A Food Access Project for the Springfield Food Policy Council

Aspen Anderson / Kerry Morgan / Daniella Portal The Conway School Winter 2024

Aspen Anderson / Kerry Morgan / Daniella Portal The Conway School Winter 2024

A Food Access Project for the Springfield Food Policy Council

Winter 2024

Aspen Anderson / Kerry Morgan / Daniella PortalWe would like to thank the many people who helped push this project forward. We extend a special thanks to the Springfield Food Policy Council for funding this project and to our core team members, Liz O’Gilvie, Catherine Sands, Becky Basch, and Benjamin Bland, for their guidance and sharing of knowledge. We also thank the farmers, advocates, planners, city officials, and other individuals who shared their time and insights throughout the project. A special thanks to Jacob Dolinger and Jason Mann for providing crucial GIS data as well.

Lastly, a thank you to our faculty, staff, and peers at the Conway School for their continued support, inspiration, and teachings.

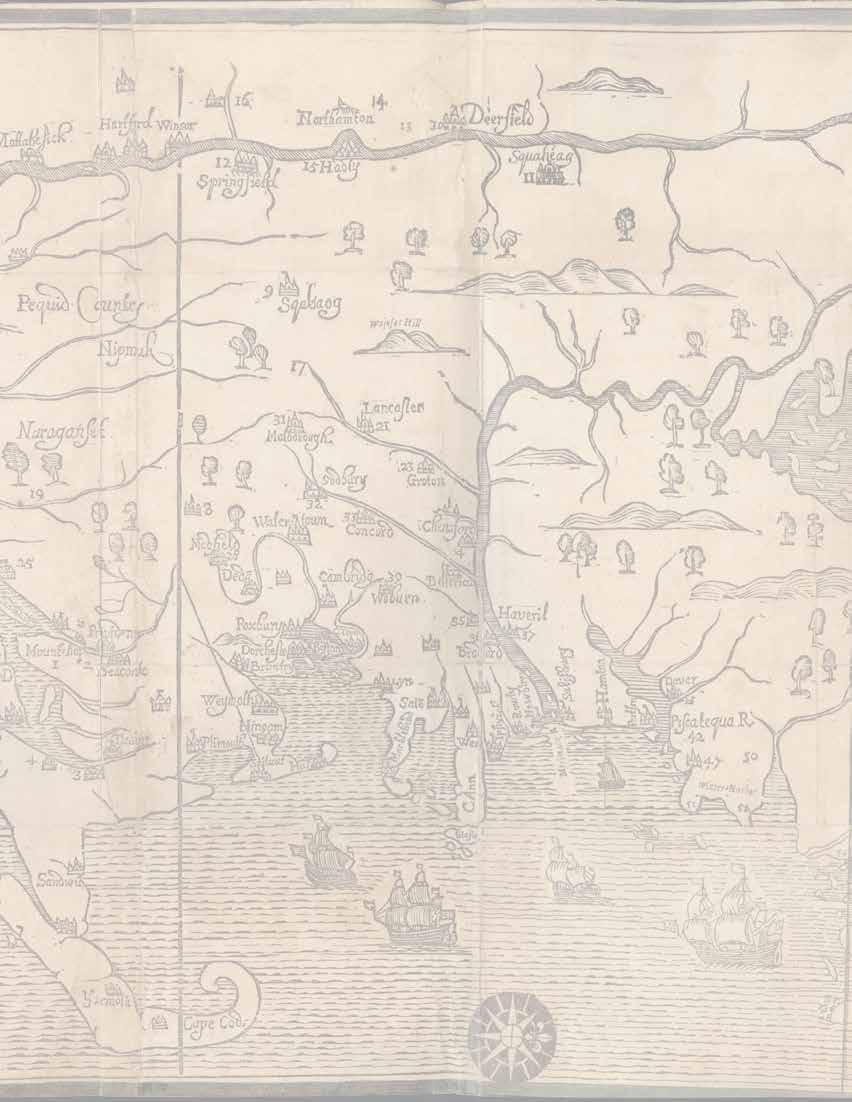

We acknowledge that the city of Springfield is on Indigenous land, known to the original Algonkian Indian (Native American/Indigenous) inhabitants as “Agawam,” or “Akawaham.” The Indigenous name for this place is a locative term that roughly translates to “low-lying marshy lands,” describing a large region along both sides of the Kwinitekw (now called the Connecticut River) from present-day Enfield, Connecticut to the Holyoke Range. For at least 10,000 years, since the last era of glaciation, the Agawam people engaged in trade, diplomacy, and kinship with other regional Indigenous people, most notably: the Quaboag to the East; the Podunk to the South; the Woronoco to the West; and the Nonotuck, Pocumtuck, and Sokoki to the North.

During the 1630s, when Agawam leaders invited English colonial settlers to build a small settlement here, they attempted to preserve, in written deeds, Indigenous cartographies and rights to hunt, fish, plant, and live on tribal lands. When diplomatic relations failed, the Agawam people were decimated and dispersed as a direct result of colonial deceit, disease, and warfare. Although the survivors sought refuge with other Native communities across the northeast, very few direct descendants of the Agawam people live in Springfield today.

We acknowledge, however, that many Indigenous nations, from the territory we now call “southern New England,” still survive and still exercise sovereignty. We acknowledge, in particular, these contemporary Indigenous nations: the Nipmuc to the East; the Wampanoag and Narragansett to the Southeast; the Mohegan, Pequot, and Schaghticoke to the South; the Mohican to the West; and the Abenaki to the North, among many others. Recognizing that the entirety of the North American continent constitutes territory considered to be original Indigenous homelands, we respect the sovereignty of these and hundreds of other Native American Indigenous nations that survive today and we pledge to support the rights of these nations and the interests of Indigenous peoples.

Authors: This land acknowledgement was written by Margaret M. Bruchac (Professor Emerita of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania) & Laurel Davis-Delano (Professor of Sociology, Springfield College), who provided permission for its inclusion in this document.

For this and more educational resources, go to sites.google.com/view/ springfieldagawam-landacknowl/

• Project Overview • Historical Context • Social & Economic Context • Community Context: Land & People • Food Security/Food Apartheid

Health & Wellbeing

• Building Community

• Sustainability & Green Space

• Economic Opportunities & Development

• Tier 1 Criteria & Methodology

• Tier 2 Criteria & Focus Area

• Tier 3 Criteria & Ground-Truthing

Parcels

• Farmers Markets Criteria & Methodology

• Farm Stands Criteria & Methodology

Initiatives,

• Municipal Initiatives

• Barriers Encountered

• Recommendations

• Urban Agriculture Ordinances in other Massachusetts Municipalities

• GIS Analysis

• Analysis Findings

• Works Cited

• Interviews & Correspondence

• Additional Sources

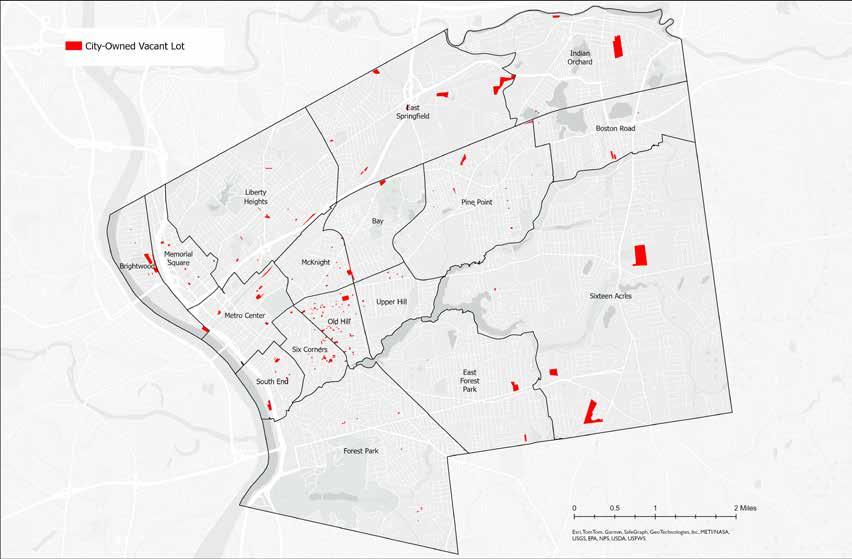

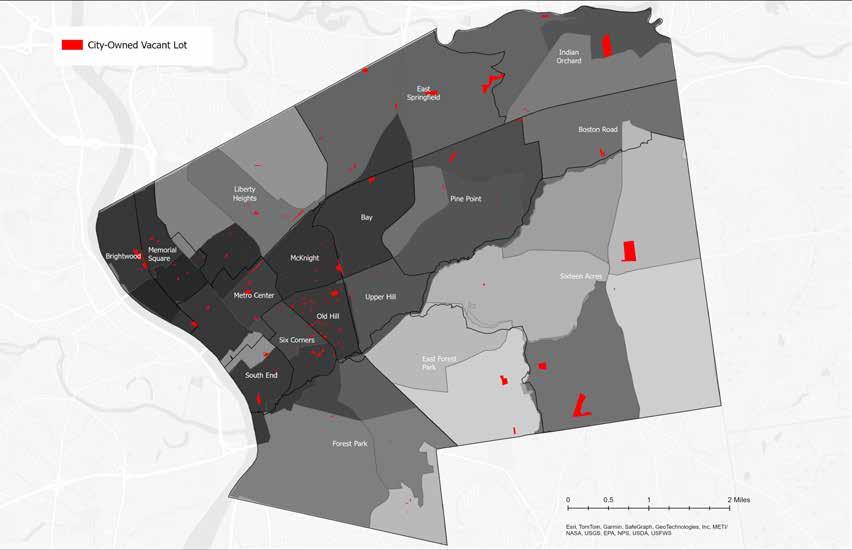

What would the City of Springfield look like if it could offer reliable access to nutritious foods year-round to all of its residents? Currently, many neighborhoods in the city are considered low income, with numerous households not owning a car and located far from stores with high-quality foods—causing many individuals and families to struggle with food insecurity. Some grassroots and policybased initiatives have developed in recent years with the goal of promoting a more equitable and effective food system within the city. One opportunity has emerged that has the potential to expand and integrate the city’s food system further within the grasp of residents: vacant lots. Such lots, which are abundant throughout Springfield, offer a potential space to grow and sell fresh foods close to home. Several vacant lots have already been cultivated for this purpose.

To continue the momentum and development of the local food system, this report, prepared for the Springfield Food Policy Council, maps existing vacant lots within Springfield to assess their suitability for food production and food access sites. The types of food production for which these lots could be used include community gardens, community farms, and urban orchards. Food access sites explored include farmers markets and farm stands. Through spatial analysis, recommended lots are guided by special criteria based on environmental factors, zoning considerations, structures on site, location, and overall size.

In addition to considering the usability of a site, this report identifies a focus area within the city, with the goal of determining which neighborhoods may benefit the most from increased access to land for growing fresh food or establishing food access sites. Criteria for the focus area considers the many benefits of urban agriculture centering around

health, community, sustainability, and general quality of life improvements; subsequently, the focus area is created based on maps of neighborhood vulnerability statistics, current health outcomes, and environmental factors relating to land use history.

Alongside recommending lots, this report gathers opportunities and recommendations on a municipal level with the goal of supporting the growth and ease of urban agriculture within Springfield. Special focus is given to potentially expanding Springfield’s existing Community Gardens Ordinance through the creation of an Urban Agriculture Ordinance, which could further support existing and potential farmers. These suggestions are based on the many farmingrelated city ordinances, zoning regulations, and general policies that have been adopted by other Massachusetts cities; in addition, recent goals articulated in municipal and statewide planning documents are highlighted. This section of the report aims to help support the Springfield Food Policy Council as it “develops community-driven municipal and statewide policy recommendations, including legislative bills focused on agriculture, retail, and builtenvironment solutions” (SFPC).

¿Cómo se vería la ciudad de Springfield si se pudiera ofrecer comidas saludables a todos los residentes todo el año? A pesar de ser una de las ciudades más grandes en Massachusetts, Springfield ofrece pocas opciones accesibles de comida fresca para los residentes. Muchos vecindarios en la ciudad son considerados de bajos ingresos. También, muchas familias no tienen un carro y viven lejos de mercados con comida saludable. Como resultado, muchas personas y familias tienen inseguridad alimenticia. Algunas iniciativas políticas y de base se han formado en años recientes con el objetivo de cultivar un sistema alimentario más equitativo y efectivo en la ciudad. Una oportunidad que ha surgido que tiene potencial de crecer e integrar el sistema alimentario de la ciudad más cerca de las manos de los residentes: parcelas vacantes. Estas parcelas, que son numerosas en Springfield, ofrecen un lugar potencial para cultivar y vender comida fresca cerca de casa. Algunas parcelas vacantes ya están usadas para este objetivo.

Para continuar el progreso del sistema alimentario local, este reporte, preparado para el Consejo de Política Alimentaria de Springfield (CPAS), muestra mapas de las parcelas vacantes que existen en Springfield y evalúa su conveniencia para ser sitios de producción y acceso de comida. Los tipos de producción de comida que estas parcelas pueden ser usados incluyen jardines comunitarios, granjas comunitarias, y huertos urbanos. Sitios para acceder comida incluyen ferias y puestos de granja. Por análisis especial, las parcelas son recomendadas a través de criterios sobre el medio ambiente, zonificación, edificios en sitio, ubicación en la ciudad, y tamaño.

También, este reporte identifica un área de interés en la ciudad, con el objetivo de decidir cuáles vecindarios pueden tener más

beneficios con la introducción de lugares para cultivar o comprar comida fresca. El criterio por el área de interés considera los beneficios de la agricultura urbana, que influye la salud, la comunidad, la sostenibilidad, y la calidad de vida. Seguidamente, el área de interés está creada por mapas de vulnerabilidad de vecindarios, resultados de salud, y la historia del uso de la tierra.

Además de recomendar parcelas, este reporte obtiene oportunidades y recomendaciones municipales con el objetivo de apoyar el crecimiento y facilidad de agricultura urbana en Springfield. Especialmente, la Ordenanza de Jardines Comunitarios debía expandirse con la creación de una Ordenanza de Agricultura Urbana, que podría apoyar a los agricultores nuevos y vigentes. Estas propuestas son fundadas en las ordenanzas, normas de zonificación, y pólizas usadas por otras ciudades en Massachusetts. También, los objetivos declarados en documentos municipales y de planificación están destacados. Esta parte del reporte es para apoyar el Consejo de Política Alimentaria de Springfield (CPAS) en cuanto proporciona “recomendaciones de políticas impulsadas por la comunidad, así como soluciones agrícolas, minoristas y para entornos construidos” (CPAS).

Food justice has long been a topic of conversation in Springfield. Many reports providing context, resources, and guidance on next steps have come before this one and helped address a myriad of food system concerns, while local organizations such as the Springfield Food Policy Council have helped lead the charge to “facilitate racially equitable food and social justice by developing a vibrant local food system with urban agriculture at its center” (SFPC). This report builds on a 2014 report, Food in the City, which assessed Cityowned vacant lots in Springfield for their suitability for use as community gardens, community farms, commercial farms, and urban orchards. Identifying suitable parcels, displaying case studies, and advocating for urban agriculture were the main purposes of Food in the City. A decade later, this report aims to provide updated information in a similar context to Food in the City, while further analyzing the connection between food access, land use, historical context, and public health outcomes. This report was conducted for and overseen by the Springfield Food Policy Council, and written by a team of graduate students from the Conway School.

Community engagement for this project consisted of eight individual interviews with core team members, farmers, City and state officials, and planners in Springfield. Interviews were conducted over Zoom, lasting thirty to sixty minutes each. The following people were interviewed for this project, and details of each interview can be found in the Appendices section of this report.

• Becky Basch, Senior Planner, Pioneer Valley Planning Commission

• Benjamin Bland, Mass in Motion Coordinator, City of Springfield

• Liz O’Gilvie, Director, Springfield Food Policy Council and Gardening the Community, Springfield

• Ashley Randle, Commissioner, Massachusetts Department of Agriculture

• Catherine Ratté, Director of Land Use and Environment Department, Pioneer Valley Planning Commission

• Anne Richmond, Owner, Nordica Street Community Farm, Springfield

• Catherine Sands, Founder, Fertile Ground LLC.

• Patrick Sullivan, Director, Department of Parks, Buildings, and Recreation Management, City of Springfield*

* Also present at this interview were Alex Sherman, Forestry; Tom McCarthy, Clean City Division; and Tom Dougal, Assistant Director of the Department of Parks, Buildings, and Recreation Management

“In

this world, the advancement of one community depended on the destruction of the other, creating collective advantage for one group at the expense of targeted groups’ ability to survive. As the economy grew, it developed in tandem a social world riven by racialized inequality and violence.”

-K-Sue

Park, “Race, Innovation, and Financial Growth: The Example of Foreclosure”

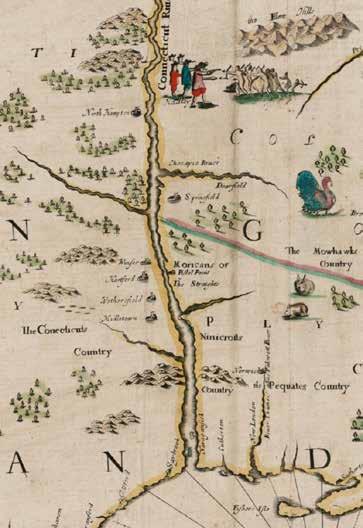

The geography and natural resources of what would be called the Connecticut River Valley has long attracted human use and settlement. Indigenous peoples hunted, fished, foraged, and planted in the fertile alluvial soils along the river for over 10,000 years. In the 1630s, the Agawam peoples first encountered English colonists from the Massachusetts Bay Colony who sailed up the Connecticut River hoping to procure new areas for expanding the profitable beaver fur trade. William Pynchon, who is referred to in many histories as the “founder” of Springfield, was one of three colonists to sign a deed along with thirteen Agawam people that in 1636 allowed for white settlement on hundreds of acres on both sides of the Connecticut River, from the present day city of Holyoke to the town of Agawam. The Pynchon family was eager to have a strategic location to establish a trading post near three major rivers—the Connecticut, the Chicopee, and the Westfield—that also intersected with Native trails that became important roadways connecting the area to Boston to the east and to Albany to the northwest.

Among the many skills that the colonists learned from the Indigenous people that enabled the settlers to carve a living from the land, two stand out: how to clear the unfamiliar woods with fire, and how to grow Indian corn (maize), which became the North’s leading agricultural product (Rothbard 2012). What the two groups certainly did not share was an understanding of land as a commodity. The trade activities that colonists established with the Indigenous populations were based on credit, with the promise of the Native people to supply furs in exchange for trade goods. When the fur supply started to wane in the 1650s and the Native people were unable to pay their debts, they were forced to sell land to discharge their debts. This practice

established what one scholar describes as “the Pynchon family’s famous monopoly” wherein both Pynchon and colonial subtraders, who were themselves indebted to Pynchon, acquired mortgaged deeds from most of the Native families still living in Springfield. By the 1670s, the imposition of mortgages and foreclosures had a “‘virtually catastrophic’ effect on the Woronoco, Agawam, Norwottuck, Pocumtuck, and Squakheag” as “colonists’ land hunger threatened the communities with starvation” and after the King Philip’s War of 1675-76 “ultimately forced their migration from the area” (Park 2021, 41).

