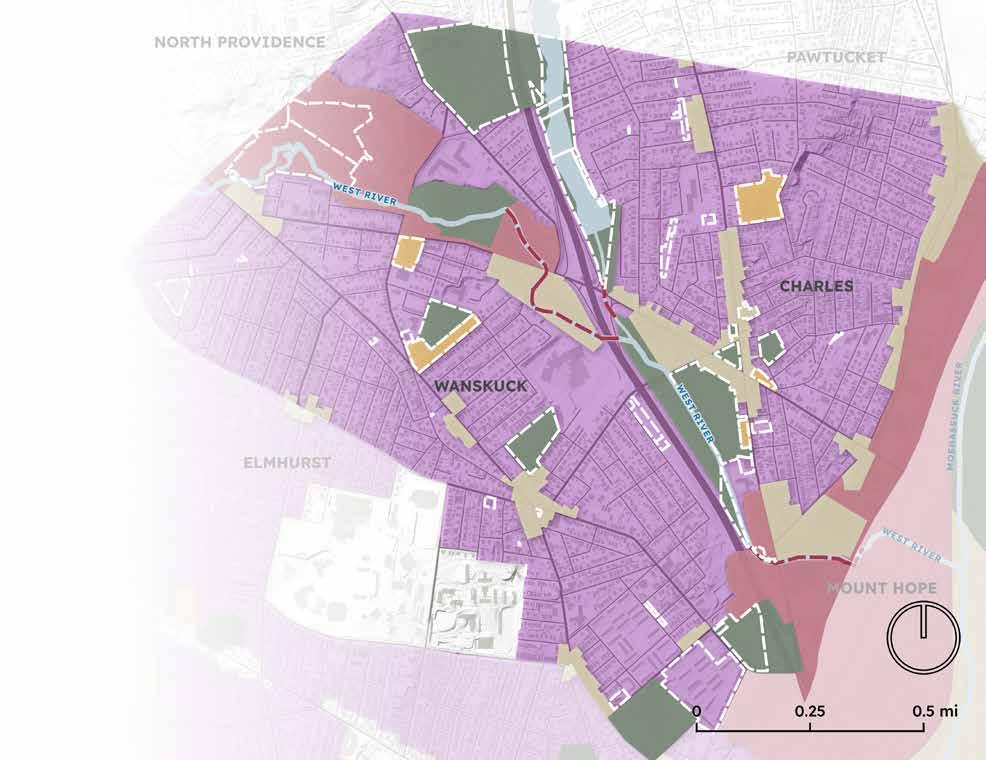

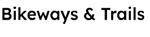

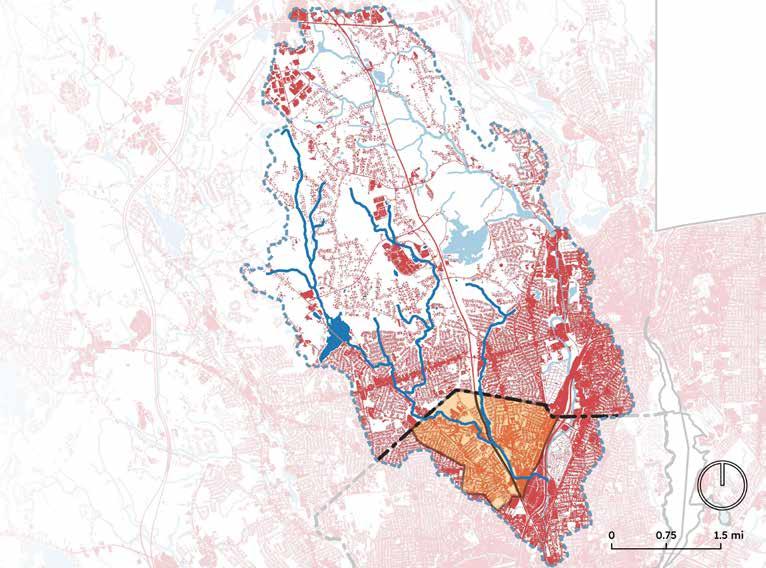

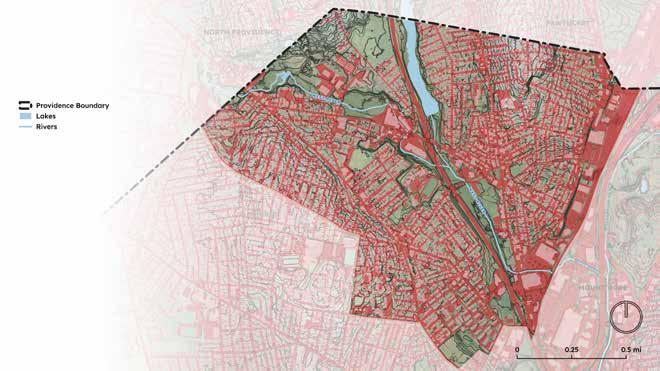

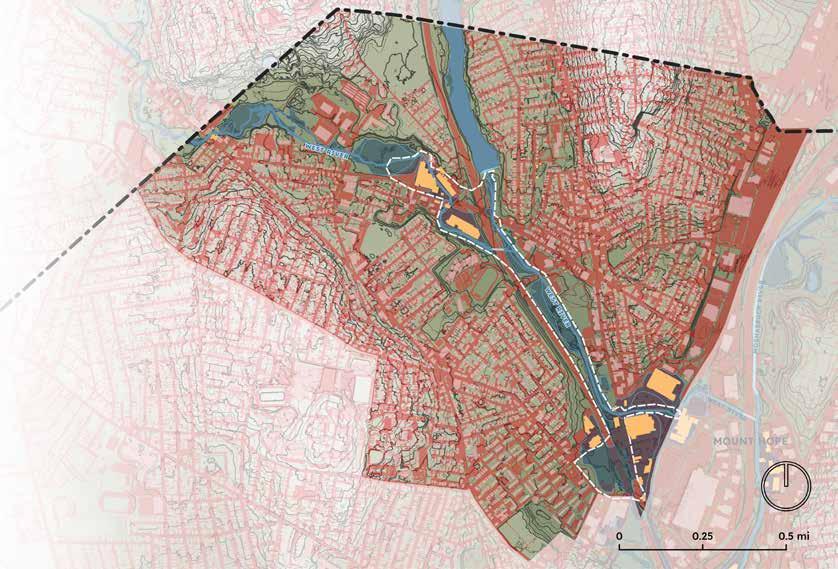

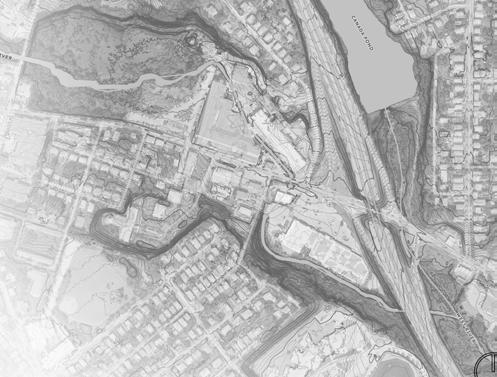

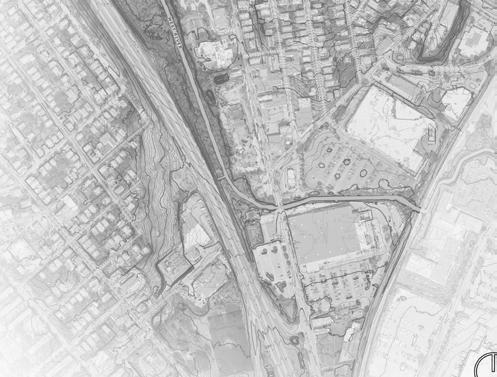

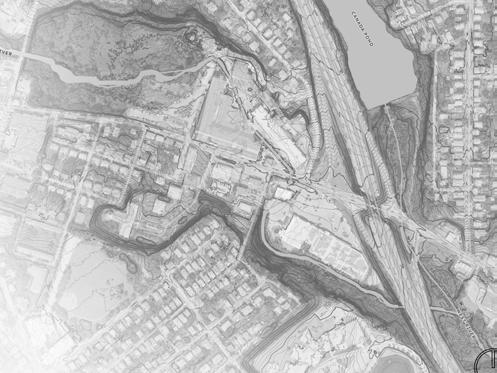

The North End, consisting of the neighborhoods of Wanskuck to the west and Charles to the east, is bissected by the West River flowing northwest to southeast, as well as Rte. 146, a six lane highway here. Branch Ave. underpass and Hawkins St. Bridge connect the neighborhoods, while Charles St. is an important commercial street passing through Charles along the river from Hawkins Square, a neighborhood center, south over the river near Home Depot. The Northeast Corridor rail line bounds the area to the east.

Upper Zone

A low-lying commercial area.

The West River runs through the Wanskuck Mill then under and around Branch Ave. Plaza, before passing under Rte. 146.

Middle Zone

The West River emerges into a more naturally-vegetated area. Wetlands lie past Hawkins St. Bridge on the west bank, while ball fields lead up to Hopkins Square on the east.

Lower Zone

The River bears east, passing under Charles St. and entering a concrete channel between Home Depot and Walmart before exiting the neighborhood under the rail road.

INDIGENOUS / COLONIAL HISTORY

Narragansett Stewardship

The North End of Providence, including the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods, lies within the ancestral homeland of the Narragansett people, part of the larger Algonquian-speaking cultural group. Prior to European colonization, this area was shaped by complex Indigenous land use practices including seasonal movement between coastal and inland sites, planting of the Three Sisters (corn, beans, and squash), and management of woodlands through controlled burns (Cronon, Changes in the Land) The West River and surrounding wetlands were used for fishing, hunting, and transportation, forming a lifeway deeply connected to water and land. Neighboring and allied tribes such as the Niantic, Wampanoag, and Pokanoket also moved through and interacted with the area (Pesch et. al, Imprint of the Past: Ecological History of Greenwich Bay, Rhode Island).

Early Contact with Europeans

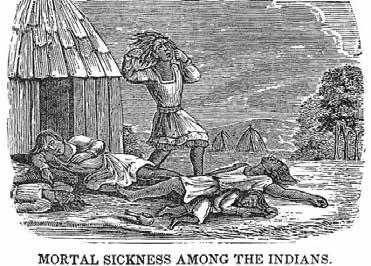

Indigenous tribes in the northeast were trading with European fishermen and merchants by the early 16th century, unintentionally coming into contact with old-world diseases they had little resistance to. A deadly epidemic from 1616 to 19 devestated Indigenous populations in the region, depopulating entire villages. English colonists founded Plymouth Colony on top of the ruins of Patuxet village. A governor of the colony remarked:

“...for the natives, they are nearly all dead of the smallpox, so the land is even cleared for us, and we find the ground neither overrun nor greatly encumbered with woods, making it easier to settle.”

