EMERGENCE OF PLACE

A Village Center Cultural Connectivity Plan

Prepared for the Town of Amherst, MA

G.Brown | J. Harper | J. Wang

The Conway School Winter 2025

A Village Center Cultural Connectivity Plan

Prepared for the Town of Amherst, MA

G.Brown | J. Harper | J. Wang

The Conway School Winter 2025

A Village Center Cultural Connectivity Plan

Prepared for the Town of Amherst, MA

Many thanks to all who contributed to this project. Special thanks to the members of the Core Team, including Pete Westover, Billy Spitzer, Steve Roof, Erin Jacque, and Kari Blood for their time and valuable insight. We would also like to thank Conway faculty and staff and guest reviewers for their feedback and guidance. Finally, we greatly appreciate all of the input from stakeholders and community members who met with us and informed this project.

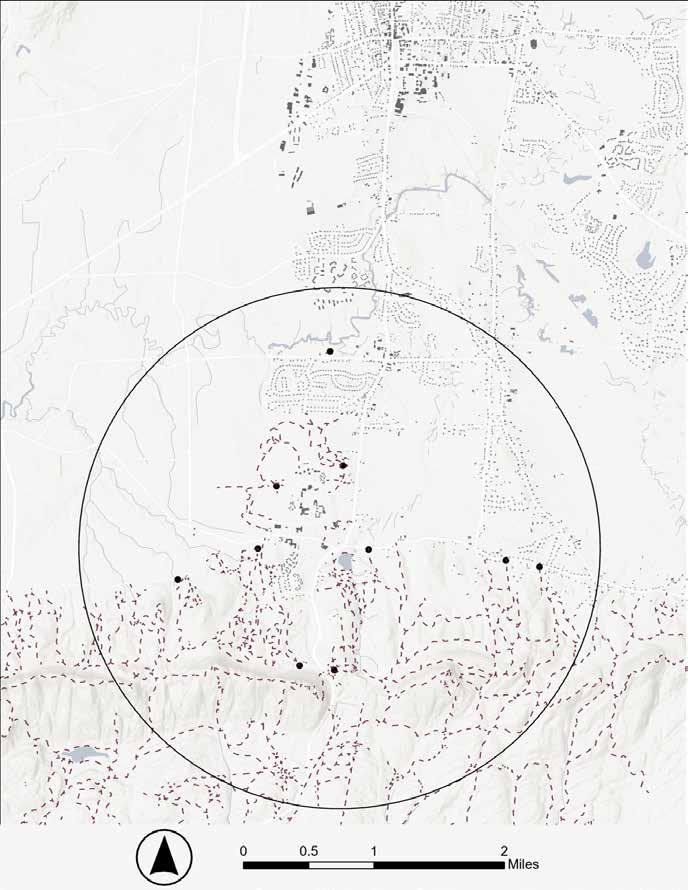

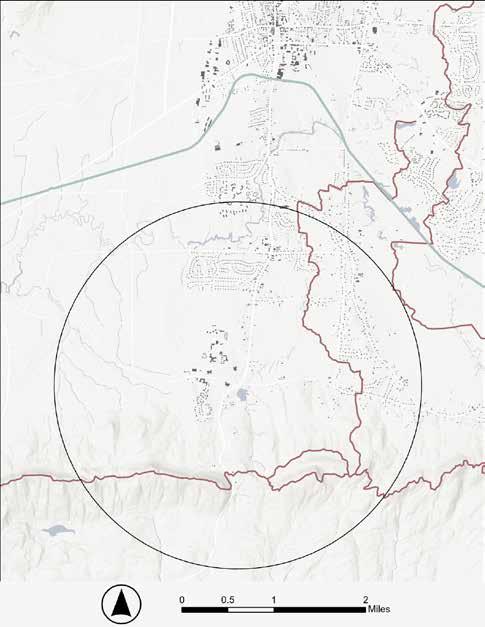

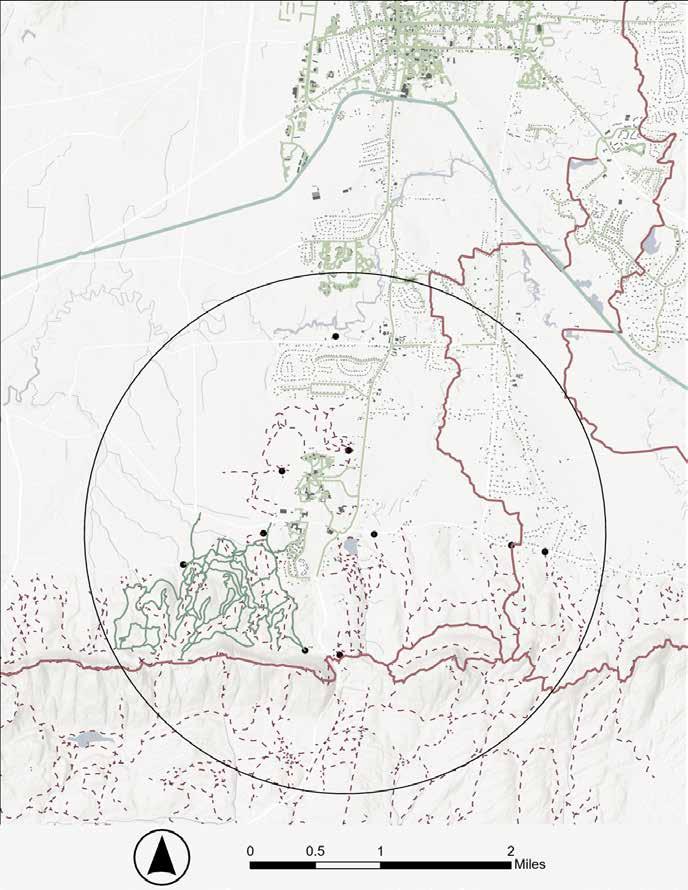

Located in the southern extent of the town of Amherst, MA, and situated at the northern foot of the Mount Holyoke Range, the focus area of this project encompasses a two-mile radius from the intersection of Bay Road and West Street/Route 116. The Town of Amherst designated this area (currently called Atkins Corner) as a Village Center in 1969, with plans for focused development.

During the winter of 2025, a team of students from the Conway School worked with the Town of Amherst, Conservation Works, Hampshire College, the Hitchcock Center for the Environment, Kestrel Land Trust, and community members to develop a cultural connectivity plan for the focus area. As understood for this project, a cultural connectivity plan aims to improve the physical connections within a town and foster interactive conditions between different cultural groups and institutions, creating a more inclusive and vibrant environment.

The Conway student team analyzed the existing conditions and connectivity networks within the focus area through GIS mapping and ground truthing. Community engagement via a series of small meetings and interviews provided more details about the human experience of place and the desires for connectivity within the focus area as well as more broadly across the region.

Analysis and engagement showed that although the area is home to several cultural institutions and a robust series of trail networks, it lacks some key infrastructural connections and wayfinding cues for safe navigation by pedestrians and bicyclists, both within the focus area and between regional areas. Residents and visitors espoused fondness for the rural character, but expressed that there is a general lack of collective culture in the Village Center.

As a connectivity project oriented towards cultural goals, this plan focuses on place making, with the understanding that the emergence of a distinct cultural center can be fostered through the curation of conditions in the built environment. This plan suggests improvements to increase accessibility, safety, and ease of navigation within the focus area. It also envisions intentional multimodal connections within a broader regional network.

BayRoad Route 116 West Street Bay Road

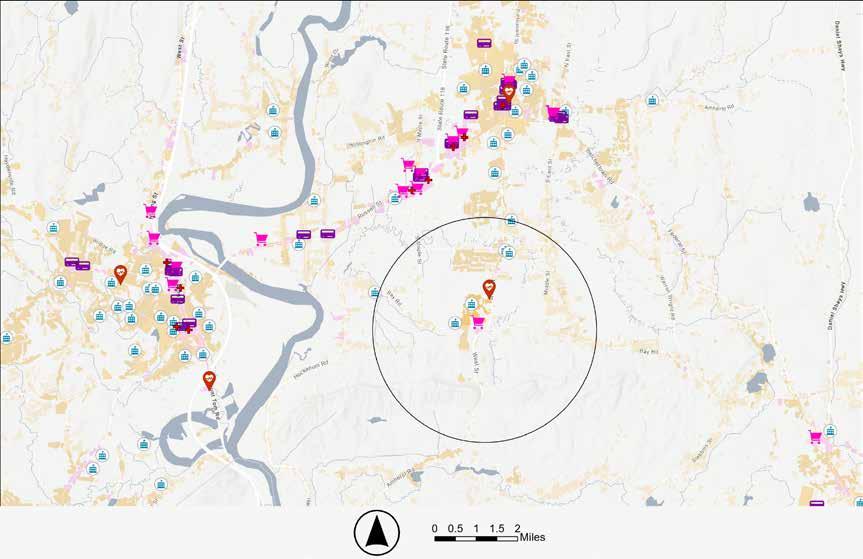

Predominantly located in the southern extent of the town of Amherst, MA and situated at the northern foot of the Mount Holyoke Range, the focus area encompasses a two-mile radius from the intersection of Bay Road and West Street/Route 116 (shown as a circle in all of the following maps in this document). This scale was chosen to capture the surrounding area and identify key connections between what is currently known as the Atkins Corner Village Center and neighboring communities. To understand context and connectivity potential, broader areas have been assessed in some of the analyses.