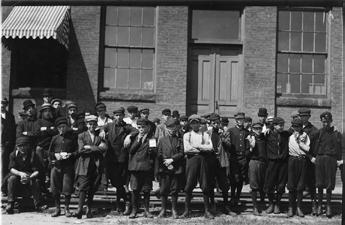

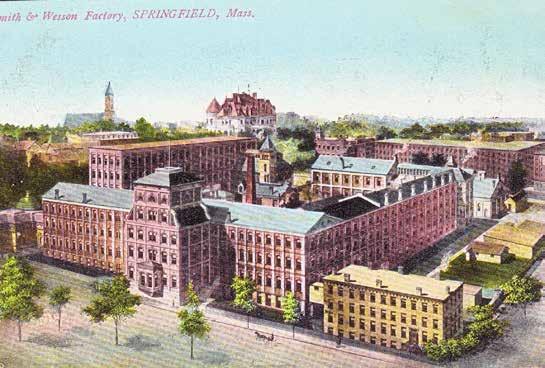

Thanks to the abundance of waterpower and its position as a meeting point between trade routes, Springfield quickly evolved from an important distribution point for agricultural goods and livestock to manufacturing. Early industrialization included small grist and saw mills, and by the end of the eighteenth century there were paper mills, distilleries, and pottery manufacture among other industries (Foster et al. 2006). George Washington’s selection of Springfield to be the location of the country’s first arsenal in the 1770s propelled the city’s metal manufacturing business. As a producer and depot for weapons and ammunition, the Springfield Armory was the site of innovative technical advances and led to the development of a skilled labor force. Over the next century, dozens of new companies manufactured railroad coaches, locomotives, motorcycles, and even ice skates.

Source:

Lewis Hine, Group in front of Indian Orchard

Co

1911, Indian Orchard, Mass. Hine worked for the National Child Labor Committee that documented the use of child labor throughout the U.S.

Parts of the complex survive today as the Stockbridge Court apartments.

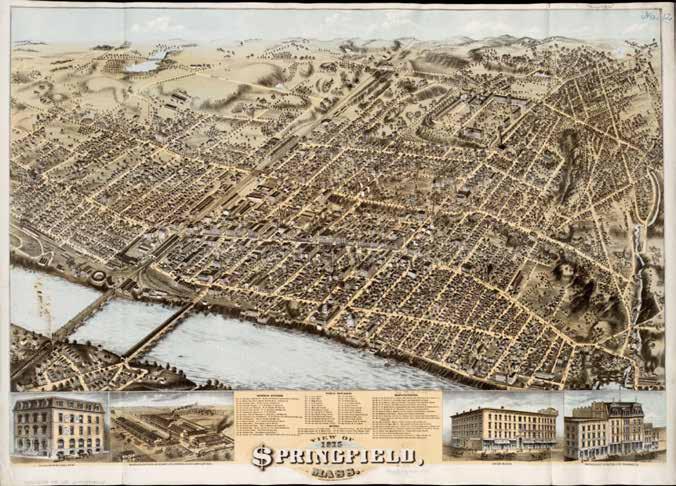

The 1875 bird’s-eye map of Springfield highlights the city’s manufacturing and business prowess, as evinced by the dollar sign that stands in for the “S” in Springfield. An extensive legend on the map attests to the range of businesses, public institutions, and industries that were feeding the flourishing economy. Not surprisingly, during this same period a housing boom occurred. A notable example is the establishment of one of the first planned residential neighborhoods in the U.S., the McKnight neighborhood. The purchase of a twenty-two-acre farm in the 1870s by John and William McKnight grew into the acquistion of hundreds of more acres, many of which were bought from Primus Mason, a very successful Black entrepreneur

and philanthropist (Our Plural History 2009). The 250-acre historic McKnight neighborhood is on the National Register of Historic Places and contains 850 buildings, most constructed before 1910. Springfield was given the nickname “The City of Homes” in response to the construction of these numerous Victorian mansions as well as numerous single-family homes for manufacturing workers (Springfield 2021).

Not represented in the map is the extractive nature of the land use or the human labor that made it possible. As the demand for labor grew children entered the labor market, working in dangerous industrial settings until curtailed by law (“Teaching with Documents”).

Source: Digital Commonwealth

As a center for trade and industry, Springfield has long been a city that attracted newcomers, which vitalized and diversified the city. In the early decades of the twentieth century the city continued to grow eastward from the city center, particularly along railways and roadways. As the 1940 Land Utilization Map made for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) indicates, remaining open space is differentiated as types of

cropland, pasture, and forest with a variety of light-colored lines and hash marks. The densest areas of development are the darkest lines identified as “thickly settled areas” or “industrial and commercial areas” in the map’s symbology. However, what is not identified on the map is the degree to which urban agriculture was taking place. For example, photographs of Springfield taken by the WPA at the same time indicate that there were urban farms in these denser “thickly settled areas.”

In the second half of the twentieth century the long-standing manufacturing sector began a steep decline, including the closure of the Springfield Armory in 1968 (Mass Moments). At the same time, federal highway projects such as Interstate-91 tore into lower-income Black and Hispanic neighborhoods and separated the city from the Connecticut River. The loss of skilled, working class jobs negatively affected Springfield’s financial prosperity as did racist policies and actions of loan corporations that encouraged white flight, wherein white families en masse moved from the city into the surrounding suburbs, further decreasing Springfield’s tax base and economic resources. This trend was not unique to Springfield, but rather occurred across the country.

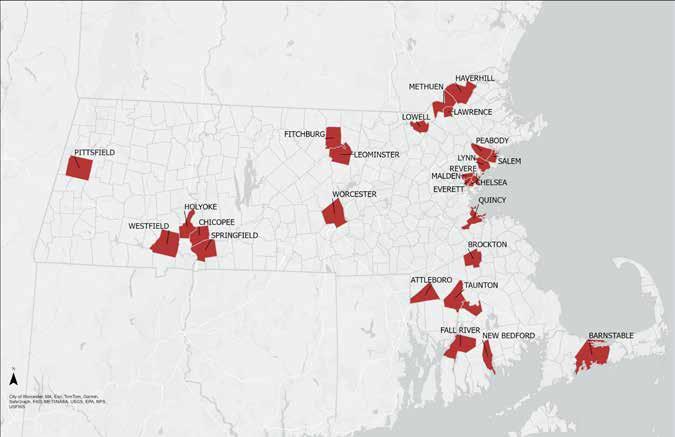

In 2009 the Massachusetts’ legislature created a designation for mid-size cities that had a largely industrial past, lower-income residents, and below-average education-attainment levels compared to the state average. These “Gateway Cities,” as they were labeled, are urban centers with larger populations of people of color that have been discriminated against and under-resourced for decades. Springfield is recognized as one of these twenty-six Gateway Cities that has enormous potential and has thus been eligible for particular state grant programs.

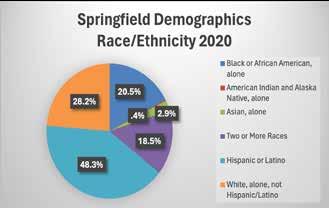

Springfield, with a population of 155,929 people per the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau statistics, has long been the third most populous city in the state. It has benefitted from its diversity of people who came to the city by choice, necessity, or in bondage. Black people have helped build Springfield since its establishment in the seventeenth century.

John Pynchon, son of William Pynchon, is recorded as having enslaved numerous Black persons (Carvalho 2010, 6). Slavery was given the sanction of law in 1641 and other prominent and affluent people held Black people as slaves until the state abolished slavery in 1791 (Kazini 1977, 2). Before the Civil War, many aspects of the burgeoning economy were tied to the slave economy of the South, even as Springfield itself became a locus of abolitionist sentiment. A growing population of free African-Americans moved to the city in the 1830s to 1850s and helped establish Springfield as a way-station in the Underground Railroad. The Black population established important institutions in the city and continued to thrive despite discriminatory hiring and housing practices (Kazini 1977; Viles and Palpini 2017).

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the city has also been a gateway for waves of Irish, German, Italian, French Canadian, and Polish immigrants. As part of the Great Migration, thousands of Black people fled the South and the community in Springfield grew considerably between 1900 and 1940, from 1,021 to 3,212 (Our Plural History 2009).

After WWII, the Latino population grew significantly, especially Puerto Rican people who began arriving to fill agricultural jobs in western Massachusetts. Springfield has the state’s largest population of Puerto Ricans, which increased in 2017 in the wake of Hurricane Maria and is a regional center of Latino culture and opportunity (Granberry and Valentino 2020; Our Plural History 2009).

Today, immigrants continue to be drawn to the U.S. by economic opportunities and Springfield

is no different. There are growing vibrant immigrant communities among West African and Southeast Asian populations.

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the largest ethnic or racial group in Springfield is Hispanic/Latino, constituting over 48% of the population. By comparison, the white, nonHispanic population is over 28% and the Black population constitutes a little over 20%. However, according to a follow-up study by the Census, the Hispanic and Black populations were undercounted. The Hispanic or Latino population had a statistically significant undercount rate of 4.99%. The Black or African American alone or in combination population had an undercount of 3.3% (U.S. Census 2022). As a Brookings report pointed out, these undercountings have real consequences: “there is widespread concern among Latino leaders and advocates about what this undercount could mean for their communities. In short, undercounting Latinos has drastic implications for health care, families, education, and political representation for at least the next decade if not more” (Sanzhez 2022).

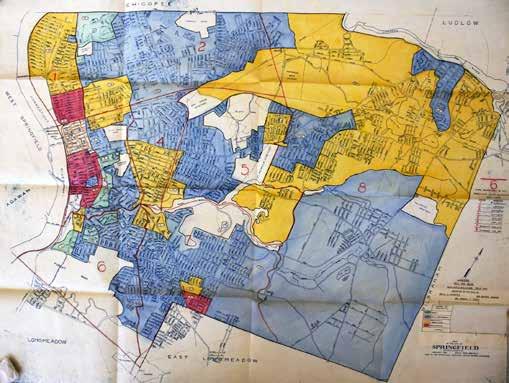

Beginning in the 1930s as part of the New Deal, the federal government created a government-sponsored loan corporation that assessed the level of risk involved in lending money to specific neighborhoods. Color-coded “residential security maps” were developed and used by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to decide whether or not a property was a good candidate for investment. The colors—from green to blue to yellow to red— indicated the risk level. The most “hazardous” were red, hence the term “redlining.”

The delineation of these “risky” neighborhoods was largely based on race, so that Black individuals and other people of color would be cut off from lending and investment. As a result, many people of color were excluded from the opportunity to invest in property and build generational wealth (Rothstein 2018). The result of these discriminatory practices can be seen decades later in Springfield’s economic and racial distribution patterns.

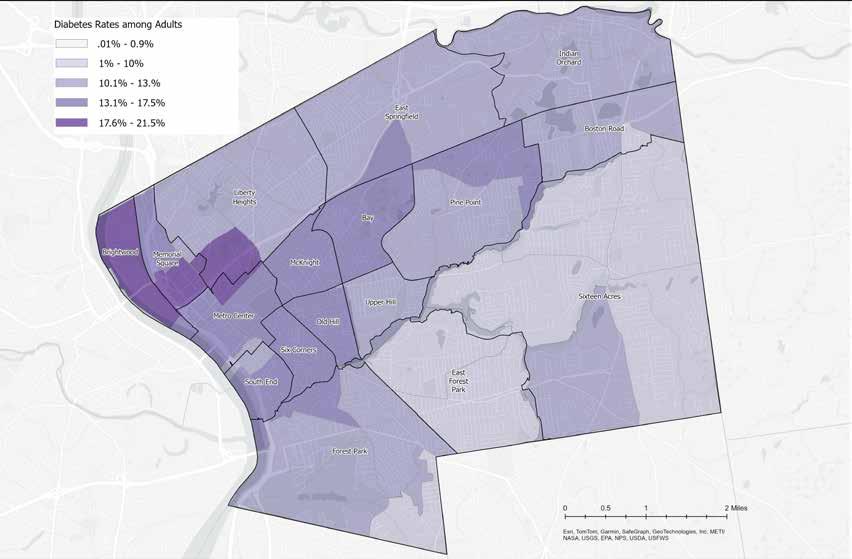

in decision-making processes, which has allowed discrimination and racism to perpetuate and infiltrate many aspects of marginalized communities’ everyday lives, as can be seen with health inequality. As mentioned, practices such as redlining and discriminatory zoning have unfortunately played a large role in determining what groups

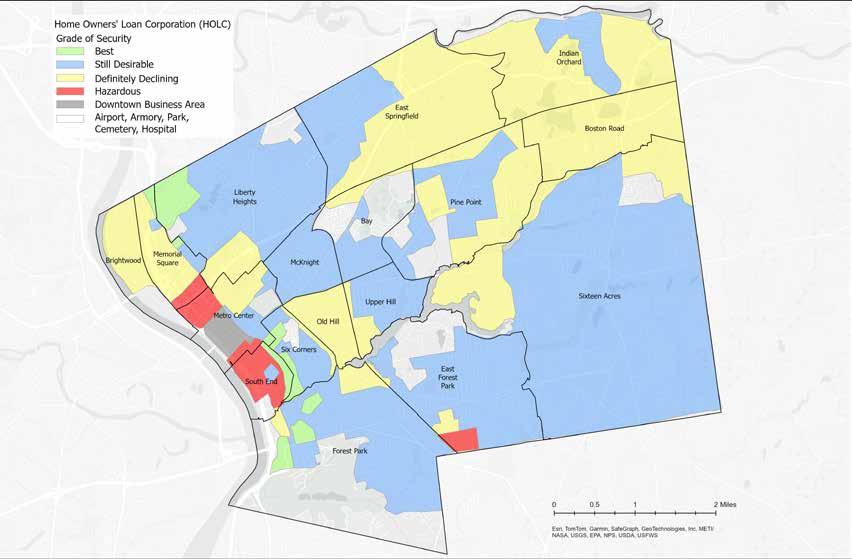

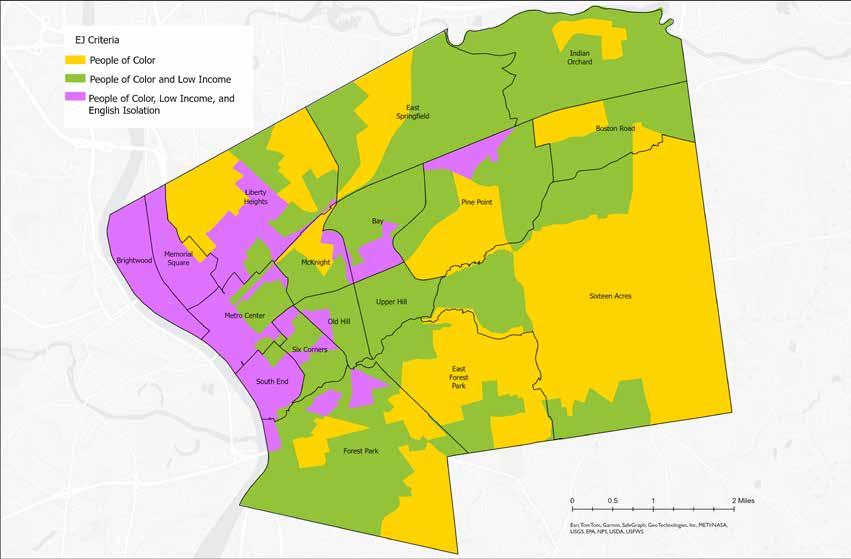

Environmental Justice (EJ) is based on the principle that all people—regardless of race, color, nationality, or income—have the right to be protected from environmental pollution and to live in a clean, healthy environment. Historically, people of color and lower-income individuals have been excluded from influence

of people live in certain areas, contributing to racial segregation and inequitable distribution of resources and hazardous sites. Marginalized communities are more likely to live near toxic waste sites, in areas with high air pollution, and in low-quality housing. These longstanding structural inequities also result in fewer healthcare providers, decreased transportation options, and limited access to health information due to a lack of education about resources and minimal bilingual options (Egede 2023).

Source: Mapping Inequality website: Springfield, MA

This map indicates that very little property in the City of Springfield was considered “Best,” or areas eligible for mortgages and lower interest rates. Although large sections were considered “Still Desirable,” sizable areas along the most industrial parts of the city were designated “Definitely Declining.” The oldest and densest part of the city center along the Connecticut River was labeled “Hazardous.”

“The history of redlining, segregation, and disinvestment not only reduced minority wealth, it impacted health and longevity, resulting in a legacy of chronic disease and premature death in many high minority neighborhoods.... On average, life expectancy is lower by 3.6 years in redlined communities, when compared to the communities that existed at the same time, but were high-graded by the HOLC.”

-National Community Reinvestment Coalition, “Redlining and Neighborhood Health”

Source: MassGIS: Environmental Justice Populations (2020)

Building on federal guidelines, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts established criteria by which communities throughout the state are identified as the most susceptible to environmental injustice. The Environmental Justice blocks indicate that areas with the highest concentrations of people of color, with low income, and with English isolation are located in the western portion of Springfield, although the entire city qualifies as an “Environmental Justice community.” This designation directs all state agencies to involve EJ populations in the decision-making process when drawing up policy and

undertaking projects. In addition, it grants financial resources or technical assistance to the most overburdened communities (“Environmental Justice Policy” 2022).

The areas indicated in purple and darker green roughly correspond with the neighborhoods that were classified as red (“Hazardous”) and yellow (“Definitely Declining”) in the 1935 Residential Security (Redlining) Map. This is one way we can see the effects of underinvestment, decreased access to mortgages, and decreased opportunities to build generational wealth in these areas of the city today.

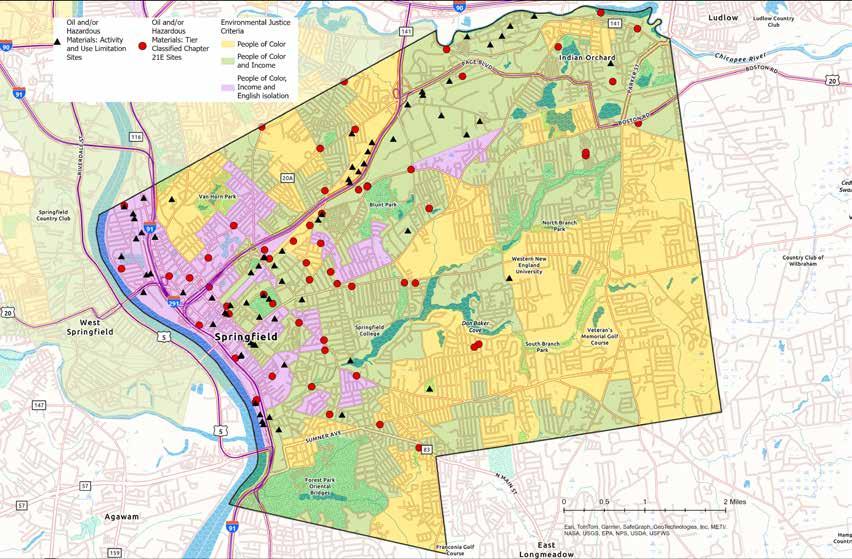

Source: MassGIS: Environmental Justice Blocks (2020), MassDEP Tier Classified Oil and/or Hazardous Materials Sites (MGL c. 21E) (2024), MassDEP Oil and/or Hazardous Material Sites with Activity and Use Limitations (AUL) (2024)

The 2020 Environmental Justice map is presented with a basemap highlighting major highways that bisect neighborhoods along the Connecticut River and diagonally along a northeast axis. These are overlaid with data layers indicating the presence of contaminated sites. The two categories for the oil and/or hazardous material disposal sites indicate the level of risk that they pose. Sites that have not been cleaned up within one year are ranked and classified as Chapter 21E sites for continued remediation (fifty-eight properties) and Activity and Use Limitation (AUL) sites indicate that there is some level of

contamination remaining after a cleanup (seventy-six properties).