William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

Wars and Displacement

In the 18th century, the fur trade with Europeans fueled territorial wars between Indigenous tribes, with Dutch, French, and English colonists backing different groups in a series of proxy conflicts (Richter, Facing East from Indian Country). Wars raging in the west and swelling European settlement along the coast severely pressured the remaining Indigenous people in the region. Mounting tensions between the English colonists and an alliance of Indigenous tribes led by the Wampanoag culminated in a deadly series of reciprocal raids against civilian populations known as King Phillip's war. The Narragansett tried to maintain neutrality, but were accused of harboring combatants by the English and attacked. By the end of the war, much of the Narragansett population had been killed, enslaved, or scattered, ending their sovereignity over the land that is now known as the North End of Providence (James D. Drake, King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675–1676).

Enduring Narragansett Presence

Despite tragic historical circumstances, the Narragansett Tribe remains active today, with a state-recognized reservation in Charlestown, RI. While no tribal offices or reservations are currently headquartered in the North End, tribal members in nearby communities continue to advocate for land rights, environmental justice, and the protection of sacred sites and cultural heritage across their ancestral territories.

1520s-40s

Indigenous people and Europeans begin trade

1616-19

Epidemic sweeps through coastal indigenous tribes

1609

Territorial wars break out in the Great Lakes region

1675-78

King Phillip's War and Narragansett displacement

1792

State of RI abolishes the position of Sachem and installs a five-man council

1889-1901

Organized Narragansett attempts to pursue land claims

1880-84

State of RI abolishes Narragansett tribal authority, reservation area sold off

1934

Narragansett Tribe of Indians incorporated with traditional offices

1975-78

Narragansett Tribe files a land claim against the state and landowners, settling for 1,800 acres out of court

1983

Narragansett Tribe of Indians receives federal recognition

2020

Narragansett Trail Restoration Project begins

19th century depiction of the 1616-19 epidemic. Image from Historic Ipswich.

John Guy’s party meets a group of Beothuk at Bull Arm, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland.

Matthäus Merian, Dreyzehender Theil Americae, 1628

Photo taken at the Narragansett tribe's Pow-Wow, an annual event where traditional dress and dance are celebrated.

POST-COLONIAL HISTORY

Industrialization

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the area remained largely rural and semiwild, with wetlands and rocky uplands limiting settlement and keeping it outside the urban core of Providence. During the 19th century, industrial development surged as textile mills were constructed along the West River, drawing German, Scottish, and Italian immigrants to the area. The river became heavily industrialized with dams and buildings on its banks, powering mills and used for waste disposal, while adjacent wetlands were increasingly filled in for development. Channelization of the West River altered its natural course, eliminating habitat and disconnecting it from its floodplain. This development erased traditional land uses and severed Indigenous access to the river and surrounding forests.

Urbanization

Infrastructure improvements and annexation gradually incorporated the North End into the expanding city of Providence. The mid-20th century brought significant disruption: highway construction, discriminatory lending policies, and the effects of deindustrialization fragmented neighborhoods, reduced property values, and led to disinvestment. As traditional industrial jobs disappeared and demographics shifted, local community institutions began to organize in response to economic and social challenges. From 2000 to the present, the North End has existed in a post-industrial context, facing persistent inequalities but also opportunities for reinvestment, environmental restoration, and community-driven visions.

1636

Roger Williams founds Providence on land granted by the Narragansett

17th-18th centuries

European settlement expands northward, what is now the North End was used for farmland and pasture

Late 18th century

Rivers used to power small sawmills and gristmills

1832

Heaton-Cowing mill opened along the West River to produce textiles

1830s-1850s

European immigrants arrive to work in mills, neighborhoods form

1872

The North End is annexed to Providence

1862

Wanskuck company is established, acquires other mills

1957

Wanskuck mill closes

1950s-60s

West River channelized and wetlands filled in, I-95 is constructed

1970s-80s

Job loss, flight to suburbs

1970s-present

Immigrants from around the world move in

2019

Providence Climate Justice Plan identifies the North End as a environmental justice focus area

Roger Williams meeting Narragansetts. Photo by James Charles Armytage.

The Wanskuck Mill circa 1920, from the John Hutchins Cady Research Scapbooks Collection, Providence Public Library

Family-owned businesses like Shami's Wraps give new life to old buildings in Charles.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Stakeholder Meetings

On 25 April 2025, a stakeholders meeting provided insight into the current relationship between numerous community organizations, city staff, the river, and prior flooding events. On 5 May 2025, the Conway Team presented about the West River Resilience Project at a Ward meeting for Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods, with 36 participants hosted at the DaVinci Center. Printed surveys were shared at this time, and a QR code for the digital survey was shared for future input. Members of the local mosque, business owners, and other community members also shared insight through informal conversations throughout April and May.

Conversations with residents highlighted a love for the diversity of their community. They shared concerns over safety navigating the streets both during the day due to high traffic, narrow sidewalks, and a lack of shade and seating, and in the evening due to minimal lighting. Youth expressed a desire for recreational spaces (e.g., basketball courts).

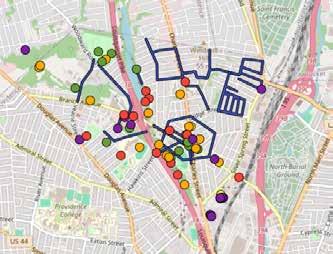

Community Survey

An interactive map survey (created using Partimap.eu) was released in English on 5 May 2025, and in Arabic and Spanish on 23 May 2025. The 2025 Charles and Wanskuck Community Survey, hereafter identified as the Conway Survey, results highlighted the Branch Avenue Plaza, Walmart, and Home Depot as priority shopping areas. These businesses were impacted by the 2023 and 2024 flood events and are within the FEMA floodplains (see page 17). One business owner expressed a lack of options for produce and a concern about the high prices within local markets as compared to the chain stores. The loss of essential resources due to repeated flooding without incentive for further markets within the neighborhood could result in increased food insecurity.

Areas highlighted as favorite spots were dominant around existing parks, but these same areas overlapped with places individuals avoid yet desire to access. While some desired spots were along the river corridor, reasons survey responds gave for avoiding the these desired spots related to waste management and large numbers of unhoused individuals residing along the river. For green spaces to be more appealing to residents, cues to care, regular use, and clean-up events can decrease waste accumulation in parks. Affordable housing will need to be addressed at the policy level. Residents also expressed concerns about high traffic volumes around central intersections were also expressed.

Many of the concerns expressed in the survey, such as affordable housing, safe streets, and safe parks, align with assessment data collected from GIS sources and on-site observation.

Community Needs Assessment

The DaVinci Center conducted the North End Community Needs Assessment in November 2024. This assessment highlighted Charles and Wanskuck as culturally rich, with strong social networks and multigenerational households, and a community desire to assist in improving the neighborhood. Cost of living, food and health insecurities, isolation amongst seniors, a lack of youth engagement opportunities, language barriers, a lack of cultural celebrations, and uneven dispersal of community services were voiced as priority concerns.

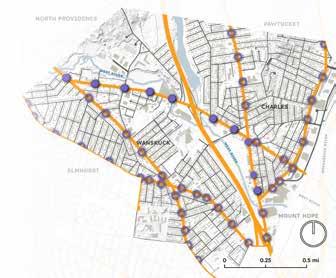

Bike & Walking Paths

DEMOGRAPHICS

During the 19th century, the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods were home to immigrant communities working for the Silver Spring Bleaching and Dyeing Company. While these immigrants came from Ireland, Scotland, Germany, England, and Italy, Italians remained the dominant demographic until the mid-2000s. Over the past 20 years, these neighborhoods have seen significant diversification as refugees and asylum seekers from Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America have arrived in Providence. From October 2023 to October 2024, 396 refugees from 19 countries arrived in Providence (Stacker, 2024). This has led to culturally vibrant communities. The Conway Survey(2025), along with the DaVinci Center community needs assessment (2024), highlighted the diversity of the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods as a defining asset of their community.

Diverse Stories

23.4% of Charles and 31.4% of Wanskuck residents are foreign-born, and many are refugees and asylum seekers (Census Reporter). 51.4% of Charles and 58% of Wanskuck residents speak English as a second language, with Spanish being dominant, followed by Indo-European languages, Asian and Pacific Island, and others (Census.gov). Dorcas International, the Catholic Diocese of Providence, and Refugee Dream Center are established as official refugee resettlement agencies in Rhode Island, providing services such as resettlement and placement, cultural transition, language education, job development, and social services (DHS.RI). The capacity of these organizations to provide resettlement services has been significantly impacted by the 24 January 2025 Stop Work order for refugee resettlement organizations and subsequent federal funding cuts (Diiri.org). This results in heightened risk of housing and work insecurity, and decreased health for refugee communities within the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods.

Vulnerable Residents

12.9% of the population of Providence is food insecure (just below the national average of 14.3% as of 2023) (Feeding America). 8.5% of households are without a vehicle and lack access to a supermarket, qualifying the North End as a USDA-identified Food Desert (USDA). The prevalence of poverty (22% in Charles and 38% in Wanskuck) and a lack of affordable housing have led to an increased population of unhoused individuals in Providence. Many unhoused individuals are residing along the West River and near Canada Pond.

EJ, ETCE & Justice 40

The Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods are identified by the Equitable Transportation Community Explorer (ETCE) as communities with a cumulative burden of underinvestment in transit, climate and disaster risk, environmental injustice, and health and social vulnerabilities (RI Social Equity Platform). These neighborhoods are also identified as Justice 40 communities by the federal government. A Justice 40 designation means that "40% of the federal climate, clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing, and other investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution" (Biden White House). Justice 40, along with environmental justice (EJ) initiatives, was dismantled in January of 2025 under the Trump administration.

U.S. Resettlement

While 2017-2020 saw record lows for refugee resettlement in the U.S., in 2024, a record high of 100,034 refugees were resettled in the U.S. In September 2024, a goal was set of admitting up to 125,000 refugees in 2025 (state.gov). On 27 January 2025, an executive order suspended the Refugee Admissions Program (Visa Verge). This, in combination with recent ICE raids, has left a feeling of unease amongst refugee and migrant communities. This underscores the importance of safety for immigrant communities at community engagement events and in green spaces.