As understood for purposes of this project, a cultural connectivity plan aims to improve the physical connections within a town and foster connections and interactions between different cultural groups and institutions, creating a more inclusive and vibrant environment

The focus area is home to several cultural institutions and a series of trail networks, but lacks some key infrastructural connections for safe navigation by pedestrians and bicyclists. This plan suggests improvements to increase accessibility, safety, and ease of navigation within the focus area. It also envisions intentional multimodal connections within a broader regional network. As a connectivity project oriented towards cultural goals, this plan focuses on place making, with the understanding that the emergence of a distinct cultural center can be fostered through the curation of conditions in the built environment.

In 1969, the Town of Amherst designated what is currently called Atkins Corner as a Village Center with plans for focused development. It is one of five Village Centers currently in the town.

The Village Centers of Amherst are meant to function as decentralized units that support future concentrated growth and development while mitigating the effects of sprawl. In 2004, a Comprehensive Planning Study conducted by UMASS Amherst for the town added that these villages should adopt mixed-use or form-based planning approaches that accommodate retail, office and residential uses simultaneously. The study also suggests creating infrastructure for circulation that allows for convenient and safe access for pedestrians, bicyclists and vehicles alike, as well as standards of design that help to create a unified, attractive and unique space. (Madan, 2004)

There have been multiple planning efforts devoted to this focus area in the past. This project aims to support existing priorities of the Town as informed by their current Master Plan (2010), as well as integrate long term action items found in their Climate Action Adaptation and Resilience Plan (2021) and Open Space and Recreation Plan draft (2024). These goals highlight the interconnected ecologies of human and landscape, thus necessitating a holistic approach to the planning process.

Create Village Centers that are walkable, attractive and efficient.

Utilize “greenways” and walkways to tie neighborhoods, public spaces, etc. together and make it easier for Amherst residents to walk or bicycle to more destinations.

A balanced, inclusive, accessible, safe, environmentally responsible transportation and circulation system that serves users of public transit, pedestrians, bicyclists and drivers and that is connected within and among different modes both in town and to the region.

Increase access to green space, recreation, and community gardens.

Balance smart growth and conservation through the integration of green space and nature-based infrastructural solutions.

Action Item: continue to develop and improve a network of trails, sidewalks, and bike paths between neighborhoods (specifically Environmental Justice Communities), conservation and recreation lands and commercial areas. Ensure that trail development includes those that are handicap accessible and multi-use serving walkers, runners, bicyclists and wheelchairs.

Action Item: Establish and enhance a walkable system of neighborhood parks and playgrounds in and around the Town Center and outlying village centers, connected to other Town trail systems and public transit, with features that meet the recreational needs of children, youth and elders.

Representatives from the Town of Amherst, Conservation Works and several key institutions within the study area—Hampshire College, Hitchcock Center for the Environment, and Kestrel Land Trust— comprised the core group for this project. These institutions were regularly involved in this planning process and given opportunities to provide feedback to guide recommendations.

Conservation Works has been actively involved since the project’s inception in 2016. They are a consulting firm and a key facilitator in regional conservation efforts. Possessing extensive local knowledge and deeply rooted connections, they have been instrumental to this project.

“Enhancing land conservation and ecological resiliency in cooperation with public, private, and non-profit land holders.”

Hampshire College is a landmark institution and the largest land owner within the focus area, making the College a key collaborating partner for this project. It is part of the Five Colleges Consortium and is home to a “cultural village” within the focus area—a group of independent institutions that exist in proximity to foster cultural interactions and learning. These institutions include The Eric Carle Museum for Picture Book Art, The Yiddish Book Center, and The Hitchcock Center for the Environment.

“Fostering a lifelong passion for learning, inquiry, and ethical citizenship that inspires students to contribute to knowledge, justice, and positive change in the world and, by doing so, to transform higher education.”

Hitchcock Center for the Environment has been encouraging environmental literacy in the Connecticut River Valley since 1962. They run extensive experiential education programs, both at their headquarters within the focus area and more broadly across the region. Their ecological knowledge and connection with the local landscape is valuable for the project.

“Educate and inspire action for a healthy planet.”

The educational framework centers on five fundamentals: understanding principles of ecology, valuing place, promoting resilience, demonstrating sustainability in the built environment, and educating for active citizenship.

Kestrel Land Trust has been helping to preserve lands in the Connecticut River Valley since 1970. The recent relocation of their headquarters to the focus area alongside their stewardship of nearby conservation land positions them as a collaborator in this project.

“Kestrel Land Trust conserves and cares for forests, farms, and riverways in the Connecticut River Valley of Western Massachusetts, while nurturing an enduring love of the land.”

The focus area is held by the ecologies of the Mount Holyoke Range to the south and Fort River tributaries to the north. The valley is situated on sedimentary deposits of glacial Lake Hitchcock. Colonial land use in this area capitalized on this feature and manifested as woodlots, pastureland and agriculture. Today, successionary forest, wetlands, and grassland ecologies proliferate. This varied landscape supports diverse habitats and wildlife, creates opportunity for recreational activities, and provides a living classroom for environmental education. It also poses some challenges for navigation and connectivity through areas of rough terrain or wetlands and streams.

Aptly named ‘Pitowamwachu’ by the Nipmuc, meaning “where water comes out of the hill”, the Mount Holyoke Range slopes north to the saturated home of wetlands and tributaries of the Fort River. Arguably one of the most important habitat areas in the town, the largest rare species blocks and forest cores can be found here. The range is also unique in being one of the few in North America that runs both north-south and east-west.

The longest free-flowing tributary of the Connecticut River, the Fort River is considered one of the three most diverse rivers in the state of Massachusetts from a wildlife perspective. Mussels, eastern pearlfish, sea lampreys and American eels can be found within its waters. The Fort River originates in Shutesbury, MA where it is called ‘Adams Brook’ and flows southwest where it then feeds Amethyst Brook and continues to the Connecticut River.

While locals in this area refer to it as “wet”, history reveals that Amherst lost many of its wetlands during the 19th century due to dredging for agricultural practices. The Town of Amherst Wetlands Protection Bylaw regulates of freshwater wetlands, marshes, wet meadows, bogs, swamps, isolated wetlands, vernal pools, banks, reservoirs, ponds, intermittent streams and watercourses. Today, the Lawrence Swamp, four miles east of the focus area, is the largest remaining wetland in town. The floodplains of the Fort River located in the northern section of the focus area is where the majority of contemporary wetlands lie. Many of these areas are protected and managed by the Amherst Conservation Department.

The north slopes of the Holyoke Range are home to the largest blocks of continuous forest in southern Amherst. As such, this ecology is vital for wildlife from both a habitat and corridor perspective. This forest is composed of hemlock, red and sugar maples, yellow and paper birches, white pine, and others. It is also where the largest rare species core in the area resides, rendering it a critical area for monitoring and protecting.

Early colonist settlement patterns resulted in the introduction, and subsequent prevalence of, open fields for agricultural purposes in the area. The town currently has over 2000 acres of APR protected agricultural land. Farmlands have the potential to offer habitat and habitat connections for wildlife. While some fields now lay fallow and support a range of wildlife, it is unclear how current agricultural practices are impacting wildlife habitat.

The colonial legacy of agriculture in the form of apple orchards within the focus area is largely celebrated culturally through nostalgic symbology. However, this practice has also had resounding impact on the capacity for future relationship with the land as toxic lead and arsenic may still be present.

Land was considered as a sacred gift to all, the possession of no one man.

~ “The Holyoke Range Study” (MacFadyen, 1974)

“To be cultural, to have a culture, is to inhabit a place sufficiently intensely to cultivate it—to be responsible for it, to respond to it, to attend to it caringly.”