The majority of the hazardous sites are situated in the westernmost section of the city, located along the largest and busiest roads and interstates, and in areas where the population falls into at least two EJ criteria categories. These are the areas where highways have been built, waste is stored, industrial warehouses and facilities are concentrated, and where natural resources have been readily exploited. This map demonstrates the long-lasting effects of redlining and environmental injustice.

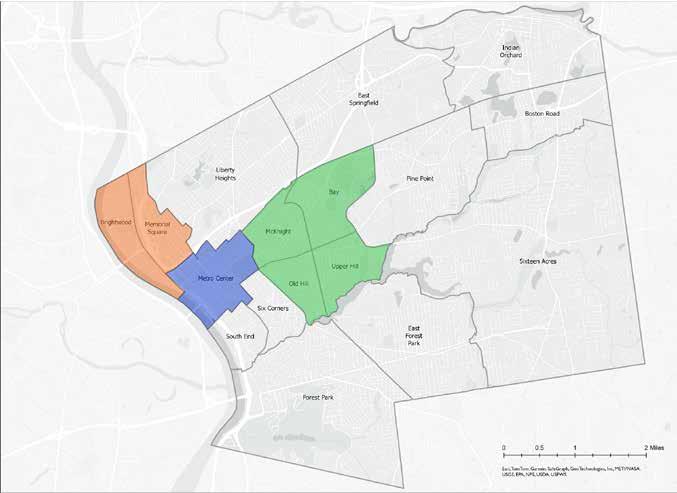

Springfield contains seventeen neighborhoods: Brightwood, Memorial Square, Liberty Heights, East Springfield, Indian Orchard, Boston Road, Pine Point, Bay, Upper Hill, Old Hill, McKnight, Metro Center, South End, Six Corners, Forest Park, East Forest Park, and Sixteen Acres. Certain neighborhoods of the city are often talked about in groups, as they share a zip code, and some of those groupings are referenced throughout this report. Brightwood and

Memorial Square are “North End”; Metro Center is “Downtown; and Bay, Upper Hill, Old Hill, and McKnight are referred to as “Mason Square,” named after the Black philanthopist Primus Mason and the commercial area where the four neighborhoods converge.

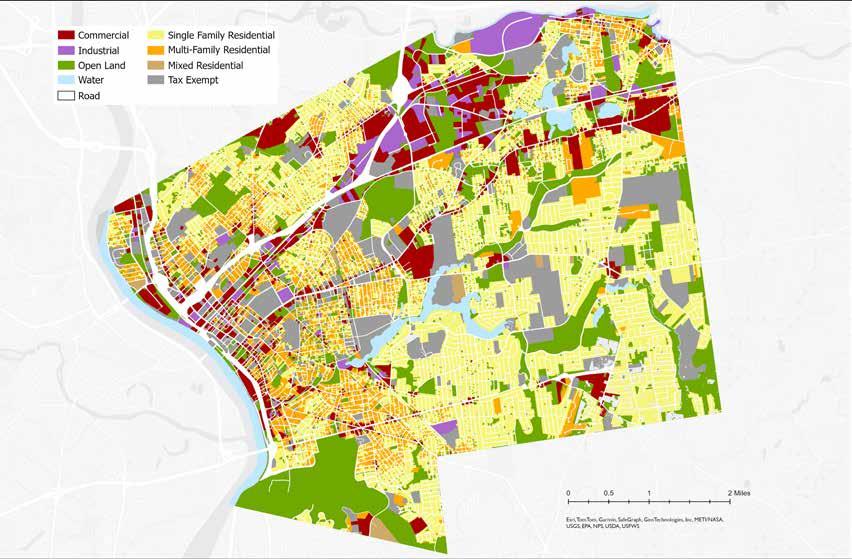

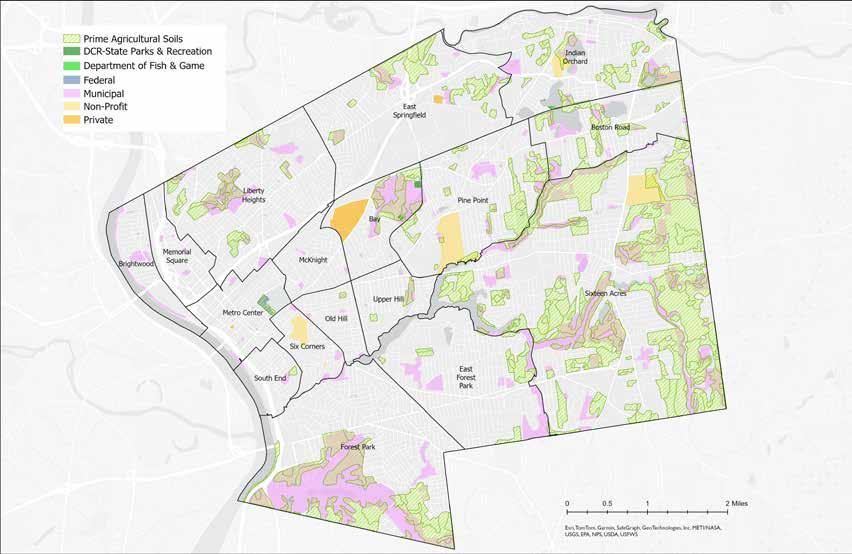

The maps presented in this section of the report demonstrate present-day Springfield’s patterns in land use and centers of community.

Source: City of Springfield: Neighborhoods

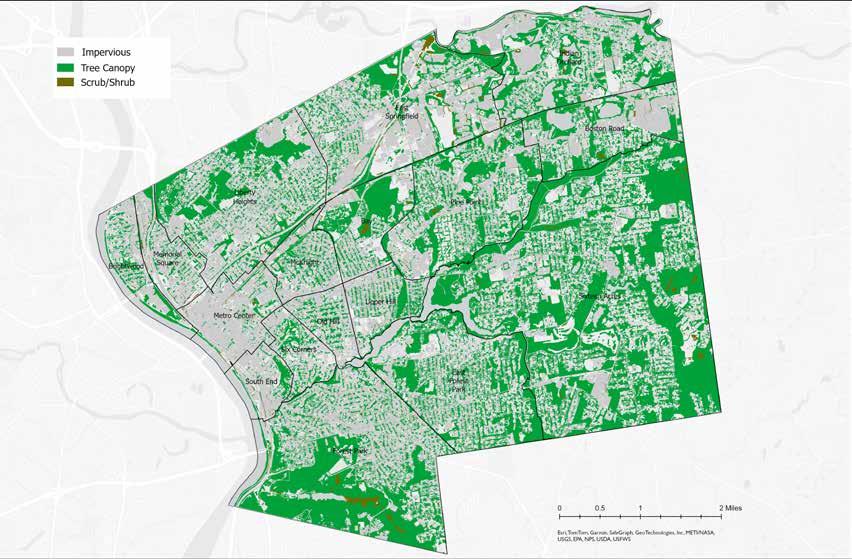

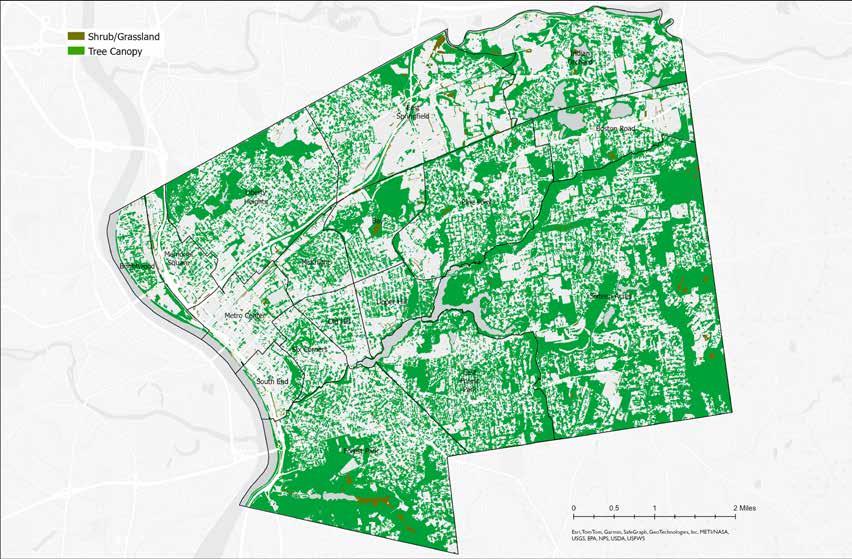

Similarly to the patterns of the redlining and environmental justice maps, the composition of land use shifts dramatically from the western to the eastern side of Springfield. Concentrated in the western side of the city, along the Connecticut River and following major roads, a mix of uses including commercial, industrial, and multi-family homes is in place. Moving east, the uses change to predominantly single-family homes with larger swaths of open land, usually taking the form of city parks. In the northern part of the city, commercial and industrial uses follow Highway 291.

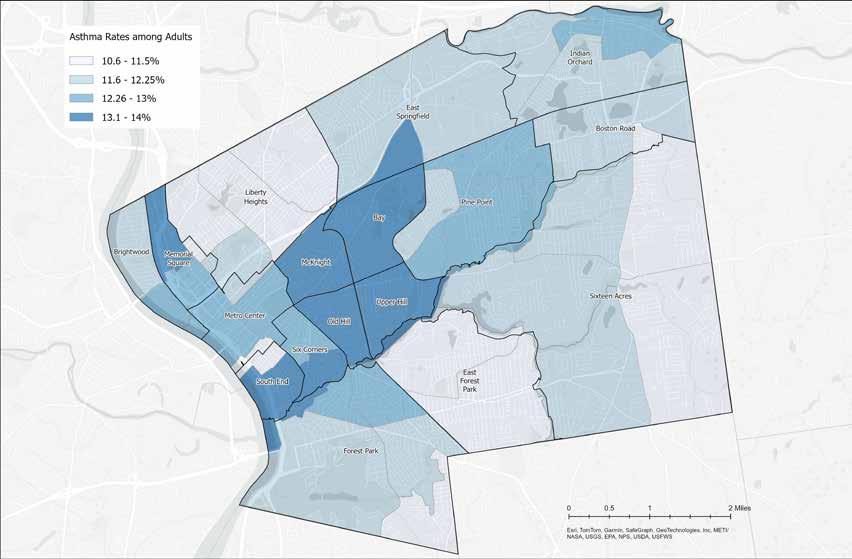

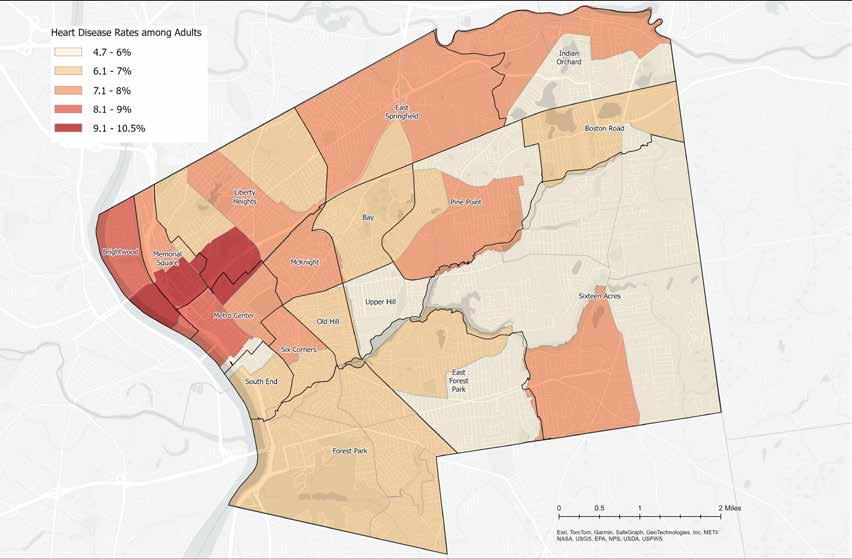

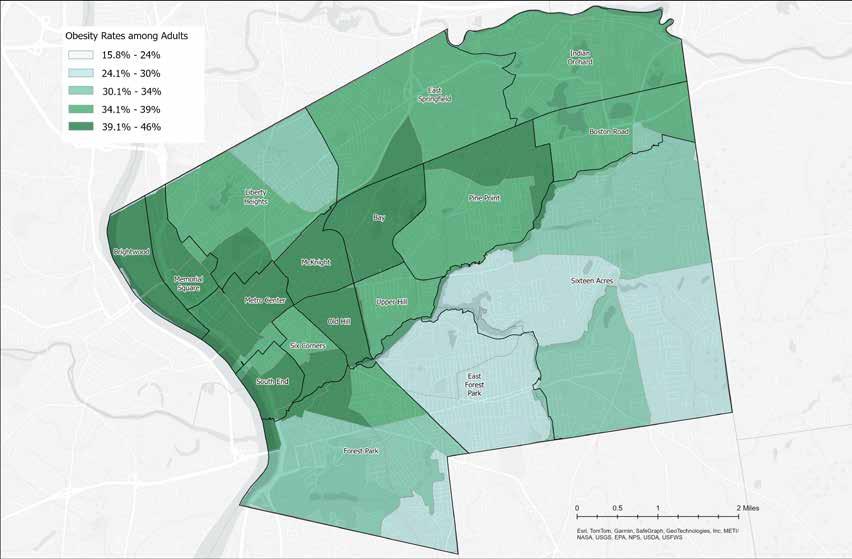

Industry, highways, and commercial use in the western and northern parts of the city can create air, noise, and soil pollutants, and proximity to these areas may lead to negative effects on residents’ health. These effects are shown in a series of health outcome maps in the Identifying Parcels for Food Production: Tier 2 Criteria and Focus Area section of this report. Increased access to green space, seen in the eastern part of the city, is shown to better physical and mental health outcomes (“How Parks and Green Spaces” 2022).

Source: MassGIS: Land Use/Land Cover (2016)

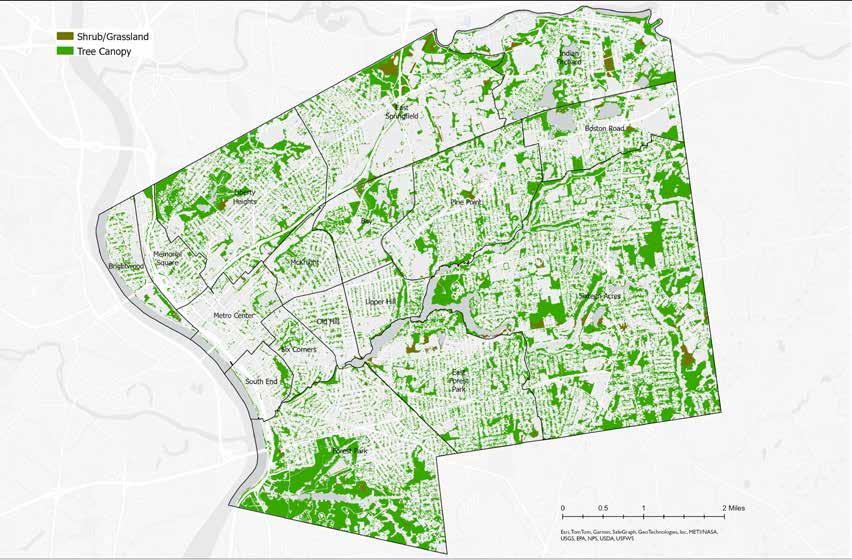

Land cover is heavily influenced by land use in Springfield. Impervious surfaces dominate the western portion of the city where there is a mix of commercial, industrial, and multi-family residential uses, while trees and shrubs are much more present throughout the eastern portion of the city.

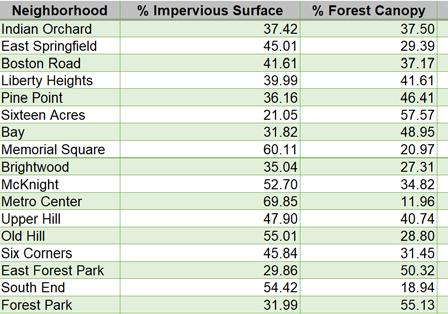

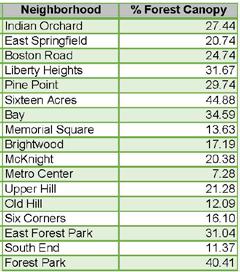

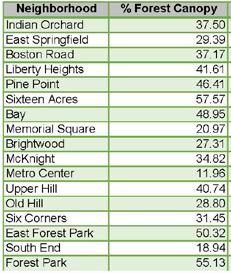

A study conducted by ReGreen Springfield in July 2023 aimed to “comprehensively examine the relationship between tree canopy, land cover, demographic information, and environmental justice in the neighborhoods of Springfield” (ReGreen 2023, 1). It was found that neighborhoods with the least tree

coverage coincide with neighborhoods with the highest percentage of lowest income and people of color, as shown in the “Environmental Justice Blocks” map on the previous pages. Benefits trees provide include improved air quality, mitigation of respiratory problems, lower surface temperatures, social and psychological benefits, and ecological benefits (ReGreen 2023). Considering the evidence from this study in conjunction with the land use and land cover maps helps identify areas of the city that might benefit from increased access to green space or canopy cover.