"WE ARE VERY DIVERSE. RECENTLY, THERE SEEMS TO BE MORE INTEREST IN COMMUNITY. RESIDENTS SEEM

Community Metrics

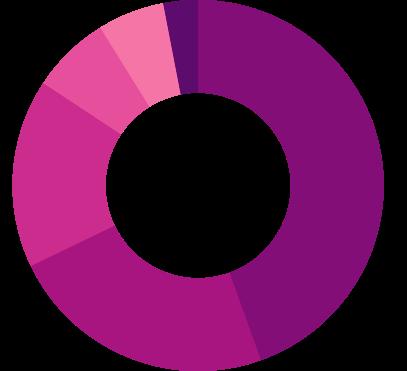

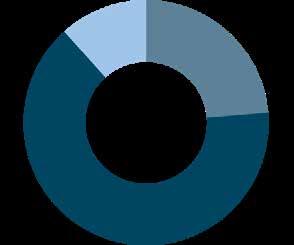

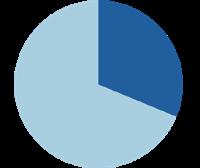

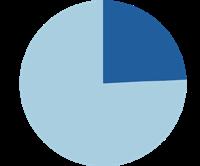

Top: Ethnic and age make-up of North End Bottom: Vulnerable groups below poverty line (censusreporter.org)

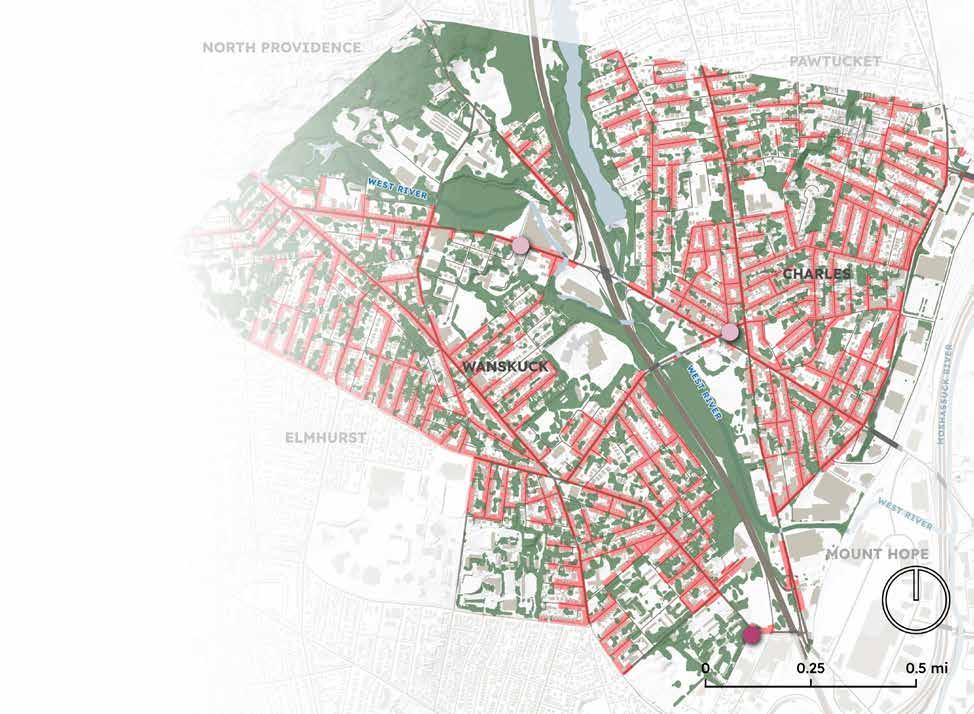

RIVER ACCESS

Physical & Social Barriers

Walls and dams, remnants of industrial era factories, channelized West River and Canada Pond. The river has since been fenced off in parts to seperate residential access. It was also been piped underground and further channelized to make way for highways and roads . In Charles and Wanskuck, approximately 40% of the river is blocked from human access, with additional restrictions as it passes through private property and industrial zones. Prete-Metcalf Park and Canada Pond have a high accumulation of waste (e.g., tires, mattresses, grocery carts, appliances, and trash bags), decreasing community interaction with the space due to smell and perceived safety. The undeveloped, hidden, and uninhabited wetlands to the west and northwest of Prete-Metcalf Park and just south of the Canada Pond dam have become a dwelling area for unhoused individuals, further adding to the perceived lack of safety in these areas expressed by community members and PEMA staff.

State Highway 146 bisects the West River and Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods, decreasing the ease of access of residents to resources. I-95 interstate, running along the eastern edge of Charles along the railroad tracks, hinders pedestrian flow between Charles and Mount Hope. The Hawkins Street overpass allows pedestrian movement between the neighborhoods, but crossing from Charles into Wanskuck takes individuals farther from the northern portion of the West River. The Branch Avenue underpass is narrow and puts pedestrians near vehicles exiting and entering the highway, and leads individuals into areas where the river is restricted by a fence or channelized through private property.

Private Land

Charles and Wanskuck are primarily residential with a local commercial center around Hawkins Square and scattered open space. While the river flowing through open space is open to the public, accessibility is limited due to a dense understory in wooded areas, a lack of formal paths, and perception by some residents of unsafe conditions. Of the 41 parcels adjacent to or intersecting the West River and Canada Pond, only 8 are city or state owned, creating barriers to access for future projects along the river.

While the river has unchannelized sections in both neighborhoods, infrastructure and the disjointed pattern of open space, ownership, and river access inhibit the ability for pedestrians to connect to multiple open space areas without interacting with main thoroughfares with high-volume traffic or crossing into private property.

"THE DEBRIS AROUND THE RIVERS IS UNPLEASANT AND MAKES THE RIVERS MISERABLE."

Two fences and a concrete wall blocks access to river.

TRAFFIC / TRANSIT

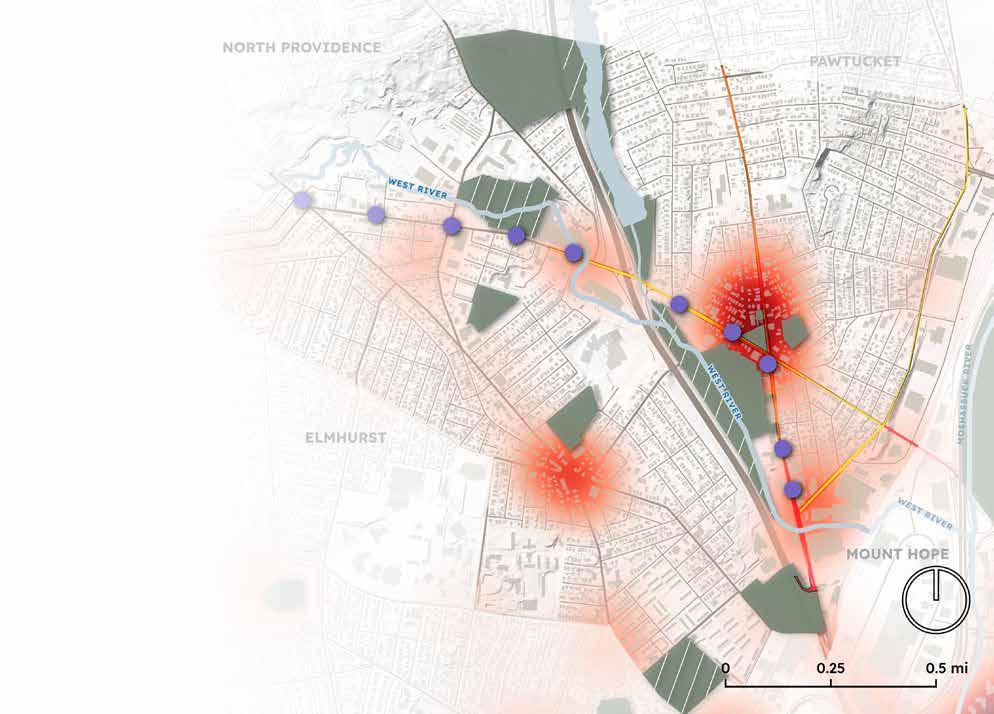

Commerce hubs at Hawkens Square, Branch Avenue. Plaza, and the corner of Silver Spring Street and Charles, overlap with streets of high traffic volume. The confluence of high traffic, narrow sidewalks, and a hidden river results in a lack of safety and designated recreational spaces on sidewalks or at the edges of green spaces (e.g., rivers). The RIPTA bus system allows for consistent public transit, but community members have expressed concerns about safety at bus stops and the reliability of the bus schedule.

99/100 Traffic Fatality Rate

Major local thoroughfares intersecting at pedestrian hubs, such as Hawkens Square, with no designated bike lanes, results in Charles having a traffic fatality rating higher than 99% of census tracts in Rhode Island (NHTSA FARS, 207-2021). As the North End Business Association (NEBA) works to establish Hawkens Square and the crossing streets of Charles and Branch Avenue as the North End's local business district, interventions are needed to improve walkability, bikeability, pedestrian access to local businesses, and green space.

RIPTA Buses

"CONSTRUCTION IS ALMOST ALWAYS ONGOING - WHICH BLOCKS MANY

The RIPTA bus system, running every 45 minutes from 5:30 am to 11:30 pm, is the primary public transit for the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods. As 15.9% of households in Charles and 26.2% of households in Wanskuck are without vehicles, Charles rates at 92/100 for transit cost burden (USDOT ETC, 2016-2020). 24% of houshold income or residents is spent on transit, reliability of the bus system is necessary for community transit (USDOT ETC, 2023).

Through the Conway Survey, residents expressed concern about the reliability of the bus schedule due to construction and traffic delays. Other residents reported that seasonal temperatures prevent the elderly from using the bus due to the existing lack of environmentavl protection at bus stops and seating on the streets for the commute to the bus stops. Many bus stops are also located in high crime areas, eliciting concerns for safety.

No bus routes pass through residential streets. Of the existing 10 bus stops near the West River, three lead to designated park space along the river. These three stops are within a 5-minute walk of Prete-Metcalf park along Hawkins Street or Charles Street The entrance to Canada Pond is marked by a sign and a dirt path leading to the dam, but the entrance is at the intersection of Branch Avenue and Route 146 and the view from the road is blocked by vegetation and trash piles, making it an undeseriable entrance for pedestrian use. The open spaces just west of the Wanskuck Mill and north of Hawkins Street. along the river have nearby bus stops, but no amenities. While buses increase community access to the river for vulnerable community members, safety and environmental factors impacting health decrease use of these resources.

PEDESTRIAN MOVEMENT

Walkability

The Charles neighborhood has an EPA (2021) walkability score of 19%, while Wanskuck has a walkability score of 91%. EPA walkability scores are calculated by asessing population density, diversity of land uses, and proximity to transit (EPA.gov, 2024). Sidewalks are narrow, uneven, and along major roads; they also lack seating (RI Social Equity Platform). 68% of sidewalks within Charles and Wanskuck do not have tree canopy cover. Unshaded pavement can reach 60°F hotter than shaded pavement, further threatening vulnerable communities, e.g., the elderly, youth, and those with respiratory and cardiovascular conditions (CSDA).

11% of the streets & sidewalks have a slope over 5%, requiring moderate to extensive grading to make wheelchair accessible pathways. These areas are dominant within residential portions of the neighborhood, further isolating vulnerable communities from access to public transit (located at the bottom of steep streets along major roads) and public resources such as the West River.