~ Edward S. Casey (Sorrells, 2013)

Indigenous people established trails through the area (Bay Road), and actively managed the land

1759

Town of Amherst separated from Hadley

1650’s European settlers and Black slaves moved into the Valley of Norwottuck, and used this area mostly as pasture land

1887

George Atkins moved into South Amherst and started a dairy farm and apple orchard

1892

Lead arsenate was introduced as a pesticide in Massachusetts, most commonly in apple orchards, and was later banned in 1988

1962

Atkins Farm Country Market opened 1965 Hampshire College was founded 1991 Applewood Retirement Community was formed

1994 Orchard Arboretum was established

1997

2002

Eric Carle museum was founded in the village 2016 Hitchcock Center for the Environment moved into the village, obtaining the Living Building Certification in 2019 2018 R.W. Kern Center was certified as a Living Building

Yiddish Book Center moved into the village 2021 Kestrel Land Trust moved into the village

Stakeholder outreach was conducted to verify goals, identify additional goals, and investigate challenges related to meeting goals. This qualitative analysis is critical because it provides context for the human experience of this place. This section describes the stakeholders who were involved, methodology, and a synthesis of what was heard.

The identification of whom to engage with was an evolving process throughout the project. While a geographic focus area of a two-mile radius was used, engagement efforts were concentrated within the more dense Village Center, where Bay Road meets West Street/Route 116. The Conway team first met with the institutions in the core group initiating this project, and then reached out to other establishments in the area. As the team’s understanding of the actors progressed, further outreach efforts were made through the stakeholders’ network. This newly connected network of interested stakeholders will continue to be important for the future development of the project to build

A list of identified stakeholders is shown in the table on the right, along with an indication of whether engagement was conducted. The Conway team was not able to engage with all stakeholders, but recommends including them and those who are yet to be identified in the planning processes moving forward.

The forms of engagement included online zoom meetings, in-person meetings, and walking/driving tours.

Core group meetings: Three meetings were held with the stakeholders who initiated this project—Town of Amherst, Hampshire College, the Hitchcock Center for the Environment, Conservation Works, and Kestrel Land Trust.

• January 14, 2025: discussion of goals

• February 6, 2025: discussion of existing and desired physical/cultural/ecological connections

• March 11, 2025: discussion of potential recommendations

Individual stakeholder meetings : Additional conversations were held with groups or individuals from other organizations and communities. A summary of the detailed list of engagement is included in the Appendix. The discussion topics included:

• existing barriers in physical infrastructure

• connection needs and desires

• existing and potentially related projects/ plans

• connection with the land

• interaction within and amongst communities in the focus area

• vision and what are seen as potential assets and constraints Stakeholders involved in these meetings included Atkins Farms Country Market, Yiddish Book Center, New England Mountain Bike Association, Friends of Orchard Arboretum, Mass Department of Conservation and Recreation, residents of Upper Orchard community and Friends of Orchard Arboretum/residents of Applewood retirement community.

• Conservation Works

• Town of Amherst

» Conservation

• Hampshire College

» Facility/Operation Staff

» Farm Staff

» Students (Hampfest)

» Outdoor Programs, Recreation and Athletics (OPRA)

» Justice, Equity and Anti-Racism

• Hitchcock Center for the Environment

» Director

» Facility Manager and Instructor

• Kestrel Land Trust

• Yiddish Book Center

• Atkins Farms Country Market

• New England Mountain Bike Association (NEMBA)

• Friends of Orchard Arboretum

• Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR)

• Residents of Upper Orchard community

• Residents of Applewood Retirement Living

• Eric Carle Museum

• Bay Road Tennis Club and MultiSport Center

• Hampshire College

» Accessibility Resources and Services

» Art Gallery

» Early Learning Center

• Town of Amherst

» Planning

• Town of Hadley

• Friends of Earl’s Trails

• Five College Consortium

• Museum10 Consortium

• PVTA

• Norwottuck Fish and Game

• John S. Lane & Son Inc.

• Other Education Institutions/Schools in the area

• Other community organizations

• Indigenous Community

• Farmers and other land owners in the area

• Residents of neighborhoods north of Hampshire College

• Residents of neighborhoods north of Hickory Ridge Conservation Area

• Residents of the low-density development communities along Bay Road, Middle Street and S. East Street

• Residents of Vista Terrace neighborhood

• Residents of Hampshire Village

• Other community groups in the area

• Commuters from Belchertown

• Visitors to the area

Tabling and canvassing at a student fair (Hampfest, Feb 1, 2025): Recognizing Hampshire College as a large entity (with approximately 800 students along with staff) and acknowledging the importance of students’ perspectives, the Conway team set up a table and engaged in conversations and planned activities with fair attendees.

People like being in this area, and one thing that was repeatedly mentioned by interviewed stakeholders is how beautiful it is. The viewsheds of the Mount Holyoke Range, the Pelham Hills, and the farmlands are enjoyable and calming to behold.

However, there is also general consensus regarding the barriers posed by busy traffic and the lack of crosswalks, and a desire for continuous, accessible, pedestrian-friendly infrastructure in the area. The configuration of roads encircling retail operations isolates them and makes them only safely accessible from a vehicle. In addition, due to the lack of amenities appropriate for residents’ needs (such as healthcare, banking, more grocery and entertainment options) and the lack of reliable modes of alternative transportation, there is heavy reliance on personal vehicles. For an area whose predominant demographic groups are seniors and students, this poses a challenge to both, who might not be able to drive or do not have access to cars. The lack of alternative transportation options and the disjointed nature of current pedestrian infrastructure heightens a sense of confinement and isolation for those with limited resources, and greatly reduces the sense of independence, wellbeing, and connection to the area.

Based on observations and conversations, the social interactions and information sharing between the various institutions appear to be limited by the physical landscape and the siloed nature of their operations. The concept of a cultural village at Hampshire College initiated the recruitment of cultural institutions such as the Yiddish Book Center, Eric Carle Museum, and the Hitchcock Center. However, because they are spread out and there is no intentional pedestrian connection between them, the concept of a cultural village is not felt in the physical experience by visitors. This disconnection creates a sense that each institution exists independently from the others. Aside from semiregular directors meetings and occasional crossprogramming, there are limited collaboration efforts between them.

With the separate efforts, there is little concept of geographical associations among the institutions to visitors. For example, visitors to one of the institutions may not be aware that there are other institu-

tions and establishments within walking distance. With the lack of collective presence, this area is seen as a one time, one venue location. This is amplified from the visitors’ or passerby’s perspective when arriving at the focus area. There is no easy way to be informed of locations or programming in the area. After the visitors have made the effort to come to the area, they may still only be aware of the singular institution they visited. The sentiment of “unless one is in the know, one could not have known,” is common even to local residents.

There is the common goal to increase visitation among all institutions and establishments, and general interest was expressed for physical connections and collaboration. While each institution and establishment is individual and unique, there is collective potential for an enriched experience that each on its own could not provide. Collaboration could attract more visitors and reach more diverse audiences.

Culture is formed and shared by people in a place, and evolves over time. There is no one culture that could represent all persons. Through the community engagement process, it became apparent that cultural connectivity here is not to establish one culture, or one theme for culture, but to create the conditions where the various cultures could interact and connect. This could be facilitated through a common place and platform where all people could connect. The land could thus be a commonality for the diversity of people and the cultures they each hold. In addition to physical infrastructure, events that could encourage the interaction and infusion of cultures and communities are recommended to create cultural connection.

For this area to be a well-connected and thriving Village Center, strong physical and cultural connections are needed, requiring the willing participation and engagement of each individual, institution, establishment, and organizations. It takes a village to build connections. The diversity of cultures and communities that intersects in this area is a strength that could be leaned on. Continuing engagement to explore ways to work together would be crucial to realize the vision.

Below is a brief summary of what was learned through the engagement process.

• Proximity to the Mount Holyoke Range

• The ability to feel close to nature without venturing into the woods

• Lots of options for taking a walk, either hiking on trails or taking a stroll in the Hampshire College campus

• Well-known mountain biking trails that serve a range of ability levels and are family-friendly

• Easy car commute to/from surrounding towns

• Concentration of cultural institutions and offerings in close proximity

• Rich local history

• Friendly and supportive communities

• Each institution and community is well-established and well-known in their part of the world, with long standing relationships and network.

• Wealth of knowledge and expertise in the communities

• Hampshire College has an engaged student body with focus on interdisciplinary and handson approach. The campus itself is a living classroom for projects and learning.

• Active and engaged retirement communities within the Village Center

• Various “Friends-of” communities with experience of volunteer organization and collaboration

• Local residents feel the need to use cars to travel to establishments within the Village Center.

• Lack of safe road crossings in key areas

• Lack of amenities, restaurants and indoor entertainment options in the focus area

• Road conditions are not safe for biking

• Limited bus route reach

• Bus schedule difficult for appointments, classes or employment

• Visitors to the institutions usually arrive by car

• Parking is an issue for trail access.

• Some trails are not well-marked and could be confusing.

• Wayfinding is an issue.

• There are limited ADA paths within the Village Center, and not all are maintained in winter.

• There is a potential safety issue between different trail uses.