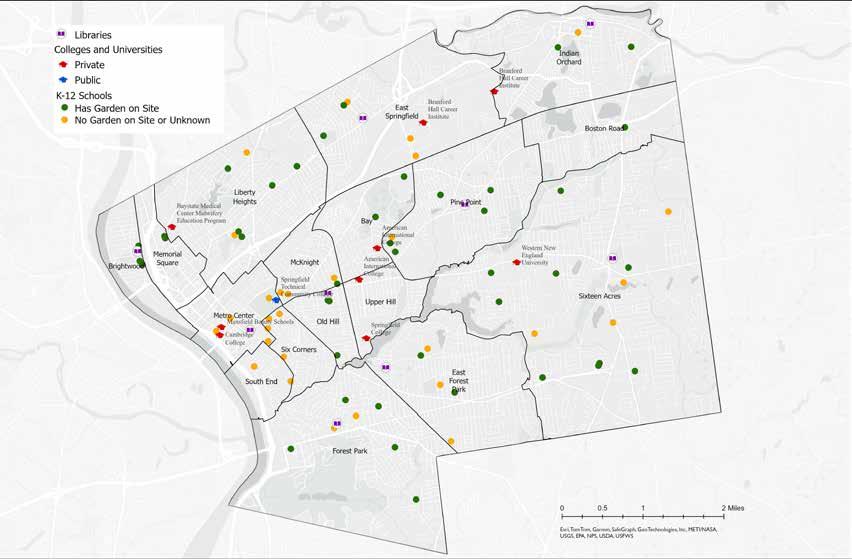

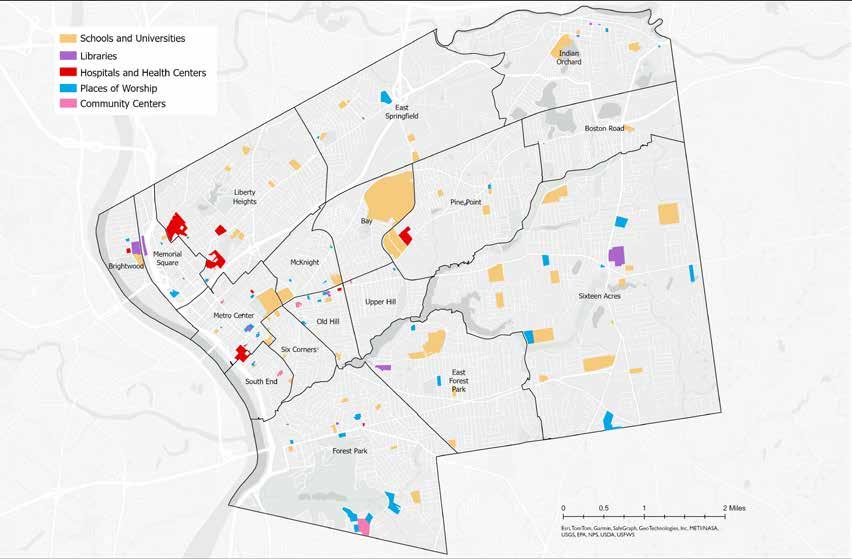

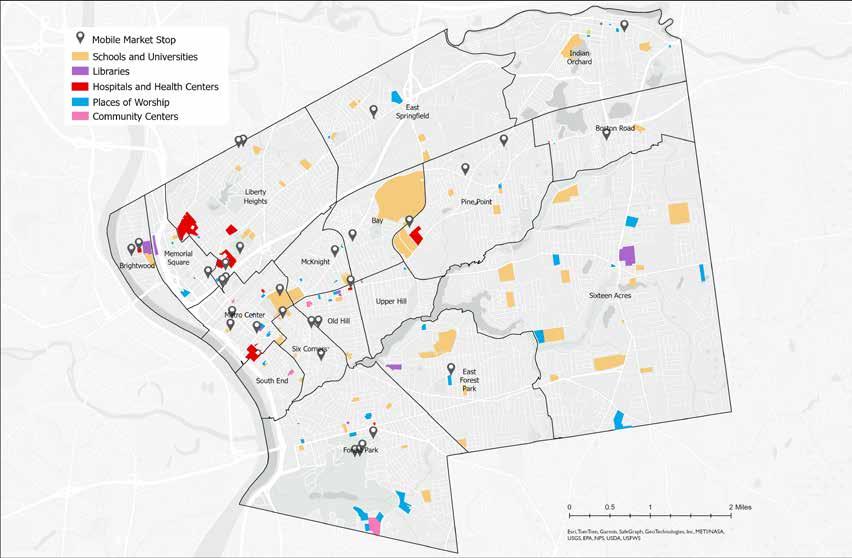

Source: MassGIS: Colleges and Universities (2018), Massachusetts Schools Pre-K through High School (2023), Libraries (2017); Springfield Public Schools Garden Coordinator: list of SPS with gardens on site (2024)

K-12 schools are present in every neighborhood of Springfield, and are fairly evenly distributed spatially across the city. Over forty of the sixty-six schools in the Springfield Public School District have raised garden beds for educational use with dedicated staff to oversee their upkeep (Home Grown Springfield 2024). The school garden program is part of the Springfield Public School’s larger Home Grown Springfield Culinary and Nutrition Program that the Springfield Food Policy Council was

instrumental in developing (Sands, Transforming School Food 2020). Springfield Technical Community College (STCC), the only public institution of higher education in the city, is located in the Metro Center neighborhood. The remaining colleges and universities in Springfield are private, and are scattered across the northern and central parts of the city.

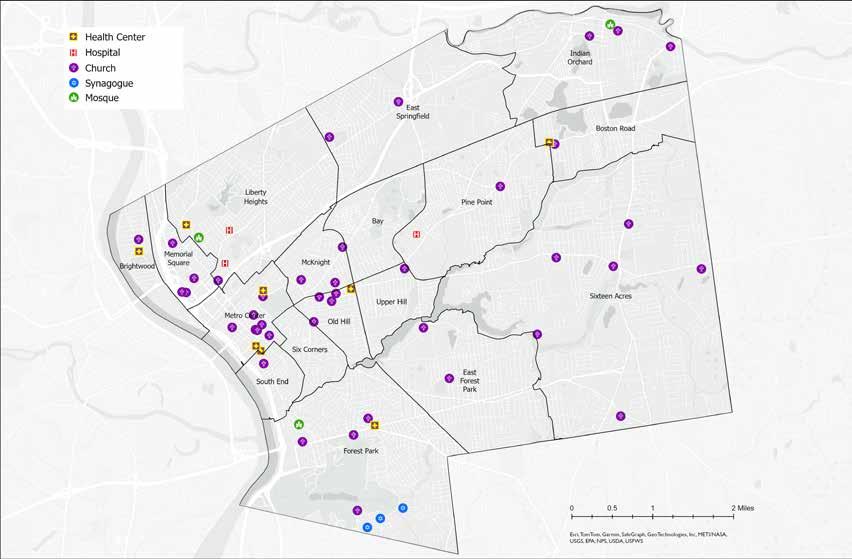

Source: MassGIS: Acute Care Hospitals (2018), Non-Acute Care Hospitals (2018), Community Health Centers (2019), Places of Worship (2022)

There are places of worship in almost every neighborhood of Springfield, with Metro Center and parts of the Mason Square neighborhoods being the most densely populated with churches. The hospitals are located in the Liberty Heights and Pine Point neighborhoods, outside of the downtown area, while community health centers are located closer to downtown.

Similar to schools and libraries, places of worship, health centers, and hospitals provide opportunities to locate gardens, farm stands, and farmers markets. An added benefit is that these institutions already host a community of individuals who regularly visit the site, which can encourage consistent involvement in whichever type of urban agriculture may occur there.

Having access to an adequate supply of healthy food is a basic human right. When considering the absence of this right, the phrase “food apartheid” has been used by food justice advocates in lieu of the more common term “food desert” as it highlights the deeply rooted history of racial discrimination and inequitable policies that have shaped food access and control (Jensen 2024; Walker 2023; Rivera 2023). The USDA stopped using the term “food desert” more than a decade ago because it did not adequately describe the type of food insecurity that the data was charting. Their Food Access Research Atlas replaced the older Food Desert Report (USDA “Food Access Research Atlas”). The City of Springfield experiences food apartheid: many residents have low access to healthy food as well as face socioeconomic and racial barriers. Food apartheid not only describes the lack of resources available to a community, but also the health consequences that come with it. Areas experiencing food apartheid typically have higher densities of convenience stores and fast-food restaurants (Bower 2013).

Convenience stores are heavily patronized in densely populated neighborhoods as a

replacement for the lack of larger grocery stores in the area (Eisenhauer 2001). The quality of food offered is often lower compared to fresh produce found in a typical supermarket and the price of the food items is also higher in convenience stores.

A 2018 study, Springfield Food Retail Environment Survey for Health (FRESH), conducted by the Springfield Department of Health and Human Services (SDHHS) Mass in Motion Program with assistance from the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission (PVPC), looked at the availability of different products and stores’ use of SNAP/WIC programs and accessibility. The objective of the research was “to quantify ways in which small food retailers are or are not improving health food access in the communities in which they do business” (Springfield FRESH 2018). The results of that study indicated that most convenience stores were not providing healthier food options such as fresh/canned/frozen/dried fruit and vegetables, fat free or low fat dairy and milk alternatives, 100% fruit juices, whole grain breads and cereals, whole grain and low fat snack bars, and nuts (Springfield FRESH 2018).

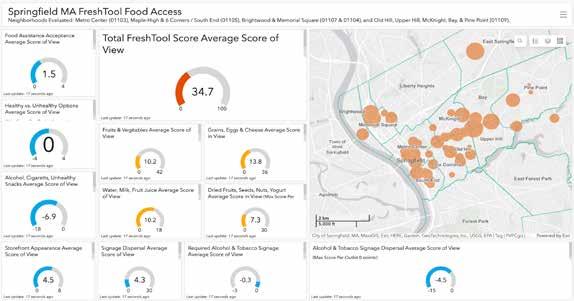

This dashboard, produced as part of the Springfield FRESH study, is updated in real time. It can be accessed at https://pvpc.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/f6ba82f6b1f6417a96b3871c482f9705.

Food availability is more than just the number of food options available; it is also about the diversity of stores from which to choose and the availability of transportation from where people live to food access points.

Food inaccessibility is determined by the spatial accessibility and affordability of food retailers. It considers factors like travel time to shopping, available transportation options, and food prices.

Food insecurity is affected by a broad array of factors, with food inaccessibility and food unavailability involved. It could be defined as the instability of food intake due to financial, socioeconomic, and other factors that ultimately have negative effects on one’s health. The USDA simply defines food insecurity as “the lack of access, at times, to enough food for an active, healthy life” (“Food Security in the U.S.: Overview” 2023).

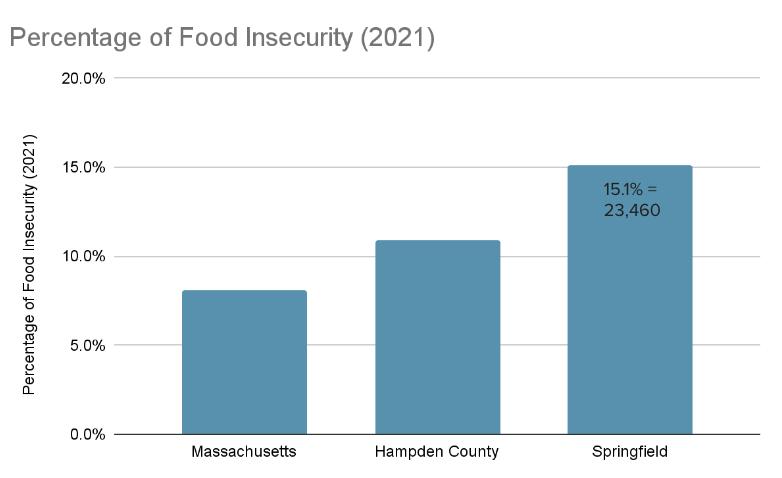

Source: Feeding America’s “Map the Meal Gap 2023: An Analysis of County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2021” and The Food Bank of Western Massachusetts’s “Local Hunger Data” (accessed 5 March 2024).

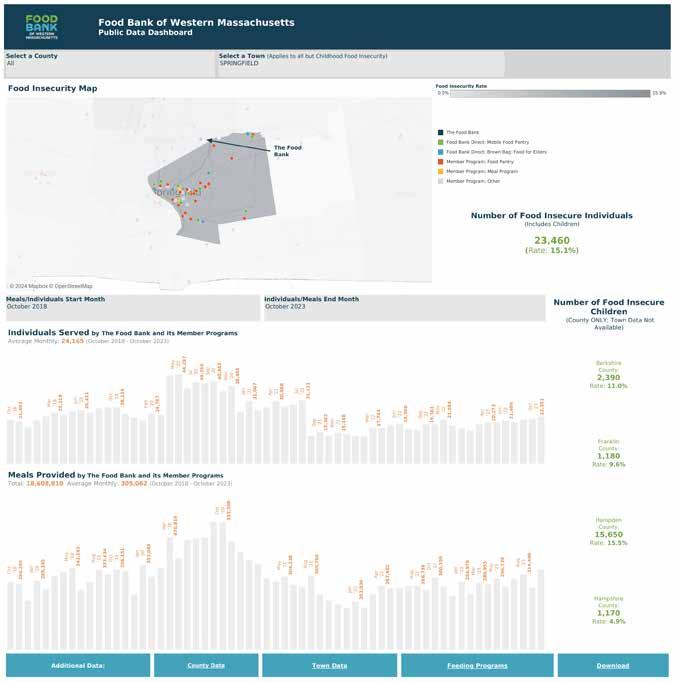

According to the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, Hampden County has the highest rate of food insecurity in the state at 10.9%, and Springfield has the second highest rate after Holyoke at 15.1%. The Massachusetts food insecurity rate in 2021 was 8.1%.

Feeding America started producing annual estimates of local food insecurity in 2011. The Map the Meal Gap data source for the U.S. population takes into consideration unemployment rates, median income, adjusted poverty rates, homeownership rates, percent of the population that is Black, and percent of the population that is Hispanic, and disability rates (Map the Meal Gap 2023: Technical Brief).

The Food Bank of Western Massachusetts provides statistics about local food insecurity not provided by Feeding America or the USDA. According to its website, the Food Bank collects data about food insecurity at its distribution sites and its partner member agencies. It asks for a person’s place of residence, the number of people in their household, and the age ranges of people in their household. The data graphs show the range of distributions over a five-year period. The numbers demonstrate that there was a spike in food insecurity during the first year of

the COVID-19 pandemic and then a subsequent decrease in the second half of 2021-2022.

Clay Gregory, senior content coordinator at the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, explained that the implementation and expansion of federal assistance programs decreased food insecurity levels to below prepandemic levels beginning in August 2021. However, the expiration of those programs in 2023, coupled with rapid inflation, has accelerated food insecurity.

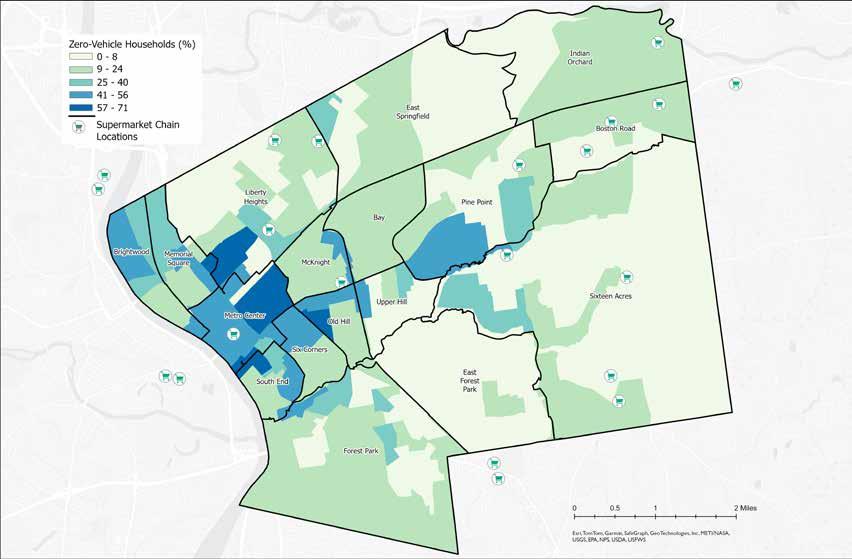

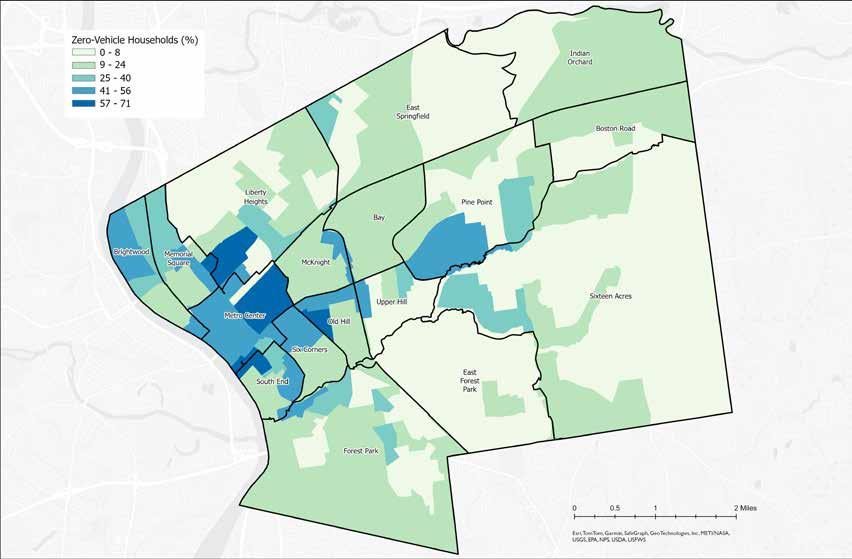

This vehicle access map is developed from 2022 census data. Darker tones indicate higher percentages of zero-vehicle ownership. This map differs slightly from the USDA’s 2019 low-vehicle access map, which considers tracts—each with varying population densities—as low-access if one hundred or more households do not own a vehicle. The national average for zero-vehicle ownership is 8% (Forbes); on this map, every area except the palest color exceeds the national average, with some neighborhoods reaching up to 71%.

Zero-car ownership is highest in portions of Memorial Square, Liberty Heights, Metro

Center, Old Hill, and South End.

Given America’s history of car-centric planning, basic resources such as large grocery stores are frequently far from many residential areas. Not owning a car is especially burdensome in these cases, for individuals must rely on public transportation or walking to reach their destinations. The difficulty of such travel naturally leads families to choose food options closer to home, which may be convenience stores or fast-food restaurants that have lower-quality foods with minimal nutritional value.

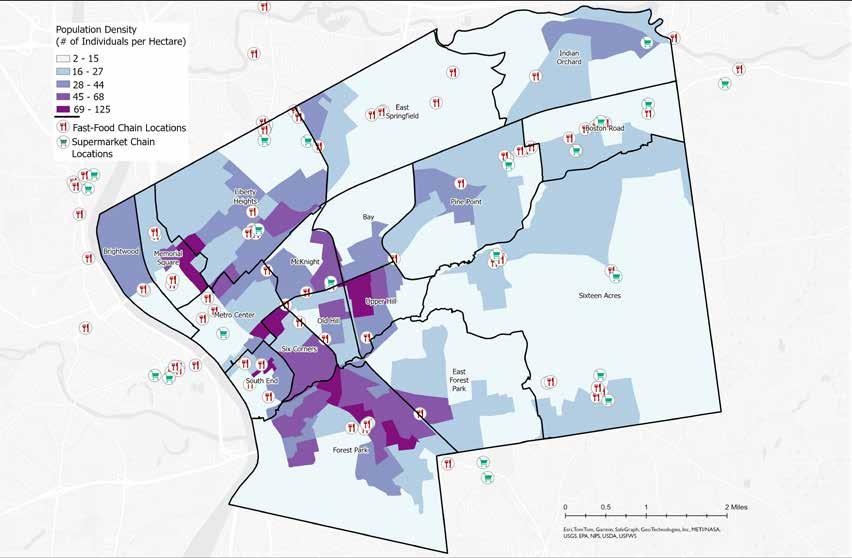

Springfield is most densely populated within Memorial Square, Metro Center, Six Corners, Four Corners, and Forest Park, with one census block in South End having the highest density of 125 individuals per hectare. Fast food locations are common along major roads and shopping plazas, and are distributed throughout the densest areas of the city. Supermarkets also follow major roads and shopping plazas, but are not as common in the denser neighborhoods. Presumably, neighborhoods with a larger population could support stores that offer

basic necessities, such as fresh food. However, as evinced by this map, locations of large supermarkets are not based on population density. While major roads and plazas have larger parcels of land for chains to buy and build upon, fast food locations within the city find ways of buying and using smaller parcels within dense areas. More density means more customers. Individuals living within the densest areas of Springfield have an easier time accessing poor-quality foods than fresh, nutritious options. This is exacerbated by the fact that many households in these neighborhoods also do not own cars.