Air quality is also a concern, with 13% of adults in Charles and 15% in Wanskuck experiencing asthma (RI Social Equity Platform). A combination of poor air quality, a lack of green space, and environments built of concrete and asphalt increases asthma risks by 27% in adults and 35% in children (Yu and Melen).

The DaVinci Center's community needs assessment highlighted isolation of the elderly and a lack of engagement activities for youth. As these communities rely heavily on the walkability of a city, decreasing concrete and asphalt, increasing greenspace, adding seating alongside roads, and slowing traffic can help to decrease the health and isolation impacts of the urban environment.

Bikes, Scooters & Trails

Three bike and scooter ride share programs exist within the city: Veo (Veo bikes were unavailable during surveying), Bird, and Spin.

One bike share hub is located at the southern tip of the Wanskuck neighborhood. Transit on a bike or scooter via roadways is dangerous due to a lack of marked bike lanes. There is a high density of vehicle-to-pedestrian accidents throughout the neighborhoods (NHTSA FARS, 207-2021). Bikeways and trails exist just to the north and a few miles south of the neighborhoods, with no existing thoroughfare. Sidewalks are narrow and inconsistent, and not intended for bike or scooter us.

TERRAIN / SOILS

Geologic Context

The ground beneath Charles and Wanskuck is made up of very old layers of rock, over 300 million years old, known as the Rhode Island Formation. Rocks like slate, sandstone, and conglomerates first formed from mud, sand, and gravel in ancient river deltas, and were later changed by intense heat and pressure deep underground. Movements in the Earth’s crust also bent and cracked these rocks. Much of this bedrock doesn’t let water soak through, especially in areas with shale, which may lead to more water running off the surface when the soil is thin. On top of the bedrock, glaciers that moved through the area about 15,000 years ago left behind a mix of sand and gravel. These glacial materials created a varied landscape, with dry, well-drained hills made of coarse soils and wetter low areas where finer sediments settled near rivers. This mix of soils supports a range of plant habitats from dry oak and pine forests on the uplands to swamps, to wet meadows and floodplain forests near the river. Today, much of the original soils in Charles and Wanskuck have been disturbed or removed due to urban development.

Terrain

The Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods form a topographically varied area in the North End of Providence. While Charles is predominantly flat and urban-suburban in character—supporting residential and commercial development—it also features a prominent hill in its northern section, with slopes ranging from approximately 8% to 15%. Wanskuck has a similarly varied terrain, marked by a series of gentle hills, wooded pockets, and industrial-era mill sites along the river. Elevation in the North End spans from a high point of about 200 feet above sea level on the hill to a low of around 20 feet in the floodplain of the West River, which runs from the north of Wanskuck and along the western edge of the Charles neighborhood. The river occupies a low-lying corridor that collects runoff from both adjacent slopes and upstream communities. Despite being channelized, the West River continues to flood low points in its topographical floodplain with increasing frequency, and steep slopes along the channel make access difficult.

Ecological Implications of Terrain and Soils

The varied terrain of the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods historically produced a range of habitats, shaped by differences in elevation, soil type, and moisture availability. Low-lying areas along the river corridor form wetlands and floodplain environments with alluvial soils that can support moisture-loving plant species, amphibians, and riparian wildlife. In contrast, the steeper slopes and higher elevations— particularly in northern Charles and parts of Wanskuck—have welldrained upland sandy loams that historically supported dry oak-pine forests and other upland plant communities. Areas shaped by glacial outwash, with sandy or gravelly soils, provide yet another distinct ecological niche, favoring drought-tolerant vegetation. However, widespread development and land alteration have resulted in extensive areas of urban complex soils, disturbed soils composed of mixed fill, compacted layers, and construction debris. These altered soils often support opportunistic and disturbance-tolerant plant communities, including invasive species. These plants are not always more competitive than natives, but they are often the first to thrive in poor or compacted soils.

Low Point: 20'

High Point: 180'

River Corridor Hill

USDA NRCS Soils, NOAA lidar, RIDEM Lakes and Ponds 24k, RIDEM Rivers and Streams 24k

ECOLOGICAL HABITATS

Urban Land

On developed urban land in Charles and Wanskuck, habitat exists in highly modified and fragmented forms but still provides some ecological functions. Paved surfaces such as parking lots, roads, sidewalks, and rooftops dominate much of the landscape, limiting habitat connectivity and increasing runoff. Street trees and residential yards offer limited canopy cover, floral resources, and microhabitats for urban-adapted species.

Ruderal Forests

Existing ruderal (disturbed) forests in Charles and Wanskuck, particularly the isolated upland patches on the hill in Charles and within Wanskuck Park, are ecologically altered woodlands characterized by edge habitat conditions. These forests are often dominated by early-successional trees such as black cherry, tree-of-heaven, Norway maple, and black locust, with understories of Japanese knotweed, bittersweet, multiflora rose, and poison ivy. Despite not being large enough to support many species, these patches do support a range of urban-adapted wildlife.

Trees

Norway maple (Acer platanoides) is a non-native tree from Europe, commonly planted in urban areas for its fast growth and dense shade. It spreads easily in disturbed forests, forming dense stands and releasing allelopathic chemicals that suppress native plants. It is the most common tree in forests adjacent to the West River.

Oaks (Quercus spp.) are dominant canopy trees that produce an abundance of nuts in the fall and support a multitude of wildlife. Oak trees need sun to thrive, struggling in dense, closed canopy forests. Multiple native oak species grow in the north end: white oak, black oak, and red oak.

Isolated upland forest patches

Ruderal Wetlands

Ruderal wetlands in Charles and Wanskuck—often found along the edges of the West River, near Canada Pond, and in low-lying former industrial parcels—are degraded but ecologically active habitats. These wetlands are dominated by invasive or disturbance-tolerant species with occasional native species persisting in some places. These ruderal wetlands are ecologically important for flood storage, water filtration, and providing habitat in an urban matrix, although their biodiversity is limited compared to more intact wetland systems.

Ruderal Grasslands

Shrubs

Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) is an invasive shrub from East Asia, introduced for erosion control and hedgerows. It forms dense, thorny thickets that crowd out native plants and hinder human access. In the north end, multiflora rose is found in the understory of every ruderal forest environment.

American black elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) is a native shrub that grows along forest edges and wetlands. It produces white flowers and dark berries that support wildlife. In the North End, it appears alongside the West River, where it helps stabilize soil and supports native ecosystems.

Herbaceous Plants

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is an aggressive invasive plant from East Asia, often found along roadsides, rivers, and disturbed sites. It spreads rapidly through rhizomes, forming dense stands that crowd out native vegetation. It grows abundantly alongside the forest edge in Prete-Metcalf Park and the West River.

Eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) is a native broad-leaved perennial that thrives in wet, shady areas such as swamps and streambanks. In the North End, it emerges in low, marshy areas near the West River, where it improves soil structure and provides cover for wildlife.

Vines

Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) is a fast-growing vine introduced from Asia, now common in forests and urban edges. It climbs and girdles trees, smothering canopies and contributing to tree fall. In the north end, oriental bittersweet is found ubiquitously along forest edges.

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is a native vine that thrives in disturbed areas, including woodlands and urban edges. It produces an oily resin (urushiol) that causes skin irritation, restricting human connectivity to areas where it forms a dense groundcover. In the North End, poison ivy grows prolifically inside forests alongside the West River.

Ruderal grasslands in Charles and Wanskuck appear in two contrasting forms, each with distinct ecological implications. The most widespread are turfgrass lawns, which dominate schoolyards, parks, roadside verges, and residential yards. These managed grasslands, often composed of a few non-native species, excludes the diverse plant and insect communities typically found in more natural grasslands.

In contrast, unmown and early-successional grasslands found in abandoned lots, vacant parcels, and beneath power lines support a more diverse and ecologically functional set of species. While still dominated by non-natives, these sites provide valuable habitat for pollinators and offer foraging and cover for birds.

"Rock Pigeon" by lotsofish "Super bird - American Robin (Turdus migratorius)" by Carandoom

"Rehabber Update On The Gray Squirrels" by audreyjm529

"Male Downy Woodpecker" by ShenandoahNPS

"American Toad" by marknenadov "Eastern Painted Turtle" by U. S. Fish and Wildlife ServiceNortheast Region

"Common Eastern Bumblebee - Bombus impatiens, Julie Metz Wetlands, Woodbridge, Virginia" by Judy Gallagher

URI, RIGIS Ecological Communities (2011), RIDEM Lakes and Ponds 24k, RIDEM Rivers and Streams 24k

WILDLIFE

Supporting Existing Wildlife Communities

The presence of wildlife in the North End highlights the ecological value that persists even in fragmented urban landscapes. Species could serve as touch points for community learning, encouraging curiosity, stewardship, and deeper relationships with the land. Understanding the species currently present lays the foundation for designing spaces that support both biodiversity and human connection.

Mammals

The urban and post-industrial landscapes of the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods of Providence support several mammal species. The patchwork of wooded uplands, floodplain forests, wetlands, and green corridors along the West River and Canada Pond provides essential habitat for common urban-adapted mammals such as raccoons, skunks, opossums, red and gray squirrels, and Eastern cottontail rabbits. Larger species like white-tailed deer are occasionally seen, especially in more wooded or connected areas, and red foxes are known to move along river corridors. The forested and shrubby edges of the West River provide critical cover, denning sites, and access to water, while the floodplain and wetland zones offer rich foraging opportunities. Small mammals like mice, voles, and shrews thrive in the understory and grassy margins, forming an important food base for local predators. Despite fragmentation and the dominance of human infrastructure, these semi-natural habitats support some mammal species, particularly where vegetated buffers and green connections persist between habitat patches.

Fish

Fish populations are limited in the Charles and Wanskuck. Urban water bodies face significant environmental stress due to pollution, altered hydrology, and habitat fragmentation, which restrict the diversity and abundance of fish species (Solomon Tesfay Gebrekiros, Factors Affecting Stream Fish Community Composition and Habitat Suitability). Nonetheless, hardy, pollution-tolerant species such as white suckers, bluegill, and pumpkinseed sunfish may persist where there is sufficient oxygen and aquatic vegetation. Historically, the West River likely supported seasonal runs of migratory species like alewife and blueback herring, but damming and water quality issues have largely eliminated those populations (NOAA, River Herring Science in Support of Species Conservation and Ecosystem Restoration). The lack of fish passage and degraded habitat conditions due to stormwater inflows and low dissolved oxygen limit fish populations in the north end. Some residents fish at Canada Pond, but there are no formal designated fishing areas.