• Sometimes it feels isolated living in the area

• Lack of local publicity and engagement

• Uncertain how to collaborate and share maintenance responsibilities across communities and institutions

• Lack of individual (personal and institutional) capacity for projects or initiatives

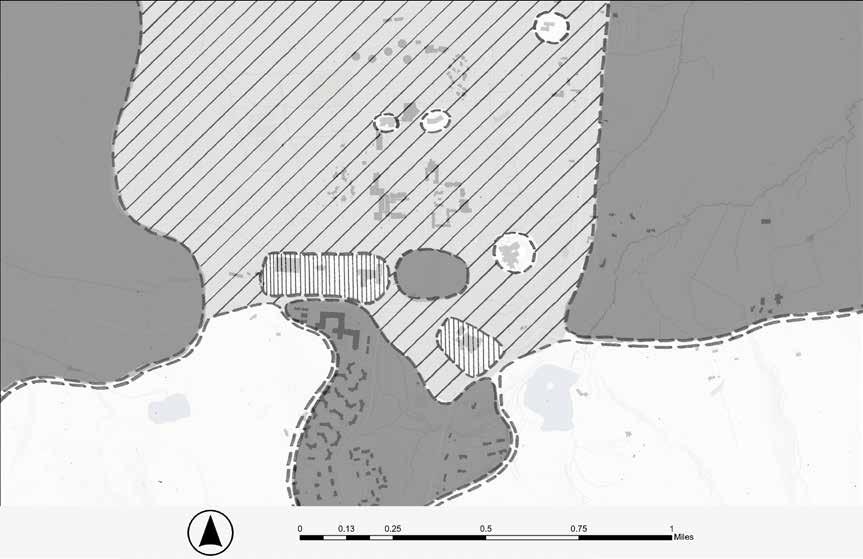

Presently conserved lands are overlain with Biomap Core data to identify ecosystem types deemed critical for maintaining non-human habitat. These ecosystems are considered critical due to how intact they are. Intact areas’ functions have not been detrimentally impacted by human activity. The analysis reveals that despite the abundant natural features that humans experience, extensive fragmentation has occurred in multiple realms.

Much of what remains intact is protected, though key gaps can be observed. Route 116, which runs north-south over the Mount Holyoke Range, divides critical forest and rare species ecosystems. Aquatic habitat to the east of West Street, which runs north-south from Amherst Town Center to the focus area, is divided by the road and much of this ecosystem is on unprotected land. Two vernal pools on the Hampshire College campus are also divided by road infrastructure and buildings. At a high level, Biomap data can be used to identify areas that should be prioritized when considering future restoration, conservation, or development. Connectivity here is vital for maintaining and supporting non-human populations. Reading from landscape patches (micro) to wildlife corridors (macro) can also be done with this data.

To understand how human activities influence plants and wildlife, maintaining consistent demographic and movement data of these populations is necessary. The Mount Holyoke Range and connection to the Connecticut River and Lawrence Swamp should especially be prioritized in monitoring efforts due to the critical status of these areas as designated by the state.

The map below is based on the land use information from MassMapper (2005/2016). The lighter green represents land that is used for agriculture purposes, be it for crops, pastures, orchards or nursery production. The darker green areas are a combination of forests, brushlands, or wildlife habitat. The hatched areas indicate land under permanent protection either for agricultural or ecological conservation. As seen in the map, most of the land within the focus area is under conservation, which preserves the character of the area and supports important ecological and socioeconomic functions.

In ecological conservation areas, priority is given to wildlife needs and the preservation of natural heritage. Human trails or uses in these areas need to be particularly intentional and orchestrated to find a balance between an invitation to engage with the land and prevention of the potential negative impact human presence might have on wildlife habitat.

In agricultural areas, priority is given to agricultural operations and the systems required for farms’ viability and sustainability, economically and environmentally. This is particularly important with the impact of changing climate and markets (Rainford, 2010). Much of the agricultural land also include dwellings, where needs for privacy and amenities are important. Connections to employees, markets/consumers, suppliers, and ecosystem services, and sensitivities to the various land “users”, human and non-human, should be considered.

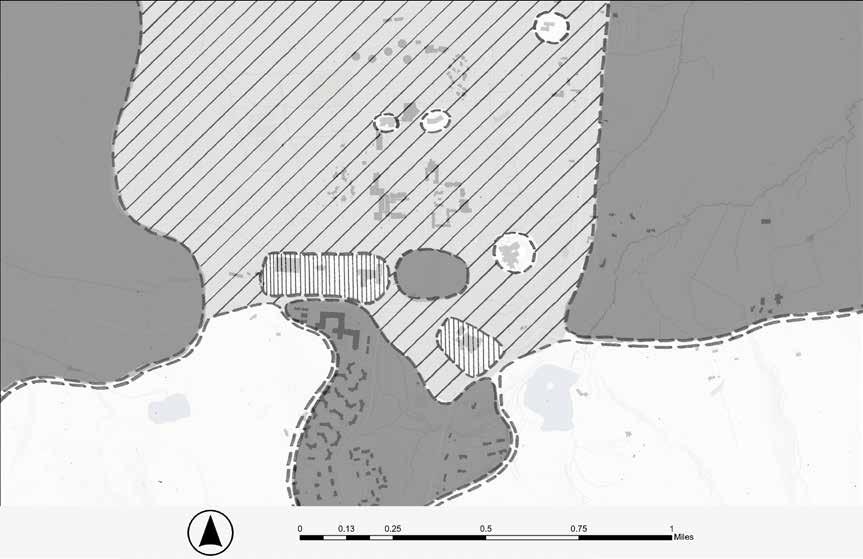

As seen in the land use map on the right, within the focus area, dense residential uses (orange) are distributed along West Street on the north-south axis and span west towards South Maple Street. Though desig nated as institutional land use, Hampshire College has dense student residences within its campus. Low and very low density resi dential land use spreads along South East Road, Middle Street, and Bay Road.

There is limited commercial and industrial land use within the focus area. Community members report that most employees for the commercial and institutional operations do not live locally. Heavy equipment and truck transport may still be frequent in the area due to limited alternative routes across the Mount Holyoke Range. The closest major concentration of commercial land use is in Hadley, along Route 9, and Amherst Town Center.

The spread of residential land use and lim ited commercial activity means most resi dents need to travel out of the focus area to attend to work and other necessities, reflect ing the heavy reliance on cars in the 2020 census data where 42% of Amherst residents drive alone to work. In addition, more than 50% of residents commute less than 20 min utes to work, suggesting there are potential benefits in increasing local public and alter native transportation options.

In addition to contributing to long and beau tiful viewsheds, the large percentage of agriculture land use close to residential areas may increase the opportunities to access local produce, support local farms and nurture synergistic wellbeing.

The extensive conserved lands are a strong asset and offer diverse opportunities. When exploring potential trail routes, it may be important to consider conservation restrictions as well as the permanence of the route if the land is not currently conserved.

One way to anticipate how land use patterns may change in the future is to see what potential future development is allowed by zoning. The current zoning plan for the focus area reflects similar patterns to existing land use. As mentioned previously, a large percentage of the land in the focus area is under permanent protection for either agricultural or ecological conservation, which leaves limited options for potential development. Of the remaining areas, low-density residential zoning is the predominant plan, with small pockets of Village Center Business zoning at South Amherst and Atkins Corner Village Centers.

The hatched parcels in the land use map on the right are categorized as developable or potentially developable vacant land in the 2016 land use data from MassMapper, which is a small percentage of land area in the focus area and relatively scattered. The limited options heighten

the need to look at these parcels strategically and creatively to meet potential future needs.

A potential two-parcel mixed-use development along Bay Road and West Street/Route 116, adjacent to Atkins Farms Country Market, is currently under review with the Town (shown in red in the map on the right). The prospect of mixed use form is important. As noted previously, there is a need for additional complementary amenities in the area. This also aligns with the Town of Amherst Master Plan priority of localizing the economy.

As the current land use trend will likely continue to dominate in the near future, improving infrastructure to support multimodal transportation options and intentionally encouraging a mixeduse overlay in existing and future development would help to increase resilience of the focus area and reduce reliance on motor vehicles.