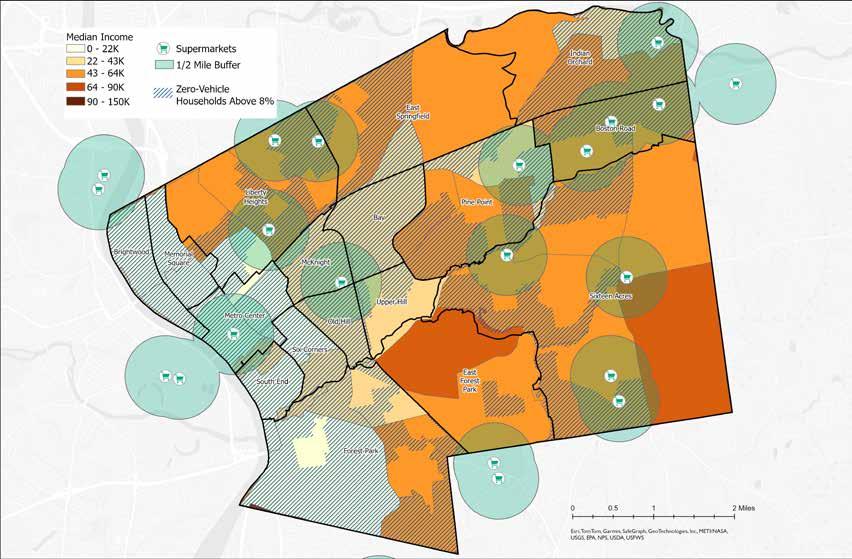

Source: US Census: Median Household Income (2020), Supermarket input points sourced from Google Maps (2024)

This map uses income and ease of access to large supermarkets as food access indicators. There are different ways to define low income and low access. This map uses similar criteria as that used to produce the USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas (formerly the Food Desert Report). The Atlas uses one of three ways to determine low income: 1) the tract’s poverty rate is 20% or greater; 2) the tract’s medium family income is less than or equal to 80% of the state-wide median family income; or 3) the tract is in a metropolitan area and has a median family income less than or equal to 80% of the metropolitan area’s median

family income (“Food Access Research Atlas Interactive Guide”).

Since using 80% of the median income in the metropolitan area would misrepresent income challenges in the city, for this map the lowincome census tract is one where the median family income is less than or equal to 80% of the Commonwealth’s median family income. In 2020, the median household income for Massachusetts was $84,385 (datausa.io/ profile/geo/massachusetts). Using 80% of this number as a reference, all of Springfield except for the darkest orange tracts—one in the easternmost section of Sixteen Acres and

one in the East Forest Park neighborhood— qualifies as low income (i.e., less than $67,500). Access to the nearest supermarket is represented by a half-mile buffer, which corresponds to a ten-to fifteen-minute walk to the store. Combining this information with the low vehicle access map shows that the neighborhoods that have the most limited means of accessing food include Brightwood, Memorial Square, Bay, Six Corners, South End, and Forest Park (which is a bit of an anomaly because much of the Forest Park tract is a City-owned park and sparsely populated).

“A lack of access to quality food sources and thus adequate nutrition has been a central cause of diminished health in the urban poor, and this reduced access has constrained choices and changed behavior over generations. Consequently, poor urban health is as much linked to 20th century urban history as it is to individual, behavioral causes.”

-Elizabeth Eisenhauer, “In Poor Health: Supermarket Redlining and Urban Nutrition”

This American’s Food Basket is located at 790 State Street, Springfield. It is the only grocery store serving the four neighborhoods of Mason Square. America’s Food Basket is a Lake City, New York-based regional

cooperative with forty-seven stores located in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island. The stores vary in size from 5,000 to 20,000 square feet (Webber 2016).

Source: Gardening the Community

Urban agriculture is an umbrella term that describes a range of food-growing practices, including the cultivation, processing, marketing, and distribution of food in urban areas, from backyard gardens to urban farms.

While urban agriculture has many positive effects, access to land ownership and stewardship has been historically and actively denied to specific racial and ethnic groups within the United States, limiting these groups’ ability to enjoy such benefits. Black individuals especially have endured centuries of racist policies and under resourcing, contributing to Black farmers making up only 1% of all farmers in America (Gripper 2020). Ensuring members of minority racial and ethnic groups the ability to farm can play a role in healing historical scars related to land access.

“Many Black urban communities have kept in touch with their agricultural roots, establishing farms and gardens throughout the United States. Black people have ancestral ties to this land—to caring for it, nurturing it, loving it, and allowing it to heal our communities and us—and we have faced immeasurable discriminatory practices and policies as we sought to reclaim and live in relationship with the land.”

-Dr. Ashley Gripper, assistant professor of Community Health and PreventionAn obvious benefit of urban agriculture is increased access to fresh, unprocessed foods that support and strengthen the body. In addition, urban agriculture fosters wellbeing further by encouraging active living and improving mental health.

Diet is a powerful determinant of the prevalence of chronic illness, subsequent symptoms, and overall quality of life (Entwistle et al. 2021). The freshness of food, determined by the time since harvest, plays a part in determining its nutritional value, as vitamins naturally degrade throughout the process of transportation, retail, and storage (Kuhnle and Niranjan 2023). Buying locally or growing one’s own food can help ensure minimal nutrient loss, as foods move from farm to plate quicker than in conventional retail.

However, the type of food consumed has much more influence in determining an individual’s level of nutrition, and subsequent longevity (Boston 2023). A 2021 study found that individuals with diets higher in whole plant foods—which entails unprocessed fruits and vegetables—have higher longevity compared to those with other types of diets; this was especially true when compared to a more standard “western” diet—heavily composed of red meat, artificial sugars, and oils—which was associated with the lowest life expectancy of all diets studied (Entwistle et al. 2021). Such processed foods, which are commonly sold in convenience stores and fast-food restaurants, tend to be high in LDL cholesterol and saturated fatty acids, and contain simple carbohydrates. Meanwhile,

fruit and vegetables contain none of these negative compounds, and instead are high in fiber, micronutrients, antioxidants, and unsaturated fatty acids. These compounds have been found to naturally ameliorate some common chronic illnesses, such as type 2 diabetes (Kim and Giovannuci 2022).

The American Heart Association promotes increased consumption of fruit and vegetables of all kinds—fresh, frozen, canned, or dried— within the average American diet, especially as a method for combating heart disease, the leading chronic but preventable illness in the country. The association has promoted gardening, including community gardening, as a means of increasing access to and appreciation for fresh produce (Homegrown Foods). Getting children involved in growing their own food has also been found to increase the amount of produce they eat, along with what kinds of foods they find palatable, which can encourage healthy development and lifelong habits (Davis et al. 2021).

Dr. Ashley Gripper, an assistant professor in Community Health and Prevention, summarizes the power of urban agriculture when she states, “growers and activists understand that [...] a major key to population health and collective healing is having control over what goes in our bodies” (2020).

Massachusetts’ Food is Medicine initiative focuses on the potential of food in improving public health. The state plan believes that “by addressing nutritional needs within the context of health care, Food is Medicine interventions play an important role in preventing and/or managing many of the chronic conditions that drive health care costs.”

-MA Food is Medicine State Plan, June 2019

Just thirty minutes of gardening several times a week can produce noticeable health benefits—even just a half-hour of weeding can burn one-hundred and eighty calories. All the major muscle groups are used throughout gardening’s varied activities, many of which do not apply excess pressure to joints and bones as do other exercises, such as jogging (Ross). Additionally, gardening is a self-paced activity that can be made easier with the use of tools. This can make exercise possible for individuals with a wide range of physical abilities, ages, and health conditions such as asthma. Managing plants also innately requires frequent, sometimes daily, care, which can encourage consistent movement regimes in individuals.

When community gardens and farmers markets are within walking distance, as they often are, they can promote movement for many people in the area. Additionally, weather and temperature permitting, the act of going outside offers benefits, such as increased vitamin D.

Gardening has been linked to not only increased physical wellbeing, but also mental wellbeing. Gardens, along with other green spaces, have been found to decrease stress hormones in individuals, even when just sitting within the space (Gupta 2022). Within urban environments, where green space is often lacking, having spaces of respite with trees, gardens, and other greenery can help create a healthy state of mind for residents. Additionally, gardens provide an opportunity to create meaningful and positive humannature interactions (Soga et al. 2017), which can be especially soothing in contemporary times, where negative associations between humans and nature, and general climateanxiety, is often abundant.

Gardening is also a great activity for supporting the mental wellbeing of all ages, but especially for children and older adults. Children are given a space to play, explore, and learn, whether that be through observing the tricks of experienced gardeners, discovering a new bug never seen before, or by tasting and being accustomed to new foods and flavors. For older adults, gardening

While backyard gardens promote increased produce consumption and exercise, community gardens, farms, and farmers markets further foster personal wellbeing by strengthening connections between people, cultures, and the land.

There are few gathering spaces where people of all ages, ethnicities, and other backgrounds feel equally welcomed and encouraged to meet, collaborate, and share with other individuals on the same land. Community gardens and farms offer such a space. This interpersonal exchange can be very fulfilling for youth, who are currently spending on average only four to seven minutes of unstructured outdoor play per day (Marshall). Community gardens can provide a safe space for children to play outdoors, learn about natural processes, and discover new foods and how they are grown—this is especially meaningful within urban environments, which may contain little open space. Additionally, deep generational gaps currently exist due to many factors such as the loss of extended family units, increased migration, and overabundant screen time (Schmidt-Hertha 2014). Growing food is one way to preserve intergenerational interactions and knowledge, both between families and across communities, as the practice is frequently taught through listening to, observing, and mimicking experienced gardeners. In reality, knowledge is not only passed from elder to child, but is also a life-long process involving learning from all types of individuals. Akin to the sharing of information, community gardens and farms also allow for the sharing of experiences and food between individuals as they share both work and yields.

Farmers markets, especially due to their social element, attract many families and individuals into a shared space to enjoy a variety of vendors, music, and community. The public is also given the chance to meet and talk with the farmers growing their food,

and build interpersonal connections with the people creating the foundation of their local food system.

Food hubs are historically a way for individuals to practice cultural expression and preserve culturally relevant crops, recipes, and farming practices. Oftentimes, many commercial-chain supermarkets sell products most likely to appeal to the largest consumer base, so it can be difficult to find foods within these stores that the average American does not buy, regardless of the food’s popularity in other countries. Thus, if the local climate allows for it, specific crop varieties not sold in stores can be planted, harvested, and enjoyed within community gardens and farms. Even if a crop cannot be grown due to climate, greenhouses may offer a solution to growing food common in warmer areas of the world. Uncommon crop varieties provide the opportunity for members of the same community garden or farm to experience new foods and expand their own taste palette or garden.

While experiencing the richness of other cultures is one benefit of community gardening, meeting other members of the same culture can also be extremely fulfilling, especially if individuals face English isolation within a neighborhood. Farming may be a very meaningful practice for new arrivals, especially those who were already growing food in their country or place of origin. Maintaining the habit of farming while in a new land is a powerful way of easing the

sense of cultural identity loss common in immigrants and new arrival. In one qualitative study interviewing refugees who garden in communal plots, one immigrant is described as “relieved to have a land here to dig. He believes it was very important for an African person, if they didn’t go to school, which majority didn’t, they had to be a farmer. So the closeness was very good, the bond between the human and the soil was of great importance. … This is the only place here for him to dig so that is why it is important for him” (Harris 2014).

Farmers markets may similarly fill a cultural niche if they offer culturally relevant foods, especially if the vendor is bilingual and can welcome and interact with non-fluent English speakers. Having diverse vendors can expose the public to new foods, and allow individuals of the same background to meet within a shared space, and having affordable vendors with consistent prices, clear advertising, and bilingual signage allows the market to be more accessible for a wider audience.

Community gardens, farms, and farmers markets are not only able to deepen interpersonal and cultural relationships, but can also foster a greater connection, responsibility, and care for the land one lives on, as referenced with the African refugee’s newfound relationship with American land. Communal gardens and farms are especially important within urban areas, as many individuals rent and do not have access to private land for food production. A sense of belonging to land is partially generated through the stewardship aspect of gardening, where humans and natural processes work together towards a shared goal. This positive exchange can be meaningful, especially when many individuals perceive urban environments as the antithesis of nature. Growing food can also expose individuals to the growth and importance of other organisms, such as crop plants or pollinators. Similarly, relying on seasonal food grown by oneself or local farmers can allow individuals to become more in-tune to changes in seasons and weather (Lin 2018). Farmers markets have the added benefit of allowing the public to gain a greater understanding of where their food comes from, as farmers are able to explain what varieties they grow, as well as what practices they use to grow them.

Nordica Street Farm is a CSA and farm stand in northern Springfield that is developing a communal medicinal herb garden, stewarded by women of the surrounding community and available to any member of the public.

-Anne Richmond, founder of Nordica Street Community Farm

States and municipalities across the U.S. are assessing their resiliency in light of human-caused climate change, which is resulting in higher temperatures, increased flooding, and more unpredictable weather. Urban agriculture, which is considered a type of green infrastructure, can be employed to increase climate and weather resiliency (Dekissa 2021).

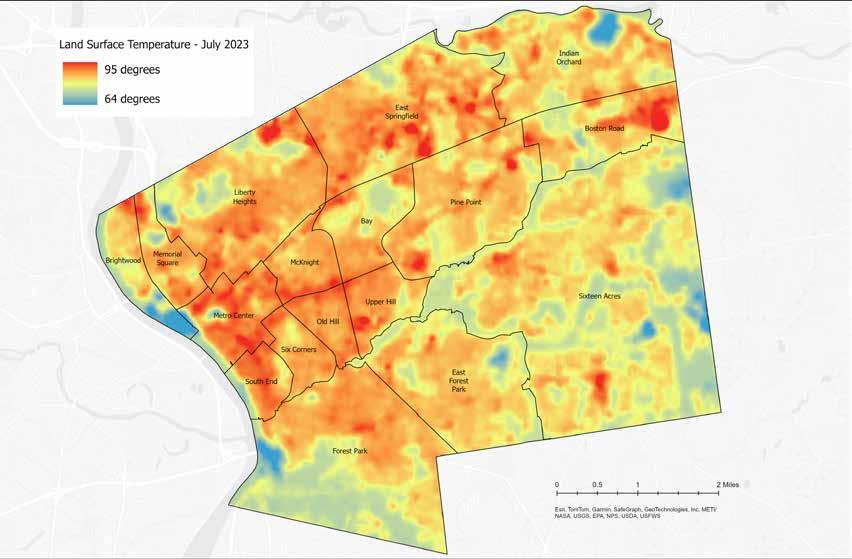

The increasing severity of heat waves and overall temperatures can have a negative impact on human health and general wellbeing. Extreme temperatures cause the body to overheat, causing heat stroke, and also increase the chance of heart attack or respiratory diseases like pneumonia. Each year more than 1,300 deaths in the U.S. can be attributed to extreme heat, and that is likely an undercount (“Climate Change Indicators”).

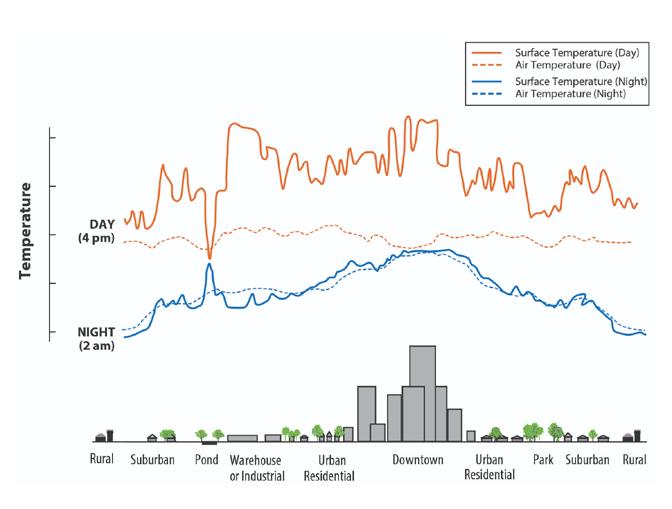

Urban areas are particularly vulnerable to sustained elevated temperatures, since the land is covered by large swaths of impervious surfaces such as sidewalks, rooftops, and buildings made of concrete, asphalt, and metal. Concurrently, urban areas tend to offer low tree canopy coverage. As a result, these places become “heat islands” compared to

outlying suburban or rural areas. Some effects of urban heat islands (UHI) include increased energy consumption (especially through air conditioning), air pollutants and particulate matter, and smog and ozone formation (Humanaida 2023).

The addition of green space within urban areas is one effective strategy to combat the UHI effect. Plants decrease temperatures through providing shade, as vegetative cover reduces the amount of sunlight that reaches the ground and buildings, thereby lowering surface temperatures. Additionally, air is cooled through evapotranspiration, where water droplets collect on the underside of leaves and absorb heat before becoming water vapor. Plants also improve air quality by acting as natural air filters, absorbing carbon dioxide and other pollutants (“How Does Urban Agriculture” 2023).

To help absorb stormwater runoff, Springfield’s Climate Action and Resilience Plan (CARP) suggests the use of small agricultural plots that provide permeable surfaces, along with other sorts of green infrastructure like bioswales and rain gardens.

-City of Springfield CARP, 2017

Within urban environments—which contain abundant concrete, asphalt, compacted dirt, and other impervious surfaces—minimal rainwater is typically absorbed into the ground compared to less developed areas. Such impervious areas are considered to have high runoff, which contributes greatly to urban flooding events. These events are predicted to only become more extreme as climate change progresses and precipitation events become more severe and unpredictable (Monier and Gao 2015). Flood events can be economically catastrophic, as they can damage infrastructure–including roads, buildings, underground pipes, and equipment–as well as topography–where soils, fertilizers, and possible contaminants are moved (“Torrential Flooding”).

Most rainwater that does not become absorbed into the ground enters the sewage system. While much of this water becomes treated, the sewer infrastructure within many older U.S. cities is unable to accommodate high water inputs that can accumulate during major storm events. To avoid backed-up or leaking pipes, these sewer systems combine both untreated street runoff and household waste and overflow into local water bodies, severely harming natural habitats and human health (Zhu 2021).

One way to reduce combined sewer overflow (CSO) events is to reduce the amount of stormwater entering a sewer system in the first place, such as through adding green infrastructure. Such features can include trees, roadside rain gardens, and green spaces, such as urban agriculture plots (Deksissa 2021). The greater the amount of vegetation, the greater the land’s ability to absorb water. In this regard, revegetation of any sort can improve urban ecosystem

resilience to extreme precipitation, reducing flood risk and water runoff. A study in Beijing demonstrated that the amount of runoff reduced by urban green spaces “resulted in benefits equivalent of 75% of flood maintenance cost” (Humaida 2023).