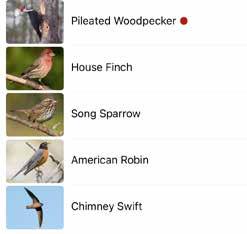

Birds

Recordings of bird calls taken with the Merlin Bird ID app reveal that the greatest bird species diversity in the North End exists where there are mature trees. Along the West River and within wetland zones, many wild birds not commonly found elsewhere such as the red-winged blackbird are present. In neighborhoods with mature tree cover, a different community of birds, including chimney swifts and cedar waxwings, can be found. Users of the wildlife observation app iNaturalist have uploaded photos they took of wild turkeys in Wanskuck Park, where forest patches and open clearings provide foraging and roosting habitat.

Insects

Terrestrial insect ecology in the Charles and Wanskuck neighborhoods is shaped by the area’s mix of forest, wetlands, fields, and urban land. Native bees, butterflies, and hoverflies are found in open, vegetated areas such as roadside edges and park clearings, where goldenrods, milkweed, and asters provide nectar and larval host plants. In wooded uplands, communities of ants, beetles, and soil-dwelling larvae contribute to decomposition and aeration, supporting forest floor ecologies. Plant-eating insects such as caterpillars, leafhoppers, and aphids thrive in stands of trees and shrubs, forming a food base for birds and other predators. Meanwhile, predatory insects like lady beetles, lacewings, assassin bugs, and parasitic wasps help regulate herbivore populations and contribute to ecological balance (Tom Royer et. al, Beneficial Insects).

The West River and Canada Pond are considered impaired by the RI Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM) for macroinvertebrates such as dragonflies, damselflies, and caddisflies due to pollution, channelization, and fill. These macroinvertebrates species are important indicators of water quality and play important roles in food webs. Mosquitoes and midges breed in wet, low-lying areas and standing water, forming a food source for birds, bats, and amphibians.

Amphibians

Amphibians such as spring peepers, wood frogs, and Eastern American toads use wetlands and floodplain forest in the West River corridor for reproduction in early spring. Canada Pond and slow-moving stretches of the West River may support species like green frogs and bullfrogs. Adjacent upland forests offer essential cover, moisture, and foraging opportunities for some species such as the Eastern red-backed salamander, which is associated with cool, moist forest soils. iNaturalist users have uploaded photos of these salamanders near the West River, indicating that some patches of forest floor habitat persist despite urban pressures. Amphibian populations are vulnerable to stressors such as habitat fragmentation due to roads, polluted runoff, and the loss of wetland habitat.

-> Salamanders of the Northeast Top: Plethodon cinereus (Eastern Red-backed Salamander), Bottom: Plethodon dorsalis (Eastern Zigzag Salamander) Andrew Hoffman

-> Birds observed in the North End Birds identified from five-minute recordings using the Merlin Bird ID app during a field visit by project team members.

WETLANDS / WATER QUALITY

Regulatory Protections

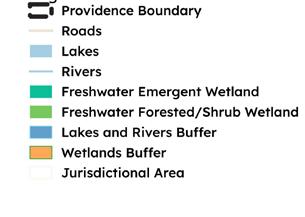

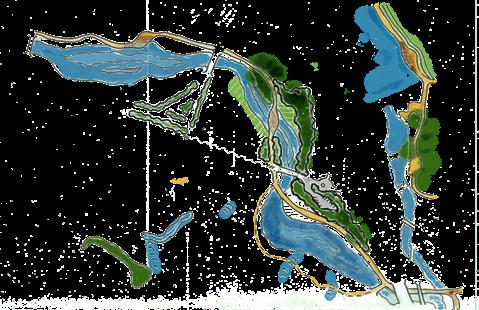

In the North End, freshwater wetlands and adjacent areas are protected under Rhode Island’s wetland regulations, which define a broad jurisdictional area extending up to 200 feet from the West River and 100 feet from Canada Pond. This jurisdictional area includes not only the water bodies themselves but also surrounding buffer zones that play a critical role in protecting water quality, habitat, and flood resilience. A buffer zone with stricter regulations extends 100 feet from the West River and 50 feet from Canada Pond. Freshwater emergent wetlands and forested and shrub wetlands in the North End have a 25-foot buffer. Significant development has already occurred within the jurisdictional area and buffer zones of the water bodies in the North End before regulations were put in place, complicating the process of restoring riparian habitat, but these regulations can help to prevent further impacts by allowing the city to preserve natural vegetation, discourage development, and direct ecological restoration efforts.

Impairment of Water Bodies

The West River and Canada Pond in the North End have both been designated as Level 5 impaired waters under Rhode Island’s 303(d) list, indicating they fail to meet water quality standards and require development of a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan. Their impairments stem from fecal coliform contamination, associated with urban runoff and sewage overflows, posing high risks to contact recreation. Additionally, both water bodies are impaired by industrial chemicals including PCBs and heavy metals reflecting the industrial use of the watershed (RIDEM). These pollutants cause elevated bacterial loads that threaten amphibians and invertebrates, while persistent toxins accumulate in the food web, affecting fish, birds, and other wildlife (Environmental Protection Agency). The pollution also makes recreational activities like swimming and fishing unsafe, contributing to the community's view of the river as a place to avoid.

Landscape Function of Wetlands

Wetlands act as natural sponges, absorbing and slowly releasing stormwater, which reduces flooding and erosion downstream. They also filter pollutants including sediments, nutrients, and heavy metals by trapping and breaking down contaminants through plant uptake and microbial activity. This makes wetlands crucial for water quality improvement. In nature, wetlands provide habitat for a vast array of species: amphibians breed in vernal pools, migratory birds nest in swamps, and insects thrive in the saturated soils and standing water. Beavers shape the floodplain with dams, creating sheltered areas where fish and amphibians spawn. These habitats often support rare or specialized plant and animal communities not found elsewhere. Although features like vernal pools and beaver dams may no longer exist in the North End, future habitat restoration along the West River could reference the landscape and ecological functions of intact wetland systems to increase ecosystem diversity and resilience.

Landscape Function of Rivers

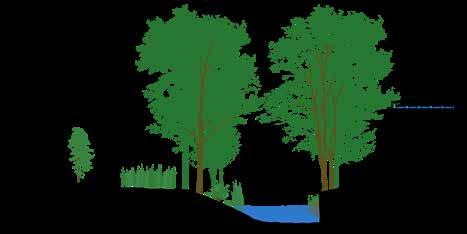

Rivers serve as ecological corridors, connecting fragmented habitats and enabling aquatic species movement across landscapes. They transport nutrients and organic matter, which nourishes both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems downstream. During seasonal flooding, rivers deposit silt and nutrient-rich sediments onto adjacent floodplains, replenishing soil fertility and creating nutrient-rich forest ecosystems. In nature, these dynamic riparian zones support fast-growing tree species such as silver maple, cottonwood, and sycamore, and promote high productivity in understory vegetation. The result is a forest community with rich species diversity, dense biomass, and strong resilience to disturbance. These periodic nutrient inputs sustain long-term forest growth and contribute to the high ecological value of floodplain systems (EPA, Riparian Forest Buffers Linking Land and Water).

Brownfield Sites

Wetlands form where the water table is close to the surface Stormwater

RIDEM Brownfields, RIDEM Lakes and Ponds 24k, RIDEM Rivers and Streams 24k

FLOODING I Context

West River floods arise due to a confluence of factors affecting the hydrology of the river system. If the West River moving through the North End is taken as the system of interest, under normal meteorological conditions,

Water In = Water Out.

During storm events, this balance shifts, so that

Water In > Water Out.

To understand why the West River is flooding, it is necessary to analyze the different components that move water into and out of the river system. The character of the river landscape as the water moves through also affects the vulnerability of built infrastructure in the system.

To mitigate flooding during storm events, some combination of landscape and infrastructural interventions is necessary that reduces the amount of water into, increases the water out of, and accommodates water moving through the system.

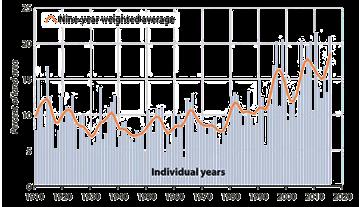

Climate Change Watershed

As the climate changes, the frequency of extreme storm events, in which high volumes of water fall in short periods of time, is projected to increase (IPCC 2023). Hotter air is capable of holding more moisture, so a warmer climate is capable of producing wetter, more damaging storms. Much existing built infrastructure worldwide is not built to accommodate the increased volumes and peak flows that occur in these flash floods, becoming overwhelmed and resulting in flooding.

Implications

Cities should anticipate recurrent extreme flooding in known problem areas in the coming decades. If the built environment is not protected, modified to accommodate projected stormwater volumes, or removed from high flood-risk areas, repetitive financial damages may be incurred. Insurance of structures in flood-prone areas may become prohibitively expensive (Neslen 2019).

The West River runs 9 miles from Lincoln, RI, through Smithfield, North Providence, and Providence, where it joins the Moshassuck River, shortly thereafter joining the Woonasquatucket River to form the Providence River, and flowing into Narragansett Bay. A sub-basin of the Moshassuck River watershed, the West River watershed covers 7.8 mi2 or 4983 acres (RIDEM 2011). Fifty-two percent of the land area is developed, and 22.9% of the surfaces are impervious (concentrated in the southern and eastern portions). The towns of Lincoln and Smithfield are partially sewered, while North Providence and Providence are completely serviced by municipal sewers, with stormwater outfalls along the West River.

Implications

Upstream contributions to downstream flooding are determined in part by land use and land cover. Depending upon particular surface qualities, up to 95% of precipitation on impervious surfaces may run off into stream channels if not intercepted by pervious surfaces or catchment basins and infiltrated in place (Forman 2014).

Upstream of the project focus area, the high concentration of impervious surfaces as compared to natural conditions, as well as the presence of municipal storm drains, may result in significant volumes of stormwater runoff entering the North End via the river. Reducing the volume of stormwater entering the area through the river channel is contingent on land surface modifications in upstream municipalities. Reductions in impervious surface and construction of flood storage upstream requires management by upstream municipalities and collaboration across municipalities in the West River watershed.

MOSHASSUCKRIVER

Culverts / Bridges

FLOODING II

Water In: Sewer / Stormwater

The City of Providence has a mixed system of combined and separated sewers. The Narragansett Bay Commission, a regional entity, manages the effluent from the North End's combined sewer pipes and separated sanitary pipes, which is delivered to Fields Point Wastewater Treatment Plant on the Providence River.

Precipitation in the neighborhood falls either on the catchment areas of the combined system or the separated system (some water also infiltrates in place on pervious surfaces such as lawns and parks). Stormwater falling on the combined system is delivered to Fields Point, except in the case of extreme weather events when excess rainfall overwhelms the system and a portion is released at combined sewer overflows (CSOs), of which there are two in the focus area. Stormwater in the separated system outfalls directly into the West River throughout the project focus area.