Feedback from the community indicated that there is a lack of amenities in the area. A preliminary inventory includes:

• Hospitals, health services, and pharmacies

• Groceries and banks

• Schools and childcare centers

The orange shade in the map below indicates where residential areas are and the icons show where various services and amenities are located. As seen in the map, only a very small subset of services and amenities is present within the focus area or close to residences. Most of the services and amenities are located in Amherst Town Center, along Route 9 in Hadley, and in Northampton. Currently, there are limited connection options to reach those areas (e.g. bus schedule doesn’t align with health appointments; no bike or sidewalk network connects the focus area to them). In addition to establishing multi-modal connections to those areas, expanding the range of services and amenities within the focus area could reduce travel needs, increase options, and enhance the livability of

Points of Interest

Although the focus area is surrounded by low-density development, the Village Center has a concentration of “neighbors” within relatively walkable distance (approximately 0.5 to 1 miles), as shown in the map above. This proximity makes it possible to arrive or start at any of the locations in the Village Center, either via bus, bike or car, and still be able to travel to other establishments as a pedestrian where the infrastructure allows. This is an asset both for local residents and visitors, and can potentially reduce localized vehicle traffic. It suggests that improvements to pedestrianfriendly infrastructure within the Village Center may directly encourage pedestrian use. It also highlights the benefits and potential of additional amenities and points of interest within the Village Center. The types of infrastructure currently existing include sidewalks, paved and unpaved pedestrian paths, and shared roadways in low-volume and low-speed areas with notable gaps further discussed in the following sections.

Public spaces are foundational within a community. They provide a free, accessible, and welcoming place for people to use individually as well as facilitate interaction and the development of strong social relationships amongst residents and visitors alike. In most towns there is at least one space serving this function. Examples include public parks, plazas, beaches, and playgrounds.

Public space is where connection and culture arise within a community. As spaces that are equitably accessible, they allow for interactions and connections that are not possible within other realms of social culture, such as members-only clubs or pay-to-play activities.

Within the Village Center there are very few spaces that are distinctly public or that provide public amenities such as restrooms, water fountains, seating, cover from the elements, and information about the surrounding area. The map below shows the distribution of private, public, and semipublic space in the Village Center. The table on the following page shows what basic public amenities are provided by the existing institutions within the Village Center.

The public is welcome in many semi-private locations that offer some amenities, such as Atkins Farms Country Market, Hampshire College, and the Hitchcock Center, but the accessibility of amenities in those locations is constrained by the perception of private vs. public space and operating hours. There is currently no centrally-located institution that can serve the function of a public space and provide the public amenities that visitors may need.

Amherst Town Center is situated around a large public space that provides open green space, seating, and parking. Public restrooms are available at the Town Hall, directly adjacent. The visitor experience here is welcoming and invites people to pause and interact with the town surroundings, beyond just hopping between businesses or running errands.

The scale of human experience is that of direct sense. Embodied physical, psychological and emotional realities arise through interaction with the built and natural environment as well as interactions with other entities made possible (or impossible) in these settings. Given the range of the focus area, it was not possible to conduct a thorough analysis. However, elements deemed central to determining the quality of human experience within the focus area were considered. Taking these elements into account can help the town magnify the immediate experience and perception of the Village Center and the local landscape.

Weather and ambient temperature are major factors in human comfort.

Urban Heat Islands (UHI) in the area are concentrated at parking lots. Pathways next to solar arrays as well as roadways may be uncomfortable if without shade trees. Certain populations such as seniors and children are especially vulnerable to the ill effects of exposure to high temperatures.

The perception of safety in an area may deter or encourage use, depending on the individual. Some of the elements that could influence this are lighting and access to help.

Most of the parking lots within the area and paths on Hampshire campus provide lighting, though the main roads do not.

Some areas within Hampshire College have blue light emergency response technology.

Sight, sound, and ambience of a space could enhance or ruin an experience.

The most prominent viewshed feature within the focus area is the Mount Holyoke Range. Traffic along Bay Road and West Street/Route 116 is a source of noise that may travel. Sounds of nature are abundant further away from the roads within the focus area.

The human experience of navigating through a landscape is influenced by many factors, some obvious and others extremely subtle. Intentional wayfinding cues can help guide people through this navigation experience. These cues range from directional markings, signs, color, material and texture, auditory, visual, tactile, and more. Within the focus area, signs are the dominant cue. Types of wayfinding signs include: Identification, Directional, Orientation, and Regulatory.

Signs within the focus area include typical directional and regulatory road/trail signs, identification signs at individual businesses and institutions, and orientation signs at some of the recreational trailheads. While signs marking destinations are frequent and visible in this area, directional and orientation cues to guide people between locations and trail systems are lacking. Since many of these destinations are not easily visible from the road, visitors may pass through the area without realizing what lies just out of sight.

Directional signs around the double rotaries display road names to guide vehicles through the intersection. What is missing in this area are directional signs to guide people to the institutions and destinations nearby.

Orientation signs in the form of kiosks at several of the trailheads provide ample information to help visitors navigate trail networks. Within the Village Center however, similar signage to guide pedestrians between institutions, businesses, and recreational access points is lacking.

Signs throughout the focus area display a diverse selection of design styles. Construction material, size, and color vary greatly depending on which organization the sign represents. While this gives unique character, it does not help to form a common sense of place. In some areas it even creates points of confusion where multiple sign styles are present in one location without clear hierarchy.

Digital wayfinding through trail apps provides another way for people to navigate the area, but the information available is not comprehensive or fully accurate. Many of the platforms rely on crowdsourced information and, according to conversations with DCR and other organizations maintaining trail networks within the focus area, it can be difficult to ensure that the information found on the apps is up to date, accurate and consistent with official plans.

To understand how people move around this landscape and to identify barriers to connectivity, existing physical infrastructure was mapped and analyzed. Roads represent the dominant network of connectivity. The focus area is dissected by two main routes, Bay Road and West Street/Route 116, which cross at the double rotaries. Bay Road was part of an Indigenous trail, and it continues to provide an east-west connection on the north side of the Mount Holyoke Range between Northampton and Belchertown. West Street/Route 116 runs through the Mount Holyoke Range, providing a northsouth connection between Amherst and South Hadley. Through this network of roads, the focus area is well connected to surrounding towns.

Multiple modes of transportation operate along these road networks, including vehicle, bike, and pedestrian traffic. Many of these roads have narrow shoulders, and some sections are rough to traverse for pedestrians, bikes, and vehicles alike. There are also areas of potential conflict between vehicle speeds and bikes/pedestrians, places where vehicles are moving at speeds that could endanger other users on the road. Some alternatives may need to be considered for safer connections, whether through pedestrian and bike routes that are separate from vehicle lanes, traffic calming measures, adjustments to speed limits, etc.

Roads create an extensive network of impervious surface and have a significant impact on the surrounding landscape. While they function well to connect people between locations, they can be disruptive to wildlife, cause habitat fragmentation, and increase runoff and the effects of stormwater (Forman and Alexander, 1998). The region at the northern extent of the focus area has potential for flood impacts from the Fort River, as illustrated by the FEMA floodplain layer shown on the map to the right. When suggesting new infrastructure that increases the coverage of impervious surfaces in the area, such as trails or sidewalk extensions, it will be important to consider the potential effects of runoff and stormwater and to implement appropriate mitigation techniques where needed.

MOUNT HOLYOKE RANGE

Operating on top of the road infrastructure is the public transit bus network managed by the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority (PVTA). The two main routes (PVTA 36 & 38) that serve this area provide north-south connections between Amherst Town Center, the focus area, and South Hadley. They are structured to serve connections between the five colleges and operate on the academic calendar. This means there are scheduling gaps when the colleges are not in session. Smaller buses run the route east-west between the focus area and Northampton (PVTA 39). User interviews revealed these buses are

not always reliable, arriving outside of scheduled stop times and sometimes reaching rider capacity. There is also no consistent route from the focus area to the commercial business district in Hadley, which has been identified through stakeholder engagement as a key destination for amenities. Route 39 operates between the focus area and the Hadley business district only on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. To fully support the connectivity needs of the community, these routes and schedules may need to be more fully evaluated and adjusted.

Bus stops in the focus area exist in multiple locations and in several different forms. Some have covered seating and bike parking, some have just seating, some are a road pull-off, and some are just a marked location along the road with no existing infrastructure.

While direct recommendations for the bus network are outside the scope of this project, as PVTA is separate from the jurisdiction of the Town of Amherst and was not directly involved in this planning project, some considerations for the future did arise based on conversations with stakeholders, analysis, and observations. A PVTA network analysis may be beneficial to more fully understand the needs of regional communities and how routes and infrastructure could be adjusted to better meet them.

• A comprehensive network map does not exist currently, but could help riders navigate the public transportation system.

• The section of Route 39 from the focus area to the Hadley business district could be piloted as a regular part of the route rather than occasional.

• Standards for bus stop shelters could be adopted to assure that human comfort and safety is met.

• Buses could be outfitted with bike-carrying capacity to allow for use by cyclists.