According to the USGS, carbon sequestration is “the process of capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide. It is one method of reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere with the goal of reducing global climate change” (USGS: Carbon Sequestration). As plants grow, they develop biomass primarily by storing atmospheric carbon within their leaves, stems, and roots. As these parts naturally decay overtime, the carbon stored within them becomes part of the organic matter composition of the surrounding soil. Through this process, carbon is moved from the air and into soil, where it is “stored.” Agriculture in the form of community gardens, community farms, and urban orchards can be an effective strategy for carbon sequestration within urban environments, especially if plant materials are composted and used on site (Barnard). The farming practices found to promote more carbon sequestration compared to other methods include cover cropping, reduced tillage, and crop rotation. Additionally, woody perennial crops generally hold more biomass, and thus carbon, than annual crops do (Massachusetts 2022).

Conventional economic development models typically focus on direct financial gain, which can involve generating wage employment, attracting outside capital investment, and increasing tax revenues. However, urban agriculture can contribute to the fiscal health of a municipality within this model and beyond, such as through strengthening local economies, reducing expenses, and promoting quality of life.

The economic benefits of urban agriculture can be directly seen in farmers markets and farm stands, where local farmers are given a dedicated space to directly sell their goods to consumers; this can be very beneficial for vendors amidst the larger commercial farming system that big agricultural chains typically dominate. Also, unlike major food chains, local farmers are able to directly contribute to the economy they work in and provide for.

Gardening the Community (GTC) has a strong focus on youth development, where “youth receive a stipend and are taught principles of urban sustainable living and urban agriculture [and] also bring food home to their families.”

-GTC Website

In regards to community farms, many youthfocused programs and organizations are able to pay teenagers who take on agricultural work, which can introduce and develop their finance skills, start their personal investment, or supplement their family’s income. These financial opportunities can be immensely beneficial in food-insecure communities. Alongside such support, engaging youth in urban agriculture can develop their knowledge of horticulture and nutrition, as well as build essential social and personal skills. Similarly, urban farms can offer fulltime agricultural work opportunities, which are often scarce in highly urbanized areas. The ample number of vacant lots, many of which have no plans for immediate development, is a ripe opportunity to create such positions.

Even before youth enter the workforce, their future careers can be supported by improving their public education environment. Numerous studies have connected academic performance with the quality of food consumed by students, where children that are fed and fueled by nutritious foods are more focused and present in the classroom (Bleiweiss-Sande et al. 2020). Feeding kids is part of economic development, as improved academic performance may lead more individuals to attend higher education and attain higher-paying jobs.

As detailed in previous sections, urban agriculture has the potential to positively influence physical, social, and environmental health. Many of these services have financial weight; for instance, by promoting citizen health and stormwater catchment, the costs of healthcare and infrastructure services, respectively, can be reduced. Although sometimes not obvious, urban agriculture can promote fiscal health through preventing municipal long-term costs.

The primary goal of economic development is not generating wealth or avoiding unnecessary costs for the sake of it, but rather to benefit the community through improving the quality of life of individuals. As mentioned, urban agriculture can directly contribute to quality of life by improving physical and mental health through nutrition, exercise, and green space; creating spaces for convivial social engagement and intergenerational and cross-cultural learning; and cooling hot cities, cleaning air and water, and storing carbon. Urban agriculture becomes a strategy of directly providing conditions for the improvement of quality of life for individuals and communities—which is the goal of economic development—while skipping over conventional methods that require direct economic growth.

Source: Daniella Portal

Source: Daniella Portal

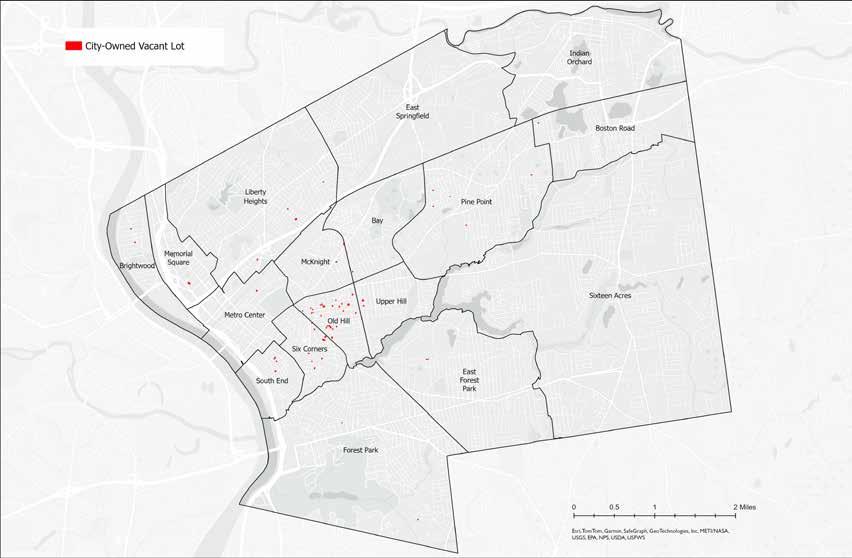

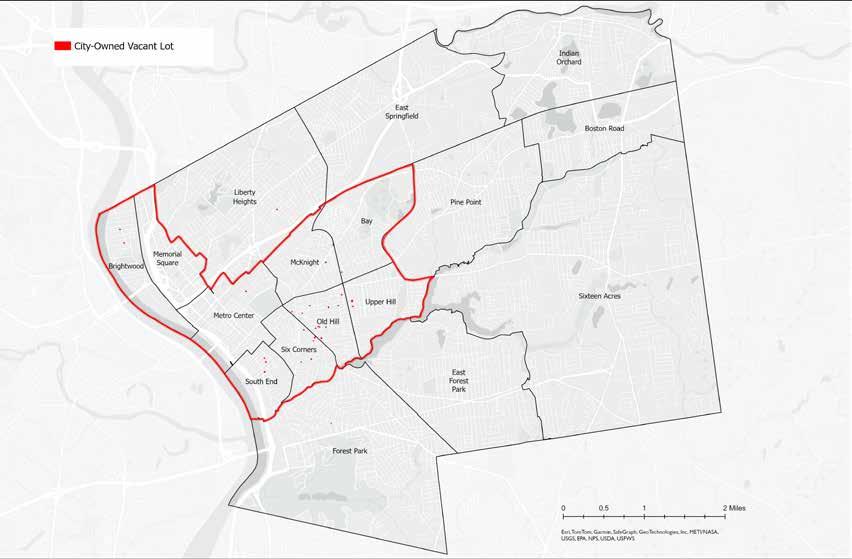

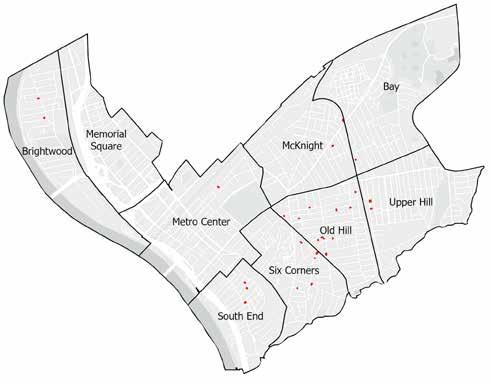

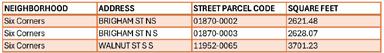

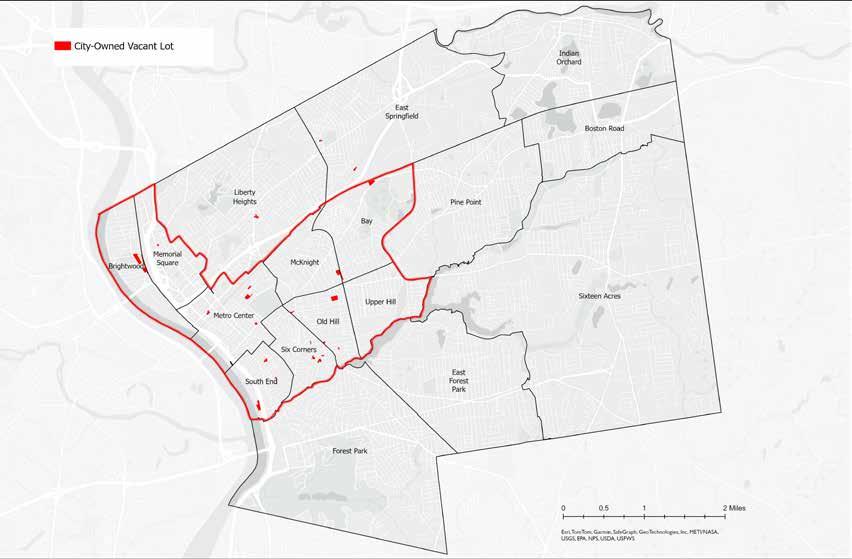

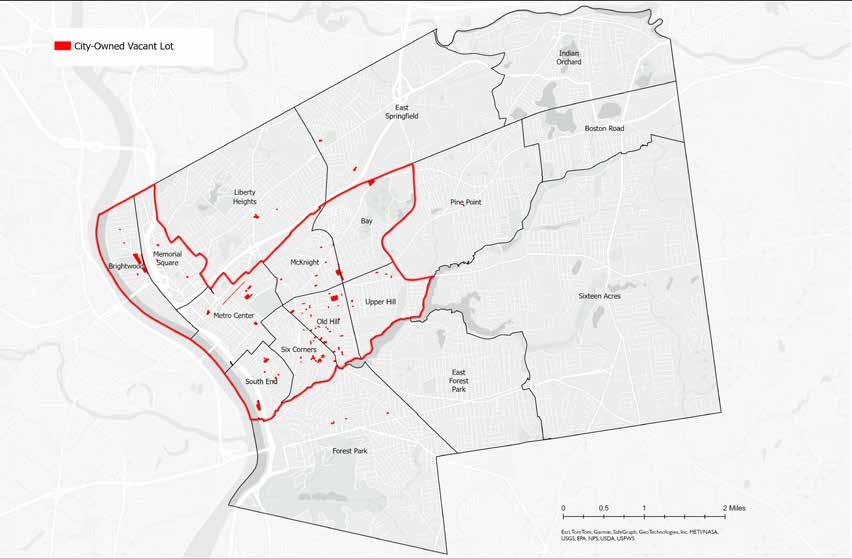

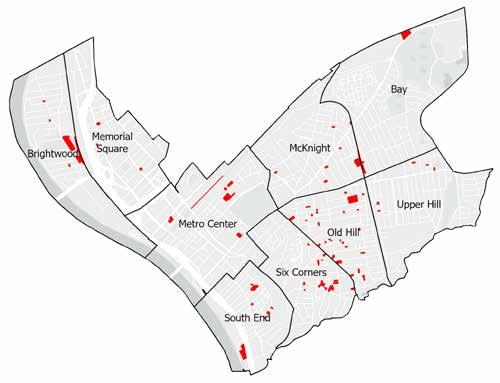

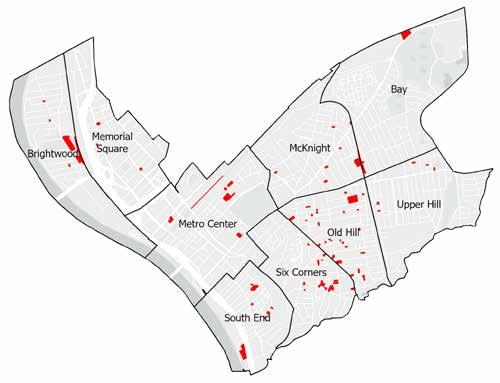

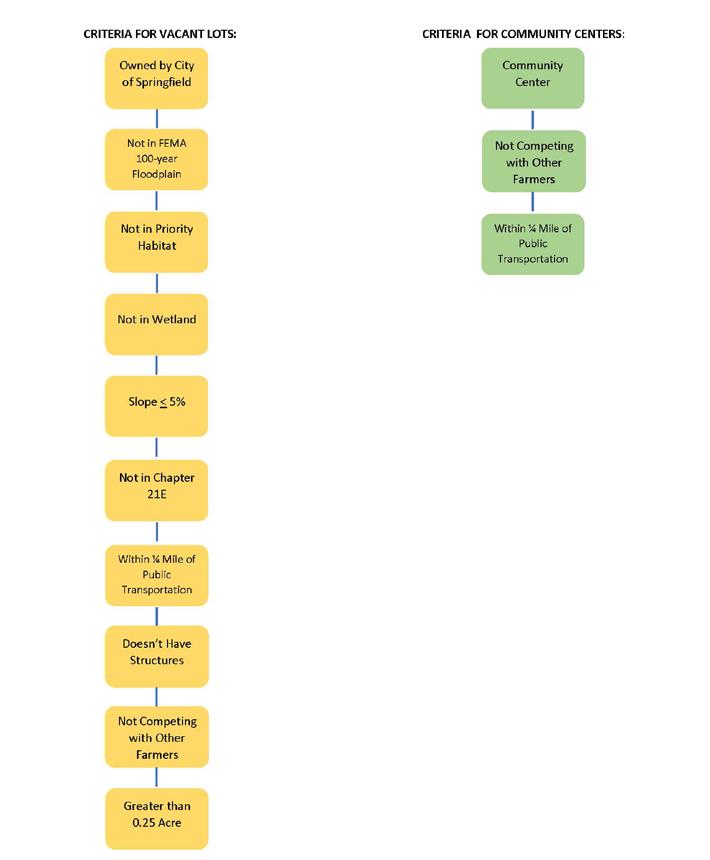

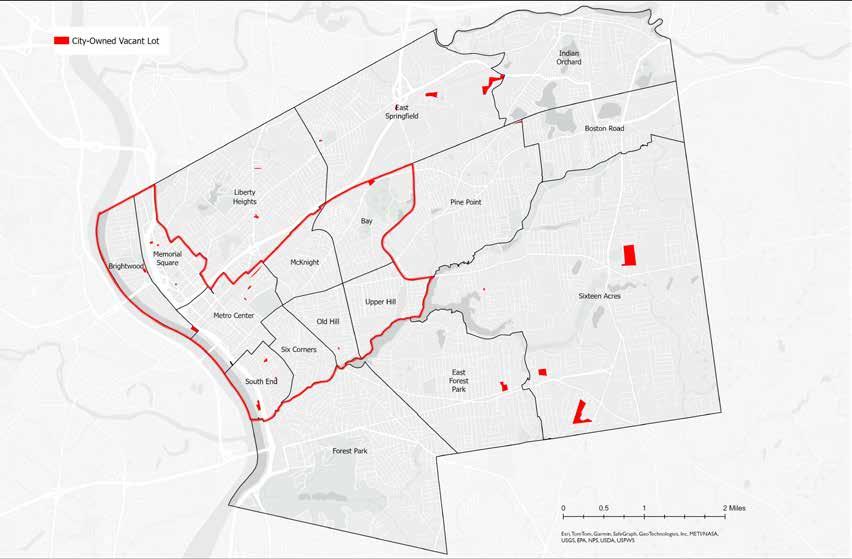

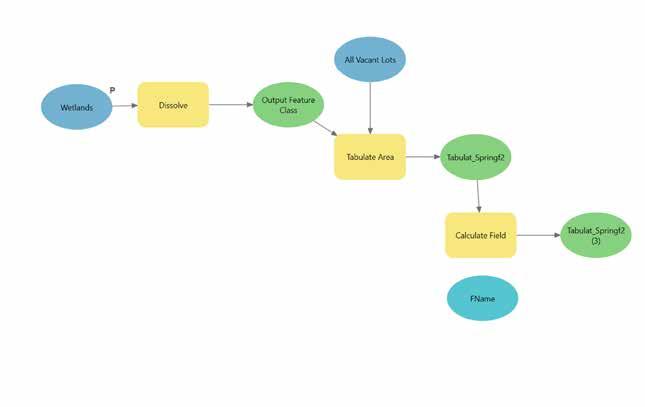

This section of the report demonstrates a process for identifying which City-owned vacant lots are the most suitable for food production (i.e., community gardens, community farms, or urban orchards). Four tiers of criteria, informed by environmental restrictions, feedback from the Springfield Food Policy Council (SFPC), the City, and processes of past reports with similar goals, such as Food in the City (2014), and A Spatial Analysis Supporting Holyoke’s Food System (2022), are used to reduce the number of City-owned vacant lots to a short list of recommended parcels.

Tier 1A and 1B criteria are both mappable and will be used to eliminate sites that do not meet the criteria outlined. Tier 1A criteria include environmental restrictions and barriers that might make a vacant lot unusable without significant alteration. If a site meets all of the criteria presented in Tier 1A, it will move on to the Tier 1B criteria. Tier 1B criteria are also mappable, but focus more on ease of use and safety of the site, as well as the size of the site for different food production uses. Tier 2 criteria are mappable and consider public health criteria as an overlay to the sites remaining after Tier 1B. This tier of criteria helps create a focus area of the neighborhoods that would most benefit from increased access to food production sites. All of the sites remaining in the focus area determined from Tier 2 then move on to Tier 3. Tier 3 includes criteria that are not always necessary for food production, but increase the ease of use of the site. Tier 3 also includes criteria that require further ground-truthing, and were not addressed in this report due to time constraints. Lots meeting all of the tiered criteria are deemed “most suitable” for food production according to the model. However, any lot meeting Tier 1A criteria may be suitable. All lots identified in the model require

further ground-truthing to determine suitability. The rationales for choosing each of the criteria found in Tier 1A and 1B are as follows.

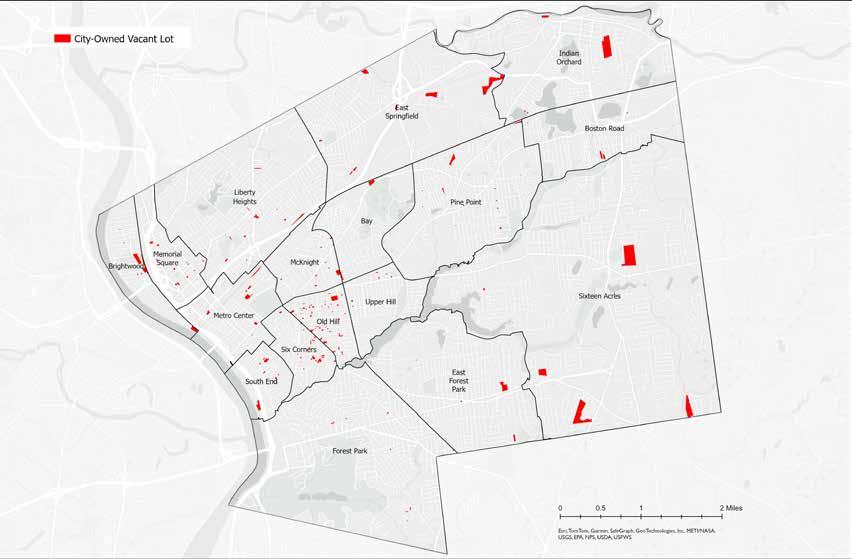

• Owned by the City of Springfield: As outlined by SFPC, identifying and communicating with the owners of privately owned lots can be a difficult process, making land transfers for urban agriculture timeintensive and complicated. For this reason, the model prioritizes City-owned vacant lots.