Implications

Most of the North End is covered in impervious surfaces. The separated storm drains collect unfiltered runoff from this large catchment area and deliver it directly into the river, not only exacerbating flooding in storms but damaging water quality by adding pollutants such as road salts, hydrocarbons, pesticides, waste and more. Runoff water is also significantly hotter than the river water, affecting some aquatic species negatively. The two CSOs in the focus area deliver unfiltered sewage into the river during heavy rainfall, posing significant hazards to human and ecological health, as well as exacerbating flooding.

Combined Sewer Overflow Abatement Program

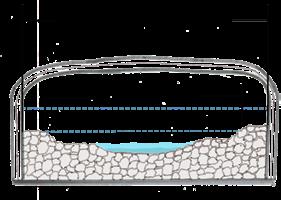

In 1993, the Narragansett Bay Commission approved a regional CSO abatement program to reduce combined sewer overflows, which are a violation of the Federal Clean Water Act. The project, also called RestoredWaters RI, consists of three phases including constructing large storage tunnels below the city to

-> (Far Left) Combined Sewage Storage Tunnel

A tunnel below Providence for temporarily storing combined sewage in storm events constructed as part of NBC's CSO Abatement Program

Source: Narragansett Bay Commission

temporarily store combined sewer flows awaiting treatment after storm events, sewer separation projects, constructed wetlands, and interceptors. Phase III of the project began in 2021. The project has succeeded in intercepting 1.1 billion gallons of combined water and wastewater each year (Narragansett Bay Commission).

-> (Left) Fields Point Wastewater Treatment Facility

The largest wastewater treatment facility in Rhode Island, located along the Providence River, which serves the North End neighborhoods.

Source: PVD Eye Field's Point Wastewater Treatment Facility

Impervious Surfaces in the North End

WANSKUCK

CHARLES

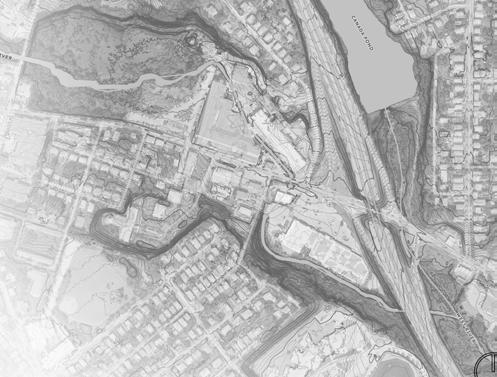

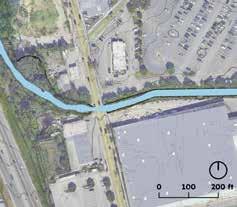

FLOODING III

Water Out: Flood Storage and Neighborhood Infrastructure

Industrialization and urbanization of the North End resulted in the development of the West River's natural channel and floodplain. Damming of the river for industrial mills was accompanied by the construction of buildings directly adjacent to the river (such as Wanskuck Mill), some of which were later replaced with big box stores and parking lots. Channelization of the river, which includes straightening, building up of banks, and, in places, armoring (containing within concrete walls), was used to direct water and often thought to reduce flood risk. New transportation routes crossing the river required the construction of bridges and culverts. In some cases, infrastructure was built directly over the river, burying it underground, such as under the McDonald's at Branch Avenue Plaza.

Implications

Natural river systems feature irregularly shaped channels that meander laterally over time and, depending upon topography, are usually surrounded by an adjacent floodplain where flooding is regularly expected (Forman 2014). Floodplains provide flood storage during storm events, where stormwater is able to spread and slow, mitigating downstream flooding.

Built infrastructure in the floodplain precludes flood storage and exposes that infrastructure to flood risks, as shown in the FEMA flood risk map and evidenced by the September 2023 floodprint map (right). Repetitive flood events, especially when factoring in climate change effects, may incur financial losses that become economically unjustifiable.

Culverts and Bridges

Undersized culvert and bridges cause flooding when the aperture through which water passes is too small to evacuate upstream floodwater, causing it to back up and overtop riverbanks.

Dechannelization, that is, removing riverbank armor and restoring irregular form, may help slow water and improve both riparian ecology and hydrological connection of the river and its floodplain. (Forman 2014).

Legacy infrastructure such as culverts, bridges and drainage pipes were sized to meet historical flood volumes. Removing and/or upsizing this infrastructure may be necessary to accommodate new peak flow and stormwater volumes precipitated by climate change.

-> Defunct Rail Bridge near Home Depot

A defunct rail bridge formerly serving a mill on the site currently occupied by Home Depot may be undersized for current stormwater volumes and causing flooding in the area (for example in September 2023).

Sections of the West River were sequentially dammed, channelized, and/or filled throughout the neighborhood's industrial history. Construction of

transportation corridors, such as Route 146, further constrained the river's course.

The West River is buried in a culvert under the McDonald's at Branch Avenue Plaza and daylights below the restaurant. This culvert may be undersized and backing up in flash floods.

-> Channelization 1936-1962

Historical aerial imagery of the project focus area from Wanskuck Mill in the upper left to the railroad in the lower right show modifications in the river system.

The naturally irregular river shape was straightened around mill infrastructure.

Draining of ponds during the construction of Rte 146 in the middle of the 20th century and straightening the river course. -> McDonald's at Branch Avenue Plaza

1. SELECTIVE SHIFTS

Overview

The aim of this design is to minimize conflict with existing development while meeting the project goals of enhancing the north end's flood resilience, the ecological health and water quality of the West River, community access to the river, the quality and quantity of recreational spaces, and the connectivity between Charles and Wanskuck by pursuing strategic infrastructural changes and repurposing existing green spaces.

Upper Zone

• Selective depaving

• Infiltration basin installation

• Additional community space & improvements to existing public space

MIDDLE ZONE FLOODPLAIN RESTORATION NEW PROGRAMMING SPACES INFILTRATION BASIN INSTALLATION

Lower Zone

• Undeveloped lot acquisition

• Infiltration basin installation

• Bottleneck upgrade/removal of undersized culverts, defunct bridge

• Selective depaving

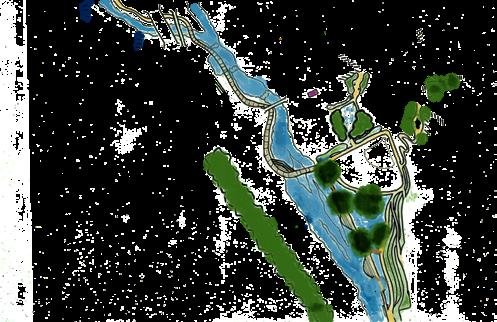

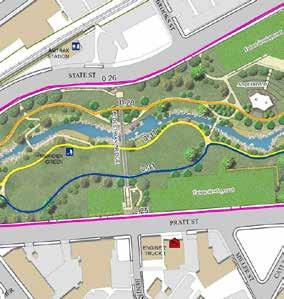

2. GREENWAY

Overview

This design alternative features a multi-modal path anchoring a linear park connecting neighborhoods along the river. Formalized connections from the river path to neighborhood streets draw residents to recreation areas along the river. While this design provides new recreation opportunities, including continuous public access to the river and regional greenway network, it requires some removal of existing commercial infrastructure and may not fully mitigate flood risks.

Precedent Photos

Upper Zone

The multi-modal path enters from the northwest. Branch Ave Plaza has been reduced and the floodplain expanded. Filtration basins clean stormwater and CSO discharges.

Middle Zone

The West River Greenway meets the Canada Pond Greenway and heads south through formalized recreation spaces alongside the restored West River floodplains and wetlands.

Lower Zone

The greenway path passes by more recreation spaces and filtration basins before entering an expanded floodplain where Home Depot stood and exiting the area by overpass.

-> Waterloo Greenway

Formalized recreation spaces and trails along a new greenway. Austin, Texas.

Source: MVVA Inc.

Multi-Modal Path

Neighborhood Connections

PedestrianFriendly Areas

-> Brickline Greenway

Bicycle signage and wayfinding along a bike path. St. Louis, MO.

Source: Wikimedia

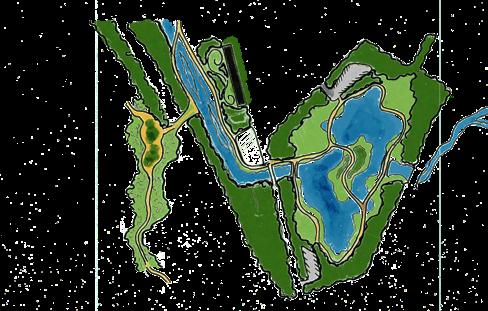

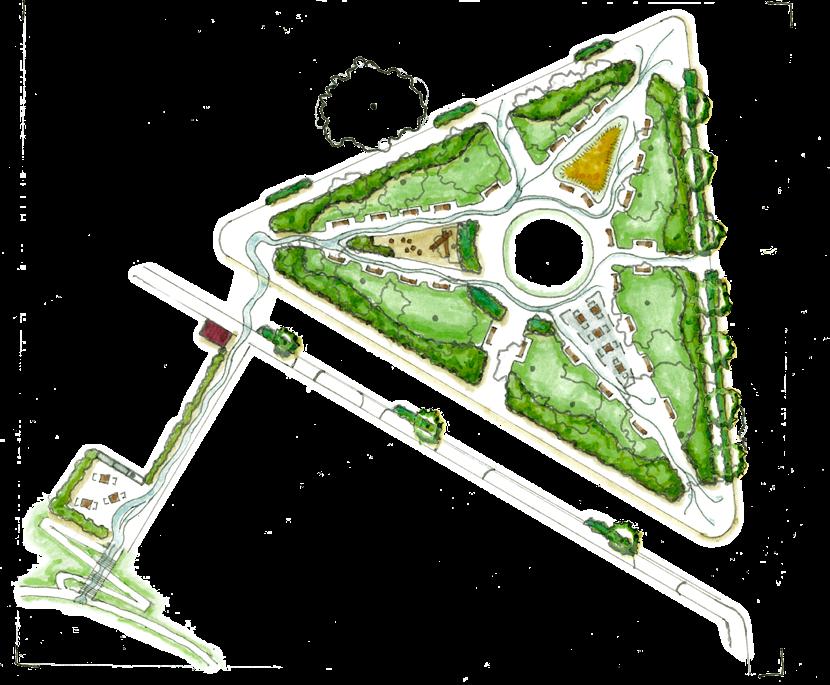

3. LET IT FLOW

Overview

A widened floodplain and various flood-storage techniques decrease the impact of natural flooding rhythms on infrastructure while improving water quality and wildlife habitat. Programming and recreational space is created along a path following the river's edge that honors the natural, native, and cultural diversity of the land through signage and self-led activities. Lost shopping resources will need to be replaced elsewhere within the neighborhood, and the support of private parcel owners will be vital to the implementation of this plan.