Infrastructure for bicyclists and pedestrians (not on recreational hiking trails), consists of the Norwottuck Rail Trail and town sidewalks. The rail trail runs east-west and the main shared-use sidewalk along West Street runs north-south, with the two networks intersecting in Amherst Town Center. While these networks do connect and function well for pedestrian use, they do not function as a complete bike system because of several safety considerations. The sidewalk along West Street is too narrow in most places to allow for safe shared use between bicycles and pedestrians. It is also uneven in areas and intersects with many driveways, posing safety

hazards to users. A safer bike connection is needed from the focus area to the Norwottuck Rail Trail and Amherst Town Center. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) identifies this area and suggested it for a potential bike lane in its Priority Trails Network Vision Map. The Vision Map looks at existing bike infrastructure across the state, identifies current gaps, and suggests how to address those gaps to create a more comprehensive bike network.

While the Norwottuck Rail Trail and town sidewalks create a fairly comprehensive network for pedestrians, there are still some gaps.

B

C

D E F G

There are areas within the Village Center that get regular use despite the lack of supporting pedestrian infrastructure (sidewalks and crosswalks). Conversations with stakeholders repeatedly emphasized these areas as priority connections to address. These include:

A| no sidewalk along the main entrance road to Hampshire College

B| no sidewalk from Hampshire College entrance road to Hadley Reservoir trailhead crossing

C| no crosswalk or signage at the crossing to the Hadley Reservoir trailhead

D| no sidewalk along the section between Applewood Apartments and Atkins Market (grass path)

E| no crosswalk or signage at the crossing from Hampshire College Campus to Atkins Market

F| no crosswalk or signage at the crossing to the Trolley Line Trail

G| no safe connection to the Sweet Alice Conservation Area (sidewalk or crosswalk)

The focus area has an extensive network of pedestrian trails. This network is relatively accessible via car, but parking is limited in some spots and non-vehicular access is hindered by network gaps and unsafe road crossings in multiple places. Some sections are also in need of maintenance and improved signage for safe use. While snow cover and time constraints limited the ability for a detailed trail condition analysis as part of this planning project, conversations with stakeholders and ground truthing provided a general overview of current trail conditions.

A| The trails through the Mount Holyoke Range and connected areas make up most of the pedestrian trail network within the focus area. These trails include ones maintained by DCR in Mount Holyoke State Park as well as conservation areas owned by the towns of Amherst and Hadley (Sweet Alice Conservation Area and The Hadley Reservoir). According to park managers at Mount Holyoke State Park, this extensive network is currently exceeding recommended trail density. DCR plans to simplify the network to reduce habitat fragmentation impact and maintenance needs.

B| The trails through the Hampshire College woods provide a walking experience for students, neighbors, and visitors. These trails are maintained by Hampshire staff and students and are utilized for classes. There is a lack of adequate signage throughout this network to help guide visitors unfamiliar with the landscape. Sections of these trails are also in need of maintenance to address erosion, debris, and stream crossings. Some of these trails also overlap with active farming on the Hampshire Farm, and the farm managers have expressed concerns about safety where pedestrians cross paths with animals and machinery.

C| The Orchard Arboretum is located behind the Applewood Apartments and maintained by the Friends of the Arboretum. The trails through the arboretum are ADA compliant and offer many benches along the way for visitors to pause and enjoy the splendid display of plants. The arboretum gets frequent use from residents of Applewood Apartments and Upper Orchard, both retirement communities. However, there is no signage along Bay Road to direct new visitors to this destination.

D| Hickory Ridge Conservation Area is a newer acquisition of the Town of Amherst, with plans to be protected under conservation restriction and a trail system still in development. The planned trails for this area will meet Forest Service accessibility standards. The conservation area is situated between two residential neighborhoods, with the Fort River running through the middle of the property. This area has been identified through conversations with Town representatives as a possible connection piece within a larger potential northsouth trail corridor.

Earl’s Trails is an extensive mountain bike trail network on the north side of the Mount Holyoke Range. It crosses over land owned by five different organizations/municipalities: DCR, Town of Hadley, Town of Amherst, Amherst College, and Hampshire College. The trails are maintained by volunteers from Friends of Earls, local representation of New England Mountain Bike Association (NEMBA).

This trail network is accessed from three points within the focus area: trailheads at Chmura Road, Hadley Reservoir, and Military Road (across Route 116 from the Notch Visitor Center). NEMBA is currently working with the Town of Hadley to develop a thirty-car parking lot at the Hadley Reservoir trailhead and establish this as the primary access point.

According to NEMBA, the trail network is currently exceeding desired density, with erosion issues and potential habitat fragmentation impacts. The organization is working on a network master plan to simplify the trail system. With these trails overlapping and intersecting pedestrian trails in some places, NEMBA and DCR have expressed challenges with shareduse safety and clear signage.

Representatives from NEMBA have also expressed a desire to improve the safety of the connection from the Hadley Reservoir trailhead to the Village Center. The route currently used traverses Bay Road which they find unsafe, especially for families biking with children.

A well-connected community has many connections within its immediate neighborhood and is also connected more broadly to the region. There are several regional trail systems that intersect the focus area, or exist just outside the two-mile zone. Three of these regional trails are of particular interest to this project.

The Norwottuck Rail Trail lies just to the north of the focus area and runs east-west, connecting to downtown Northampton.

The New England Trail (Metacomet and Monadnock) is a 235-mile longdistance hiking trail that runs eastwest along the ridge of the Mount Holyoke Range.

The Ken Cuddeback (K.C.) trail runs north-south, starting in Amherst at Wentworth Farm and ending at Rattlesnake Knob in the Mount Holyoke Range.

The Norwottuck Rail Trail is connected to the Village Center via town sidewalks. The K.C. Trail and the New England Trail can be accessed from the Village Center via connecting pedestrian trails that start at the Sweet Alice and Hadley Reservoir trailheads.

The focus area already has an extensive network of trail systems, with the potential to function as a unified system with the addition or improvement of specific connections. More comprehensive connectivity is desired, as heard through stakeholder engagement. However, it is important to consider the impacts of trail networks on habitat and wildlife. Network extensions should overlap with existing infrastructure wherever possible and new connections should be planned to have minimal impact and avoid increased fragmentation of habitat.

The map on the right shows the combined existing physical infrastructure network of sidewalks, bike paths, pedestrian trails, mountain biking trails, and trailhead access points. The simplified map below highlights areas of the Village Center, residential communities, and open space and marks some of the key stakeholder-desired connections.

Stakeholder-desired connections within the focus area include:

A| Connections within the Village Center across and along Bay Road

B| Connecting between residential and open space areas

C| Continuing the north-south connection all the way to the Norwottuck Rail Trail, Amherst Town Center, and Hadley commercial district

D| Connecting the Village Center with the trail network to the south

Observed barriers to connectivity within the focus area are shown by jagged lines in the diagram to the left and include:

• Transitions between land use types and land ownership

• Physical barriers like the solar development project at Hickory Ridge

• Safety concerns at road crossings that currently lack pedestrian safety infrastructure like crosswalks and signage

To realize a Village Center that is well connected locally and regionally and accessible by multiple modes of transportation, a continuous network of infrastructure is needed. Diversifying routes to include immersive experiences within the landscape would enhance connection to place. Some of these proposed connections would cross private property and may necessitate a trail easement.

A| Connecting the Village Center to the Norwottuck Rail Trail has the potential to significantly increase access to and from the area for both commuter and recreational cyclists and pedestrians. This would also link the Village Center with the Hadley commercial district and its amenities. The proposed pathway assumes that the Town’s current plans for the Hickory Ridge Conservation area will be implemented.

B| It is recommended that the multi-use sidewalk that runs along West Street from the Village Center to Amherst Town Center is either widened or separate bike infrastructure added to create accessible conditions. This could take various forms depending on the context.

C| Another key connection that would open the Village Center to broader regional connections is the Trolley Line Trail. It could provide an access point to the Mount Holyoke Range for recreational cyclists and hikers. It could also be the starting point for a vital connection to Mount Holyoke College and towns to the south for commuter purposes. This creates infrastructure for people to travel without sole reliance on cars.

D| The addition of a multi-use pathway from West Street/Route 116 to Bay Road could create a connection to the Sweet Alice trailhead. This would also work around the constraint posed by a culvert across from the Kestrel Land Trust office that makes adding a sidewalk there challenging.

E| Additional routes (especially east-west) creating nested loops within the broader network would increase the efficacy of the entire system. This may necessitate collaboration with neighboring towns. Collectively, these connections have the potential to create a functional multi-modal network that acts as resilient infrastructure, reducing reliance on motor vehicles.

Hampshire College Trails

Reservoir Trails

Arboretum

To realize the Town’s vision of a pedestrian-friendly Village Center, infrastructure needs to support an easily navigable and enjoyable experience for all people. This would require collaboration amongst property owners within the Village Center to connect identified public-facing establishments, residential areas, and trailheads within the Village Center.

• Installing crosswalks ( in the diagram on the left) and sidewalks at key locations identified in the analysis section. (The exact locations of the crosswalks would require further technical input, especially close to the rotaries at West Street and Bay Road.)