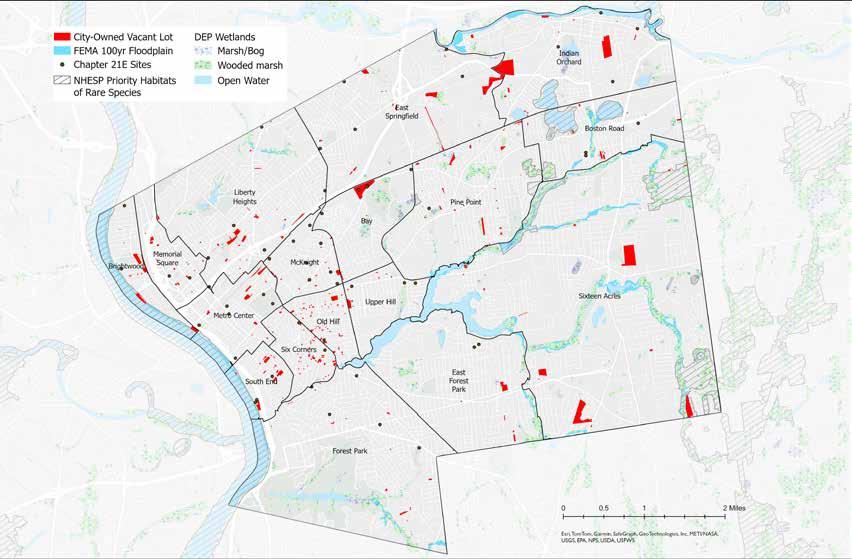

• Not in FEMA 100-year floodplain: Given that climate change may increase flood frequency, the model eliminates lots within the 100-year floodplain designated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Elimination of these sites helps to prioritize lots with a lower risk of flooding, making them enjoyable and usable as food production sites for years to come.

• Not in NHESP priority habitat: To avoid disturbing or destroying important habitat for agriculture use, the model eliminates lots within priority habitat areas identified by the National Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP).

• Not in a wetland: Many delineated wetlands are protected by both federal and state laws that require buffer zones to preclude certain activities. Although in some cases agriculture may be permitted in wetland buffers and wetlands themselves, obtaining a permit to do so can be a time-intensive process. The Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) wetlands layer used in this analysis does not show all current delineated wetlands, only likely wetland areas.

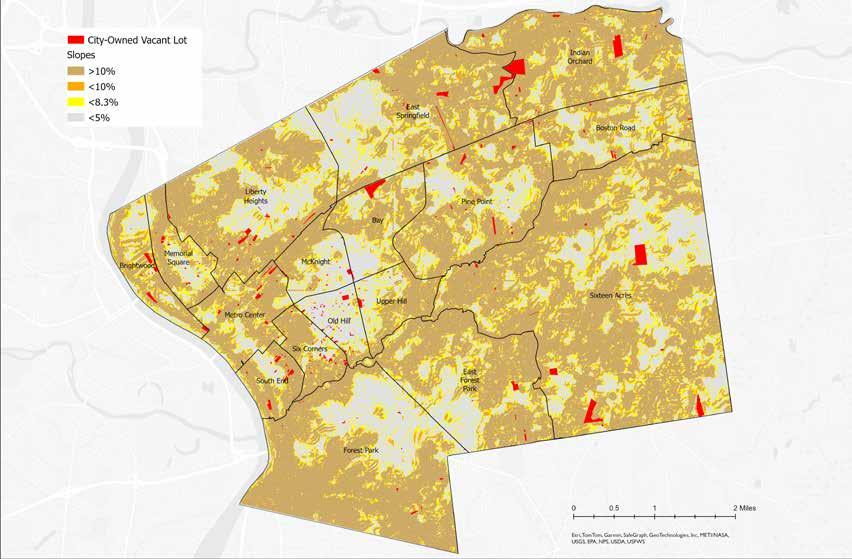

• Slope is no more than 5%: It is important that these sites are accessible to people with different ability levels. This criterion is <5%, as this is generally regarded as the maximum accessible slope for people using wheelchairs when there are no handrails in place. This model recognizes that food can be grown on slopes steeper than 5% and that grading can be used to achieve a desired slope, and therefore does not eliminate sites that have slopes higher than 5%, but rather selects sites with at least 500 square feet of accessible slopes.

• Not a Tier Classified Chapter 21E Site: Chapter 21E refers to the Massachusetts Oil and Hazardous Material Release Prevention and Response Act. Property that is designated by the Commonwealth as “Chapter 21E” has been identified as hazardous and has not yet undergone sufficient remediation. Because the contaminated land can pose a significant risk to human health and the environment, it should not be used for food production. Examples of Tier 1 imminent hazard contaminants include cyanide, petroleum, and lead.

• Not zoned “Commercial-P”: Lands that are designated by the City zoning code as commercial-P are sites used for the primary purpose of parking. Not all parking lots are commercial-P, as a parcel hosting both a business and a parking lot would be zoned for business. However, all commercial-P sites are parking lots; for example, a business can obtain an adjacent parcel for the sole purpose of hosting or expanding a parking lot if the lot is designated commercial-P. Parking lots leach chemicals and heavy metals into the soil underneath them over time, and are also consistently exposed to pollutants from vehicles, making them unfit for food production (Azadgoleh et al 2022). City zoning

prohibits any food production use on commercial-P sites.

• Doesn’t have structures: Feedback from the Department of Parks, Buildings, and Recreation Management informed the decision to eliminate lots with structures on them, as these are lots that are more likely to be used for future housing use.

• Has permeable surface: Similarly to the criteria for slopes, the model selects parcels with at least 500 square feet of permeable surface on them. Although it is possible to grow food in raised beds on impervious surfaces or remove impervious surfaces altogether to create garden beds, the model prioritizes permeable surfaces to increase the ease of use for establishing food production.

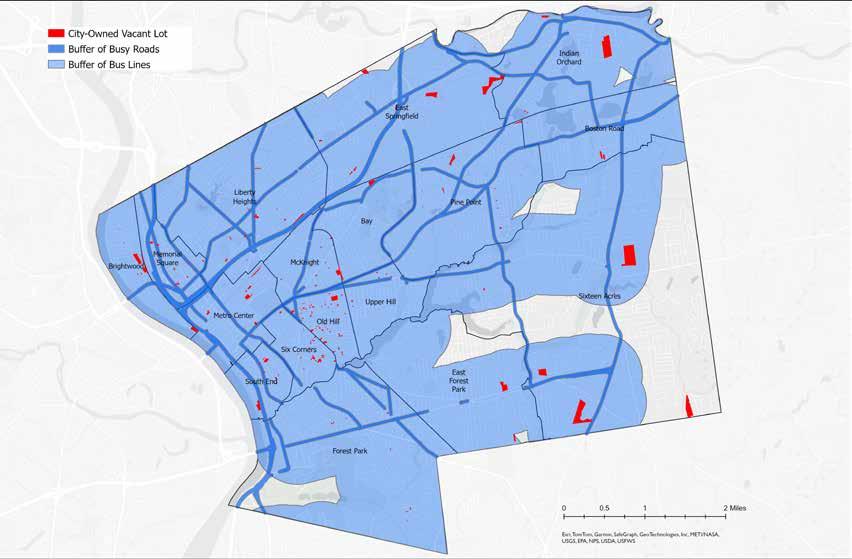

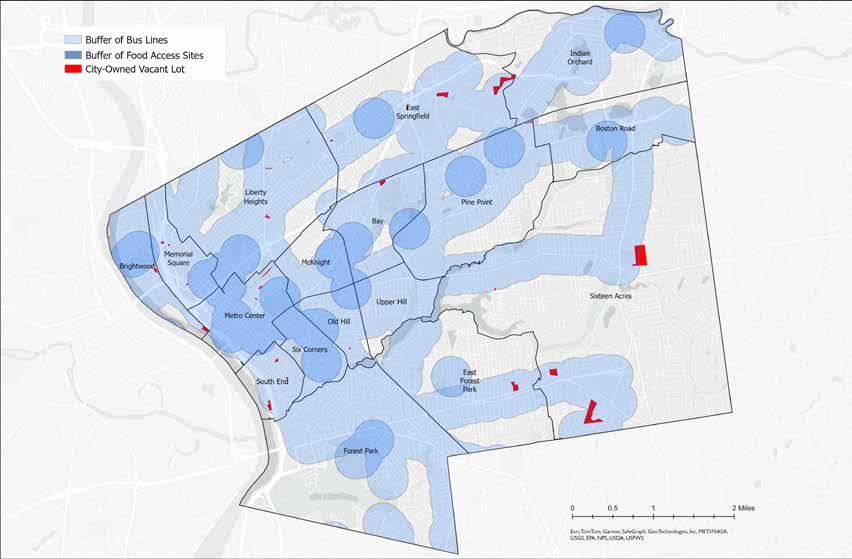

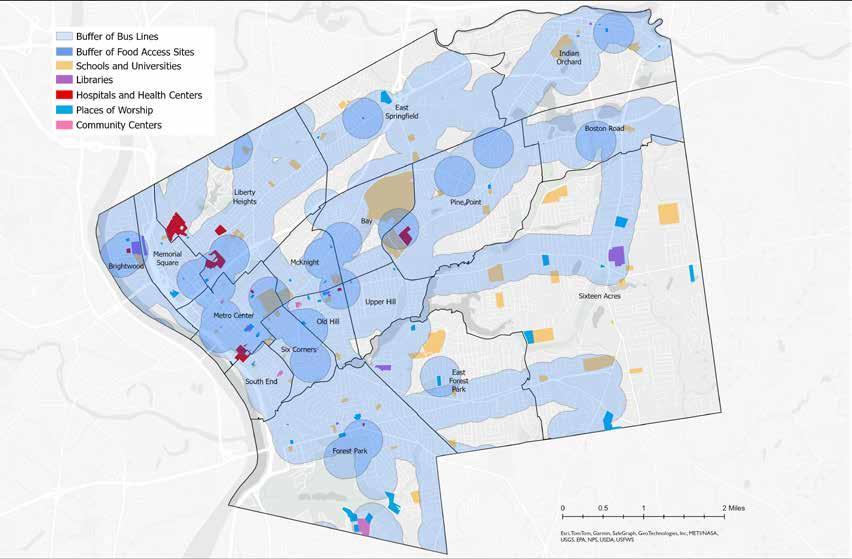

• Located within a half-mile of public transportation: Lots that are within walking distance to public transportation, which includes the PVTA bus lines in Springfield, are selected by the model in order to make them accessible to users without vehicle access.

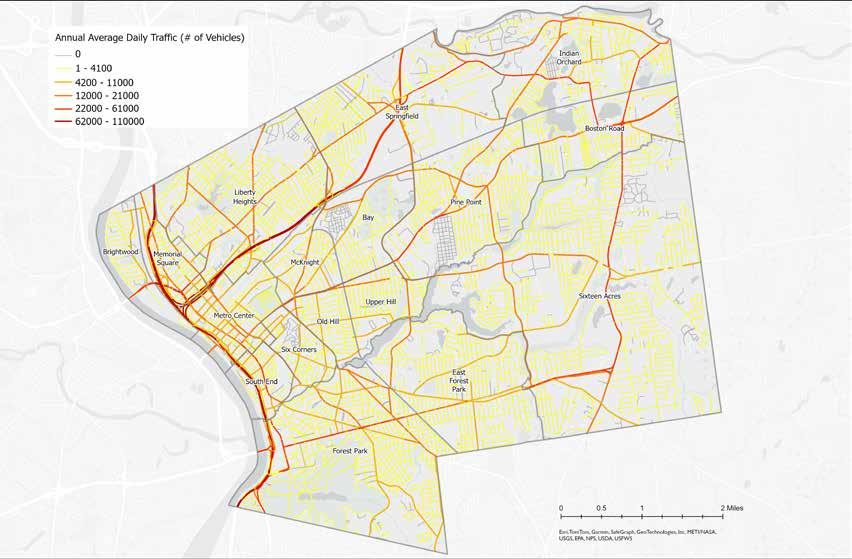

• Not located within 100 feet of a busy street: High numbers of vehicles using major roads generates increased noise pollution as well as increased levels of fine particulate matter in the air, lowering air quality. Busy roads can also pose a threat to pedestrians working on site or walking to and from a site. In order to reduce health risks associated with poor air quality and increase the overall safety of the site, the model applies a 100-foot buffer around any road seeing more than 15,000 cars a day. Lots located within this buffer zone are not considered for food production.

• Lot size: Community gardens, community farms, and urban orchards have different size requirements. Size requirements are drawn from the 2014 study, Food in the City. Lots identified for community gardens are less than 5,000 square feet, for community farms exceed a quarter acre, and for urban orchards exceed 1,000 square feet.

Methodology: Vacant Lot Suitability for Food Production

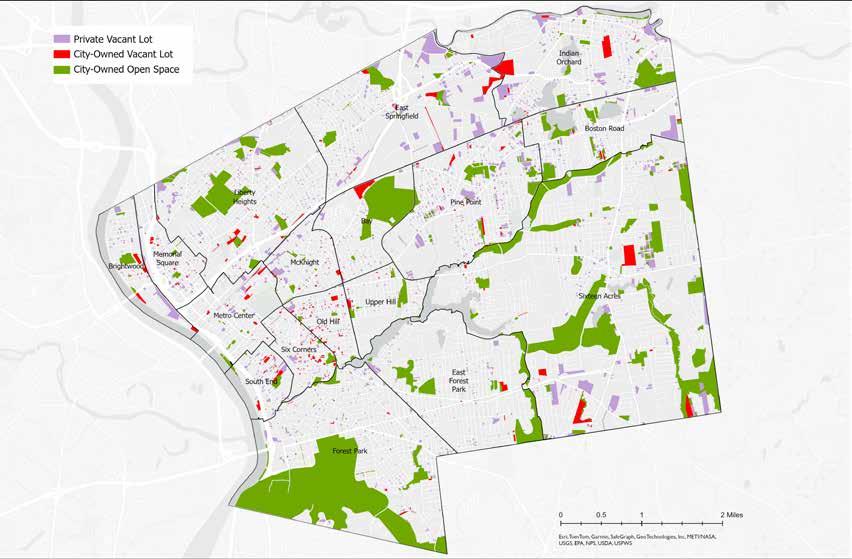

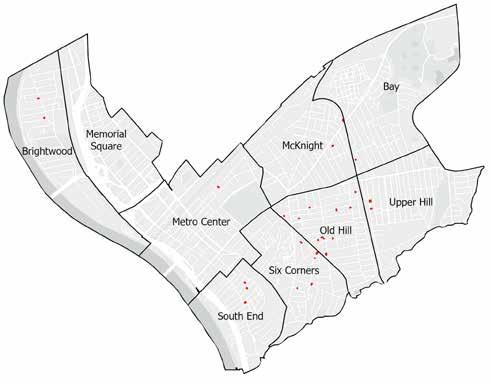

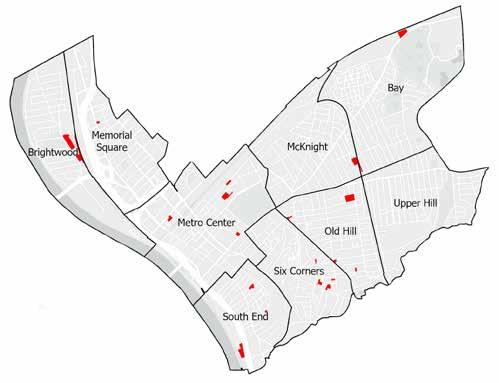

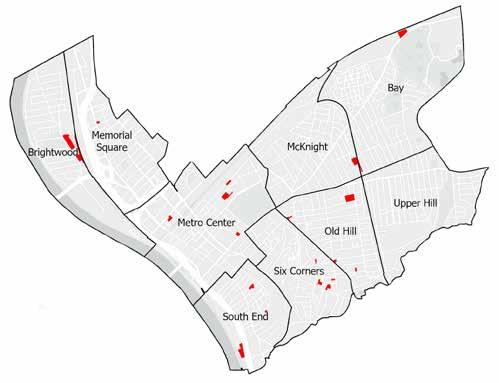

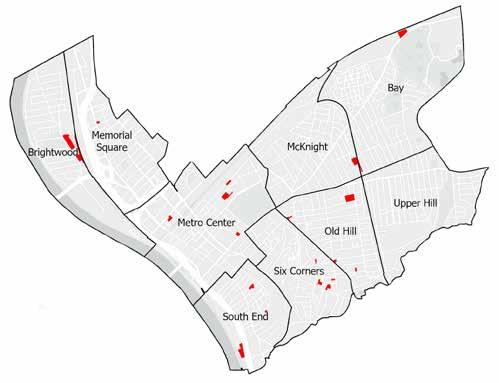

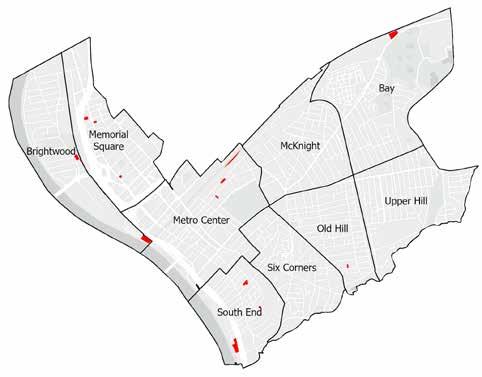

Source: MassGIS: Property Tax Parcels (2023)