Upper Zone

To expand river flooding capacity, industrial lots are depaved, the river is dechannelized, and the riverbank is restored. A pedestrian and wildlife underpass is established under 146. Programming space is created along the river.

Middle Zone

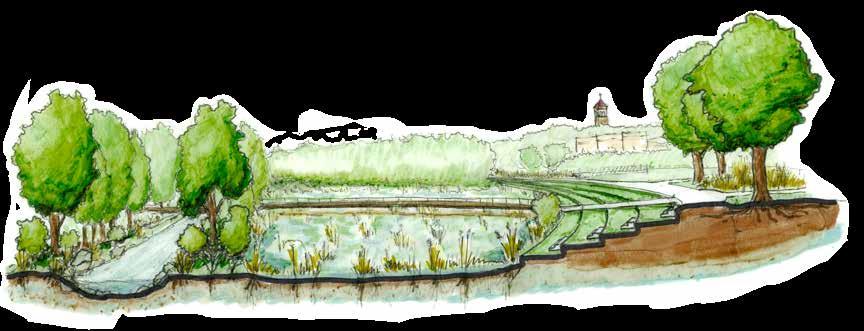

Pool and riffle design with an expanded riparian zone expands river and uses natural plant systems to filter contaminants. A green terrace with trees and seating leads to an excavated wetland increasing flood storage capacity.

Lower Zone

An extended detention basin with center island and trails expands flood storage and recreational space. A pedestrian bridge connects a new powerlines park to West River. Defunct railroad bridge is removed.

Precedent Photos / Diagrams

Section A-A' (NTS)

Canada Pond is managed for flood storage, with a terrace down to a dock for recreational use and bank stabilization.

Global Rivers Path

Under/Overpass

Habitat Zone

Wetland & River Bike Hub

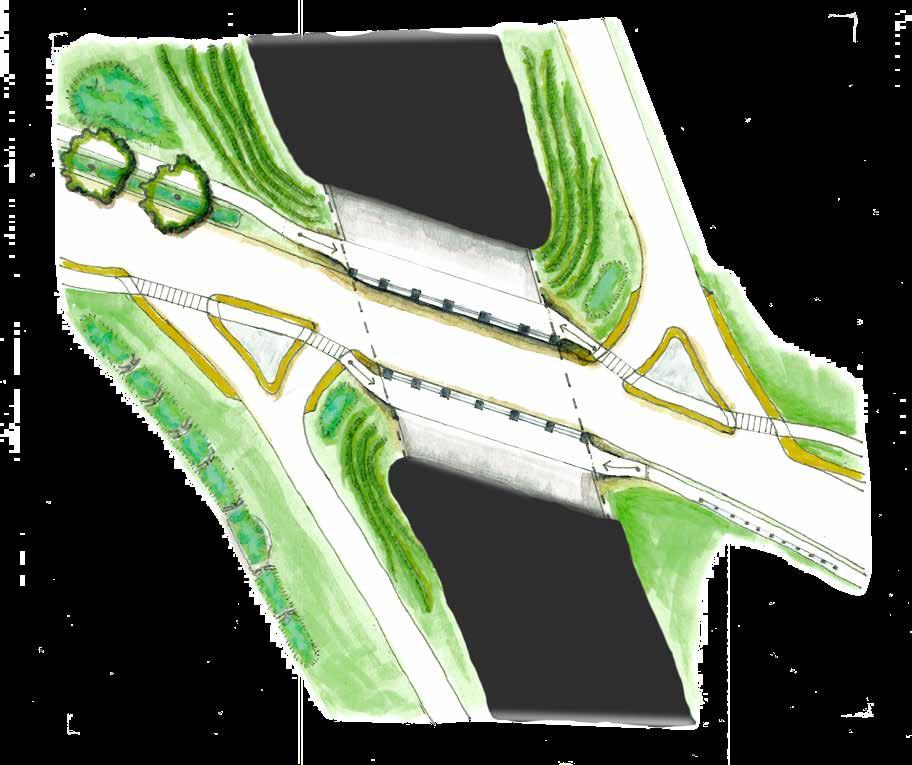

Upper Zone: Pedestrian and wildlife underpass

Middle Zone: Forested terrace leads to water.

Lower Zone: Pedestrian and wildlife overpass

The Cleveland Flats CMG Landscape Architecture

Rovert L.B. Tobin Land Bridge | Texas (c)2025 by Justin Moore www.texasbyair.com

The Cleveland Flats CMG Landscape Architecture

Boardwalk with

Low Intervention vs. High Intervention Strategies Approach

Low Intervention

As the West River Resilience Project is still in the initial stages of a long-term comprehensive visioning for the North End neighborhood, this document presents a toolkit of landscape-based strategies–rather than a finalized design–that can be used by the city and community to further develop plans for the West River corridor.

The following pages present two sets of design strategies for the project, a low intervention toolkit and a high intervention toolkit. In some instances, these toolkits could be implemented sequentially, where certain strategies in the low intervention toolkit serve as the basis for developing high intervention strategies.

Each toolkit presents broad neighborhood-level strategies and then zooms into four smaller urban landscape typologies that can be found in various locations across the neighborhood. While the strategies are represented here in specific locations and configurations as examples, these strategies are intended to be modular and replicable across similar landscape typologies and spatial conditions in the neighborhood. Some toolkit strategies may also be appropriate in multiple landscape typologies.

Strategies that do not alter existing patterns of development. Buildings in current use are not removed; however some minor land use changes are proposed. Cost and logistics of implementation are lower, but non-negligible.

Urban Landscape Typologies

Commercial Area

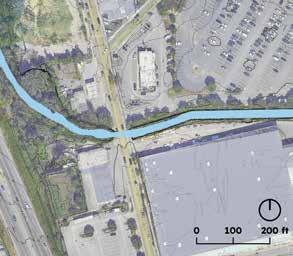

Sections of the river developed with box stores, expansive parking lots, armored river channels, bridges and culverts. The example shown is a section of Charles St adjacent to Home Depot.

Stacked Functionality

High Intervention

Strategies that alter existing patterns of development, including in some cases the removal of buildings in current use and altering of landforms. Cost and logistics of implementation are greater.

Natural Area

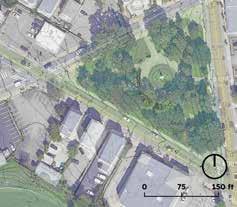

Sections of the river surrounded by natural land cover or open space including wetlands, riparian habitat, and parks. The example shown is a river section passing by Prete-Metcalf Field.

Landscape interventions that serve multiple purposes ("stacked functionality") are encouraged as efficient and cost-effective solutions. Rather than responding in isolated instances to flooding issues as they arise, this project proposes that a comprehensive plan for the West River in the North End can proactively resolve multiple issues at once, such as flooding, river ecosystem degradation, lack of public access to the river, and neighborhood disconnection.

Strategies included in the following toolkits are identified with the colored labels that meet each respective goal:

Streetscape

Neighborhood streets in the vicinity of the river focus area that serve as transportation corridors, public space, as well as sources of stormwater runoff. The example shown is Hopkins Square.

Flood Resilience

Highway Crossing

Locations where neighborhood streets cross under (or over) major transportation routes that bound the neighborhood (highways, railroads, etc.) The example areas are Rt 146 underpasses.

Strategies that mitigate flood risk and minimize disruptions and damage caused by extreme storm events

Water Quality / Ecological Health

Strategies that improve water quality in the West River and restore ecosystems within and adjacent to the River

River Access / Recreation

Strategies that strengthen the public's relationship with the river through physical/visual access, programming, or recreation

Neighborhood Connectivity

Strategies that simplify and

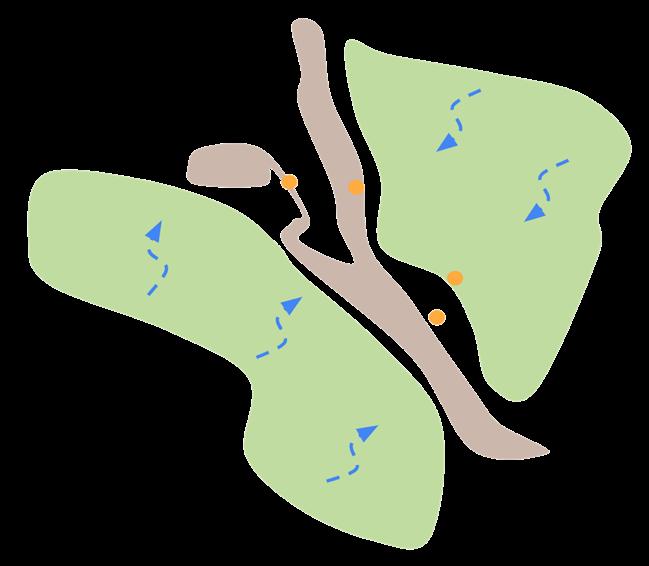

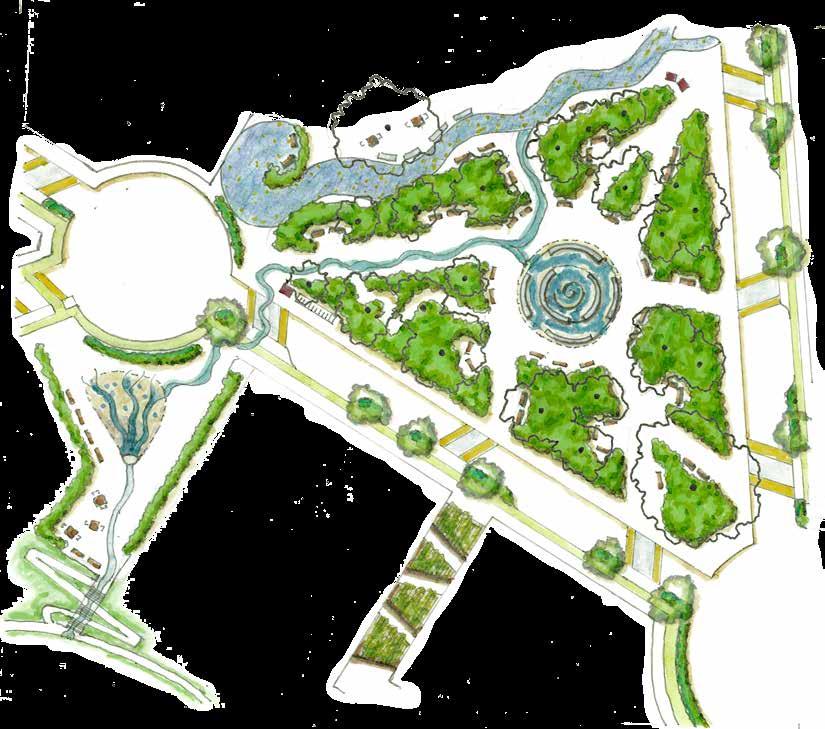

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

Low Intervention Toolkit

This design expands the river floodplain within existing open space, and uses in-stream techniques to slow river flow and connect the river to adjacent wetlands. Trails and programming spaces are added along waterways. It is assumed that the river's water is safe for secondary contact, but not primary contact. Phase one of low interventions for high ecological and flood mitigation impact are removal of the defunct railroad bridge and removal of debris within river, riparian zones, and wetlands.