• Collaborating with Hampshire College to potentially incorporate the campus accessibility infrastructure plan with the broader Village Center.

• Supporting the development of potential accessible trails in the focus area, such as some trails within the Hampshire College woods, and the pond trail portion of the Sweet Alice trail network.

• Creating an accessible system to include smaller loops, benches or places to rest to consider all ability levels.

• Continuing to implement accessible connections throughout the future development process, particularly with public-facing infrastructure.

Having a combination of looped and spoked multi-use paths that connect to both amenities and outdoor recreation gateways can open up the possibility of using different forms of transportation in the area, for living and play.

Recognizing the potential lengthy process of infrastructure projects, the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) suggests experimenting with interim design strategies that could enable faster project delivery and more flexible and responsive design that could inform more permanent solutions.

Consistency is important to create a coherent interface for pedestrians. Adoption of common design standards for paths within the Village Center and across the focus area is recommended.

For paved paths, the ADA Accessibility Guidelines.

For unpaved paths, the US Forest Services Outdoor Recreation Accessibility Guidelines.

For the low-volume and low-speed sections of roads where pedestrians might need to share with motor vehicles and dedicated sidewalk is not possible, it is recommended to consider using the principles suggested in the US Federal Highway Administration Shared Streets Design Toolbox, such as traffic calming measures, and clear distinction and notification where the streets are shared (Elliott et al, 2017).

“WALKABLE COMMUNITIES ALSO ENCOURAGE SOCIAL INTERACTION, WHICH ENGENDERS A SENSE OF COMMUNITY AND IMPROVES PEOPLE’S MENTAL HEALTH...”

~US EPA “NATIONAL WALKABILITY INDEX”

Establishing public space outdoors solidifies the character of the Village Center as one defined by the landscape. Providing immersive place-based experience enables forms of relationship and hybridization between people, place, material, and earth (Corner, 1997). Some potential sites are highlighted by dashed outlines on the map to the left.

To meet the basic needs of visitors and facilitate a welcoming and enjoyable interaction with the Village Center and the surrounding landscape, public space needs to include a few key features that are free-standing, not restricted to a building that would require staffing. These features do not all need to be contained within a singular outdoor space but should all be present within the Village Center.

• public restrooms

• potable water

• shelter from the elements

• seating

• lighting

• information about the area and navigation cues

• access to parking (car and bike) and public transit (consider including bike share infrastructure)

To preserve the viewshed and rural character of the area, built infrastructure should be minimal and unobtrusive, while still providing the necessary public amenities in a visible and accessible way. There is a potential to replicate some of the design concepts found in the nearby living buildings (the Hitchcock Center and the Kern Center) and to draw on these buildings for examples of appropriate materials and form for this place.

Due to the history of the area, the reality of lead and arsenic contamination needs to be considered, but should not necessarily rule out the potential use of these sites for public space. An approach that centers remediation as a public process generates the opportunity for education and provides a legible, indexical record of the site’s environmental history.

To improve the navigation experience of visitors, signage and wayfinding will need to be addressed. Effective wayfinding infrastructure and signage should enable all people to understand where they are within a landscape and how to get between desired locations with ease. With increased development planned for this Village Center, more signage and wayfinding issues may arise and it may be necessary to conduct a full wayfinding study at some point in the future.

A| Increase orientation signs within the Village Center. (Example from the Hitchcock Center)

B| Increase directional cues within the Village Center. (Example: ground cues)

C| Site signage in a location that is accessible to all, using graphics and symbols rather than text when possible, and incorporate non-visual navigation cues into the landscape. (Example: tactile paving)

D| Incorporate cultural and historical elements into signage. (Example from the Yiddish Book Center)

E| Include interpretive signage that encourages environmental literacy and connection to place. (Example from Hampshire Food Forest)

The process to establish wayfinding signage design standards for the Village Center should be community driven, with engagement opportunities for residents to provide feedback, similar to the process used for the Amherst Town Center wayfinding project. The process may be important to complete prior to the construction of planned development in the area, so that design standards can be ready to implement.

The Town of Amherst initiated a wayfinding signage project in 2015 and began installing some of the resulting signs around Amherst Town Center in 2021. The project was driven by the desire to increase economic development by directing people to the downtown business district, guide visitors to key destinations and landmarks, and reflect the town’s character and establish a strong sense of place. This project drew on public input and the expertise of wayfinding design consultants to establish design standards for Amherst Town Center. (Town of Amherst, 2021)

During this project, it became clear that people assume Atkins Corner means Atkins Farms Country Market and not the Village Center, perhaps due to the fact that the business sits on a corner, or because of its high visibility within the center, or its relatively long standing history in the community. During discussions on branding the Village Center, symbology of the apple came up regularly, unknowingly evoking the human history that resulted in contamination of the land. Further, it does not recognize cultures beyond colonial presence.

It is recommended that instead of relying on these histories, a land-based name is to be explored, one with potential to ground the Village Center in a different relation to place while providing the common ground for a diversity of cultures to connect and flourish. By centering the land and ecologies that define the experiences here, the Town can intentionally usher in a new narrative, one defined by collaborative relationship with the natural world.

As a cultural connectivity project, this document acknowledges the effect that oppression of certain cultural groups has had on social relations in this area.

Equity is a guiding principle of Town efforts. Examining how systemic inequalities can be addressed, effectively ending cycles of violence, is vital to realizing just futures.

One such historic injustice is the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from the land. This might be addressed through engaging in reparative relational work. A multi-faceted approach to the application of conservation easements could be a powerful way of beginning this process.

This could occur by designating conservation land under a Cultural Respect Easement. This type of easement transfers usage rights to a group to grant stewardship while the land owner maintains legal possession.

Currently, non-federally-recognized tribes are not considered as legal entities. A land trust would need to be organized for parcels to be moved into a Cultural Respect Easement.

Beyond the cultural and environmental benefits of restructuring settler-colonial systems, an opportunity is created for the establishment of an ongoing reparative relationship between the Town and Indigenous communities.

“A Cultural Respect Easement is the closest expression of land reparation to Indigenous people achieved without an actual transfer of deed.”

-Ramona Peters (Native Land Conservancy, 2023)

Rinihmu Pulte’irekne is a five-acre site located above Oakland, California, within Joaquin Miller Park. Land management rights have been transferred to The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and The Confederated Villages of Lisjan (an East Bay Ohlone tribe), while the City of Oakland holds official ownership. The cultural conservation easement is an official reserved interest easement, meaning the City holds restricted rights such as allowing the public to visit outside of tribal events, requiring environmental review and rezoning for any new structures, and access in emergencies. The land trust holds the right to use the land for natural resource restoration, cultural practices, public education, and to plan for additional future uses. (Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, 2025)

Connection takes time to build. This is a long-term project, and there are many other competing priorities for the Town, institutions, and individuals. To reduce the pressure on any single entity to carry this work forward and to foster collaboration, a working committee is recommended. With the goal of realizing the collective vision for culture connectivity in the area, the working committee could identify priorities, engage appropriate entities to accomplish the objectives, and facilitate delegation and negotiation of logistics and responsibilities. Depending on the evolution of the vision, this could be a long-standing or project-based committee.

Composition: The working committee could be composed of interested individuals, businesses and institutions who are willing to commit efforts to realize the vision. It is recommended to include representatives from a diversity of stakeholders to help create accountability and a balanced approach. Diversity in composition could also broaden available strengths and resources and discover gaps and opportunities. The current core group and newly connected stakeholders in this project is a good starting point. Public and private invitations could be used to recruit interested parties as appropriate. A sample range of stakeholders to include could be:

• Town of Amherst

• Culture institutions

• Landowners

• Residents, students, and members from marginalized communities

• Community organizations

• Businesses

Size: It could be overwhelming logistically to arrange meetings and be effective with a large number of people. It may be a good idea to keep the size of the committee manageable, usually around ten. If there are more people interested than manageable, a selection process that results in wider representations of stakeholders may be adopted. Sub-working groups with specific tasks and priorities could also be formed to include wider participation, delegate efforts, and achieve goals. Members for the sub-working groups and the committee do not need to overlap but communications between the sub-working groups and the committee should be maintained to facilitate collaboration and encourage collective impact.

Leadership: Leadership of the committee can rotate regularly, but it is important to always have at least one champion to lead the charge and facilitate meetings. Different roles within the committee could also be identified and delegated as appropriate to help balance the workload. In all cases, efforts should be made to transfer knowledge when roles change to ensure smooth transition.

Reflection and Revision: To be responsive to changes and evaluate progress, it is important for the committee to take the time periodically to reflect on how things are going, and adjust accordingly. Every group dynamic is different. How one works best at one time does not necessary apply to all. It is up to the committee to reflect and evolve with their context and their goals.