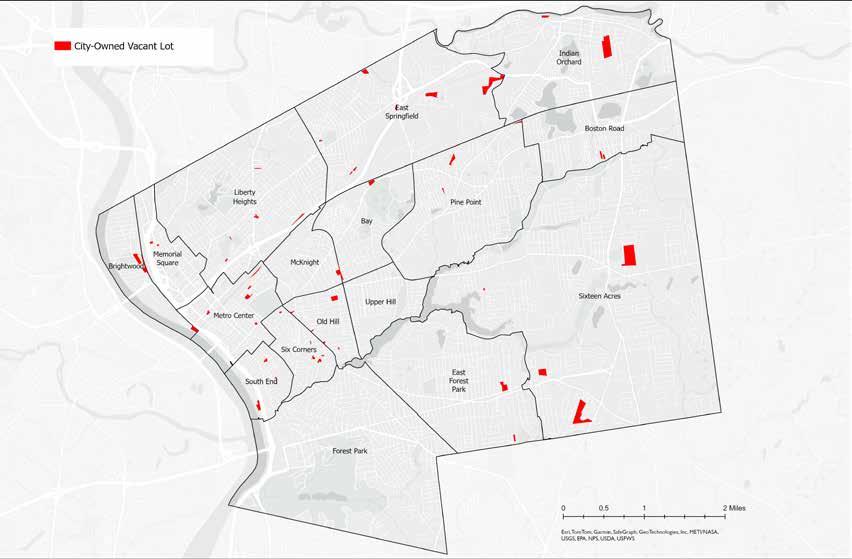

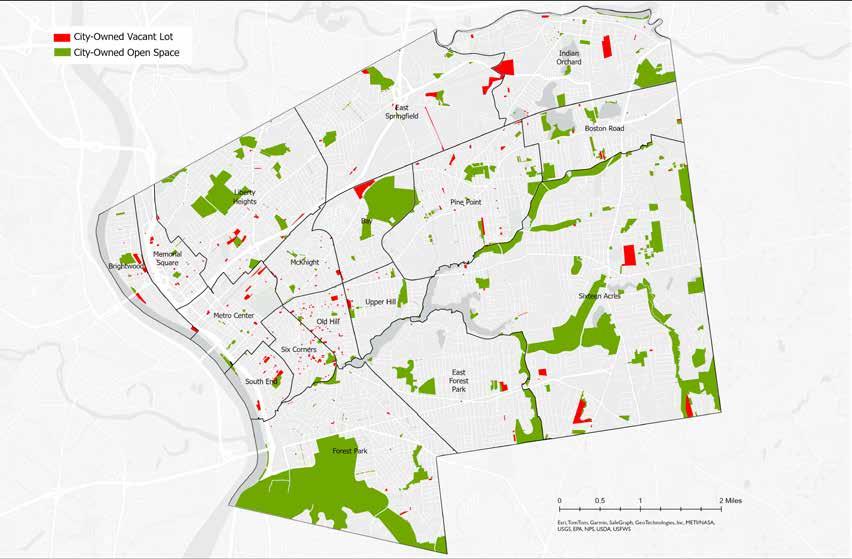

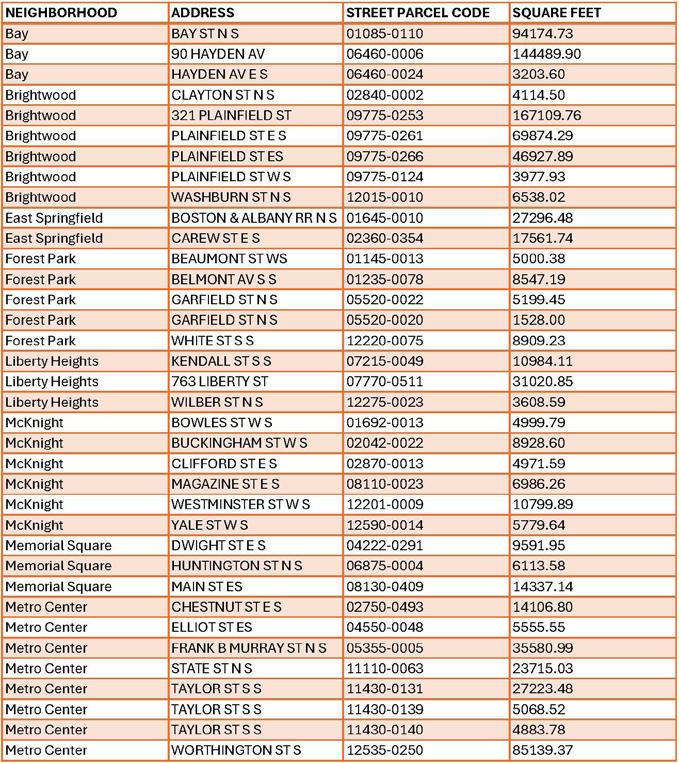

Vacant land in Springfield can be classified into three categories: privately-owned vacant lots, City-owned vacant lots, and City-owned open space. There are a total of 2,867 privately owned vacant lots, 486 City-owned vacant lots, and 478 parcels of City-owned open space across Springfield. City-owned open space is not necessarily vacant, but is considered undevelopable and can host a variety of uses, such as parks, sports fields, or cemeteries. The larger swaths of City-owned open space are in the eastern and northern parts of the city, as well as in Forest Park. Private and City-owned vacant lots are much smaller in size than the City-owned open space parcels, and are dispersed unevenly throughout the city.

Because City-owned open space can vary greatly in its use from parcel to parcel, certain parcels may be more compatible with urban agriculture than others. For example, a City park may be an appropriate location to host a farmers market or a community garden, but a sports field or a cemetery should not be used for urban agriculture. The larger size of the City-owned open space parcels allows for some flexibility, as particular portions of a parcel may be used for urban agriculture while the rest of the parcel maintains its intended use. However, because of the great variety in use of this land, the model does not assess City-owned open space parcels using the same tiered system of criteria mentioned prior.

Identifying and negotiating with the owners of privately-owned lots, as well as paying for the use of private land, can be a complicated process, making land transfers for urban agriculture time-intensive and potentially expensive. With these factors in consideration, the model does not assess privately owned vacant lots for food production either. In the pages that follow, the model only examines City-owned vacant lots in order to identify the lots that are most suitable for food production.

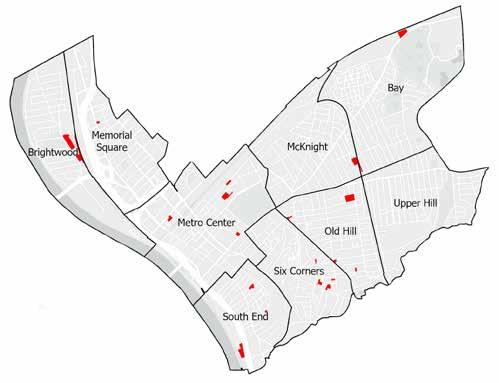

Source: MassGIS: FEMA National Flood Hazard (2023), NHESP Estimated Habitats of Rare Species (2021), MassDEP Wetlands (2017), Chapter 21E Tier Classified Sites (2024), Property Tax Parcels (2023)

Environmental factors such as the FEMA 100year floodplain, wetlands, hazardous or contaminated sites in Chapter 21E, and NHESP protected habitat prohibit or limit the use of land for food production. Looking at these environmental factors relative to all Cityowned vacant lots shows parcels that should be avoided for siting food production. Avoiding lots with environmental restrictions allows these important environmental areas to stay undisturbed, and minimizes physical obstacles to the establishment of food production. On sites where a portion of a lot intersects with

the flood zone, priority habitat, or a wetland, the model selects the site for consideration so long as there is at least 500 square feet of land that does not overlap with the environmental restriction. The portion of the land that is left over and does not interfere with the restriction may still be suitable for food production.

Source: MassGIS: Property Tax Parcels (2023), NOAA Data Access Viewer: Lidar (2015)

Following ADA standards, slopes on a solid and stable surface at 5% or less are accessible to people with varying ability levels, especially those with wheelchairs; slopes up to 8.3% are accessible when paths have a handrail. To ensure maximum accessibility, the model considers a slope of 5% or less as an accessible slope. Given that food can be grown on slopes steeper than 5%, and that grading can be used to achieve a desired slope in many cases, sites with slopes higher than 5% are not eliminated if they have at least 500 square feet of accessible slopes.

Source: MassGIS: Property Tax Parcels (2023)

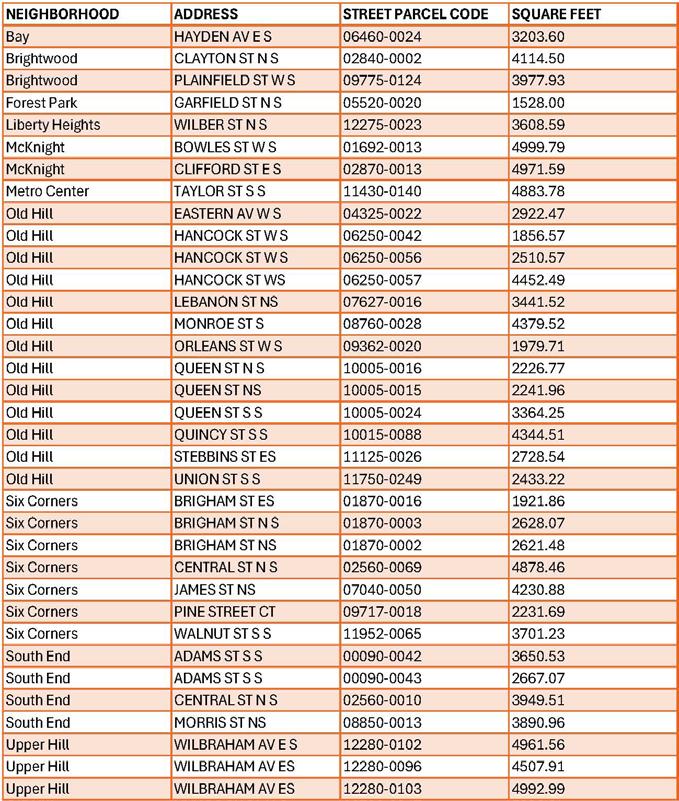

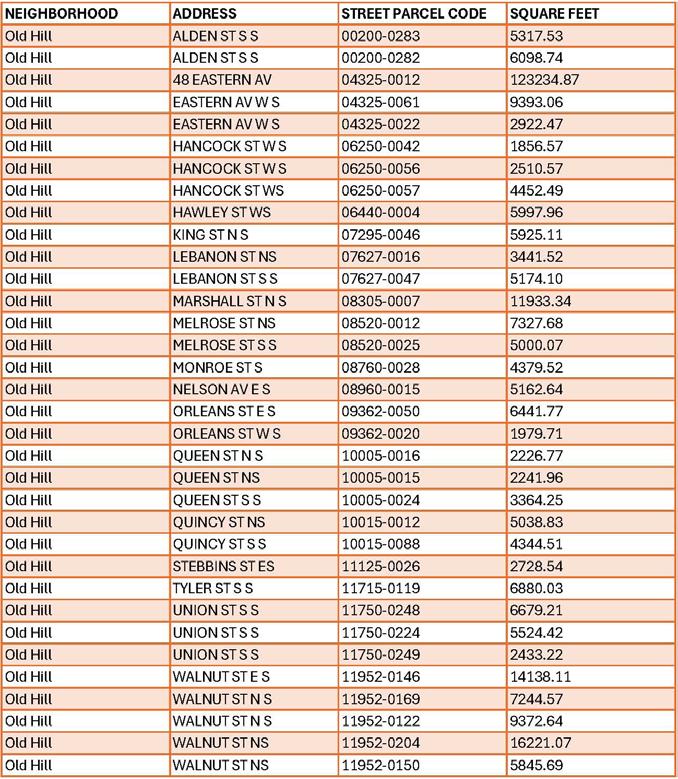

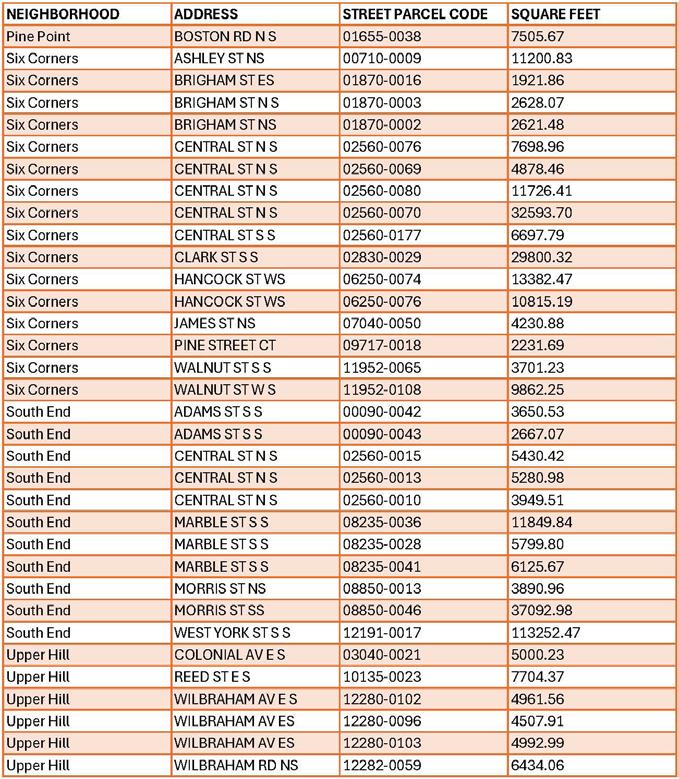

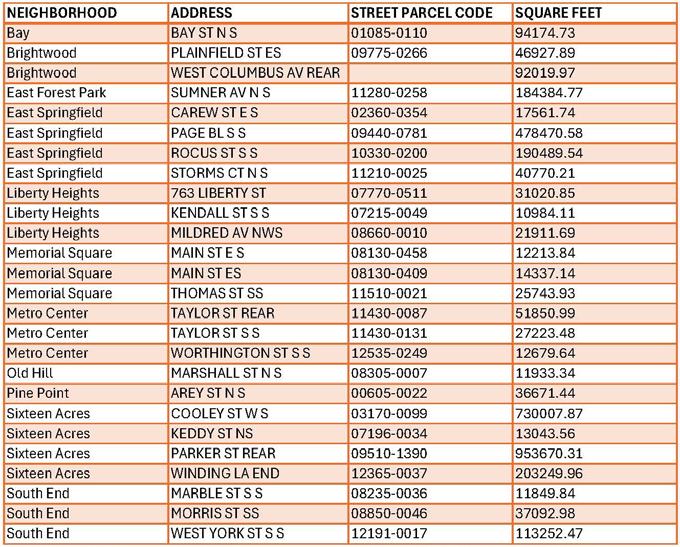

After applying all of the criteria listed in Tier 1A, 227 City-owned vacant lots remain, and the number of lots within the Old Hill neighborhood starts to become more pronounced. These lots will now be examined with the mappable Tier 1B criteria, which include factors related to the ease of use and safety of a site, as well as the size of a site for different food production uses.

Source: MassGIS: MassGIS - MassDOT Roads (2023)

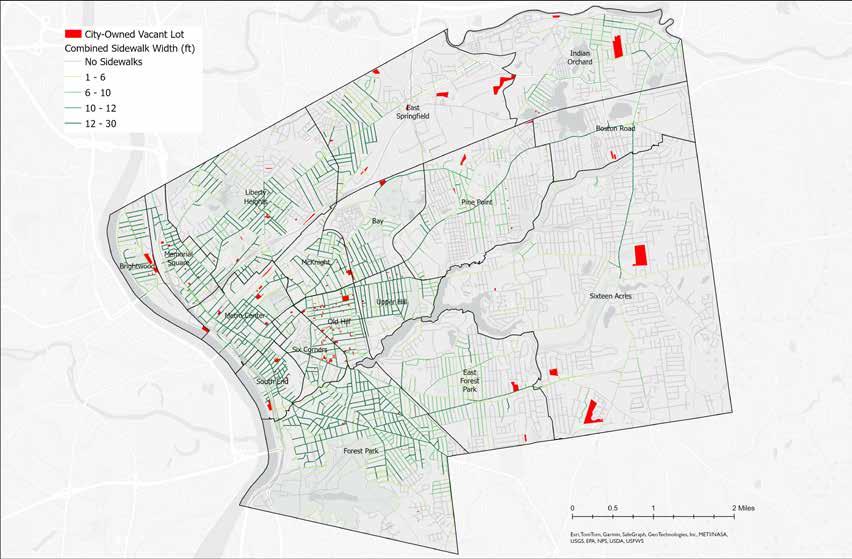

The most heavily-trafficked roads are within the western portion of the city, indicated by shades of red and orange. Minor streets, which have significantly fewer vehicles per day, are represented by yellow roads. The categorization of roads is based on the annual average of daily traffic. The high number of vehicles using major roads generates increased noise pollution as well as increased levels of fine particulate matter in the air, lowering air quality. Both of these factors can make outdoor activity, like food production on a site, and walking to and from a site, difficult, uncomfortable, and potentially harmful.

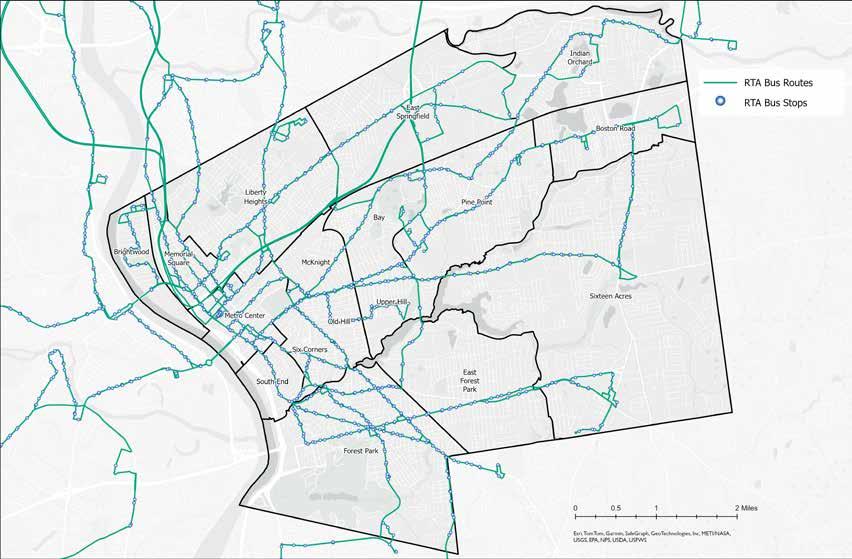

Source: MassDOT: RTA Bus Routes (2024), RTA Bus Stops (2024)

The Regional Transit Authority (RTA) that serves Springfield, among many cities within the region, is the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority (PVTA). The PVTA bus lines are a crucial resource within Springfield, considering many families do not own personal vehicles. The lines have many stops, allowing for a short walking distance to many destinations around the city. Many of PVTA’s routes are congregated in western Springfield, and generally follow major roads shown in the previous map. Bus stops are evenly spaced throughout all routes, about one stop per one

to two blocks. This map does not display the frequency of routes.

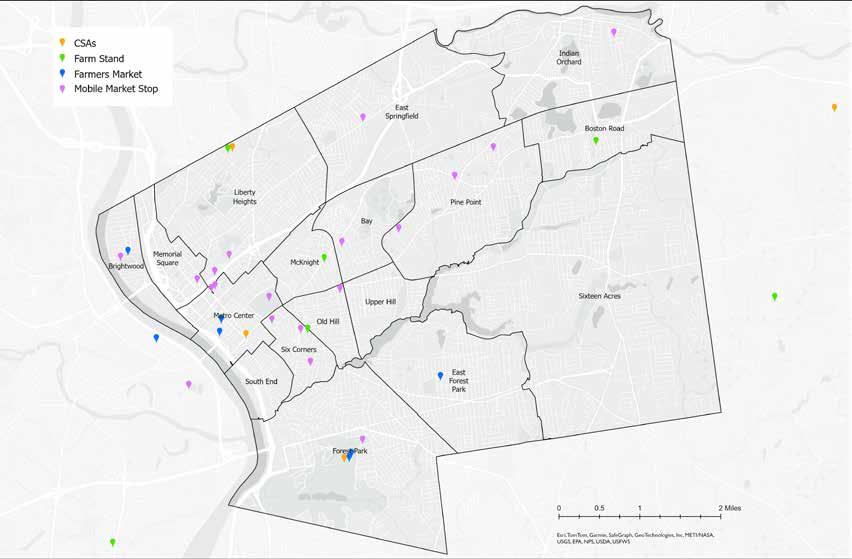

Source: MassGIS: Property Tax Parcels (2023), MassGIS - MassDOT Roads (2023); MassDOT: RTA Bus Routes (2024)