Green infrastructure is added to streets throughout neighborhoods and portions of large parking lots are replaced with pervious paving to reduce and filter stormwater entering stormdrains. Community members are engaged in the development of street art that reduces vehicle speed and improves community ownership of outdoor spaces.

The low intervention design is established as a first step in flood mitigation and can be adapted for phasing into the high intervention designs at a neighborhood or modular scale.

Benefits

• Expands river floodplain within existing open space and habitat space within cement channels.

• Utilizes minimally invasive green infrastructure techniques that can be implemented in a modular form as parcels allow.

• Increases community connection to river and ownership of recreational spaces and streetscapes through community led design.

Challenges

• Requires substantial shifts in the impervious surfaces in the watershed upstream of the focus area to effectively mitigate flooding impact on infrastructure (i.e., the interventions shown where are not likely to completely mitigate flood risk to infrastructure).

Green Streets

Expanded Floodplain

Green Streets

Green streets are established within residential areas and along main thoroughfares to mitigate and filter stormwater runoff before it enters stormdrains. These features also calm traffic and support shade trees.

Defunct railroad bridge in the channel between home depot and Walmart is removed to prevent build-up of debris and increase water holding and flow capacity of channel in high rain events.

Selective Riverbank Expansion

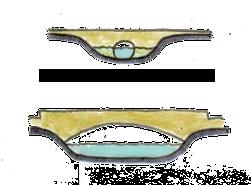

River bank is excavated to expand within open space, establishing high and low flow channels. Riparian zone is expanded to a minimum of 120% of new bankfull width. Bankfull is the top level of water capacity in a river before it floods.

Activate Open Space

Along River

Programming space and trails are formalized within existing parks and established along riverbank and within open space that is currently without amenities. All persons paths include play and sensory space and self-guided educational activities.

Ecological Management Of Natural Spaces

• Requires owners of large plots of impervious surface to collaborate with city staff for green infrastructure implementation.

Manage ecosystems to increase biodiversity and habitat for plants and wildlife. Manage invasive species for protection of wetland and riparian habitats.

• Green space remains disconnected by infrastructure.

Remove Defunct Railroad Bridge

COMMERCIAL AREA

Low Intervention Toolkit

Selective depaving of parking lots is a scalable way to reduce flooding by increasing rainwater infiltration and slowing runoff. When adjacent to the West River, it would also restore riparian habitat and create opportunities for dechannelization.

Revegetating unused lots near the West River would reduce flooding by intercepting runoff into the river. Marked with signage and trails, naturalized lots could provide community green space and support wildlife.

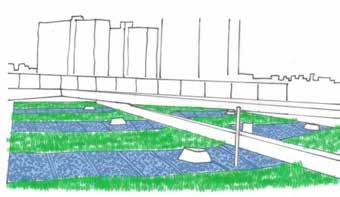

Pervious Paving

Pervious paving materials like porous concrete or permeable pavers allows rainwater to soak through the surface into the ground, reducing flooding.

Blue roof systems temporarily store rainwater on flat rooftops, slowly releasing it over time or allowing it to evaporate, which keeps stormwater from overwhelming sewage/water treatment systems.

Existing Conditions

NATURAL AREA

Low Intervention Toolkit

Rain gardens are excavated and planted with native wetland vegetation in the park to collect, infiltrate, and filter water. These basins reduce pooling and flooding, filter pollutants, and create habitat while vibrant flowers provide visual interest to park goers.

The central ballfield is repurposed as dynamic open space with a new path way, shade trees, beds of native vegetation, and a natural playground with logs and stones. Some lawn space is left for sports, food truck access, farmer's markets, or other events.

Turf grass is replaced with native grasses and flowers lightly shaded by staghorn sumac, creating habitat for wildlife. Intersecting trails and nooks with benches create opportunities for sensory and aesthetic experiences.

An all-persons Trail is an accessible path designed for people of all ages and abilities. Building one according to US Forestry Service standards along the West River would reconnect the Charles and Wanskuck communities along the river by providing safe access. It would help turn the river into a visible, shared resource rather than an inaccessible place people avoid.

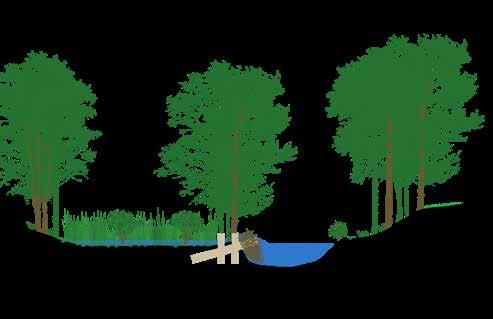

Engineered log jams are intentionally installed woody material within rivers. Building these in the West River would cause it to flow over the western berm, fanning out into the adjacent wetland. By allowing the river to occupy more of its natural floodplain, flood waters could be slowed, stored, and spread out over a wider area. Log jams also provide important habitat for aquatic species and are minimally invasive to install when compared to dechannelization, which would require excavation of contaminated sediments.

Existing Conditions

-> Rain gardens at UMASS Amherst

-> Dexter Training Grounds Park

An open turf grass field used originally by the National Guard was converted to park space. Source: Providence Preservation Society

-> Staghorn Sumac Meadow

Staghorn sumac forms a low canopy over a grassland.

Rain gardens around the John Oliver Design Building collect and infiltrate water.

SENSORY GARDEN ENGINEERED LOG JAM

RIVER TRAIL

WETLAND

STREETSCAPE

Low Intervention Toolkit

Strategies Precedent Photos / Diagrams Formalized Connections

Formalized entrances and pathways between Hopkins Square, Prete-Metcalf Park, and the West River improve access and encourage movement between spaces. Marked with banners and informational signs, these entrances act as thresholds, defining distinct experiences for pedestrians and cyclists as they move through the corridor. This strengthens spatial connection and increases use.

Street Painting

A community-led organization could be approved to paint murals on streets and intersections around Hopkins square, designating the area as a community space where traffic slows. A river-centered theme would improve public visibility of local water bodies and associated ecologies, recruiting care and investment.

-> Planned Entrance Gateway to Woonasquatucket Greenway

Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council

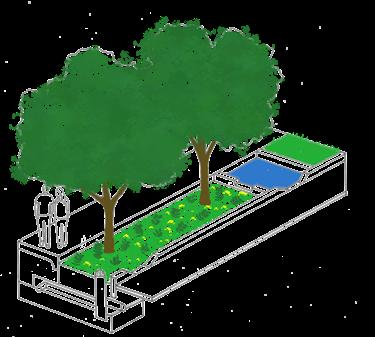

On-street infiltration basins intercept stormwater, infiltrating it into the ground and releasing it into the air through evaporation. A perforated pipe is installed beneath the basin to pipe out excess water. Slows traffic when built as bump-outs.

-> Intersection Repair Program

Members of the community paint murals on intersections in Portland, Oregon.

-> Bump-out Infiltration Basin

Short, on-street infiltration basins are strategically placed to intercept stormwater before entering the storm drains.

-> Tree Trenches

Extended trenches along sidewalks provide stormwater infiltrations as well as space for street trees and plantings.

Existing Conditions

STREET PAINTING OF RIVER

POCKET PLAZA WITH TABLES AND JERSEY BARRIERS

HIGHWAY CROSSING

Low Intervention Toolkit

Vegetated swales with curb cuts are established along roadsides and parking lots to slow, filter, and infiltrate runoff from hardscapes. Check dams are added along sidewalks to increase water holding capacity.

-> Meridian Hill Bioswale

D.C. (Erica Fischer)

Right-of-way hillsides are terraced using triangulated luna berm tree planting, native grasses on contour, or trees on contour with rock or stone berms with infiltration basins at base. This slows and filters runoff from roads before entering waterways or stormwater drains, decreases erosion, and establishes edge spaces for wildlife movement.

-> Terraces near a Right-of-Way

Lights and a reflective or textured ceiling are added to underpasses to improve atmosphere and safety for pedestrian use. Artwork designed by Charles and Wanskuck residents is painted onto columns to increase communal ownership of the space. Sidewalk is widened by raising sidewalk along existing angled retaining wall.

This design increases safety for pedestrian and cyclist use at the Branch Avenue underpass, establishes roadside swales with checkdams and vegetated Route 146 roadbed terraces create a barrier between vehicles and pedestrians while decreasing and filtering stormwater before it enters stormdrains.

Existing Conditions

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

High Intervention Toolkit

The high intervention toolkit explores a dramatic long-term revisioning of the landscape around the West River. The primary focus is to improve flood resilience and restore the river ecosystem by creating a greenway that knits the neighborhood together.

The reality of river flooding would be acknowledged by renaturalizing the floodplain through removal of built infrastructure in low-lying ares. A multi-modal path threading through the focus area would connect public amenities along the river and feed into the regional greenway network. Improvements in water quality would allow for the public to interact with and spend time near the river. Ecosystem health and connectivity would improve, inviting a diversity of plant and animal species into the neighborhood.

The far-reaching proposals of this toolkit would require certain accommodations to be viable, for example compensating for the loss of commercial space important to the community and accommodating the unhoused who currently dwell in the West River corridor.

Extensive land use changes would require negotiation with land use owners and cross-sector collaboration of public agencies, non-profits, and private businesses.

Benefits

• Mitigates flood risk by expanding flood storage and removing vulnerable infrastructure

• Improves ecosystem health and connectivity

• Establishes an interconnected plan for the river corridor, while allowing for individual site-level interventions to be implemented as funding and opportunities arise

• Provides ample recreation opportunities and public access to natural space

Challenges

• Requires removal of important commercial spaces

• Higher costs associated with implementation

• Involves changes in land use and ownership

Renaturalize River Floodplain Establish a Multi-Modal Greenway Path

Manage Upper Canada Pond for Flood Storage

Retrofit the Upper Canada Pond Dam to allow for variable water levels in storm events and dry weather.

Storing floodwater in Canada Pond could reduce flooding downstream.

Build New Routes Across Neighborhoods

Create new pedestrian underpasses or overpasses across significant infrastructural barriers such as highways and rail lines. Improve multimodal experience of existing bridges and underpasses.

Improved neighborhood connections promote usage of public space by a broad cross-section of the community

Create Complete Streets

Build out a network of multimodal streets in the neighborhood to strengthen connections between residential areas and the river for a broader cross-section of residents. Include green infrastructure for stormwater management.

• Requires sustained and comprehensive collaboration between city, community, businesses, and other organizations