Learning from Others: Rails-To-Trails Conservancy (RTC) offers many resources on trail building and collaborations, as well as an active peer learning network, the TrailNation Collaborative. It provides tools, support and ways to connect with others working on trail-building projects. The Town of Amherst also has experiences working with communities that the committee could draw from and forge a model that is suitable for them.

It is recognized that it takes the whole village to build connections. Continual public engagement to help form and inform the process and vision is important, especially with communities whose voices are not typically heard or are marginalized. Periodically asking “who’s missing in the conversation?” could be helpful in directing outreach efforts and exploring ways to empower communities. Furthermore, having events that celebrate culture and encourage interactions and opportunities for collaboration could also enhance connections. Starting small is a good way to explore what could work. Doors Open Days are events that are flexible in scale and complexity and they have been successful in bringing people together while highlighting the heritage of a place.

Doors Open Day is a cultural phenomenon that first took place in France in 1984 and has since spread through Europe and North America. The idea is to provide open access to sites with cultural, natural, historical or architecture significance that may or may not be typically accessible to the public to explore and learn about the stories unique to those places. It celebrates the community’s identities, generates awareness and excitement, and builds interest in the heritage of the place. It is free of charge, typically held annually for one or two days, with participations from various sites or organizations. Each individual site is responsible for their own logistics and programming but adheres to collective guidelines such as free access, opening times and promotional message.

SOME EXAMPLES IN NORTH AMERICA ARE:

Doors Open Ontario, Canada: www.doorsopenontario.on.ca

Doors Open Lowell, MA : www.doorsopenlowell.org

No person is an island. Nor is an institution. Nor is a business. We depend on our connections with others and our environment for our wellbeing and survival, individually and collectively. Finding safe and effective ways of getting from A to B is an important starting point to provide the means for forming connections. However, to connect cultures is to connect people, which requires people to slow down and be willing to reach out. It is the hope that this process of examining and envisioning culture connections can initiate collective efforts to intentionally build communities that are genuine and unique to this place, resulting in an enriched, grounded and vibrant Village Center for the benefit of all.

Tuesday January 14, 2025; In person walking tour

Tuesday January 21, 2025; 3-4pm

Tuesday January 28, 11am-12pm

Hampshire College: Steve Roof

In person driving/walking tour Conservation Works: Pete Westover

In person @ Hampshire College Cole Science Center, Rm101

Thursday January 30, 2025; 12:30-2pm; In person @ Amherst Town Center

Thursday, January 30, 2025; 2-2:30pm

In person @ Hitchcock Center

Thursday February 13, 2025; 5:30-6:30pm Zoom

Friday Feb. 14, 2025 9-10am Zoom

Tuesday, Feb 18, 2025; 11-11:30am;

Hampshire College: Steve Roof, James Scanner, Emily Landeck, Charlotte Senders, Jennifer VanWyk, Steve Duffy

Town of Amherst: Erin Jacque

Hitchcock Center for the Environment: Billy Spitzer

Upper Orchard resident: S. Wilson

Friends of Orchard Arboretum/ Applewood Retirement Community residents: E. Davis, J. Brown

In person @ Atkins Farm Country Market Atkins Farm Country Market: Kelly Lannon, Matt Lannon, John Thibbitts

Thursday, Feb 20, 2025; 12-12:30pm Zoom

Thursday, Feb 20, 2025; 1-2pm Zoom

Friday, Feb 21, 2025; 9-10:30am

Friday, Feb 21, 2025; impromptu 30min meeting

In person @ Kestrel Land Trust Office

In person @ Hitchcock Center

Tuesday, Feb 25, 2025; 10:30-11am Zoom

Wed, Feb 26, 2025; 9-10am Zoom

Friday, March 14, 2025; 10-10:30am Zoom

Thursday March 20, 2025; 1-2pm Zoom

Hampshire College: Javiera Benavente

Yiddish Book Center: Susan Bronson

Kestrel Land Trust: Kari Blood, Stuart Watson

Hitchcock Center for the Environment: Barb Gilbert, Monya Relles

New England Mountain Bike Association (NEMBA): Kurt Bahneman

Hampshire College Outdoor Programs, Recreation and Athletics (OPRA): Michelle Lloyd-Dedischew, Eric Nazir

DCR Connecticut River Valley District Manager: Crystal Cormier

DCR Mt. Holyoke Range: Kurt Richards, Alexandra Echandi

Elliott, J, et al. “Accessible Shared Streets: Notable Practices and Considerations for Accommodating Pedestrians with Vision Disabilities.” Bicycle and Pedestrian Program, U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration, www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/ accessible_shared_streets/#design. Accessed 2025.

U.S. Access Board, “Accessibility Standards For Federal Outdoor Developed Areas.” Guide to the ABA Accessibility Standards Chapter 10: Outdoor Developed Areas, May 2014 www.access-board.gov/aba/ guides/chapter-10-outdoor/ . Accessed 2025

U.S. Access Board, ADA Accessibility Guidelines, www.access-board.gov/adaag-1991-2002.html. Accessed 2025.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “National Walkability Index: Methodology and User Guide.” National Walkability Index User Guide and Methodology, www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/documents/national_walkability_index_methodology_and_user_guide_june2021.pdf. Accessed 2025.

U.S. Forest Service, “0623-2801-MTDC: Accessibility Guidebook for Outdoor Recreation and Trails.” T&D Publications, www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm06232801/page09.htm. Accessed 2025.

Moore, Roger L., et al. Organizing Outdoor Volunteers. Appalachian Mountain Club, 1992.

Rails to Trails Conservancy, “Trailnation Collaborative.” 14 Mar. 2025, www.railstotrails.org/trailnation/ collaborative/.

Richardson, Jean. Partnerships In Communities: Reweaving the Fabric of Rural America. Island Press, 2000.

Corner, James, and Alison Bick Hirsch. The Landscape Imagination : Collected Essays of James Corner, 1990-2010. New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2014.

Dittmar, Hank, and Gloria Ohland. The New Transit Town: Best Practices in Transit-Oriented Development. Island Press, 2004.

Forman, Richard T., and Lauren E. Alexander. “Roads and their major ecological effects.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, vol. 29, no. 1, Nov. 1998, pp. 207–231, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev. ecolsys.29.1.207.

Forman, Richard. Towns, Ecology, and the Land. Cambridge University Press, 7 Feb. 2019. Gehl, Jan, and Birgitte Svarre. How to Study Public Life: Methods in Urban Design. Translated by Karen Ann Steenhard, Island Press, 2013.

Hellmund, Paul Cawood, and Daniel Smith. Designing Greenways. 10 July 2006. Native Land Conservancy, “Cultural Respect Easements.” www.nativelandconservancy.org/culturalrespect-easements. Accessed 2025. Sorrells, Kathryn. Intercultural Communication Globalization and Social Justice. Sage, 2013.

The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, “Rinihmu Pulte’irekne (Sequoia Point).” 17 Mar. 2025, sogoreate-landtrust. org/sequoia-point-land-return/.

Wiens, John A, and Michael R Moss. Issues and Perspectives in Landscape Ecology. Cambridge ; New York, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Amherst Historical Society, “The Dairy Industry and Amherst’s Past.” amhersthistory.org/the-dairyindustry-and-amhersts-past/. Accessed 2025. Atkins Farms Country Market, “About Us.” atkinsfarms. com/about-us/. Accessed 2025.

Conservation Works, “About.” www.conservationworksllc.com/about/. Accessed 2025. Eiring, Zintkala. “The Norwottuck People of the Connecticut River Watershed.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region, 22 Nov. 2017, usfwsnortheast.wordpress.com/2017/11/22/the-norwottuckpeople-of-the-connecticut-river-watershed/ . Accessed 2025.

Elliott, Marjorie Atkins, and William H. Atkins. North of Norwottuck: A Sampler of South Amherst, Mass. F. Irvine and Marjorie Elliott, 1985. https://archive.org/details/northofnorwottuc00elli/page/n7/ mode/2up

Eric Carle Museum, “About Eric Carle.” carlemuseum.org/about/about-eric-carle. Accessed 2025.

Hampshire College, “Enchiridion to Hampshire History.” www.hampshire.edu/library/archives-and-special-collections/enchiridion-hampshire-history. Accessed 2025.

Hitchcock Center for the Environment, “Our History.” www.hitchcockcenter.org/about-us/our-history/. Accessed 2025.

Hood, Ernie. “The Apple Bites Back: Claiming Old Orchards for Residential Development.” Environmental Health Perspectives vol. 114,8 (2006): A470-6. doi:10.1289/ehp.114-a470 https://pmc. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1551991/Town of Amherst, “History.” History | Amherst, MA - Official Website, www.amherstma.gov/229/History. Accessed 2025.

Kestrel Land Trust, “Our History.” 4 Jan. 2022, www.kestreltrust.org/about/history/.